↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Backdoor attacks, where malicious functionalities are secretly injected into deep learning models, pose a significant threat. Current defenses often focus on inverting backdoor triggers in the input or feature space, but these methods suffer from high computational costs and a reliance on easily identifiable features which limits their effectiveness against sophisticated attacks that employ less prominent or dynamic triggers. These methods can easily be evaded by adversaries using more complex and dynamic triggers.

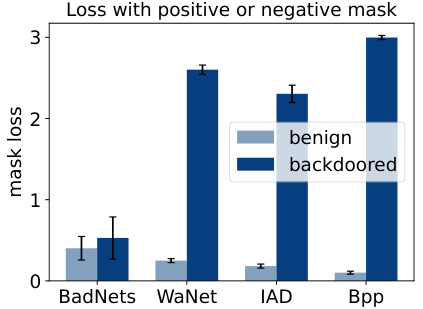

To address these issues, the researchers propose BAN (Backdoors Activated by Adversarial Neuron Noise). BAN leverages adversarial neuron noise to activate backdoor neurons, thus making backdoored models more sensitive to noise compared to benign models. This approach, coupled with feature space trigger inversion, allows for significantly more efficient backdoor detection and mitigation, outperforming existing methods by a large margin in terms of efficiency and accuracy. Furthermore, BAN offers a simple yet effective defense for removing backdoors by fine-tuning the model with adversarially generated noise.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on backdoor attacks in deep learning. It highlights a critical vulnerability in existing defense mechanisms and proposes a novel, efficient solution. This work opens new avenues for research by demonstrating that adversarial neuron noise can effectively reveal backdoor activations. The findings directly impact the design and development of more robust backdoor defenses and further enhances our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of backdoor attacks. The public availability of code and models also accelerates research progress in this field.

