↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

High-dimensional linear bandits are challenging due to the curse of dimensionality. While sparsity is a commonly exploited structure, many real-world problems exhibit hidden symmetry, where rewards remain unchanged under specific transformations. Existing methods often assume explicit knowledge of these symmetries, which limits their applicability.

This paper addresses this gap by focusing on symmetric linear bandits with hidden symmetry. The authors show that simply knowing the existence of symmetry is insufficient to improve regret bounds. They propose a new algorithm, Explore Models then Commit (EMC), that leverages model selection within a carefully constructed collection of low-dimensional subspaces, and demonstrate its effectiveness through rigorous theoretical analysis and empirical evaluations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on high-dimensional linear bandits, particularly those dealing with hidden symmetry structures. It challenges conventional approaches by demonstrating that simply knowing the existence of symmetry is insufficient for improved performance and introduces a novel framework for efficient learning in these complex scenarios. This opens avenues for exploring alternative inductive biases beyond sparsity and developing more effective algorithms for a wide range of real-world problems. The well-defined theoretical analysis and empirical validation provide valuable insights for future research.

Visual Insights#

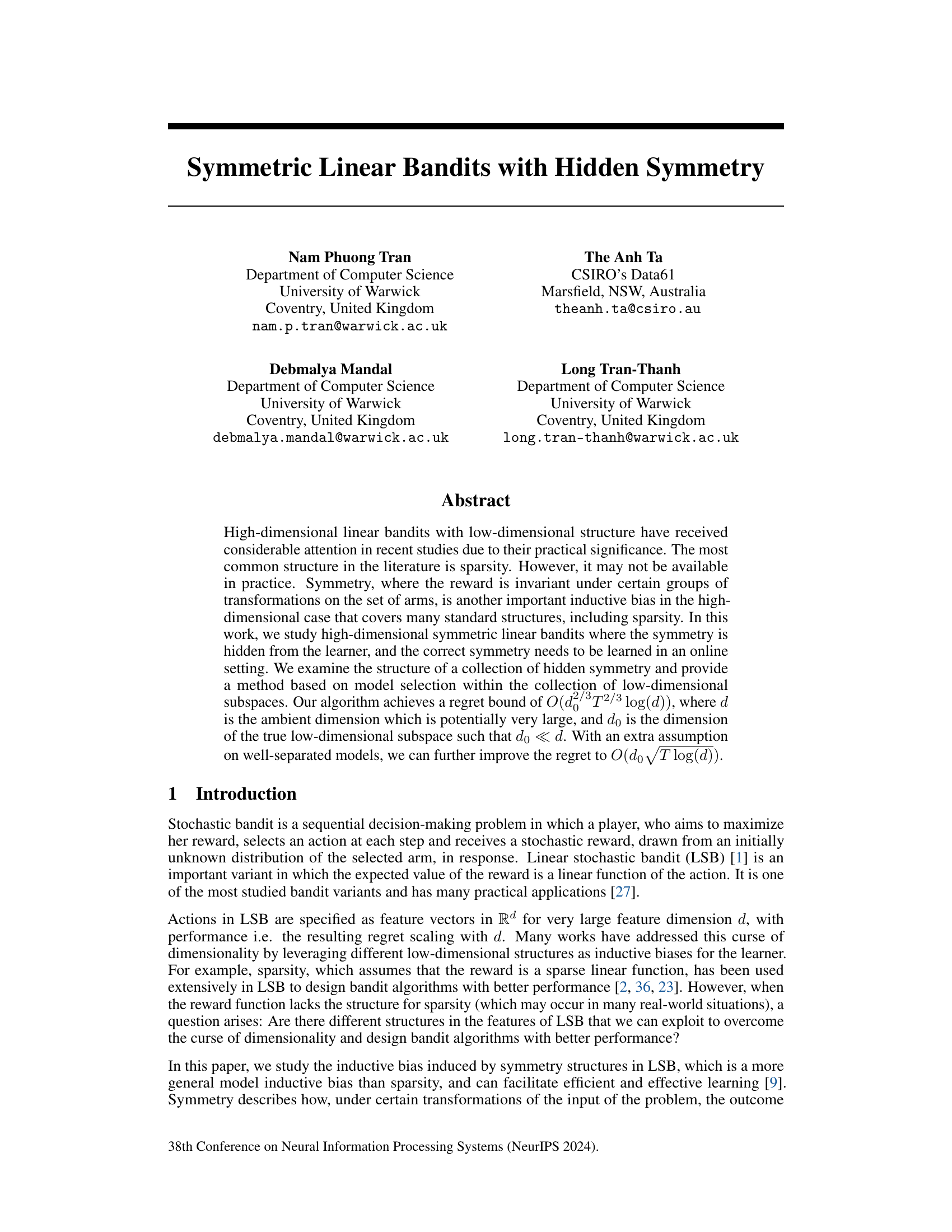

This figure illustrates an example of a partition that respects an underlying ordered tree structure. The nodes in the tree represent subsets of a larger set, and the partition respects the hierarchical relationships within the tree. Children of the same node are grouped together in the same subset of the partition. This example demonstrates that partitions with a hierarchical structure, like those arising from ordered trees, can have subexponentially sized collections, making them a relevant class to study for model selection in the context of the paper’s analysis.

