↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current self-supervised learning often produces models overly invariant to input changes, misaligned with primate visual area IT. This limits their ability to predict neural responses and understand biological visual processing.

This paper proposes ‘contrastive-equivariant’ self-supervised learning. It modifies standard invariant SSL losses to encourage preservation of input transformations, without explicit supervision. Results show this systematically improves model accuracy in predicting IT neural responses, suggesting structured variability is crucial for biological realism and better model performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel framework for improving the alignment of self-supervised learning models with primate visual area IT. It demonstrates that incorporating known neural computational principles, such as structured variability to input transformations, into model optimization leads to better models of visual cortex and enhanced predictive power. This work opens exciting new avenues for building more biologically plausible and accurate models of the visual system.

Visual Insights#

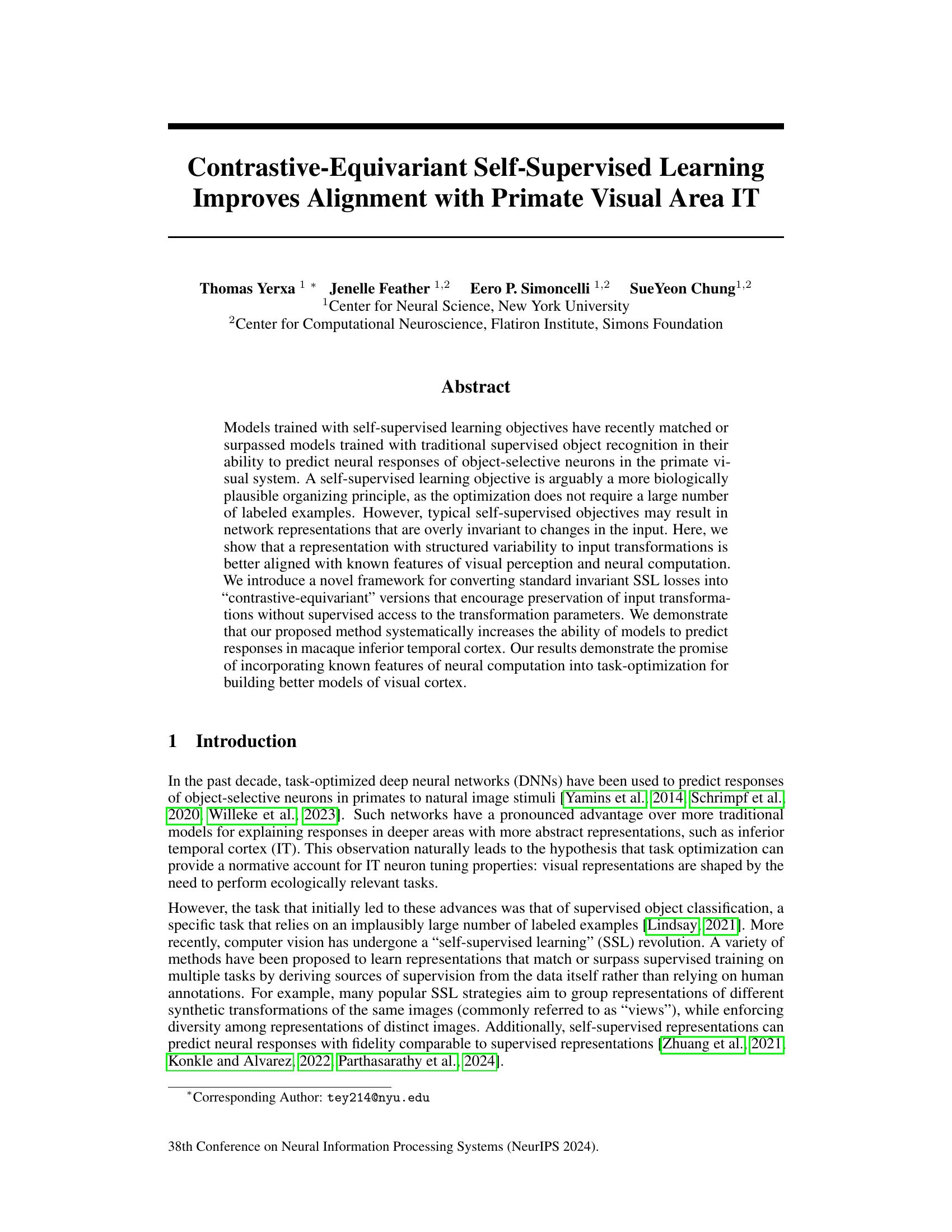

This figure illustrates the contrastive-equivariant self-supervised learning (CE-SSL) training method. The dataset is split into two halves. Each image in each half is augmented with the same transformation. The augmented images pass through a ResNet-50 network and then are projected into two embedding spaces, one for invariant and one for equivariant losses. The invariant loss is applied to the pairs of images. The equivariant loss is applied to the difference vector between transformation pairs.

