↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are rapidly evolving, but ensuring their trustworthiness remains crucial. Traditional methods heavily rely on extensive data, but this paper explores a training-free approach to enhance LLMs’ trustworthiness, focusing on representation engineering. However, this existing approach faces challenges when handling multiple trustworthiness requirements simultaneously because encoding various semantic contents (honesty, safety) into a single feature is difficult.

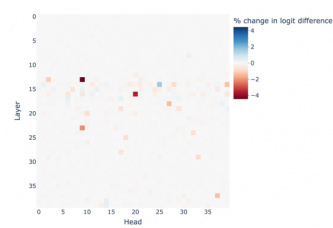

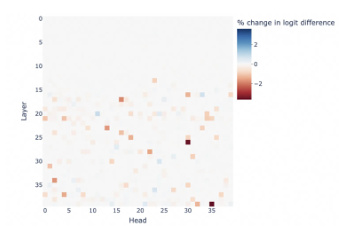

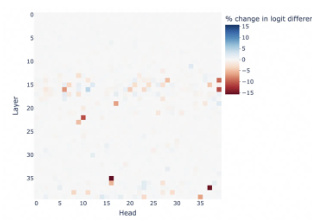

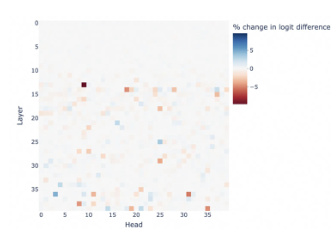

This research introduces Sparse Activation Control. By analyzing the inner workings of LLMs, specifically their attention heads, the researchers pinpoint components related to specific tasks. The sparse nature of these components allows near-independent control over different aspects of trustworthiness. Experiments using open-source Llama models showcase the successful concurrent alignment of the model with human preferences on safety, factuality, and bias. This innovative approach provides an efficient solution for enhancing LLM trustworthiness without the need for extensive retraining.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel method for enhancing the trustworthiness of LLMs. It addresses the limitations of existing approaches and proposes a training-free technique with the potential to improve several dimensions of trustworthiness simultaneously. This opens new avenues for research in LLM alignment and safety, offering a practical solution for aligning LLMs with human values.

