↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Differentiable structure learning offers a continuous optimization approach to causal discovery, but integrating prior partial order constraints—common in real-world applications—has been challenging. Existing methods either don’t handle these constraints effectively or resort to non-continuous optimization techniques. This mismatch between constraint types and the optimization space hampers the ability of differentiable methods to leverage this valuable prior information.

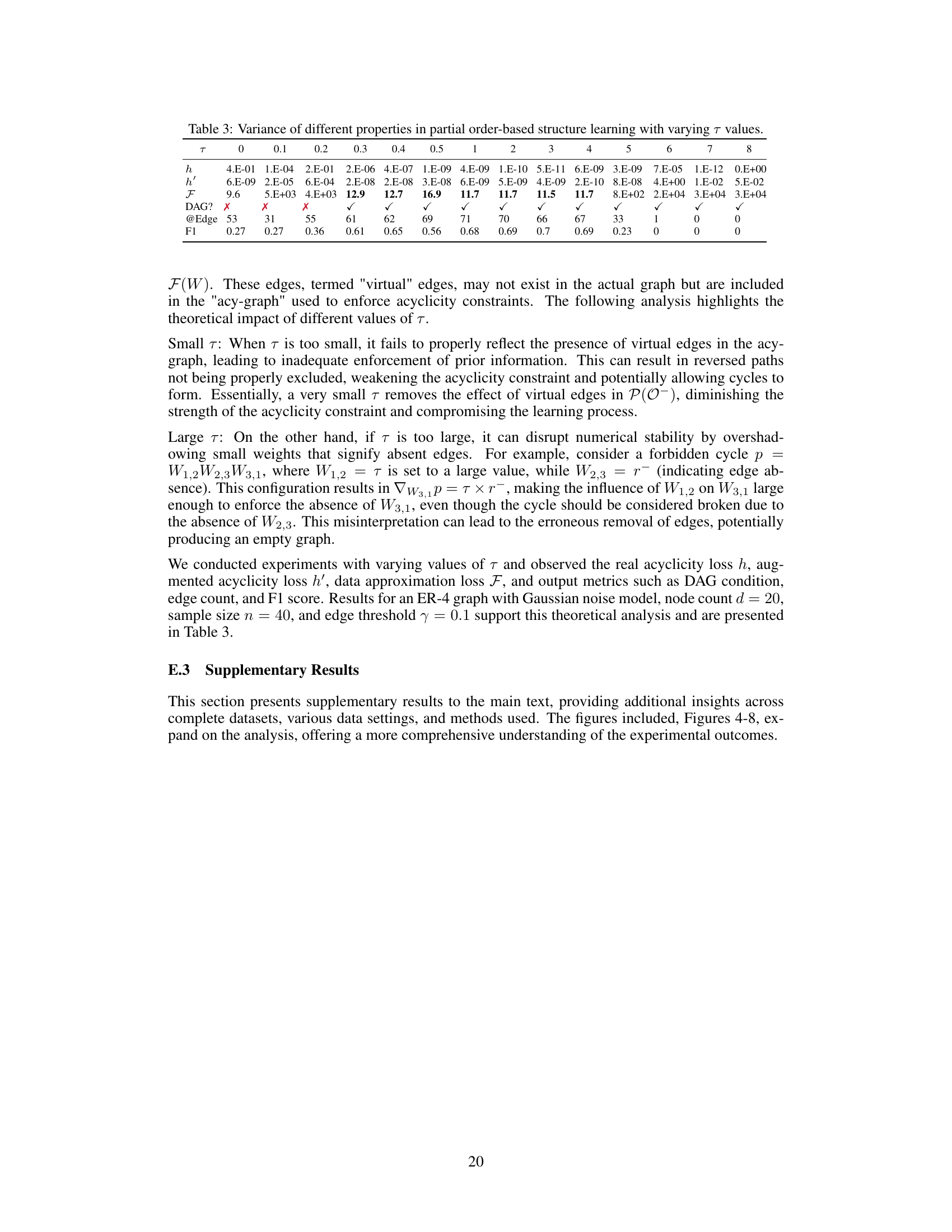

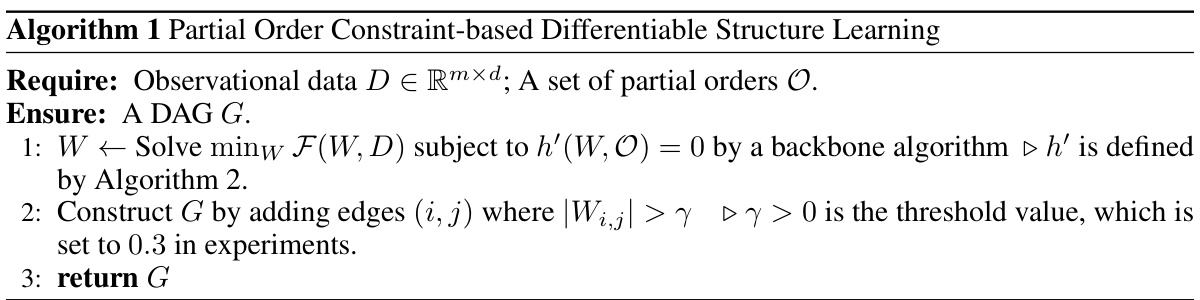

This paper introduces a new method to address the above issues by transforming partial orders into equivalent constraints suitable for continuous optimization in graph space. The proposed method efficiently handles long sequential orderings. It augments the existing acyclicity constraint by integrating information from all maximal paths derived from a transitive reduction of the partial order. The authors demonstrate the effectiveness of their method through theoretical validation and empirical evaluations using both synthetic and real-world data, showing significant improvements over existing approaches.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in causal discovery because it bridges the gap between differentiable structure learning and the practical use of prior knowledge. It offers a novel and efficient method for integrating prior partial order constraints into continuous optimization, thereby improving the accuracy and efficiency of structure learning. This opens exciting new avenues for applying prior knowledge in real-world causal discovery scenarios where such information is often available.

