↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training large language models is computationally expensive. Mixture of Experts (MoE) models offer a solution by activating only a subset of parameters for each input. However, training MoEs from scratch is prohibitively expensive. Existing methods initialize MoEs using pre-trained dense models, but they often underutilize the available knowledge. This leads to suboptimal performance.

This paper introduces BAM, a simple yet effective method that fully leverages pre-trained dense models by initializing both the FFN and attention layers in MoEs. BAM utilizes soft-routing attention, which assigns each token to all attention experts, and a parallel attention transformer architecture for better efficiency. Experiments show that BAM outperforms previous methods on various benchmarks with equivalent computational and data resources.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents BAM, a novel and efficient method for training Mixture of Experts (MoE) models, which are crucial for handling large language models. The method addresses the computational cost and instability challenges associated with training MoEs from scratch by effectively utilizing pre-trained dense models. This work is relevant to researchers in natural language processing and machine learning, opening avenues for developing even larger and more efficient language models.

Visual Insights#

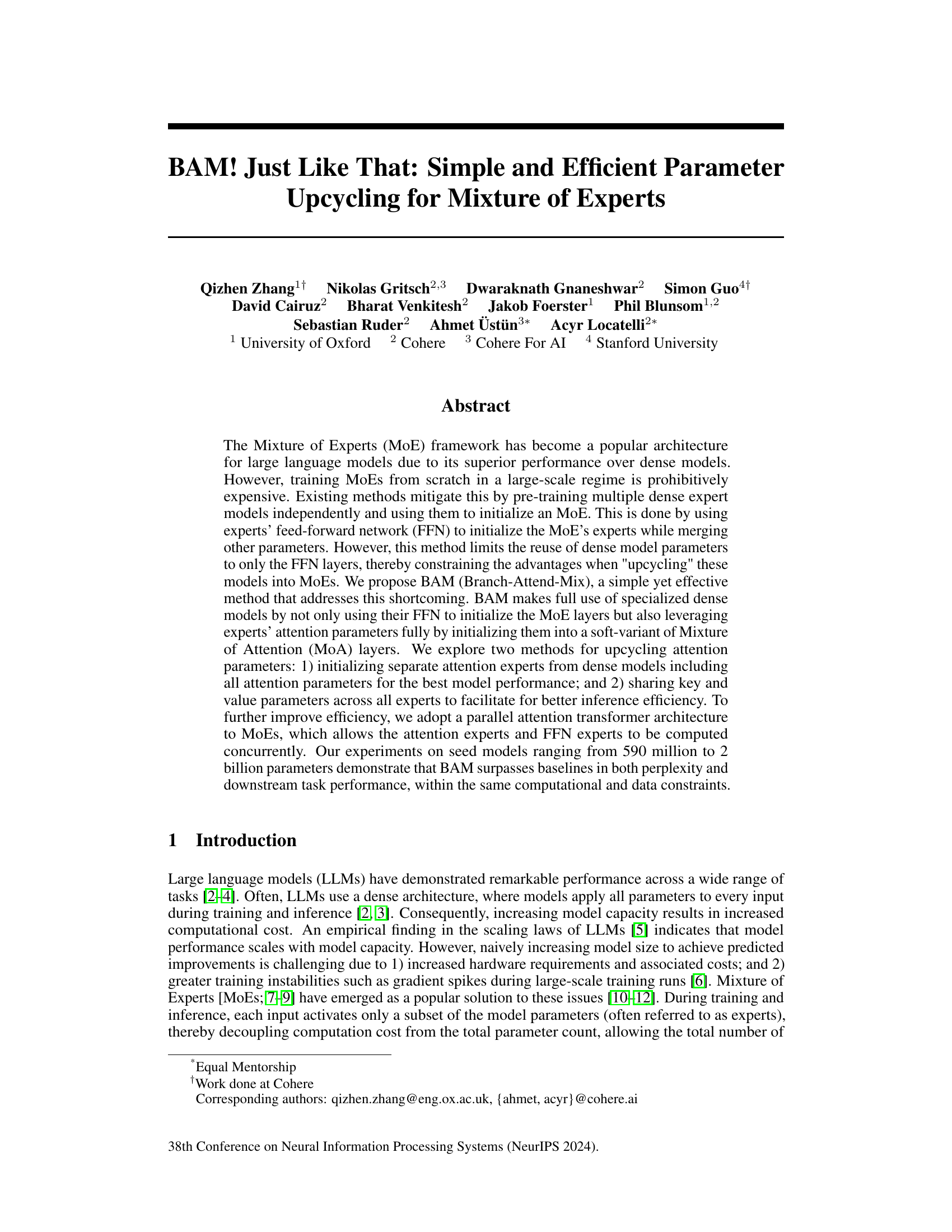

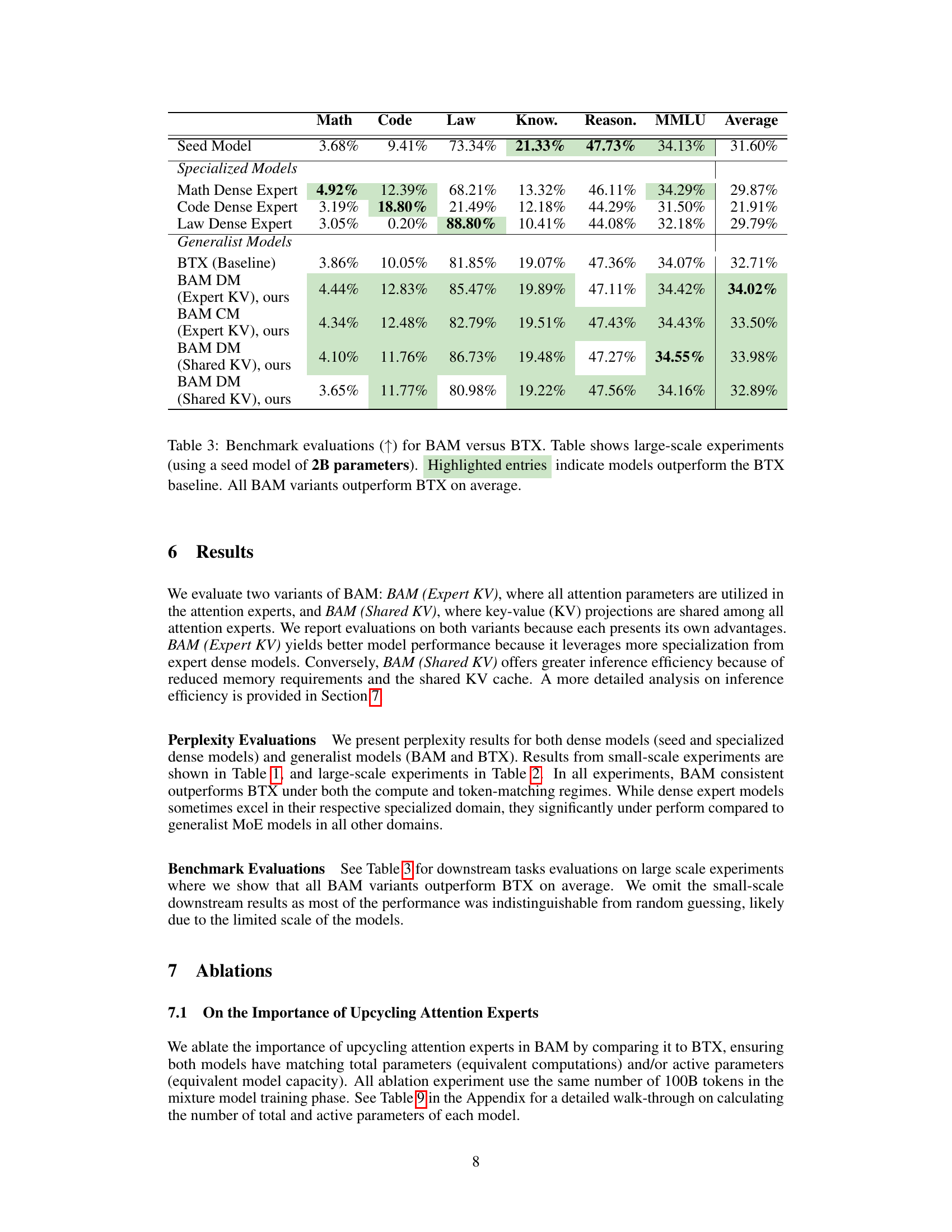

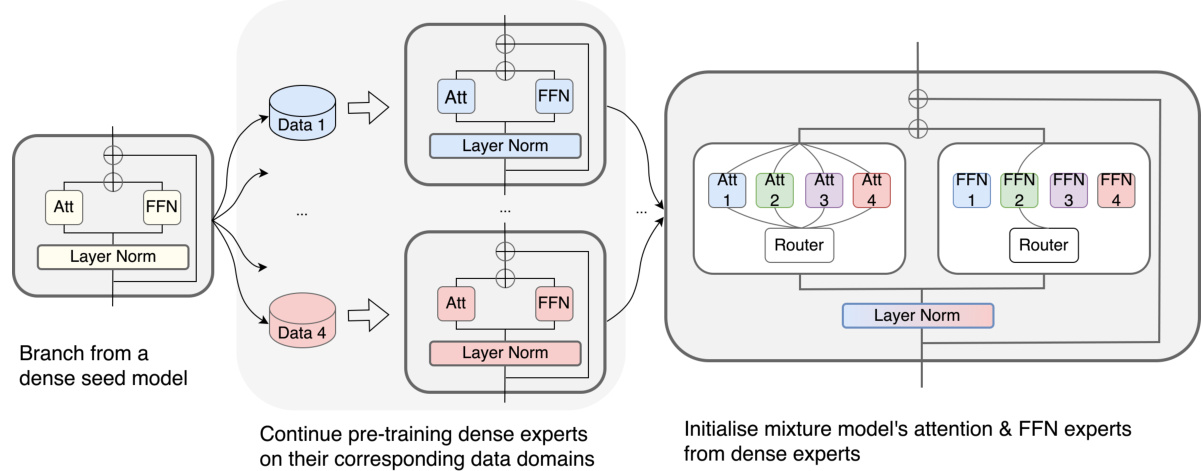

This figure illustrates the three phases of the Branch-Attend-Mix (BAM) model training process. First, a single dense seed model is branched into multiple copies. Second, each copy is independently pre-trained on a specialized dataset, creating specialized dense expert models. Finally, these specialized models are used to initialize the attention and feed-forward network (FFN) experts of the BAM mixture model, which uses a parallel attention transformer architecture for improved efficiency.

