TL;DR#

Batched best arm identification (BBAI) is crucial for various applications where sequential testing is infeasible. Existing algorithms often compromise either sample or batch complexity or lack finite confidence guarantees, leading to potentially unbounded complexities. This paper introduces Tri-BBAI and Opt-BBAI, two novel algorithms that address these limitations.

Tri-BBAI achieves the optimal sample complexity in the asymptotic setting (when the desired probability of success approaches 1) within a constant (3) number of batches. Opt-BBAI extends this success to the non-asymptotic setting, achieving near-optimal sample and batch complexities for a fixed confidence level. Crucially, Opt-BBAI’s complexity is bounded even if a sub-optimal arm is returned, unlike previous methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in online decision-making and machine learning. It provides efficient algorithms for batched best-arm identification (BBAI), a problem with significant real-world applications but lacking optimal solutions. The novel approach guarantees optimal asymptotic sample complexity with a constant number of batches, surpassing existing methods. This work opens avenues for future research in adaptive algorithms and resource-efficient bandit strategies, particularly where sequential approaches are impractical.

Visual Insights#

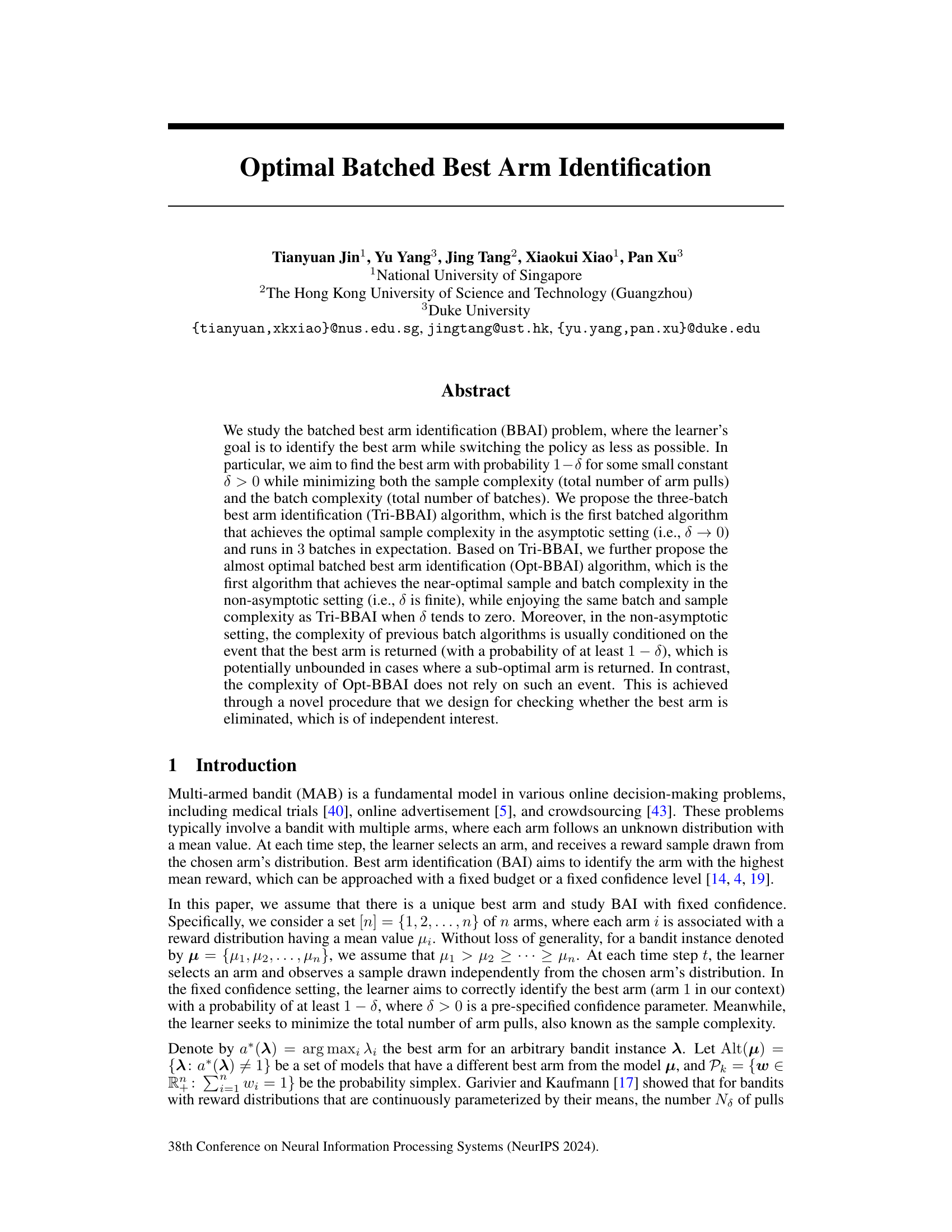

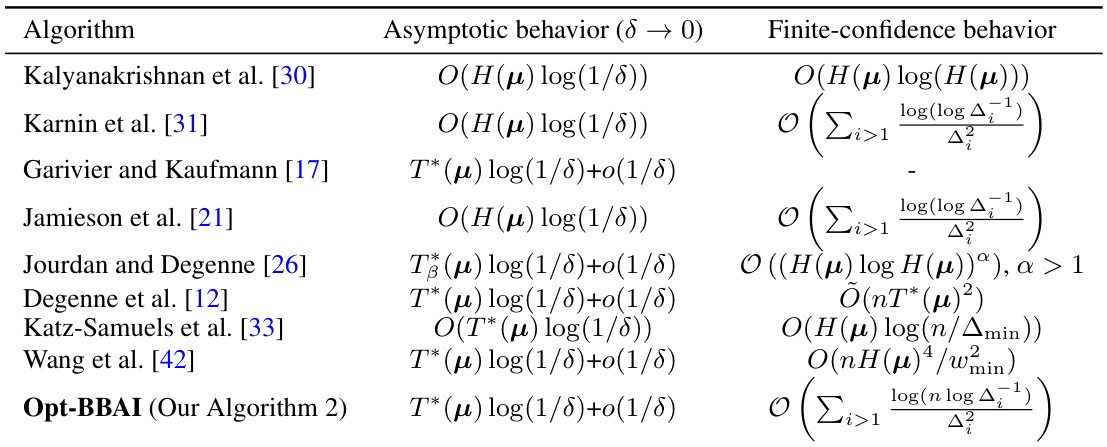

🔼 Algorithm 2 presents the Opt-BBAI algorithm, which refines the Tri-BBAI algorithm by incorporating an ‘Exploration with Exponential Gap Elimination’ stage (Stage IV). This stage iteratively eliminates sub-optimal arms until the best arm is identified. It combines ‘Successive Elimination’ to remove clearly inferior arms and ‘Checking for Best Arm Elimination’ to mitigate the risk of prematurely discarding the best arm. The algorithm dynamically adjusts parameters based on the confidence level (δ) to achieve near-optimal performance in both asymptotic and non-asymptotic settings.

read the caption

Algorithm 2: (Almost) Optimal Batched Best Arm Identification (Opt-BBAI)

