TL;DR#

Generating equilibrium samples of molecules is computationally expensive. Traditional methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are slow, particularly for systems with multiple metastable states separated by high energy barriers. This makes studying such systems, crucial in drug discovery and materials science, challenging. Boltzmann Generators (BGs) have emerged to address this, using machine learning to learn a transformation from a simple prior distribution to the target Boltzmann distribution. However, existing BGs lack transferability, requiring retraining for each molecule.

This work introduces the first transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG). The TBG learns a transformation that generalizes well to unseen molecules. It uses continuous normalizing flows, trained using flow matching, a simulation-free method. The TBG is evaluated on dipeptides, showcasing its ability to generate unbiased samples of unseen molecules. Furthermore, the TBG improves the efficiency of Boltzmann Generators trained on single molecules. Ablation studies reveal its efficiency even with limited training data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computational chemistry and molecular dynamics because it introduces a novel method for generating equilibrium samples of molecular systems. This transferable Boltzmann Generator significantly speeds up sampling compared to classical methods, opening avenues for simulating larger and more complex molecules, crucial for drug discovery and materials science.

Visual Insights#

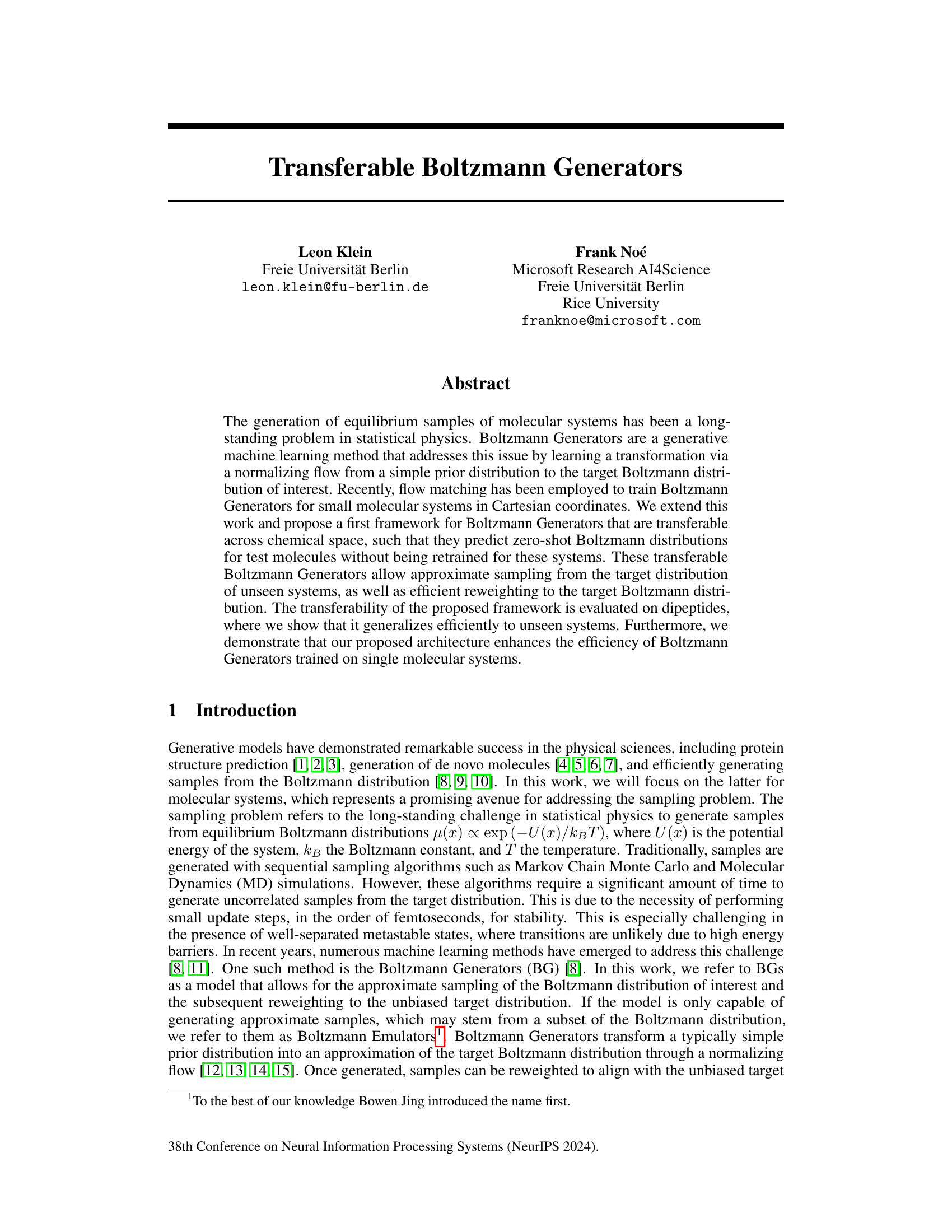

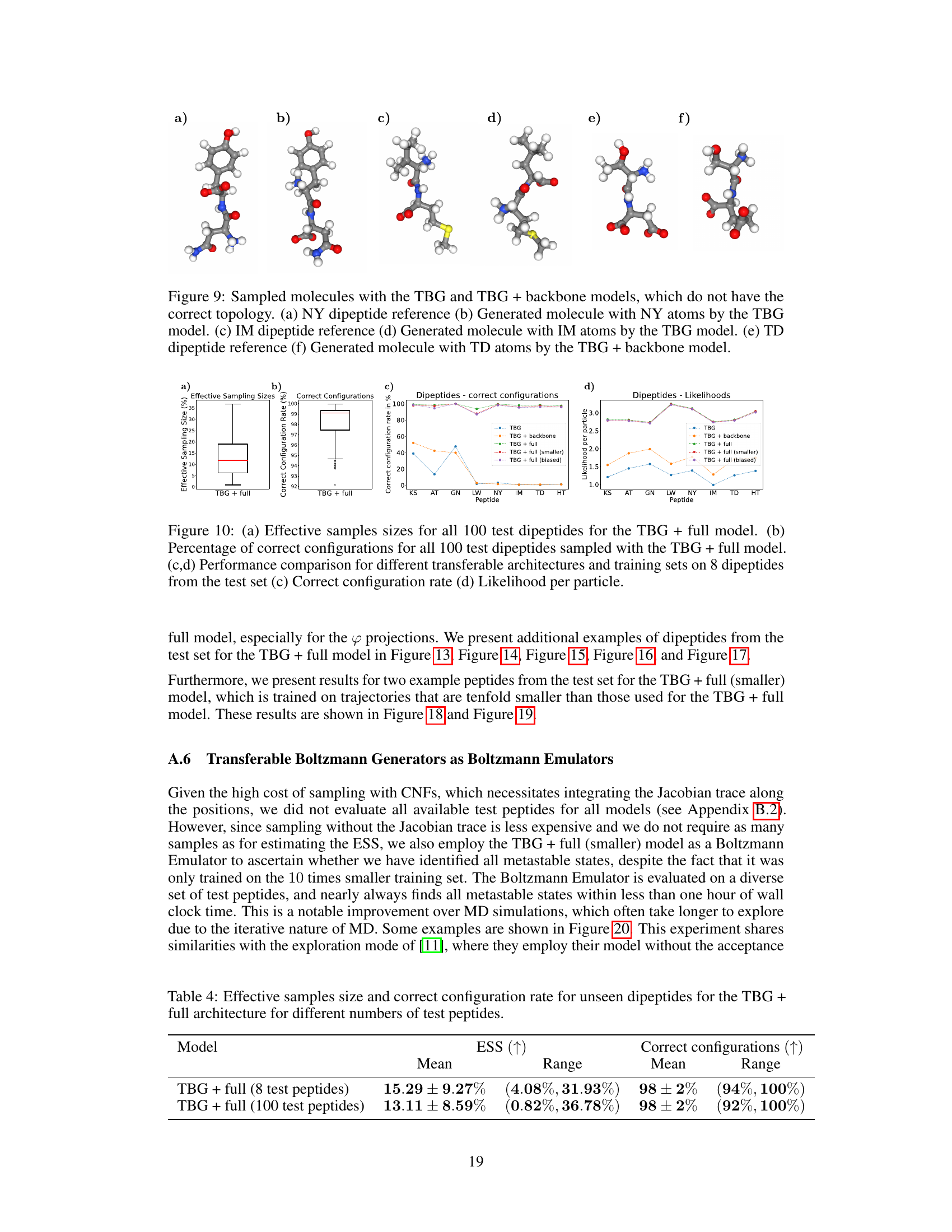

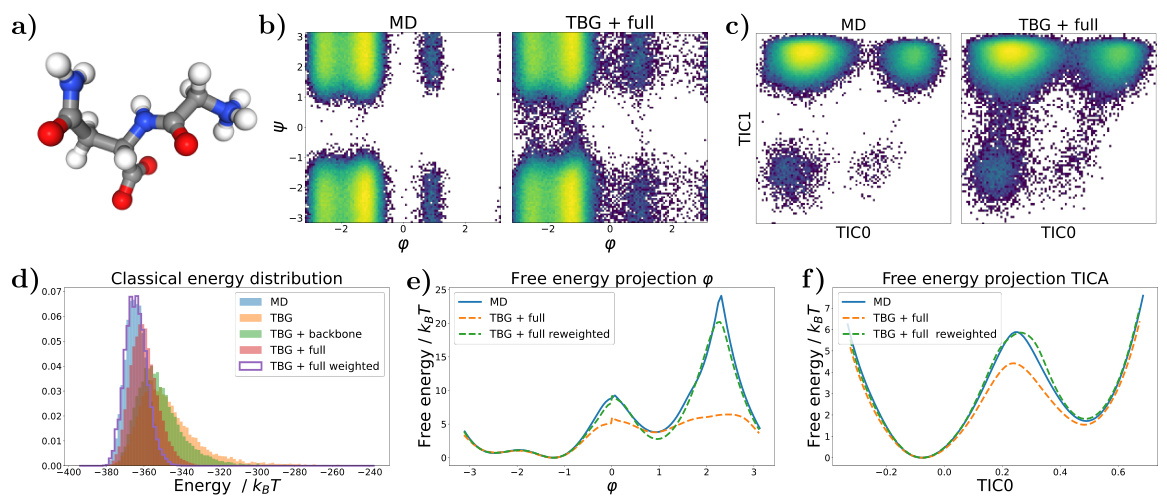

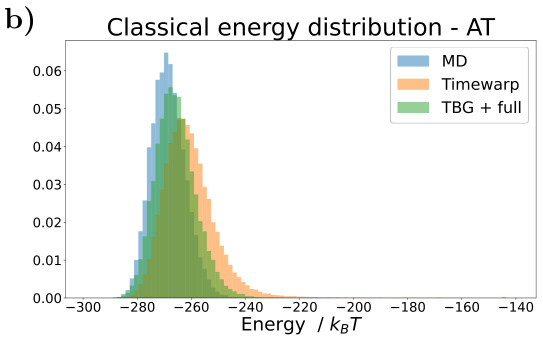

🔼 This figure shows the results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field. Panel (a) presents Ramachandran plots comparing the biased MD distribution with samples generated using the Transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) + full model. Panel (b) displays the energy distributions of samples from various methods: biased MD, TBG + backbone, and TBG + full. Finally, panel (c) shows the free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle) illustrating the performance of the different methods in capturing the free energy landscape.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