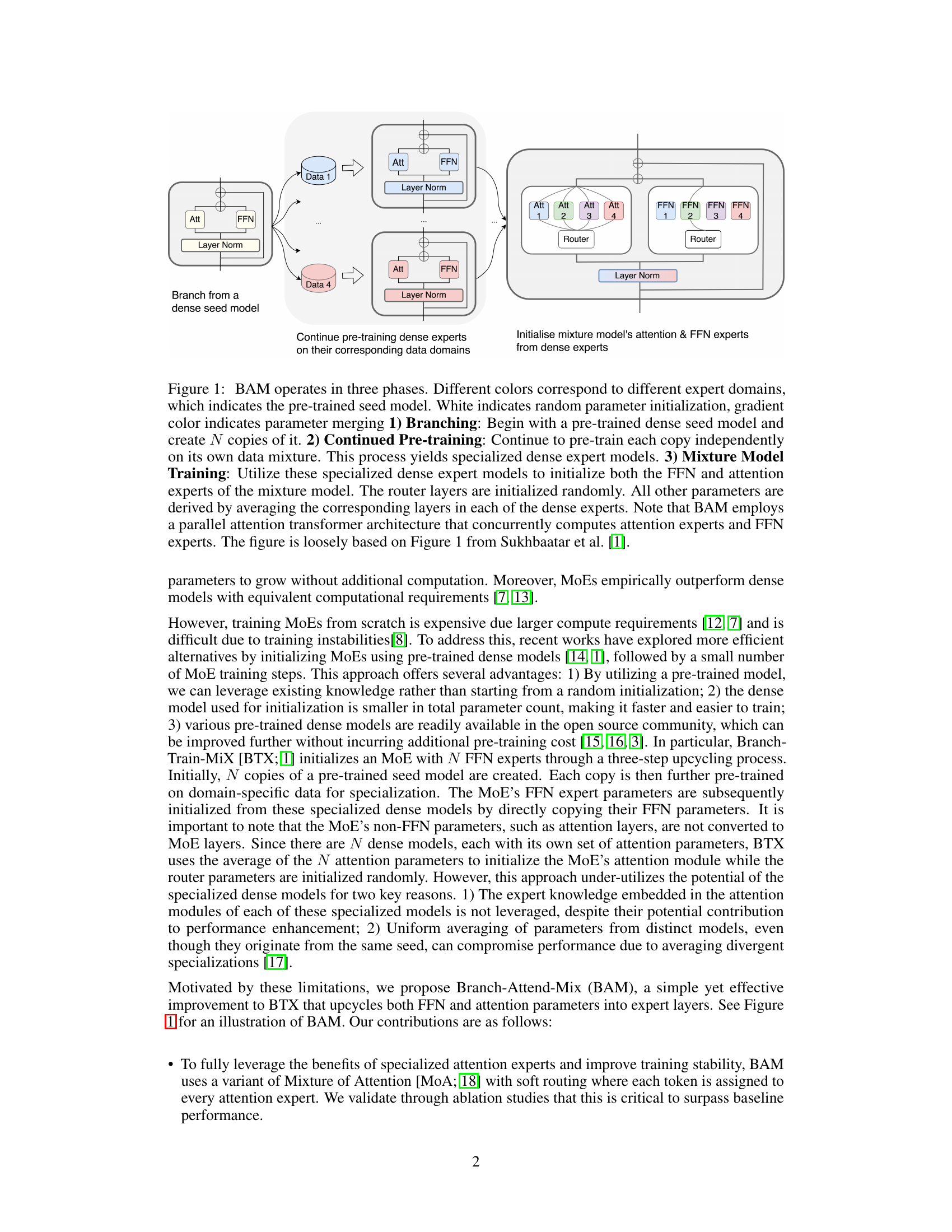

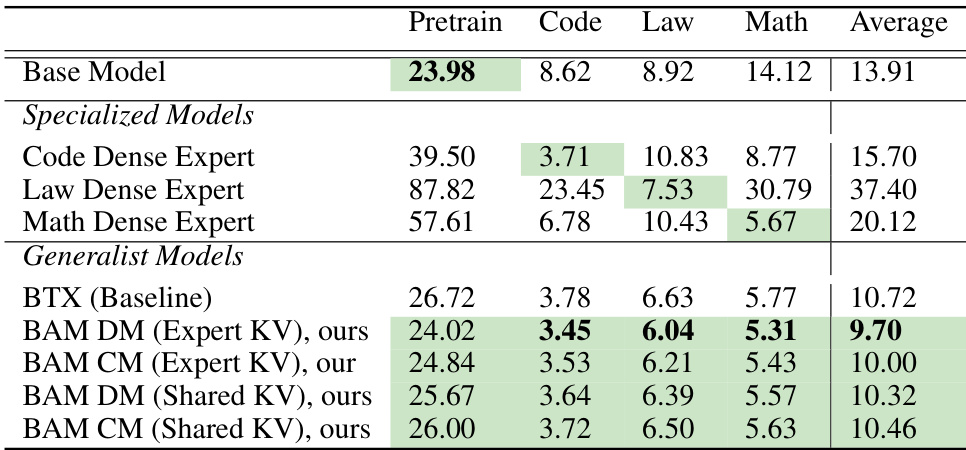

This table presents the perplexity scores achieved by different models in small-scale experiments. The models include a baseline model, specialized dense models, and generalist models like BAM and BTX. The perplexity scores are compared under two scenarios: data-matching (DM) and compute-matching (CM). Lower perplexity indicates better performance. The highlighted entries show where BAM outperforms the baseline BTX model.

In-depth insights#

MoE Parameter Upcycling#

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models offer efficiency by activating only a subset of parameters for each input. However, training MoEs from scratch is expensive. Parameter upcycling aims to leverage pre-trained dense models to initialize MoEs, reducing training costs and time. This involves intelligently transferring weights from the dense models to the MoE’s expert networks. A key challenge is efficiently utilizing all the knowledge from the dense models, including both feed-forward network (FFN) and attention parameters. Simply copying FFN layers, as some methods do, underutilizes the potential of the pre-trained models. Effective upcycling methods should fully leverage attention mechanisms, potentially through a Mixture-of-Attention (MoA) approach, for optimal performance. Efficient inference is also crucial; strategies like parameter sharing across attention experts can improve computational efficiency without significant performance loss. The success of MoE parameter upcycling hinges on the careful transfer of pre-trained weights, balancing the use of specialized expert knowledge with the need for efficient training and inference.

BAM: Branch-Attend-Mix#

The proposed method, BAM (Branch-Attend-Mix), offers a novel approach to efficiently utilize pre-trained dense models for Mixture of Experts (MoE) training. Unlike prior methods that only leverage the feed-forward network (FFN) layers of the dense models, BAM incorporates both FFN and attention parameters, fully exploiting the knowledge embedded in the pre-trained models. This is achieved through a three-phase process: branching from a seed model, continued pre-training of specialized experts, and finally, initializing the MoE using these specialized dense experts. BAM’s key innovation lies in its use of a soft-variant of Mixture of Attention (MoA), which assigns every token to all attention experts. This, coupled with a parallel attention transformer architecture, significantly improves efficiency and stability during training. The effectiveness of BAM is empirically demonstrated by surpassing baseline models in both perplexity and downstream task performance. The use of soft-routing is crucial for achieving better performance than traditional top-k routing, highlighting the importance of fully leveraging specialized attention experts.

Parallel Attention#

Parallel attention mechanisms represent a significant advancement in the field of deep learning, particularly for large language models (LLMs). By processing attention and feed-forward network (FFN) layers concurrently, parallel attention significantly enhances computational throughput without sacrificing performance. This is achieved by leveraging the inherent parallelism of these operations, allowing for a more efficient use of computational resources. The resulting speedup is crucial for training and deploying large models, enabling scalability and reducing the time required for both training and inference. The parallel approach also provides benefits in terms of training stability, as it helps alleviate issues related to imbalanced workloads and gradient instability during training. However, the use of parallel attention necessitates a careful design to ensure that the parallel components are correctly synchronized, especially in distributed training environments. Therefore, efficient implementation strategies are paramount for realizing the full potential of this technique.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model or process to understand their individual contributions. In the context of a Mixture of Experts (MoE) model, this could involve removing specific expert layers, altering routing mechanisms (e.g., switching from soft routing to top-k), or changing how attention parameters are initialized or shared across experts. Careful design of these ablation experiments is crucial. For example, simply removing an expert might not be sufficient; it’s important to consider whether to replace it with a randomly initialized equivalent to isolate the expert’s specific effect versus the impact of reducing the overall model capacity. The results of the ablation studies offer valuable insights into the model’s architecture and the effectiveness of its various components. They help to determine which parts are essential for high performance, revealing design choices that significantly impact the model’s ability to learn and generalize. This understanding is key for optimization and potential improvements. Well-executed ablations provide a robust evaluation of the contributions of different components, enhancing the reliability and generalizability of the model’s performance.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for extending the Branch-Attend-Mix (BAM) model. Optimizing the training data mixture across BAM’s three phases (Branching, Continued Pre-training, and Mixture Model Training) is crucial. A more sophisticated approach could dynamically adjust data distribution based on model performance, potentially leading to improved specialization and generalization. Improving the training framework is another key area. The authors acknowledge that their current implementation favors training efficiency over inference speed. Future work should focus on optimization techniques tailored to inference, exploring efficient soft-routing mechanisms and memory-optimized attention mechanisms to reduce inference latency and improve resource utilization. Finally, exploring alternative MoE architectures and attention mechanisms beyond soft-routing and KV-sharing could reveal further performance gains. The potential to adapt BAM to even larger models, enabling improved performance on downstream tasks, remains a significant area for further exploration.

