↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Symbolic regression (SR) aims to find concise programs explaining datasets, but faces challenges due to the vast search space. Existing SR methods, like genetic programming and deep learning, often struggle with scalability and interpretability. This paper introduces LASR, which leverages a large language model (LLM) to address these issues. It does this by inducing a library of abstract textual concepts to guide the search process.

LASR utilizes zero-shot queries to the LLM to identify and develop these concepts, enhancing standard evolutionary algorithms. This combined approach leads to a more efficient and interpretable search. Experiments on the Feynman equations and synthetic tasks show that LASR significantly surpasses existing SR algorithms. Furthermore, the paper demonstrates LASR’s ability to discover a novel scaling law for LLMs, showcasing its potential for broader applications in scientific discovery and LLM research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents LASR, a novel method for symbolic regression that significantly outperforms existing approaches. It introduces the concept of using large language models (LLMs) to guide the search process, leading to more efficient and interpretable results. This opens new avenues for scientific discovery and has implications for various fields, including automated scientific discovery and the development of improved LLMs. The novel LLM scaling law discovered is also of great interest.

Visual Insights#

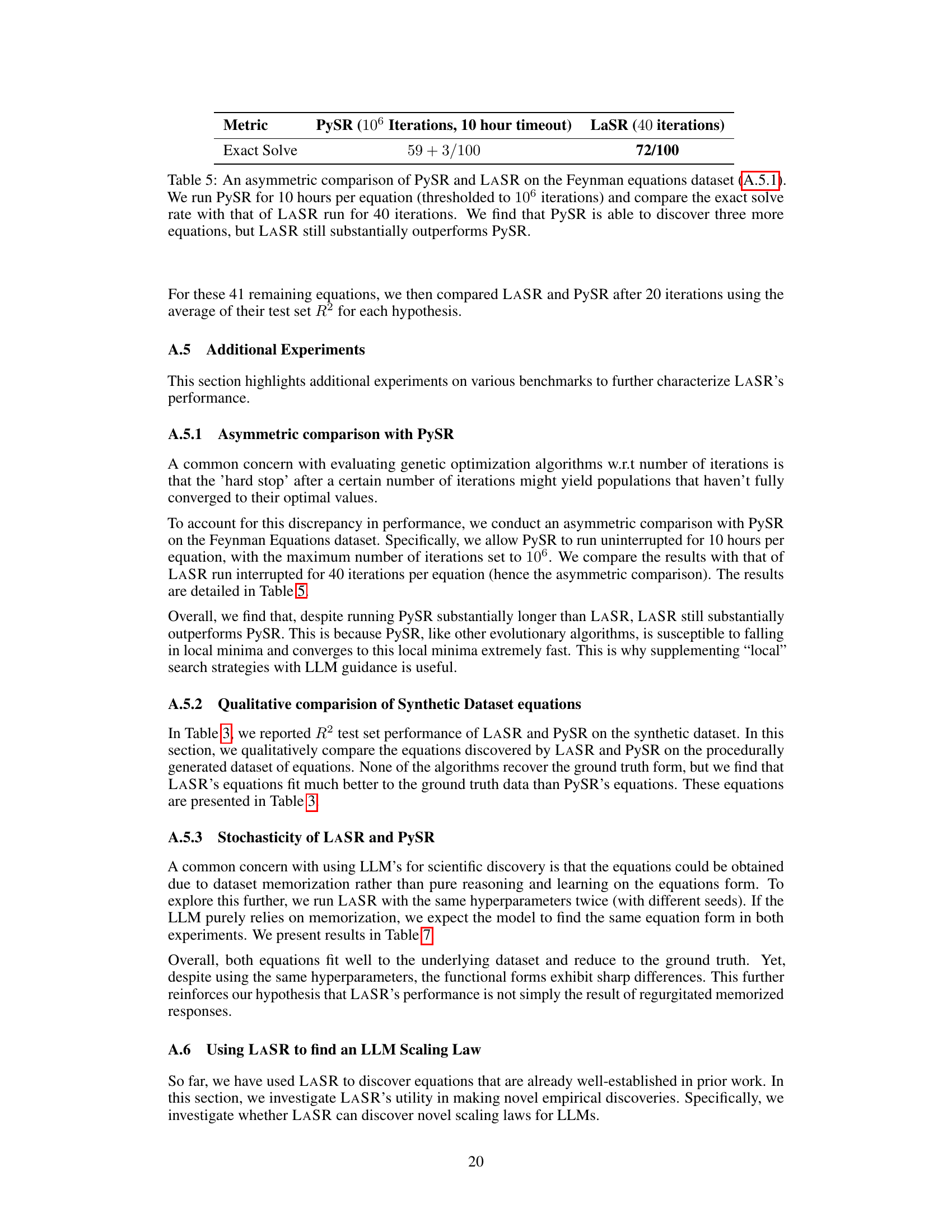

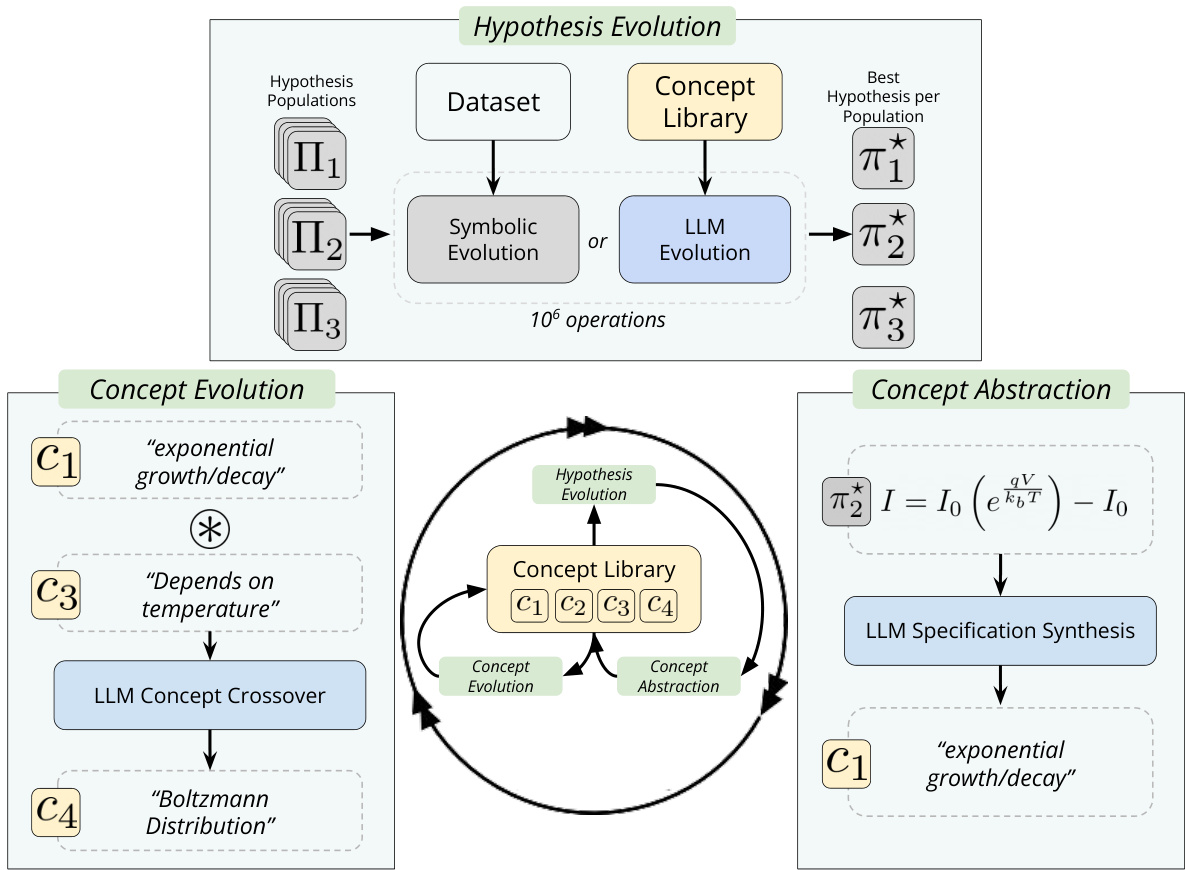

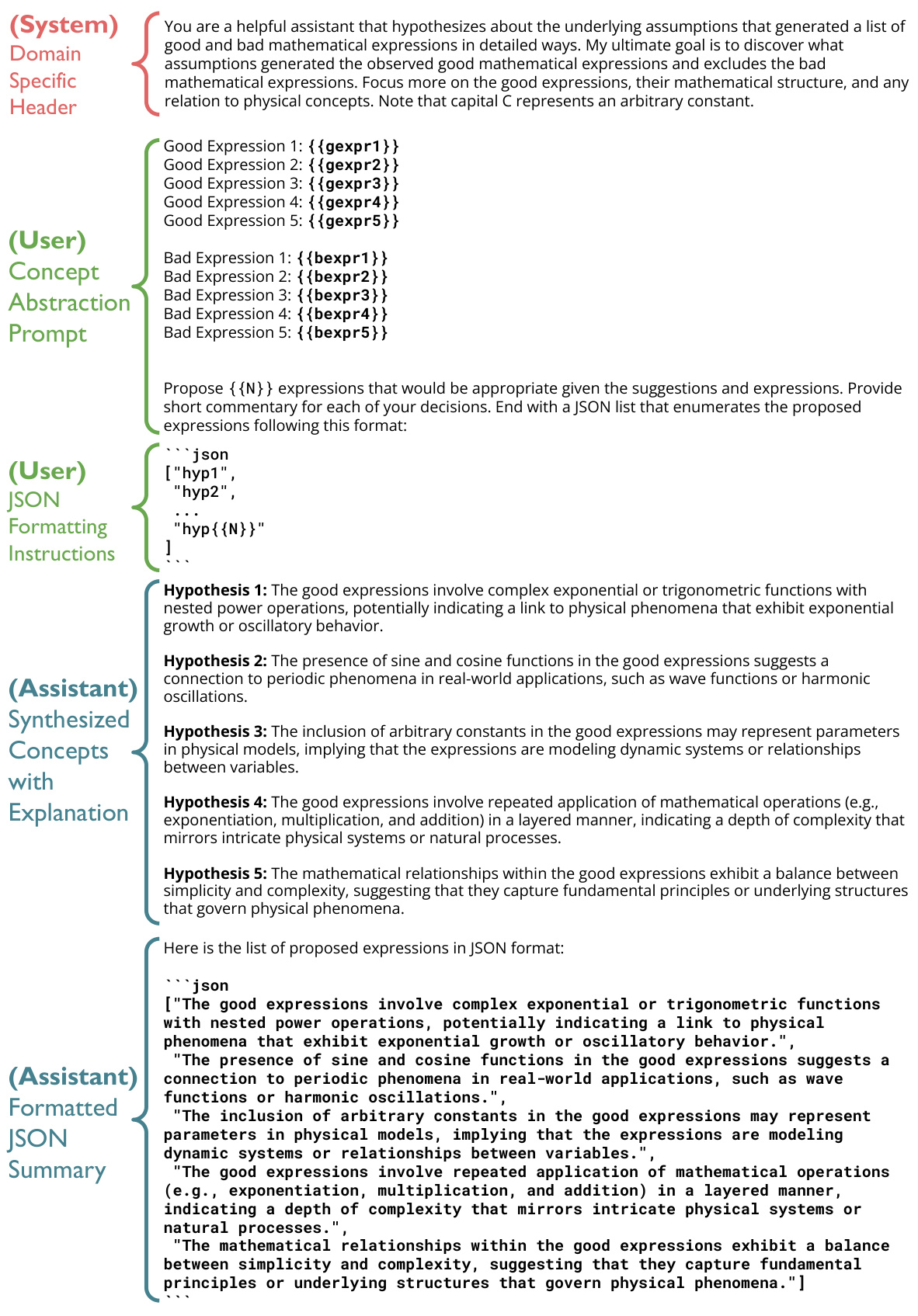

The figure illustrates the iterative process of LASR, a symbolic regression method. It highlights three main phases: hypothesis evolution (using a combination of standard evolutionary techniques and LLM-guided steps), concept evolution (abstraction of patterns from high-performing hypotheses using an LLM), and concept abstraction (refining and generalizing discovered concepts with the LLM). The interaction between these phases allows for a more directed and efficient search for optimal hypotheses.

