↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current methods for analyzing brain connectivity struggle to fully capture the complex interplay between brain structure (anatomical connections) and brain function (neural activity). Existing approaches often lack the necessary biological grounding, limiting their ability to provide deeper insights into cognitive processes and disease mechanisms. Furthermore, existing methods often struggle with the high degree of variability in brain functional connectivity data across subjects.

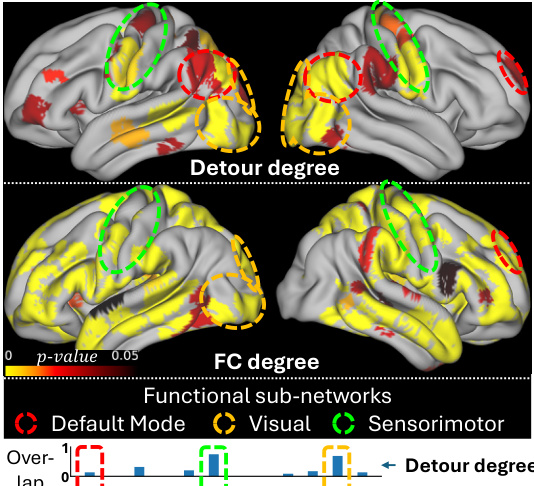

NeuroPath addresses these challenges with a novel biological-inspired deep learning model. It uses a transformer-based architecture with a multi-head self-attention mechanism that explicitly considers multi-hop neural pathways, thus linking brain structure and function more effectively. The model achieves state-of-the-art performance on large datasets, demonstrating improvements in cognitive task recognition and disease diagnosis. Crucially, NeuroPath offers better explainability, visualizing these neural pathways to aid in understanding the underlying biological mechanisms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in network neuroscience and machine learning. It bridges the gap between structural and functional brain connectivity, offering a novel approach to understanding the complex interplay between brain structure and function. The biological-inspired deep learning model provides a new tool for analyzing neuroimaging data and offers improved accuracy in cognitive task recognition and disease prediction. Furthermore, its explainability through neural pathway visualization opens avenues for deeper biological insights, enhancing our understanding of the human connectome.