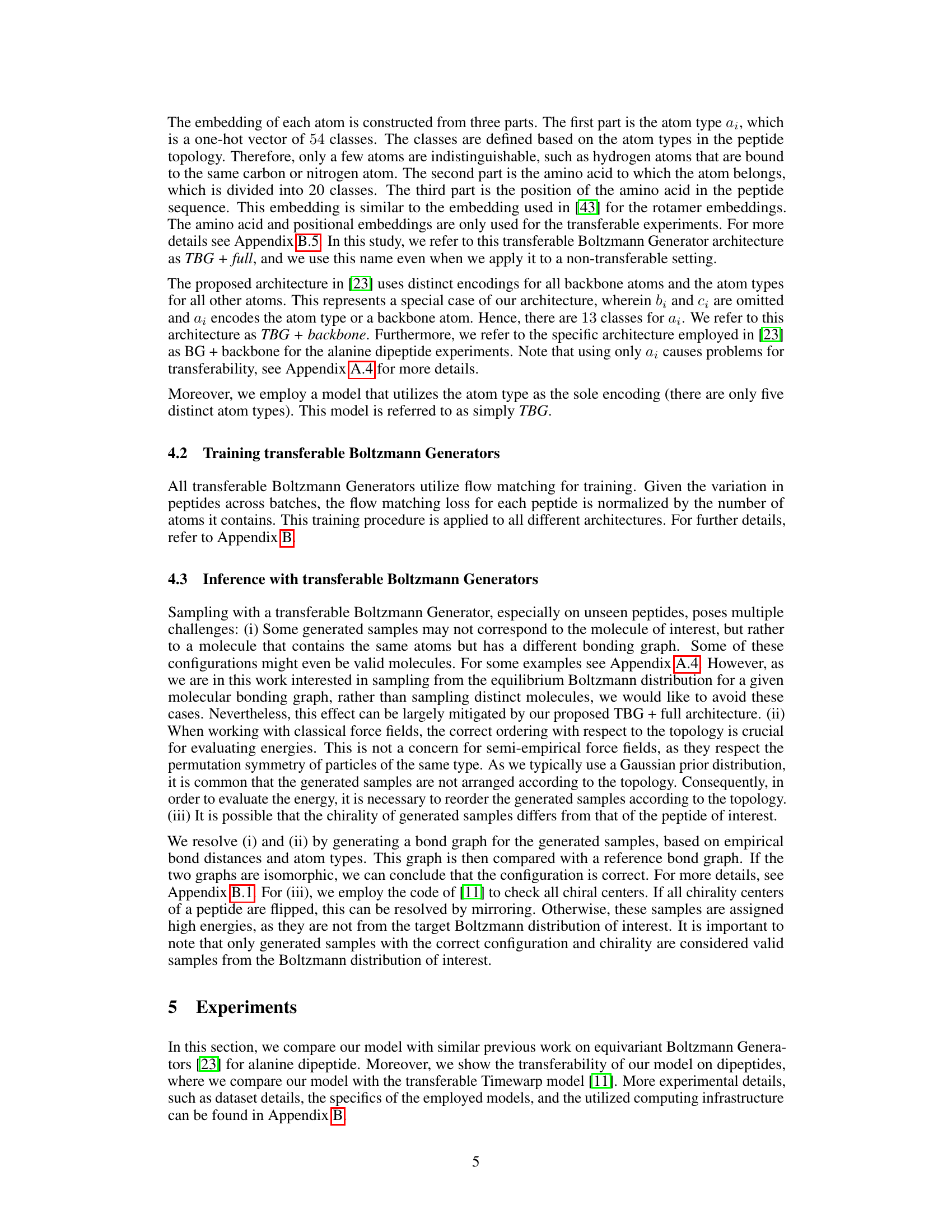

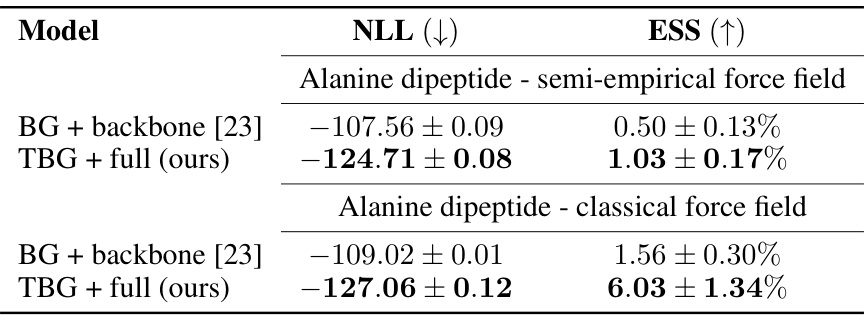

🔼 This table compares the performance of different Boltzmann Generator architectures (BG + backbone from prior work and the newly proposed TBG + full) for the alanine dipeptide molecule. It shows the negative log-likelihood (NLL) and effective sample size (ESS) for both a semi-empirical and classical force field. Lower NLL indicates better model fit, and higher ESS indicates more efficient sampling. The results demonstrate that the proposed TBG + full architecture outperforms the existing BG + backbone architecture in terms of both NLL and ESS, highlighting its improved accuracy and efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Boltzmann Generators with different architectures for the single molecular system alanine dipeptide. Errors are computed over five runs. The results for the Boltzmann Generator and backbone encoding (BG + backbone) for the semi-empirical force field are taken from [23].

In-depth insights#

Transferable BGs#

The concept of “Transferable BGs” (Boltzmann Generators) presents a significant advancement in molecular simulation. Standard BGs are trained on a specific molecular system, limiting their applicability. Transferable BGs aim to overcome this by learning a representation that generalizes across diverse molecular systems. This allows for zero-shot prediction of Boltzmann distributions for unseen molecules, significantly reducing computational cost and time. The core innovation lies in developing a framework that encodes molecular information efficiently, enabling the BG to capture relevant features for various systems. This transferability hinges on finding a suitable prior distribution and developing a robust model architecture. While promising, challenges remain, including the need for larger training sets to account for varied molecule topologies, and the potential necessity of incorporating more intricate force fields for enhanced accuracy. Further research is needed to fully assess the scope and limitations of transferable BGs and to optimize their performance for diverse and complex molecular systems.