Visual Insights#

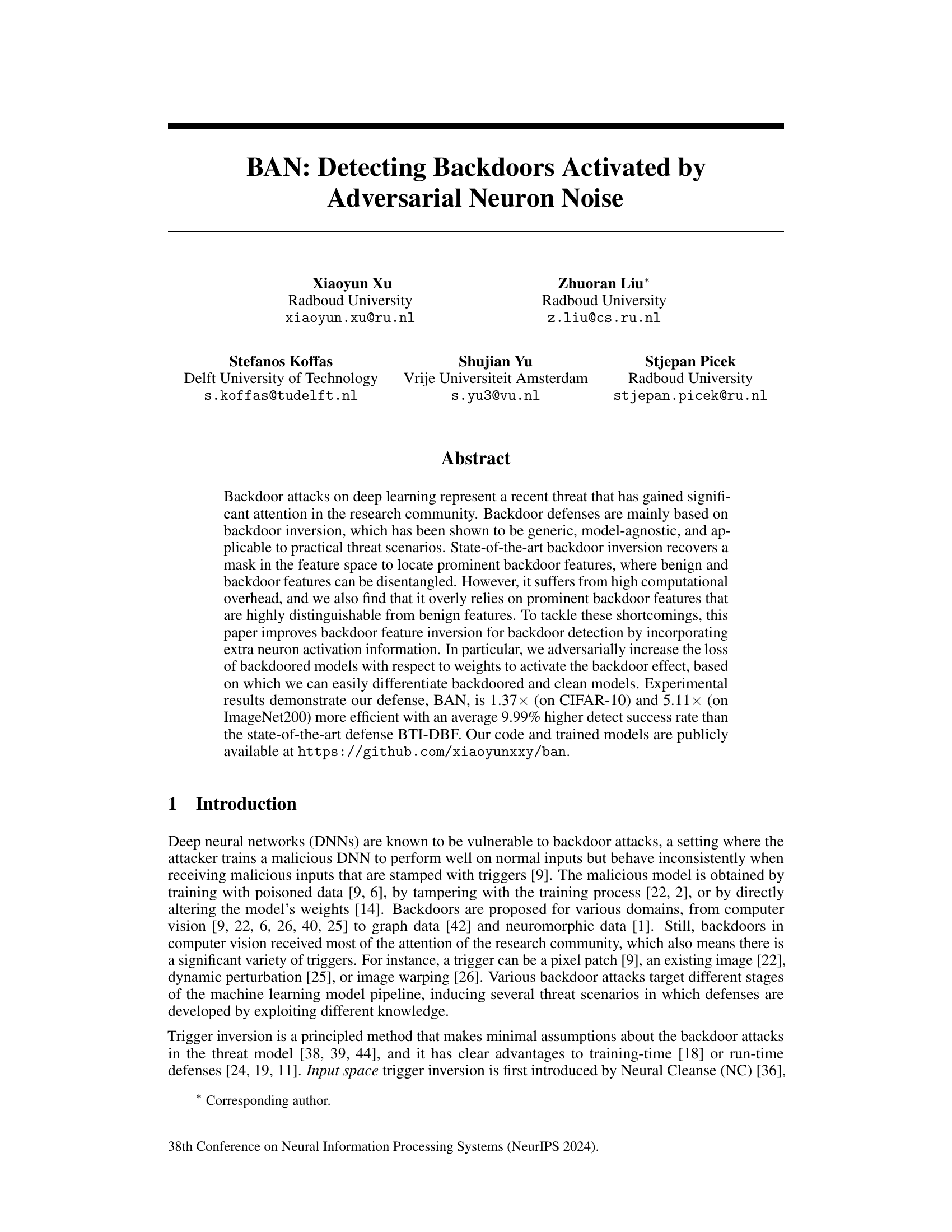

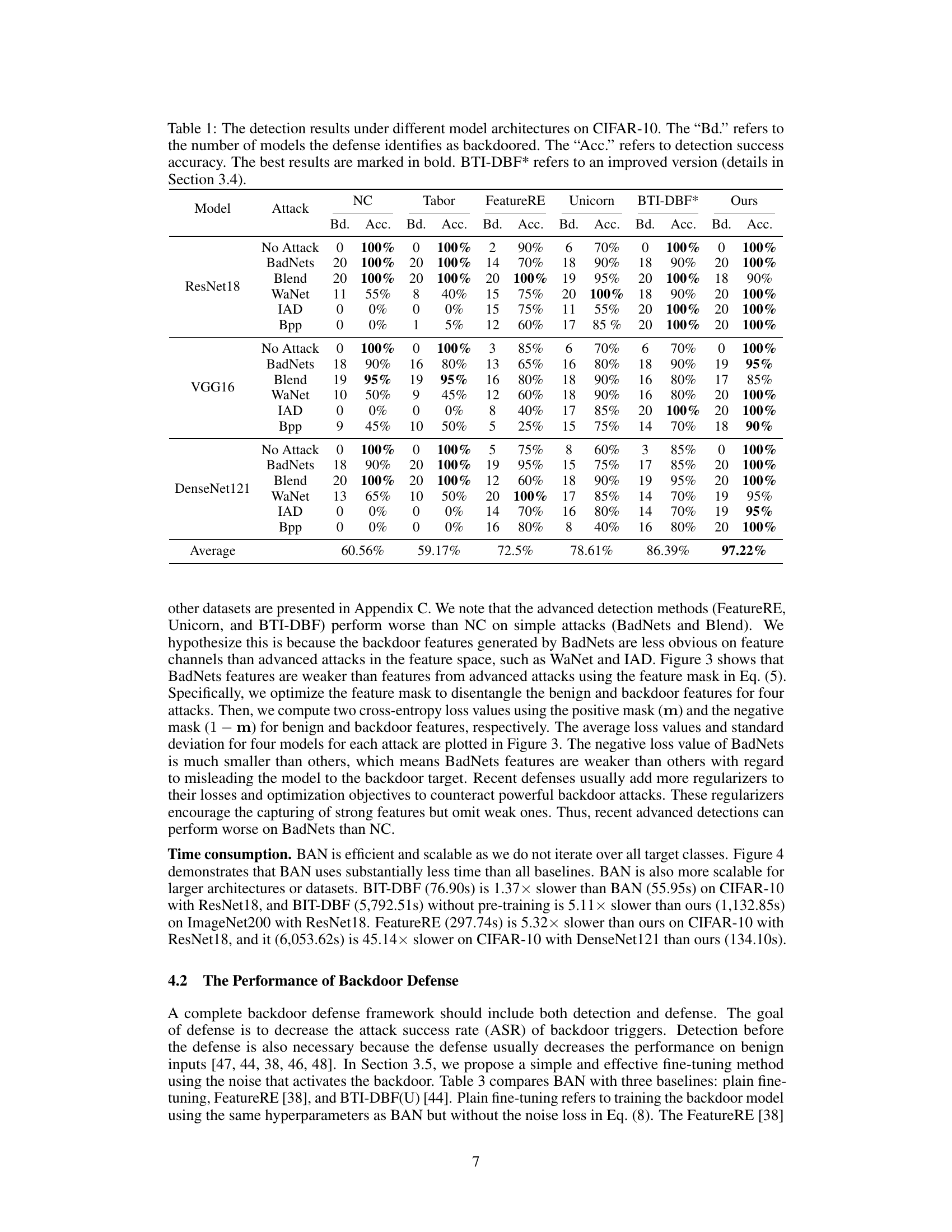

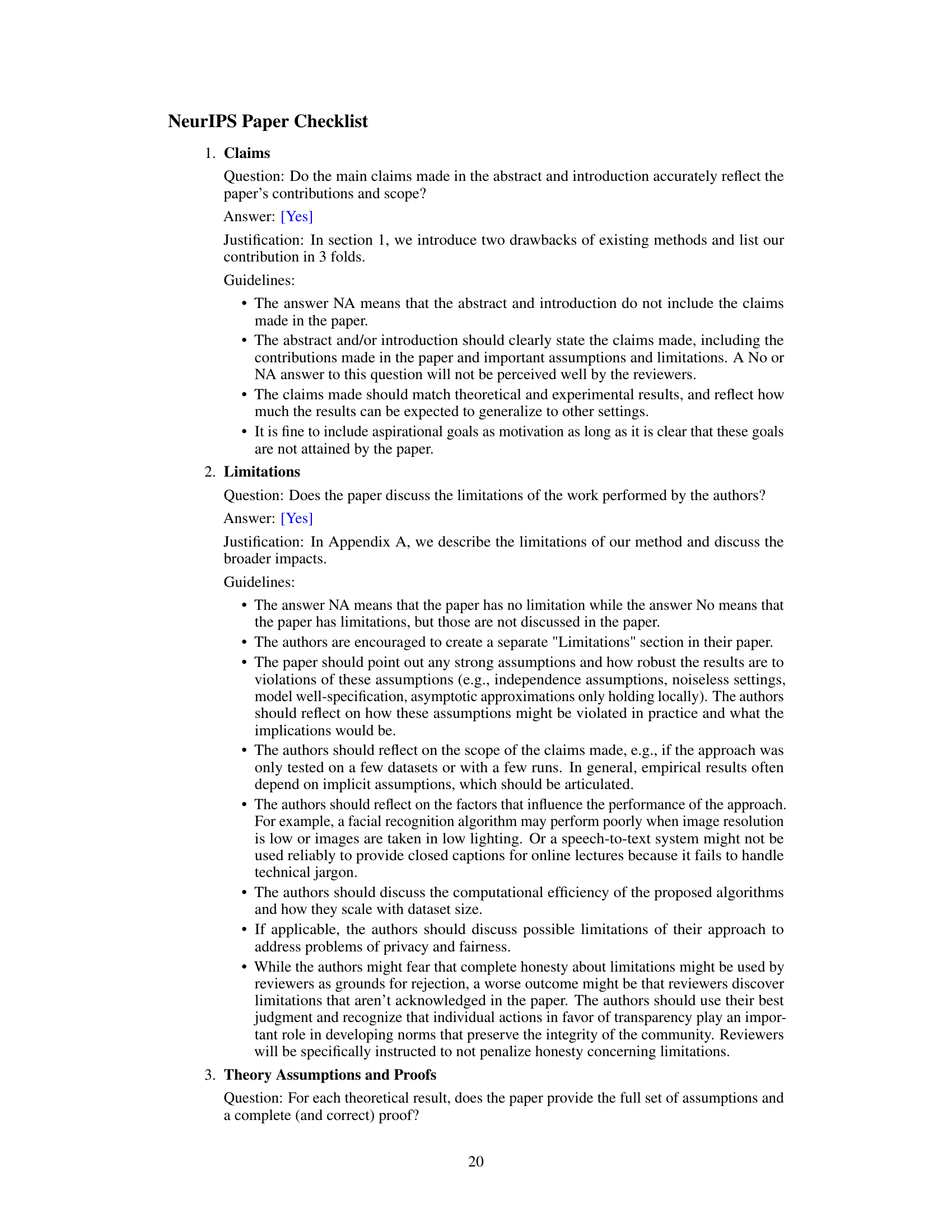

This figure visualizes the effect of adversarially added neuron noise on the feature representations of clean and backdoored models using t-SNE. As the noise (epsilon) increases from 0.0 to 0.3, the backdoored model misclassifies a growing proportion of data points from all classes as the target class, indicated by the increasing concentration of dark blue points. In contrast, the clean model shows a much smaller increase in misclassifications, maintaining a clearer separation between classes.