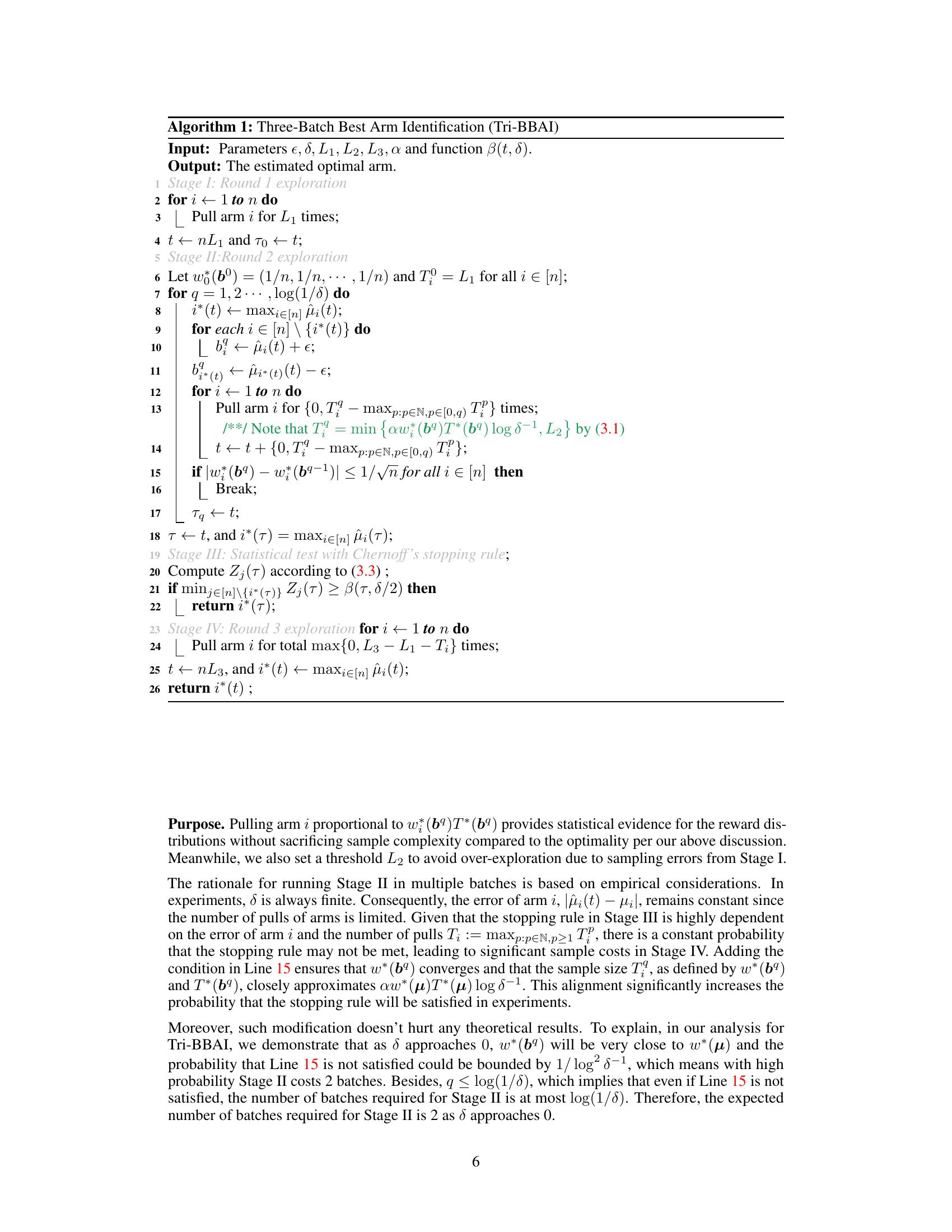

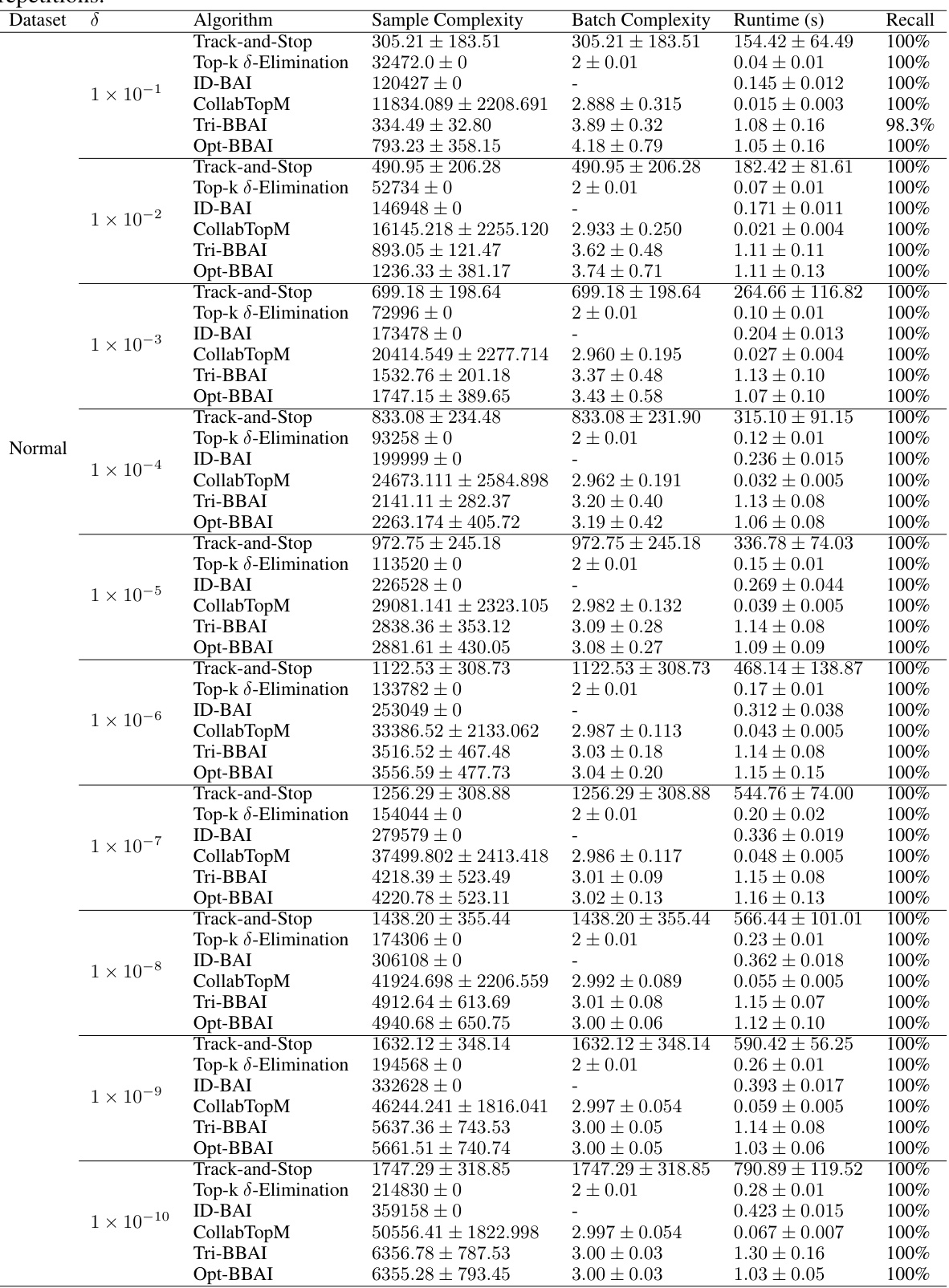

🔼 This table compares the sample and batch complexities of various best arm identification (BAI) algorithms, both in the asymptotic setting (δ approaching 0) and for finite confidence levels. It highlights the optimality of sample complexity (number of arm pulls) and shows the batch complexity (number of times the policy is switched). A key distinction is made between algorithms whose sample complexity is conditional on successfully finding the best arm (potentially unbounded if a suboptimal arm is returned) and those whose complexity is the total expected number of pulls.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of sample and batch complexity of different algorithms. In the asymptotic setting (i.e., δ → 0), the sample complexity of an algorithm is optimal if it satisfies the definition in (1.3). The field marked with “–” indicates that the result is not provided. The sample complexity presented for [31, 22] is conditioned on the event that the algorithm returns the best arm, which can be unbounded when it returns a sub-optimal arm with certain (non-zero) probability (see Remark 4.4 for more details). In contrast, the sample complexity presented for [17, 26] and our algorithms is the total expected number of pulls that will be executed.

In-depth insights#

Batched BAI Problem#

The batched best-arm identification (BAI) problem is a crucial extension of the standard BAI framework, addressing scenarios where feedback is not immediate. Unlike traditional BAI, which operates sequentially, the batched version involves grouping arm pulls into batches, with feedback only revealed after each batch’s completion. This introduces unique challenges, such as minimizing both the total number of pulls (sample complexity) and the