↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Discovering new molecules with desired properties is computationally expensive due to the cost of evaluating the reward function. Deep learning-based generative methods show promise but struggle with sample efficiency. Classical methods, particularly genetic algorithms (GAs), often outperform recent deep learning methods when sample efficiency is a priority. This paper introduces Genetic GFN, a novel algorithm that addresses these challenges.

Genetic GFN cleverly incorporates domain knowledge from GAs into GFlowNets, an off-policy method for amortized inference. This allows the deep generative policy to learn effectively from domain knowledge, enhancing sample efficiency. The method significantly outperforms existing techniques on the PMO benchmark, a standard evaluation suite for molecular optimization. The algorithm demonstrates effectiveness in designing SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors using substantially fewer reward calls.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly improves the sample efficiency of molecular optimization, a crucial task in drug discovery and material science. The Genetic GFN algorithm combines the strengths of genetic algorithms and GFlowNets, leading to state-of-the-art results on established benchmarks. This work opens new avenues for researchers to design molecules with desired properties using fewer computational resources, accelerating the pace of scientific discovery. The integration of domain knowledge from genetic algorithms into deep learning models is a significant contribution, suggesting a new approach for enhancing sample efficiency in other domains beyond molecule design.

Visual Insights#

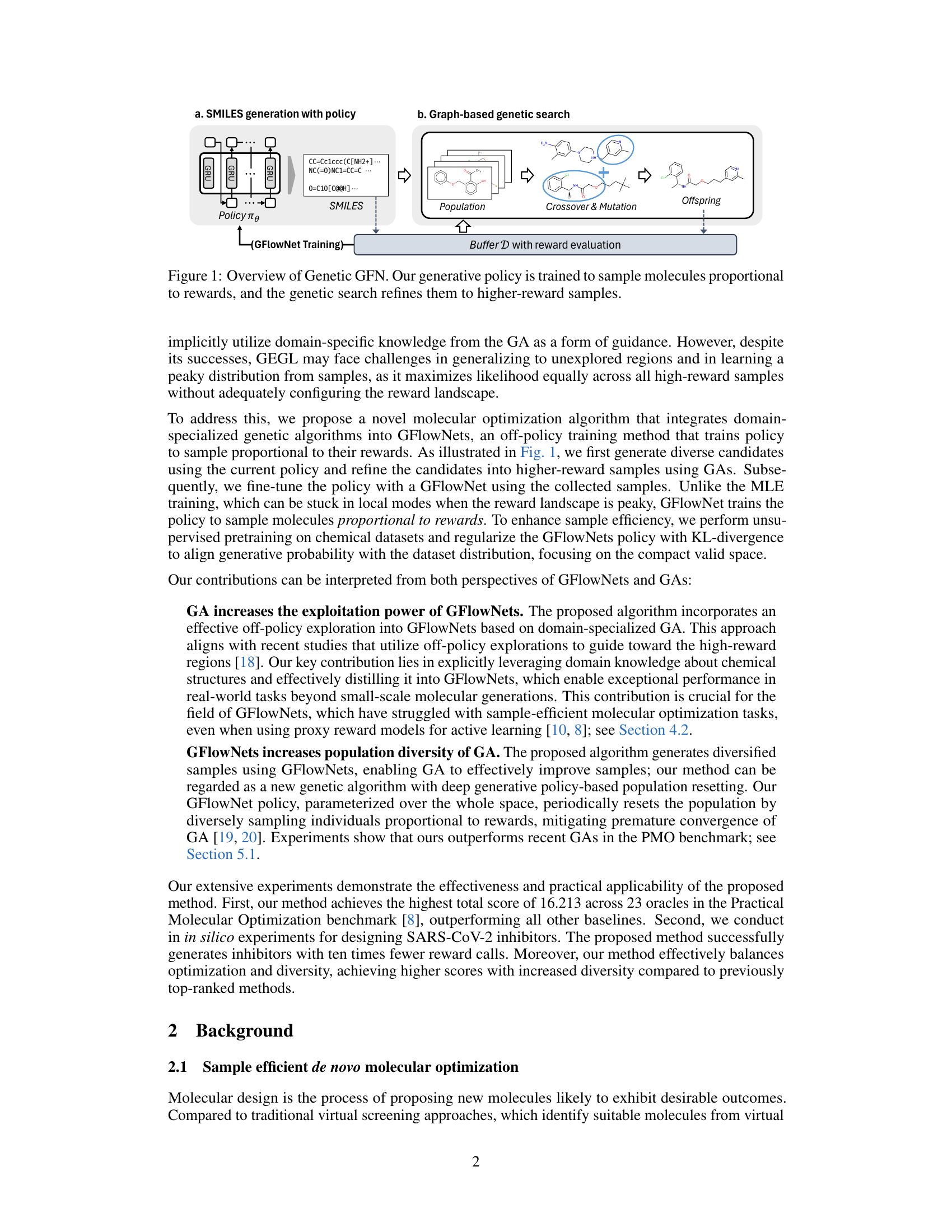

This figure shows the overall framework of Genetic GFN, which consists of two main parts: SMILES generation with policy and graph-based genetic search. The SMILES generation part uses a recurrent neural network (RNN) based policy (πθ) to generate SMILES strings representing molecules. These molecules are then evaluated using a reward function (O(x)) and are stored in a buffer (D). The graph-based genetic search part takes molecules from the buffer (D) as a population, applies crossover and mutation operations, and generates offspring molecules which are then evaluated and added to the buffer (D). The policy (πθ) is trained using GFlowNet training to sample molecules proportionally to their rewards, which helps refine the molecules to higher-reward ones.

