↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Cognitive Diagnosis (CD) is essential in education, aiming to accurately and fairly assess students’ knowledge. However, real-world CD often suffers from data sparsity – many students interact with only a few exercises, leading to inaccurate and unfair diagnoses. Existing solutions often rely on complex models that sacrifice interpretability.

This paper introduces a novel framework, CMCD, to tackle data sparsity without modifying the model. CMCD uses monotonic data augmentation, leveraging the fundamental educational principle of monotonicity: better understanding leads to higher accuracy. CMCD adds two data augmentation constraints ensuring the augmented data adheres to this principle and providing theoretical guarantees for accuracy and convergence. Extensive experiments showed CMCD’s superior performance over baseline models, achieving both more accurate and fairer diagnoses on real-world datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in intelligent education and cognitive diagnosis. It directly addresses the prevalent issue of data sparsity, offering a novel solution that enhances both accuracy and fairness of diagnostic models. The introduction of a monotonic data augmentation framework, coupled with theoretical guarantees, provides a robust and generalizable methodology for improving the efficacy of existing CD models. This significantly advances current research on data-centric approaches in this domain and opens up new possibilities for fairness-aware educational technologies.

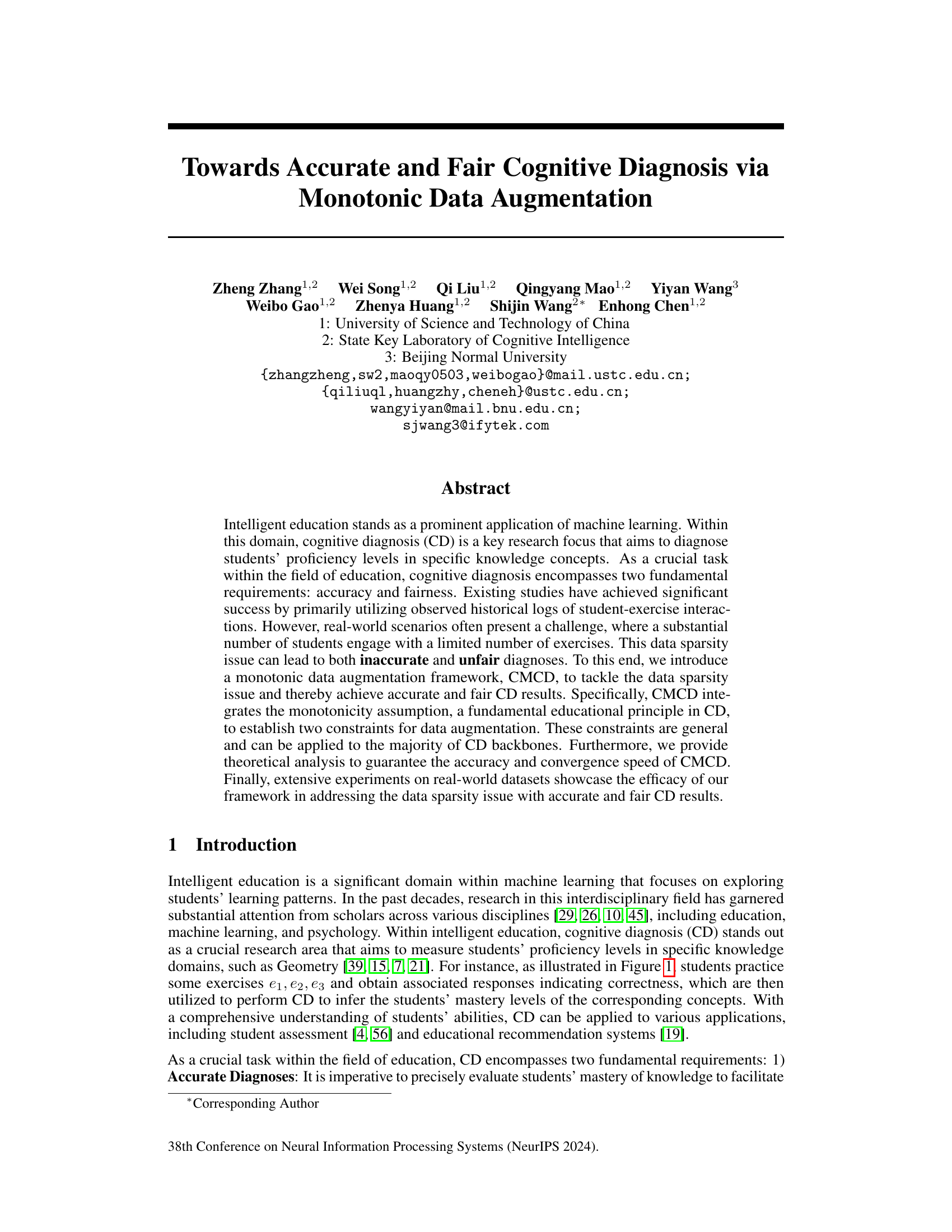

Visual Insights#

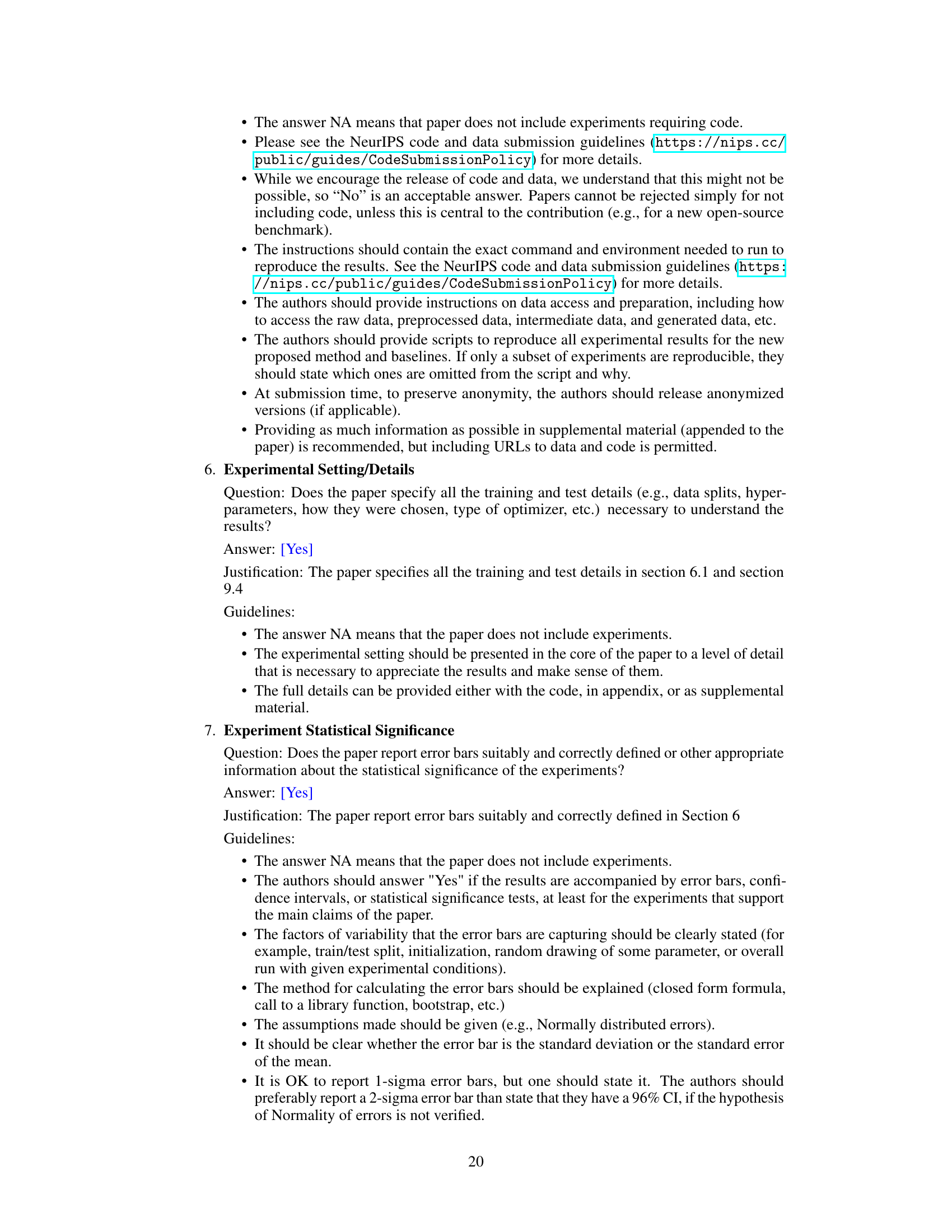

The figure illustrates the cognitive diagnosis process. On the left, we see a table showing exercises (e1, e2, e3…) and the knowledge concepts they assess (A, B, C, D, E). In the center, a table demonstrates the interaction of two students, Sue and Bob, with these exercises, showing correct or incorrect responses. After practice, a cognitive diagnosis is performed. On the right, a radar chart visually represents the diagnostic report, showing Sue and Bob’s mastery of each concept. The legend clarifies the meaning of symbols used in the interaction table and radar chart.