CNFs & Flow Matching#

Continuous Normalizing Flows (CNFs) are a powerful class of generative models used to learn complex probability distributions by transforming a simple prior distribution through a sequence of invertible transformations. Flow matching offers a particularly attractive training approach for CNFs because it is simulation-free and therefore computationally efficient, avoiding the need for computationally expensive sampling methods. In this context, flow matching directly learns the vector field that defines the flow transformations by minimizing the distance between the target distribution and its push-forward distribution. This makes it well-suited for applications such as Boltzmann Generators, where the goal is to sample from complex equilibrium distributions, such as those found in molecular systems. By combining CNFs and flow matching, it becomes possible to generate high-quality samples from complex target distributions without expensive sampling, making the method highly efficient for generating equilibrium configurations of various systems. The resulting efficiency gains are especially crucial when dealing with molecular simulations where the evaluation of potential energies is often a computationally demanding task. Transferability is an area of ongoing research, investigating whether CNFs trained on one system can generalize to others without retraining. This is a key challenge in several scientific fields as it would allow for much more efficient exploration of a broader parameter space.

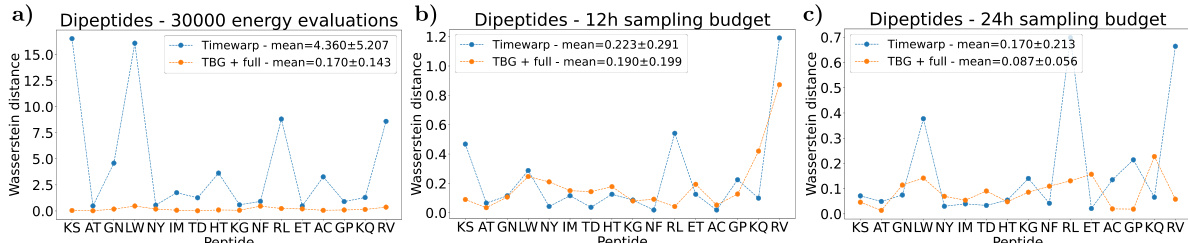

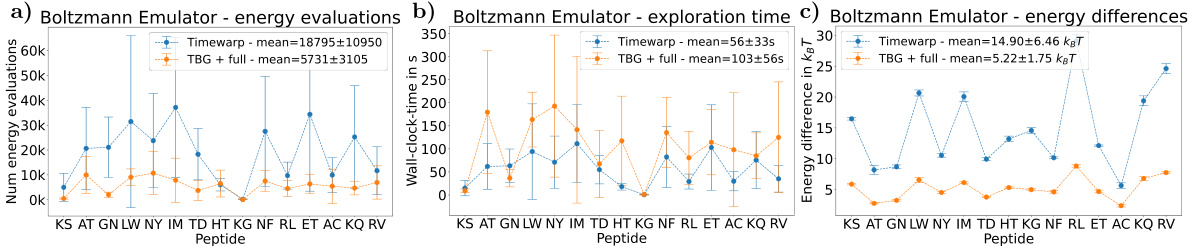

Dipeptide Sampling#

Dipeptide sampling, within the context of the research paper, likely focuses on the computational generation of equilibrium configurations for dipeptides. This involves using advanced machine learning techniques, such as Boltzmann Generators, to efficiently sample from the Boltzmann distribution which represents the probability of observing different conformations at a given temperature. The efficacy of this approach is measured by its ability to generate unbiased, uncorrelated samples and to accurately recover the free energy landscape of the system. Transferability, the ability to apply the model to previously unseen dipeptides without retraining, is a significant goal, demonstrating the model’s robustness and generalization capabilities. Evaluation likely involves comparison with classical methods such as Molecular Dynamics, and assessment of computational efficiency in terms of speed and number of energy calculations required. The choice of dipeptides is likely driven by their size – small enough for computational tractability while large enough to exhibit conformational complexity relevant to larger protein systems.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove or modify parts of a machine learning model to understand their contributions. In this context, an ablation study might involve removing or modifying components of the transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG), such as different network architectures, to assess their individual impact on model performance and transferability. Key insights would likely focus on identifying the essential components for achieving both good performance on the training data and efficient generalization to unseen molecules. For example, the study may compare different equivariant network architectures, evaluating their effectiveness in capturing the symmetries of molecular systems, thereby improving transferability. Another critical aspect is the effect of training data size. A well-designed ablation study would systematically vary training set size to determine the minimal data requirements for effective transfer learning, providing guidance for future applications and highlighting the trade-off between data demands and performance.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize scaling transferable Boltzmann Generators to larger systems, which currently poses a significant computational challenge. Addressing this limitation is crucial for practical applications in areas like drug discovery and materials science. Investigating alternative architectures for the vector field, beyond the EGNNs used in this study, could enhance efficiency and scalability. Exploration of alternative prior distributions, such as harmonic priors, warrants further investigation. Combining the transferable generator framework with advanced sampling methods like optimal transport flow matching would help optimize performance. Finally, a systematic study of the impact of smaller training sets and shorter trajectories on model generalization is needed to fully understand the potential data-efficiency of the approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

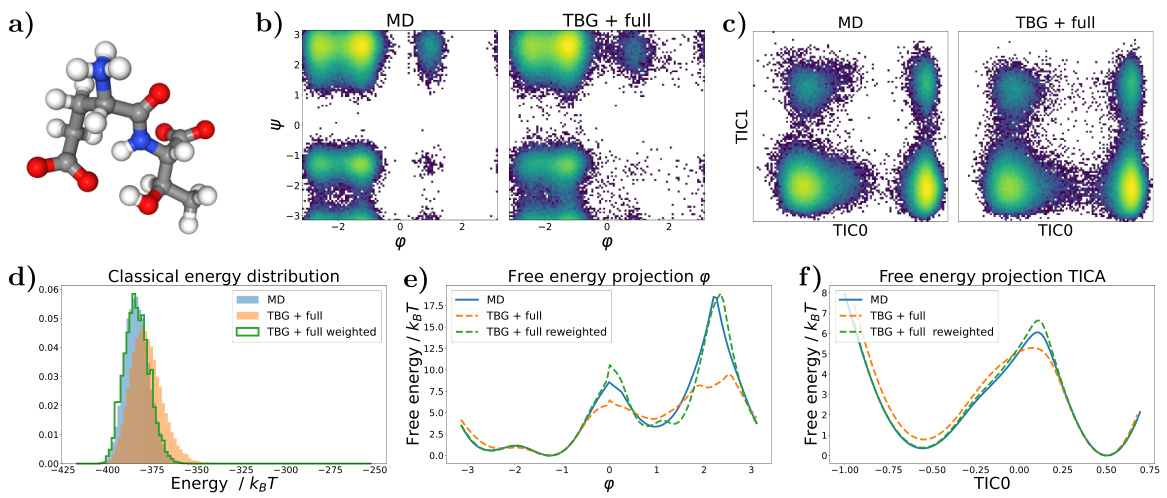

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of different methods for simulating the alanine dipeptide molecule, focusing on the accuracy of free energy landscape reproduction. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots, visualizing the distribution of dihedral angles (φ and ψ). The biased MD distribution and the samples generated by the transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG + full model) are compared. Panel (b) displays the energy distributions from various methods. Finally, panel (c) shows free energy profiles along the slowest reaction coordinate (φ), highlighting the accuracy and efficiency of the proposed TBG + full model compared to other approaches such as biased MD.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of results obtained using different methods for simulating the alanine dipeptide system with a classical force field. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots, visualizing the conformational landscape. The biased MD distribution is compared to samples generated by the Transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) model. Panel (b) compares the energy distributions of samples generated by various methods, including biased MD, the TBG model, and the reweighted TBG samples. Finally, panel (c) illustrates the free energy projection along the slowest transition coordinate (φ angle), further highlighting the performance of the TBG + full model in reproducing the correct free energy landscape.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure shows the results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated using different methods: biased MD, Boltzmann Generator with backbone encoding (BG + backbone), and the proposed transferable Boltzmann Generator with full architecture (TBG + full). Panel (a) compares Ramachandran plots visualizing the conformational space sampled by each method. Panel (b) provides a comparison of the energy distributions obtained. Panel (c) displays the free energy projection along the slowest transition coordinate (φ angle), illustrating the free energy landscape generated by each approach and its agreement with the reference (umbrella sampling) calculation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure displays results for the alanine dipeptide, comparing different sampling methods. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots visualizing the conformational space sampled by biased molecular dynamics (MD) and the transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) + full model. Panel (b) presents the energy distributions of samples generated via different techniques. Panel (c) illustrates free energy profiles along the slowest-moving dihedral angle (φ), highlighting the ability of the TBG+full model to accurately capture the free energy landscape.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