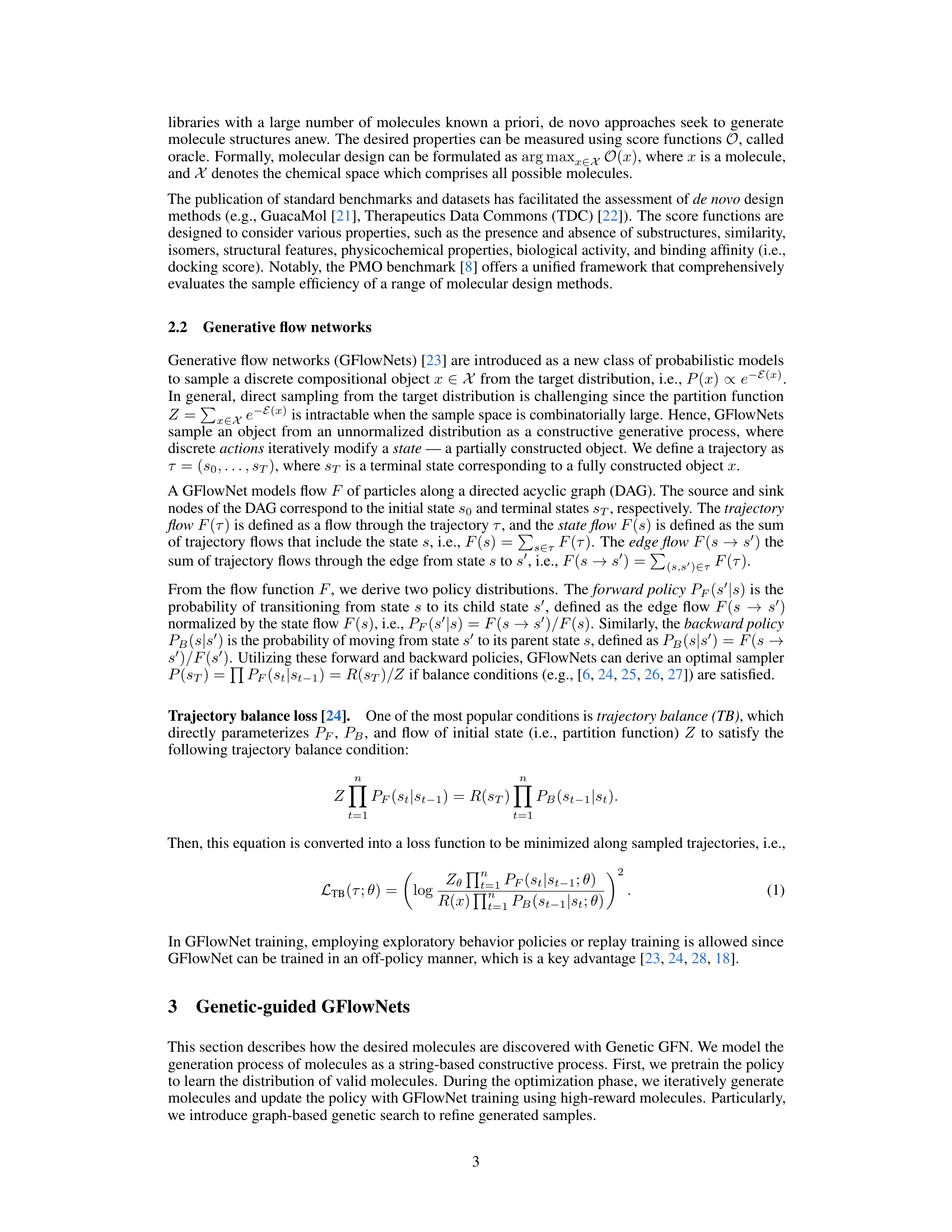

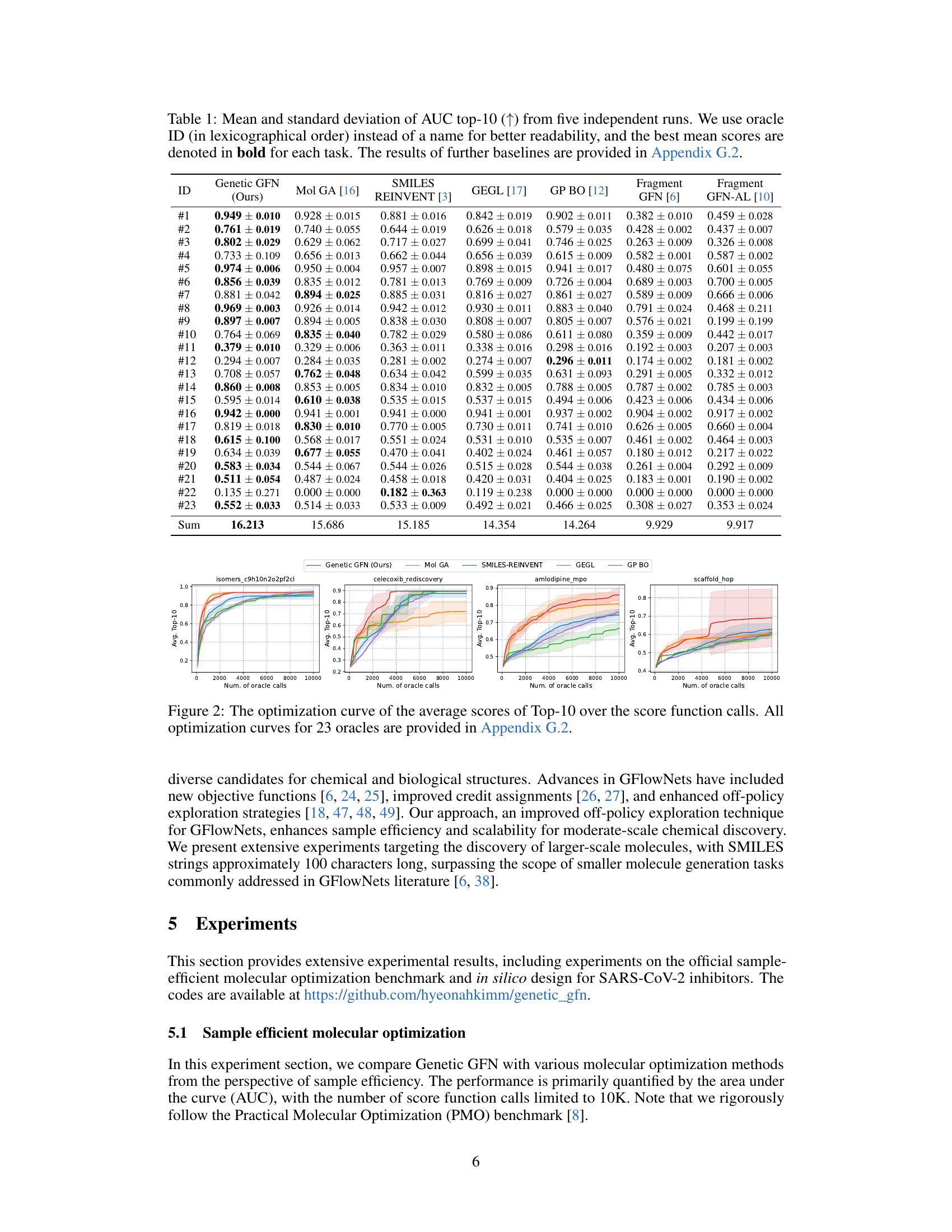

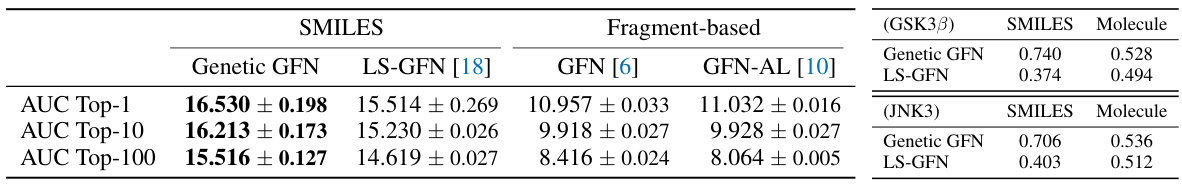

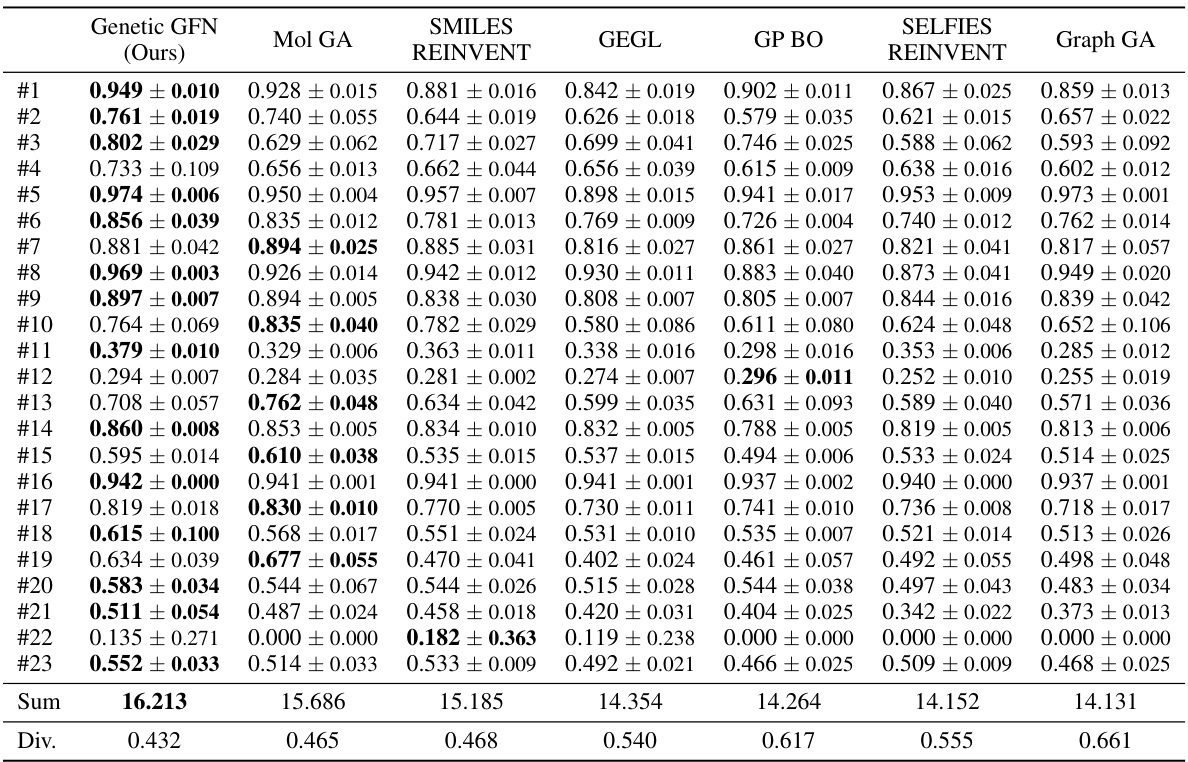

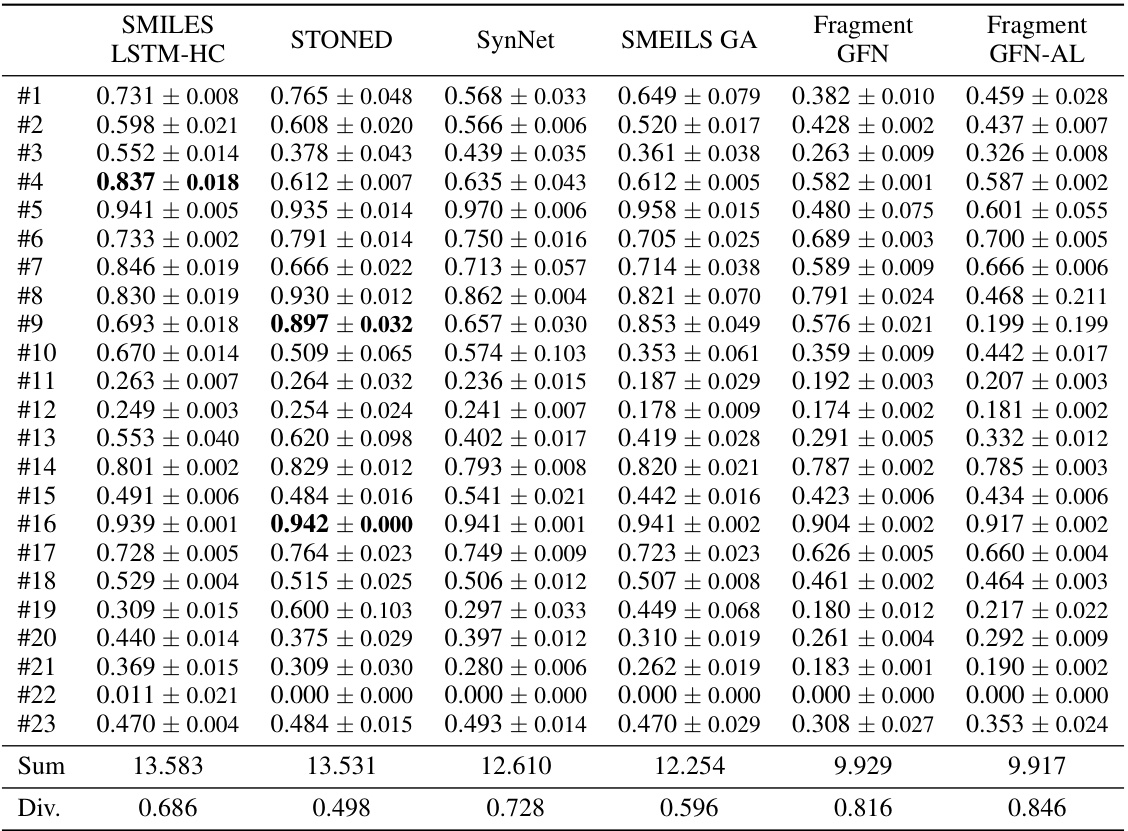

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the area under the curve (AUC) for the top 10 results obtained from five independent runs of a molecular optimization experiment using different methods. The table compares the performance of Genetic GFN against several other methods across 23 different oracle tasks. Each oracle represents a different molecular optimization problem. The best average AUC scores are highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

Genetic GFN: Core Idea#

Genetic GFN represents a novel approach to sample-efficient molecular optimization by integrating the strengths of genetic algorithms (GAs) and generative flow networks (GFlowNets). The core idea is to leverage the domain expertise encoded within GAs to enhance the exploration capabilities of GFlowNets. Instead of relying solely on the GFlowNet to navigate the complex chemical space, the algorithm uses a GA to iteratively refine molecules generated by the GFlowNet, pushing the policy towards higher-reward regions. This synergistic combination tackles the limitations of each individual method: GAs’ exploration power is amplified by the GFlowNet’s ability to sample proportionally to rewards, while GFlowNets’ potential for getting stuck in local optima is mitigated by the GA’s global search ability. Off-policy training of the GFlowNet using the refined samples further improves sample efficiency and enables effective learning from the limited reward evaluations. This approach yields significant improvements in molecular optimization benchmarks, showcasing the power of combining deep learning methods with classical techniques for complex, real-world problems.