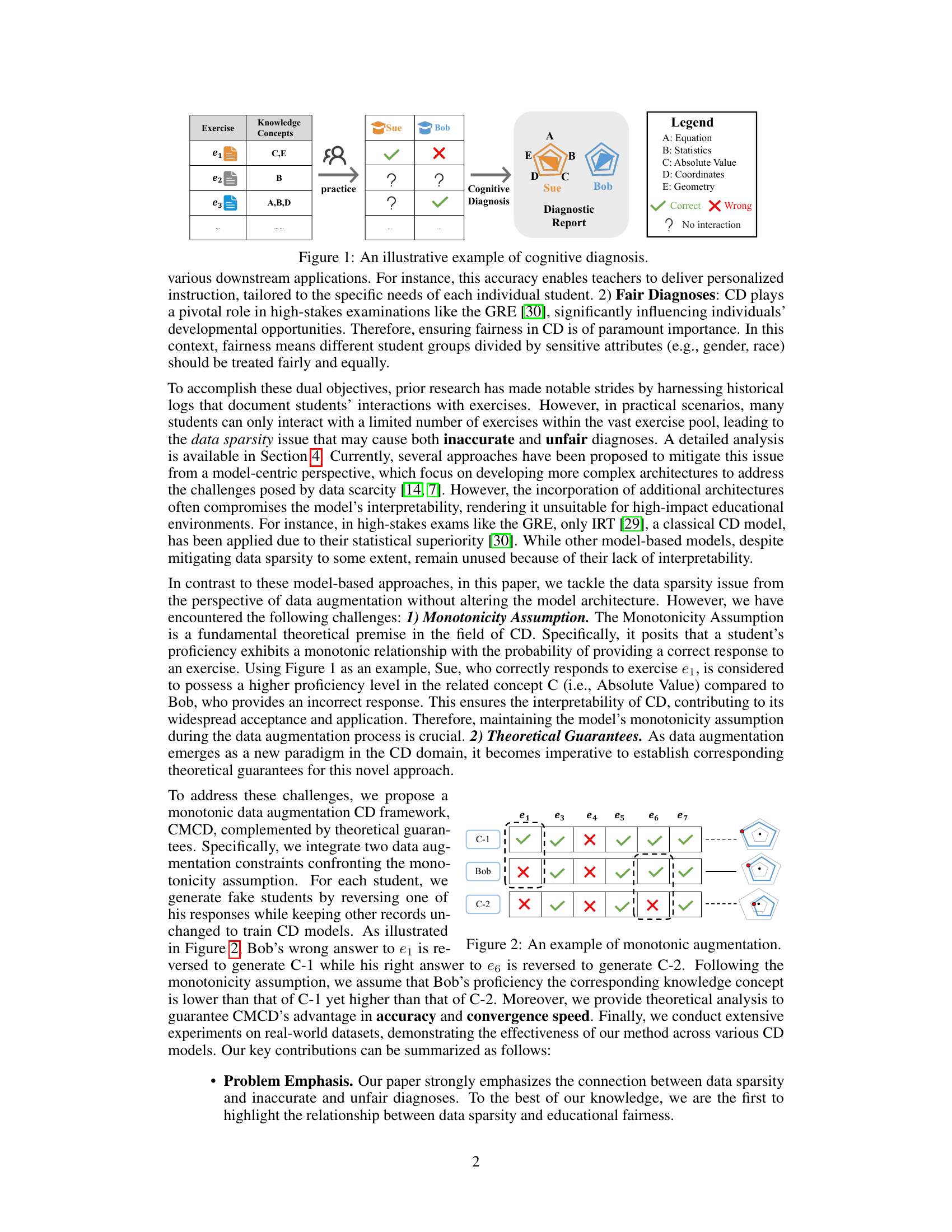

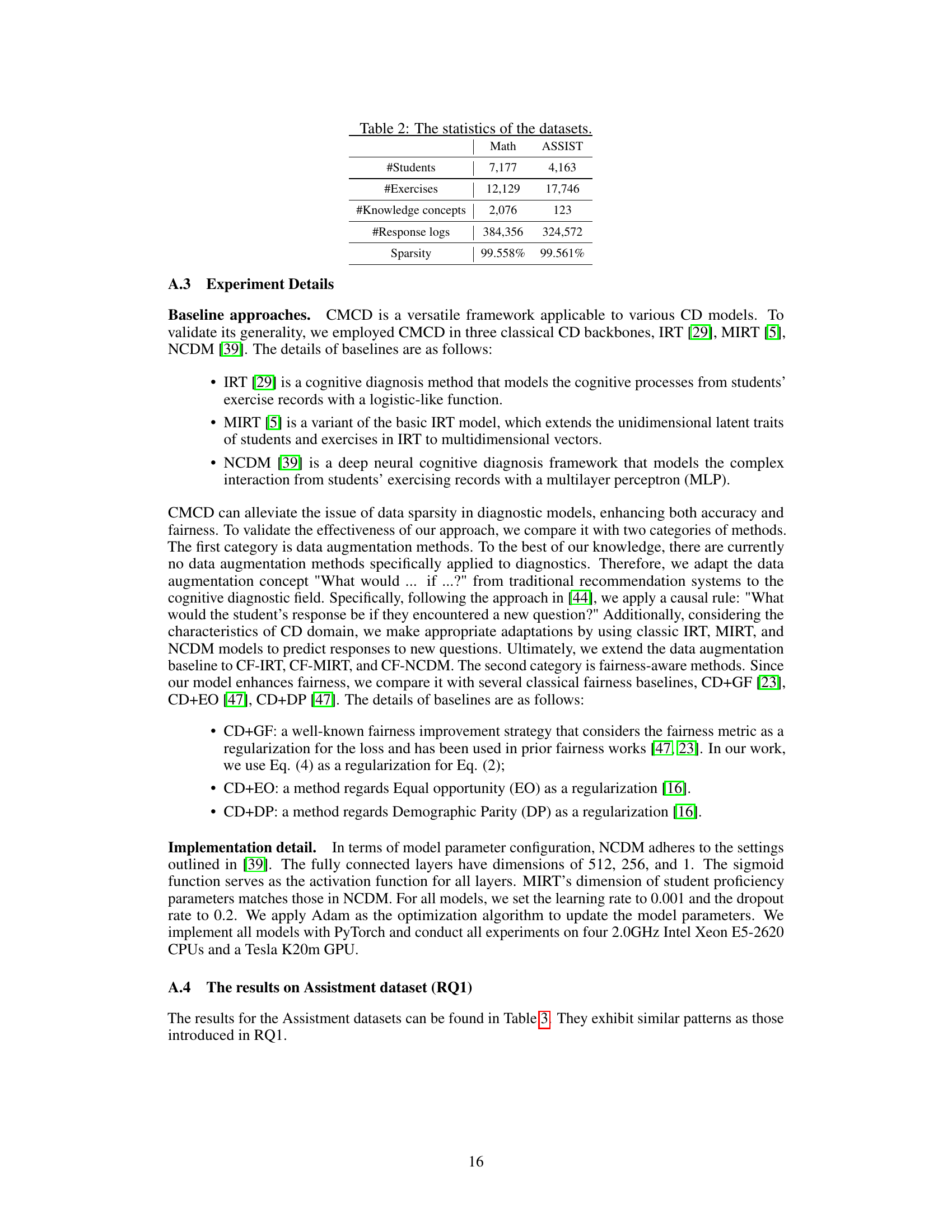

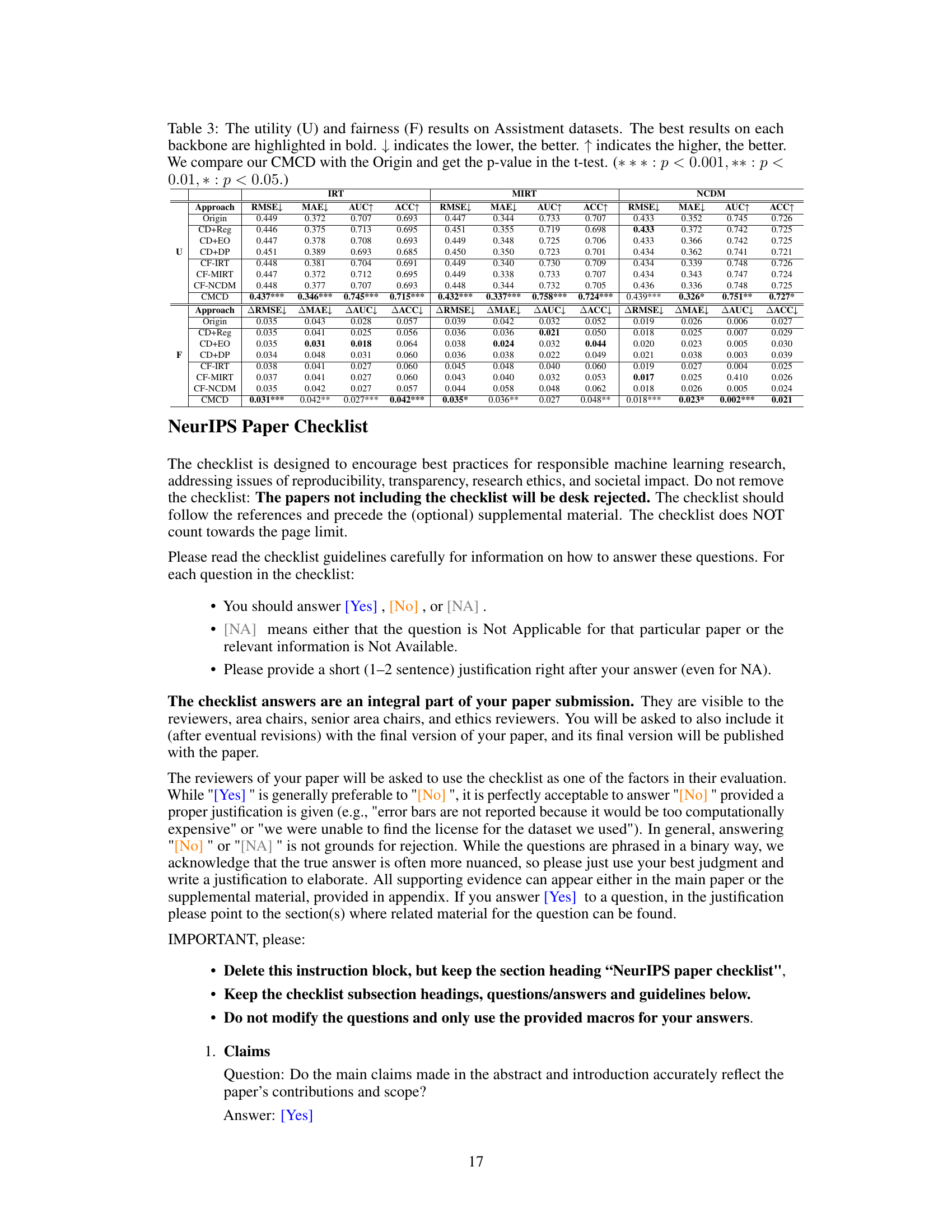

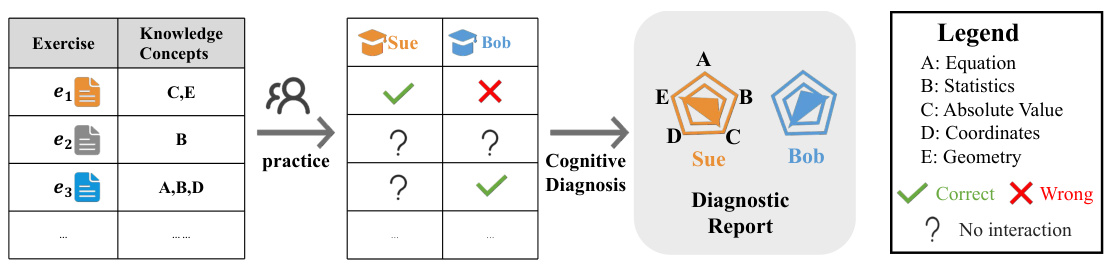

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on the Math dataset in terms of both utility and fairness. Utility is measured by RMSE, MAE, AUC, and ACC, while fairness is measured by ∆RMSE, ∆MAE, ∆AUC, and ∆ACC. The ‘Origin’ column represents the baseline performance without any intervention. The other columns represent various methods compared to the baseline; CMCD shows significant improvements in both utility and fairness.

In-depth insights#

Monotonic Augmentation#

The concept of “Monotonic Augmentation” in the context of cognitive diagnosis is intriguing. It leverages the fundamental educational principle of monotonicity, which posits that a student’s proficiency level directly correlates with their probability of correctly answering an exercise. By integrating this assumption into a data augmentation framework, the approach aims to address the pervasive issue of data sparsity in real-world educational datasets. The core idea is to generate synthetic student-exercise interaction data that respects the monotonicity constraint, thereby ensuring that the augmented data maintains the integrity of the underlying educational principle. This is a data-centric approach, focusing on enriching the dataset rather than solely modifying the model architecture, which is crucial for preserving the model’s interpretability, especially in high-stakes educational scenarios where transparency is paramount. The framework cleverly tackles the challenge of data scarcity by creating realistic and reliable augmentations, leading to more accurate and fair cognitive diagnoses. The theoretical analysis further strengthens the method by guaranteeing both accuracy and faster convergence, highlighting the method’s robustness and efficiency.

