↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) are promising for quantum computing, but effectively integrating hard constraints into VQAs remains a challenge. Current methods often use penalty terms, which can be inefficient. This research addresses this by combining the Hamming Weight Preserving (HWP) ansatz with a parity check mechanism. The HWP ansatz keeps the number of non-zero elements in the quantum state constant, while parity checks detect and correct errors, improving accuracy and robustness.

This combined approach significantly outperforms existing VQA methods on both quantum chemistry and combinatorial optimization problems (e.g., Quadratic Assignment Problem). The researchers tested their method on both simulators and superconducting quantum processors, confirming its effectiveness and demonstrating its potential for solving more realistic, constrained problems. The method uses a cascade of CNOT gates for the parity check, making it suitable for NISQ devices. The results showcase a promising path towards achieving quantum advantage in the NISQ era by directly incorporating hard constraints into the algorithm.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in quantum computing and optimization. It introduces a novel approach to integrating hard constraints into variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), a significant challenge in the field. The method’s success on quantum chemistry and combinatorial optimization problems, demonstrated via simulations and real quantum hardware, highlights its potential to accelerate VQA applications and further investigation into VQA-based solutions for realistic, constrained problems.

Visual Insights#

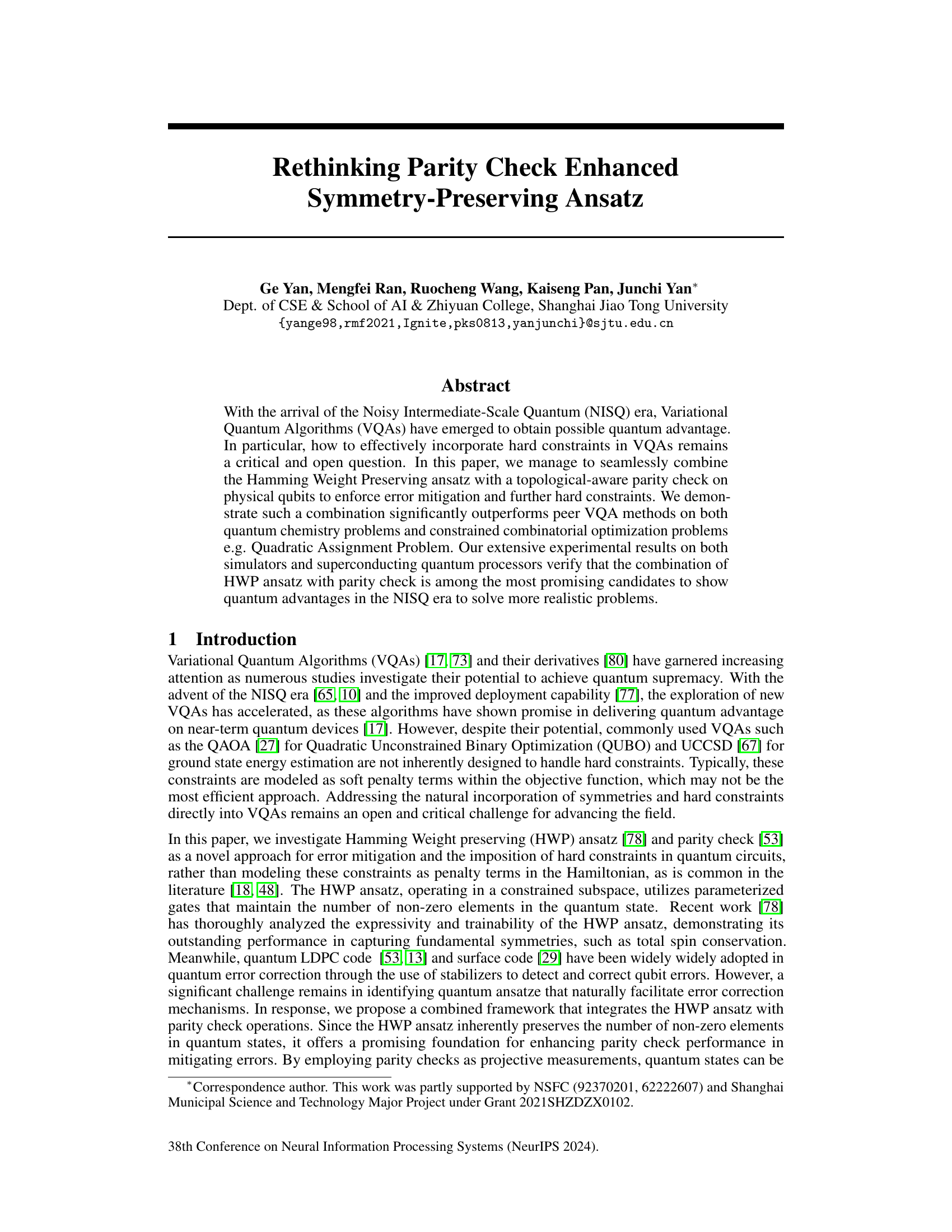

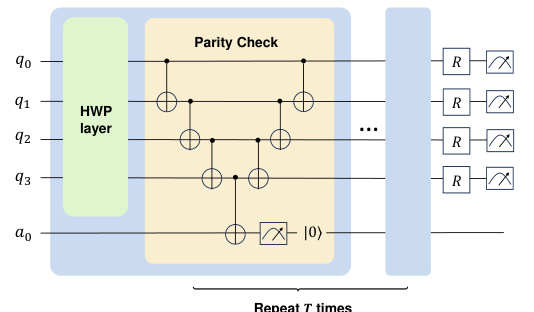

The figure illustrates the circuit structure that combines parity checks and the Hamming Weight Preserving (HWP) ansatz. It shows a series of HWP layers applied to the qubits (q0-q3), followed by a parity check block. The parity check block consists of a series of CNOT gates which measure the parity of the qubits and store it in an ancilla qubit (a0). This block is repeated ‘T’ times to continuously monitor and mitigate errors. The resulting parity information helps in correcting errors and enforcing constraints. The figure is relevant to the use of parity checks as an error mitigation method for the HWP ansatz in quantum circuits.

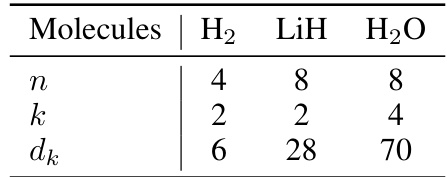

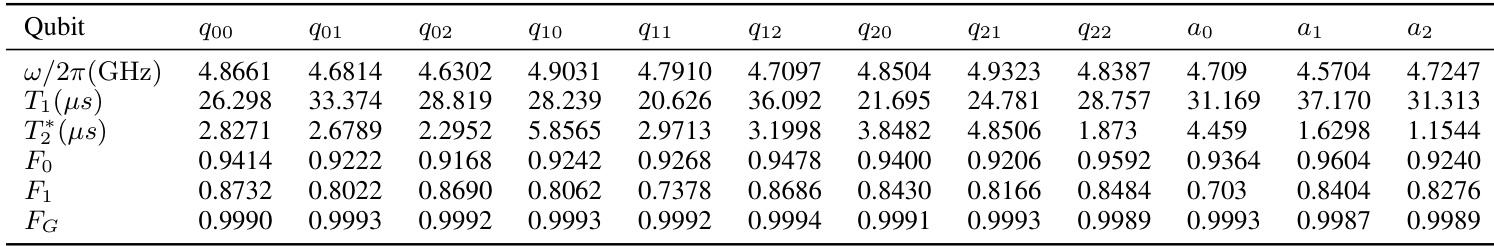

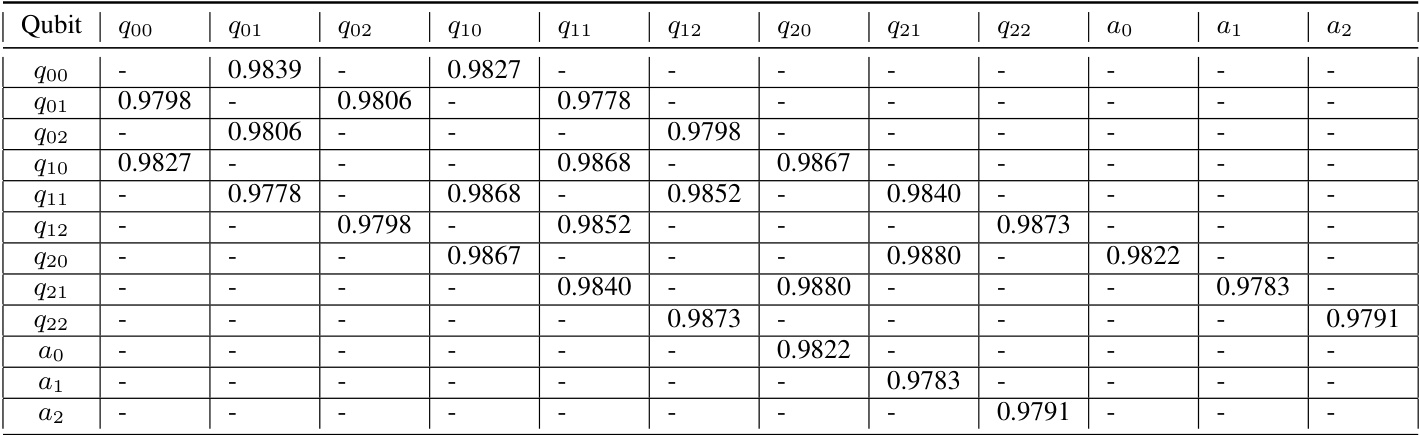

This table shows the number of orbitals (n), electrons (k), and the dimension of the Hamming Weight Preserving (HWP) subspace (dk) for three different molecules: Hydrogen (H2), Lithium Hydride (LiH), and Water (H2O). These values are used in the simulated experiments on state preparation in the paper.