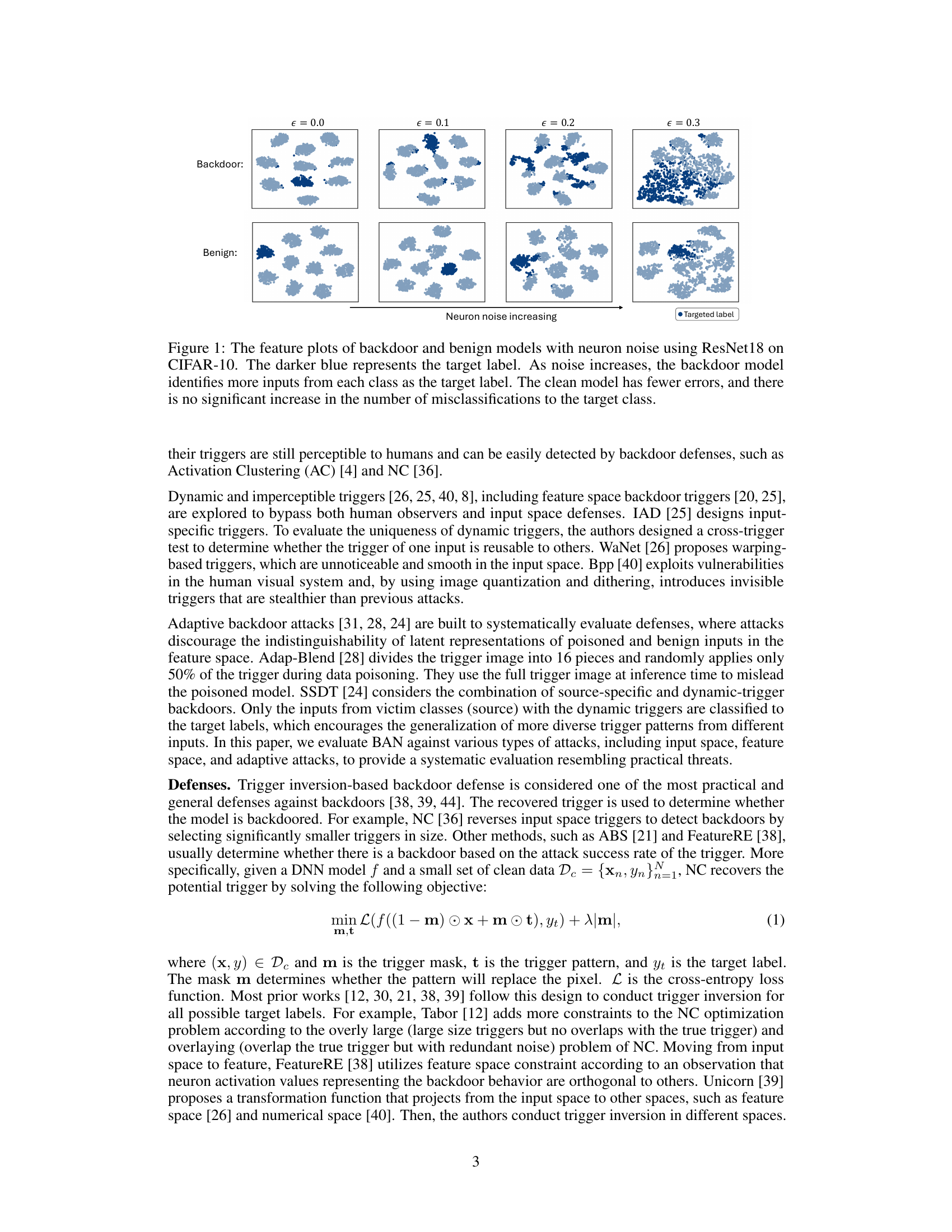

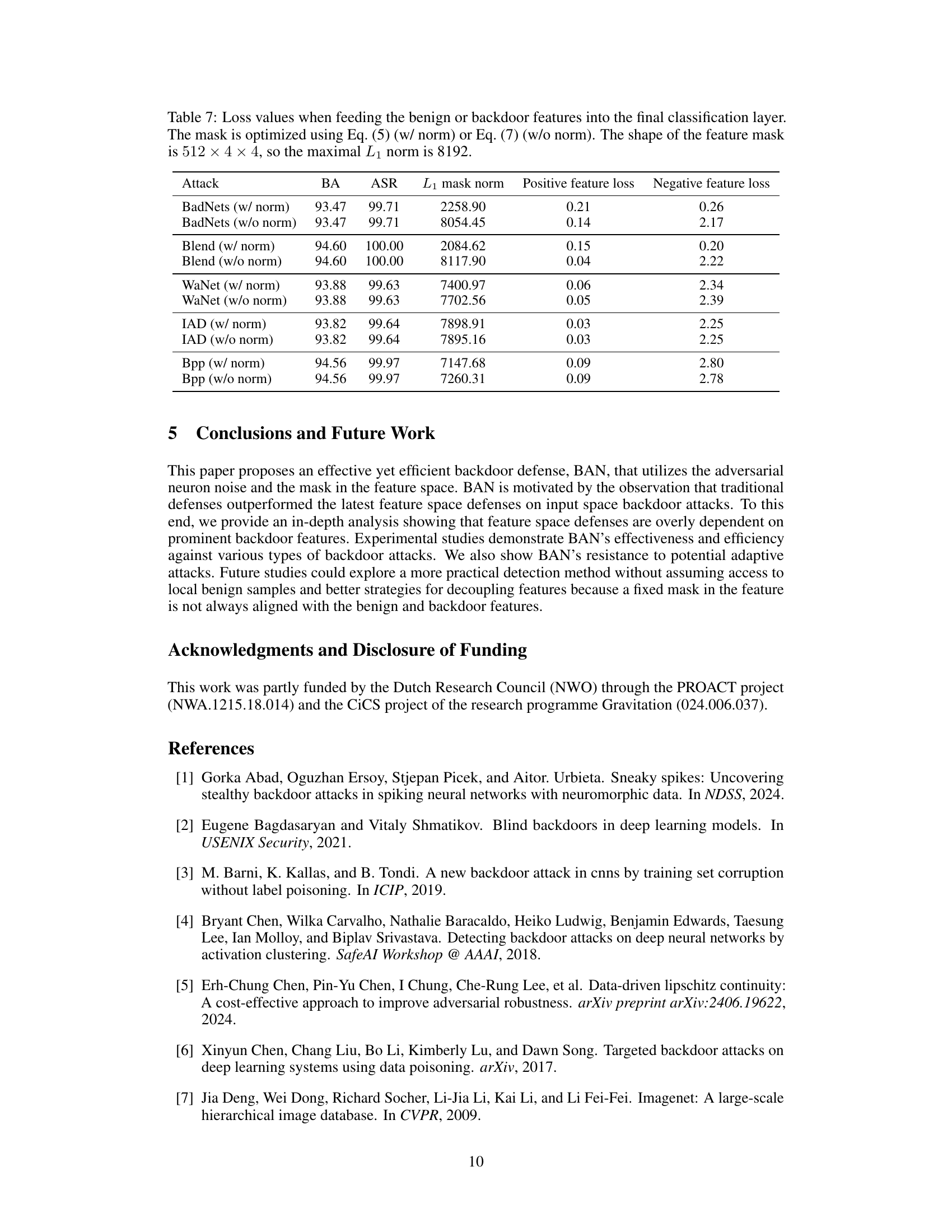

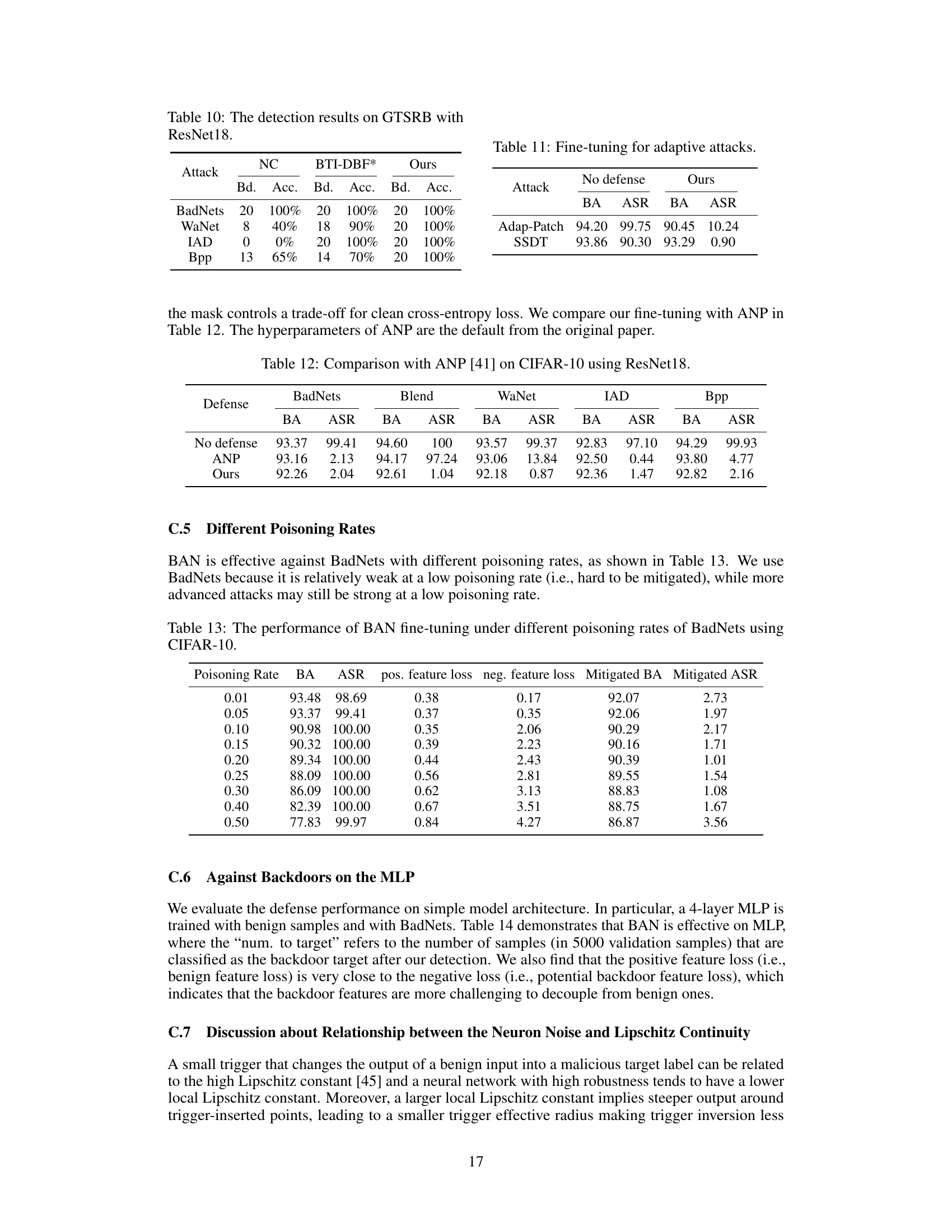

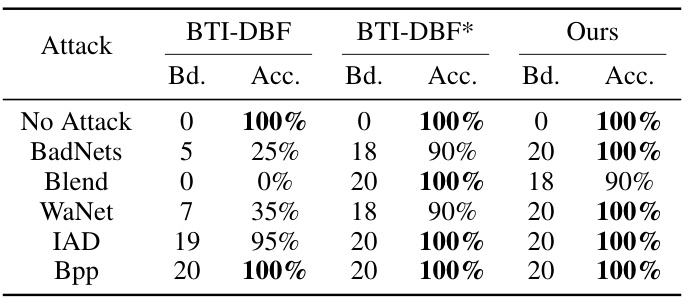

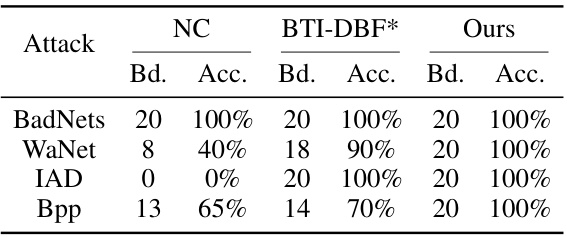

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments performed on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). For each model and architecture, the table shows the number of backdoored models correctly identified (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of the detection (‘Acc.’). The results are presented for various backdoor attacks (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, Bpp) and for a no-attack baseline. The table also highlights the best-performing method for each scenario.

In-depth insights#

Backdoor Inversion#

Backdoor inversion is a crucial concept in the field of deep learning security, focusing on identifying and mitigating the malicious functionality embedded within poisoned neural networks. The core idea revolves around reversing the backdoor’s effect to reveal the trigger or the poisoned features that activate it. Successful inversion techniques provide valuable insights into the nature of the attack, enabling researchers to develop more robust defenses. However, existing backdoor inversion methods face significant challenges, including high computational costs, a reliance on prominent backdoor features, and difficulties in handling sophisticated attacks like dynamic triggers or adaptive backdoors. Future research should address these limitations by improving inversion efficiency, making methods more robust against various trigger types, and exploring new algorithms for disentangling benign and poisoned features within the model’s feature space. This will lead to more effective defense strategies and enhance the overall security of deep learning systems against backdoor attacks.

Adversarial Noise#

