TL;DR#

This research explores the connection between artificial intelligence (AI) and human cognition by examining the surprising parallels between transformer models and human episodic memory. Many AI models are inspired by neuroscience; however, the relationship between transformers (a powerful AI architecture) and human memory has been largely unexplored. The paper focuses on “induction heads” – a particular type of attention head in transformer models that’s critical for in-context learning (ICL), the ability of AI models to perform tasks without explicit training. The authors hypothesize that these induction heads may function similarly to the human brain’s contextual maintenance and retrieval (CMR) model of episodic memory.

The study compares the behavioral and mechanistic properties of induction heads and the CMR model. Using both quantitative and qualitative analyses, the researchers find striking similarities between induction heads and the CMR model. The ablation of CMR-like heads also suggests their causal role in in-context learning. The findings highlight the significant functional and mechanistic overlap between LLMs and human memory, potentially leading to new insights into both artificial and biological intelligence.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it bridges the gap between artificial intelligence and neuroscience by revealing a surprising parallel between transformer models and human episodic memory. This has implications for developing more human-like AI, improving the interpretability of LLMs, and offering insights into the cognitive mechanisms underlying human memory. Understanding how these mechanisms function in both artificial and biological systems is crucial for advancing both research fields.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the tasks and model architectures used in the study. Panel (a) shows the next-token prediction task used to evaluate the in-context learning (ICL) of pre-trained large language models (LLMs). Panel (b) depicts the human memory recall task, where subjects memorize a sequence of words and then recall them in any order. Panel (c) presents a simplified Transformer architecture, highlighting the residual stream and the interaction of attention heads. Finally, panel (d) displays the contextual maintenance and retrieval (CMR) model of human episodic memory.

read the caption

Figure 1: Tasks and model architectures. (a) Next-token prediction task. The ICL of pre-trained LLMs is evaluated on a sequence of repeated random tokens ('...[A][B][C][D]...[A][B][C][D]...'; e.g., [A]=light, [B]=cat, [C]=table, [D]=water) by predicting the next token (e.g., '...[A][B][C][D]...[B]'→?). (b) Human memory recall task. During the study phase, the subject is sequentially presented with a list of words to memorize. During the recall phase, the subject is required to recall the studied words in any order. (c) Transformer architecture, centering on the residual stream. The blue path is the residual stream of the current token, and the grey path represents the residual stream of a past token. H1 and H2 are attention heads. MLP is the multilayer perceptron. (d) Contextual maintenance and retrieval model. The word vector f is retrieved from the context vector t via MTF and the context vector is updated by the word vector via MFT (see main text for details).

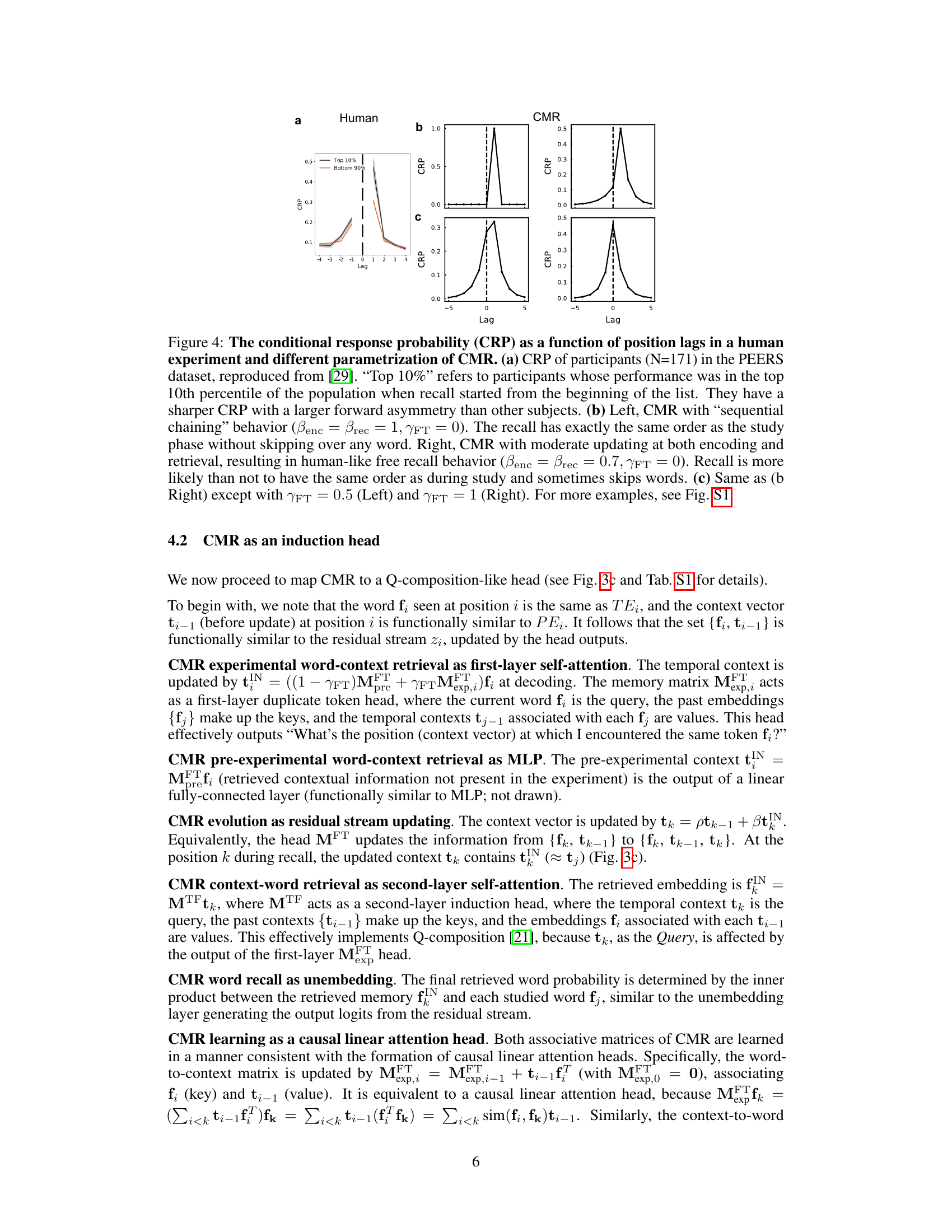

🔼 This table compares the mechanisms of three types of attention heads (K-composition, Q-composition, and CMR) in Transformer models. It details the representation in the residual stream before and after the first and second layer attention heads, specifying the query, key, optimal match conditions, activation functions, and value and output for each layer of each attention head type. It highlights the similarities and differences in how information is processed and how the outputs contribute to the residual stream.

read the caption

Table S1: Comparison of mechanisms of induction heads and CMR.

In-depth insights#

Transformer Memory#

The concept of “Transformer Memory” is fascinating, exploring how the architecture of transformers, particularly the self-attention mechanism, might relate to memory processes in biological systems. The key question is how the sequential processing and context-dependent nature of transformers could be leveraged to model human-like memory, including both short-term and long-term memory. One approach focuses on identifying specific attention heads within the transformer network that exhibit behavior analogous to memory retrieval and maintenance. These “memory heads” might selectively attend to relevant past information, mimicking the targeted recall observed in biological memory. Another line of inquiry investigates how the transformer’s internal representations evolve over time, potentially reflecting the dynamic updating of memories as new information is integrated. Understanding how these mechanisms interact is crucial to building more sophisticated AI systems capable of retaining and utilizing past experiences. Ultimately, a deep investigation of “Transformer Memory” has the potential to reveal fundamental insights into both the workings of biological memory and the development of advanced AI models.