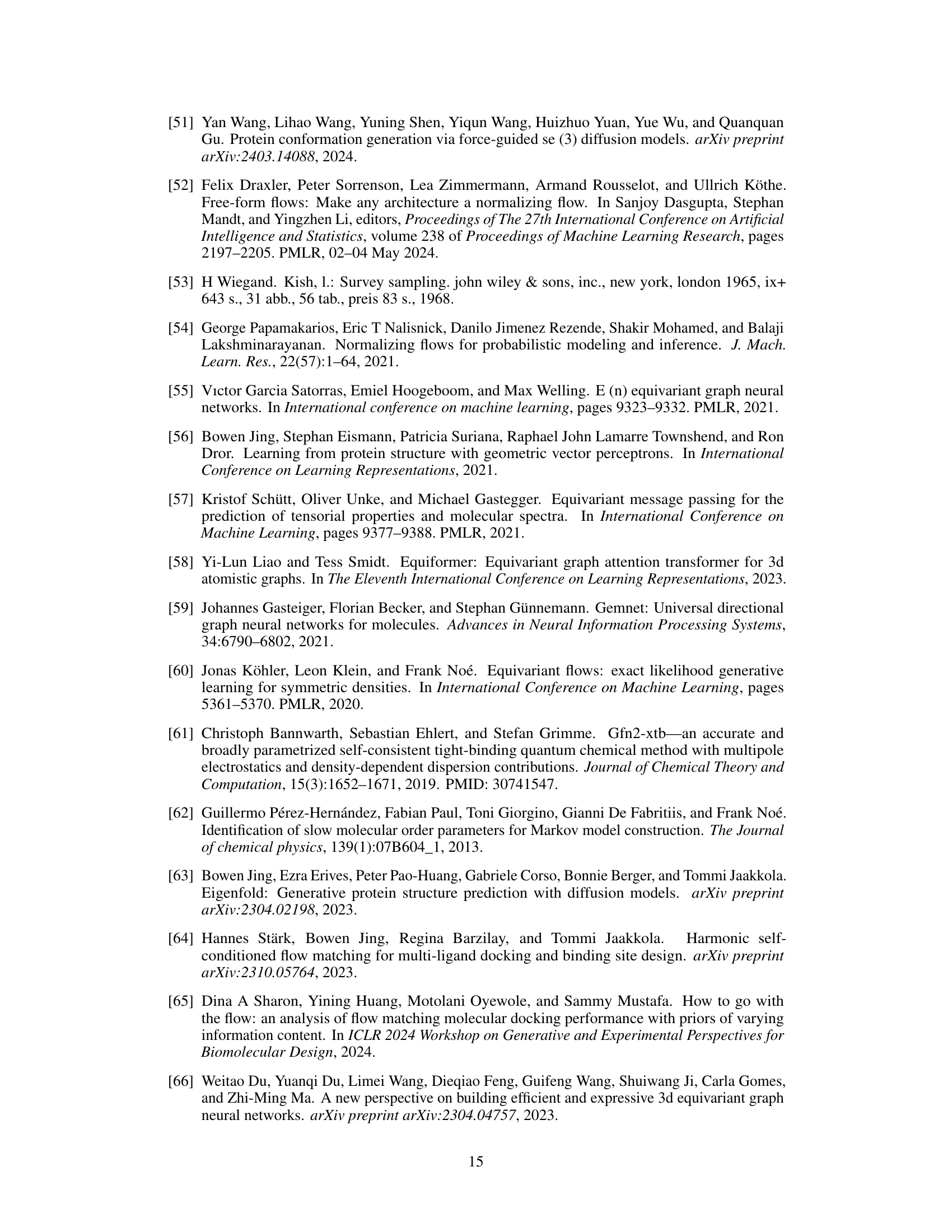

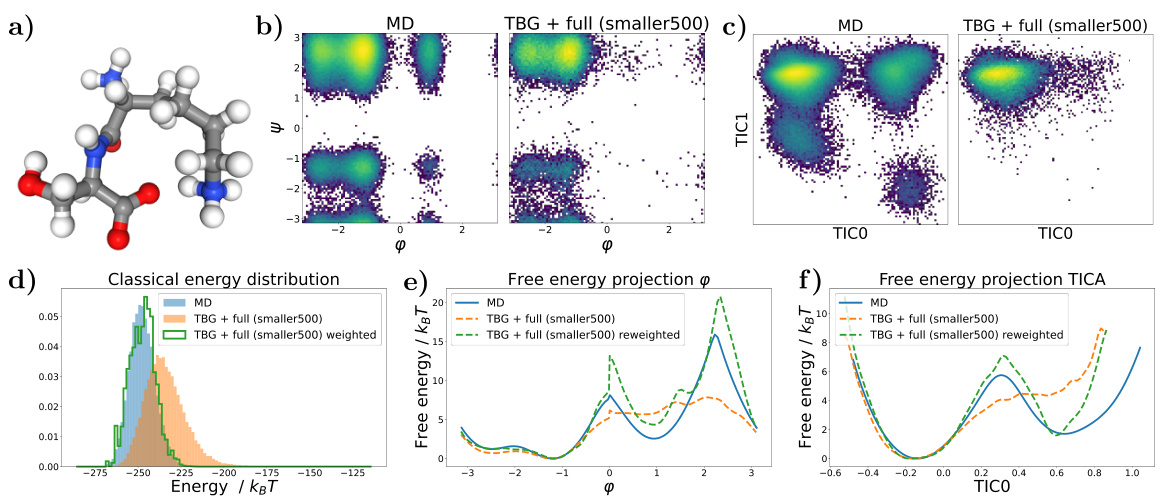

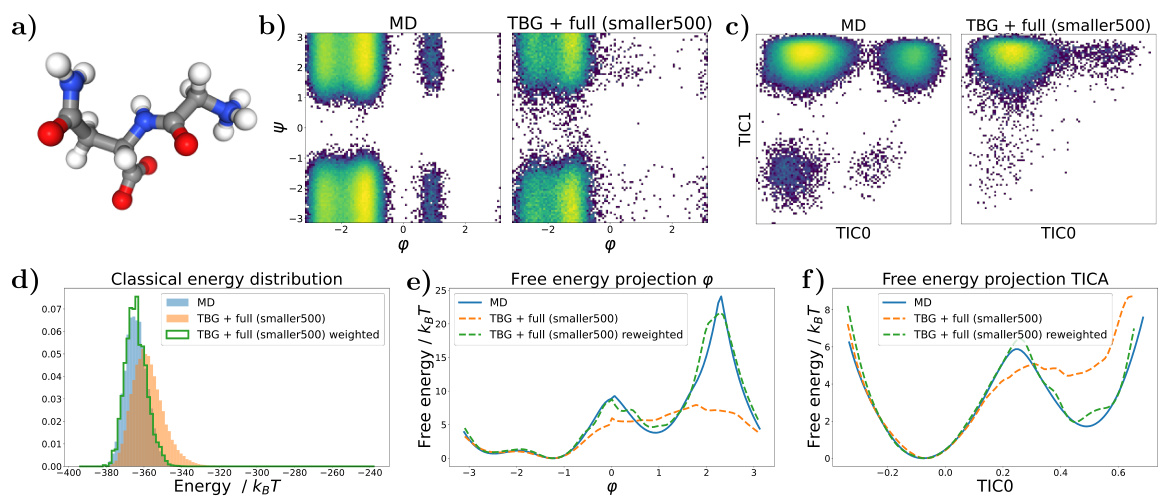

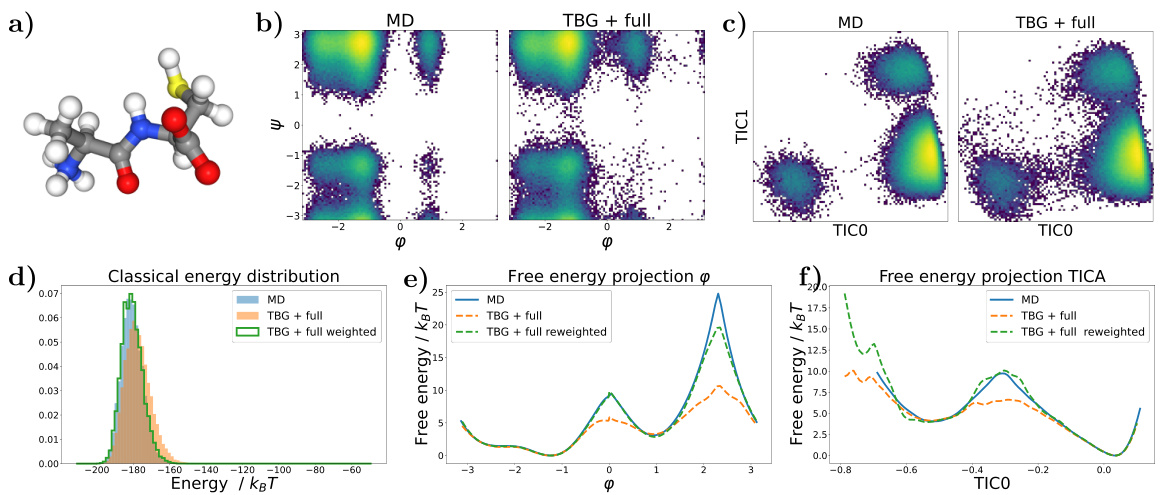

🔼 Figure 7 shows the results for the KS dipeptide when the TBG + full model is trained with 100 times smaller training trajectories compared to the results in Figure 2. Subfigures (a) through (f) show a Ramachandran plot, TICA plot, energy distribution, and free energy projections along both φ and the slowest transition coordinate (TIC0). The results from the model trained on the shorter trajectories are significantly worse compared to the model trained on longer trajectories. This highlights the importance of adequate sampling during training to capture all relevant metastable states.

read the caption

Figure 7: Results for the KS dipeptide for TBG + full model trained on 100 times smaller training trajectories. As can be seen in Figure 2, the results for the TBG + full model trained on the whole trajectories are much better. (a) KS dipeptide (b) Ramachandran plot for the weighted MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the model (right). (c) TICA plot for the weighted MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the model (right). (d) Energies of samples generated with the model. (e) Free energy projection along the φ angle. (f) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (TICO).

