↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

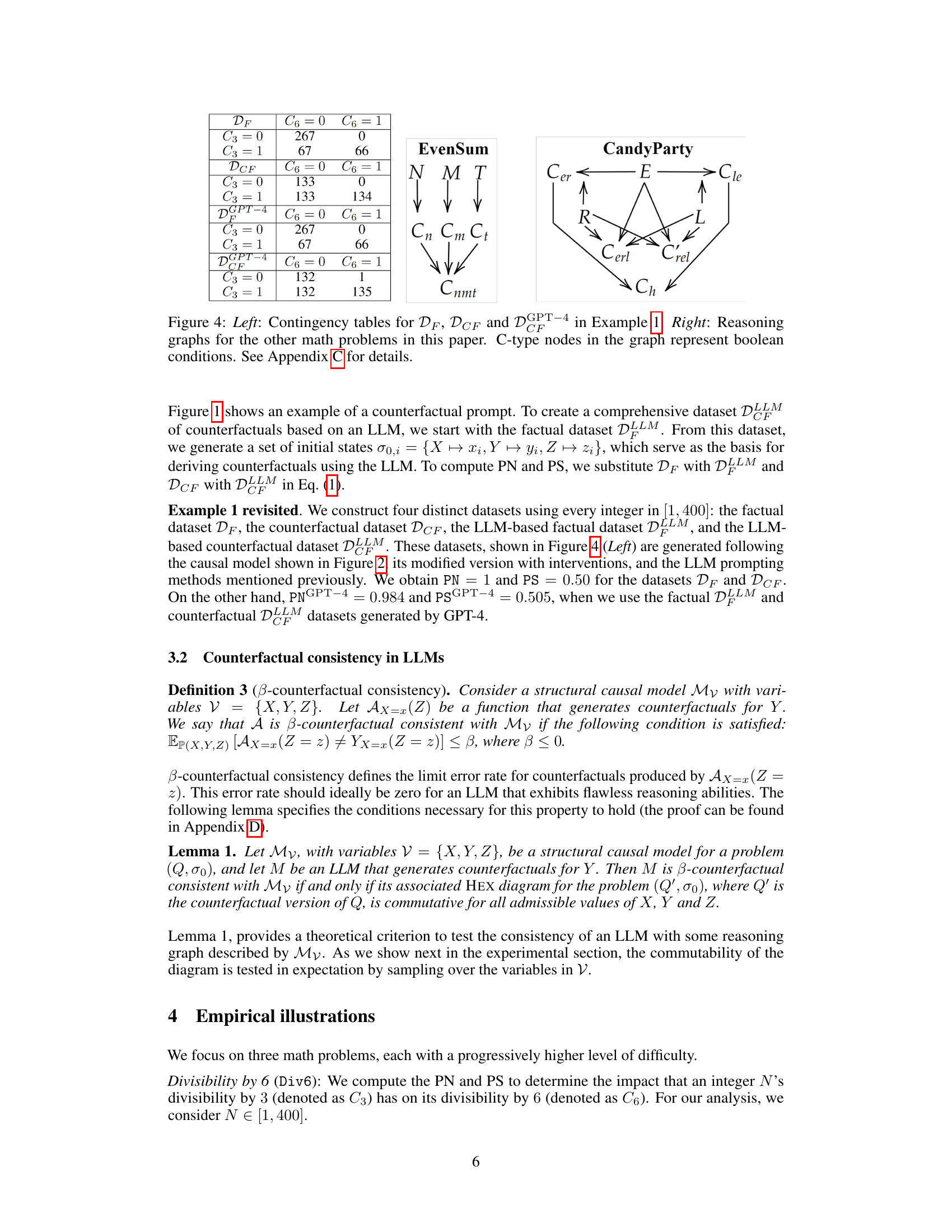

Current research on Large Language Models (LLMs) is often limited to evaluating their performance on specific tasks without fully understanding their underlying reasoning abilities. This paper aims to assess the reasoning capacity of LLMs by examining their understanding of cause-and-effect relationships, using concepts from causality and probability theory. A key challenge is distinguishing actual reasoning from statistical pattern recognition. This is addressed by evaluating the models’ ability to handle counterfactual scenarios, a crucial aspect of human reasoning.

The paper proposes a novel framework that uses probabilities of necessity and sufficiency to systematically evaluate LLMs’ reasoning. This is implemented by creating factual and counterfactual datasets, testing these with various LLMs, and comparing against the actual results. The experiments reveal that while LLMs exhibit impressive accuracy in solving factual problems, they often fail when confronted with counterfactual scenarios. This provides a more comprehensive measure of reasoning ability than simply measuring accuracy on given tasks. The research concludes by exploring the implications for future LLM development and applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers because it introduces a novel framework for evaluating the reasoning capabilities of LLMs, addressing a critical gap in the field. By using probabilistic measures of causation, the research offers a more nuanced understanding of LLM reasoning, moving beyond simple accuracy assessments. This opens new avenues for investigating the limits of current LLMs and for developing more sophisticated models capable of genuine reasoning. The findings are broadly relevant to researchers across various AI subfields, including causality, knowledge representation, and cognitive science.