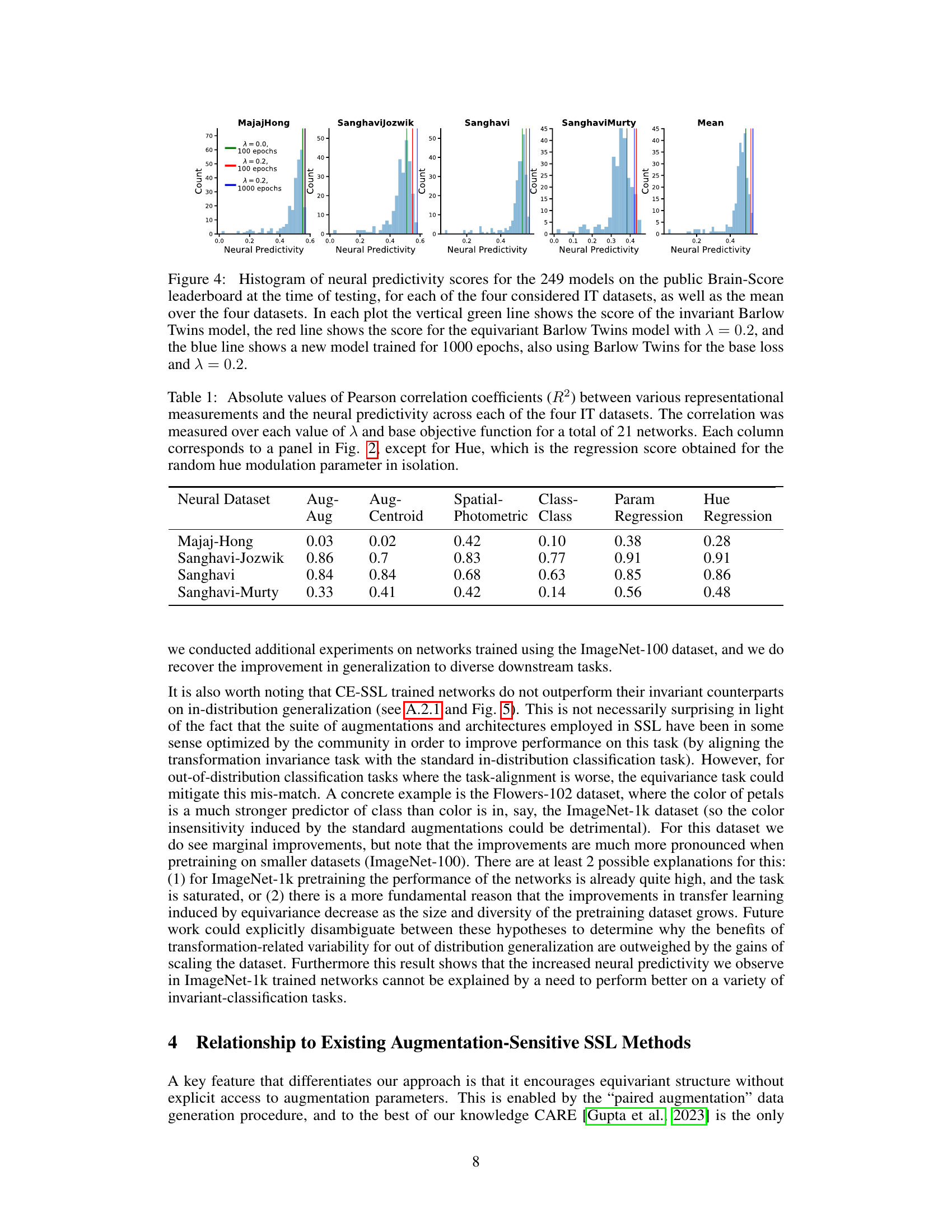

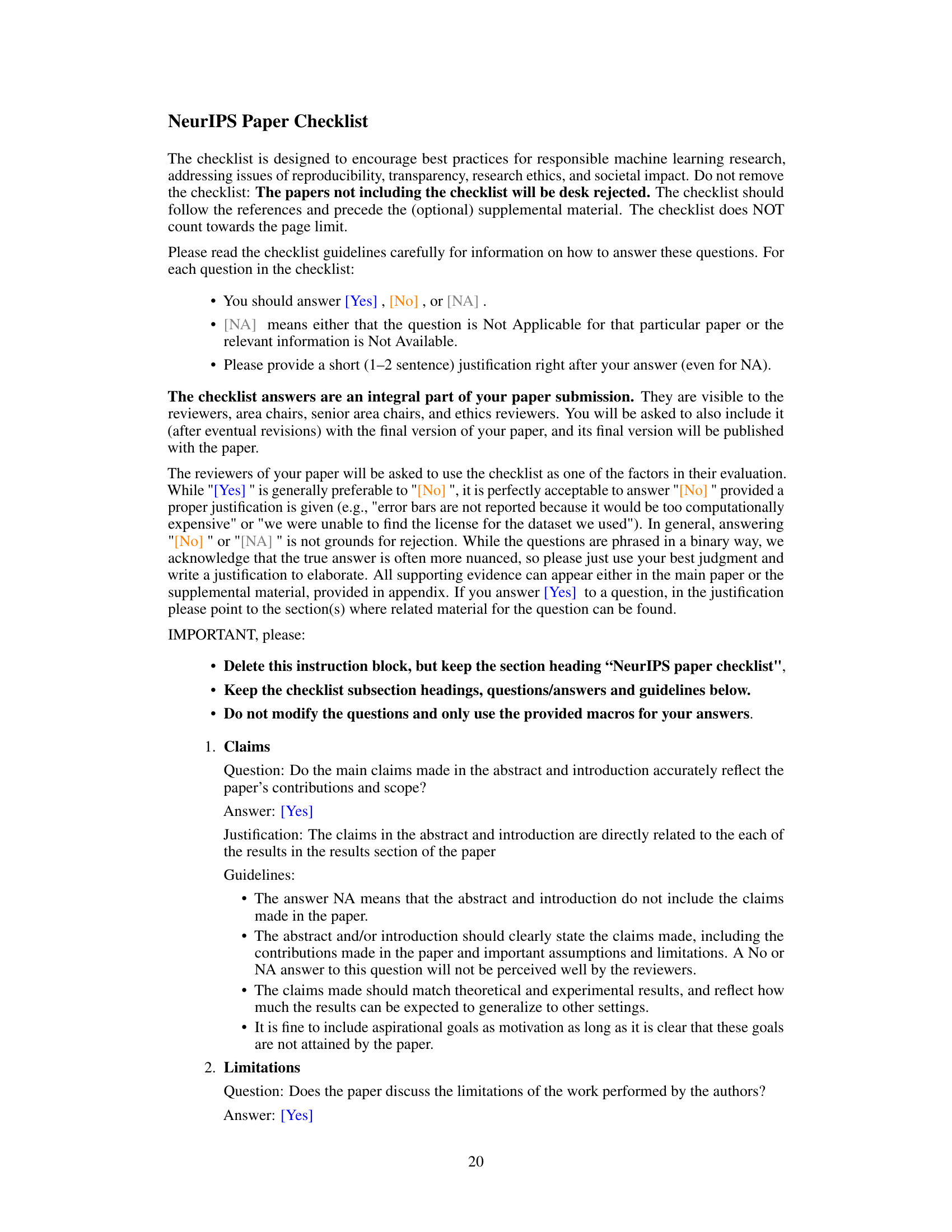

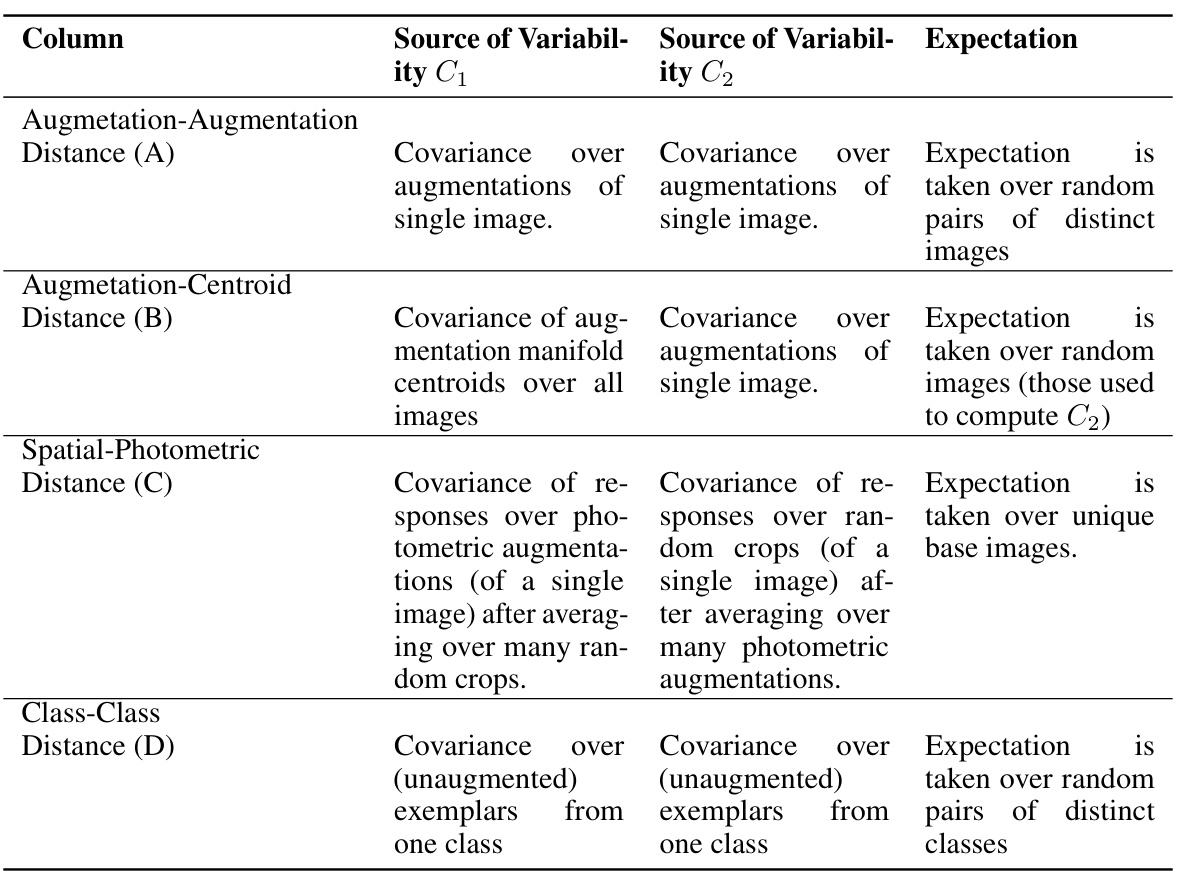

This table presents the Pearson correlation coefficients (R-squared values) between different representational measurements and the neural predictivity across four IT datasets. The representational measures include augmentation-augmentation distance, augmentation-centroid distance, spatial-photometric distance, class-class distance, and parameter regression scores. The neural predictivity is assessed using the BrainScore evaluation pipeline. A total of 21 networks were evaluated, varying both the base objective function and the hyperparameter λ (lambda), which controls the strength of the equivariance loss. The table helps to understand which representational characteristics contribute most to the model’s ability to predict neural activity.

In-depth insights#

Equivariant Self-SSL#

The proposed “Equivariant Self-SSL” framework offers a compelling approach to improve the alignment of self-supervised learning models with primate visual area IT. By converting standard invariant SSL losses into contrastive-equivariant versions, it encourages the preservation of input transformations without relying on supervised access to transformation parameters. This is a significant departure from traditional SSL methods, which often overemphasize invariance. The key innovation lies in the ability to induce structured variability in the representation, which is crucial for capturing the intricacies of visual perception. By explicitly incorporating this structured variability during training, the method demonstrably enhances the model’s capacity to predict neural responses in IT, surpassing models trained solely with invariance-based objectives. The use of contrastive-equivariant losses elegantly addresses the limitations of excess invariance in standard SSL, paving the way for the development of biologically more plausible and effective models of visual cortex. This work highlights the importance of integrating known features of neural computation into task-optimization. The proposed technique presents significant promise for advancing the field of self-supervised learning and creating more robust and accurate models of visual processing.

Neural Alignment#

The concept of “Neural Alignment” in the context of deep learning models and primate visual processing is crucial. The paper investigates how well model representations align with the actual neural activity in the primate brain, specifically area IT. A key finding is that models trained with contrastive-equivariant self-supervised learning (CE-SSL) show improved alignment compared to traditional invariance-based methods. This suggests that structured variability in the model’s responses to transformations, rather than complete invariance, is more biologically plausible and beneficial for predicting neural responses. The improved alignment is not simply due to better classification accuracy but also to the models learning to factorize variability across different aspects of the visual input and share transformation-related information between images. This work demonstrates the importance of incorporating biological insights when designing learning objectives to create more accurate and biologically-realistic models of the visual system. The success of CE-SSL highlights the potential benefits of incorporating known features of neural computation into task-optimization to enhance the performance and biological relevance of deep learning models.

