↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Analyzing how cells respond to perturbations is crucial for drug discovery, but existing methods often struggle due to the complexity of cellular contexts and the high dimensionality of single-cell RNA sequencing data. Existing methods often fail to fully capture the interaction between treatments and cellular contexts, hindering their ability to reveal mechanistic insights and predict responses accurately.

The researchers propose a new method called Factorized Causal Representation (FCR). FCR uses a deep generative model to learn multiple disentangled cellular representations that explicitly account for the effects of both treatment and cellular context, including their interactions. The method’s identifiability is proven theoretically and empirically shown to outperform existing methods in various tasks, such as clustering and predicting gene expression. The FCR framework’s ability to disentangle these factors provides a more accurate understanding of how cells respond to treatment, offering valuable insights into the underlying biological mechanisms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel method for analyzing single-cell perturbation data, addressing the critical need for methods that explicitly consider the biological context of cells. Its theoretical guarantees of identifiability and superior performance on various tasks make it a significant contribution to the field, opening new avenues for therapeutic target discovery and furthering our understanding of cellular responses.

Visual Insights#

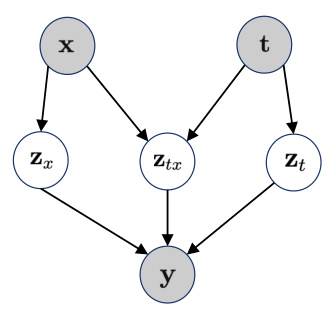

This figure shows a graphical representation of the generative model used in the paper. The model consists of three latent variables: Zx, Ztx, and Zt, representing the effects of covariates, the interaction between covariates and treatments, and the effects of treatments, respectively. These latent variables are combined through a deterministic function g to generate the observed gene expression outcome y. The figure highlights that x and t are observed variables while Zx, Ztx, and Zt are latent variables.

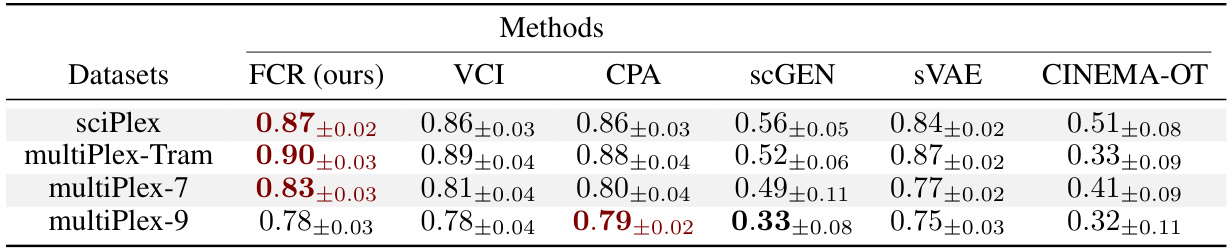

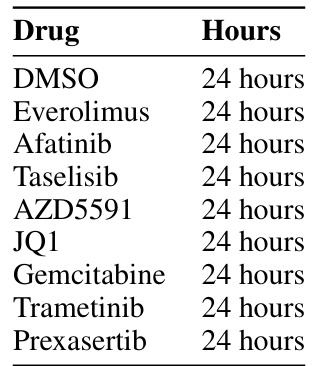

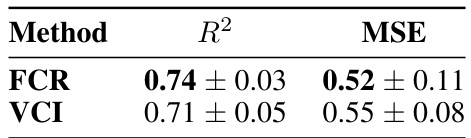

This table presents the R-squared (R²) values achieved by different methods in predicting cellular responses. The R² score quantifies the goodness of fit of the model by measuring the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (gene expression levels) that is explained by the independent variables (latent representations generated by different methods). Higher R² scores indicate better predictive performance. The table shows the results for four different datasets: sciPlex, multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-7, and multiPlex-9.