Visual Insights#

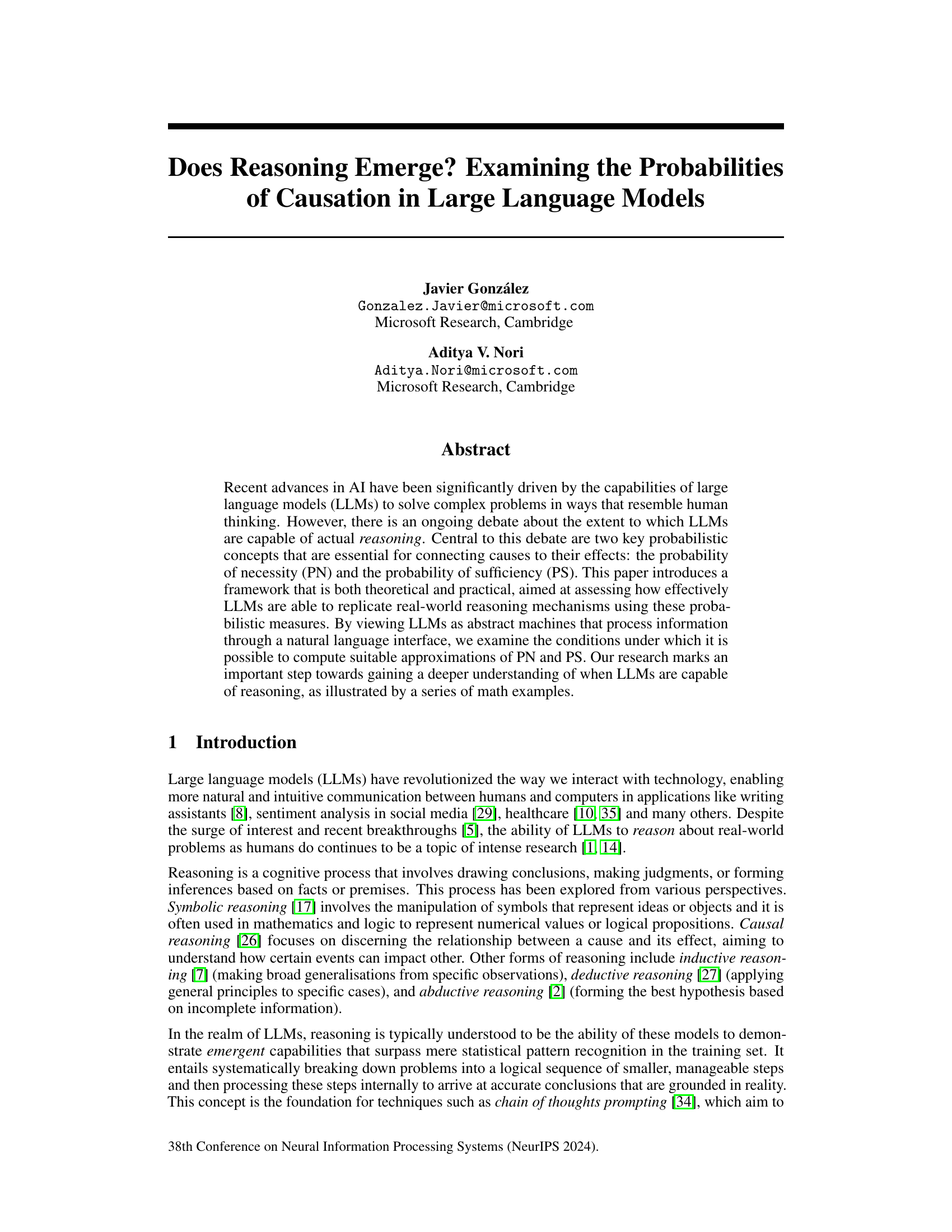

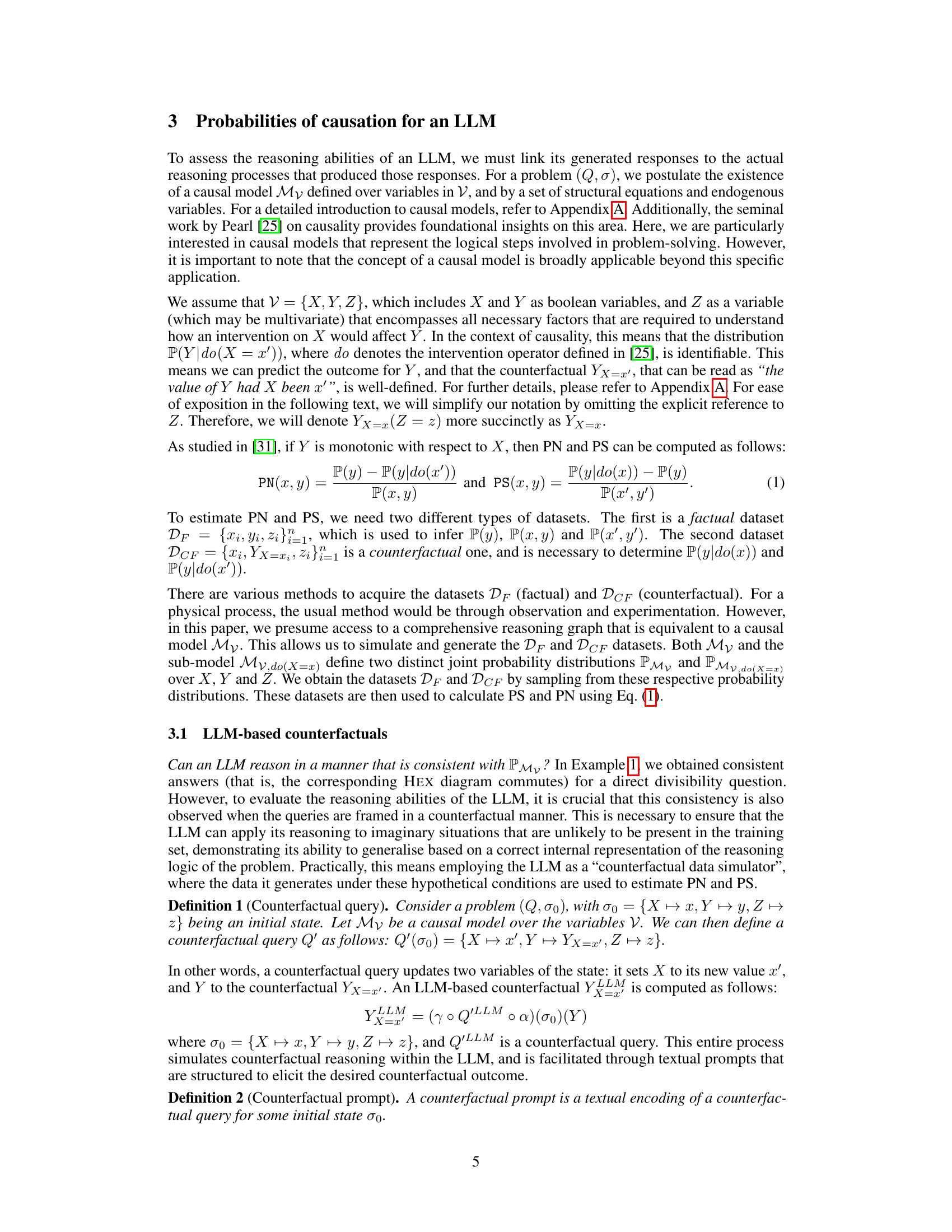

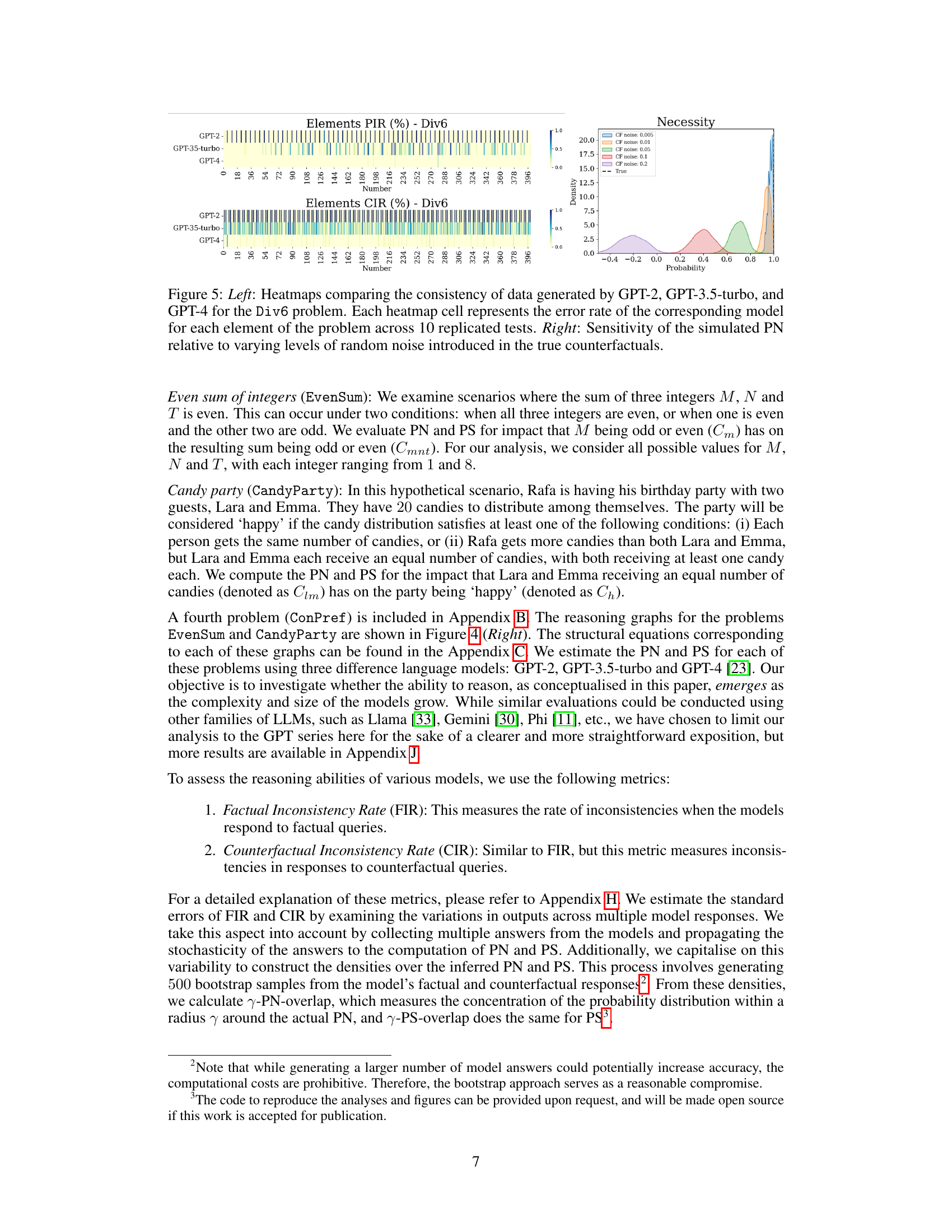

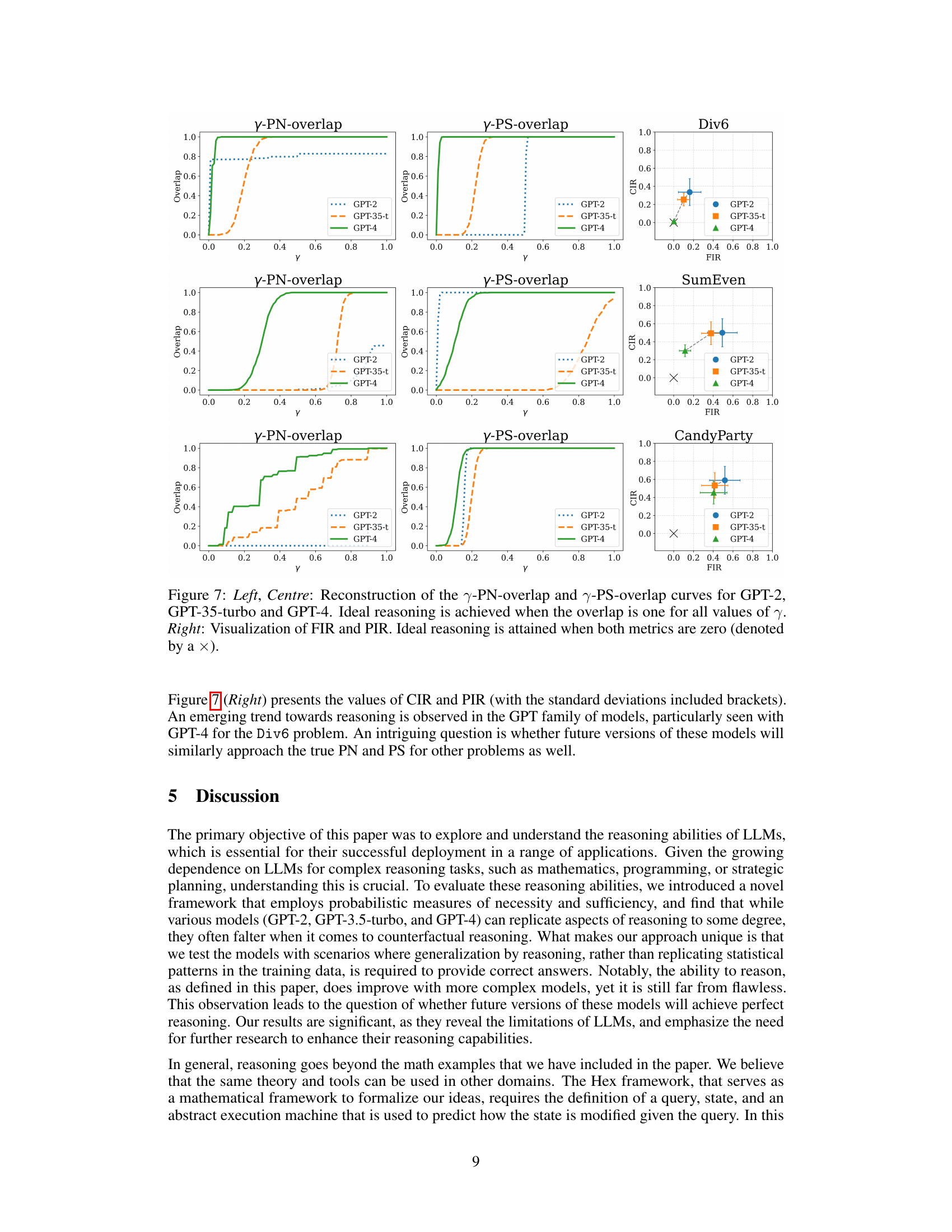

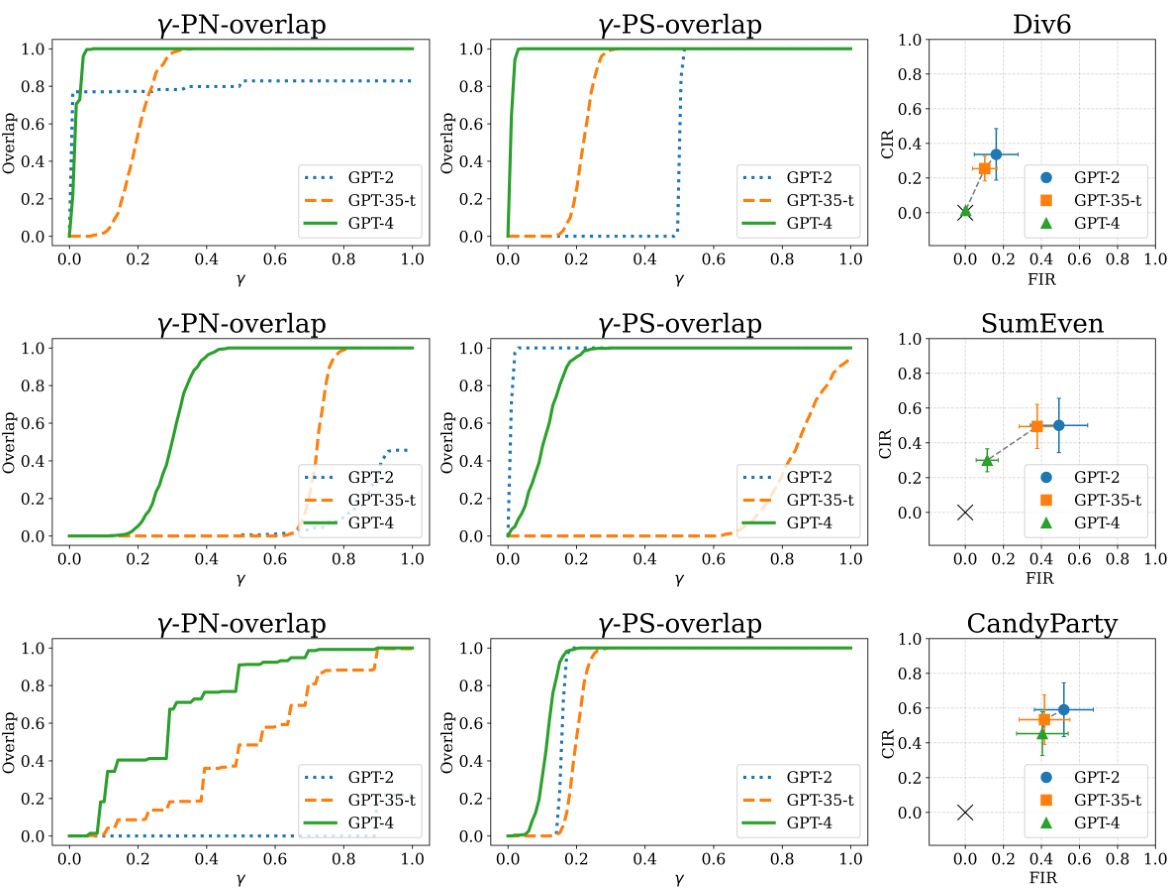

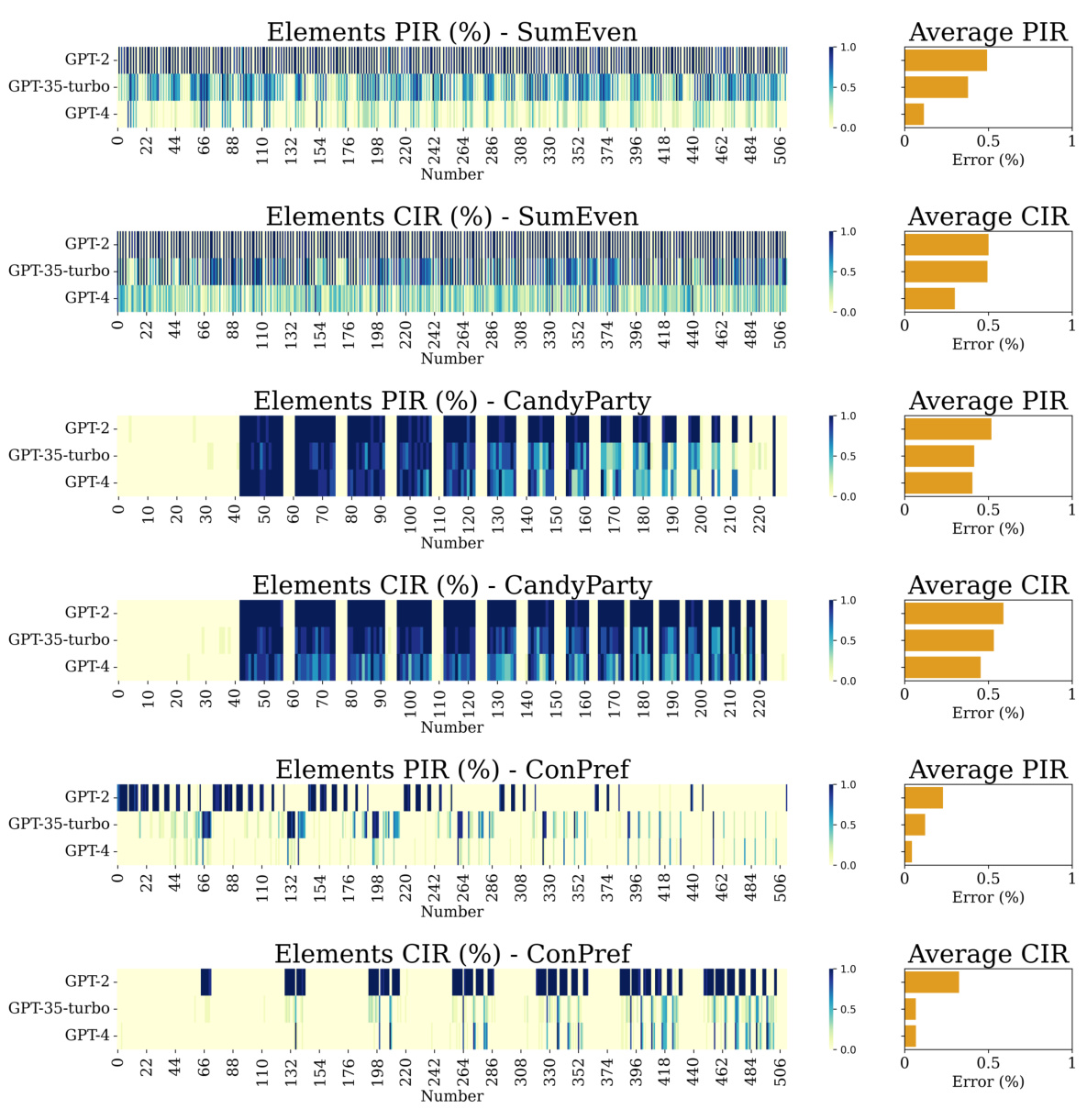

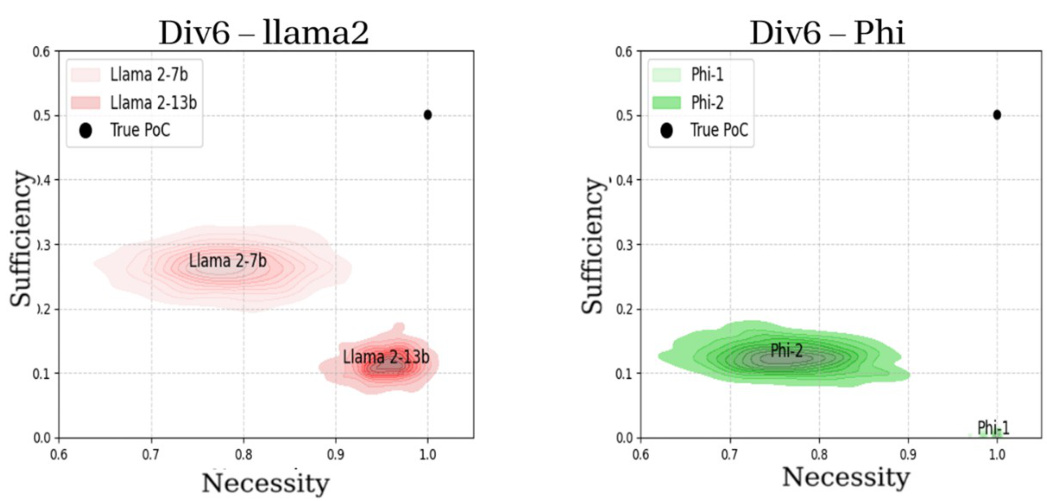

This figure shows the error rates of three different language models (GPT-2, GPT-3.5-turbo, and GPT-4) when answering simple arithmetic questions about divisibility by 6. Two types of questions