↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Self-Supervised Learning Representations (SSLRs) have revolutionized speech processing, but they often struggle with multilingual scenarios and low-resource languages. Standard fine-tuning methods can also lead to overfitting and high computational costs. Existing adaptation methods often fail to transfer well to unseen tasks.

The proposed Condition-Aware Self-Supervised Learning Representation (CA-SSLR) model addresses these issues by integrating language and speaker embeddings from earlier layers, enabling dynamic adjustments to internal representations without significantly altering the original model. CA-SSLR uses a hierarchical conditioning approach with limited trainable parameters, which mitigates overfitting and excels in under-resourced and unseen tasks. The experimental results demonstrate notable performance improvements in various multilingual speech tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in speech processing because it introduces a novel and efficient method for improving the performance of self-supervised learning (SSL) models on various speech tasks. CA-SSLR significantly enhances the generalizability of SSL models, addresses the challenges of multilingual and low-resource speech processing, and reduces computational costs. The proposed method opens new avenues for developing robust and efficient speech processing systems and has broader implications for various related fields.

Visual Insights#

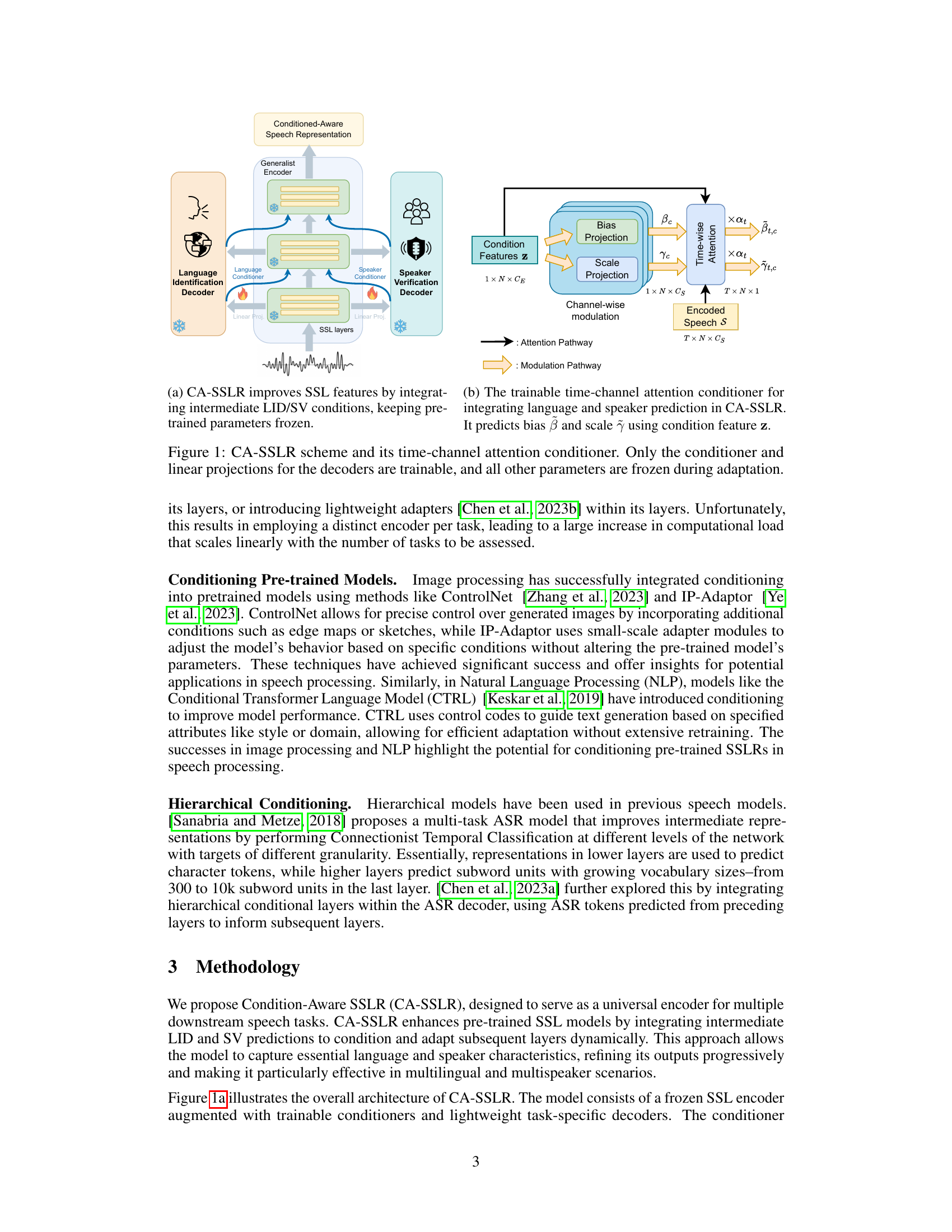

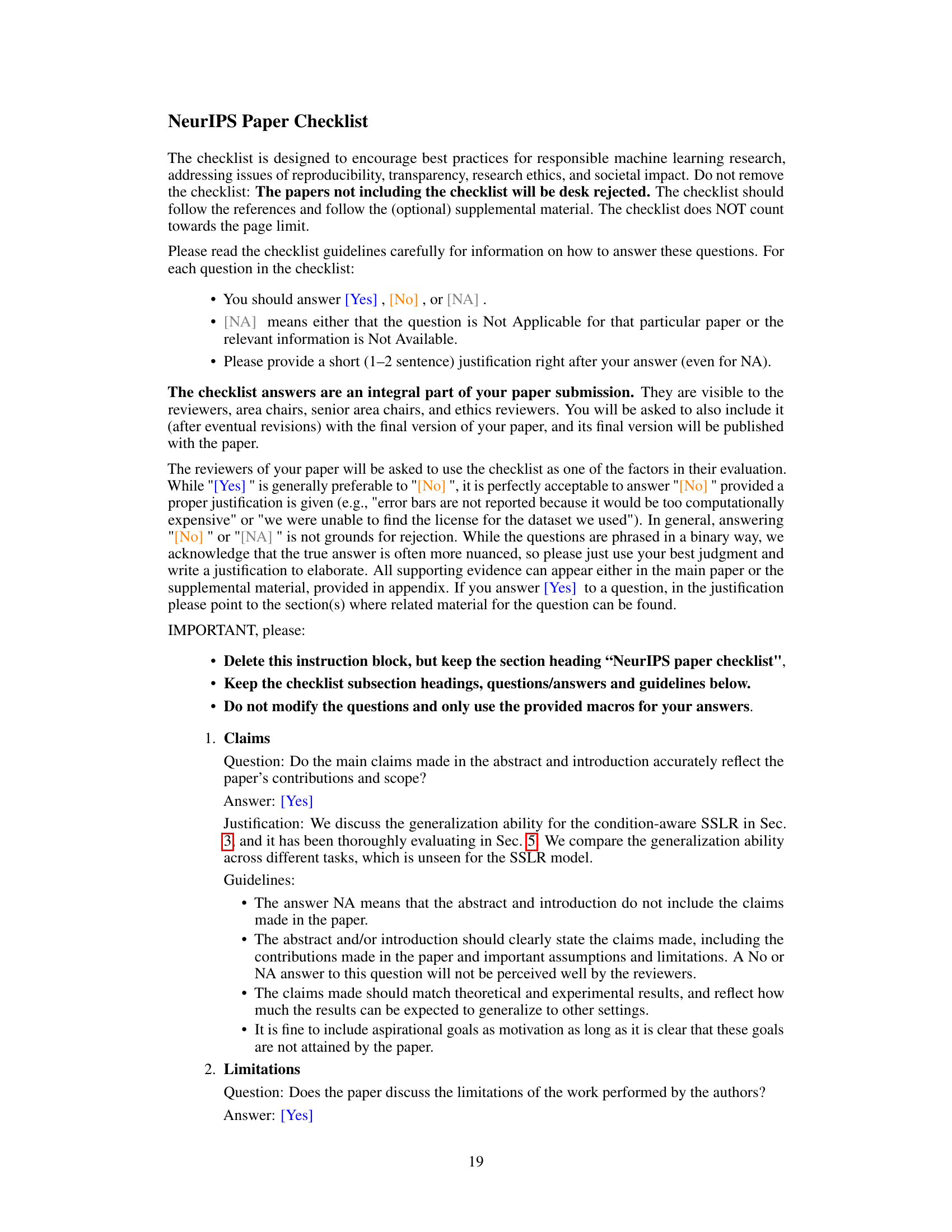

This figure shows the architecture of the CA-SSLR model and a detailed view of its time-channel attention conditioner. The main model consists of a generalist encoder (a pre-trained SSL model whose weights remain frozen during adaptation) that receives speech input. The encoder’s output is fed into multiple conditional adapters, one each for language identification and speaker verification. These adapters use intermediate embeddings from earlier layers to dynamically adjust internal representations of the encoder. The figure also highlights that only the conditioner and decoder projections are trainable during adaptation; other encoder weights remain frozen, preventing catastrophic forgetting.