Sample Efficiency Gains#

The concept of ‘Sample Efficiency Gains’ in a machine learning context, particularly within molecular optimization, centers on reducing the number of expensive reward function evaluations needed to train a model effectively. This is crucial because evaluating molecular properties (e.g., binding affinity, toxicity) can be computationally costly and time-consuming. Strategies to achieve sample efficiency gains often involve techniques like active learning, where the model strategically selects samples to query for labels; transfer learning, leveraging knowledge from related tasks or datasets; meta-learning, allowing the model to learn how to learn more efficiently; incorporating domain knowledge, for example by using genetic algorithms or other heuristic methods to guide the search space exploration; and improved model architectures and training algorithms, which can converge faster and generalize better. Genetic algorithms (GAs), for instance, are used due to their ability to efficiently explore the vast search space by mimicking natural selection, generating high-reward molecules. The effectiveness of a sample-efficient method is typically measured by comparing the performance achieved with a limited number of samples against methods that require substantially more samples. Significant sample efficiency gains translate to faster and more cost-effective molecular discovery and optimization.

SARS-CoV-2 Inhibitors#

The research explores the design of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors using a novel Genetic GFN method. The focus is on sample efficiency, a crucial factor given the computational cost of evaluating molecules. The approach integrates a genetic algorithm with GFlowNets, effectively leveraging domain-specific knowledge for efficient exploration of chemical space. In-silico experiments targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteins (PLPro_7JIR and RdRp_6YYT) demonstrate the method’s effectiveness in generating high-scoring inhibitors using significantly fewer reward calls than baselines. The study highlights the synergy between Genetic Algorithms and GFlowNets, showing how the combined approach can overcome the sample efficiency challenge inherent in molecular optimization. The results showcase superior performance compared to existing methods, underlining the potential of Genetic GFN for accelerating drug discovery. The ability to control the exploration-exploitation trade-off is also emphasized, indicating adaptability for various optimization needs. While promising, future work should focus on expanding the method’s applicability beyond SARS-CoV-2 and addressing limitations such as reliance on effective genetic algorithms.

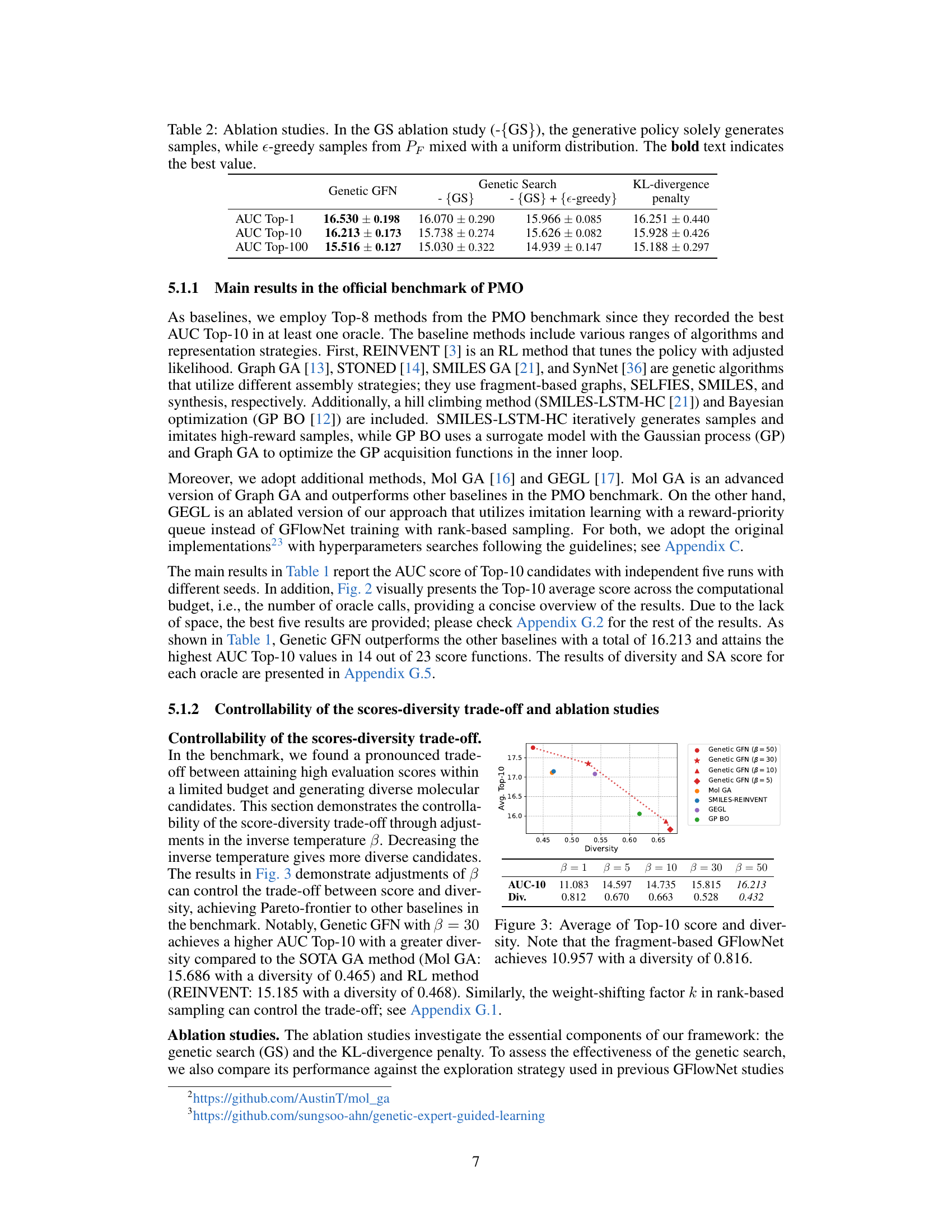

Ablation Study Results#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, an ‘Ablation Study Results’ section would present findings showing the impact of removing or altering specific elements. Key insights would focus on the relative importance of different components, such as the contribution of a genetic algorithm versus a deep learning model. The results might demonstrate that removing the genetic algorithm significantly reduces performance, highlighting its crucial role in the proposed method. Conversely, if removing a specific regularization technique has minimal impact, it suggests that technique is not essential. A thoughtful analysis would include not only quantitative results, like performance metrics (AUC, accuracy etc.), but also a qualitative interpretation of the effects on diversity and exploration. For example, removing a particular component might lead to a decrease in the diversity of molecules generated. Well-designed ablation studies are critical for understanding the interplay of different components within a complex model and for justifying design choices. The discussion section should highlight both the expected and unexpected effects of the ablations, providing a comprehensive understanding of the system’s behavior.

