↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many AI fairness studies focus solely on prediction accuracy, neglecting how predictions are transformed into decisions. This can lead to bias amplification: even if a prediction model is fair, using a simple threshold to generate a binary decision might create unfair outcomes. This is particularly important in high-stakes settings like loan applications or hiring, where the downstream decision significantly impacts individuals.

This work addresses the issue by introducing a novel causal framework. It decomposes the disparity in binary decisions into components from the true outcome and those from the thresholding operation. The study introduces ‘margin complements’ to quantify the change caused by thresholding. Under suitable assumptions, it shows that the causal influence from protected attributes on the prediction score equals their influence on the true outcome, providing a clear decomposition of bias. The paper proposes new notions of ‘weak’ and ‘strong business necessity’ to guide fair decision-making and provides an algorithm for assessing them.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals how seemingly fair AI prediction models can amplify existing biases when used in real-world decision-making. This highlights the urgent need for regulatory oversight and motivates further research into bias mitigation techniques within the AI decision pipeline.

Visual Insights#

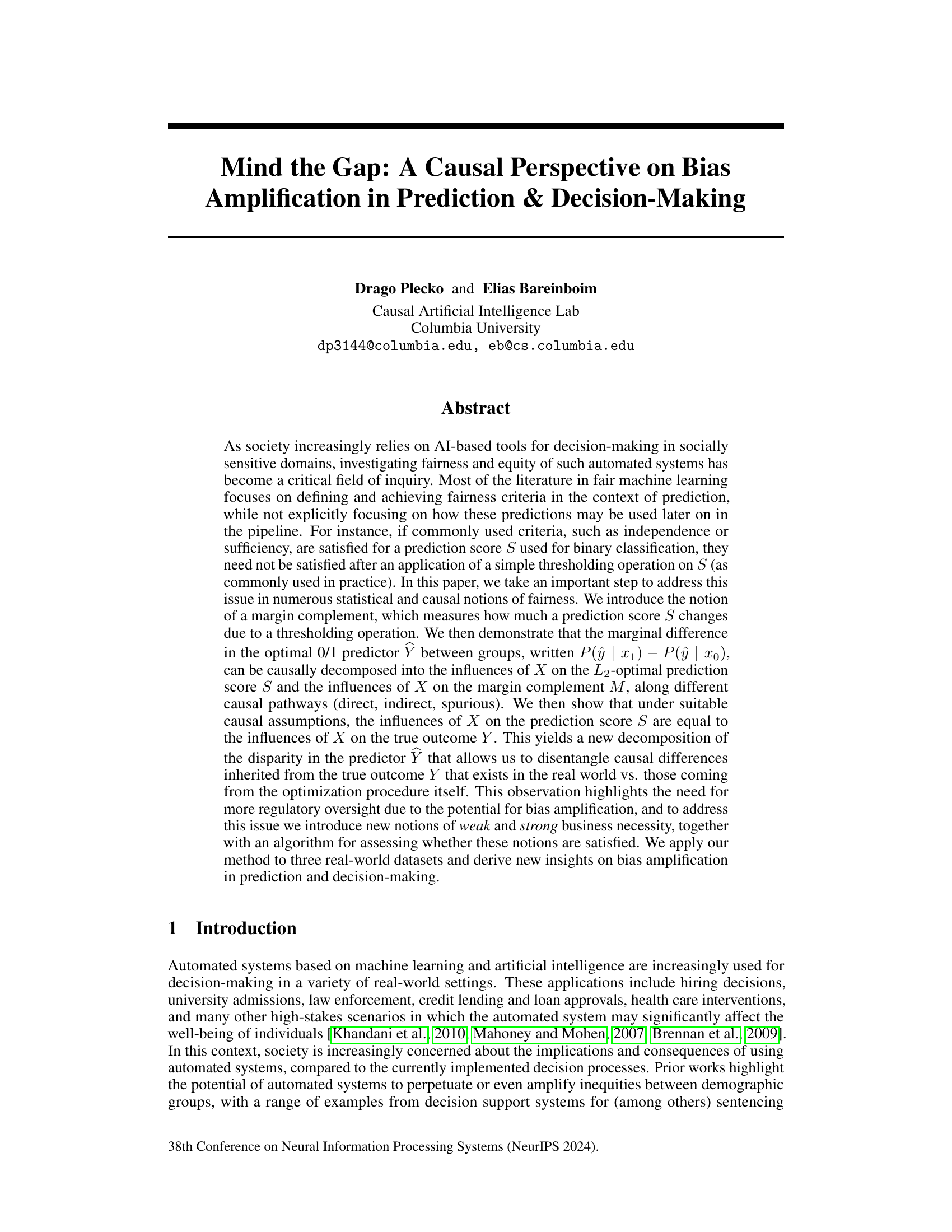

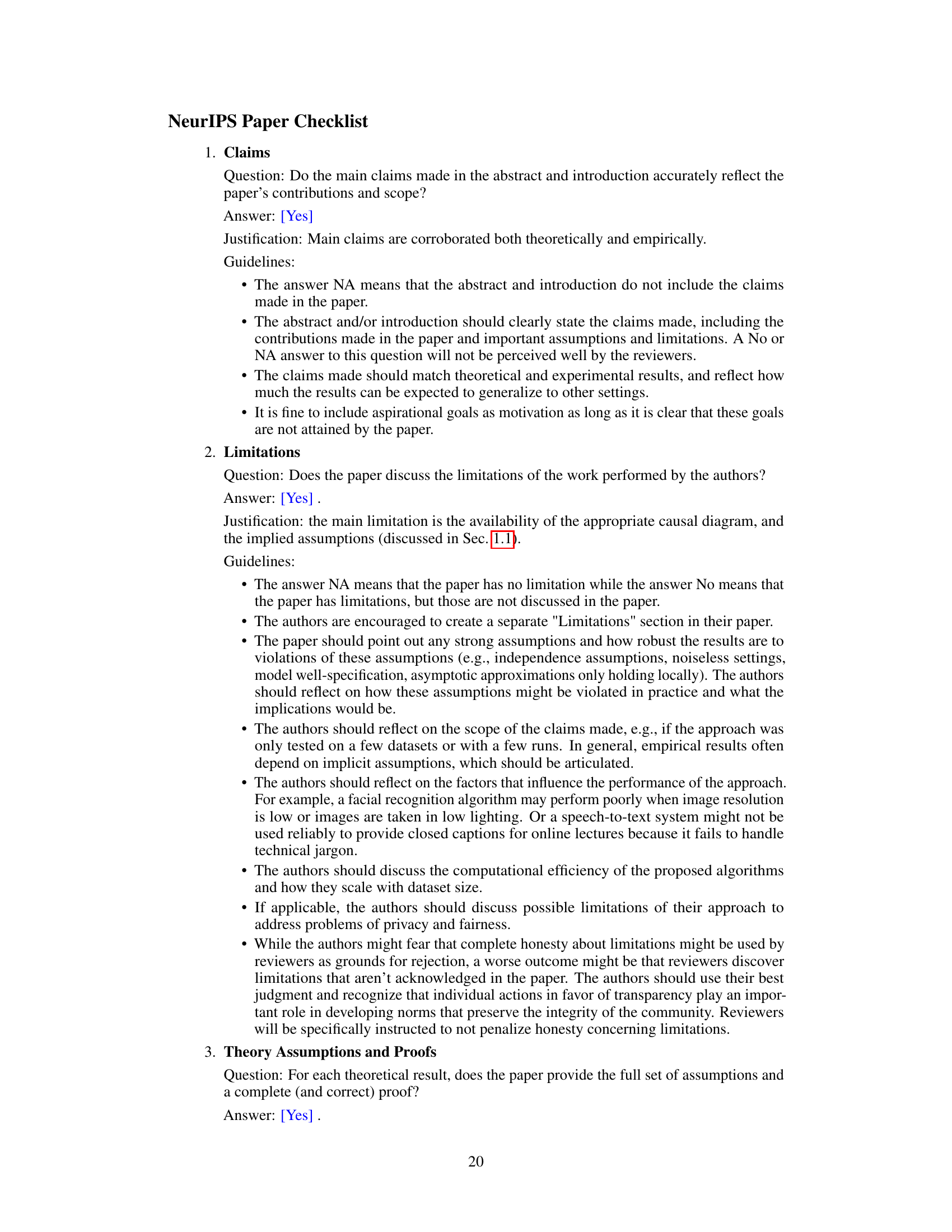

This figure visualizes the hiring disparities before and after applying a thresholding operation to the prediction scores. Before thresholding, there is a small disparity between the hiring rates of males and females. After applying the threshold (0.5 in this case), the disparity becomes much larger, with almost no females being hired compared to nearly all males. This demonstrates how a thresholding operation, which is common in binary classification, can significantly amplify the initial disparity.

