↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Social influence maximization (SIM) algorithms often neglect fairness, focusing solely on maximizing information spread. Existing fairness metrics, which measure fairness in terms of expected outreach per group, are insufficient because they ignore the stochastic nature of the diffusion process. These metrics can classify highly unfair scenarios (e.g., one group consistently receives no information) as fair due to balanced expectations.

This research proposes a new fairness metric, ‘mutual fairness’, based on optimal transport theory. Instead of considering marginal outreach probabilities, this metric leverages the joint probability distribution of outreach among different groups. Mutual fairness is more sensitive to variability in outreach and provides a more accurate assessment of fairness. A novel seed-selection algorithm is designed to optimize both outreach and mutual fairness, demonstrating improved fairness on real datasets with minimal or no efficiency loss.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in social network analysis, AI ethics, and fairness-aware algorithm design. It challenges existing fairness metrics in social influence maximization, proposing a novel approach that is more robust and nuanced. The work also introduces a novel seed-selection algorithm that optimizes both fairness and efficiency, paving the way for fairer information dissemination strategies and more equitable algorithmic design.

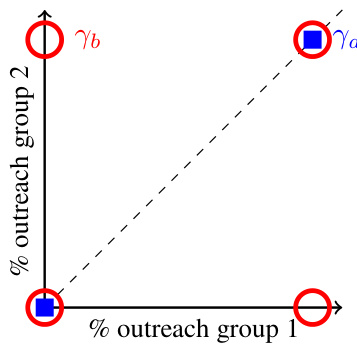

Visual Insights#

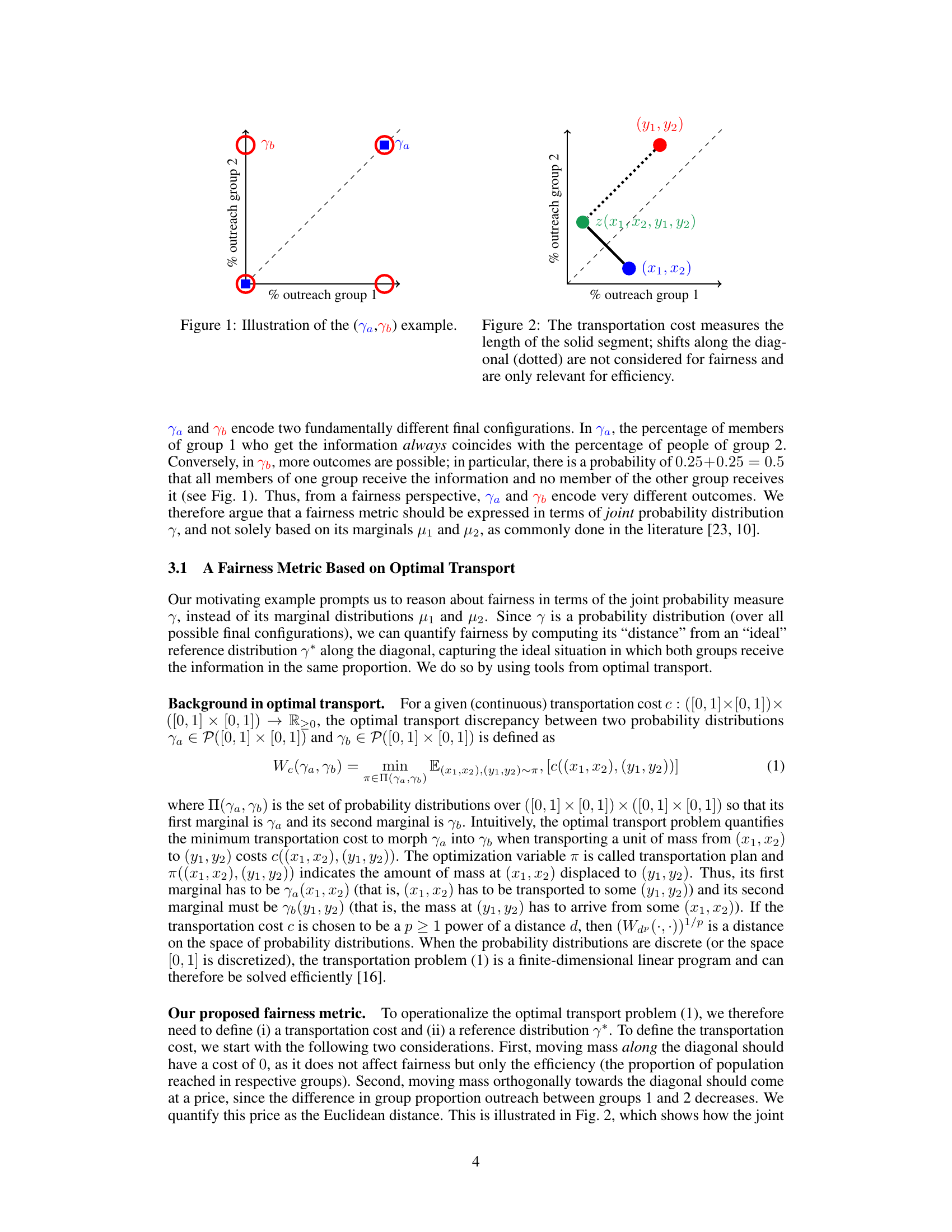

This figure illustrates two different probability distributions, Ya and Yb, over the final configurations of outreach to two groups. Ya represents a perfectly fair scenario where the percentage of members of each group who receive the information is always equal. Yb, in contrast, shows a situation with unfair outcomes, where in 50% of cases, all members of one group receive information and none from the other, and vice-versa in the other 50%. While both have the same marginal outreach probability distributions, their joint distributions showcase a critical difference in fairness, highlighting the limitation of fairness metrics relying solely on marginal distributions.

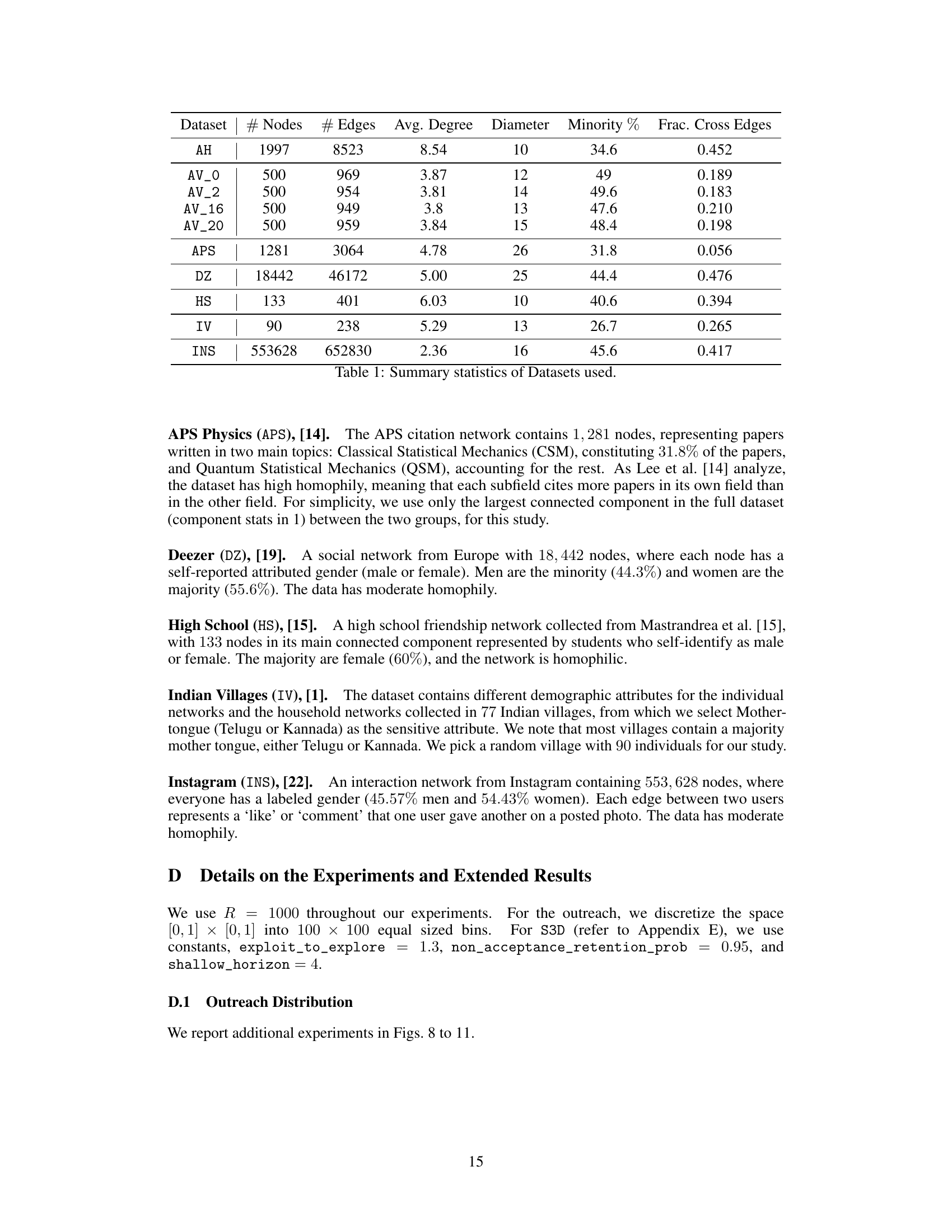

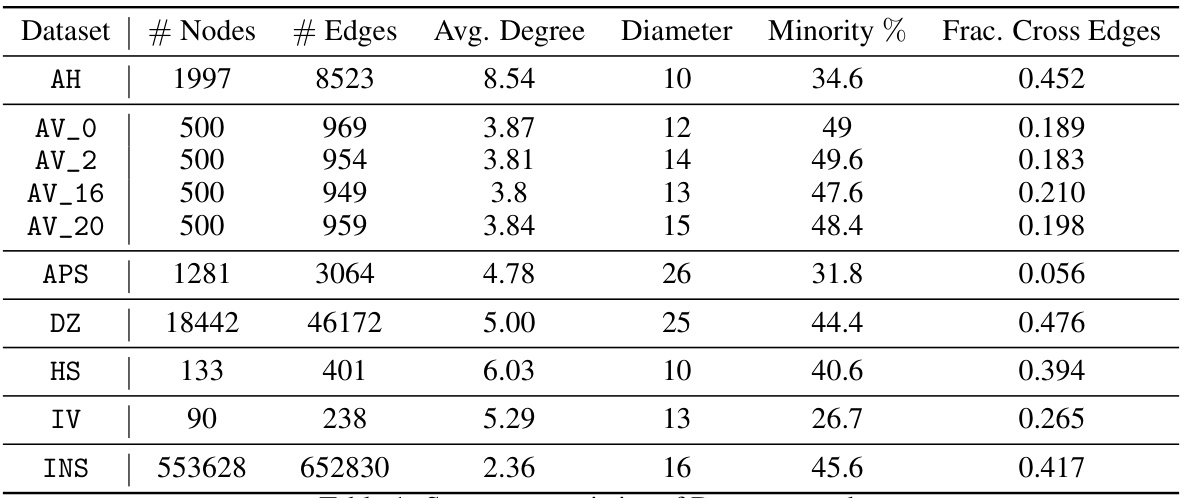

This table presents a summary of the characteristics of the ten datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it provides the number of nodes, the number of edges, the average node degree, the diameter, the percentage of the minority group, and the fraction of cross-edges. The datasets represent various real-world social networks, with varying sizes and levels of group homogeneity.