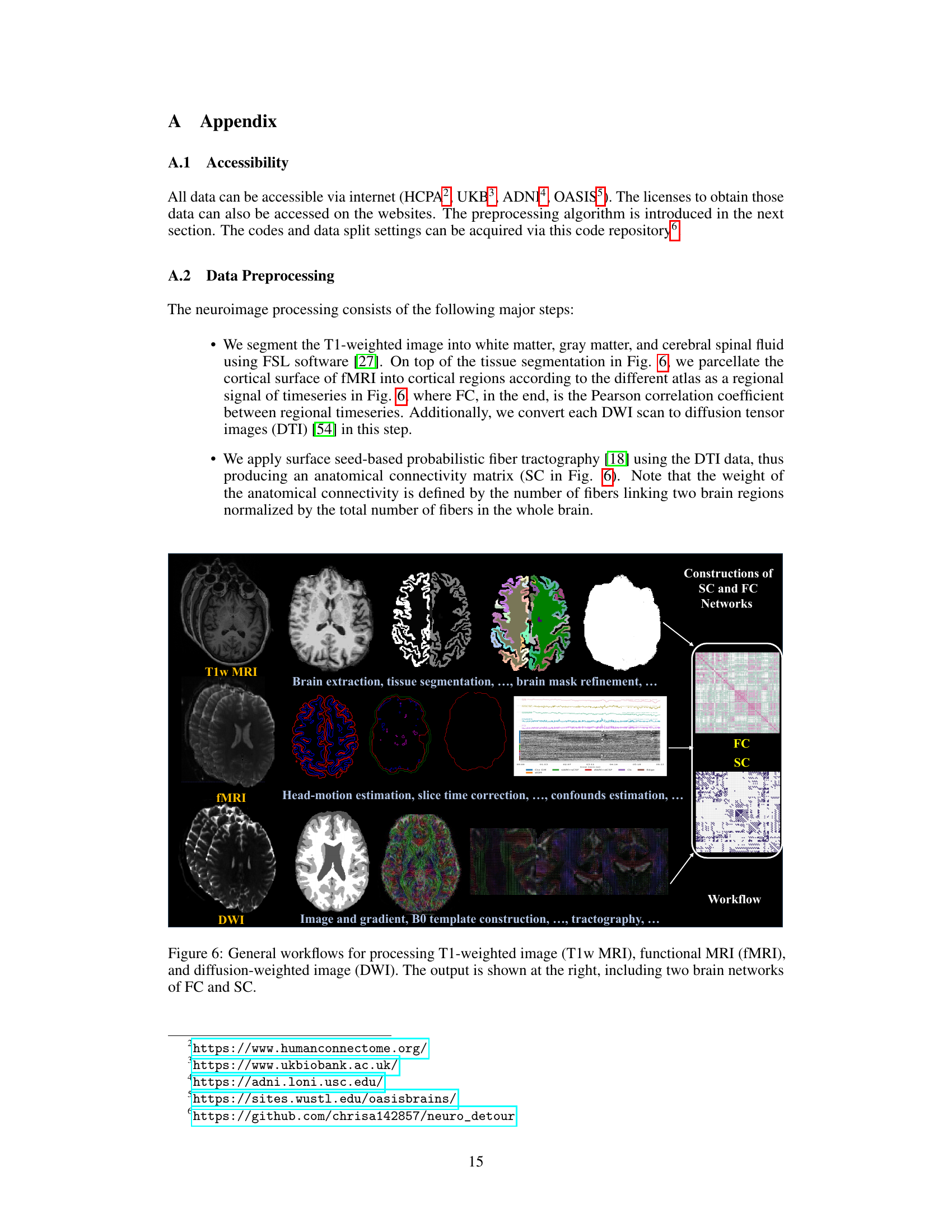

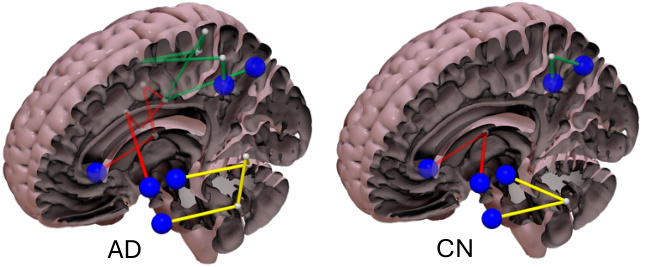

Visual Insights#

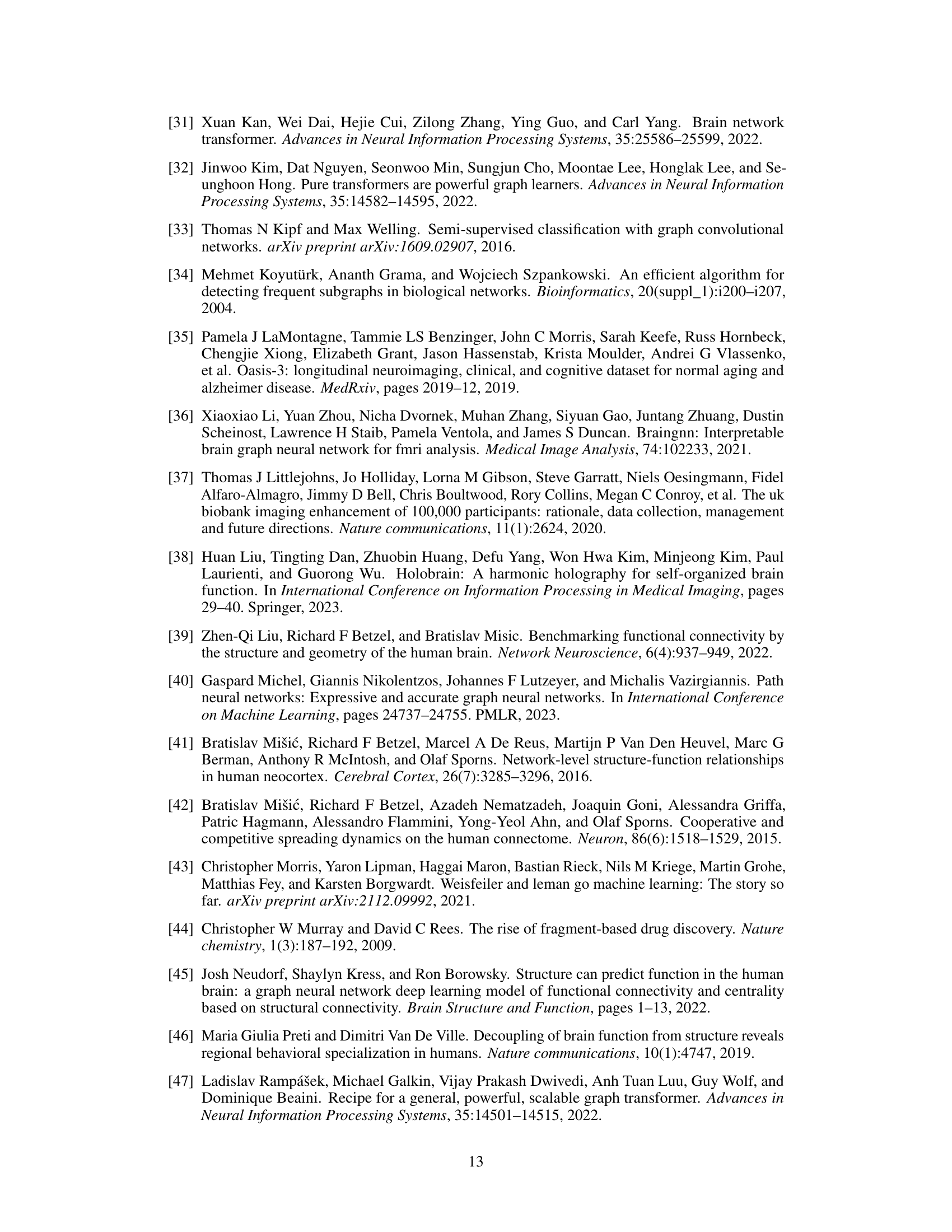

This figure illustrates the core concept of NeuroPath, a novel deep learning model that leverages both structural and functional connectivity data to identify neural pathways supporting brain function. It highlights the multivariate SC-FC coupling mechanism, demonstrating how multiple structural connections (SC, in orange) can support a single functional connection (FC, in green), forming a ‘detour pathway.’ The NeuroPath Transformer uses a multi-head self-attention mechanism to capture these multi-hop detour pathways from paired SC and FC graphs, ultimately leading to more accurate and interpretable results in tasks such as cognitive task recognition and disease diagnosis.