Invariance Limits#

The concept of “Invariance Limits” in the context of deep learning models trained on visual data is crucial. It highlights the trade-off between achieving robust generalization (invariance to irrelevant transformations like rotation or lighting changes) and preserving relevant information (sensitivity to meaningful changes such as object identity). Overly invariant models may fail to capture subtle variations crucial for accurate perception and task performance, leading to decreased accuracy and a poor match with biological neural responses. Conversely, insufficient invariance might lead to models that are overly sensitive to noise and irrelevant details, again reducing performance and generalizability. A key challenge is developing methods that strike a balance, leveraging the benefits of invariance without sacrificing crucial discriminative information. This requires a nuanced understanding of the specific task and the types of variations that should be considered either invariant or informative. The research into “Invariance Limits” is essential for building more efficient and biologically plausible artificial visual systems. It suggests the need for more advanced training techniques and architectural designs that explicitly deal with the representation of structured variability, allowing a model to achieve both robustness and sensitivity as needed.

Representional Analysis#

The representational analyses section is crucial for validating the core claims of the paper. It leverages the Bures metric to meticulously quantify the factorization of variability within the learned representations. By examining the distances between augmentation manifolds, centroid manifolds, and spatial-photometric variabilities, the authors effectively demonstrate that their contrastive-equivariant self-supervised learning framework successfully promotes structured variability. This structured variability isn’t merely a byproduct but a critical component of aligning model representations to primate visual area IT. The analyses also highlight the emergent property of class manifold alignment and linear decodability of augmentation parameters, both of which further support the success of their approach in capturing biologically relevant features beyond basic invariance.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of contrastive-equivariant self-supervised learning (CE-SSL) is crucial. This involves investigating methods to balance the equivariant and invariant loss functions more effectively, potentially through adaptive weighting schemes or alternative architectural designs. Another area to explore is the generalizability of CE-SSL to different data modalities, beyond images. Applying the CE-SSL framework to audio, video, or text data could reveal valuable insights and advance research in these fields. Finally, a deeper understanding of the relationship between structured variability, transformation sensitivity, and neural predictivity needs to be investigated, potentially by comparing CE-SSL models to models trained using other methods on larger-scale neural datasets. This could lead to a better understanding of how to build more biologically plausible models of visual cortex.