were used: direct questions simply asked if a number was divisible by 6; counterfactual questions introduced a hypothetical change (assuming the number had 3 as a prime factor). The results reveal that all models perform much better on the direct questions, showcasing a significant difference in their ability to handle counterfactual reasoning, especially GPT-3.5-turbo.

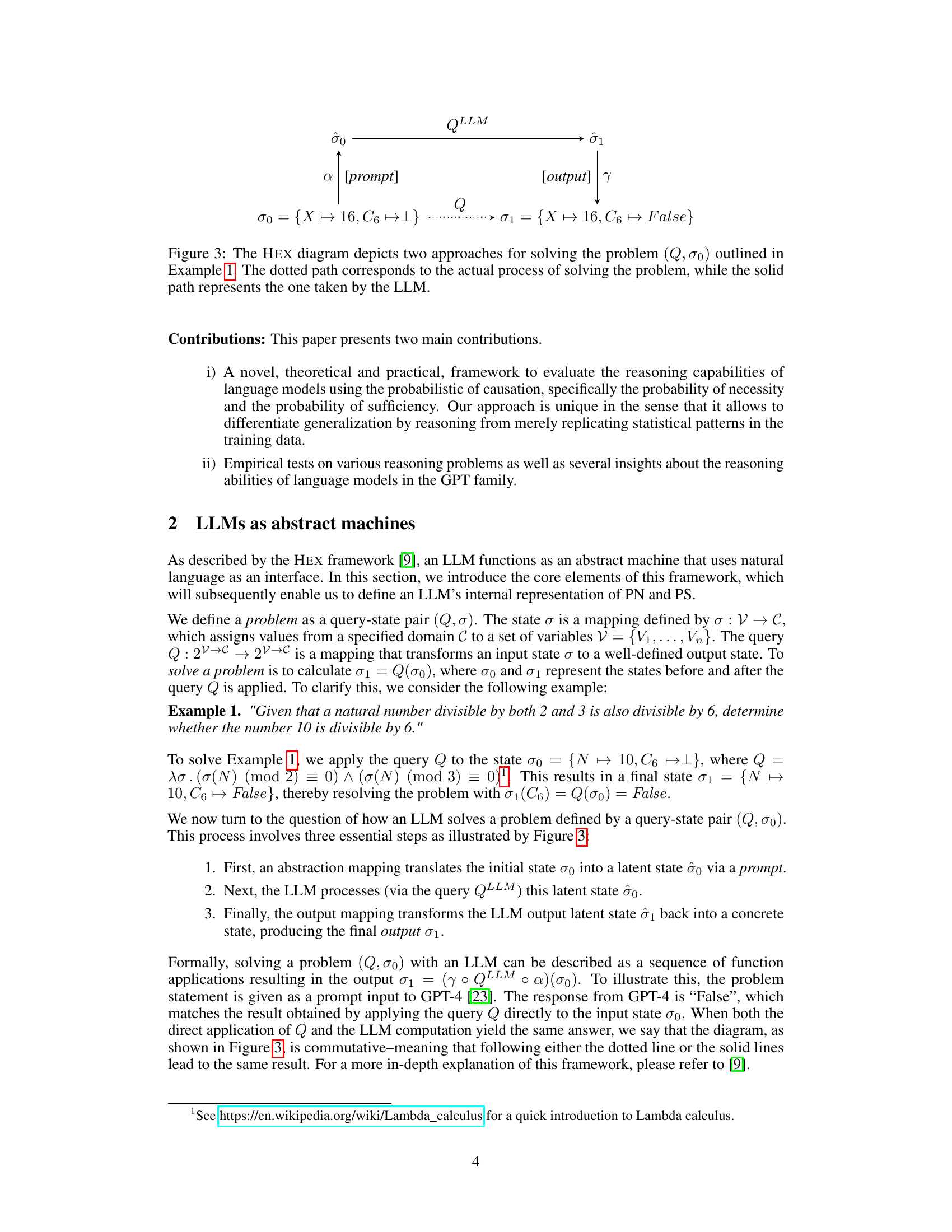

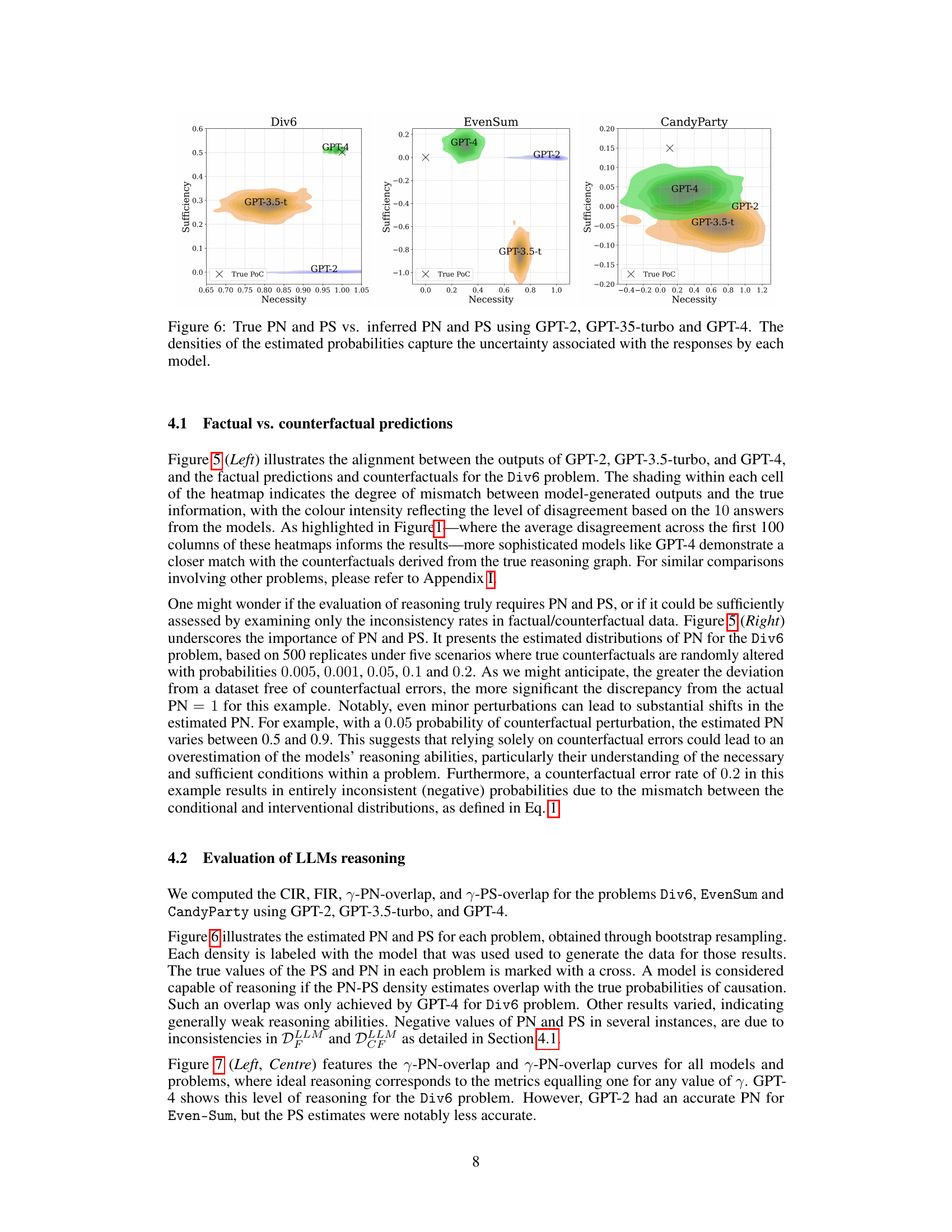

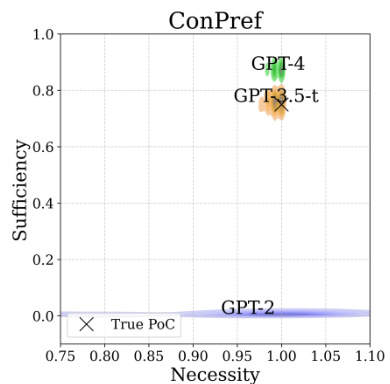

This figure shows the true probabilities of necessity (PN) and sufficiency (PS) for three different reasoning problems compared against the probabilities estimated using three different GPT models. The results show that the more advanced GPT-4 model produces estimates closer to the true values than earlier models, indicating some improvement in reasoning abilities with more advanced models. Note that the densities are calculated via bootstrap resampling, reflecting uncertainty in the LLM generated outputs.

