↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (GCRL) faces challenges with sparse rewards and efficient exploration. Existing model-based RL methods struggle to generalize learned world models to unseen state transitions, hindering accurate real-world dynamic modeling. This limits the ability of agents to explore effectively and learn policies capable of generalizing to new goals.

The paper introduces MUN, a novel goal-directed exploration algorithm to tackle these challenges. MUN leverages a bidirectional replay buffer and a subgoal discovery strategy (DAD) to enhance world model learning. The algorithm’s ability to model state transitions between arbitrary subgoal states leads to significantly improved policy generalization and exploration capabilities across various robotic tasks. Experimental results highlight MUN’s superior efficiency and generalization compared to existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in reinforcement learning and robotics because it introduces a novel solution to the exploration problem in goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (GCRL) environments with sparse rewards. This is a significant challenge in the field, and the proposed method, MUN, offers a potentially transformative approach. The findings are relevant to current trends in model-based RL and open new avenues for improving exploration efficiency and generalization capabilities.

Visual Insights#

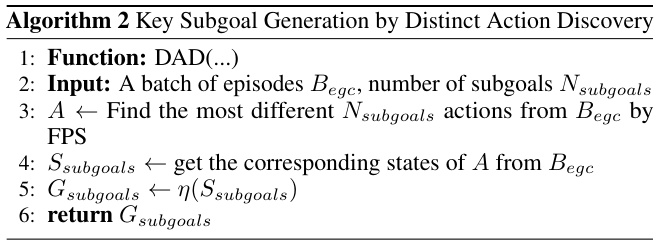

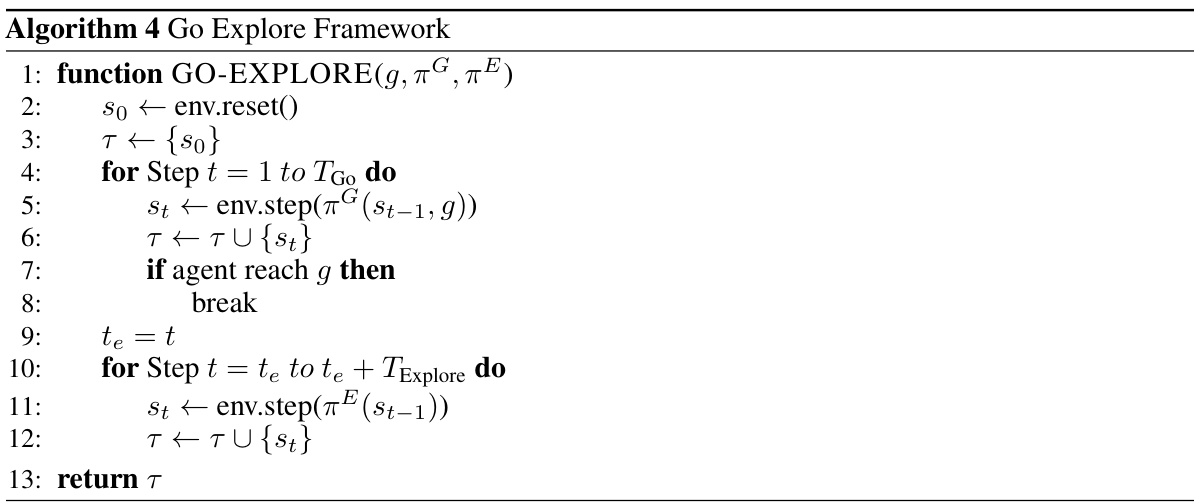

This figure illustrates the general framework of model-based reinforcement learning. Data from interactions with a real environment are collected and stored in a replay buffer. This replay buffer contains state-action-state triplets from the agent’s experiences. This data is used to train a world model which captures the environment’s dynamics. The world model is then used to train an actor and critic, which together form a goal-conditioned policy. This policy allows the agent to plan actions and learn effectively, especially in sparse reward scenarios.

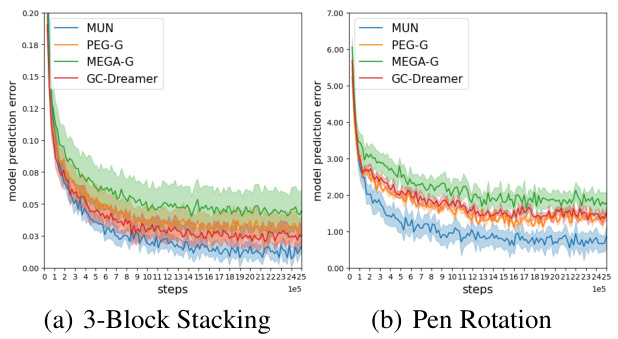

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the world model prediction quality between MUN and its baseline methods across various benchmark environments. It shows the compounding prediction error (multi-step prediction error) of learned world models, calculated by generating simulated trajectories and comparing them to real trajectories. Lower values indicate better prediction accuracy.

In-depth insights#

Goal-directed Exploration#

Goal-directed exploration in reinforcement learning aims to enhance the efficiency of finding rewards by guiding the agent’s actions towards specific objectives. Instead of random exploration, it leverages a learned model of the environment or predefined subgoals to strategically focus the search process. This approach is particularly beneficial in scenarios with sparse or delayed rewards, where random exploration can be inefficient or impossible. Effective goal-directed exploration requires a robust mechanism to set meaningful and achievable goals. The selection of goals can significantly impact the agent’s learning trajectory, necessitating algorithms that balance exploration and exploitation. Furthermore, generalization capabilities are crucial, as a successful strategy should enable the agent to navigate diverse environments and adapt to unseen situations, without the need for retraining. Therefore, the effectiveness of goal-directed exploration heavily depends on the quality of the environment model, goal setting, and adaptation strategies used.