Visual Insights#

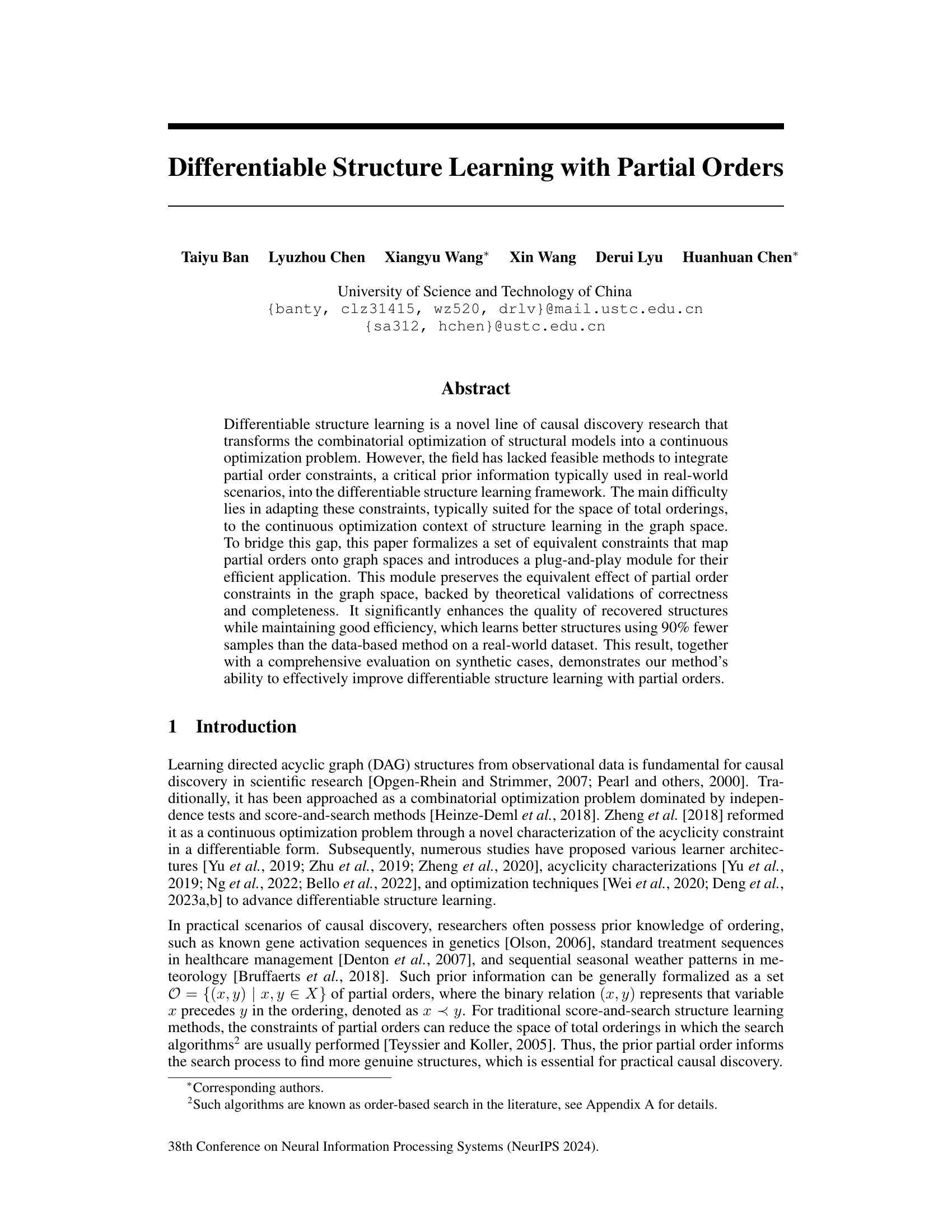

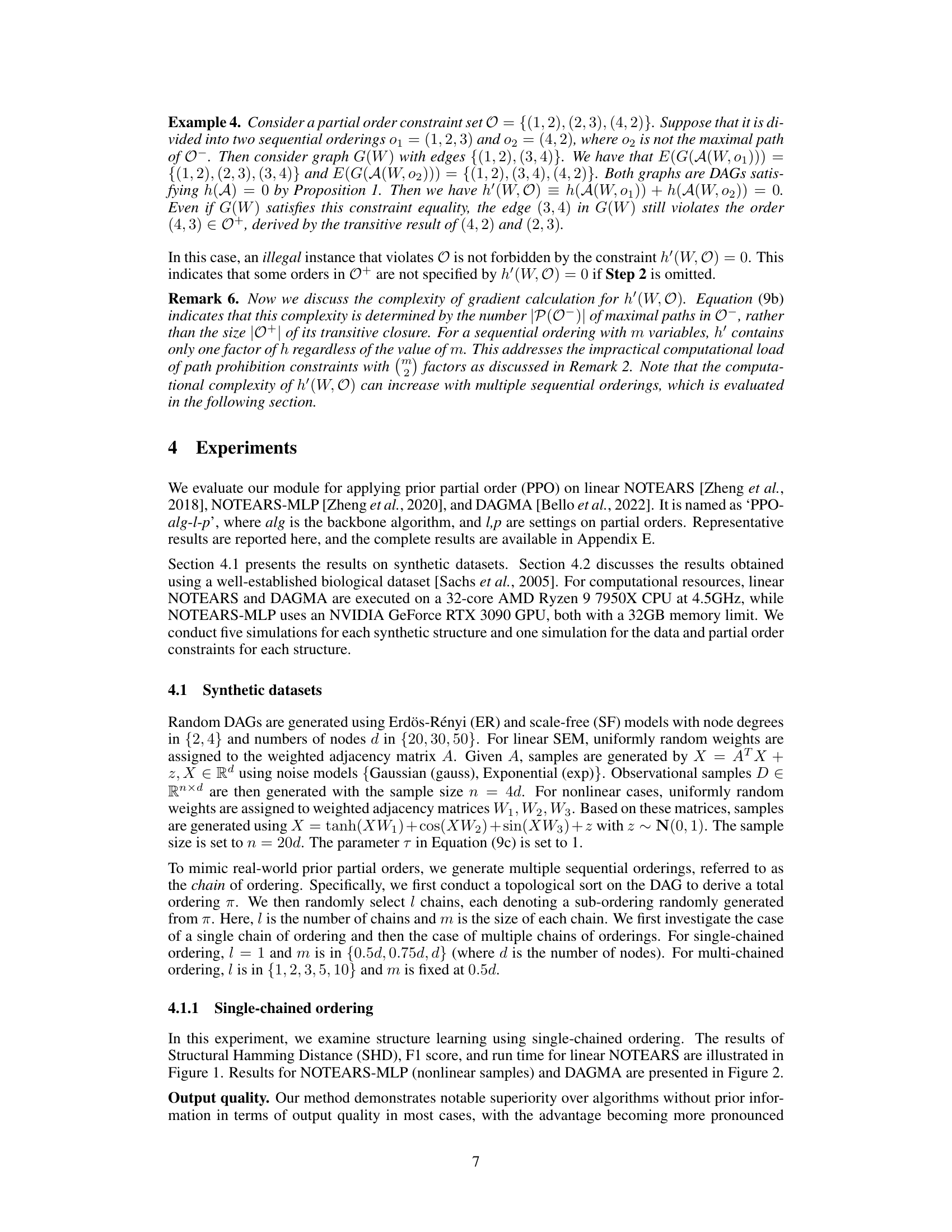

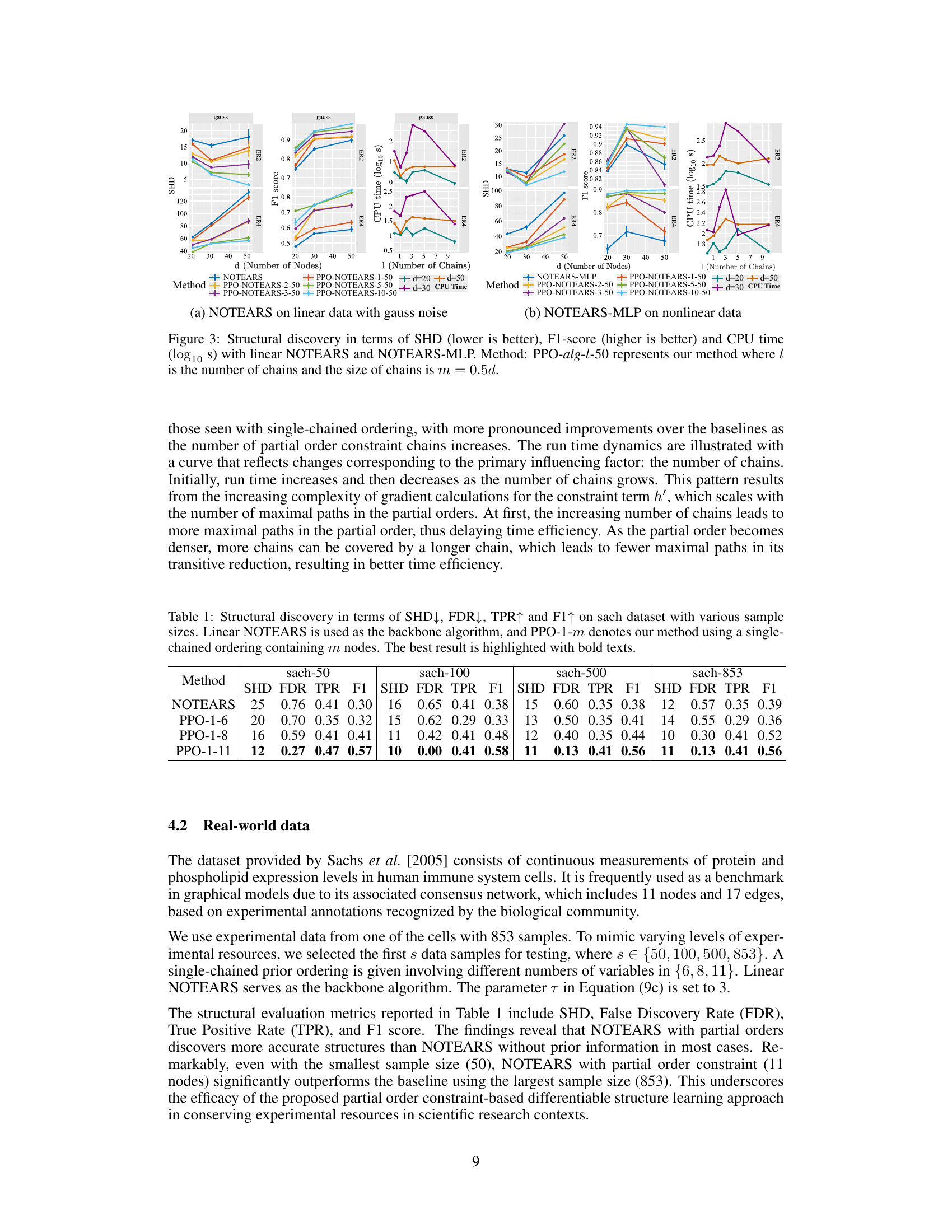

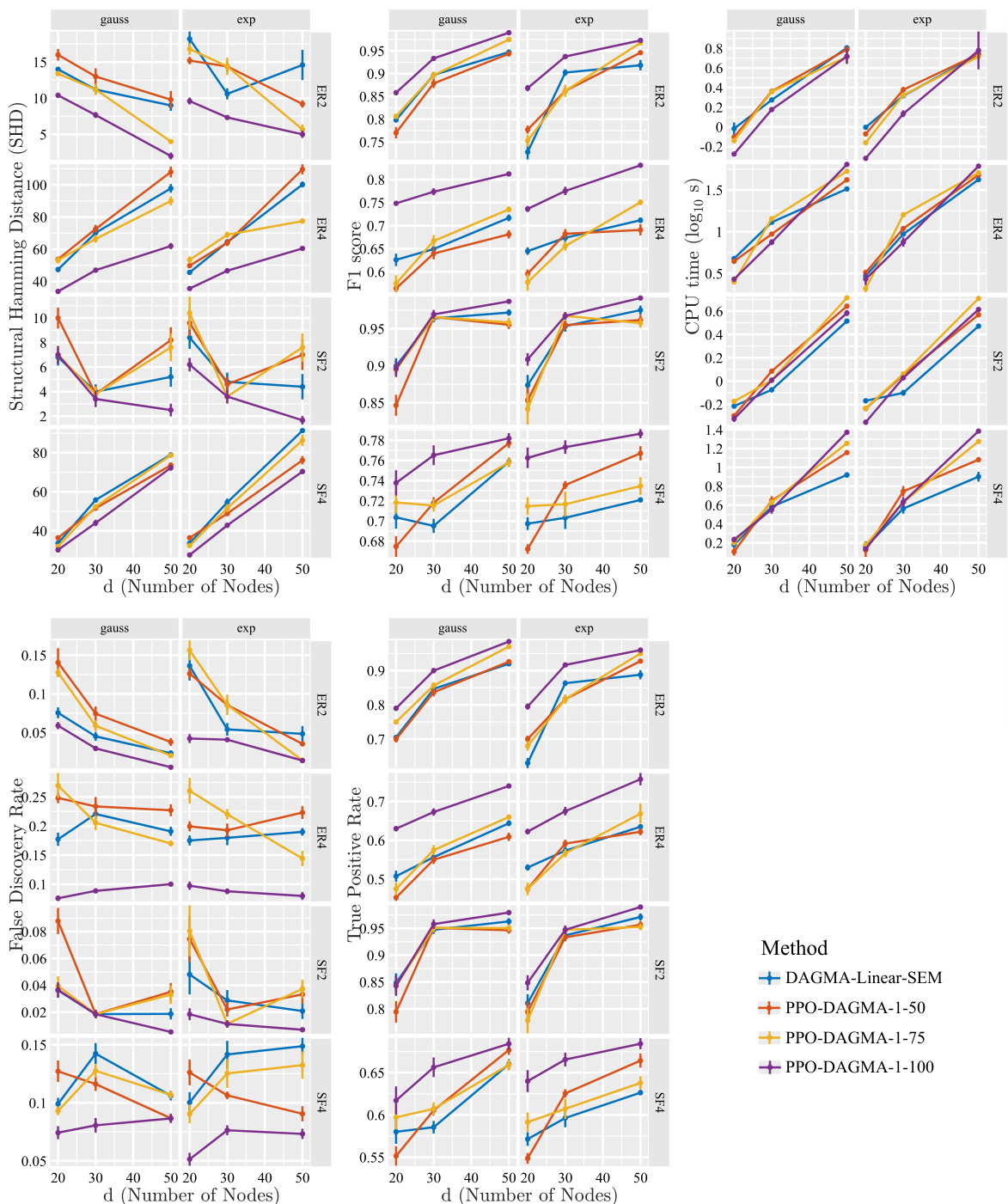

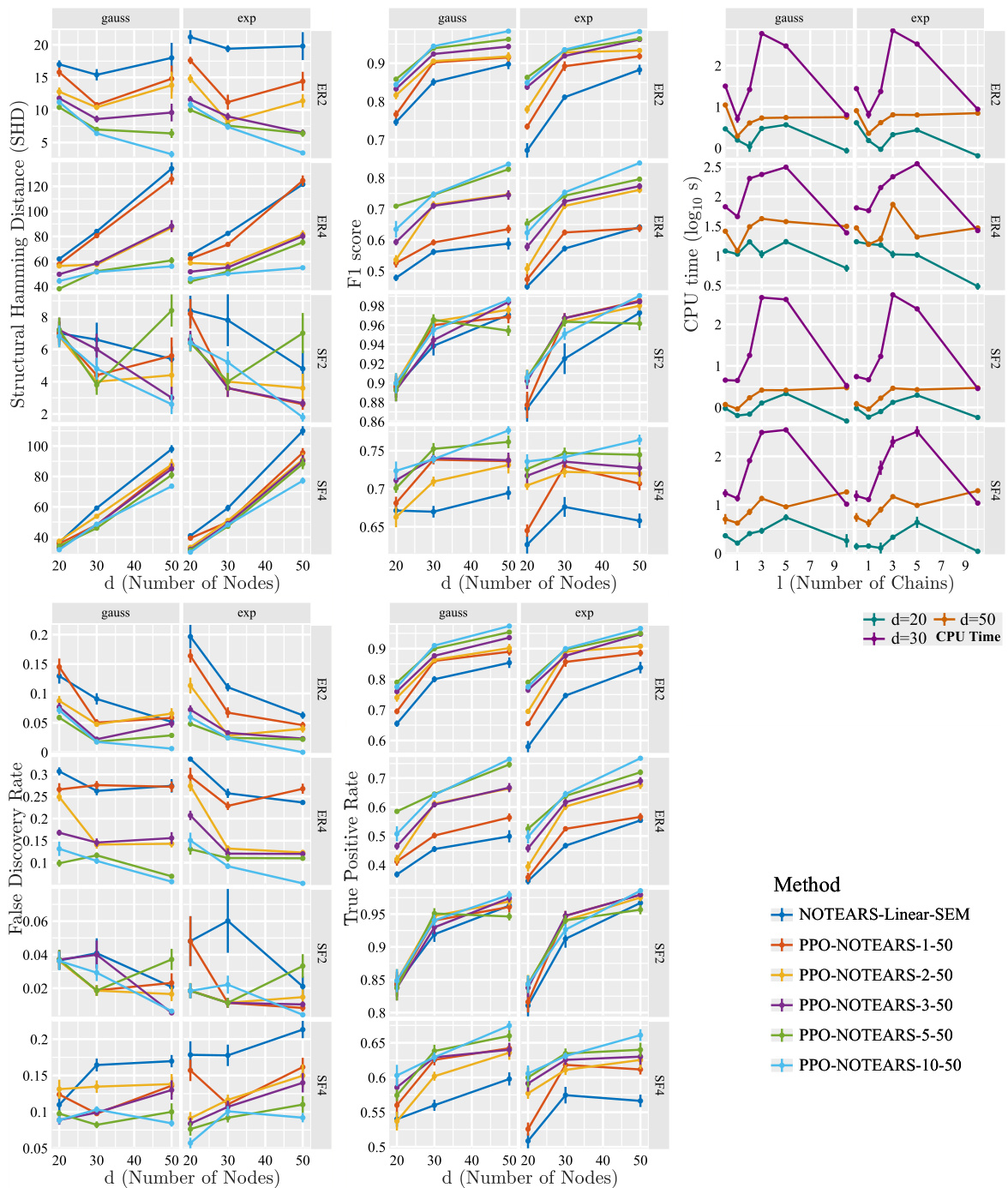

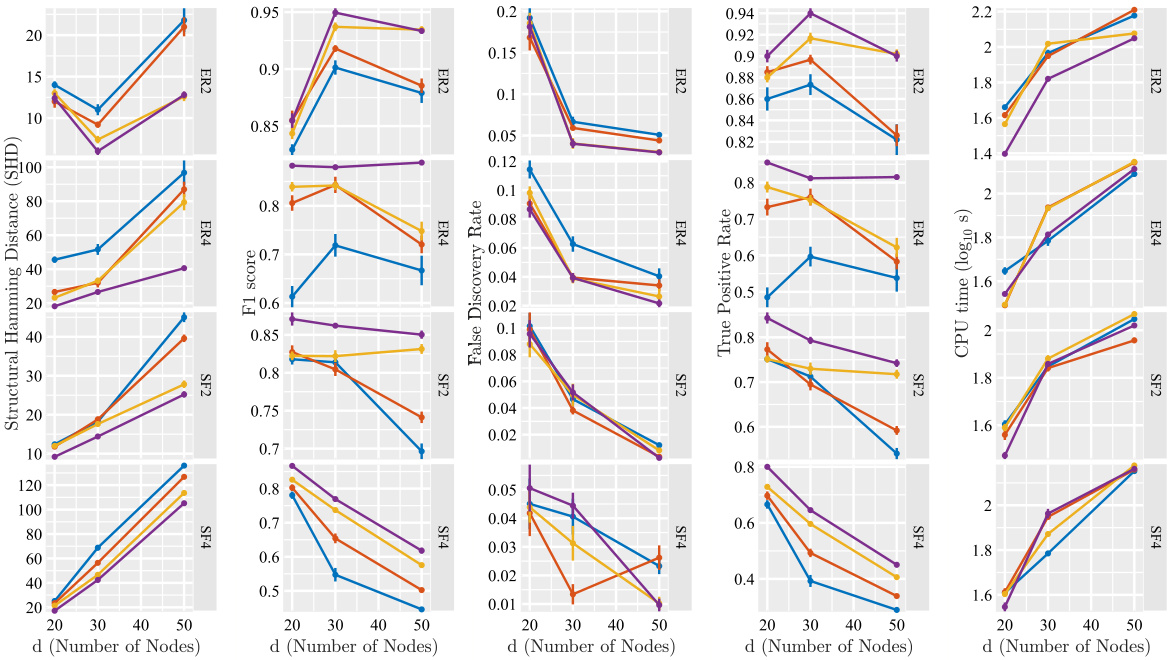

This figure shows the performance of the proposed method (PPO-NOTEARS) compared to the baseline method (NOTEARS) on linear data for structural discovery. The results are presented in terms of Structural Hamming Distance (SHD), F1-score, and CPU time. Different graph types (Erdös-Rényi and scale-free) and noise types (Gaussian and Exponential) from Structural Equation Models (SEMs) are considered. Error bars represent standard deviation. The impact of different percentages (p%d) of prior knowledge is also shown, as is the graph type (ER or SF) and the expected number of edges.