In-depth insights#

Causal Reasoning in LLMs#

The capacity of Large Language Models (LLMs) to engage in causal reasoning is a complex and actively debated topic. While LLMs excel at identifying correlations within vast datasets, true causal understanding requires the ability to reason about counterfactuals—what would have happened if a cause had been different. This involves more than simple pattern recognition; it necessitates inferring causal mechanisms and their probabilistic nature. Research into causal reasoning in LLMs often focuses on evaluating the models’ performance on tasks involving probabilistic causality, such as calculating the probability of necessity and sufficiency. These metrics offer a way to assess whether the LLM is truly understanding the underlying causal structure or simply memorizing statistical associations. Current findings suggest that while LLMs show promise, their ability to reason about causality remains limited. They often struggle with counterfactual scenarios, failing to generate predictions consistent with true causal models. This limitation highlights a critical gap between correlation and causation in current LLM architectures. Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated methods for evaluating causal understanding and designing models capable of robust causal inference.

Probabilistic Causation#

The concept of probabilistic causation, as discussed in the context of large language models (LLMs), explores how these models handle cause-and-effect relationships. It moves beyond simple correlation by considering the probability of necessity (PN) and the probability of sufficiency (PS). PN quantifies how likely a cause is essential for an effect, while PS assesses the likelihood of a cause being enough to produce the effect. Real-world reasoning often involves both PN and PS, and evaluating LLMs’ ability to incorporate these probabilistic measures is crucial for determining their true reasoning capabilities. The framework presented enables a deeper understanding of when LLMs merely mimic statistical patterns and when they demonstrate genuine causal reasoning. The research highlights the need to move beyond evaluating only accuracy in solving problems and to examine the understanding of underlying causal mechanisms. This probabilistic lens offers a more nuanced and comprehensive assessment of LLMs’ abilities, surpassing simpler metrics based solely on correctness.

LLM Reasoning Tests#

Evaluating Large Language Model (LLM) reasoning capabilities requires careful design of tests that move beyond simple pattern recognition. Effective LLM reasoning tests must assess the model’s ability to handle complex, multi-step problems that demand logical inference and the application of learned knowledge in novel situations. Such tests should include scenarios that require counterfactual reasoning, evaluating the model’s capacity to reason about hypothetical situations not explicitly present in its training data. The inclusion of both factual and counterfactual questions is crucial to avoid overestimating the LLM’s abilities, as models might perform well on familiar tasks while failing under more complex, less-predictable conditions. A robust evaluation framework should incorporate various reasoning types, including deductive, inductive, and abductive reasoning, to obtain a thorough understanding of the model’s reasoning prowess. Quantitative metrics are essential for evaluating model performance, providing objective measurements for comparison and progress tracking. Ideally, these metrics should not only measure accuracy but also assess the reasoning process itself, providing insights into how the model arrives at its conclusions. Ultimately, the goal is to create LLM reasoning tests that can reliably distinguish true reasoning abilities from the sophisticated pattern-matching capabilities often mistaken for reasoning.

Counterfactual Analysis#

Counterfactual analysis, in the context of this research paper, is a crucial methodology for evaluating the reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs). It moves beyond simply assessing an LLM’s ability to produce correct answers (correlations) by exploring its capacity to reason about hypothetical scenarios not present in its training data. This is achieved by creating counterfactual datasets where specific input conditions are altered, allowing researchers to observe how the LLM’s responses change. The core of this analysis lies in comparing the LLM’s counterfactual predictions with the actual counterfactual outcomes derived from a known causal model. Discrepancies reveal limitations in the LLM’s understanding of causal relationships and its ability to perform genuine reasoning. This approach enables a nuanced assessment that distinguishes between LLMs that merely mimic statistical patterns and those that truly grasp the underlying logical structure and causal mechanisms of a problem. The probability of necessity (PN) and probability of sufficiency (PS) emerge as key probabilistic measures used to quantify and analyze the LLM’s reasoning performance. By comparing the LLM-estimated PN and PS with their actual values, researchers gain a deeper understanding of the LLM’s strengths and weaknesses in causal reasoning, thereby providing valuable insights for improving these models’ reasoning abilities.

Reasoning’s Limits#

The concept of “Reasoning’s Limits” in the context of large language models (LLMs) centers on the inherent constraints of their probabilistic nature. LLMs excel at pattern recognition and statistical prediction, but this strength simultaneously represents a limitation when it comes to genuine reasoning. They lack the capacity for genuine causal understanding, often failing to grasp counterfactuals and nuanced probabilistic reasoning such as necessity and sufficiency. While chain-of-thought prompting shows some progress, it does not fundamentally solve this core limitation. The probabilistic nature means LLMs often generate outputs with high confidence, even when the underlying reasoning is flawed or based on spurious correlations. Therefore, applying LLMs to tasks requiring true reasoning, especially those with significant real-world consequences, needs careful consideration of their limitations and potential for unreliable outputs. Developing methods to robustly assess an LLM’s reasoning abilities, particularly its ability to handle counterfactuals, is crucial to determining their capabilities and limitations.