In-depth insights#

Factorized Causal Learning#

Factorized causal learning is a powerful technique for disentangling complex cause-and-effect relationships in data. It leverages the principle of factorization to decompose high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional latent factors, each representing a distinct causal mechanism. This approach is particularly valuable when analyzing cellular responses to perturbations, where multiple biological contexts and treatment effects interact in intricate ways. By explicitly modeling these interactions, factorized causal learning can reveal causal structures that are hidden in traditional methods. A key advantage is the ability to identify and isolate the effects of specific treatments, covariates, and their interactions, leading to more accurate and interpretable models. This is particularly crucial in drug discovery, where understanding the specific causal pathways underlying therapeutic effects is critical. However, successful application hinges on careful consideration of identifiability and disentanglement, requiring appropriate theoretical frameworks and model architectures. The challenge lies in ensuring that the learned factors truly reflect underlying causal processes, rather than merely capturing statistical correlations. Future work could explore more sophisticated causal inference techniques to further enhance the reliability and interpretability of this approach.

Identifiable Deep Models#

Identifiable deep models represent a significant advancement in the field of deep learning, offering theoretical guarantees about the learned representations. Unlike traditional deep learning models where the latent space is often entangled and difficult to interpret, identifiable models aim to disentangle the underlying factors of variation, leading to more interpretable and meaningful representations. This is crucial for applications in various fields like causal inference and generative modeling where understanding the relationships between variables is paramount. Identifiability ensures that the model’s learned parameters uniquely correspond to the underlying data generating process, reducing ambiguity and allowing for more robust causal inferences. While achieving identifiability poses significant challenges, particularly in non-linear settings, recent advancements using techniques such as non-linear ICA and variational autoencoders have shown promising results. These methods leverage constraints and assumptions about the data distribution to improve the disentanglement and identifiability of the learned representations. The key benefits of identifiable deep models lie in their ability to provide more reliable and trustworthy insights into complex systems, facilitating improved decision-making in scientific discovery, medical diagnosis, and other applications requiring a nuanced understanding of causal relationships.

Single-cell Perturbation#

Single-cell perturbation experiments are transforming our understanding of cellular responses to external stimuli. By isolating individual cells and applying controlled perturbations (genetic or chemical), researchers can precisely monitor the effects on gene expression, signaling pathways, and cellular phenotypes. This approach offers unprecedented resolution in studying cellular heterogeneity and identifying key regulators of cellular processes. High-throughput screening coupled with single-cell technologies facilitates the identification of vulnerabilities in disease-related cells, thus enabling drug discovery and personalized medicine. However, single-cell perturbation data also present substantial analytical challenges, including high dimensionality and noise in the data, as well as the need to account for biological context (e.g., genetic background, cell type). Advanced computational methods are crucial to address these challenges and effectively uncover causal relationships within the complex regulatory networks of the cell.

Disentangled Representations#

Disentangled representations aim to decompose complex data into independent, meaningful components. In the context of cellular responses, this means separating the effects of different perturbations (e.g., genetic modifications, drug treatments) from the inherent biological variability of the cells. Achieving disentanglement allows researchers to isolate the causal effects of specific treatments, improving the understanding of drug mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets. This approach is crucial because cellular responses are often context-dependent, and disentangling these factors is essential to establish robust and generalizable predictive models. Successfully disentangling representations can pave the way for powerful counterfactual analyses, enabling researchers to simulate what would happen under different conditions, which is critical for effective drug design and development. Identifiability is a key challenge, ensuring the learned components accurately reflect the underlying causal structure. Methods employing disentanglement often rely on deep generative models, requiring careful consideration of their architecture and training procedures to guarantee a truly disentangled representation. Ultimately, the success of disentangled representations lies in their ability to provide clearer mechanistic insights and facilitate a deeper understanding of complex biological systems.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending FCR to handle diverse data modalities, such as integrating multi-omics data or incorporating spatial information from single-cell experiments. Investigating the impact of different noise models on FCR’s performance and identifiability is crucial. The theoretical guarantees of FCR should be extended to more complex scenarios, like non-linear interactions or time-dependent effects. Developing more efficient algorithms for FCR, especially for large-scale datasets, would improve practical applicability. Furthermore, exploring methods for incorporating prior knowledge, such as known drug mechanisms or gene regulatory networks, could enhance prediction accuracy and mechanistic interpretability. Finally, applying FCR to diverse biological questions, beyond the scope of drug response prediction, could broaden its impact and reveal new insights into cellular processes.