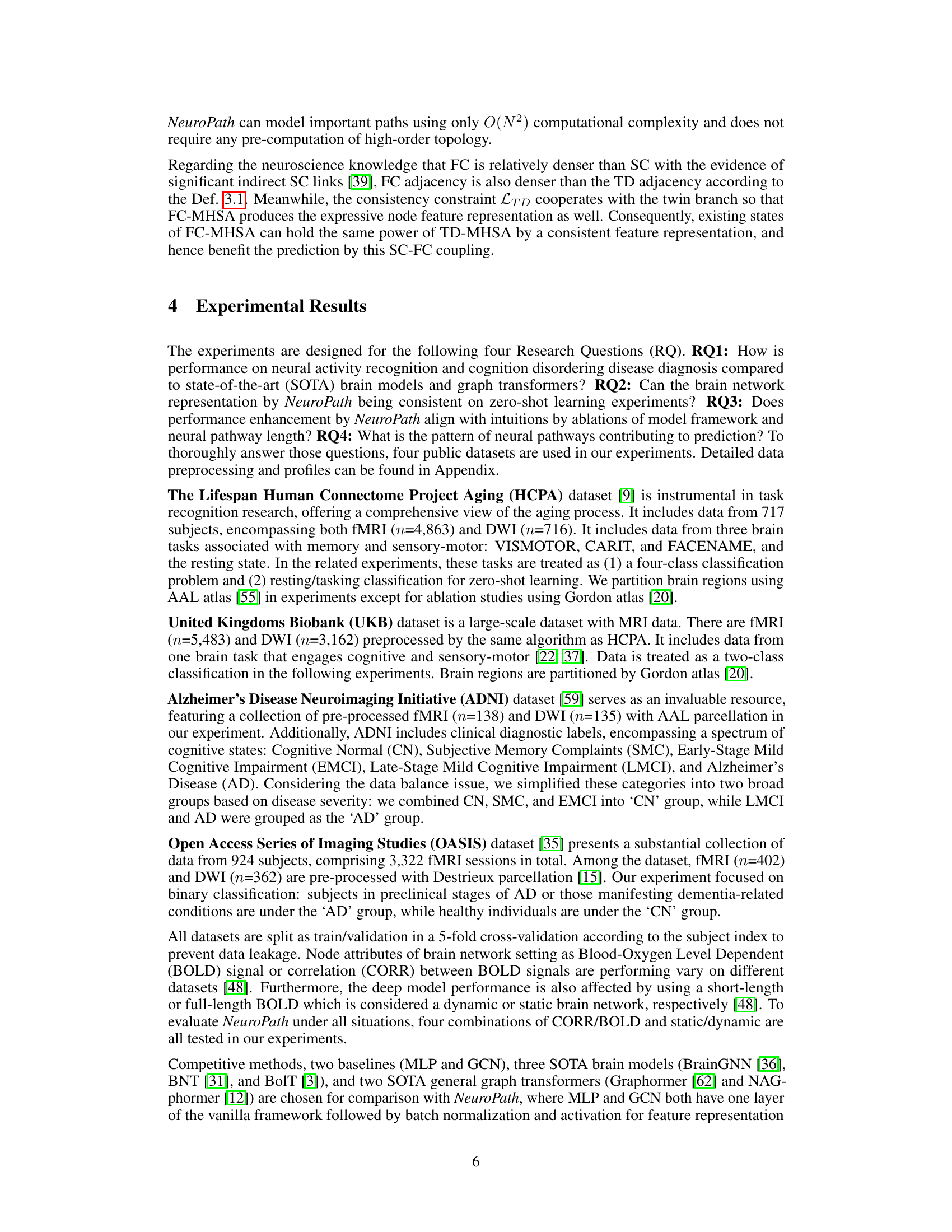

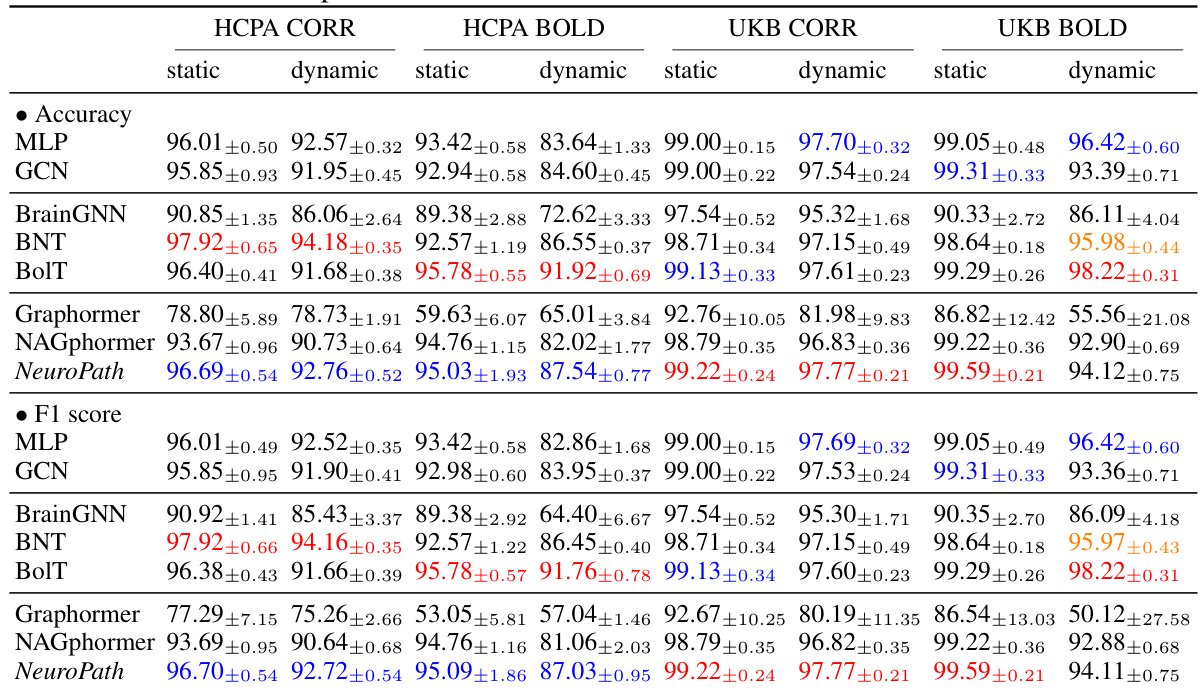

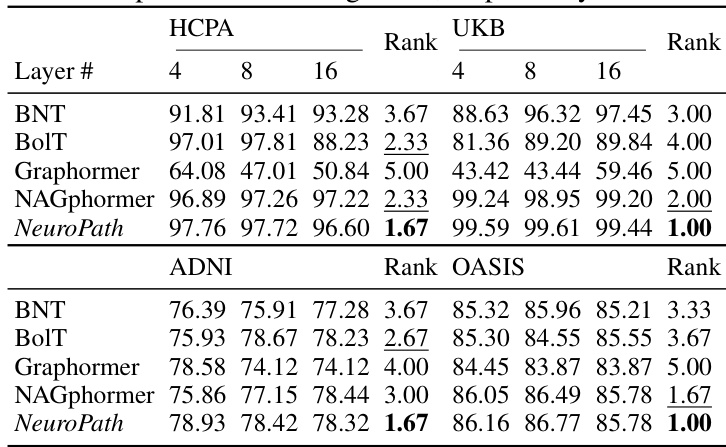

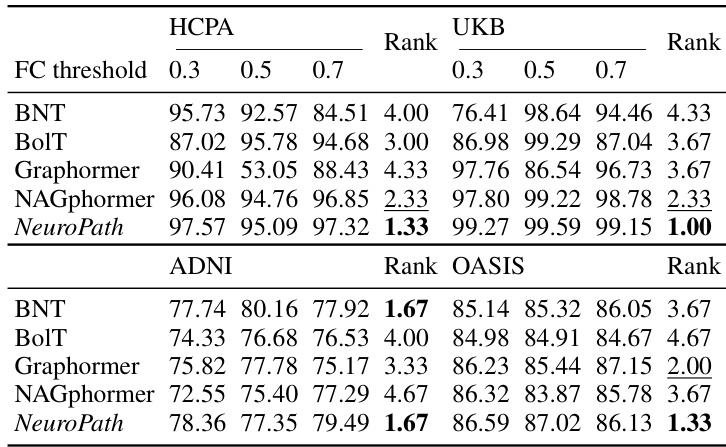

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different machine learning models, including NeuroPath, on two datasets (HCPA and UKB) for neural activity classification. The performance is measured by accuracy and F1 score, with results shown for different combinations of static/dynamic data and BOLD/CORR features. Colored numbers highlight the top three performing models for each metric and data setting.