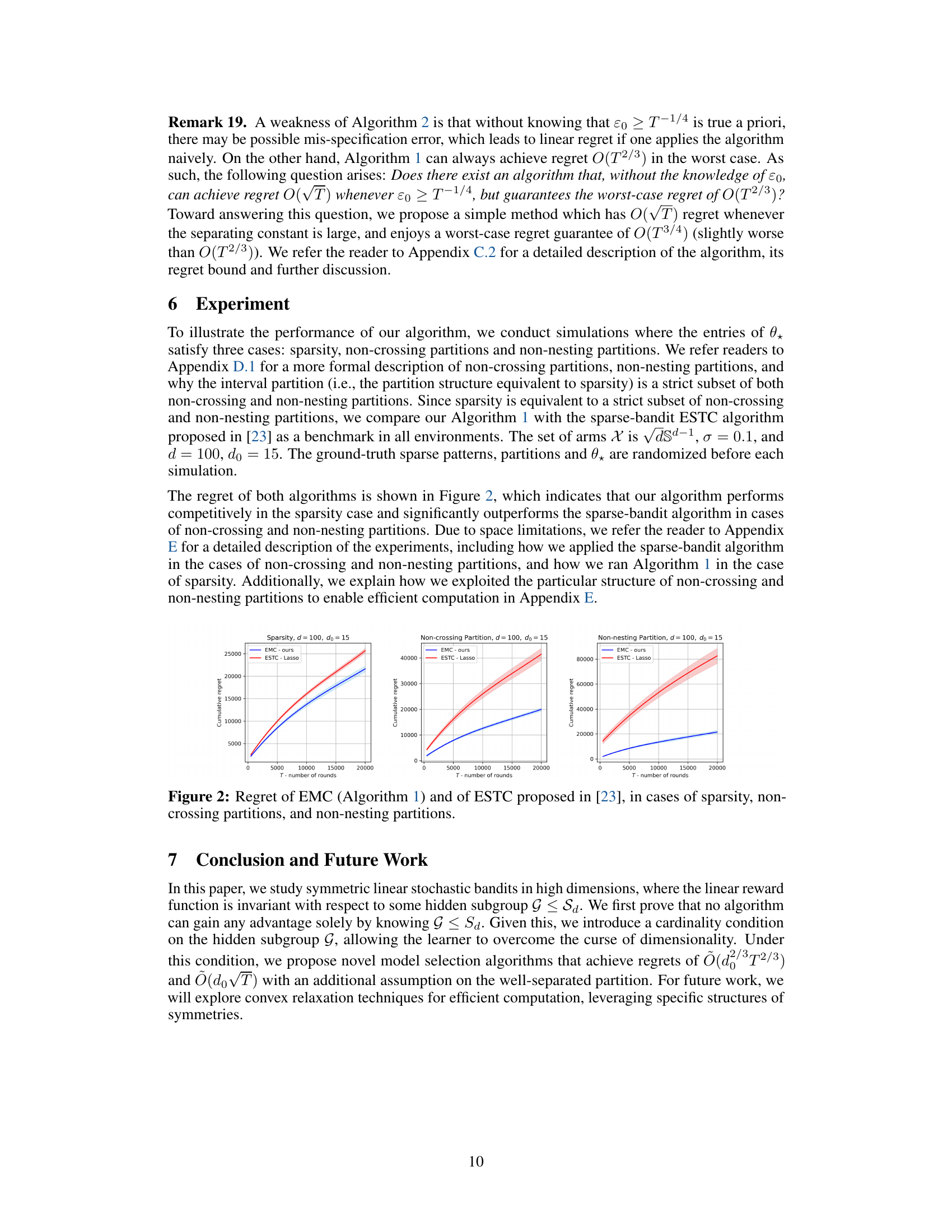

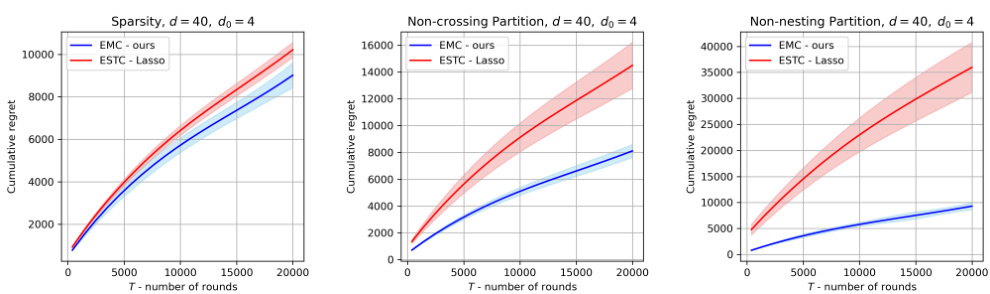

The figure compares the cumulative regret of the proposed Explore Models then Commit (EMC) algorithm against the ESTC algorithm from [23] across three different scenarios: sparsity, non-crossing partitions, and non-nesting partitions. It visually demonstrates the performance of EMC relative to a known sparse bandit algorithm in various symmetric settings.

In-depth insights#

Hidden Symmetry#

The concept of “Hidden Symmetry” in the context of high-dimensional linear bandits presents a significant challenge and opportunity. It suggests that the reward function, while appearing complex in its raw form, possesses underlying symmetries not immediately apparent to the learner. Discovering these hidden structures is crucial because exploiting them can significantly improve the efficiency of learning algorithms. The paper explores methods for identifying and leveraging these symmetries, contrasting the scenario where the symmetries are known a priori versus the more realistic case where they must be discovered online. This introduces significant theoretical and computational complexities, as the space of possible symmetries grows exponentially with the dimensionality of the problem. The approach of learning the symmetry structures online is particularly important as it addresses the limitations of relying on prior knowledge, which often isn’t available in real-world applications. The algorithm’s success hinges on careful model selection from the space of possible symmetries, and efficient exploration techniques play a critical role. The results provide important insights into the effectiveness of incorporating symmetry into bandit algorithm design, offering a promising approach for tackling the curse of dimensionality in complex decision-making problems.

EMC Algorithm#