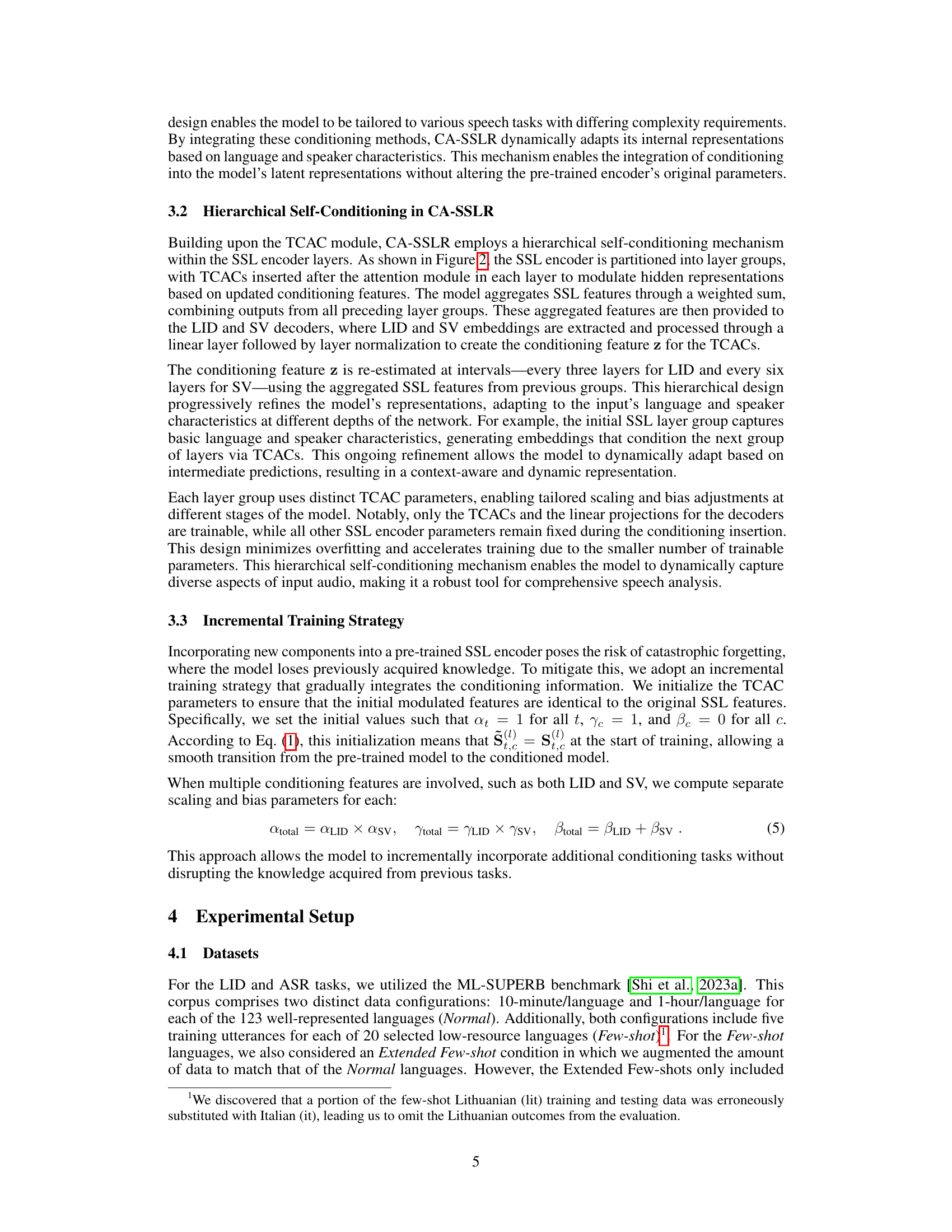

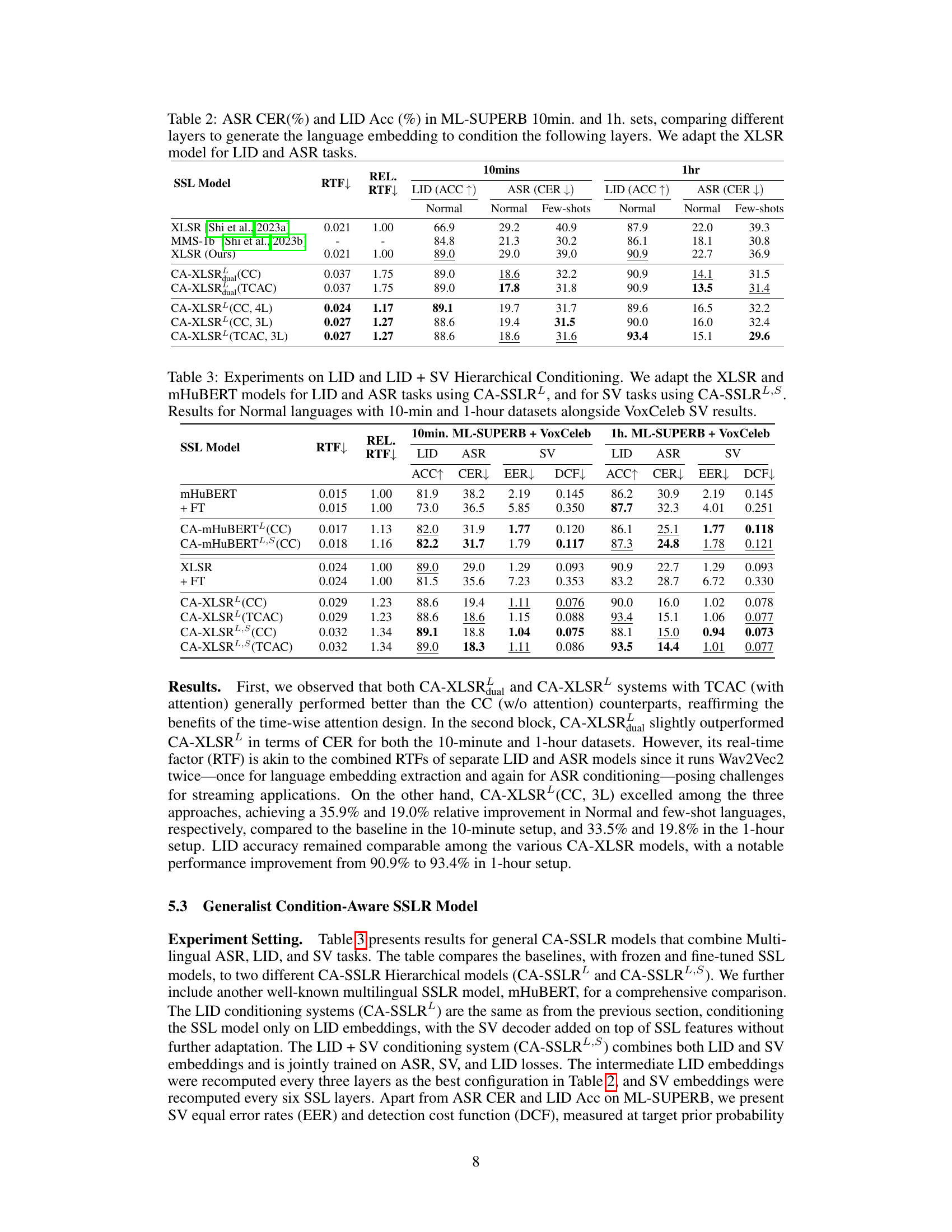

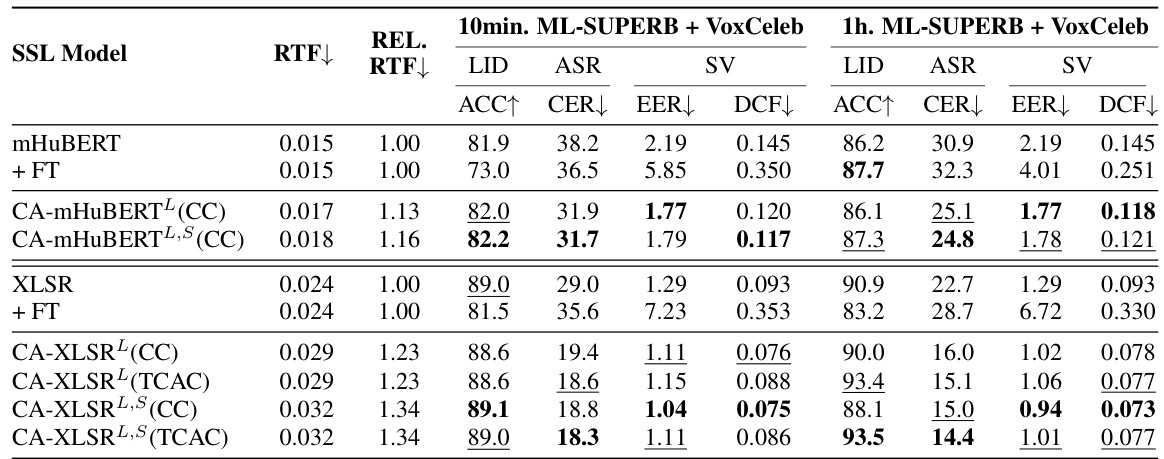

This table presents the results of evaluating adapted XLSR models on three different tasks: Language Identification (LID), Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), and Speaker Verification (SV). The models were initially adapted for either LID or ASR and then evaluated on both the adapted task and a task they weren’t trained for. The purpose is to demonstrate how well the adapted encoder generalizes to unseen tasks without any further fine-tuning. The table shows LID accuracy and ASR Character Error Rate (CER) for both normal and few-shot conditions (for LID and ASR) and Speaker Verification Equal Error Rate (EER) for SV. Bottleneck dimensions of the adapted models are also included.

In-depth insights#

CA-SSLR: Overview#

CA-SSLR, or Condition-Aware Self-Supervised Learning Representation, presents a novel approach to generalized speech processing. It addresses the limitations of traditional fine-tuning methods by integrating language and speaker embeddings into earlier layers of a pre-trained self-supervised model. This allows the model to understand the context of the audio input, reducing reliance on the raw audio features. The key innovation is the use of linear modulation to dynamically adjust internal representations, enabling fine-grained adaptability without significant changes to the original model’s behavior. This approach leads to improved performance across various speech tasks, such as Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), Speaker Verification (SV), and Language Identification (LID), particularly in low-resource scenarios and with unseen tasks. The hierarchical conditioning mechanism enhances this dynamic adaptation, with minimal additional training required. By preserving pre-trained weights while utilizing efficient parameterization, CA-SSLR mitigates overfitting and reduces the number of trainable parameters, resulting in a computationally efficient and versatile approach to multilingual and multi-speaker speech processing.

Conditional Adapters#