In-depth insights#

Bias Amplification#

The concept of “Bias Amplification” in AI decision-making systems is critically important. It highlights how seemingly fair prediction models, satisfying standard fairness criteria like independence or sufficiency, can, after simple thresholding operations (like converting a probability score to a binary decision), exacerbate existing biases. This amplification occurs because the thresholding step interacts differently with the prediction scores of various demographic groups, leading to disproportionate outcomes. Causal analysis provides a powerful lens to decompose the bias, distinguishing between the bias inherent in the real-world data and that introduced by the prediction and decision process. Identifying causal pathways is crucial because interventions at different points can yield varying impacts. The introduction of “margin complement” helps quantify this amplification effect. This framework also introduces crucial notions of “weak” and “strong business necessity”, providing a more nuanced approach to determine when bias is justified and highlighting the need for regulatory oversight to prevent unfair algorithmic decision-making.

Causal Fairness#

Causal fairness tackles the limitations of traditional fairness metrics by explicitly considering causal relationships within data. It moves beyond simple statistical associations to identify and address the root causes of disparities. Instead of merely focusing on the correlation between protected attributes (e.g., race, gender) and outcomes, causal fairness analyzes the causal pathways leading to unequal outcomes. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of fairness, distinguishing between disparities that arise from legitimate factors and those that stem from biases. A key advantage of causal fairness is its ability to disentangle direct and indirect effects, enabling interventions targeted at specific causal mechanisms rather than merely mitigating superficial correlations. However, causal fairness also introduces challenges, such as the need for strong causal assumptions and the difficulty in identifying and quantifying causal effects in complex systems. Despite these challenges, causal fairness offers a more robust and impactful framework for achieving true fairness in AI. It promotes transparency and accountability, empowering researchers to design and deploy AI systems that are not only statistically fair but also causally just.

Marginal Effects#

Marginal effects, in the context of a causal analysis of bias amplification in prediction and decision-making, offer a powerful lens to understand how biases are transmitted and potentially exacerbated throughout a prediction pipeline. They provide a crucial decomposition of the overall disparity between groups, not simply focusing on the initial predictions but also accounting for any changes introduced by subsequent thresholding or decision-making processes. This decomposition allows for a more nuanced understanding of the origins of bias, distinguishing between bias inherited from the real-world outcome and bias generated by algorithmic steps. It’s particularly valuable for identifying scenarios where a seemingly small initial disparity is dramatically amplified by later stages. This granular analysis facilitates a more effective approach to bias mitigation, targeting specific stages or causal pathways rather than relying on broad-brush fairness criteria that may overlook critical subtleties. Furthermore, analyzing marginal effects allows us to understand how interventions at various points in the pipeline can impact the overall fairness of the system.

Business Necessity#

The concept of “Business Necessity” in the context of algorithmic fairness is crucial for addressing the tension between fairness and potentially discriminatory outcomes. It acknowledges that certain attributes, even if correlated with protected characteristics, may be legitimately used in decision-making if they serve a crucial business purpose. This is particularly relevant when automated systems amplify existing disparities. The paper proposes a nuanced framework by differentiating between “weak” and “strong” business necessity. Weak necessity demands that any disparity observed stems solely from the true outcome, not from the algorithm’s optimization procedure. Conversely, strong necessity permits the amplification of disparities if justified by a vital business objective. The approach involves decomposing the disparity in predictions into components attributable to the true outcome and the algorithm, allowing for a more targeted and equitable evaluation of business necessities in algorithmic decision-making. This framework offers a more granular approach than traditional notions of fairness, striking a balance between mitigating bias and enabling legitimate business practices.

Real-world Datasets#

The utilization of real-world datasets is critical for validating the claims and practical implications of the proposed methodology in addressing bias amplification. The selection of diverse datasets, spanning various domains such as healthcare, criminal justice, and demographics, demonstrates a commitment to generalizability. Analyzing these datasets through the lens of causal fairness allows for a deeper understanding of bias propagation mechanisms. The results obtained should ideally showcase how the proposed techniques effectively disentangle inherent biases in the data from those amplified by the prediction process. Methodological transparency in data pre-processing and variable selection is crucial for reproducibility and assessing the validity of the obtained insights. Furthermore, it is important to consider how the identified bias amplification patterns might inform the design of fairer AI systems and policies. Careful consideration should be given to potential ethical implications when using sensitive real-world data, encompassing issues of privacy, fairness, and equitable access to technology. The findings derived from real-world data analyses should contribute to a more nuanced and effective approach in mitigating bias in AI, furthering the goal of fairness and equity in socially sensitive contexts.