In-depth insights#

Fairness Metrics#

The concept of fairness in algorithmic systems is multifaceted, and defining appropriate fairness metrics is crucial. Different fairness metrics capture different aspects of fairness. Individual fairness focuses on ensuring similar treatment for similar individuals, while group fairness aims for equitable outcomes across different demographic groups. Equality of opportunity and equality of outcome represent distinct fairness goals, focusing on equal chances versus equal results. Choosing a metric depends heavily on the context and the specific values being prioritized. There is no single universally accepted fairness metric; instead, the selection process should be explicitly justified and transparent, acknowledging that achieving perfect fairness across all dimensions is often unattainable. Furthermore, the development and application of fairness metrics require careful consideration of potential biases and unintended consequences, underscoring the need for ongoing research and critical evaluation in this area.

Optimal Transport#

The concept of ‘Optimal Transport’ in the context of this research paper is a powerful mathematical framework used to quantify fairness in social influence maximization. It addresses the limitations of traditional fairness metrics that focus solely on expected values by considering the entire probability distribution of outreach across different communities. Optimal transport helps to measure the ‘distance’ between the observed outreach distribution and a perfectly fair distribution, where all communities are equally reached. This distance is used to define a novel fairness metric called ‘mutual fairness,’ which captures the variability of outcomes resulting from the inherent stochasticity of information diffusion processes. Mutual fairness allows for a more nuanced understanding of fairness, beyond simple averages, thus enabling the design of algorithms that prioritize both influence maximization and fair dissemination of information across all groups.

Seed Selection#

The concept of seed selection in influence maximization is crucial, impacting the effectiveness and fairness of information dissemination. Optimal seed selection aims to identify a small set of influential nodes that maximize the spread of information throughout a network. However, simply selecting nodes based on centrality metrics often neglects fairness considerations, potentially exacerbating existing biases. The research emphasizes the importance of fairness-aware seed selection, moving beyond traditional approaches that focus solely on efficiency. This necessitates the development of new metrics that account for the variability and stochastic nature of influence propagation across different groups. Optimal transport theory provides a valuable framework for quantifying fairness, capturing the spread across diverse groups more effectively than existing methods. Algorithms that simultaneously optimize both efficiency and fairness, using optimal transport, are proposed and demonstrated to be superior in real-world datasets.

Real-World Tests#

A robust evaluation of fairness-aware algorithms necessitates real-world testing. This involves applying the algorithms to diverse social network datasets representing different structures and demographics, and measuring their performance using metrics that go beyond simple averages. The selection of datasets is crucial, ensuring variety in size, density, community structure, and the distribution of sensitive attributes. Results should detail the tradeoff between fairness and efficiency, showing how different algorithms balance equitable information dissemination with overall reach. Statistical significance testing is essential to confirm whether observed differences in fairness or efficiency are truly meaningful, not merely due to random variation. By analyzing real-world data, researchers can evaluate whether their algorithms generalize beyond theoretical settings, and identify any biases or limitations that become apparent only in real-world contexts. Transparency in data selection and analysis is key, as it fosters reproducibility and trust in the findings. The ultimate goal is to provide concrete evidence of how well fairness-enhancing algorithms perform in realistic scenarios.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore extending the optimal transport framework to handle more complex fairness notions, such as individual fairness or notions incorporating group size and connectivity. Investigating the impact of different diffusion models on the proposed fairness metric and the algorithm’s performance is also crucial. Furthermore, developing more efficient seed selection algorithms that scale better with network size is needed. A comprehensive analysis comparing various fairness metrics across diverse real-world scenarios would provide valuable insights and potentially inform the development of more robust and context-aware fairness measures. Finally, exploring the algorithm’s effectiveness in dynamic environments where network structure and group membership can change over time would significantly enhance its practical applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

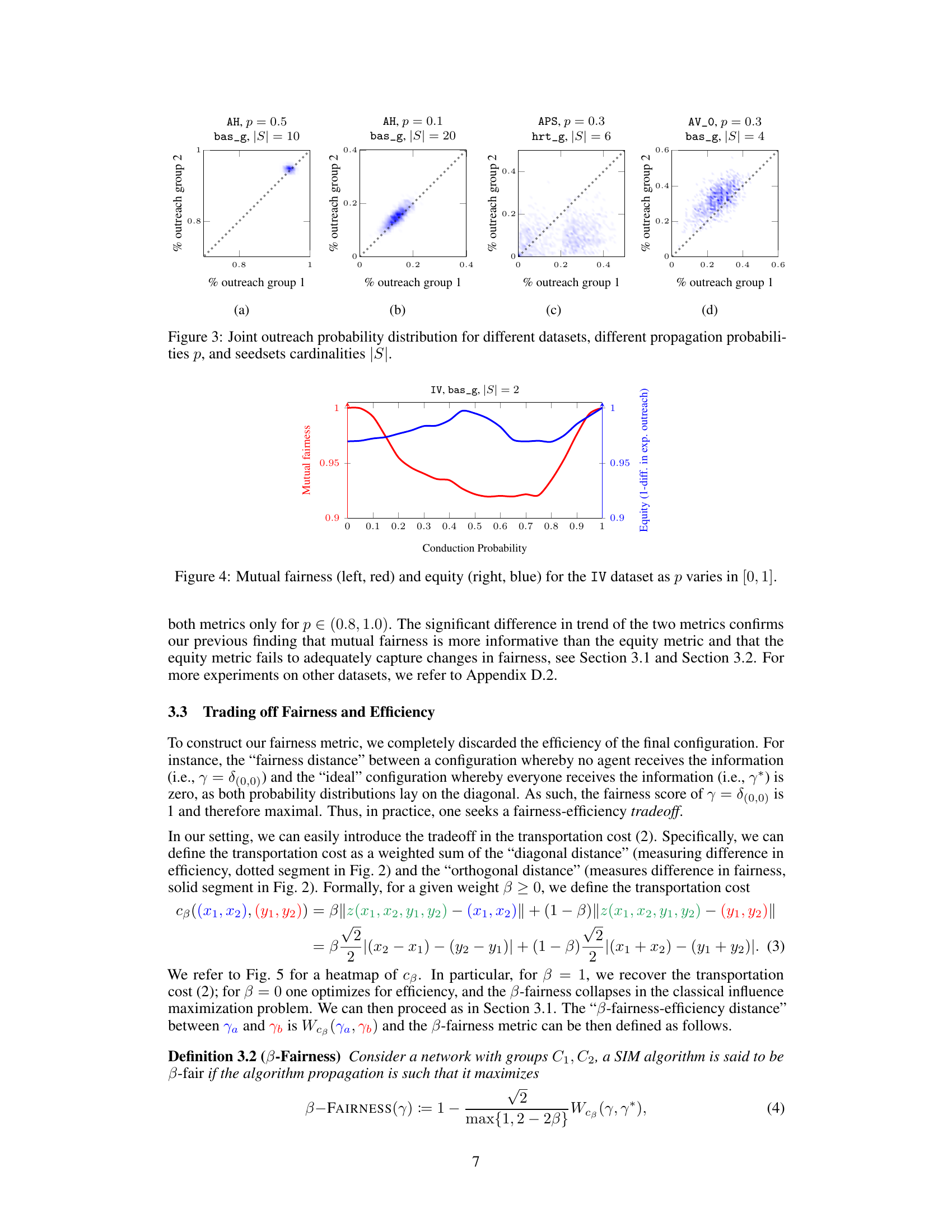

This figure illustrates the concept of transportation cost in the context of optimal transport theory. The transportation cost is represented by the length of a line segment connecting two points representing outreach proportions for two groups. The diagonal line represents an ideal scenario where both groups have equal outreach. Movement along the diagonal affects efficiency, but not fairness. Movement perpendicular to the diagonal affects fairness, with larger distances representing greater unfairness. This helps to quantify fairness based on the probability distribution of outreach.

