TL;DR#

Many machine learning applications rely on probabilistic values like Shapley values for tasks such as feature attribution and data valuation. However, calculating these values is computationally expensive, often requiring approximation methods. Existing methods usually focus on specific probabilistic values, leading to the need to approximate several candidates and select the best, which is inefficient. This paper addresses the problem of approximating multiple probabilistic values simultaneously.

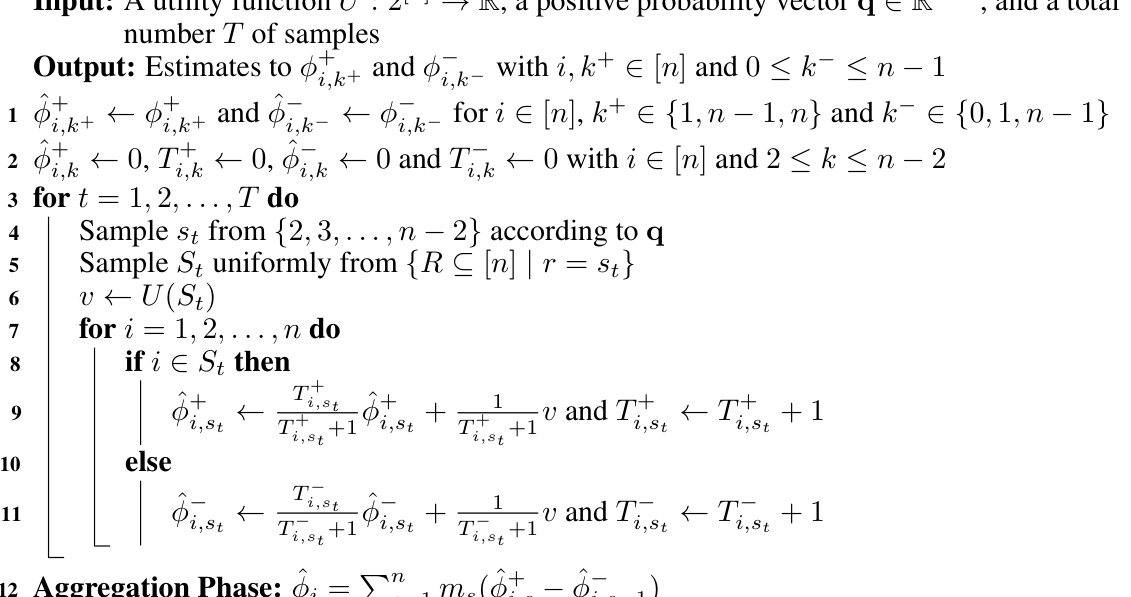

The paper proposes a novel ‘One-sample-fits-all’ (OFA) framework that addresses this issue. This method leverages the concept of (ϵ, δ)-approximation, optimizing a sampling vector to achieve fast convergence rates across different probabilistic values. The study derives a key formula to determine convergence rate and uses this to optimize the sampling vector, resulting in two efficient estimators: OFA-A (one-for-all) and OFA-S (specific). OFA-A demonstrates state-of-the-art time complexity for all probabilistic values on average, and OFA-S achieves the fastest convergence rate specifically for Beta Shapley values. The work connects probabilistic values to least square regression and shows how the OFA-A estimator can solve various datamodels simultaneously.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on probabilistic values and feature attribution, offering a novel, unified approach that’s both theoretically sound and empirically efficient. It opens avenues for applying these techniques to a wider range of machine learning problems and related areas like data valuation, impacting various applications.