In-depth insights#

Parity Check’s Role#

The research paper explores parity checks’ multifaceted role in enhancing variational quantum algorithms (VQAs). Error mitigation is a primary function; parity checks, implemented as a cascade of CNOT gates, continuously monitor qubit states for bit-flip errors, correcting them within the quantum circuit and improving the reliability of results, especially for deeper circuits. Beyond error correction, parity checks are ingeniously used to enforce hard constraints, extending the capabilities of the Hamming Weight Preserving (HWP) ansatz. By incorporating parity checks alongside HWP, the algorithm effectively restricts the search space to only those states meeting problem-specific constraints, significantly boosting the efficiency of solving constrained optimization problems like the Quadratic Assignment Problem (QAP). This integrated approach, combining error mitigation with constraint enforcement, emerges as a highly promising candidate to achieve quantum advantage in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. The seamless integration of parity checks within the quantum circuit, avoiding the need for post-processing steps, further enhances the overall efficiency. Finally, the paper’s experimental validation on both simulators and real quantum hardware demonstrates the significant practical advantages of this integrated approach.

HWP Ansatz Enhancements#

The concept of “HWP Ansatz Enhancements” in a quantum computing context likely refers to improvements and extensions of the Hamming Weight Preserving (HWP) ansatz. This ansatz, which maintains a constant number of non-zero elements in quantum states, offers advantages in mitigating errors and enforcing hard constraints. Enhancements could involve several key areas. First, improved gate designs might focus on creating more universal or efficient HWP gates, increasing expressivity and reducing circuit depth. Second, integration with error mitigation techniques such as parity checks or quantum error correction codes could significantly enhance the robustness of the ansatz, particularly on noisy quantum hardware. Third, novel applications of the enhanced HWP ansatz could target complex problems in areas like combinatorial optimization, where enforcing hard constraints is crucial. The exploration of different parametrizations of the HWP ansatz to enhance its performance on various quantum hardware platforms could also be a direction for “HWP Ansatz Enhancements”. Finally, theoretical analysis regarding the expressivity and trainability of the enhanced ansatz would provide valuable insights and guide further development.

QAP & TSP Experiments#

The QAP & TSP experiments section would likely detail the empirical evaluation of the proposed methods on Quadratic Assignment Problems (QAP) and Traveling Salesperson Problems (TSP). It would likely present results comparing the performance of the novel HWP ansatz with parity checks against existing baselines (e.g., QAOA, HEA, XYMixer). Key aspects would be the approximation ratio, indicating how close the algorithm gets to the optimal solution, and the probability of obtaining optimal or near-optimal solutions. The experiments would likely involve simulations on classical computers and, ideally, real-world quantum hardware. For the quantum experiments, the results would need to demonstrate quantum advantage compared to classical algorithms; and error mitigation strategies using parity checks would be critical to showcase robustness and resilience to noise inherent in NISQ devices. The discussion would include an analysis of how the problem size (number of facilities/cities), connectivity of the qubits, and choice of ansatz parameters affect the performance. The section would conclude by summarizing the key findings, highlighting the strengths and limitations of the approach on different types of problems. Scalability of the methodology would also be a key consideration.

NISQ Era Advantages#

The NISQ era, bridging the gap between classical and fault-tolerant quantum computing, presents unique advantages. Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) are central to this, allowing the exploration of quantum advantage on near-term hardware. However, effectively incorporating hard constraints within VQAs remains a challenge. This is where methods like the Hamming Weight Preserving (HWP) ansatz combined with topological-aware parity checks show promise. HWP inherently preserves symmetries, simplifying the implementation of constraints and enhancing error mitigation. Parity checks, acting as projective measurements, further refine the state space, reducing errors and ensuring the algorithm operates within the desired constrained subspace. This approach demonstrates significant performance improvements in solving complex problems, such as the Quadratic Assignment Problem (QAP), where the combination of HWP and parity checks provides a robust and efficient error-mitigation mechanism and hard constraint enforcement. This synergy allows VQAs to tackle more realistic, complex problems, showing potential for quantum advantage even within the limitations of current noisy intermediate-scale quantum technology.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this parity check enhanced symmetry-preserving ansatz could explore several promising avenues. Extending the approach to handle inequality constraints beyond the current focus on equality constraints is crucial for tackling a broader range of real-world problems. Investigating different parity check strategies and their impact on error mitigation would refine the method’s robustness and efficiency. Exploring hybrid classical-quantum algorithms, incorporating classical optimization techniques to complement the quantum ansatz, is also warranted. Furthermore, a deeper study into the expressiveness and limitations of the HWP ansatz is needed to better understand its scope and potential for quantum advantage. Finally, benchmarking against a wider range of quantum computing hardware beyond the superconducting processors used in the study would provide crucial insights into the method’s portability and scalability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

