↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current gaze following research mainly focuses on target localization, which has limited practical value. Understanding the semantics of what someone is looking at is often more important than just knowing the location. Existing methods struggle with this semantic understanding because of limitations in data and model design. The paper addresses these issues by introducing a new, more comprehensive semantic gaze following task.

The proposed solution is a novel end-to-end architecture that uses a visual-language alignment approach to achieve both precise localization and accurate semantic classification of the gaze target. This method uses a transformer-based decoder to fuse image and gaze information, leading to improved performance. It also introduces new benchmarks and pseudo-annotation pipelines to support future research in this area. The results demonstrate state-of-the-art performance on a main benchmark, showcasing the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly advances the field of gaze target detection by introducing a novel task that considers the semantics of the gaze target. It provides a strong benchmark dataset and a robust model that achieves state-of-the-art results in both localization and recognition. The proposed approach is likely to influence future research, inspire new methodologies, and potentially pave the way for numerous applications. The generalizability of the visual-text alignment approach makes it easily adaptable to other vision-language tasks.

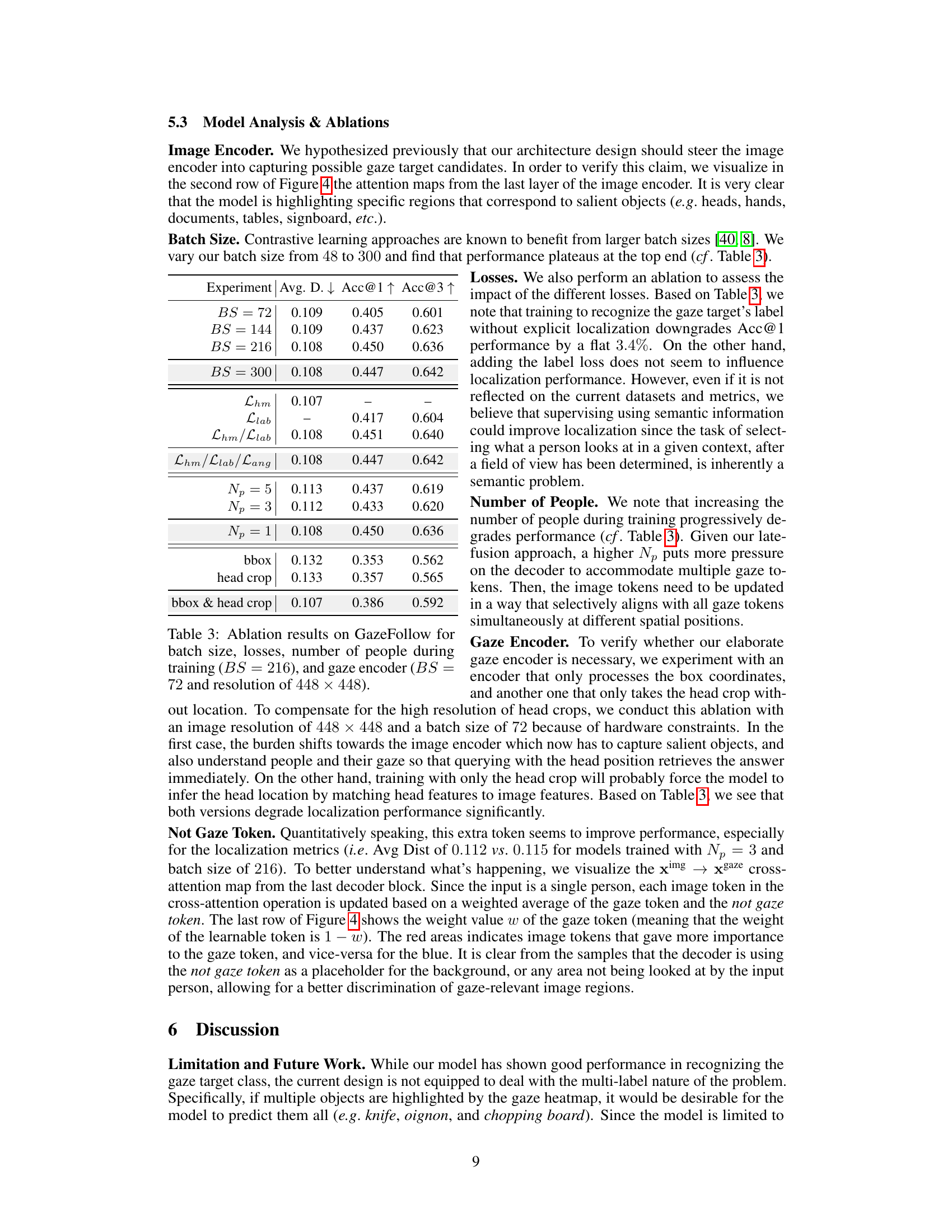

Visual Insights#

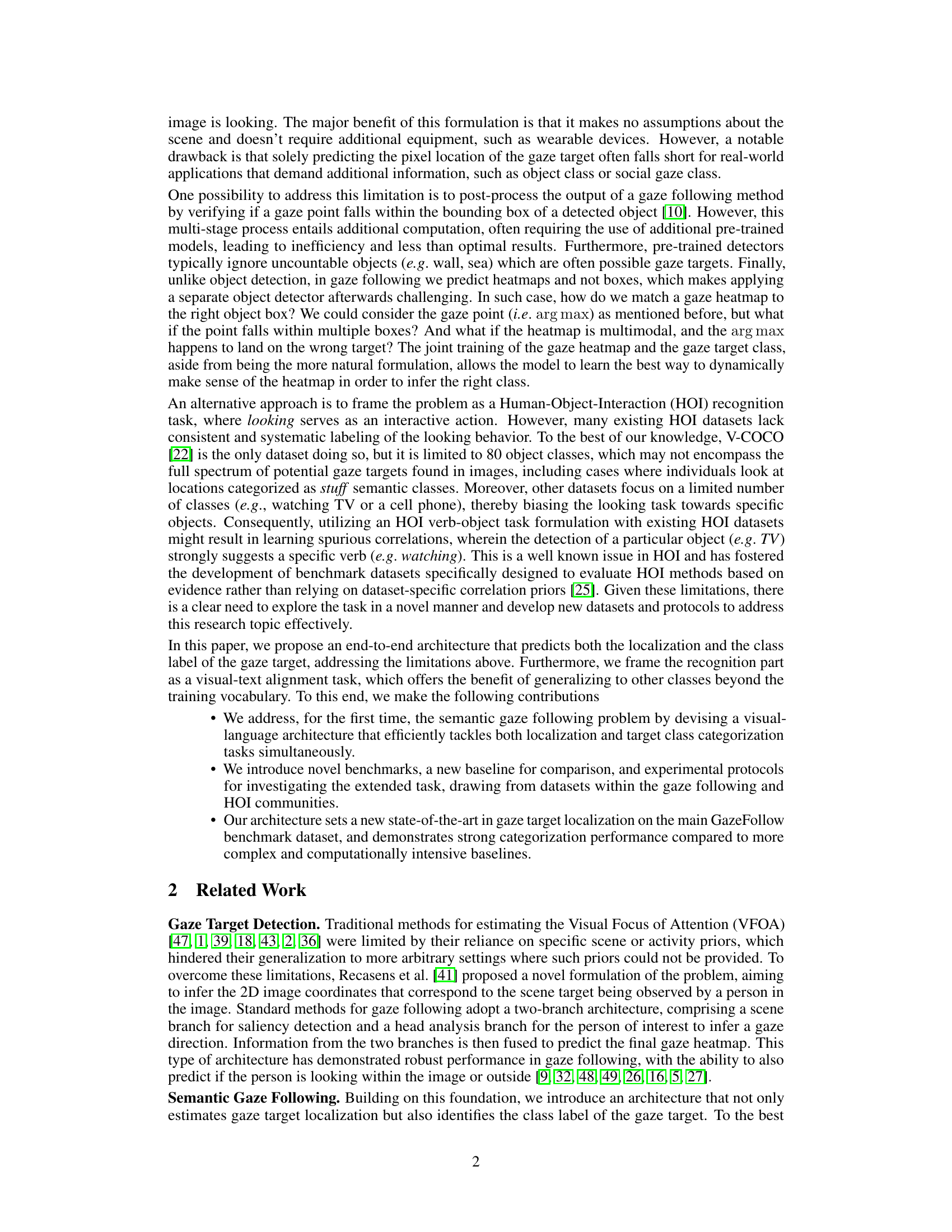

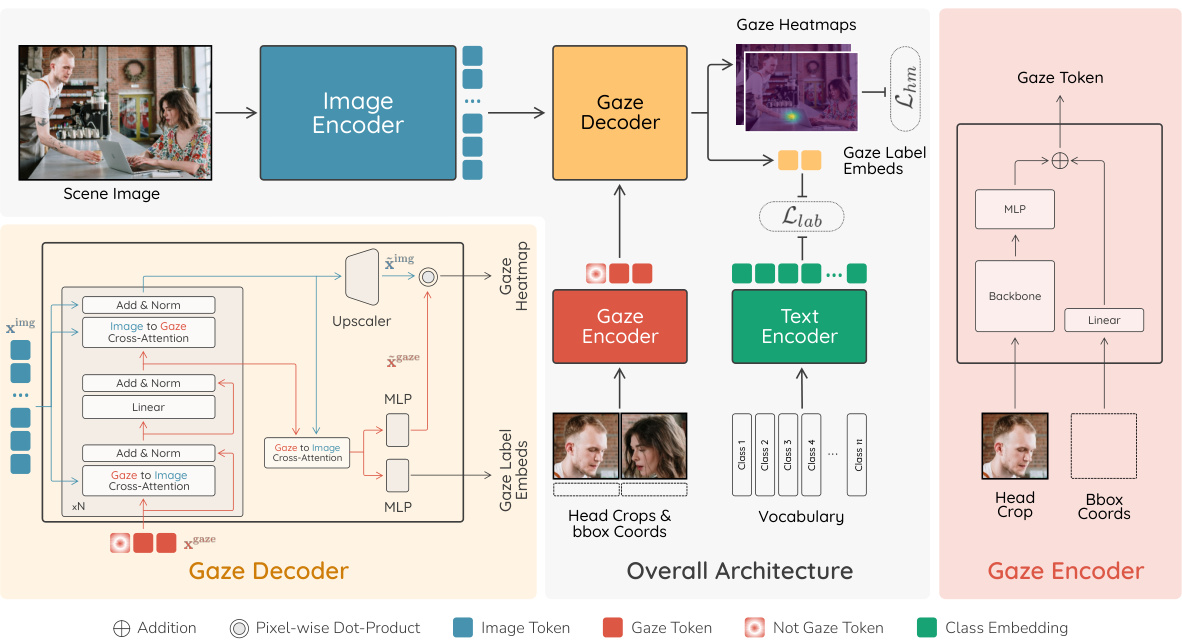

This figure shows the overall architecture of the proposed model for semantic gaze target detection. It consists of five main components: an Image Encoder that processes the scene image and produces image tokens, a Gaze Encoder that processes head crops and bounding box coordinates to generate gaze tokens, a Gaze Decoder that combines image and gaze tokens to predict gaze heatmaps and gaze label embeddings, a Text Encoder that computes class embeddings from a predefined vocabulary, and a final similarity computation step that matches predicted gaze label embeddings to vocabulary embeddings to determine the semantic class of the gaze target.