The concept of ‘adversarial noise’ in the context of deep learning security is crucial. It refers to carefully crafted perturbations added to input data, designed to mislead a neural network into making incorrect predictions. These perturbations are often imperceptible to humans but can significantly impact model accuracy. The paper likely explores how adversarial noise, specifically targeting neurons associated with backdoor triggers, can reveal the presence of malicious backdoors. By analyzing the model’s response to this noise, researchers can potentially differentiate between clean and poisoned models. The effectiveness of this approach hinges on the ability to generate noise that effectively activates the backdoor without significantly affecting the benign functionality of the neural network. This method shows promise for being more efficient than existing methods that focus on inversion techniques, but further research is needed to evaluate its robustness and generalization capabilities across various backdoor attack strategies and model architectures.

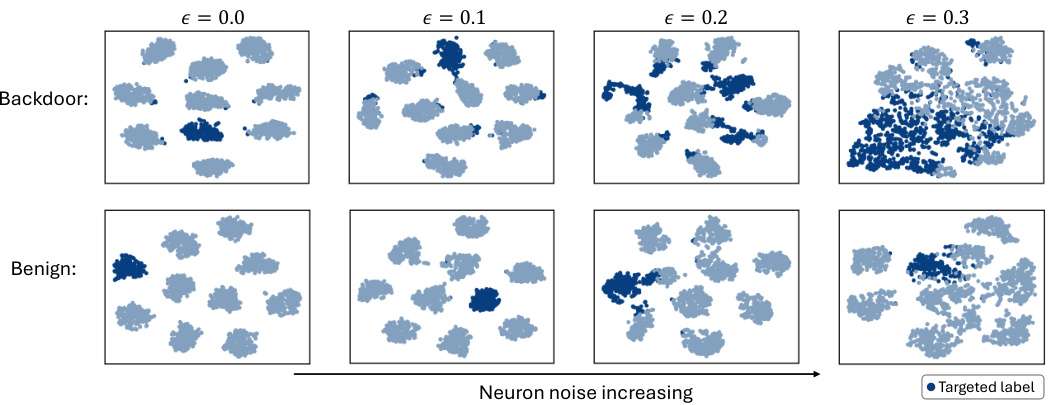

BAN Defense#

The BAN (Backdoors Activated by Adversarial Neuron Noise) defense offers a novel approach to backdoor detection in deep neural networks. Its core innovation lies in leveraging adversarial neuron noise to expose the sensitivity of backdoored models. Unlike previous methods that primarily rely on feature space analysis, BAN incorporates neuron activation information, making it more robust against various backdoor attacks, including those with less prominent features. By adversarially perturbing the model’s weights and analyzing the resulting misclassifications, BAN efficiently differentiates backdoored models from clean ones. The inclusion of feature masking further enhances the defense’s accuracy and efficiency. Experimental results demonstrate BAN’s superior performance compared to state-of-the-art defenses, achieving significant improvements in both detection accuracy and computational efficiency. However, a limitation is the dependence on having a small set of clean samples. Further research could explore how to mitigate this limitation and extend BAN’s applicability to various settings and model architectures. Overall, BAN presents a promising defense strategy against the evolving threat of backdoor attacks.