Conditional adapters are modules designed to dynamically adjust a pre-trained model’s behavior without modifying its core parameters. They offer a parameter-efficient way to specialize a general-purpose model for specific tasks or conditions, such as different languages or speakers in speech processing. By injecting these adapters into various layers of the pre-trained model, a hierarchical approach can be used to refine the model’s internal representations progressively, adapting to specific input characteristics at each stage. This technique avoids catastrophic forgetting, where the model loses previously acquired knowledge. The adapters leverage lightweight mechanisms like linear modulation or attention-based conditioning to efficiently modulate activations, making them particularly suitable for low-resource settings. The modular design facilitates easy integration with diverse downstream tasks, enabling rapid adaptation without the computationally expensive process of full fine-tuning. The effectiveness of conditional adapters hinges on their ability to capture essential contextual information and dynamically adjust model responses, offering a crucial mechanism for generalizing pretrained models.

Multitask Learning#

Multitask learning (MTL) aims to improve the learning efficiency and generalization performance of machine learning models by training them on multiple related tasks simultaneously. The core idea is that sharing representations across tasks can leverage commonalities and reduce overfitting, leading to better performance on individual tasks, especially in low-resource scenarios. In the context of speech processing, MTL is particularly relevant due to the inherent relationships between tasks like speech recognition, speaker identification, and language identification. A key advantage is that MTL can address the scarcity of labeled data for certain tasks by leveraging information from other, more readily available, related tasks. This is crucial in handling multilingual and low-resource language settings where extensive labeled data may be limited. However, careful consideration is needed to avoid negative transfer, where the shared representations hinder the performance of individual tasks. Careful model design, including appropriate task weighting and architectural choices, is essential for successful MTL implementations. Moreover, the selection of related tasks is also important; tasks that are too dissimilar can negatively impact performance. Future research should focus on developing more robust and adaptable MTL architectures capable of handling increasingly diverse and complex speech processing tasks.

