↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Predicting charge density is crucial in density functional theory (DFT), a computational method for studying the electronic structure of molecules and materials. However, conventional DFT methods are computationally expensive, limiting their applicability to large systems. Machine learning (ML) offers a promising alternative, but existing ML approaches struggle with accuracy or scalability.

This paper introduces a novel ML method that uses atomic and virtual orbitals, expressive basis sets, and a high-capacity equivariant neural network architecture. This approach combines accuracy and scalability, outperforming existing methods by a significant margin. It also allows flexible efficiency-accuracy trade-offs by adjusting model and basis set sizes. The results demonstrate a significant improvement in computational efficiency and predictive accuracy, offering a powerful tool for various applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in quantum chemistry and materials science due to its significant advancement in charge density prediction. It offers a faster and more accurate method, enabling larger-scale simulations and potentially revolutionizing materials discovery workflows. The flexible efficiency-accuracy trade-offs offered by the method also expand the possibilities for various applications and computational resources.

Visual Insights#

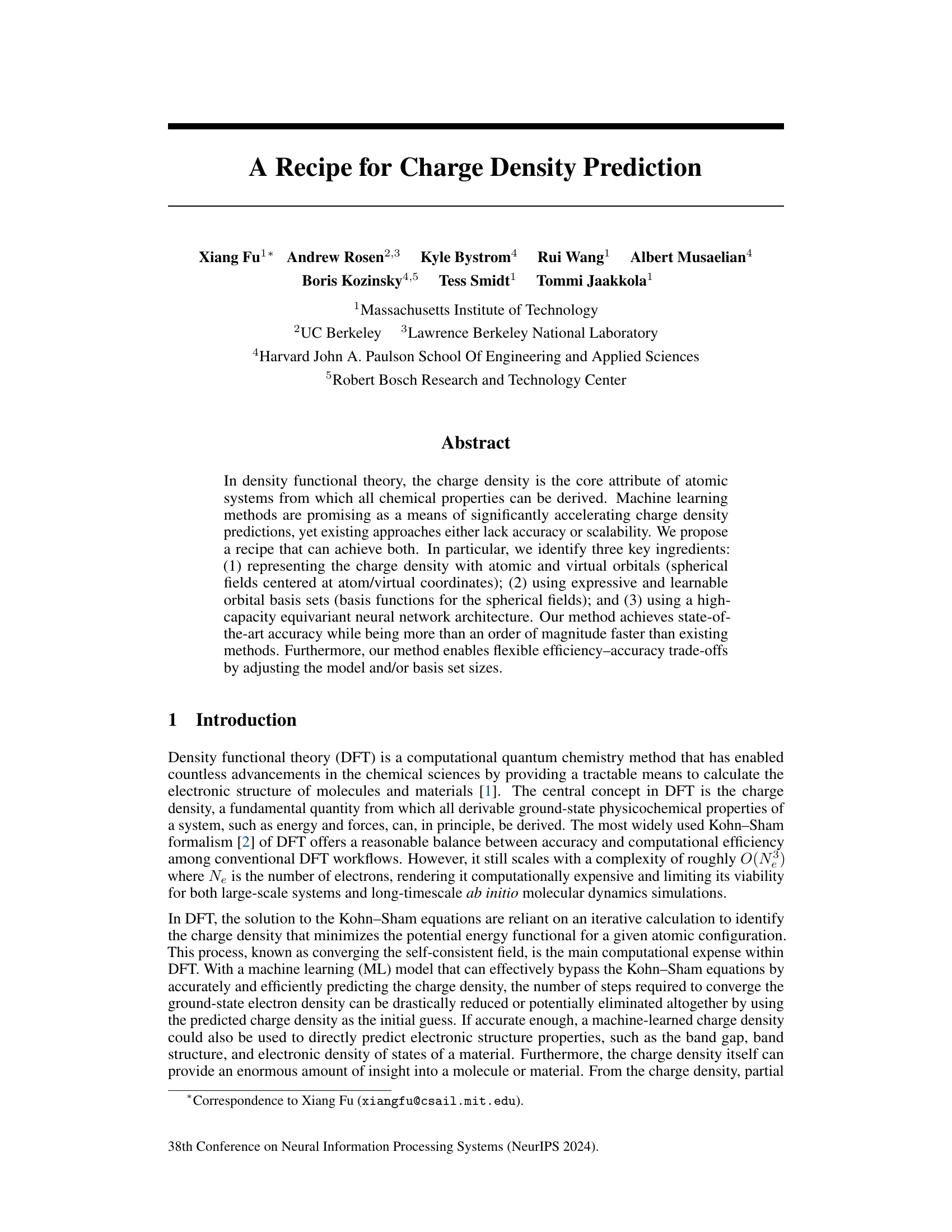

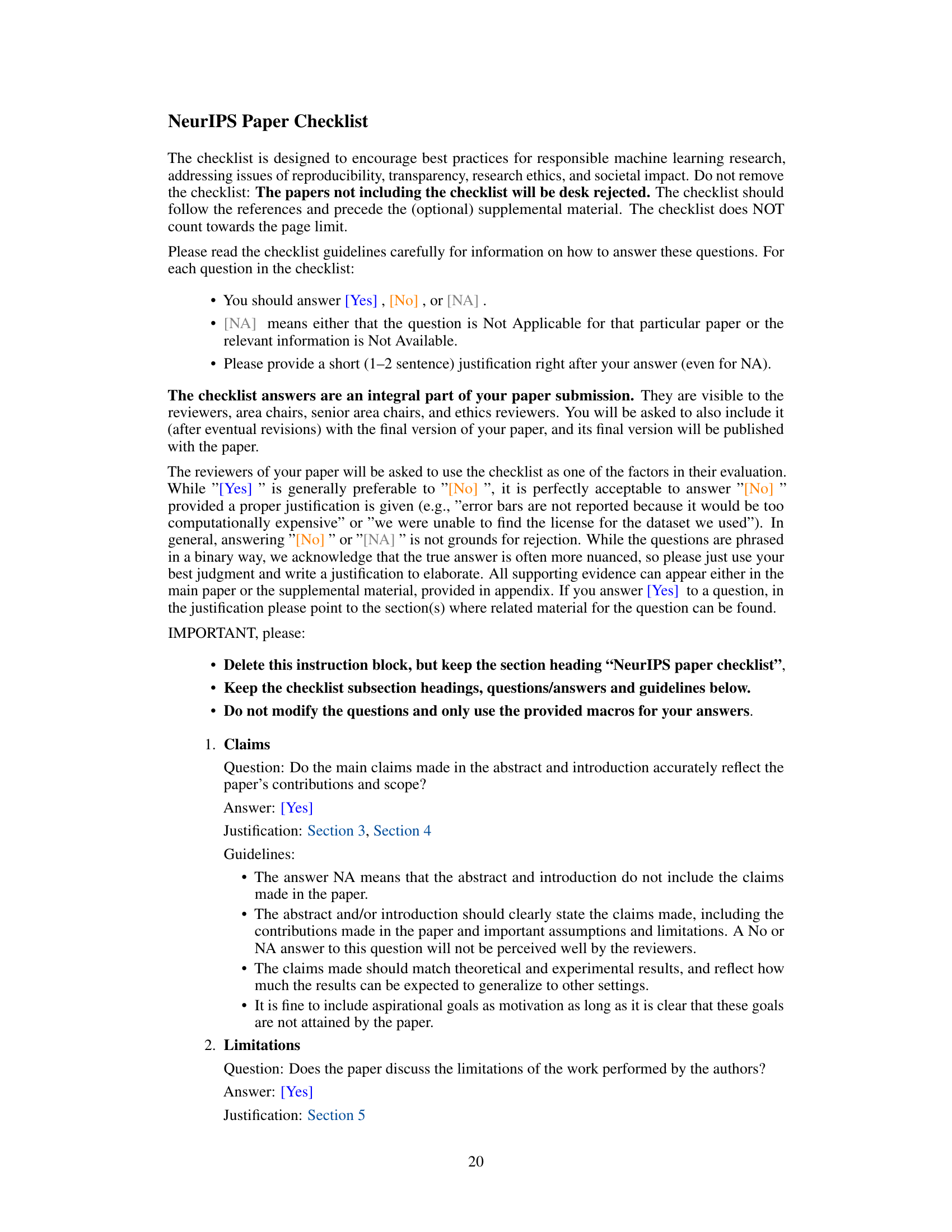

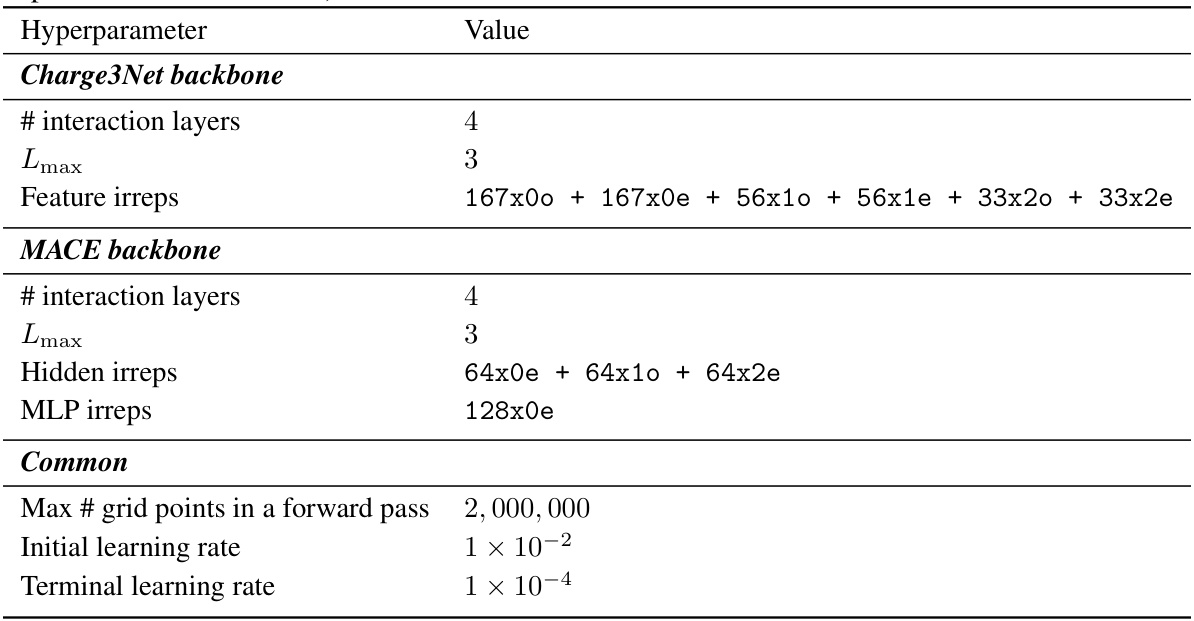

This figure illustrates two different approaches for representing charge density in machine learning models: orbital-based and probe-based. The orbital-based method represents the charge density as a sum of spherical functions centered at each atom, while the probe-based method uses a 3D grid (voxel) where each point represents the charge density. The figure highlights the difference in representation and the challenges associated with the probe-based method, especially concerning scalability due to the large number of grid points.