More visual insights#

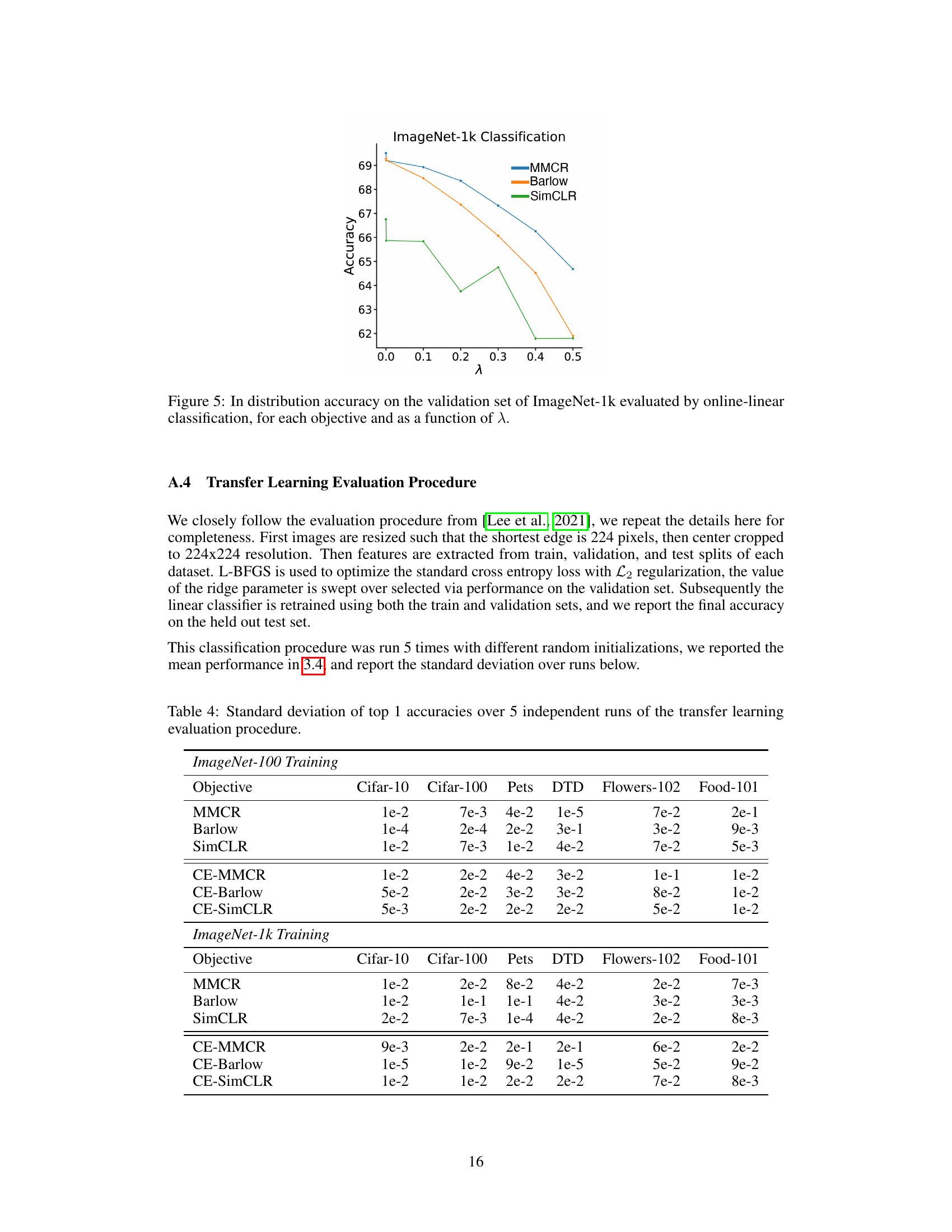

More on figures

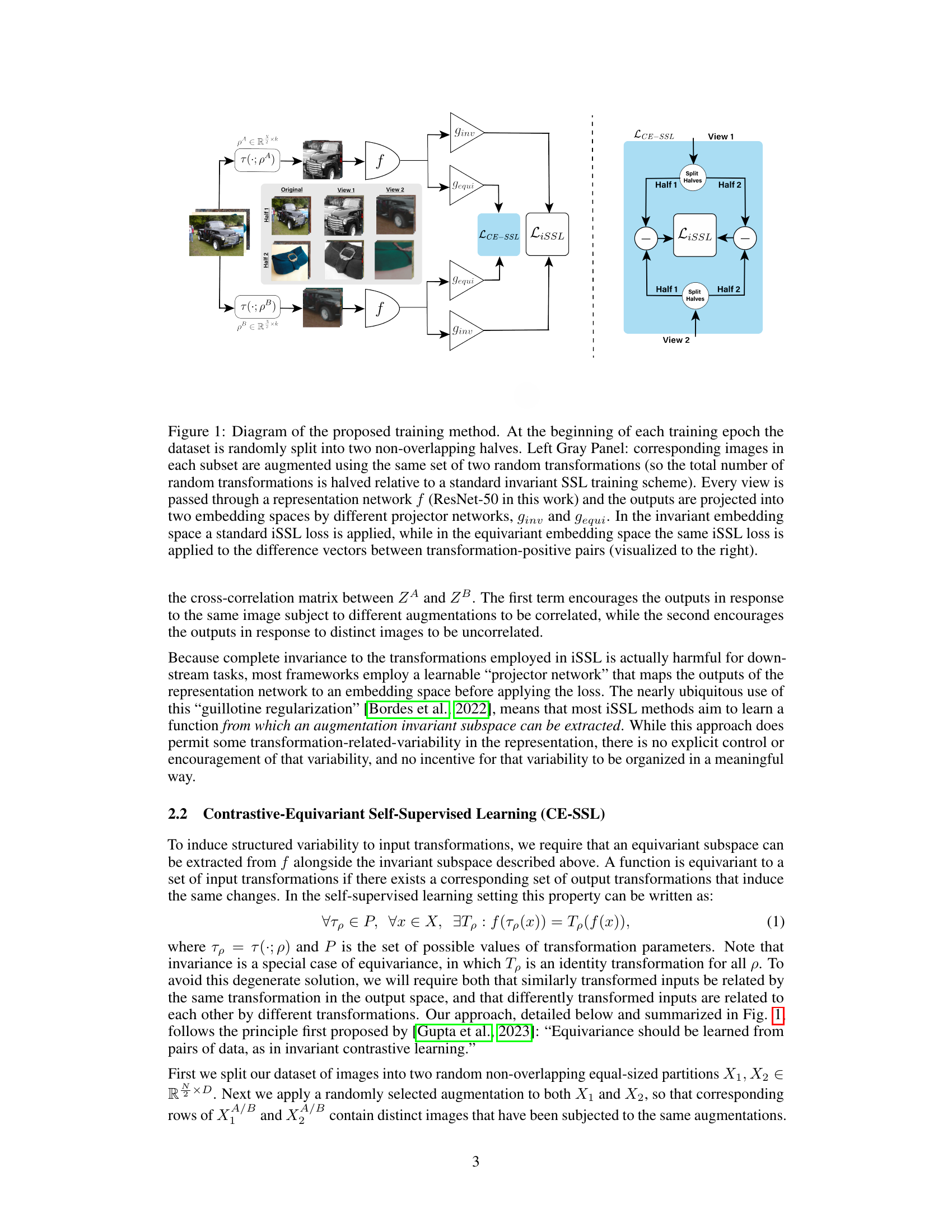

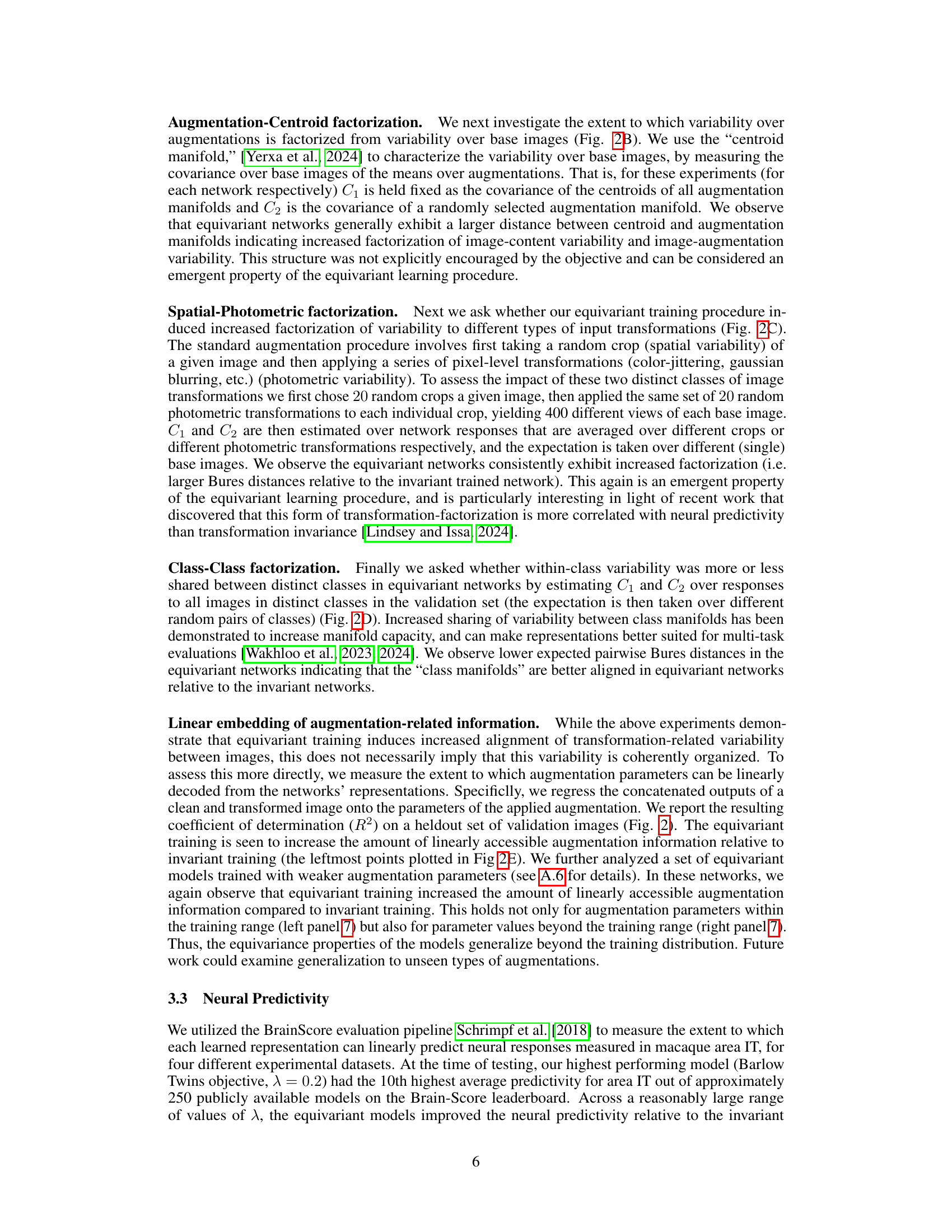

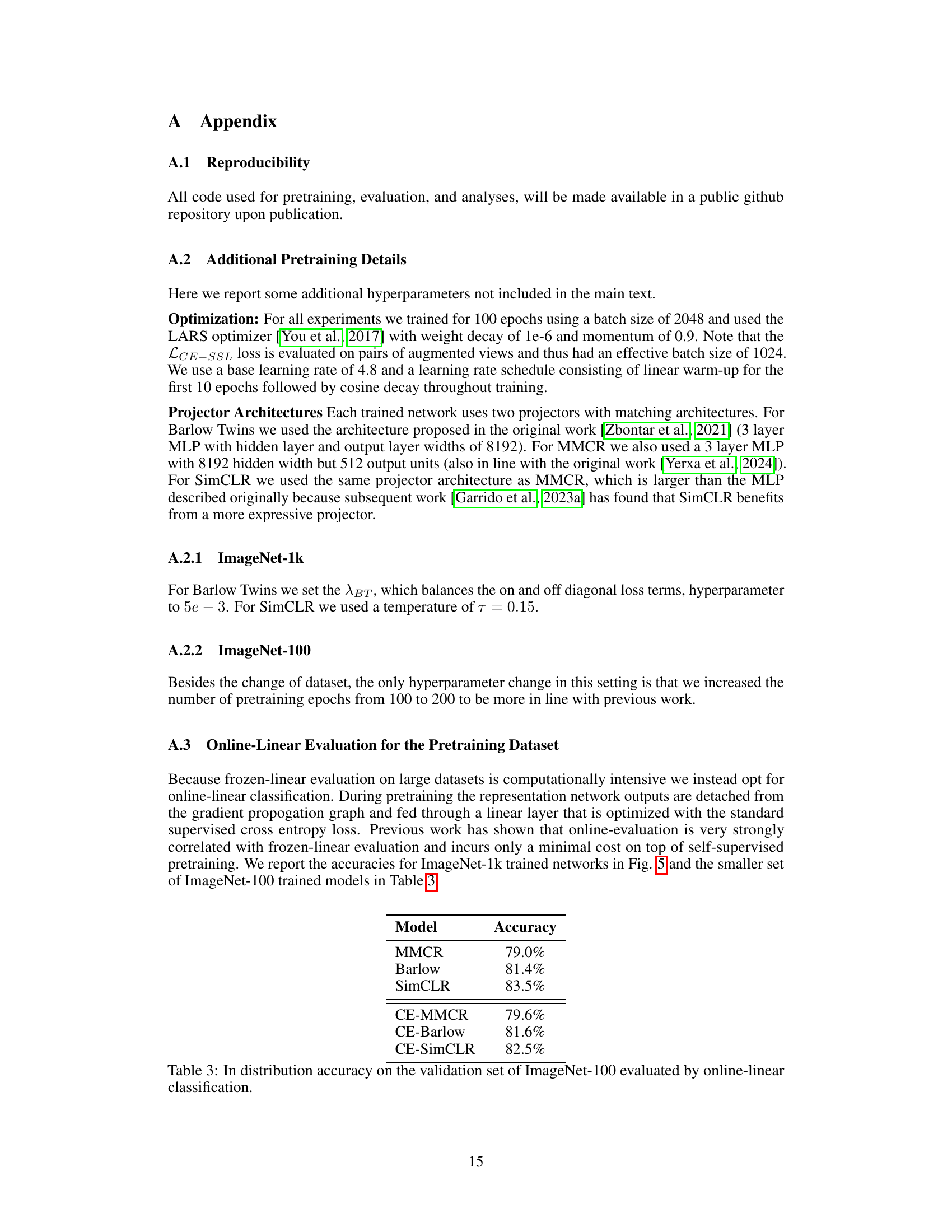

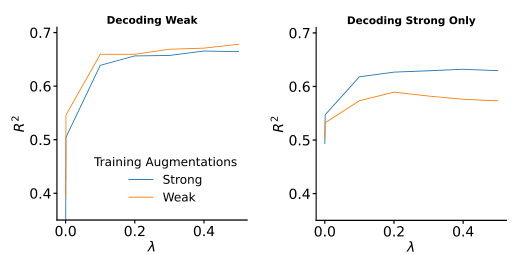

This figure presents a representational analysis of the model’s learned features. It shows how the model’s representation of images changes with the strength of the equivariance loss. The analysis uses several metrics (augmentation-augmentation distance, augmentation-centroid distance, spatial-photometric