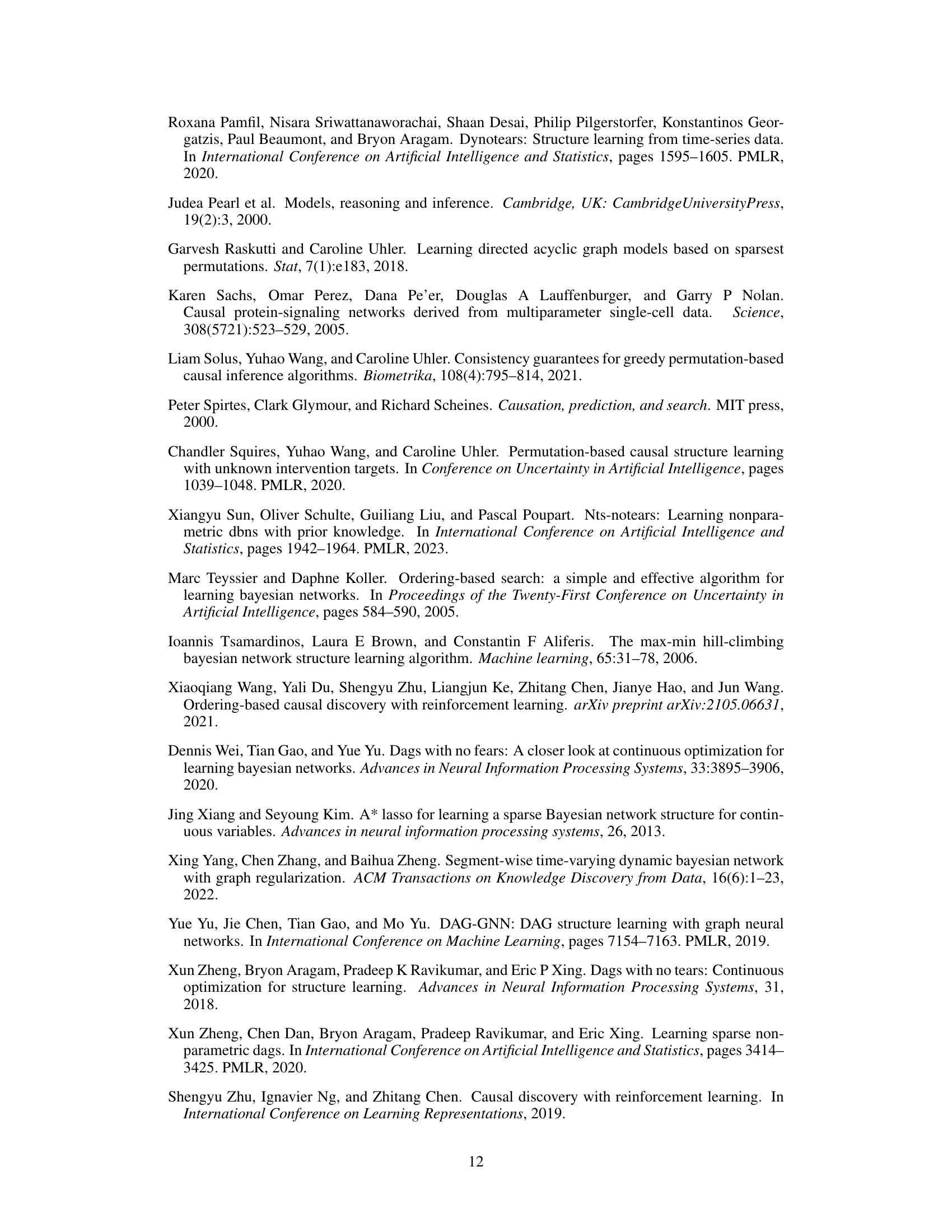

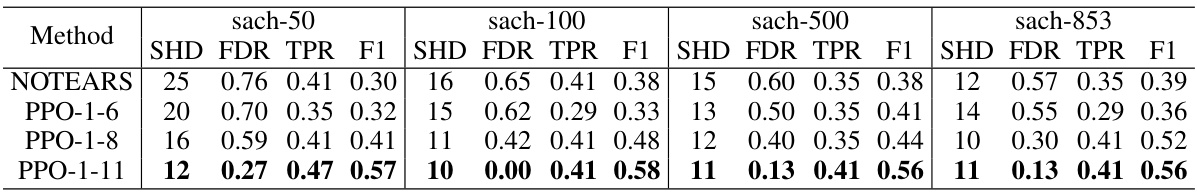

This table presents the results of applying the proposed method (PPO) and the baseline method (NOTEARS) on the Sachs dataset with different sample sizes. The metrics used to evaluate the performance are Structural Hamming Distance (SHD), False Discovery Rate (FDR), True Positive Rate (TPR), and F1-score. The results show that the proposed method with a single-chained ordering containing different numbers of nodes outperforms the baseline method in terms of SHD, FDR, TPR, and F1-score across all sample sizes.

In-depth insights#

Partial Order Intro#

A section titled ‘Partial Order Intro’ in a research paper would likely introduce the concept of partial orders within the context of the paper’s main topic, which might be causal inference, graph theory, or a related field. The introduction would likely define a partial order, highlighting its properties: reflexivity, antisymmetry, and transitivity. It would then contrast partial orders with total orders, emphasizing that partial orders allow for the comparison of some but not all pairs of elements, unlike total orders that linearly order all elements. The introduction might then discuss the relevance of partial orders to the research problem, perhaps explaining how partial order constraints reflect prior knowledge or assumptions in real-world scenarios. This prior information is invaluable in reducing the search space and improving the accuracy of structure learning algorithms. Finally, the introduction would probably provide a brief overview of how partial orders will be used within the paper’s methodology, possibly mentioning techniques for representing and incorporating these constraints in algorithms and models. The introduction sets the stage for subsequent sections detailing the specific approach to leveraging partial order information to solve the research problem.

DAG Learning#

DAG (Directed Acyclic Graph) learning is a crucial area of machine learning focused on inferring causal relationships from observational data. The core challenge lies in learning the graph structure itself, which represents the causal dependencies, while simultaneously ensuring the acyclicity constraint—no directed cycles are allowed. Traditional approaches often rely on combinatorial optimization, but are computationally expensive for large datasets. Differentiable DAG learning offers a powerful alternative, framing the problem as a continuous optimization task, thereby leveraging the power of gradient-based methods. This approach addresses the acyclicity constraint through various differentiable techniques and allows for more efficient and scalable learning, especially compared to traditional score-based methods that use discrete search spaces. However, differentiable methods still struggle with integrating prior knowledge such as partial order constraints, which are often available in real-world scenarios and can significantly reduce the search space. Recent advancements focus on incorporating such priors to further enhance efficiency and accuracy, improving both the quality of the learned DAG and its computational feasibility. Future research should continue to explore more efficient methods for handling complex prior knowledge and scaling to even larger, more intricate datasets to unlock the full potential of DAG learning for causal discovery.

Acyclicity Augment#

The concept of “Acyclicity Augment” in the context of causal structure learning revolves around enforcing the acyclicity constraint within a directed acyclic graph (DAG). Standard methods often struggle with this constraint due to its combinatorial nature. An acyclicity augment technique would aim to address this challenge, likely by transforming the discrete problem of enforcing acyclicity into a continuous, differentiable one. This could involve incorporating a penalty term into a loss function that penalizes cyclic structures, or by using a specific parametrization of the graph adjacency matrix that inherently prevents cycles. Such methods greatly facilitate the use of gradient-based optimization algorithms in structure learning. A key advantage is the ability to integrate prior knowledge (e.g., partial order constraints) which helps guide the learning process toward more accurate DAGs. However, care must be taken to avoid over-regularization, as overly strict acyclicity augmentation could compromise the model’s ability to capture true relationships, leading to reduced accuracy and potentially missing important edges. The optimal level of regularization would depend on the specific dataset and learning algorithm employed, requiring careful tuning.

Empirical Studies#

An Empirical Studies section in a research paper would present results from experiments designed to test the hypotheses or claims made earlier. It should begin with a clear description of the experimental design, including the datasets used (synthetic and real-world, ideally specifying their properties and size), the evaluation metrics (SHD, F1-score, TPR, FDR, etc.), and the baseline methods compared against. A crucial part would be a detailed presentation of the results, possibly using tables and figures to clearly show the performance of the proposed method compared to baselines. The discussion should highlight significant findings, whether the proposed method outperforms baselines, the impact of different parameters or experimental settings, and any unexpected or surprising results. It is vital to address any limitations of the experimental setup, such as the size of the datasets or the choice of evaluation metrics, and to acknowledge any potential biases. The section should conclude by summarizing the key observations and their implications for the hypotheses being tested, emphasizing the robustness and generalizability of the results.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore more sophisticated methods for handling complex partial order structures. The current approach’s efficiency can be impacted by intricate relationships between variables, suggesting the need for algorithms that can more effectively manage the computational demands of large or dense partial order sets. Another avenue for future work involves investigating the integration of this framework with other forms of prior knowledge. Combining partial order constraints with other types of domain expertise (e.g., known causal effects, conditional independences) could lead to more accurate and robust causal discovery. Finally, extending the approach to handle different types of data and causal models would be beneficial. This would expand its applicability beyond linear structural equation models and broaden its usefulness to different scientific domains. In particular, exploration into handling non-linear relationships and the incorporation of latent variables would significantly enhance the framework’s practical value.