Future Research Plans#

Future research could explore extending the Genetic GFN framework to other domains beyond molecular optimization, leveraging the power of genetic algorithms and off-policy learning. Adapting the approach for combinatorial optimization problems, such as those in logistics or resource allocation, would be a significant step. Investigating different genetic operators and their impact on sample efficiency is another crucial area. Further exploration into multi-objective optimization with more sophisticated techniques for handling trade-offs between competing objectives could improve the design of molecules with multiple desired properties. Additionally, research into more efficient reward function approximations or the development of more effective proxy models could drastically improve overall performance and reduce computational cost. Applying the method to larger-scale molecule generation tasks would test the scalability and robustness of Genetic GFN. Finally, a thorough analysis of the method’s limitations, especially concerning the generalizability across various chemical spaces, is essential for practical applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

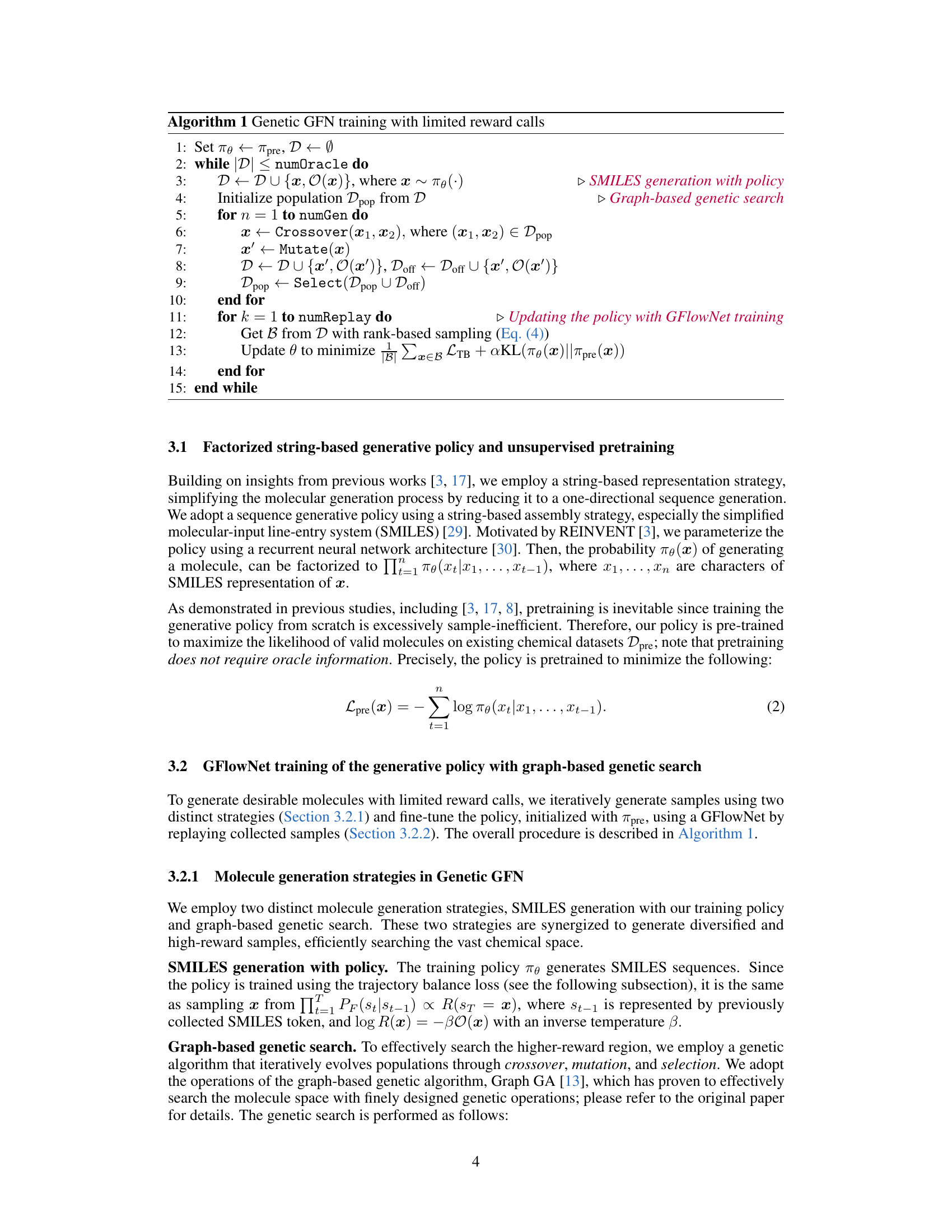

This figure shows the performance of Genetic GFN and other methods across 23 different molecular optimization tasks. The y-axis represents the average Top-10 scores, and the x-axis represents the number of oracle calls (computational cost). Each line represents a different method, showing how their average Top-10 scores improve with increasing computational budget. The shaded areas represent the standard deviations. Appendix G.2 contains more detailed optimization curves for each of the 23 oracles.

