TL;DR#

Many real-world machine learning applications face the challenge of limited data and high data acquisition costs. Existing data acquisition methods often assume fully-observed datasets, ignoring the reality of partial observability—where some features or labels are missing. This limitation makes it hard to strategically acquire the most useful data to maximize model performance while minimizing costs.

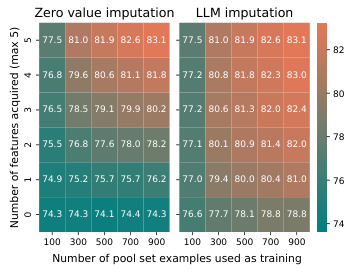

This paper introduces Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA), a novel framework to address this problem. POCA focuses on strategically choosing which features and/or labels to acquire by considering both their potential value to the model and their cost. The authors introduce µPOCA, a Bayesian implementation of POCA that uses Large Language Models (LLMs) to impute (fill in) missing features. This allows for more robust and accurate estimates of uncertainty, leading to better data acquisition decisions. Experiments show that µPOCA significantly improves the generalization of models compared to traditional active learning, especially when data is scarce and costly.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers dealing with limited and costly data in machine learning. It introduces a novel framework, POCA, directly addressing the challenge of partial observability often encountered in real-world applications. The proposed methodology, µPOCA, uses large language models for feature imputation, enabling more efficient data acquisition strategies and improving model generalization. This significantly advances active learning, opening doors for further research in data-scarce scenarios and diverse applications.

