↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Transformer neural networks have achieved remarkable empirical success across diverse AI domains; however, a theoretical understanding of their algorithmic reasoning capabilities remains limited. This study investigates how depth, width, and additional tokens affect the network’s capacity to solve various graph-based reasoning tasks. Existing work lacks a comprehensive understanding of transformer capabilities across different realistic parameter regimes.

This research introduces a novel representational hierarchy categorizing graph reasoning problems into classes solvable by transformers under different scaling regimes. The authors prove that logarithmic depth is both necessary and sufficient for parallelizable tasks, while single-layer transformers suffice for retrieval tasks. Empirical evidence from the GraphQA benchmark validates these findings, showcasing that transformers excel in global reasoning and outperform specialized GNNs, except in low-sample scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers because it provides a much-needed theoretical framework for understanding the reasoning capabilities of transformer models, a dominant architecture in many AI applications. Its findings challenge existing assumptions about transformer scaling and offer new insights into algorithm design for neural networks. The paper also provides a novel benchmark for evaluating transformer performance, which has significant implications for future research and development.

Visual Insights#

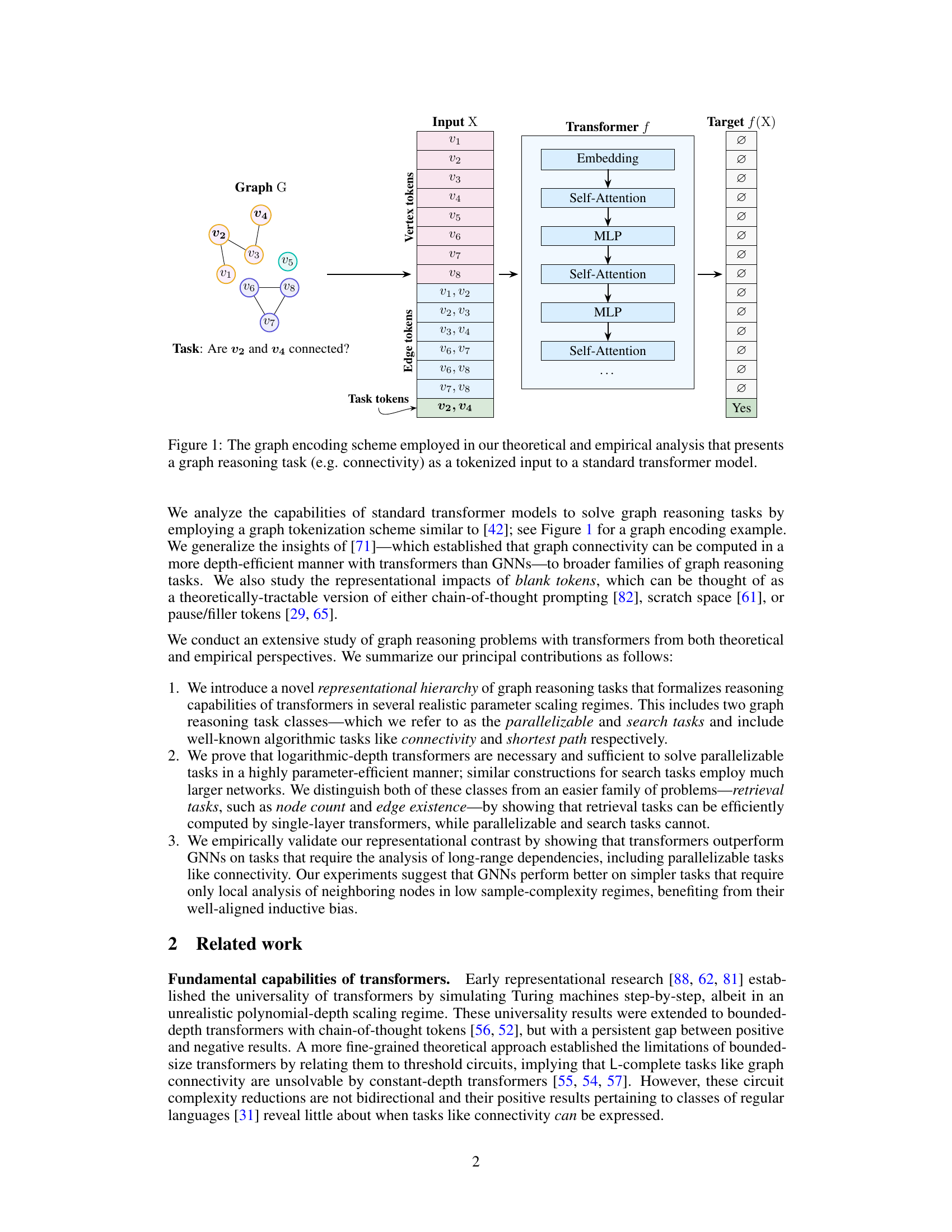

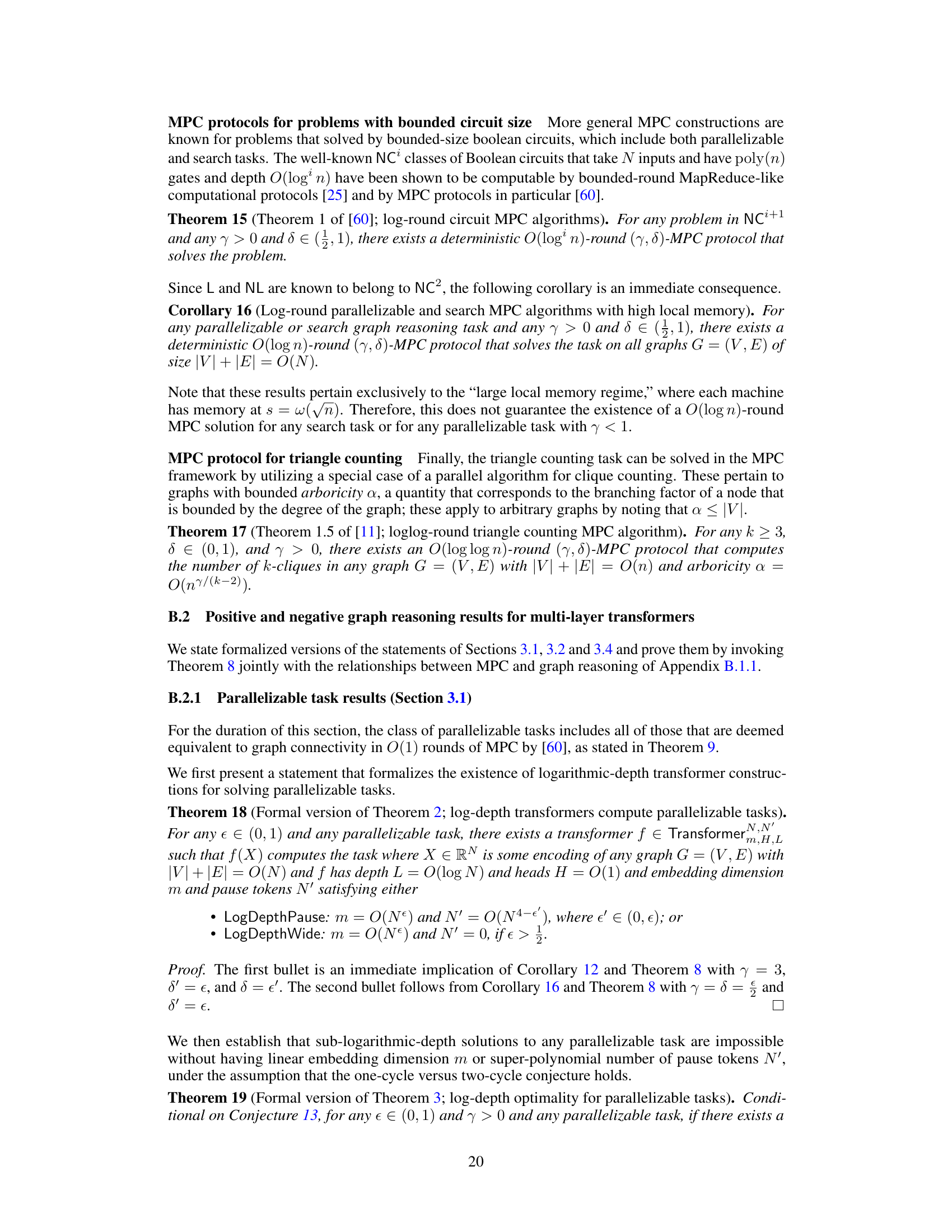

This figure illustrates how a graph reasoning problem is presented to a transformer model. The input consists of three parts: vertex tokens representing the nodes in the graph, edge tokens representing the connections between the nodes, and task tokens specifying the question to be answered. This encoding scheme is used in both the theoretical analysis and empirical evaluations presented in the paper. The example shows a graph with eight nodes and a query about the connectivity of two specific nodes.

