↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) struggle with complex multi-step reasoning, particularly arithmetic. This is partly due to their difficulty in tracking digit positions within large numbers. Existing methods, like reversing digit order or using index hints, have only yielded limited improvements. These approaches can harm generalization and increase the computational burden.

This paper proposes a novel solution: Abacus Embeddings. These embeddings encode the relative position of each digit within a number, allowing the model to effectively align digits for arithmetic operations. The researchers combine these embeddings with architectural modifications, such as input injection and recurrent layers, to achieve significant performance gains. Their experiments show state-of-the-art generalization on addition problems, achieving 99% accuracy on 100-digit numbers after training on only 20-digit numbers. These improvements also extend to other algorithmic tasks, demonstrating the method’s broader applicability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with transformer models for algorithmic reasoning. It directly addresses the limitation of transformers in handling long numerical sequences, offering valuable insights and solutions for improving model performance on arithmetic and similar tasks. The proposed Abacus Embeddings and architectural modifications open new avenues for research on improving the general numerical reasoning capabilities of LLMs.

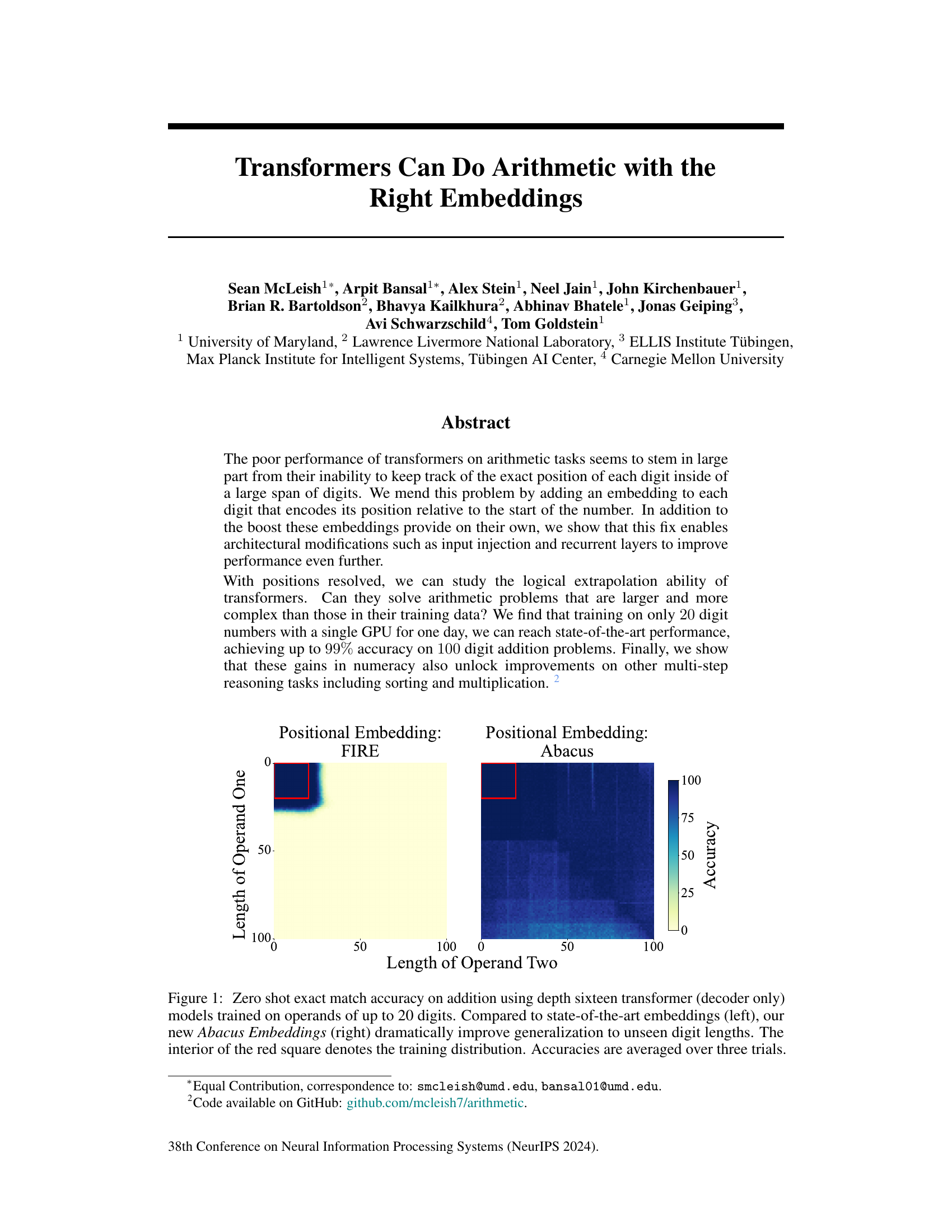

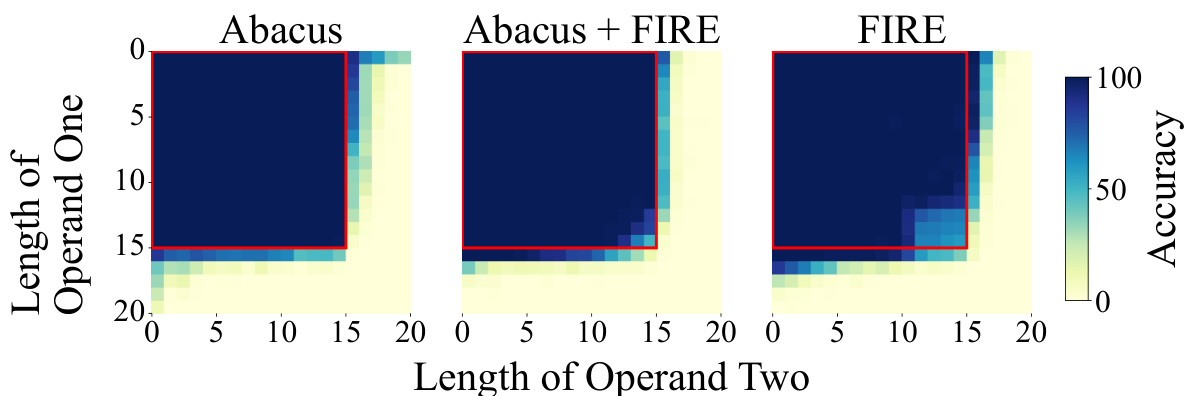

Visual Insights#

This figure compares the zero-shot accuracy of a depth-16 transformer decoder-only model on addition problems using two different types of positional embeddings: FIRE (state-of-the-art) and Abacus (the authors’ new method). The models were trained on numbers with up to 20 digits. The heatmaps show the accuracy for different lengths of operands one and two. The key finding is that Abacus embeddings significantly improve generalization to longer, unseen operand lengths (outside the red square), demonstrating better performance than FIRE embeddings.

