TL;DR#

Open-vocabulary semantic segmentation models struggle to generalize across different camera viewpoints (e.g., car vs. drone). Existing domain adaptation methods fail to effectively model cross-view geometric changes. This limits their ability to transfer knowledge between views effectively.

This paper introduces EAGLE, a novel unsupervised cross-view adaptation method. EAGLE addresses this by introducing a novel cross-view geometric constraint, a geodesic flow-based correlation metric, and a view-condition prompting mechanism. Experiments show EAGLE achieves state-of-the-art results on multiple benchmarks, demonstrating its effectiveness in cross-view modeling and surpassing previous methods in open-vocabulary semantic segmentation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on semantic segmentation, domain adaptation, and open-vocabulary scene understanding. It provides a novel approach to cross-view adaptation, a challenging problem with significant real-world applications. The proposed method, EAGLE, achieves state-of-the-art results, opening new avenues for improving the generalization and robustness of computer vision models in diverse settings.

Visual Insights#

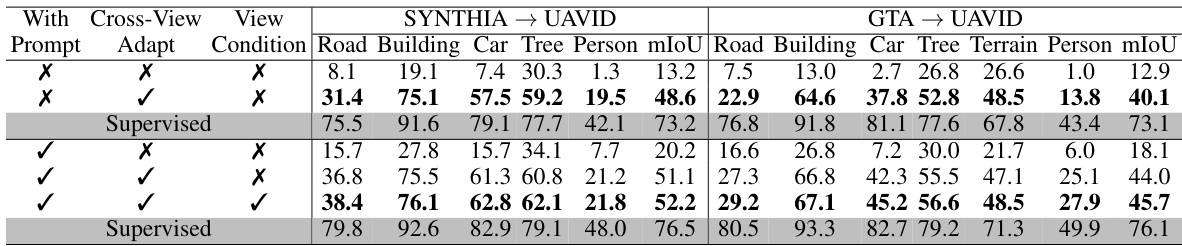

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper, which is to improve the generalization of open-vocabulary semantic segmentation models across different camera views (car view vs. drone view). It shows that existing models trained on one view perform poorly when tested on the other view. The paper’s proposed approach, EAGLE, is shown to successfully adapt between the two views.

read the caption

Figure 1: Our Proposed Cross-view Adaptation Learning Approach. Prior models, e.g., FreeSeg [38], DenseCLIP [40], trained on the car view do not perform well on the drone-view images. Meanwhile, our cross-view adaptation approach is able to generalize well from the car to drone view.