CMR-like Attention#

The concept of ‘CMR-like attention’ in the context of Transformer models offers a fascinating bridge between artificial intelligence and human cognition. CMR (Contextual Maintenance and Retrieval), a model of human episodic memory, emphasizes the role of a dynamic contextual representation in retrieving information. The authors’ research proposes that certain attention heads in Transformers, termed ‘CMR-like,’ mimic this behavior. These heads exhibit attention patterns strikingly similar to human memory biases, such as temporal contiguity and forward asymmetry, suggesting a computational mechanism shared by both. This parallel extends to their functional role in in-context learning, as ablation studies suggest that CMR-like heads causally contribute to the model’s ability to perform new tasks based on limited contextual information. The emergence of CMR-like behavior during model training provides further evidence of this parallel, showing a gradual refinement of attention patterns that mirror human learning processes. These findings offer valuable insights, not only into improving the interpretability and functionality of LLMs but also into uncovering deeper principles underlying human episodic memory.

ICL Mechanism#

The paper investigates the in-context learning (ICL) mechanism in transformer models, focusing on the role of induction heads. These heads, crucial for ICL’s ability to perform new tasks based solely on input context, are behaviorally and functionally analogous to the human episodic memory’s contextual maintenance and retrieval (CMR) model. The authors demonstrate mechanistic similarities between induction heads and CMR through analyzing attention patterns, highlighting a match-then-copy behavior in induction heads mirroring CMR’s associative retrieval. The analysis reveals a qualitative parallel between LLMs and human memory biases as CMR-like heads tend to emerge in intermediate and late layers of the model. Importantly, ablating these heads suggests a causal role in ICL, solidifying the connection between the computational mechanisms of LLMs and human memory.

Model Limitations#

This research demonstrates a novel connection between transformer models and human episodic memory, but several model limitations exist. The study primarily focuses on smaller transformer models, and it remains unclear how the findings generalize to larger, more complex LLMs. The analysis of attention heads is based on a specific definition of ‘induction heads,’ and it is possible other types of heads contribute to in-context learning or exhibit CMR-like behavior. The experiments rely on specific datasets and evaluation tasks; the results’ generalizability to other domains or scenarios needs further investigation. The causal link between CMR-like heads and in-context learning is not definitively established, despite ablation study results suggesting a correlation. Future research should address these limitations to build a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between LLMs and human memory.

Future Research#

Future research should focus on extending the CMR model to encompass more complex memory phenomena, such as interference effects, and on investigating the interactions between episodic memory and other cognitive functions within LLMs. It is crucial to develop more sophisticated metrics for characterizing induction heads beyond simple matching scores, enabling a deeper understanding of their internal mechanisms. Furthermore, research should explore the causal relationship between CMR-like heads and ICL more rigorously, addressing potential confounding factors like Hydra effects and distributional shifts in training data. Finally, investigating the biological plausibility of CMR in neural circuits, including hippocampal subregions and their interactions with cortical areas, is essential to bridge artificial and biological intelligence.

More visual insights#

More on figures

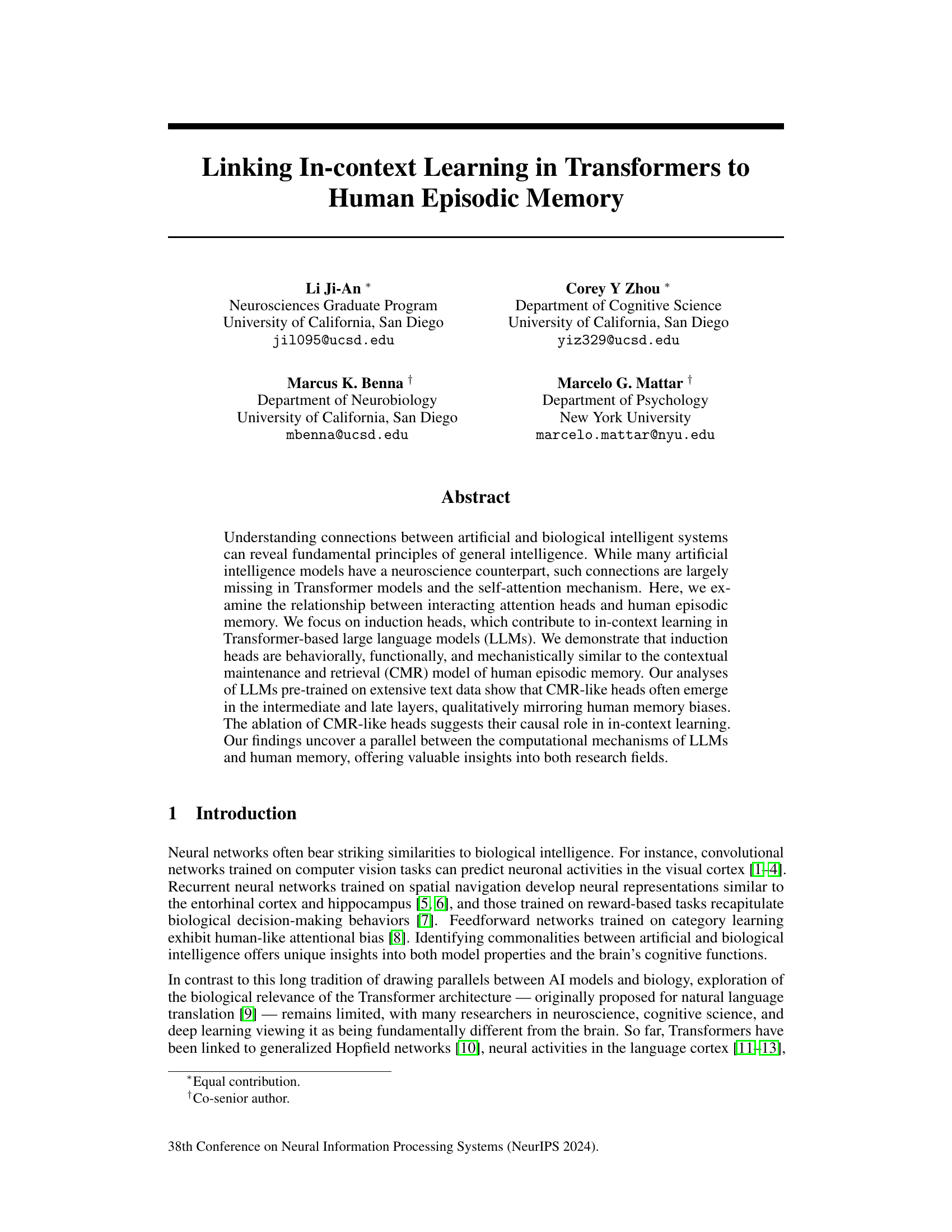

🔼 This figure shows the characteristics of induction heads in the GPT2-small model. Panel (a) shows the induction head matching score for each head across all layers, revealing that several heads exhibit relatively high scores. Panel (b) visualizes the attention pattern of the L5H1 head, highlighting a strong ‘induction stripe’ pattern indicative of its match-then-copy behavior. Panel (c) presents the average attention score as a function of the relative position lag, mirroring the Conditional Response Probability (CRP) analysis used in human memory studies.

read the caption

Figure 2: Induction heads in the GPT2-small model. (a) Several heads in GPT2 have a relatively large induction-head matching score. (b) The attention pattern of the L5H1 head, which has the largest induction-head matching score. The diagonal line ('induction stripe') shows the attention from the destination token in the second repeat to the source token in the first repeat. (c) The attention scores of the L5H1 head averaged over all tokens in the designed prompt as a function of the relative position lag (similar to CRP). Error bars show the SEM across tokens.