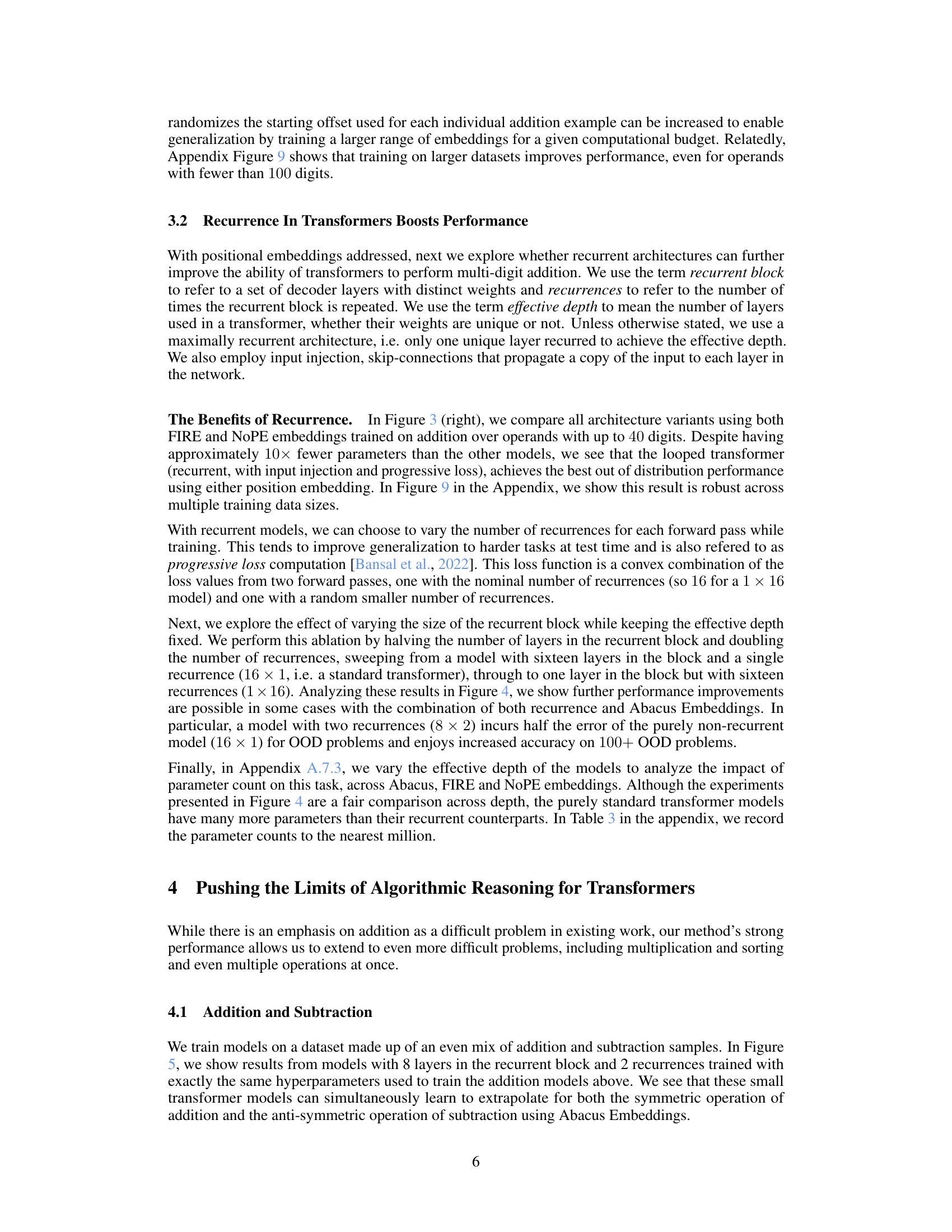

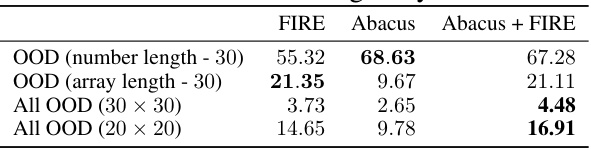

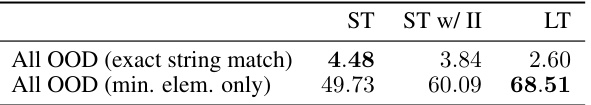

This table presents the exact match accuracy for a sorting task using different positional embeddings (FIRE, Abacus, and a combination of both). The accuracy is measured on out-of-distribution (OOD) data, with variations in the number length and array length. The results highlight the performance of standard transformers with eight layers, demonstrating how different embeddings affect the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data.

In-depth insights#

Arithmetic’s Challenge#

The inherent challenge in teaching arithmetic to transformer models lies in their inability to track the precise positional information of digits within large numbers. Unlike humans who intuitively align digits based on place value, transformers struggle with this spatial encoding, leading to poor performance, particularly when generalizing to longer numbers outside their training distribution. Addressing this positional ambiguity is crucial, and the paper explores various techniques such as incorporating positional embeddings (Abacus Embeddings and others) and architectural modifications (recurrent layers, input injection) to overcome this challenge. The success of these methods highlights the importance of explicitly encoding positional information for effective arithmetic reasoning. The results showcase significant improvement in accuracy and generalization, especially with Abacus Embeddings, enabling transformers to accurately solve addition and multiplication problems far exceeding the length of numbers seen during training. However, further research is needed to fully understand the limitations and generalizability of these techniques to other complex multi-step algorithmic tasks.

Abacus Embeddings#

The proposed Abacus Embeddings offer a novel approach to address the positional encoding challenge in transformer models applied to arithmetic tasks. Unlike traditional methods, Abacus Embeddings encode the significance of each digit based on its place value, rather than its absolute position within the input sequence. This ingenious design mimics the way humans perform arithmetic by aligning digits of the same place value. By assigning the same embedding to all digits representing the same place value, regardless of their position in the number, the model implicitly learns to align digits in different numbers during addition. This significantly improves generalization to numbers with different lengths than seen during training, a major limitation in prior transformer-based approaches. Empirical results demonstrate a dramatic boost in accuracy and extrapolation capabilities, particularly for tasks with very large numbers. The Abacus method elegantly addresses the positional information issue, providing a simpler and more effective solution than existing positional embeddings for arithmetic tasks, making it a valuable contribution to the field.

Recurrence Boosts#

The concept of “Recurrence Boosts” in the context of transformer models for arithmetic tasks suggests that incorporating recurrent mechanisms significantly enhances performance. Recurrent layers, where the same parameters are reused across multiple time steps, allow the model to iteratively refine its computations, effectively simulating a step-by-step process akin to how humans perform arithmetic. This contrasts with standard feedforward transformers, which process the input in a single pass. The improved performance likely stems from recurrence’s ability to maintain context and propagate information across different stages of the calculation, crucial for solving complex, multi-digit problems. The paper highlights the effectiveness of combining recurrence with positional embeddings (Abacus Embeddings), further demonstrating how architectural modifications, when coupled with appropriate data representations, can lead to substantial improvements in solving challenging arithmetic tasks. This suggests that carefully designing the architecture to match the inherent structure of the problem can unlock the true potential of transformers for multi-step reasoning tasks.

Generalization Limits#

The concept of “Generalization Limits” in the context of transformer models for arithmetic tasks is crucial. The inherent challenge lies in extrapolating beyond the training data distribution. While models may achieve high accuracy on numbers within the training range, their performance often degrades sharply when faced with larger or more complex problems. This limitation stems from the models’ inability to truly understand the underlying mathematical principles, instead relying on learned patterns within the limited training dataset. Positional encoding is critical, as the model’s ability to track digit positions significantly impacts its ability to generalize. Methods improving positional encoding, like the Abacus Embeddings, help push the limits, allowing for higher accuracy on longer numbers. However, a fundamental understanding of the underlying mathematics remains elusive, suggesting that true generalization may require a deeper architectural shift, beyond positional encoding enhancements, potentially involving more sophisticated inductive biases or architectural innovations that better capture abstract mathematical reasoning.

