↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world selection processes, such as hiring, suffer from bias and high costs. Traditional secretary problem models don’t account for these issues, leading to suboptimal strategies. This paper addresses this limitation by introducing a new model where comparing candidates from different groups incurs a cost, making the model more realistic. The goal is to find the best candidate with a limited budget for inter-group comparisons.

The research proposes dynamic threshold algorithms that account for the budget and group membership. Specifically, for the two-group scenario, they derive a recursive formula to compute the success probability, finding the optimal algorithm among memory-less strategies. Furthermore, numerical simulations demonstrate the effectiveness of their approach and its convergence to the classical secretary problem’s efficiency as the budget increases. This work provides practically useful algorithms and offers valuable insights into balancing cost efficiency and fairness in selection processes.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it tackles the significant challenge of bias in online selection processes, a very common problem in various fields. It offers a novel approach by explicitly modeling the cost of inter-group comparisons, leading to more realistic and practical algorithms. The findings provide valuable insights for improving fairness and efficiency in selection processes and open new avenues for research in optimal stopping problems under budget constraints and in online algorithms with partial information.

Visual Insights#

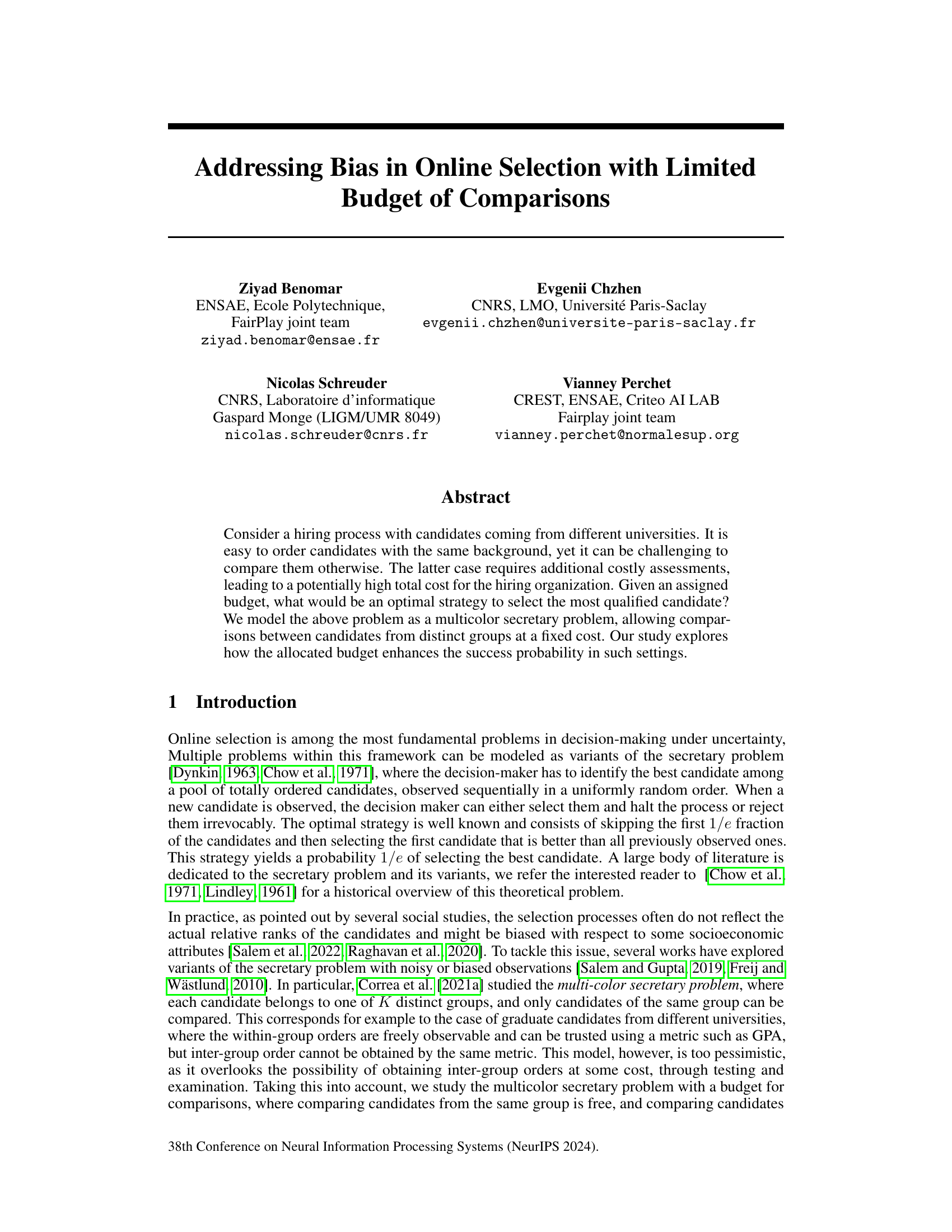

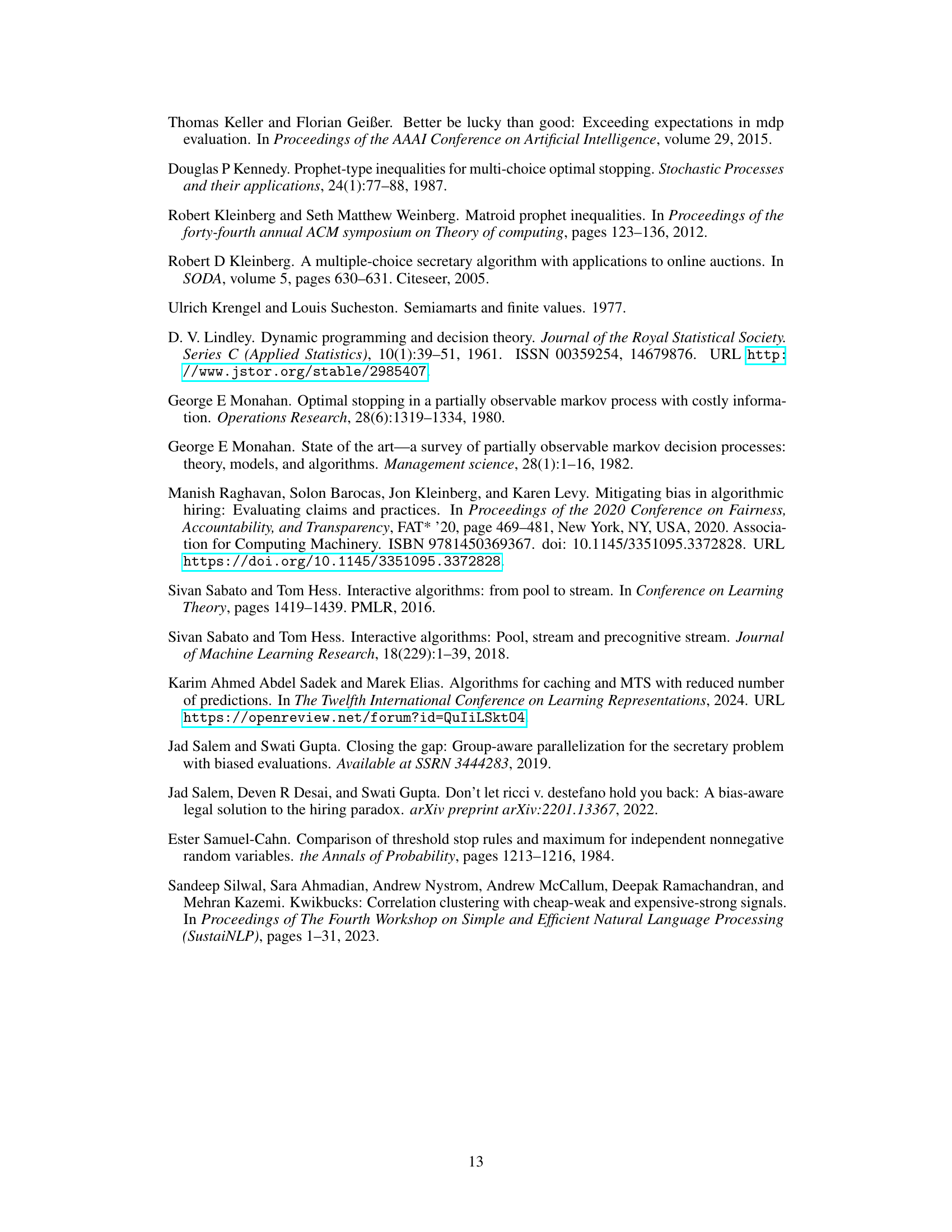

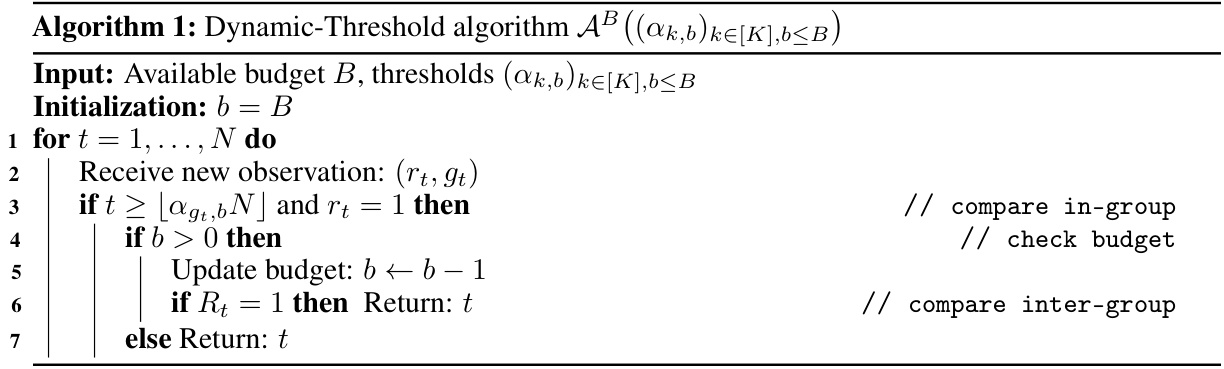

This figure illustrates how a dynamic threshold (DT) algorithm works for online candidate selection with three different groups. The x-axis represents the proportion of candidates observed (t/N), and the y-axis represents the remaining budget (b). For each group and budget level, there’s a threshold (αk,b). If a candidate’s group and rank satisfy the threshold conditions, the algorithm determines if it’s the best overall candidate using the remaining budget for inter-group comparison. The different colors represent different groups and the shaded areas represent the acceptance regions for each group under varying budgets. The decision to skip or make a comparison depends on the candidate’s group, rank, and the remaining budget, showing how the acceptance criteria adapt throughout the selection process.