More visual insights#

More on figures

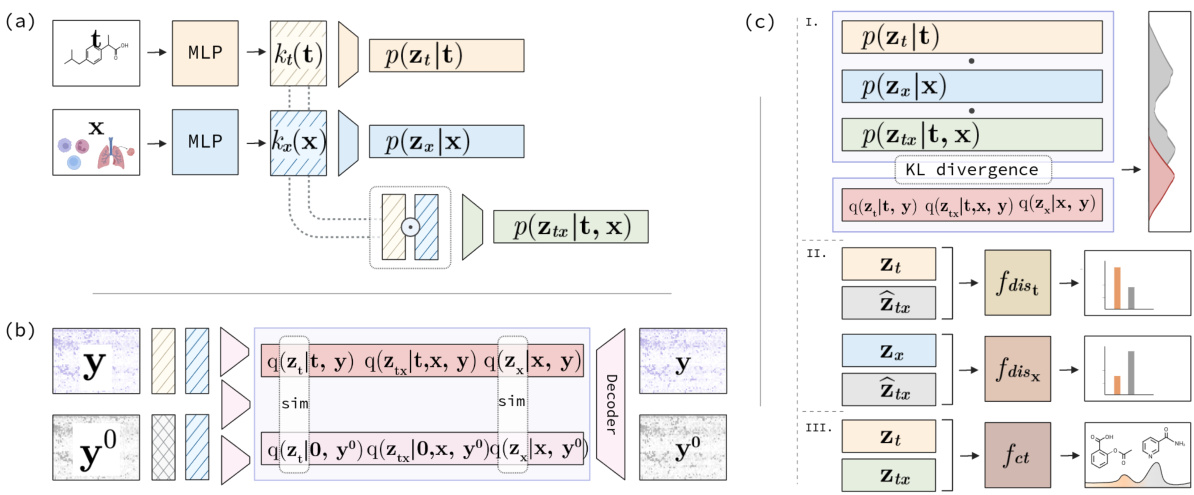

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Factorized Causal Representation (FCR) model. Panel (a) shows the generative model, which consists of three components: Zx (covariate-specific), Zt (treatment-specific), and Ztx (interaction-specific). Panel (b) depicts the inference network, used to approximate the posterior distributions of these three latent variables given the observed gene expression data. Panel (c) provides a schematic of the three regularizers used in the FCR model to ensure disentanglement and identifiability of the latent variables. These regularizers are based on Kullback-Leibler divergence, causal structure regularization, and permutation discrimination.