Future Extensions#

Future extensions of this research could explore several promising avenues. Expanding the types of arithmetic problems addressed beyond addition and multiplication to encompass more complex operations (e.g., division, exponentiation) and diverse number systems (e.g., fractions, complex numbers) is crucial. The current work demonstrates impressive length generalization, yet investigating the model’s scaling behavior with problem complexity would offer important insights into its fundamental limitations. A deeper theoretical analysis to explain the remarkable performance improvements achieved by Abacus embeddings is highly desirable. Finally, applying the proposed positional embedding techniques and architectural modifications to other algorithmic reasoning tasks, such as sorting, searching, or graph algorithms, would solidify the generalizability of this method and broaden its impact beyond numerical computations. Addressing the potential biases of the dataset and its impact on model generalization is also necessary to enhance the robustness and fairness of the overall approach. Thorough examination of these aspects will refine our understanding of the model’s capabilities and potentially lead to further advancements in transformer-based algorithmic reasoning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

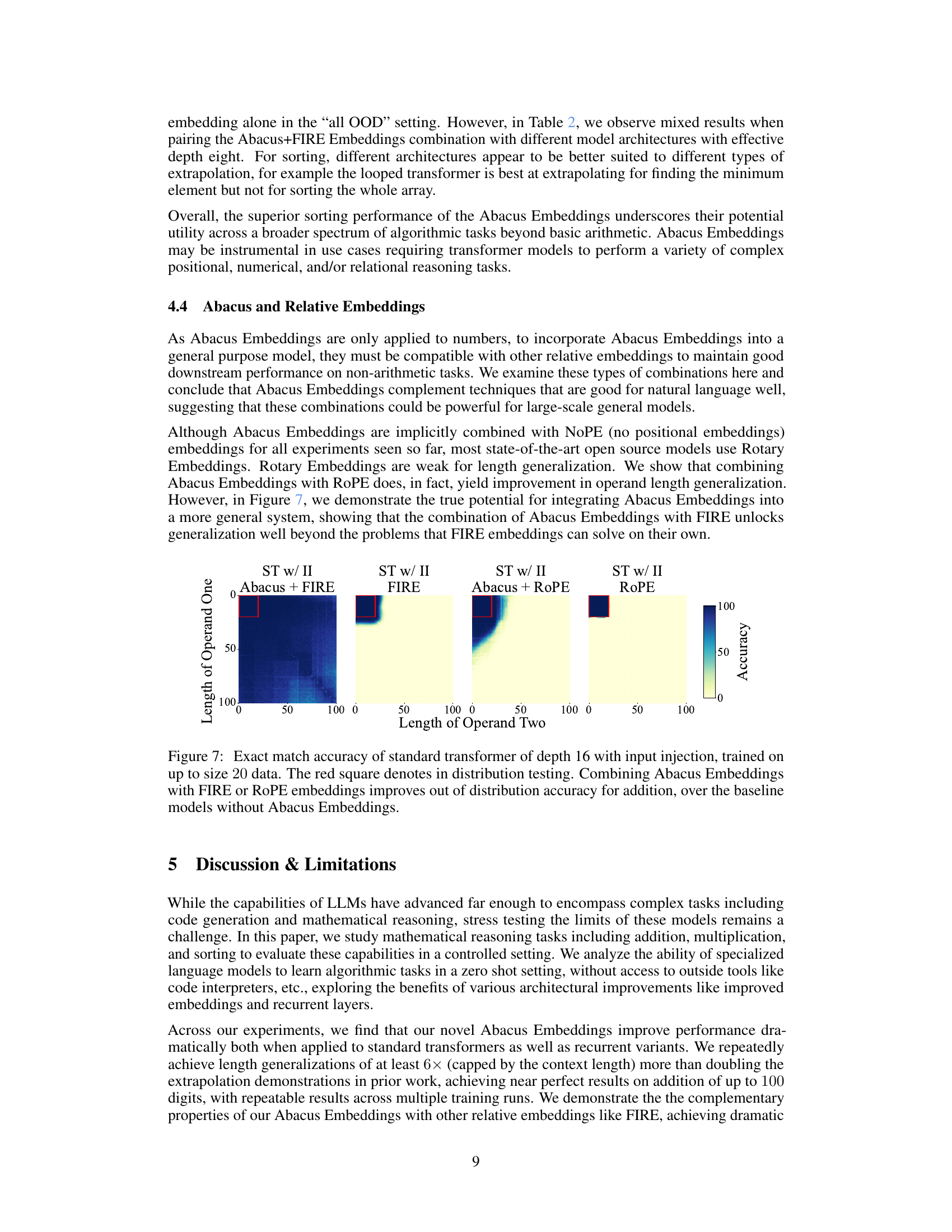

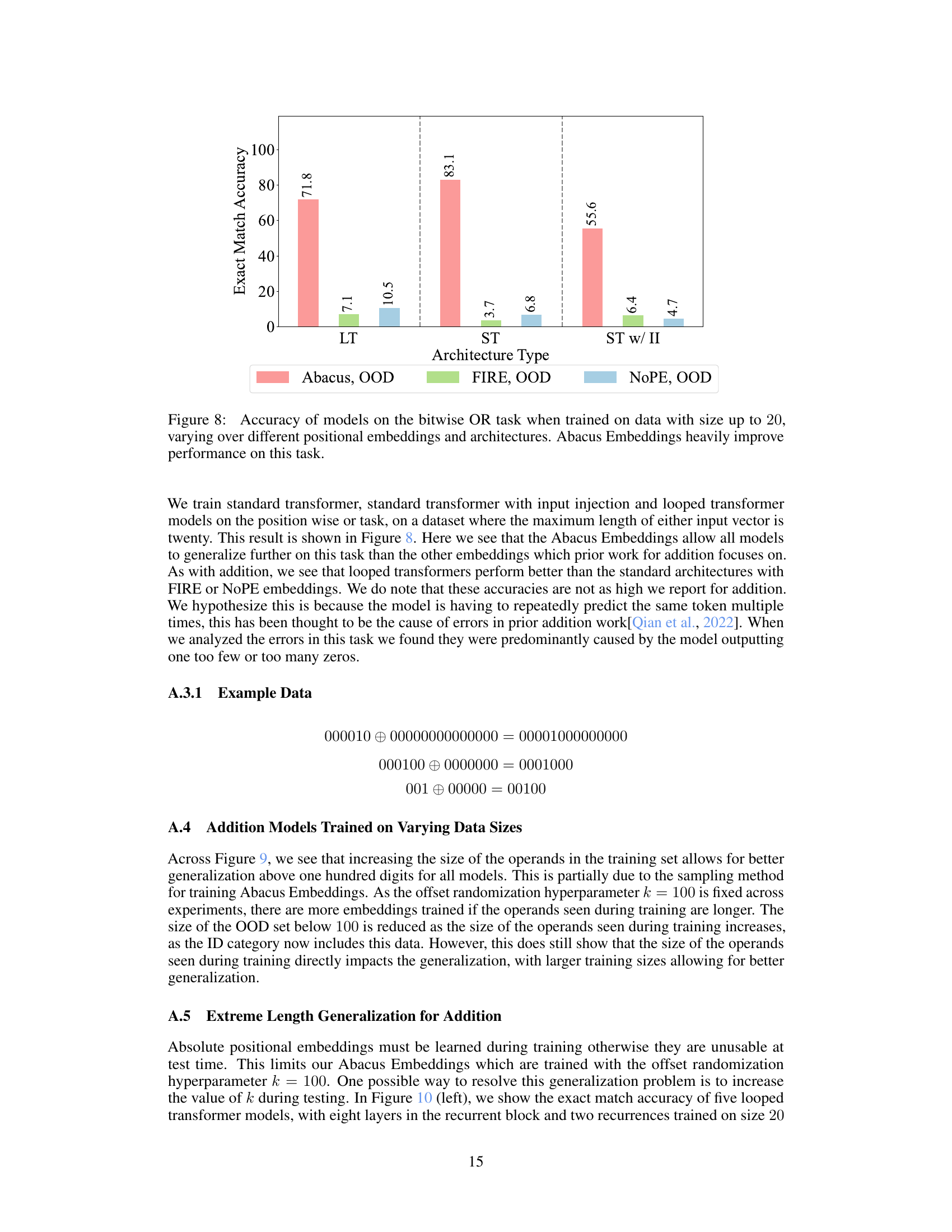

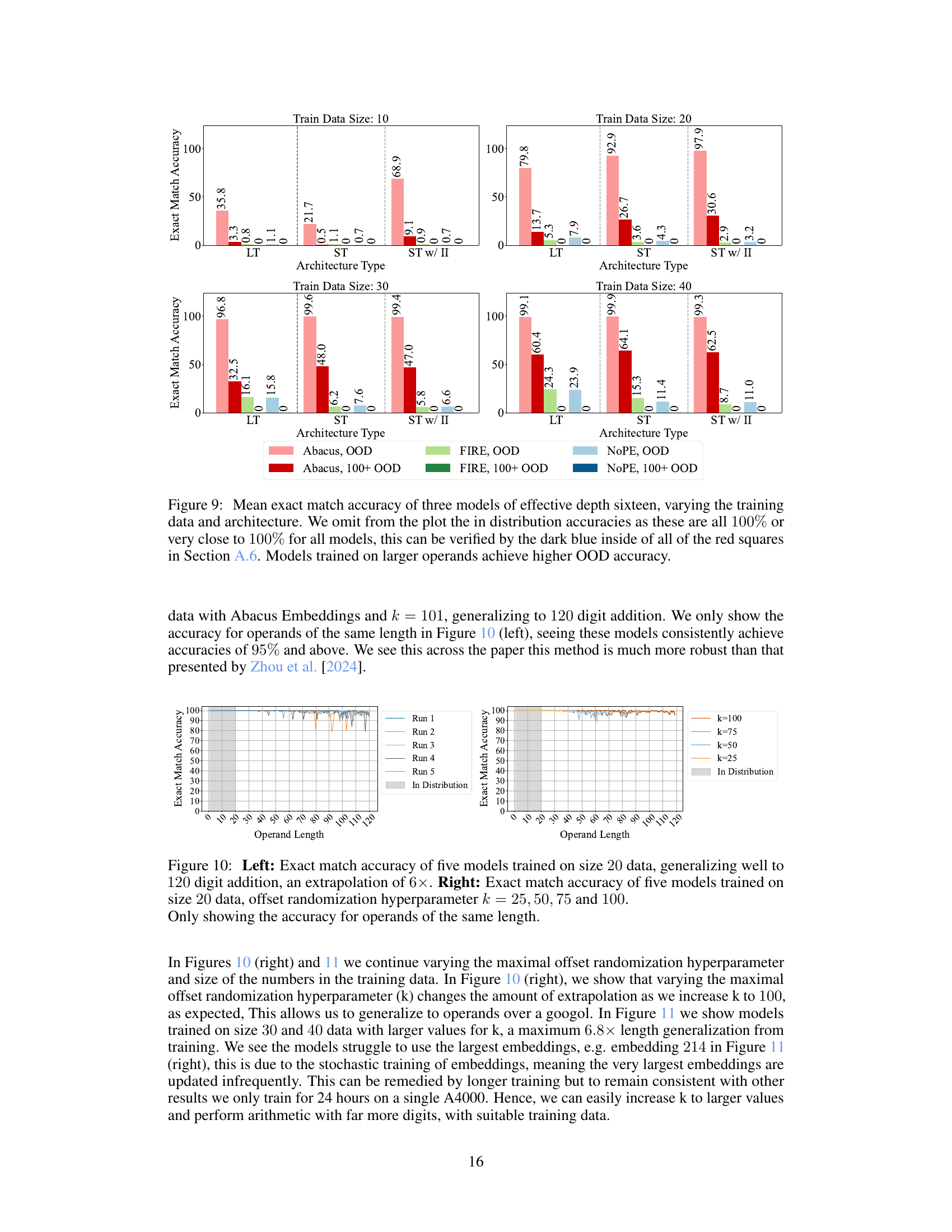

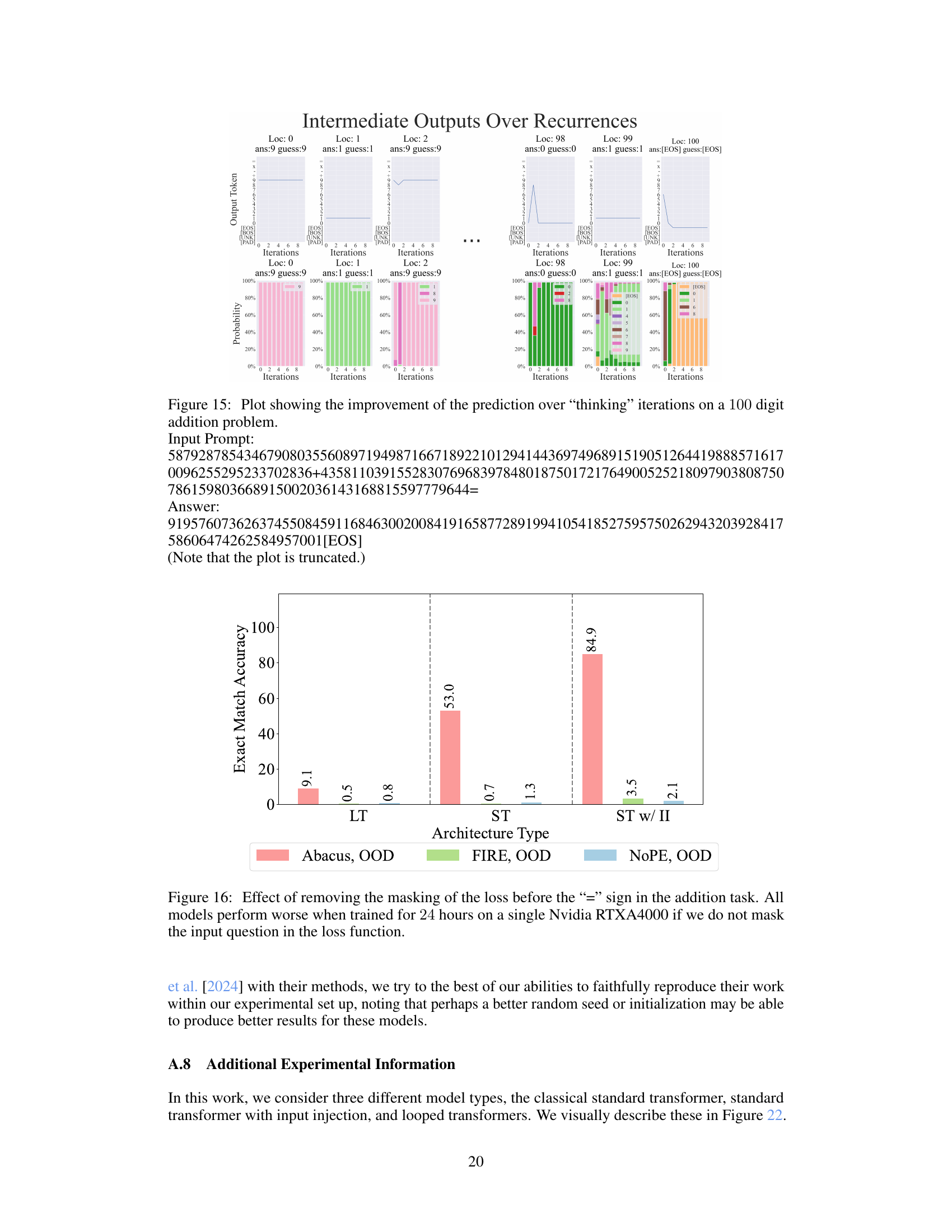

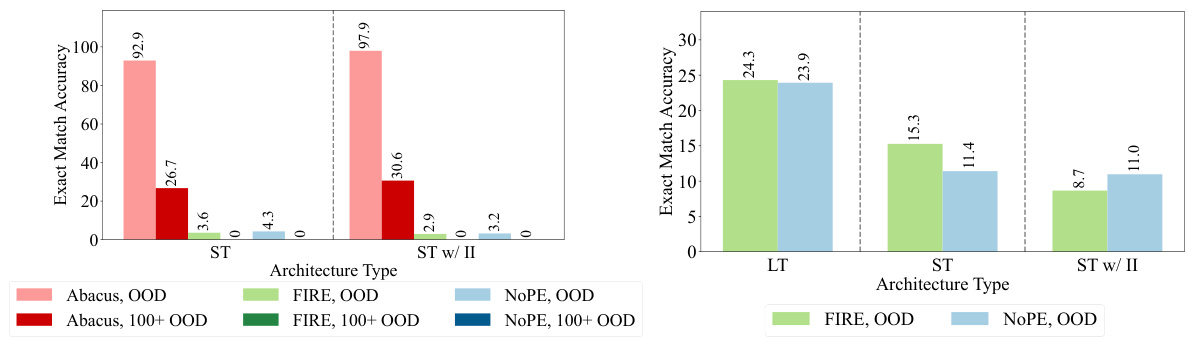

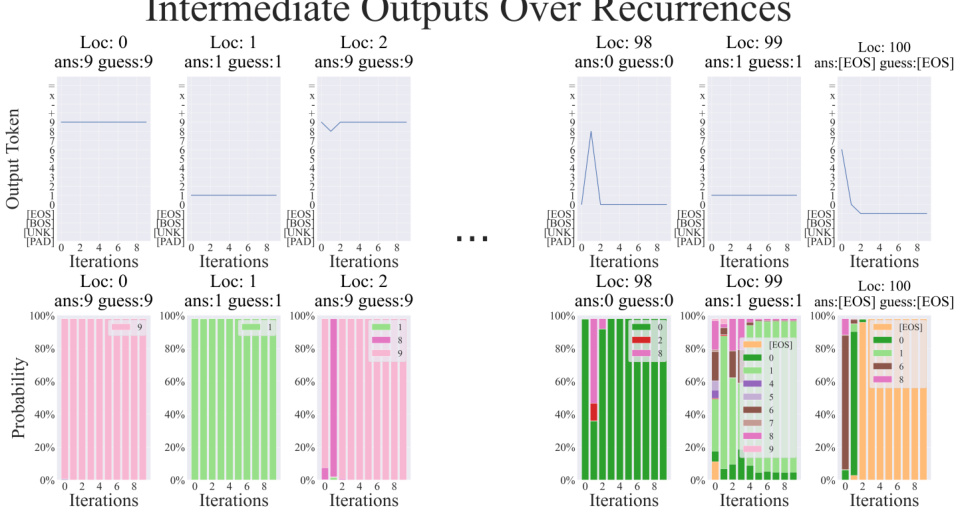

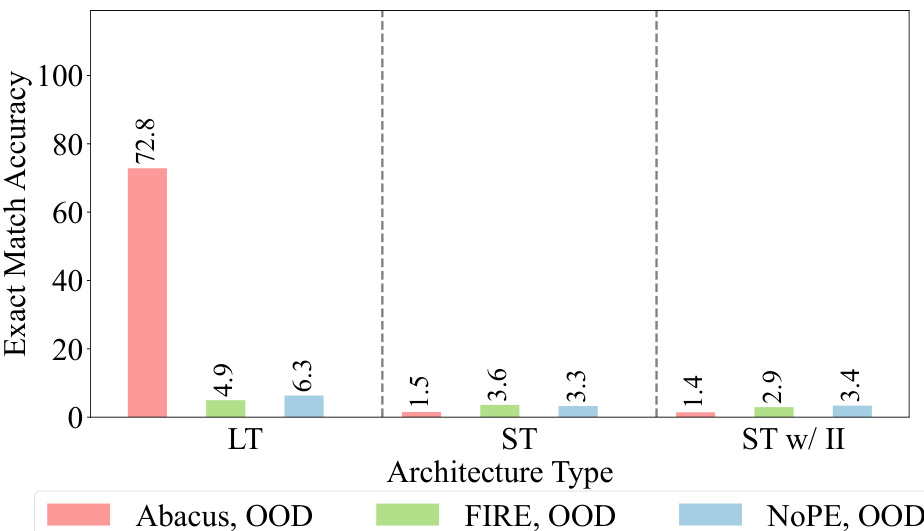

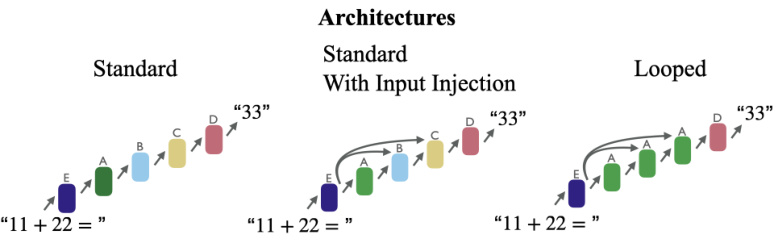

This figure presents a comparison of the performance of different transformer models on addition tasks. The left panel shows the accuracy of three models (standard transformer, standard transformer with input injection, and looped transformer) trained on datasets with 20-digit operands using three types of embeddings (Abacus, FIRE, NOPE). The results show the Abacus embeddings achieve the highest accuracy. The right panel shows similar results for models trained on 40-digit operands. The main finding is that the looped transformer models with the Abacus and FIRE embeddings exhibit significantly higher accuracy compared to the other models.