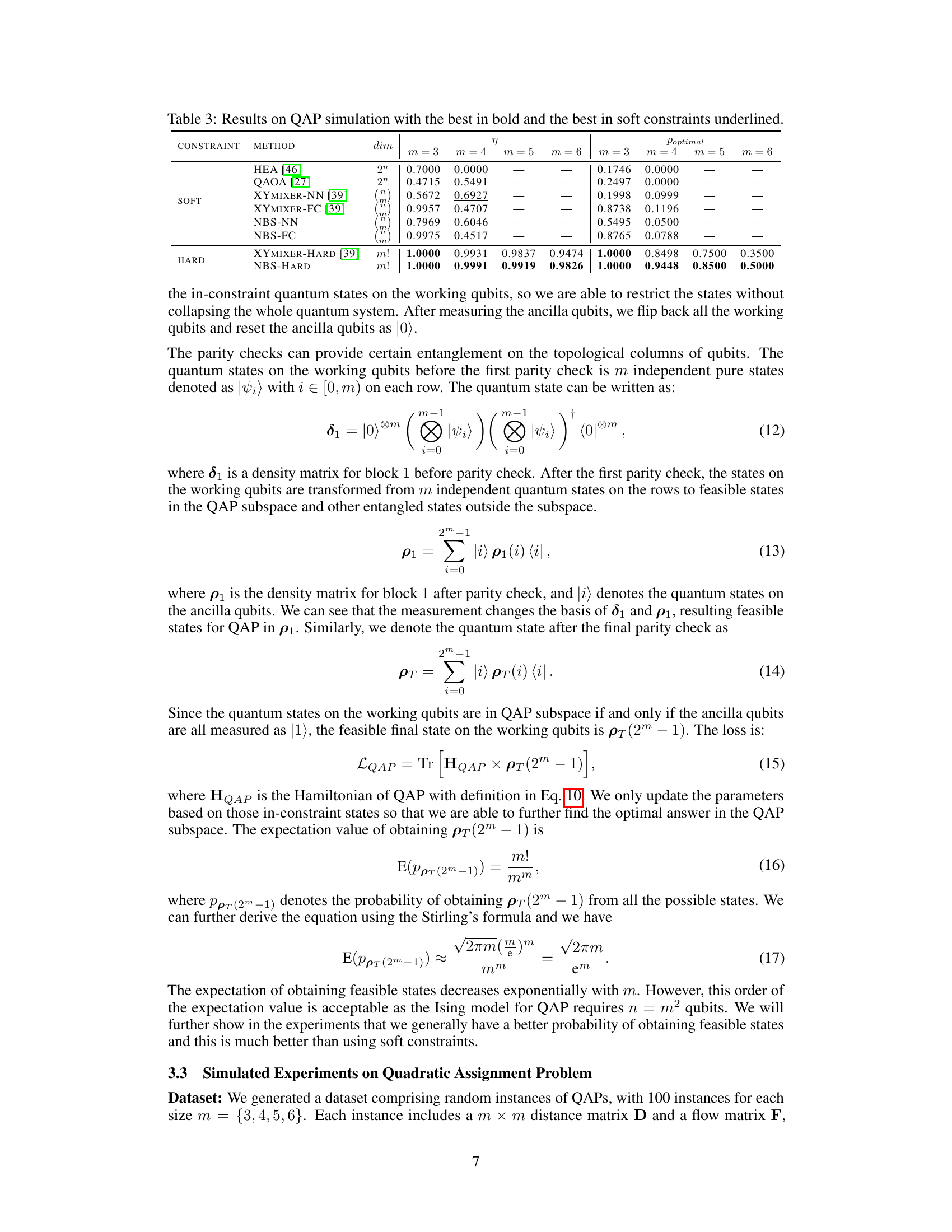

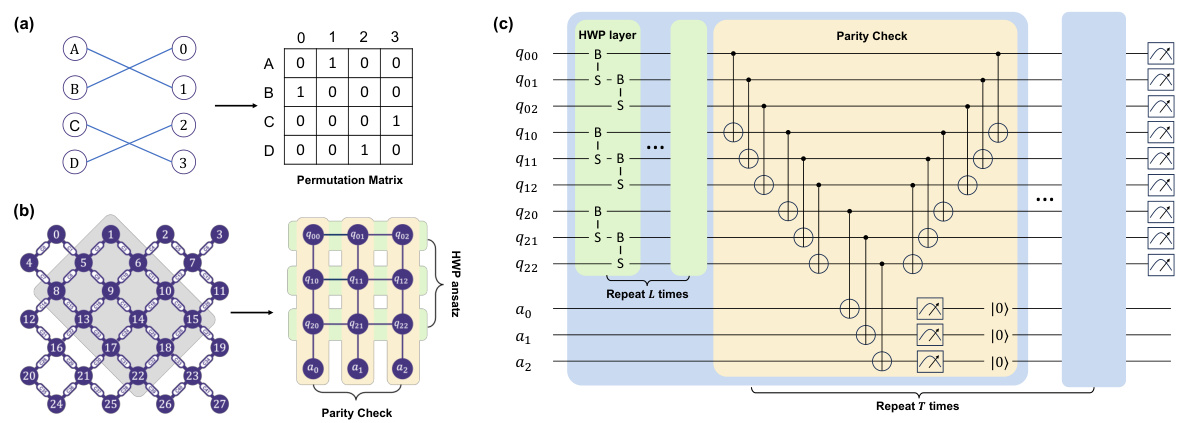

This figure illustrates the mapping of a QAP instance to a quantum circuit. (a) shows a 4x4 permutation matrix representing the assignment of facilities to locations. (b) depicts the physical qubit topology of a superconducting quantum processor, showing how the qubits are connected and how they are mapped to the permutation matrix. (c) presents the complete quantum circuit, incorporating HWP layers and parity checks to enforce constraints and mitigate errors, designed to solve the QAP.