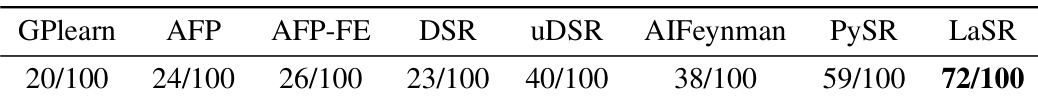

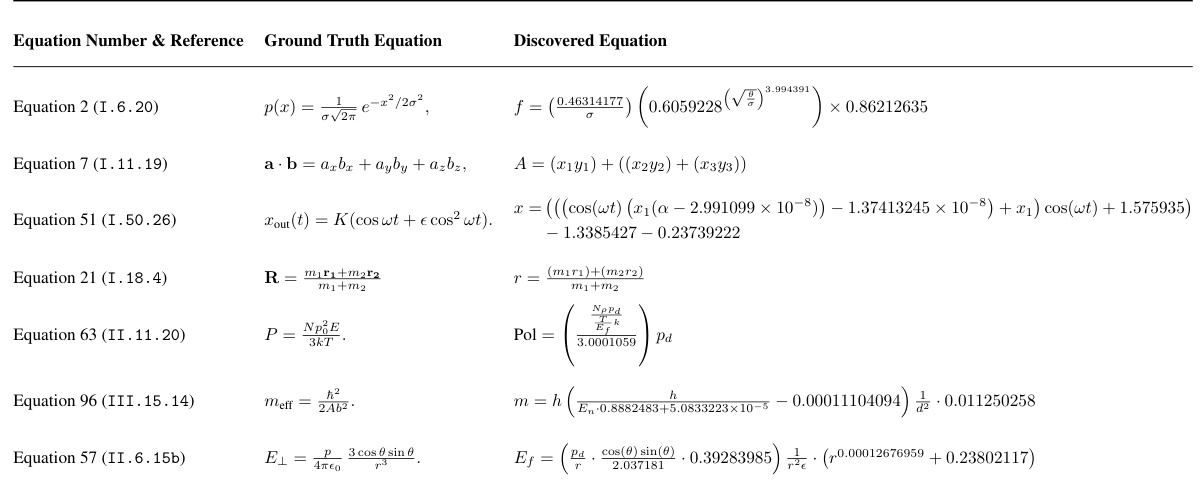

This table presents the results of various symbolic regression models on a benchmark dataset of 100 Feynman equations. The ’exact match solve rate’ indicates the percentage of equations each model correctly solved. The table highlights that LASR outperforms other state-of-the-art methods (GPlearn, AFP, AFP-FE, DSR, UDSR, AIFeynman, and PySR) by achieving the highest exact match solve rate. Notably, LASR uses the same hyperparameters as PySR, demonstrating its improvement is not simply due to hyperparameter tuning.

In-depth insights#

LLM-Augmented SR#

LLM-augmented symbolic regression (SR) represents a significant advancement in automated scientific discovery. By integrating large language models (LLMs), this approach overcomes limitations of traditional SR methods, which often struggle with the vast search space of possible equations. LLMs provide a powerful mechanism for incorporating domain knowledge and guiding the search process, moving beyond purely random exploration. This augmentation can lead to more efficient discovery of compact and accurate equations. The use of zero-shot queries allows LLMs to identify relevant concepts from natural language descriptions or existing hypotheses, biasing the search toward more promising areas. This targeted approach drastically reduces computation time and improves the overall effectiveness of the SR algorithm, enhancing its applicability to complex scientific problems. However, challenges remain, such as potential biases within the LLM’s training data or reliance on the LLM’s ability to correctly interpret scientific concepts. Careful consideration of these limitations is crucial for ensuring the reliability and trustworthiness of LLM-augmented SR results. Future research should focus on refining the integration techniques to mitigate these issues, further enhancing the method’s potential in various scientific disciplines.

Concept Evolution#

The concept evolution phase in LASR is crucial for its iterative refinement of the concept library. It leverages an LLM to evolve previously discovered concepts, making them more succinct and general. This isn’t simply a random mutation; rather, the LLM guides the process, drawing on its vast knowledge base to suggest improvements and generalizations. This ensures that the concepts become increasingly useful in guiding the hypothesis evolution phase. The open-ended nature of this process is a key strength, allowing LASR to continuously adapt and improve its understanding of the target phenomena. The ability to synthesize multiple concepts into new ones reflects the way human scientists combine existing knowledge to form novel insights. This iterative refinement is vital to LASR’s ability to solve complex symbolic regression problems far exceeding the capabilities of traditional methods. The integration of LLMs facilitates a level of abstraction and generalization not easily achievable through purely algorithmic approaches, leading to significant performance gains. Finally, the process is carefully designed to avoid overfitting and ensure diverse concept exploration, preventing premature convergence on less effective representations.

