↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Diffusion models, popular in image generation, often produce unrealistic images – a phenomenon called “hallucinations.” These hallucinations stem from the models’ tendency to smoothly connect distinct data clusters, creating outputs that never appeared in the original training data. This is problematic, particularly for the next generation of models that will likely be trained on these generated images, potentially leading to skewed results.

This research provides a systematic analysis of this “mode interpolation” issue. It introduces a new, easily-implementable metric that identifies and removes over 95% of these hallucinations at generation time with minimal impact on realistic outputs. The findings demonstrate how diffusion models sometimes “know” when they’re hallucinating, paving the way for improved model design and more reliable synthetic data generation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it identifies and explains a significant failure mode in diffusion models, a widely used and rapidly developing technology in image generation. Understanding and mitigating these

Visual Insights#

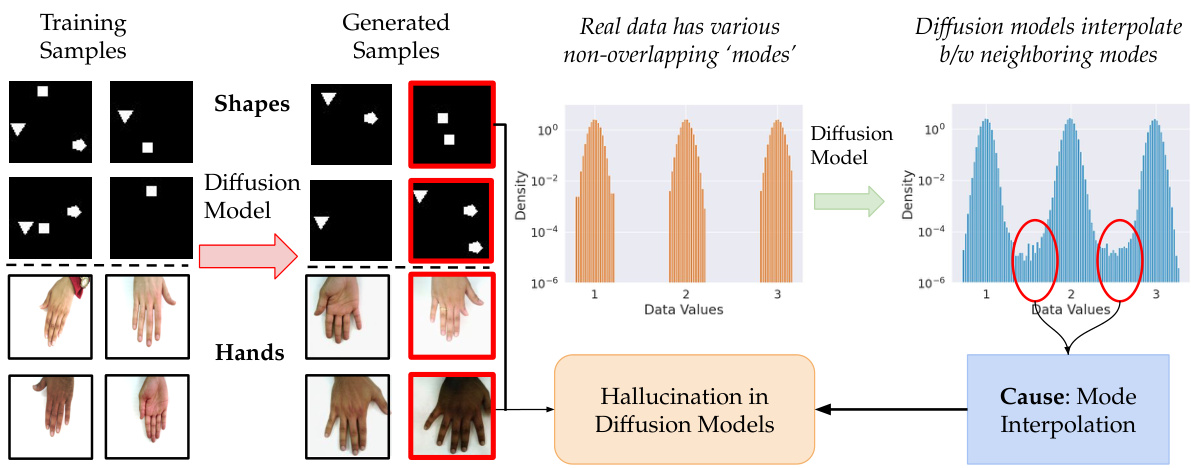

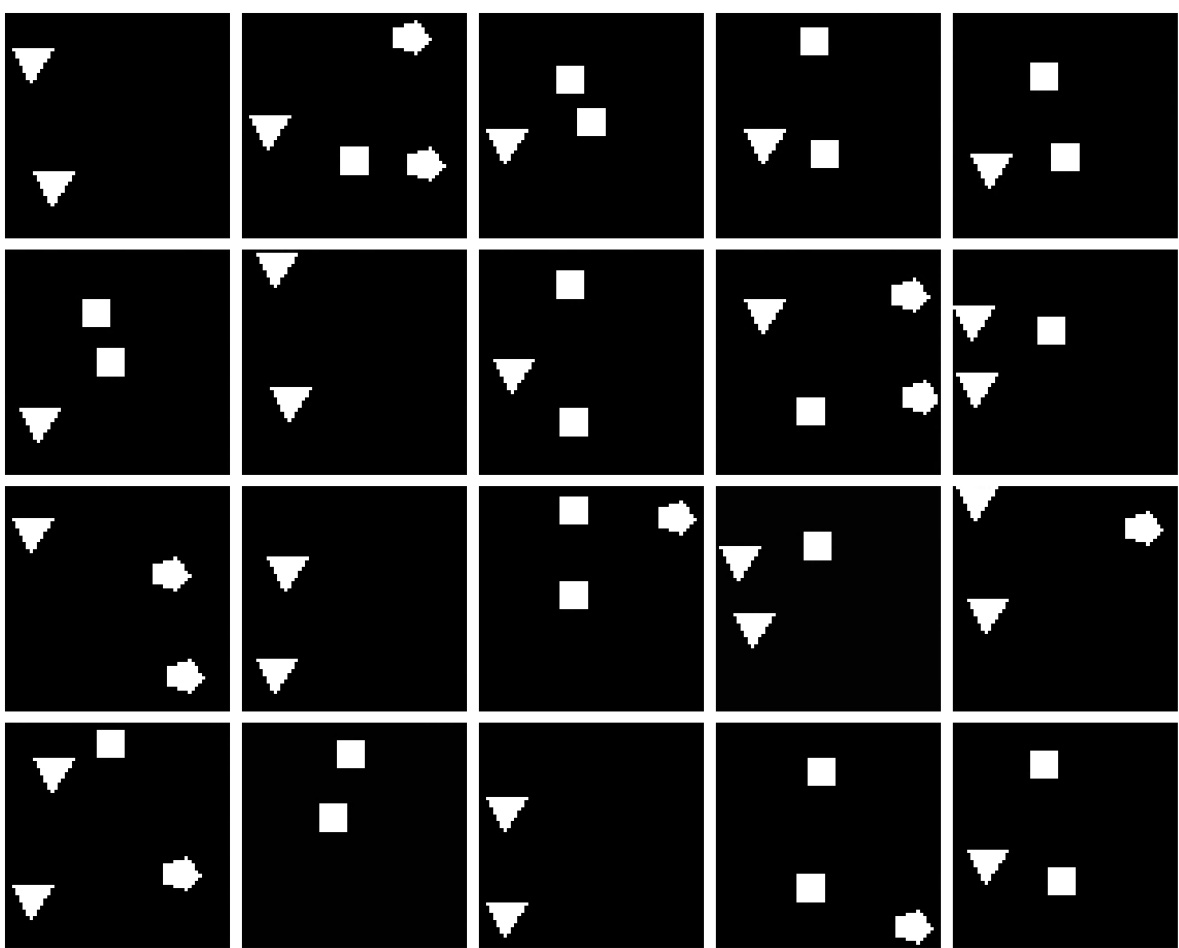

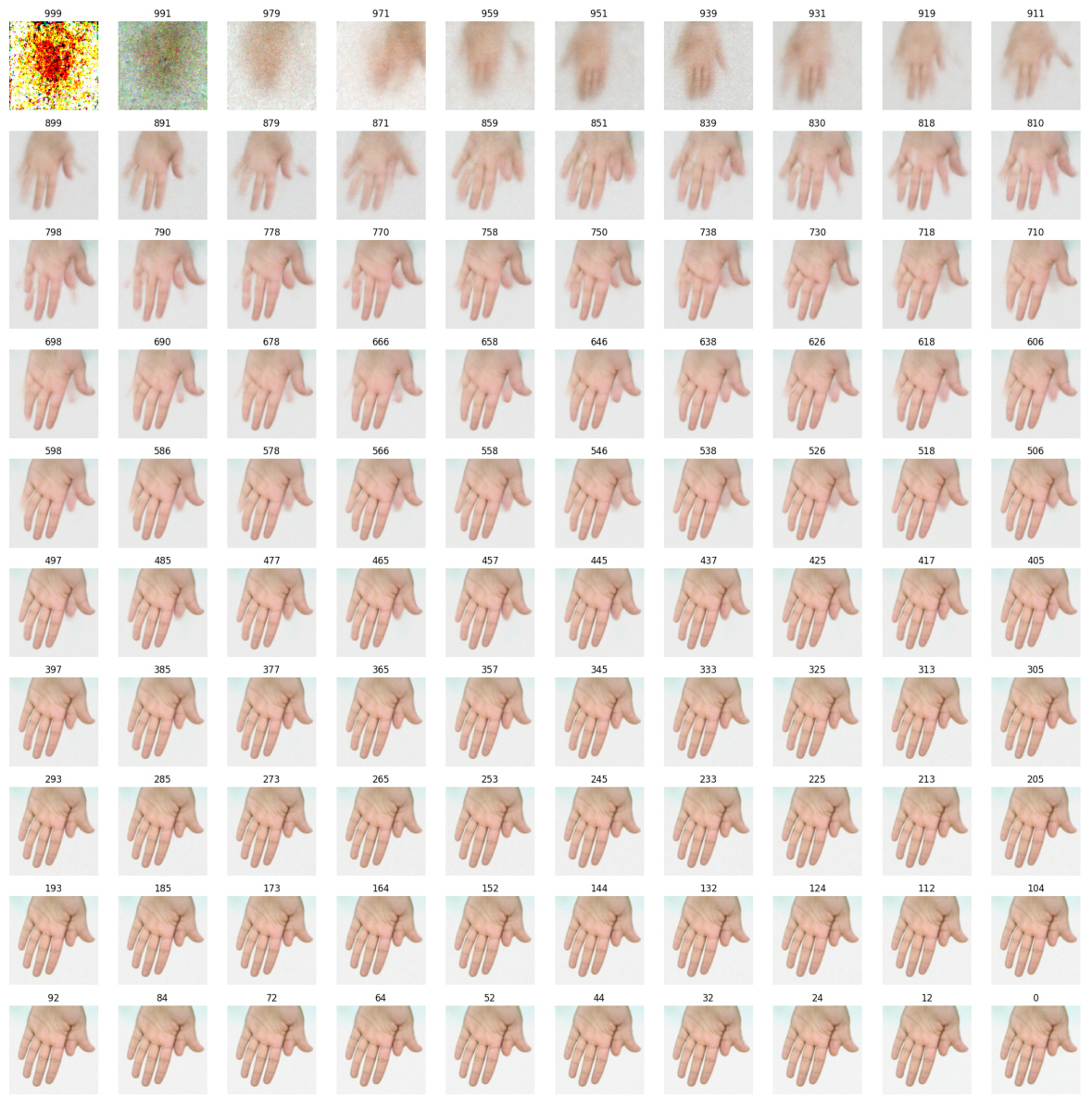

This figure shows the results of training a diffusion model on two datasets: a simple shapes dataset and a hand dataset. The top part shows that the model generates hallucinated images containing combinations of shapes that were not present in the training data. The bottom part demonstrates that the model trained on hand images can produce images with extra or missing fingers. The red boxes highlight examples of hallucinations in both datasets.

In-depth insights#

Diffusion Model Fails#

The heading ‘Diffusion Model Fails’ suggests an exploration of the shortcomings and limitations of diffusion models, a class of generative models known for their high-quality image synthesis. A comprehensive analysis under this heading would likely investigate various failure modes, such as mode collapse, where the model generates limited diversity, focusing on a few dominant modes. Another potential area of focus is mode interpolation, where the model creates outputs by seemingly interpolating between existing data modes, resulting in hallucinations or artifacts unseen in the training data. The analysis should also delve into the impact of the training data distribution, specifically investigating how non-uniform or multimodal distributions can lead to failures. Furthermore, the study might explore the effect of hyperparameters and model architecture on the overall performance and robustness of the model. A key aspect of this investigation would be identifying metrics and techniques for detecting and potentially mitigating these failures, improving the reliability and trustworthiness of diffusion models in real-world applications. This analysis could also consider the broader implications of these failures, particularly in contexts where generative models are used to produce synthetic data for training other models.

