TL;DR#

Video text spotting (VTS), a challenging task involving both text detection and recognition, currently suffers from suboptimal recognition capabilities. Existing end-to-end methods, attempting to optimize multiple tasks simultaneously, often compromise on individual task performance. This paper identifies this recognition limitation as a major bottleneck in VTS.

GoMatching, a novel approach, tackles this by effectively utilizing an off-the-shelf image text spotter and focusing training on enhancing the tracking aspect. It introduces a rescoring mechanism to improve the confidence of detected instances and a Long-Short Term Matching (LST-Matcher) module to enhance tracking through effective integration of long- and short-term matching information. This simplified yet powerful approach results in superior performance and efficiency on benchmark datasets, including a newly proposed ArTVideo dataset containing curved texts.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses a critical bottleneck in video text spotting—weak recognition capabilities—by proposing a simple yet effective baseline, GoMatching. This innovative approach shifts the focus to robust tracking while leveraging off-the-shelf image text spotters, substantially reducing training costs. It introduces novel methodologies that improve accuracy and efficiency for various text scenarios, including curved texts, thus impacting the field’s efficiency and pushing research forward in video text spotting.

Visual Insights#

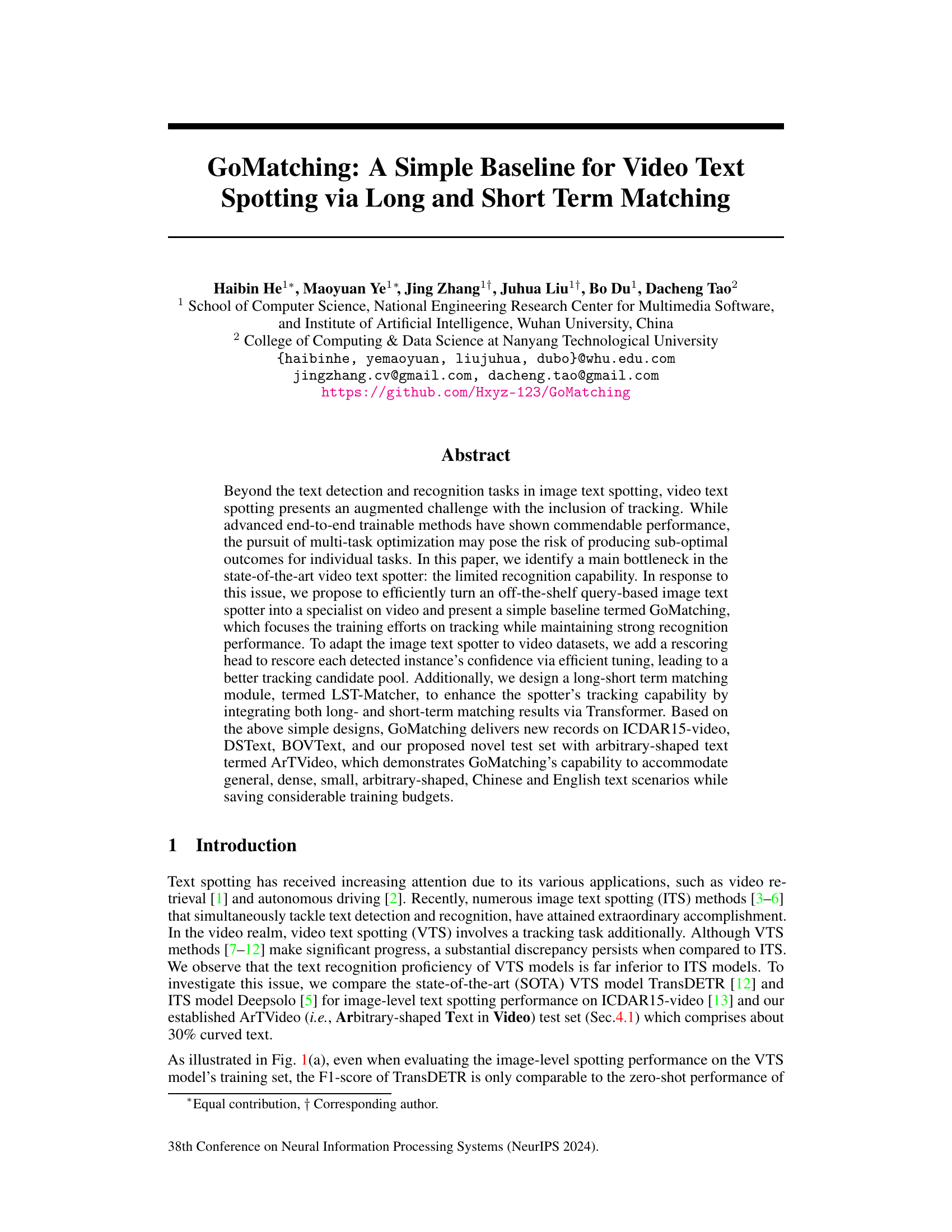

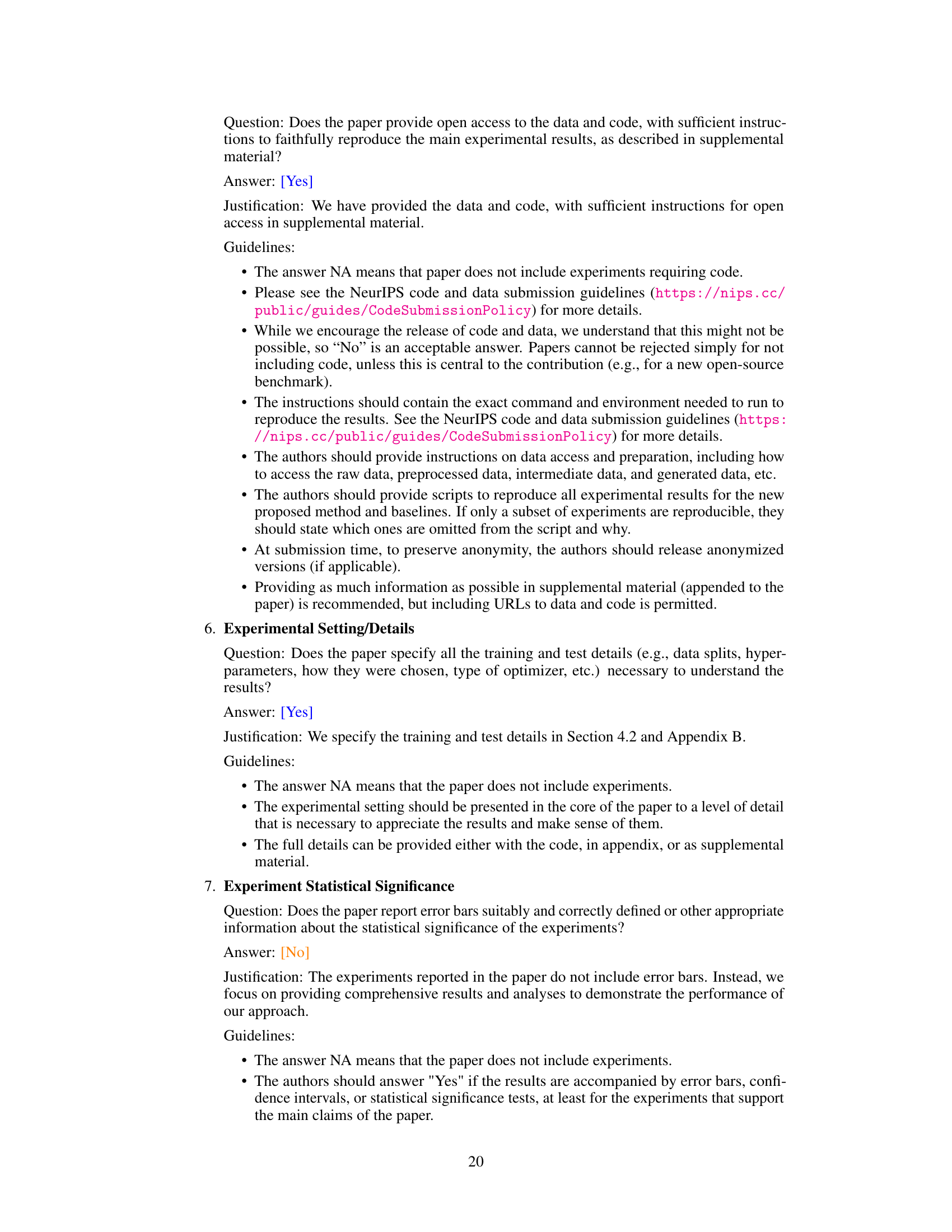

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of the performance of GoMatching and TransDETR on two video text spotting datasets: ICDAR15-video and ArTVideo. Subfigure (a) presents bar charts comparing image-level spotting F1-scores and the gap between spotting and detection F1-scores for both a state-of-the-art Video Text Spotter (VTS) model (TransDETR) and a state-of-the-art Image Text Spotter (ITS) model (Deepsolo) to highlight that the main limitation of current VTS methods is poor recognition. Subfigure (b) shows a comparison of the MOTA scores, GPU memory usage, and GPU training time for GoMatching and TransDETR on the ICDAR15-video dataset. GoMatching shows significant performance improvements with substantially reduced computational costs.