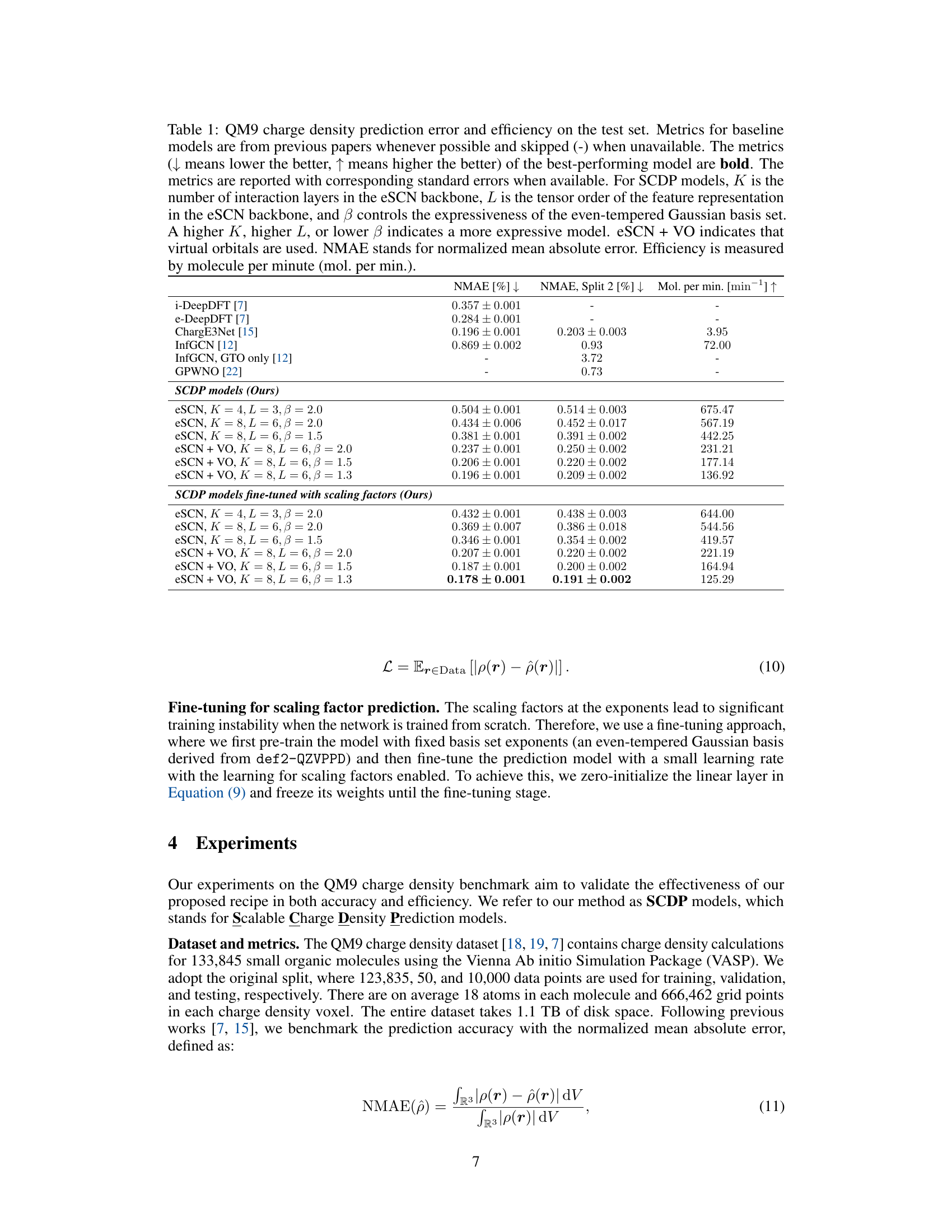

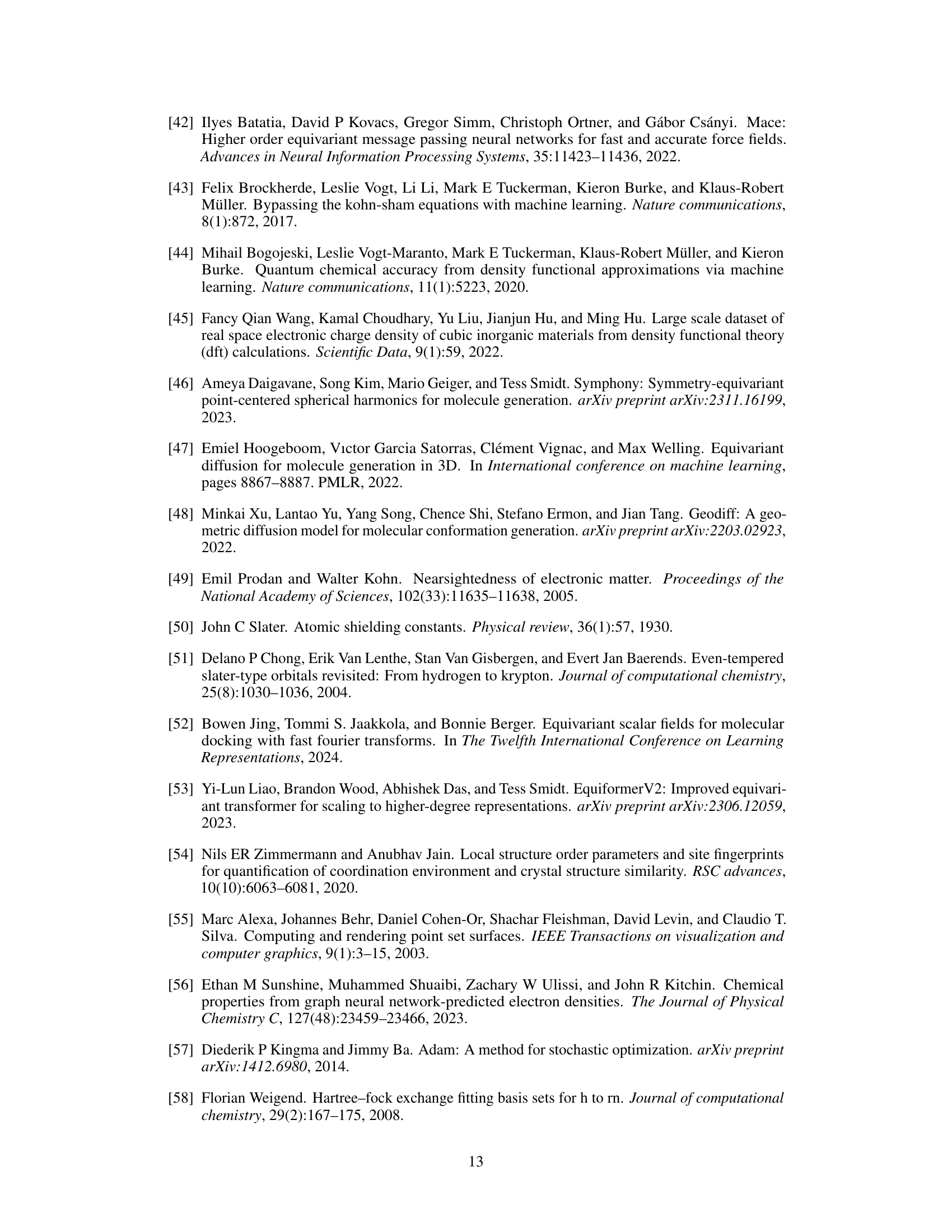

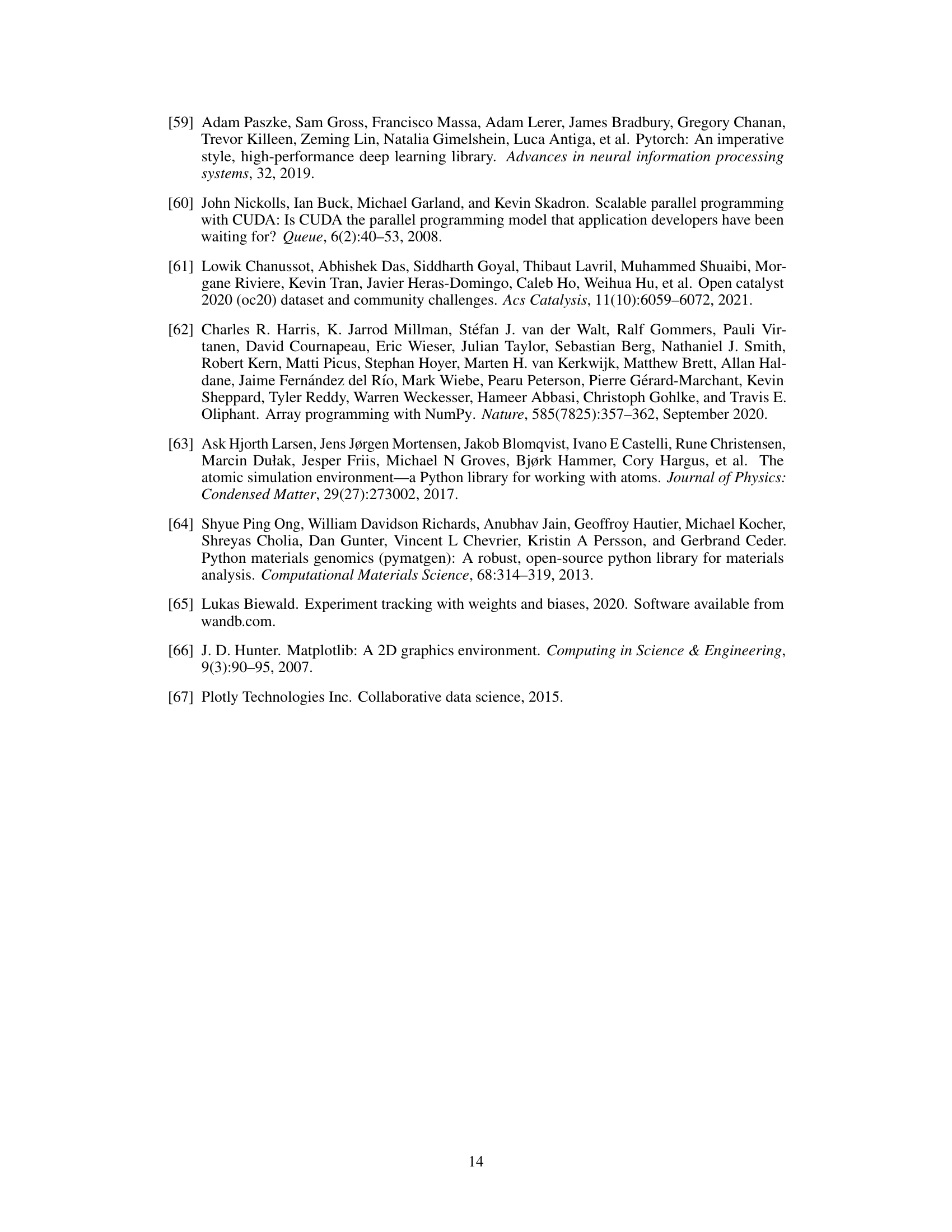

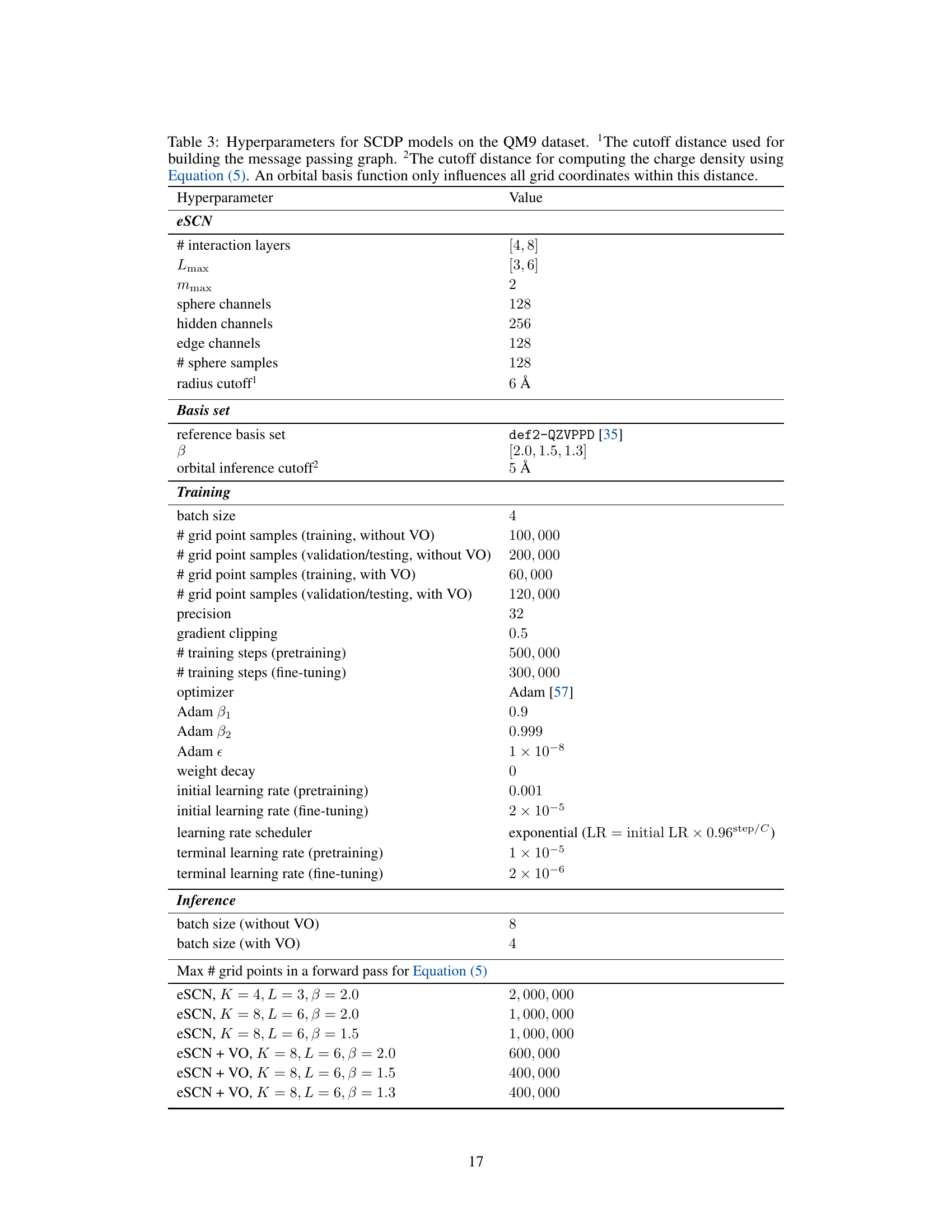

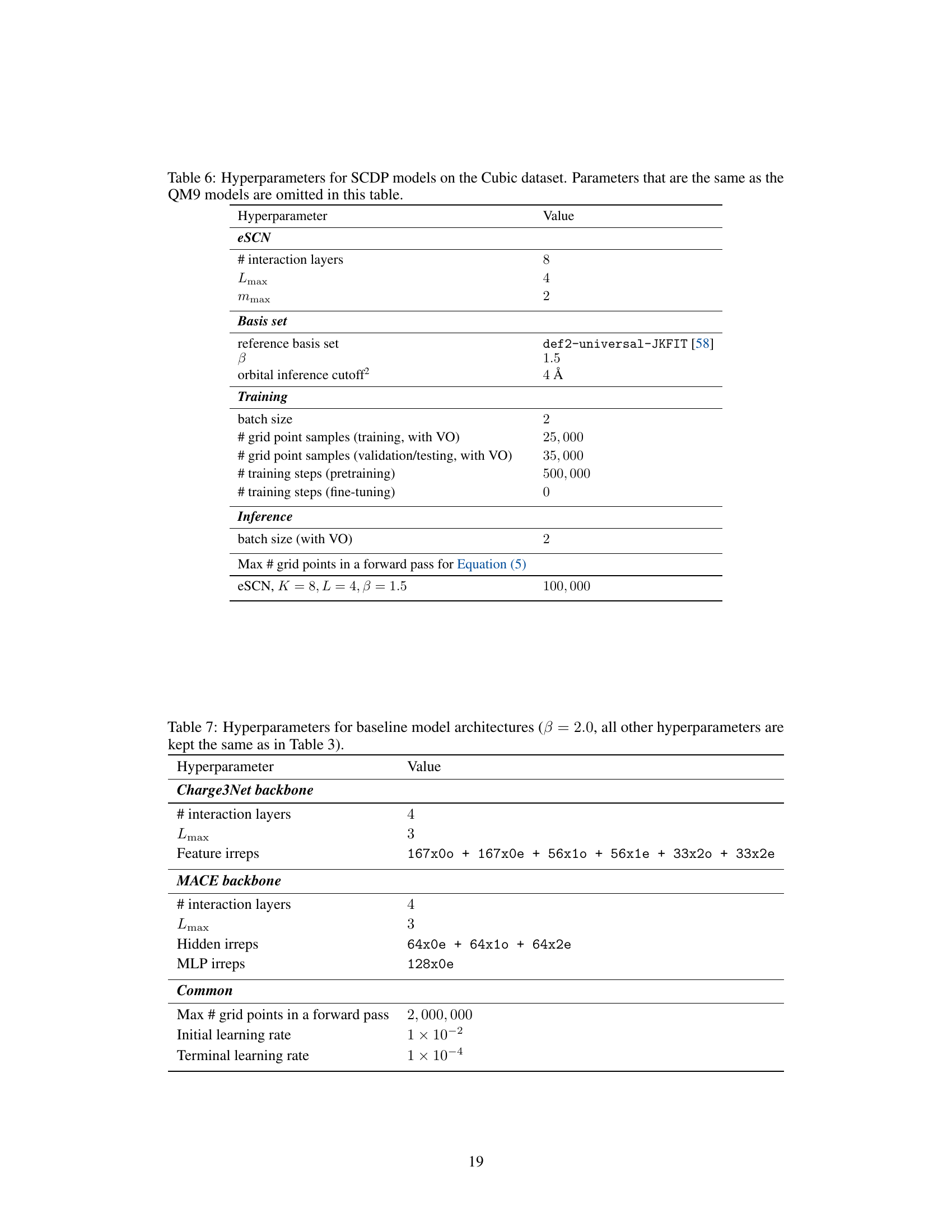

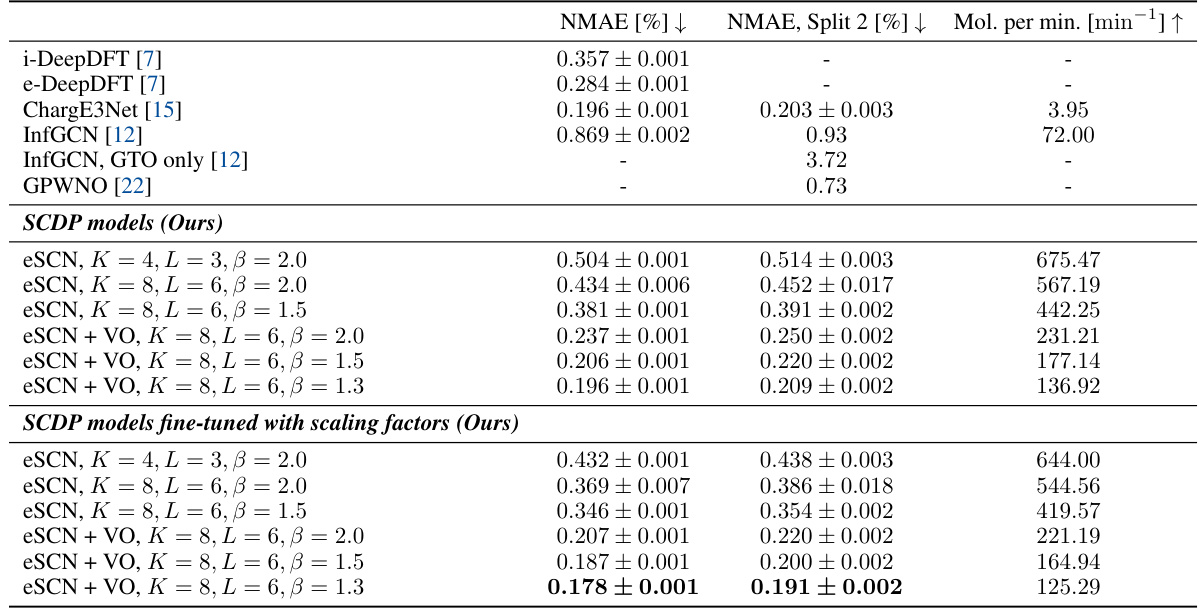

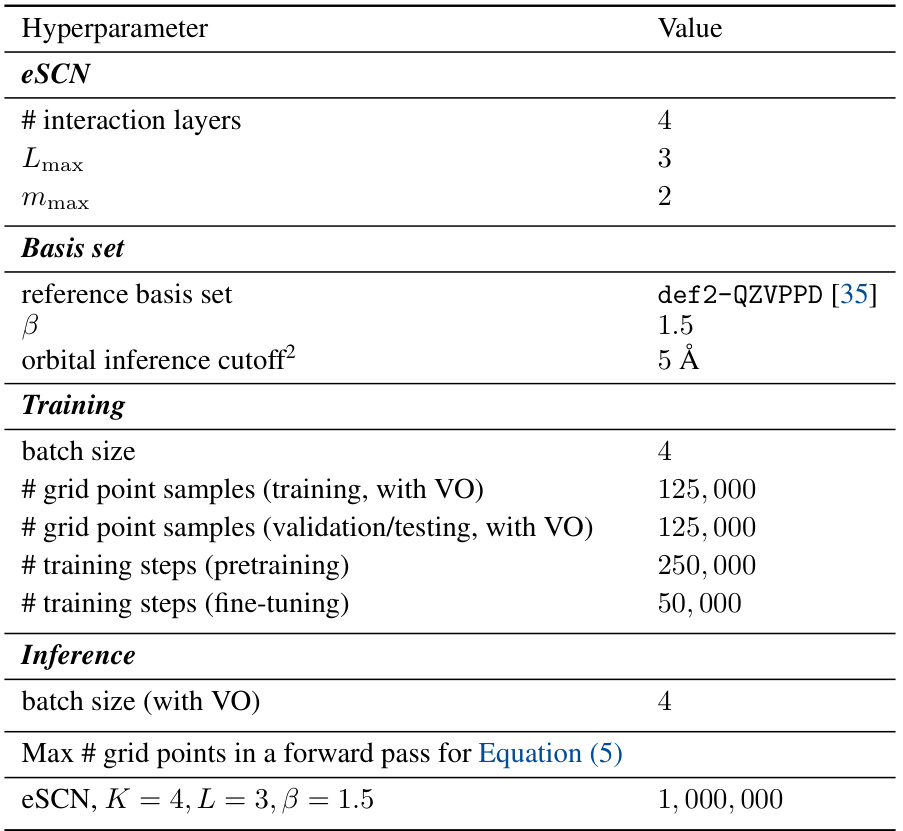