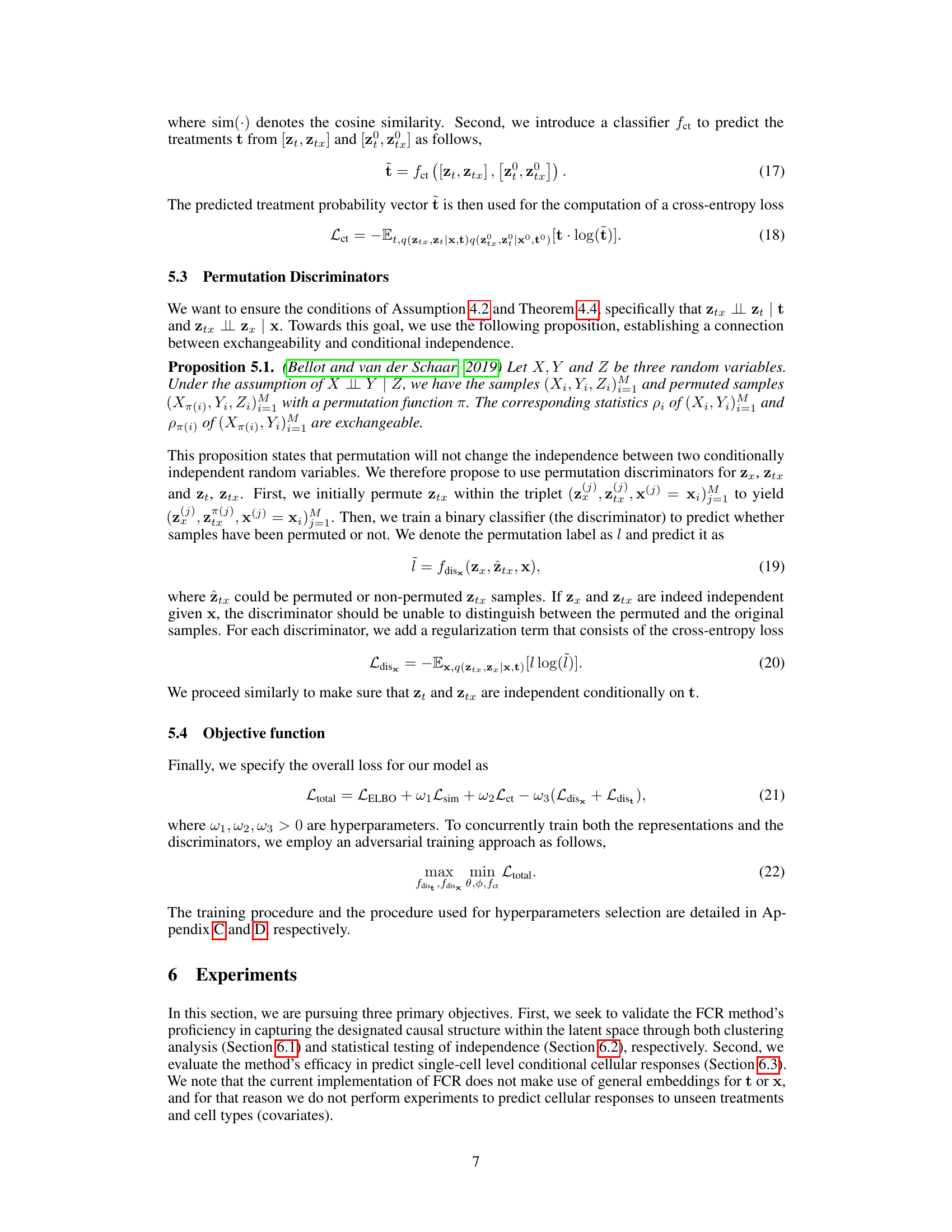

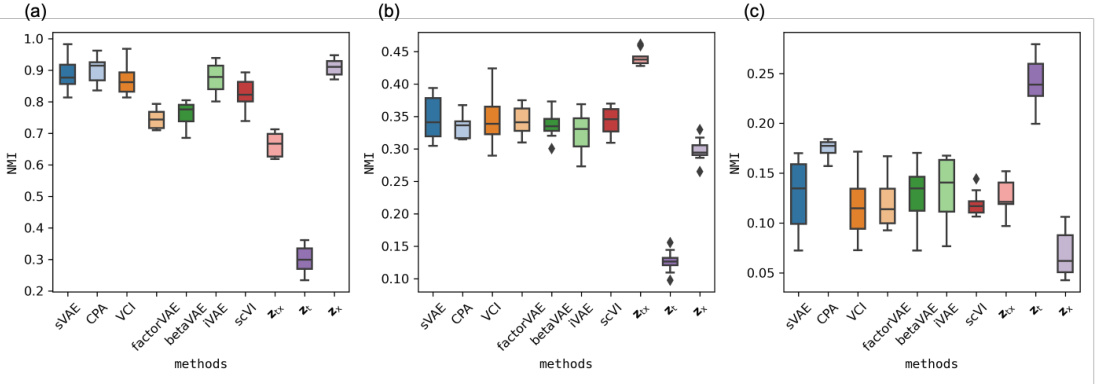

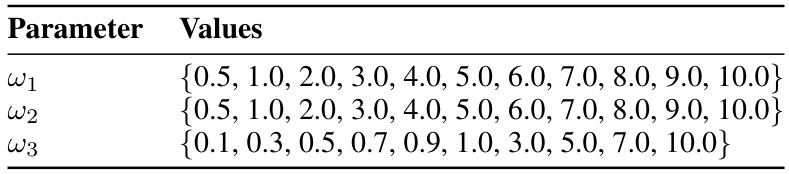

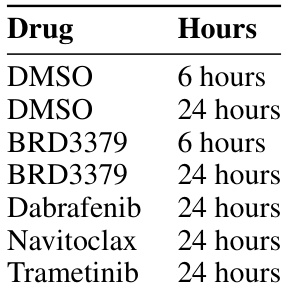

This figure presents the results of a clustering analysis performed on the sciPlex dataset using three different sets of features: covariates (x), combined covariates and treatments (x; t), and treatments (t). The performance of different methods (SVAE, CPA, VCI, factorVAE, betaVAE, iVAE, and SCVI) is compared using the Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) metric. Higher NMI values indicate better performance. The figure aims to show the effectiveness of the FCR method in disentangling the effects of covariates and treatments on cell responses.

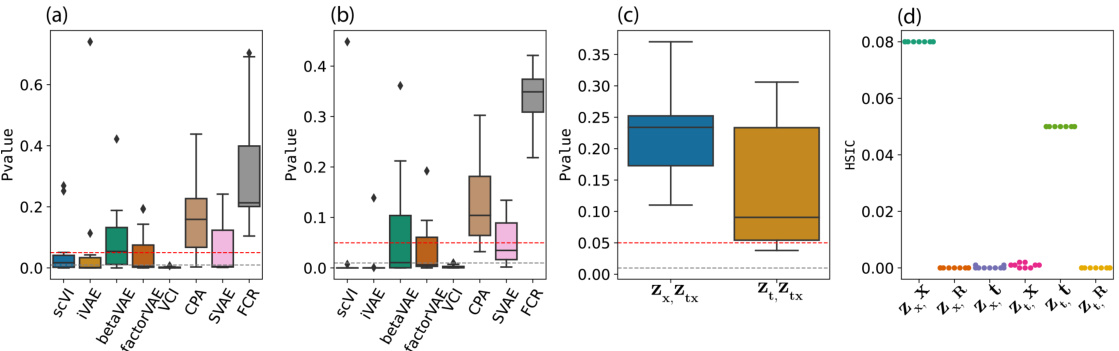

This figure presents statistical testing results to validate the disentanglement of latent representations learned by FCR and other baselines. Panel (a) and (b) show p-values from conditional independence tests, assessing whether treatment and covariate representations are conditionally independent given covariates and treatments, respectively. Panel (c) shows similar tests evaluating conditional independence between interaction and treatment/covariate representations. Finally, Panel (d) shows Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) values to evaluate marginal independence between latent variables and covariates/treatments, using random variables as a control. Lower p-values indicate a stronger dependence, while higher HSIC values indicate stronger association. The results support that FCR successfully disentangles latent factors.

