TL;DR#

Training large neural networks is computationally expensive, and memory usage is a major bottleneck. Second-order optimizers offer faster convergence than their first-order counterparts but require significantly more memory due to their extensive state variables. This necessitates efficient compression techniques. Current approaches focus on first-order optimizers.

This paper introduces 4-bit Shampoo, the first 4-bit second-order optimizer, successfully addressing these issues. It achieves this by cleverly quantizing the eigenvector matrix of the preconditioner—a core component of second-order optimizers—rather than the preconditioner itself. This approach proves significantly more effective, preserving performance while dramatically reducing memory consumption. The authors also demonstrate the effectiveness of linear square quantization over dynamic tree quantization for this application. This work opens the door to training significantly larger neural networks more efficiently.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large neural networks. It addresses the significant memory constraints imposed by second-order optimizers, a critical limitation hindering the training of massive models. By demonstrating a successful 4-bit quantization method, the research opens avenues for efficient training of larger, more complex models, impacting various fields leveraging deep learning.

Visual Insights#

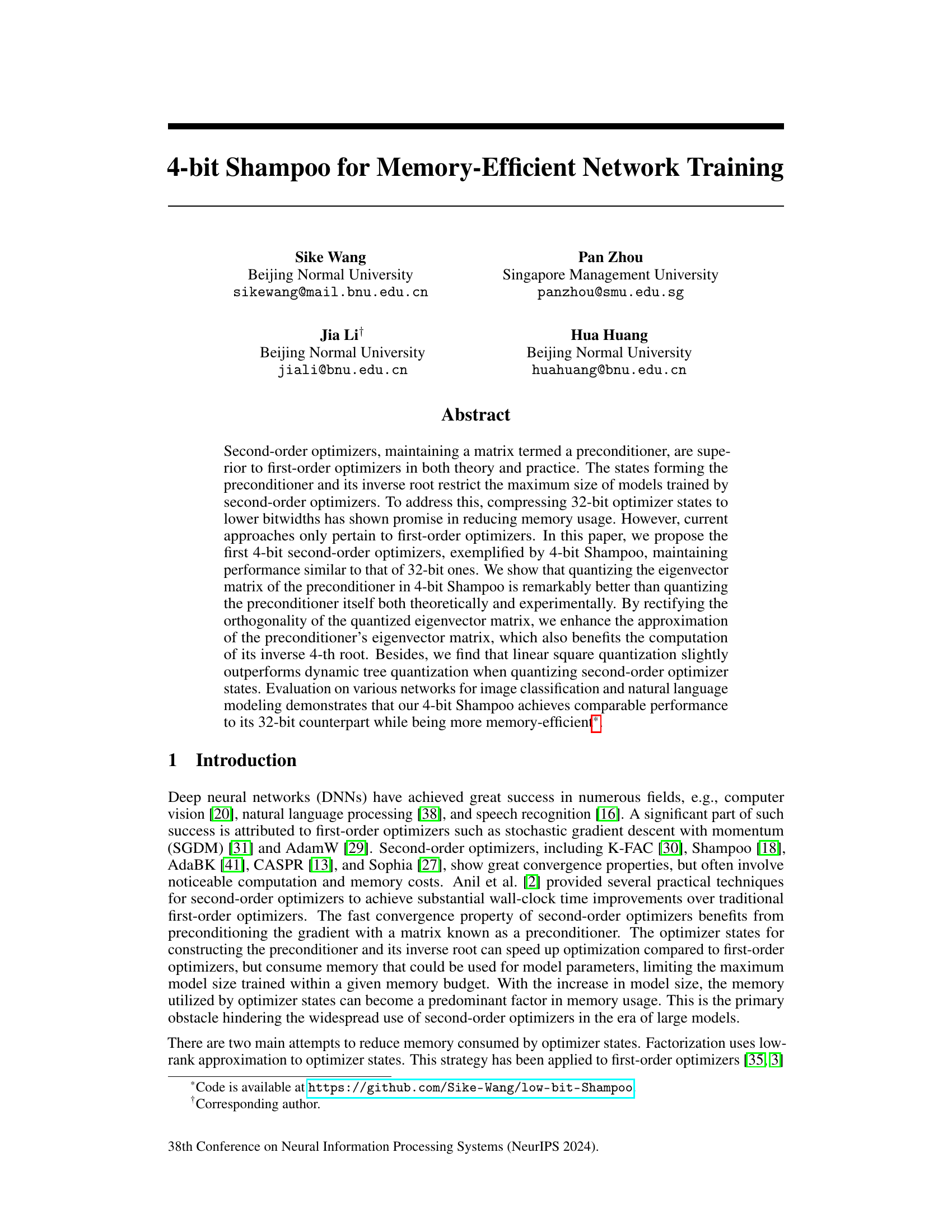

🔼 This figure visualizes the performance of different optimizers on two vision transformer models: Swin-Tiny on CIFAR-100 and ViT-Base/32 on ImageNet-1k. It compares the test accuracy and GPU memory usage of AdamW, AdamW with 32-bit Shampoo, AdamW with a naive 4-bit Shampoo (quantizing the preconditioner), and AdamW with the proposed 4-bit Shampoo (quantizing the eigenvector matrix). The results show that the proposed 4-bit Shampoo achieves comparable accuracy to the 32-bit version while significantly reducing memory consumption.

read the caption

Figure 1: Visualization of test accuracies and total GPU memory costs of vision transformers. 4-bit Shampoo (naive) quantizes the preconditioner, while 4-bit Shampoo (our) quantizes its eigenvector matrix.