Mode Interpolation#

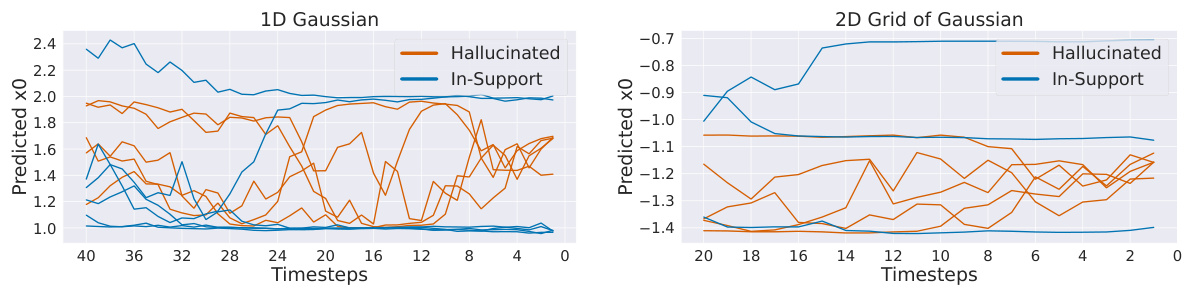

The concept of “Mode Interpolation” in the context of diffusion models highlights a crucial failure mode where models generate outputs that smoothly bridge between distinct data modes, resulting in artifacts unseen in the training data. This interpolation occurs because the learned score function, approximating the true data distribution’s gradient, fails to capture sharp discontinuities between modes. The model effectively creates novel, hallucinated samples, instead of accurately representing the training distribution’s support. This is particularly problematic for multimodal distributions, as it produces outputs falling outside the range of expected values. The paper’s analysis of 1D and 2D Gaussians and real-world datasets such as images of hands demonstrates how this mode interpolation leads to hallucinations like extra fingers. Importantly, the study finds that models often exhibit awareness of these interpolations, showing high variance in sample trajectories nearing the generation’s end. This variance-based metric allows for effective detection of hallucinations.

Hallucination Detection#

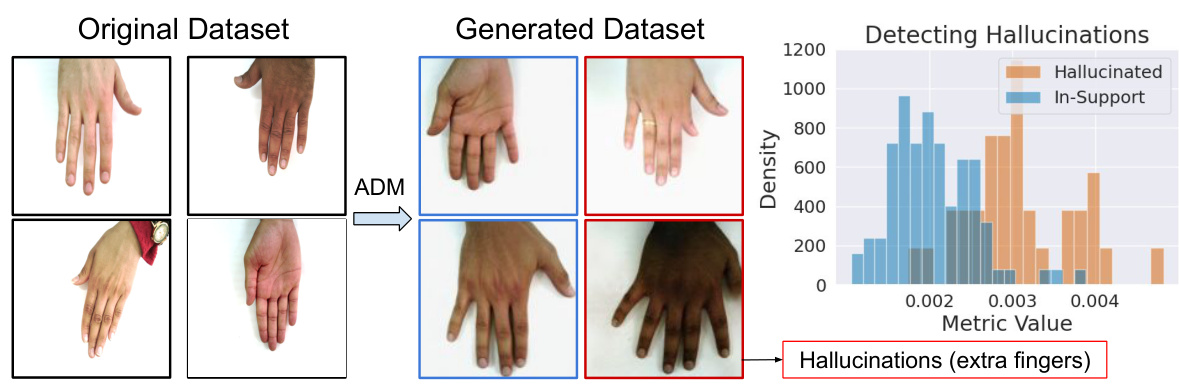

The concept of “hallucination detection” in the context of diffusion models is crucial for improving the reliability and trustworthiness of AI-generated content. The paper explores a novel phenomenon called mode interpolation, where the model generates samples that lie outside the support of the training data by smoothly interpolating between existing data modes. This leads to hallucinations, which are artifacts that never existed in the real data. The authors propose a metric based on the variance of the predicted noise during the reverse diffusion process to identify these hallucinations. This is a clever approach because diffusion models exhibit higher variance in their predictions at the end of sampling when producing hallucinations. High variance in the trajectory serves as a reliable indicator of a sample being generated outside the training data’s support. The effectiveness of this method is demonstrated on both synthetic datasets and a real-world dataset of hand images, showing that it can effectively remove a large proportion of hallucinations while retaining most in-support samples. This approach provides a practical technique for detecting and mitigating hallucinations which is particularly useful for recursive model training, where hallucinations can accelerate model collapse. This work addresses an important and timely problem, offering valuable insights for improving the reliability and trustworthiness of diffusion models.