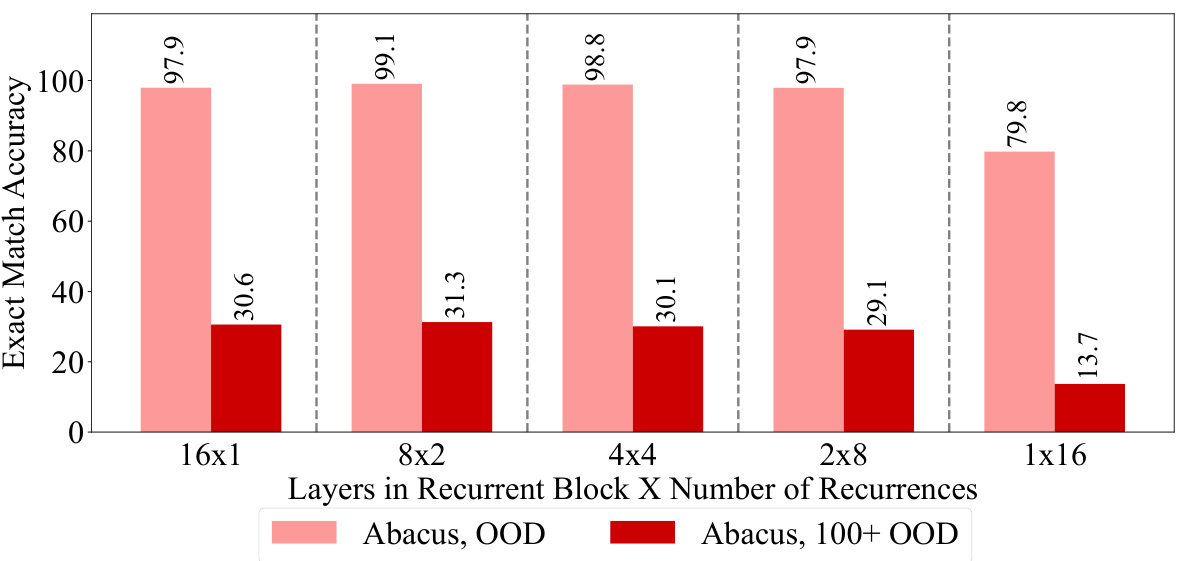

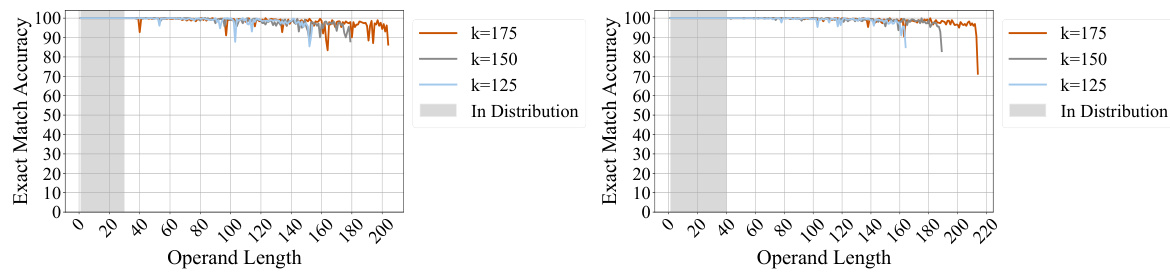

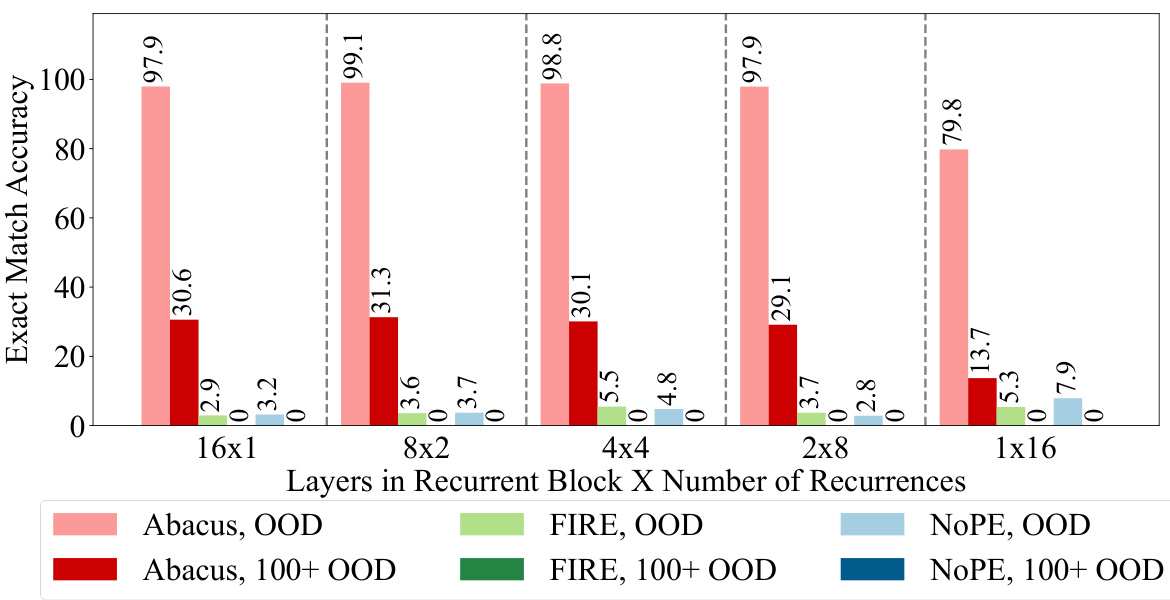

This figure displays the results of an ablation study on the effect of varying the size of the recurrent block in a transformer model on the accuracy of addition problems. The experiment kept the effective depth of the model consistent at 16 layers. The x-axis shows different configurations of layers within the recurrent block and the number of times that block is repeated (recurrences). The y-axis represents the exact match accuracy. Two accuracy metrics are shown: out-of-distribution (OOD) accuracy and extreme out-of-distribution (100+ digit OOD) accuracy. The results demonstrate that a model with 8 layers in the recurrent block and 2 recurrences achieves the best accuracy, significantly outperforming a standard transformer model with input injection.

This figure shows the accuracy of models trained on both addition and subtraction problems with operand lengths up to 20 digits. The models use a recurrent architecture (8 layers in the recurrent block, 2 recurrences). The plot demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize to much larger problems (extrapolation) in both addition and subtraction accurately, even beyond the largest operand lengths seen during training. The shaded gray region indicates the operand length range included in the training dataset.

This figure displays the zero-shot accuracy of a depth-16 transformer model on addition problems. The x and y axes represent the length of the two operands. The color intensity indicates the accuracy, with darker shades showing higher accuracy. The left panel shows results using state-of-the-art FIRE embeddings, while the right panel shows the results obtained with the proposed Abacus Embeddings. The red square indicates the training data distribution. Abacus embeddings show significantly better generalization to longer operands compared to the FIRE embeddings.

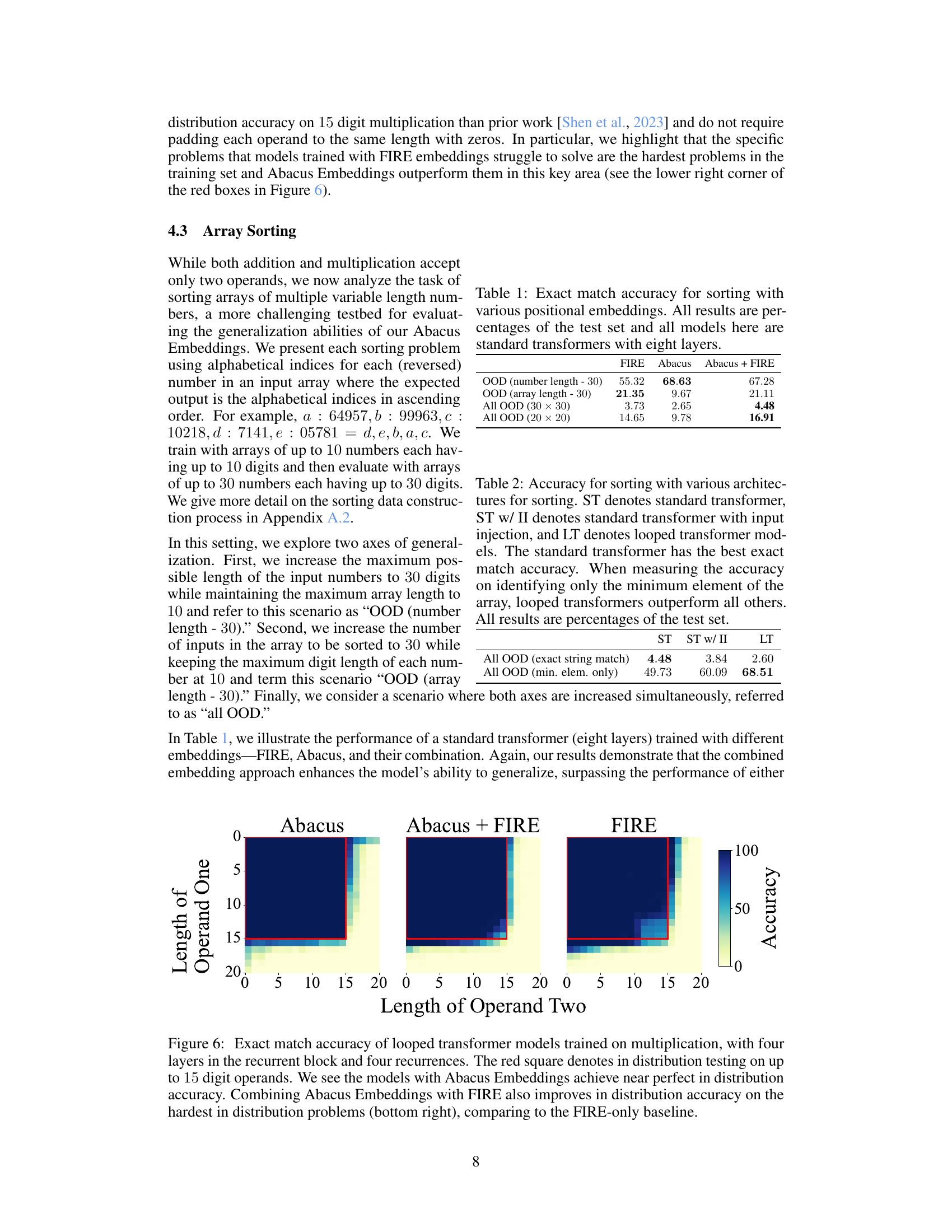

This figure displays the exact match accuracy for addition problems solved by a standard transformer model with a depth of 16 and input injection. The model was trained on datasets with operands up to 20 digits. Four different experimental setups are compared: using Abacus embeddings alone, FIRE embeddings alone, Abacus + FIRE embeddings, and Abacus + RoPE embeddings. The red square shows the in-distribution accuracy (accuracy on problems with operand lengths less than or equal to 20). The figure highlights that combining Abacus embeddings with either FIRE or RoPE improves the model’s accuracy, especially for out-of-distribution problems (operand lengths greater than 20).