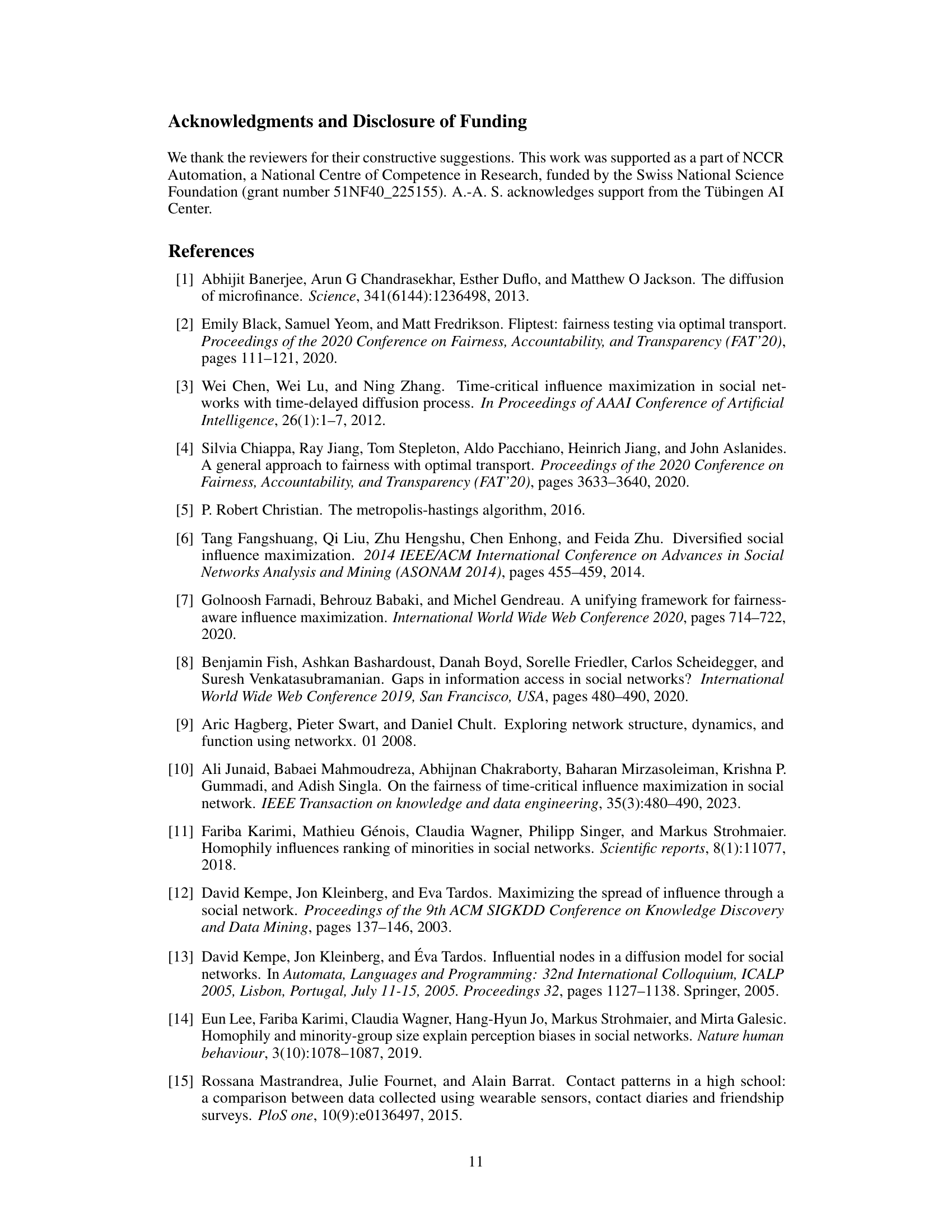

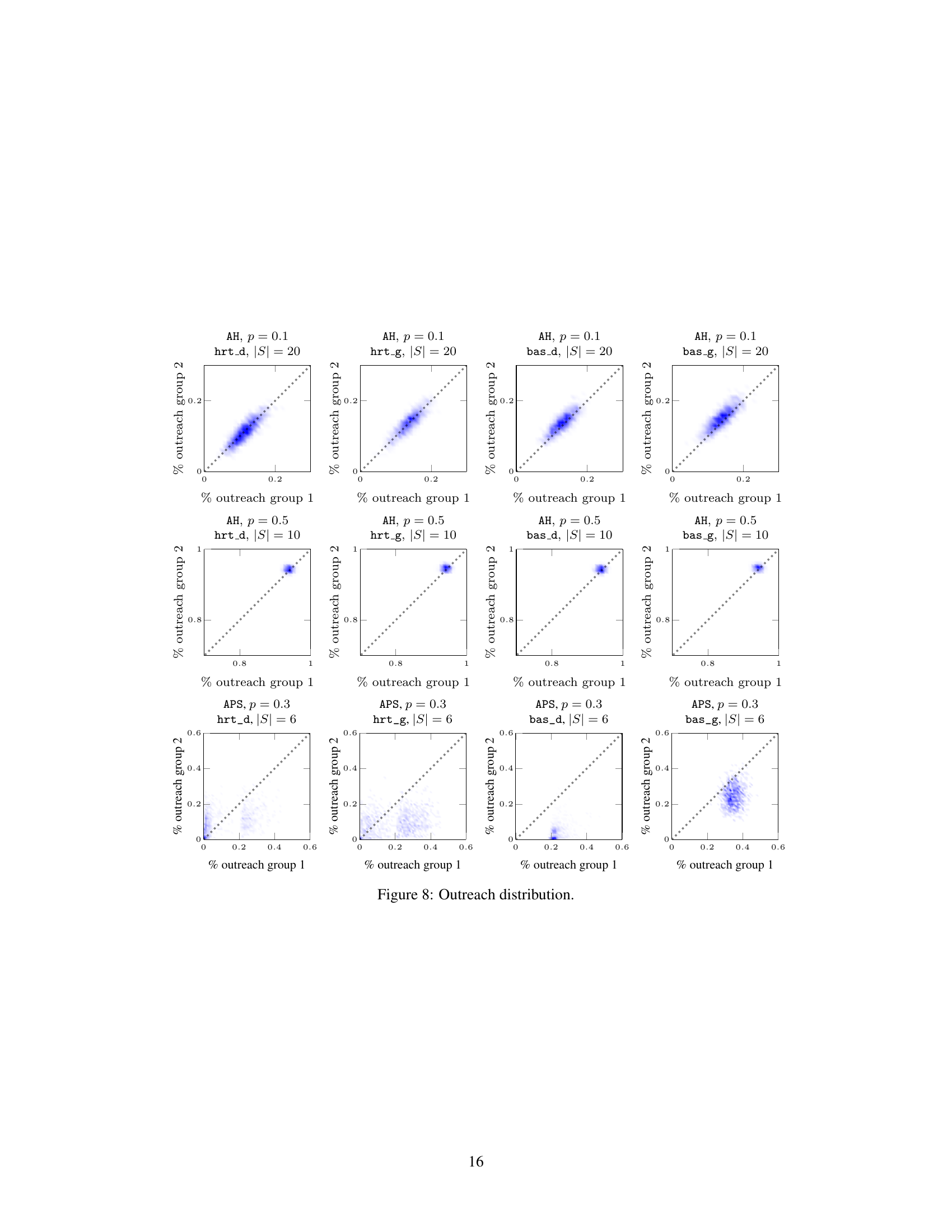

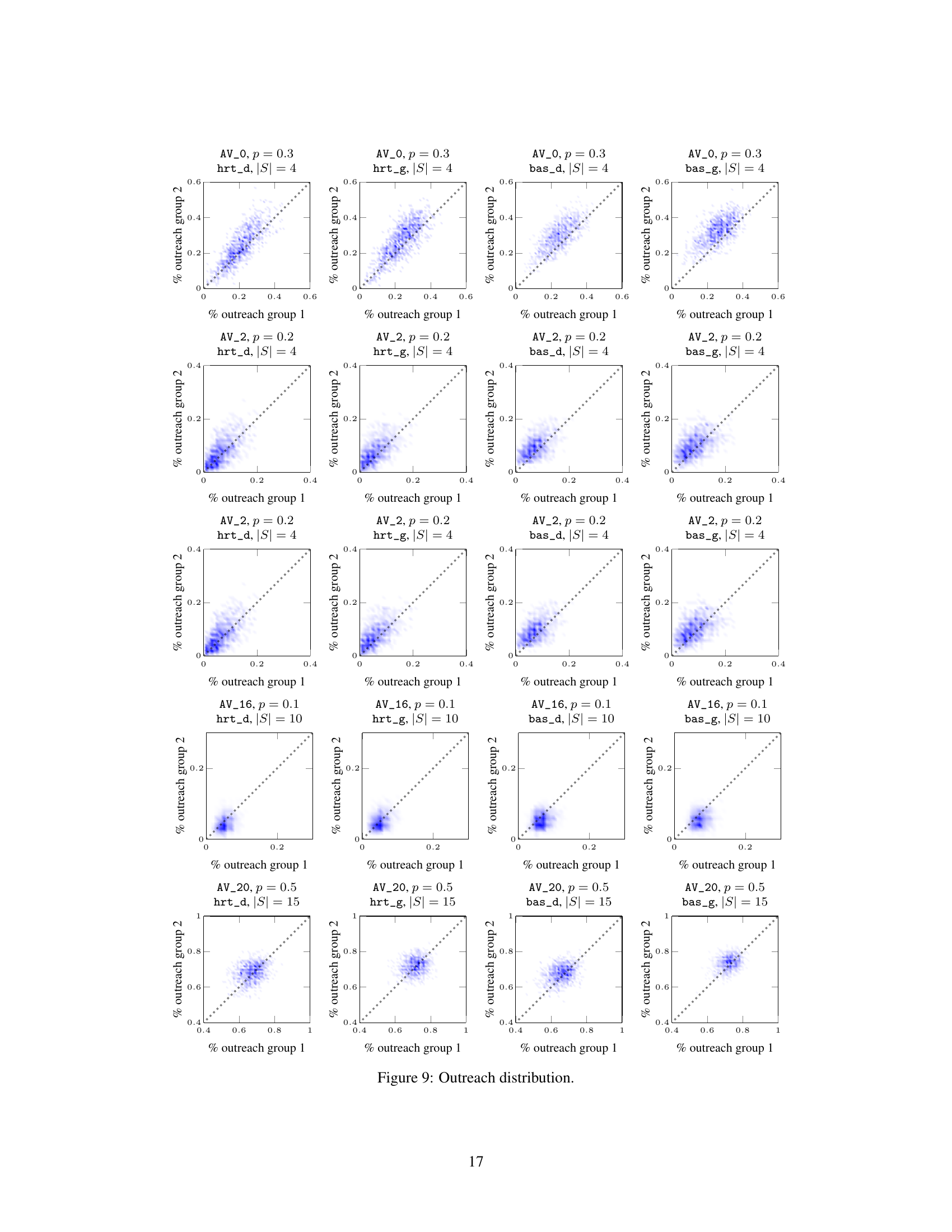

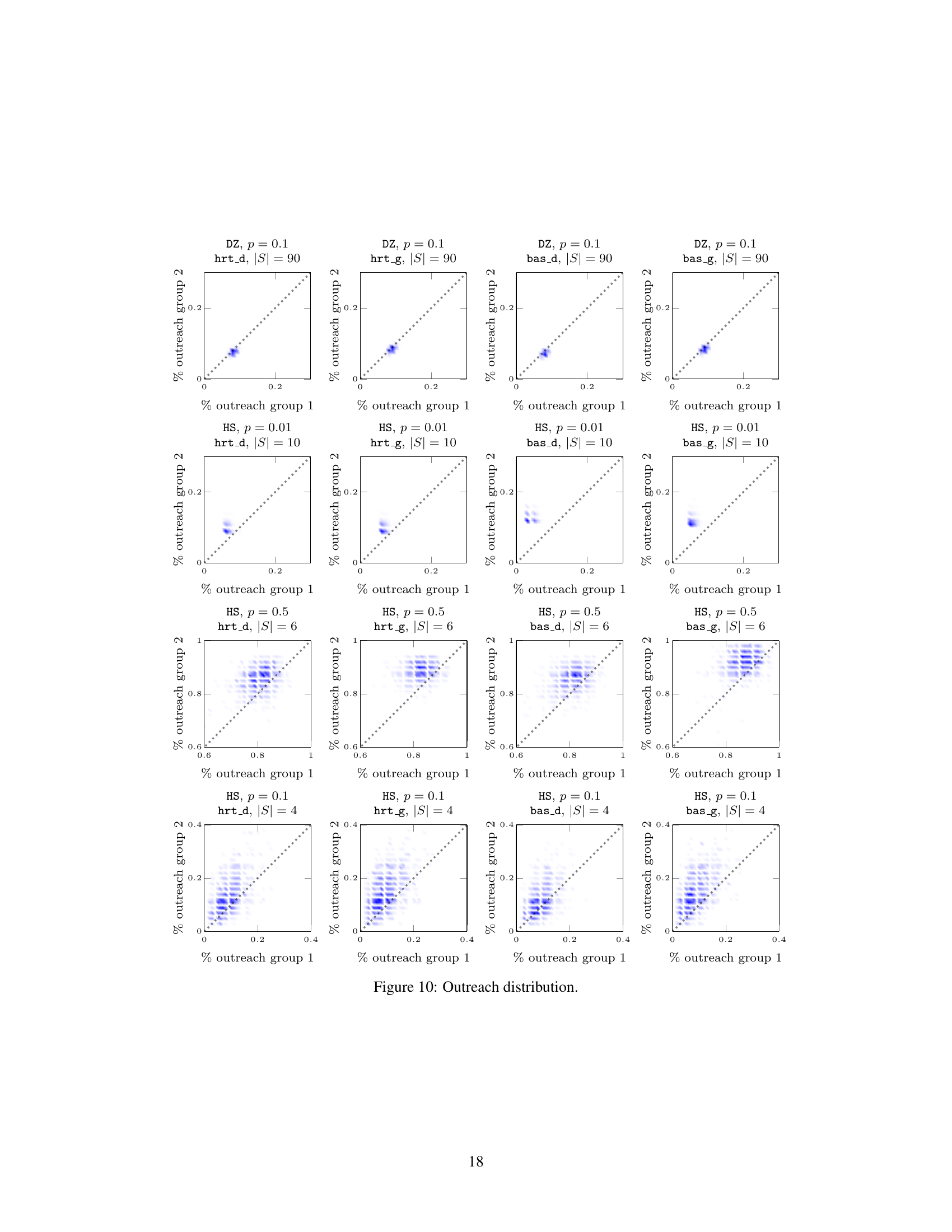

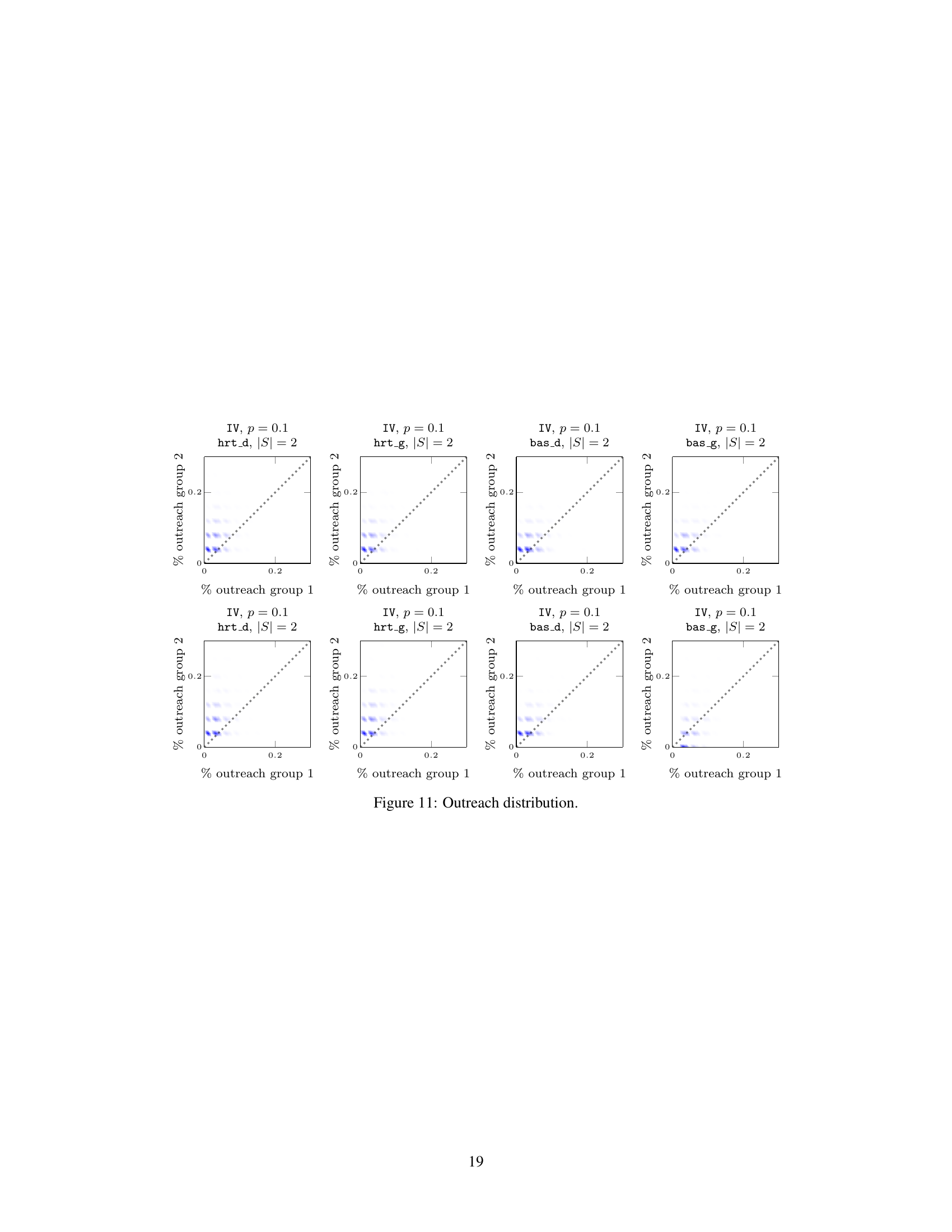

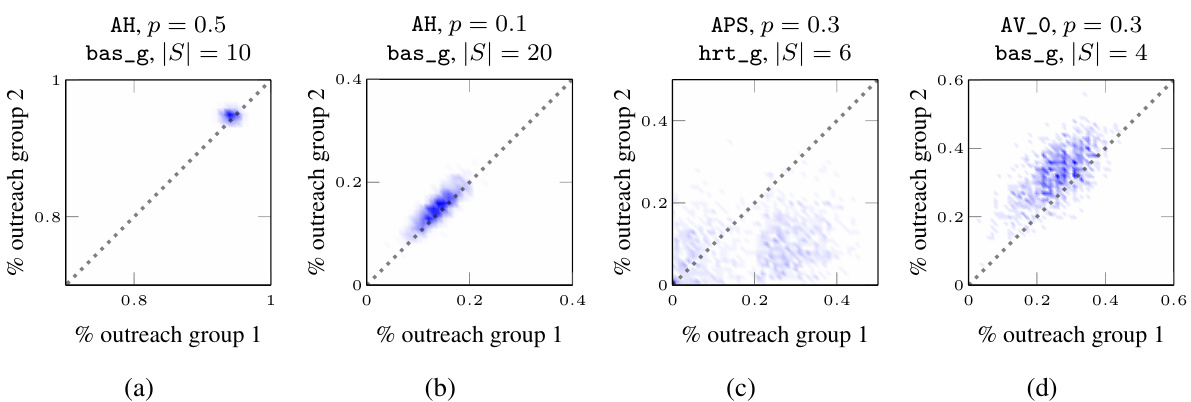

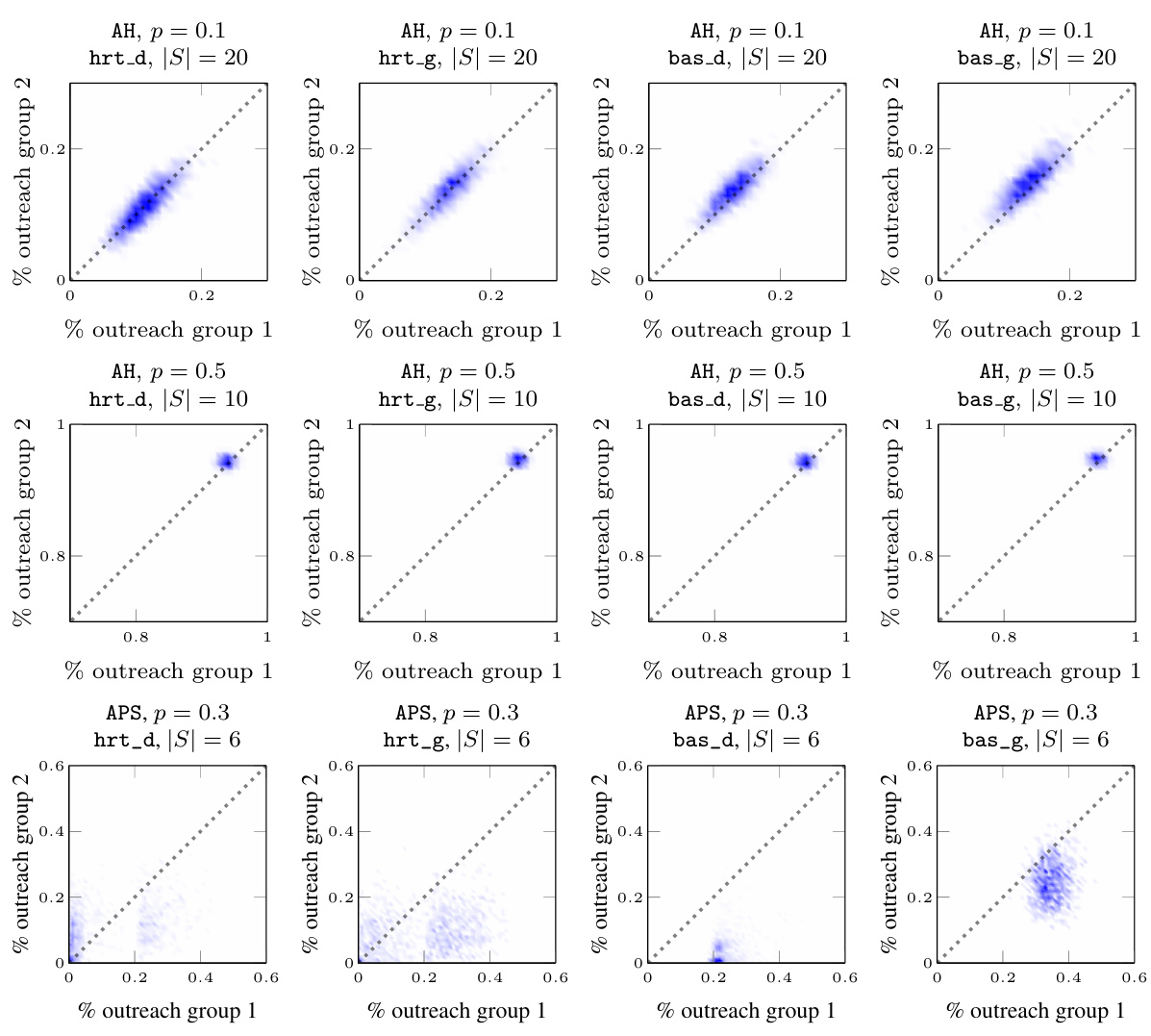

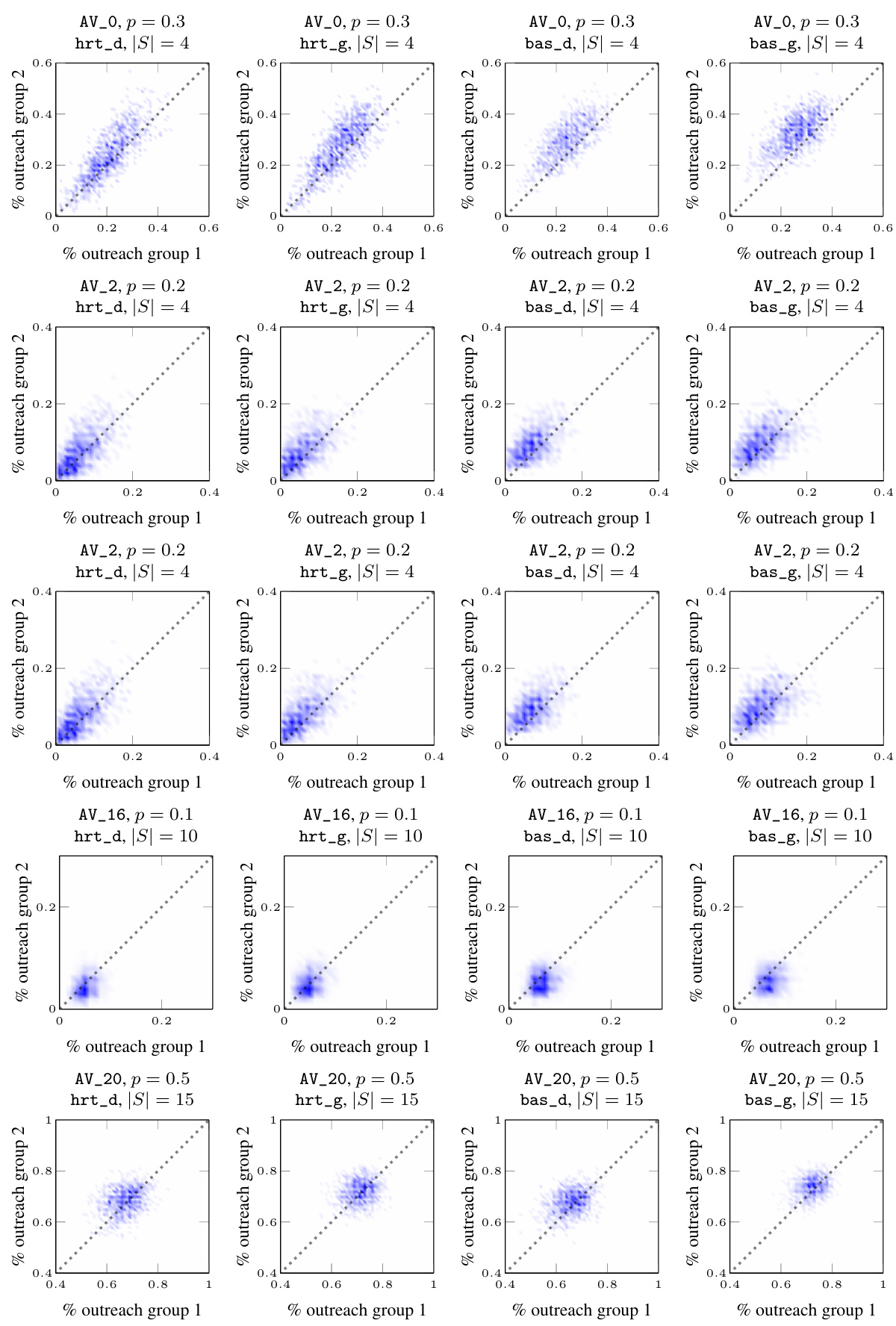