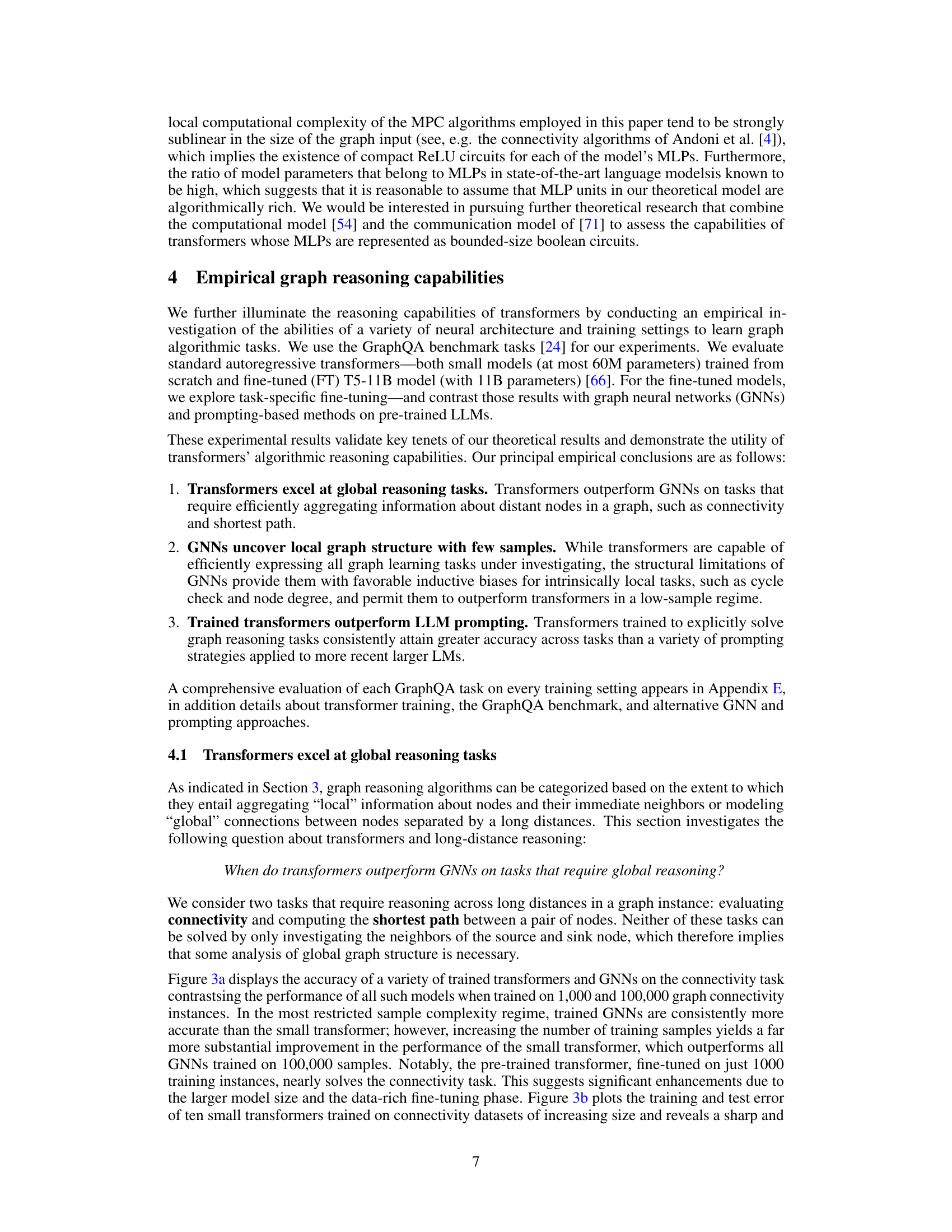

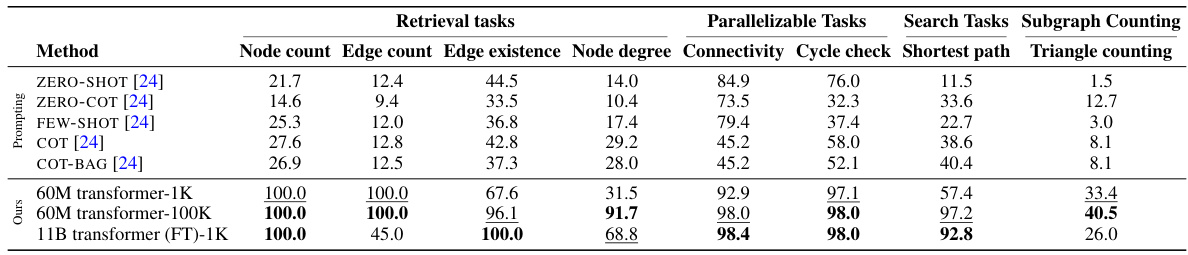

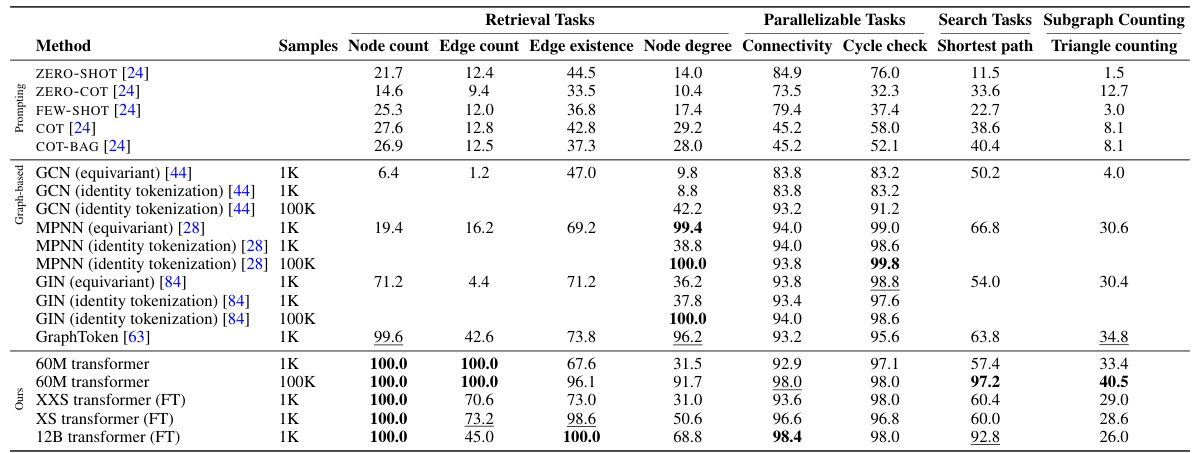

This table compares the performance of various models on several graph reasoning tasks from the GraphQA benchmark. The models include explicitly trained transformers of different sizes (60M parameters and 11B parameters), as well as LLMs using several prompting strategies (ZERO-SHOT, FEW-SHOT, COT, ZERO-COT, and COT-BAG). The table allows for a direct comparison of the accuracy of different techniques in solving various graph reasoning tasks, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each approach. The results are categorized by task difficulty (retrieval, parallelizable, and search tasks), allowing for a nuanced understanding of model capabilities.

In-depth insights#

Transformer Power#

The concept of “Transformer Power” in the context of a research paper likely refers to the capabilities and potential of transformer networks. A thoughtful analysis would explore several key aspects. First, computational efficiency is crucial; transformers’ ability to process information in parallel contributes significantly to their power. Second, representational capacity is paramount: the depth and width of the transformer architecture determine its ability to learn complex patterns and relationships. A key question is how these factors interact with parameter scaling regimes to determine optimal performance on various tasks. Third, generalization ability is vital. Do transformers excel at specific types of problems (e.g., those with long-range dependencies)? A powerful transformer should demonstrate strong generalization to out-of-distribution samples. Fourth, benchmarking against existing models (like specialized graph neural networks) is essential to establish the true power of transformers and uncover their strengths and weaknesses. Finally, a comprehensive analysis would delve into the theoretical underpinnings, proving or disproving claims about computational complexity and representational limits.

Graph Encoding#

Effective graph encoding is crucial for leveraging the power of transformer models on graph-structured data. A well-designed encoding scheme needs to capture essential graph properties such as connectivity, node features, and edge relationships while remaining computationally efficient. The choice of encoding significantly impacts model performance and generalizability. Tokenization strategies, such as representing nodes and edges as individual tokens or employing more sophisticated methods like graph convolutional networks (GCNs) for feature extraction, present various trade-offs. Node ordering and positional embeddings are critical considerations, as they can influence the model’s ability to learn long-range dependencies and structural patterns. Furthermore, the embedding dimension and the overall encoding length play a vital role in balancing the capacity to represent complex graph structures against computational requirements. Ultimately, selecting or designing an appropriate graph encoding scheme involves careful analysis of the specific task, the available computational resources, and the model architecture used.