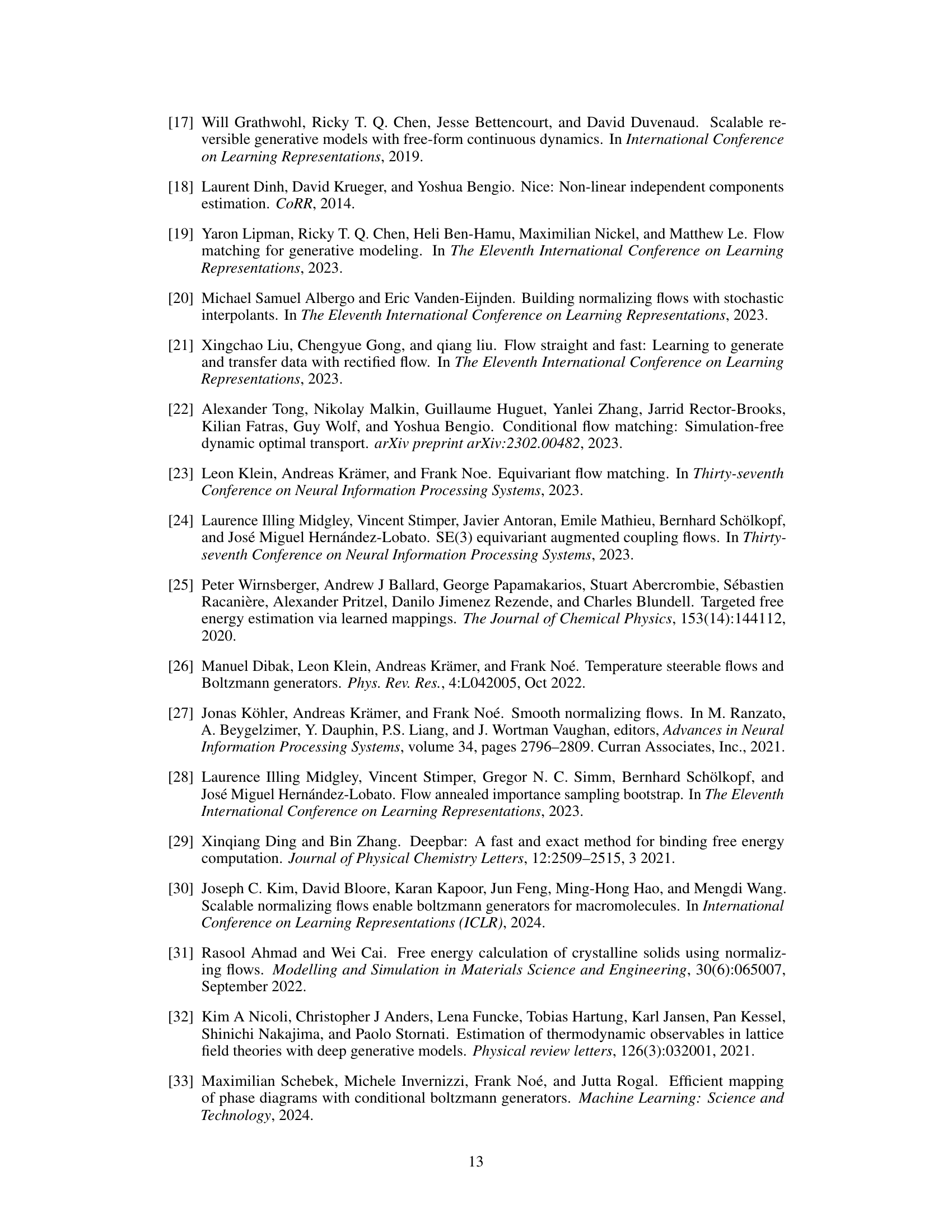

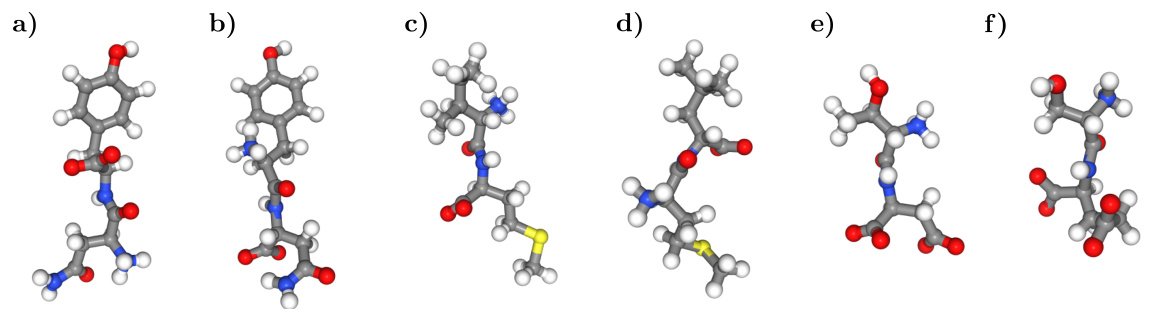

🔼 This figure shows examples of molecules sampled by the TBG and TBG + backbone models that have incorrect topologies, highlighting a limitation of these models in correctly capturing molecular structures. It contrasts these incorrect samples with the correct reference structures for NY, IM, and TD dipeptides, illustrating the failure of the TBG and TBG + backbone models to accurately reproduce the correct bonding configurations. The figure emphasizes the improved performance of the TBG + full model in this regard, which is not shown here but referenced in the text.

read the caption

Figure 9: Sampled molecules with the TBG and TBG + backbone models, which do not have the correct topology. (a) NY dipeptide reference (b) Generated molecule with NY atoms by the TBG model. (c) IM dipeptide reference (d) Generated molecule with IM atoms by the TBG model. (e) TD dipeptide reference (f) Generated molecule with TD atoms by the TBG + backbone model.

🔼 This figure compares different methods for simulating the alanine dipeptide, focusing on the accuracy of the free energy landscape. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots, visualizing the conformational space sampled by biased molecular dynamics (MD) and the transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) + full model. Panel (b) presents energy distributions for each method. Panel (c) displays free energy projections along the slowest transition coordinate (φ angle), highlighting differences in sampling efficiency and accuracy. The TBG + full model shows improved performance in sampling and recovering the correct free energy landscape compared to traditional methods.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure shows the results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots comparing the biased MD distribution with samples generated using the transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) + full model. Panel (b) presents a comparison of the energies of samples generated by different methods: biased MD, TBG + full, and TBG + full after reweighting. Finally, panel (c) displays the free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle) calculated using different approaches. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness of the TBG + full model in accurately capturing the energy landscape of the system, particularly after reweighting.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure shows the results for alanine dipeptide simulations using classical force fields. Panel (a) presents Ramachandran plots comparing biased molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with samples generated using the transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) with a full architecture. Panel (b) displays energy distributions for the different methods. Panel (c) shows free energy projections along the slowest transition coordinate (φ angle). The TBG + full model demonstrates improved performance in aligning with the reference MD simulation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of results obtained using different methods for simulating the alanine dipeptide system. The methods include biased molecular dynamics (MD), a Boltzmann Generator with a backbone encoding (BG + backbone), and a transferable Boltzmann Generator with a full encoding (TBG + full). Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots, illustrating the conformational space sampled by each method. Panel (b) compares the energy distributions of the generated samples. Panel (c) depicts the free energy profiles along the slowest transition coordinate (φ dihedral angle). This provides a comprehensive comparison of the accuracy and efficiency of different sampling techniques.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure presents the results of simulations on the alanine dipeptide system using both classical molecular dynamics (MD) and the proposed Transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) model. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots, visualizing the conformational space sampled by each method. Panel (b) displays energy distributions for samples from each simulation method, highlighting the differences in energy coverage and bias. Panel (c) presents a free energy profile calculated along the slowest-moving transition coordinate (φ dihedral angle), demonstrating the TBG model’s ability to recover the correct free energy landscape.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying different methods to simulate the alanine dipeptide system. Panel (a) compares Ramachandran plots from biased molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with those generated by the Transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) model. Panel (b) presents a comparison of the energy distributions obtained from various methods. Finally, panel (c) displays free energy projections along the slowest transition coordinate (φ angle) from these simulations, highlighting the enhanced accuracy and efficiency of the TBG + full model.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure shows the results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated using both classical MD and the proposed Transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) with the full architecture. Panel (a) compares Ramachandran plots from biased MD simulations to those generated by the TBG model, illustrating the model’s ability to sample conformations. Panel (b) presents the energy distributions for samples generated using different methods (biased MD, TBG + full model), while panel (c) displays the free energy profiles along the slowest conformational transition coordinate (ψ angle) comparing different sampling methods demonstrating the TBG model’s effectiveness in accurately representing the system’s energy landscape.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (ψ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 This figure displays the results of simulating the alanine dipeptide system using various methods. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots, comparing the biased molecular dynamics (MD) simulation with samples generated using the transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) + full model. Panel (b) provides a comparison of the energies of samples from different methods. Finally, panel (c) presents the free energy projection along the slowest transition (the φ angle) calculated using several methods, illustrating the accuracy of the TBG + full model in capturing the free energy landscape.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

