TL;DR#

Many real-world machine learning tasks involve large-scale optimization problems solved using distributed computing. However, distributed systems often suffer from device heterogeneity and asynchronous computations, leading to significant performance bottlenecks and suboptimal results. Existing methods struggle to handle these challenges effectively, often lacking theoretical guarantees or making overly restrictive assumptions. This paper addresses this challenge head-on.

The paper introduces Freya PAGE, a novel parallel optimization method designed to overcome these issues. Freya PAGE is robust to slow devices, adapts effectively to varying computation times, and achieves optimal time complexity. The theoretical analysis rigorously demonstrates the optimality of Freya PAGE in large-scale settings. The paper also provides generic gradient collection strategies that are valuable beyond Freya PAGE, as well as a new lower bound for the time complexity of asynchronous optimization in such settings. This significant contribution advances the state-of-the-art in distributed machine learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on large-scale machine learning because it presents an optimal solution for nonconvex finite-sum optimization in heterogeneous and asynchronous distributed systems. This is a significant advance given the real-world complexities of distributed computing, where devices and network conditions vary considerably. The paper’s optimal algorithm, Freya PAGE, and its theoretical guarantees are highly relevant to current trends and open up several new avenues for research. It also provides a fundamental time complexity limit that guides further developments in the field.

Visual Insights#

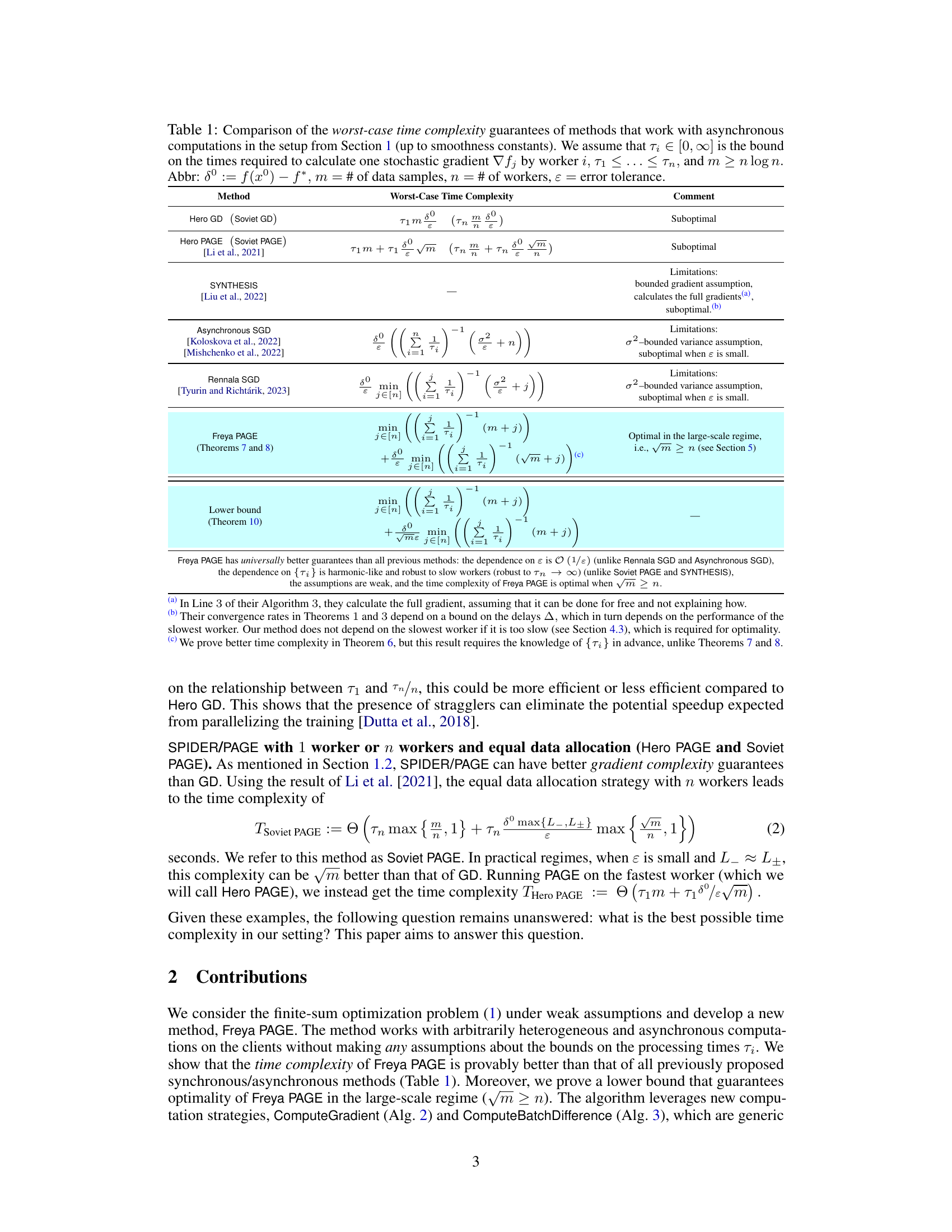

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Freya PAGE, Rennala SGD, Soviet PAGE, and Asynchronous SGD on nonconvex quadratic optimization tasks. The x-axis represents the time elapsed in seconds, and the y-axis shows the function suboptimality (f(x_t) - f(x*)). The plots demonstrate the convergence behavior of each algorithm over time. Two plots are shown: one with 1000 workers (n=1000) and another with 10000 workers (n=10000), illustrating how the performance changes with an increase in the number of workers.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experiments with nonconvex quadratic optimization tasks. We plot function suboptimality against elapsed time.