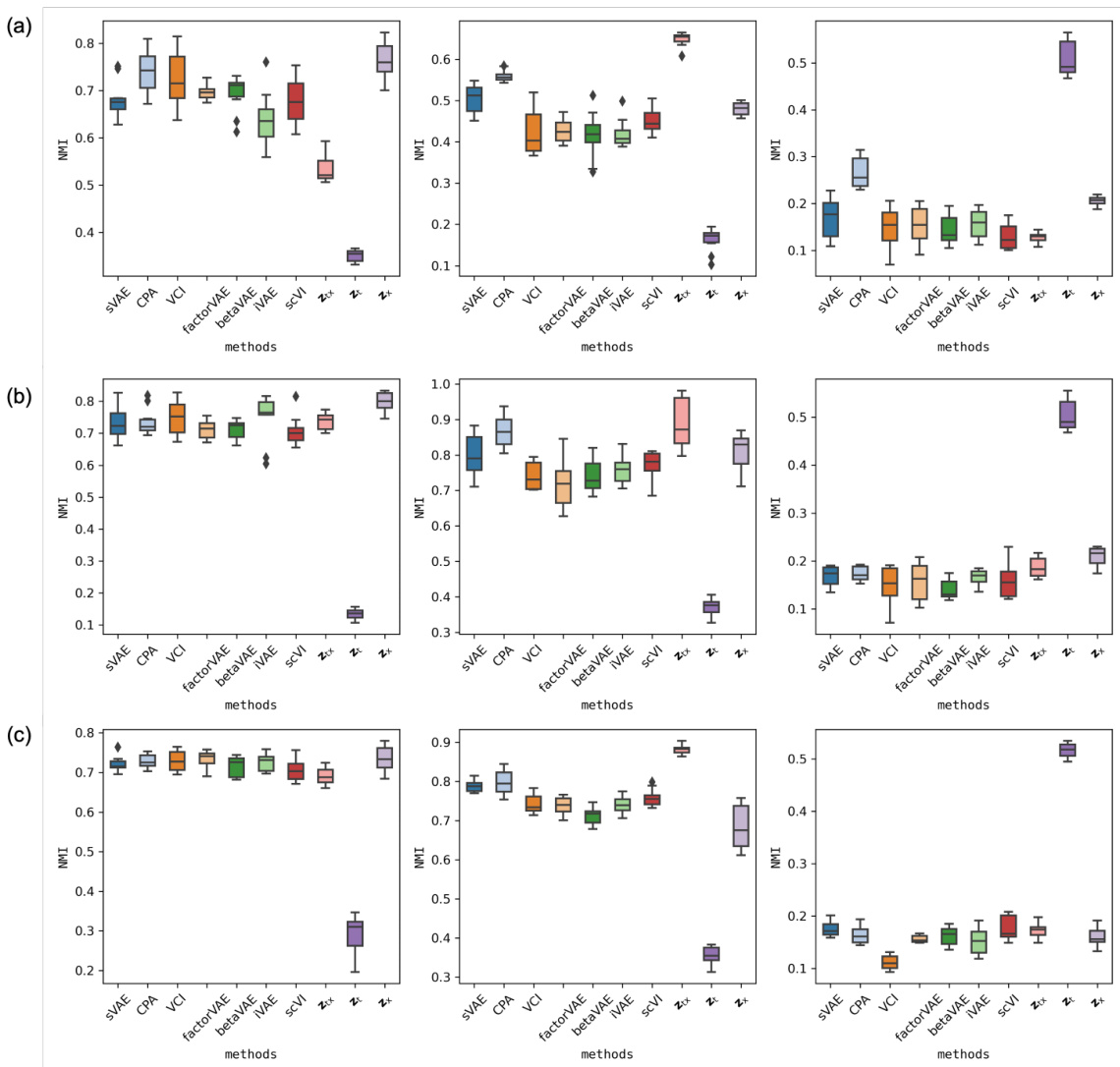

This figure displays box plots of the Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) values for clustering experiments on three datasets: multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-5, and multiPlex-9. Each dataset is analyzed using three different feature sets: covariates (x), combined covariates and treatments (xt), and treatments (t). The NMI values quantify how well the clustering results based on different latent representations align with the ground truth labels for covariates, treatments, or both. High NMI values indicate a good match between predicted clusters and true labels.

This figure displays the performance of different methods in clustering single-cell data based on covariates (cell information), treatments (drug dosages), and the combination of both. The Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) score is used to measure the quality of the clustering, with higher scores indicating better agreement between the predicted clusters and true labels. The figure shows that FCR outperforms other methods across different clustering scenarios, suggesting its effectiveness in disentangling the effects of treatments and covariates in single-cell data.

This figure displays the UMAP visualizations of two single-cell datasets. The sciPlex dataset shows clear separation of different cell types and treatment durations; the multiPlex-tram dataset also shows a clear separation of cell types and treatment durations, with brighter colors representing longer durations. These visualizations demonstrate the ability of the FCR model to disentangle different factors in the single-cell data.

This figure displays the performance of different methods in clustering single-cell data based on three different features: covariates only, covariates and treatments combined, and treatments only. The Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) score is used to measure the quality of the clustering, with higher NMI values indicating better agreement between the clustering results and the true labels. The figure shows that FCR (the proposed method) outperforms other methods in all three scenarios, demonstrating its ability to capture the complex relationships between covariates, treatments, and cellular responses.

This figure displays the UMAP visualizations of the latent representations (Zx, Ztx, Zt) learned by the FCR model for two single-cell datasets: sciPlex and multiPlex-tram. The sciPlex visualizations show clear separation of cell types in the top row and treatment time in the bottom row. Similarly, the multiPlex-tram visualizations distinguish cell types and treatment times. Brighter colors represent longer treatment durations in both datasets. The visualizations demonstrate that the FCR model effectively disentangles the different factors influencing cellular responses.