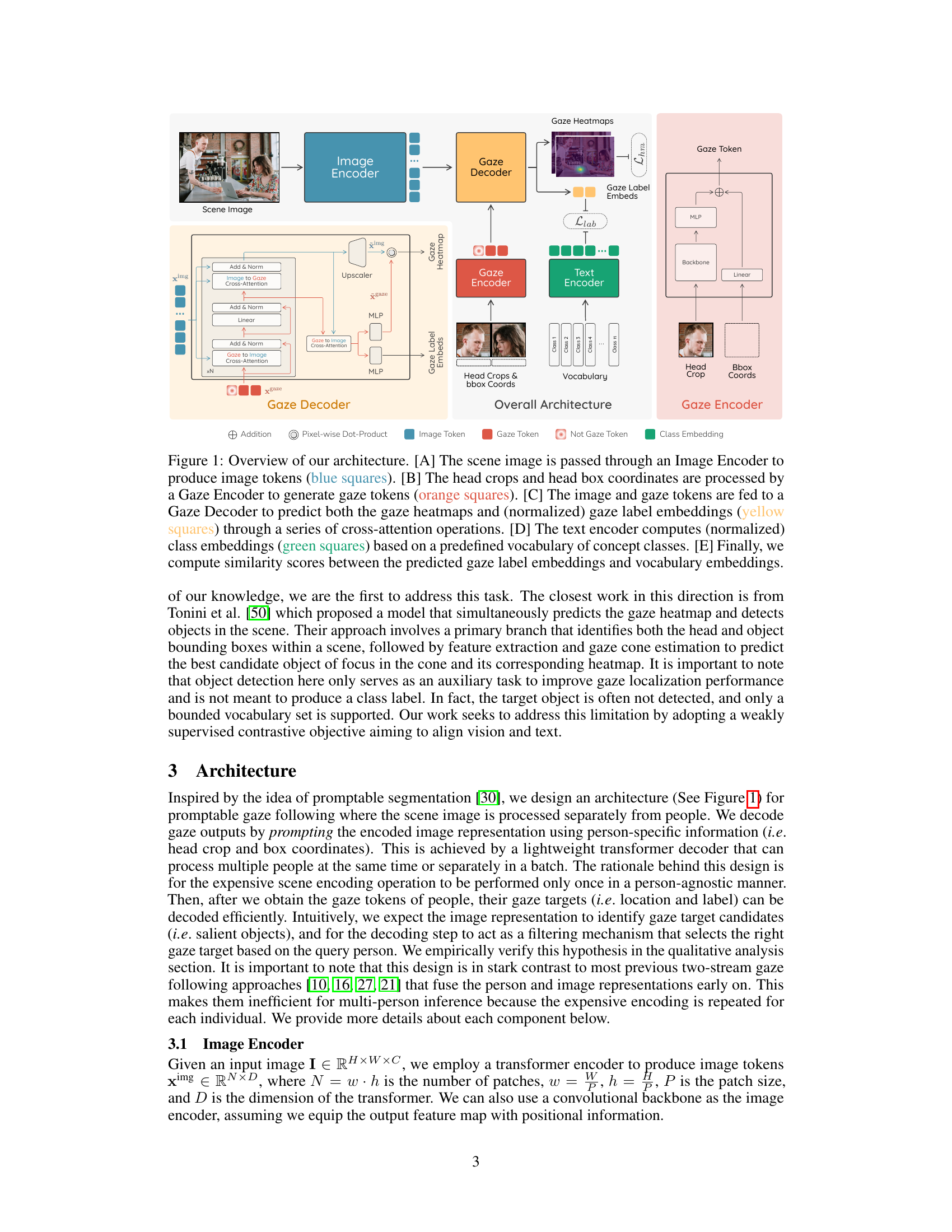

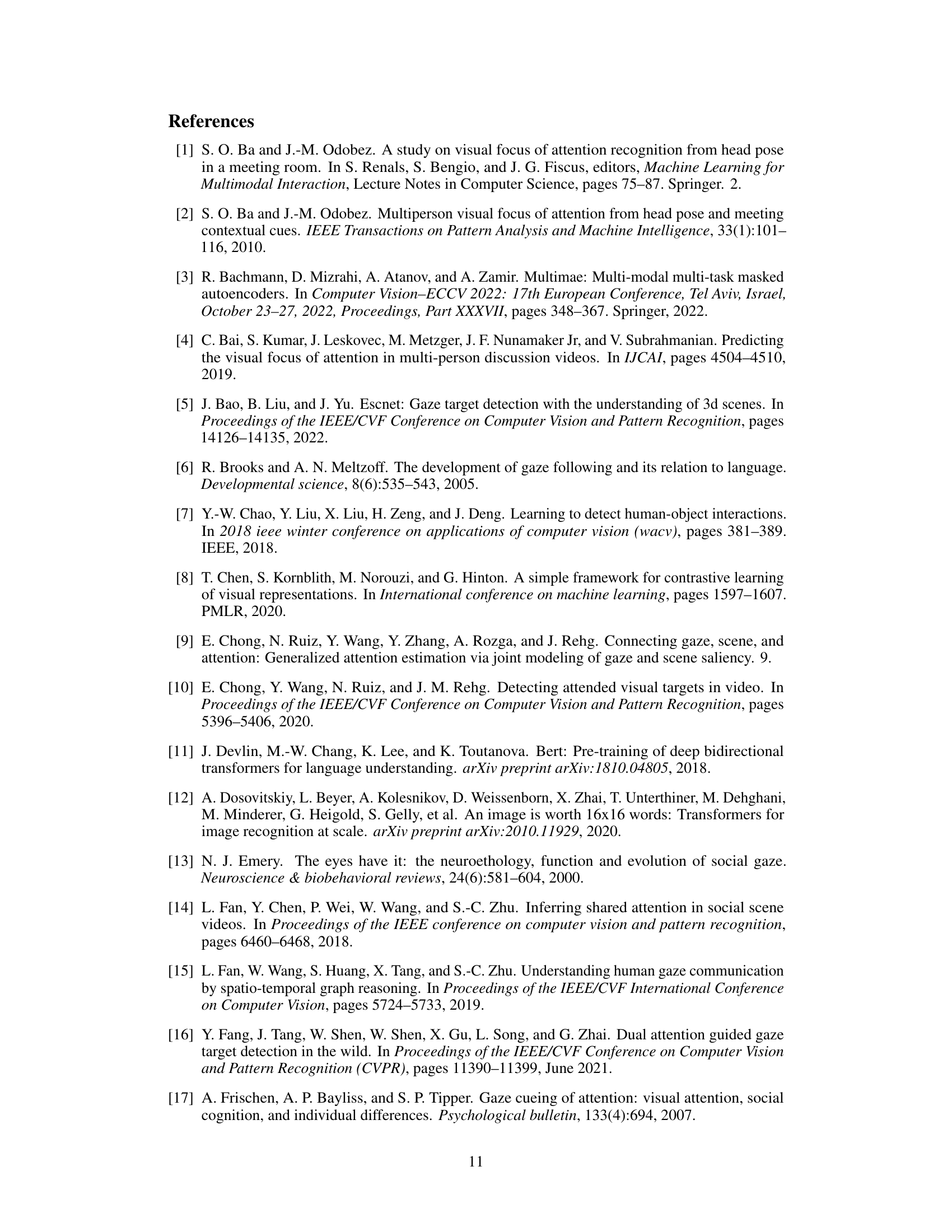

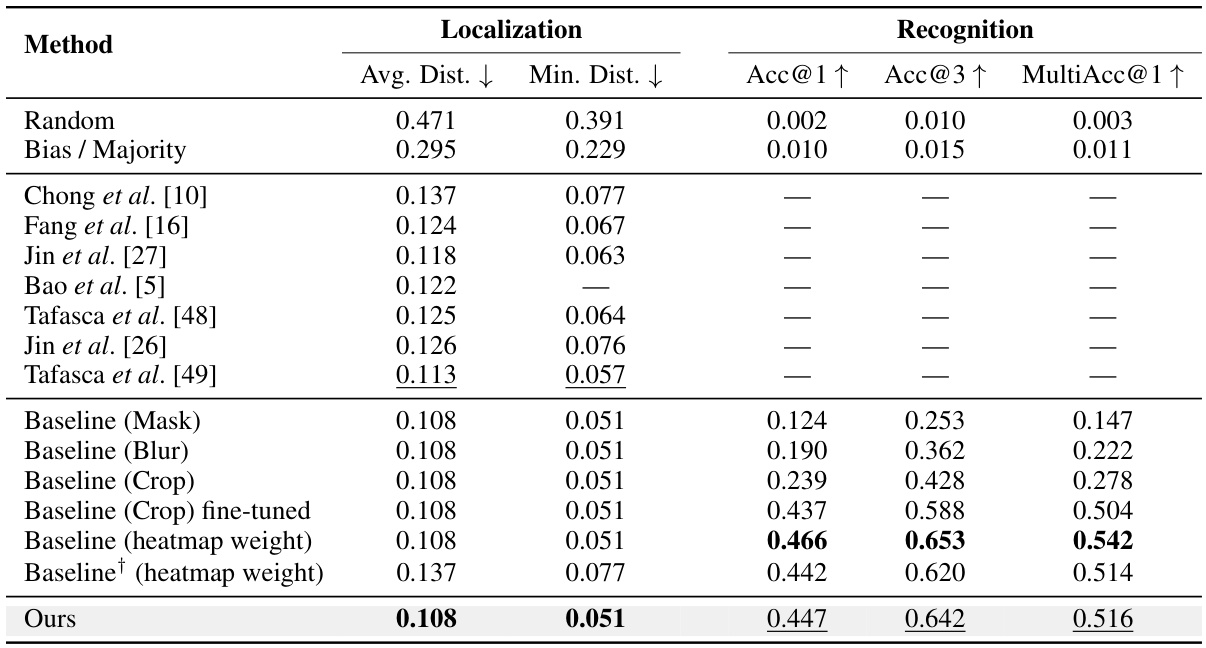

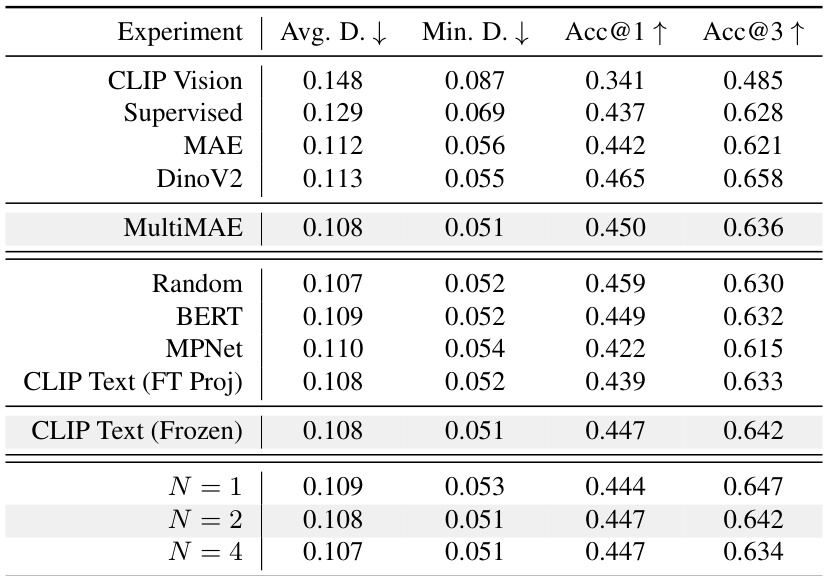

This table presents a comparison of different methods for gaze target localization and recognition on the GazeFollow dataset. The methods include various baselines (using different conditioning techniques on the predicted gaze heatmap) and the proposed method from the paper. The metrics used are Average Distance (Avg. Dist.), Minimum Distance (Min. Dist.), Accuracy@1 (Acc@1), Accuracy@3 (Acc@3), and MultiAccuracy@1 (MultiAcc@1). Lower Avg. Dist. and Min. Dist. values indicate better localization, while higher Accuracy values show better recognition performance. The best performing method for each metric is highlighted in bold, with the second-best underlined. The baseline models use the proposed gaze heatmap prediction model (except for the baseline which uses a model from Chong et al. [10]).

In-depth insights#

Semantic Gaze Detect#

Semantic gaze detection is a significant advancement in computer vision, moving beyond simple gaze localization to understand the meaning of where someone is looking. This involves not just identifying pixel coordinates but also classifying the object or scene element that is the focus of attention. The challenge lies in the complexity of integrating visual and semantic information. Existing methods often struggle with this, relying on separate steps or making restrictive assumptions about scene understanding. A unified model that seamlessly predicts both gaze target location and its semantic label is highly desirable for applications requiring a deeper understanding of human attention, such as human-computer interaction, robotics, or social cognition research. Key challenges include data acquisition, model architecture, and evaluation metrics. Annotated datasets are essential for training accurate models, and creative approaches may be needed to overcome the difficulty of producing such ground truth data. Finally, robust benchmarks are needed to fairly compare different approaches and to drive future research in this exciting and rapidly evolving field.

GazeFollow Dataset#

The GazeFollow dataset, while not explicitly detailed, plays a crucial role in this research. It’s presented as a foundational dataset for semantic gaze following, lacking inherent semantic labels for the gaze targets. This necessitates a pseudo-annotation pipeline, a significant methodological contribution in itself. The pipeline leverages open-source tools for open-vocabulary semantic segmentation, aiming to link gaze points with object class labels. This process introduces challenges related to accuracy and noise in the generated labels, demanding careful handling and potentially impacting downstream model performance. The dataset’s limitations highlight the need for more thoroughly annotated datasets to push the field forward. Its use as a benchmark for both localization and semantic classification underscores its importance for future research. Overall, the GazeFollow dataset serves as a critical starting point, but it emphasizes the ongoing need for more comprehensive resources in the field of semantic gaze understanding.

Visual-Text Alignment#

Visual-text alignment, in the context of this research paper, likely refers to a method for integrating visual and textual information. This is a crucial component of the paper’s approach for semantic gaze target detection. The core idea is to establish a correspondence between visual features extracted from images (e.g., object representations, gaze heatmaps) and textual representations of object classes or semantic labels. Successful alignment allows the model to learn relationships between visual patterns and their textual descriptions, which is essential for accurately classifying a gaze target. The model likely uses a multimodal architecture to achieve this, possibly involving attention mechanisms to weight the importance of visual features in relation to their textual counterparts. This approach addresses a key limitation of traditional gaze following: moving beyond simple gaze localization to understanding the semantics of what a person is looking at. By connecting visual features to semantic labels, the system produces richer and more informative outputs, making the gaze prediction more robust and interpretable. The success of visual-text alignment hinges on the quality and quantity of training data, the sophistication of the multimodal architecture, and the effectiveness of the alignment mechanism. The authors’ approach likely presents an innovative contribution to the field, demonstrating stronger performance on classification compared to traditional methods that only focus on localization.