Visual Insights#

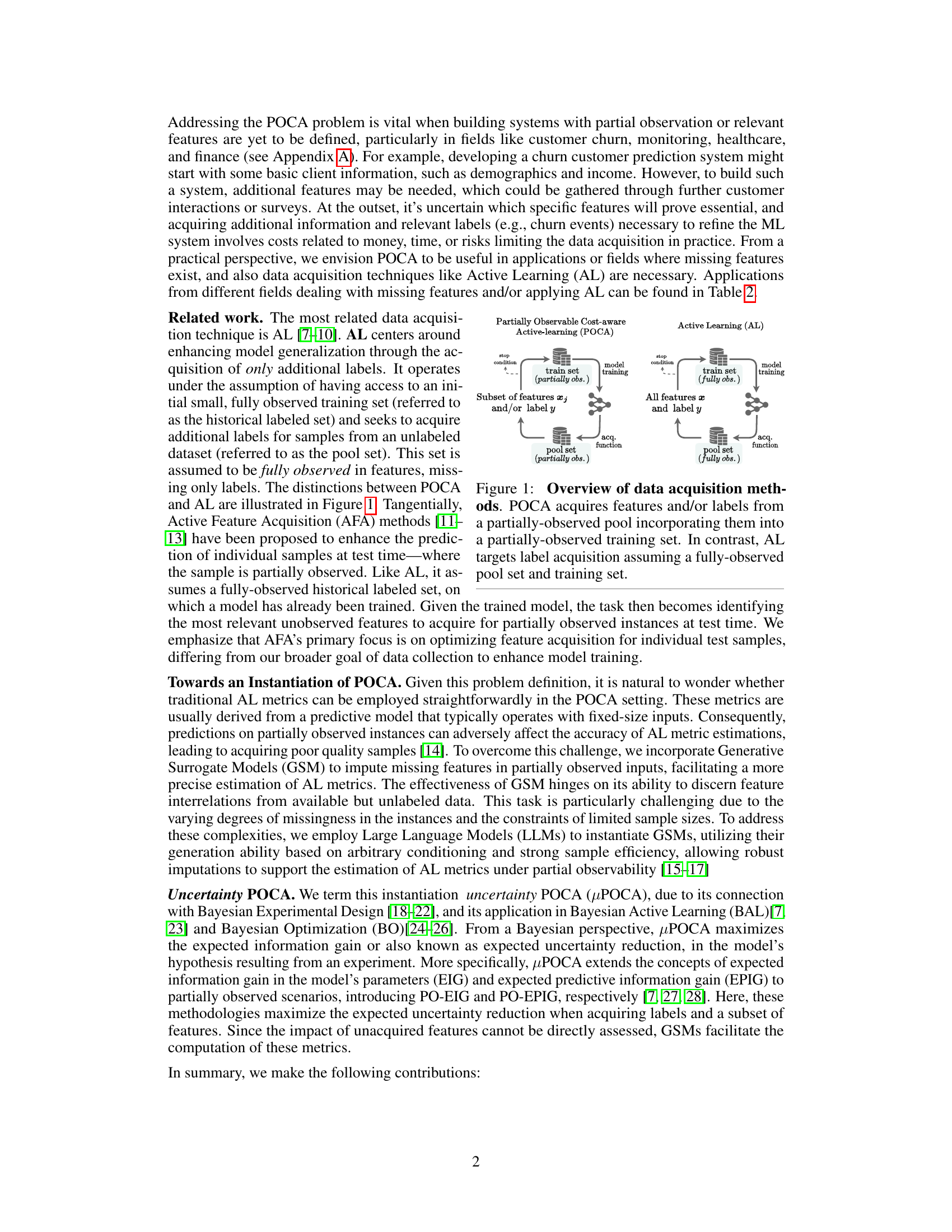

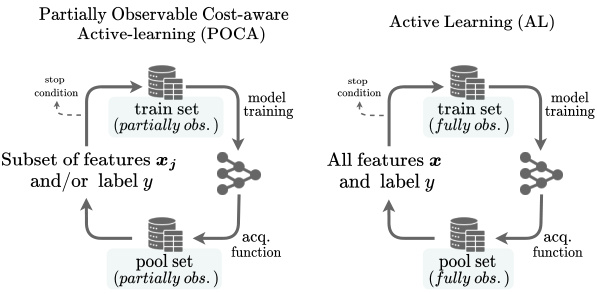

🔼 This figure compares the data acquisition methods of Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) and Active Learning (AL). POCA handles scenarios with partially observed features and labels in both the training and pool sets. It strategically acquires subsets of features and/or labels to enhance model generalization. In contrast, AL operates under the assumption that the pool and training sets are fully observed (all features available) but lack labels. Therefore, AL focuses solely on label acquisition. The figure visually represents the iterative processes of both methods, including model training, data acquisition, and the stop condition.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of data acquisition methods. POCA acquires features and/or labels from a partially-observed pool incorporating them into a partially-observed training set. In contrast, AL targets label acquisition assuming a fully-observed pool set and training set.

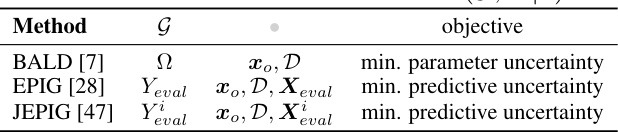

🔼 This table presents a summary of existing Active Learning (AL) methods and their corresponding metrics. Each method aims to maximize information gain by strategically selecting samples from a pool of unlabeled data. The table lists the methods, the random variable representing the generalization capability of the model (G), the conditioning variables, and the objective function of each method. The objectives are either minimizing parameter uncertainty or minimizing predictive uncertainty.

read the caption

Table 1: AL metrics with form of I(G, Y| ).

In-depth insights#

POCA Framework#

The Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) framework offers a novel approach to data acquisition in machine learning, particularly addressing the challenges posed by partially observed data and costly data acquisition. Traditional active learning methods often assume fully observed data, making them unsuitable for real-world scenarios where acquiring complete data is expensive or impractical. POCA tackles this limitation by strategically selecting features and/or labels to acquire, considering their informativeness and associated costs. The framework’s Bayesian nature allows for the incorporation of uncertainty in the acquisition process, ensuring that the most valuable data is prioritized. This is particularly crucial in situations where there is significant cost associated with label and feature acquisition. Furthermore, POCA is designed to be flexible and adaptable, allowing for various instantiations to address specific application needs. The use of Generative Surrogate Models, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), enables the imputation of missing features, further enhancing the effectiveness of the method.

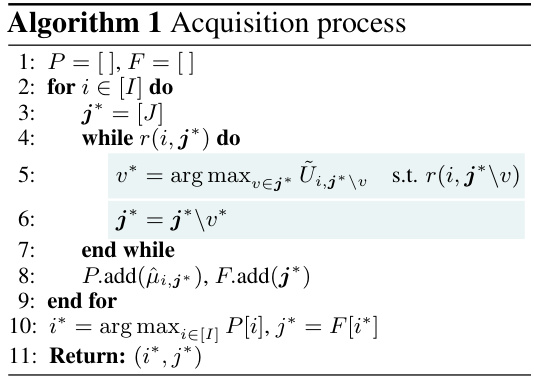

µPOCA Algorithm#

The µPOCA algorithm represents a novel Bayesian approach to Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA). It strategically addresses the challenge of maximizing predictive model performance while minimizing data acquisition costs in scenarios with partially observed features and labels. Unlike traditional Active Learning, which assumes fully observed data, µPOCA leverages Generative Surrogate Models (GSMs), particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), to impute missing features. This imputation allows for a more accurate estimation of uncertainty reduction metrics, guiding the acquisition of the most informative features and labels. µPOCA’s Bayesian framework enables a principled trade-off between uncertainty reduction and acquisition costs, enhancing model generalization in data-scarce and data-costly situations. The algorithm iteratively acquires features and/or labels, updating the model and refining uncertainty estimates using the imputed features, ultimately leading to improved prediction accuracy in settings where complete data is unavailable.

LLMs as GSMs#

The section ‘LLMs as GSMs’ explores the innovative application of Large Language Models (LLMs) as Generative Surrogate Models (GSMs) within the Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) framework. This approach directly addresses the challenge of missing data in real-world machine learning scenarios by leveraging the generative capabilities of LLMs to impute missing features. The authors highlight the suitability of LLMs due to their capacity for learning from partially observed data, sample efficiency, and ability to handle mixed-data types. They argue that LLMs fulfill several key criteria, including generative capability, sample efficiency, and the ability to learn from and handle mixed-data types; all crucial for effective imputation in the context of partially observed data. The choice of LLMs as GSMs is not arbitrary, but rather a deliberate design decision motivated by their demonstrated strengths in few-shot learning and handling mixed data types. This approach significantly enhances traditional Active Learning (AL) methods by enabling more accurate estimations of uncertainty reduction metrics, ultimately leading to improved model generalization with efficient data acquisition. The use of LLMs represents a significant advancement in the field, potentially revolutionizing data acquisition strategies for a wide range of real-world applications.