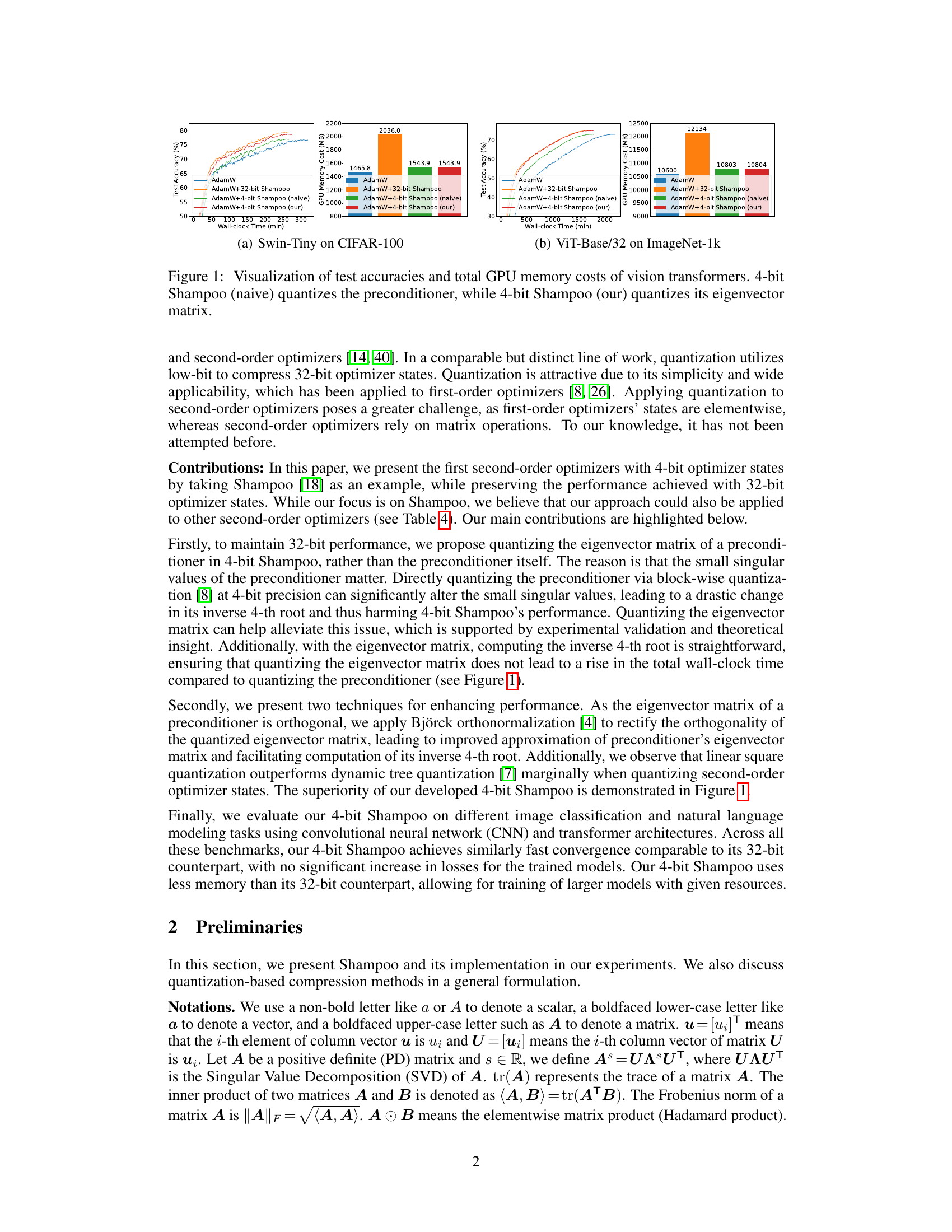

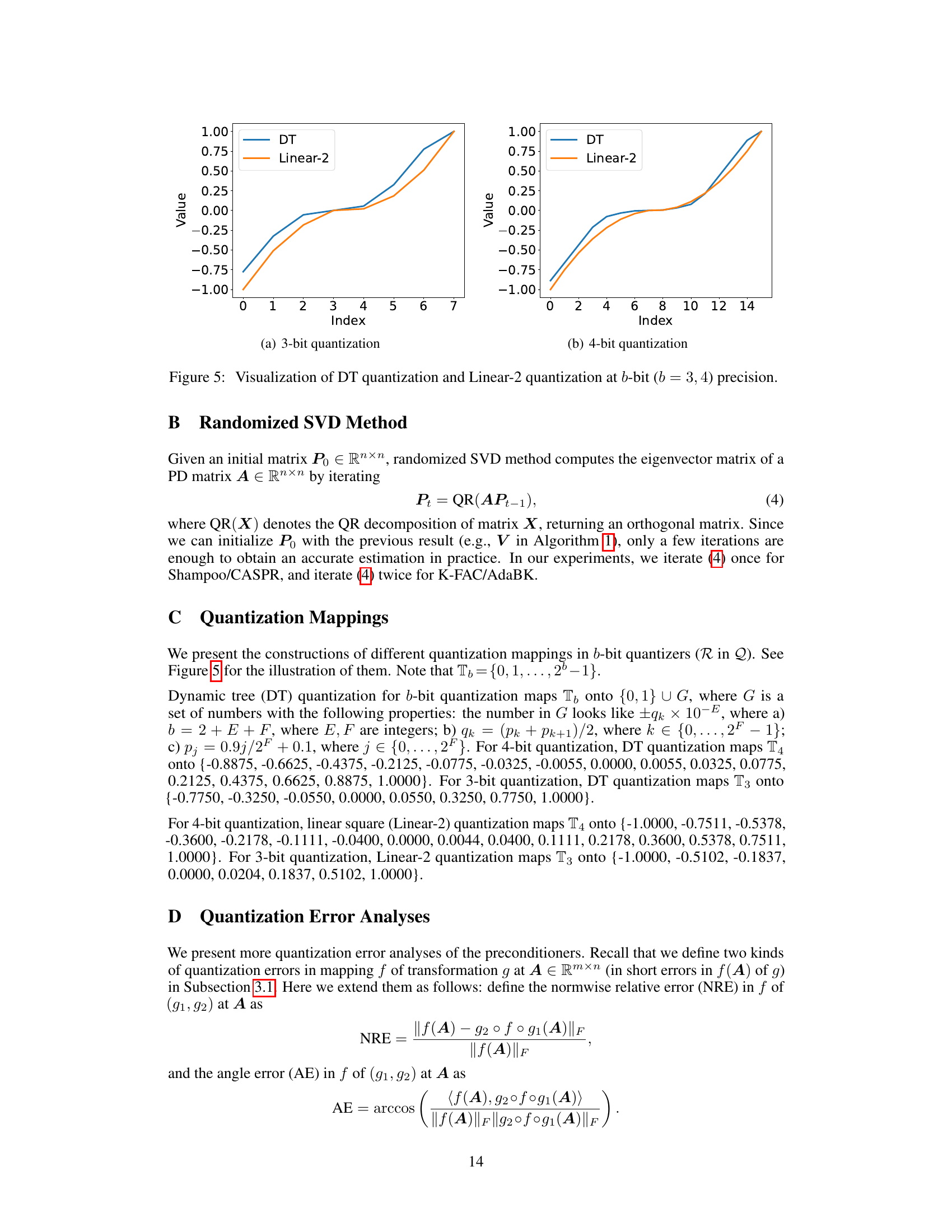

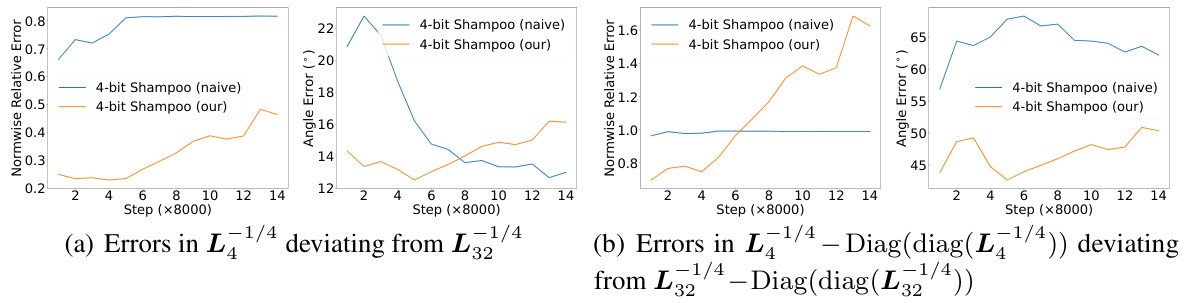

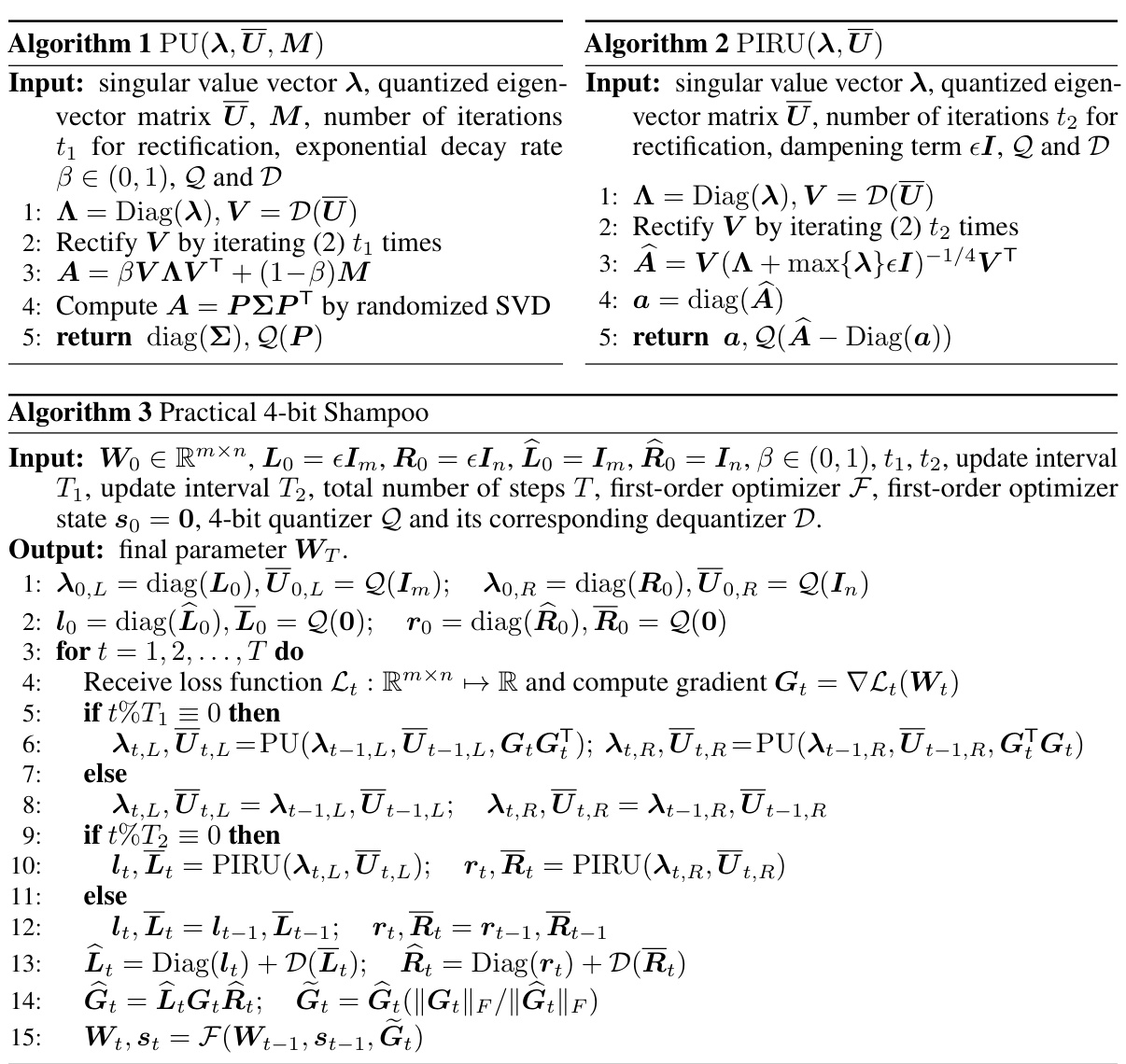

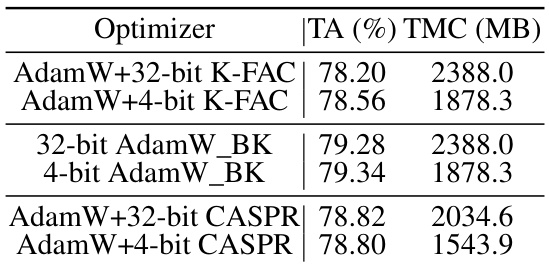

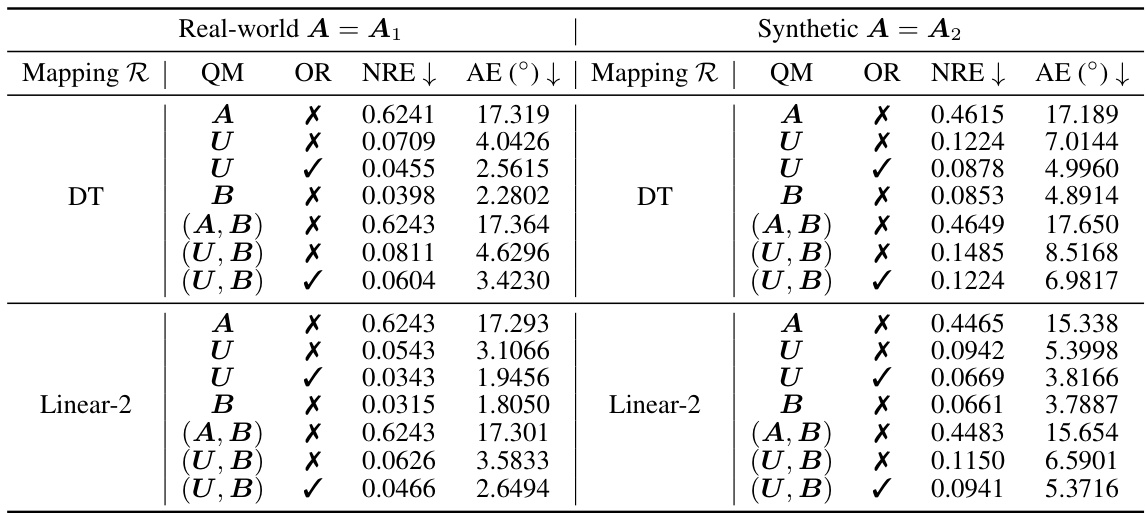

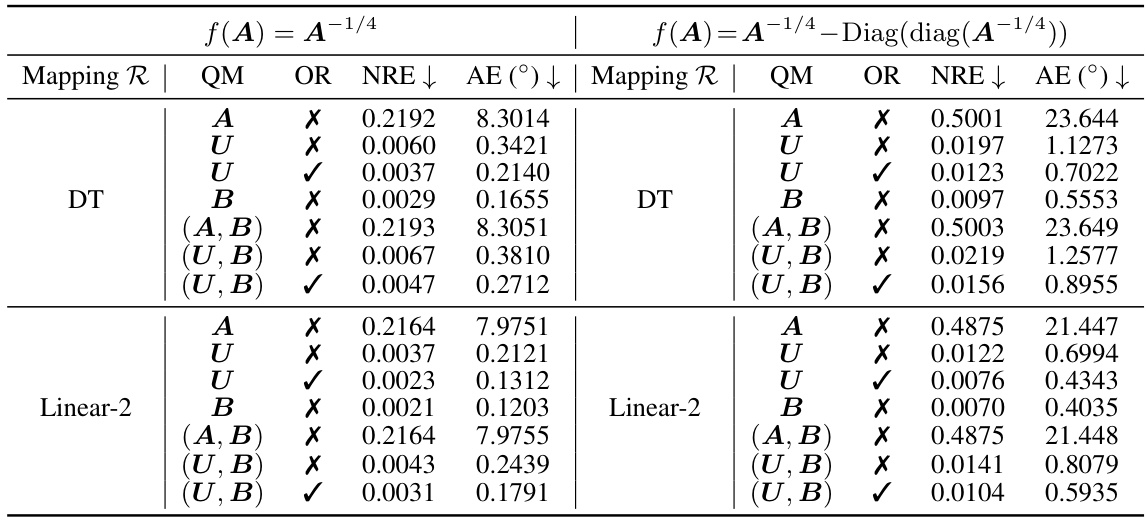

🔼 This table presents a comparison of quantization errors for different methods of quantizing positive definite (PD) matrices and their inverses. It shows the normwise relative error (NRE) and angle error (AE) resulting from quantizing either the full matrix A or its eigenvector matrix U, for both real-world and synthetic data. The results are shown for both 4-bit and 8-bit quantization. Orthogonal rectification (OR) is also evaluated to further improve the accuracy of the quantized inverse.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantization errors in A-1/4 of different quantization schemes at a PD matrix A. We employ block-wise normalization with a block size of 64. U is the eigenvector matrix of A, QM = quantized matrix, and OR = orthogonal rectification.

In-depth insights#

4-bit Shampoo#

The research paper explores memory-efficient network training using a novel 4-bit quantization technique applied to the Shampoo optimizer. The core idea is to compress the 32-bit optimizer states to 4-bits, significantly reducing memory footprint without sacrificing performance. The paper demonstrates that quantizing the eigenvector matrix of the preconditioner, rather than the preconditioner itself, is a more effective approach. This is substantiated by both theoretical analysis and experimental results on various network architectures and datasets. Orthogonal rectification of the quantized eigenvector matrix further enhances performance. Linear square quantization is shown to outperform dynamic tree quantization for this specific application. The 4-bit Shampoo achieves comparable performance to its 32-bit counterpart, enabling the training of larger models with limited memory resources. The findings highlight the potential of low-bit quantization techniques to bridge the gap between efficient first-order and powerful, memory-intensive second-order optimizers for deep learning.

Eigenvector Quantization#

The core idea behind eigenvector quantization in this paper is to compress the optimizer states of second-order optimizers, specifically focusing on Shampoo, for enhanced memory efficiency during neural network training. Instead of quantizing the preconditioner matrix directly, which can lead to substantial information loss, especially concerning smaller singular values, this method proposes quantizing the eigenvector matrix of the preconditioner. This approach is theoretically and experimentally shown to be superior as it better preserves the information crucial for the preconditioner’s inverse 4th root calculation. Quantizing the eigenvectors allows for a more accurate approximation of the preconditioner, even with low bitwidths like 4-bit, resulting in minimal performance degradation compared to the full-precision 32-bit counterpart. This strategy is further enhanced by using Björck orthonormalization to maintain orthogonality in the quantized eigenvector matrix, improving the approximation quality and the efficiency of the inverse root computation. The selection of linear square quantization over dynamic tree quantization, based on observed experimental results, also demonstrates a subtle yet significant improvement in performance. The combination of eigenvector quantization, orthonormalization, and optimized quantization techniques achieves comparable performance to its 32-bit counterpart, but with considerable memory savings.

Orthogonal Rectification#

