↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current methods for visual grounding of dynamics struggle due to limitations of either purely neural or traditional physical simulators. Neural-network simulators (black boxes) may violate physics, while traditional ones (white boxes) use expert-defined equations that might not fully capture reality. This necessitates a more robust approach that combines the strengths of both.

The proposed NeuMA system addresses this challenge by integrating existing physical laws with learned corrections. This enables accurate learning of actual dynamics while retaining the generalizability and interpretability of physics-based models. NeuMA utilizes a particle-driven 3D Gaussian splatting variant (Particle-GS) for differentiable rendering, allowing back-propagation of image gradients to refine the simulation. Experiments show NeuMA excels in capturing intrinsic dynamics compared to existing techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer vision, robotics, and physics-based AI. It bridges the gap between neural network-based and physics-based simulators for visual grounding of dynamics, offering a novel approach that improves accuracy, generalizability, and interpretability. This work opens new avenues for research in material modeling, differentiable rendering, and long-term prediction of physical interactions from visual data.

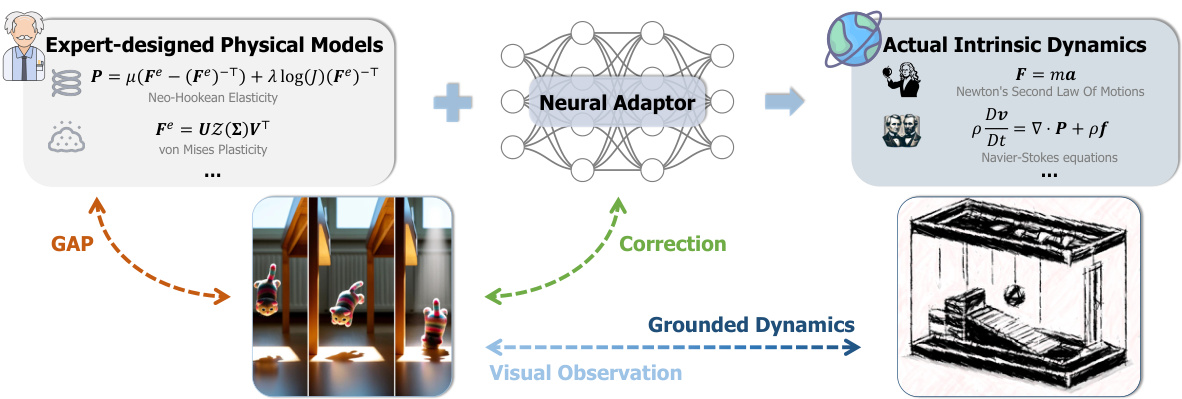

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the core concept of NeuMA. It shows how NeuMA integrates existing expert-designed physical models (e.g., Neo-Hookean elasticity, von Mises plasticity) with a learned neural adaptor. This adaptor corrects the expert models to better match actual intrinsic dynamics observed from visual data. The process involves a GAP (Grounding Adaptor Paradigm) which bridges expert knowledge with observations to generate grounded dynamics.