Generalization Ability#

The study’s focus on “Generalization Ability” is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of the proposed CA-SSLR model. The core idea is to assess how well the model performs on unseen tasks, which is vital for establishing its true generalizability. The authors achieve this through a set of experiments, comparing CA-SSLR against traditional fine-tuning (FT) and adapter methods. This rigorous comparison aims to demonstrate that CA-SSLR achieves superior performance on unseen tasks, highlighting its robustness and broad applicability. The results clearly show a significant advantage for CA-SSLR, particularly in low-resource settings, indicating that the model is less prone to overfitting and can better leverage knowledge from pre-training. This emphasis on generalization is essential because it demonstrates the model’s practical value beyond simple benchmark performance; it suggests that the model is truly adaptable and can be effectively applied to diverse real-world speech processing tasks.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more sophisticated conditioning mechanisms beyond simple linear modulation, perhaps incorporating attention or more complex neural networks to better capture the nuances of language and speaker variations. Investigating alternative architectural designs for integrating conditioning, such as parallel processing pathways or residual connections, could improve performance and efficiency. A broader range of downstream tasks should be explored, extending beyond the initial set of ASR, LID, and SV to encompass tasks like speech translation, speech synthesis, and voice conversion. Finally, rigorous analysis of the model’s biases and potential societal impact, including fairness and equity concerns in multilingual scenarios, will be crucial for responsible development and deployment. In addition, enhancing multilingual capabilities by exploring novel pre-training strategies and incorporating more diverse languages into the training data could significantly impact model robustness and generalization capabilities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the hierarchical self-conditioning mechanism in the CA-SSLR model. The SSL encoder is divided into layer groups, and TCACs are inserted after the attention module in each layer to modulate hidden representations based on updated conditioning features from LID and SV decoders. The model aggregates SSL features through a weighted sum, combining outputs from all preceding layer groups. These features are fed into the LID and SV decoders, which extract and process the information to create conditioning features for the TCACs. The process is repeated at intervals, refining representations and dynamically adapting to language and speaker characteristics. The figure highlights that only the TCACs and the linear projections for decoders are trainable, while pre-trained encoder weights remain fixed.

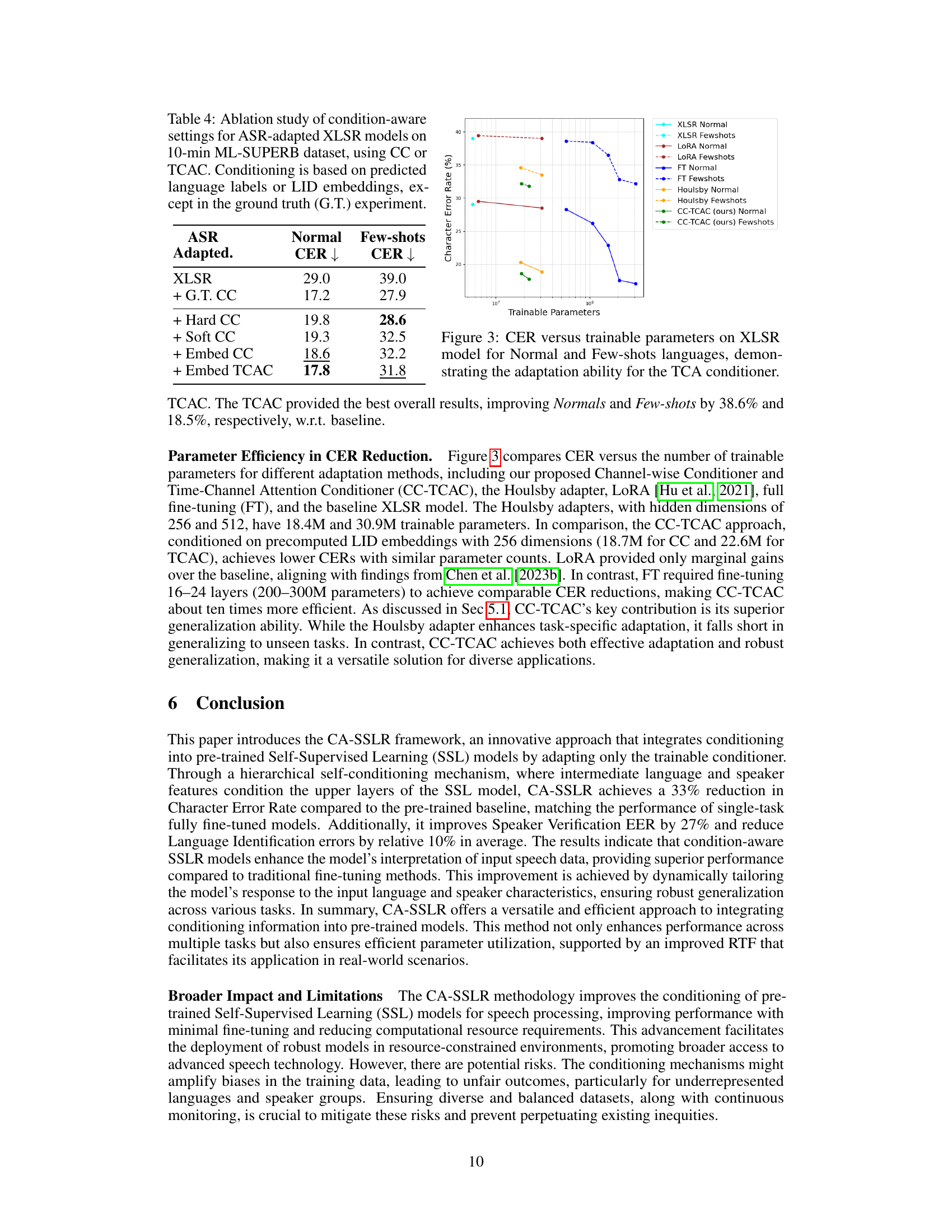

This figure compares the character error rate (CER) achieved by different model adaptation methods against the number of trainable parameters used. The methods compared include full fine-tuning (FT), Houlsby adapters, LoRA, and the proposed method (CC-TCAC). The results are shown separately for datasets with normal and few-shot languages, demonstrating the impact of the adaptation techniques on both well-resourced and low-resource scenarios. The figure highlights that the CC-TCAC method achieves low CERs with relatively few trainable parameters.