Recursive Training#

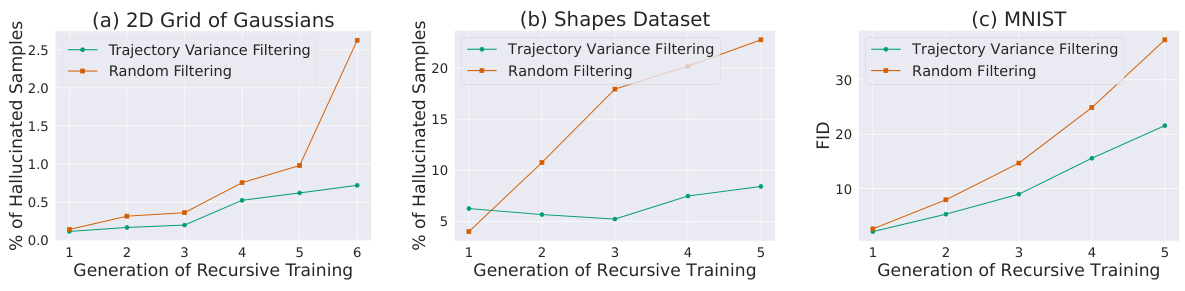

The concept of recursive training, where a model is iteratively trained on its own generated outputs, is explored in the context of diffusion models. This technique, while potentially boosting model performance, presents significant challenges. Mode collapse, where the model’s output becomes limited to a small subset of the data distribution, is a critical concern. The paper investigates how mode interpolation, a phenomenon where the model generates samples that lie between data modes but outside the original data distribution, exacerbates mode collapse during recursive training. This interpolation leads to hallucinations. Careful filtering of these hallucinated samples during each iteration of recursive training is crucial to mitigate model collapse and maintain sample diversity and fidelity. The results highlight the importance of understanding and addressing mode interpolation and its implications for the long-term stability and effectiveness of recursive training methodologies in generative models.

Future Work#

The paper’s exploration of hallucinations in diffusion models opens exciting avenues for future research. A crucial next step is to systematically investigate the relationship between mode interpolation and the architecture of diffusion models, exploring different network designs and training strategies to mitigate this phenomenon. Further research could delve into developing more sophisticated metrics for detecting hallucinations, potentially leveraging advancements in anomaly detection or generative adversarial networks. It’s also important to study the impact of hallucinations on downstream tasks, such as image classification or object detection, quantifying the effect of these artifacts on performance. Finally, exploring the connection between mode interpolation and other failure modes in generative models, such as mode collapse and memorization, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of these limitations. This might involve developing a unified framework capable of characterizing and addressing various types of failures. Investigating potential connections between mode interpolation and dataset biases or imbalances would also be highly beneficial for improving model robustness and reliability. This research should focus on developing robust methodologies to identify, prevent and ultimately remove hallucinations, paving the way for more dependable generative models across various applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

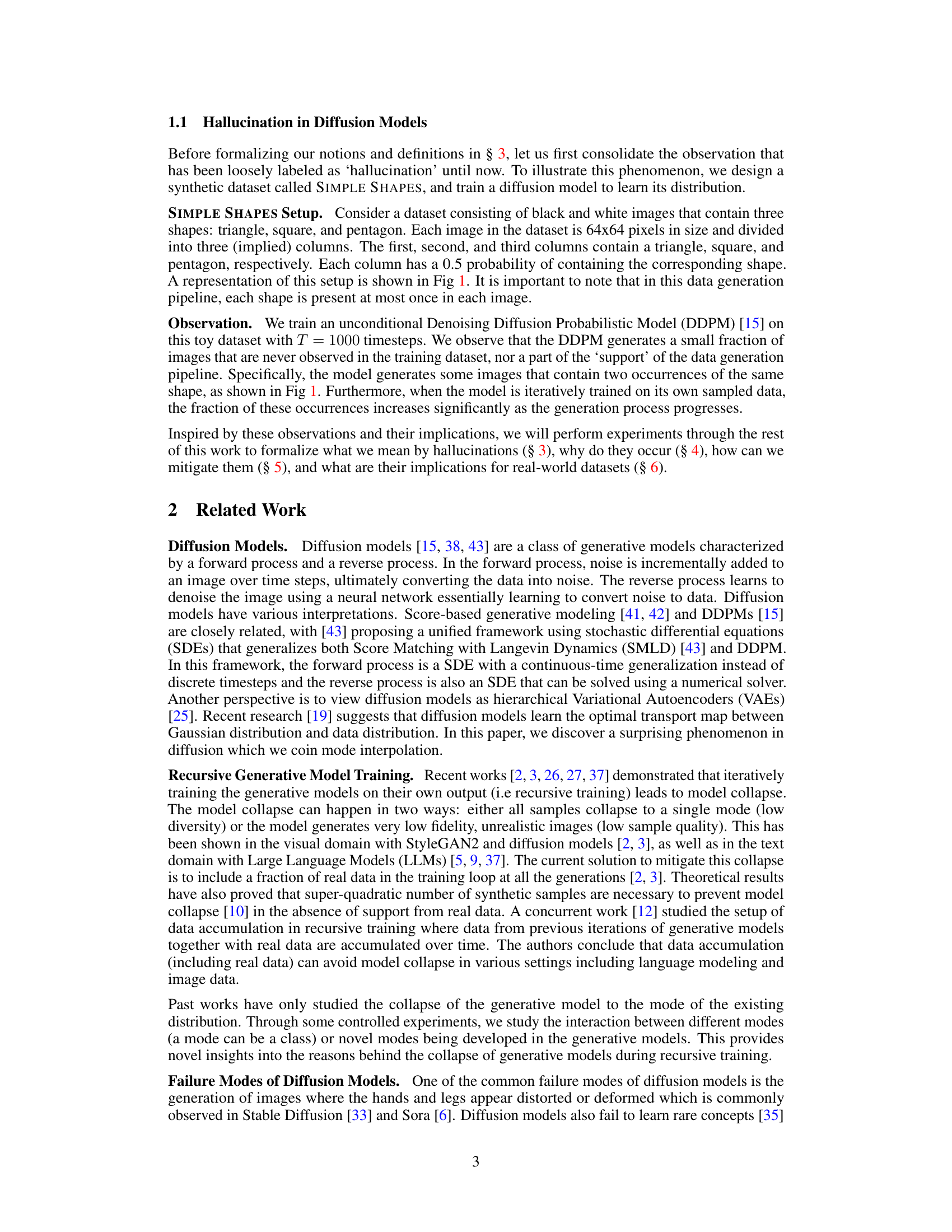

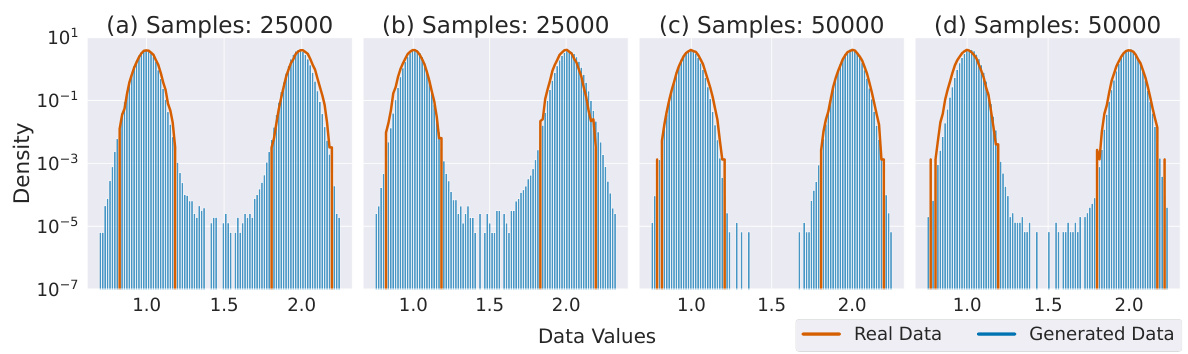

This figure shows the results of training a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) on a 1D Gaussian mixture distribution. It demonstrates the phenomenon of mode interpolation, where the model generates samples in regions between the modes of the true distribution, even though these regions have negligible probability mass. The plots show density histograms of samples generated by the DDPM for varying numbers of training samples and different mode separations. As expected, increased training samples reduce the number of samples in the interpolated regions. Similarly, moving modes further apart also decreases the number of interpolated samples.