World Model Training#

World model training in the context of goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (GCRL) is crucial for effective exploration and policy learning. The quality of the world model directly impacts the agent’s ability to generalize to unseen states and navigate complex environments. Effective training necessitates a rich and diverse dataset, often achieved through carefully designed exploration strategies. Simple approaches may fail to capture the nuances of real-world dynamics, particularly regarding transitions between states across different trajectories or backwards along recorded trajectories. Advanced techniques often employ bidirectional replay buffers, allowing the model to learn from both forward and backward transitions, leading to improved generalization. Another key aspect is the identification of crucial ‘key’ states, representing significant milestones within a task. Focusing training on transitions between these key states further enhances generalization. Goal-directed exploration algorithms are invaluable for generating the necessary data and ensuring sufficient coverage of the state space. Overall, the success of world model training hinges on a sophisticated interplay between data collection, model architecture, and training objectives.

Subgoal Discovery#

Effective subgoal discovery is crucial for efficient exploration in complex environments. The paper highlights the limitations of existing methods, often relying on simple heuristics or requiring significant domain expertise. The proposed DAD (Distinct Action Discovery) method offers a data-driven approach, identifying key subgoals by analyzing distinct actions performed during task completion. This method is appealing for its practicality and generalizability. Instead of relying on pre-defined or manually specified subgoals, DAD leverages the rich information present in the agent’s replay buffer to discover meaningful milestones. This automated process reduces the need for human intervention and enables the algorithm to adapt to various task settings. However, the effectiveness of DAD might be affected by task complexity and the structure of the action and goal spaces, suggesting potential areas for future improvement. Further research could explore more sophisticated techniques for subgoal identification, possibly integrating machine learning methods to improve robustness and efficiency. The success of DAD underscores the importance of data-driven approaches to solve challenging problems in reinforcement learning.

Generalization#

The concept of generalization is central to evaluating the effectiveness of the world models. The paper highlights the challenge of achieving robust generalization in goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (GCRL), especially with sparse rewards. The core issue revolves around the ability of the learned world model to accurately predict state transitions not only along recorded trajectories but also between states across different trajectories. The proposed MUN algorithm directly addresses this limitation by enhancing the richness and diversity of the replay buffer, which substantially improves the world model’s capacity to generalize to unseen situations. A crucial aspect is the introduction of a bidirectional replay buffer, enabling the model to learn both forward and backward transitions. This significantly strengthens the ability of the model to generalize to novel goal settings and improves the policy’s overall performance. The effectiveness of the MUN algorithm’s generalization capability is demonstrated through empirical results across several challenging robotic manipulation and navigation tasks, showcasing the approach’s superiority over traditional methods. Further, the paper explores strategies for identifying key subgoal states to guide the exploration process, impacting the quality of generalization in the world model. This addresses the critical aspect of exploration in sparse-reward settings, improving not only the diversity of the training data but also the relevance and interpretability of the learned representations.