In-depth insights#

NeuroPath’s Design#

NeuroPath’s design is a multi-modal, graph-based transformer model specifically engineered for analyzing human connectomes. It leverages the concept of topological detours to capture the complex interplay between structural and functional connectivity (SC-FC). The architecture employs a twin-branch MHSA (multi-head self-attention) mechanism, where one branch processes SC data to identify detour pathways, while the other processes FC data. These pathways are filtered using adjacency matrices to focus attention on relevant connections, resulting in more informative and biologically plausible representations. The model’s design highlights a commitment to explainability, providing insights into the underlying neural pathways supporting functional brain activity. This approach aims to overcome the limitations of existing models by incorporating neuroscience-inspired features within a powerful deep learning framework.

Multi-modal Fusion#

Multi-modal fusion, in the context of a research paper, likely involves integrating data from multiple sources to create a more comprehensive understanding. The core idea is that combining different modalities, such as structural and functional brain imaging data, can reveal insights not obtainable from each modality alone. A thoughtful approach to multi-modal fusion would address the challenges inherent in combining data of different natures, including the need for proper alignment and normalization of diverse datasets. The paper likely explores various fusion techniques, possibly focusing on those that leverage neural networks or deep learning to learn complex, non-linear relationships between the modalities. Effective multi-modal fusion requires careful consideration of the specific characteristics of each data modality and the selection of appropriate fusion methods to effectively integrate their information. The success of the fusion strategy will depend on the ability to extract complementary information from different modalities and to minimize the negative impact of noise or inconsistencies in the input data. Finally, any evaluation of the fusion approach would highlight the improved performance or novel insights that can be obtained when compared to using single modalities. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the fusion results carefully.

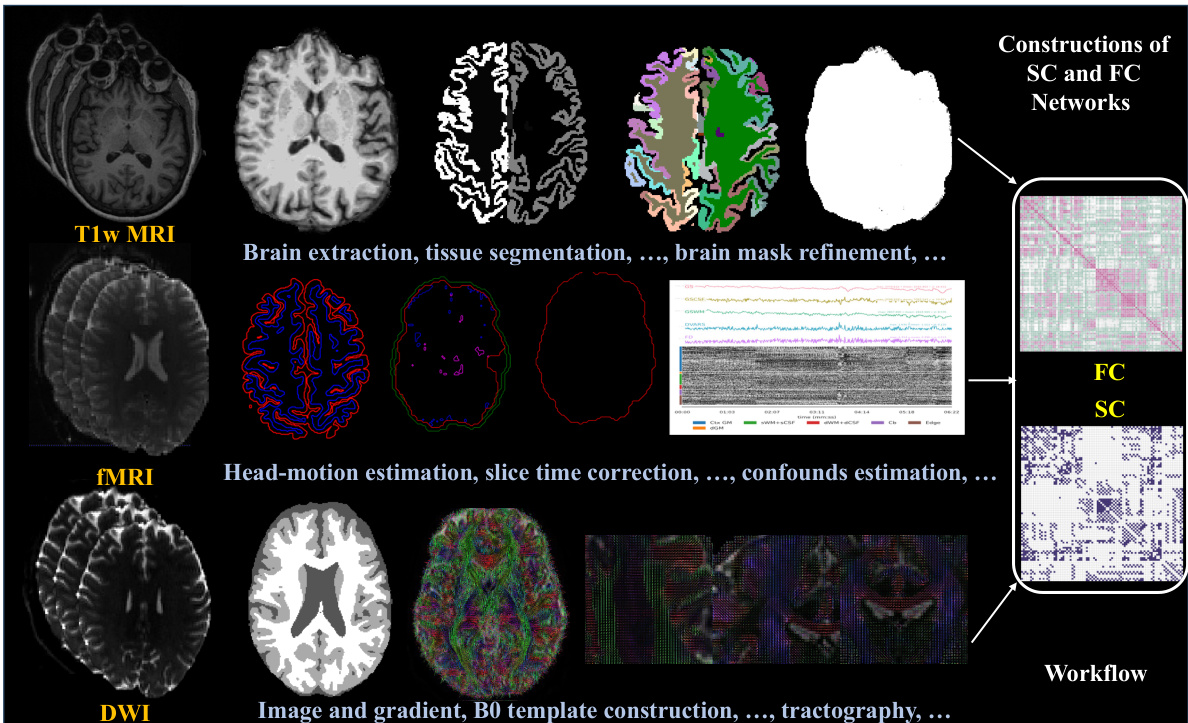

Experimental Setup#

An effective ‘Experimental Setup’ section in a research paper should meticulously detail the methodology, ensuring reproducibility. It needs to clearly define the datasets used, specifying their size, characteristics, and any preprocessing steps. For instance, mentioning the number of subjects, image resolution, and whether data augmentation was applied is crucial. The choice of evaluation metrics should be justified, highlighting why they are appropriate for the specific research question and providing context. Similarly, the experimental design should be articulated, clarifying whether it was a controlled experiment, an observational study, or a simulation. Details regarding hyperparameters, model architectures, and training procedures (e.g., optimizer, batch size, learning rate) are vital for reproducibility. Finally, the section should explicitly address the handling of biases, confounding factors, and potential limitations of the experimental approach.