Benchmarking HOI#

Benchmarking Human-Object Interaction (HOI) presents unique challenges due to the complexity of human-object relationships and the vast variability in visual scenarios. Creating a robust benchmark necessitates careful consideration of dataset diversity, encompassing a wide range of actions, object categories, and environmental contexts. Annotation quality is crucial, demanding precise and consistent labeling of interactions. Evaluation metrics must be carefully chosen to capture the nuances of HOI, potentially including metrics that go beyond simple accuracy and consider factors such as localization precision and contextual understanding. Furthermore, the benchmark should facilitate the development and comparison of different model architectures, offering standardized evaluation protocols and datasets to encourage reproducible research. A strong HOI benchmark is vital to propel progress in visual reasoning and understanding, serving as a catalyst for innovation in areas such as robotics, human-computer interaction, and video understanding. Addressing the limitations of existing benchmarks, such as limited object classes or insufficient contextual information, is key to building a truly comprehensive and useful evaluation framework that facilitates meaningful progress in the field.

Future Gaze Research#

Future gaze research holds significant promise. Improving the accuracy and robustness of gaze estimation across diverse conditions (lighting, head pose, ethnicity) is crucial for wider applicability. This includes developing methods that handle occlusions and complex scenes more effectively. Semantic gaze understanding, moving beyond simple 2D point prediction to understanding the object or concept being looked at, is a critical next step. This requires sophisticated integration with object recognition and scene understanding. Furthermore, addressing the privacy concerns inherent in gaze-tracking technology is essential for ethical and responsible development. This could involve anonymization techniques or designing systems that respect user privacy. Finally, exploring how gaze interacts with other modalities (speech, gestures, physiology) offers opportunities for richer understanding of human behavior and communication. The development of larger and more diverse datasets is needed to train and validate robust models that work across different demographics and contexts.