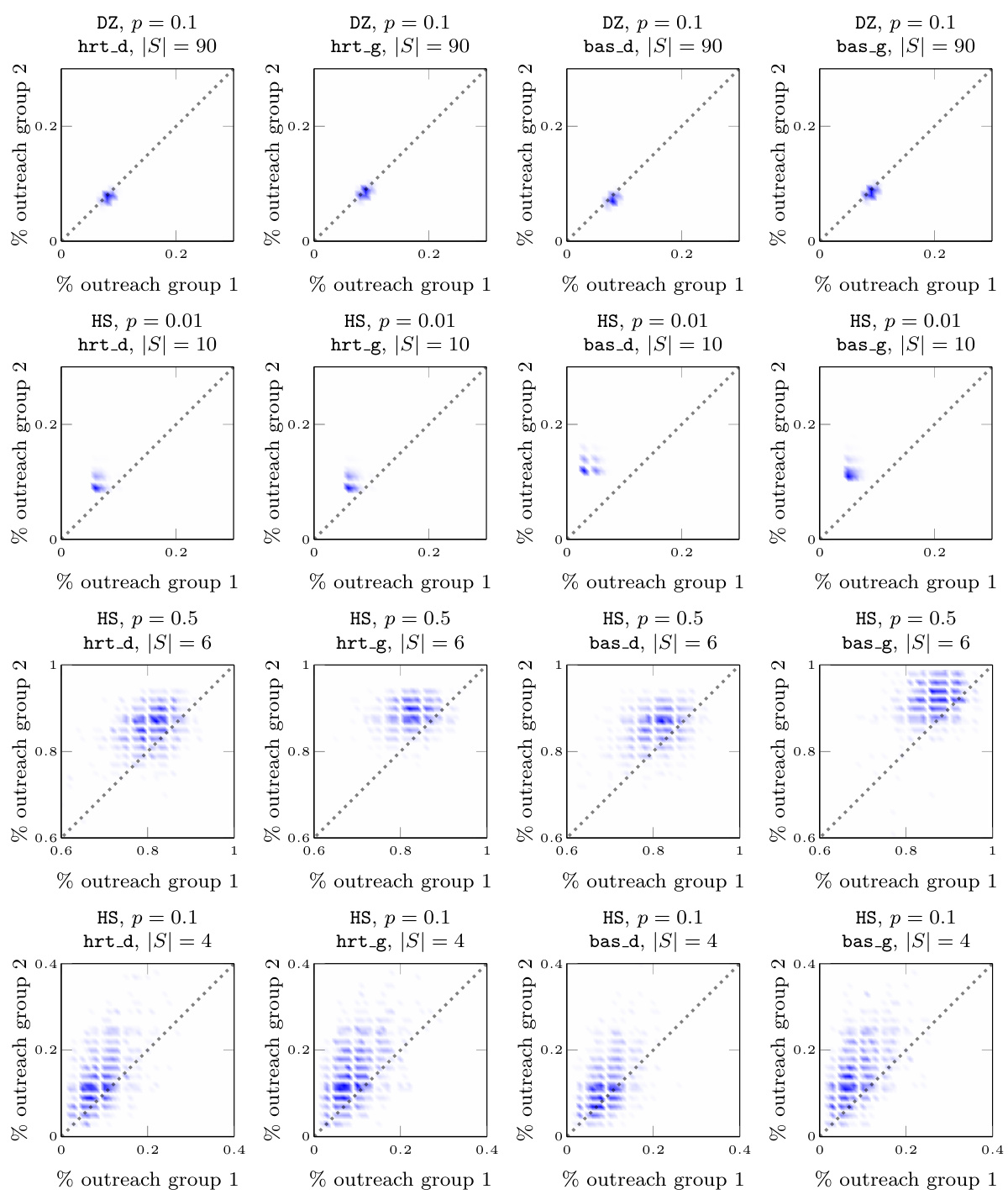

This figure visualizes the joint probability distribution of outreach across two groups for various datasets under different settings. Each subplot represents a specific dataset, propagation probability (p), and seedset cardinality (|S|). The x and y axes represent the fraction of nodes reached in each group, while the color intensity indicates the probability of observing that particular combination of outreach fractions. The plots show that the distribution can vary considerably across different datasets and parameters, ranging from highly deterministic and fair (concentrated near the diagonal) to highly stochastic and unfair (spread across the plot).