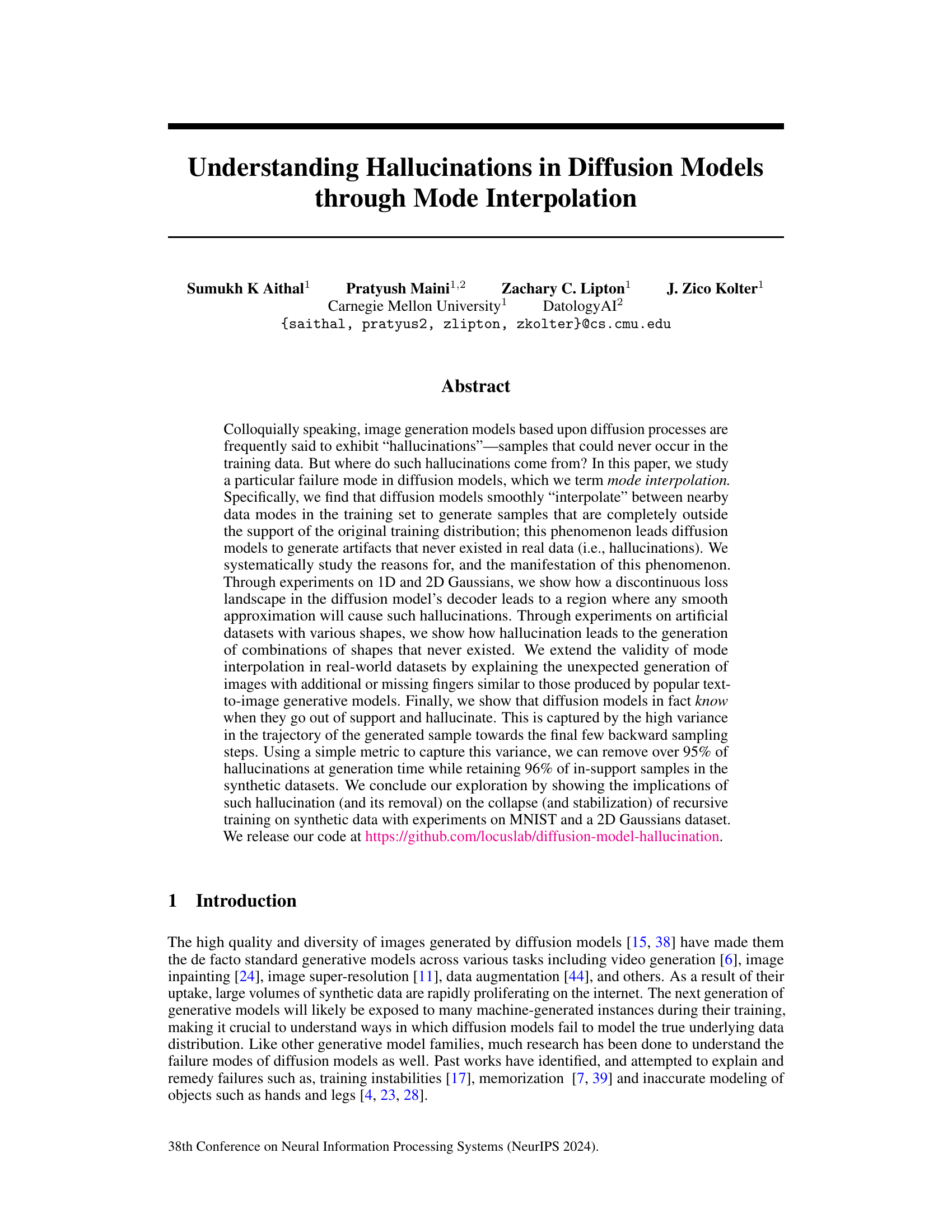

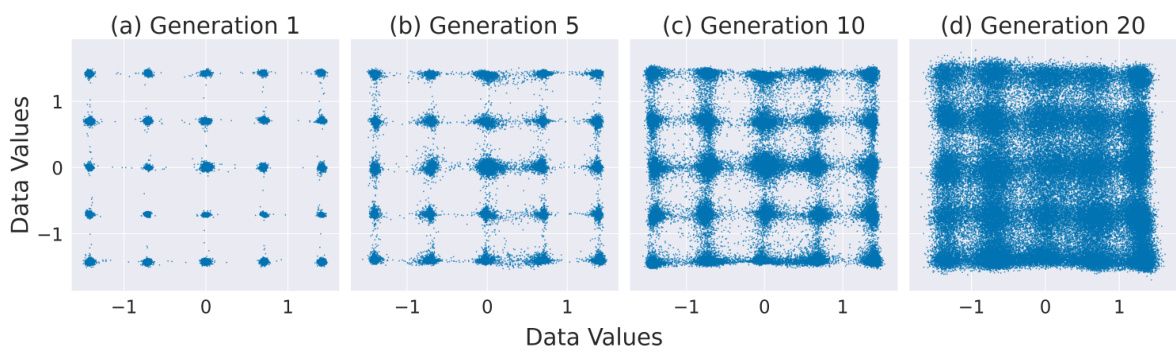

This figure shows the mode interpolation phenomenon in a 2D Gaussian mixture dataset. Subfigures (a) and (b) demonstrate interpolation between nearby Gaussian modes in a square grid arrangement, where the model generates samples in regions with near-zero probability in the original data distribution. (c) and (d) show that this interpolation is localized and does not occur when the modes are rearranged into a diamond shape, indicating that the interpolation is between nearest neighbors.

This figure compares the ground truth score function and the learned score function of a diffusion model trained on a mixture of Gaussians. The ground truth score function has sharp jumps between different modes, while the learned score function is smoother. This difference explains why the diffusion model interpolates between modes, generating samples outside the support of the training distribution (hallucinations). The rightmost panel shows the trajectory of the predicted x0 (final sample) for different timesteps during the reverse diffusion process, highlighting the high variance for hallucinated samples.

This figure shows a comparison of training samples and generated samples from diffusion models. The top part demonstrates mode interpolation on a simple shapes dataset: the model generates samples with combinations of shapes never seen in the training data. The bottom part shows that the model trained on images of hands can hallucinate hands with extra fingers. This illustrates the phenomenon of mode interpolation, a central point of the paper.