More visual insights#

More on figures

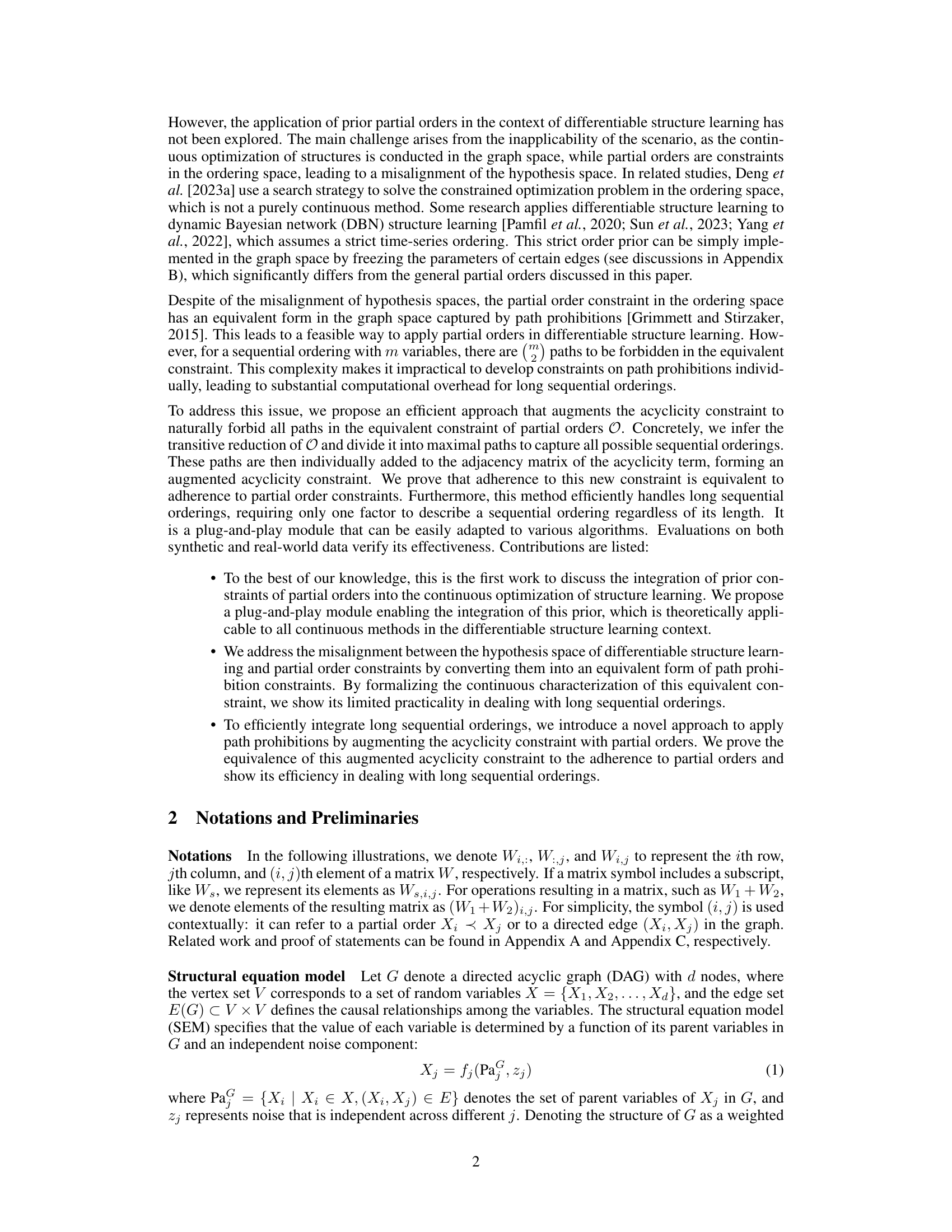

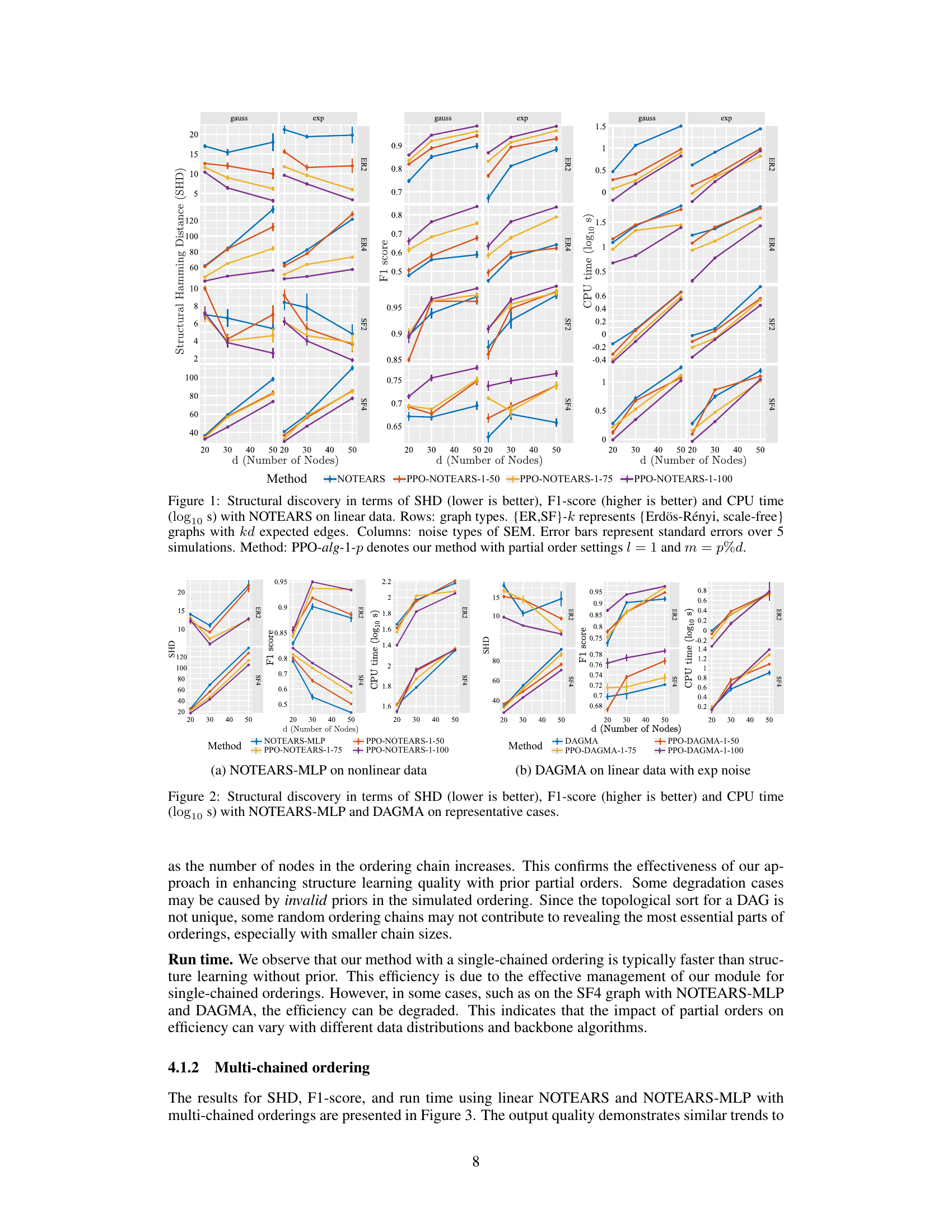

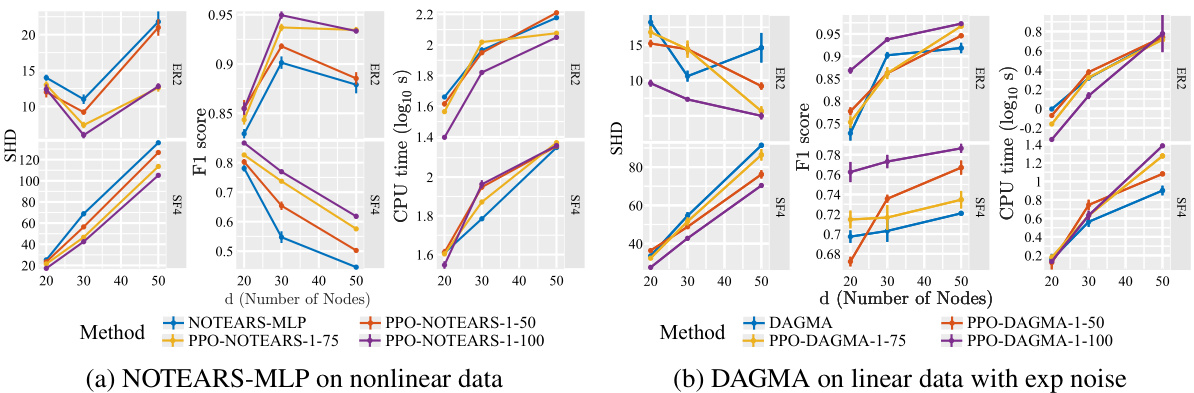

This figure compares the performance of NOTEARS and NOTEARS-MLP with and without the proposed method (PPO) using multi-chained ordering. It shows the structural Hamming distance (SHD), F1 score, and CPU time for different numbers of nodes (d) and chains (l). The results demonstrate the impact of incorporating prior partial order information on improving the accuracy and efficiency of structure learning.