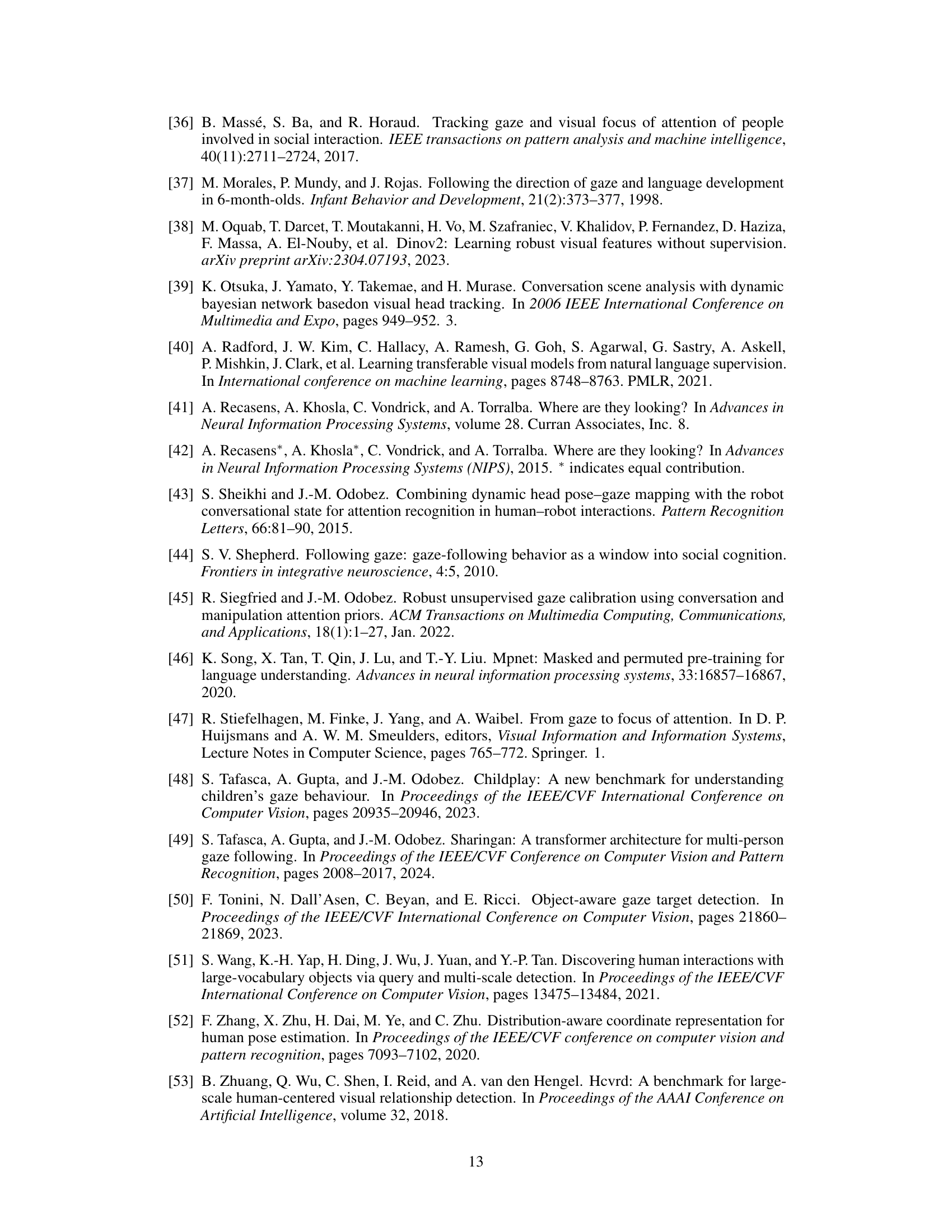

More visual insights#

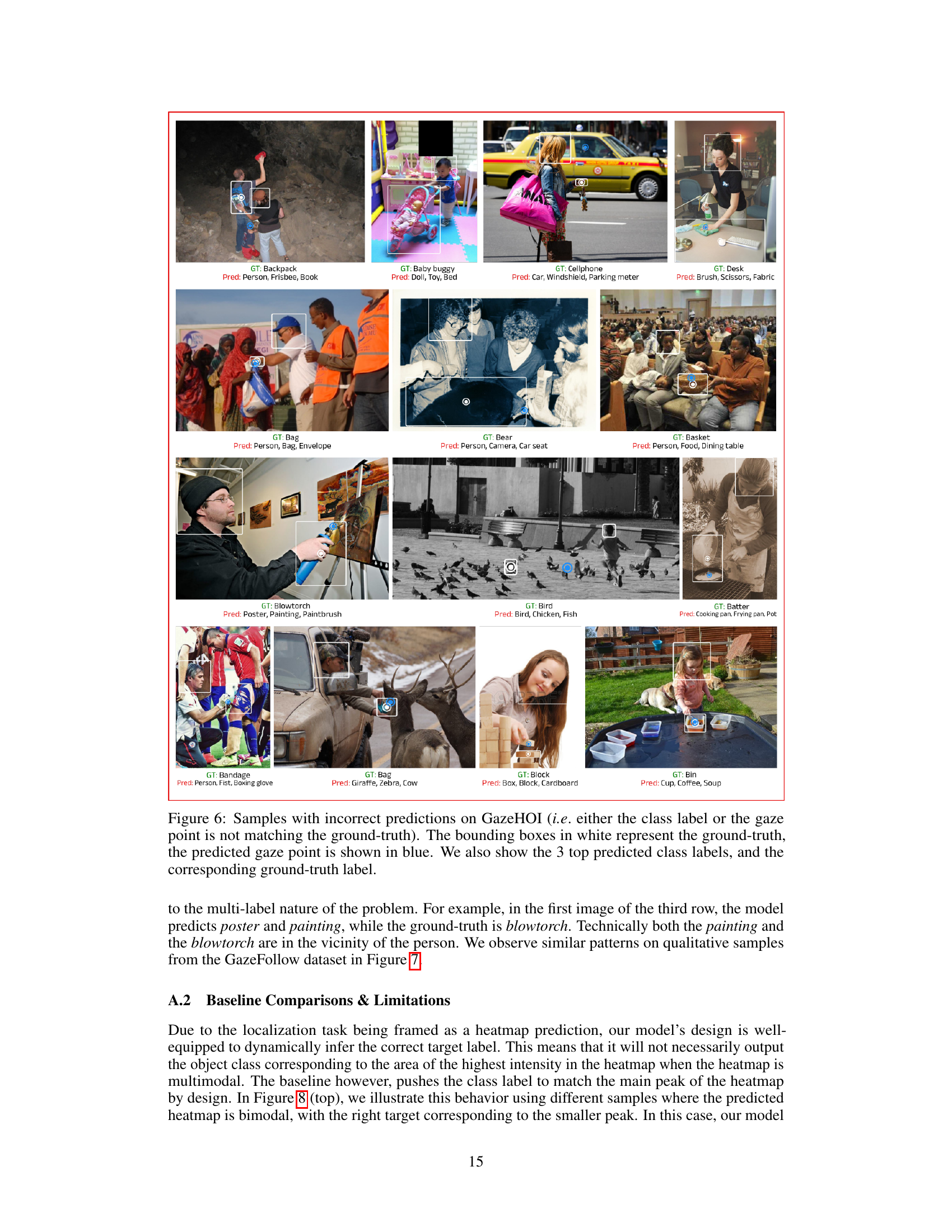

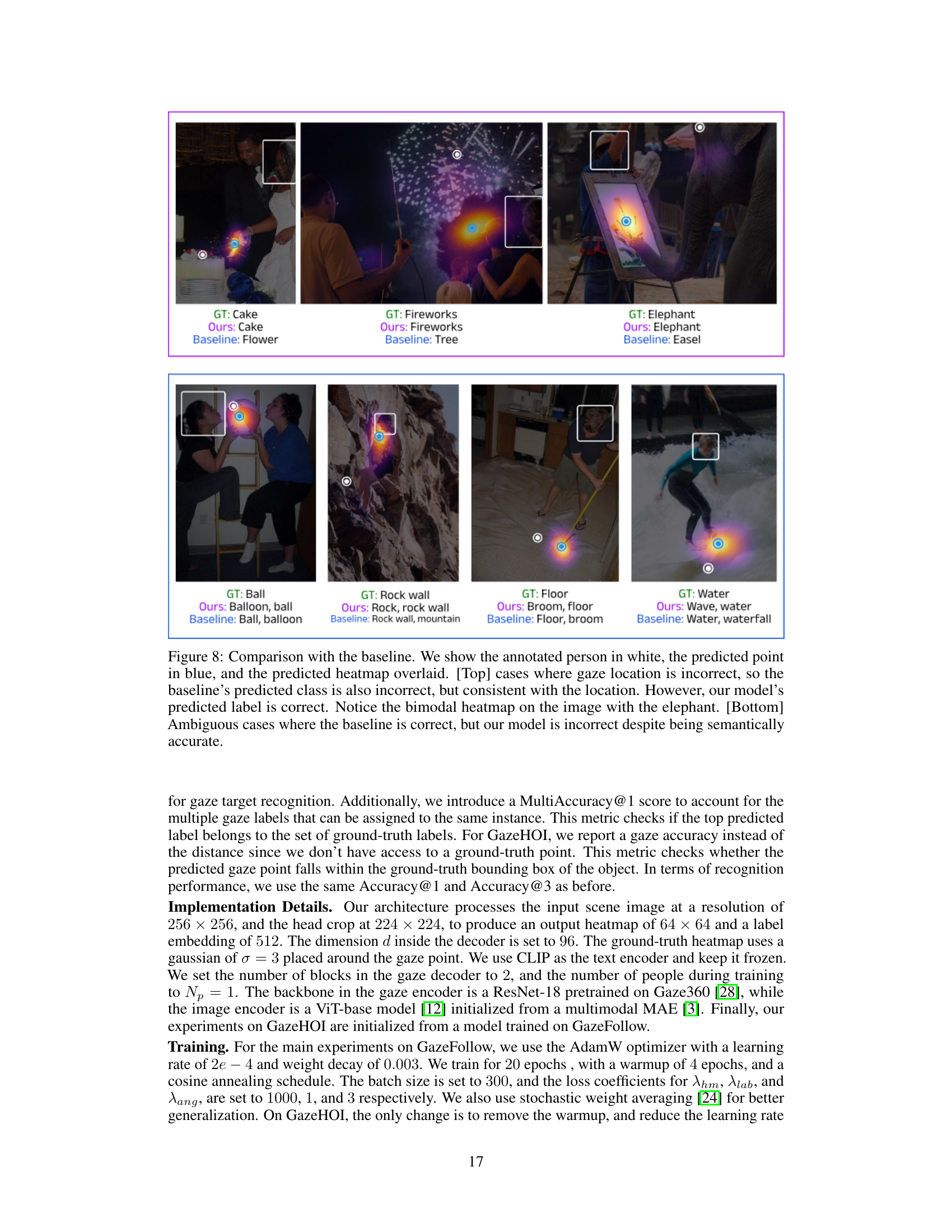

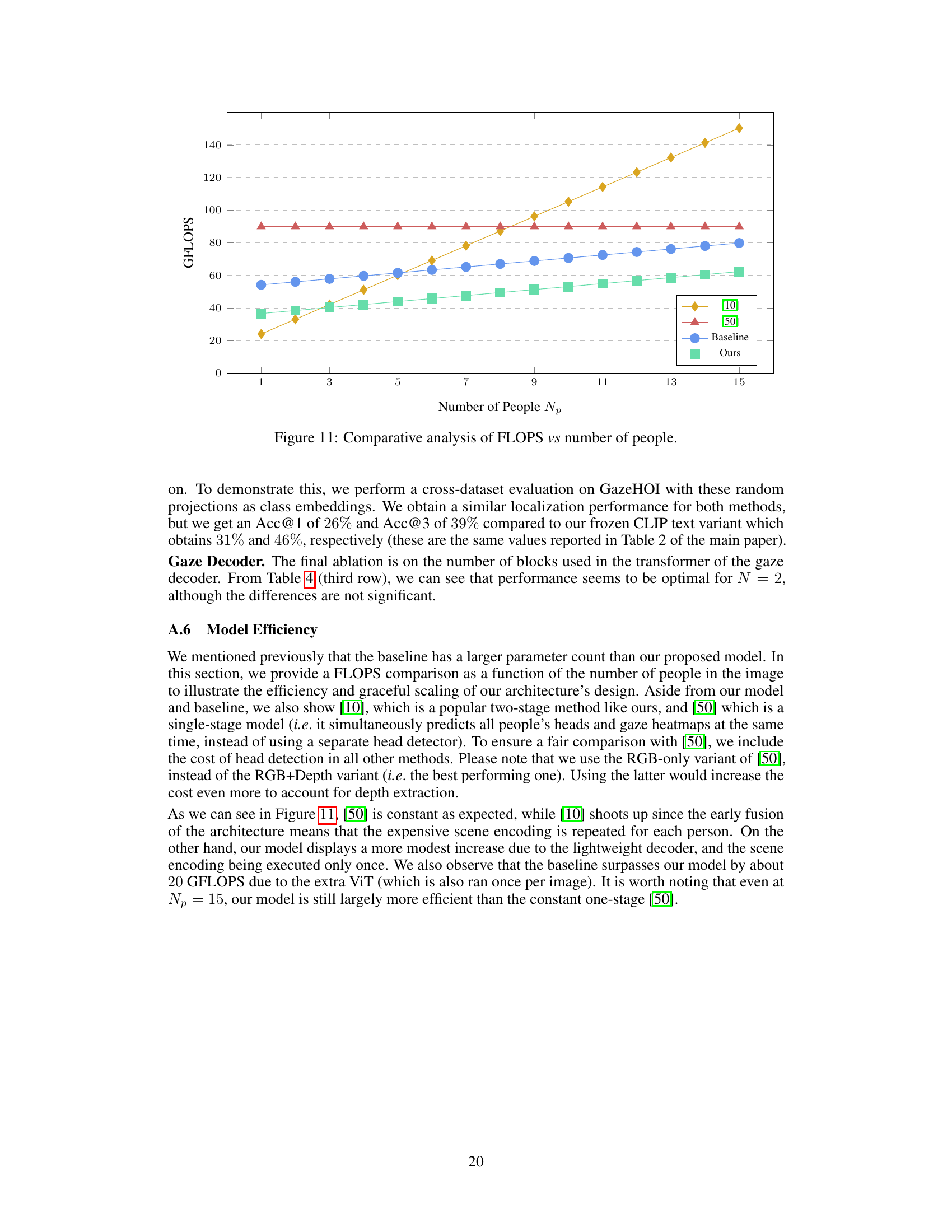

More on figures

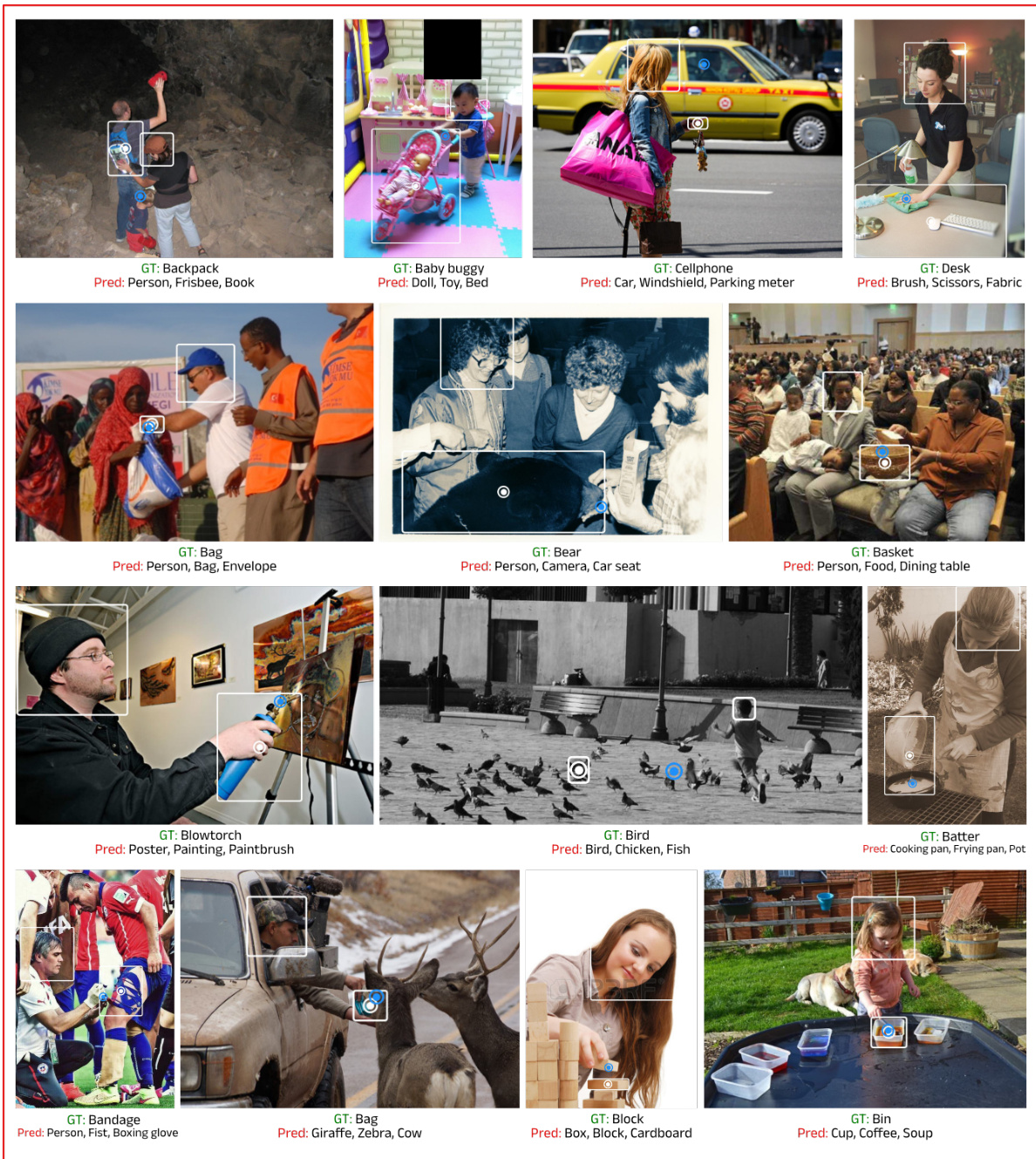

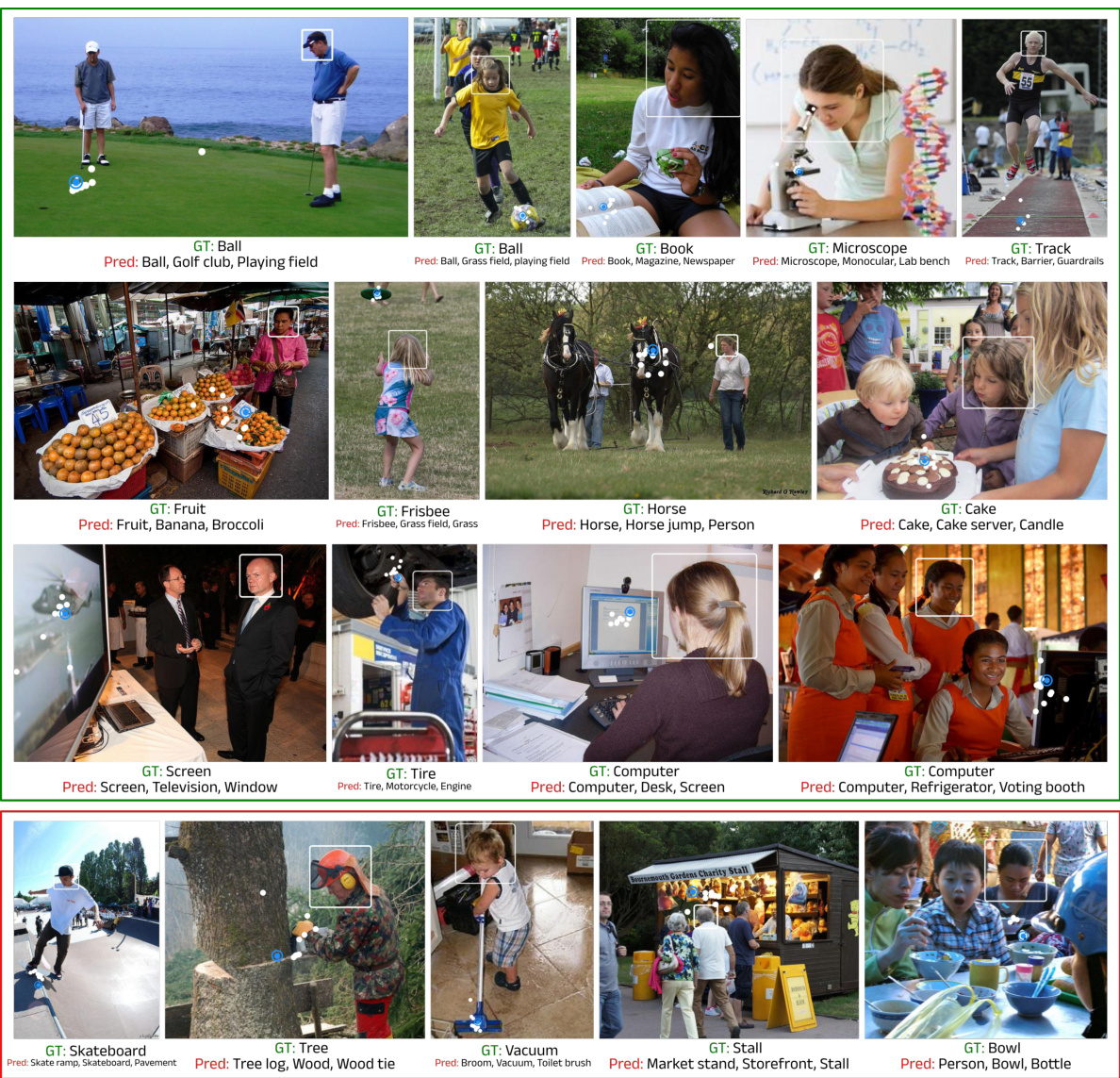

This figure shows several examples from the GazeHOI dataset. Each image contains a person whose head is enclosed in a white bounding box and an object of interest enclosed in a red bounding box. The figure visually demonstrates the diversity of scenes and objects present in the GazeHOI dataset, illustrating the task of simultaneously localizing and recognizing the gaze target.

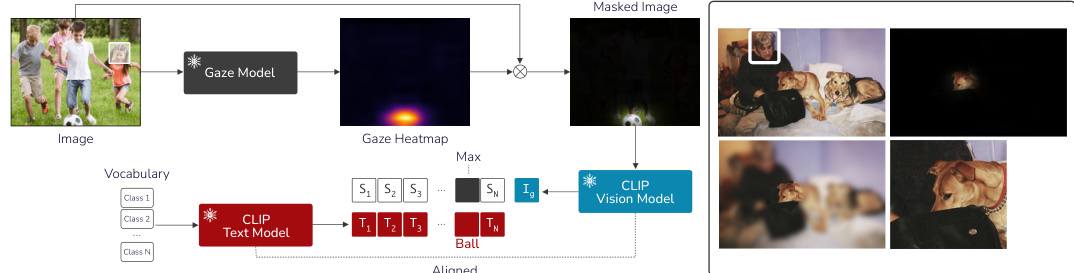

This figure illustrates the baseline architecture used for comparison in the paper. The baseline is a two-stage approach: First, the proposed gaze model predicts a gaze heatmap. This heatmap is then used to condition the input image using different methods such as masking, blurring, or cropping. Finally, CLIP’s vision model is used on the resulting image to generate the gaze label embedding, which is then compared to the available class label embeddings to predict the final class. The right side of the figure demonstrates the different image conditioning methods and their effect on the input image.

This figure displays qualitative results of the proposed model on various internet images. The first row visualizes the predicted gaze points for each person within the image, illustrating the model’s ability to identify individual gazes. The second row shows attention maps, highlighting the model’s focus on relevant image regions. The third row presents predicted gaze heatmaps for a single person, demonstrating the model’s ability to estimate gaze focus regions. Finally, the last row shows a visualization of attention weights applied to image features, indicating the significance of different regions in gaze target prediction.

This figure provides a detailed overview of the proposed architecture for semantic gaze target detection. It’s a diagram showing the flow of information through different components: Image Encoder processing the scene image, Gaze Encoder processing head crops and location, Gaze Decoder predicting heatmaps and gaze labels via cross-attention, and a Text Encoder generating class embeddings. The different components are color-coded for clarity. The overall goal is to predict both where a person is looking (gaze heatmap) and what they are looking at (semantic label).