GNN Comparison#

A comparative analysis of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) against Transformers in solving graph reasoning tasks reveals interesting strengths and weaknesses of each architecture. GNNs excel in tasks requiring local analysis, demonstrating a favorable inductive bias for understanding immediate neighbors in a graph. This advantage translates to superior performance in low-sample regimes. In contrast, Transformers shine in tasks demanding global reasoning, efficiently aggregating information across distant nodes. This global processing power enables Transformers to outperform GNNs in high-sample regimes for tasks like connectivity and shortest path, where long-range dependencies are crucial. The relative performance of each architecture strongly depends on the specific reasoning problem and the availability of training data, highlighting a fundamental trade-off between inductive biases and representational capacity.

Scaling Regimes#

The concept of “scaling regimes” in the context of transformer models refers to how different aspects of the model’s architecture, such as depth, width, and the number of additional tokens, affect its ability to solve various algorithmic tasks. Understanding these scaling regimes is crucial because it reveals the trade-offs between model complexity and performance. Some tasks might be efficiently solved by shallow, wide transformers, while others might require deep, narrow models with additional tokens. This understanding is important for optimizing model design to efficiently perform particular kinds of tasks, balancing computational costs with accuracy. The research highlights a representational hierarchy of tasks based on their inherent computational complexity. This hierarchy helps to categorize tasks based on the types of scaling regimes that are most suitable for solving them efficiently. This categorization is key to understanding and optimizing performance. Further research should focus on the detailed implications for learnability and the exploration of more sophisticated model architectures that may transcend the limitations of these regimes. The research makes an important contribution by formally quantifying this relationship and provides a compelling analytical framework to guide future model development.

Future Work#

The paper’s absence of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section presents an opportunity for impactful extensions. Theoretically, investigating the bidirectional nature of transformers for tasks beyond those analyzed (e.g., exploring the implications of relaxing the assumption of arbitrary MLP functions) would strengthen the model. Empirically, exploring larger transformer models and diverse graph datasets is crucial for evaluating scalability and generalizability. Further research could investigate the interplay between inductive biases in transformers and GNNs, potentially leading to hybrid architectures that leverage the strengths of both. Methodologically, developing more sophisticated evaluation metrics beyond simple accuracy would provide deeper insights into transformer capabilities. Finally, studying the effect of different graph tokenization schemes on model performance would be insightful. Addressing these areas would significantly enhance understanding of transformer reasoning in the context of graph algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure presents a hierarchical representation of graph reasoning tasks based on their complexity for transformer models. The hierarchy categorizes tasks into three levels of difficulty: Retrieval, Parallelizable, and Search. Each level is associated with a specific transformer scaling regime defined by depth (L), embedding dimension (m), and the number of pause tokens (N’). Retrieval tasks are the simplest and can be solved by single-layer transformers. Parallelizable tasks require logarithmic depth transformers, while Search tasks demand even larger, logarithmic-depth and wide transformers. The figure also provides example tasks for each category and their corresponding complexity.

This figure presents a hierarchy that categorizes graph reasoning tasks into three difficulty levels based on their solvability using transformers with different parameter scaling regimes. The three classes are: Retrieval tasks (easily solved with single-layer transformers), Parallelizable tasks (solved efficiently with logarithmic-depth transformers), and Search tasks (requiring significantly larger, logarithmic-depth transformers). The figure illustrates which types of tasks fall into each class and what transformer configurations are necessary to solve them.