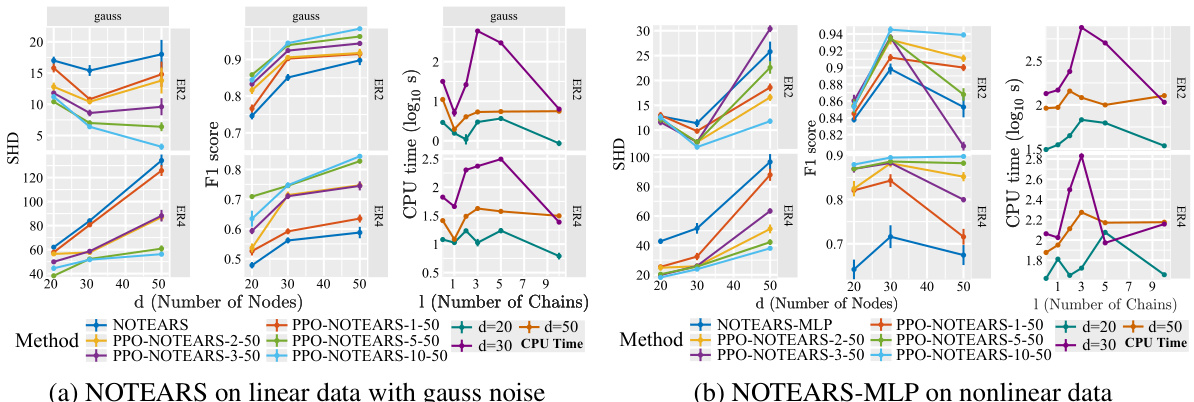

This figure shows the results of experiments on synthetic datasets using NOTEARS and NOTEARS-MLP with multi-chained orderings. It presents the structural Hamming distance (SHD), F1 score, and CPU time for different numbers of nodes (d) and chains (l). Lower SHD values and higher F1 scores indicate better performance. The results demonstrate the impact of the number of chains on the output quality and runtime. The plots illustrate that the proposed method (PPO) generally outperforms the baselines (without prior information), particularly as the number of chains increases. However, runtime can be affected by the number of chains and dataset characteristics.

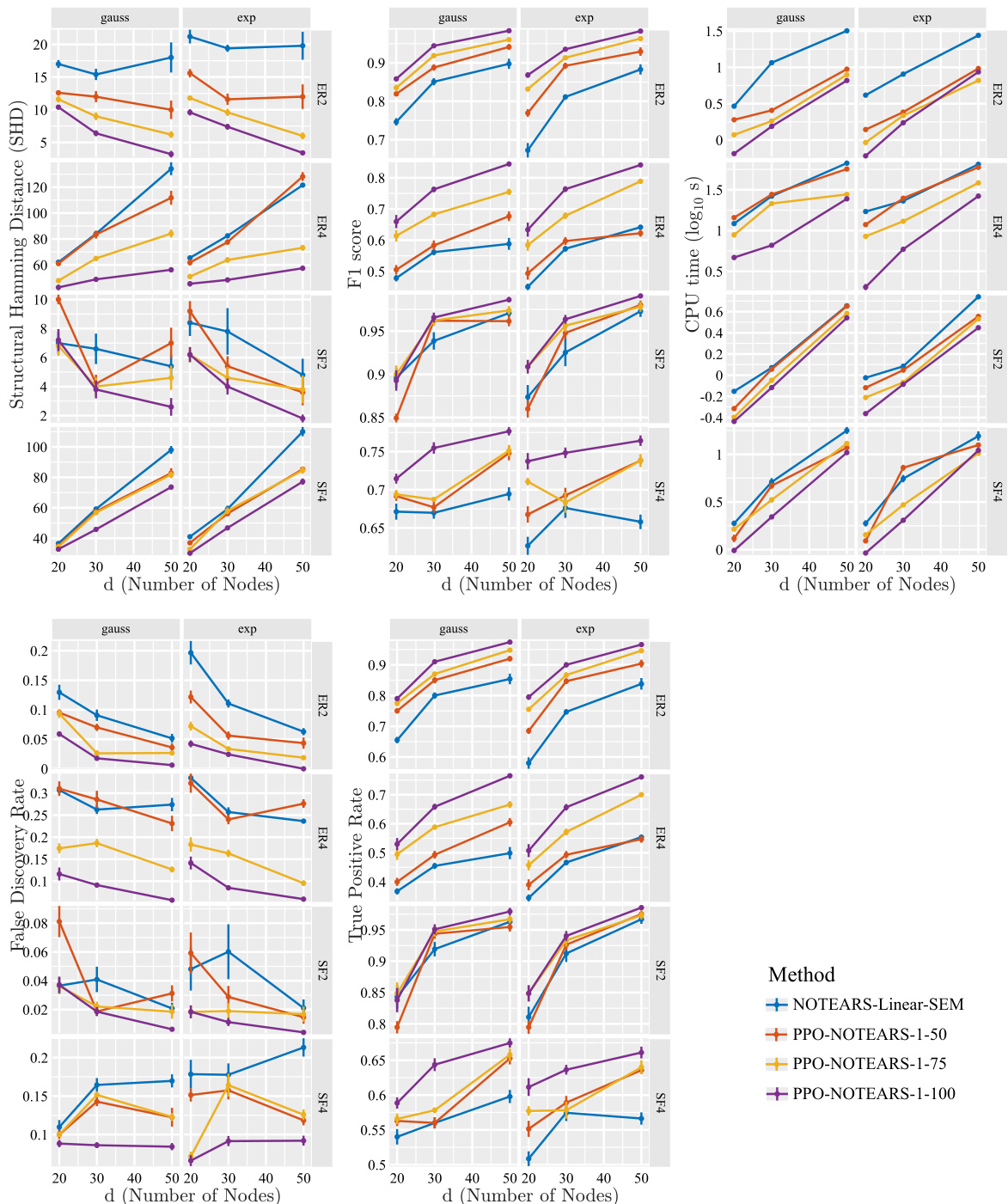

This figure displays the results of applying the proposed method (PPO) to the NOTEARS algorithm for linear data. It compares the performance of NOTEARS with and without the integration of partial order constraints. The metrics used are Structural Hamming Distance (SHD), F1-score, and CPU time. The results are shown for different graph types (Erdös-Rényi and scale-free), noise types in the Structural Equation Model (SEM), and varying percentages of nodes in the single-chained partial order constraint. Error bars indicate standard error over five simulations.

This figure displays the results of experiments using the NOTEARS algorithm with linear data. It compares the performance of the proposed method (PPO) against the baseline NOTEARS in terms of Structural Hamming Distance (SHD), F1 score, and CPU time. Different graph types (Erdös-Rényi and scale-free) and noise types are considered. The results are presented across different numbers of nodes (d) and show the impact of incorporating partial orders into the structure learning process. Error bars are included to represent the standard error over five simulations.

This figure presents the results of experiments using multi-chained orderings for linear NOTEARS and NOTEARS-MLP. The plots show the structural Hamming distance (SHD), F1 score, and CPU time (log scale) for different numbers of nodes and varying numbers of chains. The results demonstrate the impact of increasing numbers of chains on the quality and efficiency of structure learning. Lower SHD values and higher F1 scores indicate improved model accuracy, while lower CPU times suggest improved computational efficiency.