This figure displays the mean exact match accuracy for addition problems, comparing the performance of three different transformer architectures (standard, standard with input injection, and looped transformer) across three different positional embedding techniques (Abacus, FIRE, and NoPE). The left panel shows results for models trained on datasets with operands up to 20 digits, while the right panel shows results for models trained on datasets with operands up to 40 digits. The results highlight the improved accuracy achieved by Abacus embeddings and the further accuracy gains obtained using looped transformer architectures, especially when generalizing to unseen operand lengths.

This figure displays the performance comparison of different transformer models on addition tasks. The left panel shows the results for models trained on datasets with operands up to 20 digits, while the right panel shows results for models trained on datasets with operands up to 40 digits. The models varied in their architectures (standard, input injection, and looped transformers) and used different positional embeddings (Abacus, FIRE, and NoPE). The figure highlights the improved performance of the Abacus embeddings and the benefits of using recurrent looped transformer architectures.

This figure displays the zero-shot accuracy of a depth sixteen transformer model on addition problems. The model was trained on operands of up to 20 digits. The left panel shows results using state-of-the-art FIRE embeddings, while the right panel shows results obtained with the novel Abacus embeddings introduced in the paper. The red square highlights the training data distribution. The Abacus embeddings significantly improve generalization to longer operands (beyond the 20 digits seen during training) compared to FIRE embeddings. Accuracy is averaged over three trials.