Zero-Shot Learning#

Zero-shot learning (ZSL) in the context of this research paper presents a compelling avenue for evaluating the model’s ability to generalize beyond the training data. The experiment design, involving training on one dataset and testing on another, directly assesses the model’s capacity for unseen scenarios. Successful zero-shot performance would significantly strengthen the claims of the model’s robustness and generalizability. The results of this evaluation are particularly critical given the inherent variability across different neuroimaging datasets and the challenges of achieving consistent performance in different contexts. A strong zero-shot performance indicates that the underlying features learned by the model are genuinely representative of the underlying neural processes, rather than dataset-specific artifacts. The analysis of zero-shot performance thus provides a rigorous test of the model’s biological plausibility and its broader utility across diverse populations and experimental settings.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore deeper integration of multi-modal data, such as combining structural and functional connectivity with other neuroimaging modalities (e.g., EEG, MEG). This would allow for a more holistic understanding of brain function and its relation to anatomical structures. Another promising direction is to develop more sophisticated graph neural network architectures that can capture the complex, high-order relationships present in brain networks. This could involve incorporating advanced attention mechanisms or exploring novel graph-based learning paradigms. Furthermore, improving the explainability and interpretability of these models is crucial. Techniques like attention maps or feature visualization can help researchers understand how the models arrive at their predictions, providing valuable insights into brain function. Finally, applying these techniques to larger and more diverse datasets is essential for generalizing findings and validating the robustness of the models. This includes studies across different populations, age groups, and disease states, as well as exploring potential applications in personalized medicine and diagnostics.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the core concept of NeuroPath, a novel deep learning model for analyzing human connectomes. It highlights the relationship between structural connectivity (SC), representing the physical connections in the brain, and functional connectivity (FC), representing the correlated activity between brain regions. The key innovation is the concept of a ’topological detour,’ where a functional connection (FC link) is supported by multiple indirect structural pathways (SC detour). The model uses a multi-head self-attention mechanism within a Transformer architecture to capture these multi-hop detour pathways and learn effective representations from both SC and FC data.

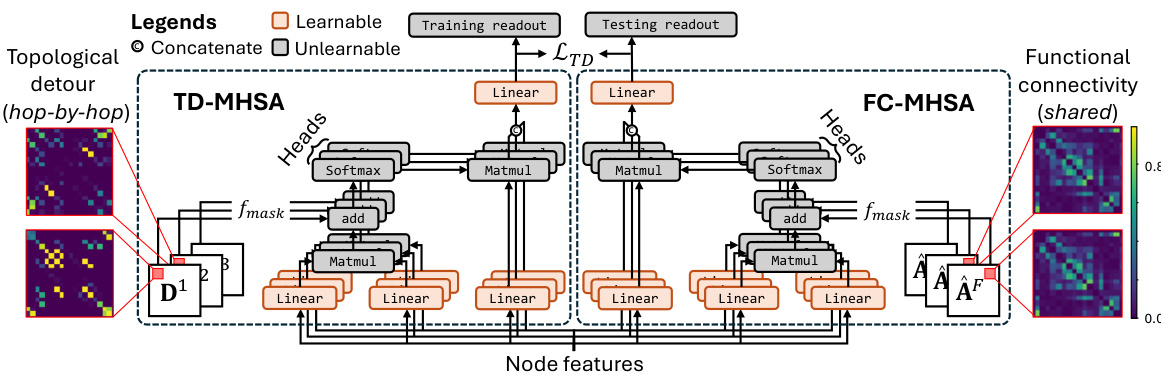

This figure shows the architecture of NeuroPath, a deep learning model for analyzing human connectomes. It uses two branches: one for topological detour (TD-MHSA) and one for functional connectivity (FC-MHSA). Both branches employ multi-head self-attention mechanisms to capture multi-modal features from structural and functional connectivity data. The TD-MHSA branch focuses on identifying neural pathways, while the FC-MHSA branch processes functional connectivity information. A consistency constraint loss (LTD) ensures that both branches learn consistent representations. The model efficiently represents neural pathways by avoiding the computation of all simple paths, significantly reducing computational cost.

This figure shows the ablation study on the pathway length of NeuroPath. The x-axis represents the pathway length (from 2 to 8 hops), and the y-axis represents the F1 score. The four subplots show the results for four different datasets (HCPA, UKB, ADNI, and OASIS), each with a different number of brain regions (333, 333, 116, and 160, respectively). The green line represents the average F1 score, and the shaded area represents the standard error. The results indicate that the optimal pathway length varies across datasets and may be related to the number of brain regions.

This figure illustrates the core concept of NeuroPath, a novel deep learning model for analyzing brain connectomes. It highlights the multivariate SC-FC coupling mechanism, which considers how functional connectivity (FC) between brain regions is supported by multiple pathways of structural connectivity (SC). The figure shows how NeuroPath uses a multi-head self-attention mechanism to capture this multi-hop pathway information, leading to improved representation learning and downstream applications.

This figure illustrates the core concept of NeuroPath, highlighting the multivariate SC-FC coupling mechanism. It shows how functional connectivity (FC) links between brain regions are supported by multiple structural connectivity (SC) pathways forming a cyclic loop. NeuroPath leverages this multi-hop detour pathway information via a novel multi-head self-attention mechanism to learn better feature representations.

This figure illustrates the core concept of NeuroPath, a novel deep learning model for analyzing human connectomes. It highlights the multivariate SC-FC coupling mechanism, where functional connectivity (FC) links are supported by multiple structural connectivity (SC) pathways forming a cyclic loop. NeuroPath leverages a multi-head self-attention mechanism within a Transformer architecture to capture multi-modal features from paired SC and FC graphs, effectively modeling this complex relationship.

This figure illustrates the core concept of NeuroPath, highlighting the multivariate SC-FC coupling mechanism. It shows how functional connectivity (FC) links between brain regions are supported by multiple structural connectivity (SC) pathways forming a cyclic loop. NeuroPath uses a multi-head self-attention mechanism to capture this multi-hop detour pathway information for improved feature representation.