In-depth insights#

Bias in Online Selection#

Bias in online selection is a critical issue that undermines fairness and meritocracy in various decision-making processes. Algorithmic bias, often stemming from biased data or flawed algorithms, can disproportionately impact certain demographic groups. This paper explores the problem in the context of online selection problems, focusing on the impact of limited resources for comparisons between candidates from different groups. The authors model the situation as a multicolor secretary problem, introducing the concept of a budget for costly inter-group comparisons. Their key contributions involve introducing and analyzing dynamic threshold algorithms that adapt to the available budget. The algorithms aim to maximize the probability of selecting the best overall candidate while accounting for the cost of comparisons. The paper tackles the inherent complexity of balancing fairness, efficiency, and the inherent uncertainty involved in online decisions. The two-group case is studied in detail, highlighting the value of using different thresholds for different groups, and the authors provide numerical simulations to illustrate the effectiveness of their algorithms. Addressing this bias requires a multi-faceted approach, including careful data collection and preprocessing, algorithm design considerations, and a thorough understanding of the social and ethical implications. The research offers valuable insights into developing more effective and equitable online selection mechanisms.

Budget-Limited Comparisons#

The concept of ‘Budget-Limited Comparisons’ in online selection processes introduces a crucial constraint mirroring real-world scenarios where resources for evaluating candidates are limited. This constraint significantly alters the classical secretary problem by adding a cost to certain comparisons, typically between candidates from different groups. The optimal strategy shifts from a simple threshold rule to a more complex one that carefully balances the risk of rejecting a superior candidate with the cost of making additional comparisons. Algorithms designed for this setting must be adaptive and account for the interplay between the budget, the cost of comparisons, and the structure of candidate groups. This setting allows for a more realistic modeling of bias, especially if group membership correlates with protected attributes, and the algorithms become tools to mitigate the effects of bias with the given constraints. The problem’s complexity increases with the number of groups and the budget, requiring sophisticated techniques for finding optimal or near-optimal solutions. While simple single-threshold algorithms might offer some improvement, they often underperform compared to more sophisticated algorithms, especially with higher budgets. Dynamic threshold algorithms and memory-less strategies provide promising approaches in this setting. Future research can focus on developing efficient algorithms for scenarios with many groups, more complex comparison cost structures, or even partial orderings between candidates.

Dynamic Threshold Algos#

Dynamic threshold algorithms represent a novel approach to the multi-color secretary problem, adapting acceptance thresholds based on the available budget and the group of each candidate. This dynamic adjustment contrasts with static threshold methods, offering improved performance under budget constraints. The algorithms’ effectiveness stems from their ability to selectively allocate comparisons, prioritizing candidates from underrepresented groups or those with high in-group rankings, maximizing the probability of selecting the best overall candidate even with limited resources. A key challenge involves determining the optimal threshold adjustments, balancing exploration and exploitation to achieve the highest success rate. The analysis of these algorithms’ success probabilities often involves intricate recursive formulas and asymptotic analysis. The dynamic nature of the thresholds makes the analysis considerably more complex than static versions but provides a more realistic and robust strategy for real-world online selection processes.

Two-Group Analysis#

A two-group analysis in the context of a secretary problem with a limited budget for comparisons would likely involve comparing the performance of two distinct algorithms, each designed to handle a specific aspect of the problem or a specific type of candidate. One algorithm might focus on maximizing the probability of selecting the best candidate overall, while another might prioritize fairness or consider additional factors affecting candidate selection. The analysis would then contrast their success rates under varying budget constraints and candidate distributions. Key metrics could include success probability and computational efficiency. For instance, a simple threshold algorithm might perform relatively poorly for small budgets. In contrast, a more sophisticated algorithm that strategically utilizes its limited comparison budget could potentially improve performance, but at the cost of increased computational complexity. The analysis should carefully consider the trade-offs between algorithmic sophistication and performance gains to determine the best approach given resource limitations. A detailed analysis might reveal insights into how resource allocation strategies impact success probability under diverse candidate pools, particularly with varying group sizes, cost functions for comparisons, and preferences for specific candidate qualities.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could significantly expand our understanding of online selection processes under uncertainty. Extending the multicolor secretary problem with a budget to scenarios with more than two groups is a crucial next step, as it would provide a more realistic model for many real-world applications. Investigating the computational complexity of finding optimal thresholds for the dynamic threshold algorithm in the multi-group case is also vital, potentially requiring novel algorithmic approaches. Additionally, relaxing the assumption of perfect comparisons or exploring different cost models for inter-group comparisons could make the model even more practical. Finally, empirical studies testing these algorithms on real-world datasets would be essential to demonstrate their effectiveness and applicability in diverse settings, validating the theoretical findings and potentially revealing unforeseen challenges or opportunities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure shows a visual representation of a dynamic threshold algorithm for three groups. The x-axis represents the fraction of candidates observed (t/N), and the y-axis represents the remaining budget. The colored regions indicate the acceptance regions for each group, defined by acceptance thresholds that change depending on the budget and the group of the candidate. A DT algorithm sequentially observes candidates, and it determines for each candidate and its group whether to accept, reject, or compare it (if budget is available) with the best candidates from other groups.