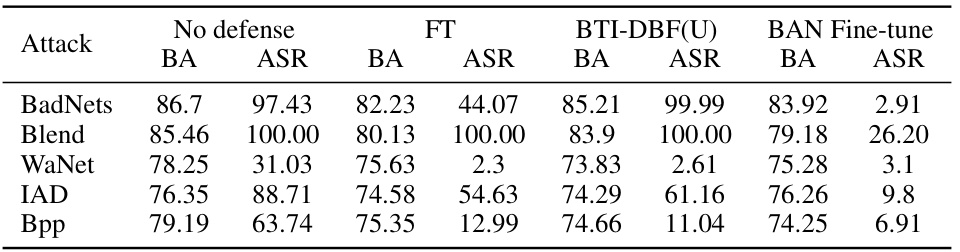

BTI-DBF Analysis#

A hypothetical ‘BTI-DBF Analysis’ section would critically examine the state-of-the-art backdoor defense, BTI-DBF, focusing on its strengths, weaknesses, and limitations. A key aspect would be evaluating its effectiveness against various backdoor attacks, noting if it struggles with specific types of triggers (e.g., input vs. feature space, static vs. dynamic). The analysis would likely investigate the computational cost of BTI-DBF, comparing its efficiency to other defenses. A crucial component would be determining if BTI-DBF overly relies on the prominence of backdoor features, potentially failing against attacks with cleverly hidden triggers. Furthermore, it would explore the generalizability of BTI-DBF across different network architectures and datasets. The section might propose potential improvements or modifications to enhance BTI-DBF’s robustness and broaden its applicability. Finally, the analysis should conclude by summarizing its performance and suggesting areas for future research.

Future Works#

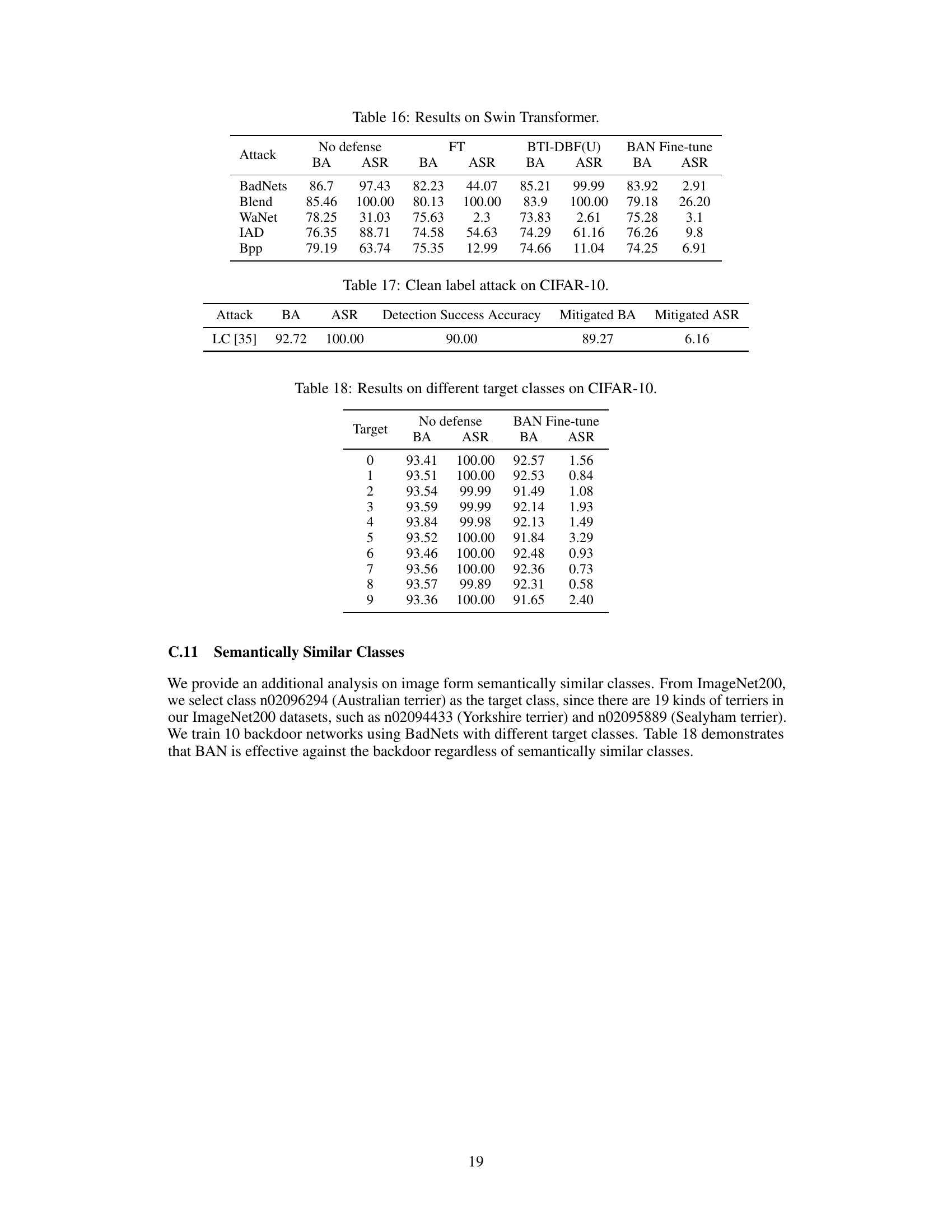

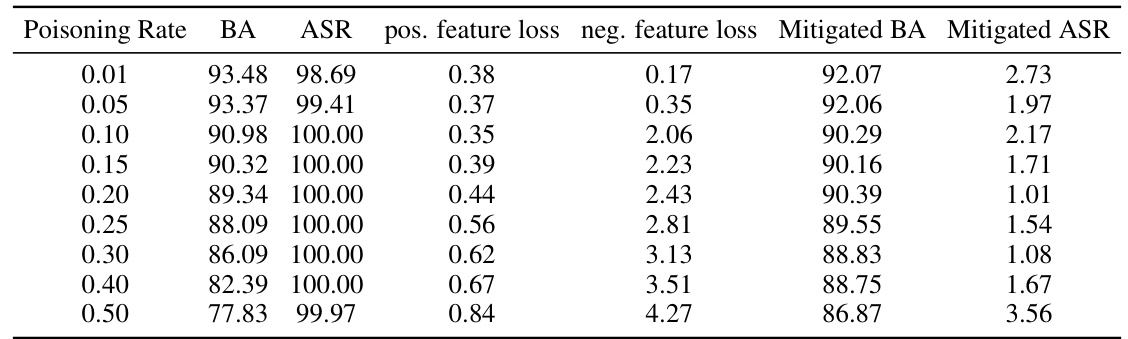

The paper’s conclusion mentions avenues for future research, focusing on improving the feature decoupling process to handle less prominent backdoor features and exploring more robust feature space detection methods. A suggestion is made to explore alternative detection methods that do not rely on access to local clean samples. Furthermore, theoretical analysis to strengthen the connection between the neuron noise method and Lipschitz continuity is proposed to enhance the defense’s effectiveness and provide deeper insights into its mechanics. Finally, the authors aim to develop a more practical detection method without the need for local clean samples, addressing a major limitation of current techniques. These future works highlight the need for continued research into more efficient and generalizable backdoor defenses.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure visualizes the feature space of backdoored and clean models under different levels of adversarial neuron noise using t-SNE. It shows how, as the neuron noise increases, backdoored models misclassify more data points from various classes as the target class, while clean models remain relatively unaffected. This difference in behavior highlights the sensitivity of backdoored models to adversarial neuron noise, a key principle exploited by the BAN defense.