Data Sparsity Issue#

The ‘Data Sparsity Issue’ in cognitive diagnosis (CD) arises from the limited number of exercises completed by many students, leading to insufficient data for accurate and fair diagnostic models. This sparsity hinders the ability of CD models to precisely assess students’ proficiency in specific knowledge concepts, creating a significant challenge in educational settings. Data sparsity leads to inaccurate diagnoses, misrepresenting students’ true understanding. It also introduces unfairness, disproportionately affecting students with limited opportunities to interact with a wider range of exercises. This is especially problematic in high-stakes assessments where accurate and unbiased evaluations are crucial. Addressing this challenge is essential for ensuring that CD systems effectively support personalized learning and provide equitable assessments for all students. This issue necessitates robust solutions, such as advanced model architectures or innovative data augmentation strategies that effectively address the limited data and maintain the essential monotonicity assumption in CD. The implications for high-stakes exams and educational recommendations are considerable.

Fairness in CD#

Fairness in Cognitive Diagnosis (CD) is crucial because CD results significantly influence students’ educational opportunities. Data sparsity, where some student groups have limited interaction data, creates a major fairness challenge. Methods focusing solely on model accuracy may inadvertently perpetuate existing biases present in the sparse data, leading to unfair diagnoses for underrepresented groups. Achieving fairness necessitates not just accurate predictions but also equitable treatment across all student subgroups. This requires careful consideration of the data representation and augmentation techniques to ensure no group is disproportionately disadvantaged. Bias mitigation techniques should be incorporated into the CD process, possibly through data augmentation strategies that address class imbalance or focus on creating more balanced datasets, to improve fairness and build trust in the CD system’s results.

CMCD Framework#

The CMCD framework tackles the challenge of data sparsity in cognitive diagnosis (CD) by integrating a monotonic data augmentation approach. This framework is particularly valuable because CD, crucial in education, requires both accuracy and fairness in student assessments. Data sparsity often leads to inaccurate and unfair results, especially for students with limited interaction data. CMCD directly addresses this by generating synthetic data while adhering to the monotonicity assumption—a fundamental educational principle that ensures interpretability and consistency in proficiency estimations. This is achieved through the implementation of two data augmentation constraints, which are general and compatible with various CD backbones. Importantly, CMCD is supported by theoretical guarantees regarding the accuracy and convergence speed of the algorithm, ensuring robust performance. The efficacy of the framework is demonstrated through extensive experiments on real-world datasets, highlighting its effectiveness in producing accurate and fair CD results, even with limited data.

Future of CMCD#

The future of CMCD (Cognitive Monotonic Data Augmentation for Cognitive Diagnosis) appears bright, given its demonstrated efficacy in addressing data sparsity and promoting fairness in cognitive diagnosis. Further research could explore CMCD’s application in diverse educational settings, including those with varying levels of student engagement and different cultural contexts. Extending CMCD to handle various response types beyond binary correct/incorrect responses would enhance its practical utility. Investigating the interplay between CMCD and different CD models (e.g., incorporating more sophisticated model architectures) could lead to even more accurate and fair diagnoses. Finally, developing robust theoretical guarantees for CMCD’s performance under various conditions and conducting more extensive experiments would further strengthen its capabilities and establish it as a leading approach in the field of intelligent education.

More visual insights#

More on figures

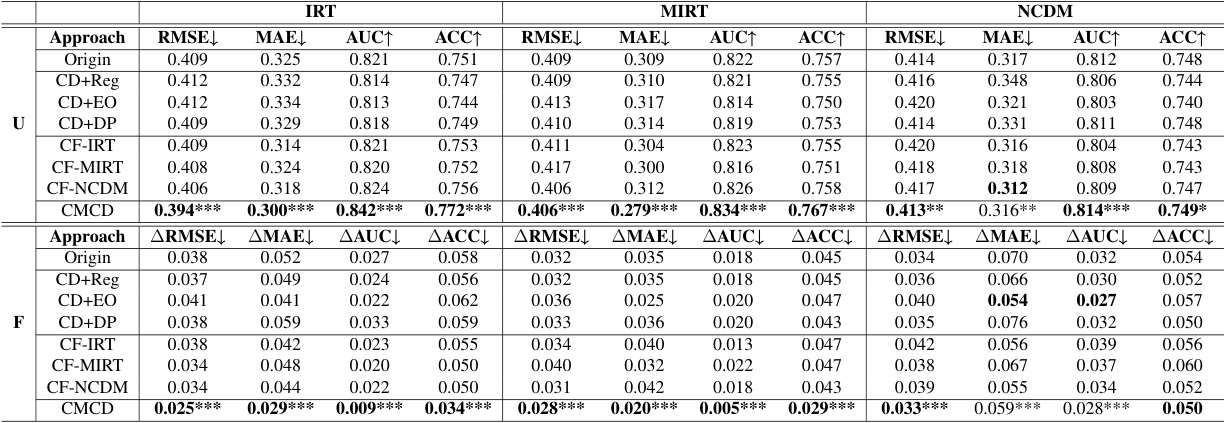

This figure illustrates the monotonic data augmentation process in the CMCD framework. It shows three response patterns for student Bob on seven exercises. The top row represents a generated augmented data point (C-1) where one of Bob’s incorrect answers is changed to correct. The middle row is Bob’s original response pattern. The bottom row is another generated augmented data point (C-2) where one of Bob’s correct answers is changed to incorrect. The pentagons to the right visually represent the student’s proficiency levels, showing how the augmented data points maintain the monotonic property of student proficiency.