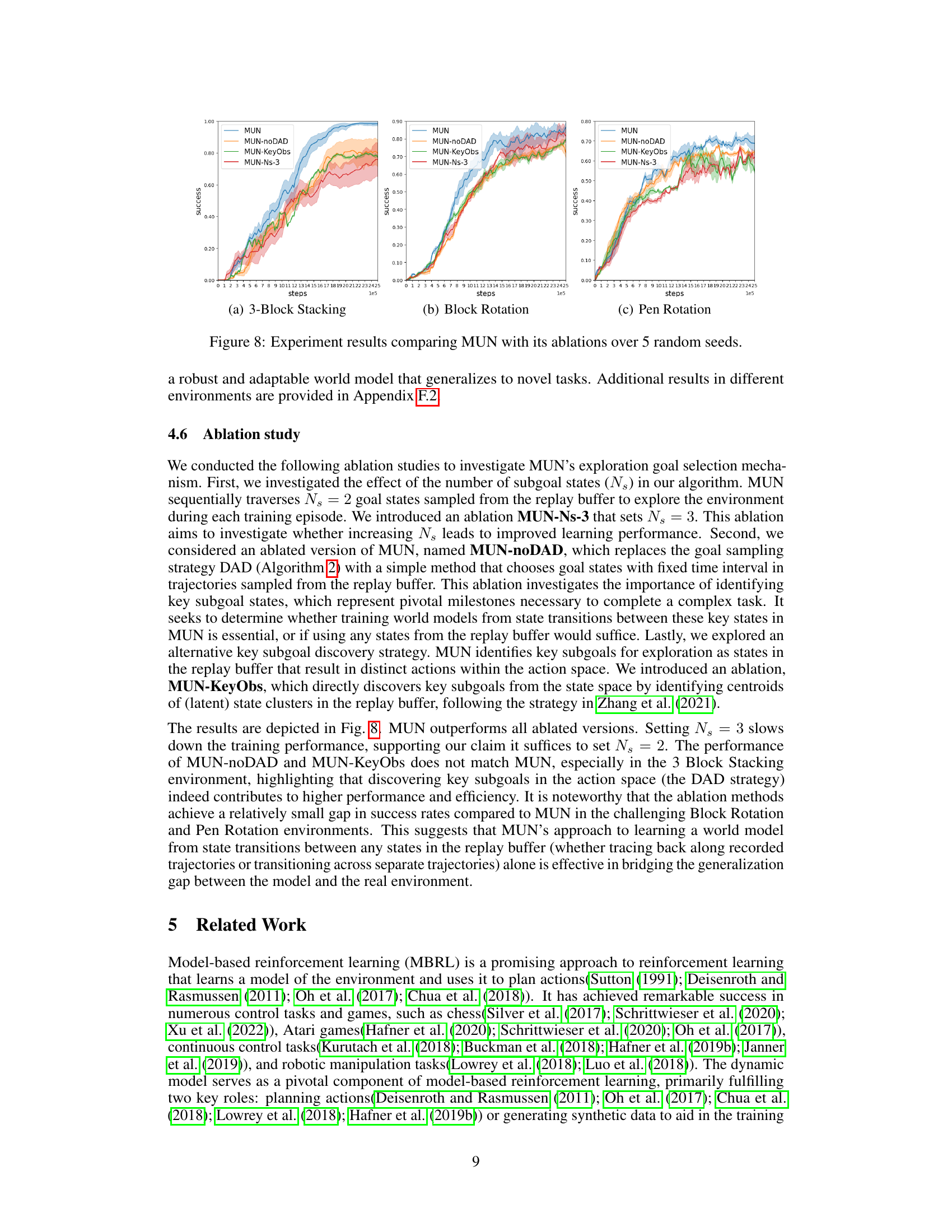

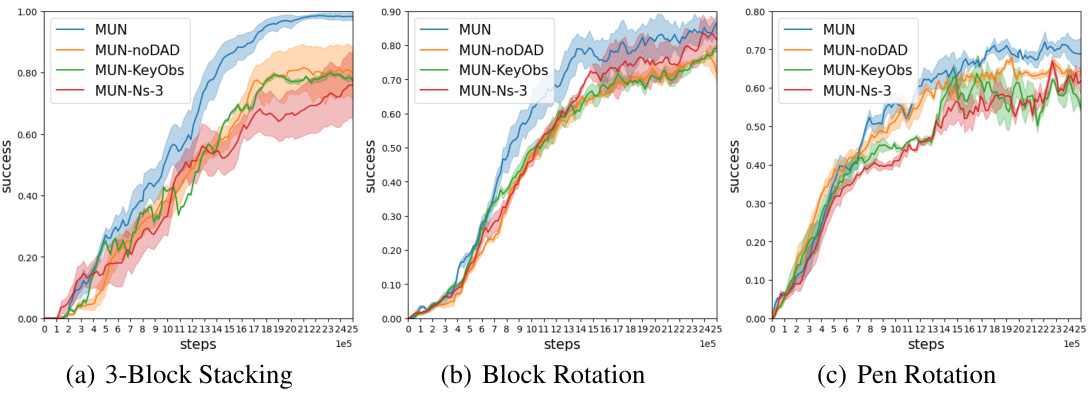

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contribution. In this context, it would involve removing parts of the MUN algorithm (e.g., DAD subgoal selection, bidirectional replay buffer) to gauge their effects on overall performance. Results would reveal whether these components are crucial for MUN’s success and highlight the extent to which each contributes to its effectiveness. By comparing results against the full model, researchers could quantify the impact of each component. Strong performance of the full model compared to its ablated versions would underscore the synergistic advantages of MUN’s design. Conversely, if performance degradation is minimal after removing a specific component, it may indicate that feature is redundant or that other mechanisms compensate for its absence. This analysis is important because it offers a deeper understanding of MUN’s strengths and weaknesses, informing future improvements and guiding the development of more efficient, streamlined architectures. It could reveal whether there’s room for simplification without significant performance loss, or if certain elements are absolutely critical for high performance and should be prioritized during optimization or further development.