Uncertainty Metrics#

In the realm of active learning, uncertainty sampling plays a pivotal role, guiding the selection of the most informative data points for labeling. A core component of this strategy hinges on effective uncertainty metrics, which quantify the model’s predictive confidence or uncertainty for each unlabeled instance. The choice of metric significantly influences the learning process, impacting both efficiency and model accuracy. Bayesian approaches often employ metrics derived from the model’s posterior distribution, such as BALD (Bayesian Active Learning by Disagreement), which balances information gain and exploration. Alternatively, frequentist methods might focus on metrics like prediction variance or entropy, reflecting the spread of the predictive distribution. In settings with partial observability, which is the key focus of the research paper, the challenge becomes even more complex. Traditional metrics may fail under the condition of missing features and, therefore, require adaptation. The paper innovates by proposing techniques to impute missing features and modify existing metrics to better suit the partially observed scenario, thus offering a more robust and reliable active learning framework.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) framework are plentiful. Extending POCA to handle more complex data modalities beyond tabular data, such as images and text, would significantly broaden its applicability. Improving the efficiency of the Generative Surrogate Models (GSMs), particularly in handling high-dimensional data, is crucial. Exploring alternative GSMs beyond LLMs and investigating the impact of different GSM architectures on performance is warranted. A deeper theoretical analysis of the uncertainty metrics used in POCA, potentially incorporating concepts from information geometry, could refine the acquisition strategies. Incorporating cost models that reflect the real-world complexities of data acquisition, such as dynamic costs and risks, would enhance practical utility. Finally, empirical validation across a wider range of real-world applications will be critical to demonstrate POCA’s true potential. These future directions will enhance the robustness, efficiency, and impact of POCA.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure compares two data acquisition methods: Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) and Active Learning (AL). POCA addresses scenarios where the training data has partially observed features and/or labels. It strategically acquires additional features and/or labels from a pool of partially observed data points to improve model generalization. In contrast, AL assumes that the pool set is fully observed in terms of features; only labels are missing. It focuses on selecting the most informative data points from the pool set to label and add to the training data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of data acquisition methods. POCA acquires features and/or labels from a partially-observed pool incorporating them into a partially-observed training set. In contrast, AL targets label acquisition assuming a fully-observed pool set and training set.

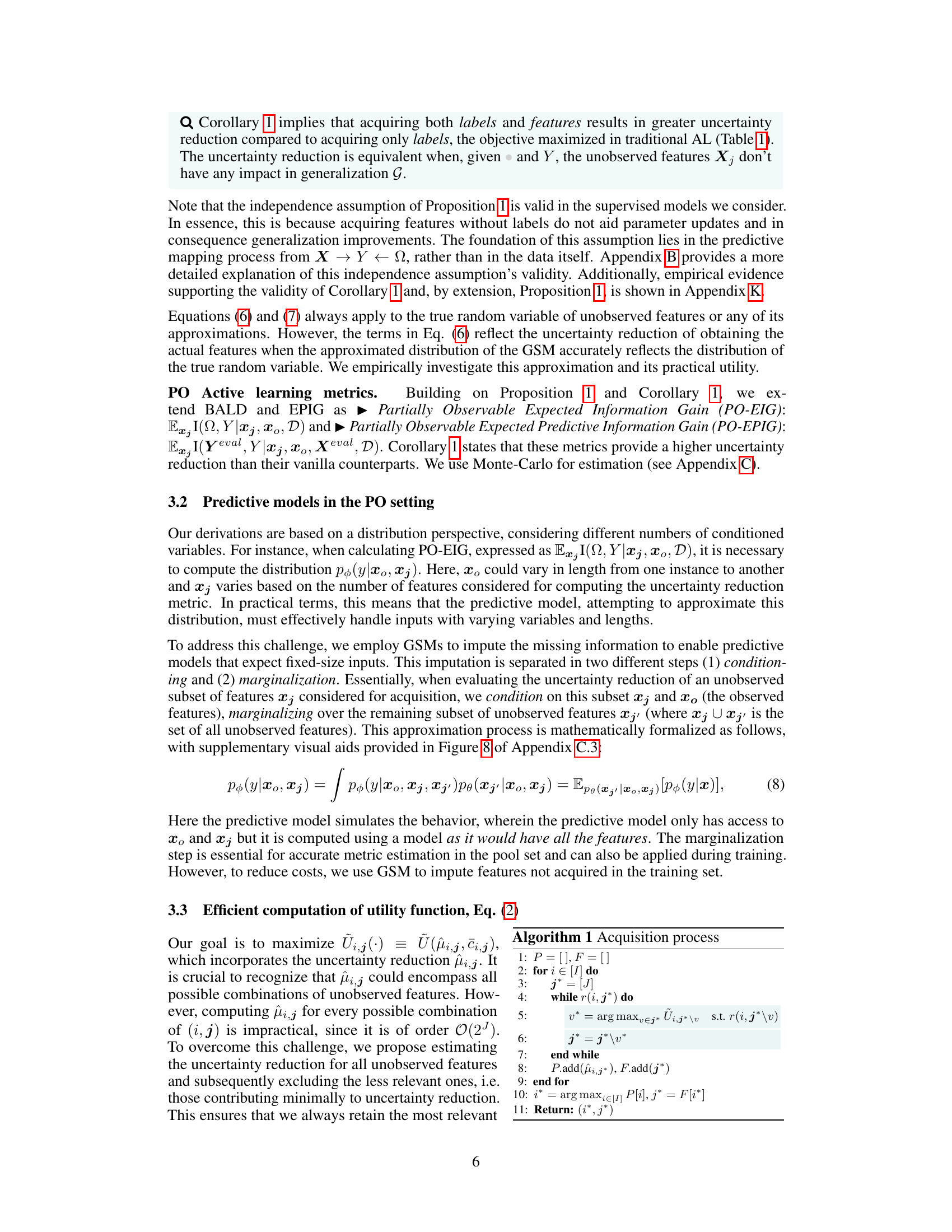

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments comparing the performance of Partially Observable Expected Information Gain (PO-EIG) and Partially Observable Expected Predictive Information Gain (PO-EPIG) against their fully observed counterparts (EIG and EPIG respectively) across multiple datasets. The results demonstrate that PO-EIG and PO-EPIG either outperform or perform comparably to their fully-observed counterparts, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed methods in scenarios with partially observed data.