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) 'Gap between Spot. & Det.': the gap between spotting and detection F1-score. As the spotting task involves recognizing the results of the detection process, the detection score is indeed the upper bound of spotting performance. The larger the gap, the poorer the recognition ability. Compared to the ITS model (Deepsolo [5]), the VTS model (TransDETR [12]) presents unsatisfactory image-level text spotting F1-scores, which lag far behind its detection performance, especially on ArTVideo with curved text. It indicates recognition capability is a main bottleneck in the VTS model. (b) GoMatching outperforms TransDETR by over 12 MOTA on ICDAR15-video while saving 197 training GPU hours and 10.8GB memory. Notice that since the pre-training strategies and settings vary between TransDETR and GoMatching, the comparison is focused on the fine-tuning stage.

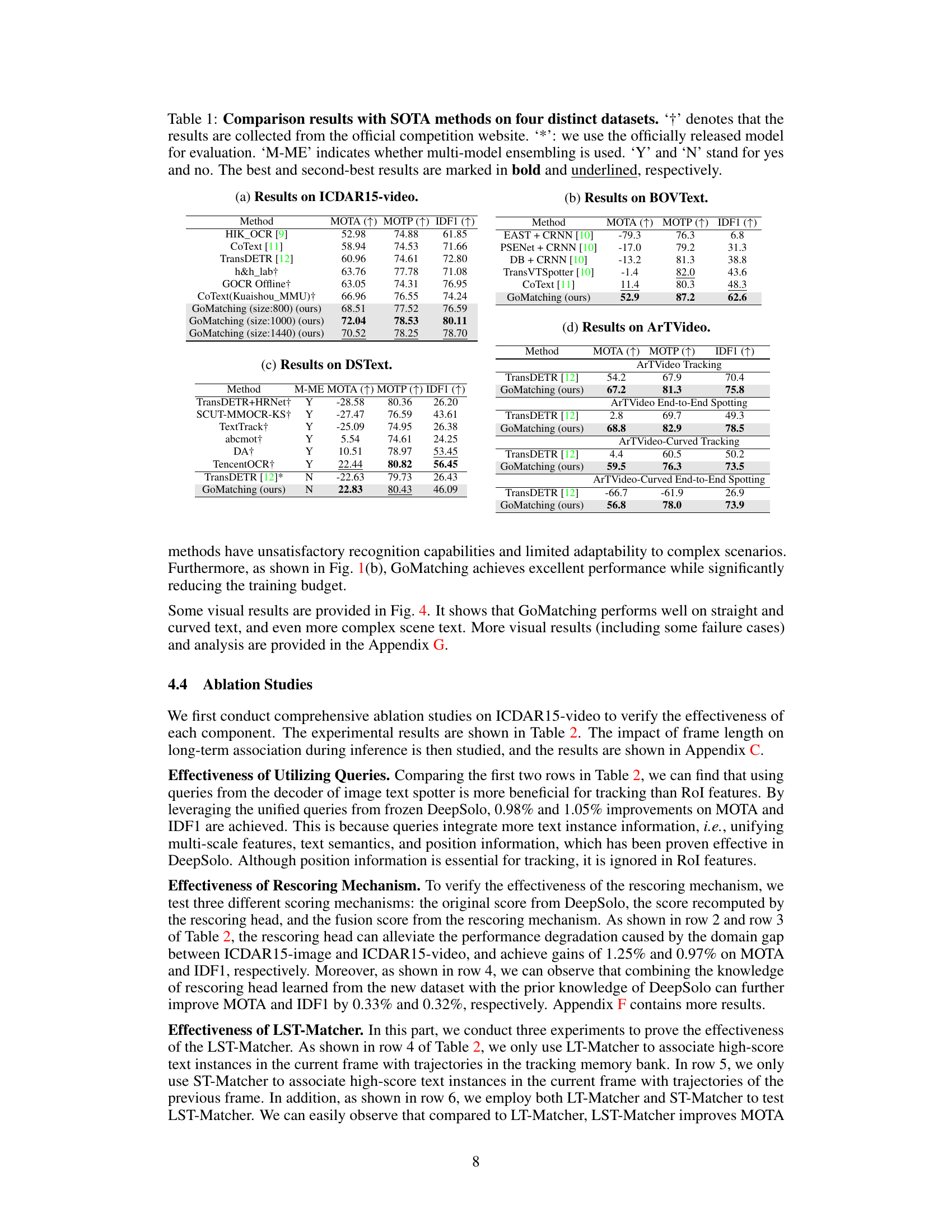

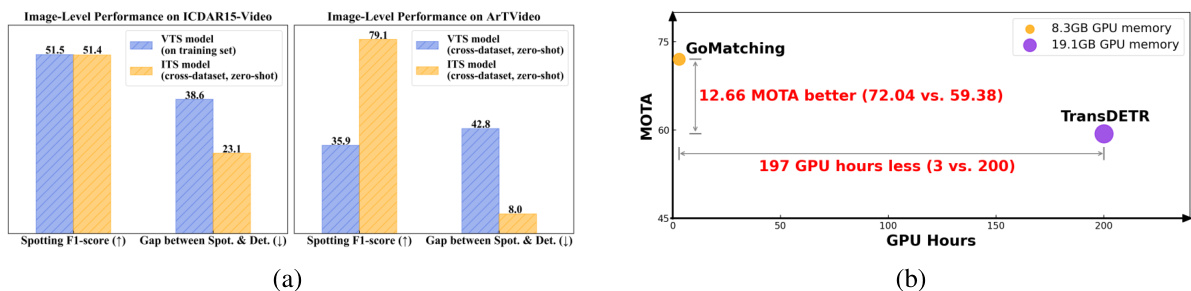

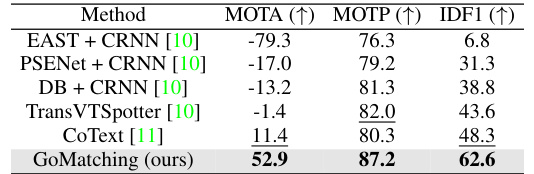

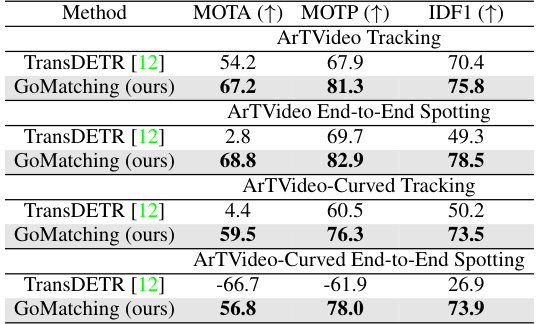

🔼 This table compares the performance of GoMatching against other state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on four different video text spotting datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. The metrics used for comparison are MOTA (Multiple Object Tracking Accuracy), MOTP (Multiple Object Tracking Precision), and IDF1 (Intersection over Union F1-score). The table also indicates whether each method used multi-model ensembling and whether the officially released model was used for evaluation. The best results for each dataset are highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison results with SOTA methods on four distinct datasets. ‘†’ denotes that the results are collected from the official competition website. ‘*’: we use the officially released model for evaluation. ‘M-ME’ indicates whether multi-model ensembling is used. ‘Y’ and ‘N’ stand for yes and no. The best and second-best results are marked in bold and underlined, respectively.