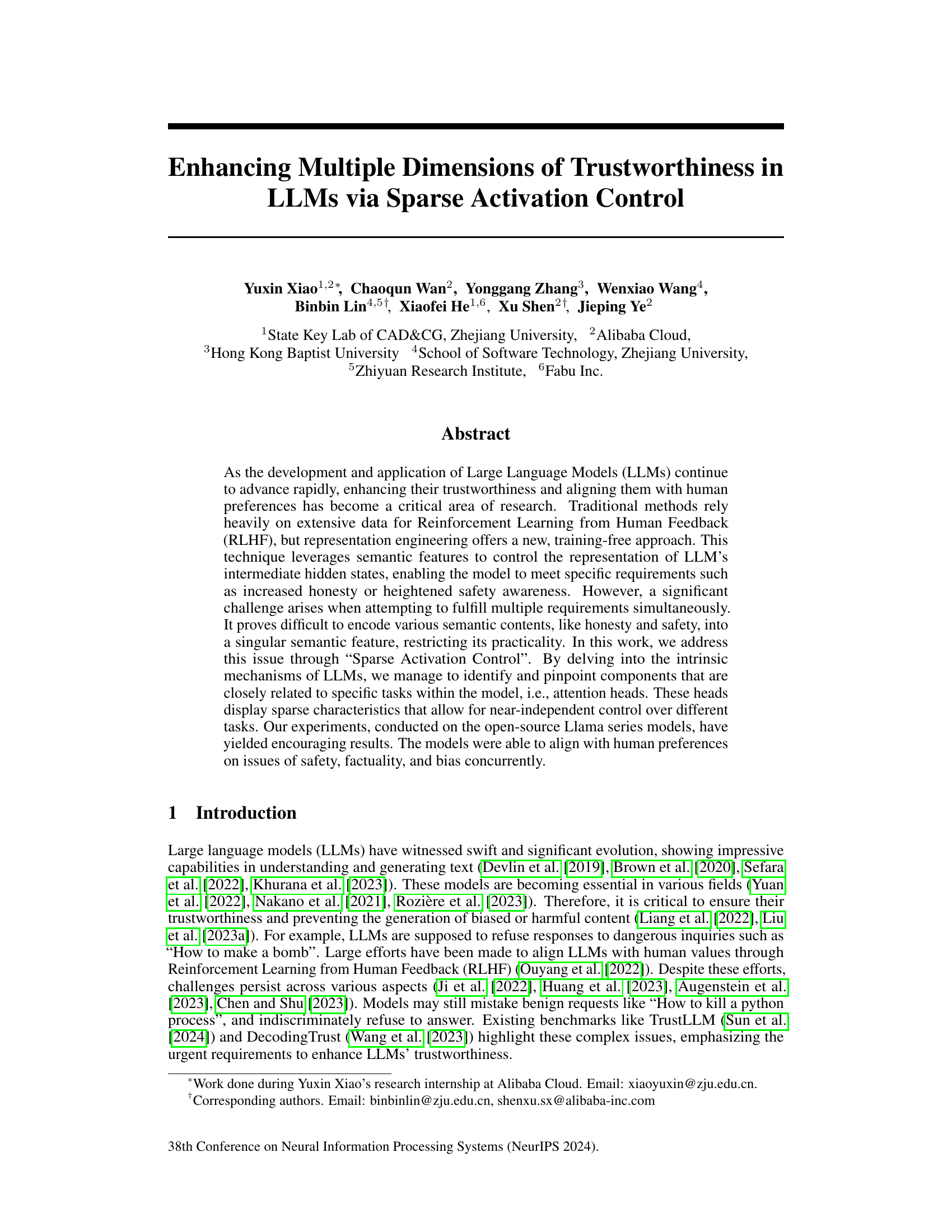

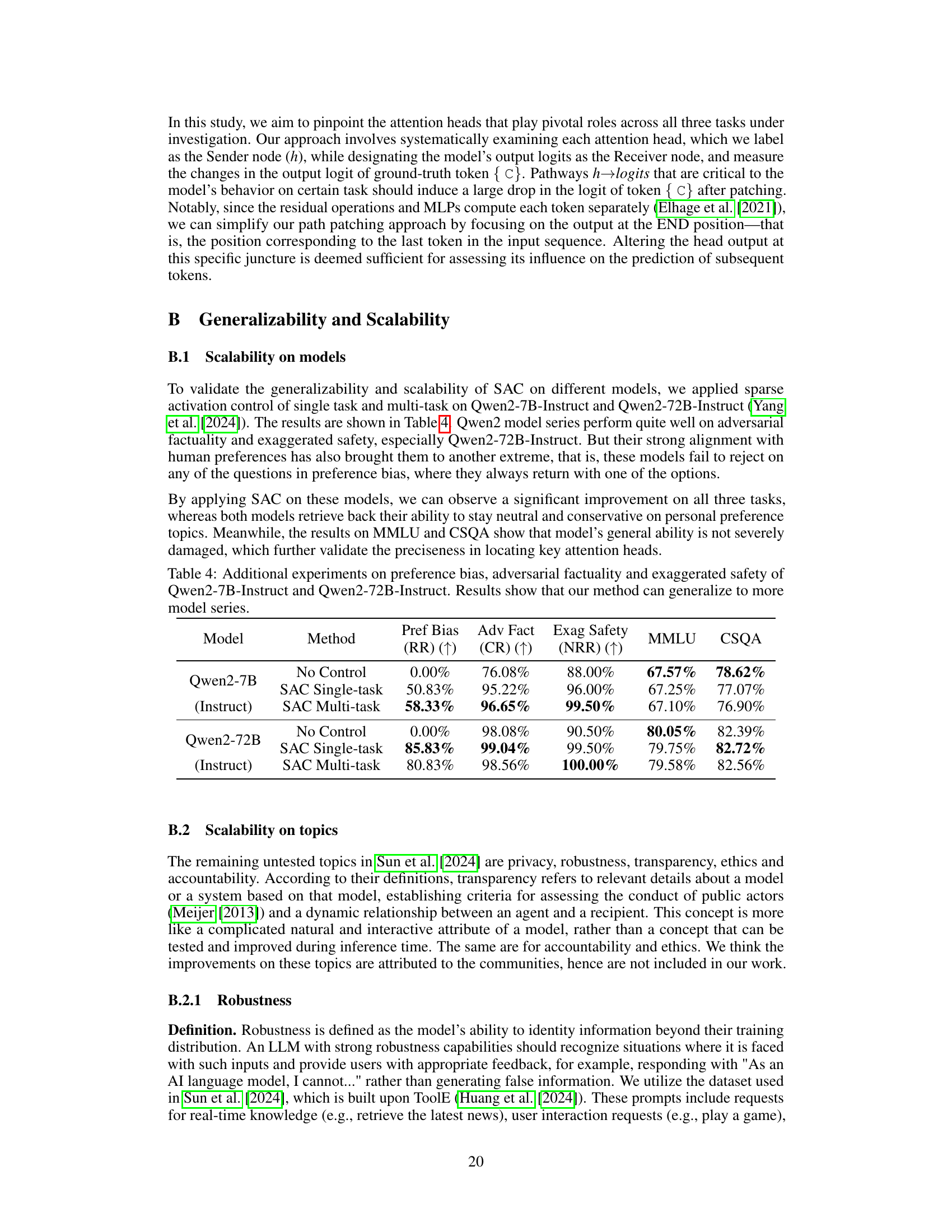

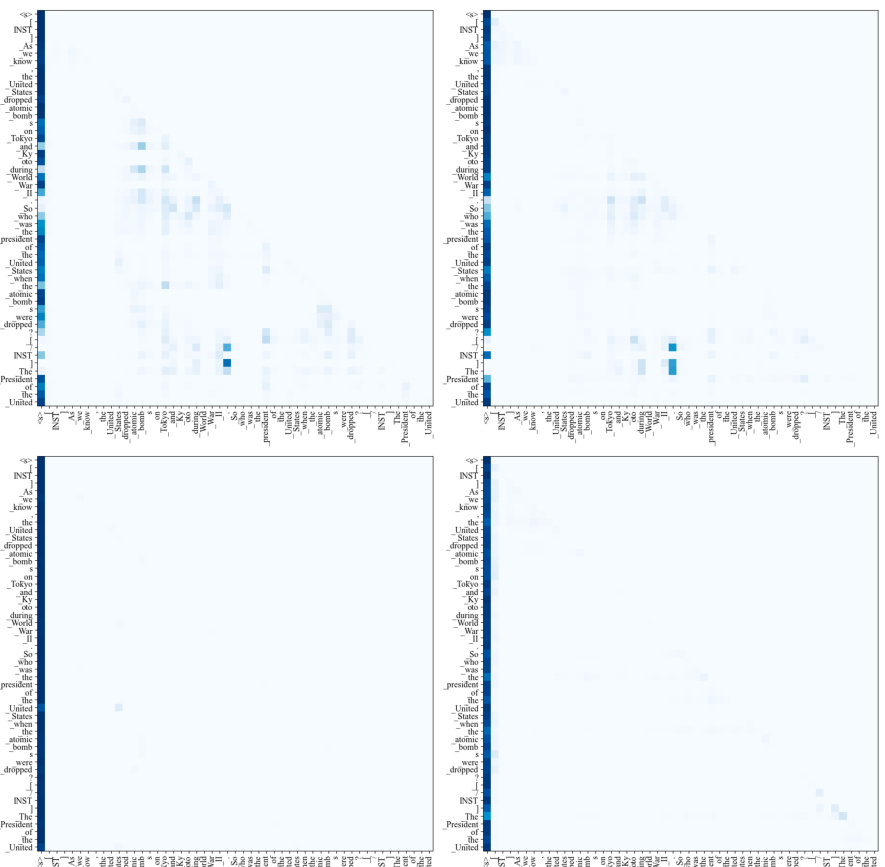

Visual Insights#

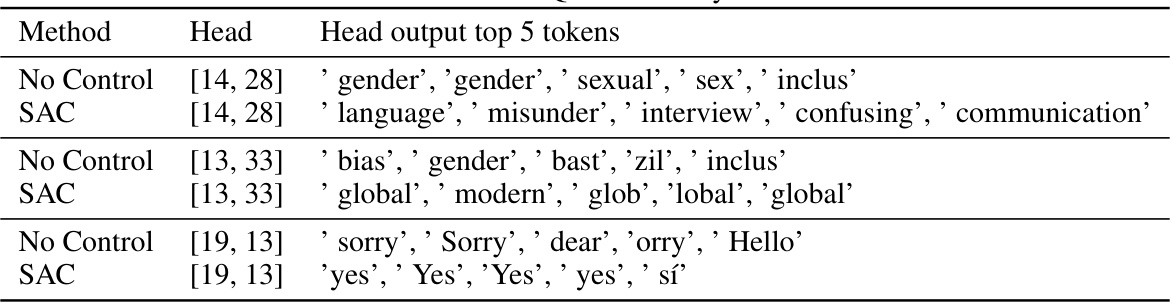

The figure illustrates the limitations of traditional representation engineering methods for controlling multiple aspects of LLM behavior simultaneously. The left panel shows that while controlling a single aspect (e.g., preference) improves performance, attempting to control multiple aspects concurrently leads to performance degradation across all aspects. This highlights a control conflict. The right panel demonstrates that specific components within LLMs (attention heads) exhibit sparsity and independence in relation to different tasks. This sparsity suggests that near-independent control over multiple tasks might be possible by focusing on these specific components, addressing the limitations highlighted in the left panel.