More visual insights#

More on figures

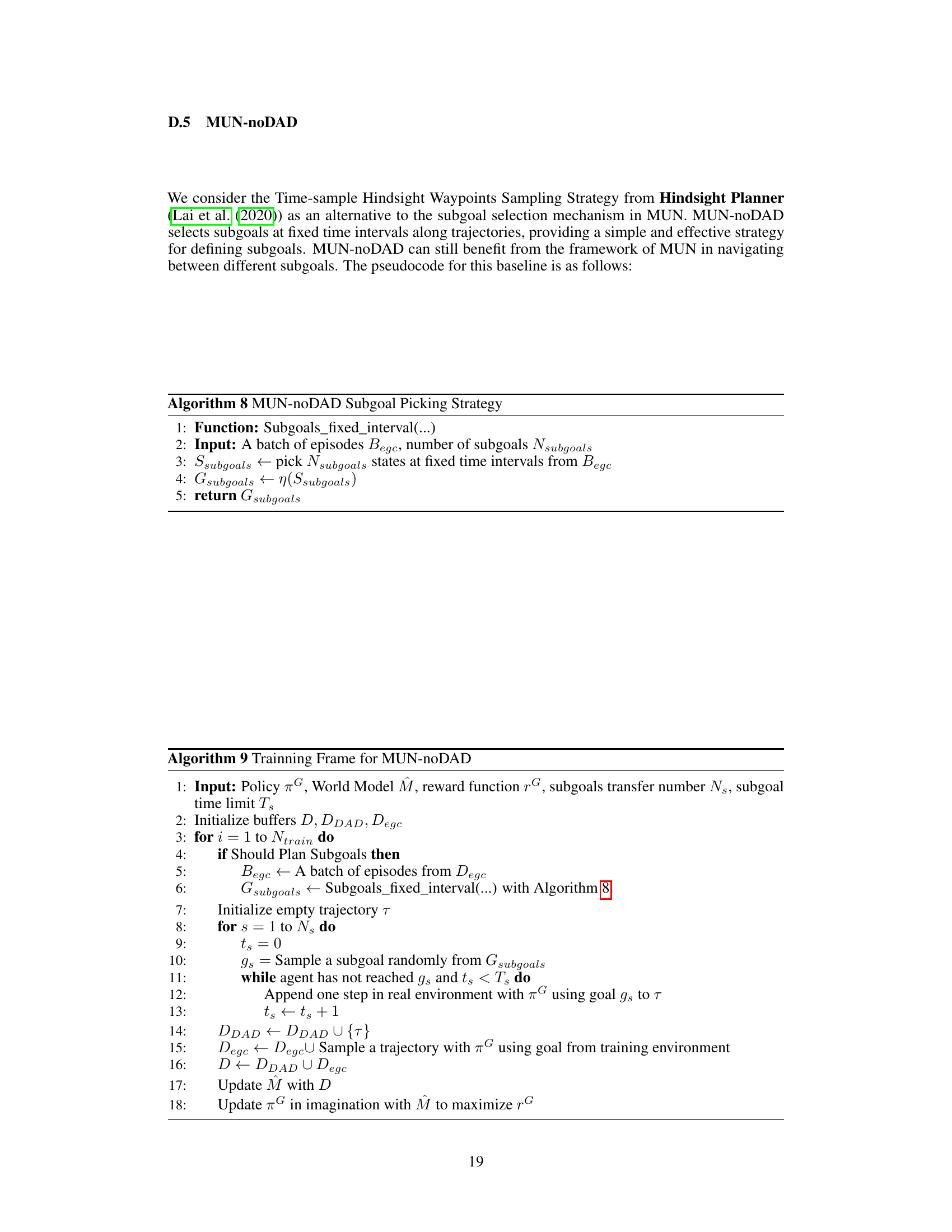

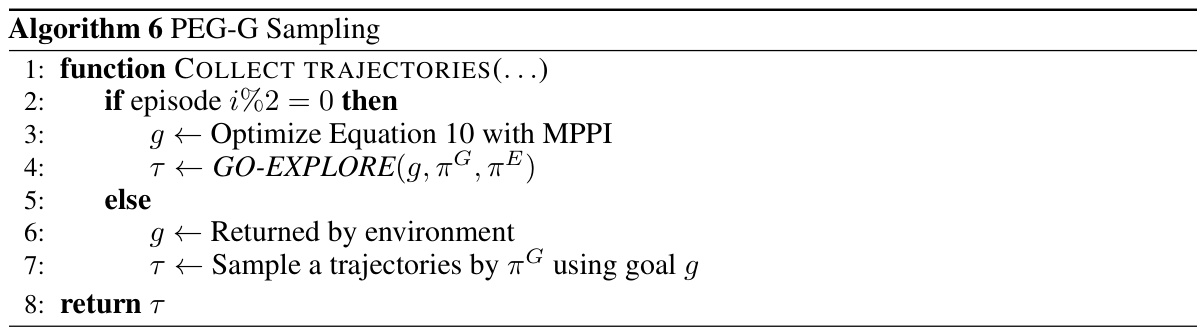

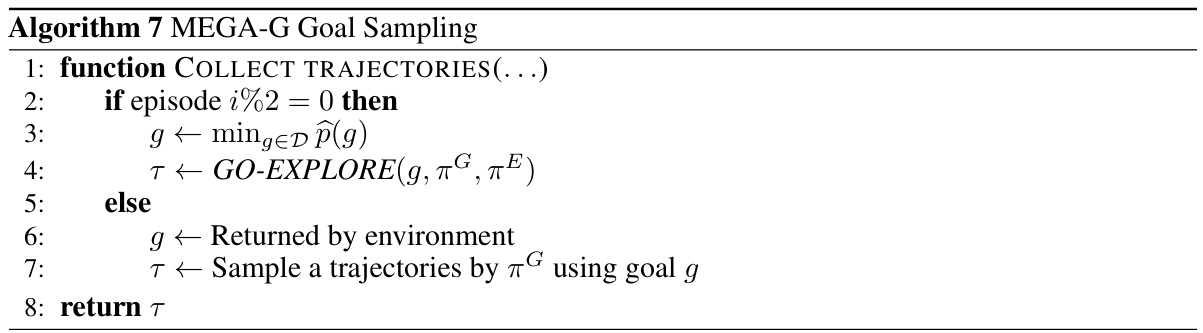

Figure 2(a) shows key states in a 3-block stacking task, highlighting the milestones in the process. Figure 2(b) compares the MUN’s bidirectional replay buffer with traditional unidirectional methods, emphasizing MUN’s ability to learn from both forward and backward transitions, leading to more robust world models.

This figure compares the traditional unidirectional replay buffer with the bidirectional replay buffer proposed by the authors. The unidirectional buffer only stores transitions from one state to the next, along the trajectory. This limits the world model’s ability to generalize to unseen states or state transitions in reverse. In contrast, the bidirectional buffer includes transitions between any two states (subgoals) found within the buffer, even across different trajectories. This enables the MUN algorithm to learn a world model that generalizes better to new scenarios and is more robust.