This figure schematically illustrates a dynamic threshold (DT) algorithm for three groups. The x-axis represents the fraction of candidates seen (t/N), and the y-axis represents the remaining budget (b). The colored regions depict the algorithm’s actions. Green areas indicate accepting a candidate (after a possible inter-group comparison if budget allows), while white/grey areas denote rejecting. The boundaries of these regions are determined by group- and budget-dependent thresholds (αk,b). The figure helps to visualize how the acceptance thresholds and the algorithm’s actions dynamically adapt based on the fraction of candidates already observed and the remaining comparison budget.

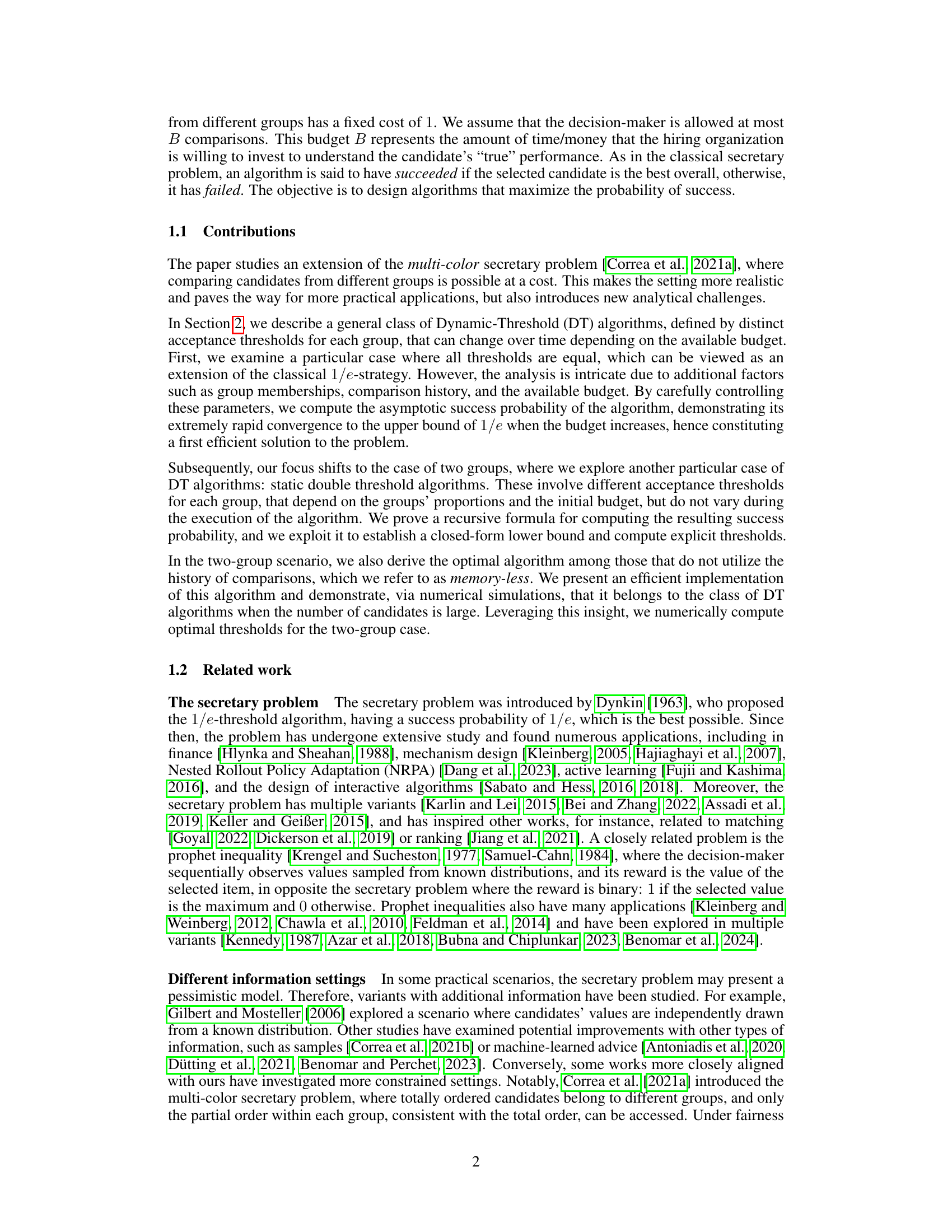

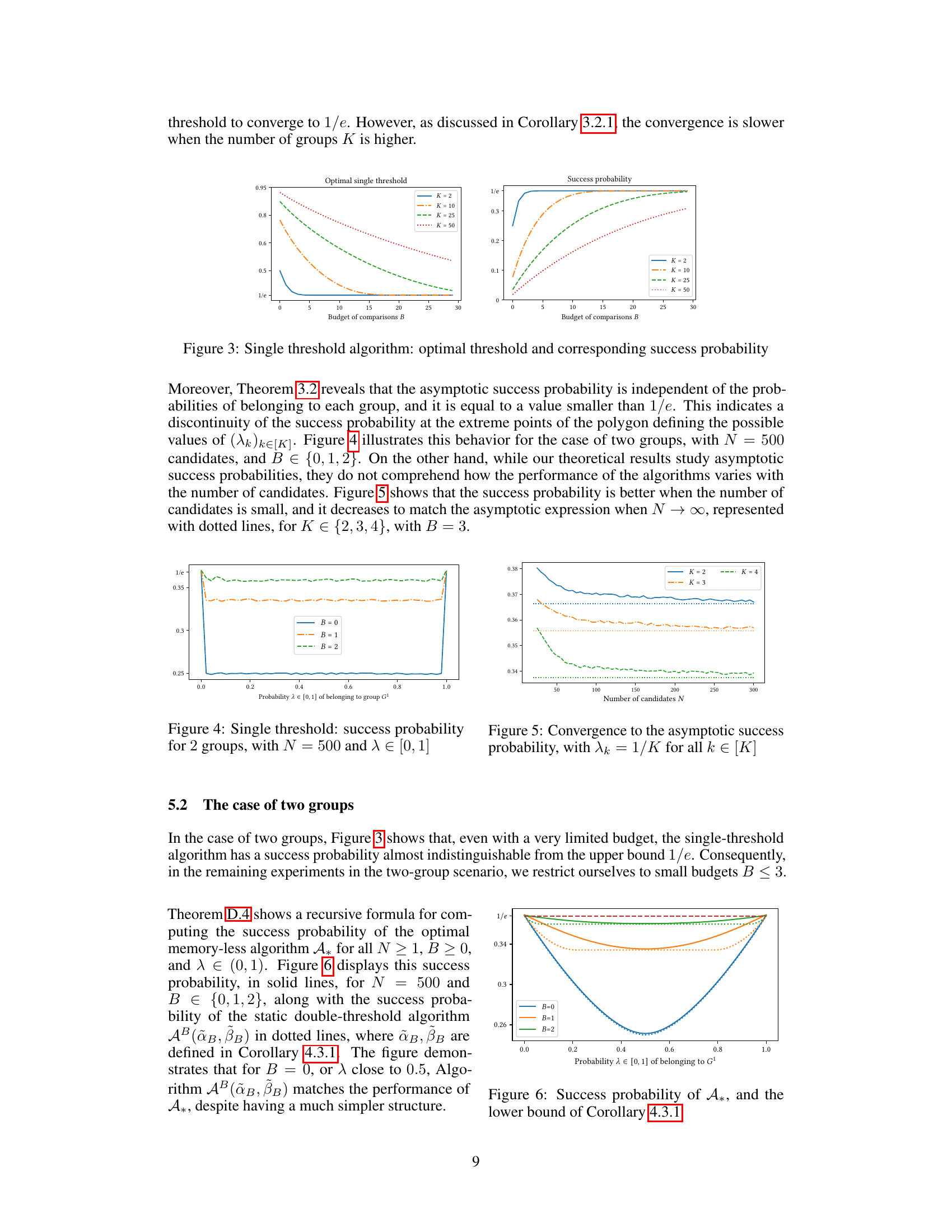

This figure displays two sub-figures. The left sub-figure shows the optimal threshold for the single-threshold algorithm with varying budget B (x-axis) and different numbers of groups K (different lines). The right sub-figure shows the corresponding success probability of the single-threshold algorithm with varying budget B and different numbers of groups K. For all K ≥ 2, as the budget grows to infinity, the optimal threshold converges to 1/e. However, the convergence is slower when the number of groups K is higher. The asymptotic success probability is independent of the probabilities of belonging to each group, and it is equal to a value smaller than 1/e. This indicates a discontinuity of the success probability at the extreme points of the polygon defining the possible values of (λk)k∈[K].