read the caption

Figure 3: PO-EIG and PO-EPIG computed across diverse datasets - showing they either outperform or match their fully observed counterpart in terms of predictive performance

🔼 The figure displays the performance of Partially Observable Expected Information Gain (PO-EIG) and Partially Observable Expected Predictive Information Gain (PO-EPIG) active learning metrics against their fully observed counterparts (EIG and EPIG) across multiple datasets. The results illustrate that the partially observable metrics either outperform or achieve comparable performance to the fully observed metrics, indicating their effectiveness in scenarios with partially observed data. Each subplot represents a different dataset, showing test accuracy over a range of acquired instances.

read the caption

Figure 3: PO-EIG and PO-EPIG computed across diverse datasets - showing they either outperform or match their fully observed counterpart in terms of predictive performance

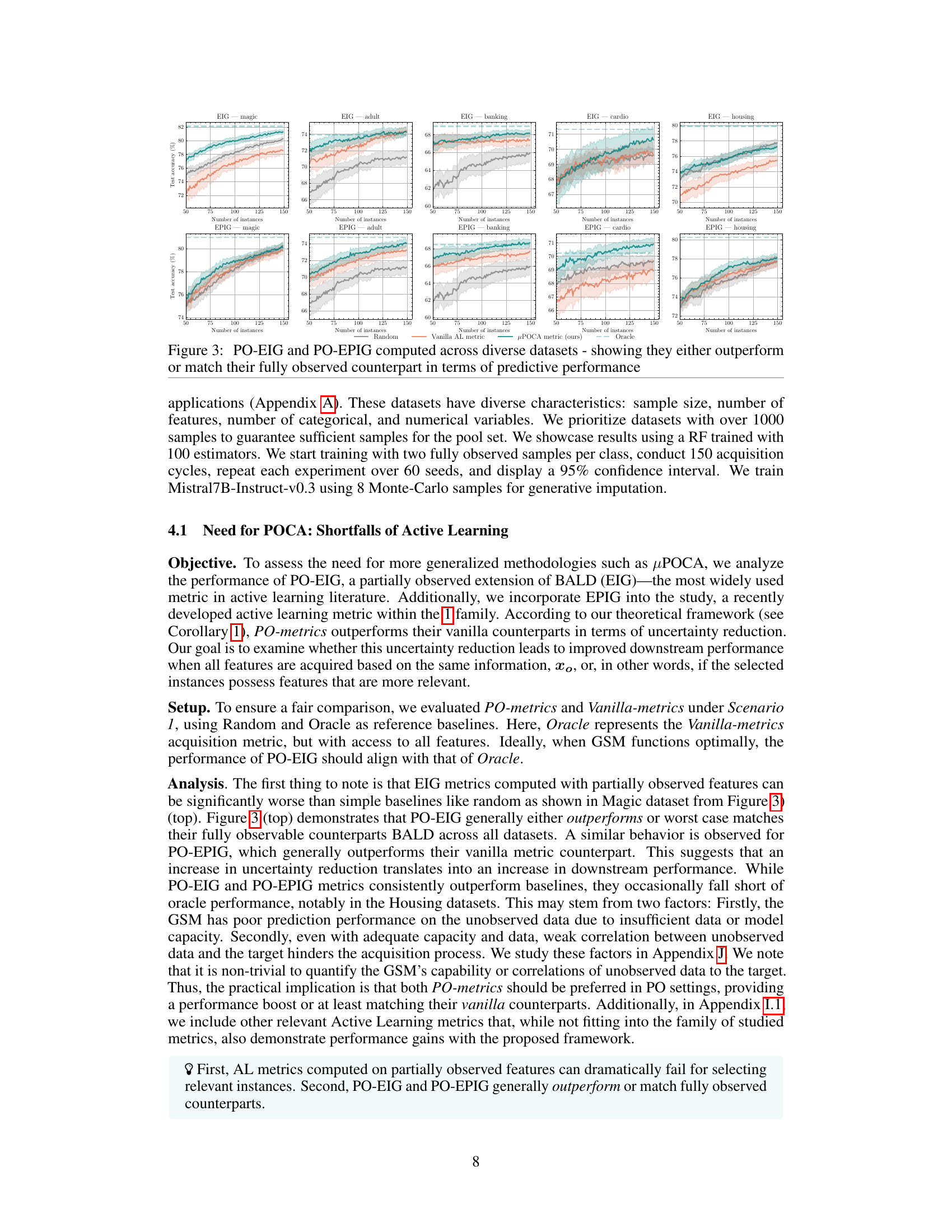

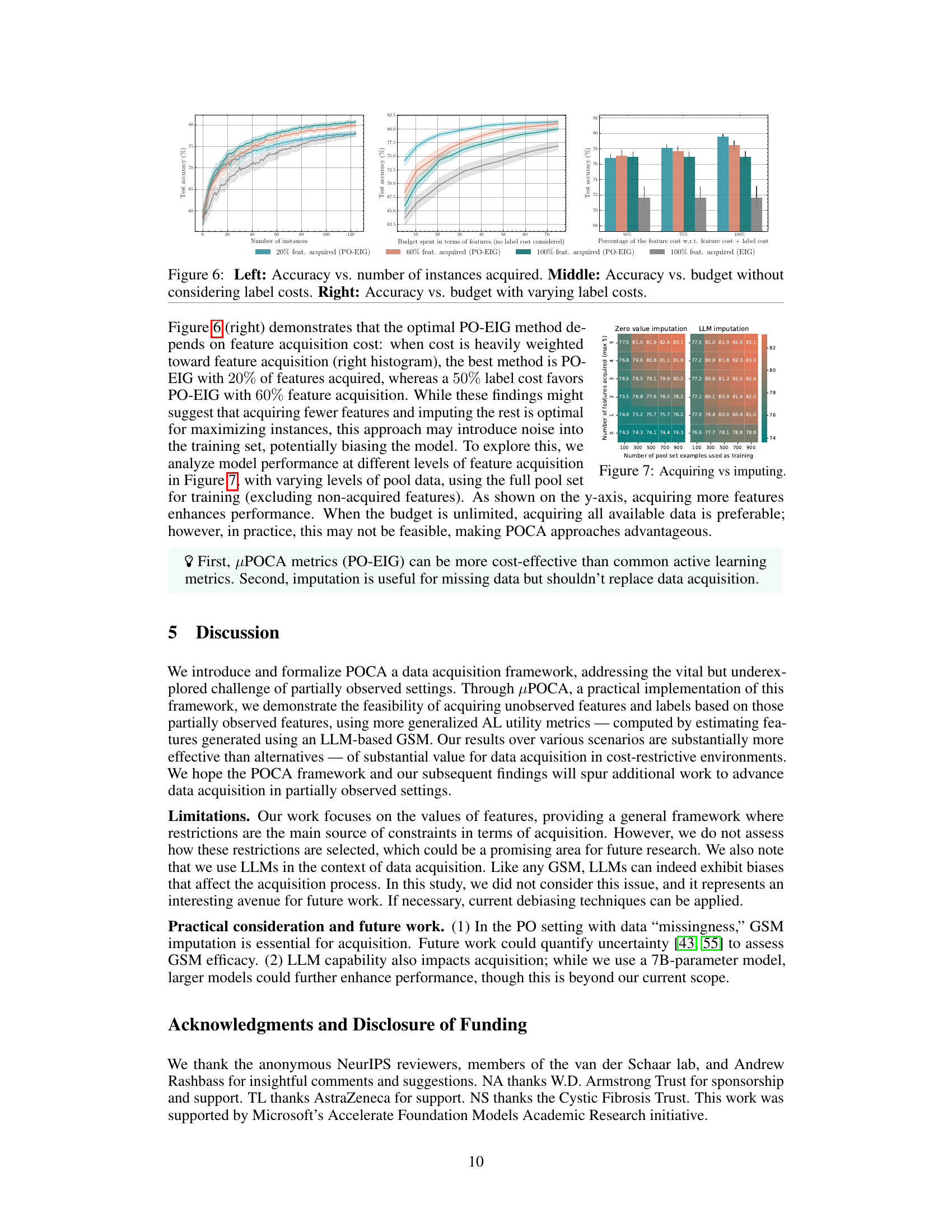

🔼 This figure shows the results of an experiment evaluating the performance of different feature acquisition strategies under various cost constraints. The left panel shows test accuracy plotted against the number of instances acquired, comparing four methods: PO-EIG with 20%, 60%, and 100% feature acquisition, and EIG with 100% feature acquisition. The middle panel illustrates the relationship between test accuracy and the budget spent (excluding label costs) for the same four acquisition methods. Finally, the right panel displays test accuracy as a function of the budget allocated, this time considering varying label costs and a fixed total budget. Each panel provides a visual comparison of how different feature acquisition strategies perform under different cost scenarios, offering insights into the tradeoffs between maximizing accuracy and controlling data acquisition costs.

read the caption