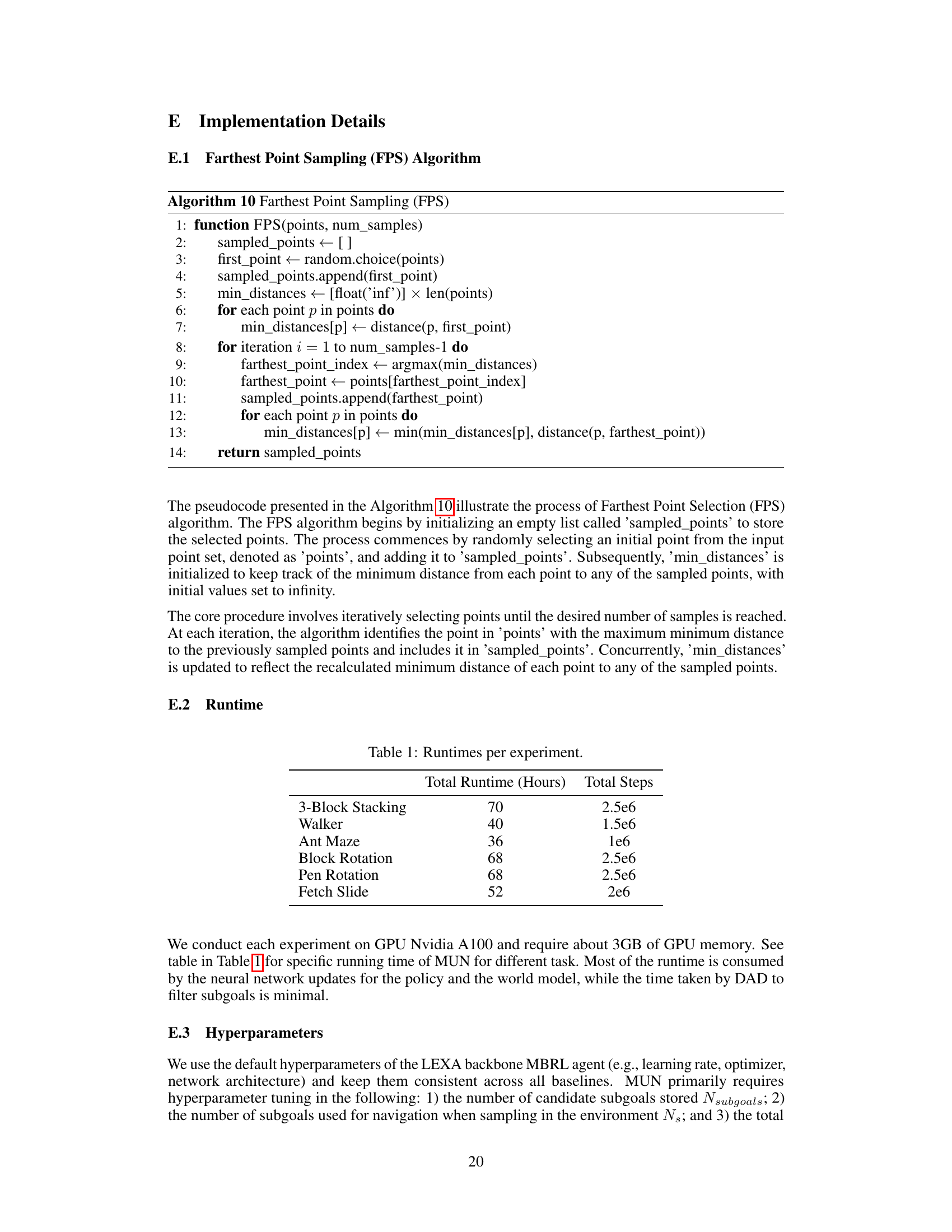

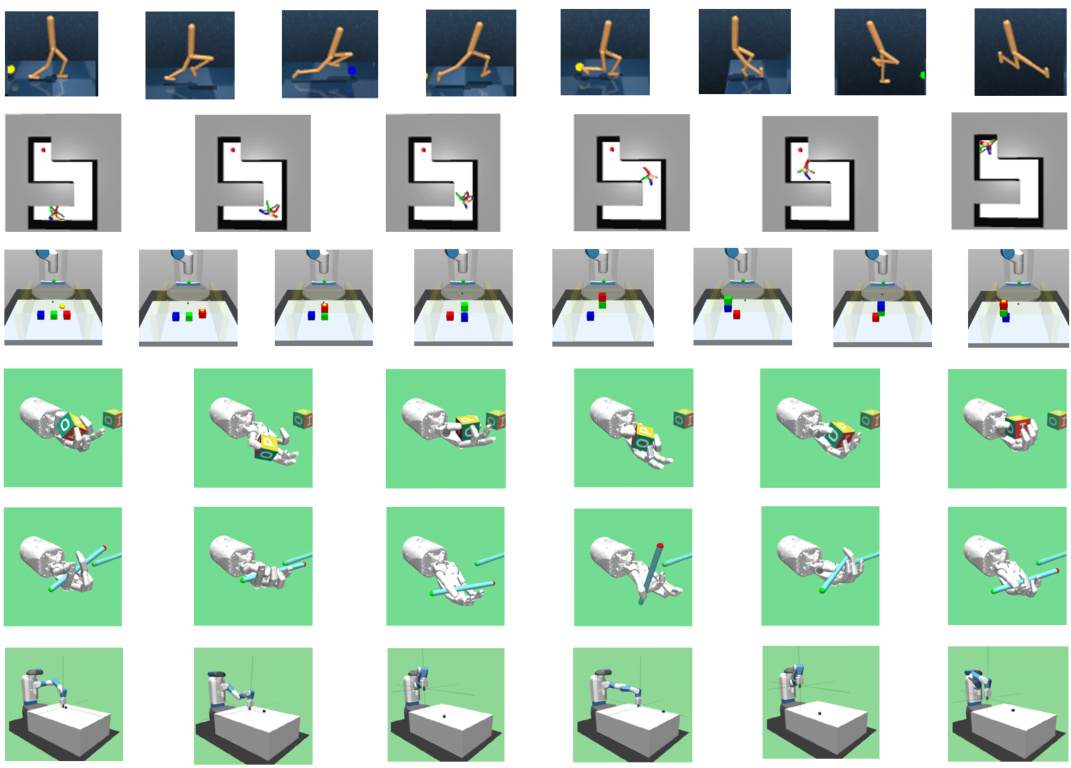

This figure shows six different simulated robotic environments used to evaluate the MUN algorithm. These environments present diverse challenges in terms of locomotion, manipulation, and control precision, offering a robust testbed for assessing the generalization capabilities of goal-conditioned policies learned by the MUN method. The environments include: Ant Maze (navigation), Walker (locomotion), 3-Block Stacking (manipulation), Pen Rotation (precise manipulation), Block Rotation (manipulation), and Fetch Slide (pushing).

This figure shows the six different robotics and navigation environments used to evaluate the MUN algorithm and compare its performance against baseline algorithms. Each environment presents unique challenges in terms of the agent’s locomotion, manipulation skills, and the complexity of the tasks. The environments range from navigating a maze (Ant Maze) to stacking blocks (3-Block Stacking) and performing precise manipulations (Pen Rotation and Block Rotation). The diversity of these tasks allows for a comprehensive assessment of MUN’s generalization capabilities across various scenarios.