Feynman Equation Tests#

The Feynman Equation tests section likely evaluates the model’s performance on a benchmark dataset of physics equations from Feynman’s lectures. Success is measured by how accurately the model can rediscover these equations from input-output data. A key aspect would be comparing the model’s success rate to other state-of-the-art symbolic regression algorithms, highlighting the model’s strengths and limitations. A detailed analysis of the results should reveal insights into the model’s ability to handle different equation complexities, including considerations of noise and data sparsity. The evaluation methodology, including metrics used (e.g., exact match, approximation error), should be rigorously described. The results will determine if the model excels at reconstructing known scientific principles or if it struggles with more complex or nuanced equations. Further analysis of the ‘Feynman Equation Tests’ section will offer important evidence on the model’s capabilities and limitations for scientific discovery.

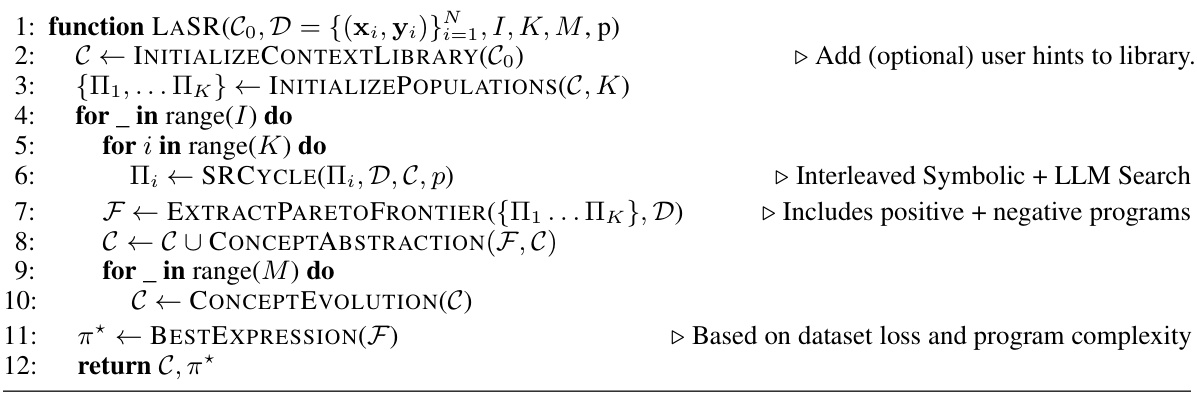

Ablation Experiments#

Ablation experiments systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of the described research, this involved removing different aspects, such as concept evolution, concept library, or variable names, to evaluate their effects on performance. The results of such an experiment would highlight the impact of each component, revealing which ones are crucial for the model’s success and which are less significant. Key insights would stem from identifying the relative importance of different components and understanding how they interact. For example, if removing the concept library significantly degrades performance, it indicates that the incorporation of knowledge-directed discovery is a crucial aspect of the model’s efficacy. This method provides a rigorous way to validate the design choices and evaluate their individual contributions to the overall success of the system. This is crucial for understanding the model’s internal workings and ultimately improving its efficiency and performance.

LLM Scaling Laws#

The study’s exploration of LLM scaling laws offers a novel approach, leveraging symbolic regression to discover rather than posit scaling relationships. This contrasts with traditional methods that begin with pre-defined equations and focus on parameter optimization. By using LASR, the researchers uncovered a new scaling law that relates model performance to training steps and the number of shots. The interpretability of LASR’s output is highlighted as a key advantage, enabling a qualitative understanding of the discovered relationship. The discovered law reveals an exponential relationship between the number of shots and performance, particularly for smaller models, with diminishing returns at higher training steps. Limitations such as potential overfitting and the influence of LLM biases are acknowledged. The results emphasize the potential of using symbolic regression with LLMs to empirically uncover hidden relationships in complex systems, advancing the understanding of LLM scaling behavior.