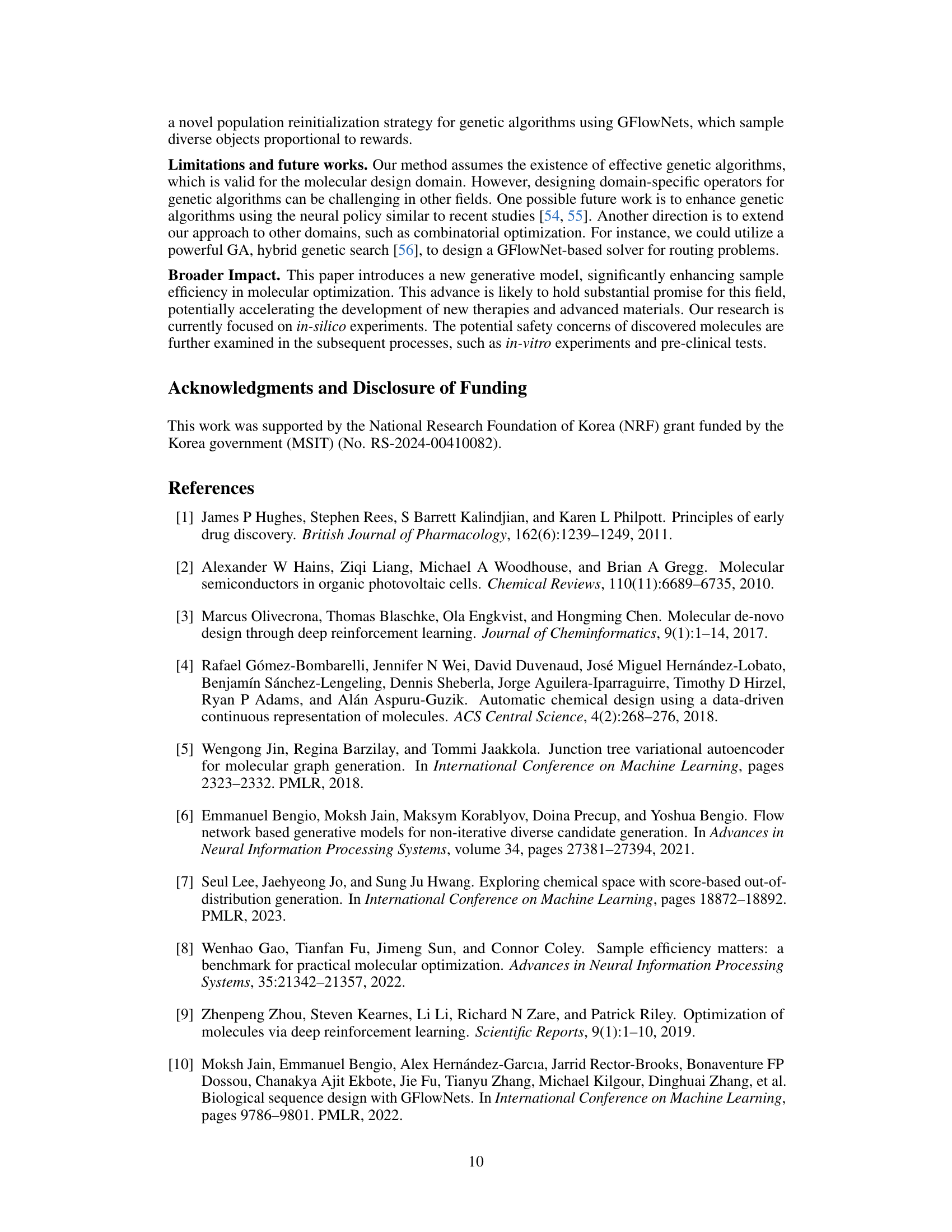

This figure shows the relationship between the average Top-10 score and diversity for various methods. The x-axis represents diversity, a measure of how different the generated molecules are, while the y-axis represents the average Top-10 score achieved by each method. The plot illustrates that Genetic GFN achieves a high score with a relatively high level of diversity, demonstrating its ability to generate both high-quality and diverse molecular candidates. For comparison, other algorithms are included, such as Mol GA, SMILES-REINVENT, GEGL, GP BO, etc. The fragment-based GFlowNet is also included as a point of comparison showing that Genetic GFN outperforms other methods.

This figure shows the top three molecule candidates generated by Genetic GFN for the PLPr_7JIR target after 100 optimization steps. Each molecule is depicted visually, along with its docking score, QED score, and SA score. These scores represent different aspects of the molecule’s suitability as a drug candidate, with higher docking scores indicating better binding affinity, higher QED scores indicating better drug-likeness, and lower SA scores indicating easier synthesis.

The figure illustrates the Genetic GFN framework. It consists of two main parts: SMILES generation with policy and graph-based genetic search. The generative policy (trained using GFlowNet) samples molecules. These molecules are then refined by a genetic algorithm to increase their rewards. This process iteratively improves the policy by learning from high-reward samples. The left side shows the generation of SMILES strings using the policy, while the right side depicts the genetic search operating on a population of molecules and producing improved molecules which in turn update the policy.

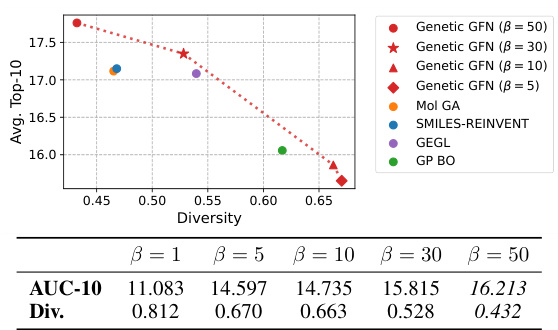

This figure shows examples of genetic operations used in the paper’s proposed Genetic GFN algorithm. These operations, based on Graph GA, manipulate molecular structures by performing crossover (ring and non-ring) and mutation. Crossover involves exchanging parts of two molecules, while mutation introduces small, random changes (e.g., adding, removing, or modifying atoms and bonds). The operations are guided by predefined SMARTS (simplified molecular-input line-entry system) patterns to ensure the resulting molecules are chemically valid.

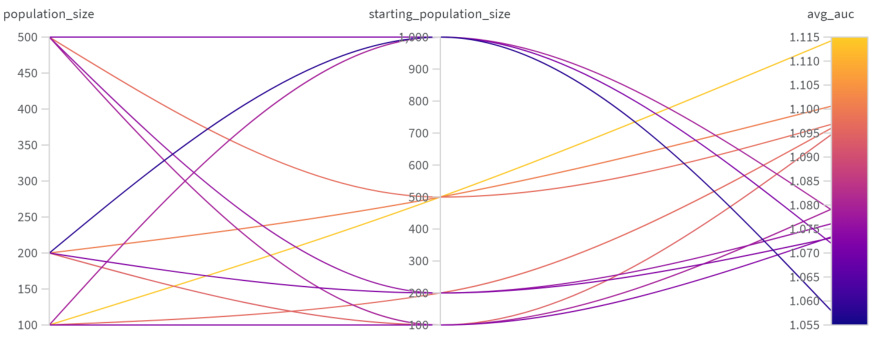

This figure shows the results of hyperparameter tuning for Mol GA (a genetic algorithm). The x and y axes represent different values for starting population size and population size, respectively. The color scale represents the average AUC (Area Under the Curve) score achieved with those hyperparameter settings. The graph helps to determine the optimal combination of starting population size and population size to maximize the AUC score.

The figure shows the results of hyperparameter tuning for the GEGL model. The x and y axes represent different values for the expert sampling batch size and priority queue size, respectively. The color scale represents the average AUC (Area Under the Curve) score obtained for different hyperparameter combinations. The plot helps to identify the optimal hyperparameter settings that maximize the model’s performance.

This figure shows the top three inhibitor candidates generated for SARS-CoV-2 targets (PLPro_7JIR and RdRp_6YYT) at different stages of the optimization process (50, 100, 500, and 1000 steps). Each molecule’s structure is displayed, along with the number of steps required to reach that particular structure. The figure illustrates the progression of the algorithm towards generating more effective inhibitor molecules.

This figure shows the relationship between the average Top-10 score and diversity with adjustments of the weight-shifting factor k in the rank-based reweighted buffer. The inverse temperature β is held fixed. Different colored markers represent different values of k used with Genetic GFN. The plot also includes scores and diversity from other methods for comparison: Mol GA, SMILES-REINVENT, GEGL, and GP BO. The trend shows that as k increases, diversity increases but the average score decreases, illustrating the score-diversity trade-off.

This figure shows the performance of Genetic GFN and other methods across 23 different tasks in terms of average top-10 scores over the number of oracle calls. It illustrates the sample efficiency of Genetic GFN compared to other methods by plotting the average top-10 scores achieved against the number of oracle calls used. The shaded areas represent the standard deviation across five independent runs. Appendix G.2 contains the full set of curves for all 23 oracles.