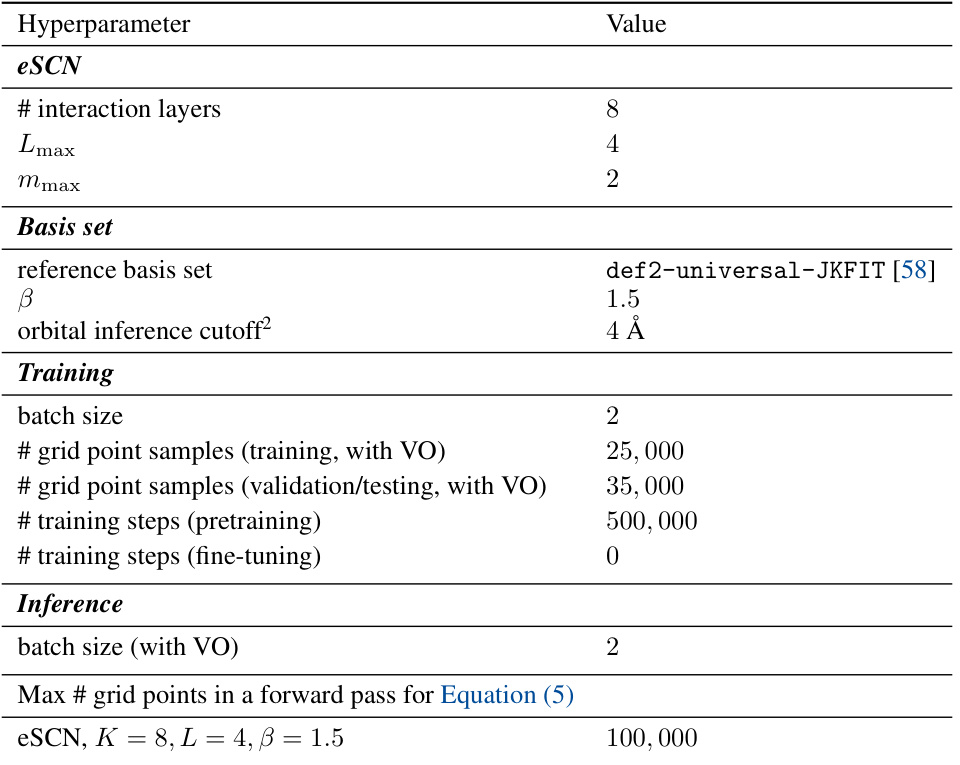

This table presents a comparison of the performance of various charge density prediction models on the QM9 dataset. The table shows the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE), NMAE on a specific split of the dataset, and the efficiency measured in molecules processed per minute. Different model configurations (varying interaction layers, tensor order, and basis set expressiveness) are compared, as well as models with and without virtual orbitals and scaling factor fine-tuning. Baseline models from previous works are also included for context.