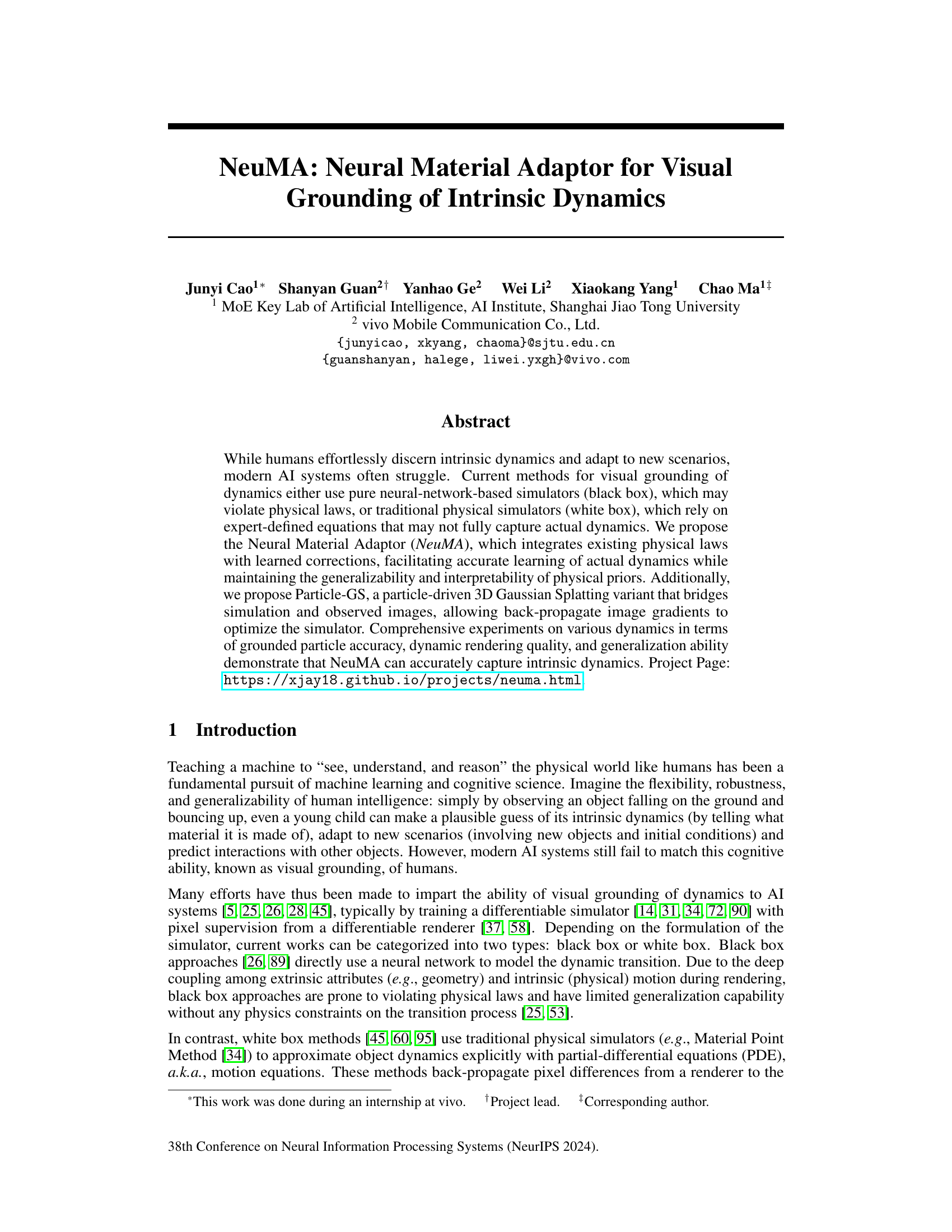

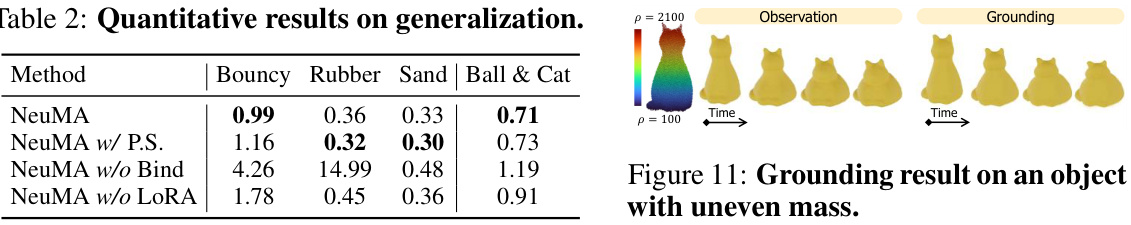

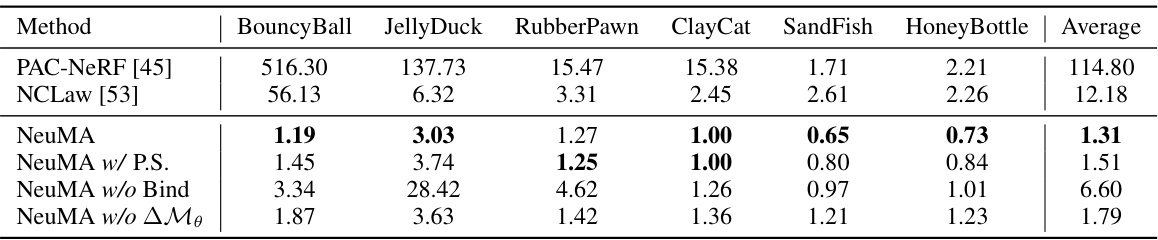

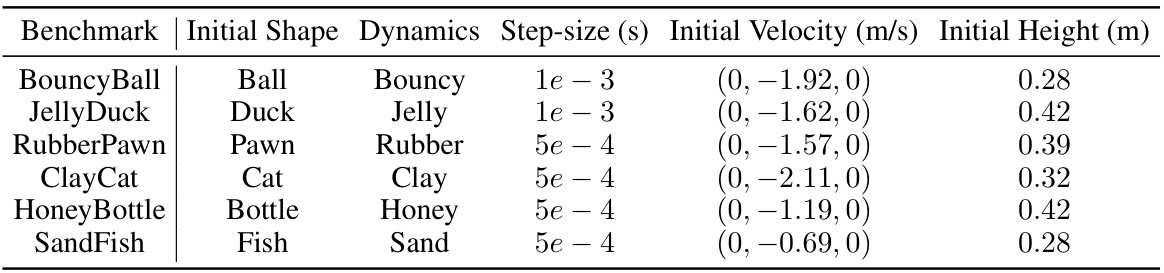

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for object dynamics grounding, specifically focusing on the Chamfer distance metric. The Chamfer distance measures the difference between the predicted particle positions from various methods and the ground truth particle positions. Lower Chamfer distance values indicate better performance. The methods compared include PAC-NeRF, NCLaw, and different variants of NeuMA (with and without particle supervision, binding, and the material adaptation term). The comparison is done across six different dynamic scenarios (‘BouncyBall’, ‘JellyDuck’, ‘RubberPawn’, ‘ClayCat’, ‘SandFish’, and ‘HoneyBottle’), providing a comprehensive evaluation of each method’s accuracy.

In-depth insights#

NeuMA’s Core Idea#

NeuMA’s core idea centers on bridging the gap between data-driven neural network approaches and physics-based simulation for visual grounding of dynamics. It leverages existing physical models (expert knowledge) as a foundation, but acknowledges their limitations in capturing real-world complexity. Therefore, NeuMA incorporates a learned ’neural adaptor’ that acts as a corrective term, refining the predictions of the physical models to better align with observed visual data. This approach cleverly balances the interpretability and generalizability of physical priors with the accuracy and flexibility of neural networks. The neural adaptor learns the residual difference between the expert model and the ground truth, allowing for accurate dynamics learning without completely abandoning physical principles. This results in a more accurate and robust representation of object dynamics and avoids the pitfalls of purely data-driven methods which may violate physical laws or lack generalizability.

Physics-Informed Priors#

The concept of “Physics-Informed Priors” in the context of visual grounding of intrinsic dynamics is crucial. It leverages the power of prior knowledge about physical laws to guide and constrain the learning process. Instead of relying solely on data-driven neural networks (which may violate physical realities), this approach intelligently integrates established physical models (e.g., Newtonian mechanics, elasticity) to provide a framework that respects physical constraints. This integration of prior knowledge with learned corrections offers several key benefits: improved accuracy, as the learning is guided towards physically plausible solutions; enhanced generalization, reducing overfitting and making the model more robust to unseen scenarios; and increased interpretability, providing insights into the learned dynamics and facilitating trust in the model’s predictions. However, a key challenge is achieving a balance between the strength of the physical prior and the model’s ability to capture nuances that aren’t fully captured by these established models. The effectiveness is heavily dependent on the accuracy of the chosen physical models, as inaccurate or incomplete models can significantly hinder performance and lead to misleading results. Furthermore, the method of incorporating this prior knowledge is critical; a poorly implemented approach could stifle the model’s ability to learn necessary corrections.