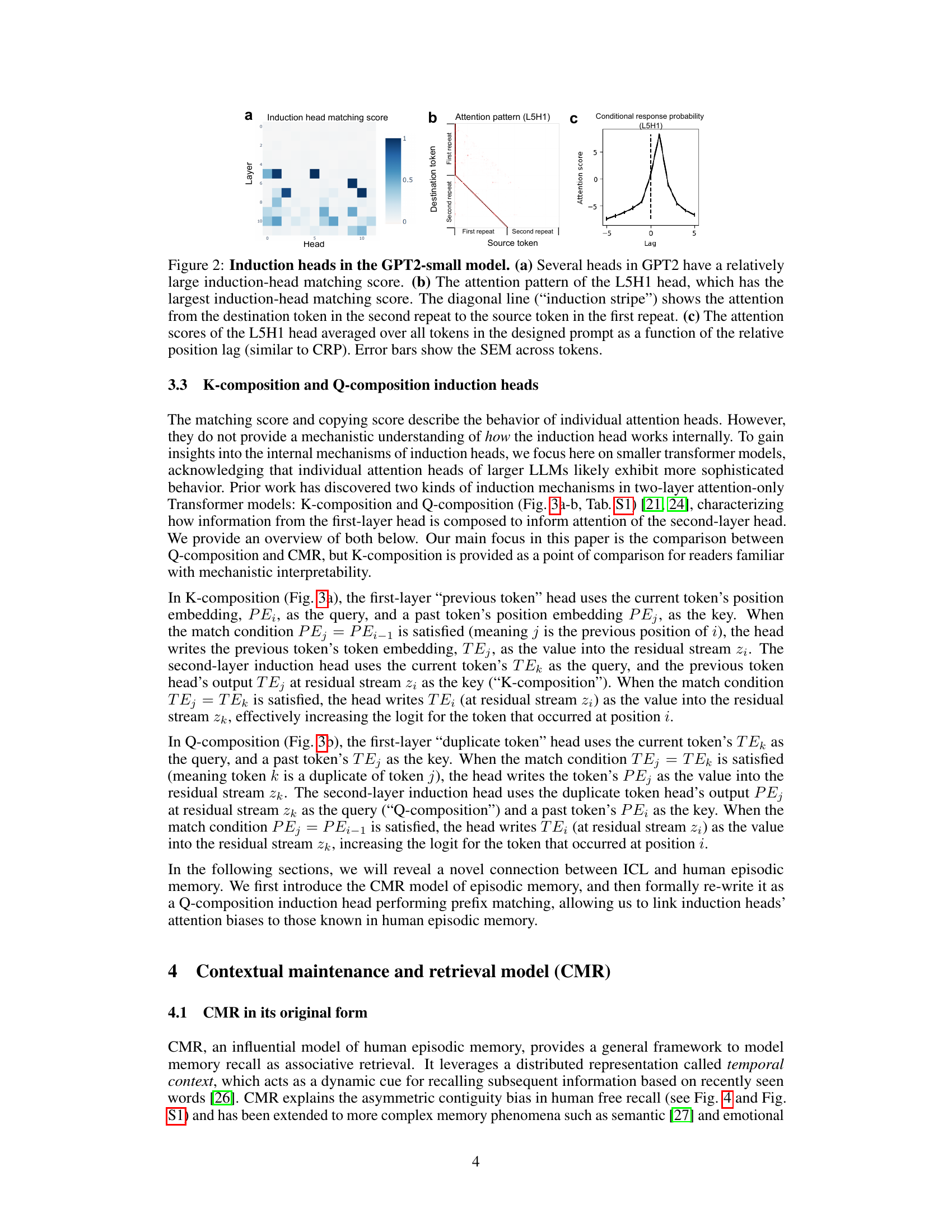

🔼 This figure compares the composition mechanisms of K-composition, Q-composition induction heads, and the CMR model. It illustrates how information flows between layers in each model and highlights their similarities and differences, especially concerning the use of previous tokens’ information to predict the next token. The CMR model is shown to be analogous to a Q-composition head but with a unique contextual update mechanism.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of composition mechanisms of induction heads and CMR. All panels correspond to the optimal Q-K match condition (j = i − 1). See the main text and Tab. S1 for details. (a) K-composition induction head. The first-layer head's output serves as the Key of the second-layer head. (b) Q-composition induction head. The first-layer head's output serves as the Query of the second-layer head. (c) CMR is similar to a Q-composition induction head, except that the context vector tj-1 is first updated by MFT into ti at position j, then directly used at position j + 1 (equal to i for the optimal match condition; shown by red lines).