number of batches (batch complexity). The paper explores algorithms that strive for asymptotic optimality (as the error probability goes to zero) and near-optimality in non-asymptotic settings, making them practical for real-world applications. A key innovation is a novel procedure for checking best arm elimination, enhancing robustness and handling cases where suboptimal arms are returned. The study balances theoretical analysis with empirical evaluations, highlighting the trade-offs between optimal sample and batch complexities, offering valuable insights for various online decision-making domains. The problem is particularly relevant in parallel computing and applications with inherent delays, impacting algorithm design and performance analysis.

Tri-BBAI Algorithm#

The Tri-BBAI algorithm, a novel approach to batched best-arm identification, is designed to minimize both sample and batch complexities while ensuring high probability of success. Its core innovation lies in its three-stage structure, cleverly balancing exploration and exploitation. The initial exploration phase efficiently gathers preliminary information. The subsequent exploration stage leverages a refined sampling strategy based on Kullback-Leibler divergence to achieve near-optimal sample complexity. Finally, a statistical test using Chernoff’s stopping rule decides when to halt, minimizing unnecessary pulls. This intelligent design results in a method that is asymptotically optimal, achieving optimal sample complexity as the confidence parameter approaches zero, while maintaining a constant number of batches in expectation. The Tri-BBAI algorithm significantly advances the state-of-the-art in batched best-arm identification, providing a practical and efficient solution to real-world problems where sequential arm pulls are not feasible.