More on tables

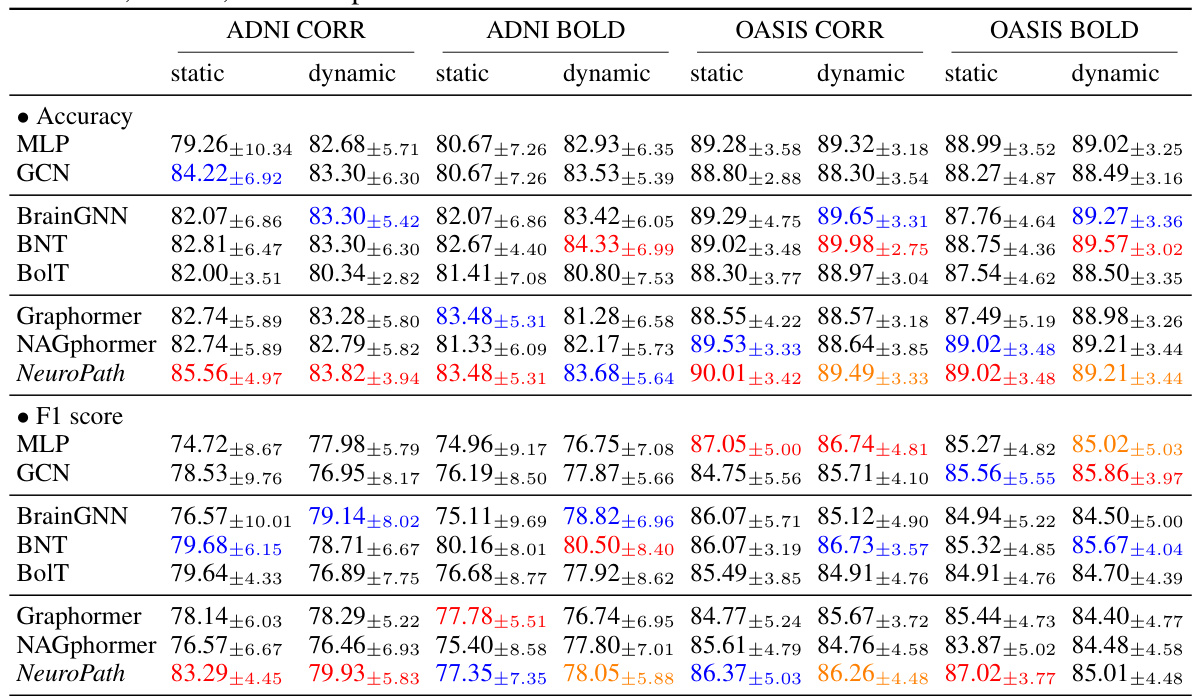

This table presents the performance comparison of different models on two datasets: ADNI and OASIS. The models are evaluated based on accuracy and F1 score using different data settings (static/dynamic BOLD and CORR). The colored numbers highlight the top three performing models for each setting.

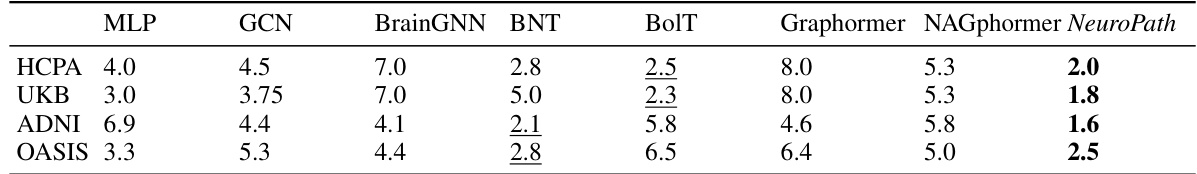

This table summarizes the average ranks of different machine learning models (MLP, GCN, BrainGNN, BNT, BolT, Graphormer, NAGphormer, and NeuroPath) across various datasets (HCPA, UKB, ADNI, OASIS) and evaluation metrics (Accuracy and F1 score). Different experimental scenarios (BOLD/CORR, static/dynamic) are considered. The ranking helps to understand the relative performance of each model under different conditions. Bold and underlined numbers highlight the top two performing models for each scenario.