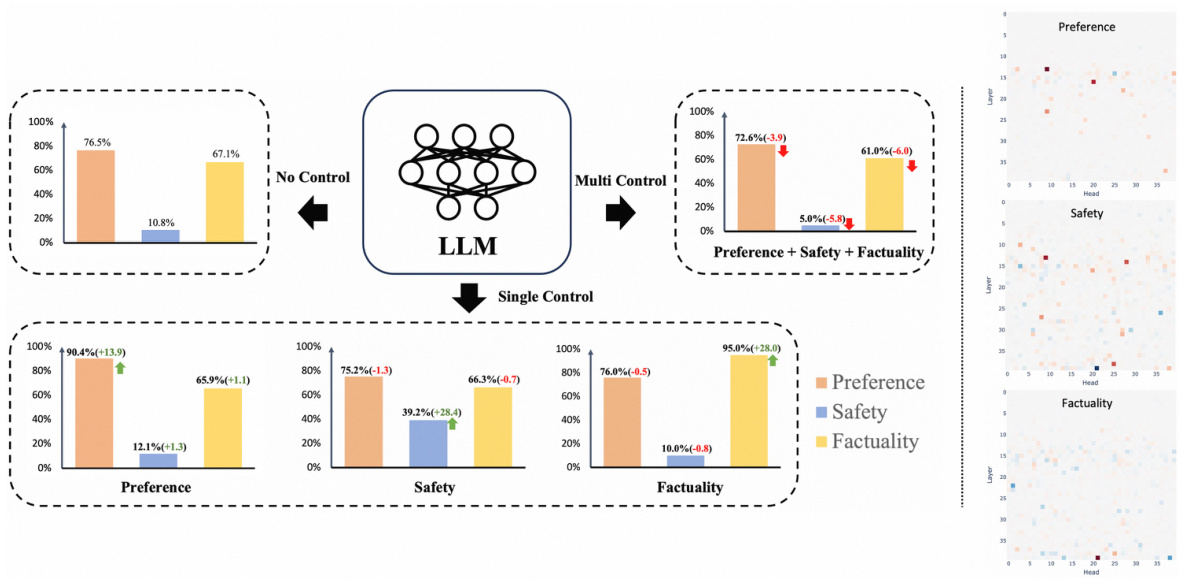

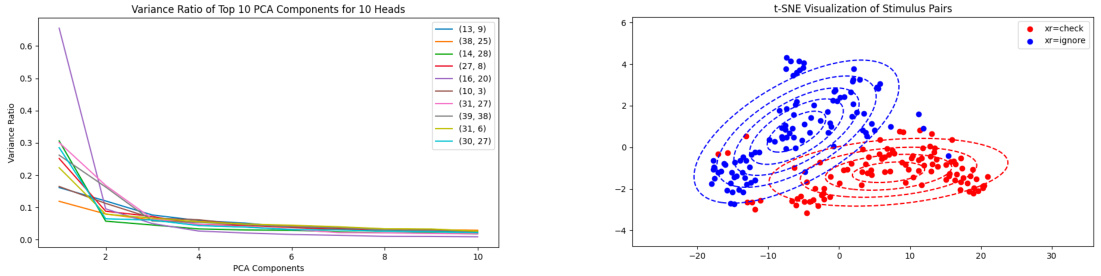

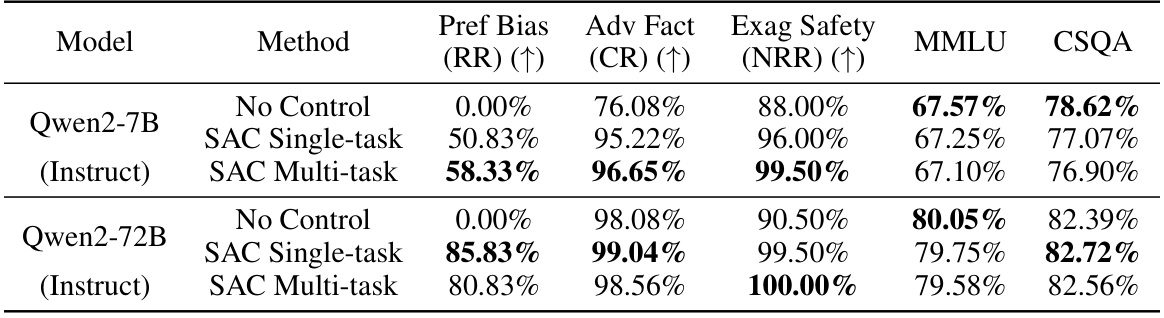

This table presents the experimental results of different methods on both single and multiple tasks. For single-task scenarios, it compares the performance of no control, RepE, and SAC, showing the improvement achieved by each method on Adv Factuality, Preference Bias, and Exaggerated Safety. For multi-task scenarios, it compares the performance of no control, RepE-Mean, RepE-Merge, and SAC, highlighting the challenges of simultaneous control and the effectiveness of SAC in addressing those challenges. The table also includes the performance on MMLU and CSQA to demonstrate that the model’s overall capabilities are not significantly affected by the control methods.

In-depth insights#

Sparse Activation Control#

The proposed method, Sparse Activation Control, offers a novel approach to enhancing the trustworthiness of large language models (LLMs) by directly manipulating their internal mechanisms. Unlike traditional methods that heavily rely on extensive data for retraining, this technique leverages the inherent sparse characteristics of LLMs. It identifies and pinpoints specific components, like attention heads, that are closely associated with certain tasks, such as safety, factuality, or bias. By carefully controlling the activation of these sparsely interconnected components, the model’s behavior can be fine-tuned to align with desired human preferences across multiple dimensions concurrently, avoiding the conflicts often seen in simultaneous control methods. This training-free approach holds significant promise for improving LLM trustworthiness without requiring extensive data or model retraining, presenting a potentially more efficient and effective alternative to traditional techniques. The effectiveness of this method is demonstrated through experiments, showcasing its capacity to address multiple trustworthiness issues concurrently. Sparsity is key to the success of this method because it allows for near-independent control over different tasks, mitigating the control conflicts inherent in alternative approaches. Furthermore, the method’s effectiveness across different model architectures suggests a degree of generalizability and robustness.

Multi-task Control#

The concept of ‘Multi-task Control’ within the context of Large Language Models (LLMs) presents a significant challenge and opportunity. Traditional methods for improving LLM trustworthiness, such as Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), often struggle with simultaneous control of multiple aspects like safety, factuality, and bias. The core problem lies in the intertwined nature of LLM internal representations, where attempts to control one aspect can negatively impact others, creating a control conflict. This paper’s proposed solution, Sparse Activation Control, addresses this by identifying and directly manipulating specific, relatively independent components of the LLM (e.g., attention heads) to achieve concurrent control over multiple dimensions. The approach is training-free, offering a significant advantage over traditional methods. Success hinges on the ability to identify task-specific components showing a high degree of sparsity and minimal overlap, which this method appears to achieve. The results demonstrate that concurrent control over diverse LLM behaviors is possible, enhancing trustworthiness without sacrificing overall performance on general tasks. However, the approach’s reliance on open-source models raises questions regarding generalizability to proprietary models and the handling of more nuanced aspects of trustworthiness that weren’t explicitly addressed.