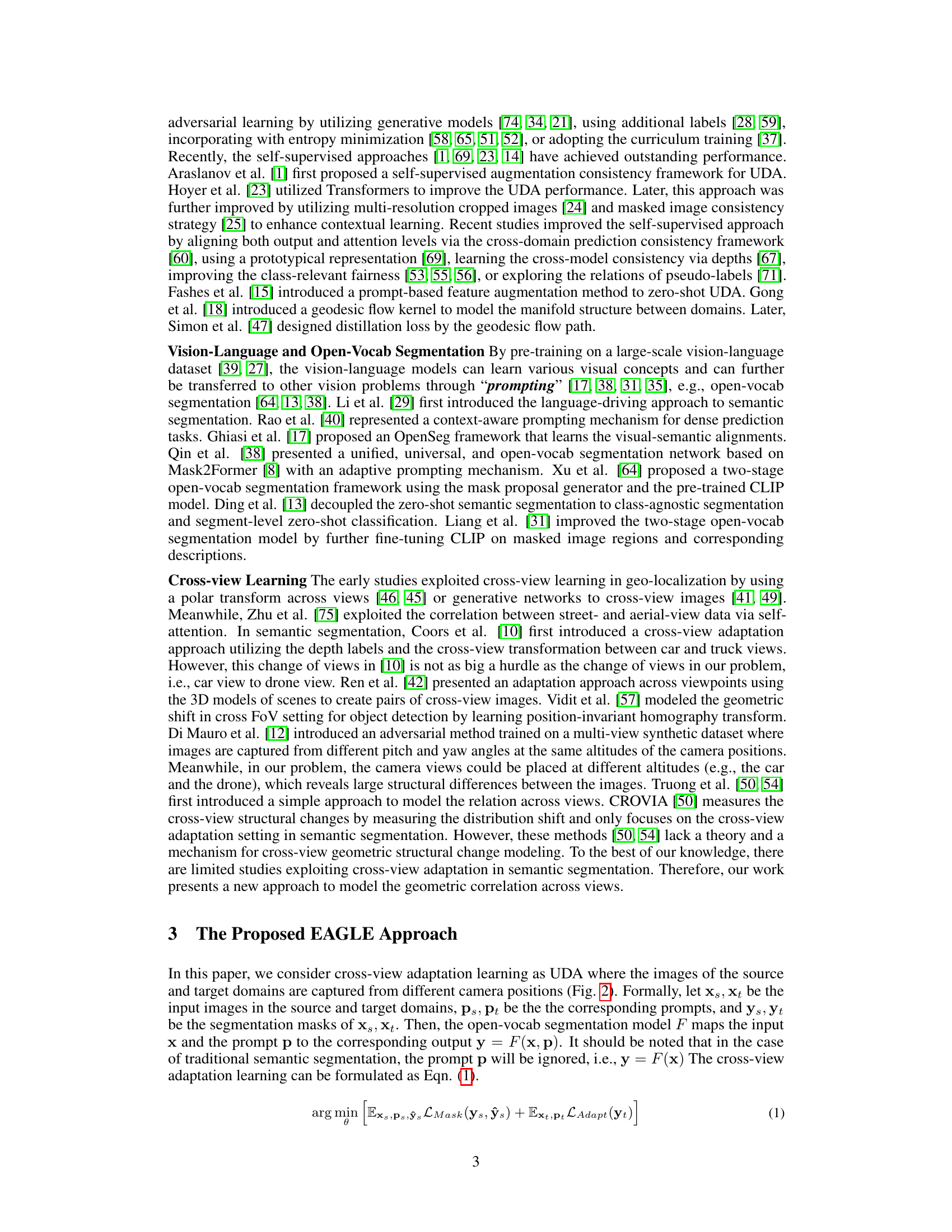

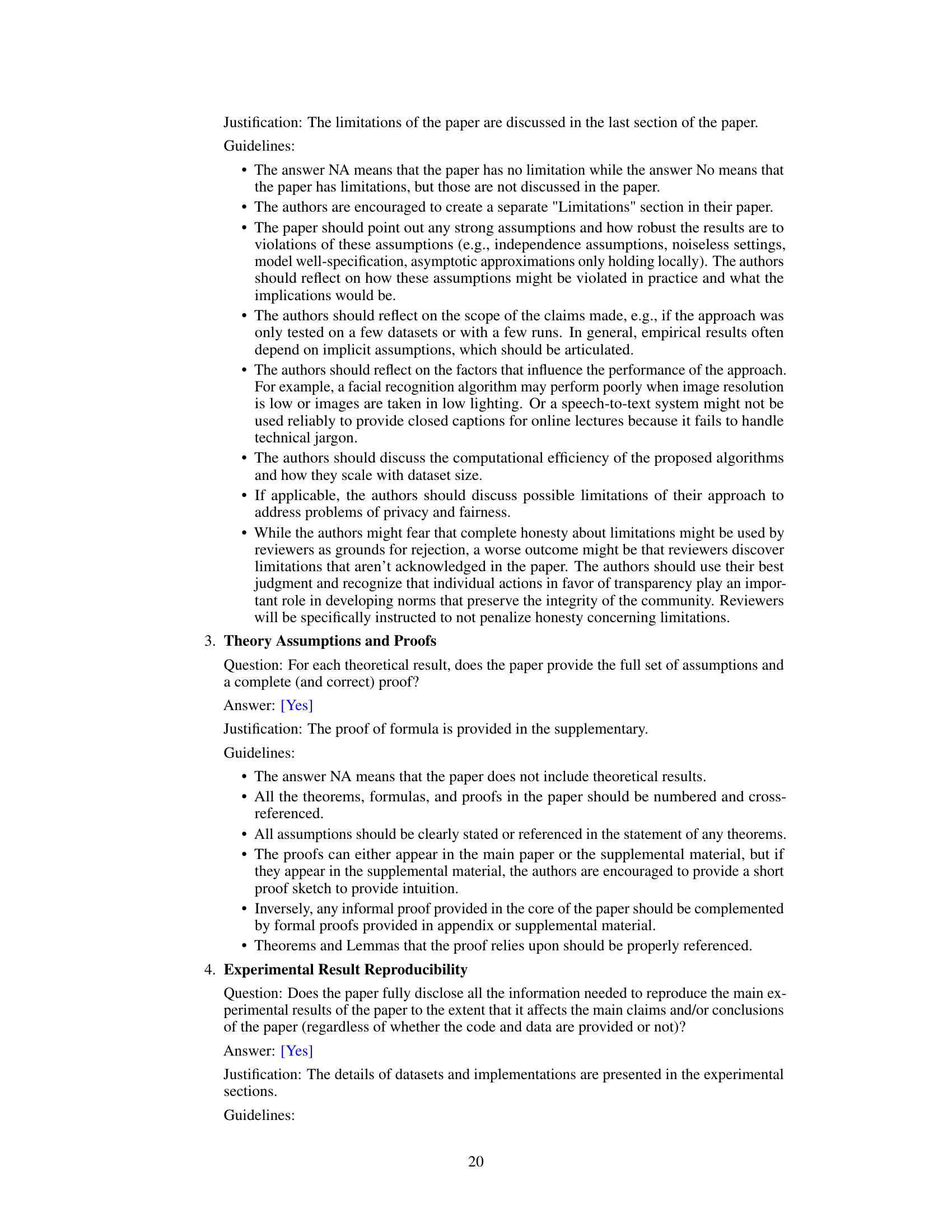

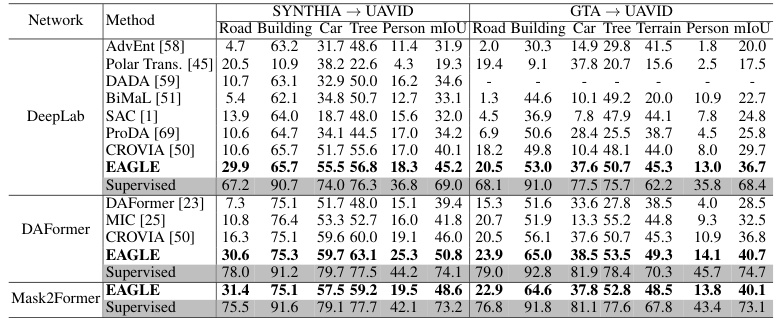

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study evaluating the impact of different components of the proposed EAGLE approach on the cross-view adaptation task. Specifically, it shows how the performance (mIoU) varies across different combinations of cross-view adaptation loss, view condition prompting, and the use of a supervised training setting. Results are reported for two benchmarks: SYNTHIA → UAVID and GTA → UAVID, and for individual semantic classes: Road, Building, Car, Tree, Person. The table allows for a comparison of the effectiveness of the proposed method under various conditions.

read the caption

Table 1: Effectiveness of Our Cross-view Adaptation Losses and Prompting Mechanism.

In-depth insights#

Cross-view Adaptation#

Cross-view adaptation in computer vision focuses on bridging the performance gap between models trained on one camera view and their generalization to another. This is crucial because data from a specific view (e.g., car-mounted camera) is abundant, while annotation for other views (e.g., aerial) is expensive. The core challenge is modeling the geometric and structural differences between views. Effective approaches must account for changes in image appearance, object positions, and scene layout caused by viewpoint shifts. This often involves techniques such as geometric transformations, metric learning to handle variations in appearance, and potentially techniques that incorporate 3D scene understanding. Unsupervised domain adaptation is a common strategy for learning these cross-view relationships without requiring paired data from both views, which is often unavailable. A promising area is the integration of vision-language models, which can leverage semantic information to improve the robustness and accuracy of cross-view adaptation. Finally, prompt engineering techniques such as view-condition prompting offer a mechanism to directly guide the model to reason about the camera viewpoint during adaptation, further boosting performance.

Geometric Modeling#

Geometric modeling in computer vision and graphics aims to create and manipulate mathematical representations of shapes and objects. In the context of cross-view understanding, geometric modeling is crucial for bridging the gap between different viewpoints. This involves understanding and representing how objects appear differently depending on camera position and orientation. Effective geometric models can capture transformations, such as rotations and translations, which enable consistent object recognition across views. Challenges include handling variations in lighting, occlusion, and scale, making robust and accurate geometric modeling a complex task. Moreover, efficient algorithms are needed to process and compare geometric data from various viewpoints, particularly for real-time applications. The choice of representation (e.g., meshes, point clouds, implicit surfaces) influences the complexity and effectiveness of the geometric modeling approach. Advancements in geometric modeling are essential for developing more robust and versatile cross-view understanding systems. This is particularly relevant for applications requiring accurate 3D scene understanding, such as autonomous navigation, robotics, and augmented reality.

Prompt Engineering#

Prompt engineering, in the context of large language models (LLMs) and vision-language models, is the process of carefully crafting prompts to elicit desired outputs. Effective prompt engineering is crucial for leveraging LLMs’ full potential, as poorly designed prompts can lead to irrelevant, nonsensical, or biased results. Different prompting strategies exist, such as zero-shot, few-shot, and chain-of-thought prompting, each suited for various tasks and levels of available labeled data. The choice of prompt greatly influences the model’s reasoning process and the quality of the generated response. Understanding the model’s limitations and biases is crucial for effective prompt design. For example, the paper might discuss incorporating context-aware prompting or adaptive prompting techniques to address the challenges of cross-view adaptation in semantic segmentation models. Careful consideration of prompt wording, structure, and context can significantly improve performance, especially when dealing with nuanced tasks or complex datasets. Ultimately, mastering prompt engineering is a key skill for unlocking the transformative capabilities of LLMs and V-LLMs in real-world applications.