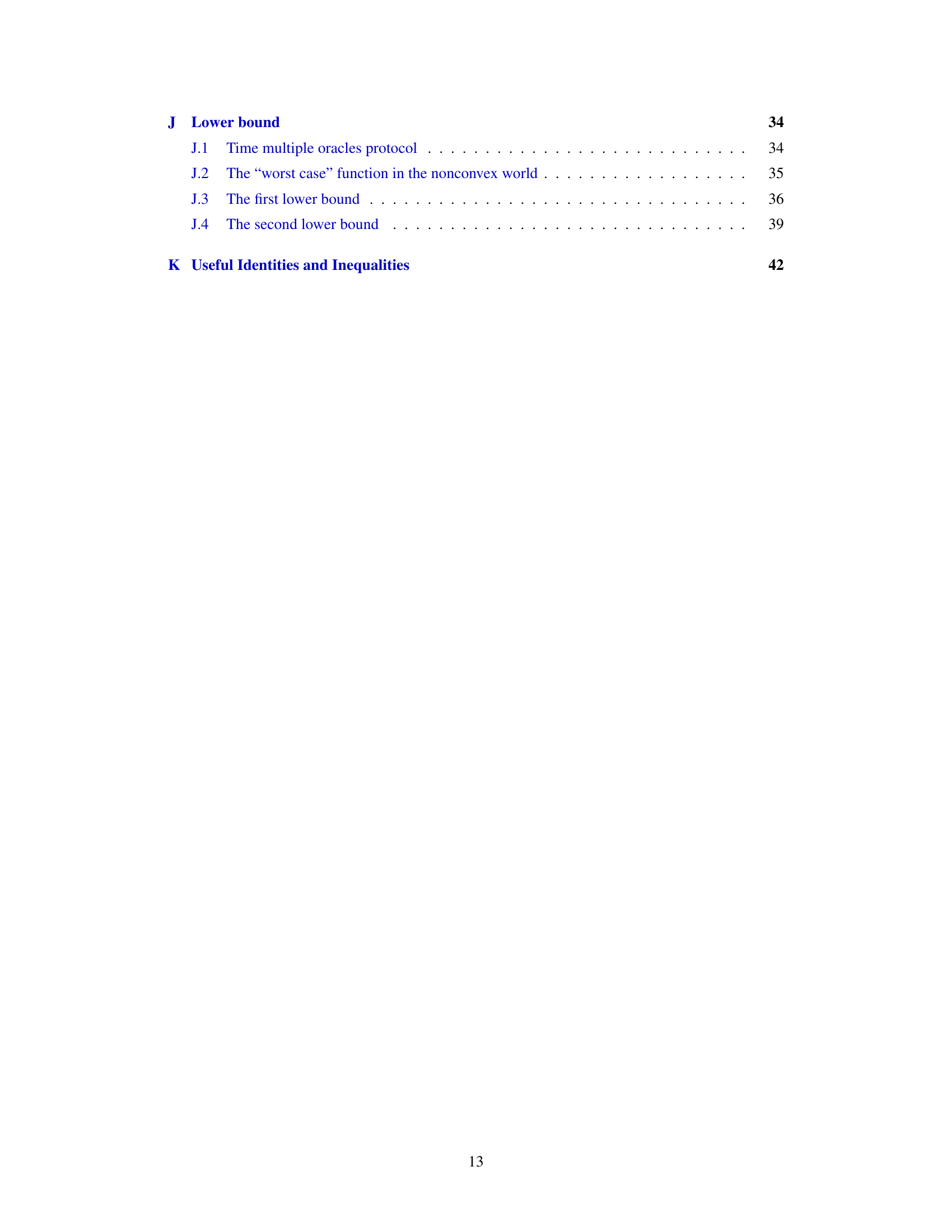

🔼 This table compares the worst-case time complexity of various asynchronous optimization methods for solving finite-sum nonconvex optimization problems. It considers the impact of heterogeneous worker speeds and asynchronous computation, highlighting the limitations of prior methods and demonstrating the optimality of Freya PAGE in large-scale settings (where the number of data samples is significantly larger than the number of workers).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the worst-case time complexity guarantees of methods that work with asynchronous computations in the setup from Section 1 (up to smoothness constants). We assume that Ti ∈ [0,∞] is the bound on the times required to calculate one stochastic gradient ∇fi by worker i, T1 < ... < Tn, and m > n log n. Abbr: δ° := f(xº) − f*, m = # of data samples, n = # of workers, ɛ = error tolerance.

In-depth insights#

Async. Optimization#

Asynchronous optimization methods address the challenges of distributed computing environments where worker nodes may have varying processing speeds and communication delays. The core idea is to allow workers to proceed independently, updating model parameters without waiting for others to finish their computations. This contrasts with synchronous methods that require global synchronization at each iteration, leading to potential bottlenecks and reduced efficiency. Key benefits of asynchronous methods include increased throughput and robustness to stragglers (slow workers). However, the asynchronous nature introduces complexities in convergence analysis, as the model is constantly being updated with potentially stale gradients. Careful design and analysis are crucial to guarantee convergence and to achieve efficient performance. Recent research has focused on variance reduction techniques and novel gradient aggregation strategies to mitigate the issues of stale gradients and to improve convergence rates in asynchronous settings. Optimal algorithms aim to balance the trade-off between speed and accuracy.

FreyaPAGE Algorithm#