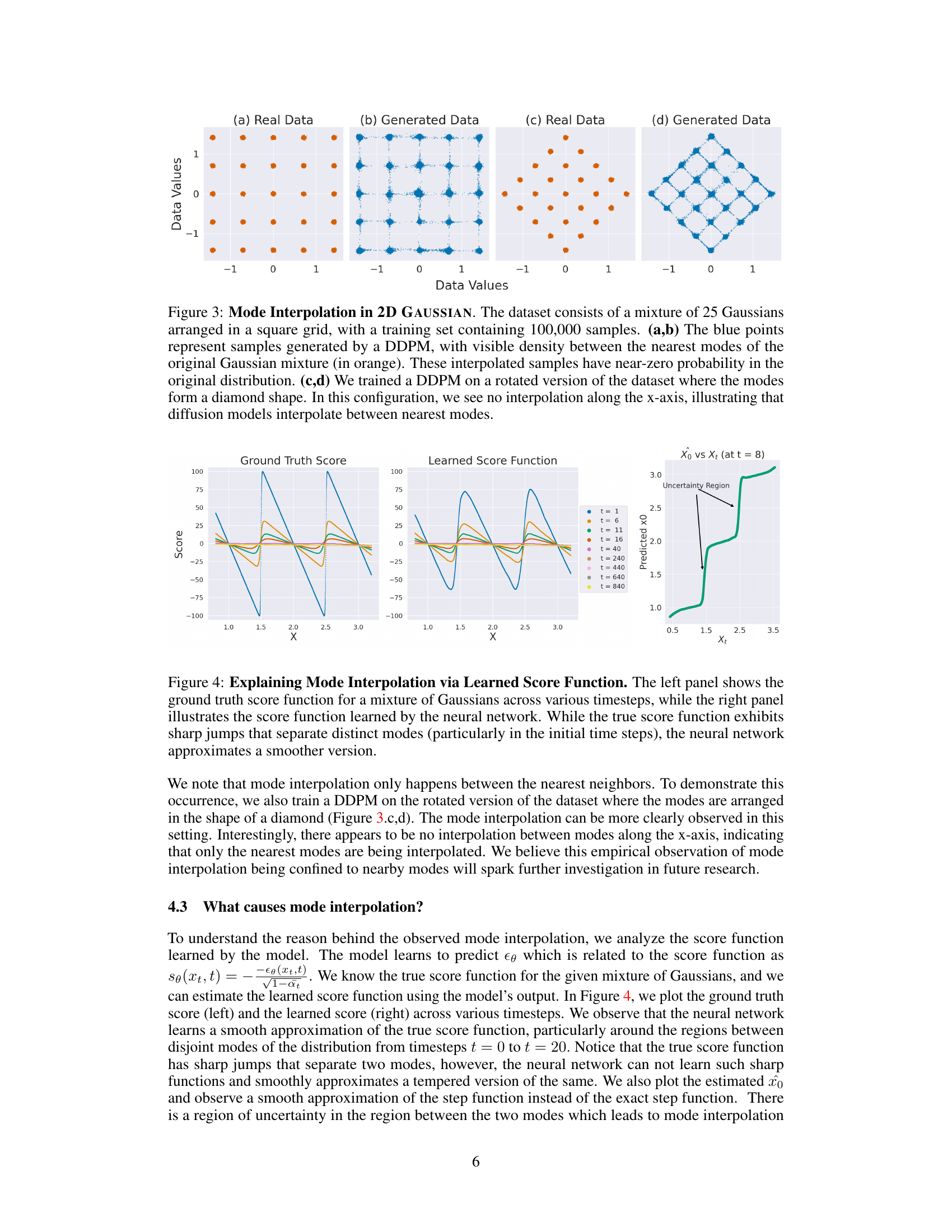

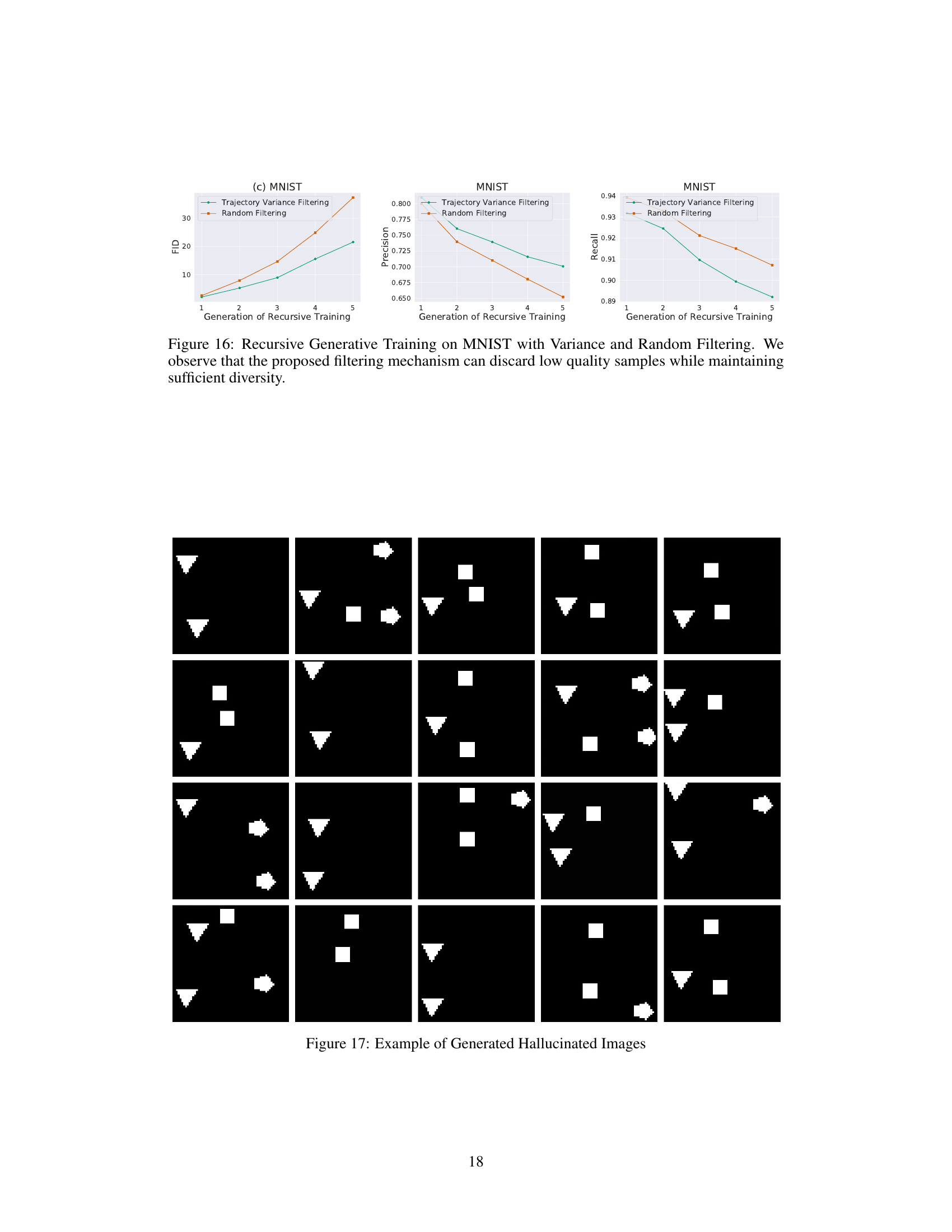

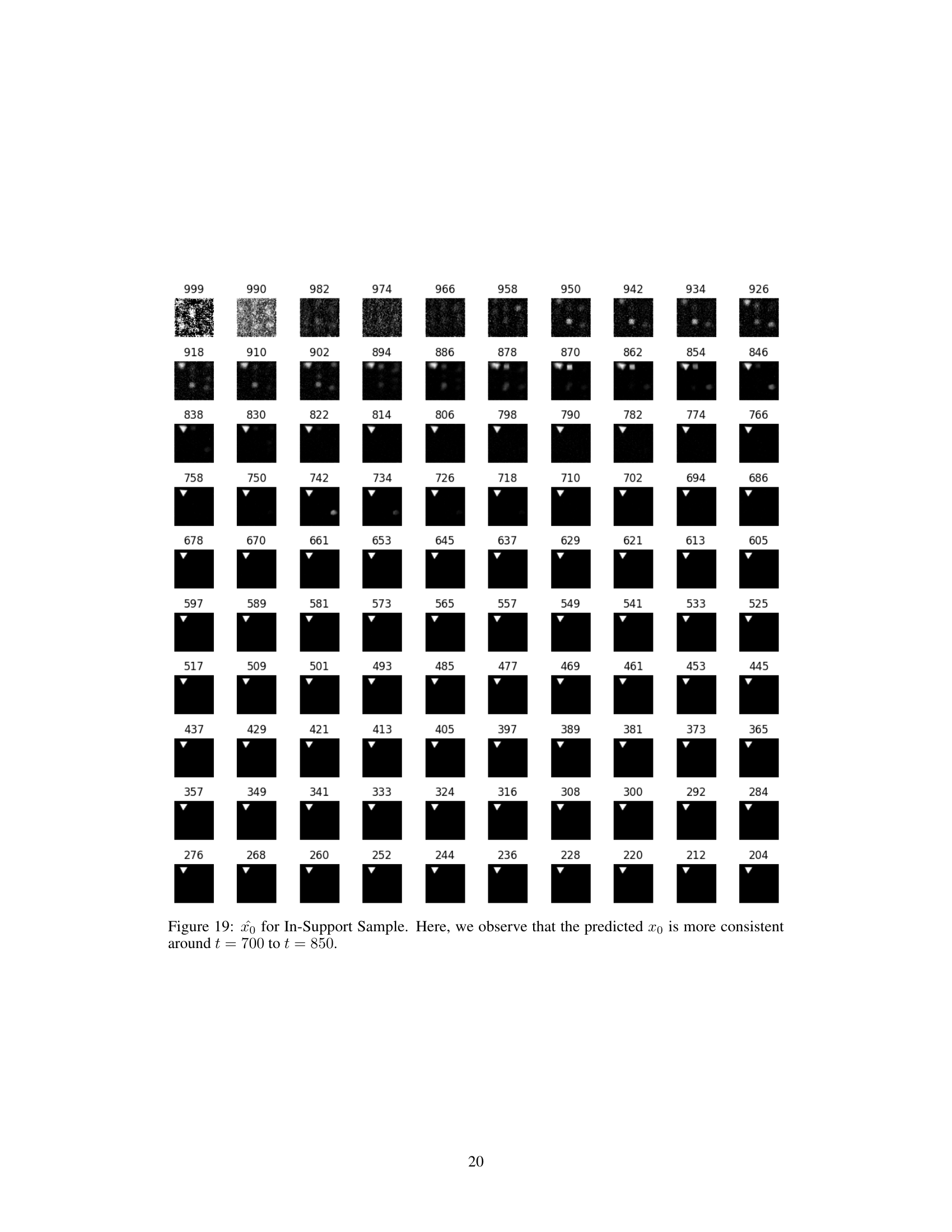

This figure visualizes the variance in the predicted values of x0 (the final image) during the reverse diffusion process for both hallucinated and non-hallucinated samples in 1D and 2D Gaussian datasets. The plots show the trajectories of x0 over time. Hallucinated samples exhibit high variance, particularly in the final time steps, while non-hallucinated samples stabilize their predictions. This difference in variance is used as a metric to distinguish between hallucinated and non-hallucinated samples.

This figure shows the distribution of the proposed hallucination metric for three different datasets: 1D Gaussian, 2D grid of Gaussians, and Simple Shapes. The metric measures the variance in the trajectory of the predicted noise during the reverse diffusion process. Hallucinated samples, which lie outside the support of the training distribution, exhibit higher variance than in-support samples. The histograms clearly show a separation between the two groups, indicating the effectiveness of the metric in detecting hallucinations.