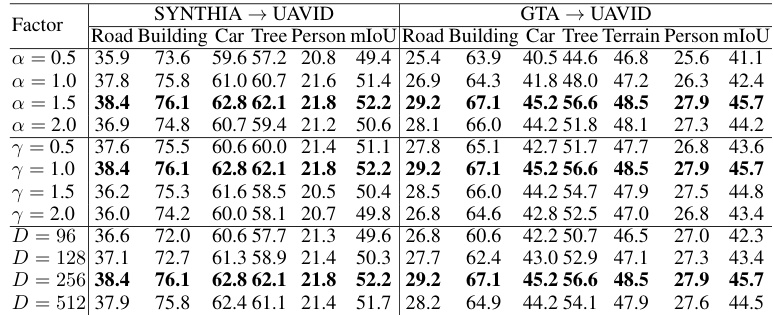

Ablation Experiments#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, an ‘Ablation Experiments’ section would detail these experiments. The goal is to isolate the impact of specific design choices, such as a particular loss function, architectural element, or data augmentation technique. By comparing the performance of the full model against versions with components removed, researchers can determine the relative importance of each part. A well-designed ablation study enhances the credibility and understanding of the model by providing evidence for the necessity of its various aspects. The results often guide future work by pinpointing areas for potential improvements or highlighting unexpectedly detrimental design choices. Clear presentation of ablation results involves comparing key metrics across different model variants, allowing readers to fully understand the contribution of each component. The discussion should not only focus on quantitative results but also offer qualitative insights into why specific design choices are beneficial or detrimental.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this cross-view adaptation work could explore several promising avenues. Improving robustness to diverse weather conditions and varying lighting scenarios is crucial for real-world applicability. The current model’s reliance on pre-trained vision-language models suggests investigating the impact of using alternative or more specialized language models. Further research could focus on extending the approach to handle more complex scenarios, such as those involving significant occlusions or dynamic objects. Developing more efficient and scalable methods for measuring cross-view geometric correlations, potentially through novel geometric deep learning techniques, warrants further exploration. Finally, a deeper investigation into the theoretical underpinnings and limitations of the proposed method is vital to guide future improvements and ensure broader applicability. Specifically, a thorough analysis of the assumptions made and their impact on performance, particularly in diverse and challenging real-world datasets, would be highly valuable.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows an example of cross-view adaptation from a car view to a drone view. The input image from the car view is shown, along with its ground truth segmentation and the model’s prediction. Then, an arrow indicates the cross-view adaptation process. After that, the input image from the drone view and the model’s prediction on this image are presented. This illustrates the challenge of adapting a model trained on one viewpoint to another, which is addressed by the proposed method in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 2: An Example of Illustration of Cross-View Adaptation From Car View to Drone View.

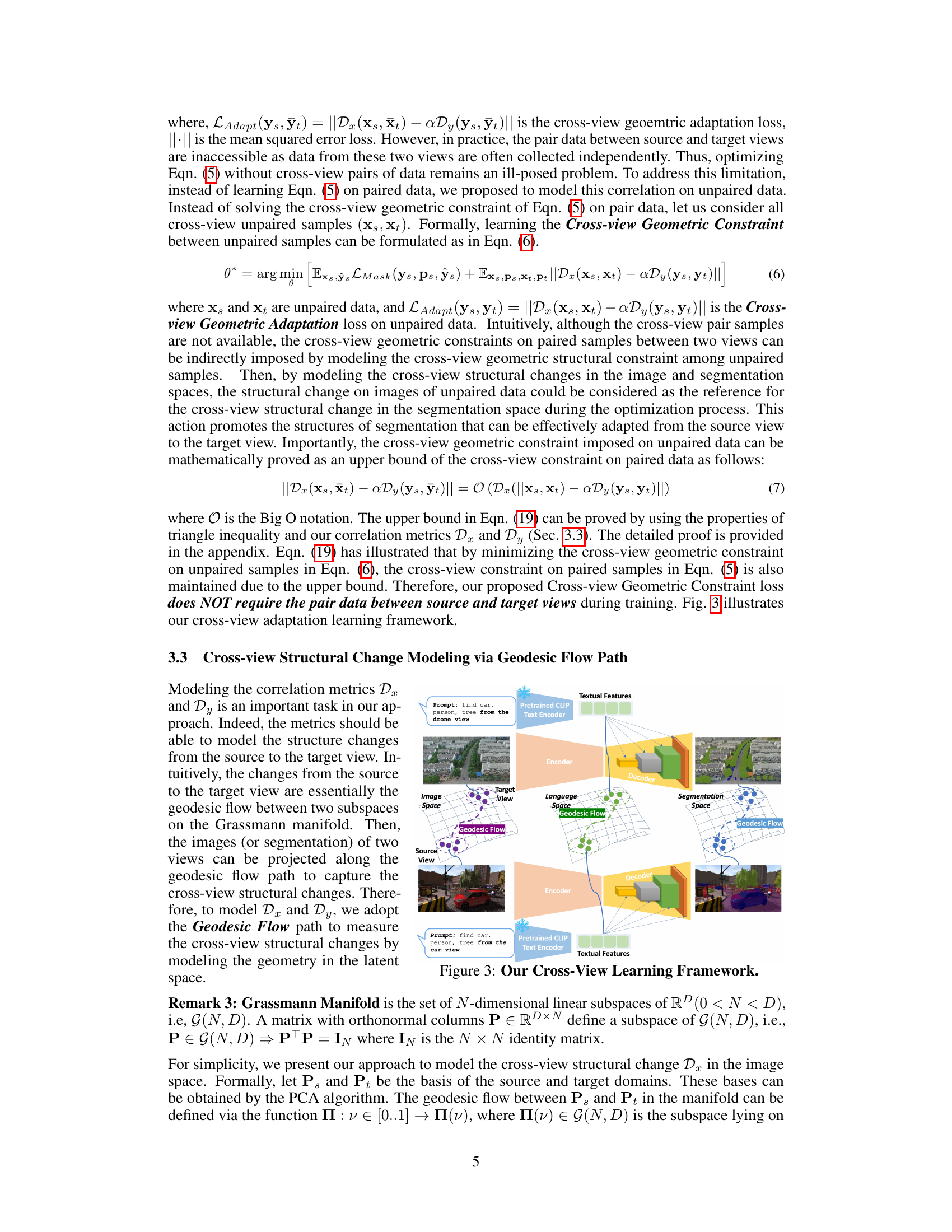

🔼 This figure illustrates the EAGLE approach’s framework for cross-view adaptation learning. It shows how the model utilizes pretrained CLIP text encoders to generate textual features from prompts specifying objects to find (‘car, person, tree’) from both car and drone views. These features, along with image data from both views, are fed into separate encoders and decoders. A key element is the use of geodesic flow to model the geometric structural changes between the two views in both image and segmentation spaces. This allows the model to effectively adapt from the source (car) view to the target (drone) view, addressing the challenge of cross-view adaptation in semantic scene understanding.

read the caption

Figure 3: Our Cross-View Learning Framework.