The concept of “Orthogonal Rectification” in the context of quantized eigenvector matrices within second-order optimization methods addresses a critical challenge: maintaining orthogonality despite quantization errors. Quantization, crucial for memory efficiency, often introduces distortions that disrupt the orthogonality of the eigenvector matrix. This is problematic because many algorithms rely on this property for efficient computation. Orthogonal rectification techniques aim to correct these distortions, bringing the quantized matrix closer to a true orthogonal form. This is achieved through iterative methods, such as Björck orthonormalization, to refine the eigenvector matrix and improve the accuracy of the approximated preconditioner. The effectiveness of orthogonal rectification hinges on the balance between computational cost and accuracy gains. While iterative refinement improves orthogonality, each iteration adds complexity. Therefore, determining the optimal number of iterations is crucial for balancing the benefits of improved orthogonality against increased computational burden, ultimately impacting performance and training efficiency. The choice of rectification method also depends on the type of quantization used, meaning that the optimal rectification strategy is highly contextual.

Quantization Methods#

This paper delves into the crucial aspect of memory-efficient network training through quantization methods. The authors meticulously explore different quantization techniques, focusing on their application to second-order optimizers, which are known for their computational cost. The core contribution is the introduction of a novel 4-bit Shampoo optimizer. While the concept of quantizing optimizer states is not new, applying this technique to second-order methods is a significant advancement. The paper provides a rigorous theoretical analysis comparing direct preconditioner quantization and eigenvector matrix quantization, showing that the latter approach is superior. Experimental results demonstrate that the 4-bit Shampoo optimizer outperforms naive quantization methods, while maintaining comparable performance to its 32-bit counterpart. This improvement is attributed to algorithmic improvements that address the orthogonality issues arising from quantization. The study also investigates various quantization schemes, including dynamic tree and linear square quantization, ultimately recommending linear square quantization for improved accuracy.

Memory Efficiency#

The research paper explores memory-efficient network training, focusing on the memory overhead associated with second-order optimizers. A key challenge addressed is the large memory footprint of the preconditioner and its inverse root, commonly used in such optimizers. The paper introduces 4-bit Shampoo, a novel technique that significantly reduces memory usage by quantizing optimizer states. This involves quantizing the eigenvector matrix of the preconditioner rather than the preconditioner itself which is theoretically and experimentally shown to be superior. Quantization is a crucial aspect of achieving memory efficiency, with linear square quantization slightly outperforming dynamic tree quantization. The approach demonstrates comparable performance to 32-bit counterparts while reducing memory significantly. This highlights the potential of low-bit quantization for enabling the training of larger models with limited resources. Furthermore, the study investigates the impact of different quantization methods on accuracy, comparing the proposed method with alternative techniques and demonstrating its effectiveness. The overall conclusion emphasizes the significant memory efficiency gains without compromising performance, paving the way for more resource-efficient deep learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