In-depth insights#

VTS Recognition Bottleneck#

The heading ‘VTS Recognition Bottleneck’ points to a critical issue in video text spotting (VTS): the underperformance of the recognition component compared to its image-based counterpart (ITS). The core problem is that VTS models struggle to accurately recognize text within video frames, lagging behind the detection capabilities. This suggests an imbalance in multi-task optimization, where the focus on tracking may detract from recognition accuracy. Addressing this bottleneck is key to improving VTS performance, potentially through techniques like improved training strategies, specialized model architectures, or better data augmentation to specifically enhance recognition. The researchers should explore whether integrating advanced ITS recognition models into a VTS framework, while focusing training efforts on the unique tracking aspects of VTS, could be a potential solution. This approach would leverages the robust recognition power of state-of-the-art ITS while minimizing suboptimal performance through specialized training for video text. Furthermore, investigation into the role of data quality and diversity is crucial. Insufficient diverse and complex video text data could be a significant factor contributing to the recognition bottleneck. Therefore, creation of robust and diverse benchmark datasets will be essential for future VTS research to overcome this bottleneck.

GoMatching Baseline#

The proposed GoMatching baseline offers a novel approach to video text spotting by leveraging a powerful, pre-trained image text spotter (DeepSolo) and focusing training efforts on the tracking aspect. This two-pronged strategy avoids suboptimal multi-task optimization often seen in end-to-end models. By freezing DeepSolo’s parameters, GoMatching significantly reduces training costs and time. The addition of a rescoring mechanism refines confidence scores, improving tracking performance. Furthermore, a Long-Short Term Matching (LST) module enhances tracking accuracy by integrating both short- and long-term temporal information. The overall system shows impressive results on standard benchmarks, highlighting the effectiveness of this decoupled, efficient approach. Arbitrary-shaped text recognition is also addressed, demonstrating GoMatching’s versatility. The simplicity of the design allows accommodation of diverse text scenarios (dense, small, etc.) with reduced training overhead.

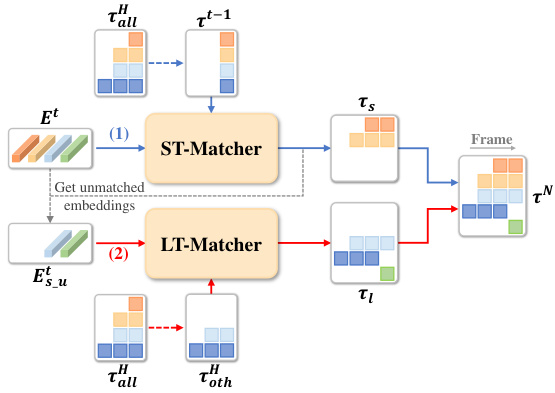

LST-Matcher Module#

The LST-Matcher module, a core component of the proposed GoMatching architecture for video text spotting, cleverly integrates long- and short-term matching mechanisms to robustly track text instances across video frames. Its two-stage design, comprising ST-Matcher and LT-Matcher, addresses the challenges of temporal variations and occlusions inherent in video data. ST-Matcher efficiently handles associations between adjacent frames, leveraging the inherent short-term temporal coherence. LT-Matcher excels in resolving complex tracking scenarios, such as instances lost due to significant occlusions or abrupt appearance changes. The use of Transformer encoders and decoders in both modules allows for efficient information fusion, enabling robust and accurate trajectory generation. Integration of long- and short-term contextual cues makes the module highly adept at handling scenarios with arbitrary-shaped texts, even under challenging conditions. The overall effectiveness of the LST-Matcher module is a key factor in achieving state-of-the-art results on multiple video text spotting benchmarks, showcasing its robustness and capability.

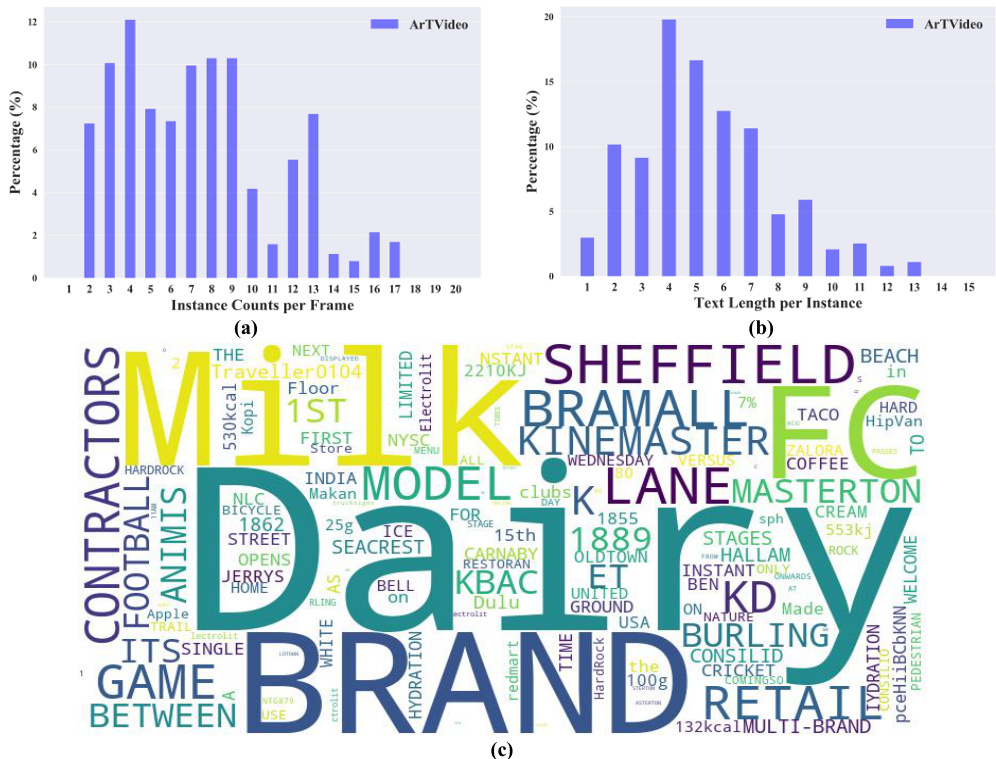

ArTVideo Dataset#

The creation of the ArTVideo dataset is a significant contribution to the field of video text spotting. The existing datasets largely lack sufficient examples of curved text, limiting the ability to train robust models capable of handling real-world scenarios. ArTVideo directly addresses this deficiency by including approximately 30% curved text instances, a feature absent in comparable datasets like ICDAR15-video and DSText. This inclusion is crucial for advancing the accuracy and generalization capabilities of video text spotting algorithms. The dataset also benefits from high-quality annotations, with straight text labeled using quadrilaterals and curved text annotated using polygons with 14 points for precise contour definition. This meticulous annotation approach ensures that the dataset is suitable for training advanced models. Furthermore, the diverse textual content and varied video backgrounds ensure generalizability, reducing the risk of overfitting to specific characteristics. ArTVideo’s focus on arbitrary-shaped text strengthens its value as a benchmark, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of video text spotting methods. Its release will undoubtedly spur research and development in this critical area, making it a valuable tool for improving the reliability of video text spotting applications.

Future VTS Research#

Future research in Video Text Spotting (VTS) should prioritize addressing the limitations of current methods. Improving the accuracy and robustness of text recognition in challenging video conditions (e.g., low resolution, motion blur, varying lighting) is crucial. This may involve exploring more advanced deep learning architectures or incorporating domain-specific knowledge. Developing more efficient and scalable tracking algorithms that can handle dense text and complex scenes is also vital. The creation of larger, more diverse, and comprehensively annotated datasets containing various text types, shapes, languages, and scene contexts is needed to train and evaluate more robust VTS models. Finally, research should focus on developing VTS systems capable of real-time processing for applications such as autonomous driving and live video captioning, demanding highly optimized models and efficient inference techniques. The development of benchmark datasets with arbitrary-shaped texts, multilingual support, and general scene understanding is essential for pushing the field forward.