Figure 6: Left: Accuracy vs. number of instances acquired. Middle: Accuracy vs. budget without considering label costs. Right: Accuracy vs. budget with varying label costs.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Partially Observable Expected Information Gain (PO-EIG) and Partially Observable Expected Predictive Information Gain (PO-EPIG) against their fully observed counterparts (EIG and EPIG) across six different datasets. The results demonstrate that PO-EIG and PO-EPIG either outperform or achieve comparable performance to the traditional EIG and EPIG methods in terms of test accuracy, showcasing their effectiveness in partially observed scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 3: PO-EIG and PO-EPIG computed across diverse datasets - showing they either outperform or match their fully observed counterpart in terms of predictive performance

🔼 This figure demonstrates the process of computing the PO-metrics using Monte Carlo (MC) sampling. It shows how the model handles partially observed data by first conditioning on the observed features (xo) and a subset of the unobserved features (xj). Then it marginalizes over the remaining unobserved features (xj’) to get the final estimation of the PO-metric µφ(xo). The figure highlights the steps involved in this process, illustrating how the MC samples are used to approximate the expected uncertainty reduction.

read the caption

Figure 8: Illustrative diagram demonstrating the application of conditioning and marginalization techniques in the estimation of PO-metrics for an arbitrary instance.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core difference between Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) and traditional Active Learning (AL). POCA handles scenarios where the data is partially observed (some features or labels are missing), strategically acquiring additional features and/or labels to improve the model. In contrast, AL operates under the assumption of fully observed features, focusing solely on acquiring additional labels.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of data acquisition methods. POCA acquires features and/or labels from a partially-observed pool incorporating them into a partially-observed training set. In contrast, AL targets label acquisition assuming a fully-observed pool set and training set.