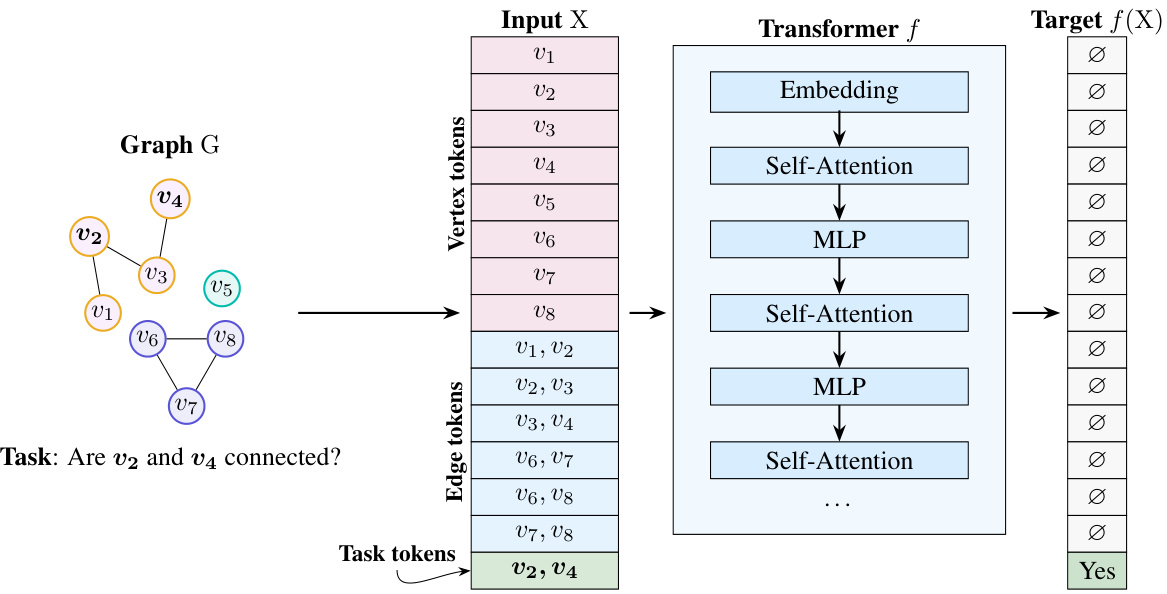

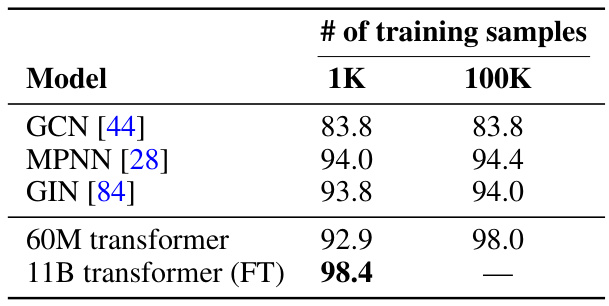

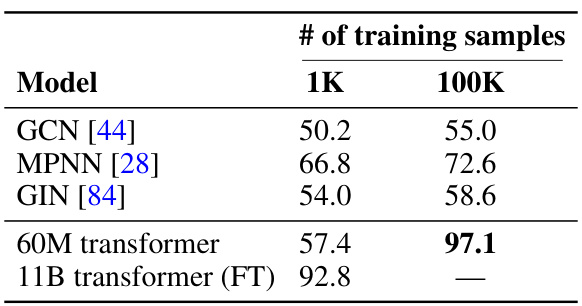

This figure compares the accuracy of various trained transformer models and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on the graph connectivity task. It shows how accuracy varies with the number of training examples used for each model. The results demonstrate that transformers, particularly larger fine-tuned models, excel at this global graph reasoning task, surpassing GNNs, especially when trained on larger datasets. GNNs, however, perform better with smaller training datasets, suggesting a difference in sample efficiency.

The figure illustrates how a graph reasoning task is encoded as input for a standard transformer model. A graph G is represented using vertex tokens, edge tokens, and task tokens. Vertex tokens represent the nodes in the graph, edge tokens represent the edges connecting the nodes, and task tokens specify the question to be answered (e.g., ‘Are v2 and v4 connected?’). This tokenized input is then fed into a transformer model, which processes it through multiple layers of self-attention and MLPs to produce a final output (e.g., ‘Yes’). This encoding scheme is used in both the theoretical and empirical analyses presented in the paper.

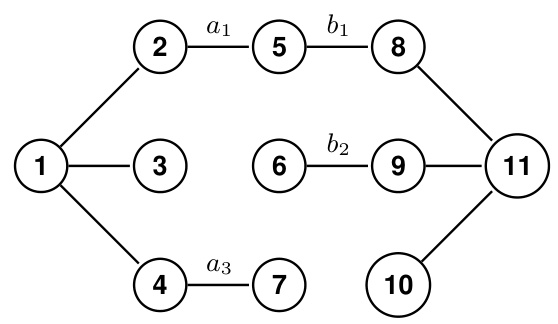

This figure illustrates a constant diameter graph construction used to demonstrate the hardness of solving the graph connectivity problem by single-layer transformers. The graph is designed such that connectivity between the source node (1) and sink node (11) directly encodes the solution to the set disjointness problem (DISJ). The edges are partitioned into three groups: fixed edges, edges determined by Alice’s input, and edges determined by Bob’s input. The connectivity problem is solvable if and only if the set disjointness problem is solvable, thus demonstrating the equivalence of the two problems under this specific graph construction.