distance, and class-class distance) to quantify the structure and organization of the learned representations. It also shows the results of a parameter regression experiment, which assesses the model’s ability to predict neural responses based on the learned representations.

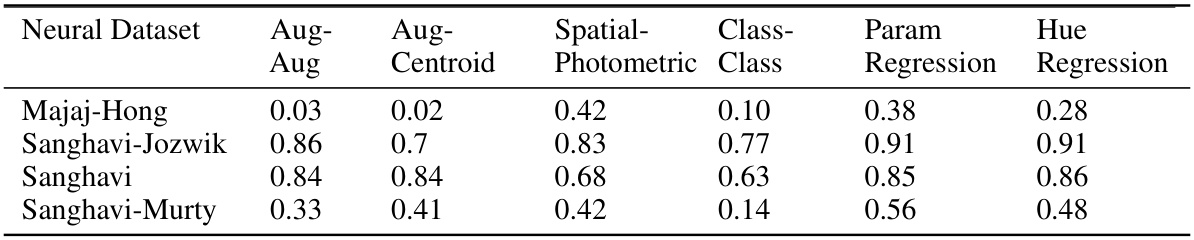

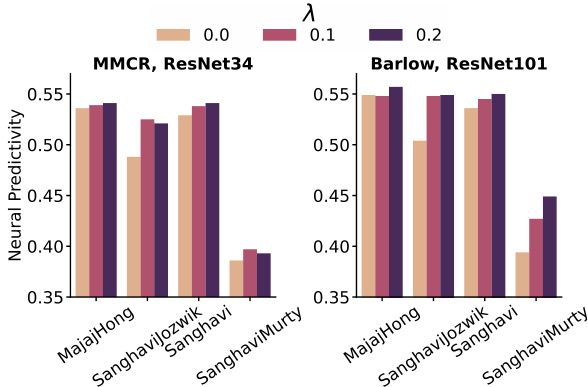

This figure displays the neural predictivity results for different values of lambda (λ), representing the strength of the equivariance loss. The x-axis represents four different IT datasets, and each group of bars represents different base objective functions (MMCR, Barlow Twins, SimCLR). The height of each bar indicates the neural predictivity score for a given dataset, objective function, and λ value. The results show that invariant networks (λ = 0) are generally outperformed by at least one of the equivariant networks for each dataset and objective function. Moreover, the improvement in predictivity varies significantly depending on the λ value, indicating the importance of the hyperparameter in balancing invariance and equivariance.