More visual insights#

More on tables

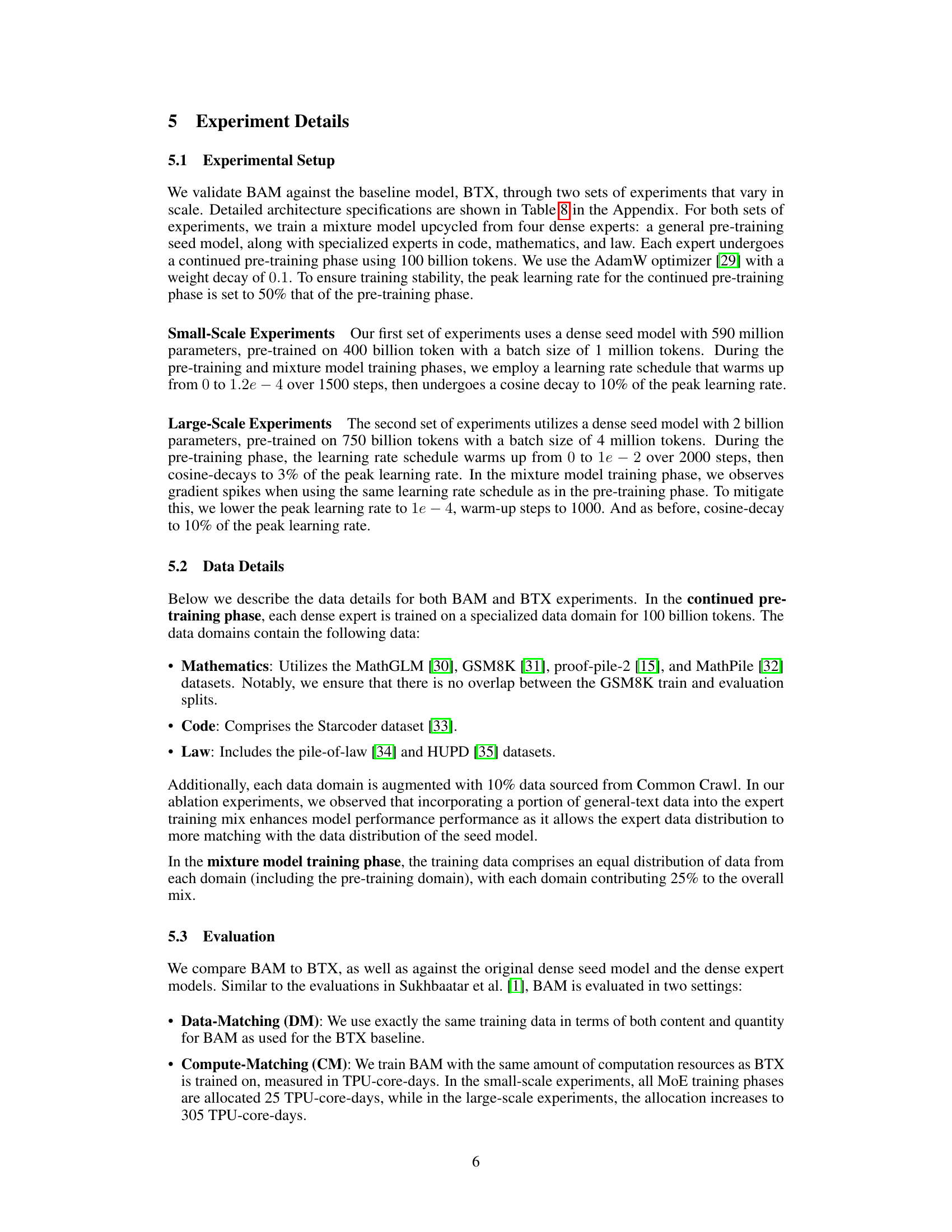

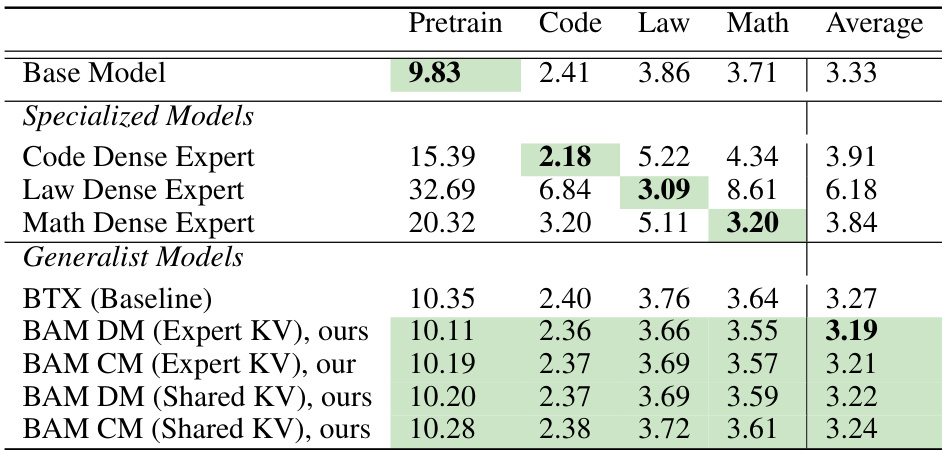

This table presents the perplexity scores achieved by different models on a large-scale experiment using a 2-billion parameter seed model. It compares the baseline BTX model with various configurations of the proposed BAM model (with and without key-value sharing, and under data-matching and compute-matching conditions). Lower perplexity scores indicate better model performance. The highlighted entries show where BAM outperforms BTX.