Visual Insights#

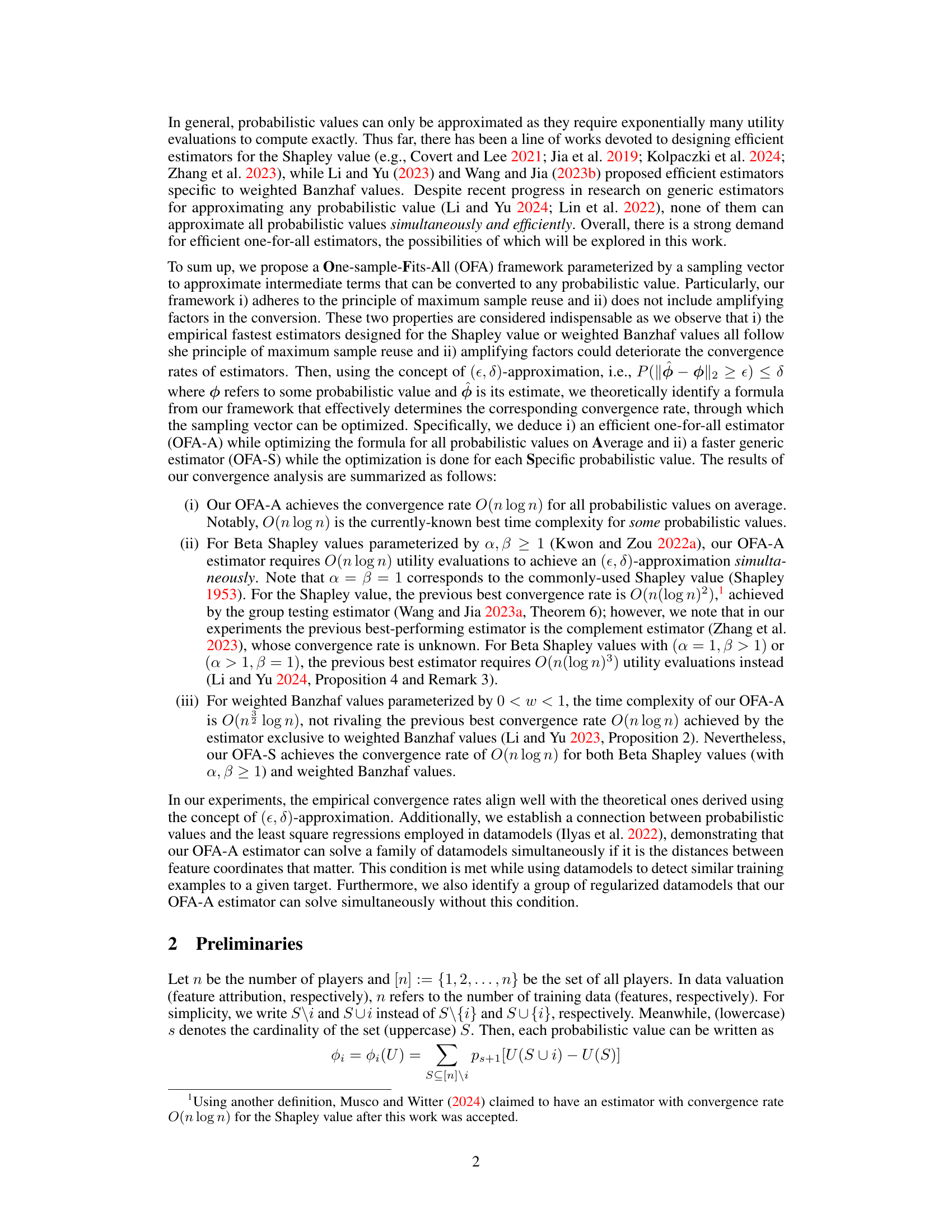

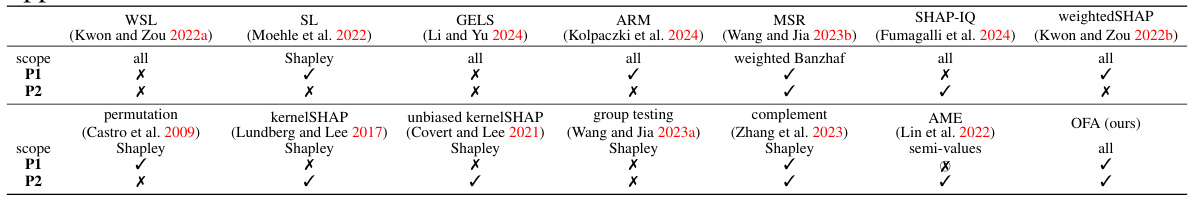

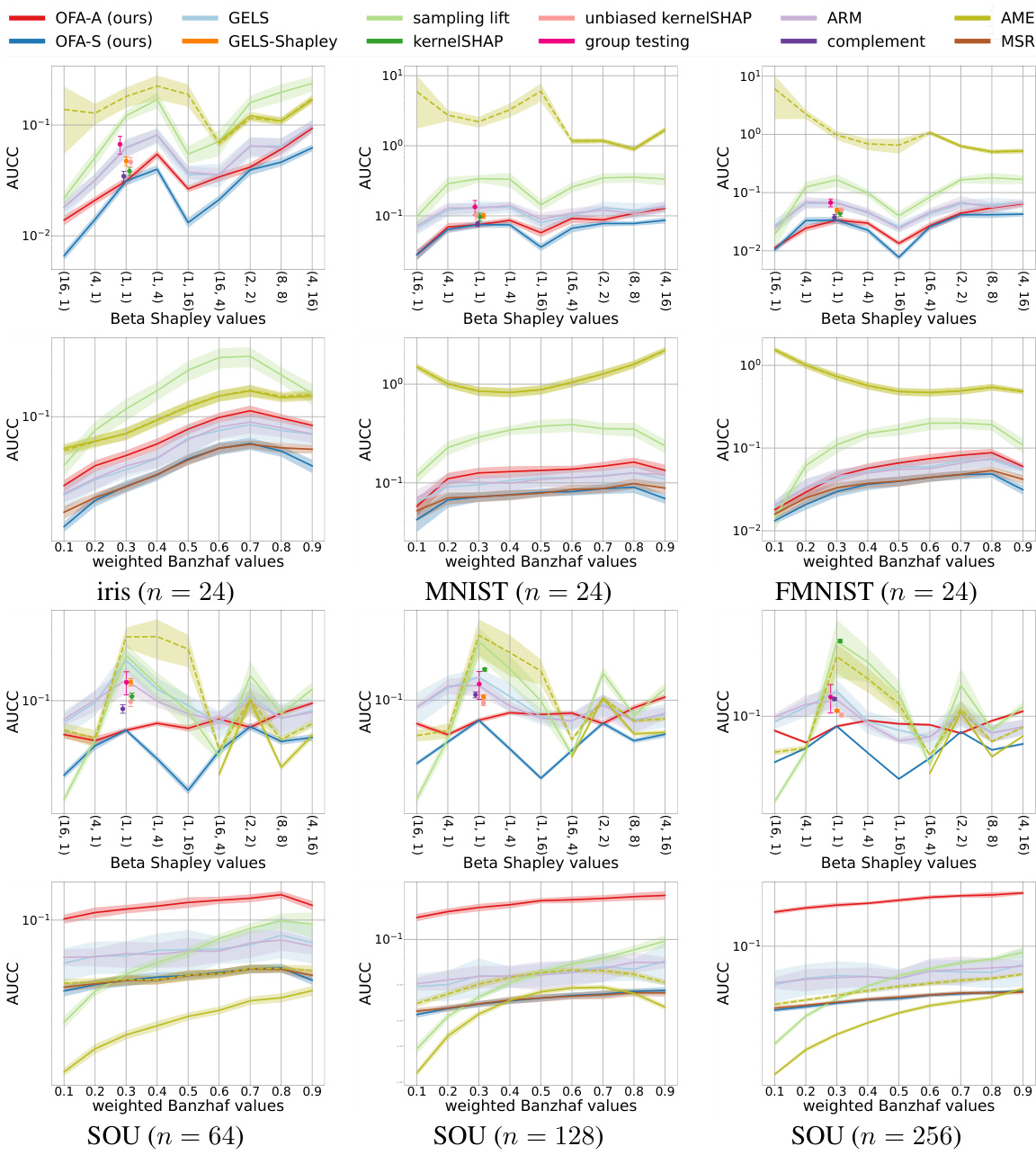

🔼 This figure compares the performance of ten different one-for-all estimators for approximating probabilistic values. It shows the relative difference between the estimated and true values plotted against the number of utility evaluations per player. The estimators are evaluated on three Beta Shapley value configurations (Beta(4,1), Beta(1,1), Beta(1,4)) and three weighted Banzhaf values (WB-0.2, WB-0.5, WB-0.8). The results demonstrate that the proposed OFA-A and OFA-S estimators generally outperform other methods in terms of convergence speed. The experiment used cross-entropy loss of a LeNet model trained on 24 data points from the Fashion-MNIST dataset.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of ten one-for-all estimators. Beta(α, β) denotes Beta Shapley values, whereas WB-α refers to weighted Banzhaf values. Our OFA-S estimator is equal to the OFA-A estimator for the Shapley value. The suffix “Shapley” indicates that there is no reweighting for the Shapley value, while “Banzhaf” stands for the Banzhaf value. The permutation estimator is originally proposed for the Shapley value. The utility function U is the cross-entropy loss of LeNet trained on 24 data from FMNIST. All the results are averaged using 30 random seeds.