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed method (PPO) to the NOTEARS algorithm for learning linear DAG structures from observational data. It compares the performance of NOTEARS with and without the proposed partial order constraints in terms of structural Hamming distance (SHD), F1-score, and CPU time. The results are broken down by graph type (Erdős-Rényi and scale-free), noise type in the structural equation model (SEM), and the percentage of nodes used in the single-chained ordering constraint. Error bars show standard errors across 5 simulations.

This figure shows the results of experiments using linear NOTEARS and NOTEARS-MLP with multi-chained orderings. The plots show Structural Hamming Distance (SHD), F1 score, and CPU time (log10 s) for different numbers of nodes and numbers of chains. The results demonstrate similar trends to those seen with single-chained ordering, with more pronounced improvements over the baselines as the number of partial order constraint chains increases.

More on tables

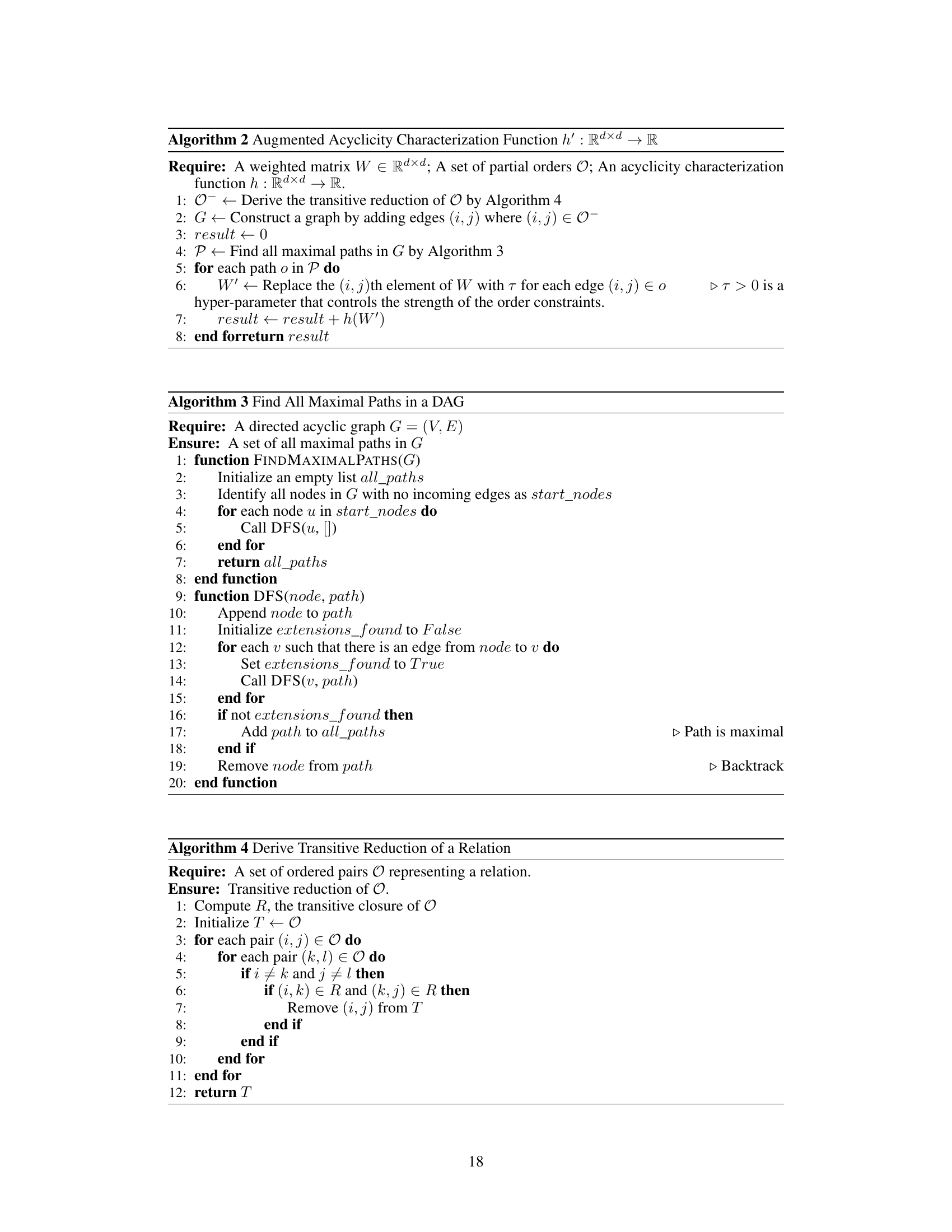

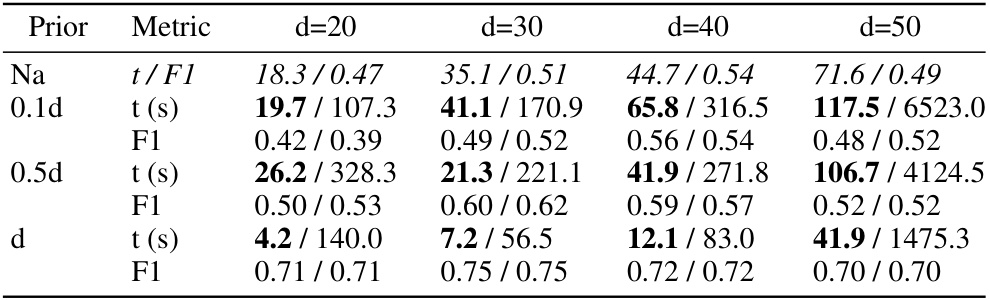

This table compares the performance of two methods for integrating partial order constraints into structure learning: a path absence-based approach (Equation 8) and the proposed augmented acyclicity-based approach. The comparison is done in terms of runtime and F1-score. The results are shown for different numbers of nodes (d) and different percentages of total order constraints (0.1d, 0.5d, d). ‘Na’ represents the baseline without any partial order constraints. The table shows that the augmented acyclicity-based approach is significantly faster and achieves a comparable F1-score.

This table compares two methods for integrating partial order constraints into structure learning: a path absence-based approach and an augmented acyclicity-based approach. It shows the runtime (in seconds) and F1-score for each method under different partial order settings (0.1d, 0.5d, d, where d is the number of nodes) and compares them to a baseline with no prior constraints. The results demonstrate the trade-off between runtime and accuracy of the two constraint approaches.

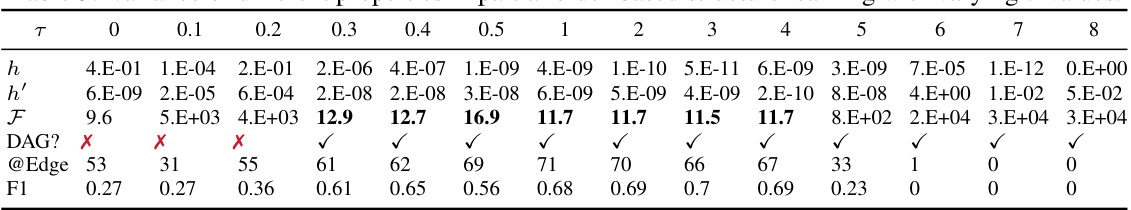

This table shows how different properties of the partial order-based structure learning method vary with different values of the hyperparameter τ. The properties shown are the augmented acyclicity loss (h’), the data approximation loss (F), whether the resulting graph is a DAG, the number of edges in the graph, and the F1-score. The table demonstrates that an optimal value of τ exists that balances enforcing the acyclicity constraint with fitting the data well.

Full paper#