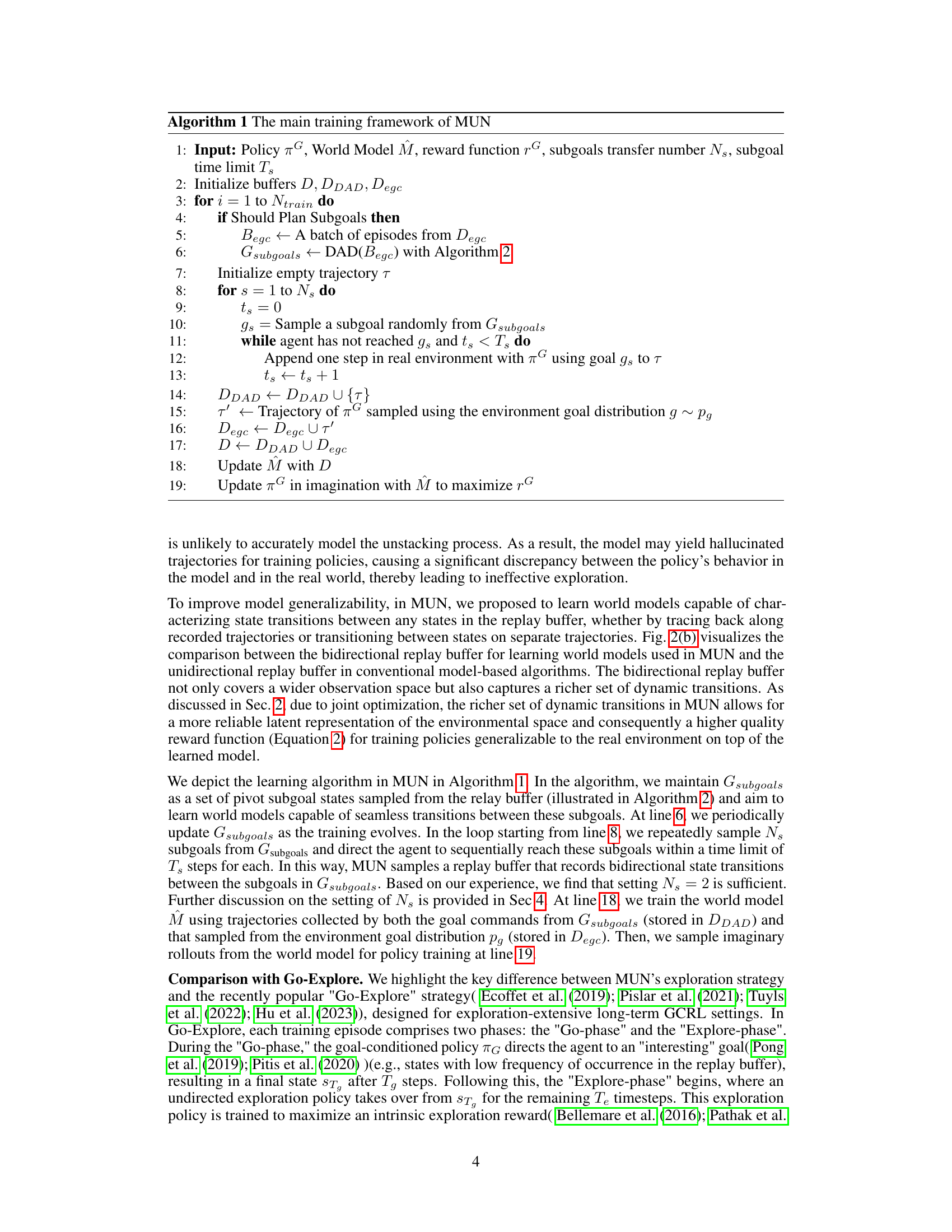

This figure presents the experimental results comparing the performance of the proposed MUN algorithm against several baseline methods across six different robotic manipulation and navigation tasks. The results are shown as graphs depicting the success rate over training steps (x-axis) for each method. Each graph represents a specific task (Ant Maze, Walker, 3-Block Stacking, Block Rotation, Pen Rotation, Fetch Slide). The shaded area represents the standard deviation over 5 random seeds. The results demonstrate MUN’s superior performance across all six tasks in terms of both final success rate and learning speed.

Figure 2(a) shows key states in a 3-block stacking task, highlighting the importance of subgoal identification in MUN. Figure 2(b) compares the MUN’s bidirectional replay buffer with traditional unidirectional buffers, illustrating MUN’s improved ability to capture state transitions in various directions for enhanced world model learning. The bidirectional buffer allows for learning state transitions from various perspectives, as demonstrated in the figure.

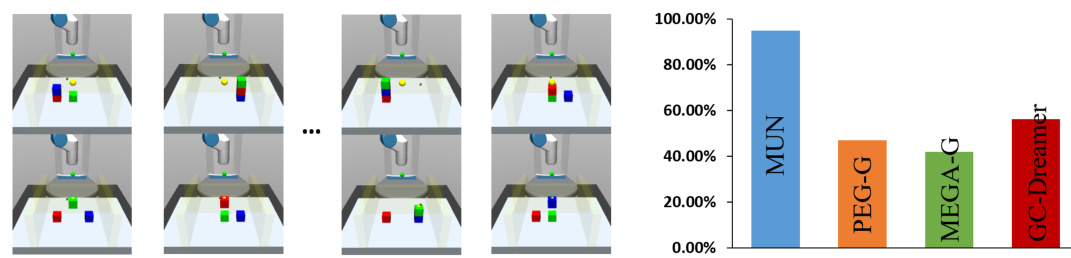

This figure shows an experiment to test the model’s ability to navigate between arbitrary subgoals in a 3-block stacking task. The left side shows the initial state (top) and target goal state (bottom) for each trial. The right side displays a bar graph comparing the success rate of MUN against several baseline methods in this navigation task. The high success rate of MUN in this challenging navigation task highlights its ability to generalize the learned world model to novel goal settings.

This figure shows six different simulated robotic environments used to evaluate the performance of the MUN algorithm. The environments vary in complexity and the type of robot control involved: * Ant Maze: A multi-legged ant robot navigating a maze. * Walker: A two-legged robot learning to walk. * 3-Block Stacking: A robotic arm stacking three blocks. * Block Rotation: A robotic arm rotating a block to a specific orientation. * Pen Rotation: A robotic arm rotating a pen to a specific orientation (more difficult due to the pen’s shape). * Fetch Slide: A robotic arm sliding a puck to a target location on a slippery surface. The figure provides visual examples of the robots and their tasks in each environment.