More on tables

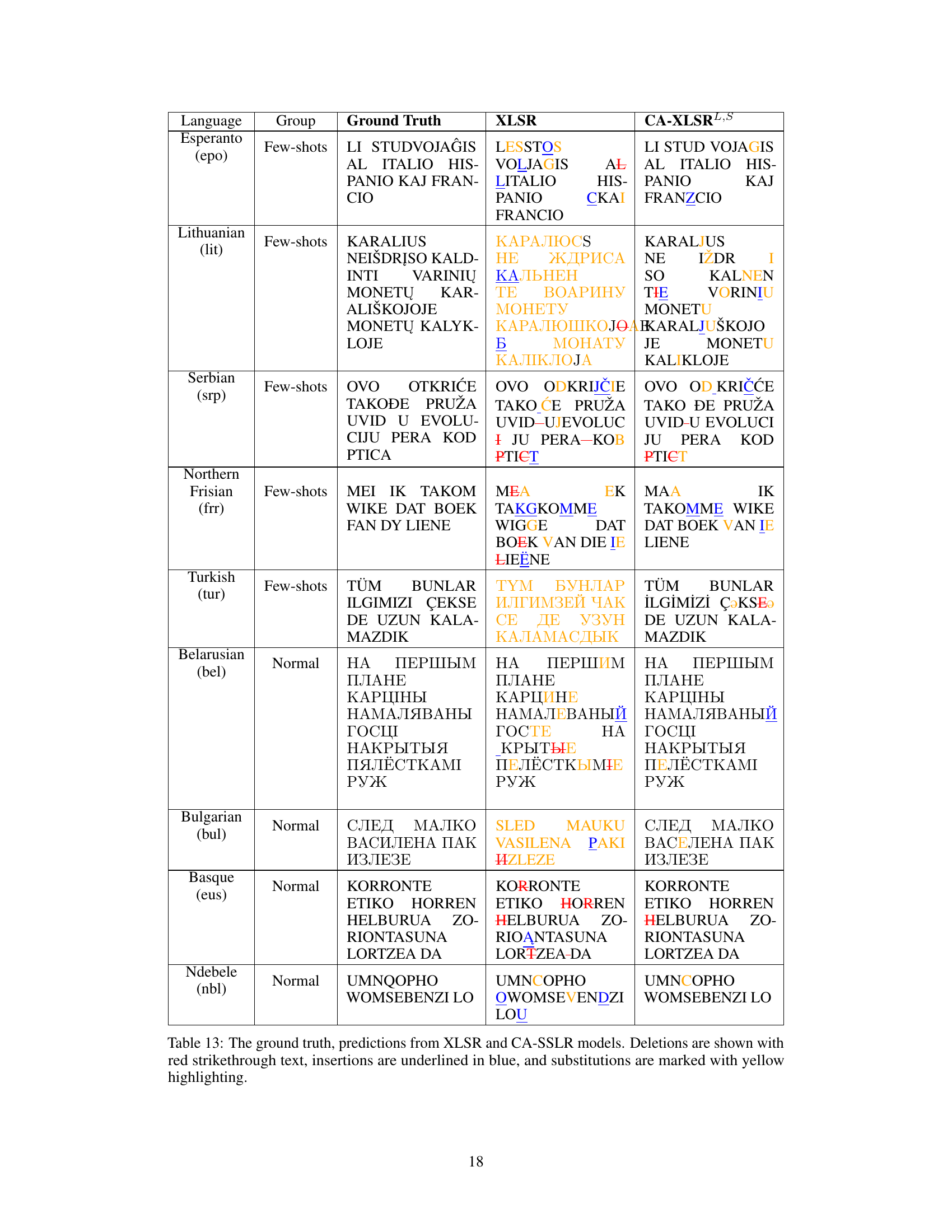

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the generalization ability of adapted XLSR models on three speech processing tasks: Language Identification (LID), Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), and Speaker Verification (SV). The models were adapted for either LID or ASR and then evaluated on both the adapted task and an unseen task. The table shows the performance metrics for each task (LID accuracy, ASR Character Error Rate (CER), and SV Equal Error Rate (EER) and Detection Cost Function (DCF)) for both ’normal’ (10 minutes of data per language) and few-shot (five utterances per language) conditions. The ‘Bottleneck Dims’ column shows the dimensionality of the bottleneck layers used in the adaptation methods. The results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed CA-XLSR model in achieving strong generalization across different tasks.

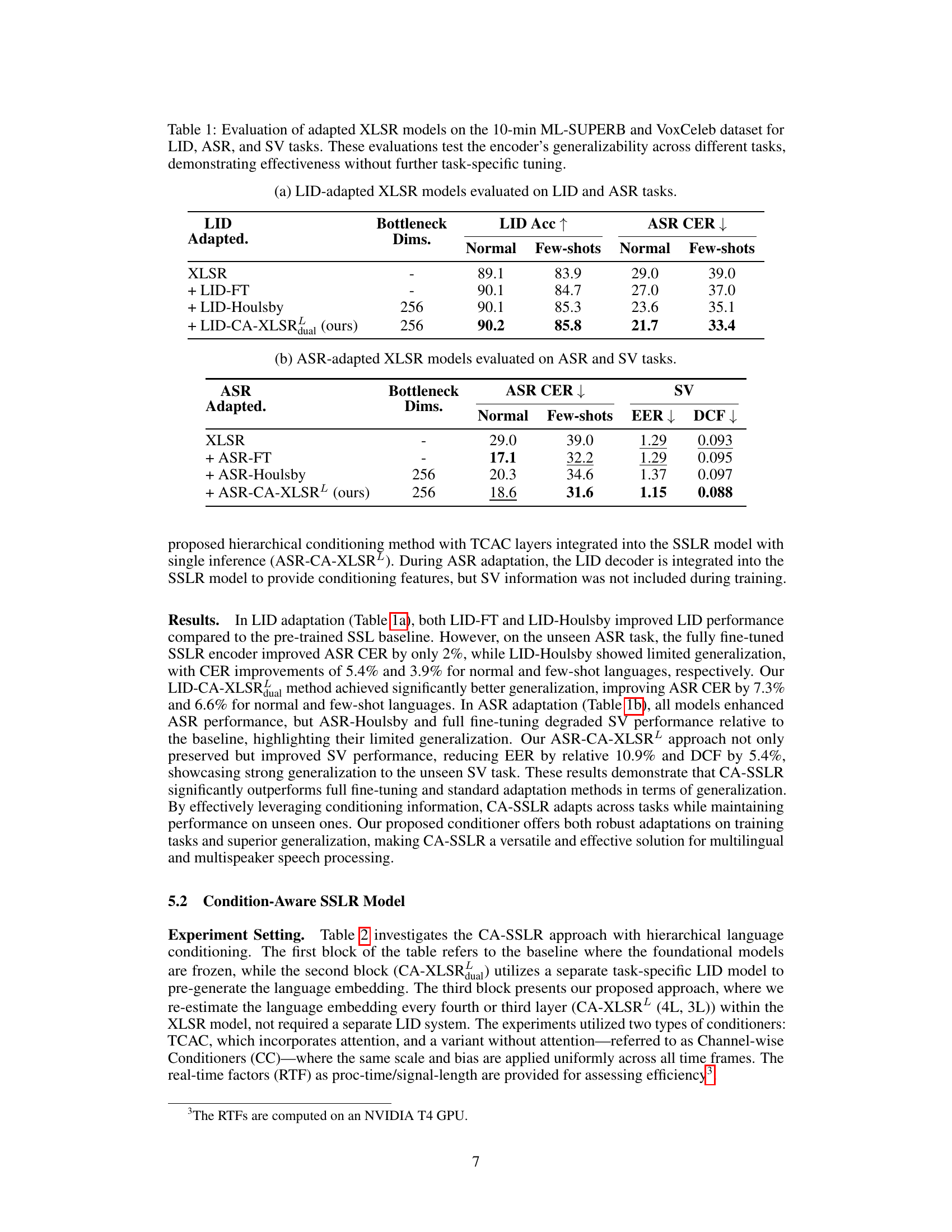

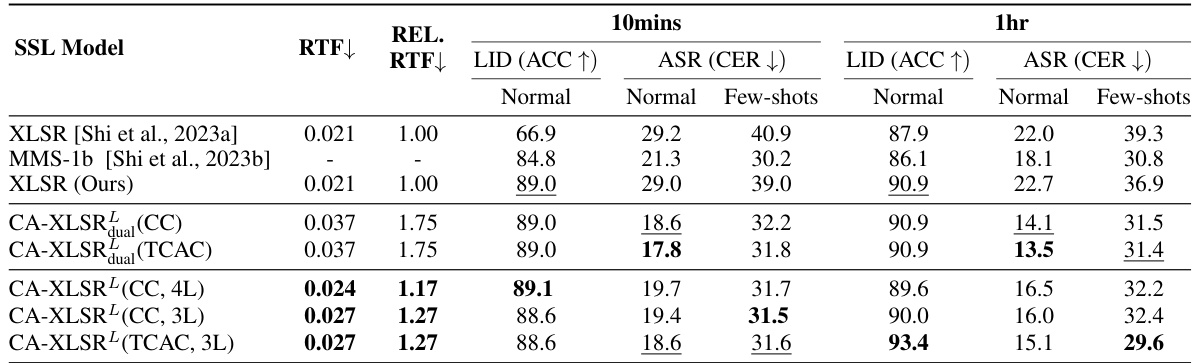

This table presents the results of experiments comparing different configurations of the CA-SSLR model on the ML-SUPERB benchmark. Specifically, it shows the impact of varying the number of layers used to generate the language embedding that is used to condition subsequent layers. The experiment uses the XLSR model adapted for LID and ASR tasks. The table reports the Real-Time Factor (RTF), the relative improvement in RTF, LID accuracy (ACC), and ASR Character Error Rate (CER) for both 10-minute and 1-hour configurations of the dataset, broken down further by ‘Normal’ and ‘Few-shots’ language subsets. This table demonstrates the effectiveness of using hierarchical conditioning to improve both LID and ASR performance.