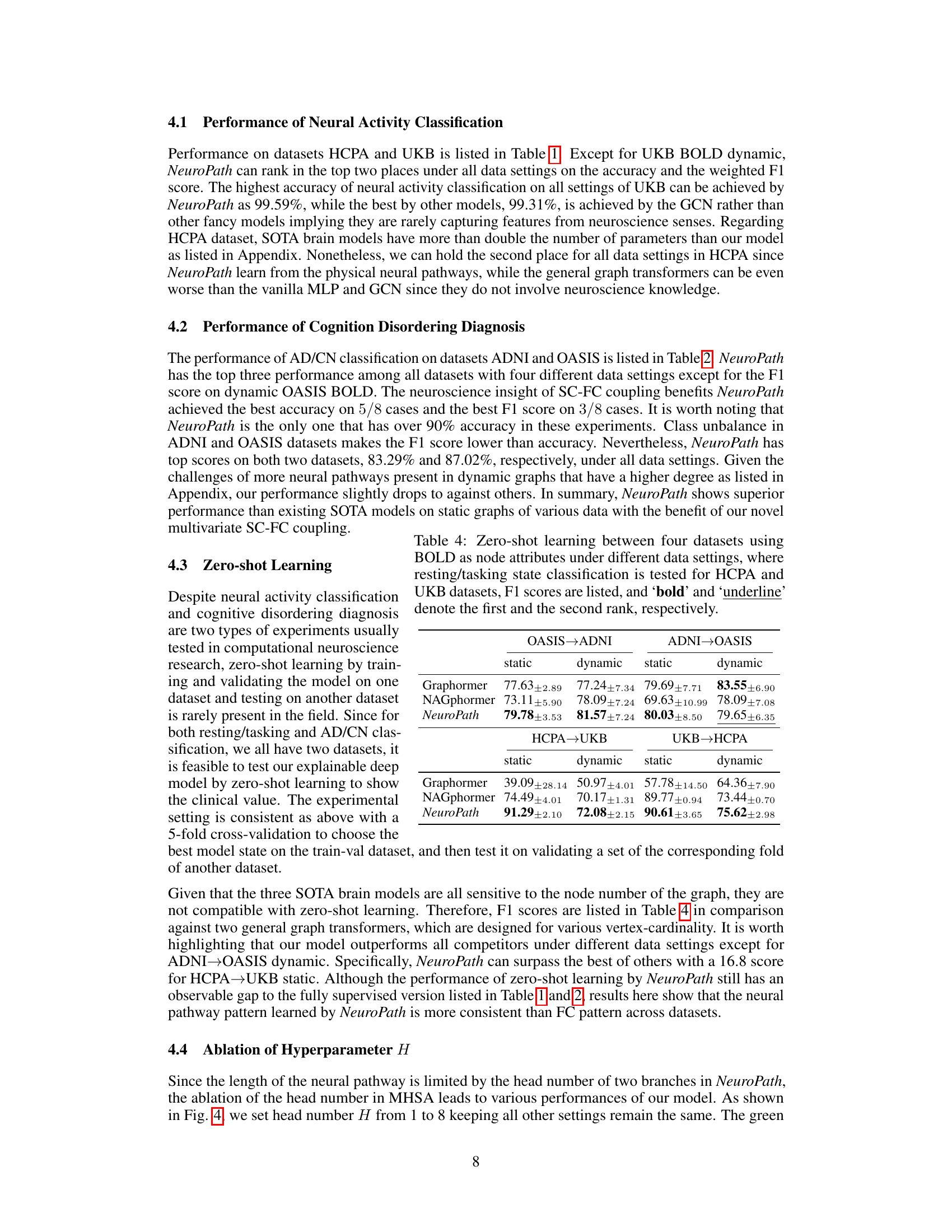

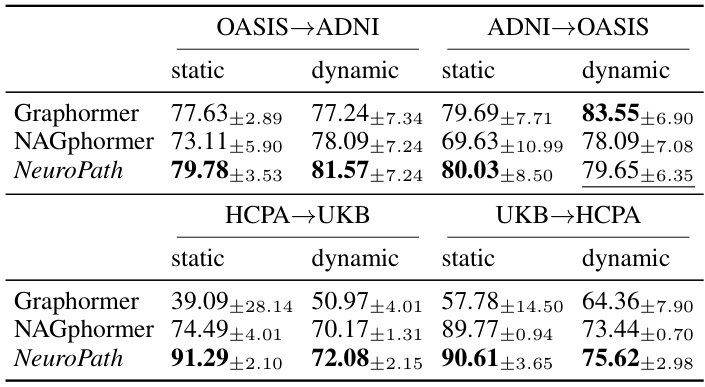

This table presents the results of zero-shot learning experiments. The model was trained on one dataset (either HCPA, UKB, ADNI, or OASIS) and tested on a different one. F1 scores are reported for both static and dynamic data, with BOLD as the node attribute. The top performing model in each setting is highlighted.

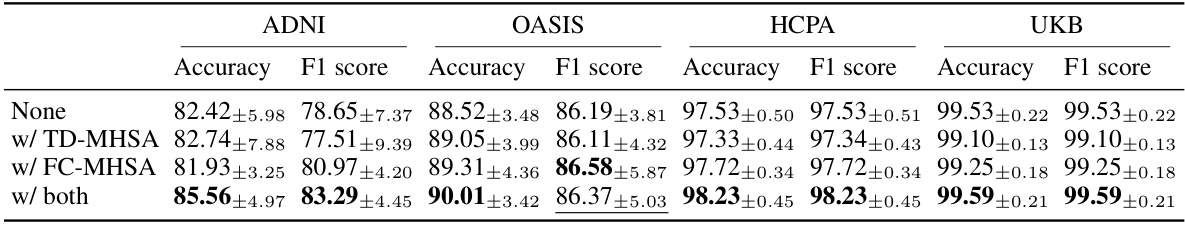

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the NeuroPath model. It shows the performance (Accuracy and F1 score) of four different model variations on four different datasets (ADNI, OASIS, HCPA, UKB). The variations are: using no additional transformer branches, using only the topological detour multi-head self-attention (TD-MHSA) branch, using only the functional connectivity filtered multi-head self-attention (FC-MHSA) branch, and using both branches. The best-performing model variation for each dataset and metric is highlighted.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different machine learning models, including NeuroPath, on two datasets (HCPA and UKB) for neural activity classification. The performance is measured using accuracy and F1 score, with results broken down by dataset and data type (BOLD dynamic, BOLD static, CORR dynamic, CORR static). Colored numbers highlight the top three performing models for each metric and data setting.

This table presents the performance comparison of different machine learning models, including NeuroPath, on two datasets (HCPA and UKB) for neural activity classification. The performance is measured by accuracy and F1 score under various settings (BOLD/CORR and dynamic/static). The colored numbers highlight the top three performing models for each setting.

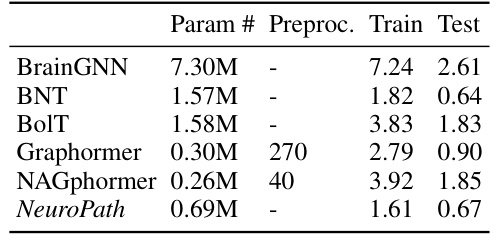

This table shows the computational cost of different models used in the paper’s experiments. It compares the number of parameters, preprocessing time, training time, and testing time for each model. The time units are milliseconds per graph data point, averaged on the UKB dataset. It shows that while some models (Graphormer and NAGphormer) have fewer parameters, they require significantly more time in pre-processing, training, and testing. NeuroPath demonstrates efficiency in this regard.