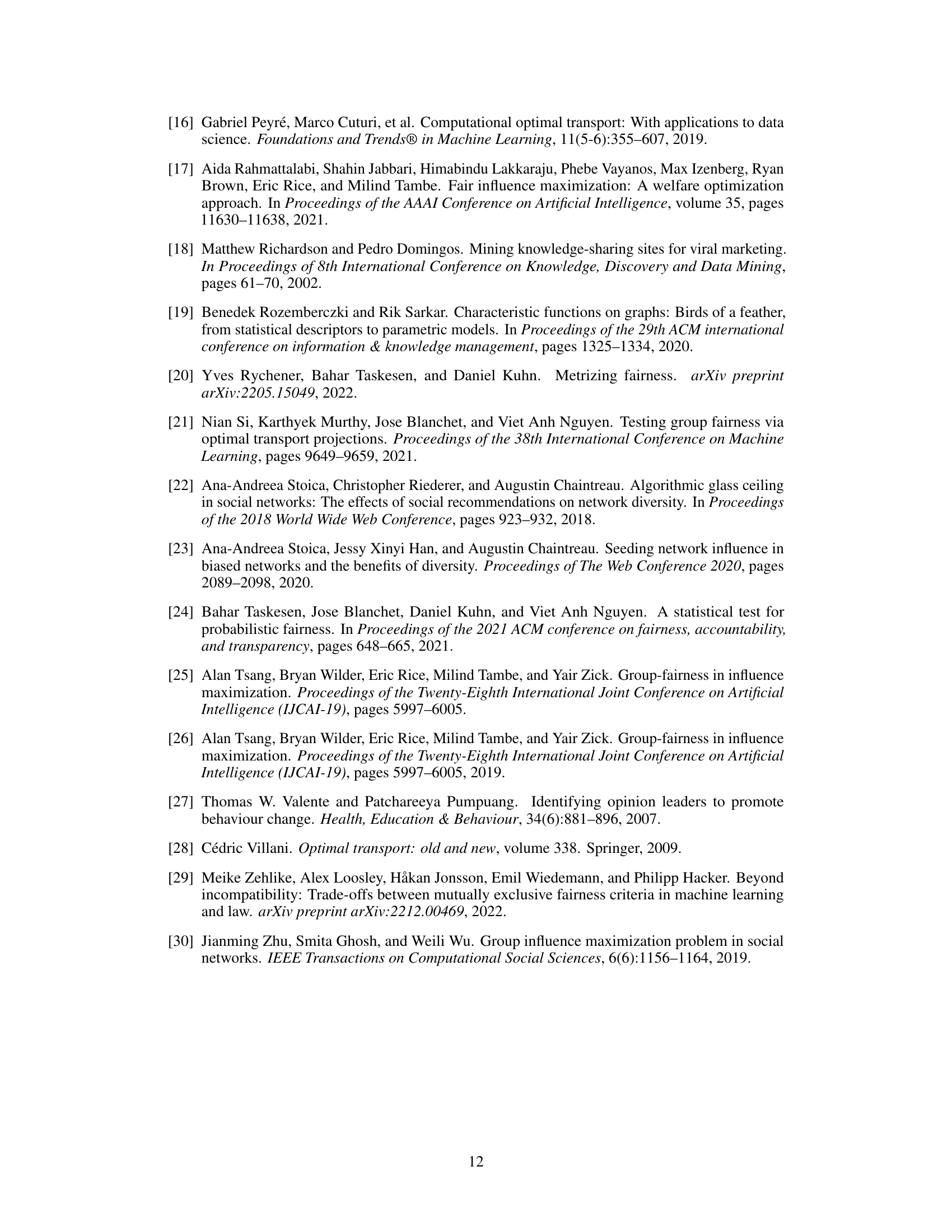

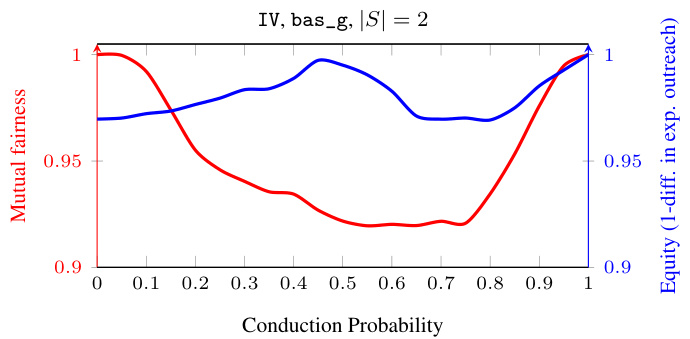

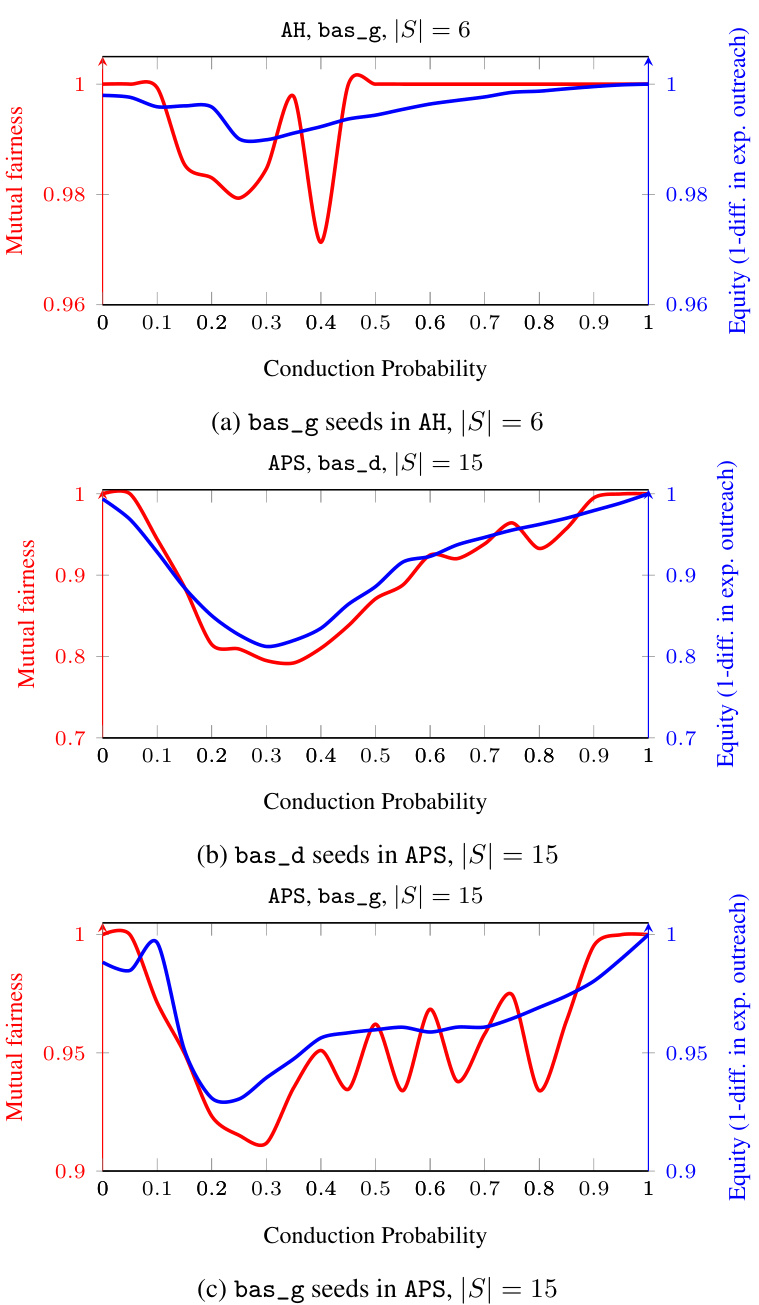

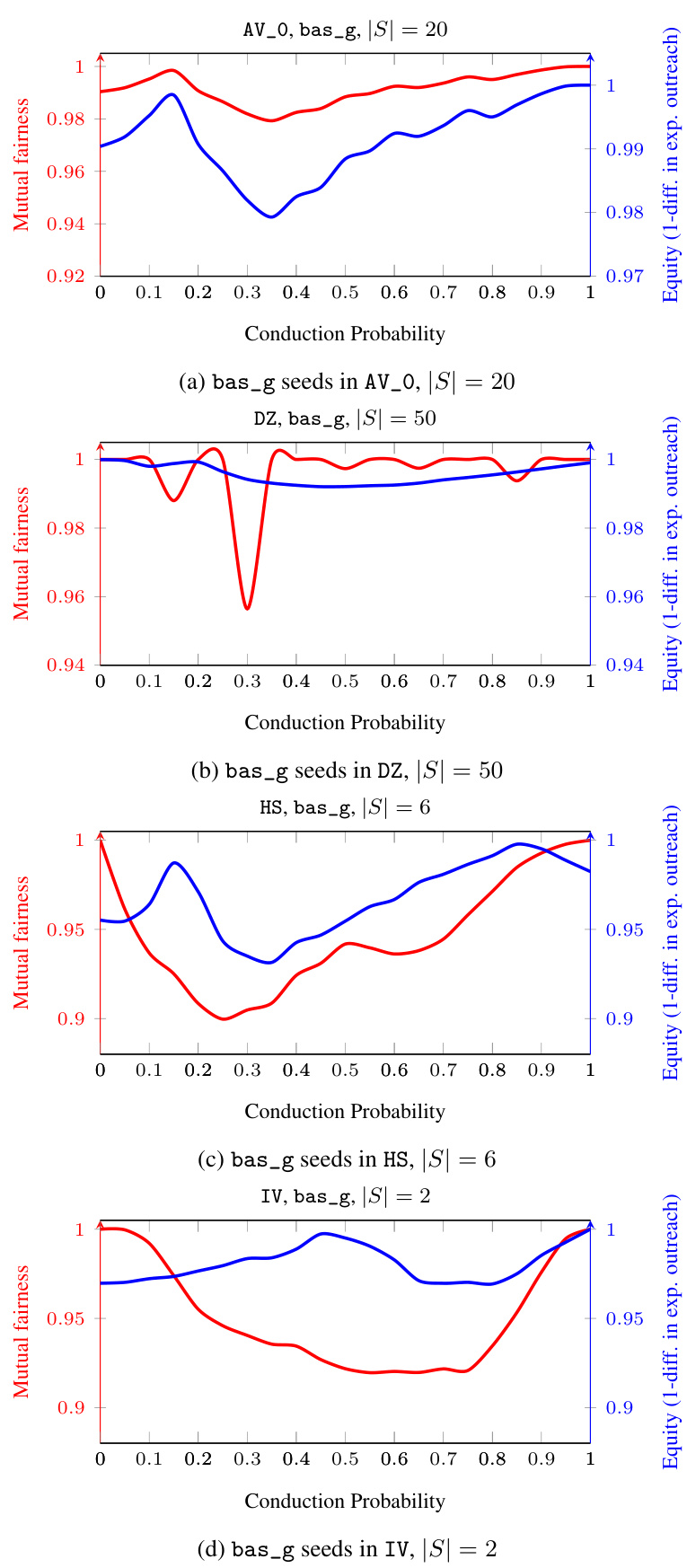

This figure shows a comparison of mutual fairness and equity metrics for the Indian Villages (IV) dataset as the conduction probability (p) varies from 0 to 1. The x-axis represents the conduction probability, while the y-axis displays both mutual fairness (red) and equity (blue). Mutual fairness, a novel metric proposed in the paper, captures the variability in outreach across different groups. Equity is a more traditional fairness metric that focuses on the expected outreach ratio across groups. The figure highlights the differences between these two metrics, showing how mutual fairness can provide a more nuanced view of fairness than equity, especially in situations with significant variability in outreach. It reveals a clear divergence between the two fairness metrics.

This figure shows the cost of transporting mass from any point (x1, x2) to the ideal point (1, 1), where both groups receive the information, for different values of beta. Beta is a weighting parameter that balances the emphasis on fairness versus efficiency. When beta = 0, only efficiency is considered; when beta = 1, only fairness is considered; and intermediate values of beta represent a trade-off between fairness and efficiency. The colormap represents the transportation cost, with yellow indicating low cost and dark blue indicating high cost.