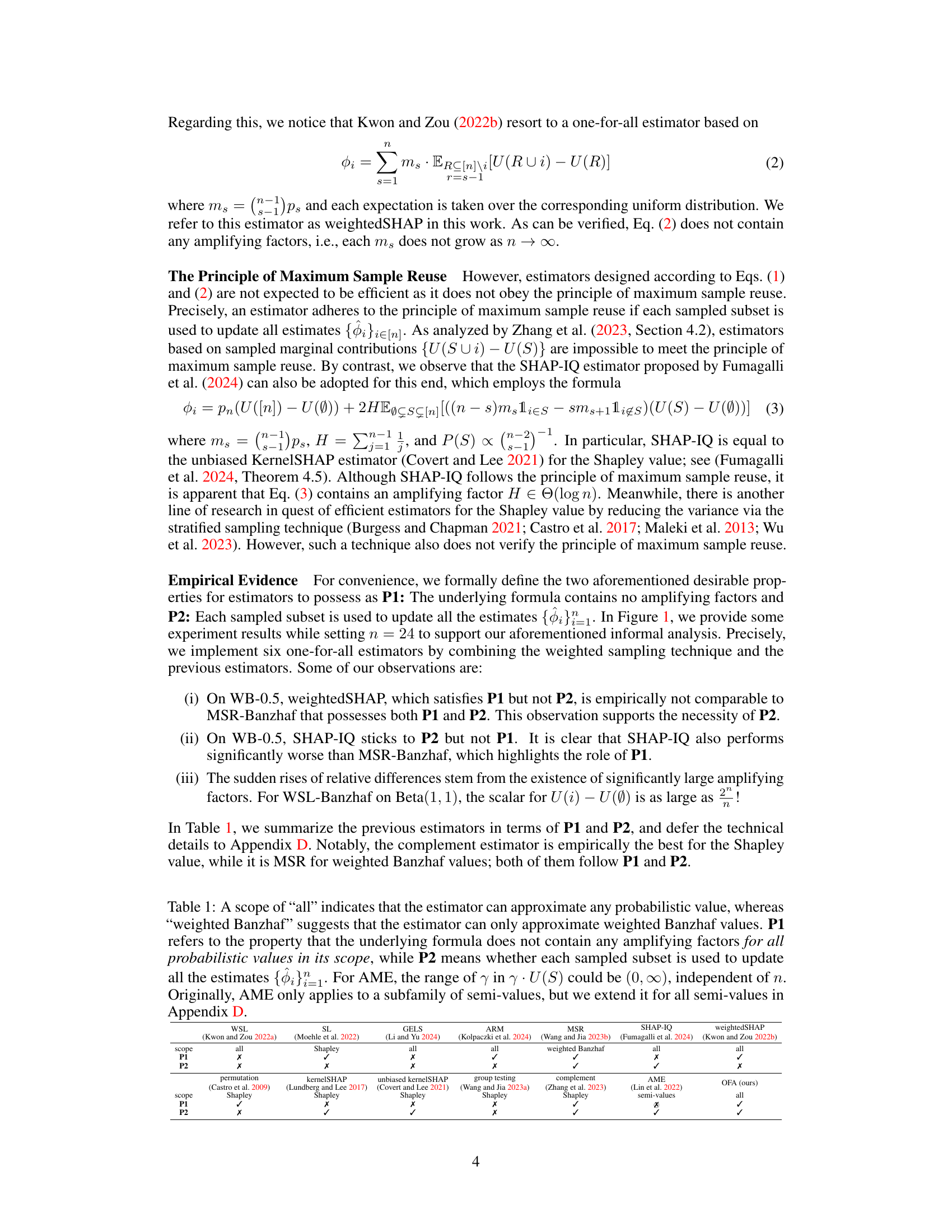

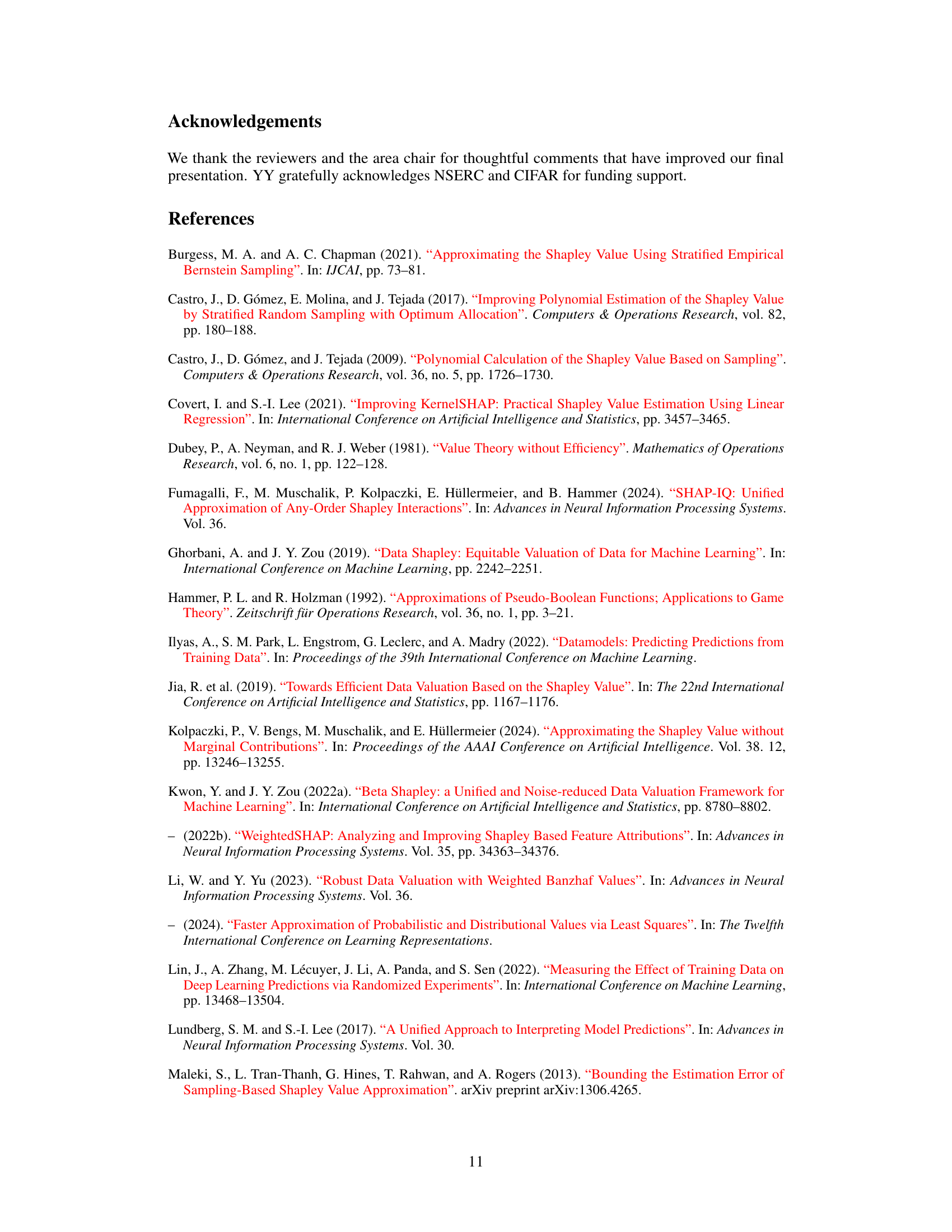

🔼 This table summarizes the characteristics of various one-for-all estimators for probabilistic values. It compares their scope (whether they can estimate all probabilistic values or only specific ones), and whether they satisfy two desirable properties: P1 (the formula has no amplifying factors) and P2 (each sampled subset is used for all estimates). This helps to understand the tradeoffs and efficiency of different estimation methods.

read the caption

Table 1: A scope of 'all' indicates that the estimator can approximate any probabilistic value, whereas 'weighted Banzhaf' suggests that the estimator can only approximate weighted Banzhaf values. P1 refers to the property that the underlying formula does not contain any amplifying factors for all probabilistic values in its scope, while P2 means whether each sampled subset is used to update all the estimates {Φi}i=1. For AME, the range of γ in γ · U(S) could be (0, ∞), independent of n. Originally, AME only applies to a subfamily of semi-values, but we extend it for all semi-values in Appendix D.

In-depth insights#

One-Sample Estimation#

One-sample estimation, in the context of probabilistic values approximation, is a powerful technique. It aims to efficiently estimate multiple probabilistic values using only a single sample of the underlying utility function. This is particularly advantageous in settings where obtaining samples is expensive or time-consuming. The key to this approach is using a carefully constructed sampling strategy to capture the necessary information for all desired estimators simultaneously. However, the success of one-sample estimation critically relies on avoiding amplifying factors that can disproportionately affect the convergence rate. The theoretical analysis of such an estimator involves deriving bounds on the error to guarantee that the method efficiently approximates all desired probabilistic values, emphasizing the importance of both theoretical justification and empirical validation. Optimizing sampling methods for this purpose would enhance accuracy and computational efficiency. Finding the optimal sampling scheme is paramount to achieve good convergence rates and reduce reliance on multiple samples.

Convergence Analysis#

A thorough convergence analysis is crucial for evaluating the efficiency and reliability of any approximation algorithm. In the context of approximating probabilistic values, such as Shapley values or weighted Banzhaf values, a rigorous convergence analysis would examine how the estimation error decreases as the number of samples increases. This would likely involve establishing theoretical bounds on the error, perhaps using techniques from probability theory or statistical learning. Key aspects would include identifying the rate of convergence (e.g., linear, logarithmic, etc.) and demonstrating that the algorithm converges to the