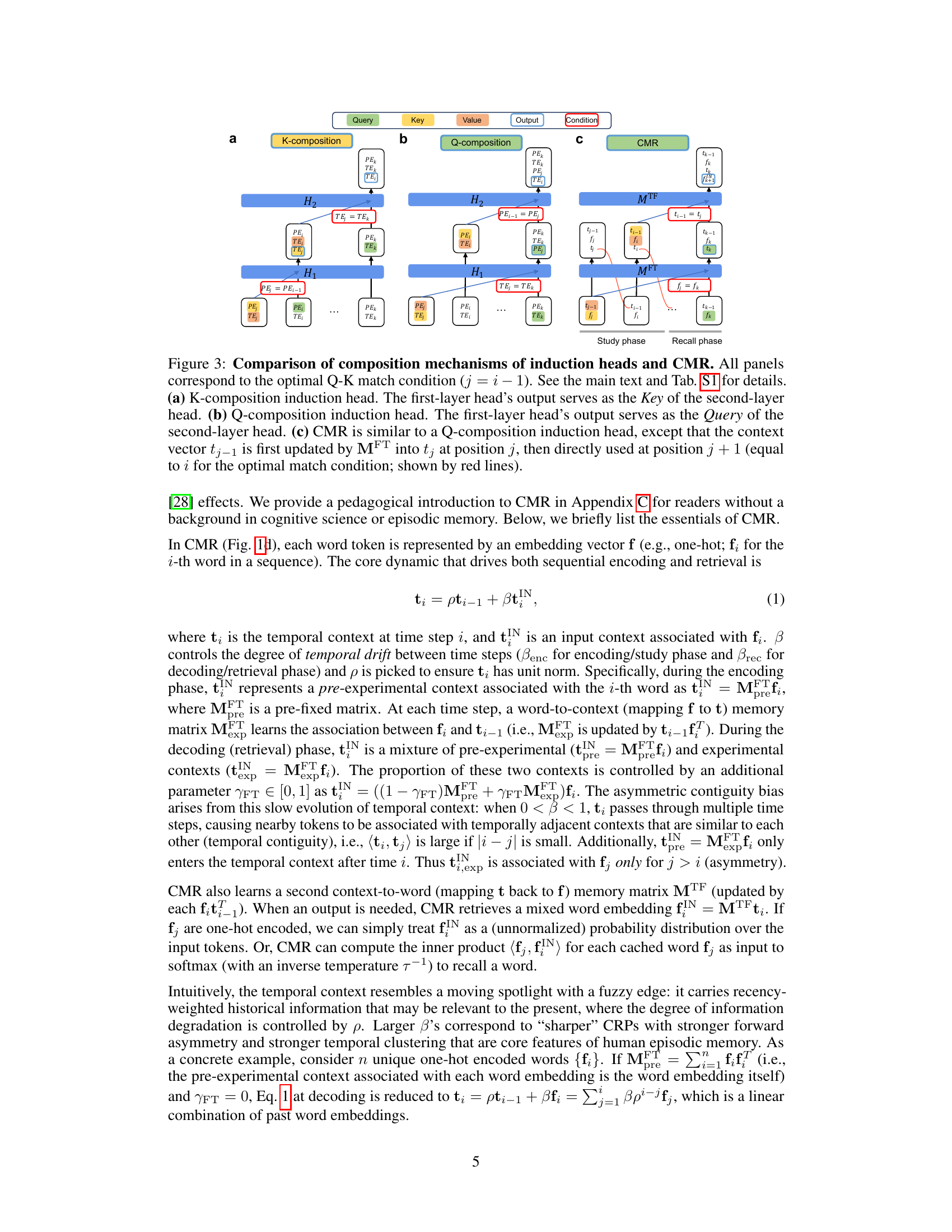

🔼 This figure compares the conditional response probability (CRP) – a measure of the likelihood of recalling a word given the previously recalled word’s position – in humans and in the CMR model. Panel (a) shows human data, distinguishing between high and low performing participants. Panels (b) and (c) illustrate CMR’s CRP under different parameter settings, demonstrating its ability to reproduce human-like recall patterns (asymmetry and temporal contiguity).

read the caption

Figure 4: The conditional response probability (CRP) as a function of position lags in a human experiment and different parametrization of CMR. (a) CRP of participants (N=171) in the PEERS dataset, reproduced from [29]. “Top 10%” refers to participants whose performance was in the top 10th percentile of the population when recall started from the beginning of the list. They have a sharper CRP with a larger forward asymmetry than other subjects. (b) Left, CMR with “sequential chaining” behavior (Benc = Brec = 1, YFT = 0). The recall has exactly the same order as the study phase without skipping over any word. Right, CMR with moderate updating at both encoding and retrieval, resulting in human-like free recall behavior (Benc = ẞrec = 0.7, FT = 0). Recall is more likely than not to have the same order as during study and sometimes skips words. (c) Same as (b Right) except with FT = 0.5 (Left) and YFT = 1 (Right). For more examples, see Fig. S1.

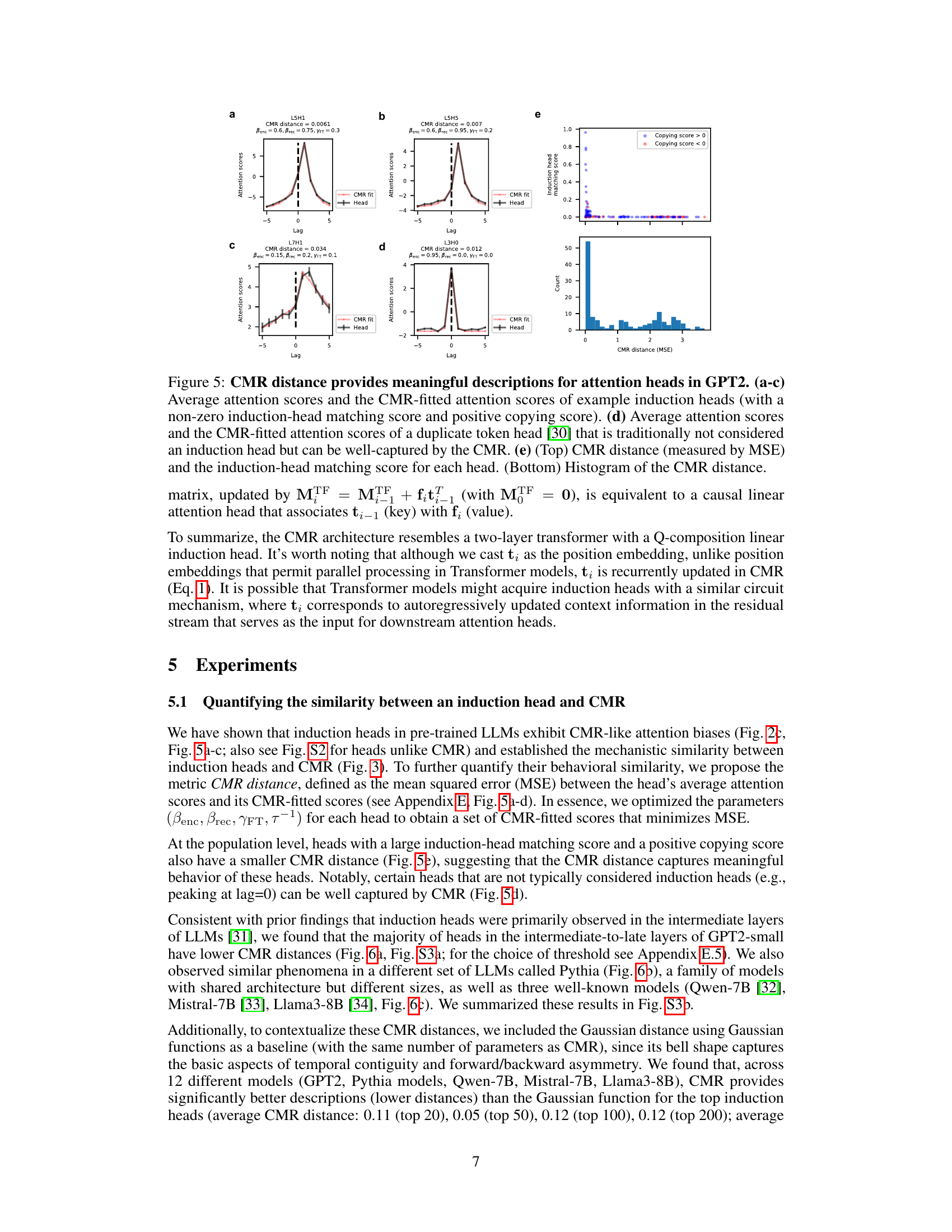

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the CMR distance metric in characterizing the behavior of attention heads in the GPT2 language model. Panels (a)-(c) and (d) show the average attention scores of several induction heads (heads that exhibit match-then-copy behavior) and a duplicate token head, respectively, along with their corresponding CMR fits. The CMR fit is obtained by adjusting CMR parameters to minimize the mean squared error between the model’s average attention scores and the predicted scores. The CMR distance, which is the MSE between the actual and fitted scores, provides a quantitative measure of the similarity between attention heads and the CMR model. Panel (e) shows the relationship between CMR distance and induction head matching score, as well as a histogram of the CMR distances for all heads in the model. The results indicate that heads with high induction-head matching scores and positive copying scores tend to have low CMR distances, suggesting that these heads exhibit CMR-like behavior.

read the caption

Figure 5: CMR distance provides meaningful descriptions for attention heads in GPT2. (a-c) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of example induction heads (with a non-zero induction-head matching score and positive copying score). (d) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of a duplicate token head [30] that is traditionally not considered an induction head but can be well-captured by the CMR. (e) (Top) CMR distance (measured by MSE) and the induction-head matching score for each head. (Bottom) Histogram of the CMR distance.