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the generalization ability of adapted XLSR models on three different speech processing tasks: Language Identification (LID), Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), and Speaker Verification (SV). The models were adapted for a single task (either LID or ASR) and then evaluated on both the task they were adapted for and an unseen task. This setup helps assess the model’s ability to generalize to new tasks without needing additional task-specific training. The table shows the performance metrics (accuracy, character error rate, equal error rate, and detection cost function) for both normal and few-shot conditions of the datasets.

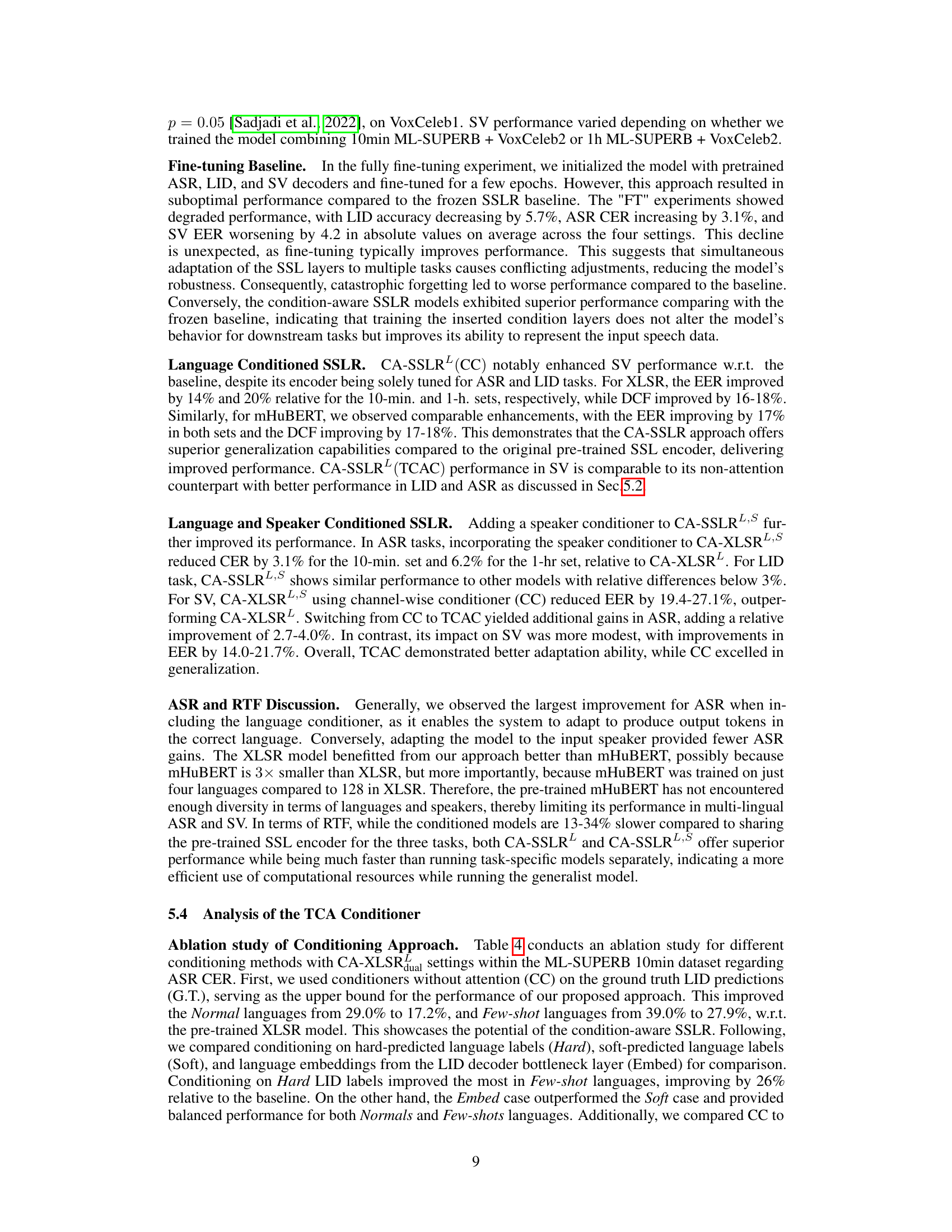

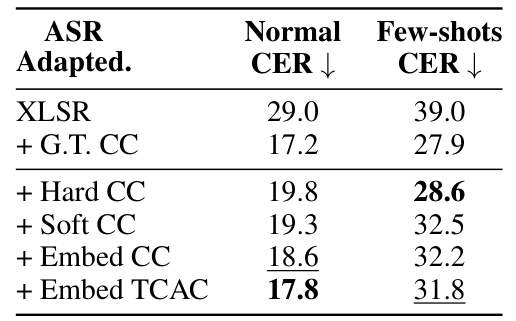

This table presents the results of an ablation study that investigates the impact of different condition-aware settings on the performance of ASR-adapted XLSR models. The study uses the 10-minute ML-SUPERB dataset and compares the performance of models using different conditioning methods (G.T. CC, Hard CC, Soft CC, Embed CC, and Embed TCAC). The results are reported in terms of Character Error Rate (CER) for both normal and few-shot languages.