More visual insights#

More on figures

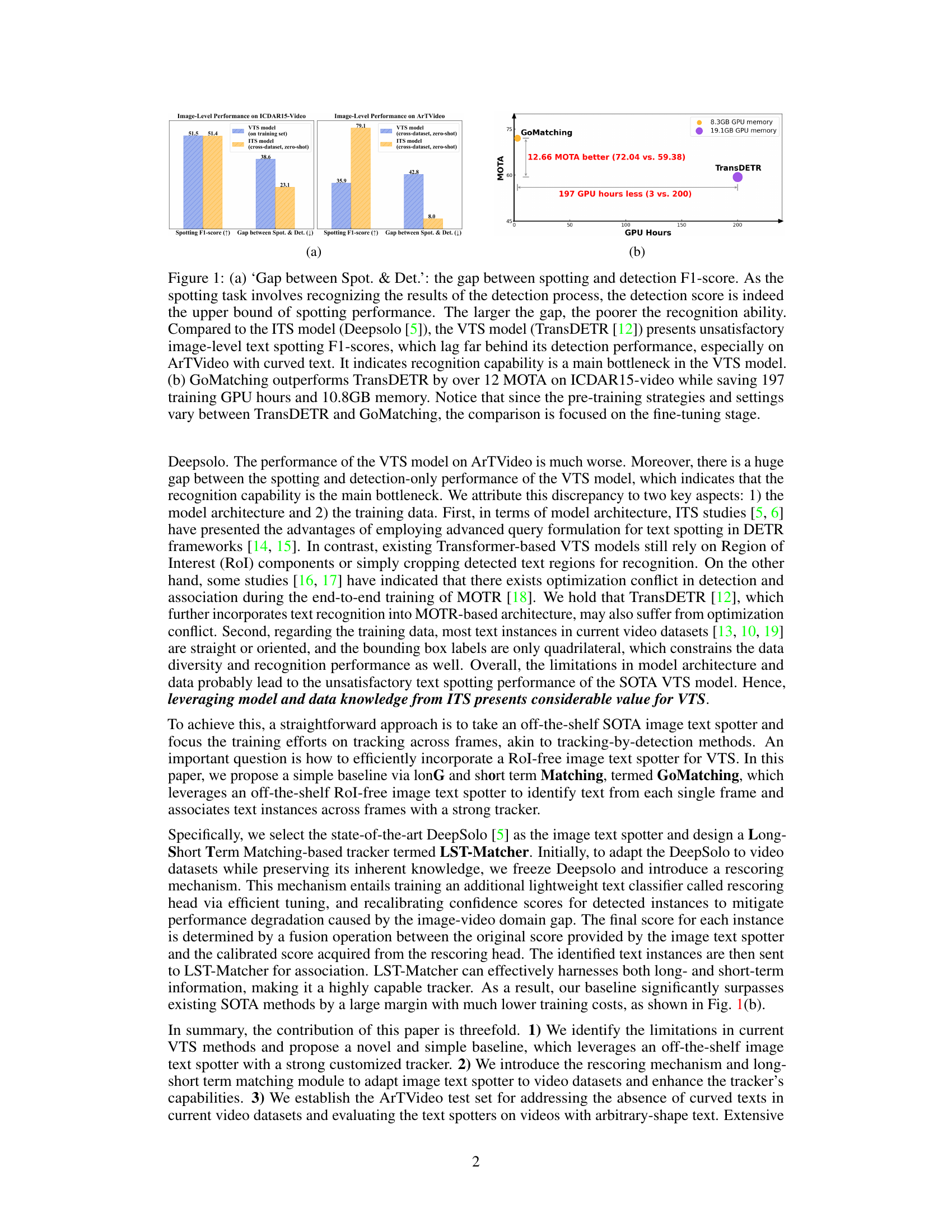

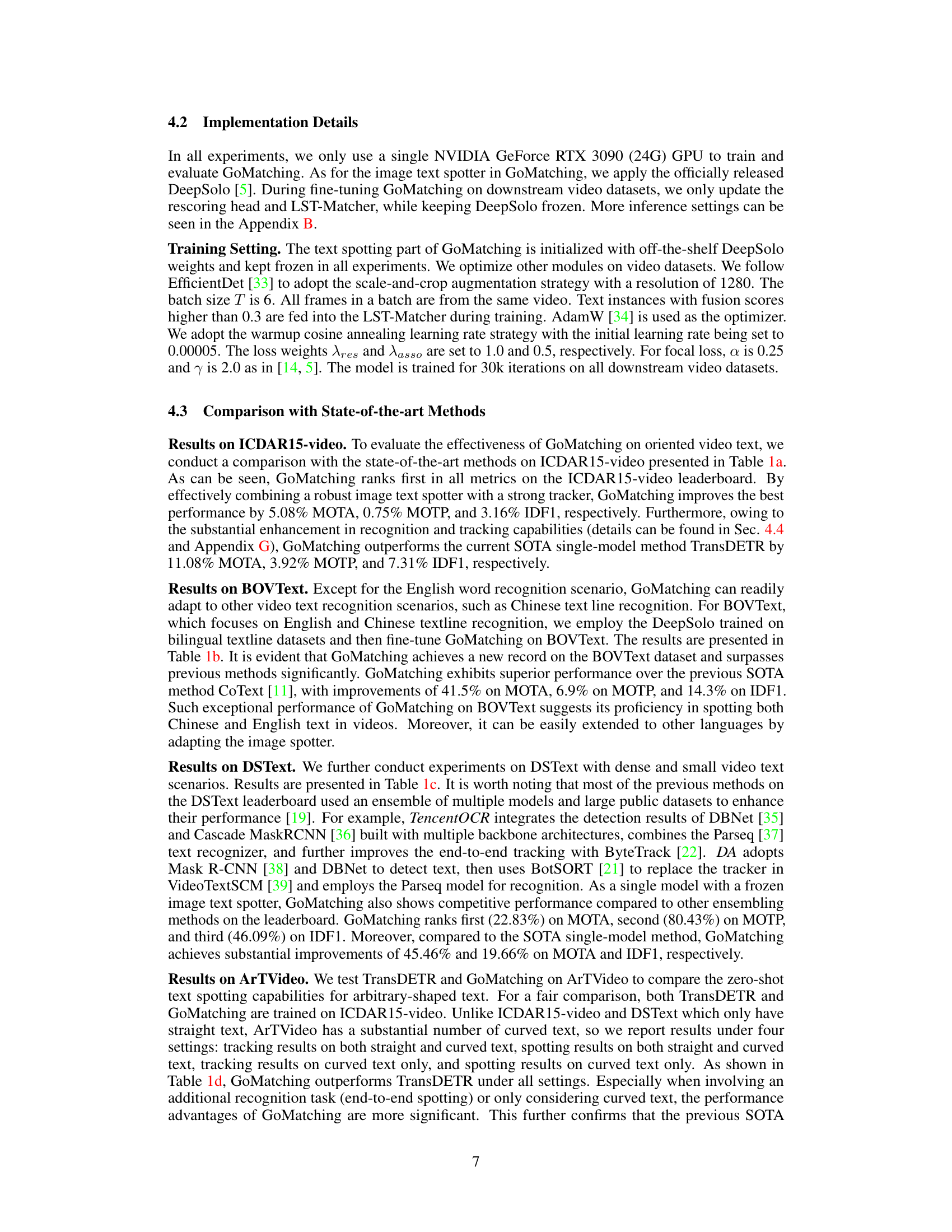

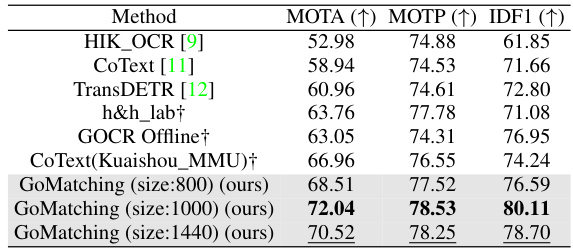

🔼 The figure illustrates the architecture of GoMatching, a video text spotting method. It comprises three main components: a frozen image text spotter (DeepSolo), a rescoring head, and a Long-Short Term Matching (LST-Matcher) module. The image text spotter initially processes each frame to detect and recognize text instances; a rescoring head then refines the confidence scores to improve the accuracy of text detection in video context. Finally, LST-Matcher, incorporating both short-term and long-term information, links text instances across consecutive frames to generate complete text trajectories. The overall process aims at mitigating performance degradation between image and video domains while ensuring robust text tracking.

read the caption

Figure 2: The overall architecture of GoMatching. The frozen image text spotter provides text spotting results for frames. The rescoring mechanism considers both instance scores from the image text spotter and a trainable rescoring head to reduce performance degradation due to the domain gap. Long-short term matching module (LST-Matcher) assigns IDs to text instances based on the queries in long-short term frames. The yellow star sign ‘★’ indicates the final output of GoMatching.