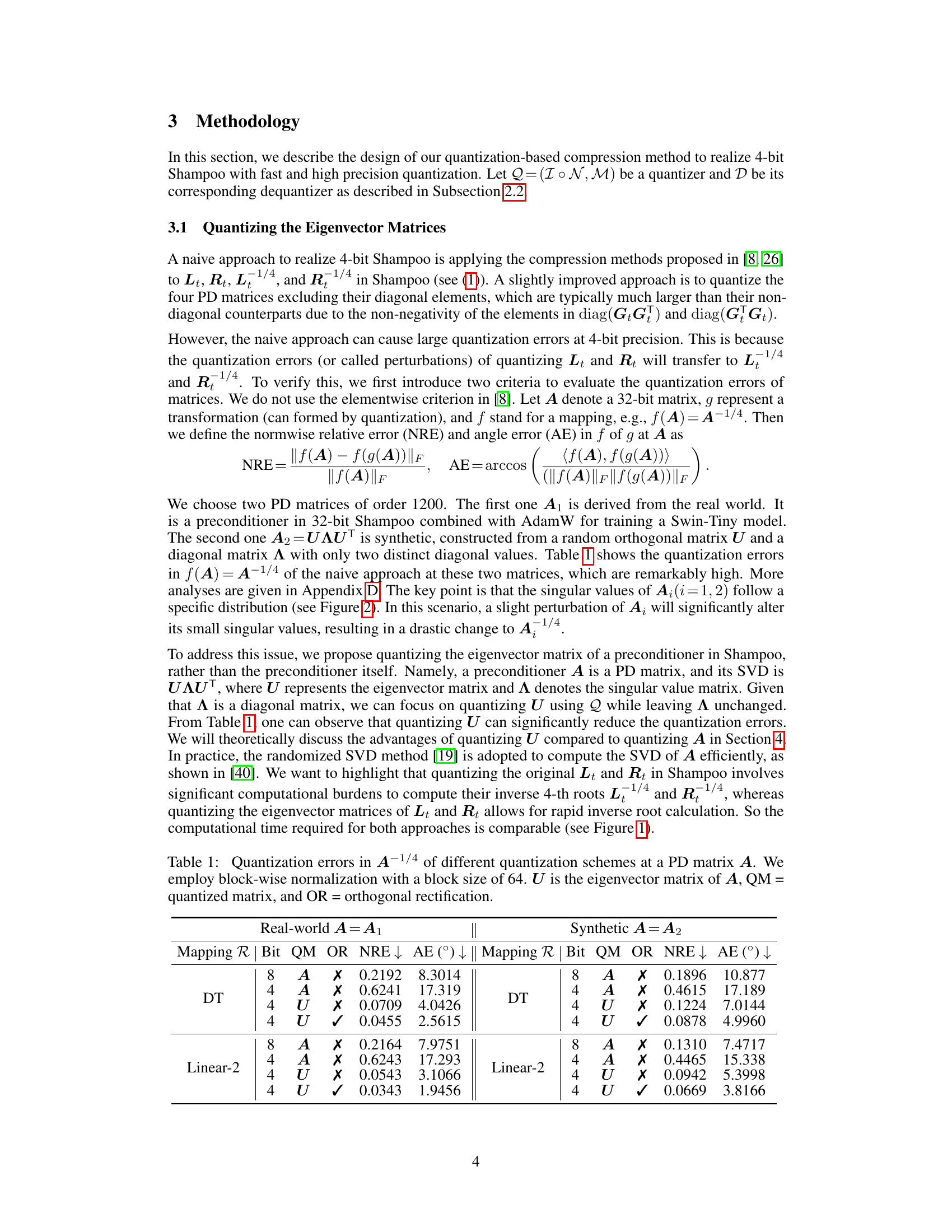

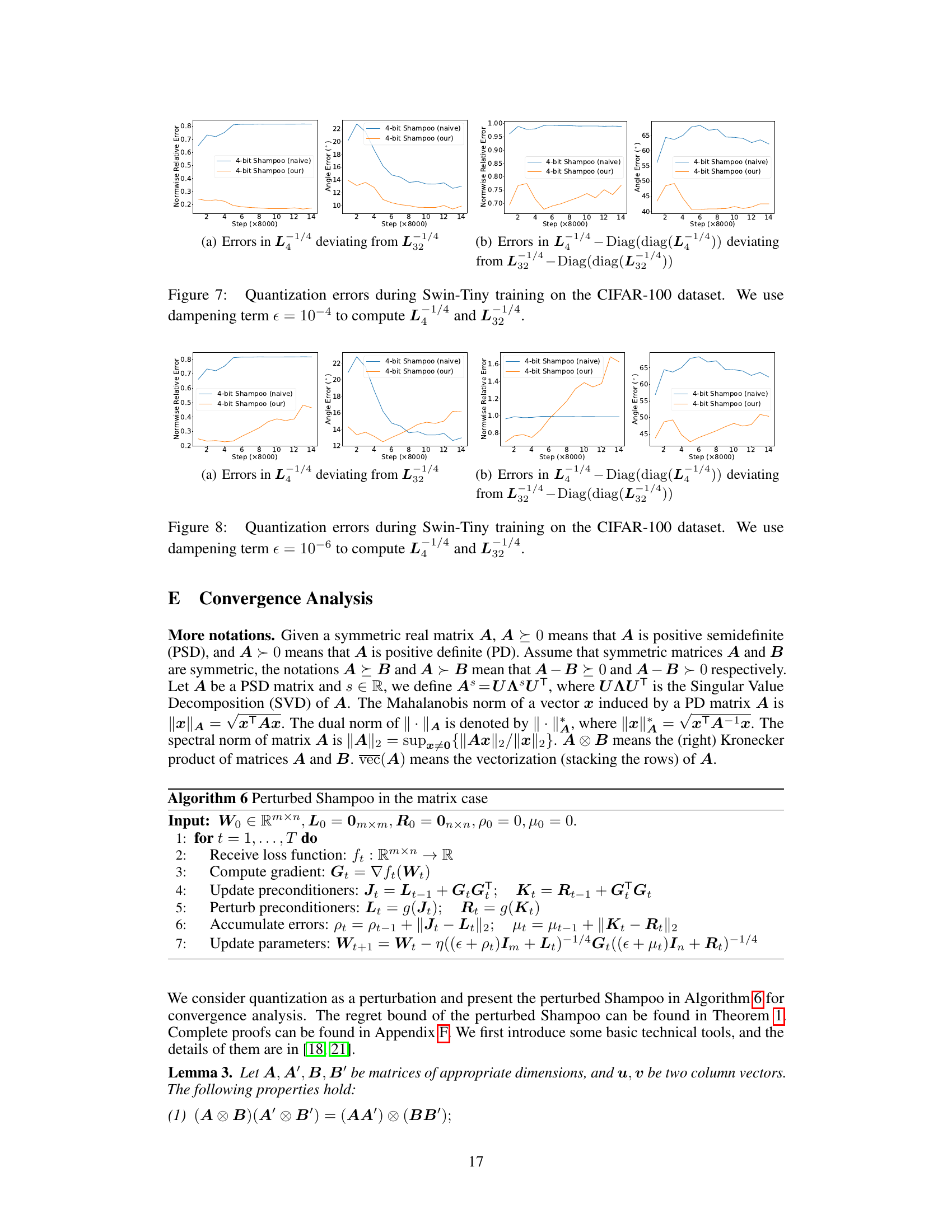

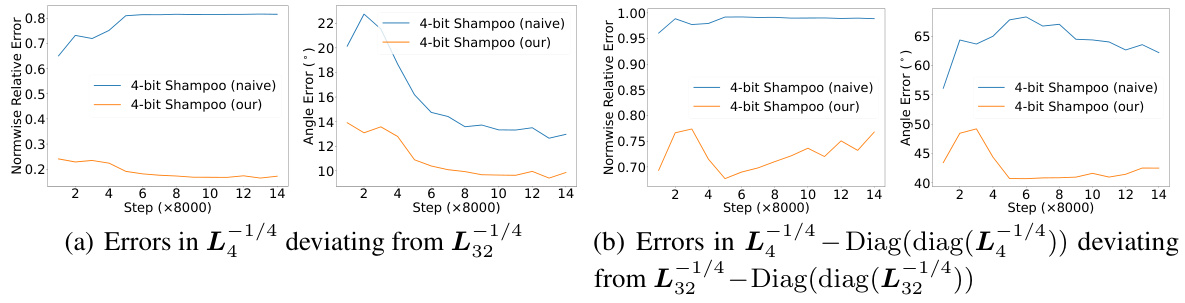

🔼 This figure visualizes the singular value distributions of two positive definite (PD) matrices, one from real-world data (preconditioner from 32-bit Shampoo) and one synthetic. It compares the distributions of the original 32-bit matrices to their 4-bit quantized counterparts (using dynamic tree (DT) quantization and quantizing the matrix itself). The y-axis shows singular values on a logarithmic scale, highlighting how the quantization process affects the smaller singular values more drastically.

read the caption

Figure 2: Singular value distributions of PD matrices (real) and their 4-bit compressions (quan) used in Table 1 with R=DT, QM=A. Singular values are shown on a log10 scale.