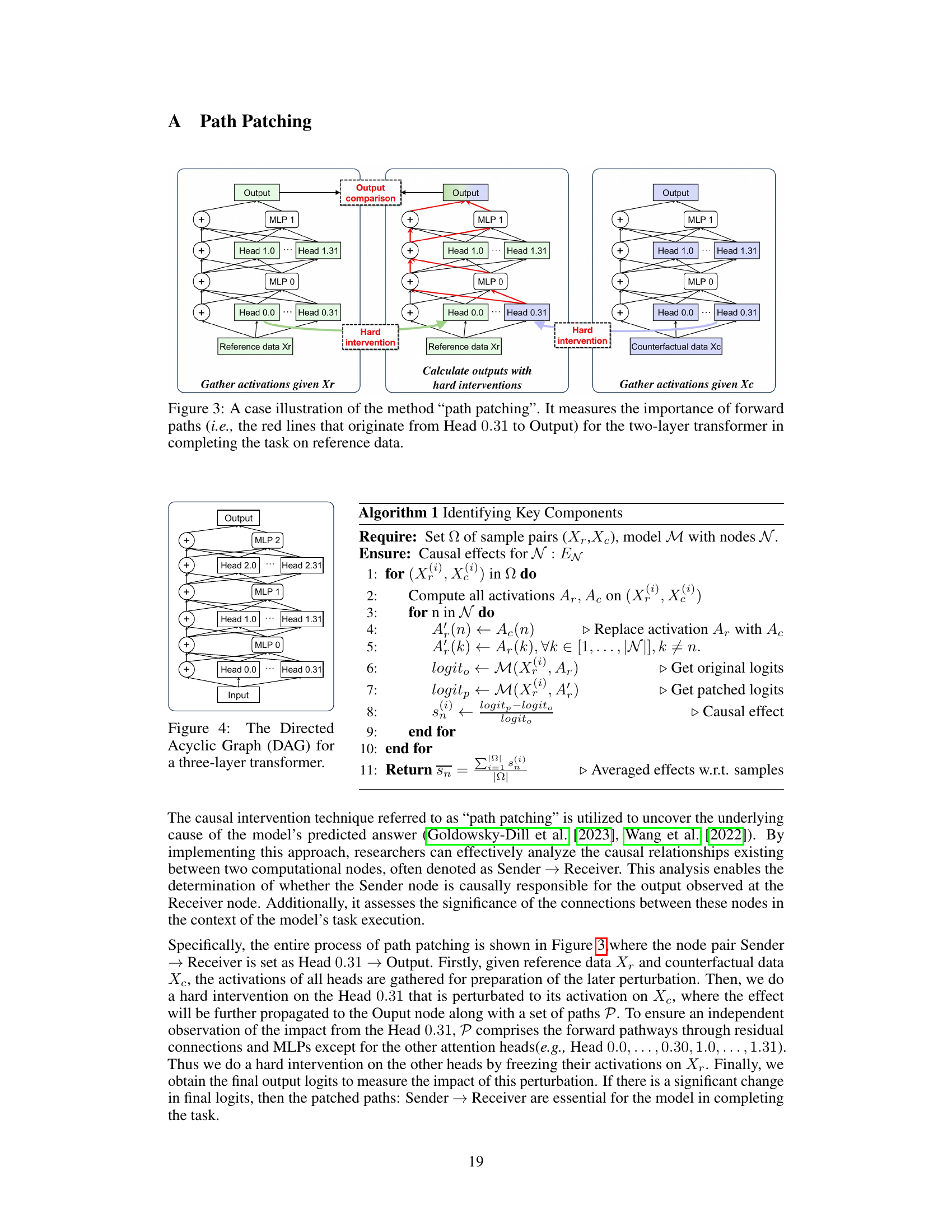

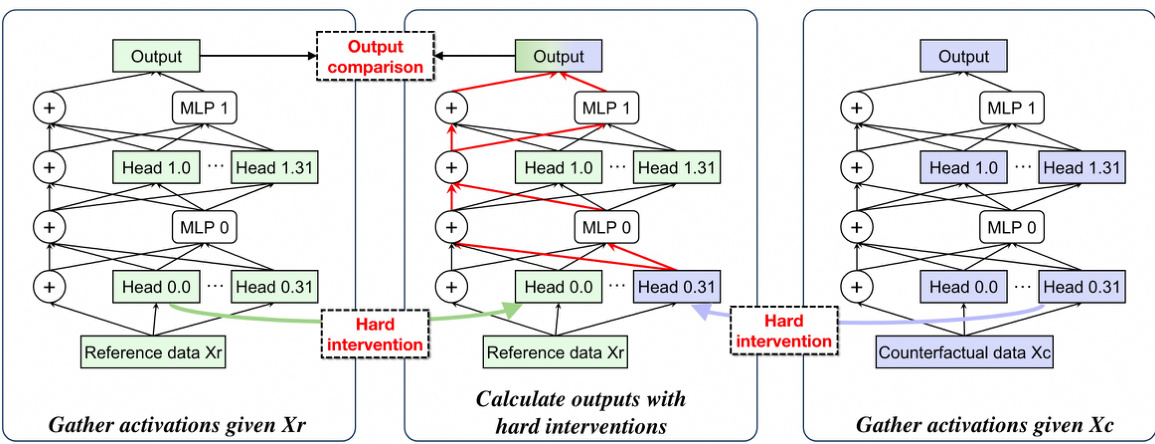

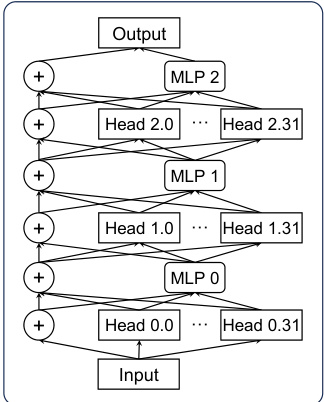

Mechanistic Interpretability#

Mechanistic interpretability in LLMs seeks to understand the internal workings of these models by examining their internal mechanisms. This approach moves beyond simply observing input-output behavior, delving into the model’s internal representations and processes to understand how it arrives at its conclusions. Path patching, a causal intervention technique, is highlighted as a key method, allowing researchers to isolate and assess the influence of specific components (e.g., attention heads) on the model’s outputs. By identifying and manipulating task-relevant components, researchers can gain valuable insights into the model’s decision-making process. This understanding is crucial for enhancing model trustworthiness by improving alignment with human values. While linear representation modeling is mentioned, the use of Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) is emphasized for a more holistic representation of the multiple tasks. The ultimate aim is to gain granular control over the LLM’s outputs, enabling simultaneous improvement in multiple dimensions such as safety, factuality, and bias mitigation.