The Explore Models then Commit (EMC) algorithm is a novel approach to solve the symmetric linear bandit problem with hidden symmetry. Its core innovation lies in framing the problem as a model selection task, cleverly circumventing the limitations of existing methods that struggle with high dimensionality and hidden structure. EMC elegantly leverages a collection of low-dimensional subspaces, each corresponding to a potential hidden symmetry group. The algorithm proceeds in two phases: an exploration phase to gather data and a commitment phase to select the best-performing model. The regret analysis demonstrates a superior regret bound, outperforming standard approaches, particularly when combined with assumptions of well-separated partitions, significantly improving performance in high-dimensional settings.

Regret Analysis#

The Regret Analysis section of a reinforcement learning paper is crucial; it mathematically justifies the algorithm’s performance. It typically starts by defining regret, often cumulative regret, measuring the difference between optimal performance and the algorithm’s actual performance. A key aspect is deriving upper bounds on regret, providing a worst-case guarantee. The analysis often involves complex probabilistic arguments, leveraging tools from concentration inequalities to handle stochasticity. The derived bounds usually depend on key parameters like the time horizon (T), the dimension of the action space (d), and potentially problem-specific properties like sparsity or symmetry. A strong analysis aims to show that the regret scales favorably with these parameters— ideally sublinearly with T. Furthermore, a good regret analysis will discuss lower bounds on regret, demonstrating the theoretical optimality (or near-optimality) of the proposed algorithm. The analysis might also discuss the assumptions made, highlighting their practical implications and limitations. Finally, the analysis section should connect the theoretical results to practical implications, providing insights into algorithm performance and choices of parameters for optimal behavior.