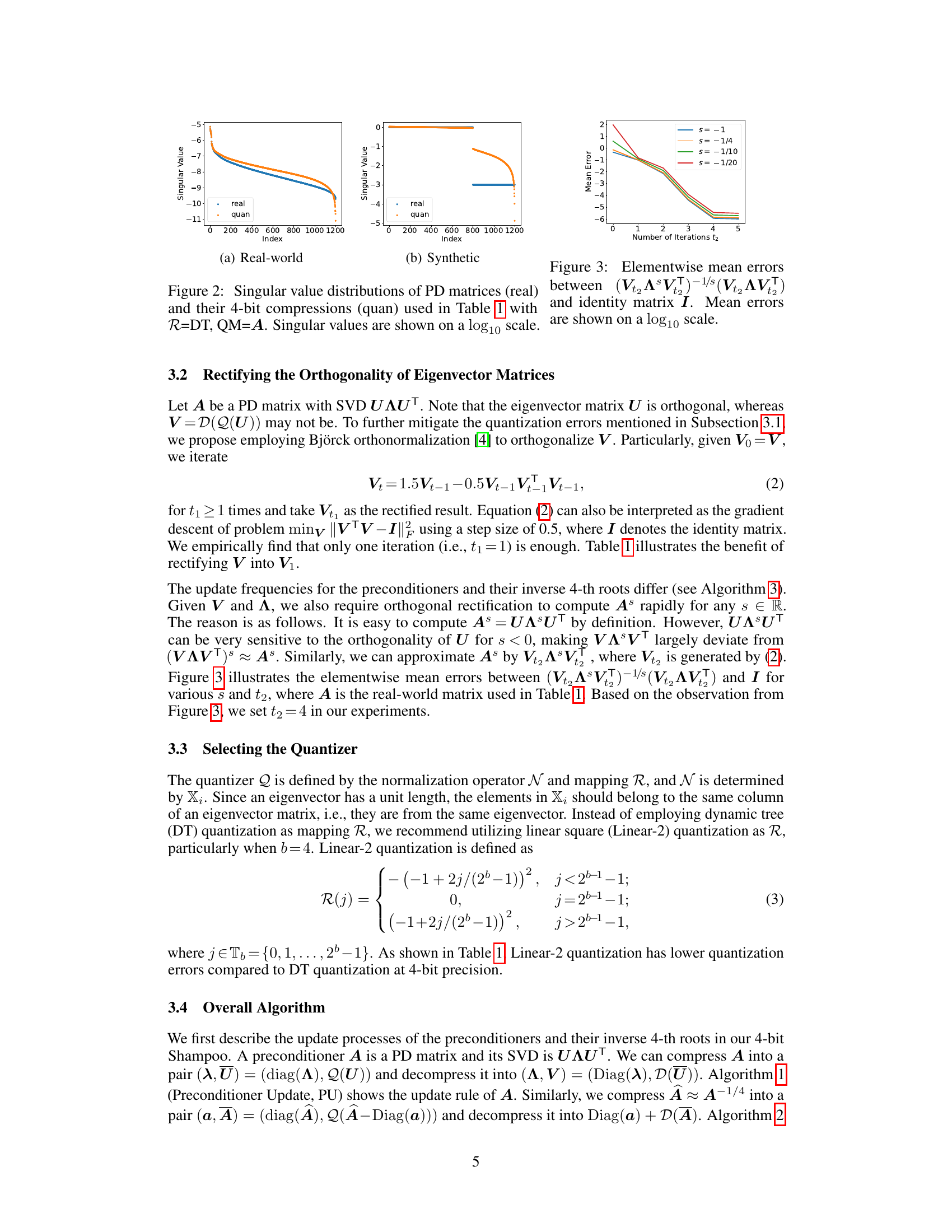

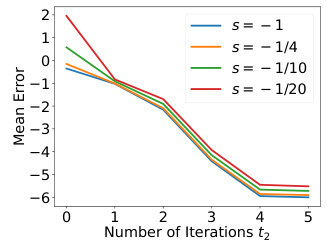

🔼 This figure visualizes the element-wise mean errors between the result of applying the power operation (with exponent -s) to a matrix (VAVT) and its s-th power, and the identity matrix. The graph plots these mean errors on a logarithmic scale (base 10), showing the error’s behavior across various number of Björck orthonormalization iterations (t2). Different lines on the graph represent different values of ’s’ (-1, -1/4, -1/10, -1/20), showcasing how these values affect the errors during the orthonormalization process.

read the caption

Figure 3: Elementwise mean errors between (VAVT)−s(VAVT)s and identity matrix I. Mean errors are shown on a log10 scale.

🔼 This figure visualizes the test accuracy and GPU memory consumption for vision transformer models. Two versions of 4-bit Shampoo are compared: a naive approach that quantizes the entire preconditioner, and the authors’ proposed method that quantizes only the eigenvector matrix. The results show the impact of each quantization approach on model performance and memory efficiency, comparing them to the results of training with 32-bit Shampoo and AdamW.

read the caption

Figure 1: Visualization of test accuracies and total GPU memory costs of vision transformers. 4-bit Shampoo (naive) quantizes the preconditioner, while 4-bit Shampoo (our) quantizes its eigenvector matrix.

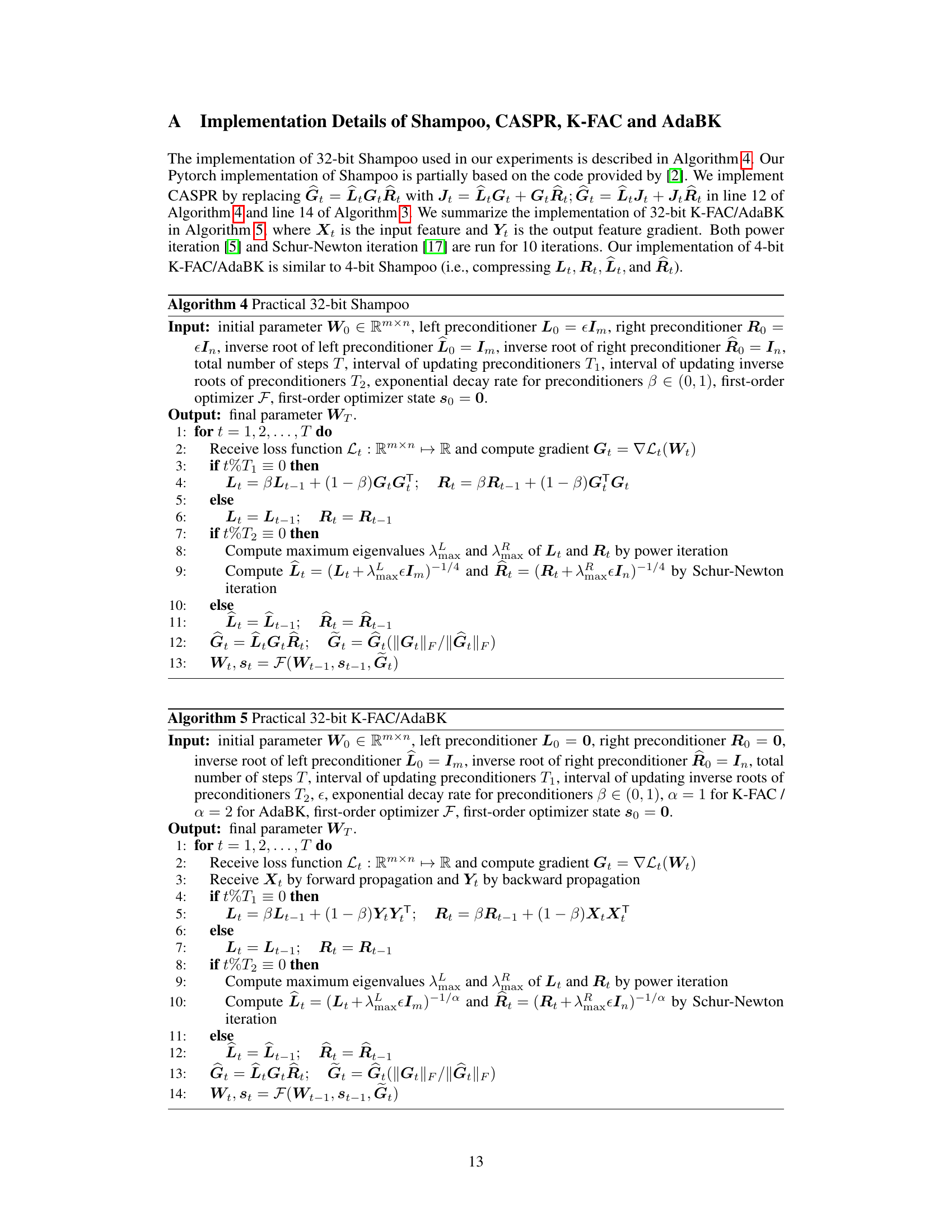

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of two quantization methods, DT and Linear-2, at both 3-bit and 4-bit precisions. Each graph plots the quantized value against the index. The purpose is to visually demonstrate the difference in how these two methods map input values to discrete levels within the limited bit-depth. This directly relates to the quantization error and impact on model performance discussed in the paper, where the Linear-2 method is shown to be superior in many cases.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visualization of DT quantization and Linear-2 quantization at b-bit (b = 3, 4) precision.