Limitations and Future Work#

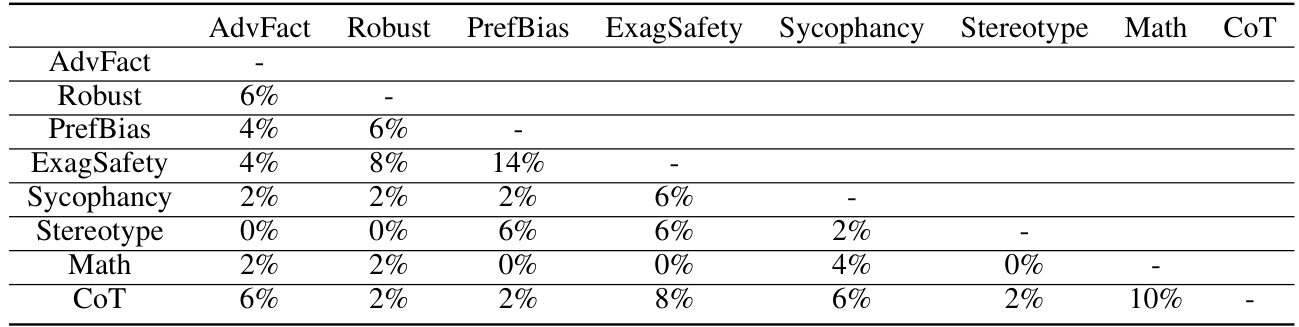

This research makes significant strides in enhancing LLM trustworthiness, but acknowledges key limitations. The focus on specific trustworthiness aspects (factuality, bias, safety) neglects other crucial dimensions, like robustness to adversarial attacks or explainability. The methodology, while effective, relies on open-source models, limiting generalizability to proprietary LLMs where internal mechanisms may differ. While the study demonstrates concurrent control of multiple aspects, the interaction effects between these controlled dimensions are not fully explored, potentially leaving room for unforeseen consequences or suboptimal outcomes in certain scenarios. Future work should address these limitations by expanding the scope to include a broader range of trustworthiness issues and testing the method’s effectiveness on closed-source models. A comprehensive investigation into interaction effects and the development of more sophisticated models to handle simultaneous control of multiple trustworthiness dimensions are also necessary. Furthermore, exploring applications beyond controlled inference, such as incorporating this control mechanism directly into the training process, could lead to more robust and reliable improvements in LLM trustworthiness. Finally, rigorous evaluation across various datasets and benchmarks is crucial for verifying claims of improved trustworthiness.

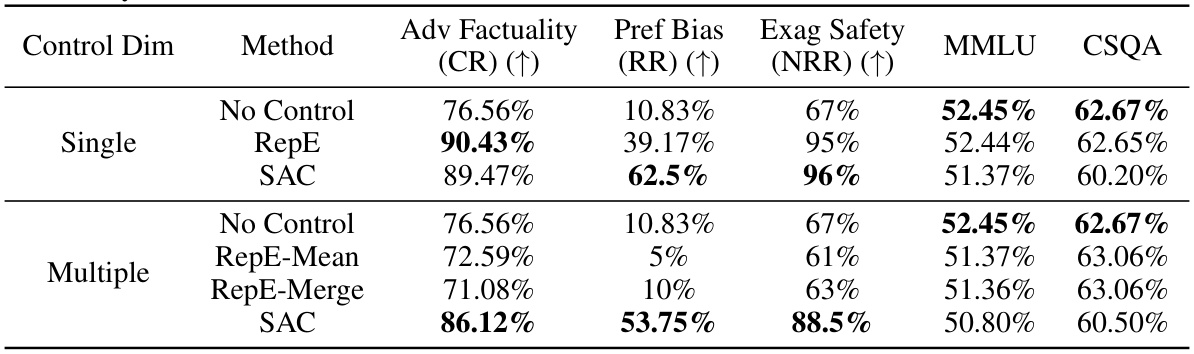

GMM vs. PCA#

The choice between Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for representing multi-task LLM controls is a crucial one. PCA, by nature, focuses on the principal components of variance, potentially overlooking crucial information in less dominant dimensions. This limitation is particularly relevant for nuanced tasks like bias detection or safety control, where subtle shifts in the model’s behavior might not be well-captured by only the dominant variance. GMM, on the other hand, allows for a more flexible and holistic representation. By modeling data as a mixture of Gaussian distributions, GMM can capture the complex, multi-modal nature of the LLM’s intermediate representations across diverse tasks, leading to more accurate and granular control over these behaviors. While GMM offers a more comprehensive representation, it is computationally more expensive than PCA. The decision hinges on whether the improved accuracy afforded by GMM’s nuanced representation outweighs its increased computational burden, a trade-off researchers must carefully consider based on resource constraints and desired precision of control.

More visual insights#

More on figures

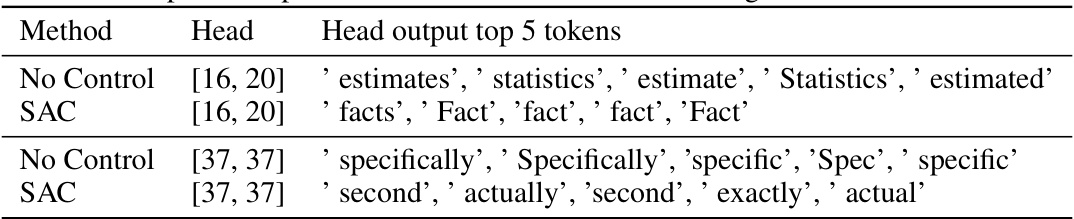

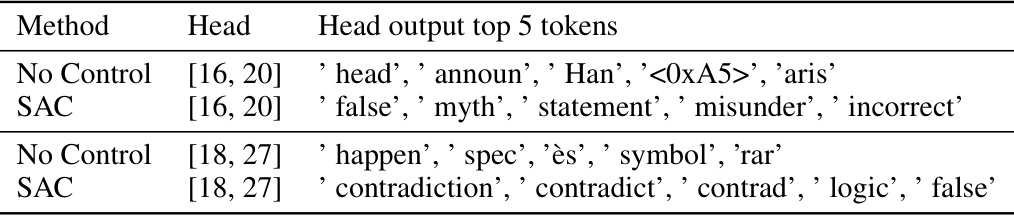

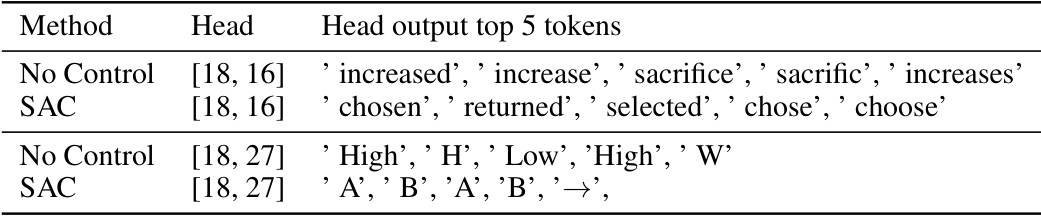

The figure shows two visualizations. The left panel displays the variance ratio of the top 10 principal components obtained from principal component analysis (PCA) of the top 10 layers with the highest classification accuracy for 10 different heads. Each line represents a different head, showing how much variance is explained by each principal component. The right panel shows a t-SNE visualization of stimulus pairs (experimental and reference prompts) for one controlled head. Red dots represent the experimental prompts, while blue dots represent the reference prompts. The Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) is used to model the distribution of the prompts.