This figure shows a constant diameter graph construction used to encode a set disjointness problem as a graph connectivity problem. The graph consists of a source node, a sink node, and two paths connecting them, one path encoding Alice’s input (A) and the other encoding Bob’s input (B). An edge exists between nodes if and only if the corresponding bits in Alice’s and Bob’s inputs are both 1. Thus, the graph is connected if and only if Alice’s and Bob’s inputs have at least one bit in common (i.e., DISJ(A, B) = 1).

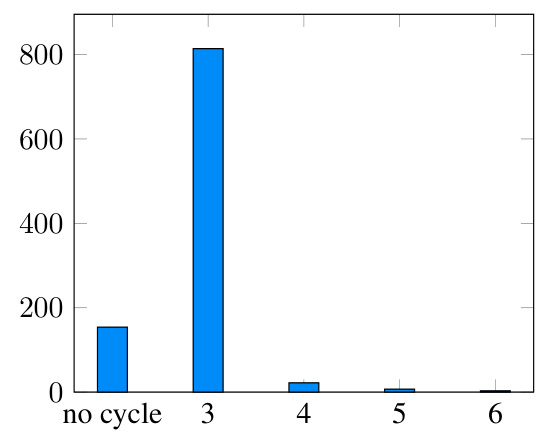

This histogram shows the distribution of minimum cycle lengths in the GraphQA cycle check dataset. The majority of graphs (around 800 out of 1000) contain cycles of length 3. A much smaller number of graphs have cycles of length 4, 5, or 6, and a small number of graphs have no cycles at all.

This figure shows the accuracy of various trained transformer models and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on the graph connectivity task. The results are presented for two different numbers of training examples (1,000 and 100,000) in order to demonstrate the impact of training data size. It demonstrates that transformers outperform GNNs when trained with sufficient data, particularly in solving tasks requiring the analysis of long-range dependencies within the graph. Conversely, in a low-data regime, GNNs can outperform transformers, highlighting a contrast in sample efficiency between the two model architectures.

More on tables

The table compares the performance of different transformer models and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on the shortest path prediction task. It shows the accuracy of each model with different numbers of training samples (1K and 100K). The results demonstrate that fine-tuned large language models (LLMs) significantly outperform smaller transformers and GNNs, highlighting the benefits of larger model sizes and fine-tuning for complex graph reasoning tasks. Even with a smaller number of training samples, the fine-tuned large model shows high accuracy.

This table compares the performance of various models on different graph reasoning tasks from the GraphQA benchmark dataset. The models are categorized into three groups: prompting-based methods (using LLMs with different prompting strategies), graph-based methods (using GNN architectures), and transformer models (trained from scratch and fine-tuned). The tasks are further categorized based on a novel representational hierarchy proposed in the paper (retrieval, parallelizable, search, and subgraph counting). The table shows the accuracy of each model on each task category, providing a comprehensive comparison of their capabilities.