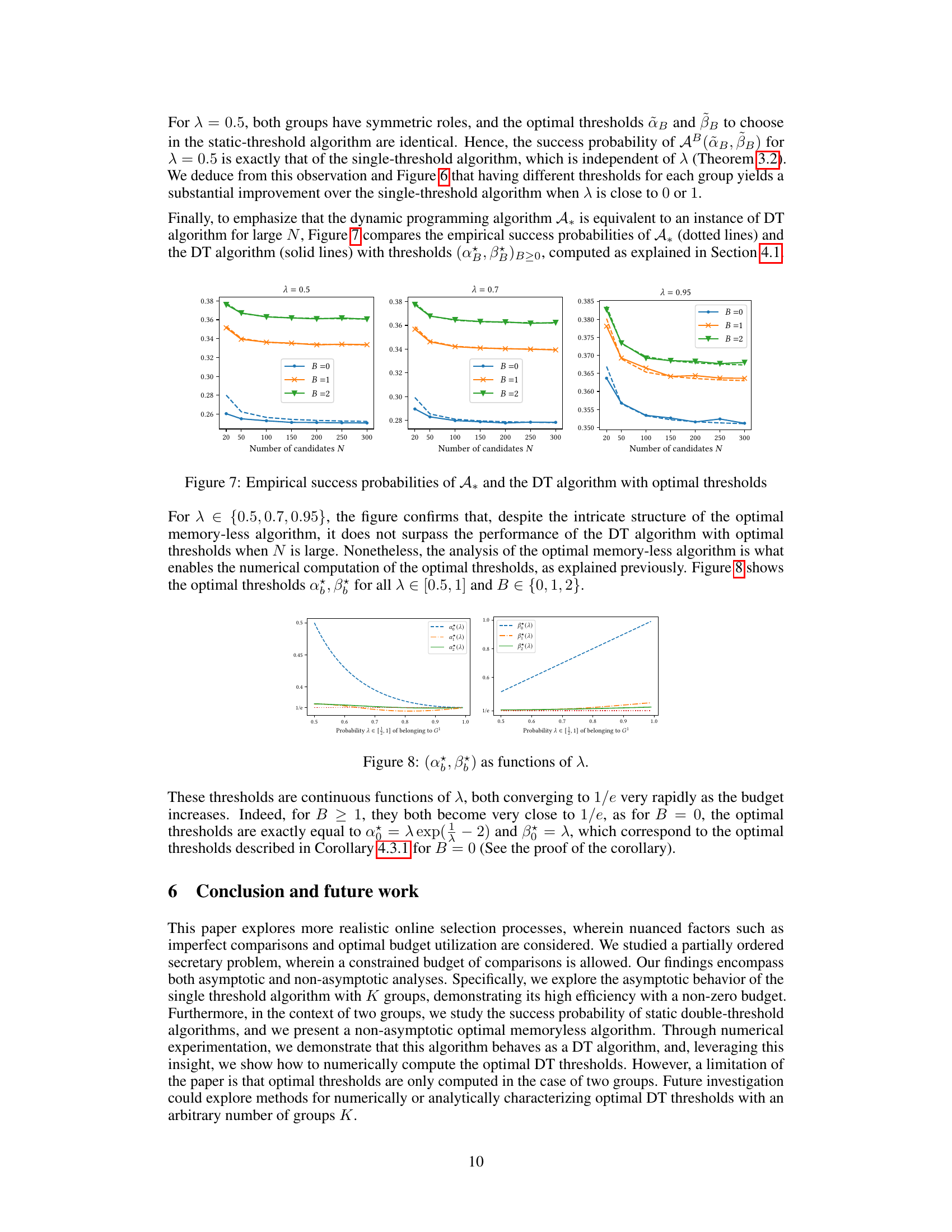

This figure shows the success probability of the single-threshold algorithm for two groups with different values of λ (probability of belonging to group G¹). The number of candidates is fixed at N=500, and three different budget values (B=0, B=1, B=2) are considered. It illustrates how the success probability varies with λ for different budget levels. Note that the plot shows that the success probability is not symmetric around λ = 0.5 and reaches the maximum value slightly below 1/e when the budget increases.

This figure illustrates how the success probability of the single-threshold algorithm converges to its asymptotic value (1/e) as the number of candidates (N) increases. Multiple lines represent different numbers of groups (K=2, 3, 4). The dotted lines show the asymptotic success probabilities derived in Theorem 3.2. The figure demonstrates that while convergence to 1/e always occurs, the rate of convergence is slower for a higher number of groups.

This figure shows how the success probability of a single-threshold algorithm varies with the probability (λ) of belonging to group G1, for different budget values (B=0,1,2) and a fixed number of candidates (N=500). The dotted line represents the asymptotic success probability (1/e) of the classical secretary problem. The plot illustrates that even with a small budget, the success probability approaches the asymptotic limit. The plot also highlights how the success probability is symmetric when λ=0.5.