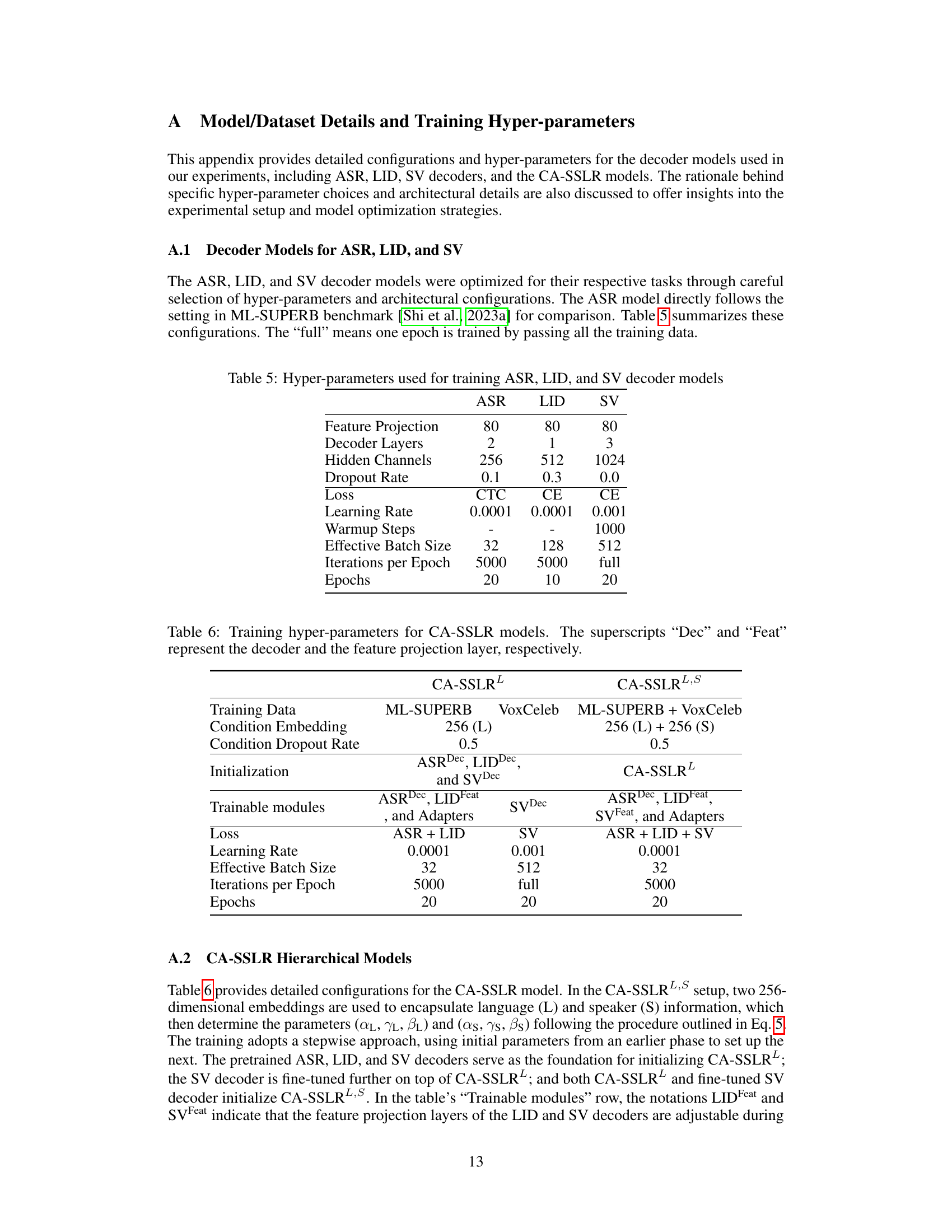

This table details the hyperparameters used for training the decoder models for Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), Language Identification (LID), and Speaker Verification (SV). It specifies parameters such as feature projection dimensions, the number of decoder layers, hidden channel counts, dropout rates, loss functions, learning rates, warmup steps, effective batch sizes, iterations per epoch, and the total number of epochs for each task. These settings are crucial for optimizing the performance of each decoder model.

This table details the hyperparameters used for training the CA-SSLR models. It shows the training data used (ML-SUPERB and/or VoxCeleb), the dimensionality of the language and speaker condition embeddings, the dropout rate for these embeddings, the initialization method for the model components (ASR, LID, and SV decoders), the trainable model parts (decoders, feature projection layers, and adapters), the loss functions used, the learning rate, batch size, number of iterations per epoch, and the number of epochs trained.

This table shows the data configuration for the original and extended few-shot conditions used in the ML-SUPERB benchmark. It specifies the amount of data per language (10 minutes or 1 hour) for normal languages, and for the original few-shot languages, the LID training data was not presented in the result while ASR only used 5 utterances. For the extended few-shot languages, LID training utilized 10 minutes or 1 hour of data (with language labels only) and ASR training still used 5 utterances.