true value with high probability as the sample size goes to infinity. Furthermore, a comprehensive analysis would explore the impact of various parameters on the convergence rate and potentially provide strategies for optimizing these parameters. Empirical validation through simulations or experiments would be essential, comparing the algorithm’s performance against other existing methods and verifying that the theoretical findings are reflected in practical applications. The analysis should also address issues like computational complexity and the practical limitations of the approach.

Datamodel Connections#

The section exploring ‘Datamodel Connections’ in the research paper is crucial for bridging the gap between theoretical probabilistic values and practical applications in machine learning. It suggests a novel link between probabilistic values, specifically those employed in feature attribution or data valuation, and the least-squares regression problems frequently encountered in various datamodels. This connection is particularly insightful as it offers a new perspective on how to solve datamodeling problems, potentially using already established techniques from the world of probabilistic values. Efficient estimators for probabilistic values, like the one-for-all estimator introduced in the paper, may thus find an entirely new application domain, proving to be simultaneously valuable for understanding both the theoretical underpinnings and the practical performance of datamodels. The identification of this connection is a significant contribution of the research, opening up possibilities for future research to explore, test, and refine this link further. The resulting unified framework promises to be extremely beneficial for a variety of machine learning applications where datamodels are used. The authors successfully highlight the potential for applying established probabilistic methods to a broad class of datamodeling scenarios, thus expanding the scope and impact of both areas.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper would systematically test the study’s core claims. It would involve designing experiments to isolate and measure the effects of key variables, such as comparing the proposed method to existing approaches under controlled conditions. The results should then be presented with clear visualizations and statistical analyses to demonstrate the method’s performance and any advantages it offers. A robust validation would also consider various datasets or scenarios to evaluate generalizability and explore potential limitations. Careful attention to experimental design and rigorous analysis is crucial to ensure the credibility and impact of the research findings. Ideally, the results should be interpreted within a broader theoretical context, discussing how they support or contradict the established understanding of the phenomenon under investigation, and suggesting avenues for future research.