Well-Separated#

The concept of “well-separatedness” in the context of a research paper likely refers to a condition imposed on a set of data points or model parameters. It implies that the elements within the set are sufficiently distinct from each other, preventing undesirable interference or ambiguity. This is crucial for algorithms and analyses that rely on clear distinctions between different groups or classes. In the context of model selection, well-separatedness could mean the models are sufficiently different, minimizing overlap in their performance or predictions, allowing for efficient identification of the optimal model. For partitions, well-separatedness could ensure that the different subsets or clusters defined by the partition are clearly separated in the feature space, reducing the chances of misclassification. The benefit of well-separatedness is often improved algorithm performance and tighter theoretical bounds. By ensuring clear separation, algorithms can better distinguish between different options, leading to increased efficiency and potentially superior results. The exact definition of “well-separatedness” will depend heavily on the specific application. It may involve a distance metric in a feature space, differences in predictive accuracy, or other relevant measures. The existence of a well-separated condition significantly simplifies analyses and may allow for stronger theoretical guarantees in terms of algorithm efficiency and optimality.

Future Work#

The paper’s “Future Work” section suggests several promising avenues. Convex relaxation techniques for efficient computation are a key area, especially given the NP-hard nature of finding optimal subspaces within the explored model space. This is crucial for scaling the approach to higher dimensions and larger datasets. Another important direction is exploring specific structures of symmetries to potentially achieve further improvements in regret bounds. Investigating algorithms that adapt to unknown minimum signal strength (similar to the separating constant ɛ₀) is vital to improve the robustness and practicality of the proposed methods. Finally, extending the framework to encompass broader classes of symmetric bandits or more general structural assumptions beyond those explored in the paper is likely a valuable future endeavor. These extensions could lead to more widely applicable and powerful algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares the cumulative regret of the proposed Explore Models then Commit (EMC) algorithm (Algorithm 1) with the ESTC algorithm from [23] across three different scenarios: sparsity, non-crossing partitions, and non-nesting partitions. The x-axis represents the number of rounds (T), and the y-axis shows the cumulative regret. The shaded areas represent confidence intervals. The results demonstrate that EMC performs competitively with ESTC in the sparsity setting but significantly outperforms ESTC in the non-crossing and non-nesting partition scenarios.

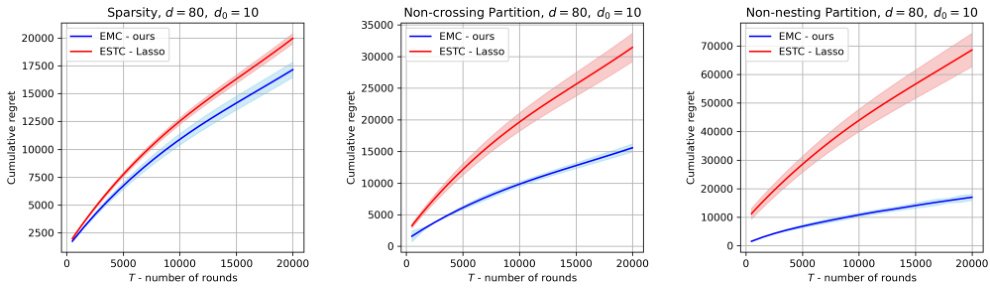

This figure compares the performance of the proposed Explore Models then Commit (EMC) algorithm against the existing ESTC-Lasso algorithm from the literature. The comparison is conducted across three different scenarios: sparsity, non-crossing partitions, and non-nesting partitions. Each scenario represents a different type of structure in the problem, and the figure shows how the cumulative regret of each algorithm varies with the number of rounds (T) in each scenario. The shaded area around each line represents the standard deviation of the results across multiple simulations.