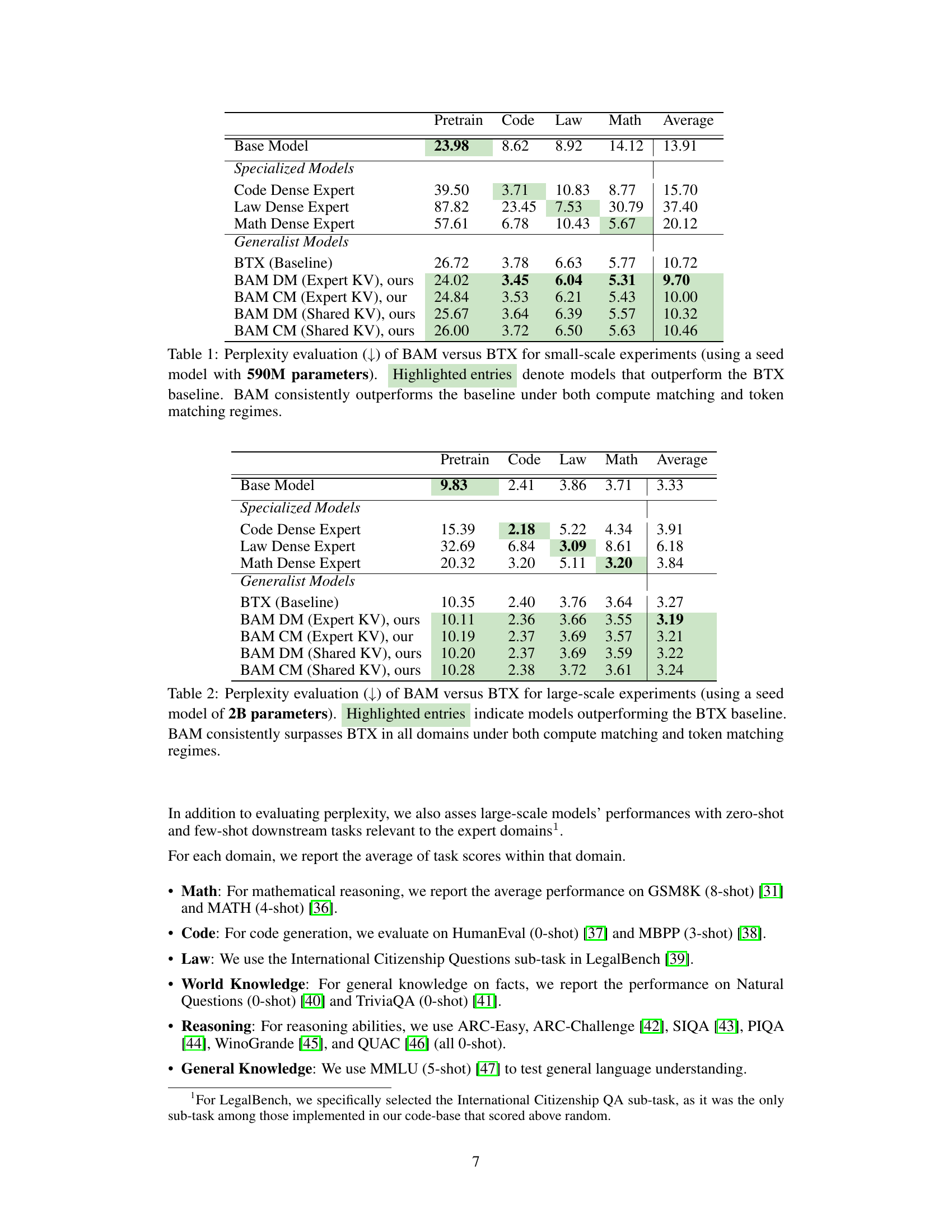

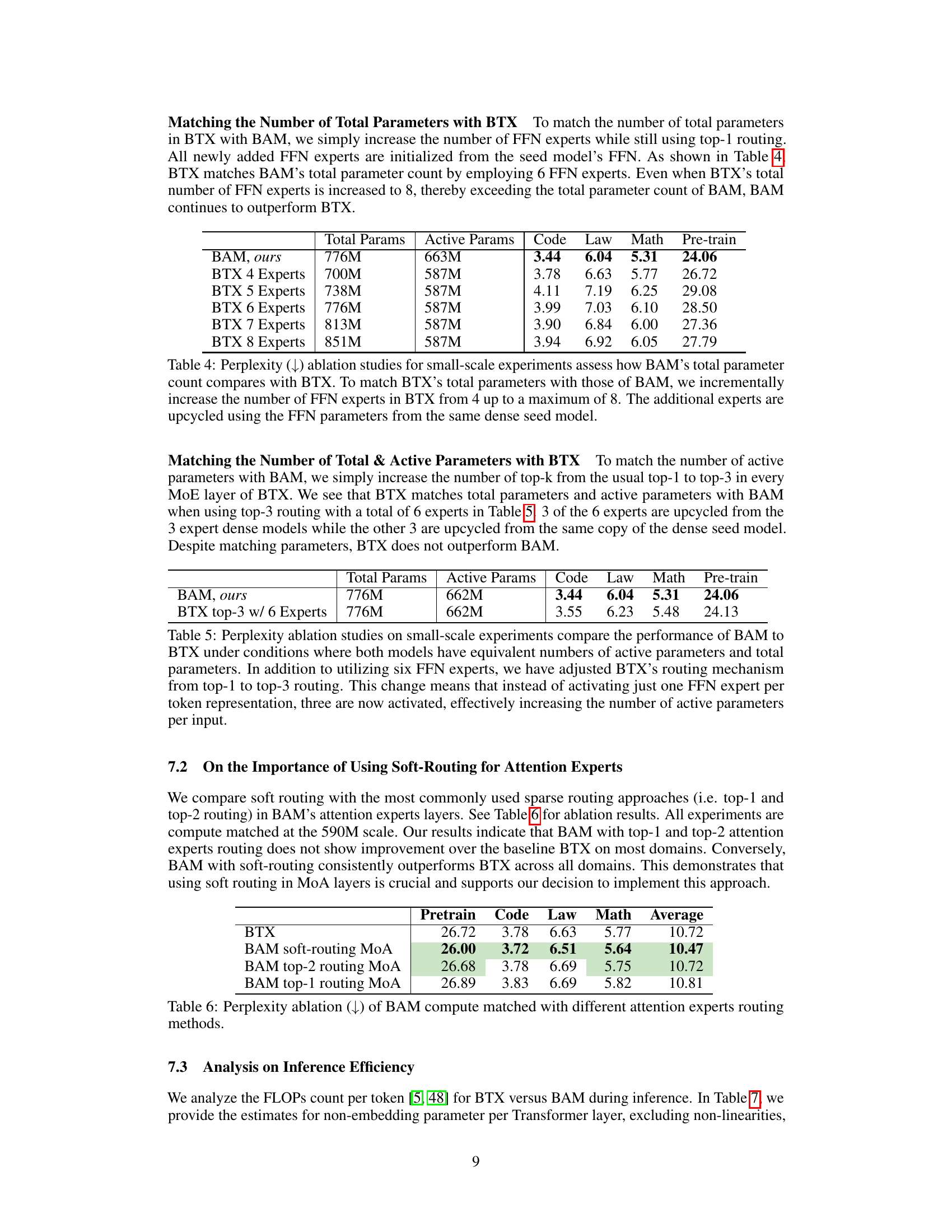

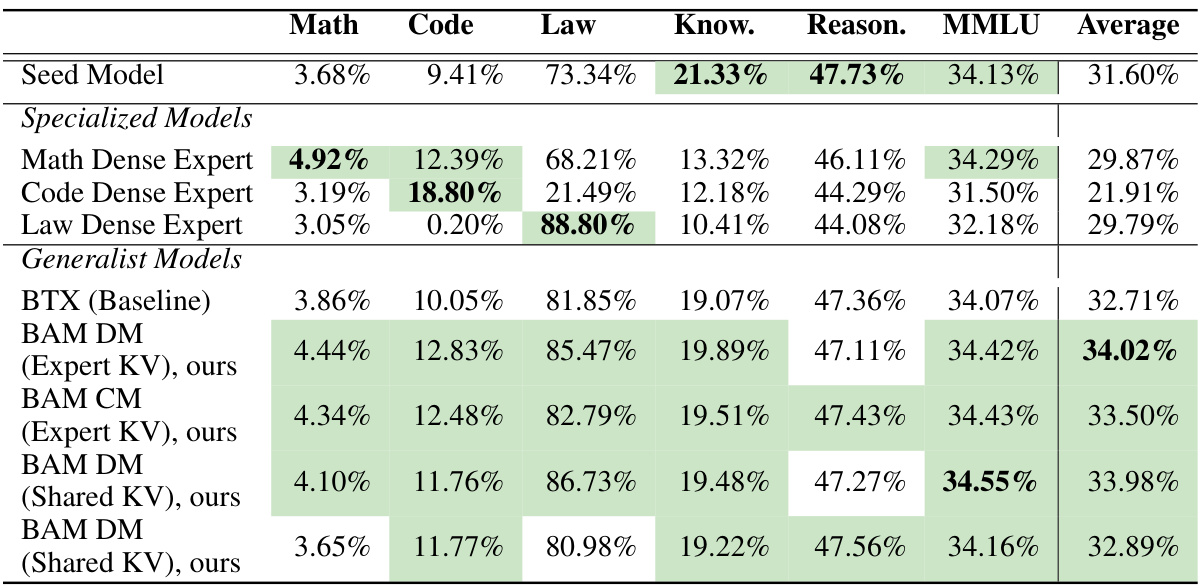

This table presents the benchmark results of different models on various downstream tasks for large-scale experiments. It compares the performance of two variants of BAM (with and without shared key-value parameters in attention experts) against the baseline BTX model and specialized dense models. The results are presented as average scores across different domains and tasks, showing that BAM consistently outperforms BTX.