The FreyaPAGE algorithm presents a novel approach to large-scale nonconvex finite-sum optimization within the context of heterogeneous asynchronous computations. Its key strength lies in its robustness to stragglers, effectively mitigating the impact of slow-performing workers on overall convergence time. This is achieved through adaptive gradient collection strategies that intelligently leverage available resources, focusing computation on faster workers. Theoretical analysis demonstrates optimality in the large-scale regime (√m ≥ n), showcasing improved time complexity compared to existing methods like Asynchronous SGD and PAGE. The algorithm’s weak assumptions about worker heterogeneity and asynchronous operations make it widely applicable in real-world distributed systems. However, further investigation into its performance under various data distributions and different levels of worker heterogeneity would enhance its practical applicability and validate the theoretical claims more comprehensively.

Time Complexity#

The analysis of time complexity in this research paper is a crucial aspect, focusing on the efficiency of distributed optimization algorithms in heterogeneous asynchronous settings. The authors introduce a novel method, Freya PAGE, and demonstrate its superior time complexity compared to existing methods. A key strength of their approach is its robustness to stragglers, adaptively ignoring slow computations to achieve improved performance. The paper establishes a lower bound for asynchronous optimization, proving that Freya PAGE’s complexity is optimal in the large-scale regime. This optimality is proven mathematically using a combination of theoretical analysis and carefully designed algorithms that optimize gradient computation and data allocation amongst worker nodes. The large-scale regime assumption highlights a practical limitation of the study. The discussion of various strategies used to collect gradients, with different time complexities, is insightful. However, the detailed analysis and proof of optimality might require further study for full comprehension.