Particle-GS Renderer#

The Particle-GS renderer, a differentiable rendering technique, is a core component of the NeuMA framework for visual grounding of intrinsic dynamics. It bridges the gap between the physics simulation and visual observations, enabling backpropagation of image gradients to optimize the simulator’s parameters. This crucial step allows the system to learn accurate physical models from visual data. By using a particle-driven 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) approach, Particle-GS efficiently renders images based on predicted particle motions. This differentiability is key to the end-to-end training of NeuMA, and the particle-kernel binding mechanism enhances the accuracy and robustness of the rendering process. This clever design allows for accurate and physically plausible scene representation which avoids issues like unbalanced kernel distribution encountered in typical 3DGS approaches. The Particle-GS renderer’s ability to handle complex scenarios with deformable objects significantly contributes to NeuMA’s superior performance in visual grounding of dynamics.

Generalization Ability#

The research paper investigates the generalization ability of a novel neural material adaptor (NeuMA) for visual grounding of intrinsic dynamics. A key aspect is NeuMA’s capacity to extrapolate beyond the training data and accurately predict the behavior of objects with unseen shapes, materials, and initial conditions. Strong generalization is demonstrated through experiments involving diverse dynamic scenes, showing that NeuMA outperforms existing methods. This success is attributed to NeuMA’s integration of physical priors (expert knowledge) with learned corrections, making the model both accurate and robust. However, limitations exist, particularly concerning generalization to extremely novel scenarios involving substantially different physics. While the experiments showcase impressive results, further research could explore the boundaries of NeuMA’s generalization capacity, particularly with respect to handling unforeseen interactions and complex physics beyond the scope of the training data. Future work could involve more complex scenarios, with various types of material interactions and more sophisticated physical phenomena, and benchmark against the current cutting-edge models for a more complete analysis of its generalization capability.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more sophisticated material models, moving beyond the neo-Hookean and von Mises models used here. Incorporating more complex material behaviors, such as viscoelasticity or plasticity with yield surfaces, would enhance the realism and generalizability of the simulation. Improving the efficiency of the 3D Gaussian Splatting differentiable renderer is crucial for scalability to more complex scenes and longer time horizons. This could involve algorithmic optimizations or exploration of alternative differentiable rendering techniques. Another important direction is to address the limitations of the Particle-GS method. Further research could examine the particle binding mechanism to improve its robustness and accuracy in handling various dynamic scenarios. Expanding the types of dynamics considered is vital for assessing the full potential of the NeuMA framework. This could involve applying NeuMA to fluid dynamics, soft-body dynamics, or multi-phase flows. Finally, combining NeuMA with advanced AI techniques, such as reinforcement learning, could lead to systems capable of truly autonomous visual grounding of dynamics, allowing for more adaptive and intelligent behaviors in dynamic environments.

More visual insights#

More on figures

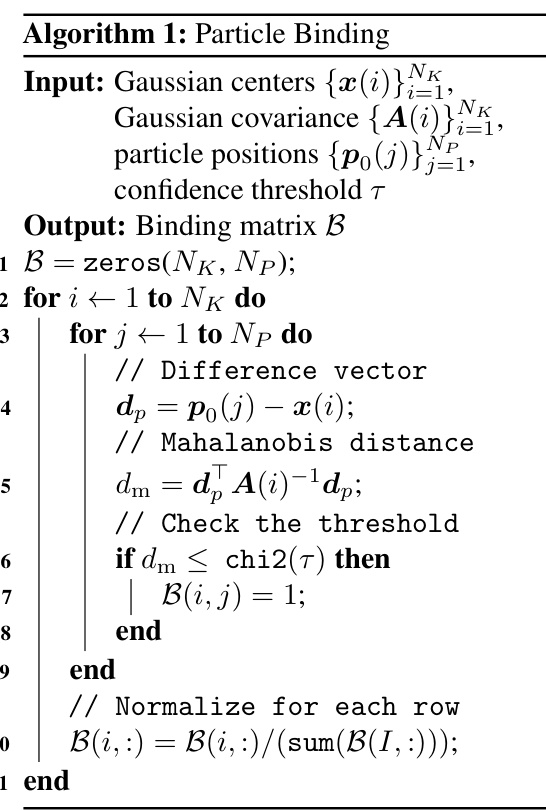

This figure shows the pipeline of NeuMA, which consists of three stages: Initial State Acquisition, Physics Simulation, and Dynamic Scene Rendering. In the first stage, 3D Gaussian kernels are reconstructed from multi-view images, and particles are sampled and bound to these kernels. The second stage involves physics simulation using the Neural Material Adaptor (NeuMA) which combines physical laws and learned corrections to estimate dynamics. Finally, the third stage renders 2D images by deforming the Gaussian kernels based on the simulation results, allowing for end-to-end training with pixel supervision.