In-depth insights#

Charge Density ML#

Charge density prediction using machine learning (ML) techniques is a rapidly evolving field in computational chemistry. The core challenge lies in balancing the efficiency and accuracy of ML models when dealing with the high-dimensional and complex nature of charge density data. Traditional methods, like density functional theory (DFT), are computationally expensive, especially for large systems. ML offers a potential solution by learning to predict charge densities directly, thus bypassing expensive DFT calculations. Key strategies involve the choice of representation (e.g., atomic orbitals, voxel grids), the architecture of the ML model (e.g., equivariant neural networks), and the training process. The effectiveness of ML approaches hinges on the selection of appropriate basis sets to capture electronic structure, and using expressive and efficient models that consider inherent symmetries of the data to improve accuracy and generalization performance. Careful consideration of both the underlying theory and the computational limitations of various ML approaches is crucial for success. Ongoing research is exploring different types of ML algorithms, basis set representations, and techniques to handle the large datasets inherent to charge density prediction to further improve the speed and accuracy of these methods. The ultimate aim is to enable efficient and accurate charge density prediction that enhances the capabilities of existing computational chemistry tools.

Equivariant Networks#

Equivariant neural networks are a powerful class of models that explicitly encode and leverage symmetries present in data. This is particularly valuable in scientific domains such as quantum chemistry and materials science where systems often exhibit rotational and translational invariance. By incorporating equivariance, these networks require less data to achieve high accuracy because they do not need to relearn these known invariances repeatedly. This leads to improved efficiency, especially crucial in high-dimensional spaces like those representing molecular geometries or materials structures. Equivariant architectures are constructed to ensure that the output transforms in a consistent way when the input undergoes a symmetry transformation. This is usually achieved by carefully designing the network layers and operations. For instance, group-convolutional layers can handle rotations naturally, while specific weight sharing strategies ensure translational equivariance. The choice of equivariant architecture is paramount to model design and depends on the specific symmetries present and computational constraints. Although more complex to implement, the benefits of reduced data requirements and improved performance in computationally expensive applications often outweigh the added development effort. Using an equivariant approach ensures that the predictions generated by the model faithfully reflect the underlying symmetry of the data, leading to more robust and physically meaningful results.

Basis Set Design#

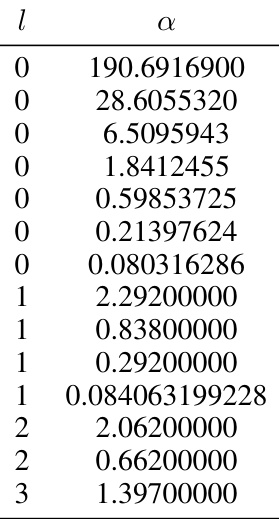

Basis set design is crucial for achieving both accuracy and efficiency in charge density prediction using machine learning. The choice of basis functions significantly impacts the model’s representational power and computational cost. Even-tempered Gaussian basis sets offer a flexible approach, allowing for smooth control over basis size and expressivity by adjusting parameters. Learnable scaling factors for orbital exponents further enhance the model’s ability to capture complex charge distributions, particularly in regions with strong interatomic interactions, despite potentially causing instability during training. Careful consideration must be given to the trade-offs between expressivity and computational efficiency. Virtual orbitals, strategically positioned, improve accuracy by enriching the model’s ability to represent non-local electronic structures; however, the selection and number of virtual orbitals require careful consideration. The use of domain-informed basis sets, such as those derived from atomic orbital basis sets like def2-QZVPPD, provides a solid foundation and allows for effective combination with even-tempered sets and scaling factors, but their limitations in representing complex regions must be addressed.

Accuracy/Efficiency#

The Accuracy/Efficiency trade-off is a central theme in machine learning, and this research is no exception. The authors present a novel method for charge density prediction that strikes a balance between accuracy and computational cost. Existing approaches often compromise on one for the sake of the other. This work uses atomic orbitals and virtual orbitals for better expressivity, an even-tempered Gaussian basis set for flexible control over accuracy, and an equivariant neural network for efficiency. The results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms state-of-the-art techniques by a significant margin in terms of both accuracy and speed. The flexible efficiency-accuracy trade-off is a particularly valuable contribution. The ability to adjust the model’s size and parameters enables users to tailor the approach to their specific needs and computational resources. This highlights the practical applicability of the developed approach for diverse applications in the field of materials science and beyond.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more sophisticated methods for placing virtual orbitals, potentially leveraging graph neural networks or other machine learning techniques to optimize their positions and improve accuracy. Investigating alternative basis sets beyond Gaussian-type orbitals, such as Slater-type orbitals or wavelets, might enhance expressivity and reduce computational costs. Addressing the scalability limitations of current methods for very large molecules or complex materials is crucial, which could involve developing more efficient equivariant neural network architectures or hierarchical modeling strategies. Furthermore, extending the approach to predict other electronic properties directly from the learned charge density, such as energy, forces, or excited-state properties, would significantly broaden its applicability. Finally, a thorough investigation of the robustness and generalizability of the method across diverse chemical systems and material classes is needed to establish its reliability and potential impact on scientific discovery.

More visual insights#

More on figures

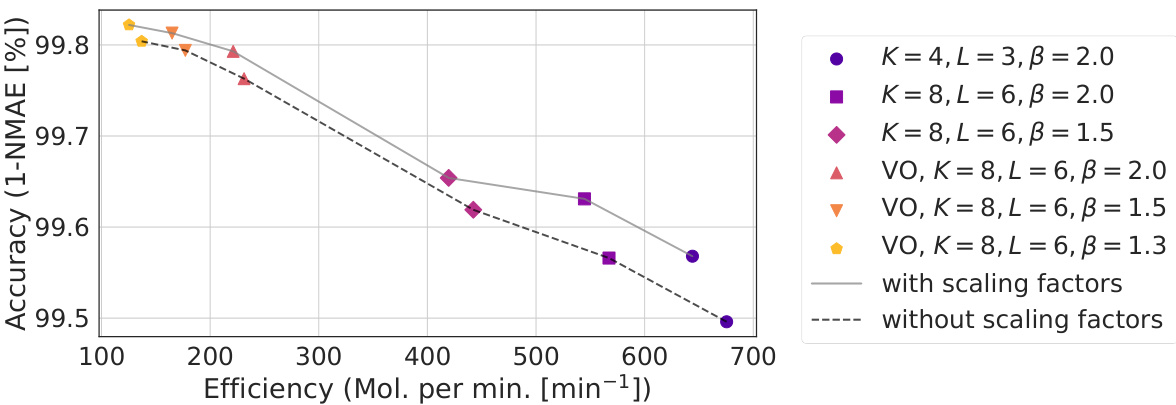

This figure shows the Pareto front of the SCDP models, which are obtained by fine-tuning the scaling factors. The Pareto front represents the set of models that offer the best trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. The x-axis represents the efficiency (measured in molecules processed per minute), and the y-axis shows the accuracy (1-NMAE). Each point on the graph represents a different model configuration, with different hyperparameters affecting the model’s complexity and training performance. The models with scaling factor fine-tuning achieve the best balance between efficiency and accuracy and dominate the others in the Pareto sense.