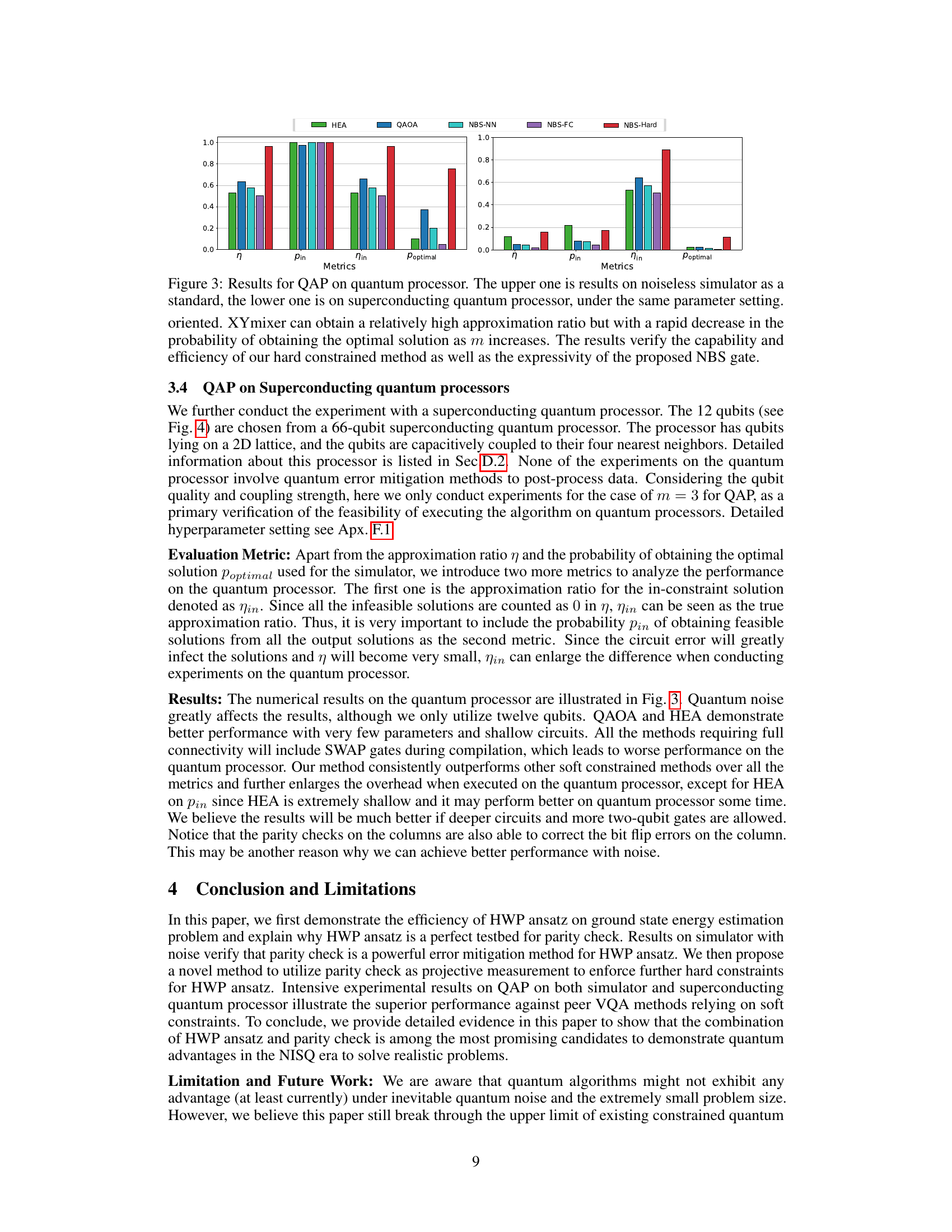

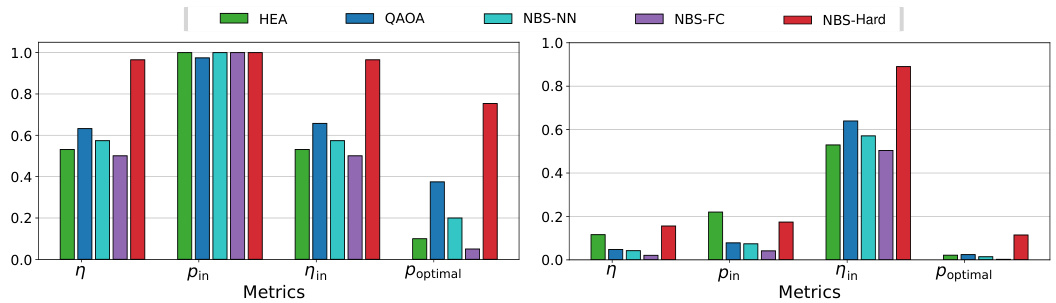

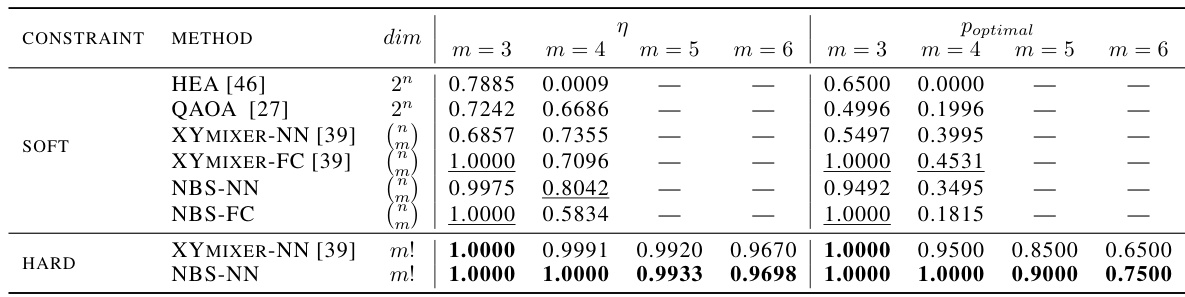

This figure presents a comparison of results for the Quadratic Assignment Problem (QAP) obtained using different methods, both on a noiseless simulator and a real superconducting quantum processor. The upper half shows the results from the simulator without noise, which serves as a baseline. The lower half shows the results from the actual quantum processor which includes the effects of noise. The results from both are shown to allow for comparison. Metrics shown include the approximation ratio (η), the probability of obtaining feasible solutions (pin), the approximation ratio for in-constraint solutions (Nin), and the probability of obtaining the optimal solution (Poptimal). The methods compared are HEA, QAOA, NBS-NN, NBS-FC, and NBS-Hard.

This figure illustrates the mapping of a Quadratic Assignment Problem (QAP) instance to a quantum processor. (a) shows a 4x4 permutation matrix representing the assignment of facilities to locations. (b) depicts the physical qubit topology of a superconducting quantum processor used for solving the QAP. (c) presents the overall quantum circuit incorporating Hamming Weight Preserving (HWP) ansatz and parity checks for enforcing constraints and mitigating errors.

This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of the hyperparameters used in the paper. Specifically, it presents the results of sensitivity studies on the penalty weight (α) and the number of parity checks (T) for different configurations of the XYmixer and NBS-NN algorithms, used to solve the Quadratic Assignment Problem (QAP). The