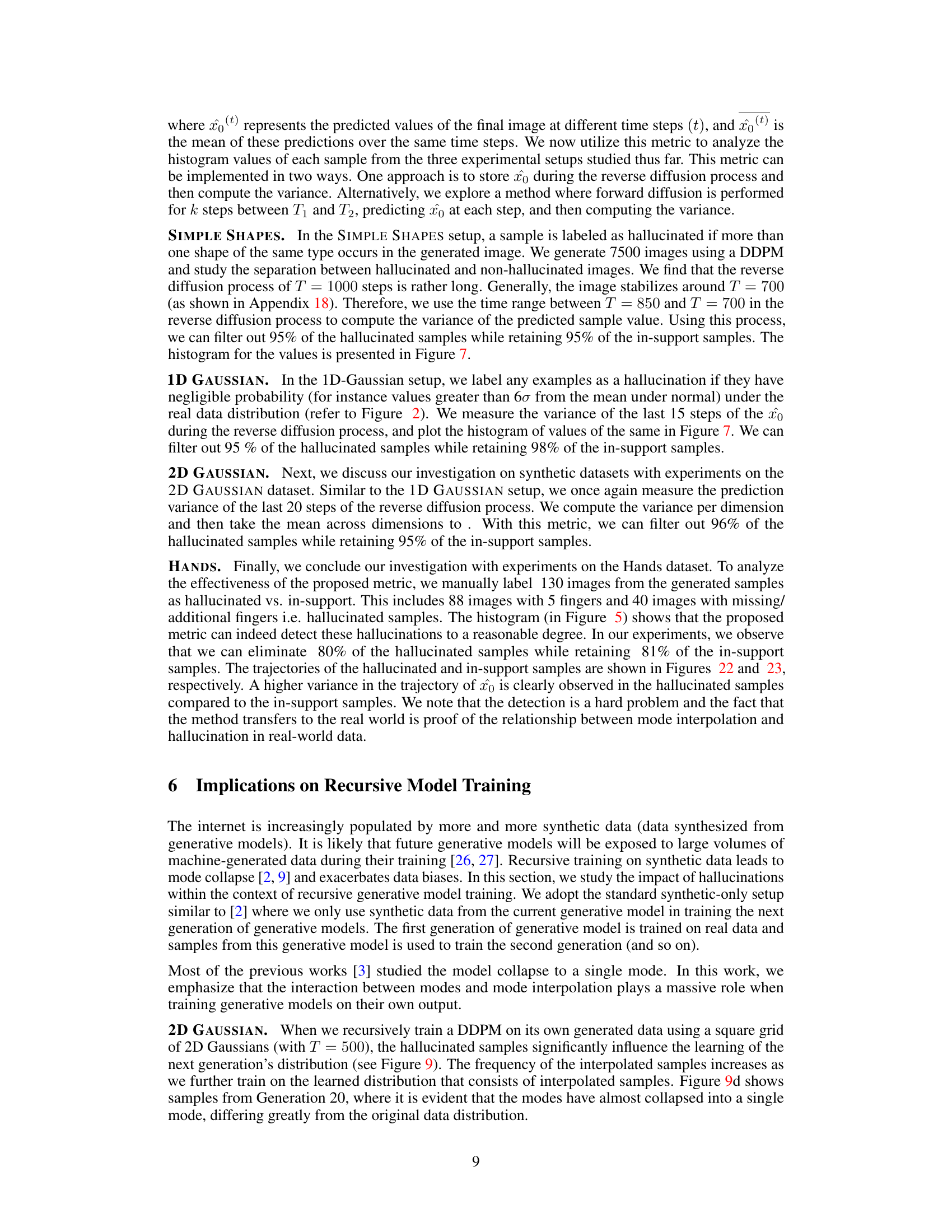

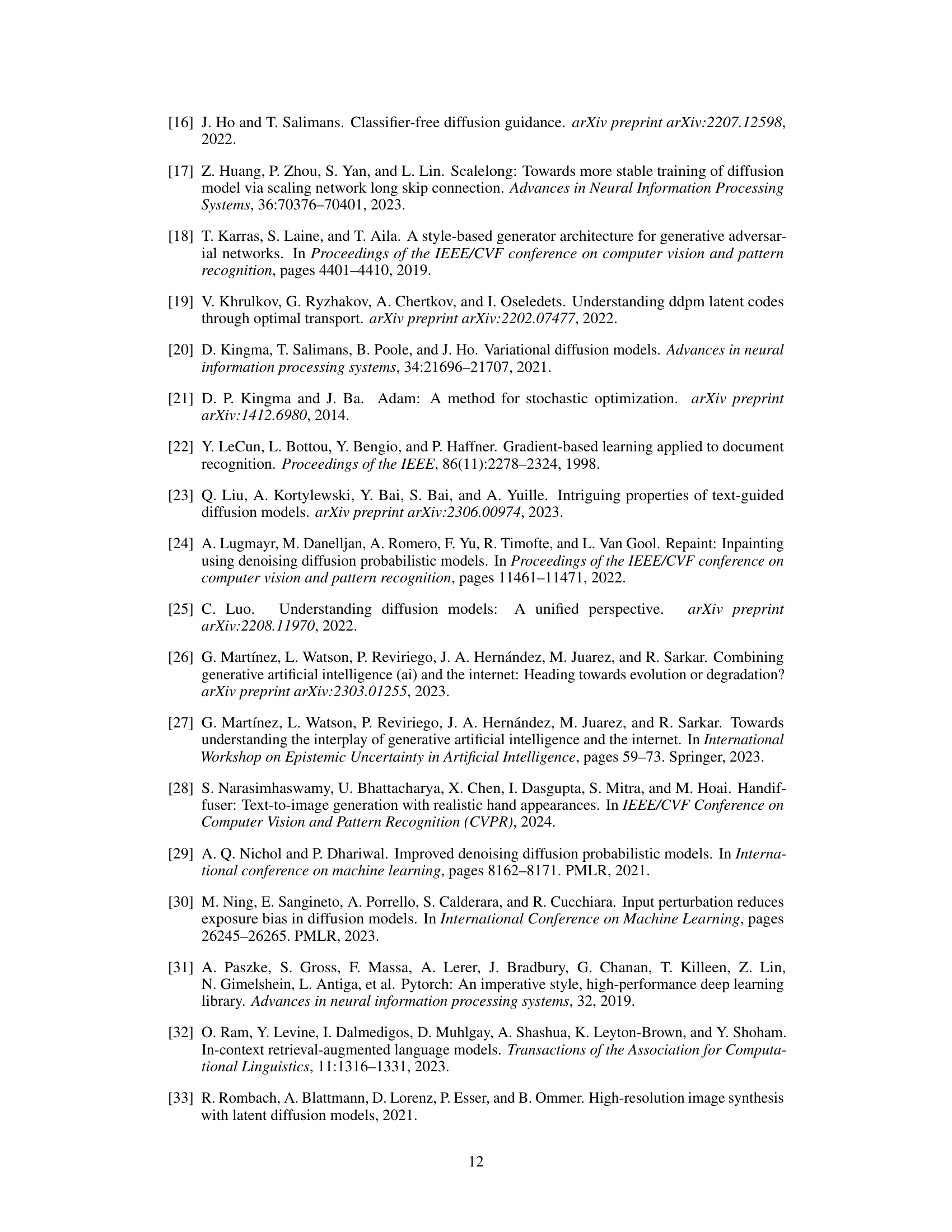

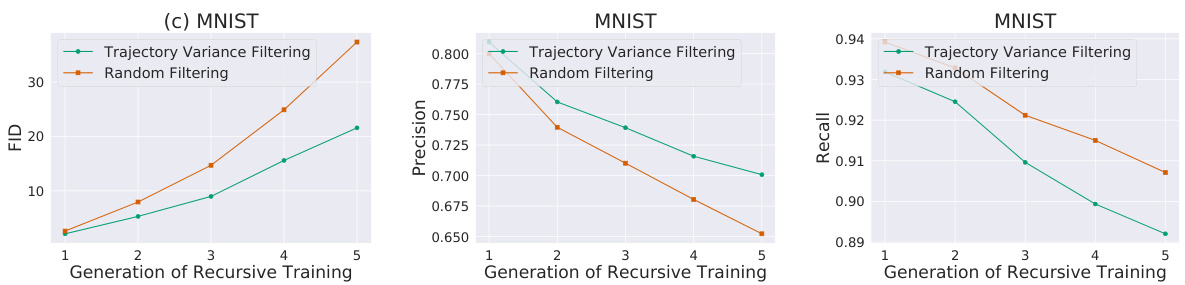

This figure shows the effectiveness of pre-emptive hallucination filtering in recursive model training. Three datasets are used: a 2D grid of Gaussians, simple shapes, and MNIST. The ‘Trajectory Variance Filtering’ method significantly reduces the percentage of hallucinated samples in the first two datasets over multiple generations, compared to random filtering. For MNIST, the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) shows that pre-emptive filtering slows down model collapse.

This figure visualizes the effect of recursive training on a 2D Gaussian dataset. Each subplot shows the generated data distribution for a different generation of the model. As the model is retrained on its own output, the initially well-defined modes start to blur and eventually collapse, indicating a loss of diversity and mode collapse.

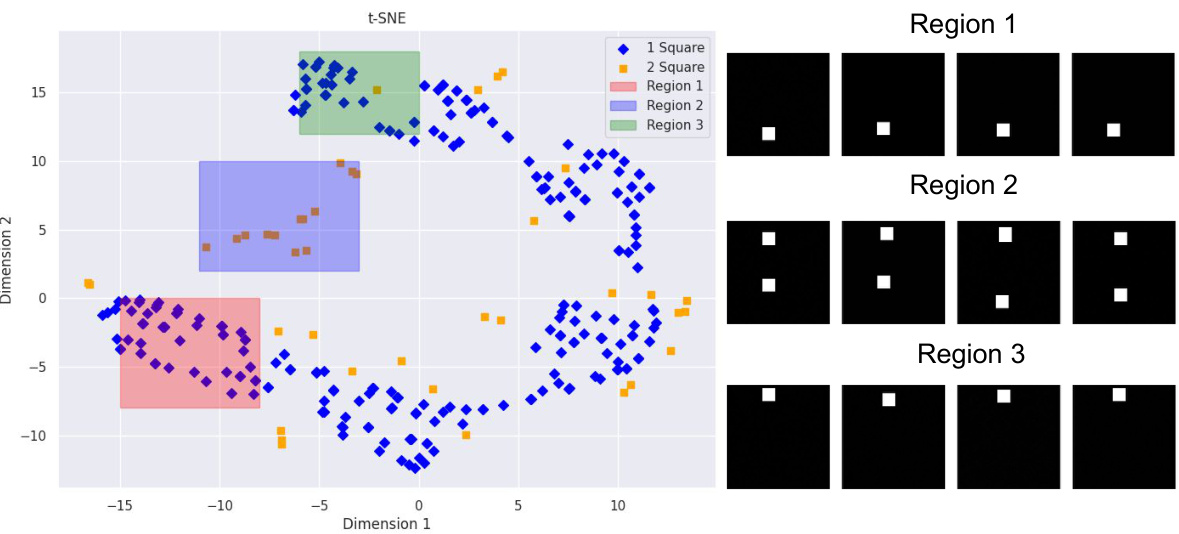

This figure visualizes the results of t-SNE dimensionality reduction applied to the bottleneck layer of a U-Net used in the SIMPLE SHAPES experiment. Three distinct regions in the reduced feature space represent different image characteristics. Region 1 corresponds to images with a single square in the bottom half, Region 3 corresponds to images with a single square at the top, and Region 2, an interpolated region, contains images with two squares (one at the top and one at the bottom), demonstrating the hallucination phenomenon of mode interpolation.

This figure demonstrates the results of training Variational Diffusion Models (VDM) and Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM) on a 2D Gaussian distribution with 10,000 samples. The first three columns show the sample distributions generated by VDMs with varying training timesteps (T) and sampling timesteps (T’). The fourth column illustrates a DDPM trained on an imbalanced 2D Gaussian dataset, highlighting the effect of imbalanced data on the generated samples. Finally, the last column displays samples generated using the true score function for comparison. The figure showcases how different training parameters and data distributions influence the quality and characteristics of generated samples.

This figure shows the impact of the number of training samples and the distance between Gaussian modes on the mode interpolation phenomenon in diffusion models. The plots demonstrate that increasing the number of training samples reduces the generation of samples in the regions between modes, and that greater distance between the modes also decreases this effect. This effect is consistent with the concept of mode interpolation, where the model generates samples between existing modes, even when such samples are not present in the training data.