🔼 This figure illustrates Scenario 2, where traditional active learning metrics can be applied. In this scenario, conventional imputation methods are used. The results for this scenario are shown in Figure 12 when all features are acquired for the Active Learning metric. As discussed in the main paper, deterministic imputation does not allow for the acquisition of a subset of features, which is illustrated in Figure 11.

read the caption

Figure 10: Scenario 2.

🔼 This figure illustrates the advantages of µPOCA over traditional active learning (AL) methods in feature selection, particularly in scenarios with partial observability. µPOCA uses generative imputation to estimate the distributions of unobserved features (X2 and X3) while AL uses deterministic methods resulting in a single value. By modeling the uncertainty of these features, µPOCA can identify which features are most relevant and the areas of the feature space where the uncertainty is high, thus making more informed decisions on which features and labels to acquire. In contrast, AL fails to capture the variability of the unobserved features and therefore cannot identify those features which reduce uncertainty and improve model performance.

read the caption

Figure 11: µPOCA in feature selection. With estimates of X2 and X3, µPOCA can identify the relevant feature (X2) and the relevant region. In contrast, AL metrics might use deterministic imputation (green), which does not reveal feature relevance or area of importance under partial observability. This is because a point estimate cannot explore the X2, X3 and how their variability affects the outcome.

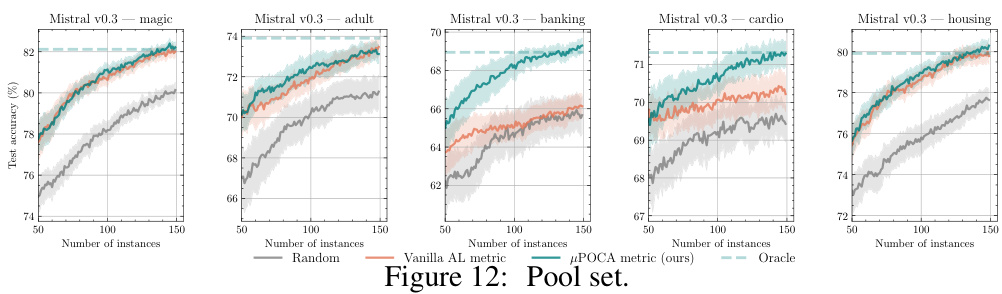

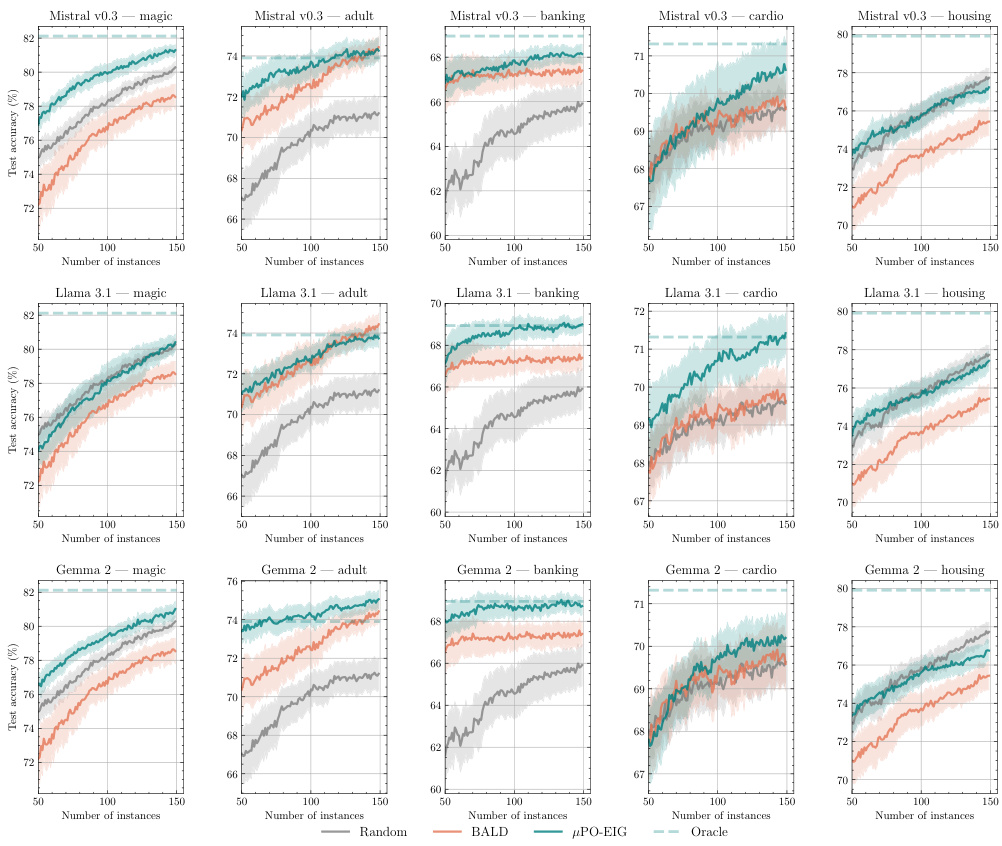

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Vanilla AL metrics, µPOCA metrics (the proposed method), and an oracle baseline across five different datasets (Magic, Adult, Banking, Cardio, and Housing). The x-axis represents the number of instances acquired, while the y-axis shows the test accuracy. The shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals. The figure demonstrates that µPOCA generally outperforms or matches the performance of Vanilla AL metrics, particularly in datasets with complex feature interdependencies and noise.

read the caption

Figure 12: Pool set.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed Partially Observable Expected Information Gain (PO-EIG) and Partially Observable Expected Predictive Information Gain (PO-EPIG) metrics with their fully observed counterparts (EIG and EPIG) across five different datasets. The results show that PO-EIG and PO-EPIG either significantly outperform or perform comparably to the traditional methods across the different datasets, demonstrating their effectiveness in partially observed settings. The number of instances acquired is shown on the x-axis and the test accuracy is shown on the y-axis.