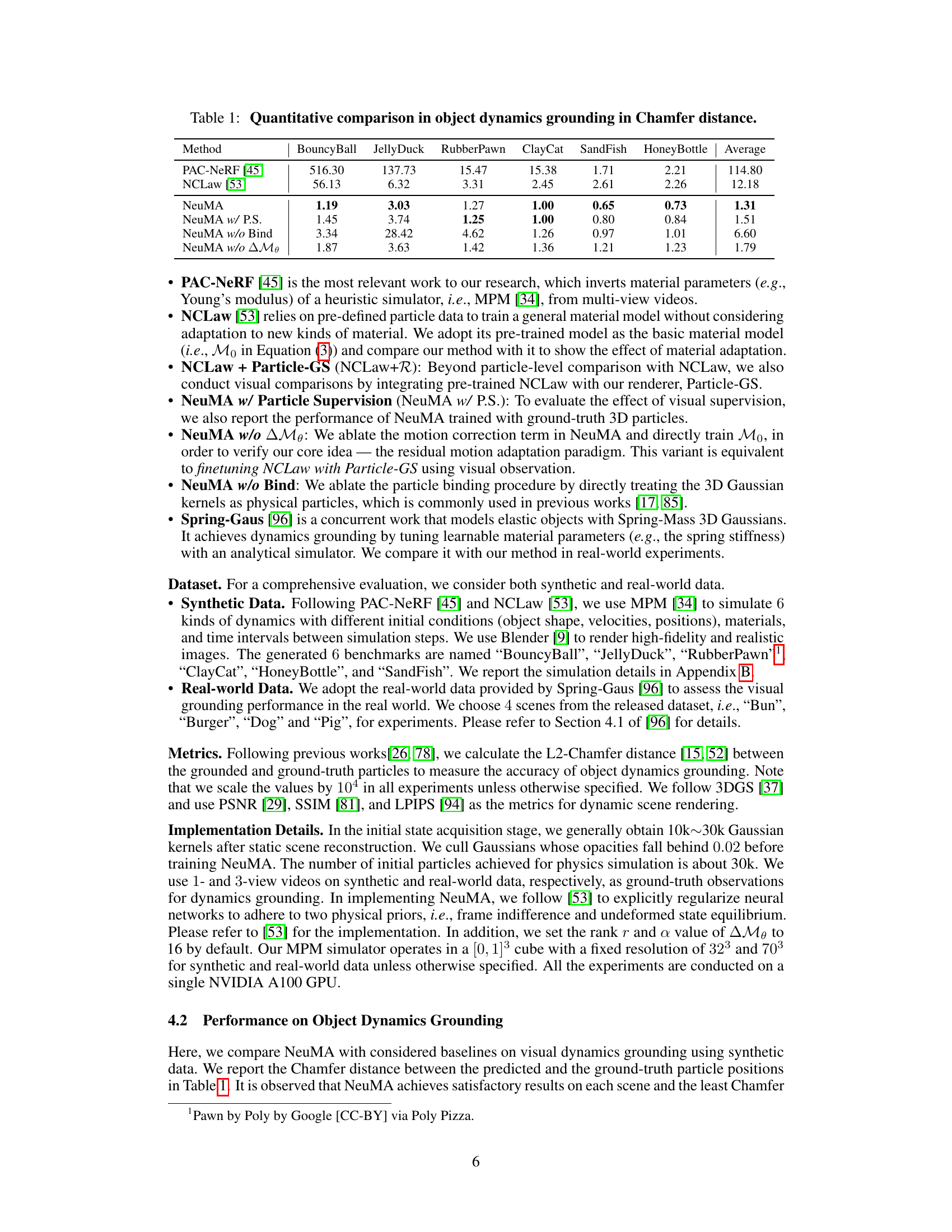

This figure compares the performance of different methods (NCLaw, NeuMA, NeuMA with particle supervision, NeuMA without binding, and NeuMA without the correction term) for object dynamics grounding across the entire simulation sequence. Each subplot represents a different dynamic scene (BouncyBall, JellyDuck, RubberPawn, ClayCat, SandFish, HoneyBottle). The y-axis shows the Chamfer distance, a measure of the difference between the predicted and ground-truth particle positions, and the x-axis represents the time step. This visualization provides a detailed comparison of the methods’ ability to accurately track object motion over time in various dynamic settings.

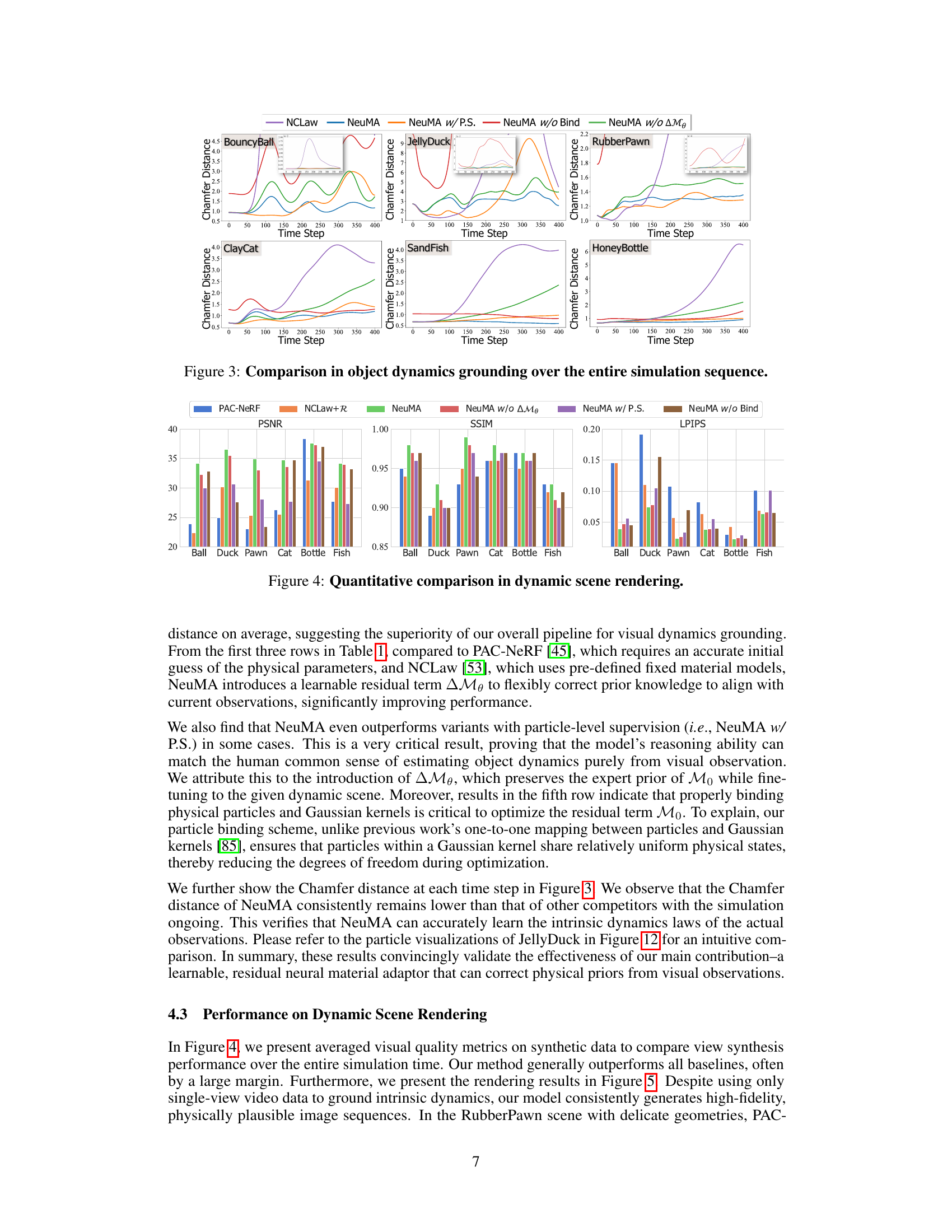

This figure presents a quantitative comparison of dynamic scene rendering performance using different metrics (PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS) for various methods: PAC-NeRF, NCLaw+R, NeuMA, and its ablation variants (NeuMA w/o ΔΜθ, NeuMA w/ P.S., NeuMA w/o Bind). The bar chart visualizes the performance across six different dynamic scenes: BouncyBall, JellyDuck, RubberPawn, ClayCat, SandFish, and HoneyBottle. This allows for a detailed analysis of the impact of different components of NeuMA and comparison against existing state-of-the-art methods.