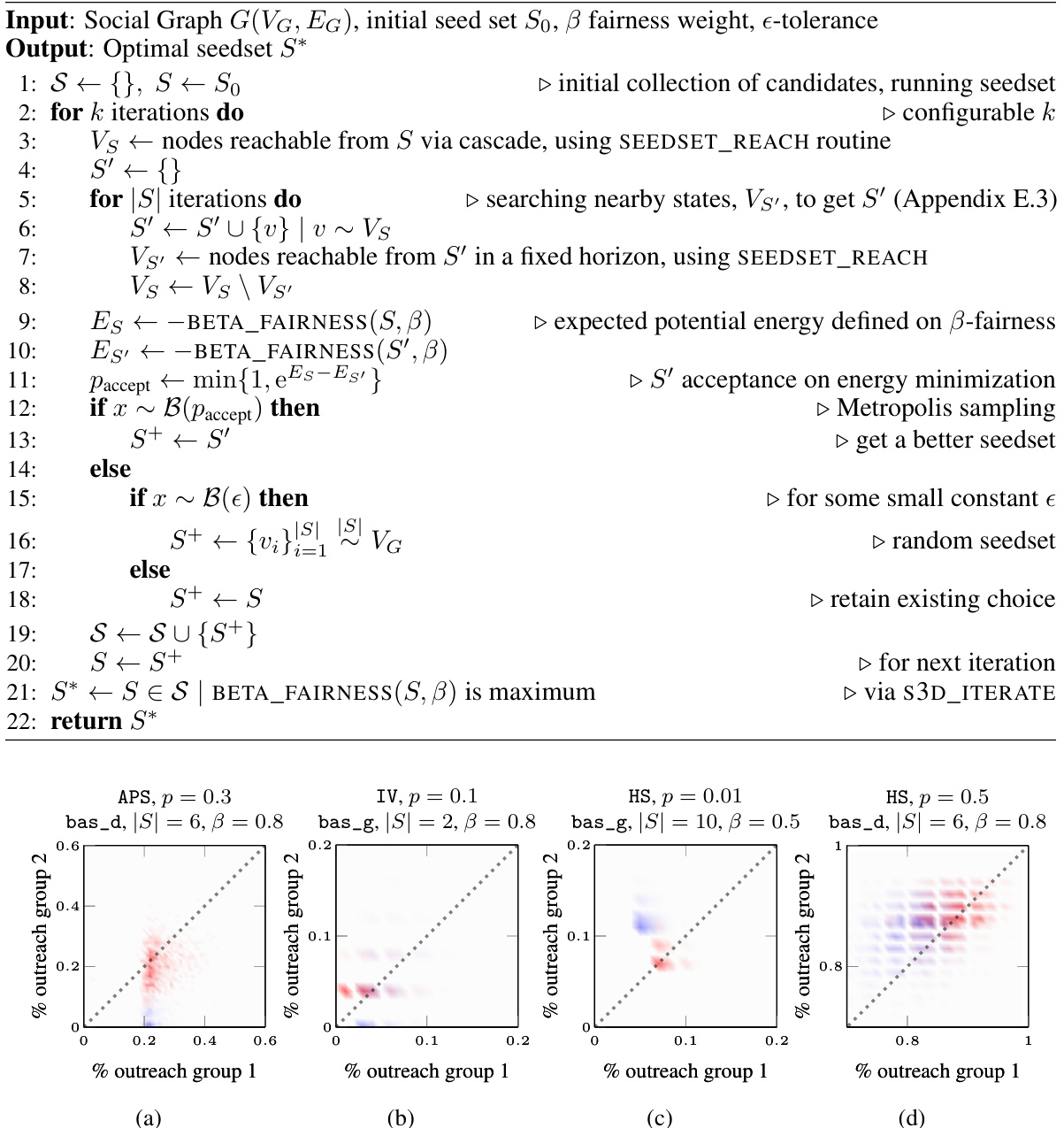

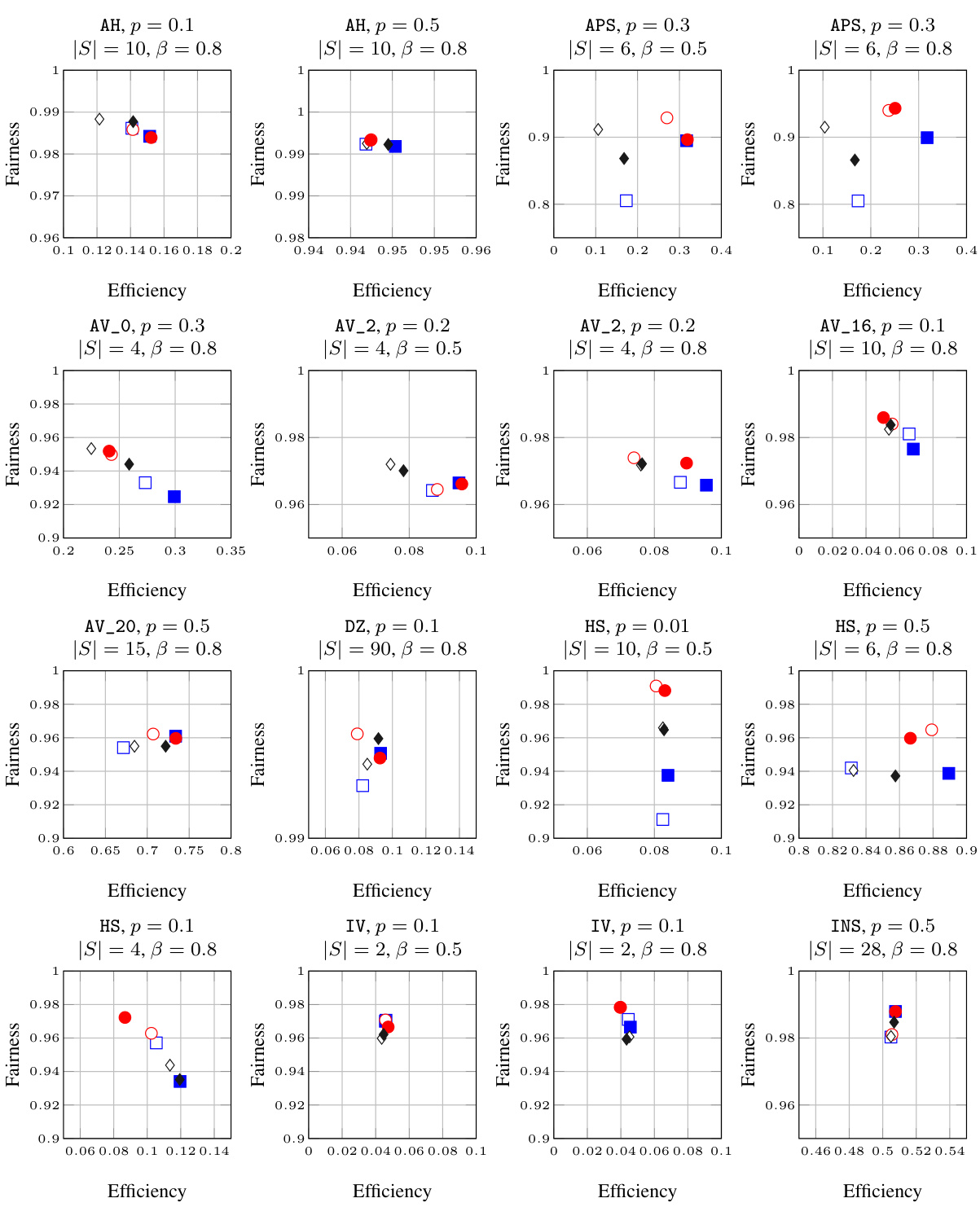

This figure compares the performance of the proposed S3D algorithm (red) against label-blind baseline algorithms (blue) across various datasets. The plots show the joint probability distribution of outreach for each group, illustrating the impact of the algorithm on fairness and efficiency. Different datasets, probabilities of information spread (p), seed set sizes (|S|), and fairness-efficiency trade-off parameters (β) are used. The figure highlights that S3D often improves both fairness and efficiency, especially in some scenarios where the improvement in efficiency is substantial.

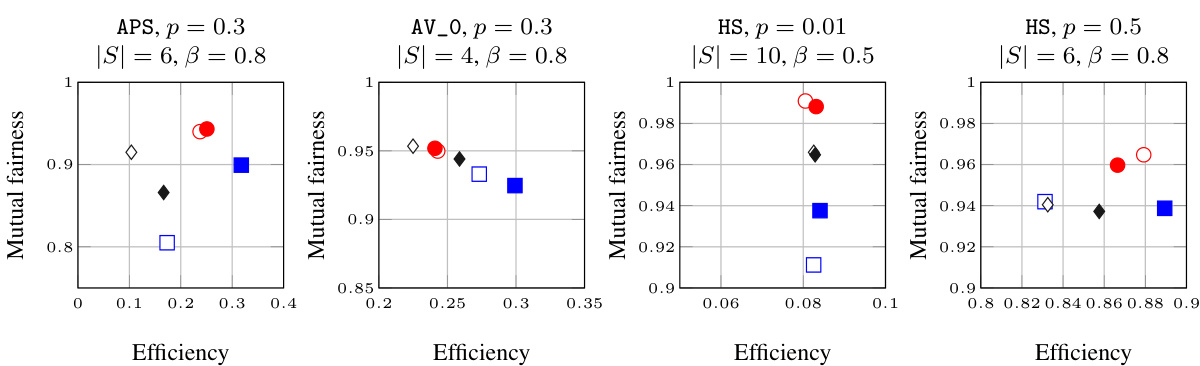

This figure compares the performance of the proposed S3D algorithm with other label-aware and label-blind algorithms across various datasets, considering different propagation probabilities, seed set sizes, and fairness-efficiency trade-offs (β). The results show the trade-off between fairness (mutual fairness metric) and efficiency (outreach). The filled markers represent greedy-based algorithms, while empty markers represent degree-based algorithms.

This figure visualizes the joint probability distribution of outreach across two groups for various datasets under different settings. Each subplot represents a specific dataset, propagation probability (p), and seedset cardinality (|S|). The x and y axes show the percentage of nodes reached in each group, and the density of points indicates the probability of observing a particular combination of outreach percentages. The diagonal represents perfect fairness, where both groups have the same outreach percentage. Deviations from the diagonal suggest an imbalance in information diffusion across the groups. The plots illustrate how the distribution varies depending on the dataset, propagation probability, and seed selection strategy used.

This figure shows the joint probability distribution of outreach for different datasets and seed selection strategies. Each plot represents the probability that a certain fraction of nodes in each group receives the information. The plots reveal how different parameters influence the balance (fairness) of outreach. The plots showcase various outreach patterns: almost deterministic and highly fair/efficient, fair with some stochasticity, highly stochastic (unfair), and biased stochastic.

This figure visualizes the joint probability distribution of outreach across two groups for various datasets under different parameters. Each subplot represents a dataset with specific parameters (propagation probability and seedset size). The x and y axes represent the percentage of each group reached, allowing for a visual assessment of fairness and efficiency. The diagonal line represents perfect fairness (equal outreach across groups), with deviations indicating unfair outcomes. The concentration of points around the diagonal suggests a high level of fairness, while deviations from this line illustrate how fairness varies across the experiments. The density of points in the scatter plots visualizes the probability of each possible combination of outreach across the two groups. This figure directly addresses the limitations of using only marginal probabilities in measuring fairness, as highlighted in the paper.

This figure visualizes the joint probability distribution of outreach across two groups for various datasets under different settings. Each subplot represents a dataset and illustrates the probability of achieving different levels of outreach in each group. The plots showcase how different parameters such as the propagation probability (p) and seedset cardinality (|S|) impact the outreach distribution and, consequently, the fairness of the information diffusion process.