More visual insights#

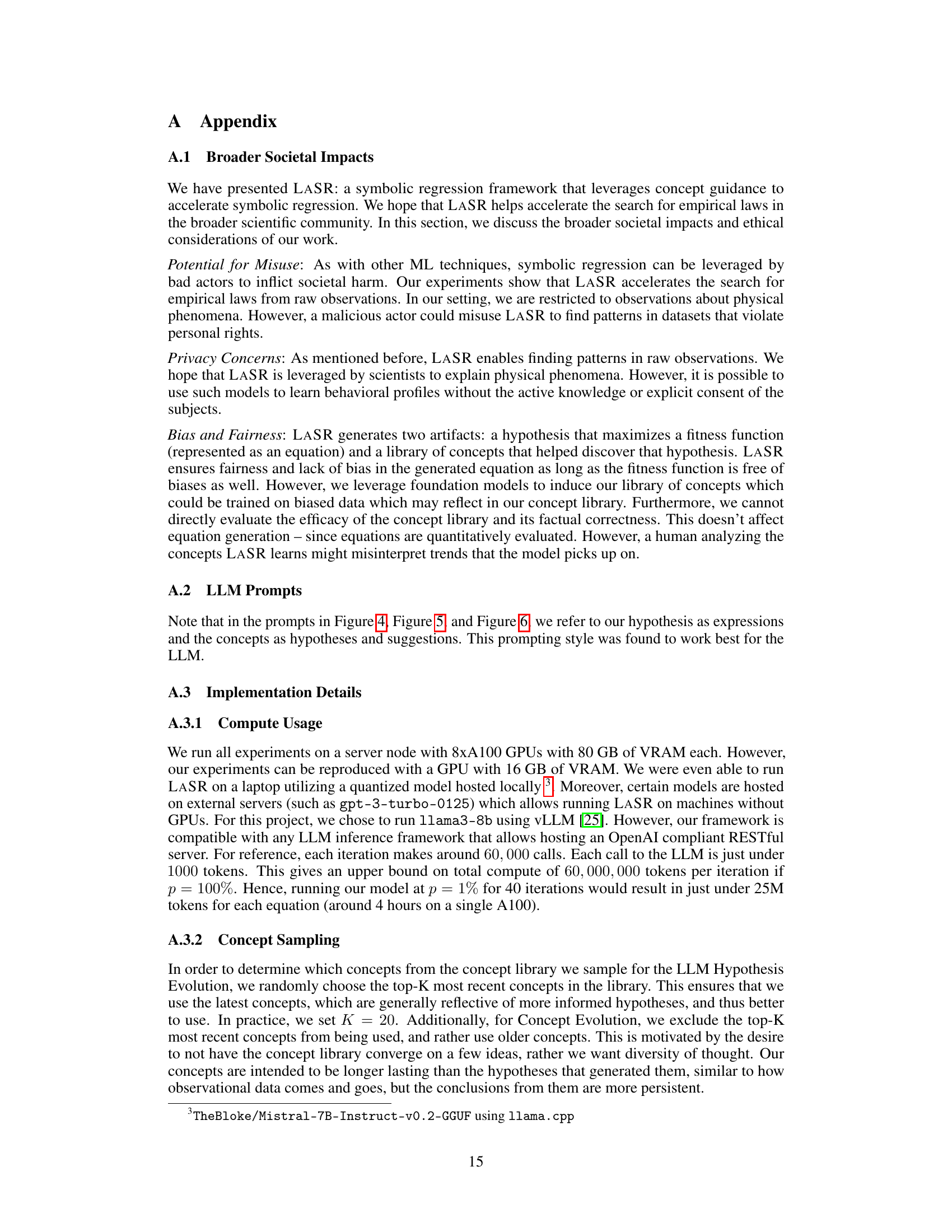

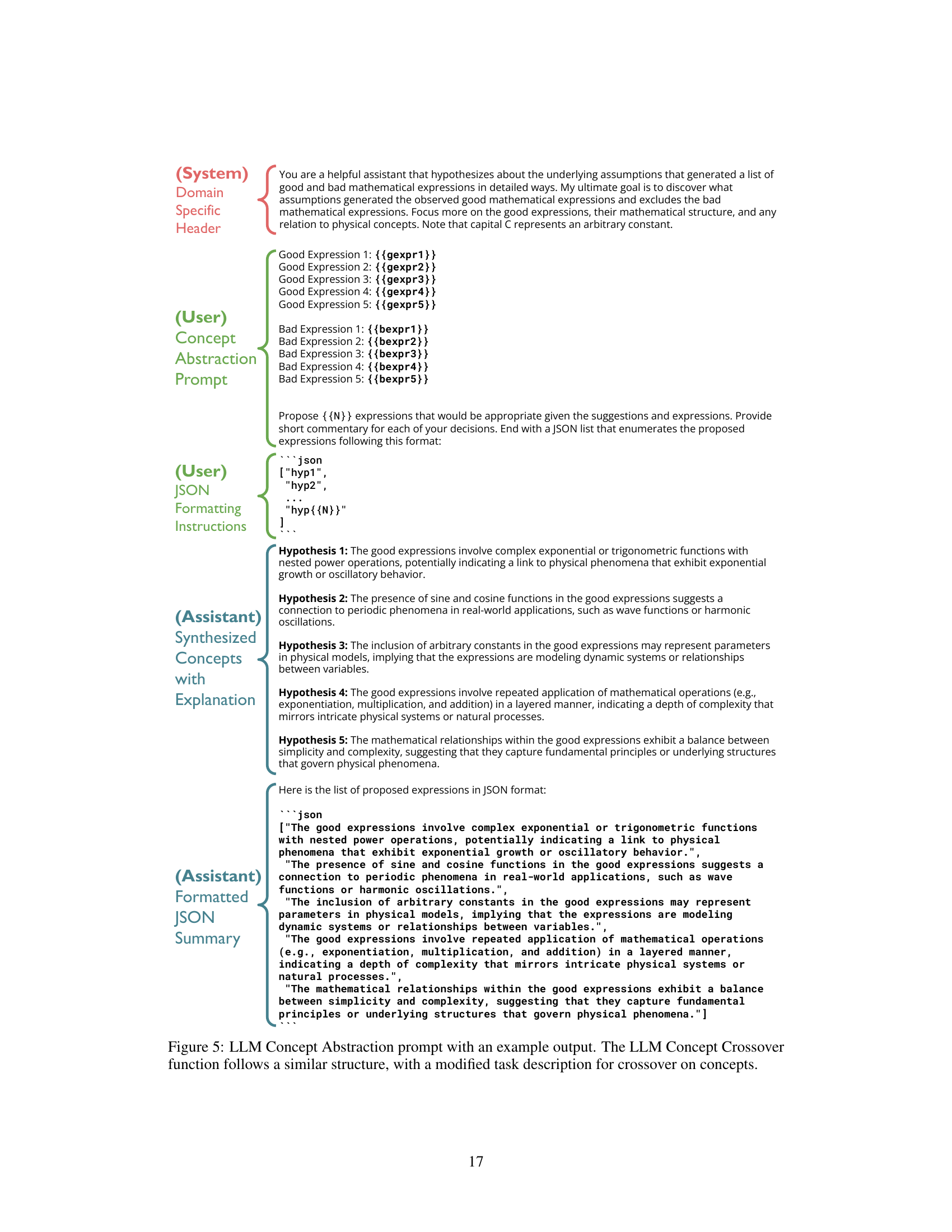

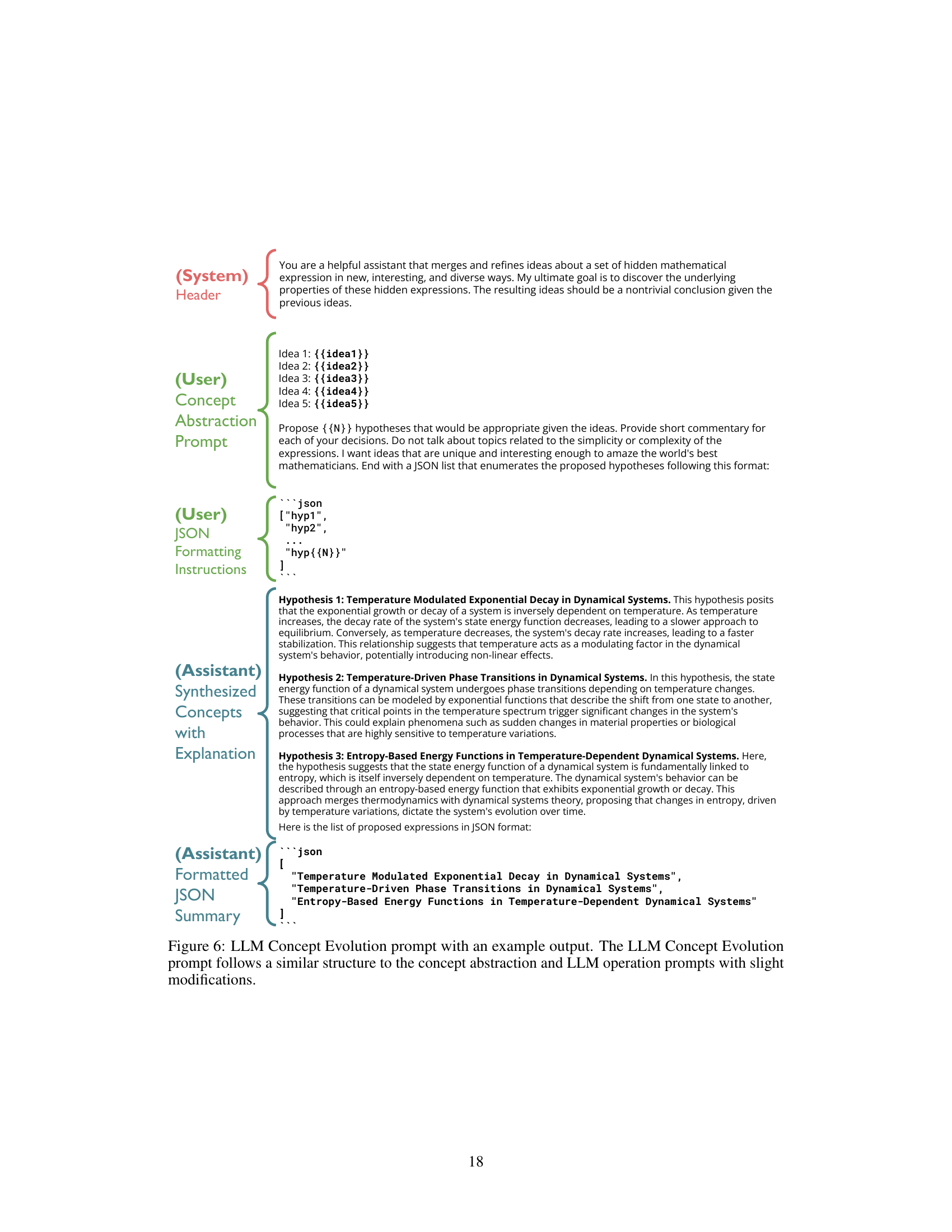

More on figures

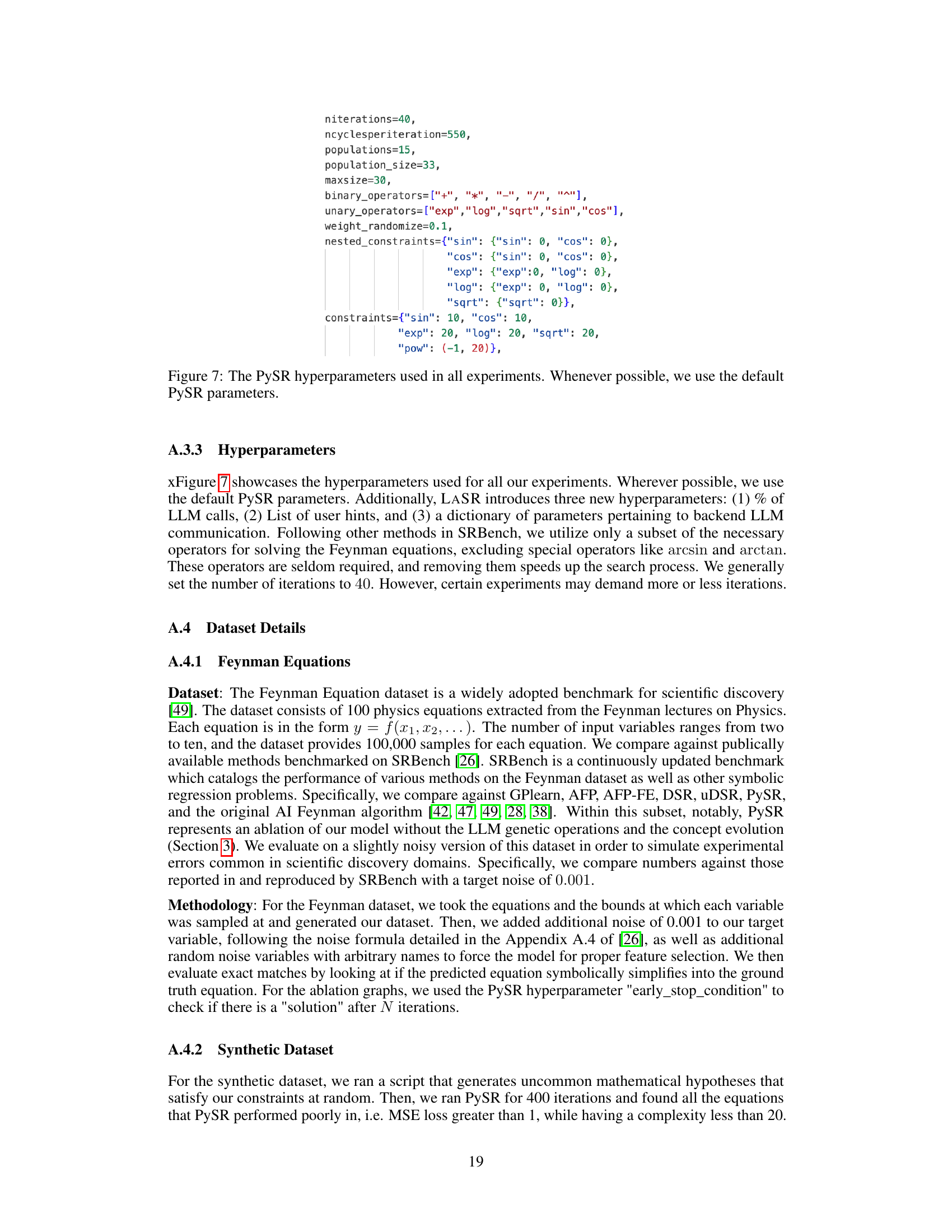

The figure illustrates a single step in the LASR algorithm, showing the iterative refinement of a library of interpretable textual concepts. These concepts guide the search for hypotheses by selectively replacing standard genetic operations with LLM-guided ones. The process involves three phases: hypothesis evolution using concept-directed operations; concept abstraction from top-performing hypotheses; and concept evolution to refine the concept library for future iterations. The figure highlights the interplay between symbolic regression and LLM-based operations, showcasing the synergistic approach of LASR.

This figure shows the ablation and extension studies performed on LASR using the Feynman dataset. The left panel shows the effect of removing different components of