Heterogeneous Workers#

The concept of “Heterogeneous Workers” in distributed computing, particularly relevant to machine learning, acknowledges the reality that computational units (workers) in a system may have vastly different processing capabilities and speeds. This heterogeneity arises from factors such as varying hardware configurations (CPU/GPU differences, memory limitations), network conditions (latency, bandwidth), and even software implementations. Ignoring worker heterogeneity leads to suboptimal performance, as slow workers (stragglers) become bottlenecks, hindering overall training speed and efficiency. Addressing this requires algorithms robust to stragglers, such as those that can adaptively ignore slow computations or employ strategies to balance workload distribution effectively. Efficient stochastic gradient collection mechanisms are essential to handle the asynchronous nature inherent in heterogeneous environments, ensuring that updates are incorporated without unnecessary delays caused by slow workers. The design of such robust algorithms requires novel techniques, beyond traditional synchronous approaches, focusing on adaptive sampling and effective synchronization strategies. In summary, research into “Heterogeneous Workers” is critical for developing scalable and efficient parallel machine learning algorithms that can leverage diverse computing resources effectively and robustly in real-world deployments.

Optimal Convergence#

Optimal convergence in machine learning research signifies achieving the best possible rate at which a model’s performance improves during training. It’s a crucial aspect for evaluating algorithms’ efficiency, especially in large-scale applications where training time is a significant constraint. Analysis of optimal convergence often involves rigorous mathematical proof, establishing upper bounds on the number of iterations or computational steps required to reach a target level of accuracy. These proofs usually rely on specific assumptions about the data, model, and algorithm, such as convexity or smoothness of the objective function. Furthermore, lower bounds are also studied to demonstrate that an algorithm’s convergence rate is fundamentally optimal or close to optimal. Research into optimal convergence often explores different optimization techniques, such as stochastic gradient descent variants or variance reduction methods, examining how each algorithm’s theoretical properties impact its speed of convergence. Ultimately, the goal is to develop algorithms that converge as rapidly as theoretically possible, minimizing training time and resource consumption.