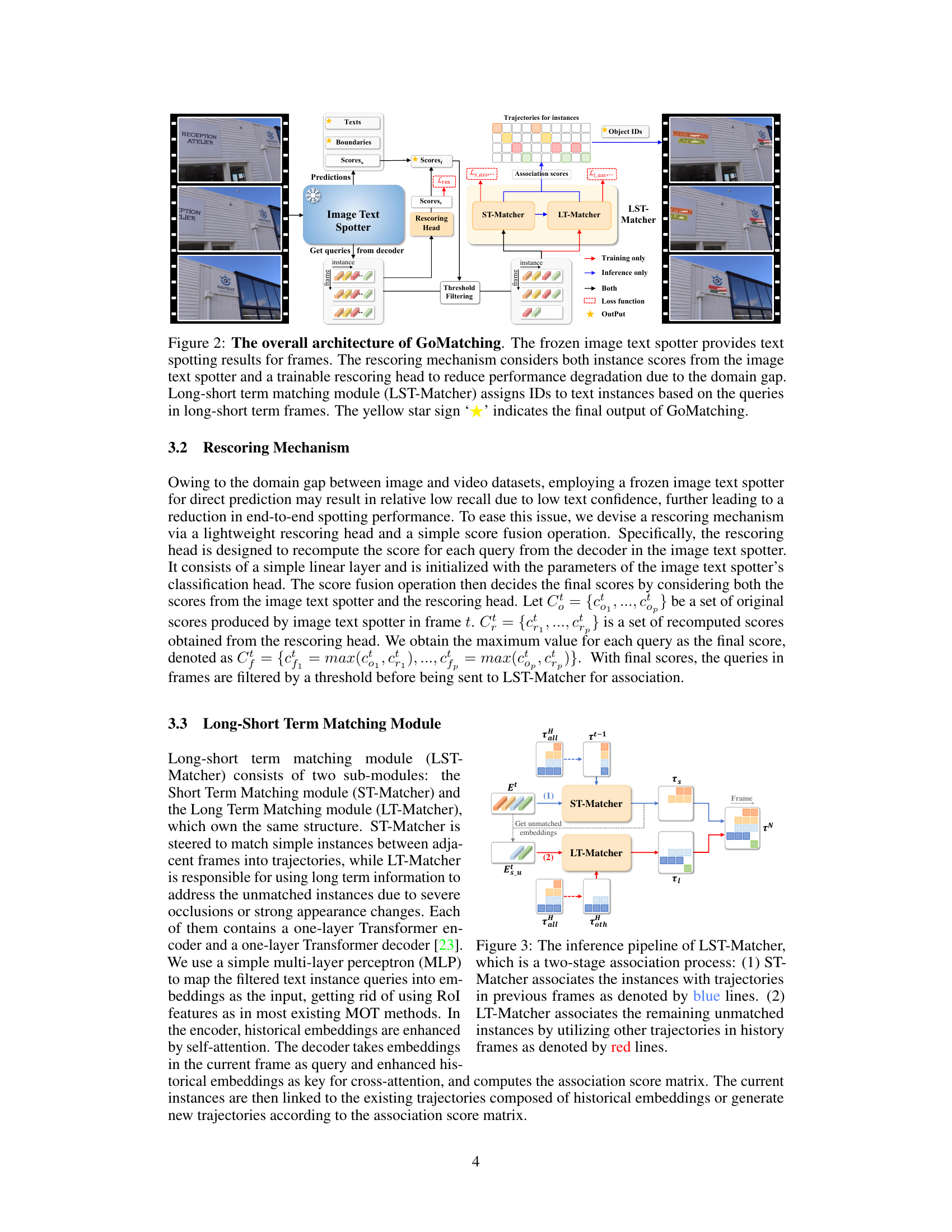

🔼 This figure illustrates the two-stage association process within the Long-Short Term Matching (LST-Matcher) module. The first stage, using the Short Term Matcher (ST-Matcher), links current text instances to trajectories from the immediately preceding frame. The second stage, employing the Long Term Matcher (LT-Matcher), handles instances not successfully matched in the first stage, using trajectories from further back in the video’s history to account for occlusions or significant appearance changes. The blue lines represent associations made by the ST-Matcher, while red lines show those made by the LT-Matcher. This ensures robust tracking across multiple frames by leveraging both short-term and long-term context.

read the caption

Figure 3: The inference pipeline of LST-Matcher, which is a two-stage association process: (1) ST-Matcher associates the instances with trajectories in previous frames as denoted by blue lines. (2) LT-Matcher associates the remaining unmatched instances by utilizing other trajectories in history frames as denoted by red lines.

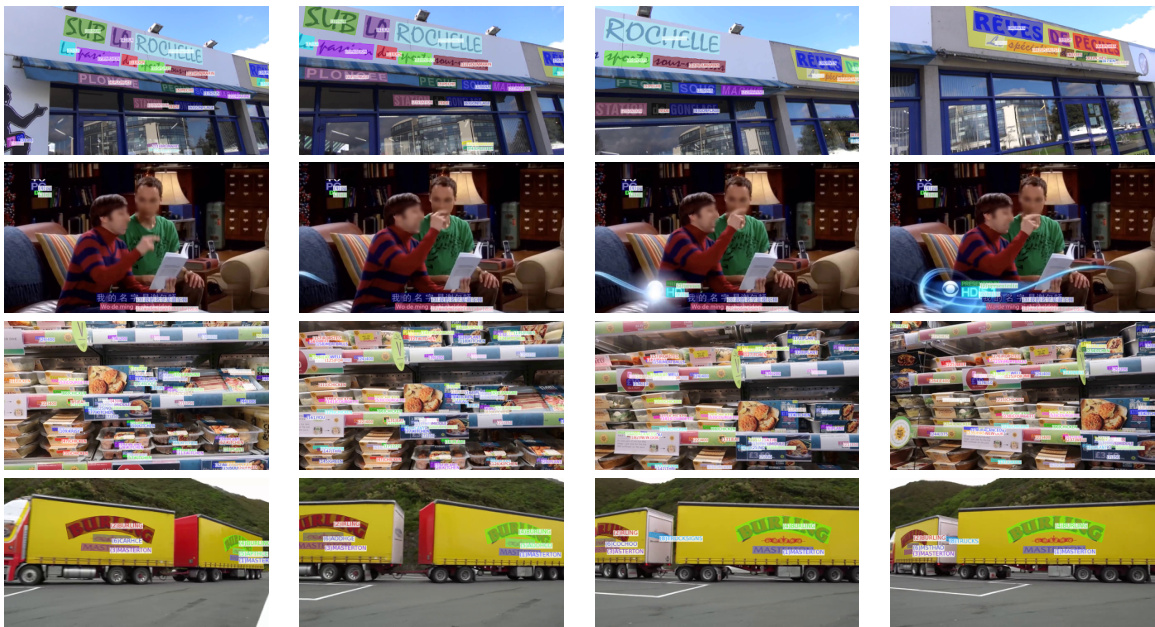

🔼 This figure shows visual examples of video text spotting results obtained using the proposed GoMatching method. It presents results on four different datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. Each row corresponds to a dataset, displaying several video frames with detected text instances. Text instances belonging to the same trajectory (tracked across frames) share the same color, illustrating the tracking capabilities of the method. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness of GoMatching in various scenarios including different video characteristics and text complexities.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visual results of video text spotting. Images from top to bottom are the results on ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo, respectively. Text instances belonging to the same trajectory are assigned the same color.