LASR (Concept Evolution, Concept Library, variable names) on the number of equations solved within a mean squared error (MSE) threshold over 40 iterations. It indicates that all components contribute to the performance. The right panel shows how providing initial concepts (hints) to LASR improves the number of equations solved, suggesting that incorporating prior knowledge accelerates the search process.

More on tables

This table presents the results of various symbolic regression algorithms on the Feynman equations dataset. The algorithms are compared based on their exact match solve rate, which represents the percentage of equations correctly solved. LASR outperforms all other algorithms in this benchmark.

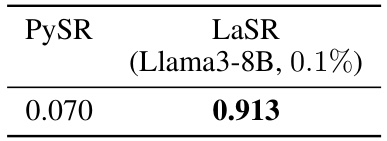

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of different LLMs (Llama3-8B and GPT-3.5) and varying the probability (p) of using the LLM for concept guidance on the performance of LASR in solving Feynman equations. The results are compared against the performance of PySR (without LLM guidance). The table shows the number of equations solved in four categories: Exact Solve, Almost Solve, Close, and Not Close, illustrating that LASR achieves better performance than PySR across different LLM and probability settings.

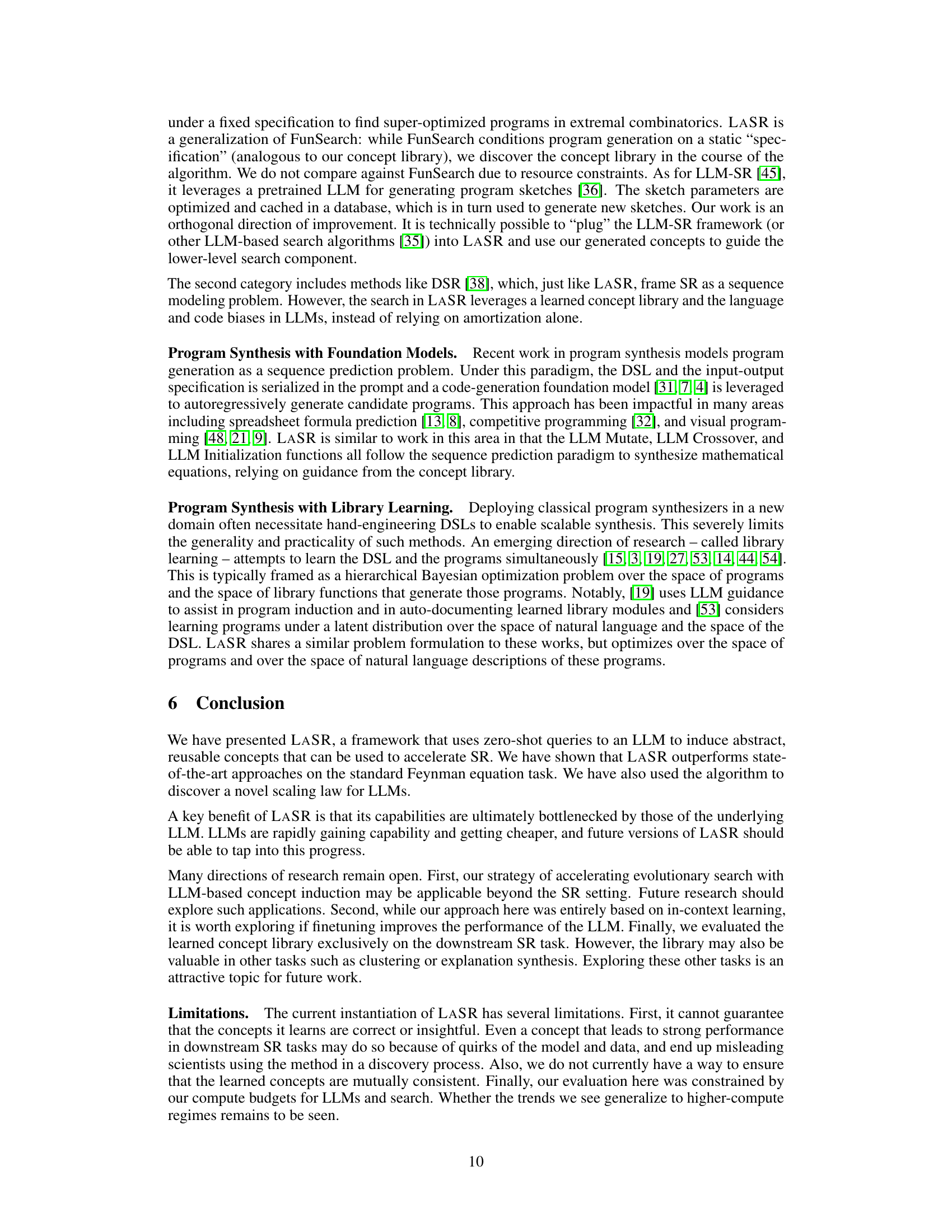

This table presents the results of a data leakage experiment designed to assess the fairness of using LLMs in symbolic regression. A synthetic dataset of 41 equations, engineered to be unlike those typically seen in the LLM’s training data, was created. The R² (R-squared) values, which measures the goodness of fit of a model, are compared for both PySR (a standard genetic programming algorithm) and LASR. The significantly higher R² for LASR suggests that LASR’s performance is not due to memorization of equations from the LLM’s training set, but rather that it can successfully leverage the LLM’s knowledge to aid in generating new equations.