This figure shows the UMAP visualizations of the latent representations (Zx, Ztx, Zt) learned by FCR from the sciPlex and multiPlex-tram datasets. The visualizations reveal how well FCR disentangles the data based on cell type and treatment time. Brighter colors in the second rows indicate longer treatment durations. These plots help to demonstrate the effectiveness of the FCR model in learning interpretable and disentangled representations of single-cell perturbation data.

More on tables

This table presents the R-squared (R²) scores achieved by the proposed Factorized Causal Representation (FCR) method and several baseline methods in predicting conditional cellular responses. The R² score quantifies the goodness of fit of the model’s predictions to the actual gene expression levels. Higher R² values indicate better model performance. The table includes results for four different datasets (sciPlex, multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-7, and multiPlex-9), providing a comprehensive evaluation of the FCR method across various experimental settings.

This table presents the R-squared (R²) scores achieved by the proposed Factorized Causal Representation (FCR) model and various baseline methods in predicting conditional cellular responses. The R² score, a measure of the goodness of fit, indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (gene expression levels) that is predictable from the independent variables (treatments and covariates). Higher R² values suggest better predictive performance. The table includes results for four different datasets (sciPlex, multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-7, and multiPlex-9), providing a comprehensive evaluation of FCR’s performance across various experimental conditions.

This table presents the R-squared (R²) scores achieved by the proposed Factorized Causal Representation (FCR) method and several baseline methods for predicting conditional cellular responses. The R² score measures the goodness of fit of the model’s predictions to the actual gene expression levels. Higher R² scores indicate better predictive performance. The results are shown for four different datasets: sciPlex, multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-7, and multiPlex-9, reflecting various experimental settings and scales.

This table presents the R-squared (R²) scores achieved by the proposed Factorized Causal Representation (FCR) method and several baseline methods in predicting conditional cellular responses. The R² score quantifies the goodness of fit of the model, indicating how well the model explains the variance in gene expression levels. Higher R² scores indicate better prediction performance. The table includes results for four different single-cell datasets: sciPlex, multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-7, and multiPlex-9.

This table presents the R-squared (R²) scores achieved by the proposed Factorized Causal Representation (FCR) method and several baseline methods in predicting conditional cellular responses. The R² score is a statistical measure that represents the proportion of variance in the gene expression levels that is predictable from the model’s inputs. Higher R² values indicate better predictive performance. The table includes results for four different datasets: sciPlex, multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-7, and multiPlex-9.

This table presents the R-squared (R²) scores achieved by different methods in predicting conditional cellular responses. The R² score measures the proportion of variance in the response variable explained by the model. Higher R² scores indicate better prediction performance. The table includes results for four datasets: sciPlex, multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-7, and multiPlex-9, comparing FCR to multiple other methods such as VCI, CPA, scGEN, sVAE, and CINEMA-OT.

This table presents the Mean Correlation Coefficient (MCC) values, a metric used in Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to assess the identifiability of latent variables. Higher MCC values (closer to 1) indicate better identifiability. The table compares the MCC of the interaction variable ( ) from the proposed FCR method against several baseline methods (β-VAE, FactorVAE, iVAE). The results demonstrate the superior performance of FCR in identifying the interaction component, highlighting its effectiveness in disentangling latent variables.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) values for the top 20 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across four different datasets. The MSE measures the average squared difference between predicted and actual gene expression levels. Lower MSE values indicate better prediction accuracy. The table compares the performance of the proposed Factorized Causal Representation (FCR) method against several baselines (VCI, CPA, and sVAE).

This table presents the R-squared (R²) scores achieved by the proposed Factorized Causal Representation (FCR) method and several baseline methods in predicting cellular responses. The R² score measures the goodness of fit of the models, indicating how well the predicted gene expression levels match the actual observed values. Higher R² scores indicate better predictive performance. The table includes results for four different datasets: sciPlex, multiPlex-Tram, multiPlex-7, and multiPlex-9, each representing different experimental setups and cell types.

Full paper#