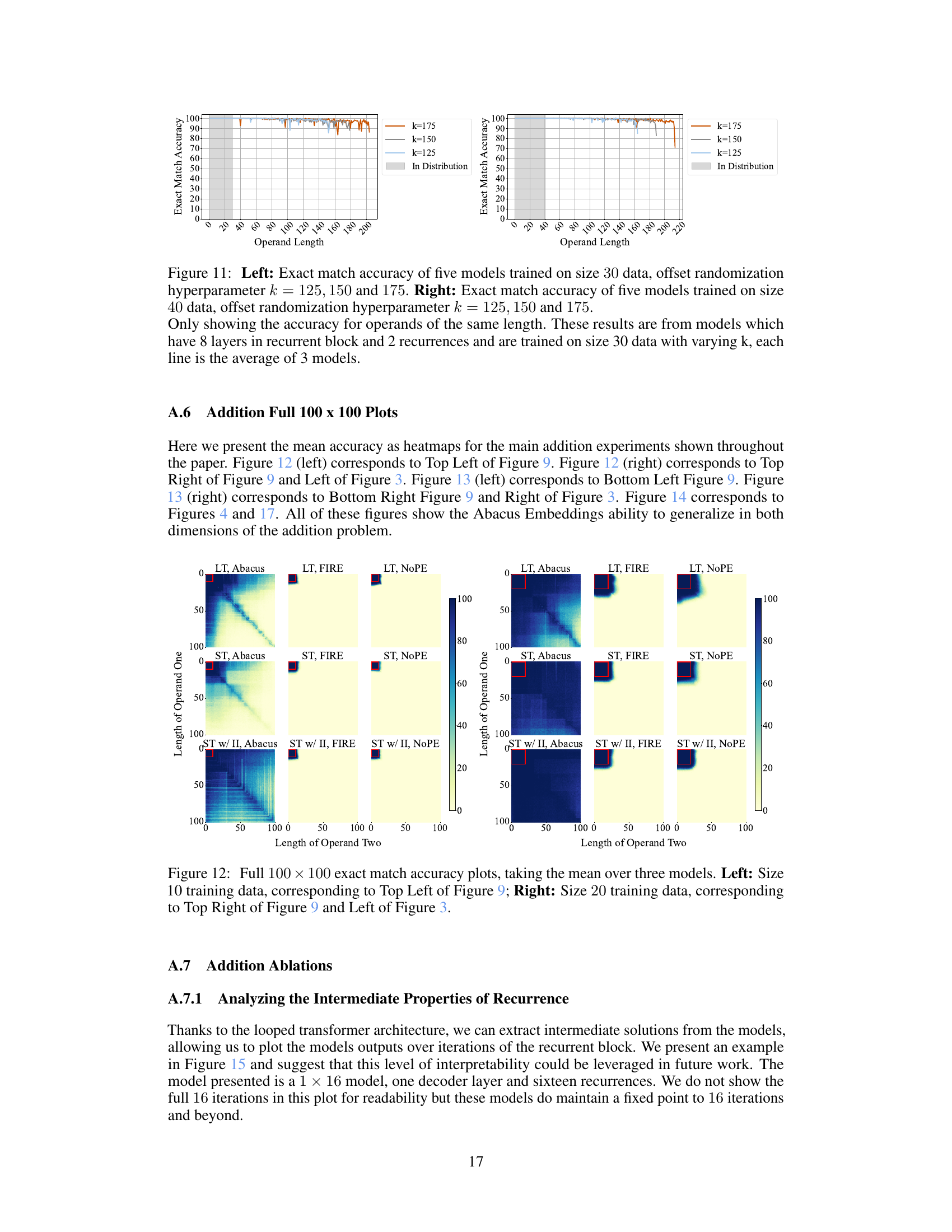

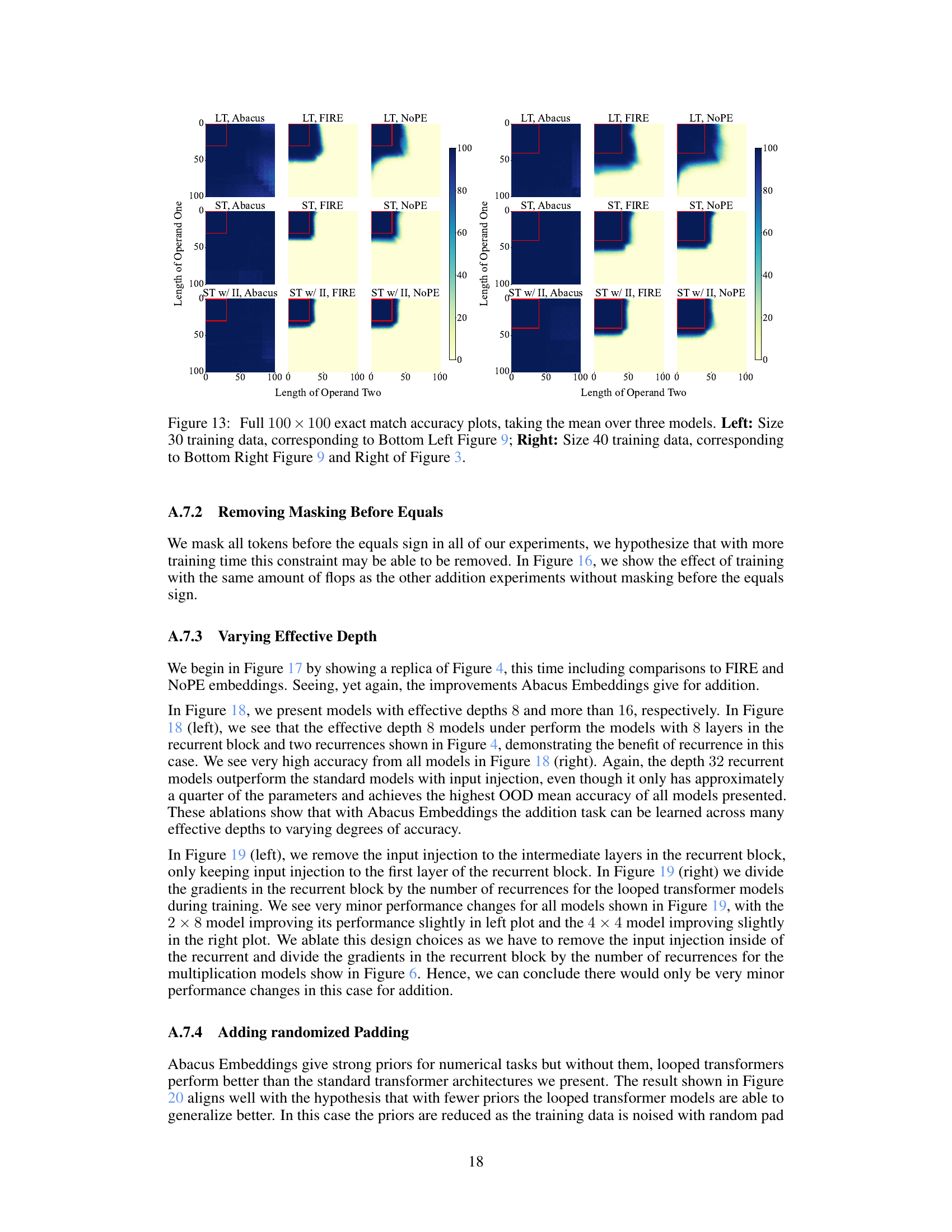

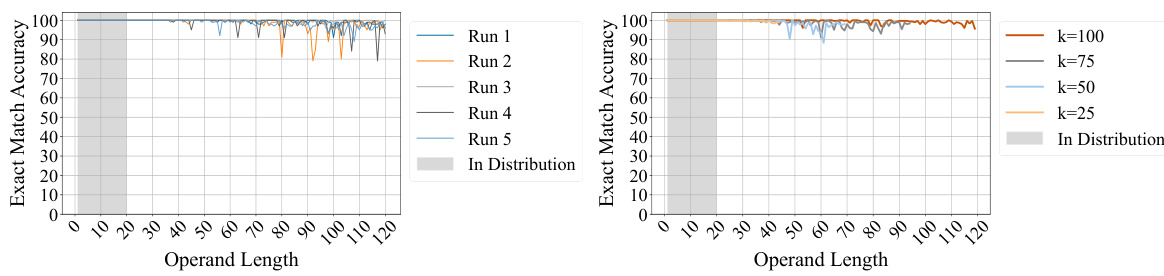

This figure shows the results of experiments evaluating length generalization in addition tasks using Abacus embeddings. The left panel demonstrates that models trained on 20-digit numbers can generalize to 120-digit addition problems with high accuracy, exceeding the previous state-of-the-art generalization factor by a significant margin. The right panel explores the impact of the hyperparameter ‘k’ on generalization. The results suggest that increasing ‘k’ improves the model’s ability to extrapolate to longer addition problems. This hyperparameter controls the range of positional embeddings and its increase allows the models to handle longer sequences beyond the training data.

This figure compares the performance of different transformer models on addition tasks. The left panel shows the accuracy of three depth-16 models trained on datasets with operands up to 20 digits, using different embedding methods (Abacus, FIRE, NOPE). The right panel presents accuracy results for the same models on 40-digit operands, this time using looped transformers and standard transformers. The results highlight the superior performance of the Abacus embeddings and the benefits of recurrent architectures.

The left plot shows the mean accuracy of three different transformer models (standard, standard with input injection, and looped) on addition problems with operands up to 20 digits, each using different embedding techniques (Abacus, FIRE, and NOPE). Abacus embeddings significantly improve performance. The right plot compares the same models but trained on data with operands up to 40 digits. Again, Abacus embeddings are advantageous, and the looped transformer architecture provides notable gains in accuracy, especially when combined with FIRE or NOPE embeddings.

This figure compares the performance of a depth-16 transformer model with two different types of positional embeddings on an addition task. The models were trained on numbers with up to 20 digits. The left side shows the results using FIRE embeddings (a state-of-the-art method), while the right side shows the results using the novel Abacus embeddings. The figure demonstrates that Abacus embeddings significantly improve the model’s ability to generalize to addition problems with longer numbers (beyond the 20 digits seen during training). The red square highlights the training distribution.

This figure shows the zero-shot accuracy of a depth-16 transformer decoder-only model on addition problems. The model was trained on numbers up to 20 digits long. The left side displays results using state-of-the-art FIRE embeddings, while the right shows the improved results using the authors’ new Abacus embeddings. The red square highlights the training data distribution, showing significantly better generalization to longer, unseen digit lengths with Abacus embeddings.

This figure presents a comparison of the performance of different transformer models on addition problems. The left panel shows the accuracy of three models (standard transformer, standard transformer with input injection, and looped transformer) trained on datasets with operands up to 20 digits. The right panel shows accuracy for models with operands up to 40 digits. In both cases, accuracy is shown for different embedding methods (Abacus, FIRE, NoPE). The results demonstrate that Abacus embeddings improve performance in both settings and that recurrent models further improve performance.

This figure displays the results of an ablation study on the effect of varying the size of the recurrent block within a transformer model on the accuracy of addition. The experiment maintains a constant effective depth of 16 and uses a training dataset with operands up to 20 digits. The results show that a model with eight layers in the recurrent block and two recurrences achieves the best out-of-distribution (OOD) accuracy, significantly outperforming a standard transformer with input injection. The improvements are highlighted through a comparison of accuracy scores across different block sizes, demonstrating the optimal balance between block size and recurrence number for enhanced performance.