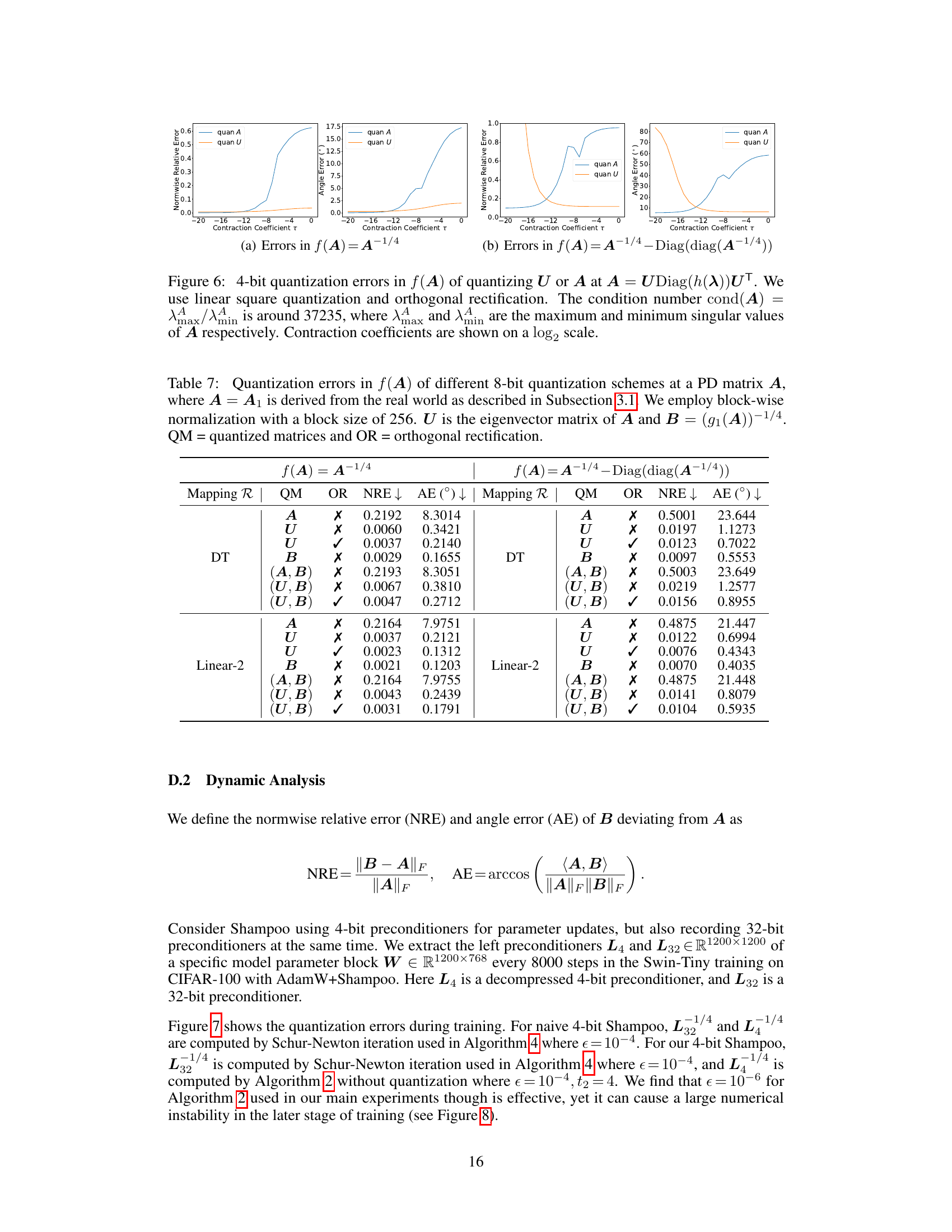

🔼 This figure visualizes the impact of quantizing either the eigenvector matrix (U) or the preconditioner matrix (A) on the resulting quantization errors. The errors are measured using two metrics: normwise relative error and angle error, for both A-1/4 and A-1/4 - Diag(diag(A-1/4)). The x-axis represents the contraction coefficient (τ), which modifies the singular value distribution of A. The results demonstrate that quantizing the eigenvector matrix (U) leads to significantly lower quantization errors compared to quantizing the preconditioner matrix (A) itself, particularly for smaller singular values which greatly influence the A-1/4 computation. This validates the approach of quantizing U over A in 4-bit Shampoo.

read the caption

Figure 6: 4-bit quantization errors in f(A) of quantizing U or A at A = UDiag(h(A))UT. We use linear square quantization and orthogonal rectification. The condition number cond(A) = Amax/Amin is around 37235, where Amax and Amin are the maximum and minimum singular values of A respectively. Contraction coefficients are shown on a log2 scale.

🔼 This figure visualizes the test accuracy and GPU memory consumption for vision transformers using different optimization methods. Two versions of 4-bit Shampoo are compared: a naive approach that quantizes the preconditioner directly and the proposed method that quantizes the eigenvector matrix. The results are shown for two different vision transformer models trained on two different datasets (CIFAR-100 and ImageNet-1k). The figure highlights that the proposed 4-bit Shampoo approach achieves comparable accuracy to the 32-bit Shampoo while significantly reducing memory consumption.

read the caption

Figure 1: Visualization of test accuracies and total GPU memory costs of vision transformers. 4-bit Shampoo (naive) quantizes the preconditioner, while 4-bit Shampoo (our) quantizes its eigenvector matrix.

🔼 The figure visualizes the performance of different optimizers on two vision transformer models: Swin-Tiny on CIFAR-100 and ViT-Base/32 on ImageNet-1k. It compares the test accuracy and GPU memory usage of AdamW, AdamW+32-bit Shampoo, and two versions of AdamW+4-bit Shampoo. One 4-bit Shampoo version naively quantizes the preconditioner, while the other (the authors’ method) quantizes the eigenvector matrix. The results show that the authors’ 4-bit Shampoo achieves comparable accuracy to the 32-bit version while significantly reducing memory consumption.

read the caption

Figure 1: Visualization of test accuracies and total GPU memory costs of vision transformers. 4-bit Shampoo (naive) quantizes the preconditioner, while 4-bit Shampoo (our) quantizes its eigenvector matrix.

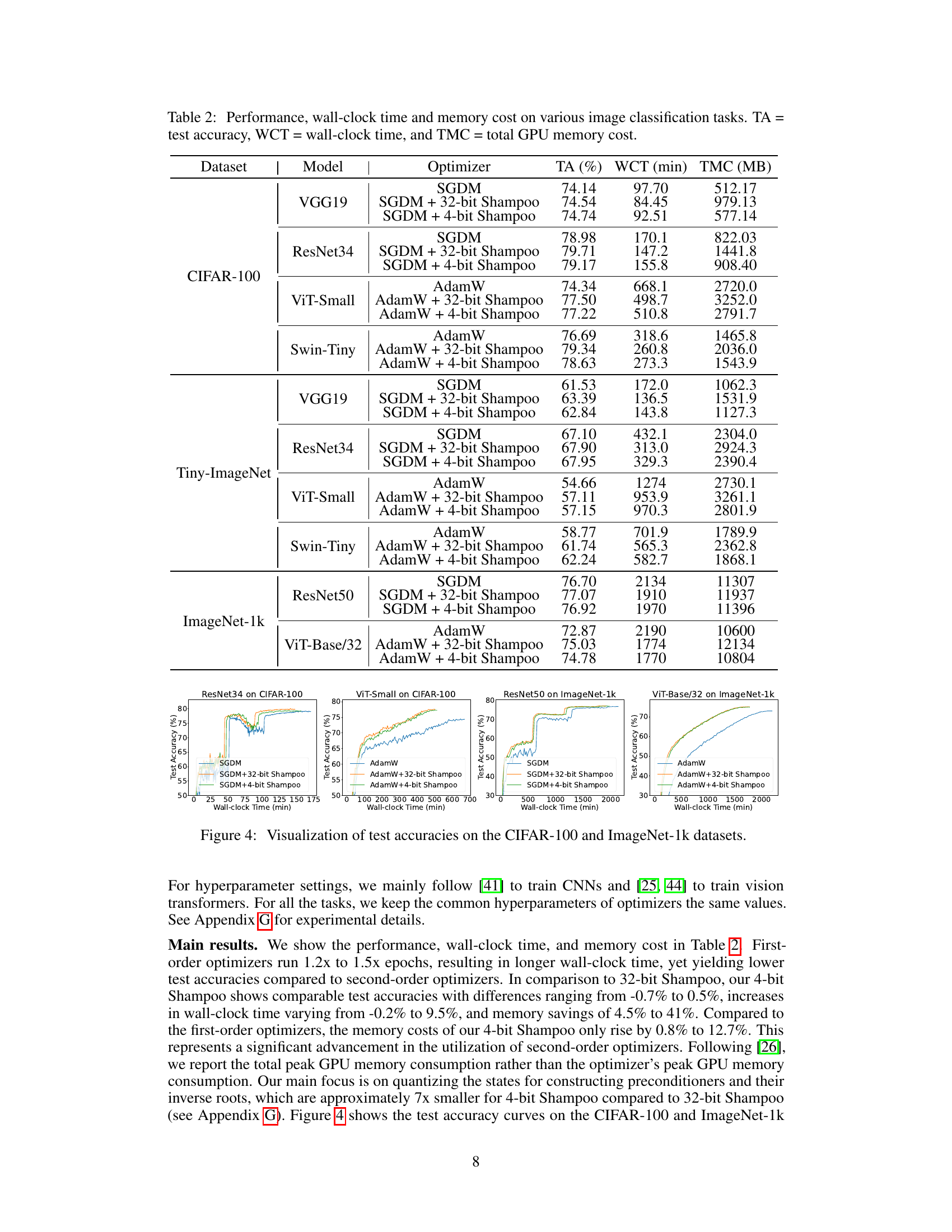

🔼 This figure visualizes the test accuracy over training time (epochs) for different models and optimizers on the CIFAR-100 and ImageNet-1k datasets. It compares the performance of standard optimizers (SGDM, AdamW) against their counterparts combined with 32-bit and 4-bit Shampoo. The plots show that the 4-bit Shampoo versions maintain comparable performance to the 32-bit versions, often converging at a similar or slightly slower rate while offering significant memory savings.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization of test accuracies on the CIFAR-100 and ImageNet-1k datasets.

🔼 This figure visualizes the performance of different optimizers on two vision transformer models: Swin-Tiny on CIFAR-100 and ViT-Base/32 on ImageNet-1k. It compares the test accuracy and GPU memory usage of AdamW, AdamW + 32-bit Shampoo, AdamW + a naive 4-bit Shampoo (quantizing the preconditioner), and AdamW + the proposed 4-bit Shampoo (quantizing the eigenvector matrix). The results show that the proposed 4-bit Shampoo achieves comparable accuracy to the 32-bit version while significantly reducing memory consumption.

read the caption

Figure 1: Visualization of test accuracies and total GPU memory costs of vision transformers. 4-bit Shampoo (naive) quantizes the preconditioner, while 4-bit Shampoo (our) quantizes its eigenvector matrix.