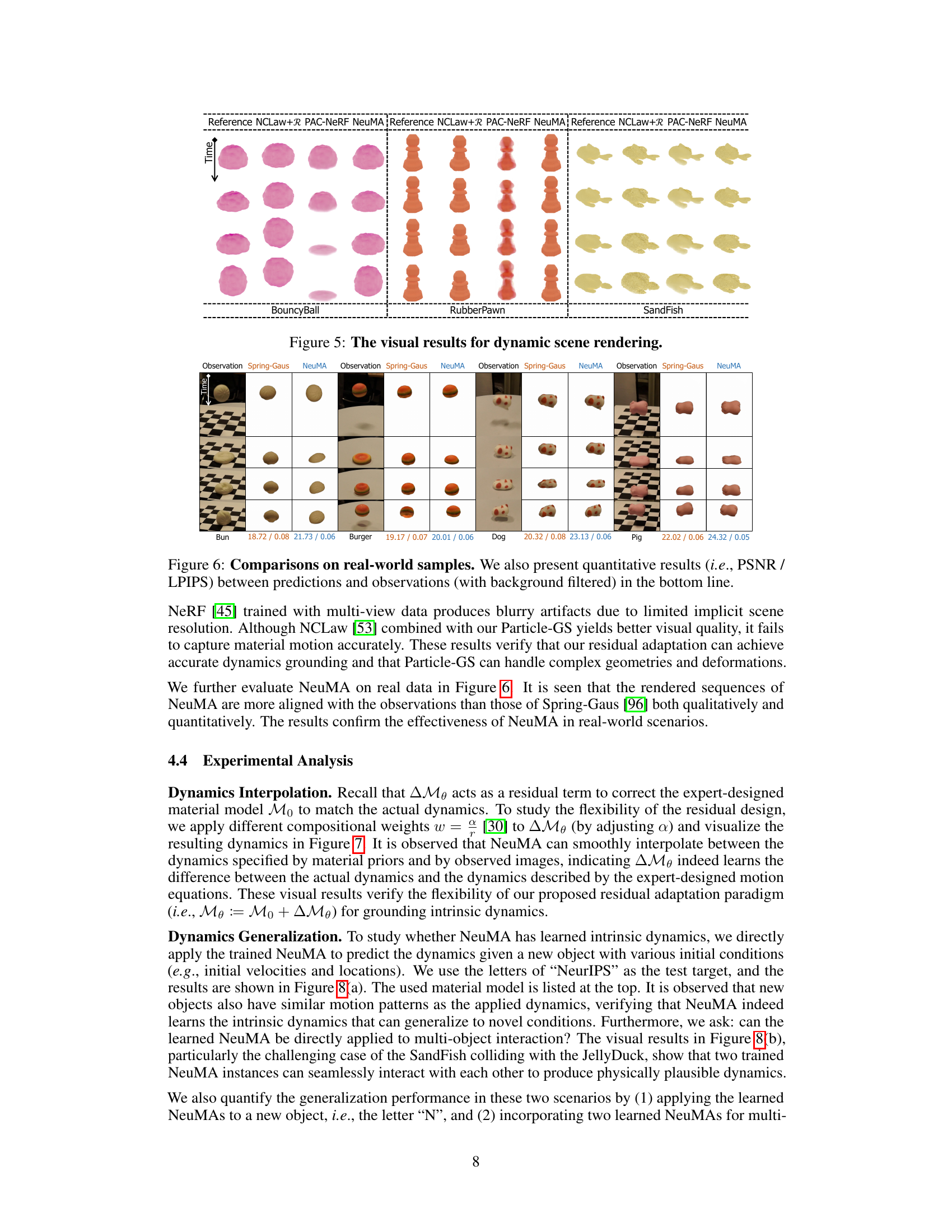

This figure shows a comparison of dynamic scene rendering results between different methods: Reference, NCLaw+R, PAC-NeRF, and NeuMA. For each method, multiple frames of the simulation are shown for three different objects: BouncyBall, RubberPawn, and SandFish. A second row of images provides a comparison of results for real-world scenarios using the Bun, Burger, Dog, and Pig datasets, comparing Spring-Gaus and NeuMA results against the observations.