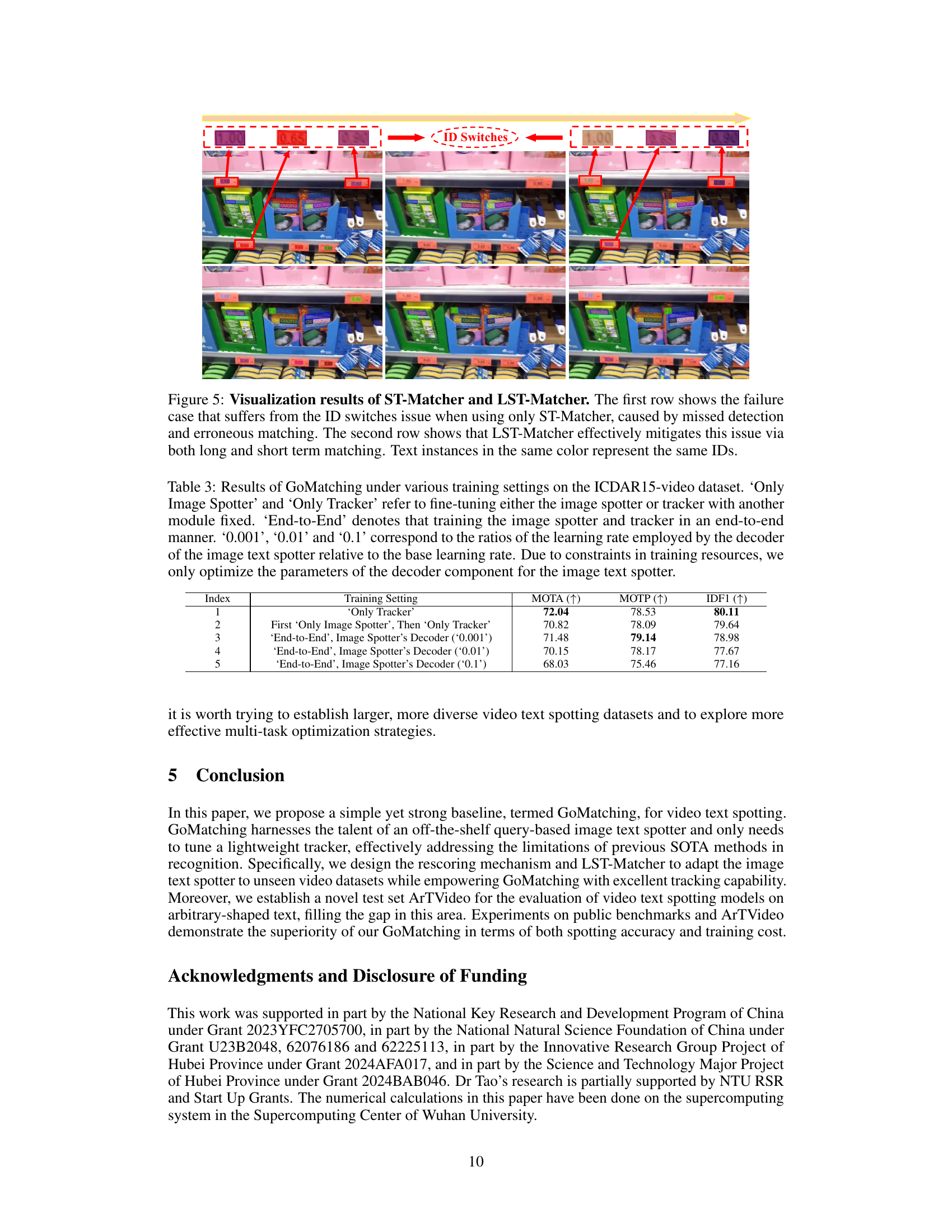

🔼 This figure compares the tracking performance of ST-Matcher (short-term matching) and LST-Matcher (long and short-term matching). The top row illustrates a failure case where ST-Matcher leads to ID switches due to missed detections and incorrect associations. The bottom row shows how LST-Matcher effectively addresses this issue by incorporating both short-term and long-term information to maintain consistent tracking of text instances.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visualization results of ST-Matcher and LST-Matcher. The first row shows the failure case that suffers from the ID switches issue when using only ST-Matcher, caused by missed detection and erroneous matching. The second row shows that LST-Matcher effectively mitigates this issue via both long and short term matching. Text instances in the same color represent the same IDs.

🔼 This figure shows visual examples from the ArTVideo dataset, highlighting the annotation differences between straight and curved text. Straight text is annotated using bounding boxes (quadrilaterals), while curved text is annotated with polygons. The consistent color coding across columns helps to visually track the same text instances through time.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visual examples from our ArTVideo. The straight and curved text are labeled with quadrilaterals and polygons, respectively. The same background color in different frames (columns) denotes the same instance.

🔼 This figure showcases the video text spotting results of the GoMatching model on four different datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. Each row displays results from one dataset. Within each row, multiple images from a video clip are shown with bounding boxes around detected text instances. The color of the bounding boxes indicates the same text trajectory across consecutive frames. This helps visualize the accuracy of the model’s ability to track and recognize text instances over time.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visual results of video text spotting. Images from top to bottom are the results on ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo, respectively. Text instances belonging to the same trajectory are assigned the same color.

🔼 This figure showcases the video text spotting results of GoMatching on four different datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. Each row presents the results from one dataset, showing the detected text instances with bounding boxes. Text instances belonging to the same trajectory across multiple frames are assigned the same color for easy visualization and tracking. The figure demonstrates GoMatching’s ability to accurately detect and track text in various scenarios, including those with arbitrary-shaped texts.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visual results of video text spotting. Images from top to bottom are the results on ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo, respectively. Text instances belonging to the same trajectory are assigned the same color.

🔼 This figure displays the visual results of video text spotting using the GoMatching method on four different datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. Each row presents the results for a specific dataset, showing how the algorithm accurately identifies and tracks text instances across video frames. Text instances belonging to the same trajectory are highlighted with the same color to help visualize the tracking process. This is a qualitative assessment demonstrating the effectiveness of the algorithm in handling various text characteristics and scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visual results of video text spotting. Images from top to bottom are the results on ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo, respectively. Text instances belonging to the same trajectory are assigned the same color.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the proposed GoMatching method against state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on four different video text spotting datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. The comparison uses three evaluation metrics: MOTA, MOTP, and IDF1, providing a comprehensive assessment of each method’s performance on various scenarios and text characteristics. The table also indicates whether SOTA methods utilized multi-model ensembling and whether the results were obtained from official competition leaderboards or by using officially released models.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison results with SOTA methods on four distinct datasets. '†' denotes that the results are collected from the official competition website. ‘*': we use the officially released model for evaluation. 'M-ME' indicates whether multi-model ensembling is used. 'Y' and 'N' stand for yes and no. The best and second-best results are marked in bold and underlined, respectively.

🔼 This table compares the performance of GoMatching against other state-of-the-art (SOTA) video text spotting methods on four benchmark datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. The metrics used for comparison are MOTA (Multiple Object Tracking Accuracy), MOTP (Multiple Object Tracking Precision), and IDF1 (Intersection over Union F1-score). The table also indicates whether each method used multiple model ensembling (M-ME) and whether the official released model was used for evaluation.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison results with SOTA methods on four distinct datasets. '†' denotes that the results are collected from the official competition website. ‘*': we use the officially released model for evaluation. 'M-ME' indicates whether multi-model ensembling is used. 'Y' and 'N' stand for yes and no. The best and second-best results are marked in bold and underlined, respectively.

🔼 This table compares the performance of GoMatching against other state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on four video text spotting datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. For each dataset, it presents the MOTA, MOTP, and IDF1 scores, key metrics for evaluating video text spotting performance. The table also notes whether the competing methods used multiple models, and whether the results were obtained from official competitions or using the officially released model weights. The best and second-best results for each metric are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison results with SOTA methods on four distinct datasets. '†' denotes that the results are collected from the official competition website. ‘*': we use the officially released model for evaluation. 'M-ME' indicates whether multi-model ensembling is used. 'Y' and 'N' stand for yes and no. The best and second-best results are marked in bold and underlined, respectively.

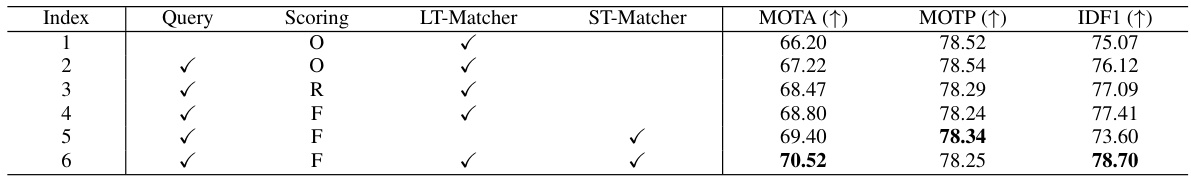

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results, showing the impact of different components of the GoMatching model on its performance. It shows how using queries instead of RoI features, different scoring mechanisms (original DeepSolo scores, rescored scores, fused scores), and different combinations of the Long-Term Matcher and Short-Term Matcher impact MOTA, MOTP, and IDF1 scores. This helps assess the contribution of each component.

read the caption

Table 2: Impact of difference components in the proposed GoMatching. 'Query' indicates that LST-Matcher employs the queries of high-score text instances for association, otherwise RoI features. Column 'Scoring' indicates the employed scoring mechanism, in which ‘O' means using the original scores from DeepSolo, 'R' means using the scores recomputed by the rescoring head, and 'F' means using the fusion scores obtained from the rescoring mechanism.