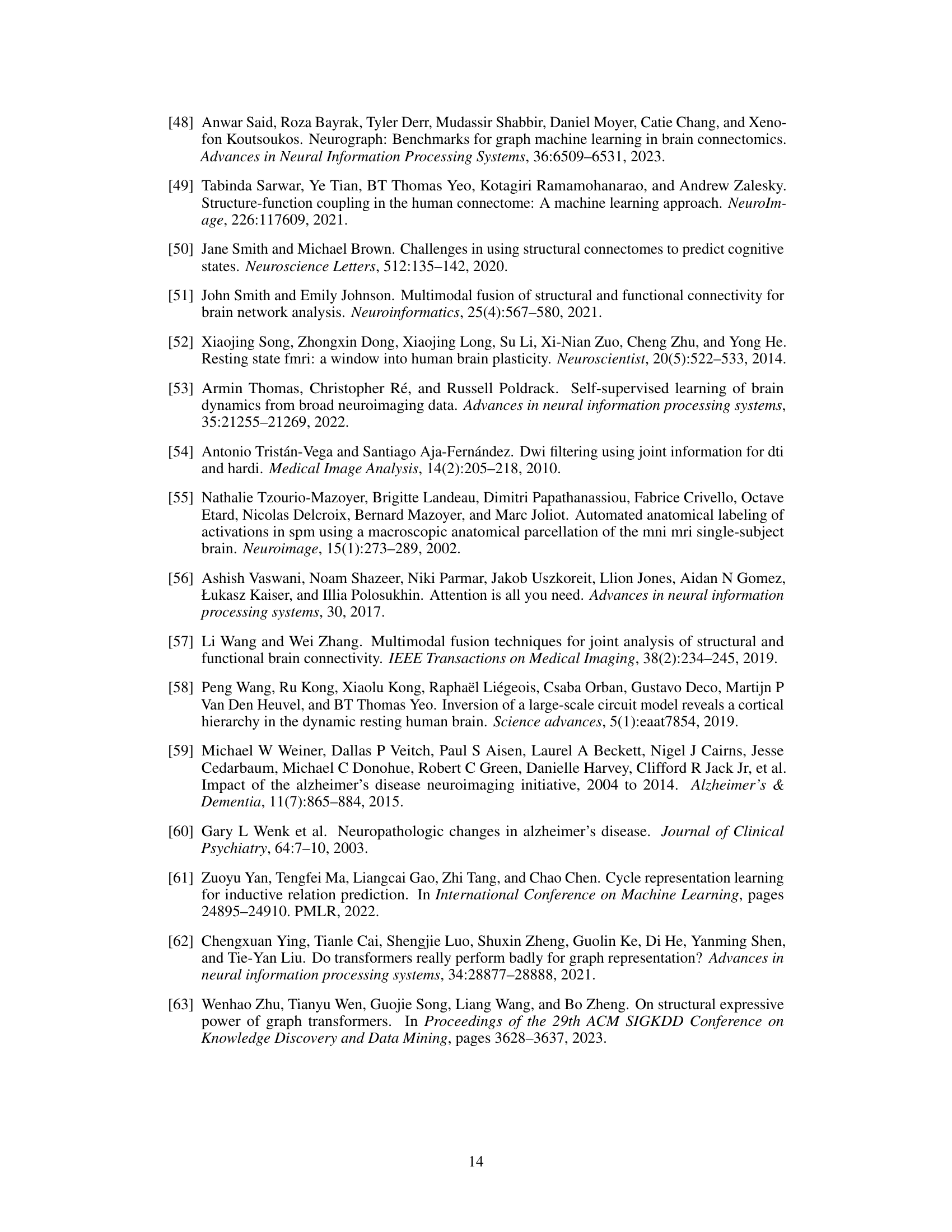

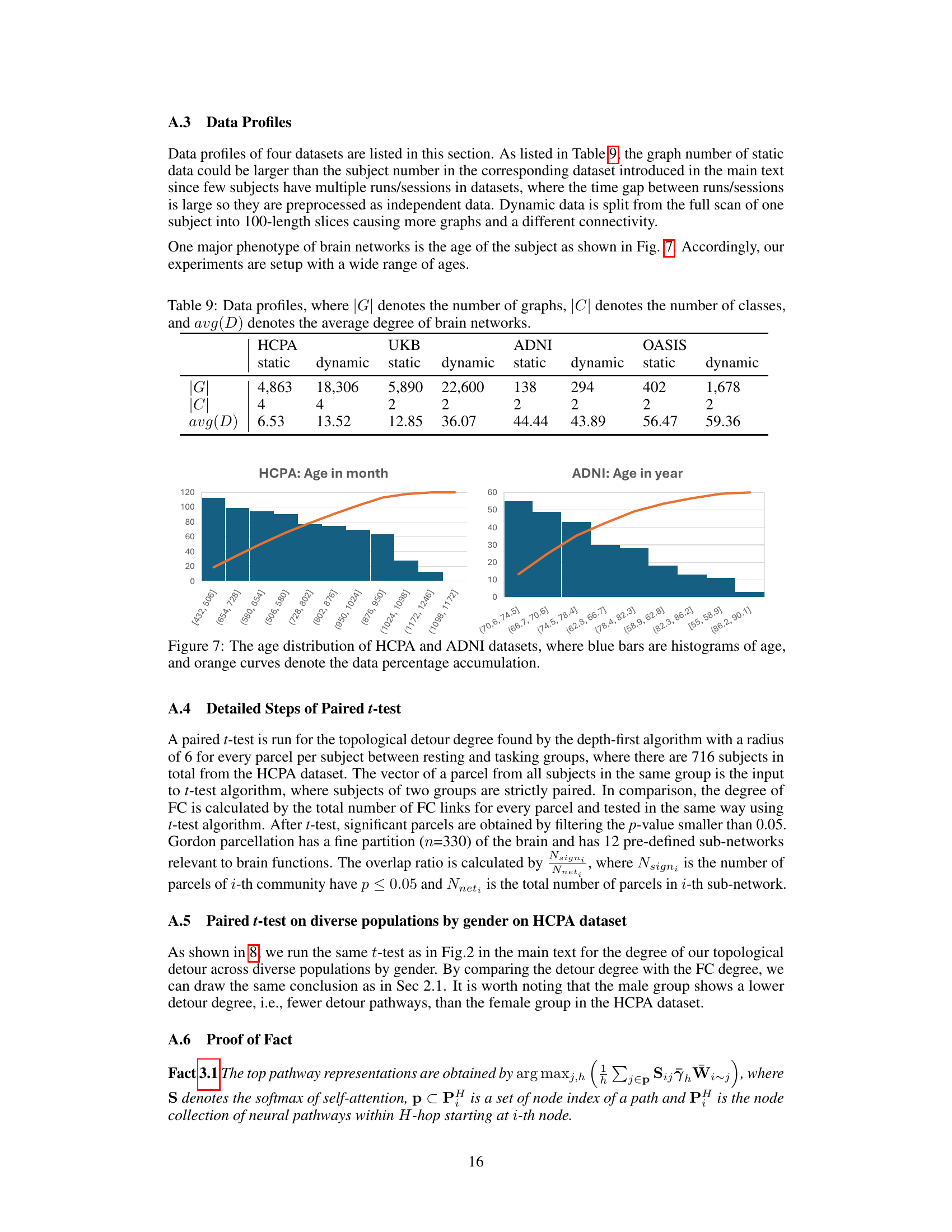

This table presents the characteristics of four different datasets used in the paper’s experiments: HCPA, UKB, ADNI, and OASIS. For each dataset, it shows the number of graphs (|G|), the number of classes (|C|) for the classification task, and the average degree (avg(D)) of the brain networks. The table is further divided into static and dynamic versions of each dataset, reflecting the different processing methods used. The average degree reflects the average number of connections per node in the brain network graph, providing information about network density.

Full paper#