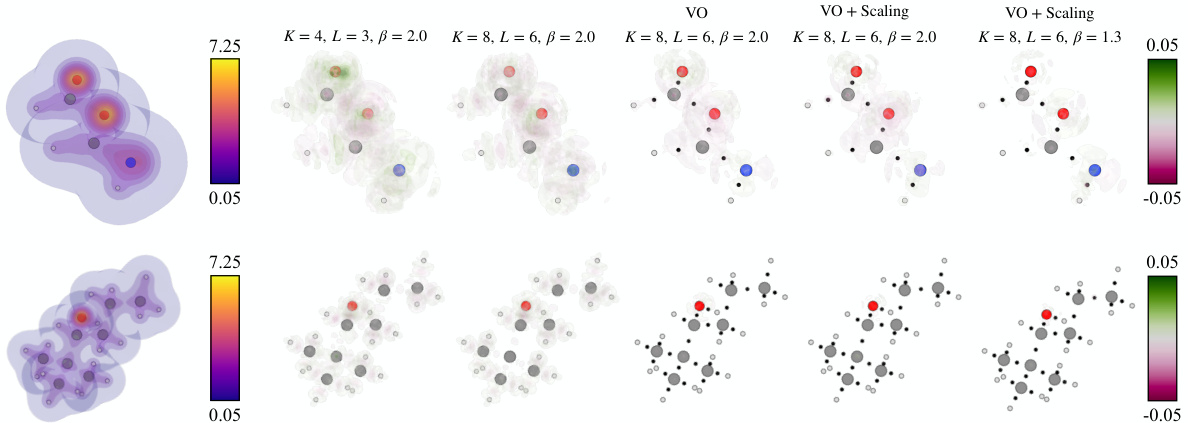

This figure visualizes the reference charge density and prediction errors for several SCDP models on two example molecules. It shows how prediction error decreases as the model complexity increases (larger model size, addition of virtual orbitals, inclusion of scaling factors). The impact of virtual orbitals on reducing errors near chemical bonds is also highlighted.

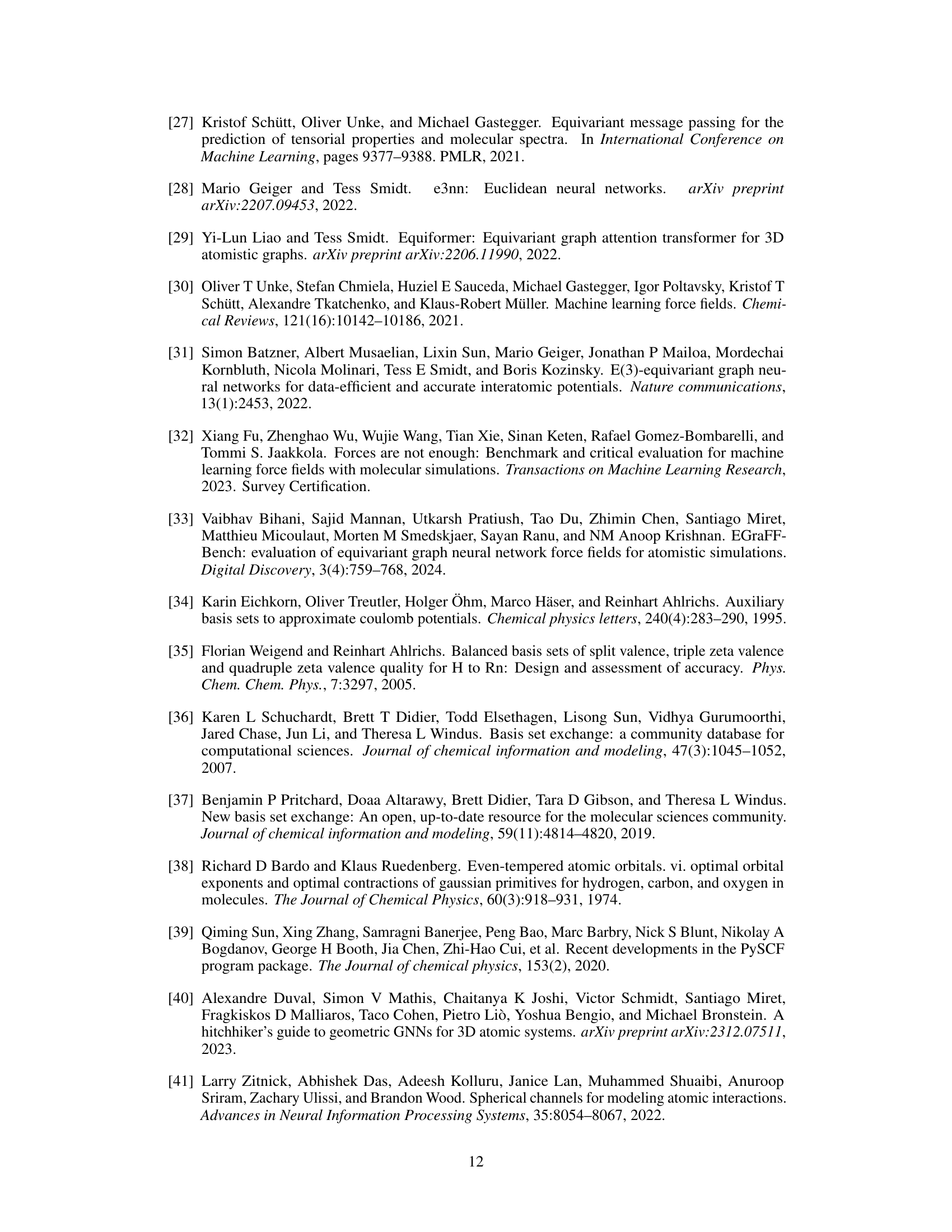

This figure shows two plots that illustrate the convergence of validation Normalized Mean Absolute Error (NMAE) during the training process of several Scalable Charge Density Prediction (SCDP) models. The left plot displays the NMAE during the pretraining phase, while the right plot shows the NMAE during the fine-tuning phase (after pretraining). Each plot shows curves for different model configurations, identified by the parameters K, L, and β, as well as an indication of whether virtual orbitals (VO) are used. The x-axis represents the training step, and the y-axis represents the validation NMAE. The figure demonstrates how model complexity and the inclusion of virtual orbitals affect training convergence and final accuracy.