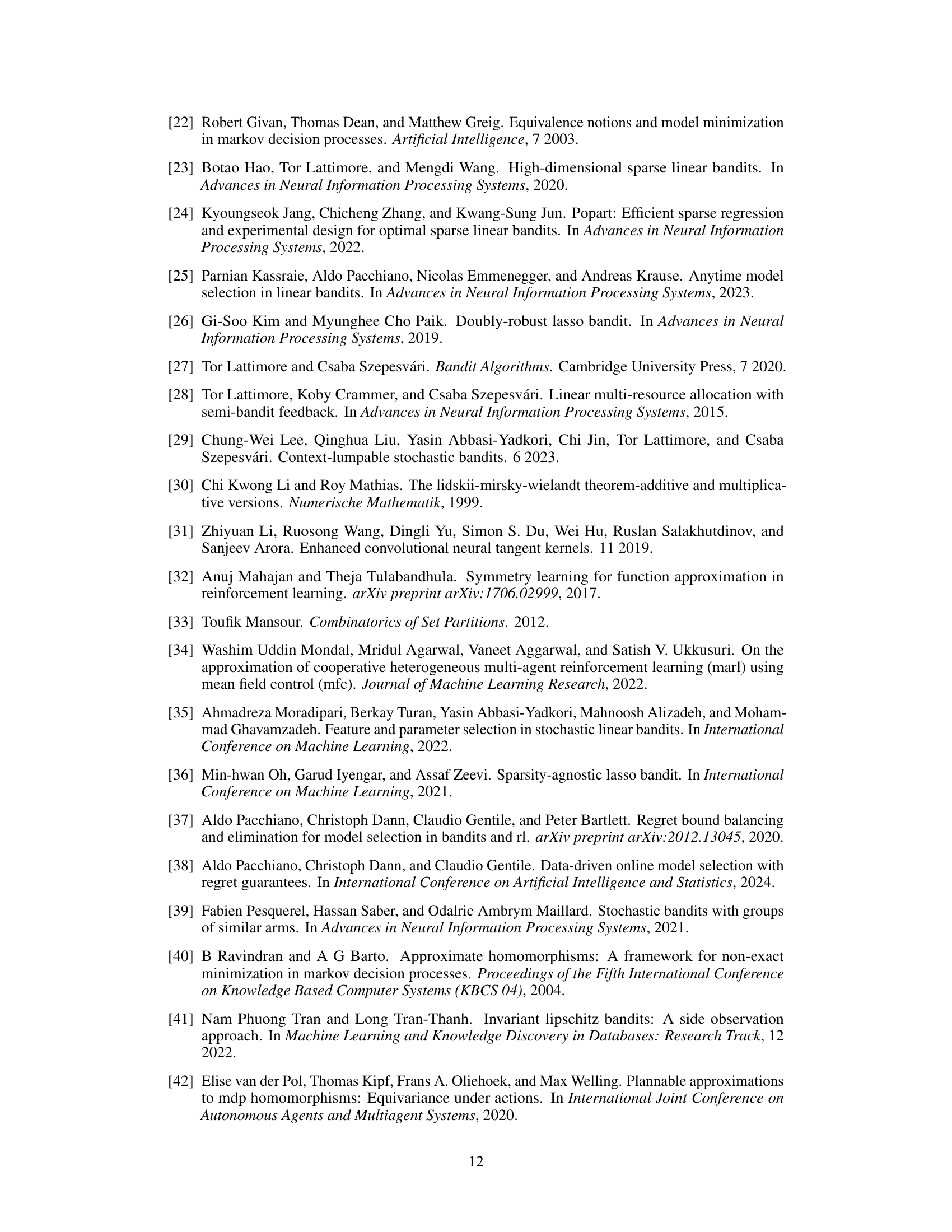

The figure shows the comparison of cumulative regret between the proposed EMC algorithm and the ESTC algorithm from Hao et al. [23] across three different settings: sparsity, non-crossing partitions, and non-nesting partitions. The dimension d is set to 40, and the dimension of the low-dimensional subspace do is set to 4. The x-axis represents the number of rounds (T), and the y-axis represents the cumulative regret. The shaded area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs. The results suggest that EMC performs competitively with ESTC in the sparsity setting but outperforms ESTC significantly in the non-crossing and non-nesting partition settings.

Full paper#