More visual insights#

More on figures

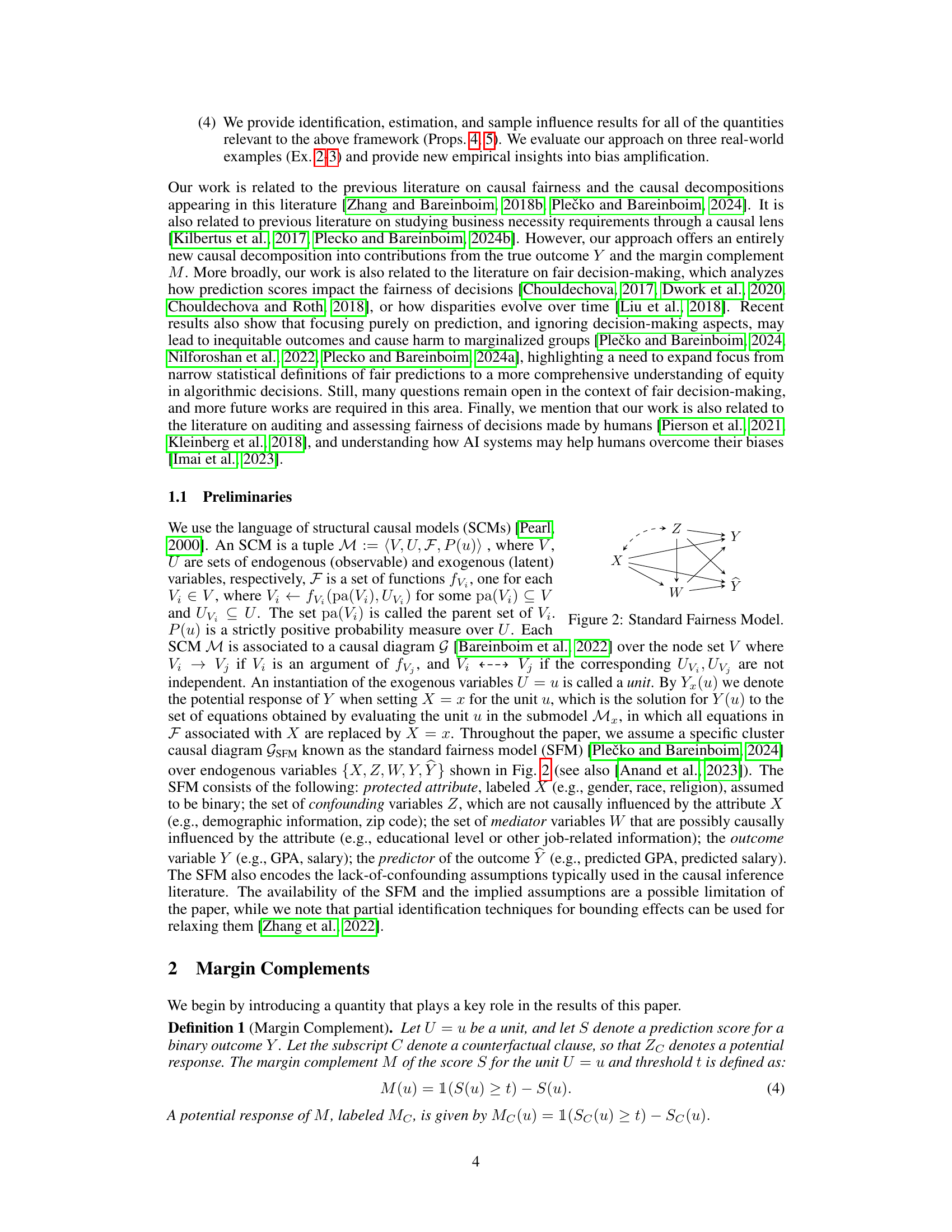

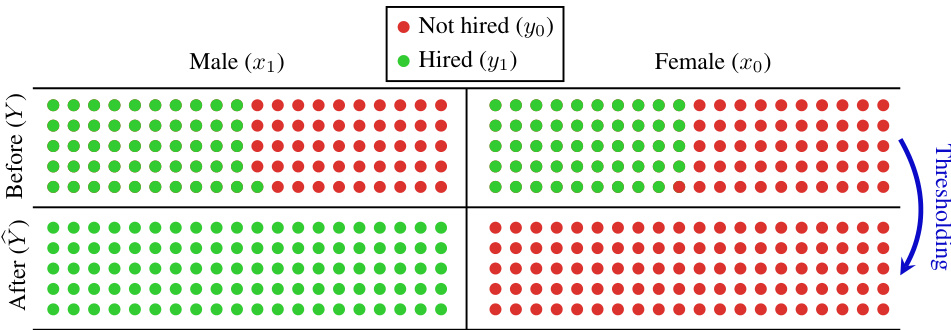

This figure shows a causal diagram representing the standard fairness model (SFM). The model includes nodes for the protected attribute (X), confounders (Z), mediators (W), outcome (Y), and prediction (Ŷ). The arrows indicate causal relationships between these variables. This model is a common framework used for analyzing fairness in machine learning algorithms and understanding how biases might propagate through different stages of the prediction pipeline.