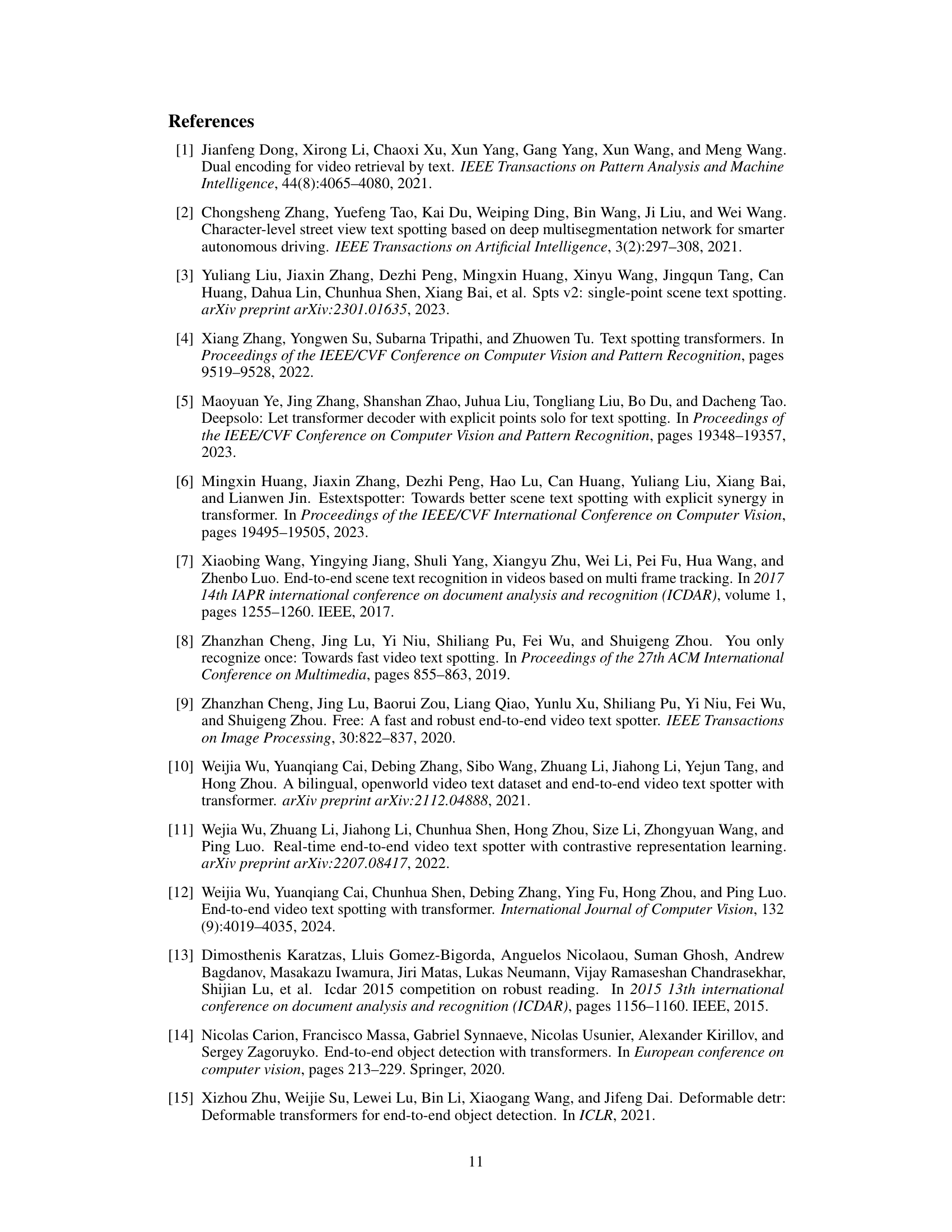

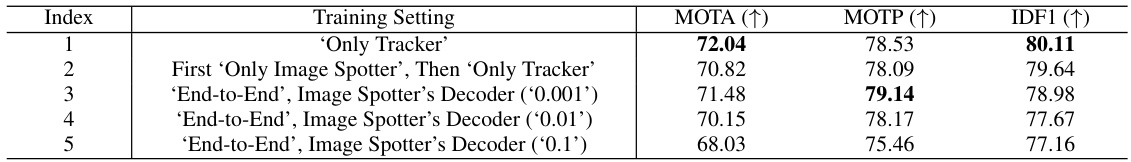

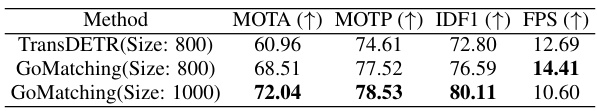

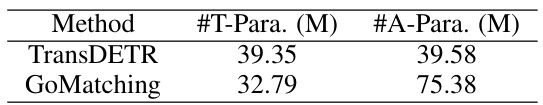

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on different training strategies for GoMatching on the ICDAR15-video dataset. It compares the performance (MOTA, MOTP, IDF1) of three approaches: training only the tracker, pre-training the image spotter then training the tracker, and end-to-end training of both. The end-to-end training explores different learning rates for the decoder of the image spotter. The results highlight the impact of various training strategies on the model’s performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of GoMatching under various training settings on the ICDAR15-video dataset. 'Only Image Spotter' and 'Only Tracker' refer to fine-tuning either the image spotter or tracker with another module fixed. 'End-to-End' denotes that training the image spotter and tracker in an end-to-end manner. '0.001', ‘0.01' and '0.1' correspond to the ratios of the learning rate employed by the decoder of the image text spotter relative to the base learning rate. Due to constraints in training resources, we only optimize the parameters of the decoder component for the image text spotter.