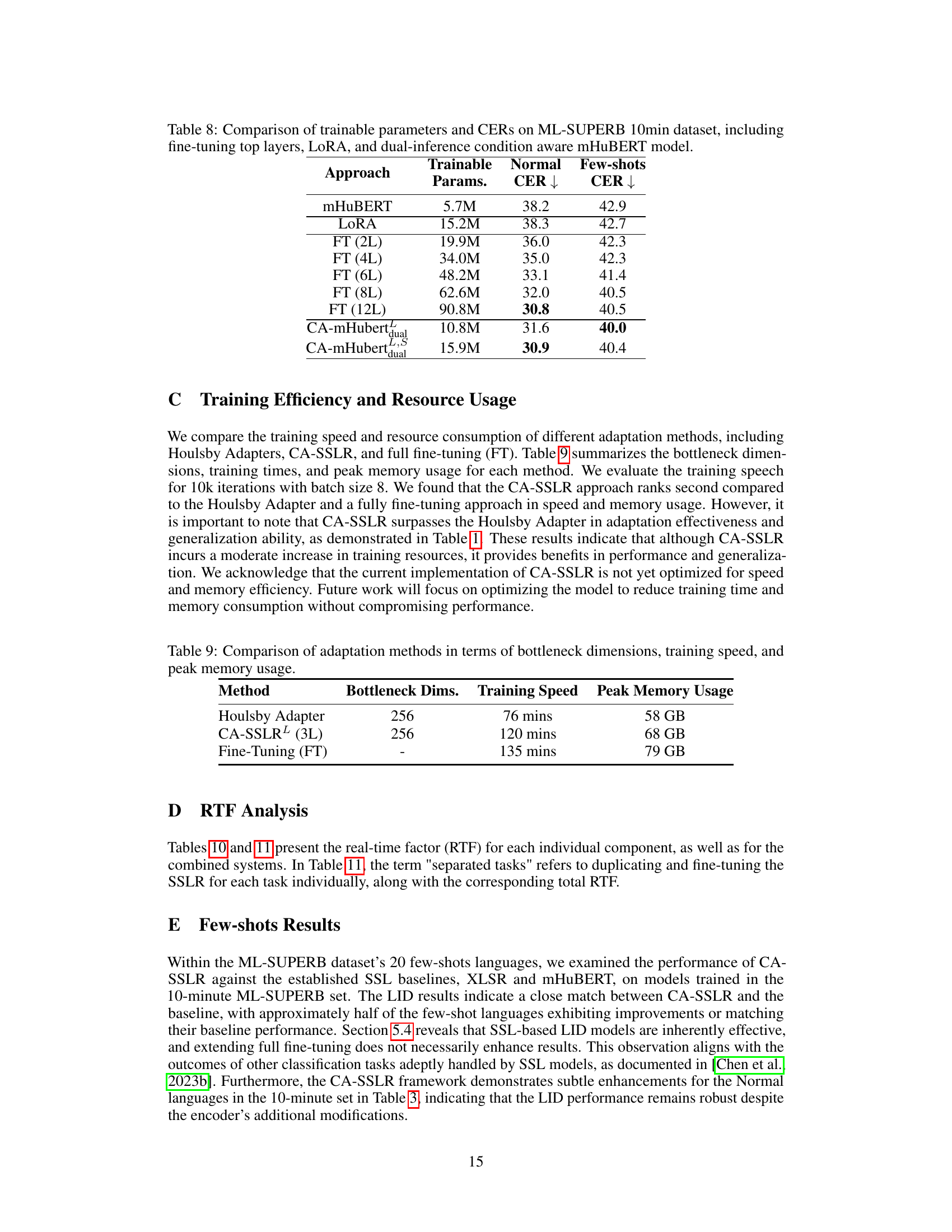

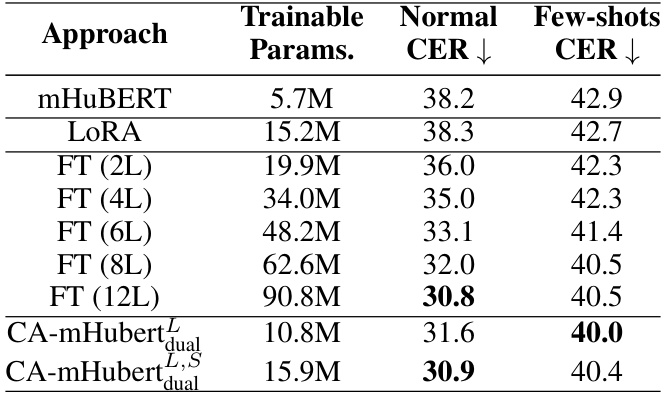

This table compares different model adaptation techniques on the ML-SUPERB 10-minute dataset, focusing on the trade-off between the number of trainable parameters and the resulting Character Error Rate (CER) for both normal and few-shot language scenarios. The approaches compared include fine-tuning various numbers of layers (FT (2L) to FT (12L)), the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique, and two versions of the proposed Condition-Aware mHuBERT model (CA-mHubertdual and CA-mHubertdualLS). The table demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed method in achieving lower CER with fewer parameters, especially in the few-shot setting.

This table compares three different model adaptation methods: Houlsby Adapter, CA-SSLR, and Fine-tuning. For each method, it shows the bottleneck dimensions used, the training time required (in minutes), and the peak GPU memory usage (in GB). The results highlight the relative efficiency and resource requirements of each method.

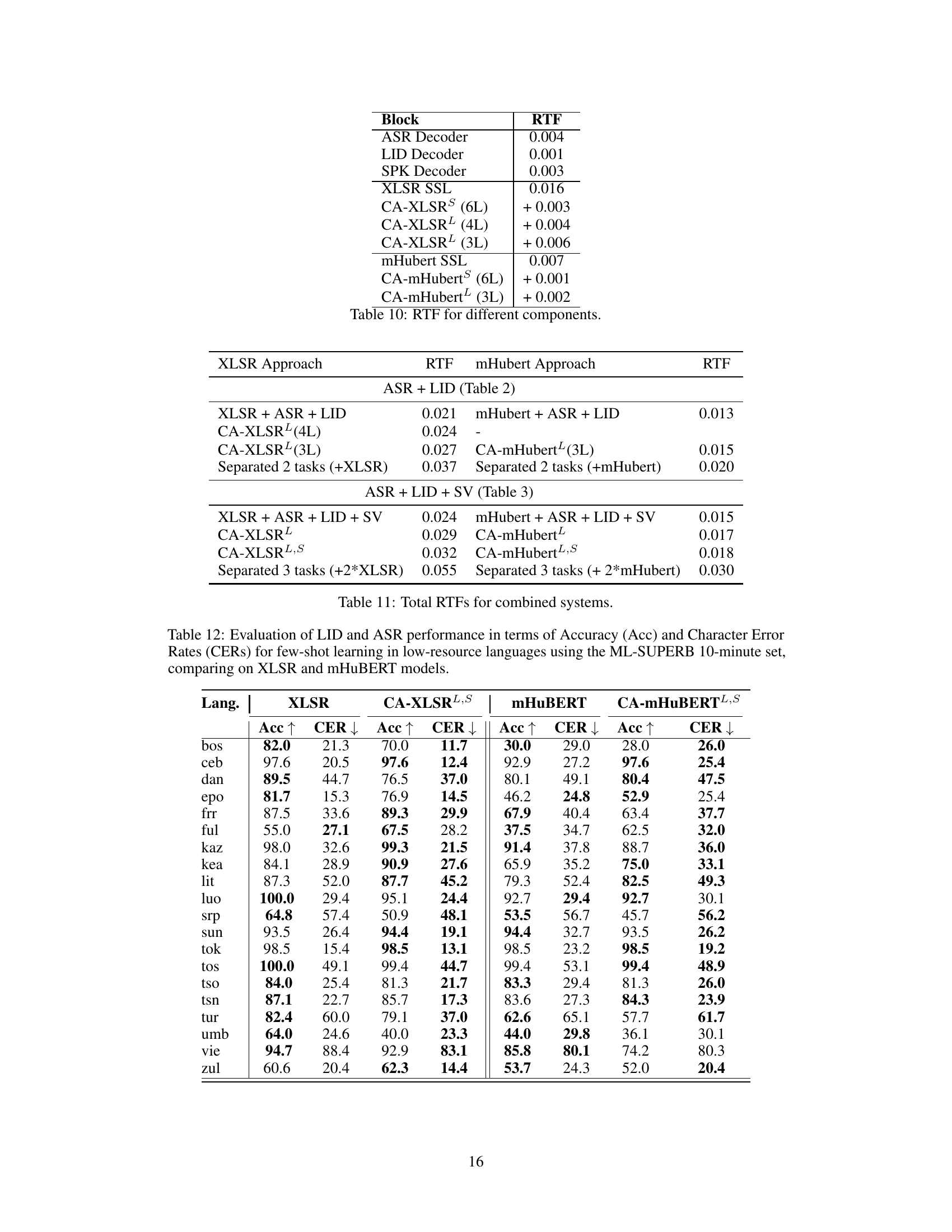

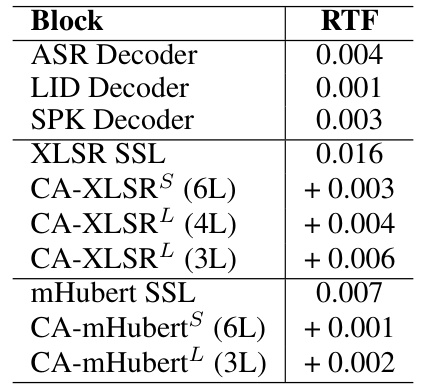

This table shows the real-time factor (RTF) for individual components of the proposed CA-SSLR model, as well as for the XLSR and mHubert SSL models, with and without conditioning. It helps in understanding the computational overhead introduced by each component of the model, comparing different conditioning strategies and different base models.

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the generalization ability of adapted XLSR models on three different speech processing tasks: Language Identification (LID), Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), and Speaker Verification (SV). The models were adapted for either LID or ASR and then evaluated on both the adapted task and an unseen task. The table shows the performance (accuracy or error rate) on both the normal and few-shot datasets for each task and adaptation method. This demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize to unseen tasks with minimal additional training.

This table presents the results of evaluating adapted XLSR models on three different speech processing tasks: Language Identification (LID), Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), and Speaker Verification (SV). The models were adapted for a single task (either LID or ASR) and then evaluated on both the adapted task and an unseen task to assess their generalization abilities. The table shows the performance (accuracy or error rate) for each task and model variant, highlighting the effectiveness of the adaptation methods without needing further task-specific fine-tuning.

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the generalization ability of adapted XLSR models across three different speech processing tasks: Language Identification (LID), Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), and Speaker Verification (SV). The models were adapted for a single task (either LID or ASR) and then evaluated on both the adapted task and an unseen task. The table shows the performance (LID accuracy, ASR Character Error Rate (CER), and SV Equal Error Rate (EER)) for different adaptation methods, including full fine-tuning, Houlsby adapters, and the proposed CA-SSLR approach. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the CA-SSLR approach in improving generalization performance across different tasks compared to traditional adaptation methods.

Full paper#