This figure visualizes the effect of adversarial neuron noise on the feature space of backdoored and clean models using t-SNE. As neuron noise increases, backdoored models misclassify more data points from all classes as the target class, whereas clean models show minimal change. This difference is exploited by BAN to distinguish between backdoored and clean models.

This figure visualizes the feature space of backdoored and clean models under different levels of adversarial neuron noise using t-SNE. It shows that as the noise increases, the backdoored model misclassifies more data points as the target class, while the clean model remains relatively unaffected. This difference in behavior highlights the effectiveness of adversarial neuron noise in detecting backdoors.

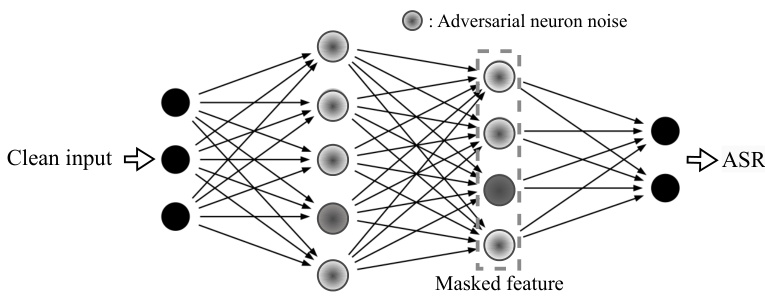

This figure provides a visual representation of the BAN (Backdoors Activated by Adversarial Neuron Noise) method. It shows a simplified neural network where a clean input is processed. Adversarial neuron noise is added to the network, particularly affecting the weights of certain neurons. The output of a subset of neurons (masked feature) is then used in the subsequent layers, along with the adversarial noise, to determine the attack success rate (ASR). The darker shaded neurons in the figure represent the targeted neurons that are manipulated by the adversarial noise.