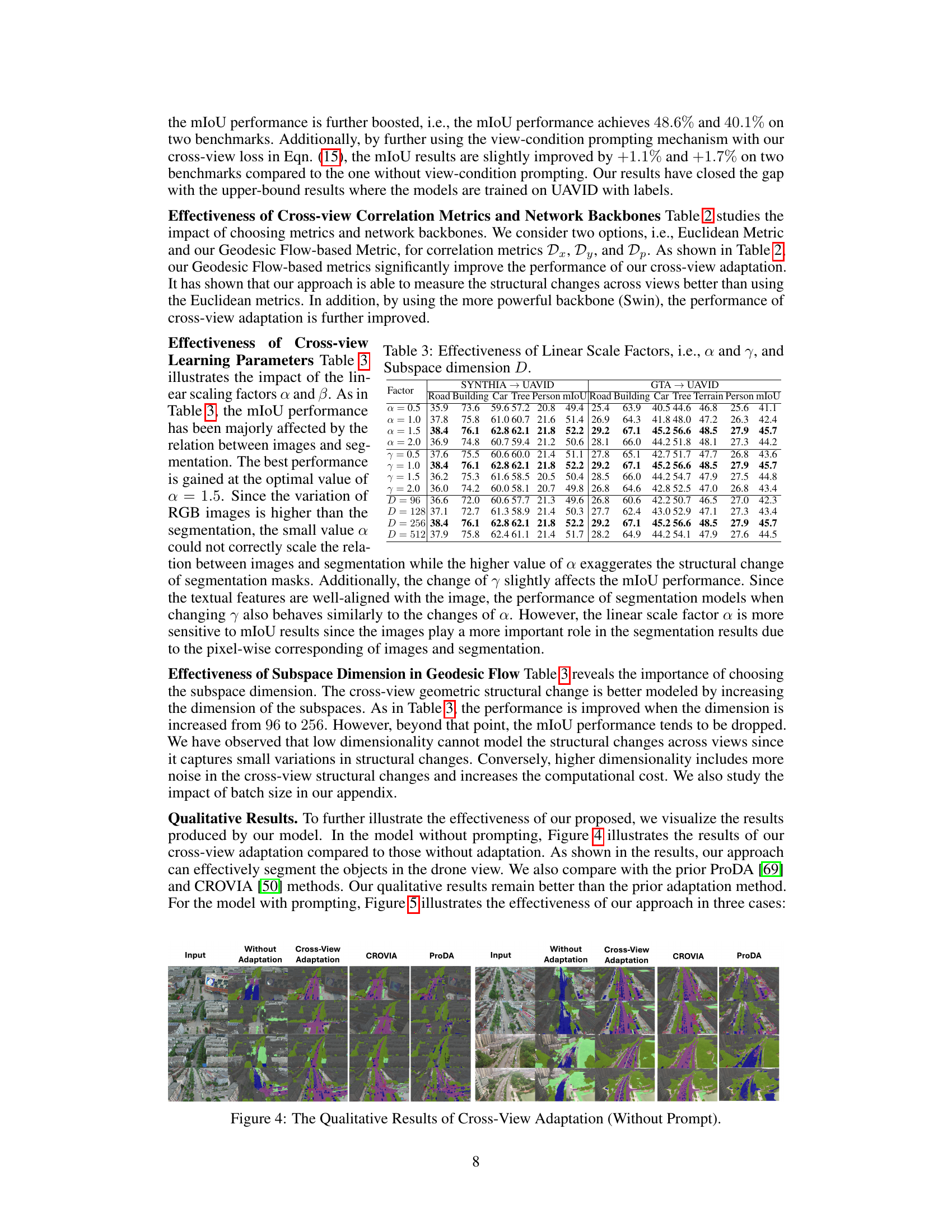

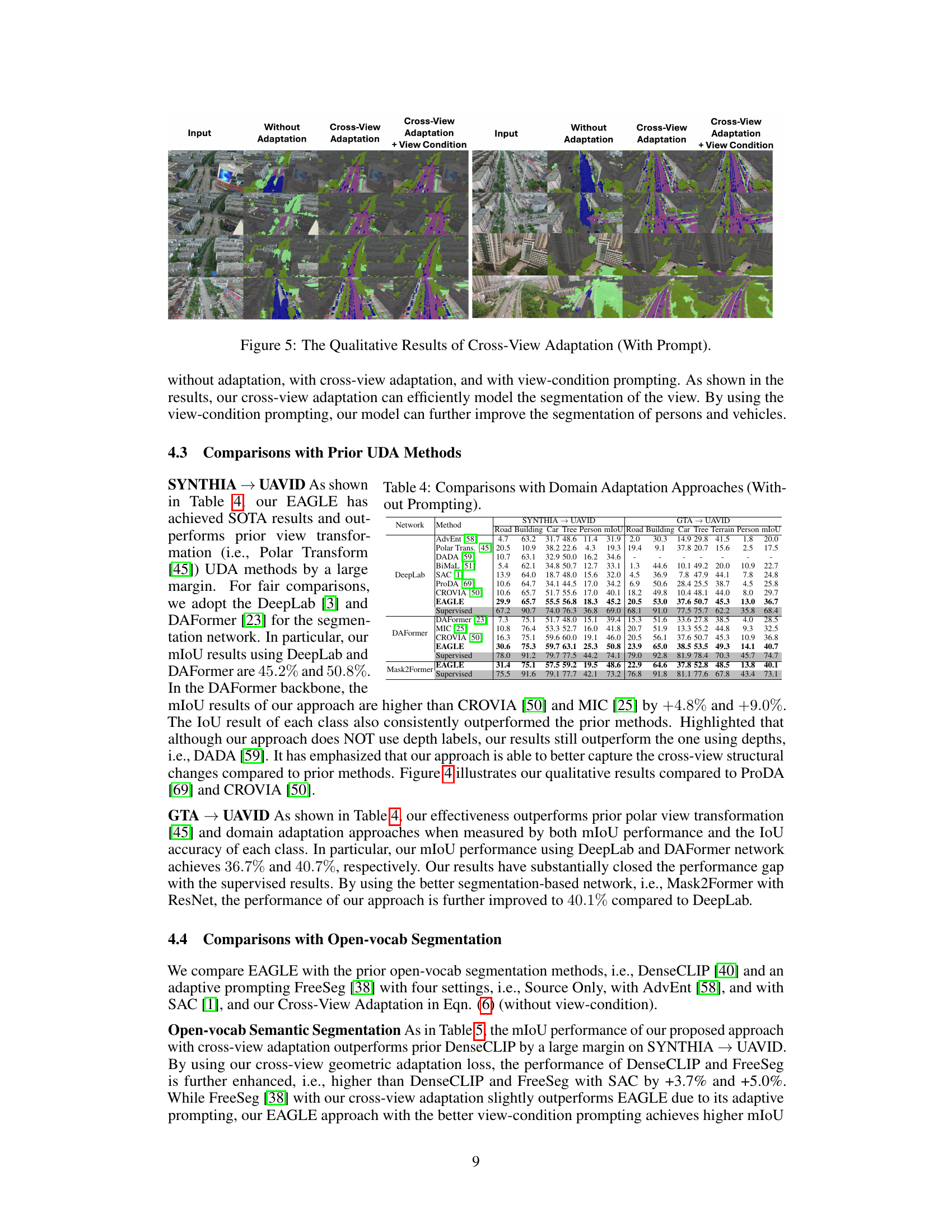

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of qualitative results for cross-view adaptation with and without the proposed method on the UAVID dataset. The left-hand side shows images from the source domain (car view) and the corresponding segmentation results using four methods: input image, results without cross-view adaptation, results with the proposed cross-view adaptation, results from CROVIA, and results from ProDA. The right-hand side shows the same comparison for images from the target domain (drone view). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in improving the quality of cross-view semantic segmentation.

read the caption

Figure 4: The Qualitative Results of Cross-View Adaptation (Without Prompt).

🔼 This figure shows the qualitative results of cross-view adaptation without prompting. It compares the results of applying the proposed cross-view adaptation method to the input images with the results of not using cross-view adaptation. The results are displayed in pairs: the left image shows the input, the middle shows the segmentation result without cross-view adaptation, and the right shows the results with cross-view adaptation. This visual comparison demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed method in improving the quality of segmentation results.

read the caption

Figure 4: The Qualitative Results of Cross-View Adaptation (Without Prompt).

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of different approaches to cross-view adaptation for semantic segmentation. The top row shows the input images from a car view, the predictions from a model trained only on car view images, and the predictions from the proposed EAGLE model. The bottom row shows the same comparison but for drone view images. The figure highlights that the proposed EAGLE model is able to generalize better to unseen drone view images compared to models trained only on car view images.