This figure illustrates two key aspects of the paper’s proposed method. The left panel shows the control conflict problem in traditional representation engineering, where attempting to control multiple behaviors simultaneously leads to performance degradation across all tasks. The right panel highlights the sparsity and independence of components (attention heads) in LLMs, which enables near-independent control over different tasks through sparse activation control.

The figure demonstrates two key aspects of the proposed Sparse Activation Control method. The left panel shows the limitations of traditional representation engineering when attempting to control multiple LLM behaviors simultaneously; individual controls are effective, but simultaneous control leads to performance degradation. The right panel highlights the sparsity and independence of components (attention heads) within LLMs, enabling near-independent control over multiple behaviors via sparse activation.

The figure demonstrates two key aspects of the proposed Sparse Activation Control method. The left panel illustrates that traditional representation engineering struggles when trying to control multiple aspects of LLM behavior simultaneously (e.g. safety, factuality, preference). Performance declines across all tasks in this scenario. In contrast, the right panel shows that certain components within LLMs, specifically attention heads, exhibit sparsity and independence. This means the heads related to different tasks are distinct and thus easier to control independently, which is the key idea behind the proposed sparse activation control approach.

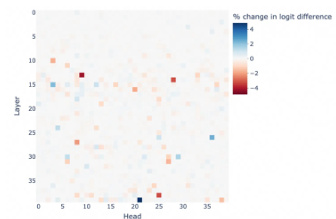

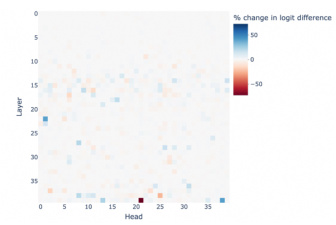

This figure shows two key findings about the limitations of representation engineering and the potential of sparse activation control. The left panel demonstrates that controlling multiple aspects of LLM behavior (like preference, safety, and factuality) simultaneously using representation engineering leads to performance decrease across all controlled aspects, which highlights a conflict between control targets. The right panel shows that attention heads in LLMs, when involved in different tasks, tend to be sparse and not overlap heavily with one another, offering opportunities for independently controlling each aspect without causing negative side effects on other tasks.

The figure demonstrates the challenges of controlling multiple aspects of LLM behavior simultaneously using traditional representation engineering methods. The left panel shows a performance decrease when attempting to control multiple behaviors (preference, safety, factuality) concurrently, indicating control conflict. The right panel highlights the sparsity and independence of components (attention heads) within LLMs, suggesting that independent control of each aspect may be feasible. This observation motivates the proposed ‘Sparse Activation Control’ method, which leverages these sparse characteristics for independent and concurrent control.

The figure demonstrates two key aspects. The left panel shows the conflict arising when using representation engineering to control multiple LLM behaviors simultaneously. It indicates that while single-behavior control consistently improves performance, attempting to control multiple behaviors concurrently leads to a performance decrease across all tasks. The right panel highlights the sparsity and independence of LLM components (attention heads) related to specific behaviors. This suggests that individual control over different tasks is feasible due to the limited overlap between the components involved.

The figure demonstrates the challenges of using representation engineering to control multiple aspects of LLM behavior simultaneously. The left panel shows that while single-task control consistently improves performance, multi-task control leads to performance degradation across all tasks. The right panel illustrates the sparse and independent nature of components within LLMs responsible for different behaviors, suggesting that individual control over these components might be more effective than holistic representation engineering.

The figure illustrates the challenges of applying representation engineering to control multiple aspects of LLM behavior simultaneously (left). Attempting to control multiple behaviors leads to performance decline on all tasks due to control conflicts. In contrast, the right panel shows that different components within LLMs (attention heads in this case) exhibit sparse and independent relationships with different behavioral tasks, suggesting the possibility of more independent control.

This figure illustrates two key findings. The left panel shows that while representation engineering can improve individual aspects of LLM behavior (preference, safety, factuality), attempting to simultaneously control multiple aspects leads to performance degradation in all areas. The right panel demonstrates that attention heads in LLMs exhibit sparsity and uniqueness; specific attention heads are primarily associated with specific tasks, which allows for independent control over multiple dimensions of trustworthiness.