More on tables

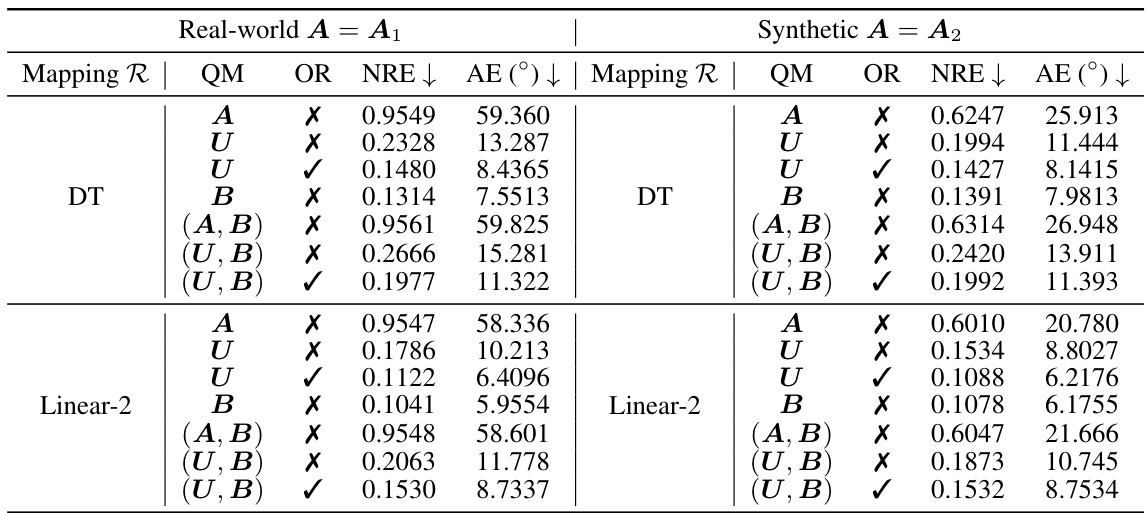

🔼 This table compares the test accuracy and total GPU memory cost of training the Swin-Tiny model on the CIFAR-100 dataset using different optimizers. It specifically shows the performance of 32-bit and 4-bit versions of AdamW combined with K-FAC, AdaBK, and CASPR, highlighting the memory efficiency achieved by the 4-bit versions.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance and memory cost of training Swin-Tiny on CIFAR-100. TA = test accuracy and TMC = total GPU memory cost.

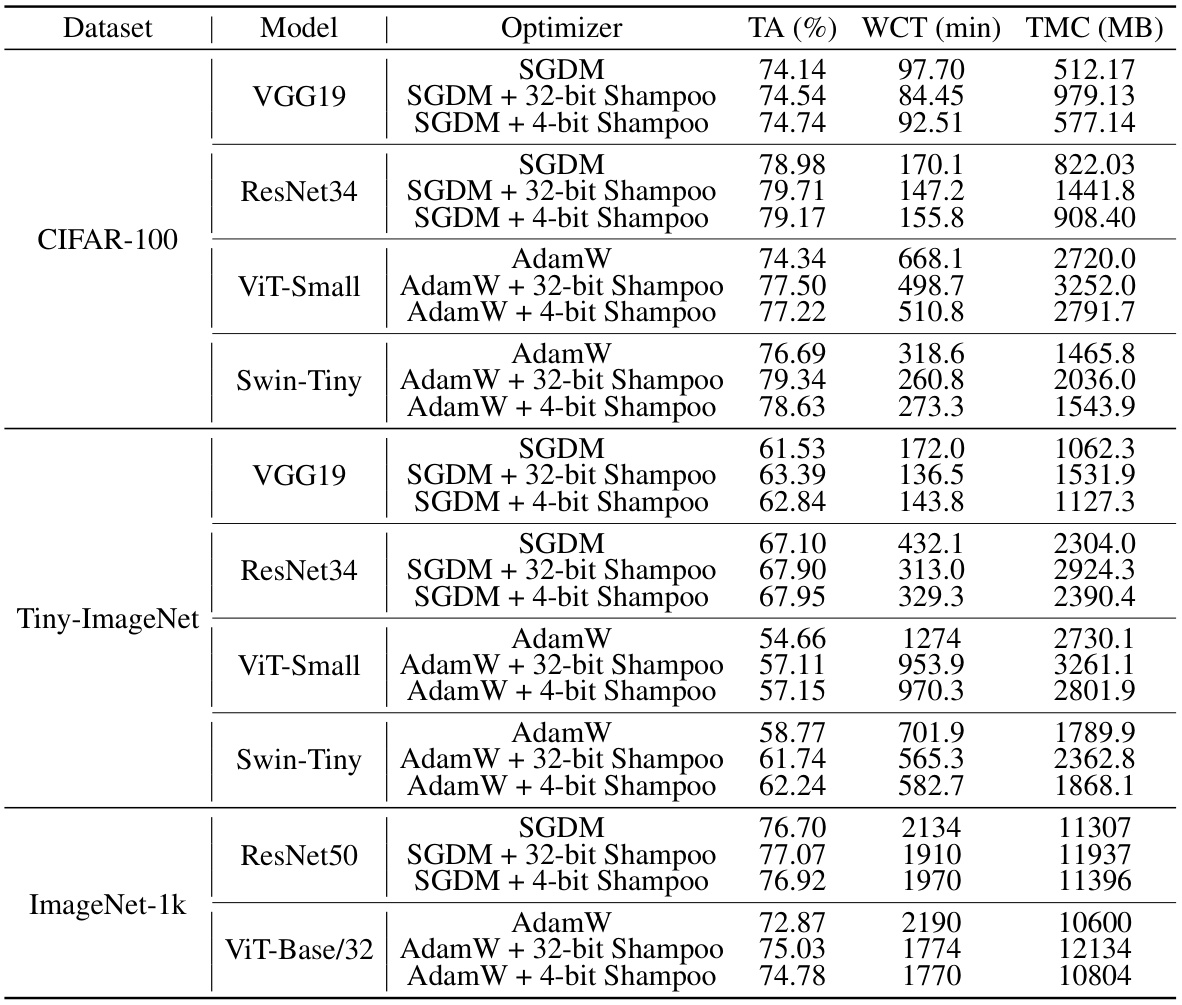

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments using various models (VGG19, ResNet34, ViT-Small, Swin-Tiny, ResNet50, ViT-Base/32) and optimizers (SGDM, AdamW, and their 4-bit Shampoo counterparts) on three datasets (CIFAR-100, Tiny-ImageNet, ImageNet-1k). For each combination, it reports the test accuracy (TA), wall-clock time (WCT), and total GPU memory cost (TMC). It allows for comparing the performance, speed, and memory efficiency of different optimizers, including the impact of 4-bit quantization.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance, wall-clock time and memory cost on various image classification tasks. TA = test accuracy, WCT = wall-clock time, and TMC = total GPU memory cost.

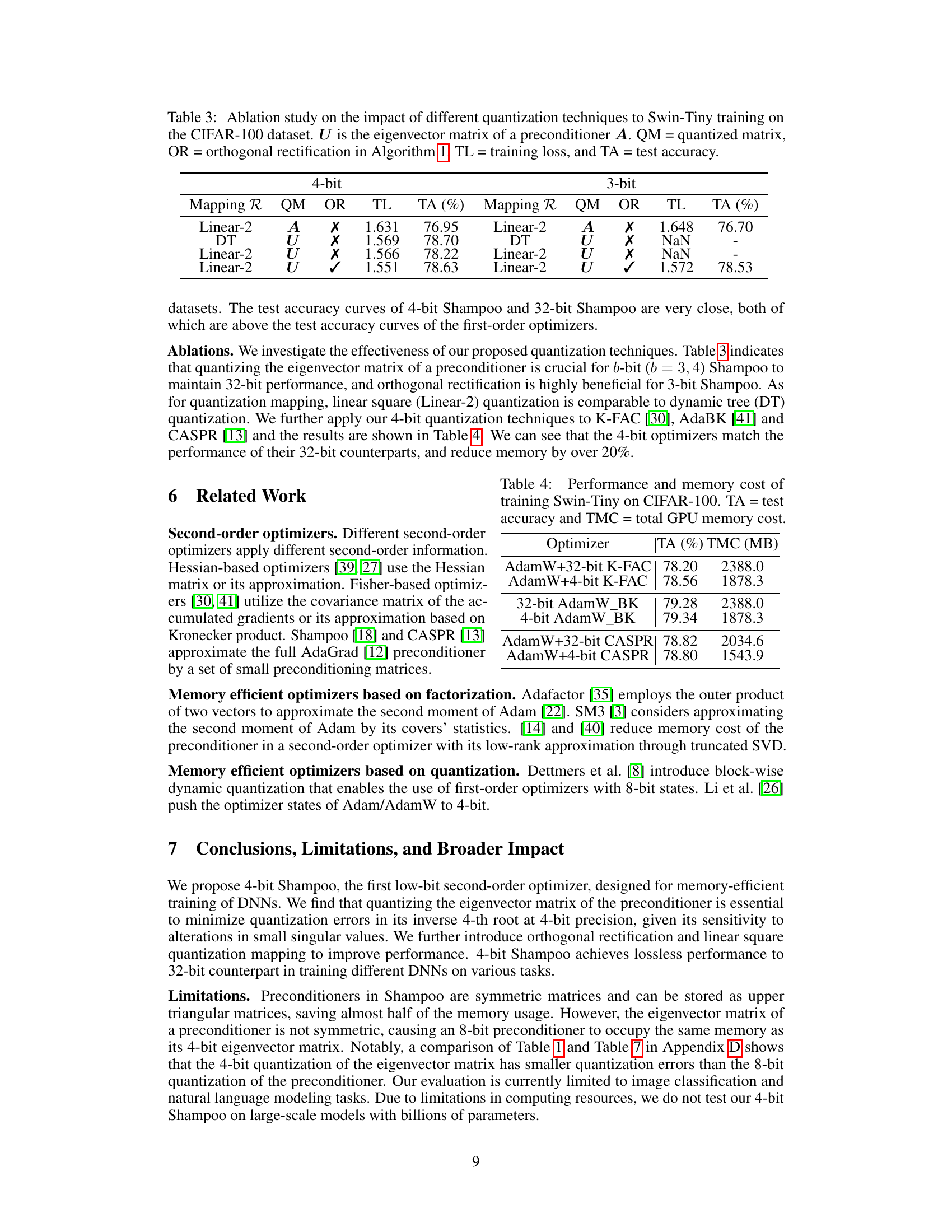

🔼 This table presents an ablation study evaluating the effect of different quantization techniques on the performance of Swin-Tiny model training using the CIFAR-100 dataset. It compares the impact of quantizing the entire preconditioner matrix (A) versus only its eigenvector matrix (U), with and without orthogonal rectification (OR). The results show training loss (TL) and test accuracy (TA) for both 4-bit and 3-bit quantization using different mapping methods (Linear-2 and DT).