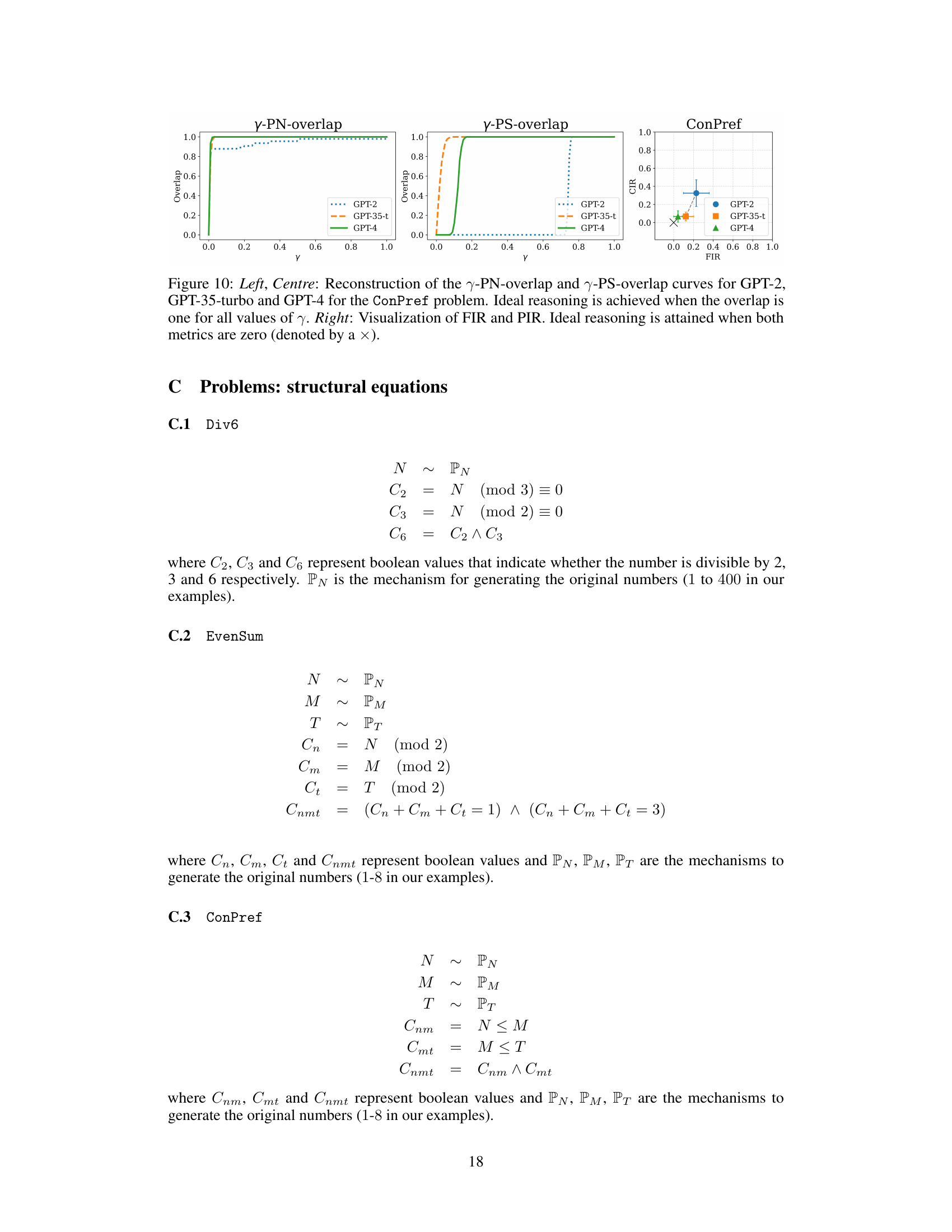

More visual insights#

More on figures

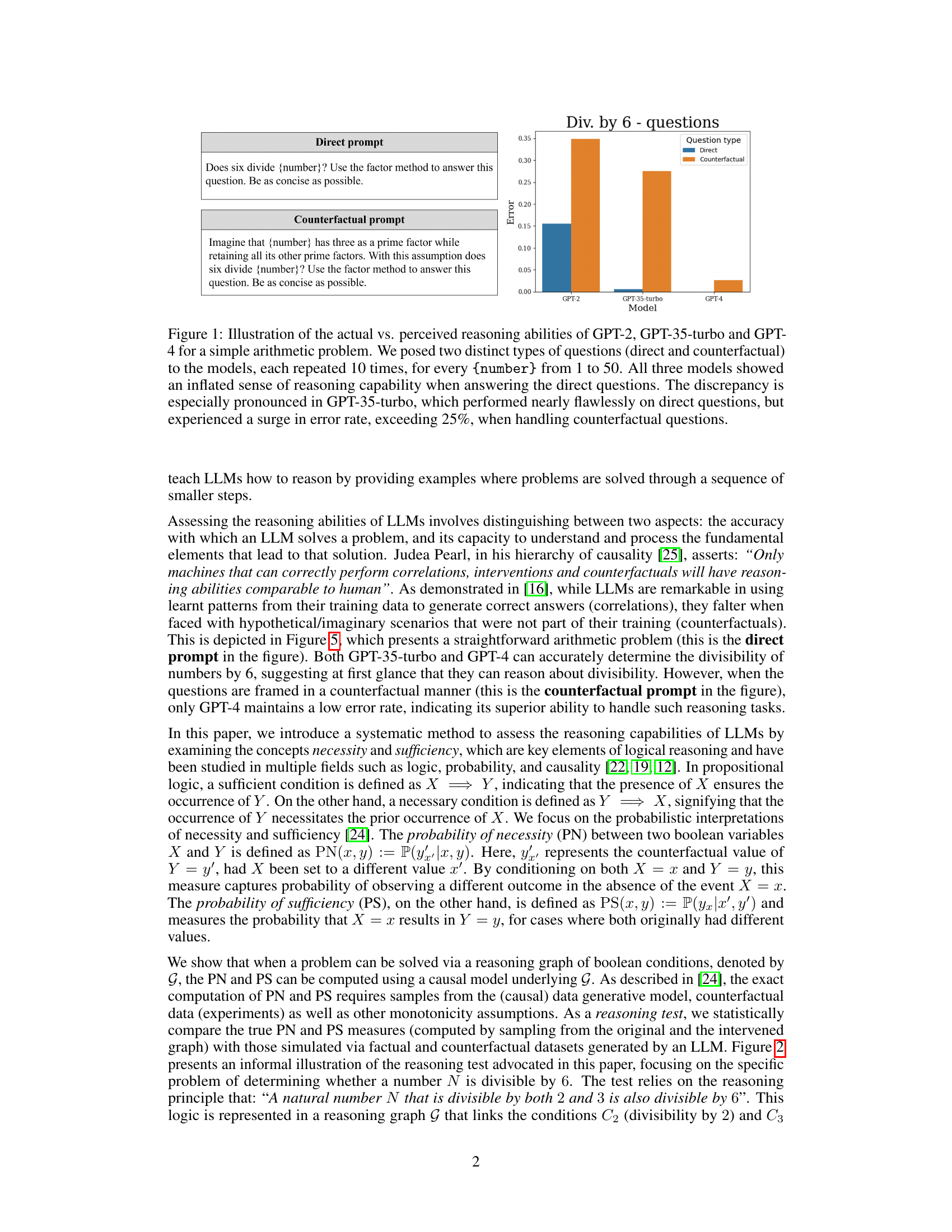

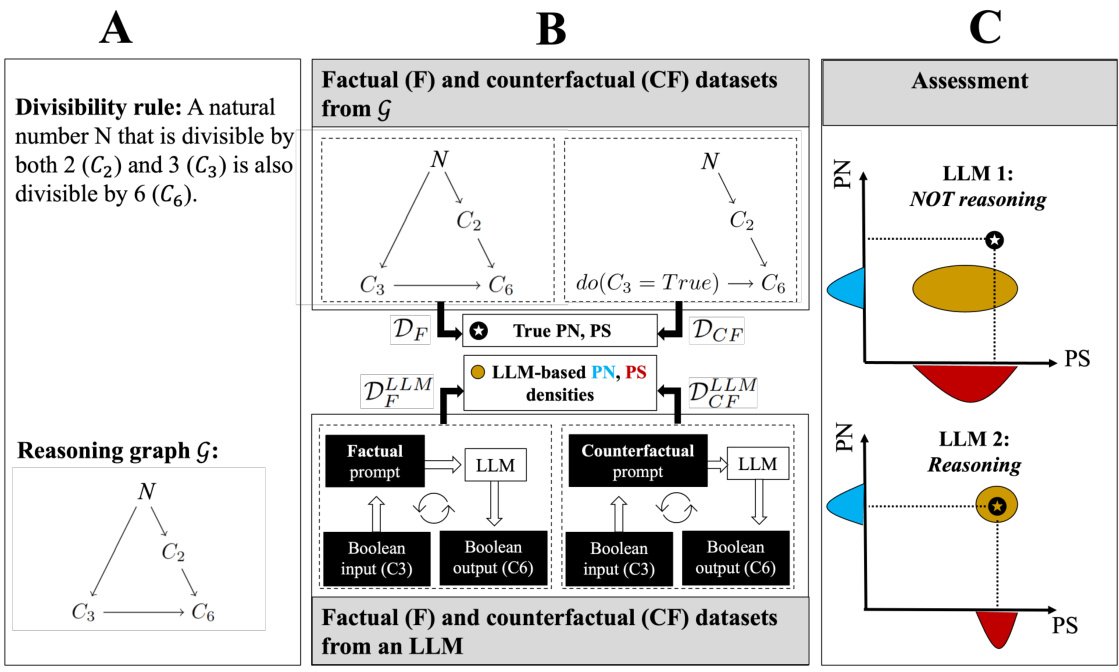

This figure illustrates a three-part framework for evaluating the reasoning capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) using the concepts of probability of necessity (PN) and probability of sufficiency (PS). Part A shows the divisibility rule for 6 and its corresponding reasoning graph. Part B details the process of generating factual and counterfactual datasets from both the true reasoning graph and the LLM’s responses to prompts based on this graph. Part C shows how to assess the LLM’s reasoning by comparing the PN and PS values derived from the LLM’s generated data to the true PN and PS values obtained from the factual and counterfactual datasets. The comparison helps determine if the LLM truly understands the underlying logic or merely replicates statistical patterns.