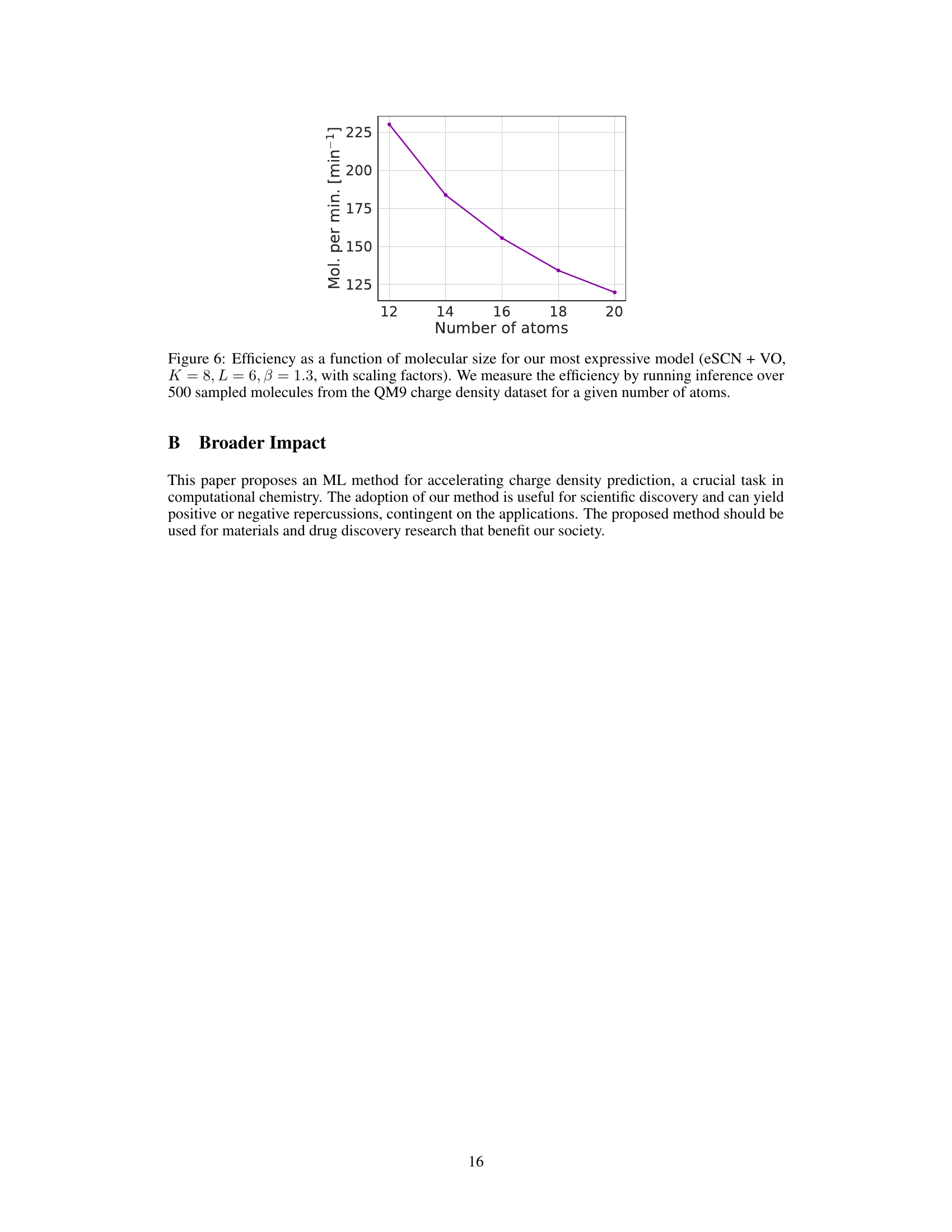

This figure shows the efficiency of the most performant model in molecules with varying sizes. The efficiency is measured as the number of molecules processed per minute and is plotted against the number of atoms in each molecule. The data comes from inference on 500 molecules sampled from the QM9 dataset.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of different models for charge density prediction on the QM9 dataset. It shows the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE), the NMAE on a specific split of the dataset, and the efficiency of each model in terms of molecules processed per minute. The table includes both baseline models from previous work and the proposed SCDP models with various configurations. The SCDP models show significantly better accuracy and efficiency compared to the baselines. The table helps to understand the tradeoffs between accuracy, expressiveness, and efficiency of different modeling choices.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different charge density prediction methods on the QM9 dataset. It shows the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE), a split NMAE, and the efficiency (molecules per minute) for various models, including the proposed SCDP models with different configurations (number of layers, tensor order, and basis set size), and several state-of-the-art baseline models. The table highlights the superior accuracy and efficiency of the proposed method.

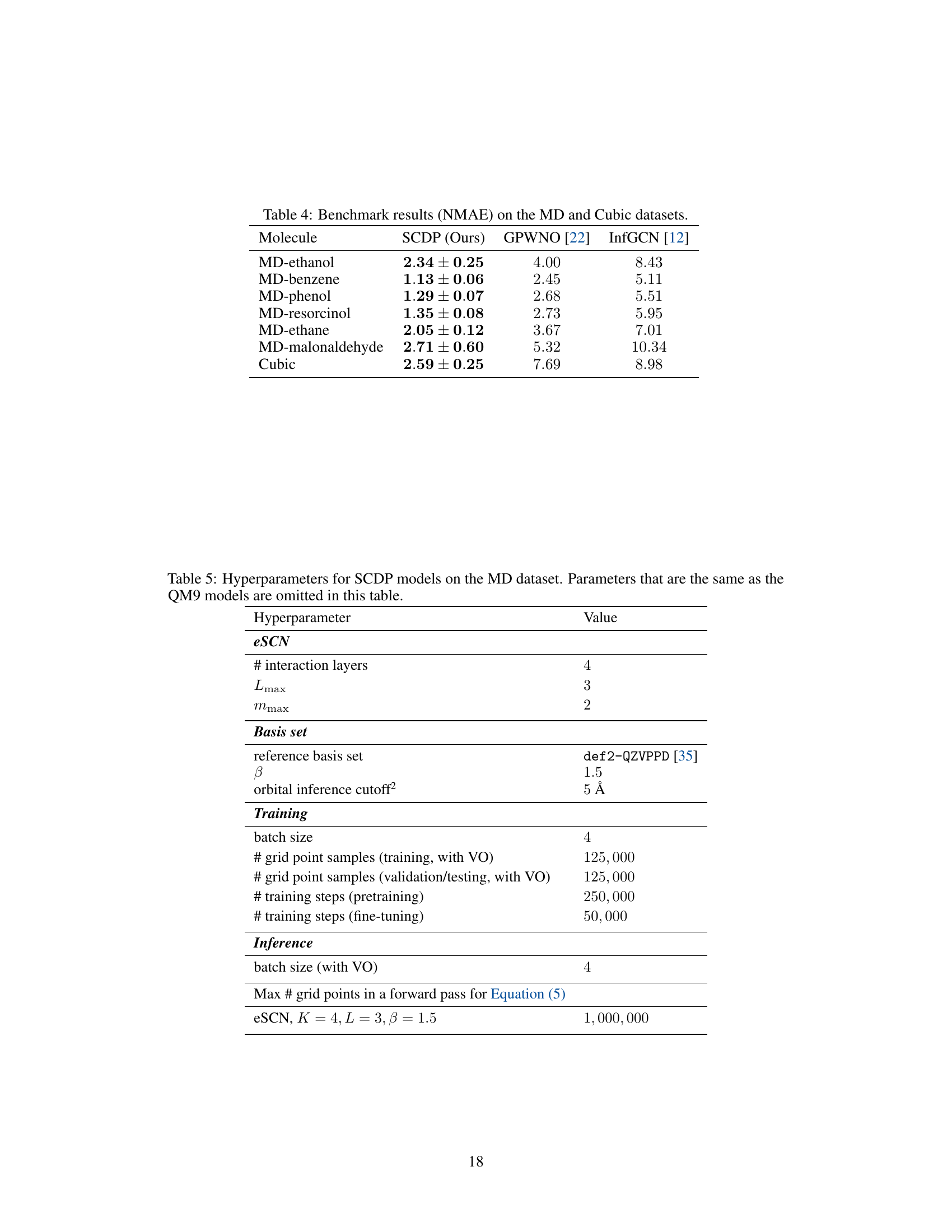

This table presents the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE) for charge density prediction on the MD and Cubic datasets. The SCDP model proposed in the paper is compared against two other methods: GPWNO and InfGCN. The results show the SCDP model achieves significantly lower NMAs than the other methods across a variety of molecules.

This table presents the results of QM9 charge density prediction using various models, including the proposed SCDP models and several baselines. It compares the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE), a measure of prediction accuracy, and the efficiency (molecules per minute) of each model. The table also highlights the impact of different model configurations (e.g., number of layers, tensor order, basis set size, use of virtual orbitals) on both accuracy and efficiency.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different charge density prediction methods on the QM9 dataset. It shows normalized mean absolute error (NMAE), a split NMAE (for a more robust evaluation), and the efficiency (molecules per minute) for various models. Different versions of the proposed Scalable Charge Density Prediction (SCDP) model are compared against existing state-of-the-art methods. The table highlights the impact of key design choices in the SCDP model (number of layers, feature representation, basis set expressiveness, and use of virtual orbitals).

This table compares the performance of the proposed SCDP models against existing state-of-the-art methods on the QM9 charge density prediction benchmark. It shows the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE), a split NMAE, and the efficiency (molecules processed per minute) for various models, including different configurations of the SCDP models (with varying numbers of layers, tensor order, and basis set parameters), models using virtual orbitals, and models with and without scaling factor fine-tuning. Baseline models’ performance is also included for comparison.

Full paper#