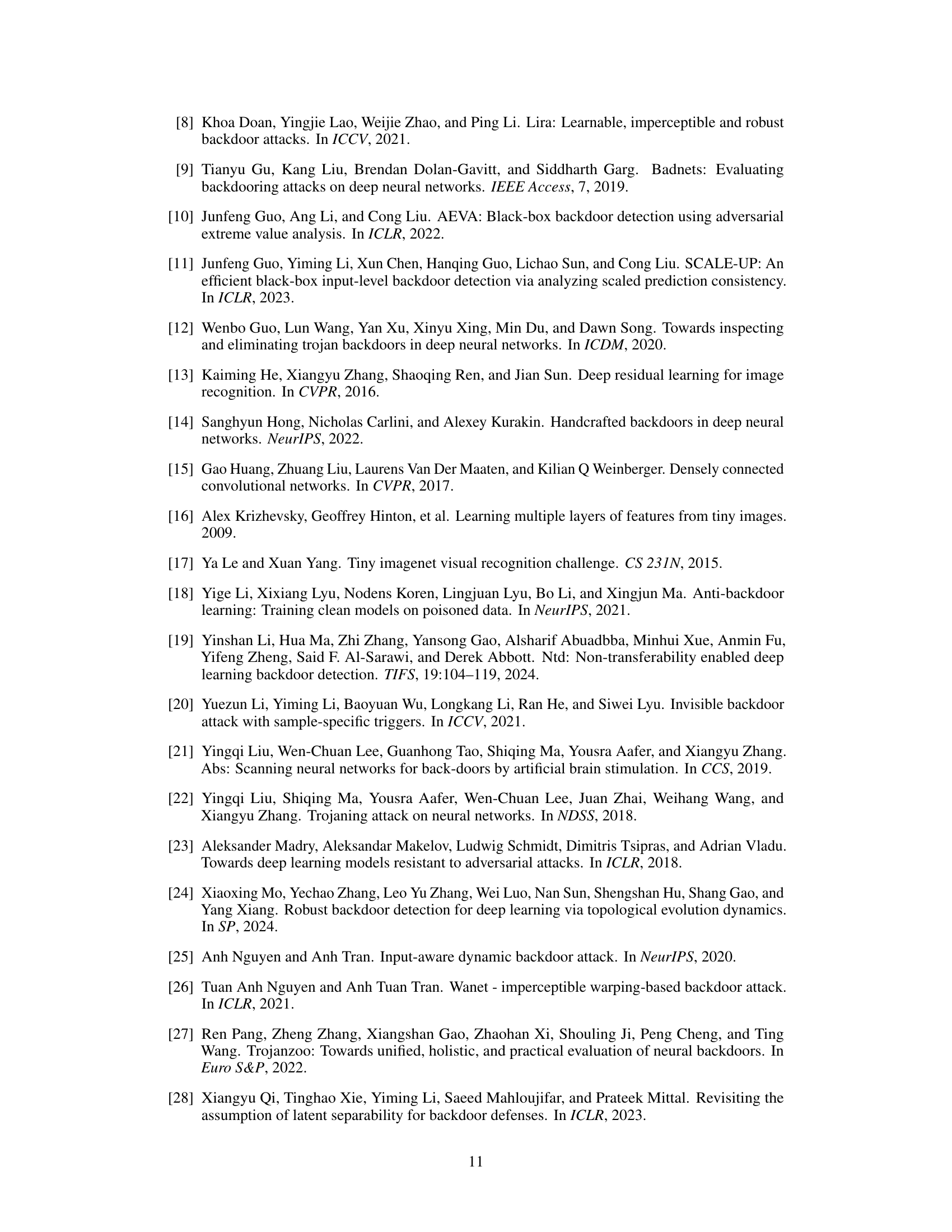

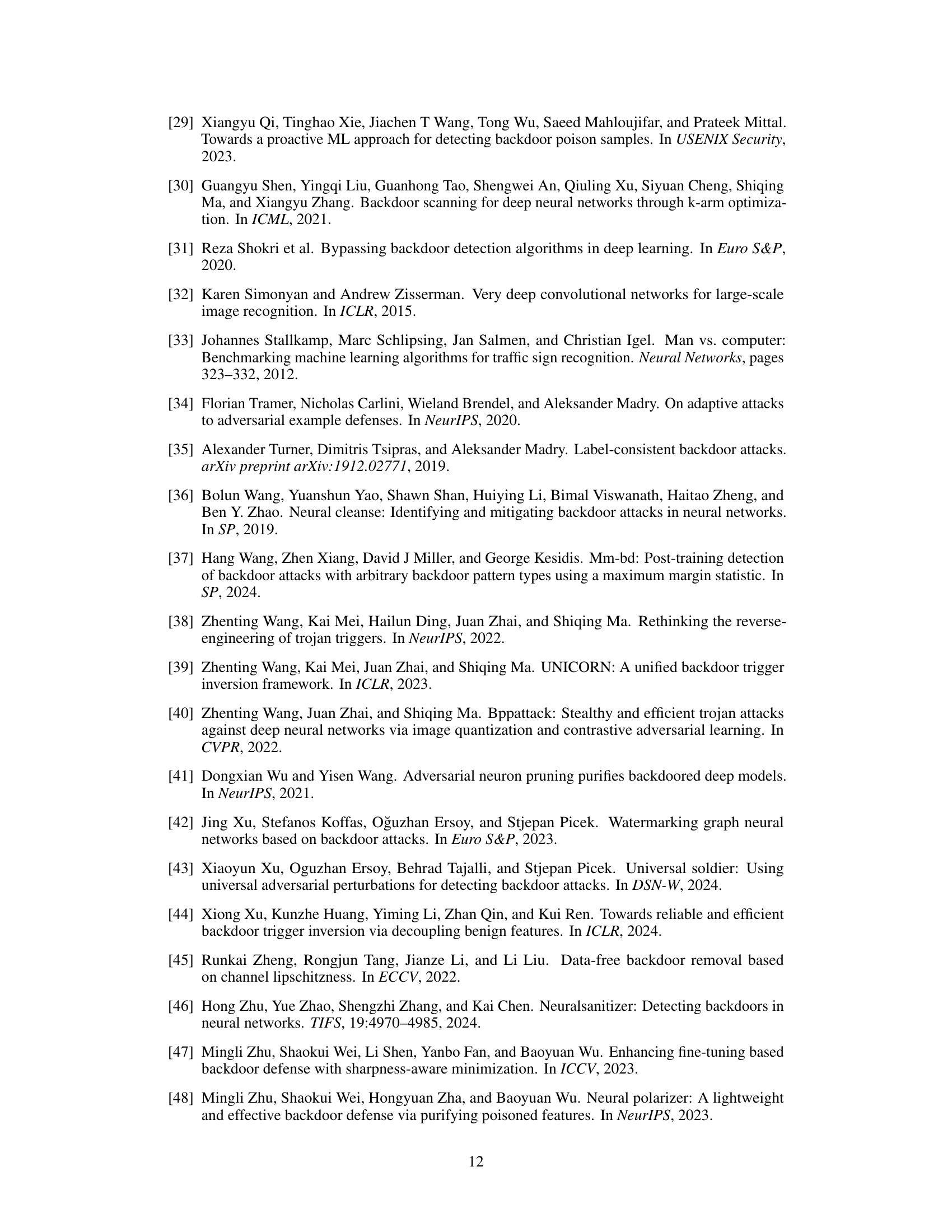

More on tables

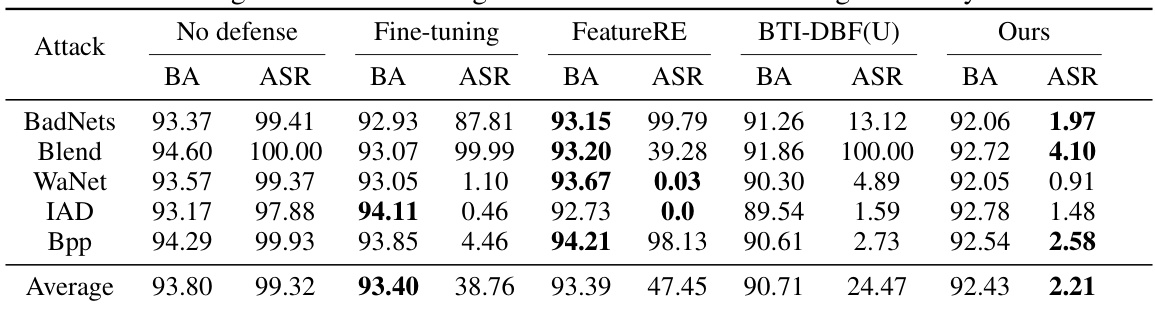

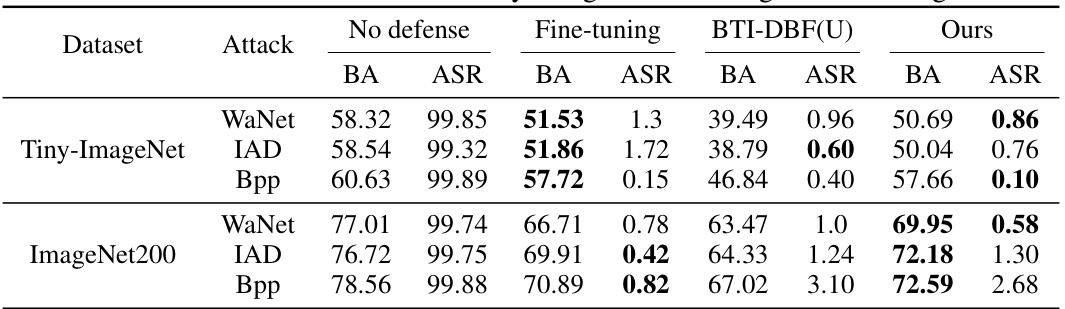

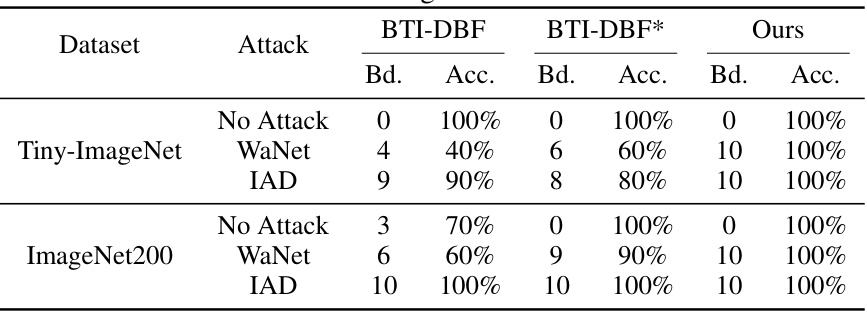

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). It compares the performance of six different defense methods (NC, Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, BTI-DBF, and the proposed BAN method) against several different attack methods (No Attack, BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, and Bpp). For each combination of defense method, attack method, and model architecture, the table indicates the number of models correctly identified as backdoored (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of the detection (‘Acc.’). The best results for each setting are highlighted in bold.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). The table compares the performance of several backdoor detection methods, including Neural Cleanse (NC), Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, BTI-DBF, and the proposed BAN method. For each method and each attack type (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, and Bpp), the number of models correctly identified as backdoored (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of the detection (‘Acc.’) are reported. BTI-DBF* represents a modified version of the BTI-DBF method, and the table highlights the best performance achieved by each method for each attack.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). It compares the performance of several backdoor detection methods, including Neural Cleanse (NC), Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, and the improved version of BTI-DBF (BTI-DBF*). For each attack type and model architecture, the table shows the number of backdoored models correctly identified (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of the detection (‘Acc.’). The comparison allows evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of different detection methods against various backdoor attacks.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments performed on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). Several backdoor attacks (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, and Bpp) were tested against five different defense methods (Neural Cleanse, Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, and BTI-DBF), as well as the proposed BAN method. The table shows, for each attack and defense method, the number of backdoored models correctly identified and the overall accuracy of the detection. The results highlight the superior performance of the BAN method compared to state-of-the-art defense techniques.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments performed on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). The table compares the performance of several backdoor detection methods (NC, Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, BTI-DBF*, and the proposed BAN method) against various backdoor attacks (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, and Bpp). For each method and attack, the table shows the number of backdoored models correctly identified (Bd.) and the detection accuracy (Acc.). The BTI-DBF* entry refers to an improved version of the BTI-DBF method described in Section 3.4 of the paper.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments conducted on CIFAR-10 using three different model architectures: ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121. The effectiveness of several defense methods, including Neural Cleanse (NC), Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, BTI-DBF, BTI-DBF* (an improved version), and the proposed BAN method, are compared against various backdoor attacks. The table shows the number of models correctly identified as backdoored (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of detection (‘Acc.’) for each defense method and attack combination.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments conducted on CIFAR-10 using different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). Several backdoor attacks (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, Bpp) were tested, alongside a ‘No Attack’ control group. For each architecture and attack, the table shows the number of models identified as backdoored (‘Bd.’) and the detection accuracy (‘Acc.’). The table compares the proposed BAN method to several existing backdoor detection methods (NC, Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, BTI-DBF, and an improved version of BTI-DBF called BTI-DBF*). The best detection performance for each setting is highlighted in bold.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). The table compares the performance of several backdoor detection methods: Neural Cleanse (NC), Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, BTI-DBF, and the proposed BAN method. For each attack type and architecture, the table shows the number of models correctly identified as backdoored (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of the detection (‘Acc.’). The ‘No Attack’ row provides the baseline results for non-backdoored models, while the other rows show results for different attack types (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, and Bpp). BTI-DBF* represents a modified version of the BTI-DBF method.