Future Work#

Future research could explore extending the one-sample-fits-all framework to handle more complex scenarios, such as those involving noisy or incomplete data. Investigating the impact of different sampling strategies on estimator performance is also crucial. The connection between probabilistic values and data models established in this paper warrants further investigation. This includes exploring applications beyond data valuation, such as fairness and explainability, and developing efficient algorithms to solve families of datamodels simultaneously. Additionally, research on more sophisticated theoretical analyses could focus on tightening the convergence rate bounds for different probabilistic values, investigating the impact of dimensionality, and further refining the optimization of the sampling vector. Finally, empirical studies on diverse datasets are crucial to validate the generality and robustness of the proposed estimators and their performance compared to existing state-of-the-art methods across various application domains.

More visual insights#

More on figures

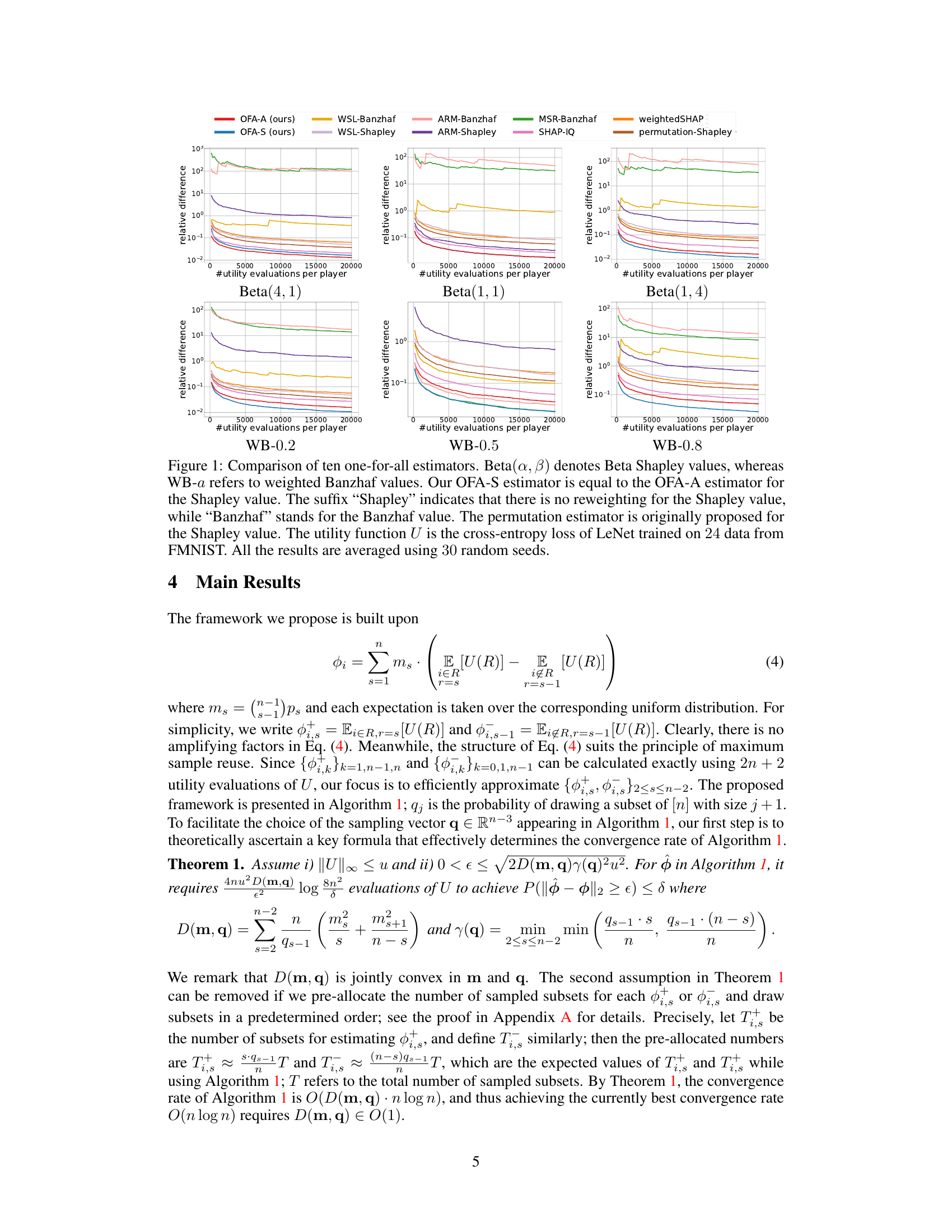

🔼 The figure compares ten different one-for-all estimators for approximating various probabilistic values using different utility functions. The estimators include our proposed OFA-A and OFA-S, as well as several baselines (WSL, SHAP-IQ, weightedSHAP, permutation). Beta Shapley and weighted Banzhaf values are used, with varying parameters. The results show the relative difference between the estimated and true values over a range of utility evaluations per player, demonstrating the convergence rate of each estimator. The experiment uses cross-entropy loss of LeNet on FMNIST data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of ten one-for-all estimators. Beta(α, β) denotes Beta Shapley values, whereas WB-α refers to weighted Banzhaf values. Our OFA-S estimator is equal to the OFA-A estimator for the Shapley value. The suffix “Shapley” indicates that there is no reweighting for the Shapley value, while “Banzhaf” stands for the Banzhaf value. The permutation estimator is originally proposed for the Shapley value. The utility function U is the cross-entropy loss of LeNet trained on 24 data from FMNIST. All the results are averaged using 30 random seeds.