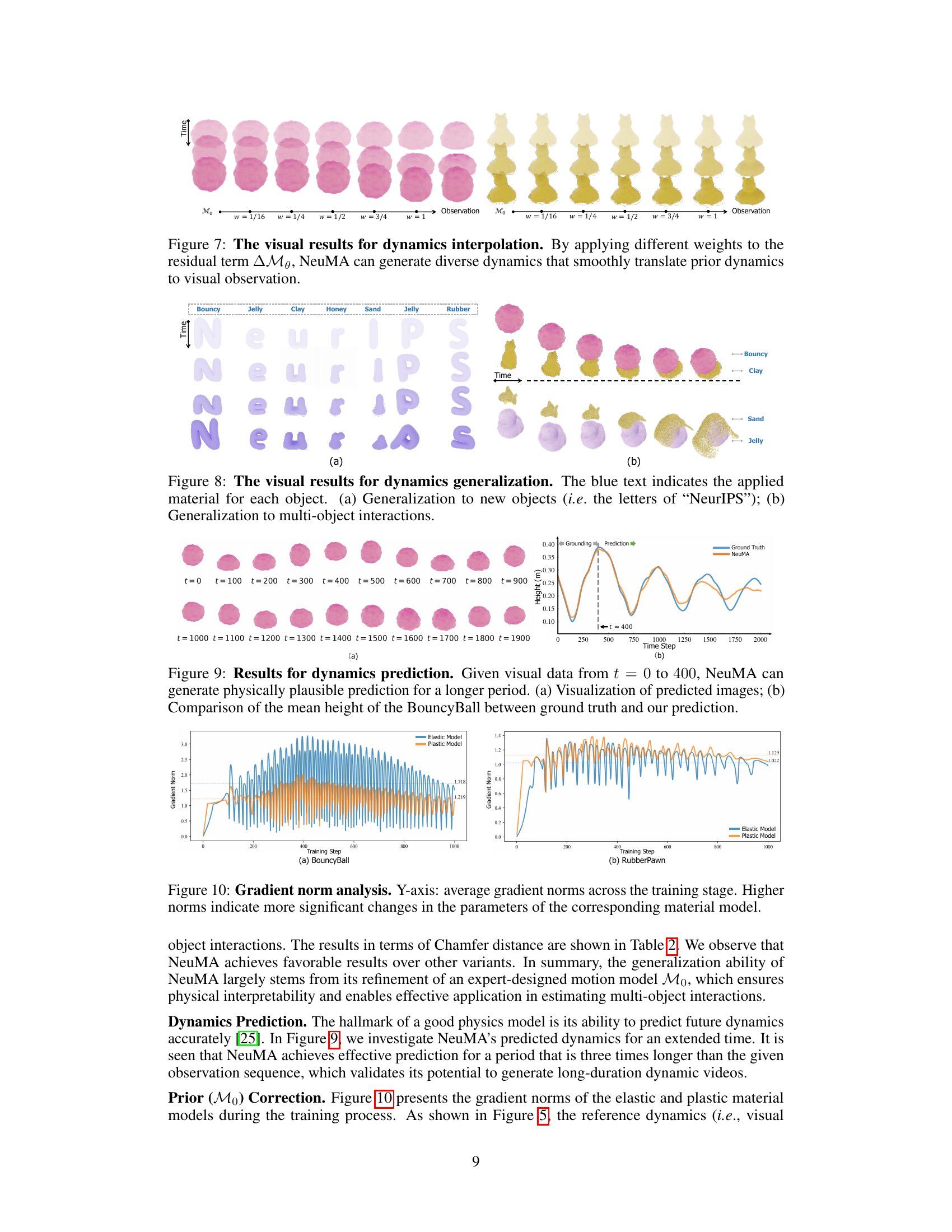

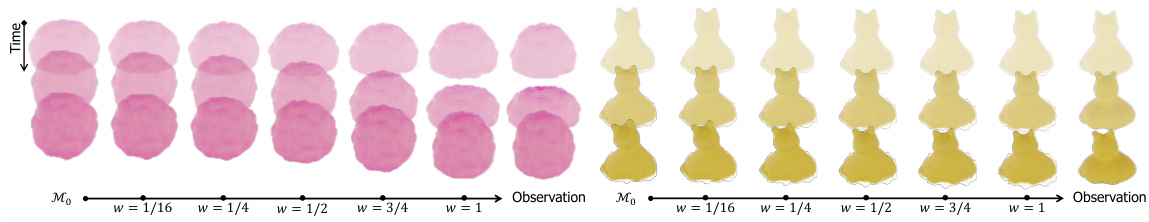

This figure shows the results of applying different weights to the residual term (ΔMθ) in the NeuMA model. It demonstrates the model’s ability to smoothly interpolate between dynamics specified by prior knowledge (M₀) and those observed in the visual data. The left side shows the results for a pink object, while the right shows the results for a yellow object. Each column represents a different weight applied to the residual term, ranging from 1/16 to 1, showcasing the range of dynamic behaviors the model can generate.

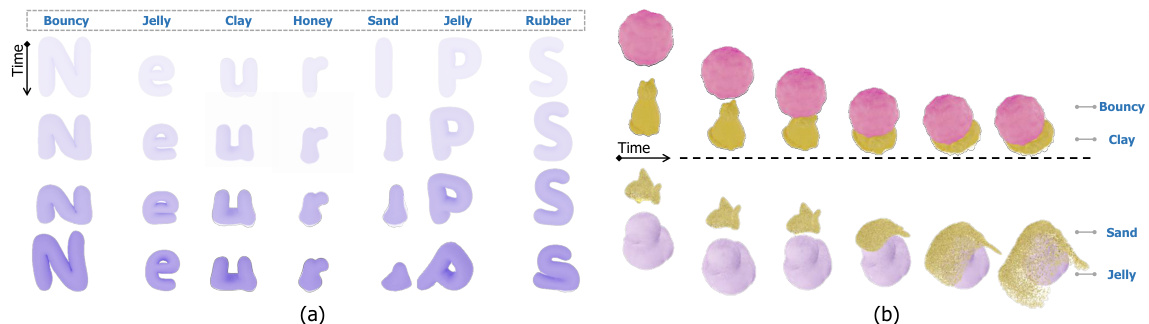

This figure demonstrates the generalization capabilities of the NeuMA model. Subfigure (a) shows the application of the model to novel shapes (the letters of ‘NeurIPS’), indicating the model’s ability to predict dynamics across different objects, with the blue text specifying the material type used for each letter. Subfigure (b) showcases the model’s performance in simulating multi-object interactions, specifically a collision scenario between different materials. The successful generalization highlights NeuMA’s ability to adapt to unseen scenarios and interactions.