This figure shows six different simulated robotic environments used to test the performance of the proposed MUN algorithm. These environments present diverse challenges, including navigation (Ant Maze), locomotion (Walker), manipulation (3-Block Stacking, Block Rotation, Pen Rotation), and pushing (Fetch Slide). The image provides a visual representation of the complexity and variety of the tasks used in the experiments.

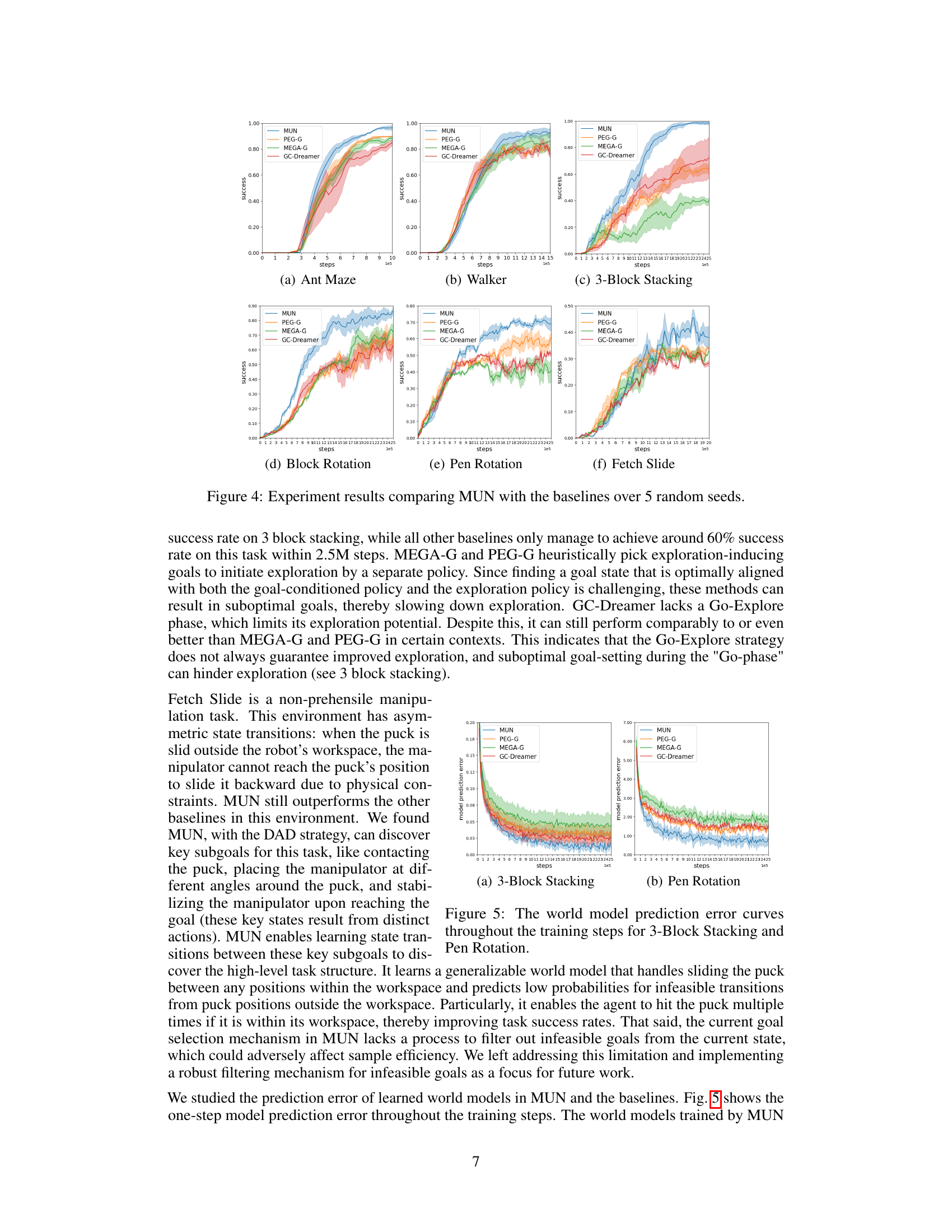

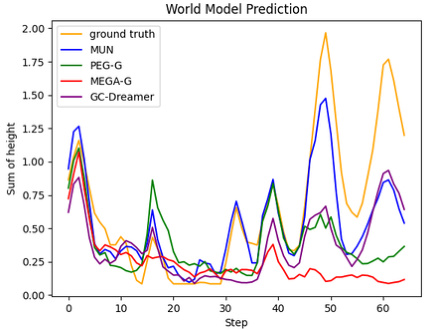

This figure compares the imagined and real trajectories generated by different world models for two tasks: 3-block stacking and block rotation. The plots show the sum of block heights and the x-position of the block, respectively, over time steps. MUN exhibits the smallest error compared to the ground truth trajectory, demonstrating the superior accuracy of its world model in predicting real-world dynamics.

This figure compares the imagined trajectories generated by different world models (MUN, PEG-G, MEGA-G, GC-Dreamer) against the ground truth trajectories in 3-Block Stacking and Block Rotation tasks. The plots show the prediction error over time steps. MUN consistently shows the lowest error, indicating better model accuracy and generalization.

More on tables

This table presents the multi-step prediction error of learned world models for different tasks. It shows the compounding error (accumulated error over multiple prediction steps) of various models (MUN, MUN-noDAD, PEG-G, MEGA-G, and GC-Dreamer) when generating simulated trajectories of the same length as real trajectories. Lower values indicate better model performance in accurately predicting the future states.