read the caption

Figure 1: Our Proposed Cross-view Adaptation Learning Approach. Prior models, e.g., FreeSeg [38], DenseCLIP [40], trained on the car view do not perform well on the drone-view images. Meanwhile, our cross-view adaptation approach is able to generalize well from the car to drone view.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper, which is to adapt a semantic segmentation model trained on images from a car’s perspective to perform well on images taken from a drone. It shows that previous methods (FreeSeg and DenseCLIP) failed to generalize across viewpoints, while the proposed EAGLE method successfully transfers knowledge from the car view to the drone view.

read the caption

Figure 1: Our Proposed Cross-view Adaptation Learning Approach. Prior models, e.g., FreeSeg [38], DenseCLIP [40], trained on the car view do not perform well on the drone-view images. Meanwhile, our cross-view adaptation approach is able to generalize well from the car to drone view.

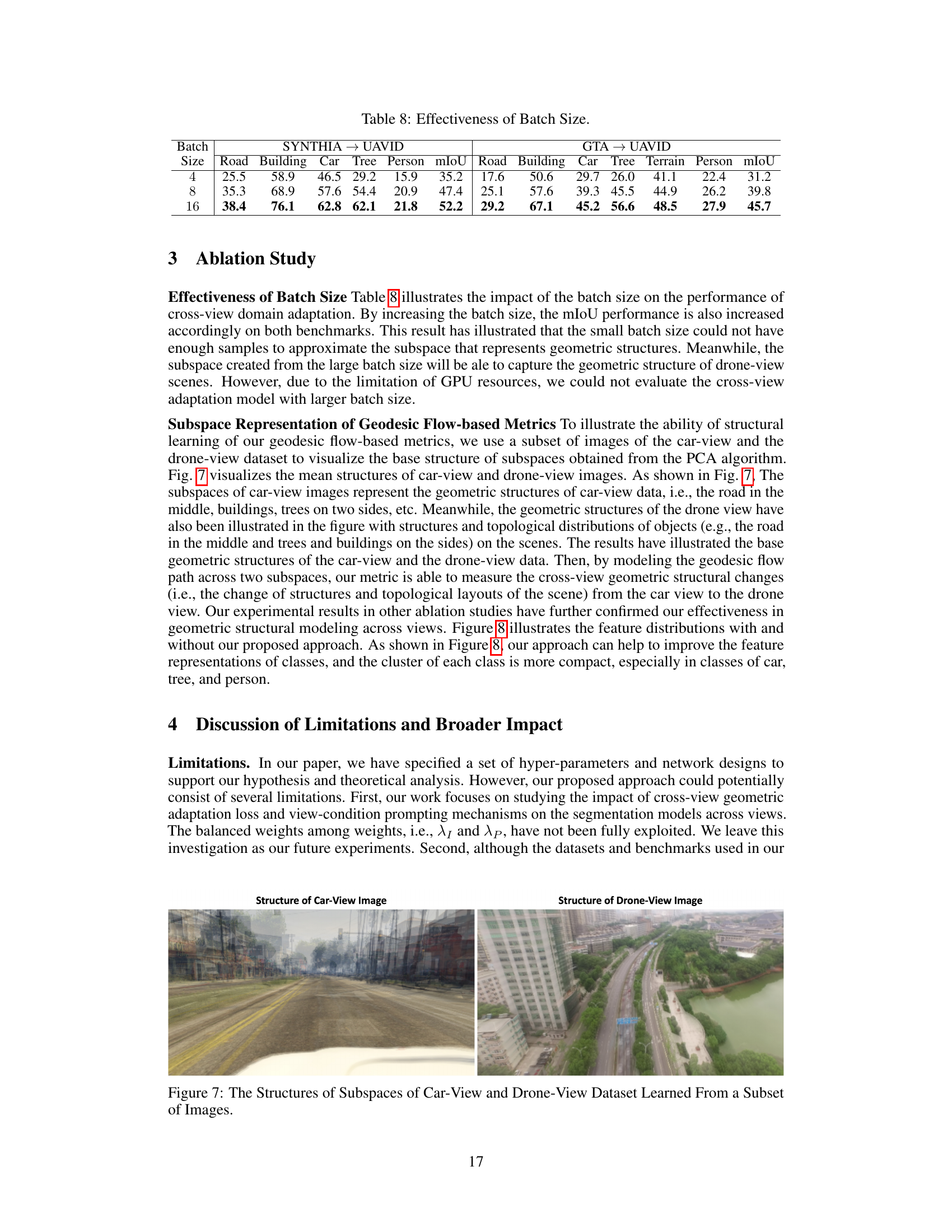

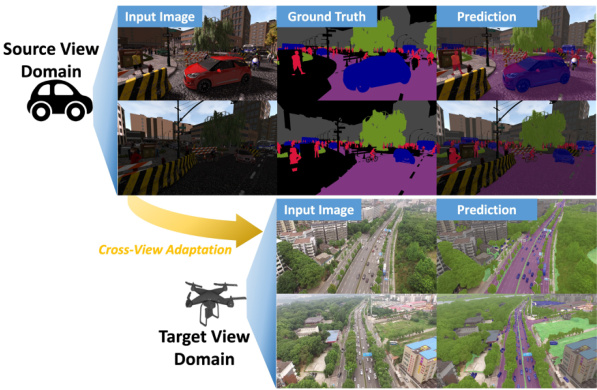

🔼 This figure visualizes the feature distributions of different classes in the SYNTHIA to UAVID experiments, comparing the results with and without cross-view adaptation. It shows the impact of the cross-view adaptation approach on the separation and clustering of features for each class. The visualization helps to understand how well the model is able to distinguish between different semantic categories, before and after applying the proposed method.