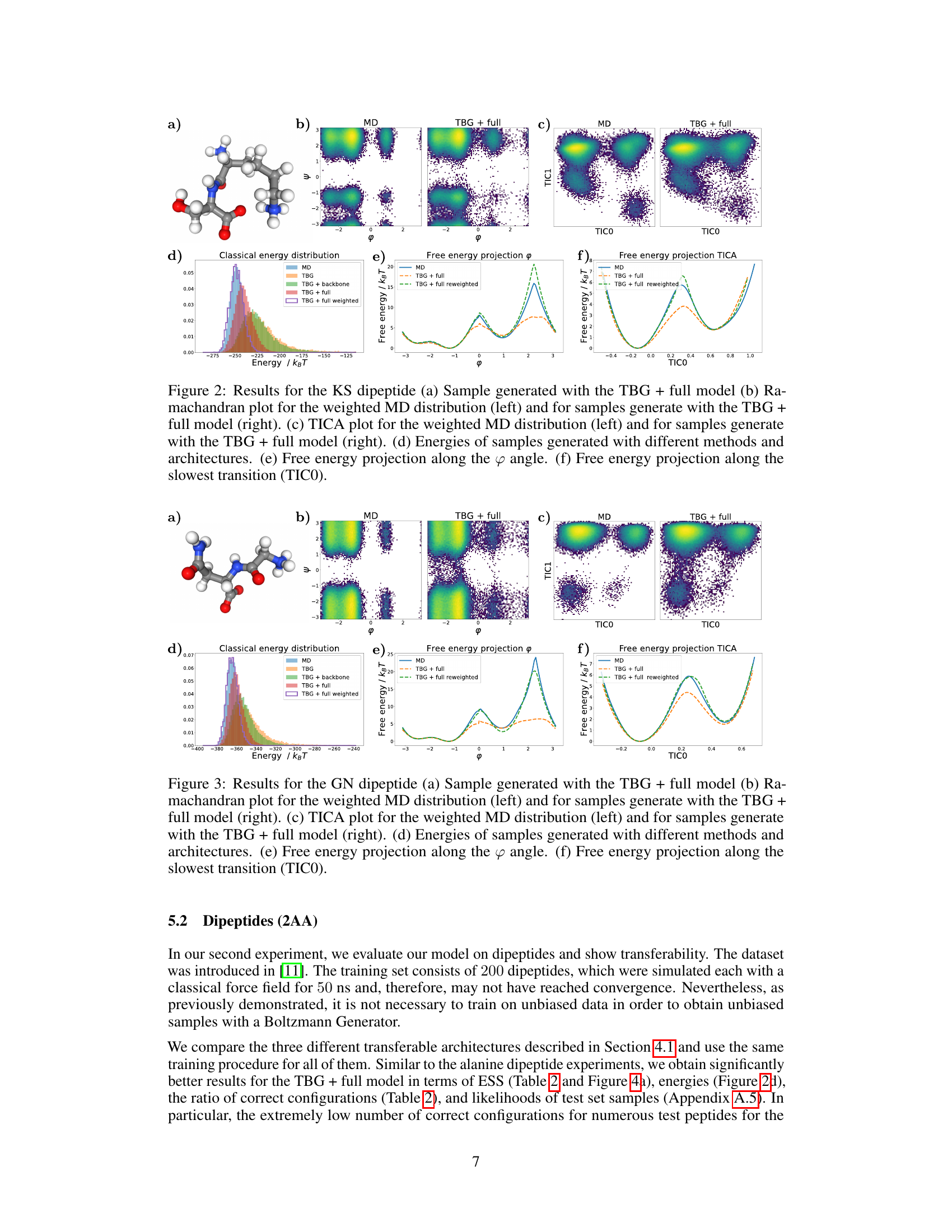

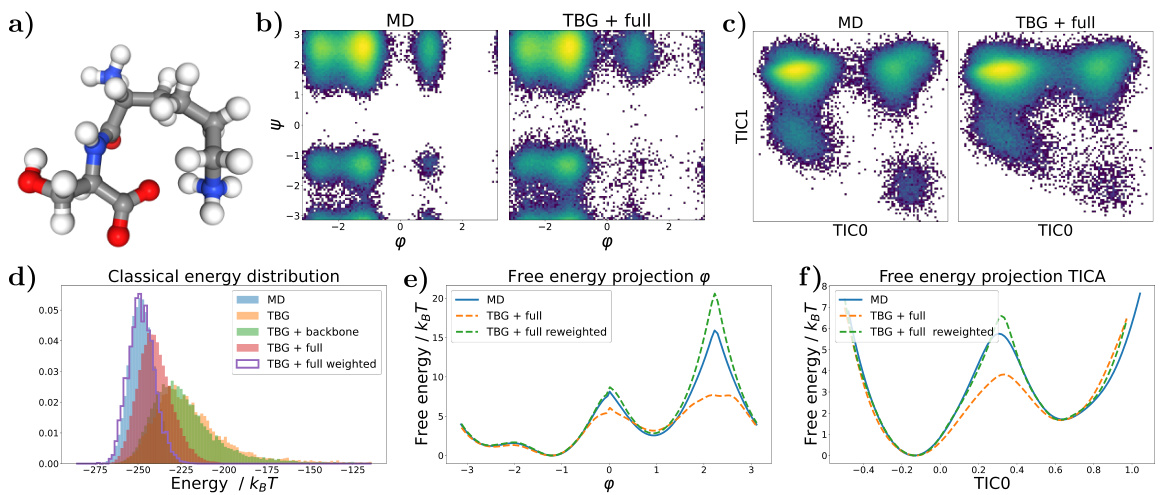

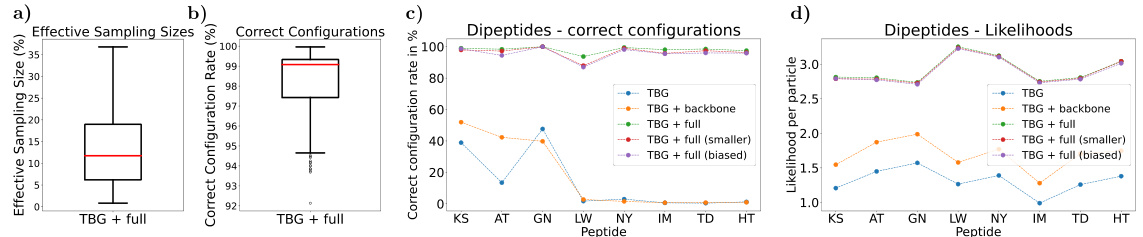

🔼 This figure displays the results for the KS dipeptide using the Transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) with the full architecture. It shows a Ramachandran plot, TICA plot, energy distributions, and free energy projections along φ and the slowest collective variable (TIC0), comparing the TBG + full model with other methods and architectures. The results demonstrate the TBG + full model’s ability to effectively sample from the target Boltzmann distribution.

read the caption

Figure 2: Results for the KS dipeptide (a) Sample generated with the TBG + full model (b) Ramachandran plot for the weighted MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (c) TICA plot for the weighted MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (d) Energies of samples generated with different methods and architectures. (e) Free energy projection along the φ angle. (f) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (TIC0).