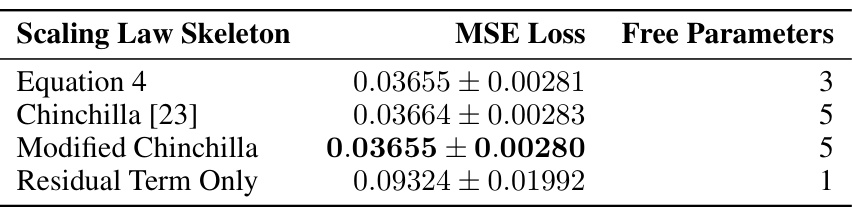

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss and the number of free parameters for four different LLM scaling law skeletons. The first row shows the results for the scaling law discovered by LASR, demonstrating comparable performance to the established Chinchilla equation but with fewer parameters. The table also includes results for the original Chinchilla equation and a modified version, along with a simple baseline of only using a residual term. This highlights LASR’s ability to discover competitive scaling laws efficiently.

This table presents the results of applying various symbolic regression methods to a dataset of 100 Feynman equations, including the proposed LASR method and several state-of-the-art baselines (GPlearn, AFP, AFP-FE, DSR, UDSR, AIFeynman, PySR). The metric used is the exact match solve rate, which represents the percentage of equations correctly solved by each method. LASR demonstrates the highest exact match solve rate, outperforming all other methods. Notably, it achieves this using the same hyperparameters as PySR, indicating its improved efficiency.

This table presents the results of applying various symbolic regression methods (GPlearn, AFP, AFP-FE, DSR, UDSR, AI Feynman, PySR, and LASR) to a dataset of 100 Feynman equations. The ’exact match solve rate’ metric is used, indicating the percentage of equations each algorithm correctly solved. LASR outperforms other methods, achieving the highest solve rate and matching PySR’s hyperparameters for a fair comparison.

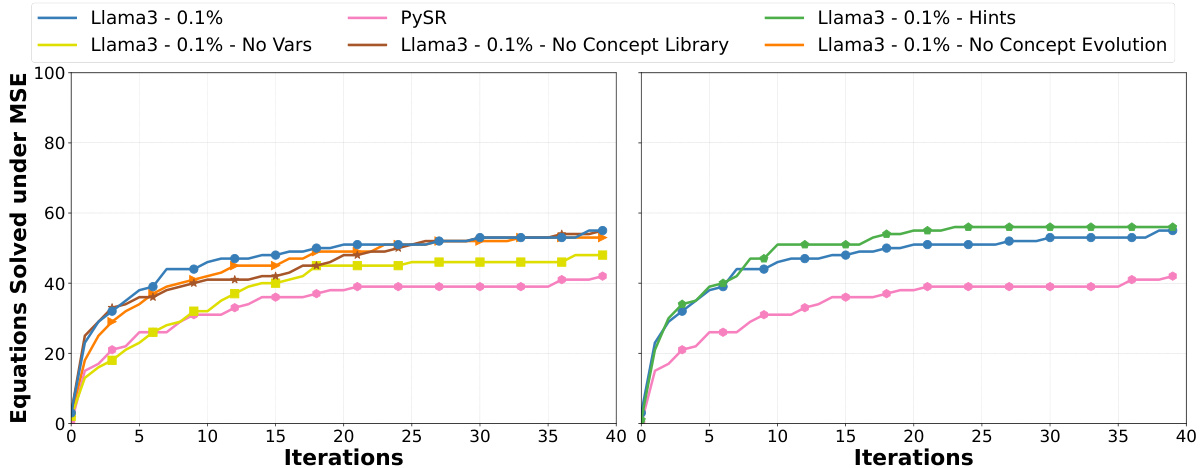

This table compares the performance of PySR and LASR on the Feynman Equations dataset using an asymmetric approach. PySR ran for 10 hours per equation (up to 106 iterations), while LASR ran for only 40 iterations. The metric used is the exact solve rate, measuring the percentage of equations correctly discovered. Despite the significantly longer runtime, LASR achieved a higher solve rate than PySR, demonstrating its efficiency.

This table presents a qualitative comparison of the ground truth equations and the equations predicted by LASR on a synthetic dataset. The dataset consists of equations with added noise to simulate real-world experimental error. The results show that while neither LASR nor other tested algorithms perfectly recovered the ground truth equations, they produced equations that captured some aspects of the ground truth. A quantitative comparison based on the R-squared metric is provided in Table 3.

This table presents the results of two separate runs of LASR on the same equation using identical hyperparameters but different random seeds. This experiment aims to verify that LASR’s success is not due to memorization of the equation. The results show that while both runs yield high-performing solutions, the resulting functional forms are quite different, supporting the claim that the model’s success is based on reasoning and not memorization.

This table showcases seven equations that LASR successfully discovered, comparing them to their ground truth counterparts from the Feynman Lectures. LASR’s discovered equations often require simplification to match the ground truth, highlighting the algorithm’s ability to find functional forms that closely approximate the target solutions. Note that minor discrepancies exist in variable names between the online lectures and the dataset used in this paper.

Full paper#