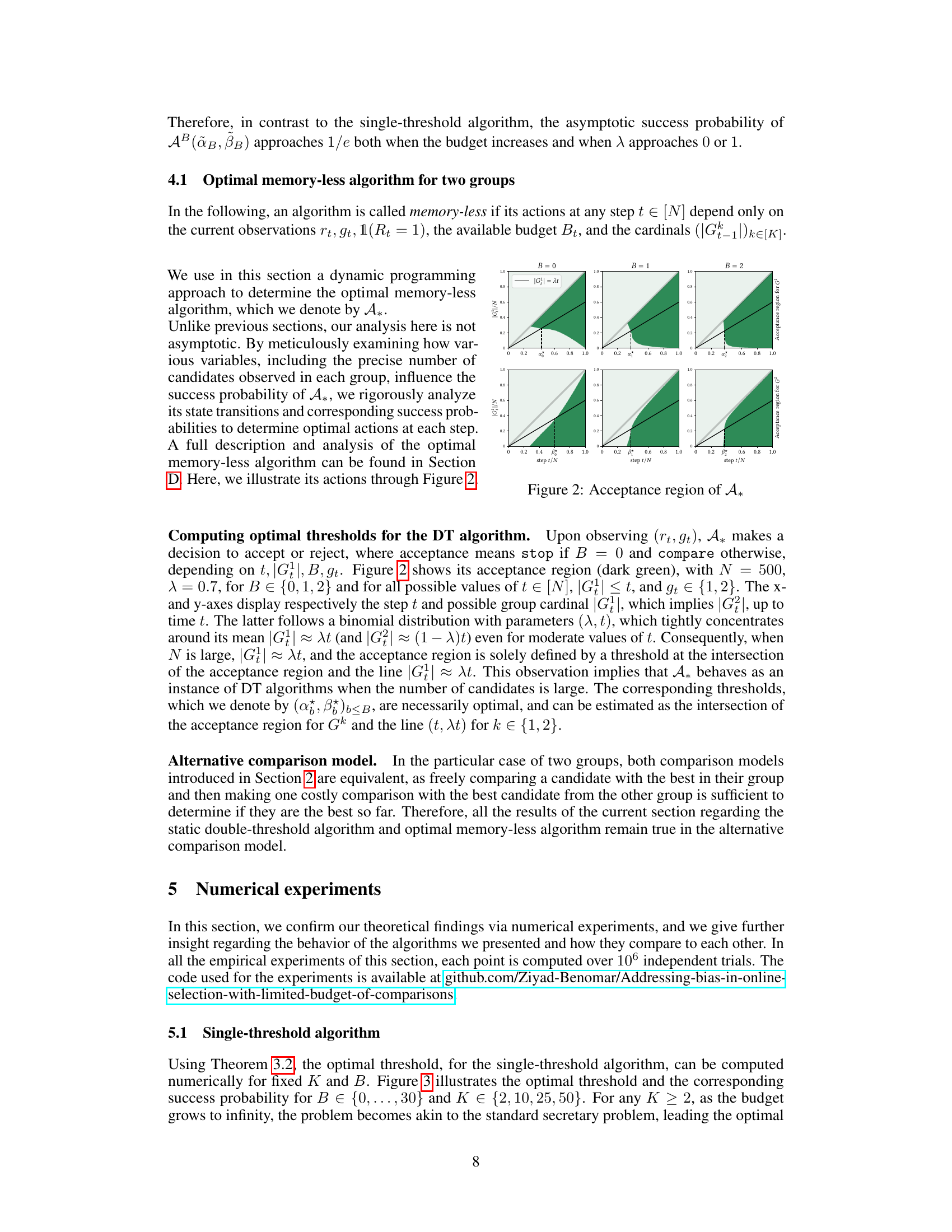

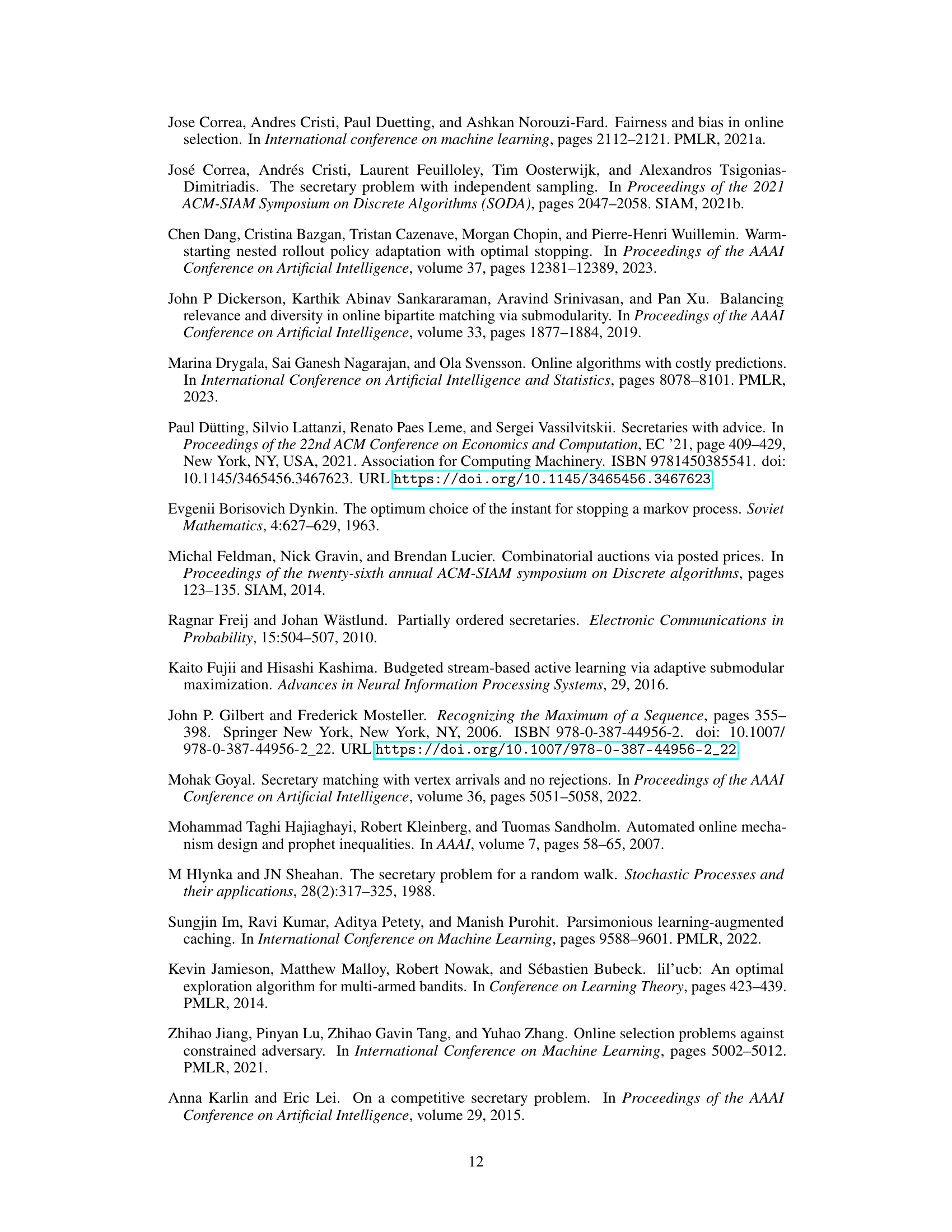

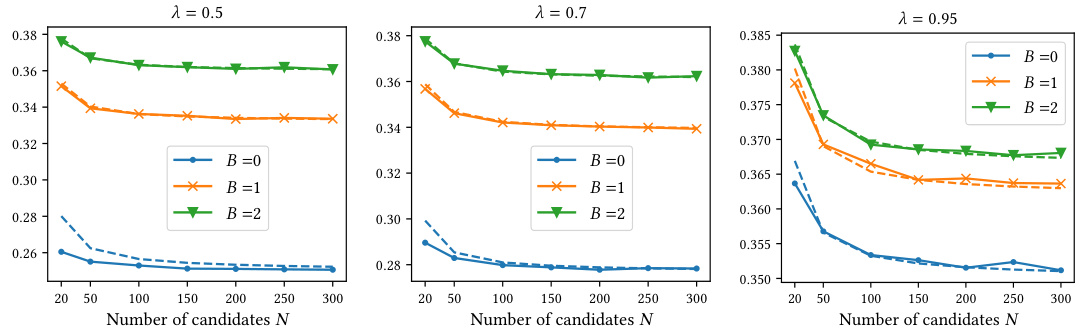

This figure compares the empirical success probabilities of two algorithms: the optimal memory-less algorithm (A*) and the dynamic threshold (DT) algorithm. The comparison is done across different numbers of candidates (N) and budget levels (B) for three different values of lambda (λ), representing the probability of belonging to group G¹. The results show that, despite the complex nature of A*, its performance closely matches that of the simpler DT algorithm, especially as N increases. This supports the finding that A* acts as a DT algorithm in larger-scale scenarios.

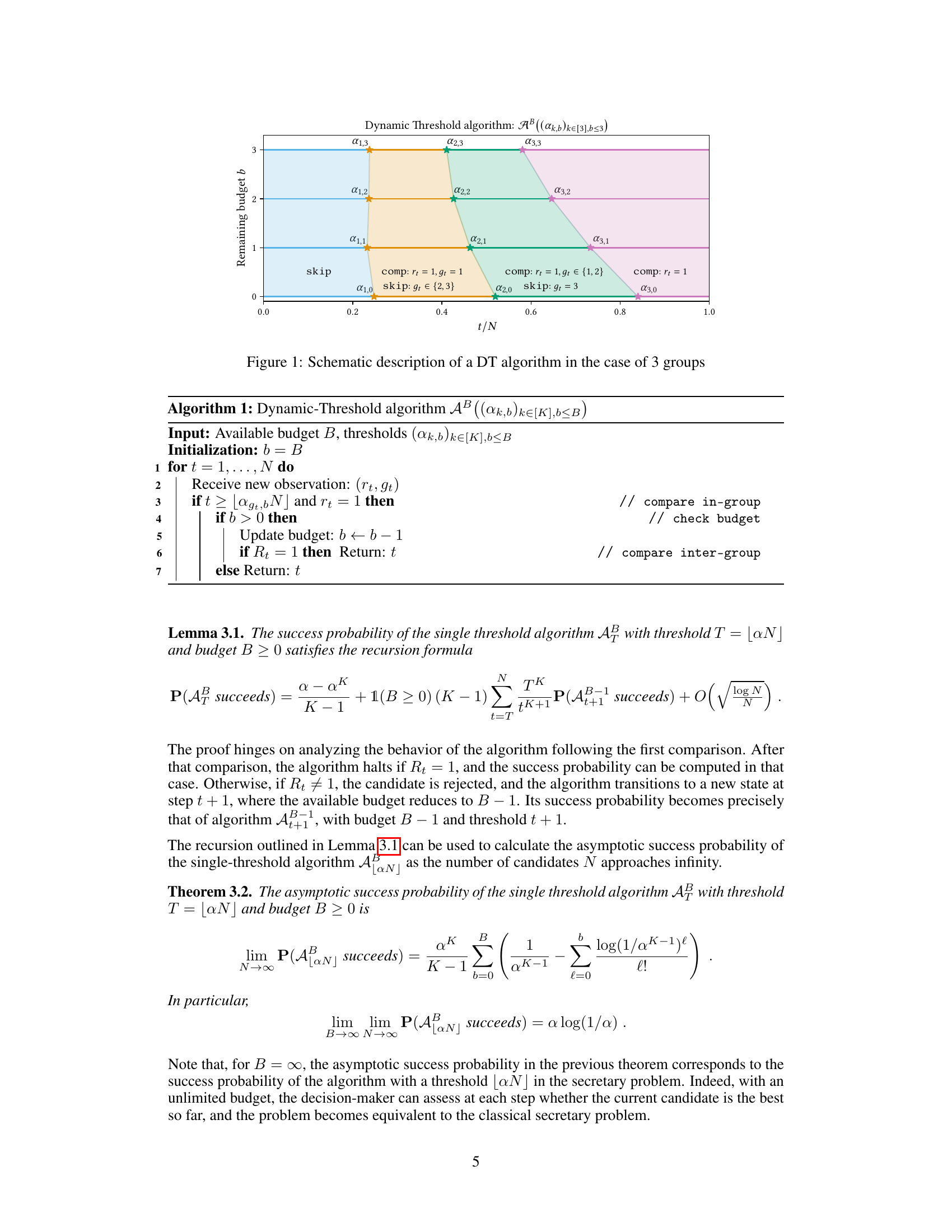

The figure shows the acceptance region of the optimal memory-less algorithm A* for two groups with different budgets (B = 0, 1, 2). The x-axis represents the step t (normalized by N), and the y-axis represents the number of candidates from group G¹ observed so far (|G¹|). The dark green area shows where the algorithm accepts the candidate. The algorithm accepts a candidate if both the time and the number of candidates from group G¹ are above certain thresholds that depend on the budget and group proportion (λ). The boundaries of these regions visualize the dynamic thresholds of A*. The plots illustrate how the algorithm’s acceptance thresholds adapt to different budgets and group sizes.

Full paper#