More visual insights#

More on figures

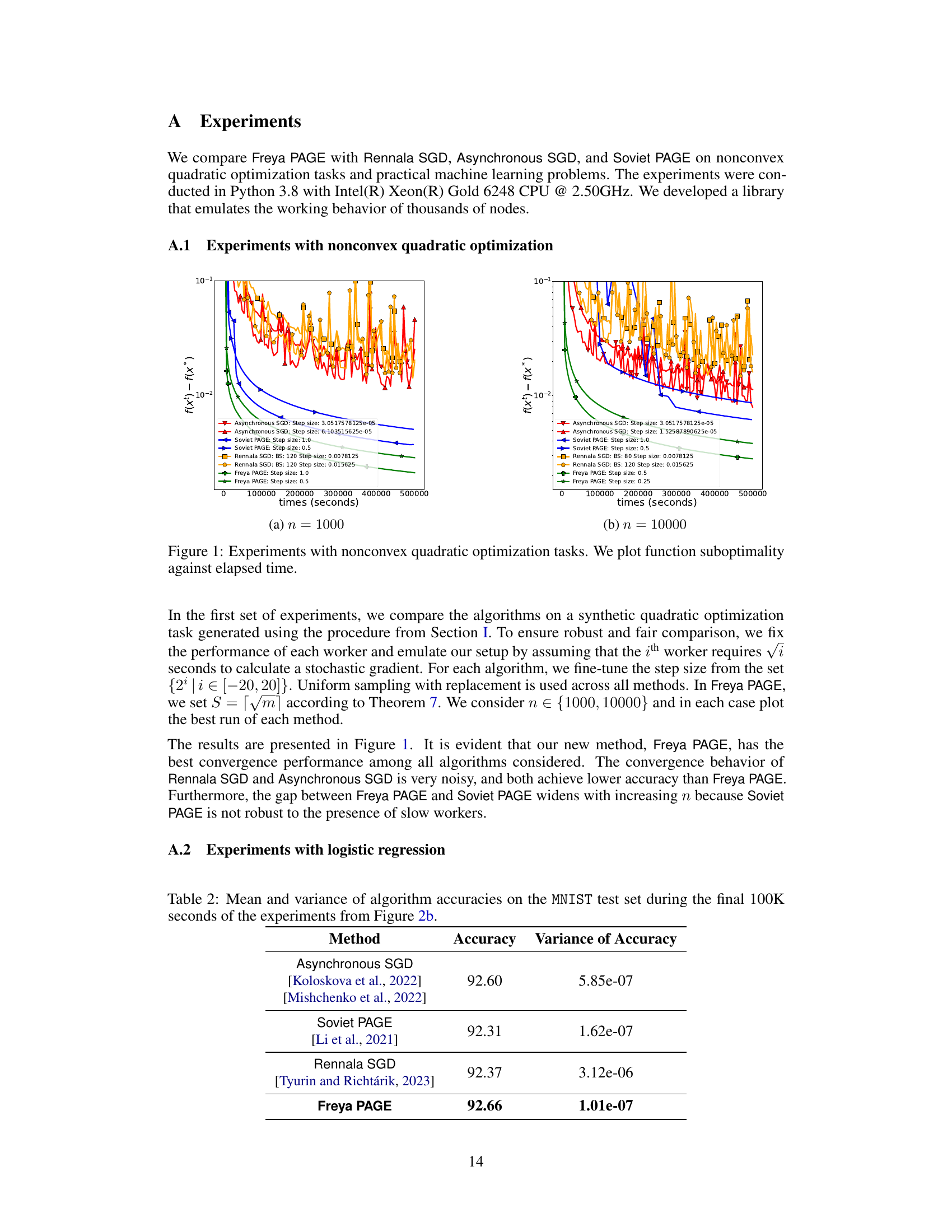

🔼 The figure shows the results of experiments comparing the performance of several optimization algorithms on synthetic nonconvex quadratic optimization tasks. The x-axis represents time in seconds, and the y-axis represents the function suboptimality, measuring how far the algorithm’s current solution is from the optimal solution. Multiple lines represent different algorithms (Asynchronous SGD, Soviet PAGE, Rennala SGD, Freya PAGE) with different hyperparameter settings (step sizes, batch sizes). The plot visualizes the convergence speed and stability of each algorithm, indicating Freya PAGE’s superior performance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experiments with nonconvex quadratic optimization tasks. We plot function suboptimality against elapsed time.