This table presents the performance of different backdoor detection methods (Neural Cleanse, Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, BTI-DBF, and the proposed BAN method) on CIFAR-10 dataset using three different architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). For each method, it shows the number of backdoored models correctly identified (‘Bd.’) and the detection accuracy (‘Acc.’). The results are shown for various backdoor attacks (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, Bpp). BTI-DBF* represents an improved version of the BTI-DBF method.

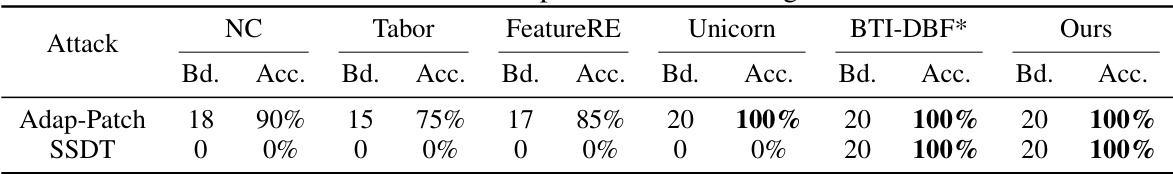

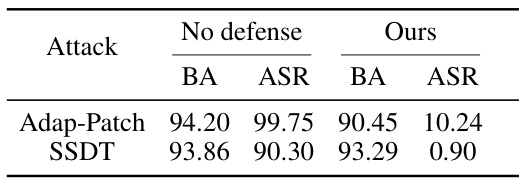

This table presents the detection results of different defense methods against two adaptive backdoor attacks: Adap-Blend and SSDT. Adap-Blend obscures the difference between benign and backdoor features by randomly applying 50% of the trigger during data poisoning. SSDT uses source-specific and dynamic triggers to reduce the impact of triggers on samples from non-victim classes. The table shows the detection success rate (Bd. Acc.) for different methods and how they perform against these adaptive attacks.

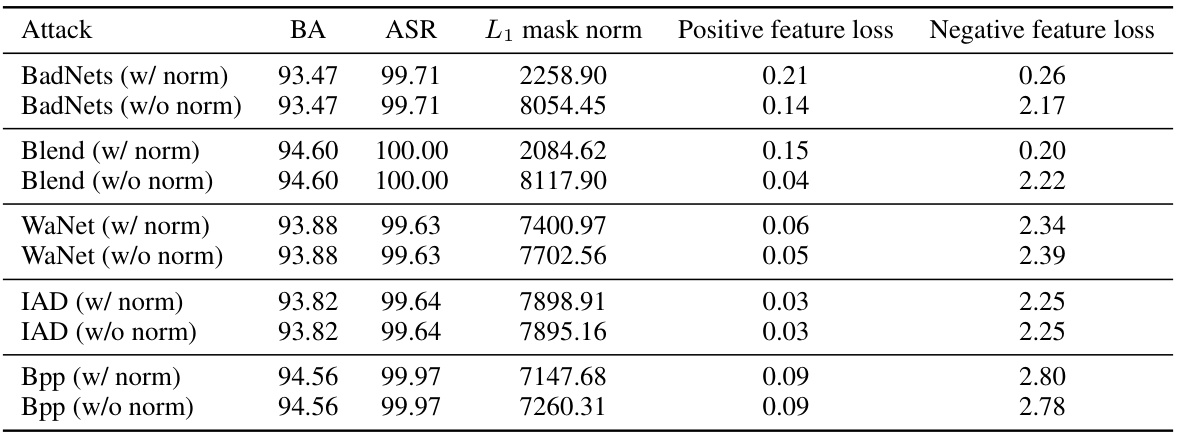

This table presents a comparison of the backdoor detection performance between the original BTI-DBF method and the improved version (BTI-DBF*) proposed in the paper, along with the results of the BAN method. It shows the number of backdoored models identified and the accuracy of detection for different types of attacks, including BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, and Bpp. The results highlight the improved detection capabilities of BTI-DBF* and the superior performance of BAN.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). It compares the performance of several backdoor detection methods, including the proposed BAN method, against various backdoor attacks. The table shows the number of models correctly identified as backdoored (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of the detection (‘Acc.’) for each method. The best performing method for each attack and architecture is highlighted in bold. An improved version of the BTI-DBF method (BTI-DBF*) is also included in the comparison.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). Multiple backdoor attacks (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, and Bpp) were tested, along with a ‘No Attack’ baseline. The table shows the number of backdoored models correctly identified (Bd.) and the accuracy of the detection (Acc.) for each attack and model architecture. The performance of the proposed BAN method is compared against several existing defense methods: Neural Cleanse (NC), Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, and BTI-DBF, as well as an improved version of BTI-DBF called BTI-DBF*.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). It compares the performance of BAN against several other state-of-the-art backdoor detection methods (NC, Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, and BTI-DBF) across various backdoor attacks. For each method and attack, the table shows the number of models correctly identified as backdoored and the overall accuracy of the detection.

This table presents the performance of different backdoor detection methods (Neural Cleanse, Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, BTI-DBF, and BAN) on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). For each method and architecture, it shows the number of backdoored models correctly identified and the overall detection accuracy. The results are broken down by different attack types (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAD, Bpp). BTI-DBF* represents a modified version of the BTI-DBF method.

This table presents the results of backdoor detection experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures (ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121). Several backdoor attacks were tested, and the table shows the number of models correctly identified as backdoored (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of the detection (‘Acc.’) for each method. The performance of BAN is compared to several state-of-the-art defense methods, including Neural Cleanse (NC), Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, and BTI-DBF (with an improved version, BTI-DBF*, also included for comparison).

This table presents the results of the backdoor detection experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three different model architectures: ResNet18, VGG16, and DenseNet121. It compares the performance of BAN against several other state-of-the-art defense methods (NC, Tabor, FeatureRE, Unicorn, and BTI-DBF). The table shows the number of models each defense method correctly identified as backdoored (‘Bd.’) and the accuracy of the detection (‘Acc.’). The results are categorized by the type of attack used to create the backdoored model.

Full paper#