This figure demonstrates the effect of data sparsity on the accuracy and fairness of cognitive diagnosis (CD) models. Subfigure (a) shows the distribution of interaction times for students, highlighting the prevalence of data sparsity. Subfigure (b) compares the accuracy (ACC) of different CD models (IRT, MIRT, NCDM) for students with a low number of interactions (log <= 50) against those with a high number of interactions (log > 50), revealing lower accuracy in the sparse data group. Subfigure (c) compares the accuracy of the same models between two groups (Area1 and Area2) likely representing different demographic groups, showcasing the disproportionate impact of data sparsity on different subgroups. Finally, subfigure (d) visually compares the data sparsity disparity between these two groups.

This figure illustrates the CMCD (Cognitive Monotonic Data Augmentation) framework. It shows how the monotonicity assumption in cognitive diagnosis is integrated with data augmentation to address the data sparsity issue. The framework takes student response data as input and generates augmented data based on two hypotheses (Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2) derived from the monotonicity assumption. These hypotheses ensure that the generated data maintains the monotonic relationship between student proficiency and their responses. The augmented data, along with the original data, is fed into a Cognitive Diagnosis Model (CDM) to learn student proficiency levels. Two regularization terms (Ω₁ and Ω₂) are incorporated to enforce the monotonicity constraints during the training process. The final loss function (ℒ) combines the original loss and the regularization terms to achieve accurate and fair cognitive diagnosis results.

This figure shows the number of times the monotonicity assumption is violated during the optimization process for different CD models (IRT, MIRT, NCDM) on two datasets (Math and ASSIST). The x-axis represents the epoch (iteration) of training, and the y-axis represents the count of violations. The plots illustrate the convergence speed of the proposed CMCD method compared to the original method across different models. The fewer the number of violations, the faster the convergence. It shows that CMCD is faster to converge for all models and datasets.