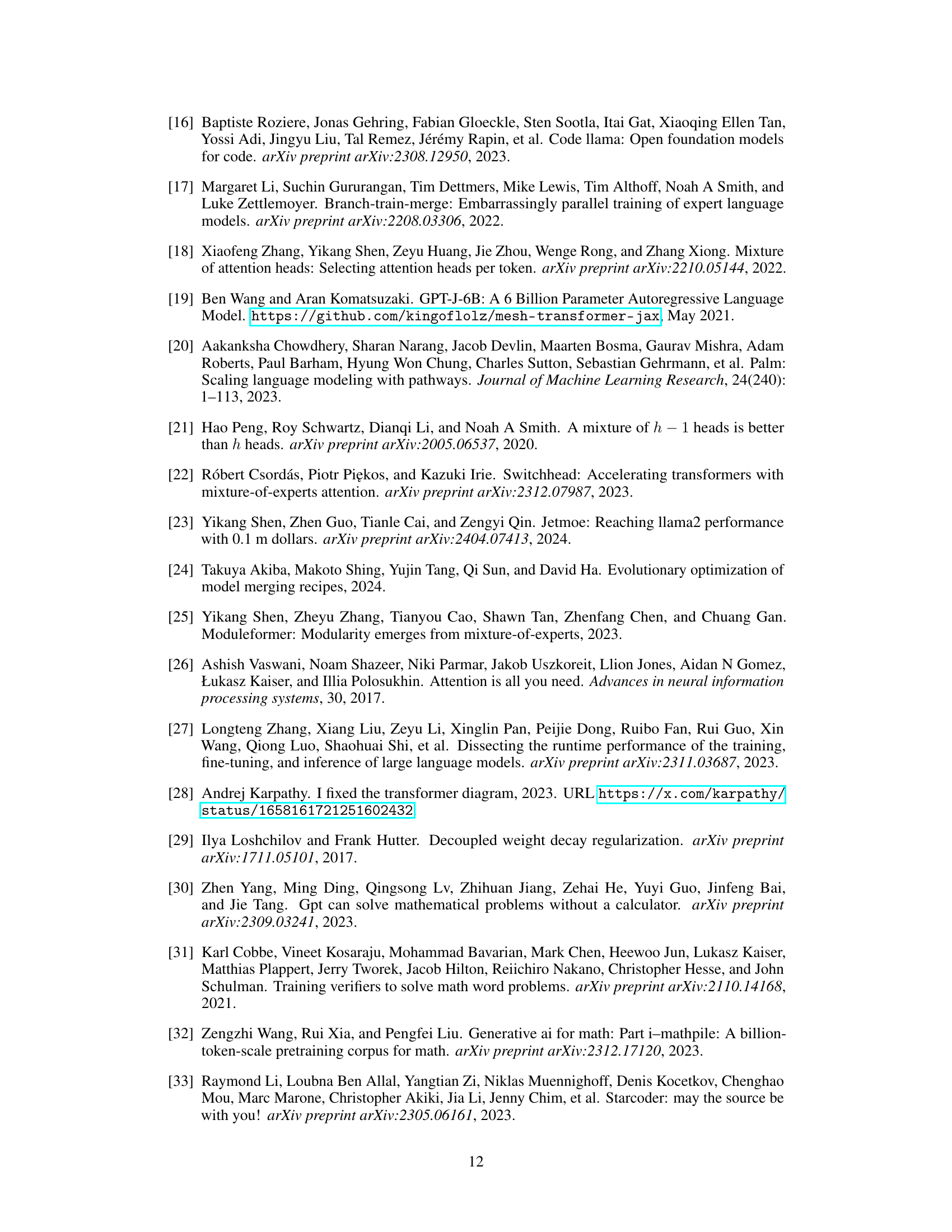

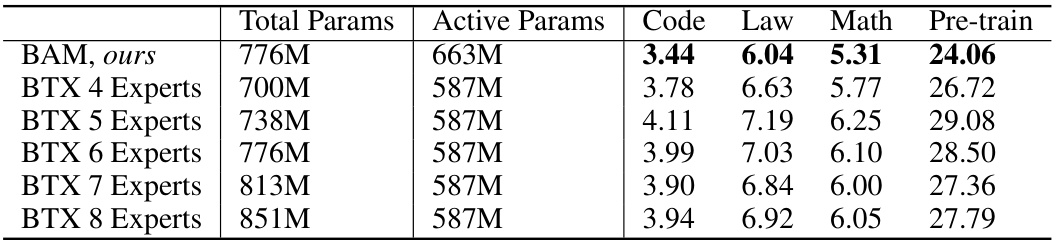

This table presents an ablation study comparing the performance of BAM and BTX models with varying numbers of total and active parameters. It shows how perplexity changes as the number of FFN experts in BTX is increased to match BAM’s total parameter count. The goal is to determine whether BAM’s superior performance is due to its unique parameter upcycling method or simply a result of having more parameters.

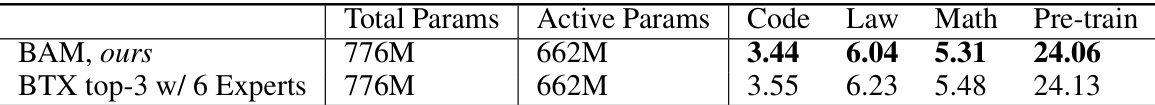

This table compares perplexity scores for BAM and a modified version of BTX where the number of active parameters and total parameters are matched to BAM. The modification to BTX involves increasing the number of experts and using top-3 routing instead of top-1 routing in the MoE layers. The results show that even when the number of parameters is matched, BAM still outperforms BTX.