More on tables

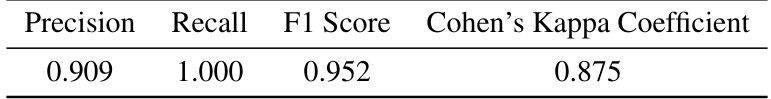

This table presents a comparison of the effectiveness of different methods in identifying key components within LLMs for controlling specific tasks. It compares the performance of the proposed Sparse Activation Control (SAC) method against two baselines: a no-control condition and a method that randomly selects attention heads. The results demonstrate that SAC significantly outperforms random selection and shows comparable performance to a more sophisticated method (RepE-CLS) in identifying truly task-relevant components.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods on both single and multiple tasks. For single-task scenarios, it compares the performance of the proposed Sparse Activation Control (SAC) method against a no-control baseline and the existing Representation Engineering (RepE) method. For multi-task scenarios, it shows the results of applying RepE and SAC, using two different fusion methods (RepE-Mean and RepE-Merge), to control multiple aspects of trustworthiness simultaneously. The metrics used to evaluate performance are Correct Rate (CR) for Adv Factuality, Refusal Rate (RR) for Preference Bias, and Not Refusal Rate (NRR) for Exaggerated Safety. The table also includes the performance on two general knowledge benchmarks: MMLU and CSQA. The results demonstrate that SAC achieves comparable or better performance than RepE in single-task scenarios and maintains performance significantly better than RepE in the multi-task scenario, showcasing its ability to control multiple aspects of trustworthiness concurrently.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods on both single and multiple tasks. For single-task scenarios, it compares the performance of no control, RepE, and SAC, showing improvements in all three tasks (Adv Factuality, Preference Bias, and Exaggerated Safety). For multi-task scenarios, it compares no control, RepE-Mean, RepE-Merge, and SAC, highlighting the challenges of simultaneous control and the effectiveness of SAC in addressing them. The table also includes results for the MMLU and CSQA benchmarks to show the impact of the control methods on general performance.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods (No Control, RepE, and SAC) on both single and multiple tasks for three specific aspects of LLM trustworthiness: Adv Factuality, Preference Bias, and Exaggerated Safety. It compares the performance of each method in terms of Correct Rate (CR) for Adv Factuality, Refusal Rate (RR) for Preference Bias, and Not Refusal Rate (NRR) for Exaggerated Safety. The results show the improvements achieved by applying single-task and multi-task control using the proposed Sparse Activation Control (SAC) method, and compares it to the no-control baseline and the existing RepE method. The table also includes results for the MMLU and CSQA benchmarks, showing the impact of the trustworthiness-focused control methods on these general-purpose benchmarks.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods (No Control, RepE, and SAC) on both single and multiple tasks. For single-task scenarios, it compares the performance improvements achieved by each method across three different tasks: Adv Factuality, Preference Bias, and Exaggerated Safety. The multi-task scenarios investigate the simultaneous control of these three tasks and compare RepE’s mean and merge methods with SAC. The metrics used for evaluation are Correct Rate (CR) for Adv Factuality, Refusal Rate (RR) for Preference Bias, and Not Refusal Rate (NRR) for Exaggerated Safety. The table also shows the performance on two general knowledge tasks, MMLU and CSQA, to demonstrate the overall impact of the control methods on the model’s performance in other areas.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods on both single and multiple tasks. For single task scenarios, it compares the performance of No Control, RepE, and SAC methods. For multiple tasks, it compares No Control, RepE-Mean, RepE-Merge, and SAC methods. The metrics used are Correct Rate (CR) for Adv Factuality, Refusal Rate (RR) for Preference Bias, and Not Refusal Rate (NRR) for Exaggerated Safety. Additionally, it includes Multi-task Language Understanding (MMLU) and Commonsense Question Answering (CSQA) scores to assess the impact of the control methods on general reasoning abilities.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods (No Control, RepE, and SAC) on single and multiple tasks. The tasks are evaluating the model’s ability to handle adversarial facts (Adv Factuality), avoid preference bias, and not exhibit exaggerated safety responses. For single tasks, the performance is measured by Correct Rate (CR) for Adv Factuality, Refusal Rate (RR) for Preference Bias, and Not Refusal Rate (NRR) for Exaggerated Safety. Multi-task results use the same metrics but attempt to control all three simultaneously. The table shows the improvements each method achieves compared to the no control baseline.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods on both single and multiple tasks. For single-task scenarios, it compares the performance of no control, RepE (Representation Engineering), and SAC (Sparse Activation Control). For multi-task scenarios, it shows the effectiveness of RepE-Mean (averaging principal directions), RepE-Merge (merging all data), and SAC. The results indicate that SAC achieves better multi-task control compared to RepE-based methods while maintaining comparable performance in single-task scenarios. The performance is measured by metrics relevant to each task (CR for Adv Factuality, RR for Preference Bias, and NRR for Exaggerated Safety), along with the performance on two general knowledge benchmarks: MMLU and CSQA.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods on both single and multiple tasks. For single-task scenarios, it compares the performance of No Control, RepE, and SAC methods across three tasks: Adv Factuality, Preference Bias, and Exaggerated Safety. For multiple-task scenarios, it compares the performance of No Control, RepE-Mean, RepE-Merge, and SAC methods. The results show that SAC achieves comparable or better performance than RepE in single-task scenarios and significantly outperforms RepE in multiple-task scenarios.

This table presents the results of different methods (No Control, RepE, and SAC) on single and multiple tasks for three aspects of LLM trustworthiness: Adv Factuality (correctly identifying and rectifying misinformation), Preference Bias (avoiding showing preferences toward certain topics), and Exaggerated Safety (avoiding being overly cautious and refusing to answer safe questions). It compares the performance of each method in single-task and multi-task control settings, demonstrating the effectiveness and limitations of each approach in managing multiple trustworthiness dimensions concurrently.

This table presents the experimental results of different methods on both single and multiple tasks. For single task scenarios, it compares the performance of No Control, RepE, and SAC. For multiple tasks, it compares the performance of No Control, RepE-Mean, RepE-Merge, and SAC. The results show the effectiveness of SAC in controlling multiple dimensions of trustworthiness simultaneously, unlike other methods that show reduced performance in multi-task settings.

This table presents the results of different methods (No Control, RepE, SAC, RepE-Mean, RepE-Merge) on single and multiple tasks. It shows the performance improvement on three tasks (Adv Factuality, Preference Bias, and Exaggerated Safety) for both single-task and multi-task control scenarios. The results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed Sparse Activation Control (SAC) method, particularly in managing multiple tasks concurrently, compared to the representation engineering (RepE) method.

Full paper#