The figure compares the performance of different transformer models (standard, standard with input injection, and looped transformer) on an addition task, using different positional embeddings (Abacus, FIRE, and NoPE). The left panel shows results for models trained on data with operands up to 20 digits, while the right panel shows results for models trained on data with operands up to 40 digits. The results highlight the superiority of Abacus embeddings and demonstrate that recurrent architectures further improve accuracy.

This figure displays the mean exact match accuracy for addition problems, comparing different models (standard transformer, standard transformer with input injection, and looped transformer) and positional embeddings (Abacus, FIRE, and NOPE). The left panel shows results for models trained on datasets with operands up to 20 digits, while the right panel shows results for models trained on datasets with operands up to 40 digits. The figure highlights that Abacus Embeddings generally improve accuracy, and that recurrent models further boost performance, especially on larger problems (out-of-distribution).

This figure presents a comparison of the performance of different transformer architectures and positional embedding methods on an addition task. The left panel shows the results for models trained on datasets with operands of up to 20 digits, while the right panel shows the results for models trained on datasets with operands of up to 40 digits. The results demonstrate that Abacus embeddings consistently improve accuracy, and that recurrent looped transformer architectures further enhance accuracy, especially for larger operand sizes.

This figure displays the mean exact match accuracy for addition problems, comparing three different transformer architectures (Standard Transformer, Standard Transformer with Input Injection, and Looped Transformer) and three different positional embeddings (Abacus, FIRE, and NOPE). The left panel shows results for models trained on data with operands up to 20 digits, while the right panel shows results for models trained on data with operands up to 40 digits. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of Abacus Embeddings compared to FIRE and NOPE, and the improvement in performance offered by recurrent architectures in both experiments.

This figure compares the performance of different transformer models on an addition task. The models use various positional embeddings (Abacus, FIRE, RoPE), with and without input injection. The results show that combining Abacus embeddings with either FIRE or RoPE embeddings significantly improves the out-of-distribution accuracy compared to using only FIRE or RoPE embeddings.

More on tables

This table presents the accuracy of different transformer architectures on a sorting task. The accuracy is measured in two ways: exact string match (all elements correctly sorted) and minimum element only (only the minimum element is correctly identified). The table compares the performance of standard transformers, standard transformers with input injection, and looped transformers, highlighting that looped transformers excel at identifying the minimum element, while the standard transformer achieves the highest accuracy on exact string matching.

This table shows the number of parameters (in millions) for different looped transformer model configurations. The configurations vary in the number of layers in the recurrent block and the number of recurrences. Abacus Embeddings and input injection are used in all models listed in this table.

This table shows the default number of Nvidia GPU hours used for training and testing different models on various datasets (Addition, Bitwise OR, Sorting, Multiplication). It provides a sense of the computational resources required for each task.

This table lists the default hyperparameter values used in the experiments of the paper. It includes settings for various aspects of the model architecture and training process, such as hidden size, embedding size, optimizer, learning rate schedule, activation function, normalization layer, and the offset randomization hyperparameter (k). These settings are crucial for reproducibility and understanding the experimental setup.

Full paper#