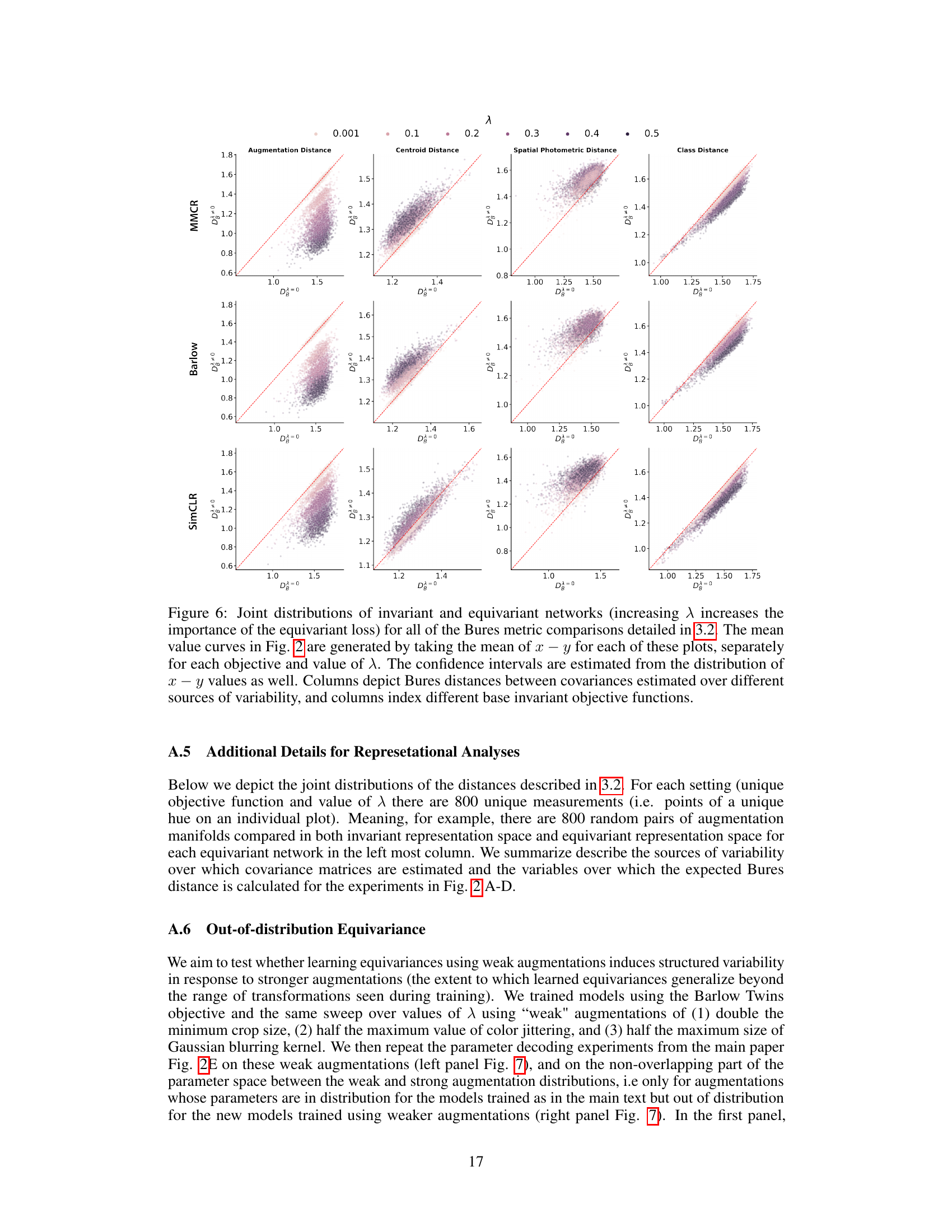

This figure presents representational analyses to determine the impact of the equivariance loss on the learned representations. It uses the Bures metric to quantify the relationships between different sources of variability (augmentation-augmentation, augmentation-centroid, spatial-photometric, class-class). The results show that incorporating the equivariance loss leads to a more structured and factorized representation of variability, aligning better with known features of visual perception.

This figure presents the results of representational analyses performed to evaluate the impact of the contrastive-equivariant self-supervised learning (CE-SSL) method on the structure of learned representations. It shows how different measures of variability (augmentation-augmentation distance, augmentation-centroid distance, spatial-photometric distance, and class-class distance) change with increasing emphasis on the equivariance loss (λ). The results suggest that CE-SSL leads to more structured variability, where different sources of variability are better factorized (orthogonal) from each other. A parameter regression experiment is also schematically shown.

This figure presents a series of representational analyses that investigate the impact of the proposed contrastive-equivariant self-supervised learning (CE-SSL) method on learned representations. It shows how different measures of variability (augmentation-augmentation distance, augmentation-centroid distance, spatial-photometric distance, and class-class distance) change as the importance of the equivariance loss (λ) is increased. Additionally, a schematic of the parameter regression experiment used to evaluate the linearly decodable information regarding augmentations is shown. The results are presented as line plots for each comparison, illustrating the relationship between the Bures metric distance and λ across multiple base objectives (MMCR, Barlow Twins, and SimCLR).

This figure presents a series of representational analyses to determine how variability in the dataset is organized in both invariant and equivariant networks. It shows the Bures distance (a measure of the distance between Gaussian distributions) between different sources of variability, such as augmentation-augmentation, augmentation-centroid, spatial-photometric, and class-class. The results demonstrate that incorporating an equivariance loss leads to factorized variability (i.e., different sources of variability are more orthogonal), which is further supported by a parameter regression experiment showing that augmentation parameters can be linearly decoded more effectively from equivariant networks.