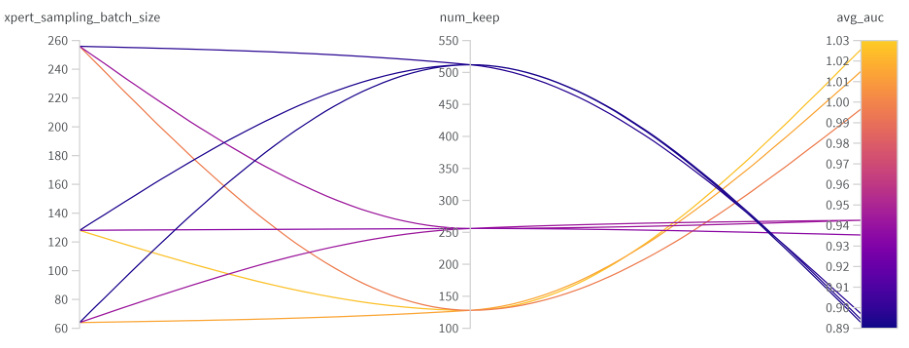

This figure shows examples of molecules generated by REINVENT and Genetic GFN that achieved non-zero scores on the valsartan_smarts oracle. The valsartan_smarts oracle is a challenging benchmark because it requires molecules to contain a specific substructure (related to valsartan) while also meeting certain physicochemical property criteria. The figure highlights that both methods were able to generate molecules satisfying these criteria, demonstrating their ability to navigate complex chemical space constraints, but that the resulting molecules differ significantly between methods.

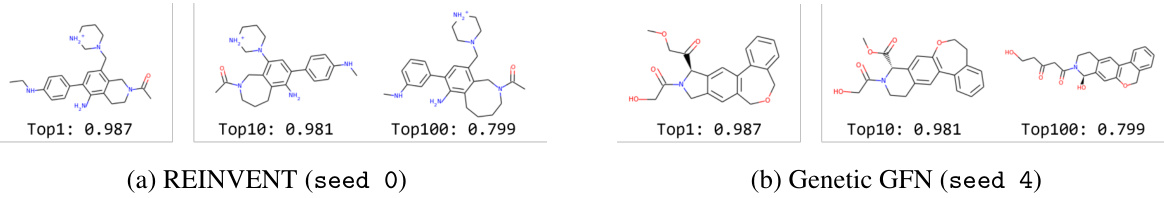

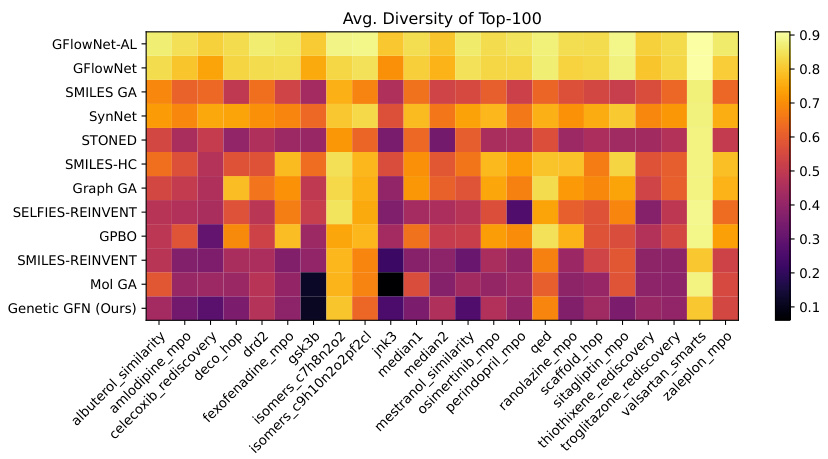

This heatmap visualizes the average diversity of the top 100 molecules generated by different methods across various oracle tasks in the PMO benchmark. Each cell represents the average diversity for a specific method and oracle. The color intensity reflects the diversity level, with darker colors indicating higher diversity.

This heatmap visualizes the average diversity scores of the top 100 molecules generated by different methods across various oracle functions in the PMO benchmark. Higher values indicate greater diversity. The figure helps illustrate how Genetic GFN compares to other methods in terms of the diversity of molecules generated.

More on tables

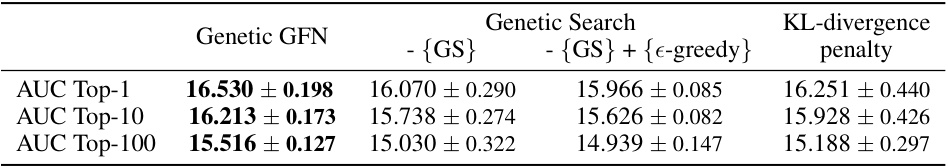

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of the genetic search (GS) and KL-divergence penalty on the performance of the proposed Genetic GFN model. The ablation studies systematically remove components of the model to isolate their individual contributions to overall performance. The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation of AUC scores for Top-1, Top-10 and Top-100 molecules across various oracles. The table shows that both genetic search and KL-divergence penalty significantly improve the model’s performance.

This table compares the performance of Genetic GFN with three GFlowNet variants: LS-GFN, GFN, and GFN-AL. The comparison is done using two metrics (AUC scores and search distances) and two tasks (GSK3β and JNK3). The results show that Genetic GFN outperforms other methods, particularly in terms of sample efficiency, highlighted by larger SMILES distances in the genetic search compared to the local search. The bolded values indicate the best results for each metric in each task.

This table presents the results of a multi-objective molecular optimization experiment comparing Genetic GFN’s performance to several baselines. Two tasks were evaluated: GSK3β + JNK3 and GSK3β + JNK3 + QED + SA. The hypervolume metric is used to evaluate performance, which considers both the quality and diversity of solutions found by each algorithm. The results show Genetic GFN outperforming the other methods on both tasks.

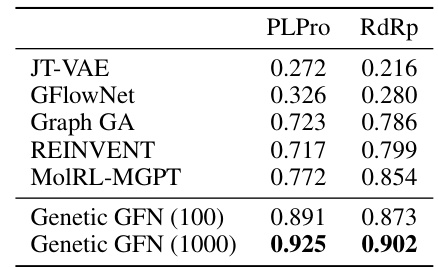

This table compares the average top-100 scores achieved by Genetic GFN against several baselines on two SARS-CoV-2 targets (PLPro and RdRp) using only 100 and 1000 steps. The results show that Genetic GFN significantly outperforms all the baselines, achieving much higher scores with drastically fewer steps. This demonstrates the efficiency of the proposed Genetic GFN approach in designing SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors.

This table compares the hyperparameters used in the Genetic GFN-AL model with those used in the GFlowNet-AL model from the PMO benchmark. It highlights key differences in settings such as proxy sample size, training iterations, hidden dimension, and exploration strategies (kappa, gamma, random action probability). These differences reflect the adaptations made to the GFlowNet-AL framework to incorporate Genetic GFN’s unique approach.