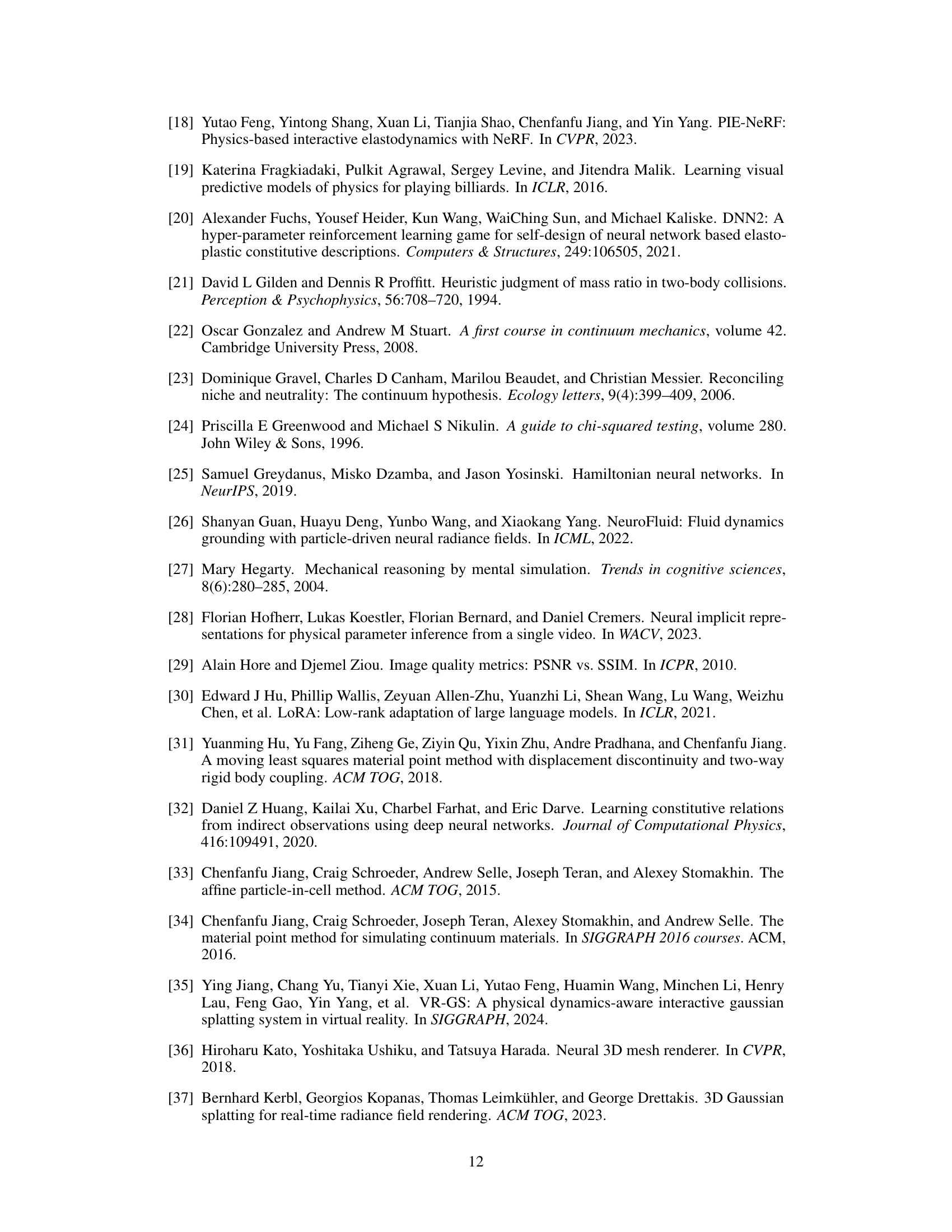

This figure demonstrates the long-term prediction capability of the NeuMA model. Given only the first 400 time steps of visual data, NeuMA can accurately predict the BouncyBall’s height for a substantially longer duration. The figure shows the predicted images (a) and a quantitative comparison of the predicted height versus the ground truth (b). This highlights NeuMA’s ability to extrapolate beyond the observed data and generate physically plausible predictions.

This figure shows the gradient norms of the elastic and plastic material models during the training process for two different objects: BouncyBall and RubberPawn. Higher gradient norms indicate that the model’s parameters are changing more significantly during training, suggesting that the model is learning more effectively in those areas. The plots visualize how the learning process focuses on adjusting the parameters of either the elastic or plastic model depending on the object’s behavior. The consistent oscillatory pattern might highlight some challenges or periodic updates during training.

This figure shows the results of applying NeuMA to an object with uneven mass distribution. The left side shows the observation (input) sequence, while the right illustrates the dynamics generated by NeuMA. The color gradients on the leftmost object indicate the uneven mass distribution. The results demonstrate NeuMA’s ability to handle complex mass distributions.

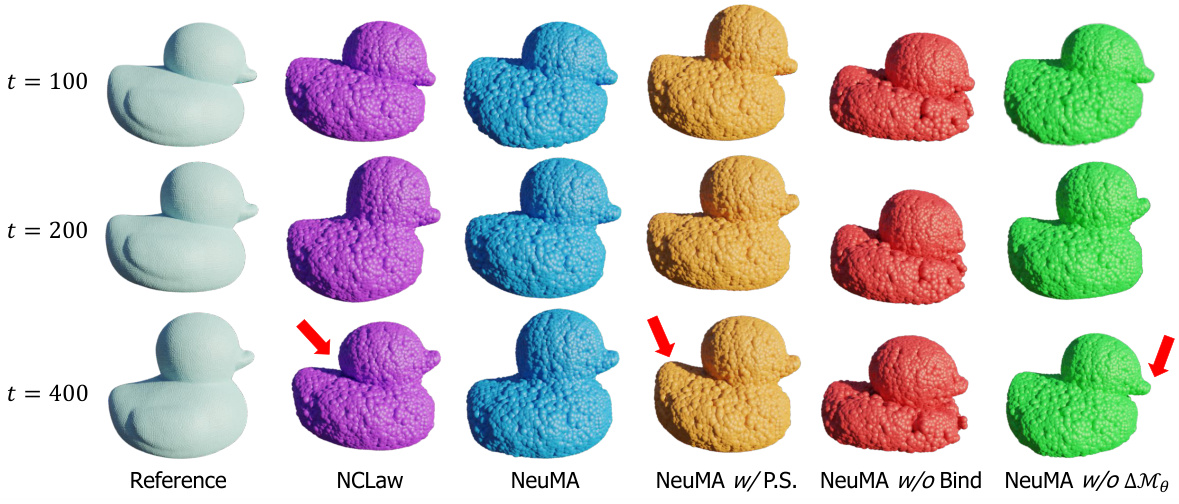

This figure visualizes the simulated particles of a JellyDuck at different time steps (t=100, t=200, t=400) using different methods: Reference (ground truth), NCLaw (physics-informed model), NeuMA (proposed method), NeuMA w/ P.S. (NeuMA with particle supervision), NeuMA w/o Bind (NeuMA without particle binding), and NeuMA w/o ΔMθ (NeuMA without the neural material adaptor). The visualization highlights the differences in the accuracy and realism of the simulation results obtained by each method. Notably, the red arrows point out discrepancies between the results obtained and the reference. The visualization clearly shows how NeuMA effectively captures the dynamics of the JellyDuck, while other methods exhibit various degrees of artifacts and inaccuracies.