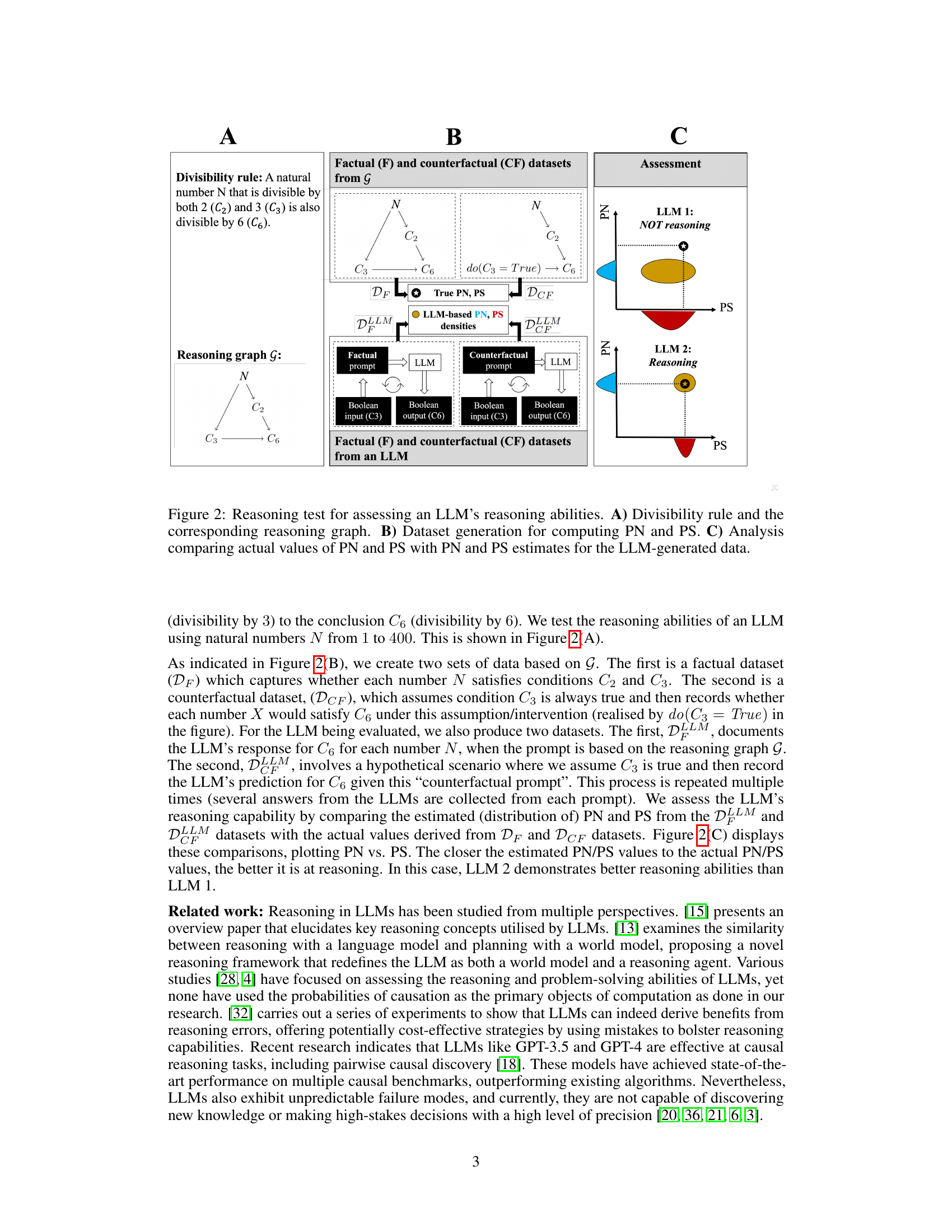

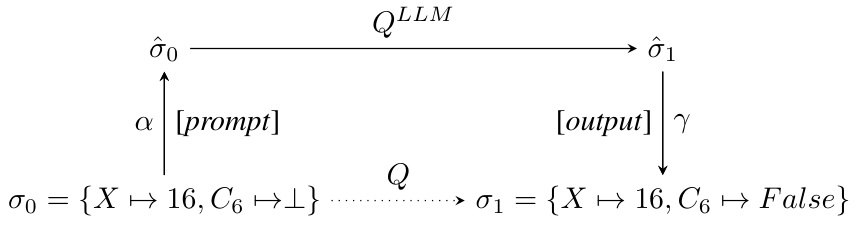

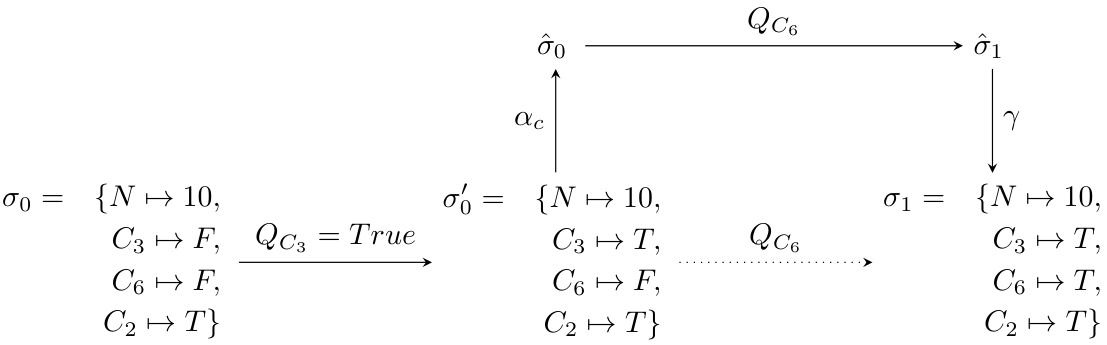

This figure illustrates the HEX (Heterogeneous Execution) framework for understanding how LLMs solve problems. It shows a query-state pair (Q,σ₀), representing a problem and its initial state. The dotted line represents the ideal solution process, while the solid line shows how an LLM approaches the problem. The LLM uses a prompt (α) to transform the initial state (σ₀) into a latent state (ô₀), processes it using Q_LLM (LLM’s internal query process), then transforms the resulting latent state (ô₁) back into a concrete output state (σ₁) using an output mapping (γ). The diagram highlights the difference between the ideal and LLM-based solution paths.

This figure illustrates a reasoning test to evaluate LLMs’ reasoning abilities using the concepts of probability of necessity (PN) and probability of sufficiency (PS). It breaks down the process into three parts: A) Defines a divisibility rule (if a number is divisible by both 2 and 3, it’s divisible by 6) and its corresponding reasoning graph. B) Shows how to generate factual and counterfactual datasets from the reasoning graph. Factual data reflects actual scenarios, while counterfactual data explores what happens if a condition is hypothetically changed. C) Explains how to assess an LLM’s reasoning by comparing its PN and PS estimates (derived from the LLM-generated data) to the actual PN and PS values obtained from the factual and counterfactual datasets.

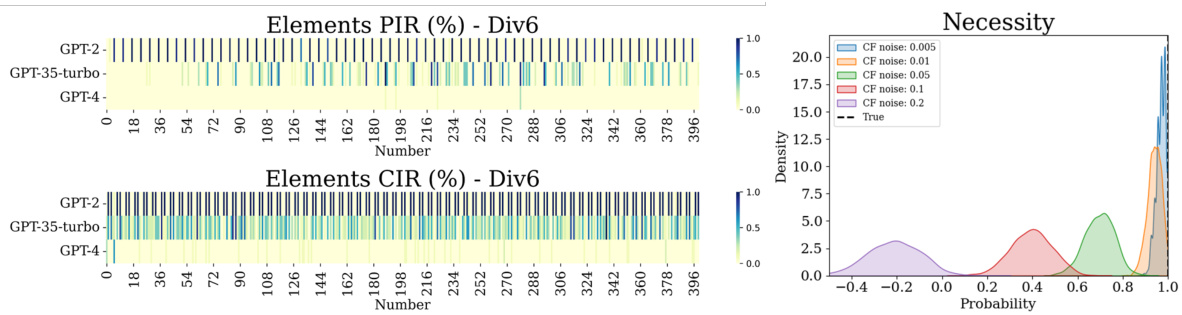

The figure shows two parts. The left part presents heatmaps that illustrate the consistency of data generated by three different language models (GPT-2, GPT-3.5-turbo, and GPT-4) for the Div6 problem. Each heatmap visualizes the error rate of a model for each element of the problem across ten replicated tests. The right part of the figure displays how sensitive the simulated probability of necessity (PN) is to the introduction of random noise into the true counterfactual data. It shows that even small amounts of noise can significantly affect the estimated PN.

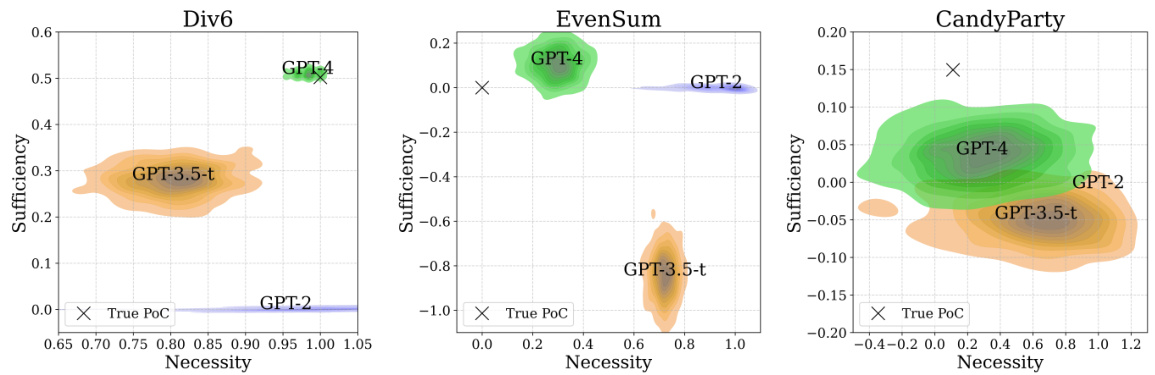

This figure compares the true probabilities of necessity (PN) and sufficiency (PS) with those estimated using three different language models (GPT-2, GPT-3.5-turbo, and GPT-4) across three different mathematical problems. The densities of the estimated probabilities are shown, reflecting the uncertainty associated with model responses. The closeness of the estimated distributions to the actual PN and PS values indicates the models’ reasoning abilities. A closer alignment suggests better reasoning capabilities.

This figure compares the true probabilities of necessity (PN) and sufficiency (PS) against those estimated using three different language models: GPT-2, GPT-3.5-turbo, and GPT-4. The heatmaps show the densities of the estimated probabilities, illustrating the uncertainty inherent in the models’ responses. Each model’s estimates are plotted against the true values of PN and PS for comparison, allowing for the assessment of the models’ reasoning abilities.