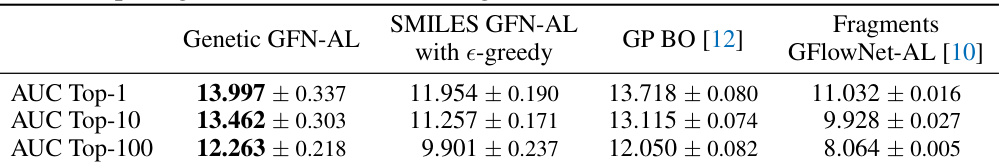

This table compares the performance of Genetic GFN-AL with other active learning and model-based algorithms in terms of AUC Top-1, AUC Top-10, and AUC Top-100. It highlights the superior performance of Genetic GFN-AL, especially compared to the fragment-based GFlowNet-AL which serves as a baseline for active learning approaches.

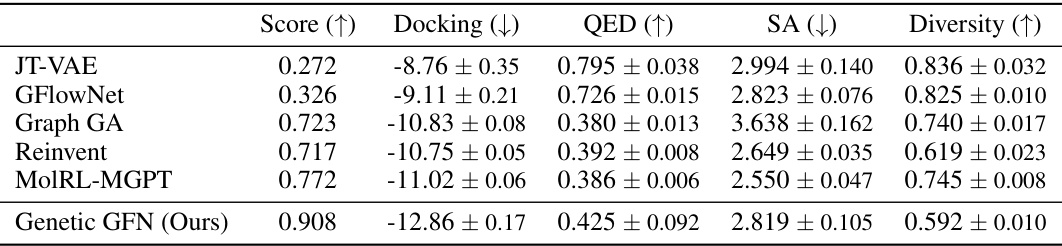

This table presents the performance of different methods in predicting the docking, QED, SA, and diversity scores for the top-100 molecules targeting PLPr_7JIR. The ‘Score’ column represents a combined metric calculated using a specific formula (Eq. 5 in the paper). The baselines’ docking, QED, and SA values are taken directly from the MolRL-MGPT paper, while Genetic GFN’s results are original to this paper.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods in terms of docking score, QED, SA, and diversity for the RdRp_6YYT target in the SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor design task. The scores are calculated using a specific formula, and the baselines’ docking, QED, and SA values are taken directly from a previous study (MolRL-MGPT).

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the AUC (Area Under the Curve) for the top-10 results from five independent runs of a molecular optimization experiment. The experiment used 23 different oracle functions (tasks) to evaluate the performance of different methods. The best mean score for each task is highlighted in bold. Additional results from other baselines are included in Appendix G.2.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the top 10 results from five independent runs of a molecular optimization experiment. It compares the performance of Genetic GFN against several other methods across 23 different tasks (oracles). The best performing method for each task is highlighted in bold. Additional baseline results are available in Appendix G.2.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the top 10 results from five independent runs of a molecular optimization experiment. It compares the performance of Genetic GFN against several other methods across 23 different oracle tasks (molecular properties to optimize). The best performing method for each task is highlighted in bold. Appendix G.2 contains results for additional baseline methods.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the top 10 results from five independent runs of a molecular optimization experiment. The results are shown for a genetic GFlowNet model and several comparison methods across 23 different oracle tasks. The best mean score for each task is highlighted in bold. Further baseline results are available in Appendix G.2.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the top 10 results from five independent runs of a molecular optimization experiment. It compares the performance of Genetic GFN against several other methods across 23 different tasks (oracles). The best-performing method for each task is highlighted in bold. Additional results for other methods are available in Appendix G.2 of the paper.

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of the genetic search (GS) and the KL-divergence penalty on the performance of the proposed Genetic GFN model. The ablation studies involve removing either the genetic search component or the KL-divergence penalty from the model, and also includes a variation that replaces the genetic search with an epsilon-greedy exploration strategy. The table shows the average AUC scores (Top-1, Top-10, and Top-100) for each ablation variation across multiple runs. The best-performing configuration is highlighted in bold.

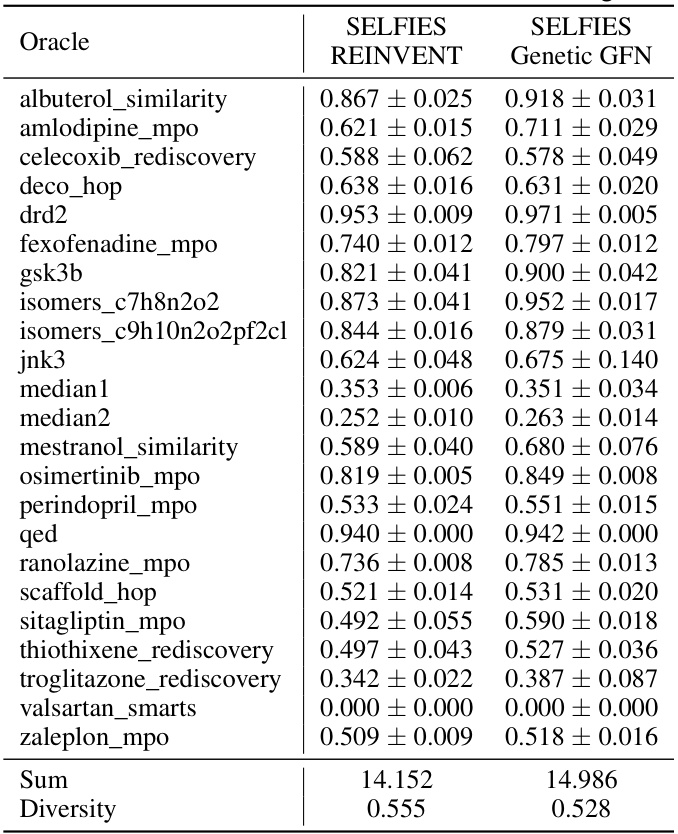

This table presents a comparison of the performance of Genetic GFN using SELFIES representation against REINVENT with SELFIES across various oracles. The table shows the average AUC scores (along with standard deviation) for both methods across each of the specified benchmark tasks, and summarizes the total AUC and diversity scores.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the AUC top-10 scores across five independent runs for each of the 23 oracles in the PMO benchmark. The best average score for each oracle is highlighted in bold. Additional results for other baselines are available in Appendix G.2.

This table presents the ablation study results by varying the number of GA generations. The results show the performance of Genetic GFN with 0, 1, 2 and 3 GA generations, comparing AUC Top-1, AUC Top-10, AUC Top-100 and diversity for each configuration. The ‘x0’ row indicates the results without using GA exploration during training.

This table shows the performance comparison of Genetic GFN with other state-of-the-art molecular optimization methods across 23 different tasks in the PMO benchmark. The AUC Top-10 score, a metric representing sample efficiency, is reported, along with its standard deviation, for each method across each task. The best mean score for each task is highlighted in bold. Appendix G.2 provides a more comprehensive set of results.

This table presents the ablation study results by varying the number of training inner loops in the Genetic GFN model. It shows the impact of this hyperparameter on AUC Top-1, AUC Top-10, AUC Top-100, and diversity metrics, providing insight into the model’s performance and diversity at different training extents.

Full paper#