This figure shows the results of training a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) on a 1D Gaussian mixture distribution. The top row demonstrates how increasing the number of training samples reduces the density of generated samples in the regions between the Gaussian modes (interpolation). The bottom row shows that increasing the distance between modes also reduces this interpolation effect.

This figure shows the results of an experiment to demonstrate mode interpolation in a 1D Gaussian mixture model. The experiment varies the number of training samples and the positions of Gaussian modes, demonstrating how smoothly the diffusion model interpolates between modes, even generating samples in areas with zero probability density in the original distribution. The density of these interpolated samples decreases with the increase of training samples. It also shows that distant modes have less interpolation than near modes.

This figure shows the results of experiments with a 1D Gaussian mixture model. The top row shows the probability density function (PDF) of the true data distribution (red) and the density histogram of samples generated by a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) trained on different numbers of samples from the true distribution (blue). The results show that the DDPM tends to generate samples in the regions between the Gaussian modes (mode interpolation), even though these samples are not present in the training data. The amount of mode interpolation decreases as the number of training samples increases. The bottom row shows that the amount of mode interpolation also depends on the distance between the modes: more distant modes lead to less interpolation.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of preemptively filtering out hallucinated samples (using a variance-based metric) before training subsequent generations of diffusion models. The experiment is performed on three datasets: 2D Gaussian, Simple Shapes, and MNIST. Results show that this method significantly reduces hallucinations across generations compared to random filtering, and in the case of MNIST, delays model collapse.

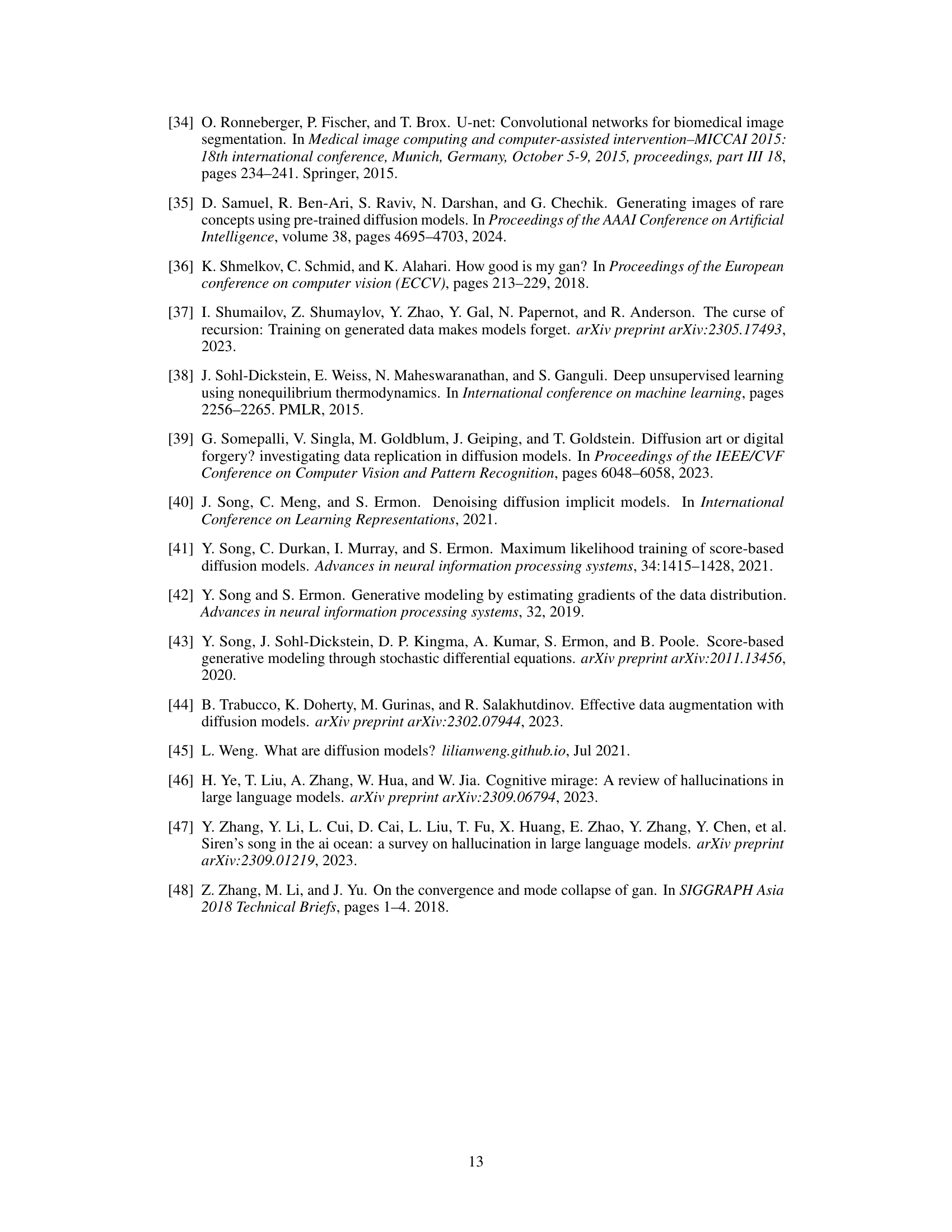

This figure shows the comparison of an original dataset and a generated dataset using a diffusion model. The top part shows a dataset with simple shapes (triangle, square, and pentagon) where each shape appears at most once per image. The bottom part shows a dataset with high-quality images of hands. The generated datasets show that diffusion models can generate images with multiple occurrences of the same shape (hallucinations) or images of hands with additional fingers, indicating a failure mode of diffusion models.

This figure shows the results of training a diffusion model on two different datasets. The top half shows a dataset of simple shapes (triangles, squares, pentagons) where each image contains at most one of each shape. The generated samples, however, contain hallucinations: images with multiple instances of the same shape. The bottom half shows a similar experiment using images of hands. The original dataset contains images of hands with the correct number of fingers. The model generates images of hands with extra or missing fingers, demonstrating the problem of mode interpolation in diffusion models.

This figure shows the results of training a diffusion model on two different datasets. The top part shows a dataset of simple shapes (triangles, squares, pentagons) where each image contains at most one of each shape. The generated samples, however, contain multiple instances of the same shape, demonstrating the phenomenon of hallucination. The bottom part shows similar results on a dataset of hands, where the generated images frequently contain extra or missing fingers.

This figure shows examples of ‘hallucinations’ in diffusion models. The top row illustrates the difference between a dataset of simple shapes (triangles, squares, pentagons) and the output of a diffusion model trained on that dataset. The model generates images with multiple instances of the same shape, something not present in the original data. The bottom row shows the same issue with a more realistic example of hand images. A diffusion model trained on hands produces images of hands with extra fingers, which also shows hallucinations.

This figure demonstrates hallucinations in diffusion models. The top half shows a simple dataset of shapes (triangles, squares, pentagons) and the hallucinations that arise from training a diffusion model on this dataset, such as having multiple instances of the same shape in one image, a combination which is not present in the original training dataset. The bottom half shows a similar experiment, this time using high-quality images of hands, which results in hallucinations such as images of hands with extra fingers.

This figure demonstrates the concept of hallucination in diffusion models using two examples. The top part shows a dataset of simple shapes (triangles, squares, pentagons) and the corresponding generated images by a diffusion model. It highlights that the model hallucinates by generating images with combinations of shapes never seen in the training data. The bottom part uses a more realistic example of human hands, showing that the model can generate hands with extra fingers, another example of hallucination.

This figure shows examples of hallucinations in diffusion models. The top part compares a dataset of simple shapes (triangles, squares, pentagons) with samples generated by a diffusion model trained on this dataset. The generated samples contain artifacts such as multiple instances of the same shape, which were not present in the training data. The bottom part shows the same phenomenon for images of human hands: the model generates images of hands with extra or missing fingers, which is a common failure mode of diffusion models.

Full paper#