This figure provides a detailed overview of the proposed architecture for semantic gaze target detection. It shows the flow of information through different components, including image and gaze encoders, a gaze decoder for heatmap and label prediction, and a text encoder for class embeddings. The architecture employs cross-attention mechanisms to integrate image and gaze information for accurate gaze target localization and semantic classification.

This figure presents a detailed overview of the proposed architecture for semantic gaze target detection. It is composed of five main components: an Image Encoder processing the scene image, a Gaze Encoder processing head crops and coordinates, a Gaze Decoder predicting gaze heatmaps and label embeddings, a Text Encoder generating class embeddings from a predefined vocabulary, and a final similarity computation step. The diagram visually illustrates the flow of information and the interactions between these components, utilizing color-coded squares to represent different types of tokens.

This figure provides a detailed overview of the proposed architecture for semantic gaze target detection. It is composed of five main components: an Image Encoder processing the scene image and producing image tokens; a Gaze Encoder processing head crops and coordinates to generate gaze tokens; a Gaze Decoder combining image and gaze tokens via cross-attention to predict gaze heatmaps and label embeddings; a Text Encoder generating class embeddings from a predefined vocabulary; and a final similarity computation step to match predicted gaze labels with vocabulary embeddings. The illustration clearly depicts the flow of information and the role of each component in the model.

This figure provides a detailed overview of the proposed architecture for semantic gaze target detection. It illustrates the flow of information through different components: an Image Encoder processing the scene image, a Gaze Encoder handling head crops and coordinates, a Gaze Decoder predicting gaze heatmaps and label embeddings, and a Text Encoder generating class embeddings. The interactions between these components, including cross-attention operations, are clearly shown. The figure highlights how the model integrates image and text information to predict both the location (heatmap) and semantic class of the gaze target.

This figure presents a detailed overview of the proposed architecture for semantic gaze target detection. It comprises five main components: 1) an Image Encoder that processes the scene image to produce image tokens; 2) a Gaze Encoder that processes head crops and coordinates to produce gaze tokens; 3) a Gaze Decoder that combines image and gaze tokens to predict gaze heatmaps and gaze label embeddings; 4) a Text Encoder that generates class embeddings from a vocabulary; and 5) a similarity computation step that matches predicted gaze label embeddings with vocabulary embeddings to determine the semantic class of the gaze target. The architecture is designed to simultaneously predict gaze localization and semantic labels.

This figure presents a detailed overview of the proposed architecture for semantic gaze target detection. It illustrates the flow of information through different components: an Image Encoder processing the scene image, a Gaze Encoder handling head crops and bounding box coordinates, a Gaze Decoder predicting gaze heatmaps and label embeddings, and a Text Encoder generating class embeddings from a predefined vocabulary. Cross-attention mechanisms connect the image and gaze information for effective gaze target prediction. The architecture is designed for efficient multi-person handling by processing the scene image once and then decoding gaze targets for each person separately.