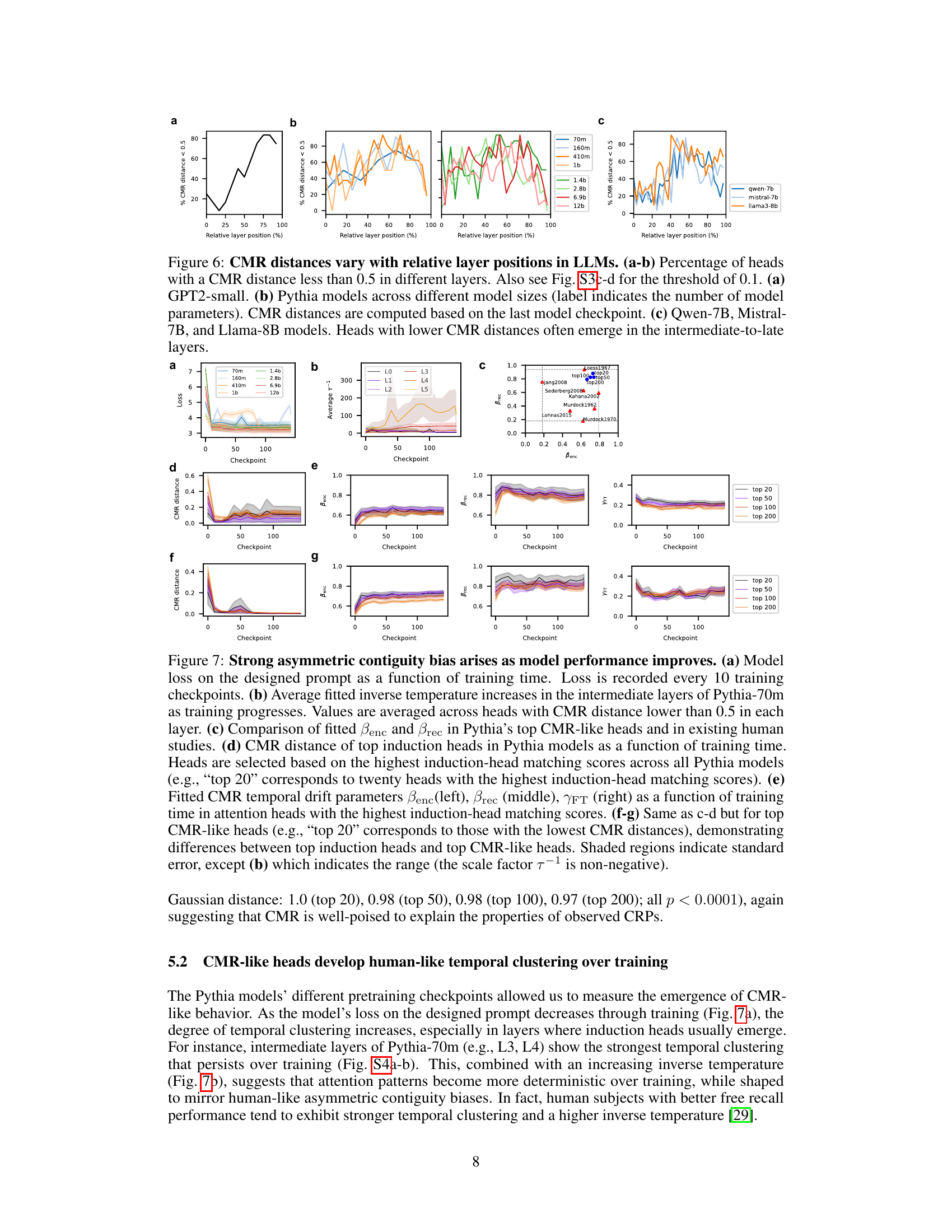

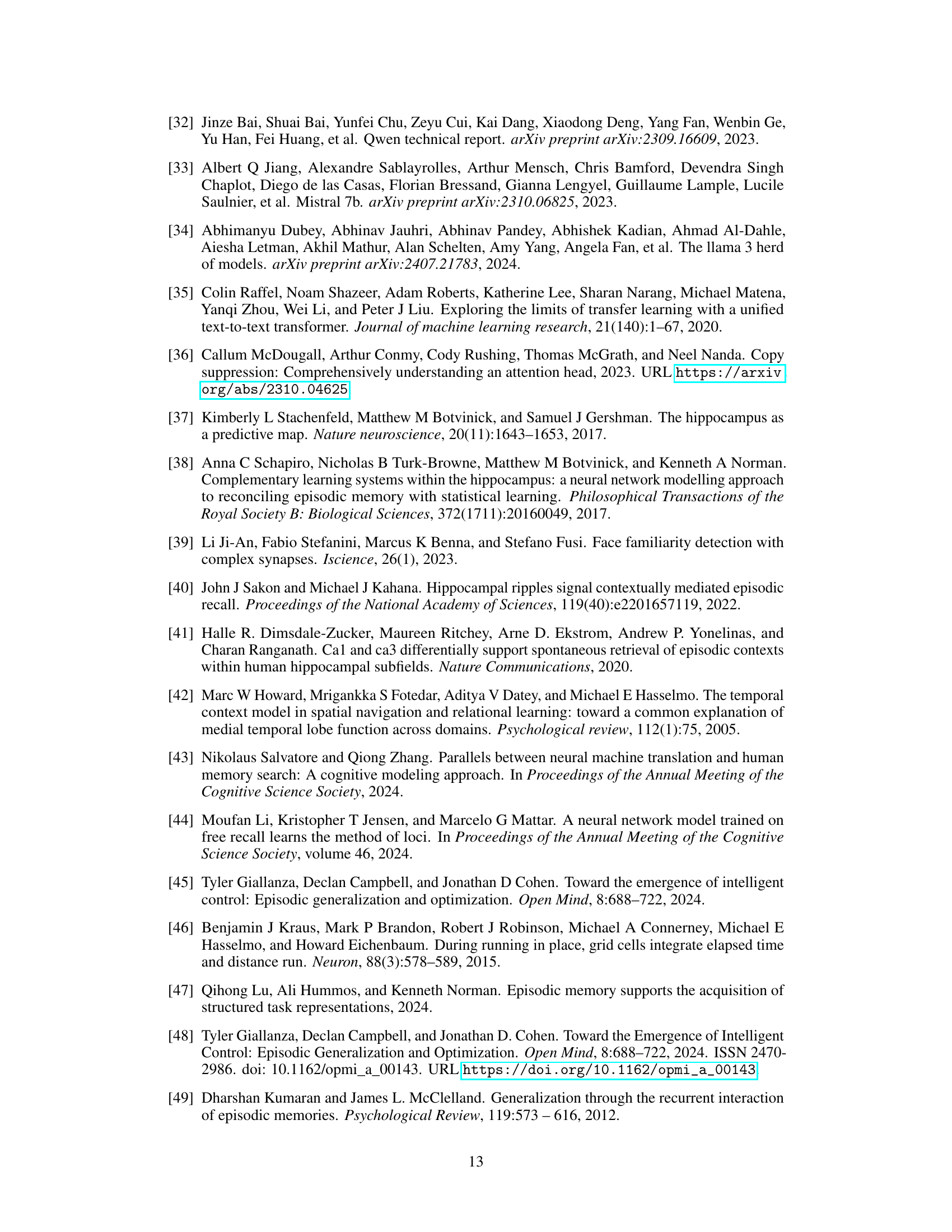

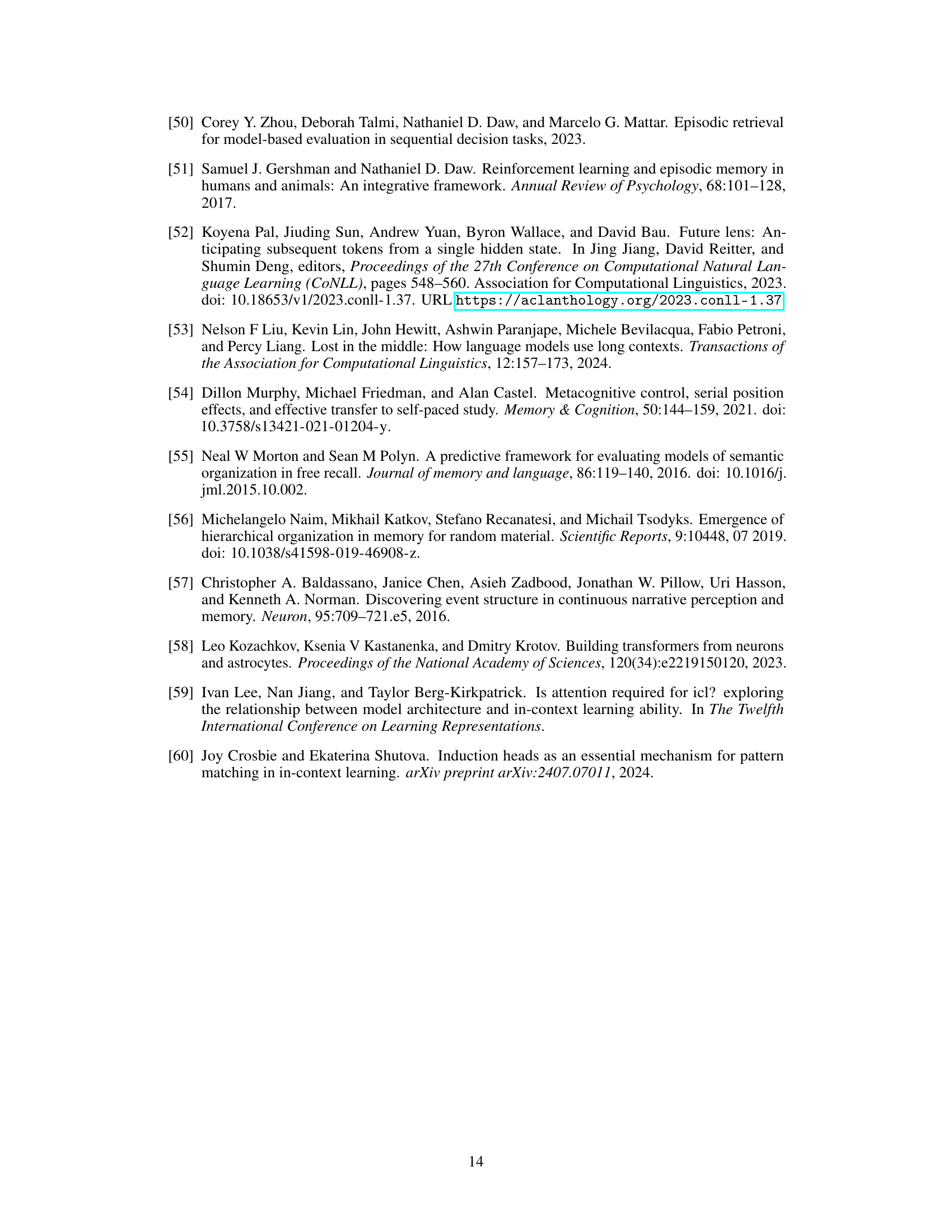

🔼 This figure demonstrates the relationship between the layer position in LLMs and the prevalence of heads exhibiting CMR-like behavior. It shows that in various LLMs (GPT2-small, Pythia models of varying sizes, and Qwen-7B, Mistral-7B, and Llama-8B), heads with lower CMR distances tend to emerge more frequently in intermediate and later layers of the model architecture, suggesting a potential link between CMR-like mechanisms and the models’ processing of longer-range contextual information.

read the caption

Figure 6: CMR distances vary with relative layer positions in LLMs. (a-b) Percentage of heads with a CMR distance less than 0.5 in different layers. Also see Fig. S3c-d for the threshold of 0.1. (a) GPT2-small. (b) Pythia models across different model sizes (label indicates the number of model parameters). CMR distances are computed based on the last model checkpoint. (c) Qwen-7B, Mistral-7B, and Llama-8B models. Heads with lower CMR distances often emerge in the intermediate-to-late layers.