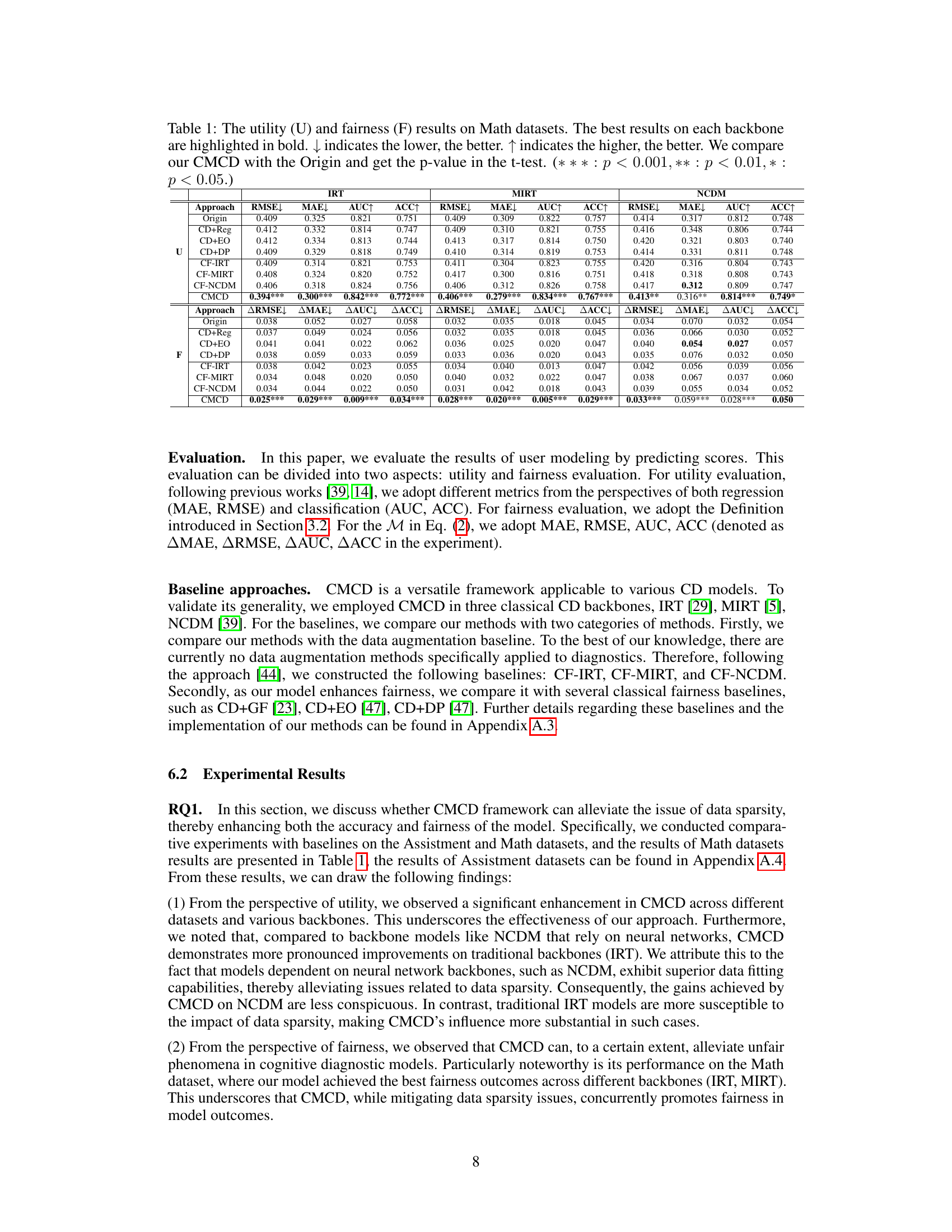

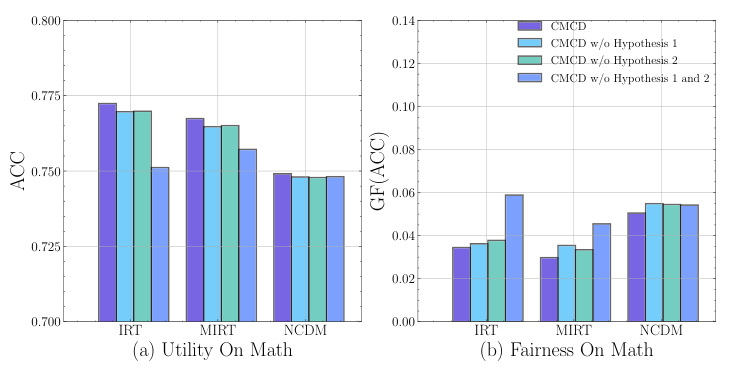

This figure shows the results of ablation experiments conducted on the Math dataset to evaluate the impact of removing different hypothesis strategies from the proposed CMCD framework. The left panel (a) displays the accuracy (ACC) achieved by various CD models (IRT, MIRT, NCDM) under different ablation scenarios. The right panel (b) presents the group fairness (GF(ACC)) results for the same models and scenarios. The results indicate that removing either or both hypotheses leads to a decrease in both accuracy and fairness.

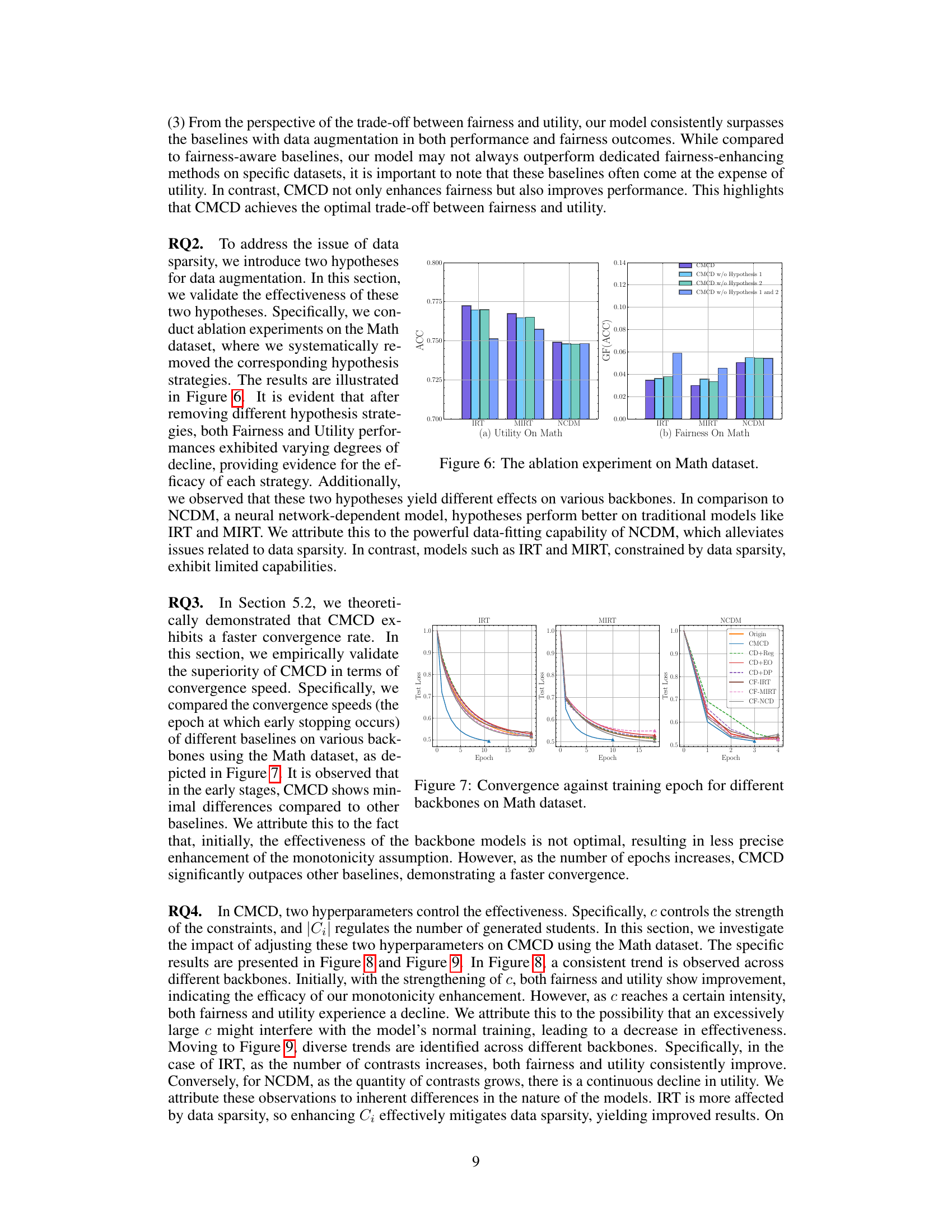

This figure shows the convergence speed of CMCD and other baseline models (Origin, CD+Reg, CD+EO, CD+DP, CF-IRT, CF-MIRT, CF-NCDM) across three different backbones (IRT, MIRT, NCDM) using the Math dataset. The x-axis represents the training epoch, and the y-axis represents the test loss. The plot demonstrates that CMCD generally converges faster than other methods, especially in later training epochs, indicating its superior efficiency in achieving a low test loss.

This figure shows the impact of the hyperparameter c on the performance of the CMCD framework. The hyperparameter c controls the strength of the monotonicity constraint. Three subplots are presented, one for each of the three CD backbones (IRT, MIRT, and NCDM) used in the experiments. Each subplot displays two lines: one for utility (measured by accuracy metrics) and one for fairness (measured using a fairness metric, likely the group fairness metric described in the paper). The x-axis represents the values of the hyperparameter c tested, and the y-axis represents the utility and fairness scores. The results show that there is an optimal value of c for each backbone, where utility is high and fairness is also good. Increasing or decreasing c from this optimal value leads to a decline in either utility or fairness, or both.