read the caption

Figure 8: The Feature Distribution of Classes in SYNTHIA → UAVID Experiments.

More on tables

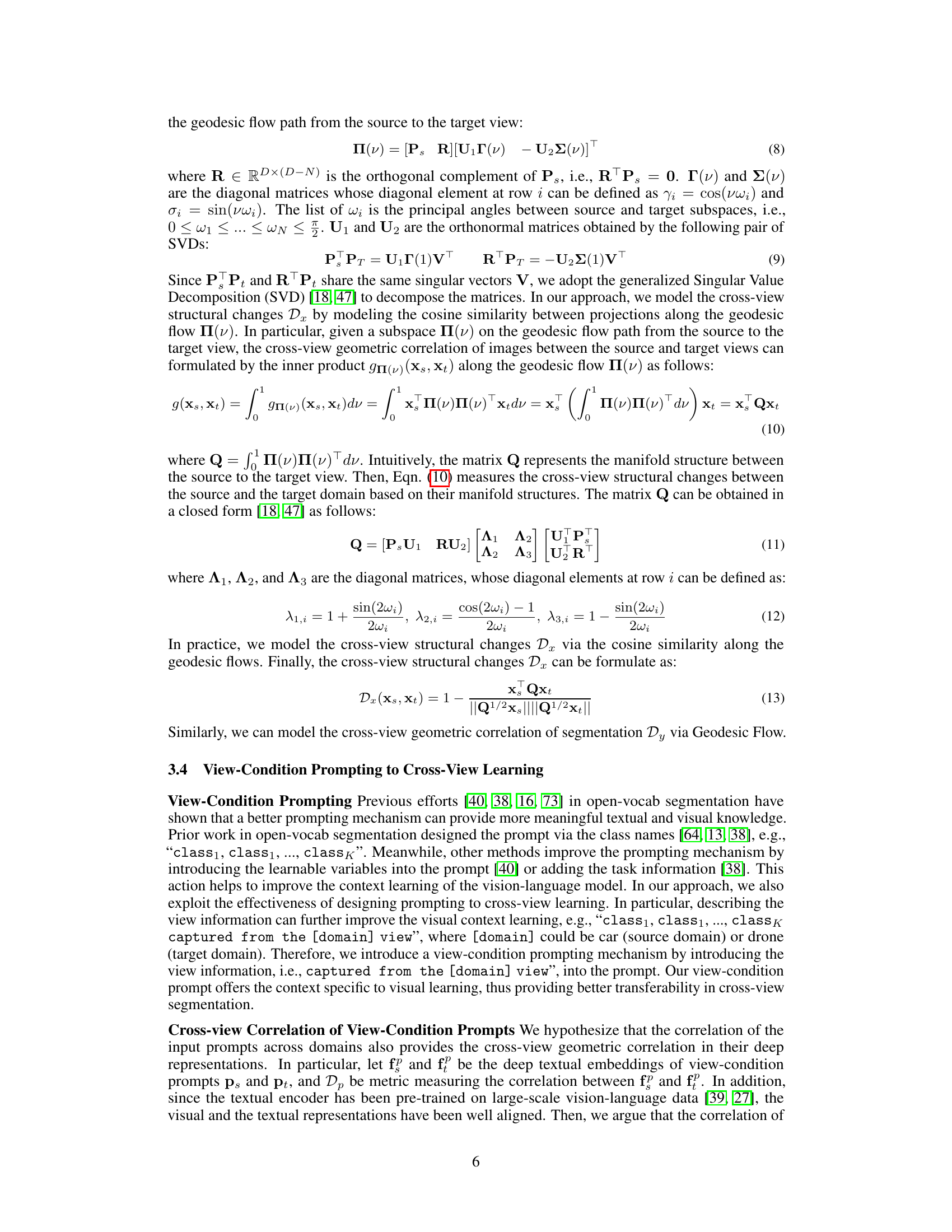

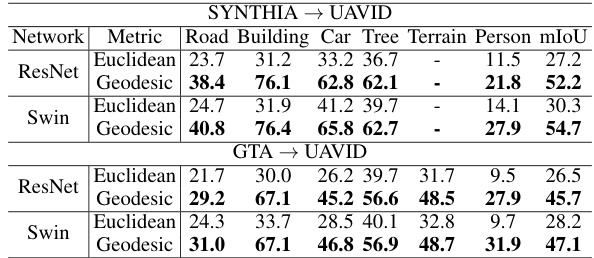

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the choice of backbones (ResNet and Swin) and the cross-view metrics (Euclidean and Geodesic Flow-based). It demonstrates the impact of these choices on the performance of the cross-view adaptation task, measured by mIoU, across different classes (Road, Building, Car, Tree, Terrain, Person) and benchmarks (SYNTHIA → UAVID and GTA → UAVID).

read the caption

Table 2: Effectiveness of Backbones and Cross-view Metrics.

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies evaluating the impact of different components of the proposed EAGLE approach on the cross-view adaptation task using the SYNTHIA→UAVID and GTA→UAVID benchmarks. Specifically, it shows the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) scores for different classes (Road, Building, Car, Tree, Person) with different combinations of cross-view adaptation losses and prompting mechanisms (with/without cross-view adaptation, with/without view condition prompting). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of each component in improving the performance of the model.

read the caption

Table 1: Effectiveness of Our Cross-view Adaptation Losses and Prompting Mechanism.

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study that investigates the impact of different components of the proposed EAGLE approach on the performance of cross-view adaptation. Specifically, it compares the performance of the model with and without different loss functions (cross-view adaptation loss and view-condition prompting loss) and prompting mechanisms (with and without prompting, with and without view-condition prompting). The results are presented in terms of mIoU for various classes (Road, Building, Car, Tree, Person) on two benchmarks (SYNTHIA → UAVID and GTA → UAVID).

read the caption

Table 1: Effectiveness of Our Cross-view Adaptation Losses and Prompting Mechanism.