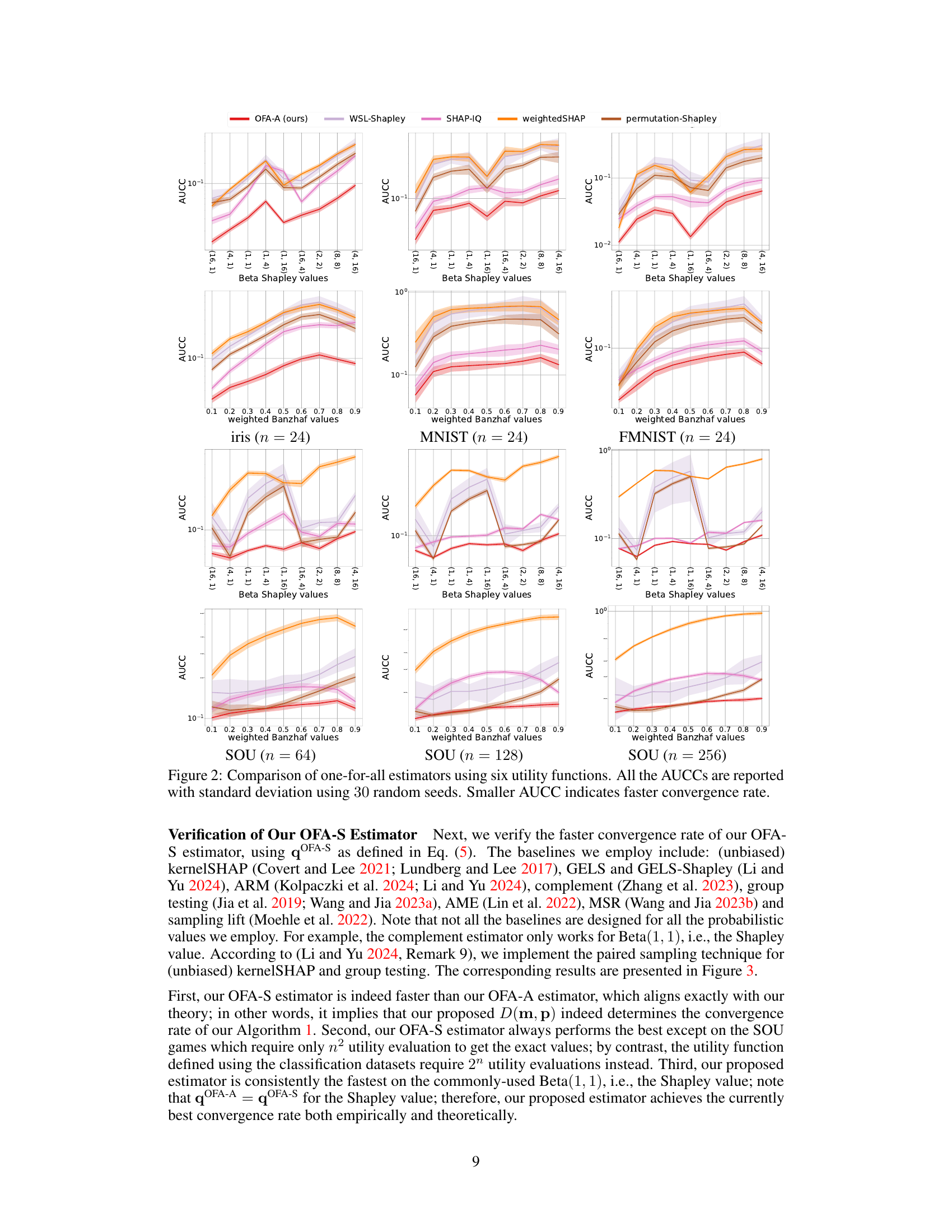

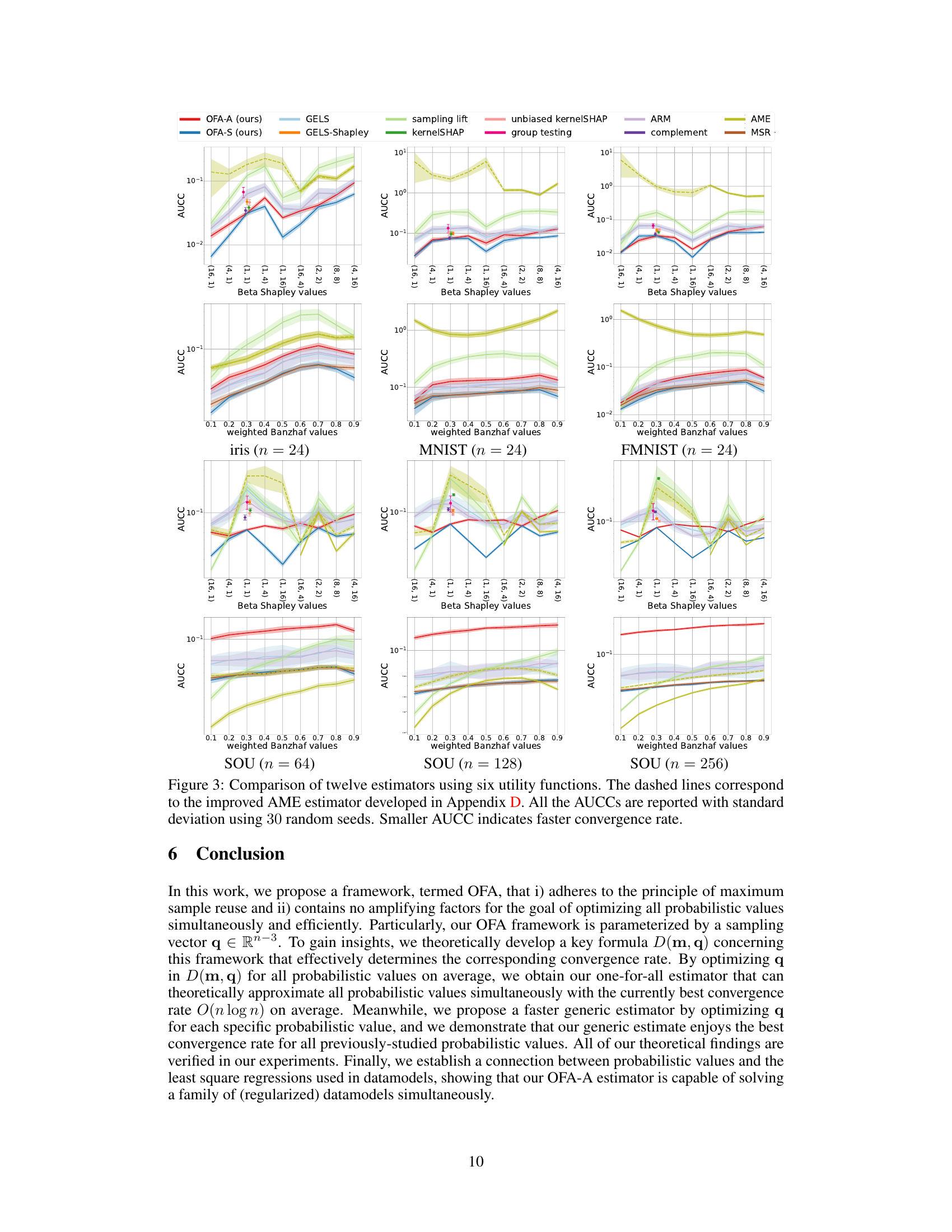

🔼 This figure compares the performance of ten different one-for-all estimators for approximating probabilistic values. The estimators are evaluated using three different datasets (iris, MNIST, and FMNIST) and two types of probabilistic values (Beta Shapley and weighted Banzhaf). The x-axis represents the number of utility evaluations per player, and the y-axis shows the relative difference between the estimated and true values. The results demonstrate that the OFA-A estimator generally outperforms other methods.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of ten one-for-all estimators. Beta(α, β) denotes Beta Shapley values, whereas WB-α refers to weighted Banzhaf values. Our OFA-S estimator is equal to the OFA-A estimator for the Shapley value. The suffix “Shapley” indicates that there is no reweighting for the Shapley value, while “Banzhaf” stands for the Banzhaf value. The permutation estimator is originally proposed for the Shapley value. The utility function U is the cross-entropy loss of LeNet trained on 24 data from FMNIST. All the results are averaged using 30 random seeds.

🔼 The figure compares ten different one-for-all estimators for approximating probabilistic values (Beta Shapley and weighted Banzhaf values). It shows the convergence rate of each estimator, measured by the relative difference between the estimated value and the true value, plotted against the number of utility evaluations. The results are shown for various parameter settings (Beta Shapley α, β values and weighted Banzhaf α values) and datasets (Beta Shapley and weighted Banzhaf values). The figure highlights the superiority of the proposed OFA (One-sample-Fits-All) estimator and OFA-S in terms of convergence speed, especially for Shapley values and certain parameter settings.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of ten one-for-all estimators. Beta(α, β) denotes Beta Shapley values, whereas WB-α refers to weighted Banzhaf values. Our OFA-S estimator is equal to the OFA-A estimator for the Shapley value. The suffix “Shapley” indicates that there is no reweighting for the Shapley value, while “Banzhaf” stands for the Banzhaf value. The permutation estimator is originally proposed for the Shapley value. The utility function U is the cross-entropy loss of LeNet trained on 24 data from FMNIST. All the results are averaged using 30 random seeds.

Full paper#