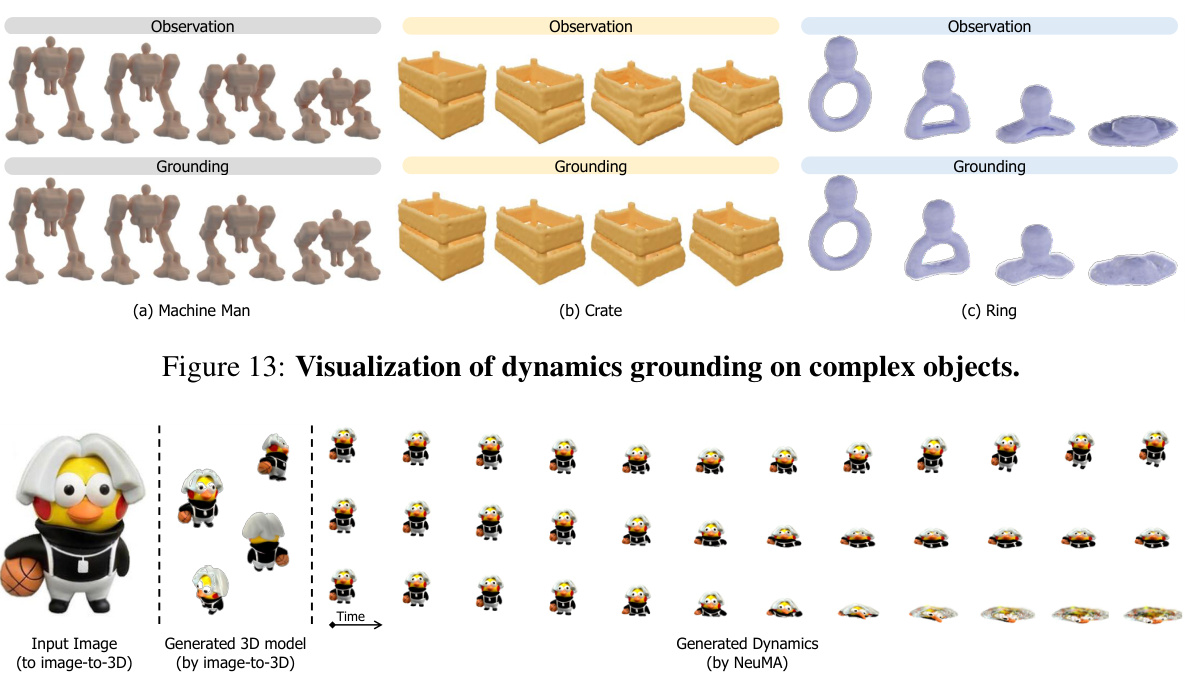

This figure demonstrates the results of applying NeuMA to complex objects with diverse shapes and properties. The three columns showcase the results for (a) Machine Man, (b) Crate, and (c) Ring. For each object, the leftmost image shows the observation (input video frames), and the rightmost image shows the results of generating the dynamics using NeuMA, with the intermediate step of generating the 3D model in the middle. This visual comparison highlights NeuMA’s ability to successfully ground the intrinsic dynamics of various objects.

More on tables

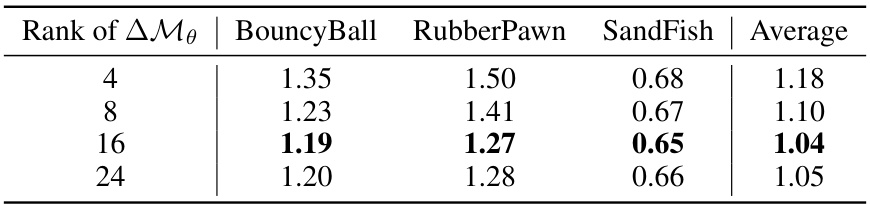

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for object dynamics grounding, using the Chamfer distance as a metric. The methods compared include PAC-NeRF, NCLaw, and three variants of the proposed NeuMA model (NeuMA, NeuMA with particle supervision, NeuMA without binding, and NeuMA without the material adaptation term). The comparison is done across six different benchmarks representing various dynamic scenarios (BouncyBall, JellyDuck, RubberPawn, ClayCat, SandFish, and HoneyBottle), with the average Chamfer distance reported for each method across all benchmarks. Lower Chamfer distance indicates better performance in accurately capturing the object’s dynamics.

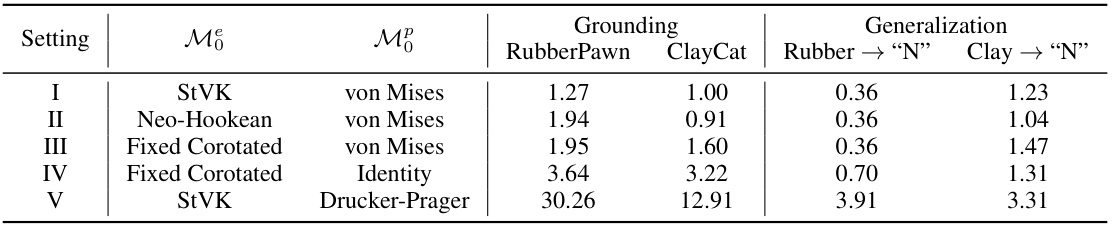

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the generalization performance of different variants of the NeuMA model. It shows the Chamfer distance, a metric measuring the accuracy of object dynamics grounding, for five different settings. Each setting represents a different combination of elastic (Moe) and plastic (Mop) material models used as priors. The results demonstrate the impact of different choices of these priors on the model’s ability to generalize to unseen objects and multi-object interactions.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for object dynamics grounding, specifically measuring the Chamfer distance. The methods compared include PAC-NeRF, NCLaw, and NeuMA (with several variations). The Chamfer distance is calculated for six different benchmarks: BouncyBall, JellyDuck, RubberPawn, ClayCat, SandFish, and HoneyBottle. Lower Chamfer distance indicates better performance in accurately capturing object dynamics.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for object dynamics grounding, evaluated using the Chamfer distance metric. The methods compared include PAC-NeRF, NCLaw, and different variants of the proposed NeuMA method. The Chamfer distance is calculated for six different dynamic scenes: BouncyBall, JellyDuck, RubberPawn, ClayCat, SandFish, and HoneyBottle. Lower Chamfer distances indicate better performance.

Full paper#