This table presents the one-step prediction error for learned world models across different environments and baselines (MUN, MUN-noDAD, PEG-G, MEGA-G, and GC-Dreamer). The error is calculated using a validation dataset of randomly sampled state-transition tuples from the replay buffers of each method. Lower values indicate better model accuracy in predicting the next state based on the current state and action.

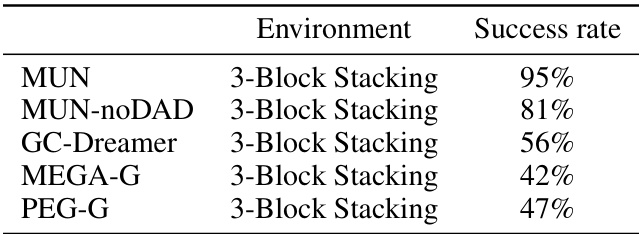

This table presents the success rates achieved by different algorithms (MUN, MUN-noDAD, GC-Dreamer, MEGA-G, and PEG-G) when performing navigation tasks in the 3-Block Stacking environment. The success rate is the percentage of times the algorithm successfully navigated from a randomly selected starting state to a randomly selected goal state within the environment. These results highlight the comparative performance of MUN and the effectiveness of its subgoal discovery method compared to other algorithms.

This table presents the one-step prediction error for each environment. The error is calculated as the mean squared error between the model’s prediction and the actual next state. Lower values indicate better model accuracy. The table compares the performance of the proposed MUN method against several baselines: MUN-noDAD, PEG-G, MEGA-G, and GC-Dreamer.

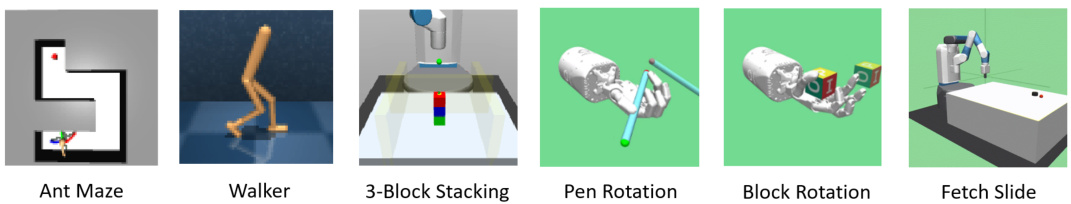

This table shows the total runtime in hours and the total number of steps for each of the six experiments conducted in the paper: 3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Block Rotation, Pen Rotation, and Fetch Slide. The runtimes provide a sense of the computational cost associated with training the models in each environment.

This table presents the runtime and total number of steps for each of the six experiments conducted in the paper. The experiments involved robotic manipulation and navigation tasks with varying complexities.

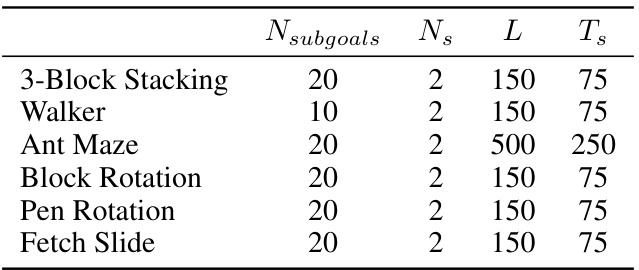

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the MUN algorithm for each of the six different environments. The hyperparameters include: *

Nsubgoals: The number of candidate subgoals stored. *Ns: The number of subgoals used for navigation when sampling in the environment. *L: The total episode length. *Ts: The maximum number of timesteps allocated for navigating to a specific subgoal.

This table presents the success rates achieved by different algorithms in navigation experiments conducted on the 3-Block Stacking environment. The algorithms compared include MUN, MUN-noDAD (an ablation of MUN), GC-Dreamer (a goal-conditioned Dreamer baseline), MEGA-G (a Go-Explore baseline), and PEG-G (another Go-Explore baseline). The success rate reflects the percentage of successful navigation attempts between arbitrary subgoals within this environment.

This table presents the success rates achieved by different algorithms in the Ant Maze navigation task. The algorithms compared are MUN, MUN-noDAD (a variant of MUN without the DAD subgoal selection method), GC-Dreamer (a goal-conditioned Dreamer baseline), MEGA-G (a Go-Explore baseline using MEGA’s goal selection), and PEG-G (a Go-Explore baseline using PEG’s goal selection). The results show the percentage of successful navigation attempts for each algorithm.

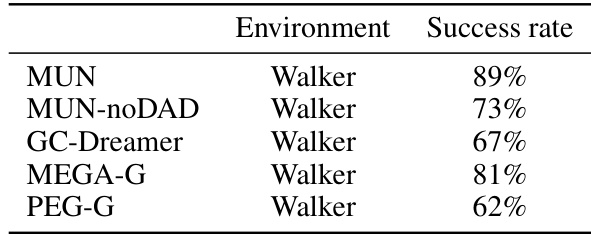

This table presents the success rates achieved by different algorithms (MUN, MUN-noDAD, GC-Dreamer, MEGA-G, and PEG-G) when performing navigation tasks in the Walker environment. The success rate is calculated as the percentage of successful navigation trials from a set of initial and goal positions. The results showcase the performance differences between MUN and its ablations (MUN-noDAD) and various baselines (GC-Dreamer, MEGA-G, and PEG-G), highlighting the impact of the MUN’s exploration strategy and the DAD method for subgoal discovery.

This table presents the one-step prediction error for various world models across different environments. The error is calculated as the mean squared error between the model’s prediction and the ground truth for a randomly sampled set of state transitions from the replay buffer. Lower values indicate better model accuracy in predicting the next state given the current state and action.

This table presents the multi-step prediction error for different learned world models across various tasks. The error is calculated by comparing the simulated trajectories generated by the models against the ground truth trajectories from the real environment. Lower values indicate better model generalization and prediction accuracy. The results show that the models trained by MUN generally have lower compounding errors compared to other baselines across all tasks.

Full paper#