🔼 This figure presents the results for alanine dipeptide simulations using classical force fields. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots comparing biased molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to those generated with the Transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) + full model. The TBG + full model successfully samples the relevant conformational space of the dipeptide, mirroring the MD results. Panel (b) provides a direct energy comparison of the samples generated with the different methods; highlighting the enhanced sampling capabilities of the TBG model. Finally, panel (c) displays the free energy profiles along the slowest transition coordinate (φ dihedral angle), computed using various methods, to showcase that the TBG model accurately reproduces the free energy landscape.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

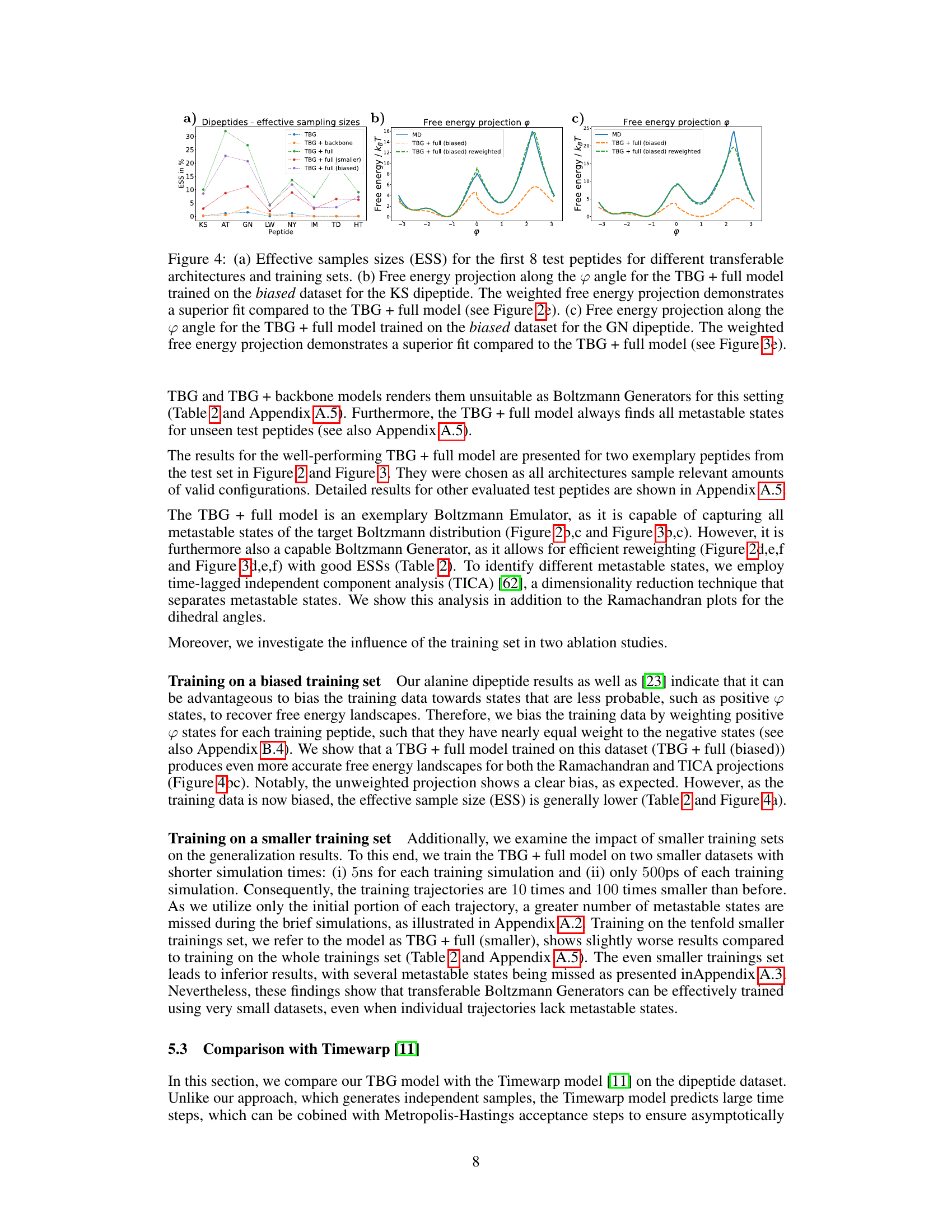

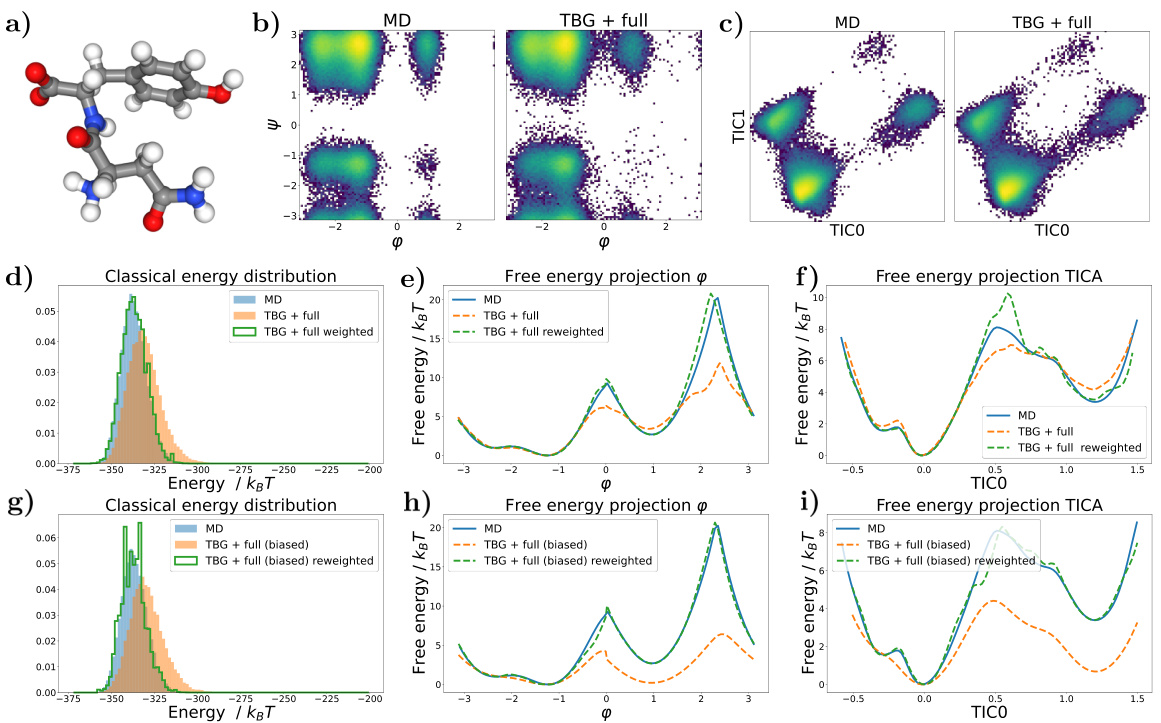

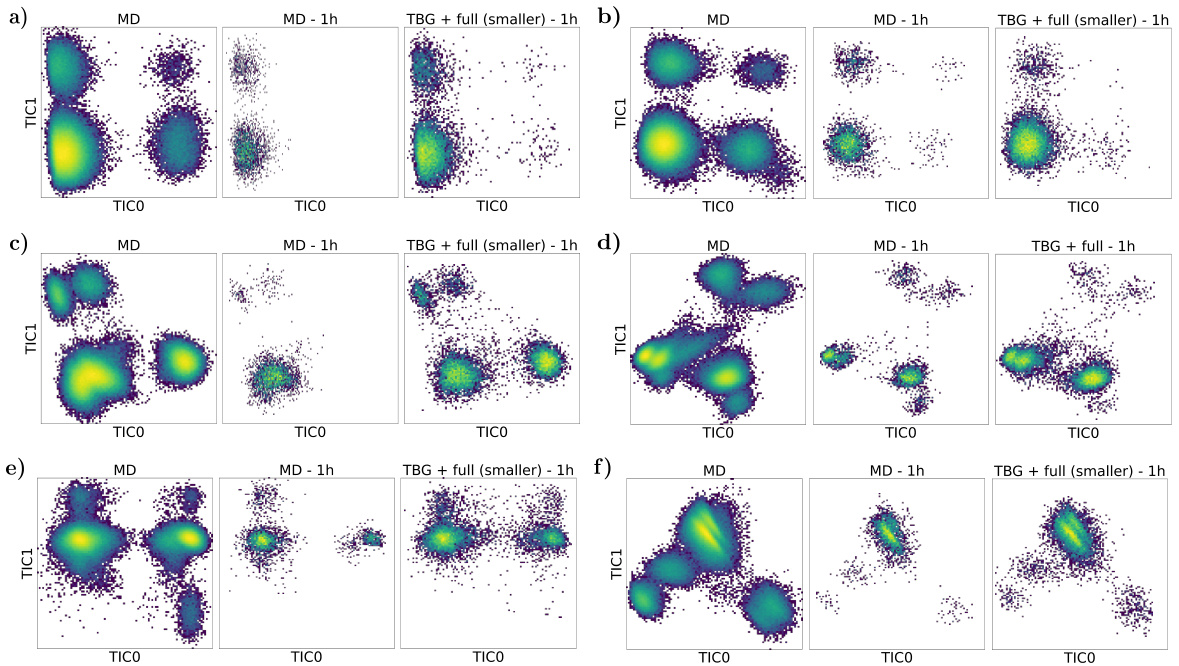

🔼 This figure compares the results of classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and the proposed Transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) model for six different dipeptides. The TBG model is run for a shorter time (1 hour) without reweighting, while the MD simulations run for a longer period (1 hour). TICA plots are used to visualize the different metastable states of the dipeptides. The comparison showcases the ability of the TBG model to efficiently sample from the Boltzmann distribution, even in a shorter time frame, and to capture the relevant metastable states.

read the caption

Figure 20: Comparison of classical MD runs for 1 hour (MD - 1h) and the sampling with the TBG + full (smaller) model without weight computation for 1 hour (TBG + full (smaller) - 1h). The TICA plots of different peptides from the test set are shown. It is important to note that the TICA projection is always computed with respect to the long MD trajectory (MD). All peptides stem from the test set. (a) CS dipeptide (b) EK dipeptide (c) KI dipeptide (d) LW dipeptide (e) RL dipeptide (f) TF dipeptide.