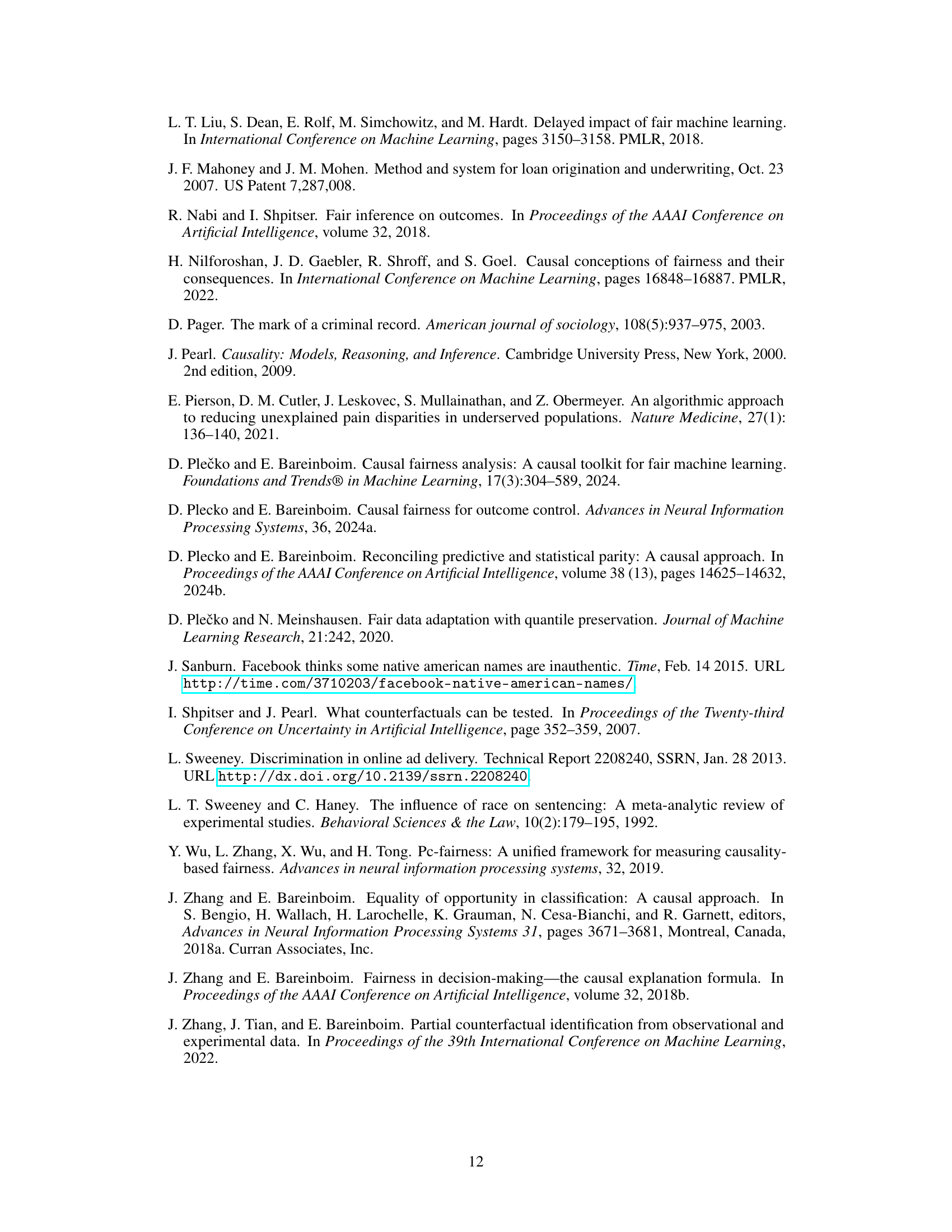

This figure shows the causal decomposition of the disparity in the optimal 0/1 predictor for the MIMIC-IV dataset, which is based on Corollary 3 of the paper. The left panel (a) presents the decomposition of the total variation (TV) into direct, indirect, and spurious effects, broken down further into the contributions from the true outcome Y and the margin complement M. The right panel (b) displays the sample influences for the direct effect, showing the contribution of each individual sample to the overall disparity. This allows for identification of influential samples and potential subgroups that disproportionately drive the disparities.