plots display the approximation ratio (η), the probability of obtaining feasible solutions (pin), the approximation ratio of feasible solutions (nin), and the probability of obtaining the optimal solution (poptimal) as functions of α and T for several problem sizes.

This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of two hyperparameters in the proposed QAP algorithm: penalty weight α and number of parity checks T. The plots illustrate how changes in these parameters affect the approximation ratio (η), probability of obtaining feasible states (pin), approximation ratio for in-constraint states (ηin), and probability of obtaining optimal solution (poptimal). Different subfigures correspond to different combinations of QAP size (m) and qubit topology (NN or FC). The results demonstrate the importance of finding the right balance of these hyperparameters to achieve better results in constrained combinatorial optimization.

More on tables

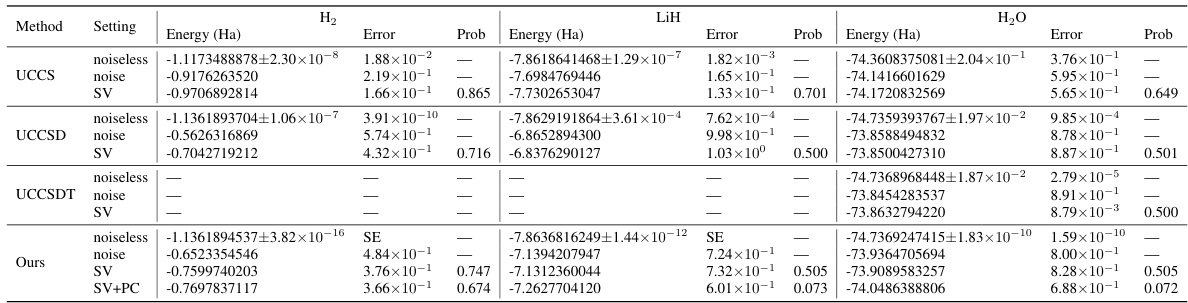

This table presents the numerical results for the ground state energy estimation of three molecules (H₂, LiH, and H₂O) using different methods: UCC with single, double, and triple excitations; and the proposed HWP ansatz with and without parity checks. For each method and molecule, the table shows the energy error relative to the Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) energy, the success probability of symmetry verification (SV), and the success probability of parity check (PC). The ‘SE’ values represent energy errors smaller than 10⁻¹⁰. The results illustrate the impact of noise on the accuracy of each method and the effectiveness of parity checks in mitigating errors.