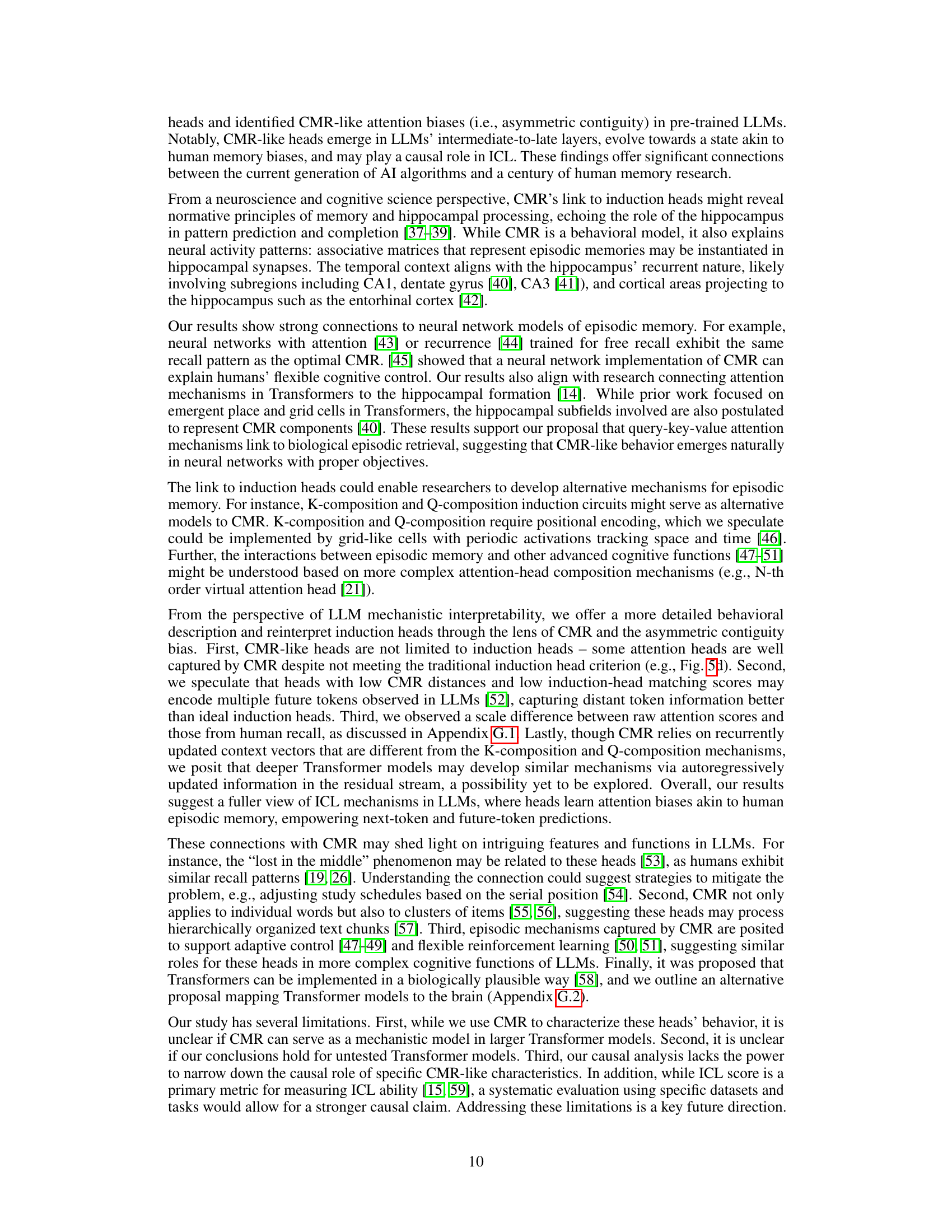

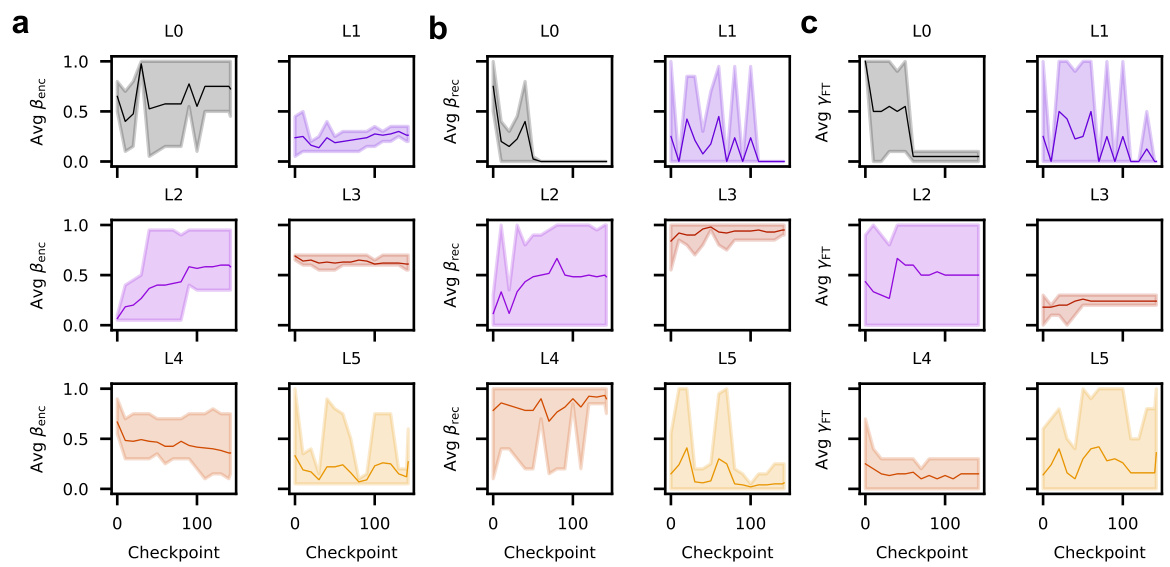

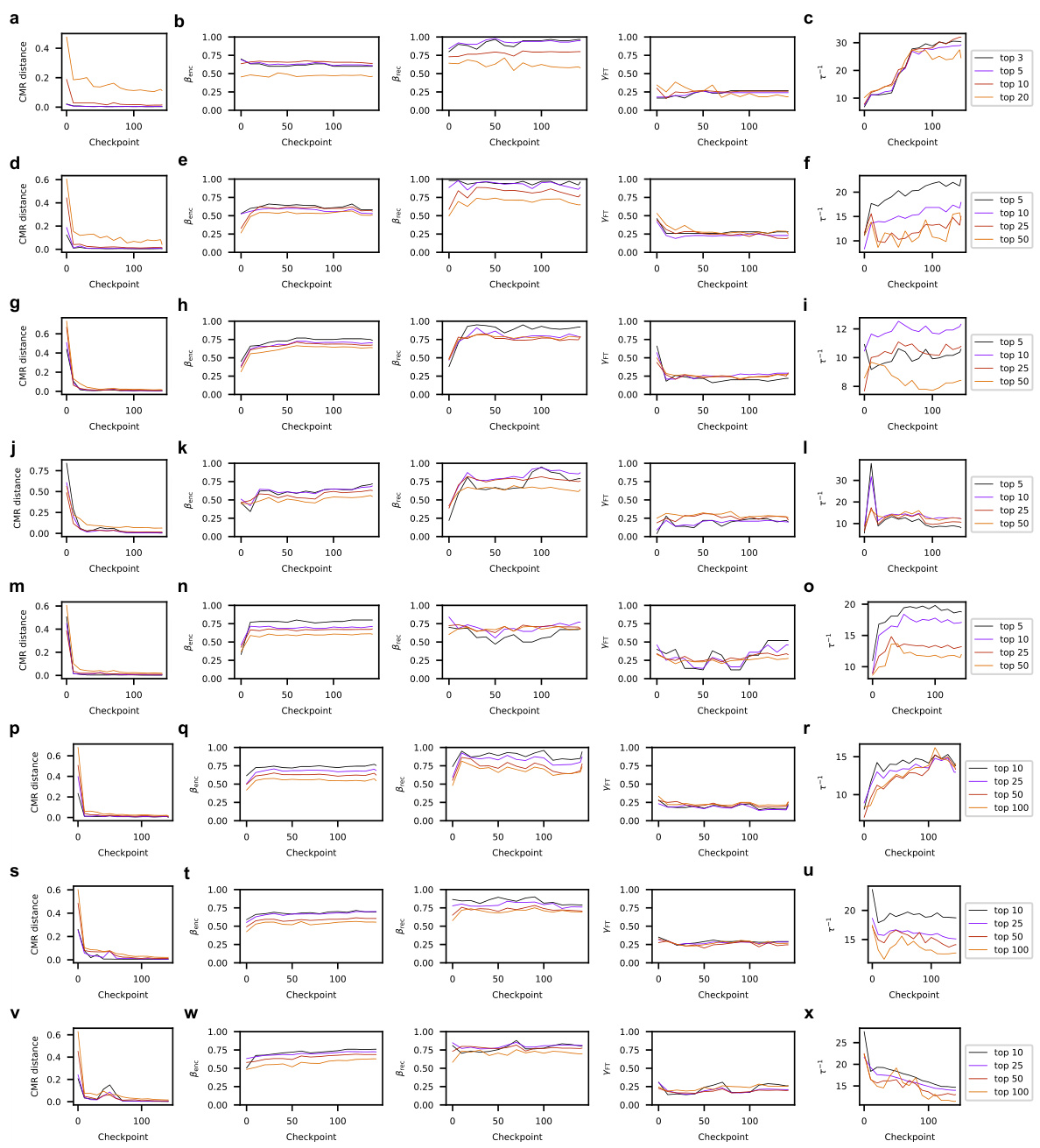

🔼 This figure displays the results of an experiment analyzing the relationship between model performance, training time, and the characteristics of CMR-like heads in Pythia models. It demonstrates that strong asymmetric contiguity biases (a characteristic of human memory) emerge as the model’s performance improves during training. The figure examines inverse temperature, CMR distance, and fitted CMR parameters (βenc, βrec, γFT) across layers and training checkpoints, highlighting the development of human-like temporal clustering over time.

read the caption

Figure 7: Strong asymmetric contiguity bias arises as model performance improves. (a) Model loss on the designed prompt as a function of training time. Loss is recorded every 10 training checkpoints. (b) Average fitted inverse temperature increases in the intermediate layers of Pythia-70m as training progresses. Values are averaged across heads with CMR distance lower than 0.5 in each layer. (c) Comparison of fitted Benc and Brec in Pythia’s top CMR-like heads and in existing human studies. (d) CMR distance of top induction heads in Pythia models as a function of training time. Heads are selected based on the highest induction-head matching scores across all Pythia models (e.g., “top 20” corresponds to twenty heads with the highest induction-head matching scores). (e) Fitted CMR temporal drift parameters Benc(left), Brec (middle), YFT (right) as a function of training time in attention heads with the highest induction-head matching scores. (f-g) Same as c-d but for top CMR-like heads (e.g., “top 20” corresponds to those with the lowest CMR distances), demonstrating differences between top induction heads and top CMR-like heads. Shaded regions indicate standard error, except (b) which indicates the range (the scale factor 7-1 is non-negative).