🔼 This figure shows the results of simulations for alanine dipeptide using a classical force field. It compares three different methods: biased MD, the Boltzmann Generator with backbone encoding, and the transferable Boltzmann Generator with the full architecture. Panel (a) displays Ramachandran plots illustrating the conformational distributions obtained by each method. Panel (b) presents a comparison of the energy distributions generated by each method, highlighting the differences in their sampling efficiency. Finally, panel (c) shows a free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), allowing the comparison of the accuracy in the free energy landscape reconstruction for each method.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

🔼 The figure presents a comparison of different methods for simulating the alanine dipeptide system. Panel (a) shows Ramachandran plots comparing biased molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and samples generated using the transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) with the full architecture. Panel (b) shows energy distributions for each method, highlighting differences in energy landscape exploration. Panel (c) displays the free energy profile along the slowest-transitioning dihedral angle (φ) based on MD simulations, the TBG model with a full architecture, and the same TBG model after reweighting.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for the alanine dipeptide system simulated with a classical force field (a) Ramachandran plots for the biased MD distribution (left) and for samples generate with the TBG + full model (right). (b) Energies of samples generated with different methods. (c) Free energy projection along the slowest transition (φ angle), computed with different methods.

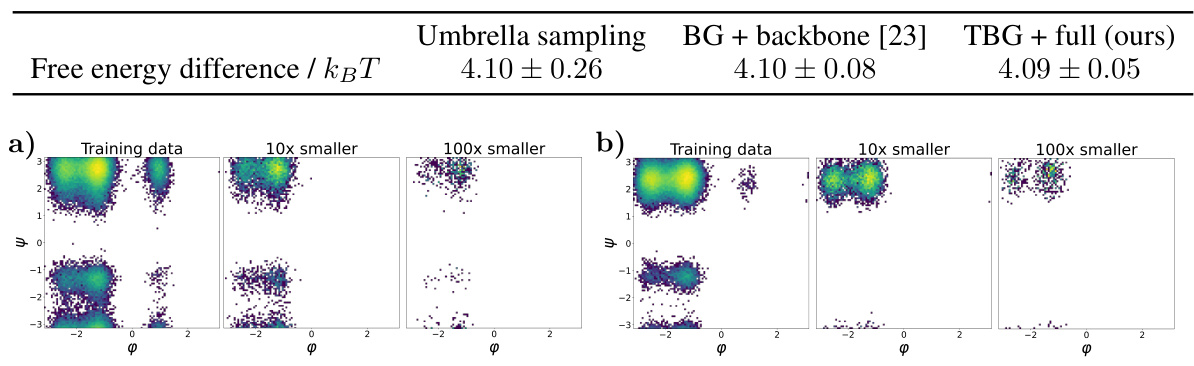

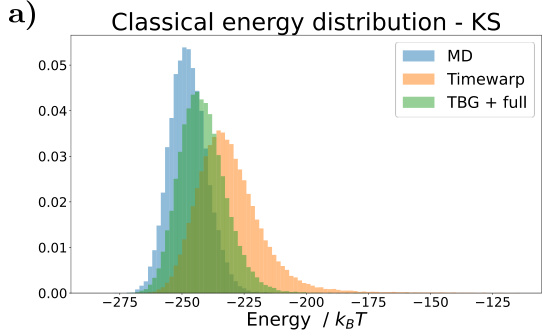

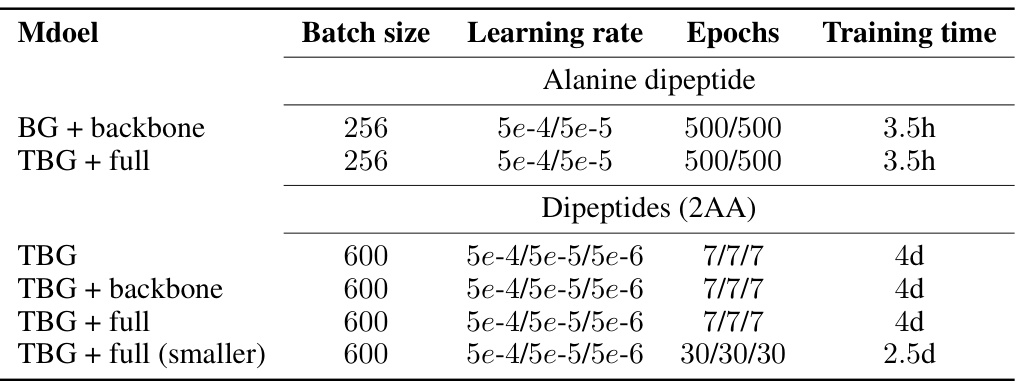

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the performance of different Boltzmann Generator architectures (TBG, TBG + backbone, TBG + full) in generating samples for the alanine dipeptide molecule using both semi-empirical and classical force fields. It shows the negative log-likelihood (NLL), effective sample size (ESS), and percentage of correct configurations for each model. Lower NLL and higher ESS indicate better performance. The results for the BG + backbone model from a previous study ([23]) are included for comparison.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Boltzmann Generators with different architectures for the single molecular system alanine dipeptide. Errors are computed over five runs. The results for the Boltzmann Generator and backbone encoding (BG + backbone) for the semi-empirical force field are taken from [23].

🔼 This table compares the performance of different Boltzmann Generator architectures (BG + backbone, TBG + full) on the alanine dipeptide system using both semi-empirical and classical force fields. It presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL), effective sample size (ESS), and shows that the TBG + full model outperforms the BG + backbone model in terms of both likelihood and sampling efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Boltzmann Generators with different architectures for the single molecular system alanine dipeptide. Errors are computed over five runs. The results for the Boltzmann Generator and backbone encoding (BG + backbone) for the semi-empirical force field are taken from [23].

🔼 This table presents the performance of different transferable Boltzmann Generator architectures on unseen dipeptides, evaluating their efficiency (Effective Sample Size or ESS) and accuracy (percentage of correctly generated configurations). The results are averaged over 8 test dipeptides, with a reference to Appendix A.5 for a more comprehensive analysis of 100 dipeptides.

read the caption

Table 2: Effective samples size and correct configuration rate for unseen dipeptides across different transferable Boltzmann Generator (TBG) architectures. The values are computed for 8 test dipeptides. See Appendix A.5 for more results.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different Boltzmann Generator architectures (BG + backbone, TBG + full) in terms of negative log-likelihood (NLL) and effective sample size (ESS) for alanine dipeptide simulations using both semi-empirical and classical force fields. Lower NLL indicates better performance while higher ESS means more efficient sampling.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Boltzmann Generators with different architectures for the single molecular system alanine dipeptide. Errors are computed over five runs. The results for the Boltzmann Generator and backbone encoding (BG + backbone) for the semi-empirical force field are taken from [23].

🔼 This table compares the performance of different Boltzmann Generator architectures (BG + backbone, TBG + full) for the alanine dipeptide molecule using both semi-empirical and classical force fields. It shows the negative log-likelihood (NLL), effective sample size (ESS), and the error associated with each method. Lower NLL indicates better model fit, higher ESS reflects better sampling efficiency. The results from a previous study (BG + backbone) are included for comparison.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Boltzmann Generators with different architectures for the single molecular system alanine dipeptide. Errors are computed over five runs. The results for the Boltzmann Generator and backbone encoding (BG + backbone) for the semi-empirical force field are taken from [23].

🔼 This table compares the performance of three different Boltzmann Generator architectures (BG + backbone, TBG + full, and TBG) on the alanine dipeptide molecule using both semi-empirical and classical force fields. It presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL), effective sample size (ESS), and shows that the TBG + full model significantly outperforms the BG + backbone model in terms of both NLL and ESS for both force fields.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Boltzmann Generators with different architectures for the single molecular system alanine dipeptide. Errors are computed over five runs. The results for the Boltzmann Generator and backbone encoding (BG + backbone) for the semi-empirical force field are taken from [23].

Full paper#