read the caption

Figure 3: PO-EIG and PO-EPIG computed across diverse datasets - showing they either outperform or match their fully observed counterpart in terms of predictive performance.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Partially Observable Expected Information Gain (PO-EIG) and Partially Observable Expected Predictive Information Gain (PO-EPIG) against their fully observed counterparts (BALD and EPIG) across five different datasets. The results show that PO-EIG and PO-EPIG either outperform or perform comparably to their fully observed counterparts, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed methods even in scenarios with partially observed data. The x-axis shows the number of instances acquired, while the y-axis displays the test accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 3: PO-EIG and PO-EPIG computed across diverse datasets - showing they either outperform or match their fully observed counterpart in terms of predictive performance

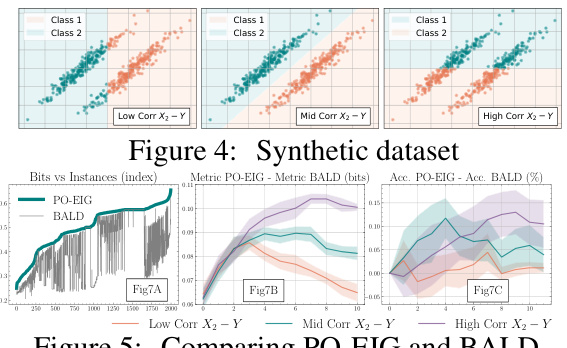

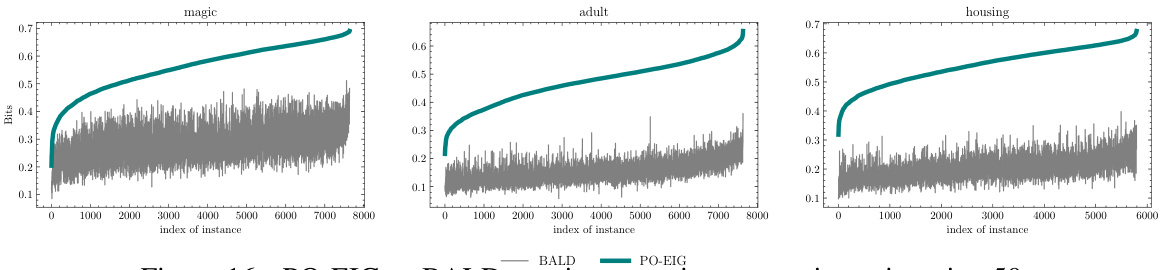

🔼 This figure empirically validates that PO-EIG is always equal to or greater than BALD, consistent with the theoretical insights (Eq. (7)). It also illustrates the gap between PO-EIG and BALD under varying correlations between X2,3 and Y. The gap diminishes towards the acquisition’s end in low correlation scenarios, aligning with Corollary 1. In high correlation scenarios, the gap is larger, indicating that unobserved features significantly impact generalization when strongly correlated with the target variable.

read the caption

Figure 5: Comparing PO-EIG and BALD.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Partially Observable Expected Information Gain (PO-EIG) and Partially Observable Expected Predictive Information Gain (PO-EPIG) against their fully observed counterparts (EIG and EPIG) and random selection across multiple datasets. The results demonstrate that PO-EIG and PO-EPIG either outperform or achieve comparable performance to their fully observed counterparts, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed methods in scenarios with partially observed data. The datasets used exhibit diverse characteristics, ensuring robustness of the results.

read the caption

Figure 3: PO-EIG and PO-EPIG computed across diverse datasets - showing they either outperform or match their fully observed counterpart in terms of predictive performance.

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of uncertainty reduction between PO-EIG and BALD (EIG) at iteration 50 of training, using seed zero. The plots show that PO-EIG consistently achieves equal or greater uncertainty reduction than EIG across different datasets. This empirically validates Corollary 1 and supports the assumption made in Proposition 1, indicating that acquiring both labels and features leads to greater uncertainty reduction than acquiring only labels.

read the caption

Figure 16: PO-EIG vs BALD metrics on various scenarios at iteration 50.