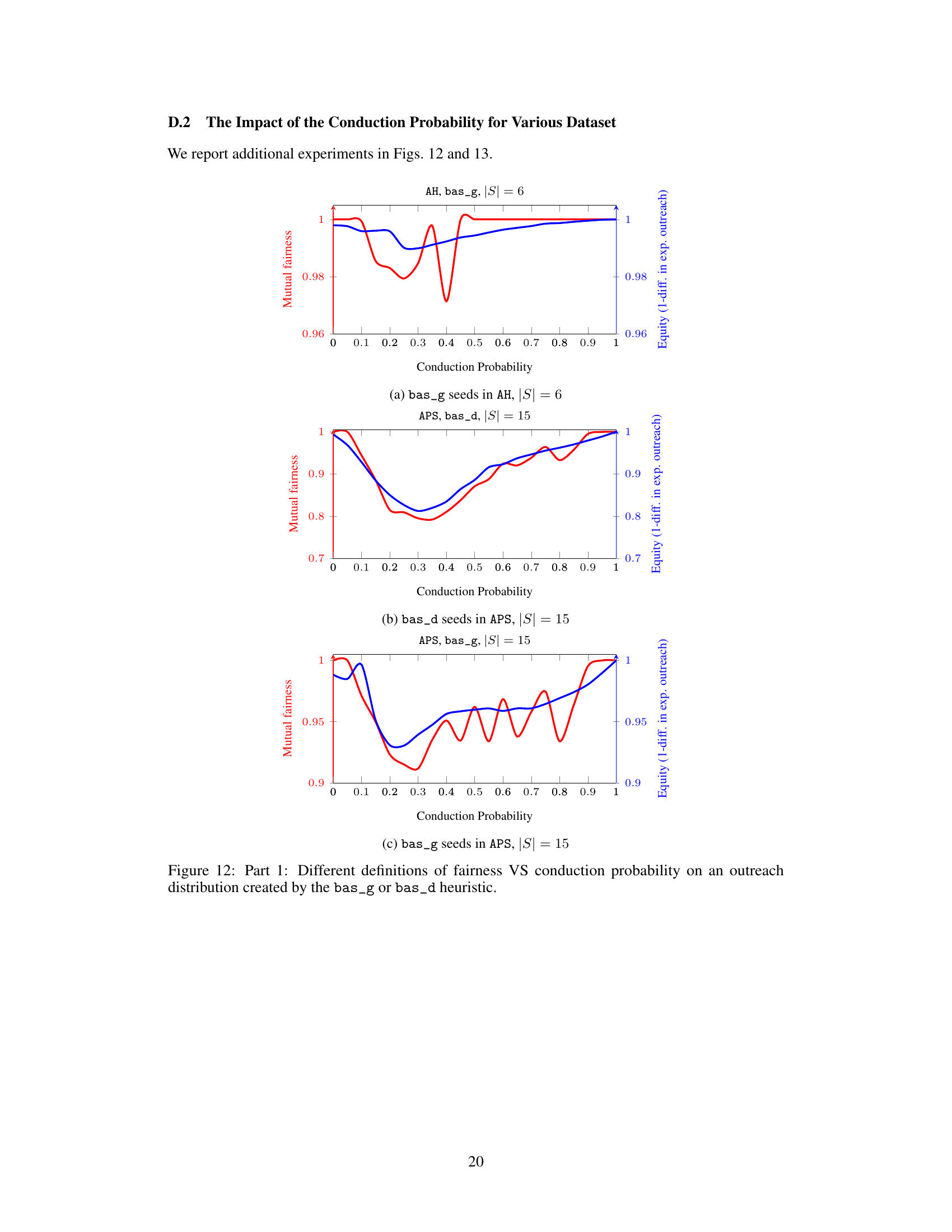

The figure shows the mutual fairness and equity for different datasets (AH, APS) with different seed selection strategies (bas_g, bas_d) and varying conduction probabilities (p). Mutual fairness is a new metric introduced in the paper that considers the joint probability distribution of outreach across groups, unlike traditional equity metrics that only look at marginal expected values. The plots show that mutual fairness can differ significantly from equity, highlighting the limitations of traditional metrics in capturing the stochastic nature of influence diffusion processes. The differences are especially pronounced in the intermediate probability range.

The figure shows a comparison of two fairness metrics, mutual fairness and equity, as the conduction probability (p) varies from 0 to 1 for the Indian Villages dataset. Mutual fairness is represented by the red line and equity by the blue line. The plot illustrates how these metrics behave differently across different probabilities of information transmission. It highlights the divergence between the two metrics, indicating scenarios where equity might classify an outcome as fair while mutual fairness considers it less equitable, due to differences in how they account for variability in stochastic information diffusion processes.

This figure visualizes the joint probability distribution of outreach across two groups for various datasets under different settings. Each subplot represents a specific dataset, propagation probability (p), and seedset cardinality (|S|). The x and y axes represent the percentage outreach for each group. The distribution’s shape reveals insights into the fairness of information spread: a diagonal distribution indicates fairness, while a skewed distribution indicates bias.

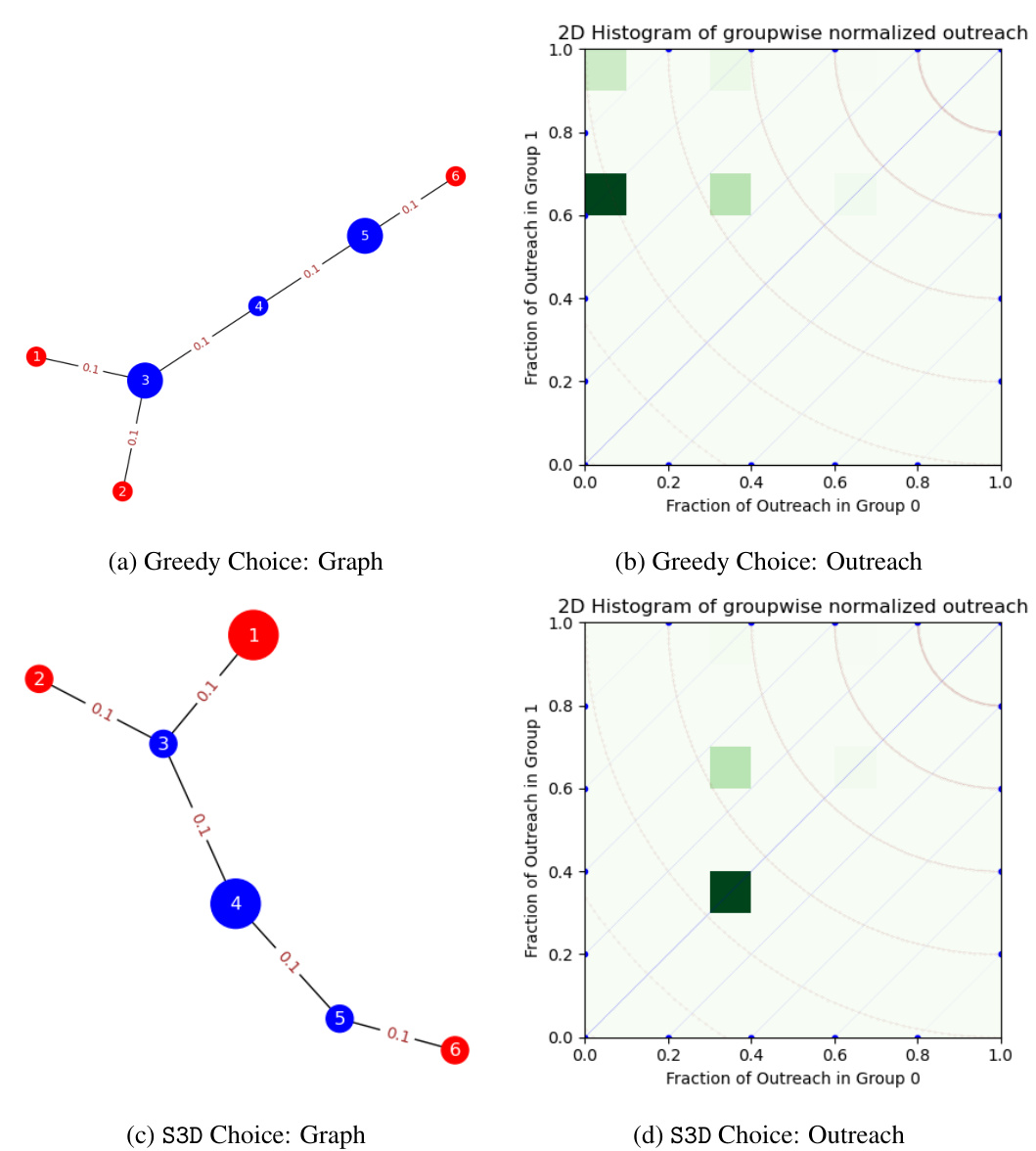

This figure shows a toy example comparing the greedy algorithm with the proposed S3D algorithm for seed selection in a small social network. The greedy algorithm selects seeds (nodes 3 and 5) that result in an unbalanced outreach towards group 0, while the S3D algorithm selects seeds (nodes 1 and 4) leading to a more fair outreach distribution across both groups.

More on tables

This table summarizes key statistics for seven real-world datasets used in the paper’s experiments on social influence maximization. For each dataset, it provides the number of nodes and edges, the average node degree, the network diameter, the percentage of the minority group within the population, and the fraction of cross-edges (edges connecting nodes from different groups). These statistics help characterize the network topology and group structure of each dataset, which are relevant factors in studying fairness in information diffusion.

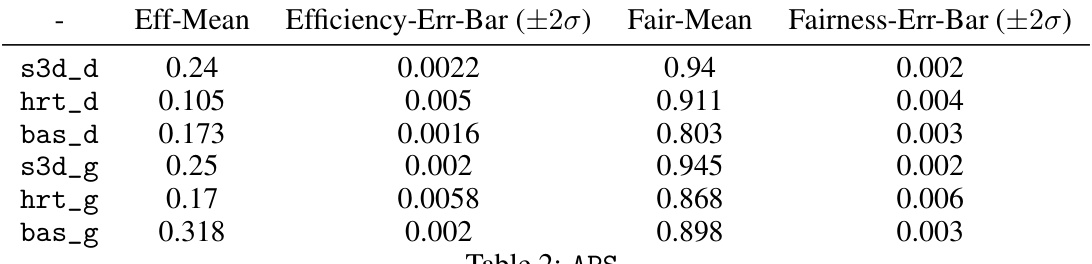

This table presents the mean and standard error of efficiency and fairness for different seed selection algorithms on the APS Physics dataset. The algorithms include degree centrality (bas_d), greedy (bas_g), degree-central fair (hrt_d), greedy fair (hrt_g), and the proposed Stochastic Seedset Descent (S3D) algorithm with both greedy and degree initializations (s3d_g and s3d_d). The results are based on 100,000 independent runs (100 times with R=1000) of the Independent Cascade diffusion model, and error bars represent ±2σ.

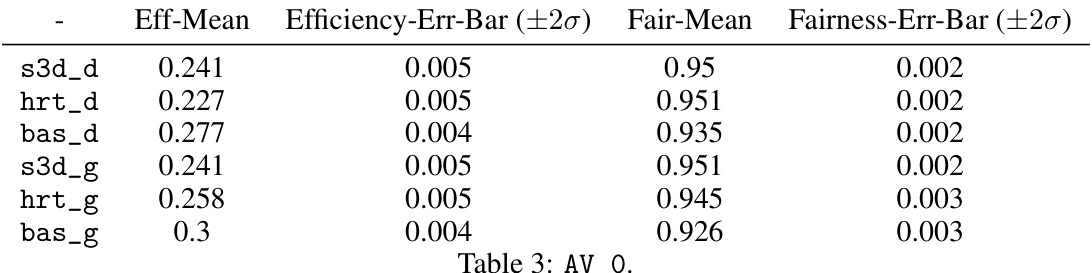

This table presents the mean and standard error of efficiency and fairness for six different seed selection algorithms on the AV_0 dataset. The algorithms are categorized into label-blind (bas_d, bas_g) and label-aware (hrt_d, hrt_g, s3d_d, s3d_g) approaches. The results show the performance of these algorithms in terms of both maximizing outreach (efficiency) and ensuring fairness in the information spread across groups.

This table presents the mean efficiency and fairness, along with their respective error bars (±2σ), for different seed selection algorithms on the High School dataset with a conduction probability (p) of 0.01. The algorithms compared include: S3D (our proposed algorithm) initialized with degree centrality (s3d_d) and greedy (s3d_g) heuristics; fair heuristics (hrt_d and hrt_g) from Stoica et al. [23]; and baselines based on degree centrality (bas_d) and greedy (bas_g) heuristics from Kempe et al. [12]. The table provides a quantitative comparison of the performance of various algorithms in terms of both efficiency and fairness.

This table presents the efficiency and fairness performance of different seed selection algorithms (s3d_d, hrt_d, bas_d, s3d_g, hrt_g, bas_g) on the HS dataset with a conduction probability of 0.5. For each algorithm, the mean efficiency and fairness scores are shown, along with their respective error bars (±2σ). The algorithms are categorized as label-aware (s3d, hrt) or label-blind (bas).

Full paper#