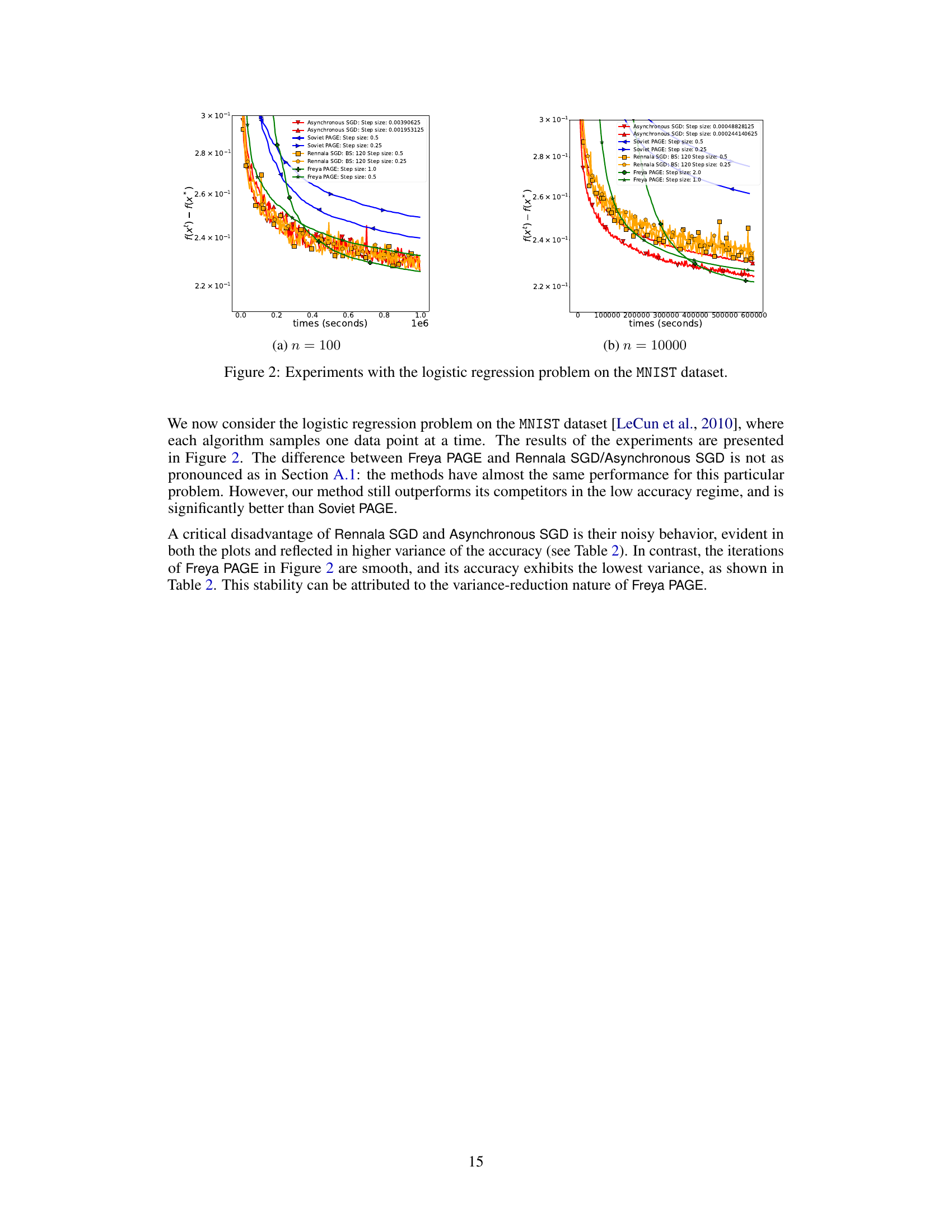

🔼 The figure shows the results of the logistic regression experiments on the MNIST dataset with different numbers of workers (n = 100 and n = 10000). The x-axis represents the time in seconds, and the y-axis represents the function suboptimality (f(xt) - f(x*)). The plot compares the performance of Freya PAGE against Rennala SGD, Asynchronous SGD, and Soviet PAGE. It demonstrates that Freya PAGE achieves better convergence and lower function suboptimality, especially as the number of workers increases. The plots also highlight the noisy behavior of Asynchronous SGD and Rennala SGD.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiments with the logistic regression problem on the MNIST dataset.

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the time complexity of various algorithms for solving nonconvex finite-sum optimization problems with asynchronous and heterogeneous workers. It shows how the worst-case time complexity depends on the number of data samples (m), number of workers (n), error tolerance (ɛ), and the slowest worker’s computation time (Tn). The table highlights the optimality of the Freya PAGE algorithm in the large-scale regime (√m ≥ n).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the worst-case time complexity guarantees of methods that work with asynchronous computations in the setup from Section 1 (up to smoothness constants). We assume that Ti ∈ [0,∞] is the bound on the times required to calculate one stochastic gradient ∇fi by worker i, T₁ < ... < Tn, and m > n log n.

🔼 This table compares the time complexity of various algorithms for solving non-convex finite-sum optimization problems with asynchronous and heterogeneous workers. It shows that Freya PAGE has better time complexity than other methods in the large-scale regime (when the number of data samples is much larger than the number of workers).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the worst-case time complexity guarantees of methods that work with asynchronous computations in the setup from Section 1 (up to smoothness constants). We assume that Ti ∈ [0,∞] is the bound on the times required to calculate one stochastic gradient ∇fi by worker i, T₁ < ... < Tn, and m > n log n.

🔼 This table compares the worst-case time complexity of several asynchronous methods for solving smooth nonconvex finite-sum optimization problems. The comparison considers the impact of heterogeneous workers with varying computation times, denoted by Ti. The table highlights the limitations of existing methods and shows how Freya PAGE offers significantly improved time complexity guarantees under weaker assumptions.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the worst-case time complexity guarantees of methods that work with asynchronous computations in the setup from Section 1 (up to smoothness constants). We assume that Ti ∈ [0,∞] is the bound on the times required to calculate one stochastic gradient ∇fi by worker i, T₁ < ... < Tn, and m > n log n.

🔼 This table compares the time complexity of various asynchronous optimization methods. It highlights Freya PAGE’s superior performance, especially in large-scale settings (where the number of data samples is significantly larger than the number of workers). The comparison considers factors like the number of data samples, number of workers, error tolerance, and the time bounds for individual workers’ computations.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the worst-case time complexity guarantees of methods that work with asynchronous computations in the setup from Section 1 (up to smoothness constants). We assume that Ti ∈ [0,∞] is the bound on the times required to calculate one stochastic gradient f; by worker i, T₁ < ... < Tη, and m > n log n.

Full paper#