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study on the impact of different quantization techniques to Swin-Tiny training on the CIFAR-100 dataset. U is the eigenvector matrix of a preconditioner A. QM = quantized matrix, OR = orthogonal rectification in Algorithm 1, TL = training loss, and TA = test accuracy.

🔼 This table compares the test accuracy (TA) and total GPU memory cost (TMC) of training the Swin-Tiny model on the CIFAR-100 dataset using different optimizers. It shows the results for AdamW with 32-bit and 4-bit K-FAC, AdamW with 32-bit and 4-bit AdaBK, and AdamW with 32-bit and 4-bit CASPR. The comparison highlights the memory efficiency achieved by using 4-bit optimizers while maintaining comparable performance to their 32-bit counterparts.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance and memory cost of training Swin-Tiny on CIFAR-100. TA = test accuracy and TMC = total GPU memory cost.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of quantization errors for different methods of quantizing positive definite (PD) matrices. It shows the normwise relative error (NRE) and angle error (AE) when using different quantization methods (DT, Linear-2) on both the original matrix (A) and its eigenvector matrix (U). Results are shown for 4-bit and 8-bit quantization, with and without orthogonal rectification (OR). The goal is to evaluate which method minimizes errors when reducing the memory footprint of second-order optimizer states.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantization errors in A-1/4 of different quantization schemes at a PD matrix A. We employ block-wise normalization with a block size of 64. U is the eigenvector matrix of A, QM = quantized matrix, and OR = orthogonal rectification.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of quantization errors for different methods of quantizing a positive definite (PD) matrix and its eigenvector matrix. The errors are evaluated using two metrics: normwise relative error (NRE) and angle error (AE). Different quantization mappings (DT and Linear-2) and bit depths (4 and 8 bits) are compared. The results show that quantizing the eigenvector matrix (U) generally produces significantly lower errors compared to directly quantizing the PD matrix (A). Orthogonal rectification (OR) further improves the results.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantization errors in A-1/4 of different quantization schemes at a PD matrix A. We employ block-wise normalization with a block size of 64. U is the eigenvector matrix of A, QM = quantized matrix, and OR = orthogonal rectification.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of quantization errors for different methods applied to a positive definite (PD) matrix A. The goal is to approximate the inverse fourth root of A (A⁻¹/⁴) using different quantization techniques with varying bit precision and normalization schemes. The table evaluates the normwise relative error (NRE) and angle error (AE) for different quantization approaches, including quantizing the entire matrix A, its eigenvector matrix U, or combinations of both. The results are shown for both a real-world matrix and a synthetic matrix. It highlights the impact of quantizing eigenvectors versus quantizing the full matrix. Orthogonal rectification is also tested to see its effect on reducing errors.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantization errors in A-1/4 of different quantization schemes at a PD matrix A. We employ block-wise normalization with a block size of 64. U is the eigenvector matrix of A, QM = quantized matrix, and OR = orthogonal rectification.

🔼 This table presents the test accuracy (TA) and total GPU memory cost (TMC) for training the Swin-Tiny model on the CIFAR-100 dataset using different optimizers. It compares the performance of AdamW with 32-bit and 4-bit versions of K-FAC, AdaBK, and CASPR, highlighting the memory efficiency gains achieved by using 4-bit quantization.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance and memory cost of training Swin-Tiny on CIFAR-100. TA = test accuracy and TMC = total GPU memory cost.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance (test accuracy) and training time (wall-clock time) for training the ResNet34 model on the CIFAR-100 dataset using different optimizers. The optimizers compared include SGDM (Stochastic Gradient Descent with Momentum) with varying numbers of epochs, SGDM combined with 32-bit Shampoo, and SGDM combined with the proposed 4-bit Shampoo. The results showcase the impact of the different optimizers and the number of training epochs on both accuracy and training efficiency.

read the caption

Table 8: Performance and wall-clock time of training ResNet34 on the CIFAR-100 dataset with cosine learning rate decay. TA = test accuracy, and WCT = wall-clock time.

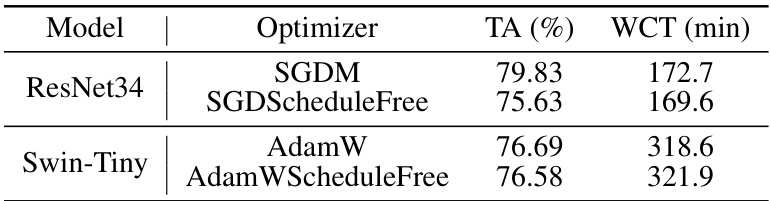

🔼 This table compares the test accuracy (TA) and wall-clock time (WCT) of training ResNet34 and Swin-Tiny models on the CIFAR-100 dataset using different optimizers. The optimizers compared are standard SGDM and AdamW, as well as versions employing schedule-free optimization techniques (SGDScheduleFree and AdamWScheduleFree). The results highlight the performance differences between these optimizers under the cosine learning rate decay schedule.

read the caption

Table 9: Performance and wall-clock time of training on the CIFAR-100 dataset with cosine learning rate decay and schedule-free approach. ResNet34 is trained for 300 epochs and Swin-Tiny is trained for 150 epochs. TA = test accuracy, and WCT = wall-clock time.

🔼 This table presents the test accuracy (TA), wall-clock time (WCT), and total GPU memory cost (TMC) for training the Swin-Tiny model on the CIFAR-100 dataset using different optimizers: NadamW, AdamW + 32-bit Shampoo, AdamW + 4-bit Shampoo (the proposed method), Adagrad, Adagrad + 32-bit Shampoo, and Adagrad + 4-bit Shampoo. It compares the performance and resource usage of different optimizers, highlighting the efficiency gains achieved by the 4-bit Shampoo.

read the caption

Table 10: Performance, wall-clock time, and memory cost of training Swin-Tiny on the CIFAR-100 dataset. TA = test accuracy, WCT = wall-clock time, and TMC = total GPU memory cost.

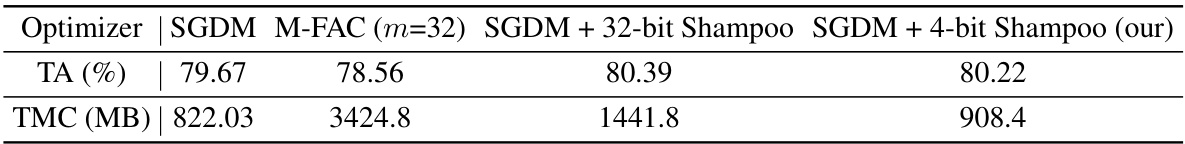

🔼 This table shows the test accuracy (TA) and total GPU memory cost (TMC) of training ResNet34 on the CIFAR-100 dataset using different optimizers for 200 epochs. The optimizers compared are SGDM, M-FAC (m=32), SGDM + 32-bit Shampoo, and SGDM + 4-bit Shampoo (our). The table highlights the memory efficiency of the proposed 4-bit Shampoo.

read the caption

Table 11: Performance and memory cost of training ResNet34 on the CIFAR-100 dataset with cosine learning rate decay. All the optimizers are run for 200 epochs. TA = test accuracy, and TMC = total GPU memory cost.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different optimizers on natural language modeling tasks using LLAMA-130M and LLAMA-350M models on the C4 dataset and GPT2-124M on the OWT dataset. The metrics reported are validation loss (VL), wall-clock time (WCT), and total GPU memory cost (TMC). The table compares the performance of AdamW with 32-bit and 4-bit versions of Shampoo, including a naive 4-bit implementation and the authors’ improved 4-bit implementation.

read the caption

Table 12: Performance, wall-clock time, and memory usage per GPU on natural language modeling tasks. VL = validation loss, WCT = wall-clock time, and TMC = total GPU memory cost.

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating memory efficiency when training the large language model LLAMA2-7B using different optimizers. The experiment varied the batch size used in training and measured the total GPU memory consumption. The table compares the memory usage of 8-bit AdamW, 8-bit AdamW with 32-bit Shampoo, and 8-bit AdamW with 4-bit Shampoo (both the naive and improved versions from the paper). The results show that the 4-bit Shampoo significantly reduces memory consumption compared to the 32-bit version, enabling training with larger batch sizes.

read the caption

Table 13: Memory cost of training LLAMA2-7B on the C4 dataset with different optimizers. One A800 GPU with a maximum memory of 81,920 MB is enabled. TMC = total GPU memory cost, and OOM = out of memory.

Full paper#