More on tables

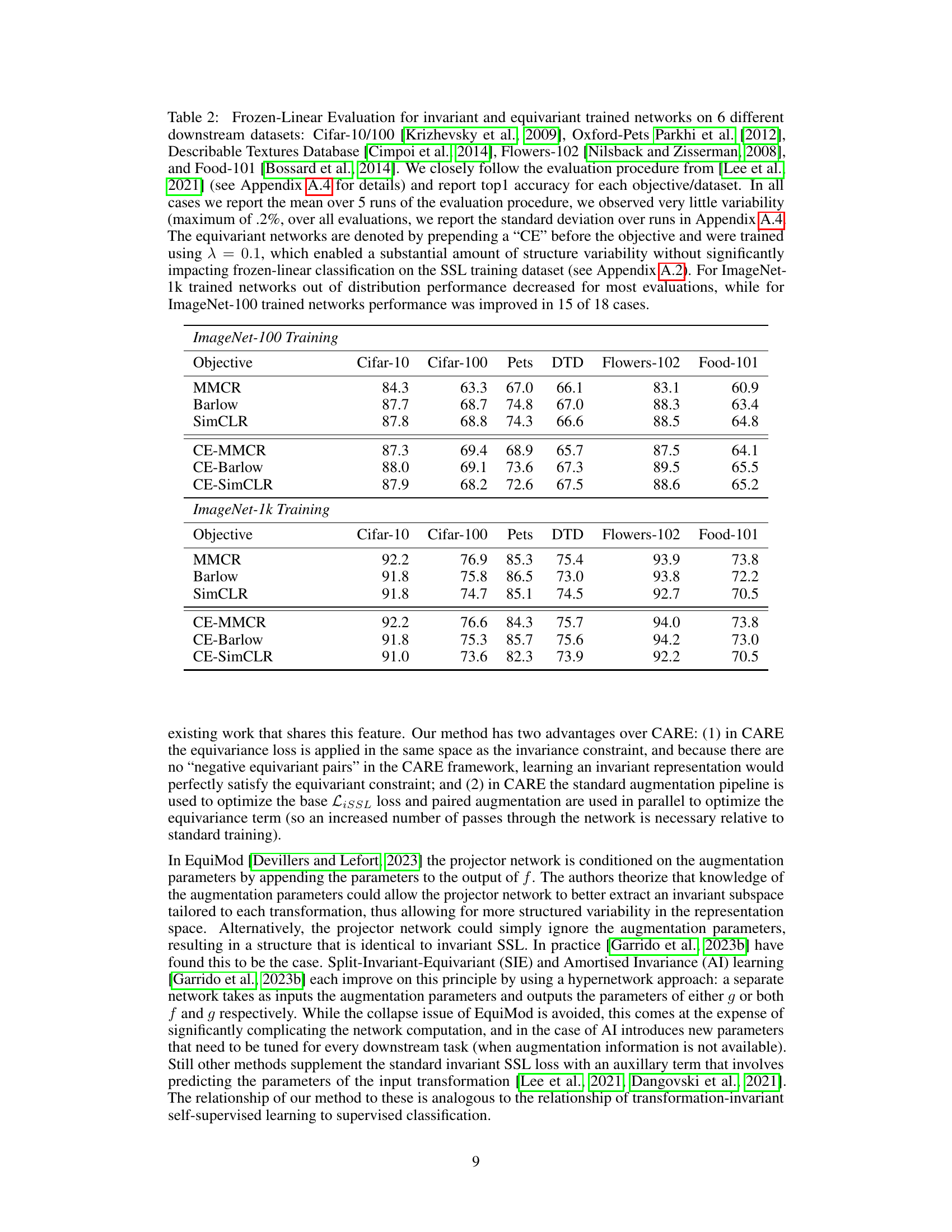

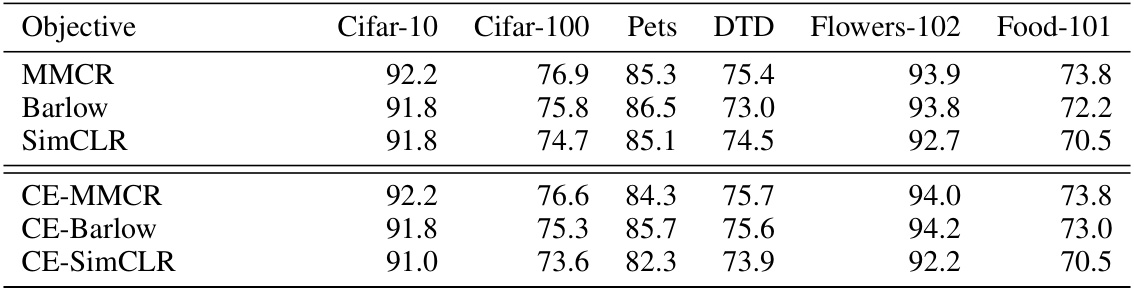

This table presents the results of a frozen linear evaluation comparing the performance of invariant and equivariant self-supervised learning models on six different downstream datasets. The table shows the top-1 accuracy for each model (invariant and equivariant versions of MMCR, Barlow Twins, and SimCLR) on each dataset, highlighting the impact of incorporating equivariance into the self-supervised learning framework. The results are averaged across five independent runs, with standard deviations reported in the appendix.

This table presents the top-1 accuracy results of frozen linear evaluation on six different downstream datasets (Cifar-10, Cifar-100, Oxford-Pets, Describable Textures Database, Flowers-102, Food-101) for both invariant and equivariant trained networks. The equivariant networks were trained with a hyperparameter λ = 0.1, balancing invariance and equivariance. The table compares performance across different self-supervised learning objectives (MMCR, Barlow Twins, SimCLR) and shows the impact of incorporating equivariance on transfer learning capabilities for ImageNet-100 and ImageNet-1k pretrained models.

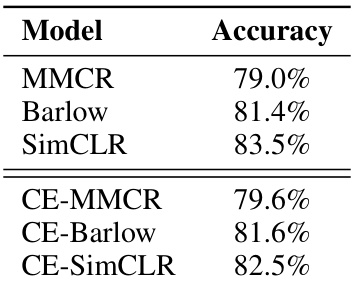

This table shows the results of online linear classification on the ImageNet-100 validation set. It compares the performance of three different self-supervised learning methods (MMCR, Barlow Twins, and SimCLR) with their contrastive-equivariant counterparts (CE-MMCR, CE-Barlow, CE-SimCLR). The accuracy of each model is presented as a percentage.

This table presents the results of a transfer learning experiment, comparing the performance of invariant and equivariant trained networks on six different downstream datasets. It shows the top-1 accuracy for each objective function (MMCR, Barlow Twins, SimCLR) and training dataset (ImageNet-100, ImageNet-1k), with and without the addition of an equivariance loss. The results highlight the impact of incorporating equivariance on the generalization capability of the models.

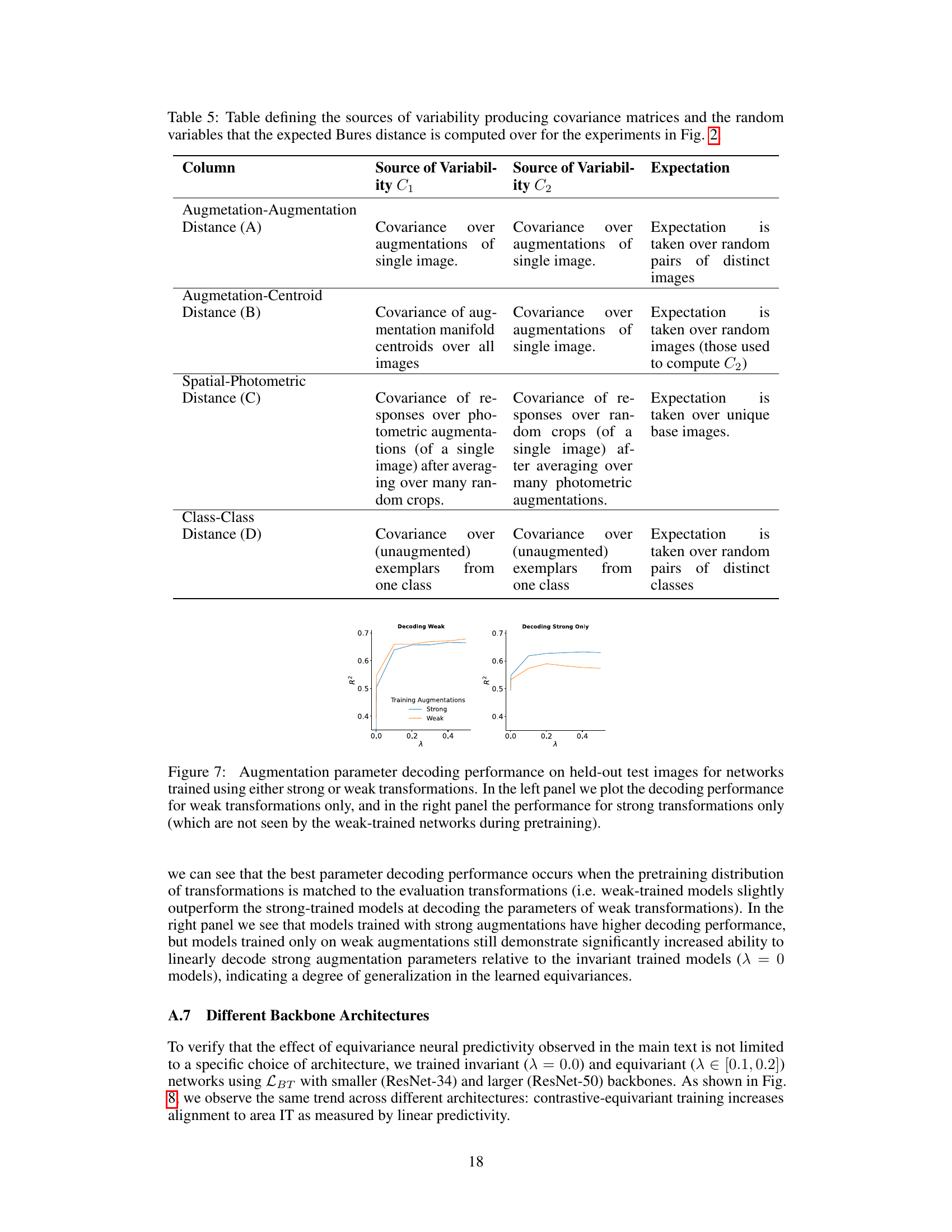

This table details the sources of variability used to calculate the covariance matrices (C1 and C2) and the random variables used to compute the expected Bures distance for the representational analyses in Figure 2 of the paper. It clarifies how the covariance matrices are derived based on augmentations of images and how the expected Bures distance is calculated for each type of comparison (augmentation-augmentation, augmentation-centroid, spatial-photometric, and class-class).

Full paper#