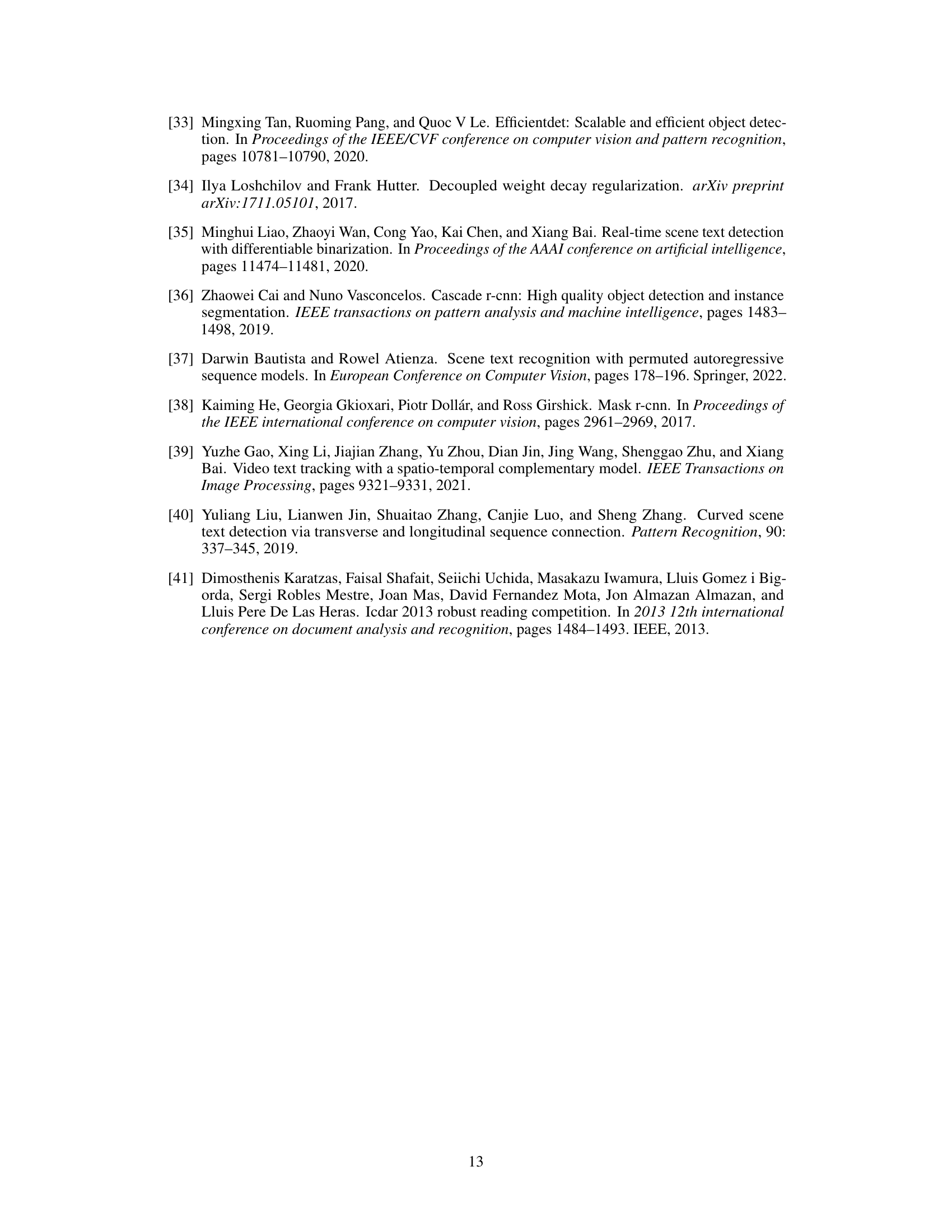

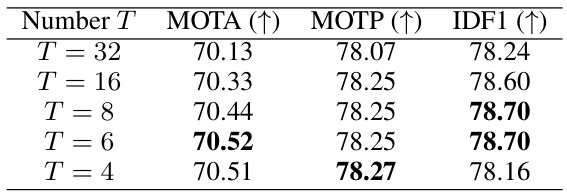

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies performed on the ICDAR15-video dataset to determine the optimal number of frames (T) to consider for long-term associations in the LT-Matcher component of the GoMatching model. The max number of history frames in the tracking memory bank is always one less than T (H = T-1). The table shows the impact of varying the frame number (T) on three key evaluation metrics: MOTA, MOTP, and IDF1. The best-performing value of T for each metric is highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation studies on the number of frames (T) for long-term association in LT-Matcher, and the max number of history frames in tracking memory bank is H = T – 1). Experiments are conducted on ICDAR15-video and the best results are marked in bold.

🔼 This table compares the performance of GoMatching against state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on four video text spotting datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. It shows the MOTA, MOTP, and IDF1 scores for each method, indicating the accuracy and efficiency of text spotting. The table also notes whether methods used multi-model ensembles and whether the models used were officially released models or not. It highlights the superior performance of GoMatching in achieving new state-of-the-art results.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison results with SOTA methods on four distinct datasets. '†' denotes that the results are collected from the official competition website. ‘*': we use the officially released model for evaluation. 'M-ME' indicates whether multi-model ensembling is used. 'Y' and 'N' stand for yes and no. The best and second-best results are marked in bold and underlined, respectively.

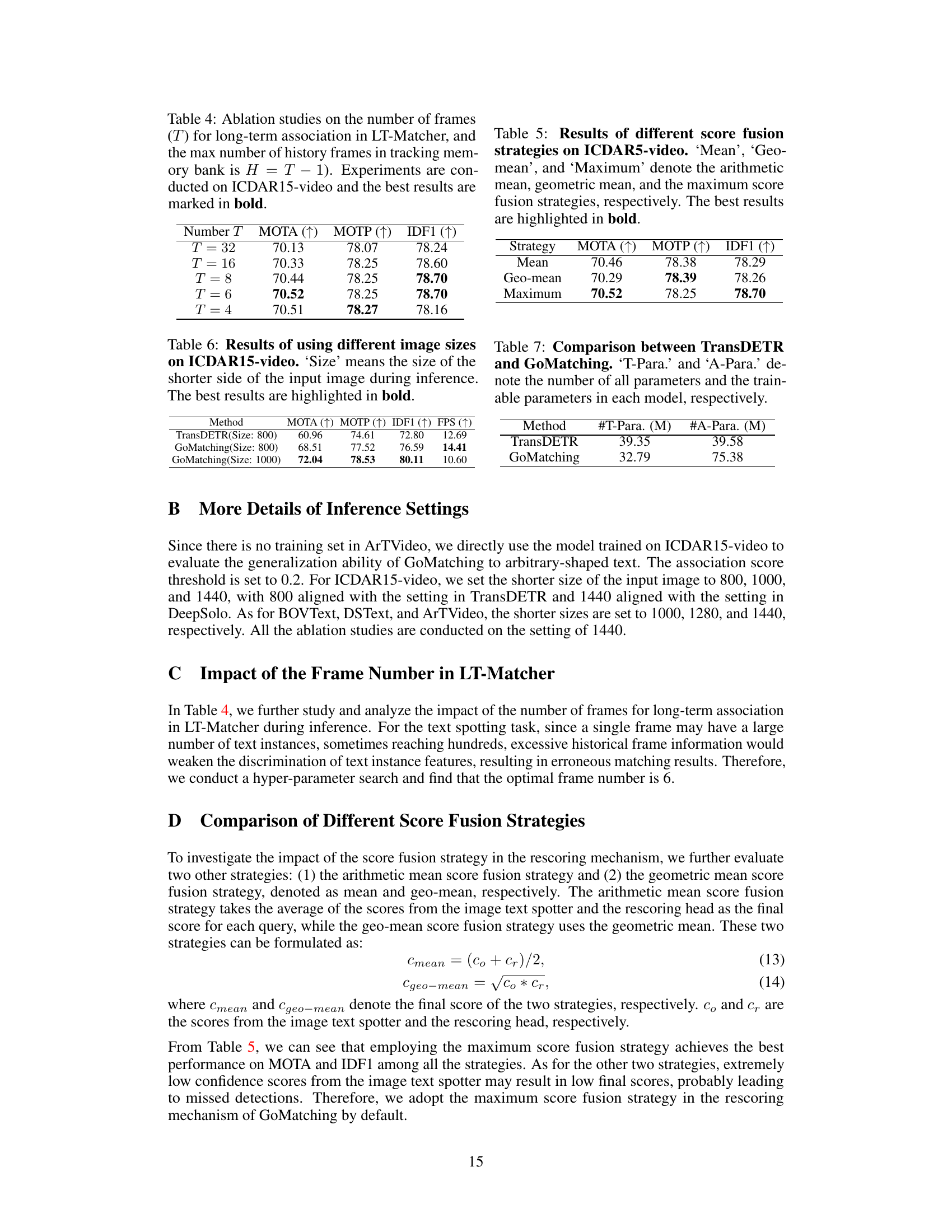

🔼 This table presents the results of three different score fusion strategies used in the rescoring mechanism of GoMatching on the ICDAR15-video dataset. The strategies compared are the arithmetic mean, the geometric mean, and selecting the maximum score. The table shows the resulting MOTA, MOTP, and IDF1 scores for each strategy. The best performing strategy for each metric is highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 5: Results of different score fusion strategies on ICDAR5-video. ‘Mean’, ‘Geo-mean’, and ‘Maximum’ denote the arithmetic mean, geometric mean, and the maximum score fusion strategies, respectively. The best results are highlighted in bold.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the proposed GoMatching method with state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on four video text spotting datasets: ICDAR15-video, BOVText, DSText, and ArTVideo. The table displays the performance metrics (MOTA, MOTP, and IDF1) achieved by each method on each dataset. It also indicates whether the method used multi-model ensembling and whether the official model was used for evaluation. The best and second-best results for each metric are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison results with SOTA methods on four distinct datasets. ‘†’ denotes that the results are collected from the official competition website. ‘*’: we use the officially released model for evaluation. ‘M-ME’ indicates whether multi-model ensembling is used. ‘Y’ and ‘N’ stand for yes and no. The best and second-best results are marked in bold and underlined, respectively.

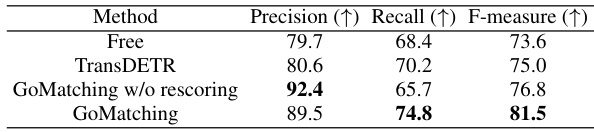

🔼 This table presents a comparison of video text detection performance on the ICDAR2013-video dataset. Three methods are compared: Free, TransDETR, and GoMatching (with and without the rescoring mechanism). The results are given in terms of precision, recall, and F-measure. GoMatching achieves the best F-measure, highlighting its effectiveness in video text detection.

read the caption

Table 8: Video text detection performance on ICDAR2013-video [41]. The best results are highlighted in bold.

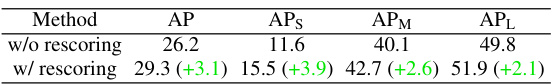

🔼 This table compares the Average Precision (AP) of object detection on the ICDAR13-video dataset with and without the rescoring mechanism. The rescoring mechanism improves the overall AP, particularly for smaller objects (APs) and medium-sized objects (APm). This highlights the benefits of the rescoring mechanism in improving detection performance.

read the caption

Table 9: Comparison results of detection AP on the ICDAR13-video between with and without the rescoring mechanism.

Full paper#