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of different components of the proposed EAGLE approach. It shows the mIoU scores for various classes (Road, Building, Car, Tree, Person) on two cross-view adaptation benchmarks (SYNTHIA → UAVID and GTA → UAVID). The results are compared across different configurations, including variations in the cross-view adaptation loss, prompting mechanisms (with/without prompting, with/without view condition prompting), and supervised training.

read the caption

Table 1: Effectiveness of Our Cross-view Adaptation Losses and Prompting Mechanism.

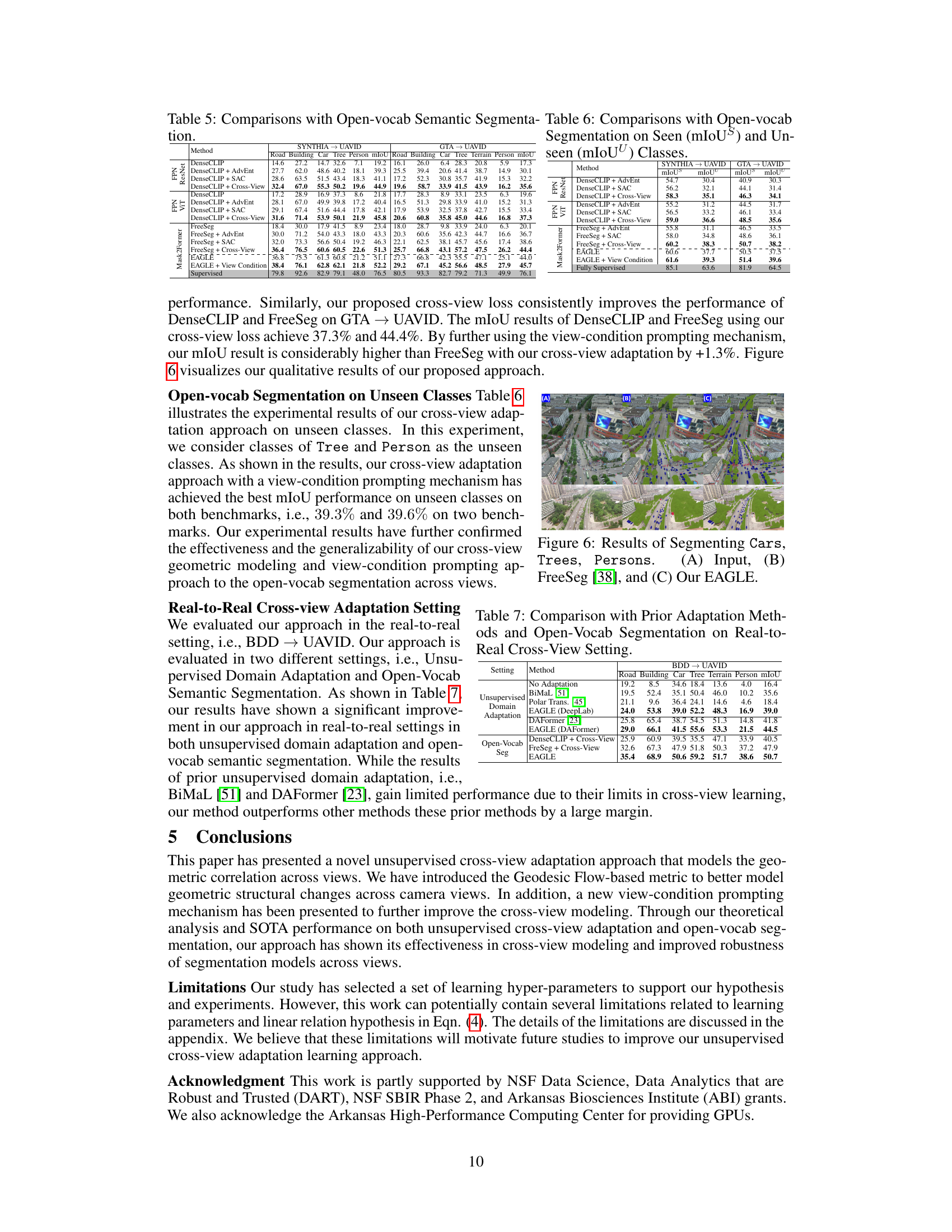

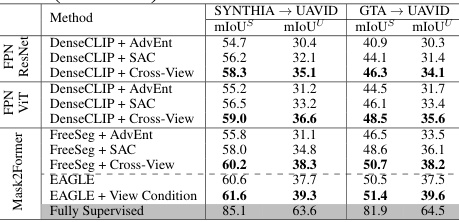

🔼 This table compares the performance of EAGLE with other open-vocabulary semantic segmentation methods, such as DenseCLIP and FreeSeg, on two benchmarks: SYNTHIA → UAVID and GTA → UAVID. The results are broken down by different configurations (Source Only, with AdvEnt, with SAC, and with Cross-View). It shows EAGLE’s superior performance, particularly with the addition of the view-condition prompting mechanism. mIoU (mean Intersection over Union) is used as a metric to measure performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Comparisons with Open-vocab Semantic Segmentation.