🔼 This figure presents the results of an ablation study investigating the causal role of CMR-like heads in in-context learning (ICL). Three groups of models are compared: original models, models with the top 10% of CMR-like heads ablated, and models with a random 10% of heads ablated. The ICL score, representing the model’s ability to perform ICL (lower scores being better), is shown for each model. Statistical significance (p-values) is indicated for the comparisons between each group.

read the caption

Figure 8: CMR-like heads are causally relevant for ICL. ICL scores are evaluated for intact models (Original), models with the top 10% CMR-like heads ablated (Top 10% ablated), and models with randomly selected heads ablated (Random ablated). Lower scores indicate better ICL abilities, with error bars showing SEM across sequences. ***: p < 0.001, **: p < 0.01, *: p < 0.05, n.s.: p ≥ 0.1.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the CMR distance metric in characterizing attention heads in the GPT-2 language model. It visually compares average attention scores of several example induction heads with their corresponding CMR-fitted scores (i.e., scores predicted by the CMR model). It shows that CMR can accurately capture the behavior of induction heads, even those not typically classified as such. Finally, it provides a quantitative assessment of this similarity by plotting CMR distance against induction-head matching scores, showing a clear correlation between lower CMR distance and a higher induction-head matching score. A histogram of CMR distances across all heads further supports the finding that many heads exhibit CMR-like behavior.

read the caption

Figure 5: CMR distance provides meaningful descriptions for attention heads in GPT2. (a-c) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of example induction heads (with a non-zero induction-head matching score and positive copying score). (d) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of a duplicate token head [30] that is traditionally not considered an induction head but can be well-captured by the CMR. (e) (Top) CMR distance (measured by MSE) and the induction-head matching score for each head. (Bottom) Histogram of the CMR distance.

🔼 This figure shows that the CMR distance metric effectively captures the behavior of attention heads in GPT2. Panels (a-c) compare the average attention scores of example induction heads with their CMR-fitted scores, demonstrating a close match. Panel (d) shows that even a duplicate token head, typically not considered an induction head, can be well-described by the CMR. Panel (e) demonstrates a strong correlation between CMR distance and induction head matching score, further highlighting the effectiveness of the CMR distance in characterizing attention head behavior. The histogram in (e) shows the distribution of CMR distances across all heads.

read the caption

Figure 5: CMR distance provides meaningful descriptions for attention heads in GPT2. (a-c) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of example induction heads (with a non-zero induction-head matching score and positive copying score). (d) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of a duplicate token head [30] that is traditionally not considered an induction head but can be well-captured by the CMR. (e) (Top) CMR distance (measured by MSE) and the induction-head matching score for each head. (Bottom) Histogram of the CMR distance.

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of CMR distances across different layers of various LLMs. It demonstrates that a greater percentage of heads with low CMR distances are present in the intermediate and later layers of the models (GPT2-small, Pythia models with various sizes, Qwen-7B, Mistral-7B, and Llama-8B). This suggests that the CMR-like behavior of attention heads is more prevalent in these layers.

read the caption

Figure 6: CMR distances vary with relative layer positions in LLMs. (a-b) Percentage of heads with a CMR distance less than 0.5 in different layers. Also see Fig. S3c-d for the threshold of 0.1. (a) GPT2-small. (b) Pythia models across different model sizes (label indicates the number of model parameters). CMR distances are computed based on the last model checkpoint. (c) Qwen-7B, Mistral-7B, and Llama-8B models. Heads with lower CMR distances often emerge in the intermediate-to-late layers.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the CMR distance metric in characterizing attention heads in the GPT-2 language model. Panels (a-c) compare the average attention scores of example induction heads to the scores predicted by the CMR model, showing a close fit. Panel (d) extends this analysis to a duplicate token head, highlighting that even attention heads not traditionally considered induction heads can be well-described by the CMR. Panel (e) shows a strong correlation between CMR distance and induction head matching score, confirming the validity of CMR as a metric for assessing the similarity between an attention head and the CMR model of episodic memory.

read the caption

Figure 5: CMR distance provides meaningful descriptions for attention heads in GPT2. (a-c) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of example induction heads (with a non-zero induction-head matching score and positive copying score). (d) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of a duplicate token head [30] that is traditionally not considered an induction head but can be well-captured by the CMR. (e) (Top) CMR distance (measured by MSE) and the induction-head matching score for each head. (Bottom) Histogram of the CMR distance.

🔼 This figure shows the CMR distance, a metric used to quantify the similarity between attention heads in GPT-2 and the CMR model. It displays the average attention scores and CMR-fitted attention scores for various heads, including both induction heads and a duplicate token head that is not traditionally considered an induction head. The top panel of (e) shows the relationship between CMR distance and induction-head matching scores, while the bottom panel presents a histogram of CMR distances. This figure demonstrates that the CMR distance provides a meaningful way to describe the behavior of different attention heads and captures the attention patterns of heads well-captured by CMR, regardless of their traditional categorization.

read the caption

Figure 5: CMR distance provides meaningful descriptions for attention heads in GPT2. (a-c) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of example induction heads (with a non-zero induction-head matching score and positive copying score). (d) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of a duplicate token head [30] that is traditionally not considered an induction head but can be well-captured by the CMR. (e) (Top) CMR distance (measured by MSE) and the induction-head matching score for each head. (Bottom) Histogram of the CMR distance.

🔼 This figure shows the CMR distance, a metric used to quantify the similarity between attention heads in the GPT-2 language model and the CMR (Contextual Maintenance and Retrieval) model of human episodic memory. The top row (a-c) compares attention patterns of example induction heads in GPT-2 with their CMR-fitted counterparts, demonstrating good agreement. Part (d) shows a similar comparison for a ‘duplicate token’ head, typically not considered an induction head, but which is also well-fit by CMR. Finally, part (e) displays the relationship between CMR distance, induction-head matching score, and the distribution of CMR distances across all heads in GPT-2, indicating that heads with high matching scores and positive copying scores tend to have low CMR distances.

read the caption

Figure 5: CMR distance provides meaningful descriptions for attention heads in GPT2. (a-c) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of example induction heads (with a non-zero induction-head matching score and positive copying score). (d) Average attention scores and the CMR-fitted attention scores of a duplicate token head [30] that is traditionally not considered an induction head but can be well-captured by the CMR. (e) (Top) CMR distance (measured by MSE) and the induction-head matching score for each head. (Bottom) Histogram of the CMR distance.

Full paper#