Opt-BBAI Algorithm#

The Opt-BBAI algorithm represents a significant advancement in batched best-arm identification (BBAI). It aims to achieve near-optimal sample and batch complexities in both asymptotic and non-asymptotic settings. This is a crucial improvement over existing algorithms, which often achieve optimality only asymptotically (as the confidence parameter approaches zero) or suffer from unbounded complexities in non-asymptotic settings. Opt-BBAI builds upon Tri-BBAI, leveraging its three-batch asymptotic optimality while incorporating a novel procedure to address the potential issue of unbounded complexities when the best arm isn’t identified. This procedure carefully checks whether the best arm has been eliminated, avoiding the unbounded complexities that plagued earlier approaches. By adapting to the specific confidence level, Opt-BBAI offers a practical and theoretically sound solution for BBAI, bridging the gap between theoretical optimality and real-world applicability. Its adaptive nature and near-optimal complexities make it a powerful tool for various BBAI applications where minimizing both sample and batch complexity is vital.

Asymptotic Optimality#

Asymptotic optimality, in the context of best arm identification (BAI) algorithms, refers to the theoretical guarantee that an algorithm’s sample complexity (number of arm pulls) approaches the optimal lower bound as the confidence parameter (δ) tends to zero. This means that as the desired probability of success increases (δ decreases), the algorithm’s efficiency in finding the best arm approaches the theoretical limit; it does not guarantee optimal performance for any finite δ. The focus is on the limiting behavior, providing valuable insights into algorithm scalability and efficiency. Achieving asymptotic optimality often involves sophisticated techniques such as carefully balancing exploration and exploitation, and may not necessarily translate to superior performance in practical scenarios with finite δ, where non-asymptotic bounds become more critical for evaluation. While elegant theoretically, the practical utility of asymptotic results is often limited; it’s crucial to consider non-asymptotic performance measures for real-world applicability.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this batched best-arm identification (BBAI) work could involve exploring tighter bounds on sample and batch complexities for finite confidence levels. Addressing the gap between theoretical optimality and practical performance in non-asymptotic settings is crucial. Investigating the algorithm’s robustness to various reward distribution assumptions beyond exponential families would enhance its applicability. Furthermore, adapting the proposed techniques to more complex bandit settings, such as linear bandits or those with dependent arms, is a promising avenue. Finally, developing efficient parallel implementations and exploring the potential for distributed BBAI are key areas for practical impact.

More visual insights#

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the sample and batch complexity of various best arm identification algorithms, highlighting the differences between asymptotic and finite-confidence settings. It notes that some algorithms’ sample complexities are only optimal given the best arm is returned, which is not always guaranteed.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of sample and batch complexity of different algorithms. In the asymptotic setting (i.e., δ → 0), the sample complexity of an algorithm is optimal if it satisfies the definition in (1.3). The field marked with “–” indicates that the result is not provided. The sample complexity presented for [31, 22] is conditioned on the event that the algorithm returns the best arm, which can be unbounded when it returns a sub-optimal arm with certain (non-zero) probability (see Remark 4.4 for more details). In contrast, the sample complexity presented for [17, 26] and our algorithms is the total expected number of pulls that will be executed.

🔼 This table compares the sample and batch complexities of various best arm identification algorithms, highlighting the differences in their asymptotic and finite-confidence behaviors. It notes that some algorithms’ sample complexities are conditional on successfully identifying the best arm, potentially leading to unbounded values if a sub-optimal arm is selected. In contrast, the complexities reported for other algorithms, including the authors’ proposed ones, represent the total expected number of arm pulls.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of sample and batch complexity of different algorithms. In the asymptotic setting (i.e., δ → 0), the sample complexity of an algorithm is optimal if it satisfies the definition in (1.3). The field marked with “–” indicates that the result is not provided. The sample complexity presented for [31, 22] is conditioned on the event that the algorithm returns the best arm, which can be unbounded when it returns a sub-optimal arm with certain (non-zero) probability (see Remark 4.4 for more details). In contrast, the sample complexity presented for [17, 26] and our algorithms is the total expected number of pulls that will be executed.

🔼 This table compares the sample and batch complexities of various best arm identification algorithms, both in the asymptotic (δ→0) and finite-confidence settings. It highlights which algorithms achieve optimal or near-optimal sample complexity and notes that some prior work’s sample complexity is only guaranteed when the best arm is returned (otherwise it can be unbounded).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of sample and batch complexity of different algorithms. In the asymptotic setting (i.e., δ → 0), the sample complexity of an algorithm is optimal if it satisfies the definition in (1.3). The field marked with “–” indicates that the result is not provided. The sample complexity presented for [31, 22] is conditioned on the event that the algorithm returns the best arm, which can be unbounded when it returns a sub-optimal arm with certain (non-zero) probability (see Remark 4.4 for more details). In contrast, the sample complexity presented for [17, 26] and our algorithms is the total expected number of pulls that will be executed.

Full paper#