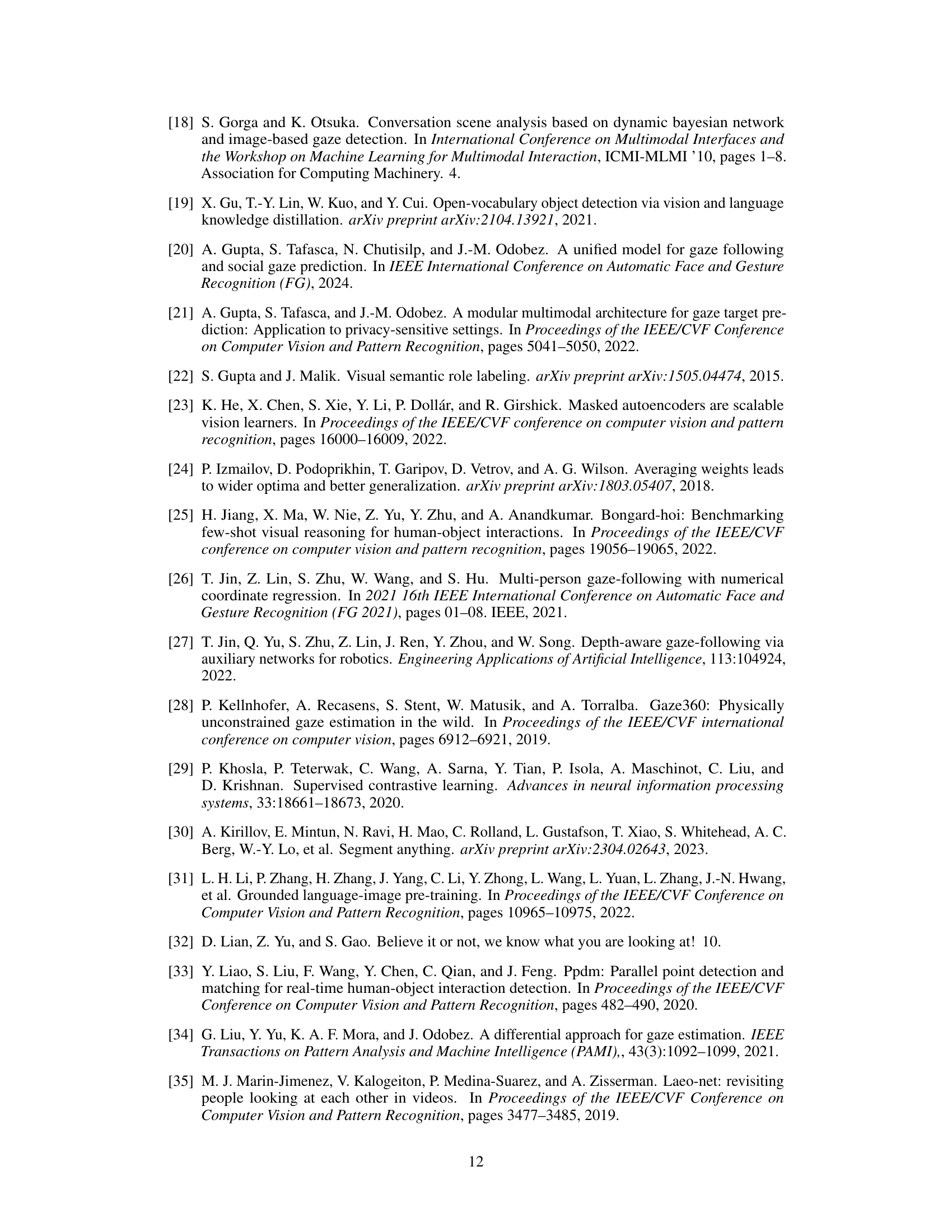

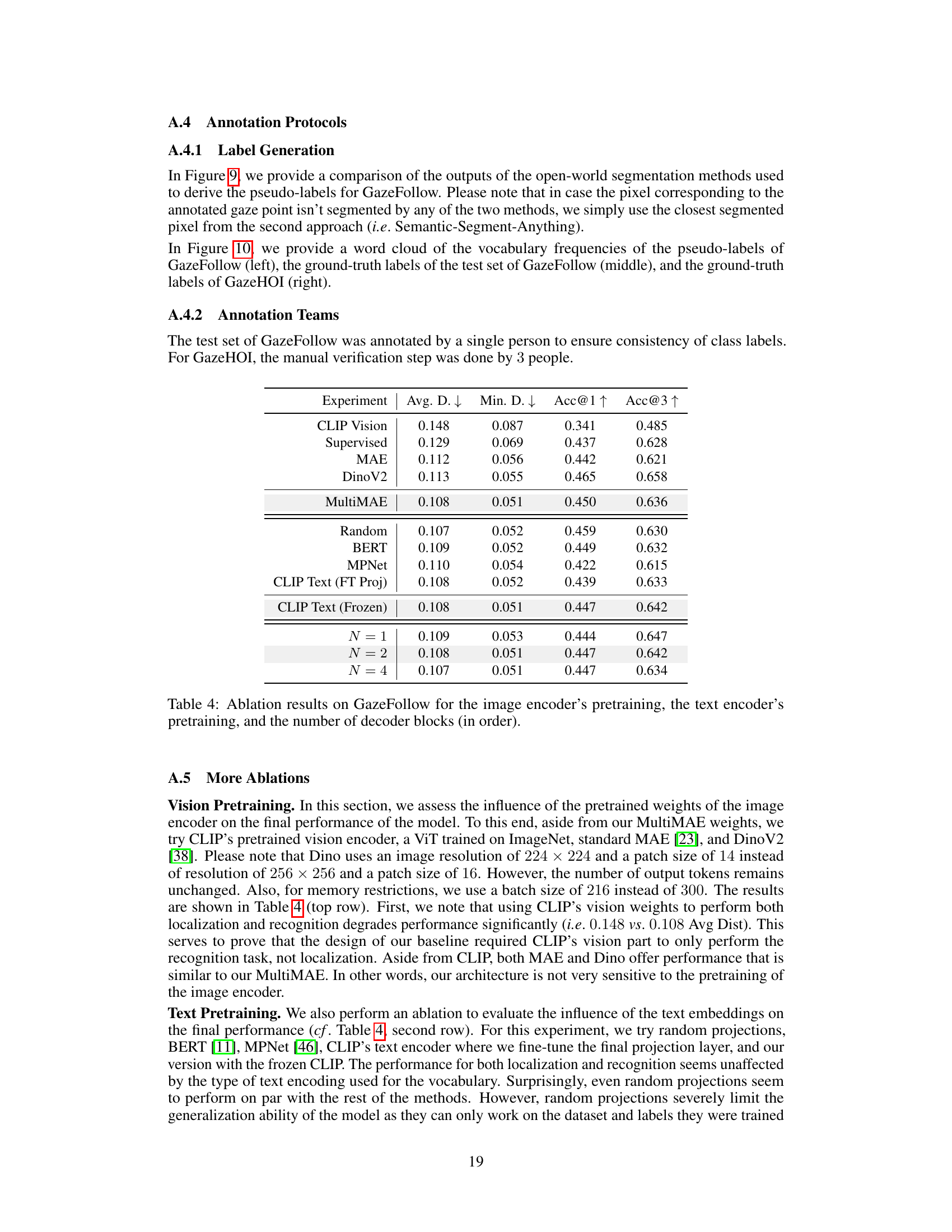

More on tables

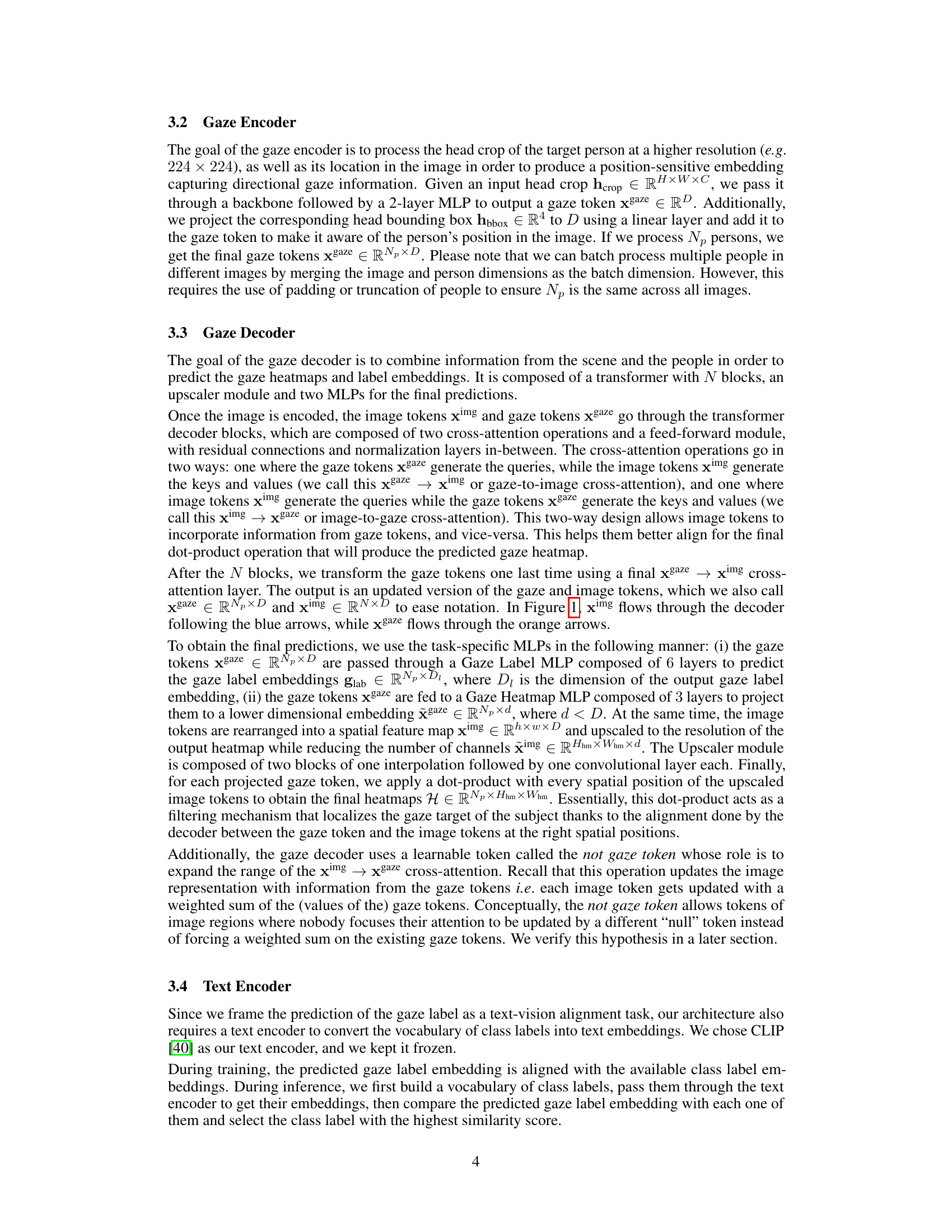

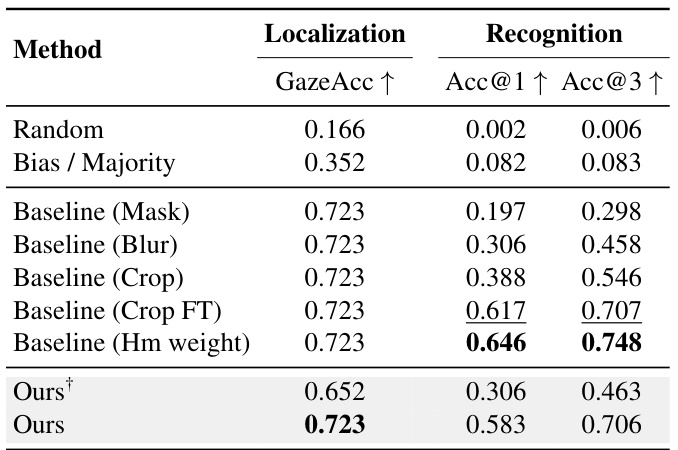

This table presents the performance comparison of different models on the Gaze-HOI dataset. The models include a random baseline, a majority baseline, several variants of a proposed two-stage baseline, and the authors’ proposed model. Both localization (GazeAcc) and recognition (Acc@1 and Acc@3) metrics are reported. The baseline models are variations of the same overall architecture that differ in how the predicted gaze heatmap is used to condition an image before being processed by CLIP to generate the gaze label embedding. One baseline model was additionally fine-tuned on the GazeFollow dataset. The authors’ model is presented in two versions: one trained only on GazeHOI and another pretrained on GazeFollow and further fine-tuned on GazeHOI. The table highlights the best performing model in each metric.

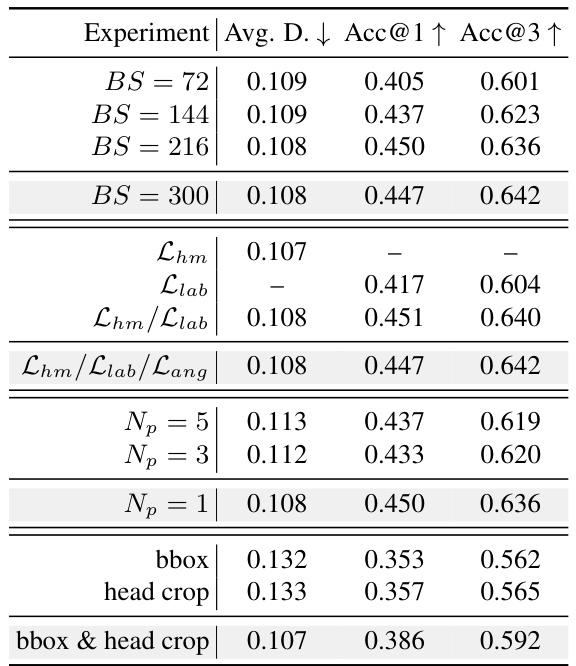

This table presents a comparison of different methods for gaze target localization and recognition on the GazeFollow dataset. It shows the average and minimum Euclidean distances between predicted and ground truth gaze locations, as well as the accuracy of gaze target class prediction at different thresholds. The results highlight the superior performance of the proposed method compared to existing baselines and variants of the proposed model.

This table presents a comparison of different methods for gaze target localization and recognition on the GazeFollow dataset. The results are shown in terms of Average Distance (Avg. Dist.), Minimum Distance (Min. Dist.), Accuracy@1 (Acc@1), Accuracy@3 (Acc@3), and MultiAccuracy@1 (MultiAcc@1). The best performance for each metric is highlighted in bold, and the second-best is underlined. The table includes results for several baselines, which primarily differ in how the predicted gaze heatmap is used to condition the input image before feeding it into a classification model. One baseline uses a pre-trained model from a different paper ([10]) for comparison. The table demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed method in this paper.

Full paper#