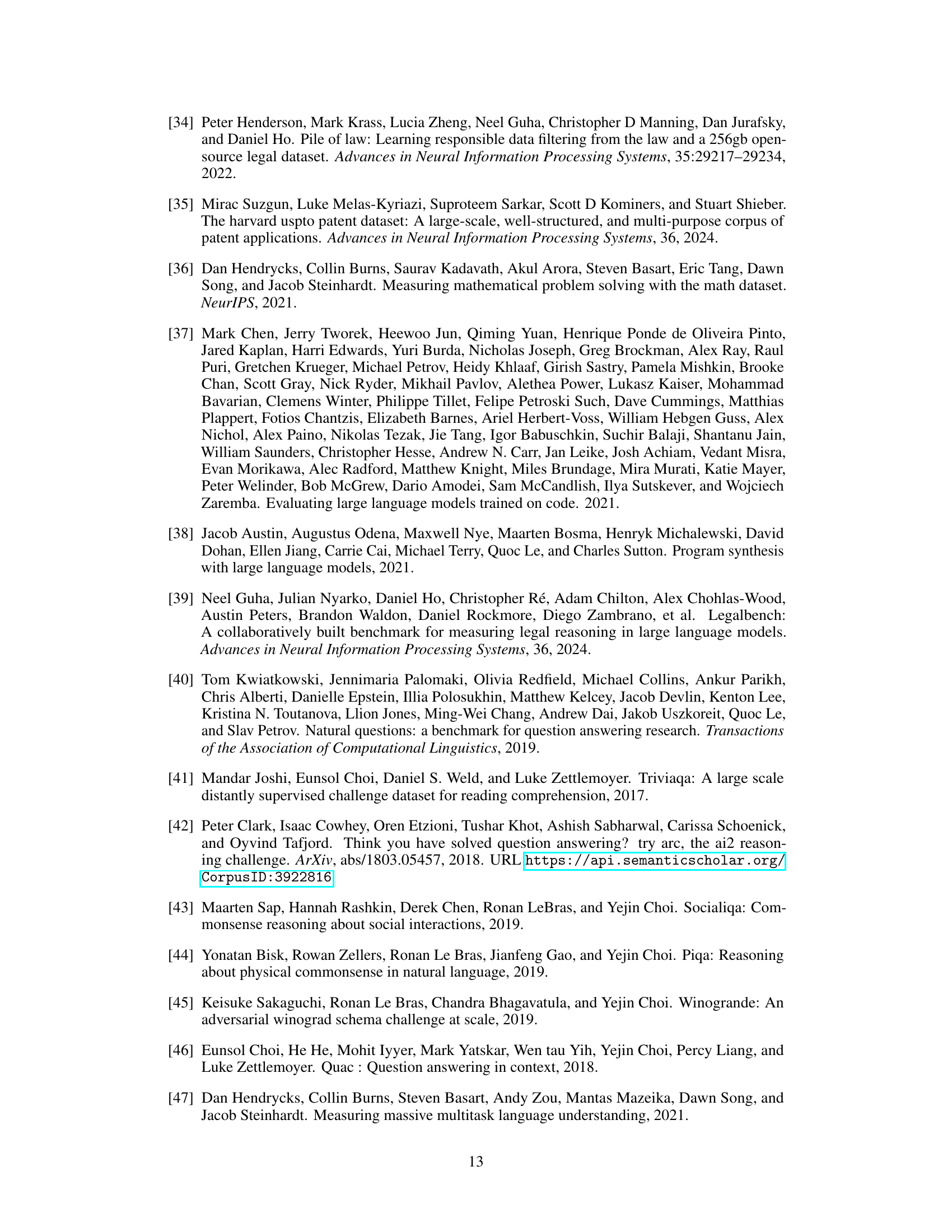

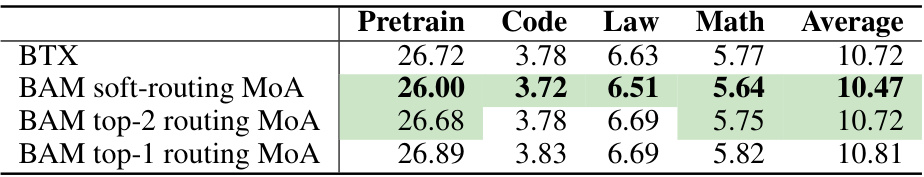

This table presents the perplexity scores achieved by different routing methods for attention experts within the BAM model. The results are compared against the baseline BTX model to show the effectiveness of soft routing in achieving lower perplexity. The various routing methods compared are soft routing (all experts), top-2 routing, and top-1 routing. The perplexity is broken down by domain (Pretrain, Code, Law, Math) and averaged across all domains. The results indicate that soft routing provides superior performance to the baseline.

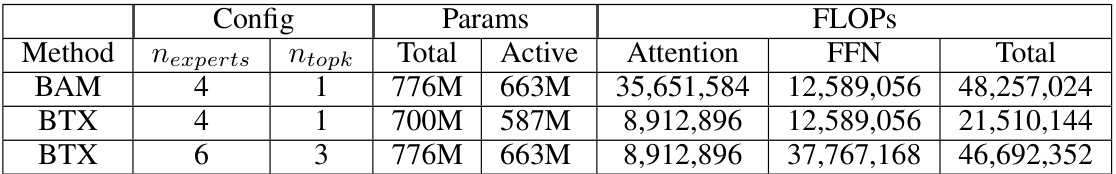

This table compares the computational cost (FLOPs) per token during inference for different model configurations. It compares BAM with its variant that shares key-value parameters (KV) across experts, the standard BTX model, and a modified BTX model with more experts and a different routing strategy. The goal is to demonstrate the trade-offs between model performance and computational efficiency in different approaches.