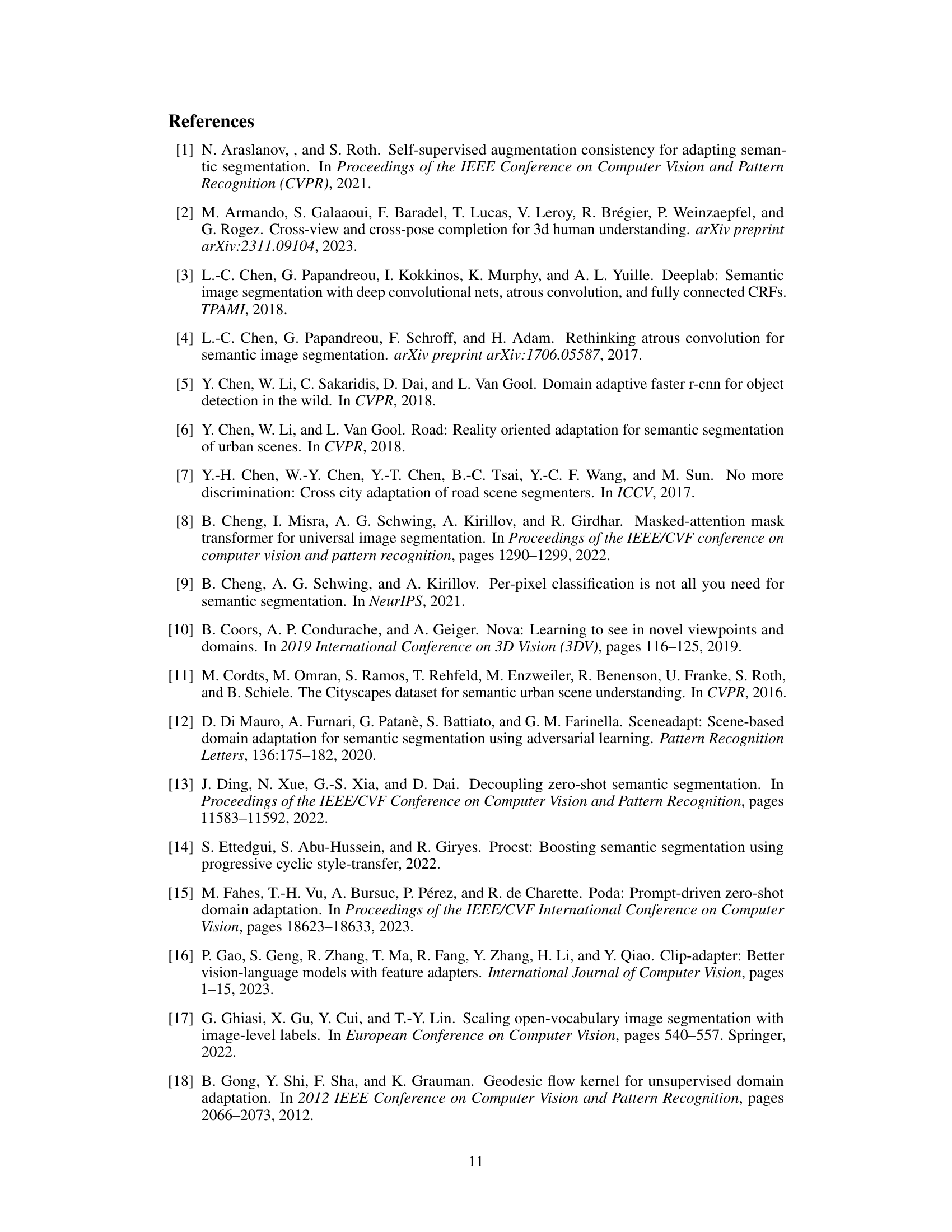

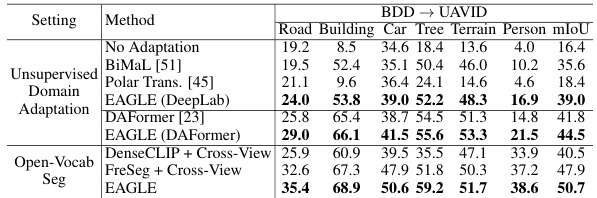

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different methods for semantic segmentation on a real-to-real cross-view adaptation setting (BDD → UAVID). It compares the performance of unsupervised domain adaptation methods (BiMaL, Polar Transforms, EAGLE with DeepLab and DAFormer backbones) and open-vocabulary semantic segmentation methods (DenseCLIP + Cross-View, FreeSeg + Cross-View, and EAGLE). The performance is evaluated using mIoU (mean Intersection over Union) across multiple classes.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison with Prior Adaptation Methods and Open-Vocab Segmentation on Real-to-Real Cross-View Setting.

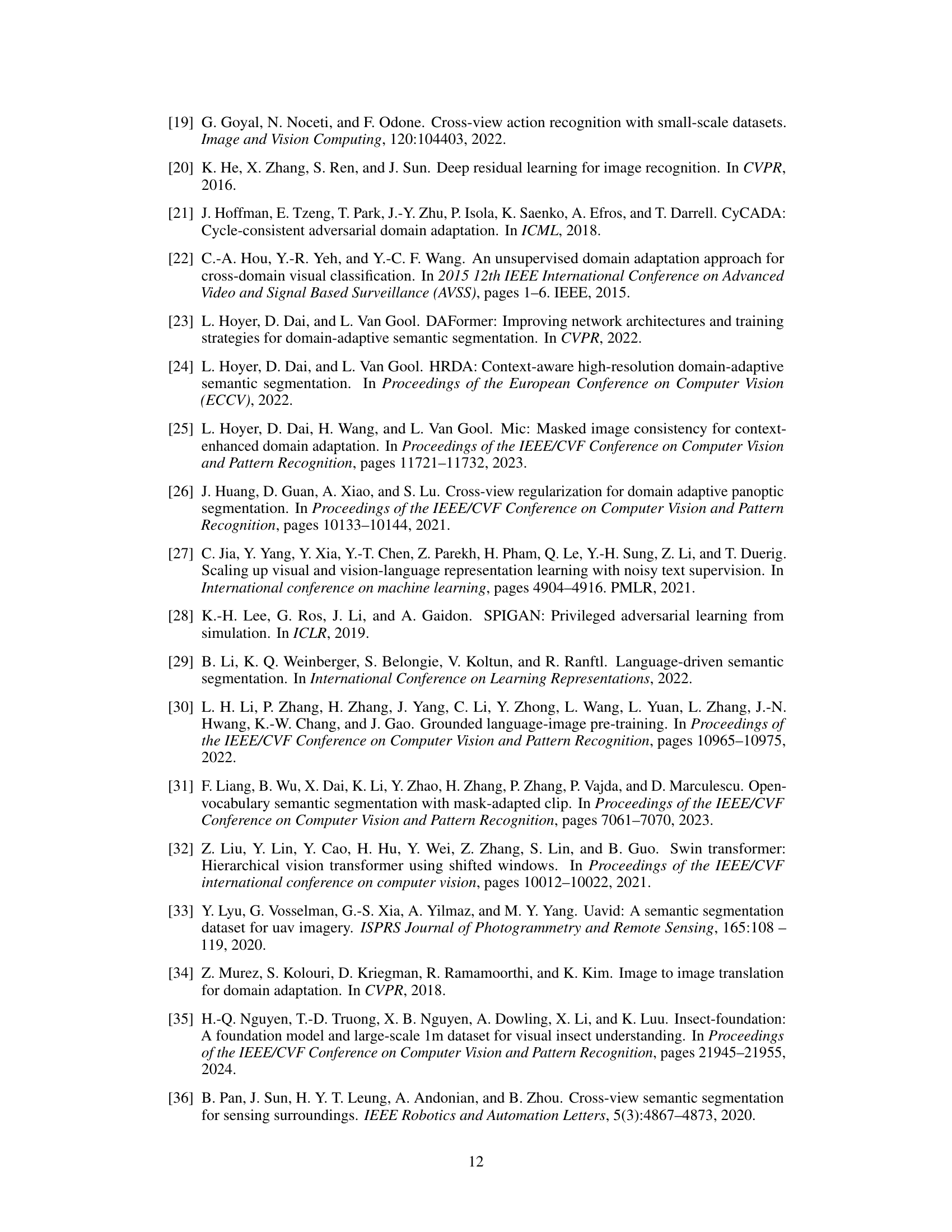

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the effect of batch size on the performance of the cross-view adaptation model. The results are shown for two benchmarks: SYNTHIA → UAVID and GTA → UAVID. For each benchmark, the table shows the mIoU and class-wise IoU scores (Road, Building, Car, Tree, Person, and Terrain where applicable) for batch sizes of 4, 8, and 16. The table demonstrates how increasing the batch size improves the model’s performance.

read the caption

Table 8: Effectiveness of Batch Size.

Full paper#