More on tables

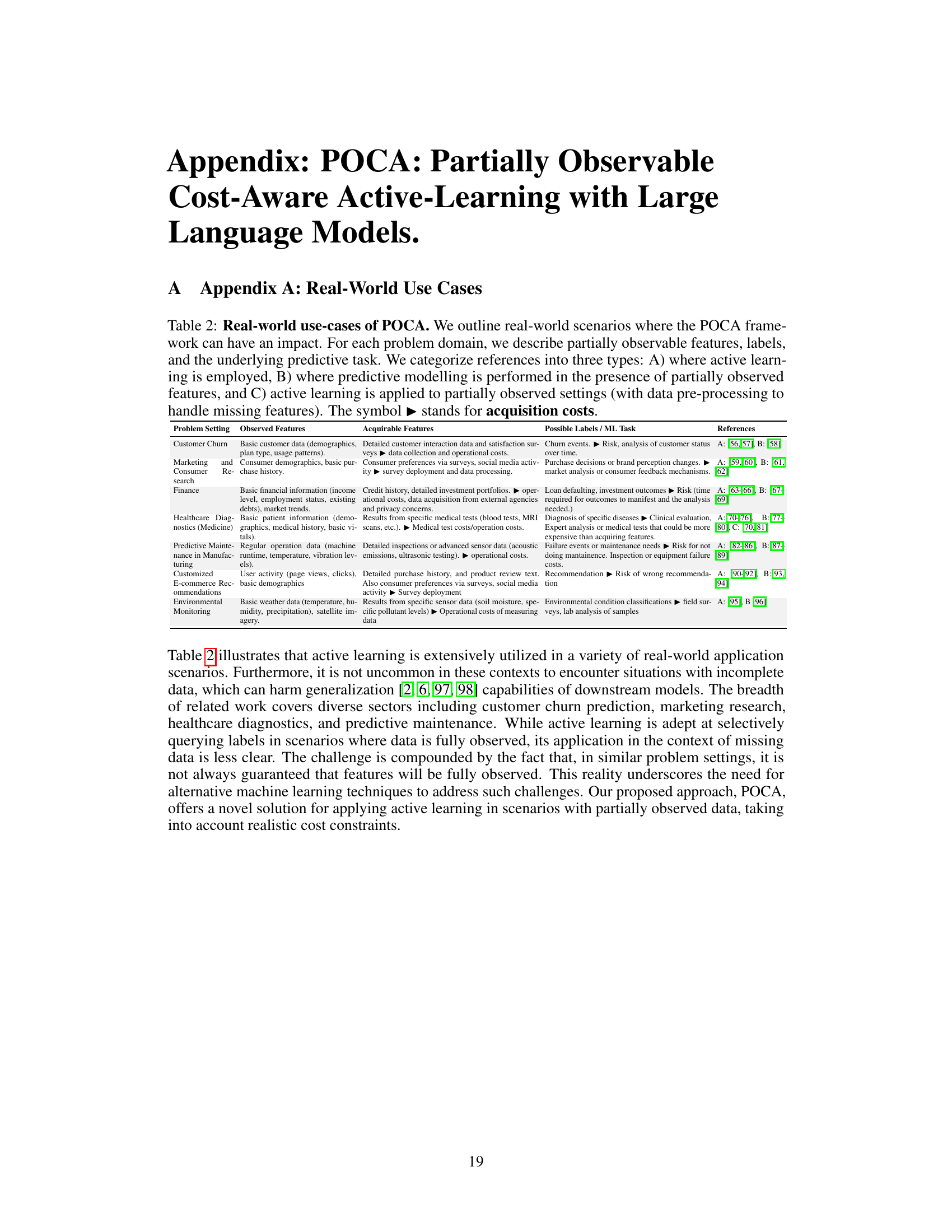

🔼 This table lists several real-world applications where the Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) framework can be applied. For each application domain (e.g., Customer Churn, Healthcare Diagnostics), the table specifies the partially observable features, the labels or the machine learning task performed, the features that could be acquired (with their associated costs), and relevant references to studies illustrating similar problems or approaches.

read the caption

Table 2: Real-world use-cases of POCA. We outline real-world scenarios where the POCA framework can have an impact. For each problem domain, we describe partially observable features, labels, and the underlying predictive task. We categorize references into three types: A) where active learning is employed, B) where predictive modelling is performed in the presence of partially observed features, and C) active learning is applied to partially observed settings (with data pre-processing to handle missing features). The symbol stands for acquisition costs.

🔼 This table presents several real-world applications where the Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) framework could be beneficial. For each application, it lists the problem setting, the observable and acquirable features, the possible labels or machine learning tasks, and relevant references. The table categorizes the references based on whether active learning was used, predictive modeling was done with partially observed features, or active learning was applied to partially observed settings after pre-processing to address missing features.

read the caption

Table 2: Real-world use-cases of POCA. We outline real-world scenarios where the POCA framework can have an impact. For each problem domain, we describe partially observable features, labels, and the underlying predictive task. We categorize references into three types: A) where active learning is employed, B) where predictive modelling is performed in the presence of partially observed features, and C) active learning is applied to partially observed settings (with data pre-processing to handle missing features). The symbol stands for acquisition costs.

🔼 This table shows several real-world applications where the proposed Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) framework can be applied. For each application domain (customer churn, marketing, finance, healthcare, manufacturing, e-commerce, and environmental monitoring), the table specifies the partially observable features and labels, the machine learning task involved, and the types of features that can be acquired. It also categorizes relevant prior work into three types (A, B, and C), each type representing an approach to active learning applied under various data observability conditions.

read the caption

Table 2: Real-world use-cases of POCA. We outline real-world scenarios where the POCA framework can have an impact. For each problem domain, we describe partially observable features, labels, and the underlying predictive task. We categorize references into three types: A) where active learning is employed, B) where predictive modelling is performed in the presence of partially observed features, and C) active learning is applied to partially observed settings (with data pre-processing to handle missing features). The symbol stands for acquisition costs.

🔼 This table presents real-world examples where the Partially Observable Cost-Aware Active Learning (POCA) framework is applicable. For each domain (customer churn, marketing, finance, healthcare, manufacturing, e-commerce, environmental monitoring), the table lists the partially observable features, acquirable features, possible labels or machine learning tasks, and relevant references. The references are categorized into three types: A) active learning is employed; B) predictive modeling with partially observed features; C) active learning is applied to partially observed data with pre-processing. Acquisition costs are also indicated.

read the caption

Table 2: Real-world use-cases of POCA. We outline real-world scenarios where the POCA framework can have an impact. For each problem domain, we describe partially observable features, labels, and the underlying predictive task. We categorize references into three types: A) where active learning is employed, B) where predictive modelling is performed in the presence of partially observed features, and C) active learning is applied to partially observed settings (with data pre-processing to handle missing features). The symbol stands for acquisition costs.

Full paper#