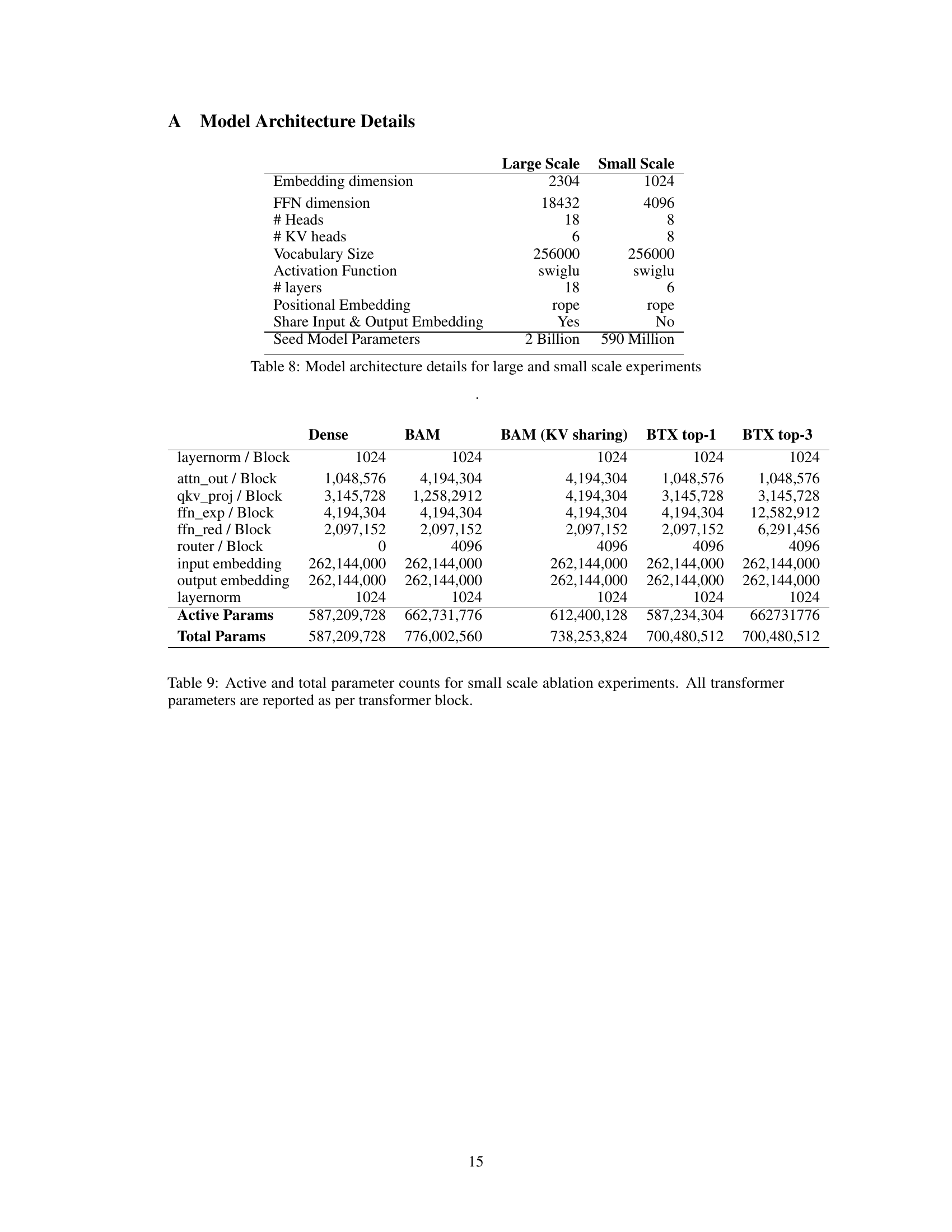

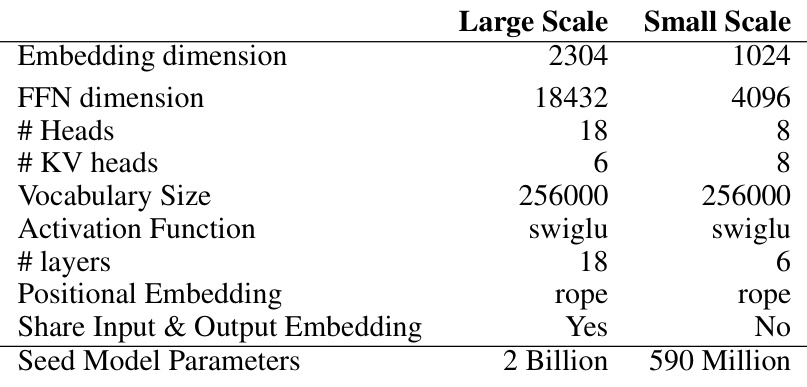

This table details the architectural hyperparameters used for both large and small scale experiments. It shows the embedding dimension, FFN dimension, number of heads, number of key-value heads, vocabulary size, activation function, number of layers, positional embedding type, whether input and output embeddings are shared, and the number of parameters in the seed model used for each experimental setting. These hyperparameters significantly affect the model’s capacity and performance.

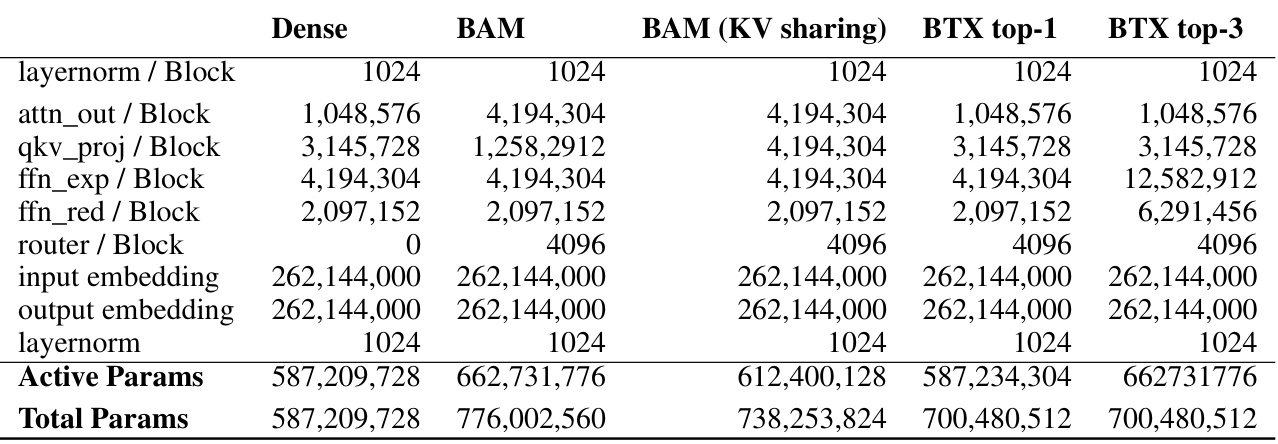

This table details the parameter counts for different model components in small-scale ablation experiments. It shows the number of active and total parameters for each component in the different model architectures: Dense, BAM, BAM (KV sharing), BTX top-1, and BTX top-3. The table helps understand the computational differences between the models. Active parameters refer to the subset of parameters used during inference, while total parameters represent the overall model size.

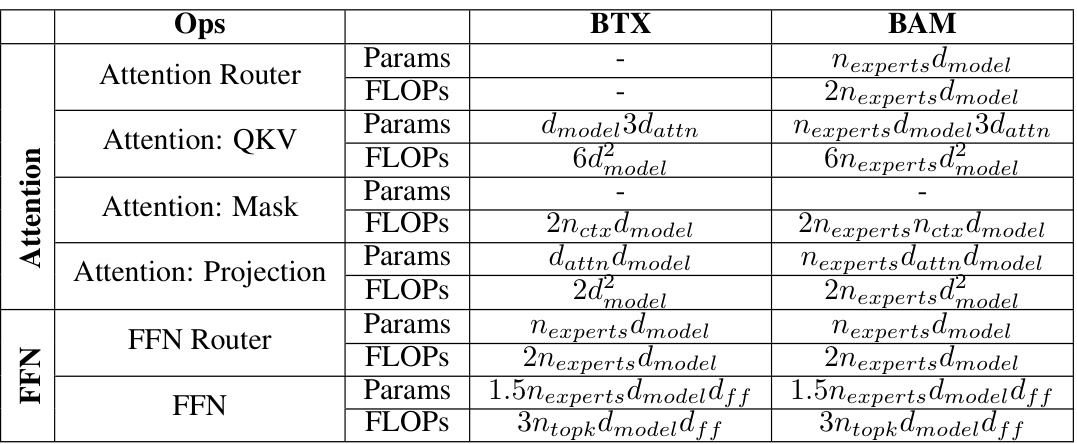

This table provides a detailed breakdown of the parameters and FLOPs (floating point operations) used per token during the inference phase for both the standard BTX (Branch-Train-Mix) model and the proposed BAM (Branch-Attend-Mix) model with KV (Key-Value) experts. It shows the computational cost of each operation within the MoE (Mixture of Experts) layer, including the attention router, attention mechanisms (QKV projection, masking, projection), and the FFN (feed-forward network) router and FFN itself. The table highlights the differences in computational cost between BTX and BAM, particularly due to BAM’s use of soft-gating MoA (Mixture of Attention), which involves all attention experts, resulting in increased FLOPs compared to BTX’s top-k routing mechanism.

Full paper#