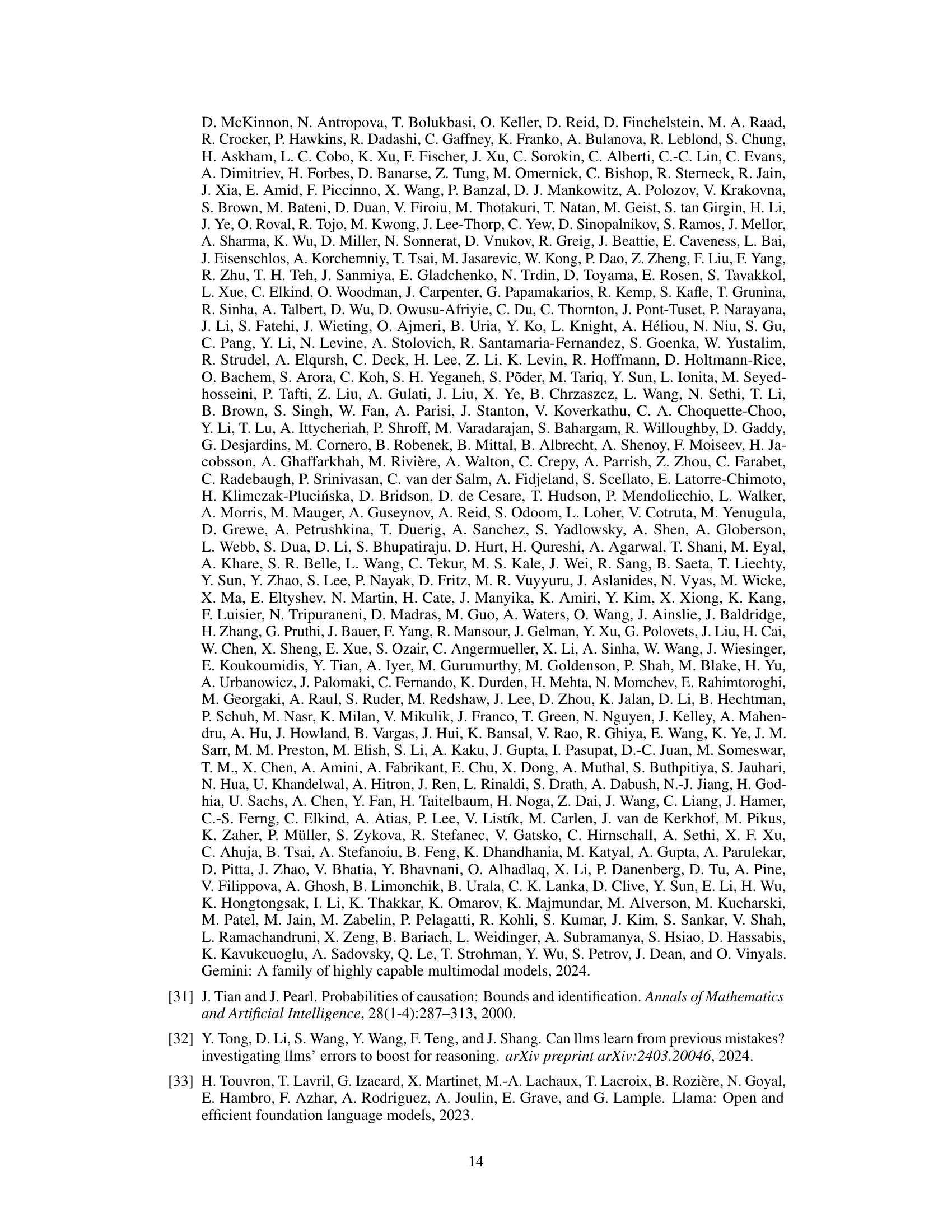

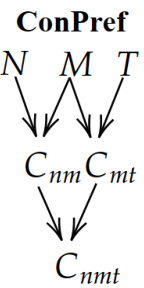

This figure shows the causal graph representing the logical steps involved in solving the ConPref problem. The nodes represent boolean variables (conditions), and the arrows indicate causal relationships. The graph shows how the conditions Cnm (N ≤ M) and Cmt (M ≤ T) causally influence the final condition Cnmt (N ≤ T). This graph is used in the paper to assess the reasoning capabilities of LLMs by comparing simulated probabilistic measures (Probability of Necessity and Probability of Sufficiency) with actual values derived from the graph.

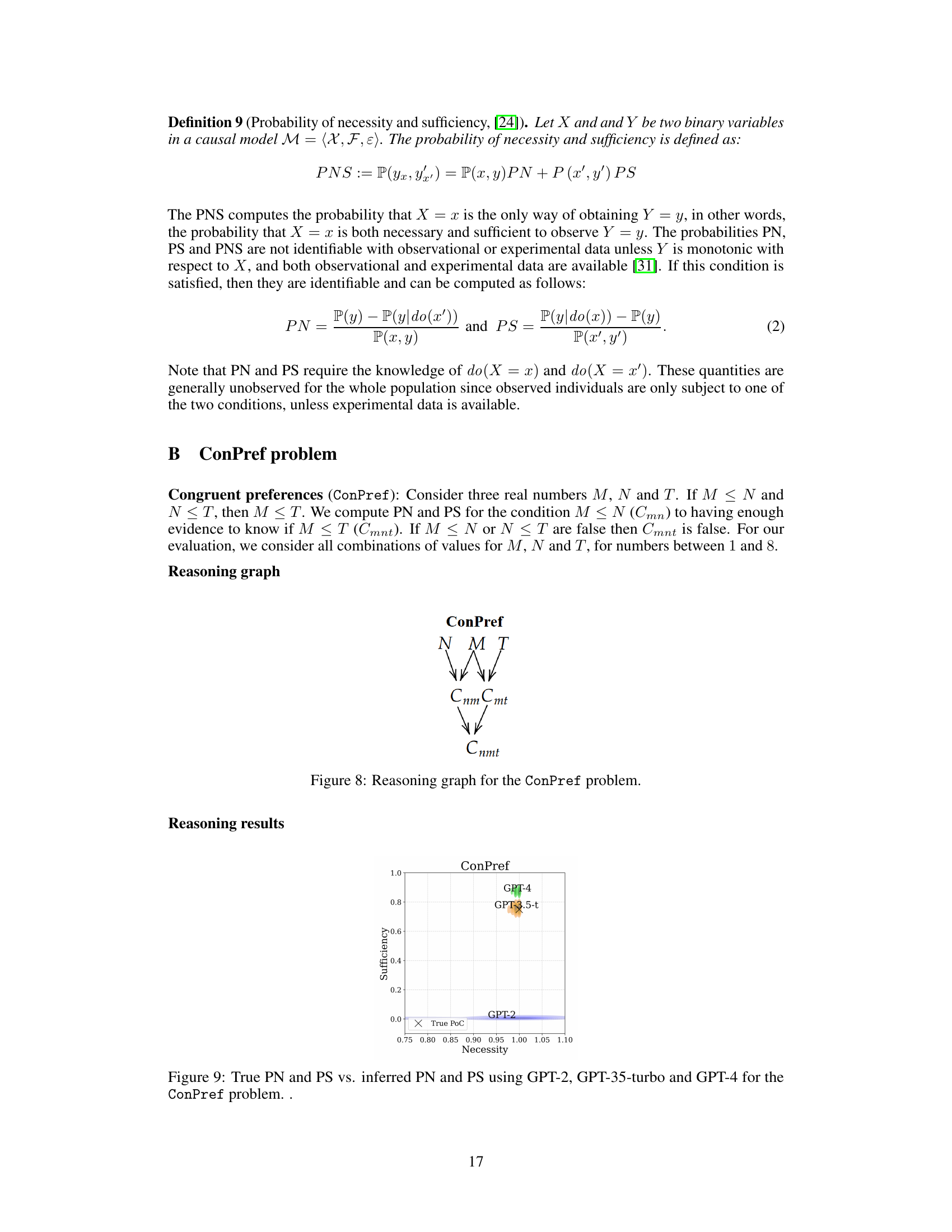

This figure compares the true probabilities of necessity (PN) and sufficiency (PS) with those estimated by three different language models (GPT-2, GPT-3.5-turbo, and GPT-4) for three different mathematical reasoning problems. The densities represent the uncertainty in the model’s estimations, which are caused by the randomness of their responses. For each problem, the models’ estimated PN and PS values are plotted against the true values. This visualization allows for assessment of how well each model approximates the true probabilities. Overall, the figure suggests varying degrees of success in each model’s ability to perform causal reasoning, highlighting GPT-4’s superior performance.

This figure shows the HEX diagram for a counterfactual query in the divisibility by six problem (Div6). It breaks down the query into two sub-queries: QC3=True (setting C3 to True) and QC6 (replacing C6 with its counterfactual). The diagram illustrates how the counterfactual state can be computed either through the direct application of the structural causal model or by using an LLM (Large Language Model).

This figure compares the performance of three large language models (GPT-2, GPT-3.5-turbo, and GPT-4) on a simple arithmetic task involving divisibility by 6. Two types of prompts were used: direct prompts which simply ask if a number is divisible by 6, and counterfactual prompts which introduce a hypothetical change to the number’s prime factorization before asking the same question. The results show that all three models perform well on the direct prompts, but their accuracy significantly decreases when presented with the counterfactual prompts. This demonstrates the models’ limitation in handling hypothetical scenarios and genuine causal reasoning.

This figure compares the performance of different large language models (LLMs) on a divisibility problem (Div6). It shows the necessity and sufficiency probabilities estimated by LLMs from the Llama and Phi families, contrasted against the true probabilities. The results demonstrate that even across different LLMs, the findings are consistent with the study’s overall conclusions.

Full paper#