The figure shows the ablation study results on the Math dataset. It illustrates the impact of removing each hypothesis (Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2) individually and together on both utility (Accuracy) and fairness performance. The results demonstrate that both hypotheses contribute to the performance gains of the CMCD model, with varying degrees of impact on different model backbones (IRT, MIRT, and NCDM).

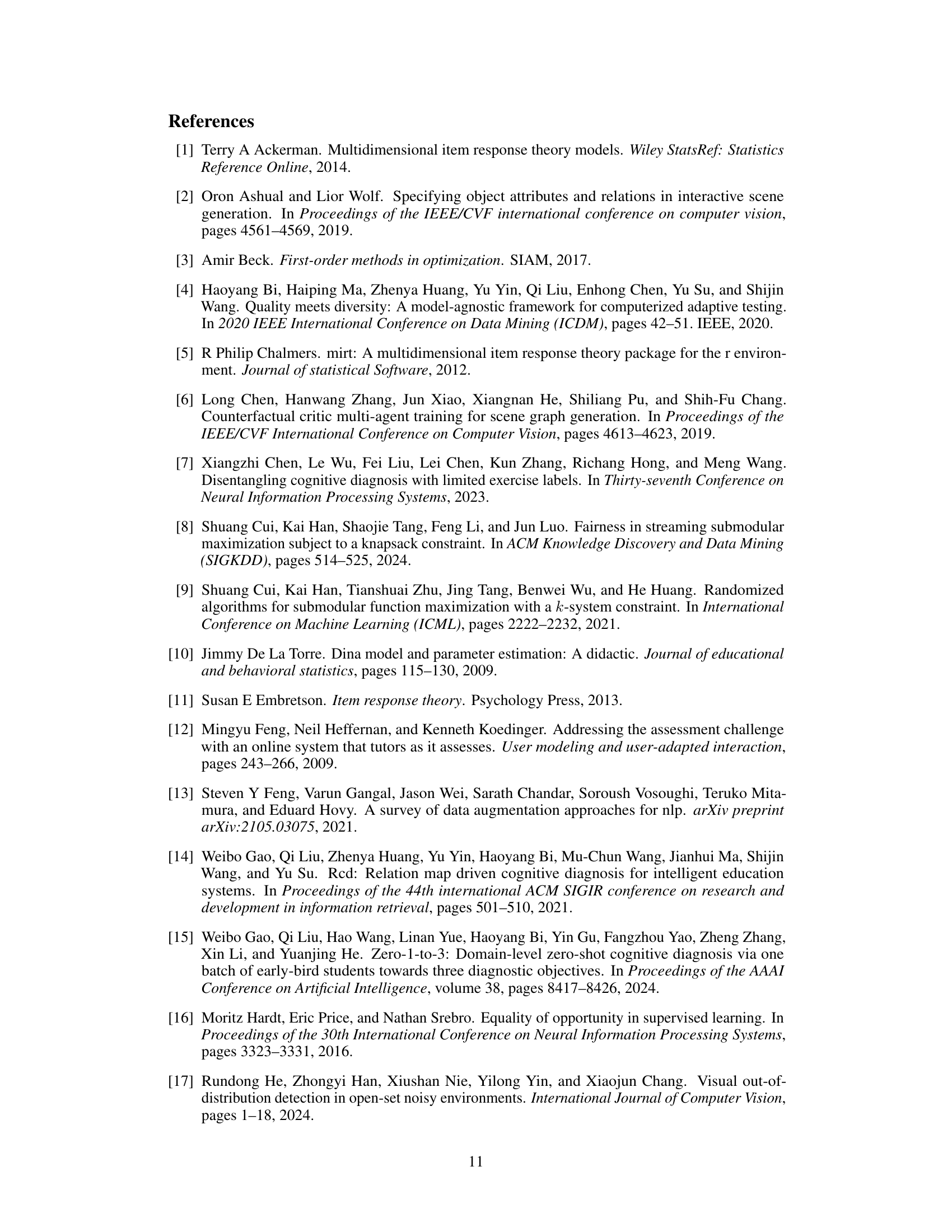

More on tables

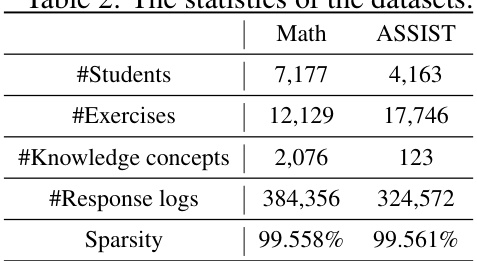

This table presents the key statistics for the Math and ASSIST datasets used in the paper’s experiments. It shows the number of students, exercises, knowledge concepts, and response logs for each dataset. Critically, it also highlights the sparsity of the data, indicating a high percentage of students interacting with a limited number of exercises, which is a central problem addressed in the paper.

This table presents the performance evaluation results of different methods on the Math dataset. It shows the utility (RMSE, MAE, AUC, ACC) and fairness (ARMSE, AMAE, AUC, AACC) for various models (Origin, CD+Reg, CD+EO, CD+DP, CF-IRT, CF-MIRT, CF-NCDM, and CMCD). The best performance for each metric and each model is highlighted in bold. Statistical significance (p-values) comparing CMCD against the Origin method are provided, using t-test results (* * * : p < 0.001, ** : p < 0.01, * : p < 0.05).

Full paper#