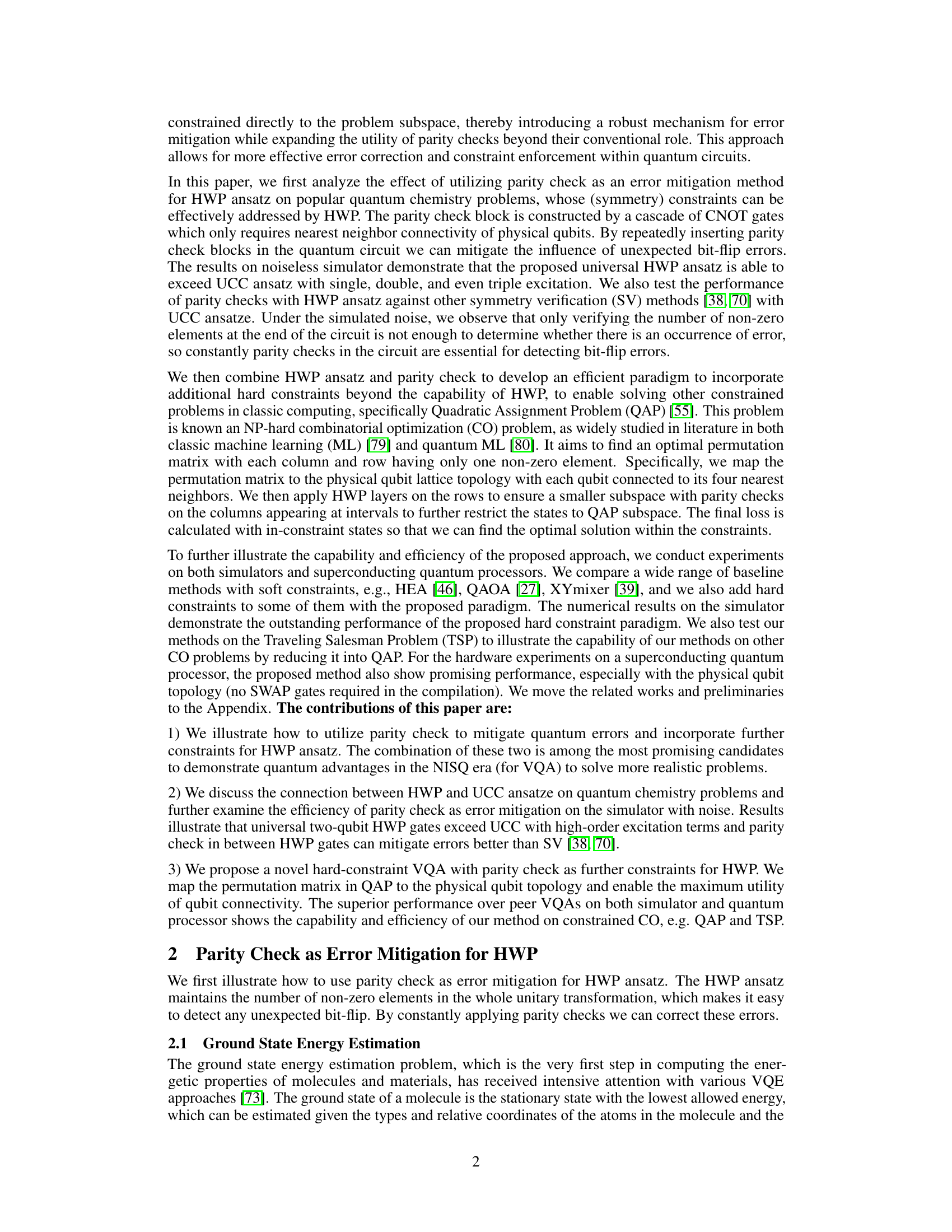

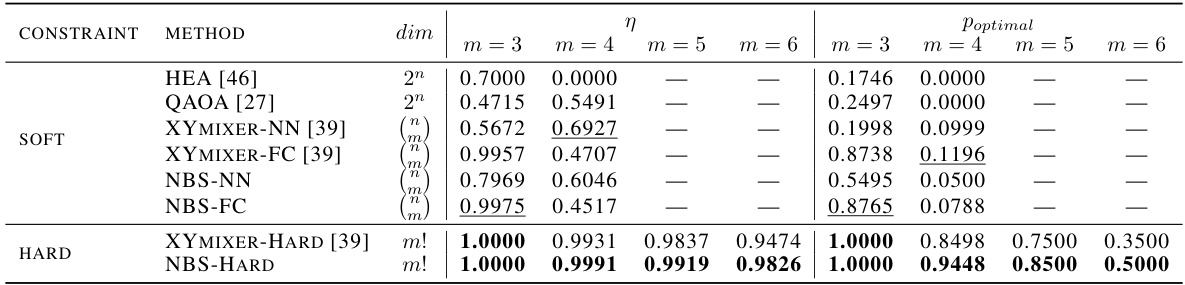

This table presents the results of QAP simulations, comparing various methods with both soft and hard constraints. The ‘CONSTRAINT’ column indicates whether soft or hard constraints were used. The ‘METHOD’ column lists different optimization algorithms. The ‘dim’ column shows the dimension of the search space for each method. The η values represent the approximation ratio (how close the solution is to the optimal one), while Poptimal is the probability of obtaining the optimal solution. Results for different problem sizes (m=3,4,5,6) are shown, highlighting the best-performing methods in each category.

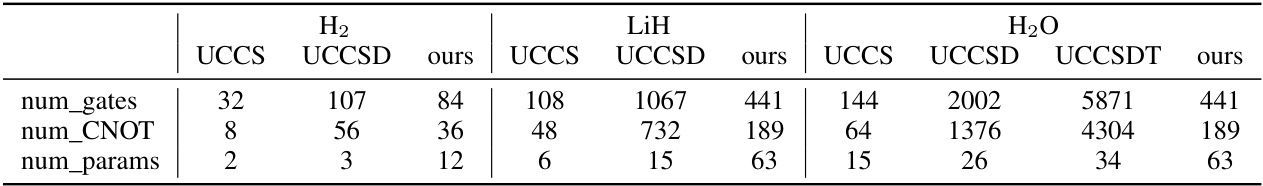

This table presents the numerical results of state preparation experiments using different methods (UCCS, UCCSD, UCCSDT, and the proposed method) under both noiseless and noisy conditions. It compares the energy errors, success probabilities of symmetry verification (SV) and parity checks (PC), and the final energies obtained. The results are shown for three molecules: H2, LiH, and H2O.

This table presents the numerical results for the ground state energy estimation task on three molecules (H2, LiH, and H2O). It compares the performance of various methods: UCC with different excitation levels, and the proposed HWP ansatz with and without parity checks (PC). The ‘Error’ column shows the energy error relative to the exact Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) energy. The ‘Prob’ column indicates the success rate of symmetry verification (SV) and parity check methods, and ‘SE’ represents values below a threshold of 10⁻¹⁰. This table demonstrates the impact of parity checks on error mitigation and the overall accuracy of the HWP ansatz, especially in noisy conditions.