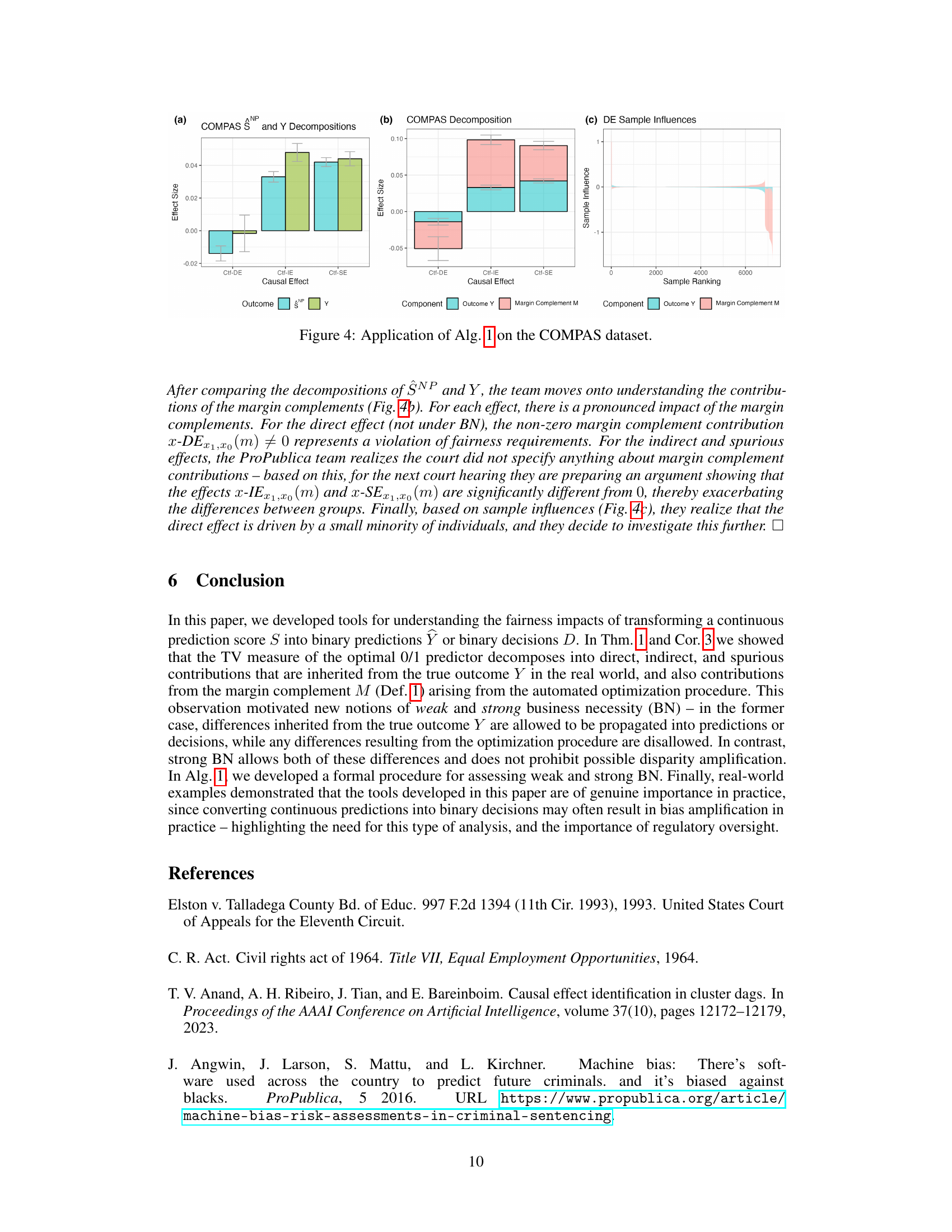

This figure shows the application of Algorithm 1 (Auditing Weak & Strong Business Necessity) on the COMPAS dataset. It consists of three subfigures: (a) compares the decompositions of the true outcome Y and the predictor ŜNP (from the Northpointe algorithm). (b) shows the decompositions for each causal effect (direct, indirect, spurious) into the contributions from the optimal predictor ŜNP and the margin complement M. (c) presents the sample influences for the direct effect. The results highlight the importance of understanding bias amplification through causal pathways and the margin complement.

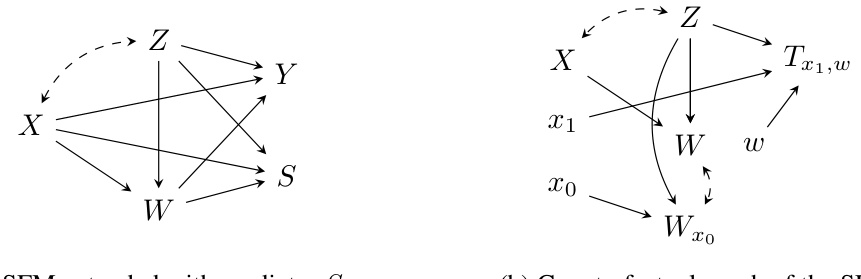

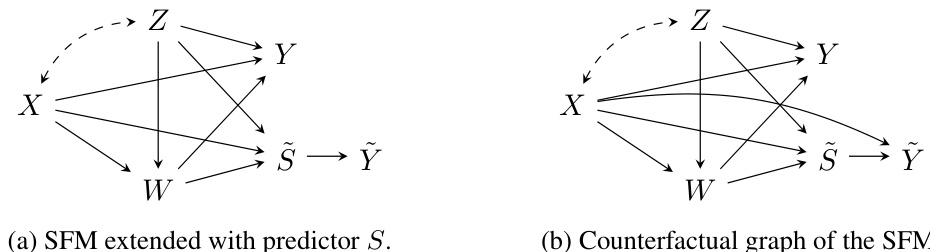

This figure shows two graphs used to prove Theorem 2 and Proposition 4 of the paper. The graph (a) is the standard fairness model (SFM) extended with a predictor S. The graph (b) shows the counterfactual graph for the SFM. Both graphs illustrate the relationships between variables in the causal model and their role in proving the stated theorems. These theorems deal with the causal decomposition of the optimal 0/1 predictor and its relationship with the true outcome Y.

This figure shows the results of applying the causal decomposition from Corollary 3 to the MIMIC-IV dataset. Panel (a) presents a bar chart showing the decomposition of the total variation (TV) measure, which quantifies the disparity between groups in the outcome. The TV is broken down into contributions from three causal pathways: direct effects, indirect effects, and spurious effects. Each causal effect is further decomposed into contributions from the true outcome Y and the margin complement M, which quantifies how much a prediction score changes due to thresholding. Panel (b) shows the sample influences on the direct effects, which helps identify influential samples for further investigation.

This figure shows the causal decomposition of the disparity in the optimal 0/1 predictor for the MIMIC-IV dataset, based on Corollary 3. Panel (a) displays the decomposition into direct, indirect, and spurious effects, showing the contributions of the true outcome (Y) and the margin complement (M). Panel (b) presents the sample influence analysis for the direct effect, illustrating how individual samples contribute to the overall disparity and highlighting potentially influential subpopulations.

The figure shows two causal diagrams. (a) shows the standard fairness model (SFM) extended with the predictor S, where S is the optimal L2 prediction score. (b) is the counterfactual graph of the SFM, used to prove the identifiability of the potential outcomes involved in the theorems. These diagrams are crucial for the proofs of Theorem 2 and Proposition 4, which demonstrate the relationship between the causal decomposition of the score S and the true outcome Y, and the identifiability of causal measures from observational data.

Full paper#