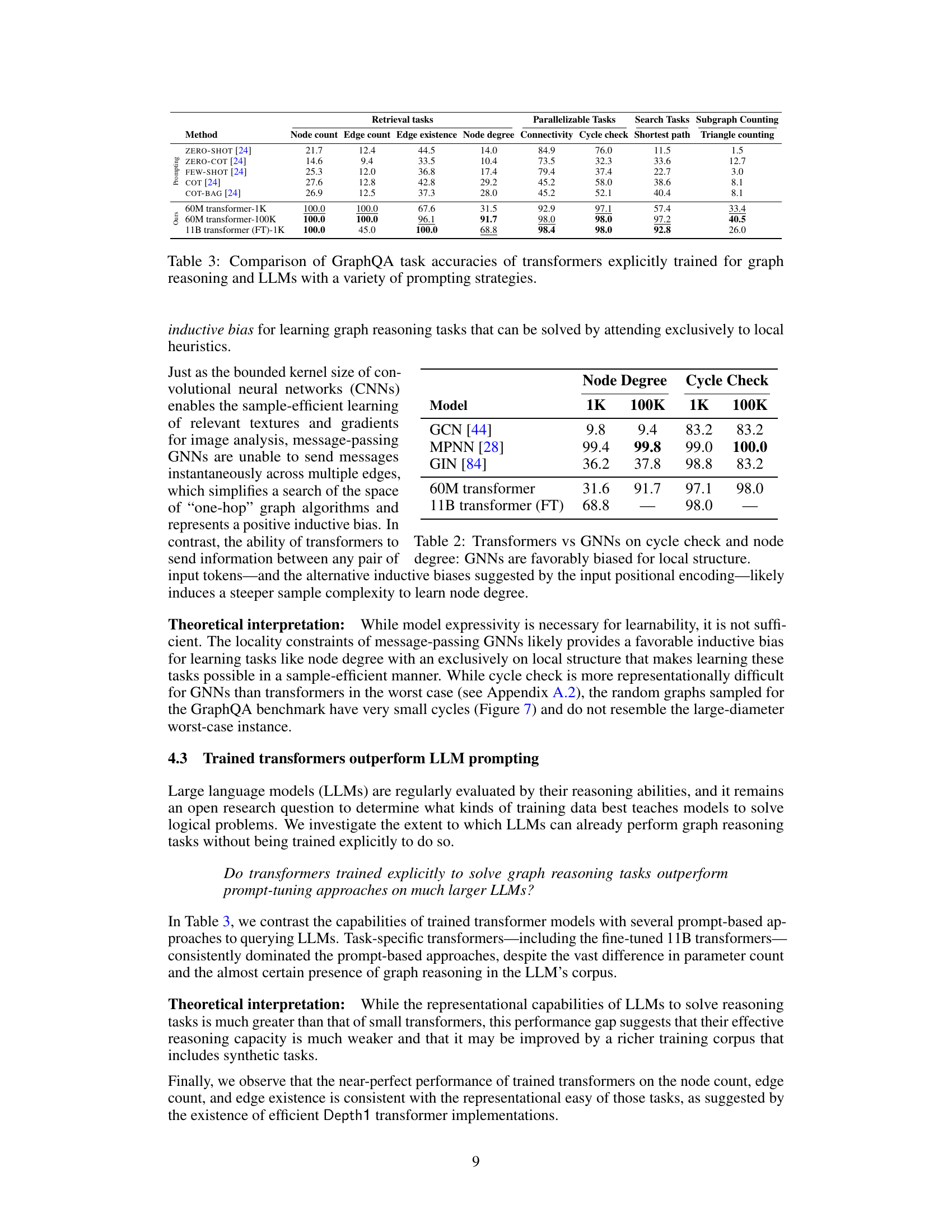

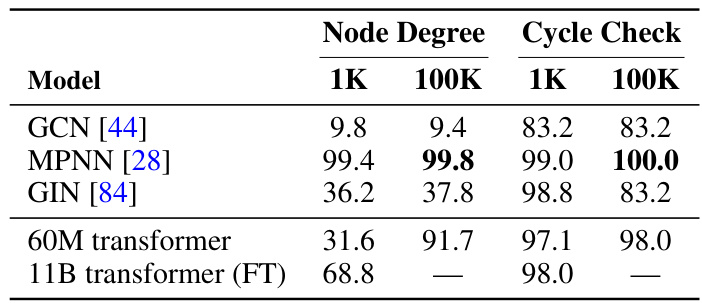

The table compares the performance of transformers and graph neural networks (GNNs) on two graph reasoning tasks: node degree and cycle check. The results show that GNNs, particularly MPNN and GIN, significantly outperform the 60M parameter transformer, especially in the low-sample regime (1K training examples). This suggests that GNNs have a favorable inductive bias for tasks that are intrinsically local, such as node degree and cycle check, enabling them to learn effectively from a small number of samples. The larger 11B parameter fine-tuned transformer shows substantially improved accuracy, but still doesn’t match the GNN performance on node degree with only 1K training examples.

This table compares the performance of various models on different graph reasoning tasks from the GraphQA benchmark. The models are categorized into three groups: prompting-based methods (using LLMs with various prompting techniques), graph-based methods (GNNs such as GCN, MPNN, and GIN), and transformer models (the authors’ models). The table shows the accuracy of each method on each task, categorized by the task difficulty (retrieval, parallelizable, search) as defined in Section 3 of the paper. The results demonstrate the strengths and weaknesses of different models on different types of graph reasoning tasks.

This table presents the mean accuracy and standard deviation results for trained 60M parameter transformers across five different random seeds. The results are categorized by task type (retrieval, parallelizable, search, and subgraph counting) and training data size (1K or 100K samples). It demonstrates the model’s performance consistency and the impact of training data size on accuracy across different graph reasoning task complexities.

Full paper#