This table presents the numerical results for the ground state energy estimation using different methods. The ‘Error’ column shows the energy error compared to the Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) method, which is the most accurate method for calculating ground state energy. The ‘prob’ column shows the success rate of the Symmetry Verification (SV) and Parity Check (PC) methods for error mitigation. ‘SE’ indicates that the energy error is less than 10⁻¹⁰.

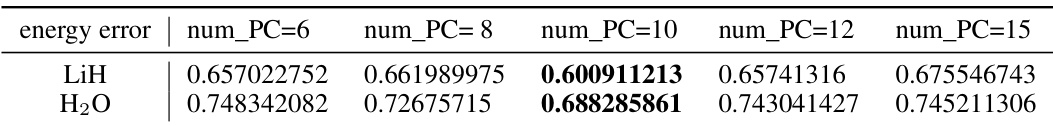

This table presents the results of a sensitivity analysis conducted to determine the optimal number of parity checks to use with the Hamming Weight Preserving (HWP) ansatz. The analysis was performed using different numbers of parity checks (num_PC) for the LiH and H2O molecules. The results are presented in terms of the energy error. The best performance, indicated by the lowest energy error, is highlighted in bold for each molecule, allowing for a determination of the optimal number of parity checks to balance error mitigation and computational cost.

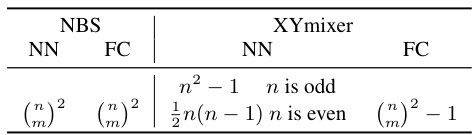

This table presents a comparison of the proposed HWP ansatz with UCC ansatze (UCCS, UCCSD, UCCSDT) across three molecules (H2, LiH, H2O). For each ansatz and molecule, it provides the number of gates, the number of CNOT gates, and the number of parameters. The data illustrates the computational cost associated with each approach and the trade-off between accuracy and resource consumption.

This table presents the results of QAP simulations using various methods, comparing performance with and without hard constraints. The ‘dim’ column shows the dimensionality of the solution space explored by each method. The η values represent the approximation ratio, indicating how close the solution is to the optimal solution. Poptimal represents the probability of obtaining the optimal solution. The table highlights the superior performance of methods incorporating hard constraints, particularly the NBS-HARD method, which consistently achieves higher η and Poptimal values across different problem sizes (m). The soft-constraint methods are underlined for easy comparison.

Full paper#