↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world resource allocation scenarios, such as housing and government contracts, necessitate fair auction designs. Existing auction mechanisms prioritize efficiency, often overlooking fairness. This creates challenges in scenarios needing both fair and efficient allocation, especially in dynamic environments with multiple buyer groups and evolving needs. This research addresses the shortcomings of current auction mechanisms by tackling the issue of fair allocation in a dynamic setting.

The authors propose optimal mechanisms that maximize seller revenue while satisfying fairness constraints. This involves a unique recursive approach for dynamic allocation, determining optimal payments and allocations at each round. They also provide efficient approximation schemes to overcome the computational complexity associated with solving these recursive equations. The findings offer valuable insights into fair auction design, contributing practical tools for various domains requiring both efficiency and fairness in allocation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in auction design and fair allocation. It provides a novel framework for dynamic mechanism design with fairness constraints, addressing a significant gap in the existing literature. The efficient approximation scheme offers practical solutions, and the findings open up new research avenues in dynamic fair resource allocation across diverse domains. The work’s implications extend to various fields dealing with resource allocation, particularly those requiring fairness considerations.

Visual Insights#

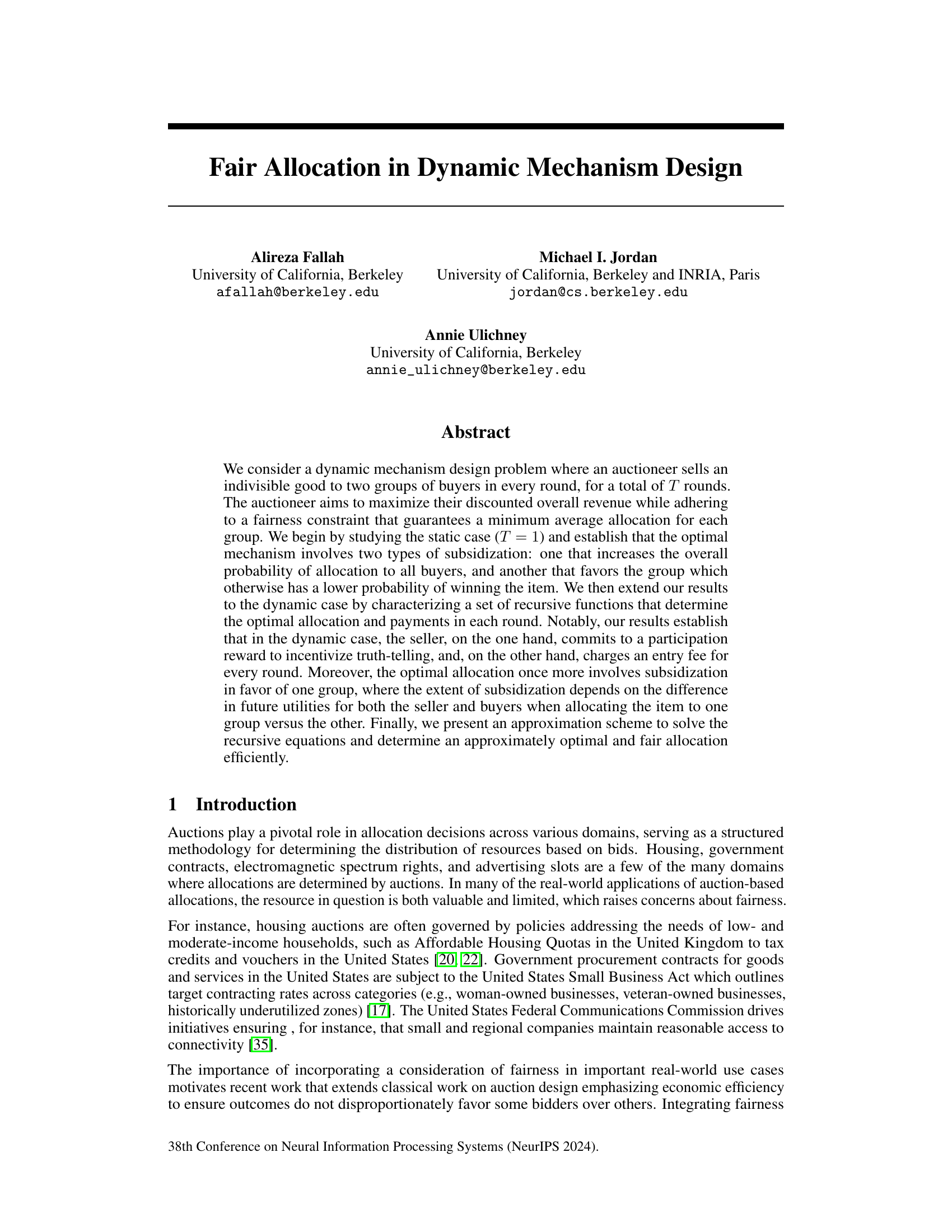

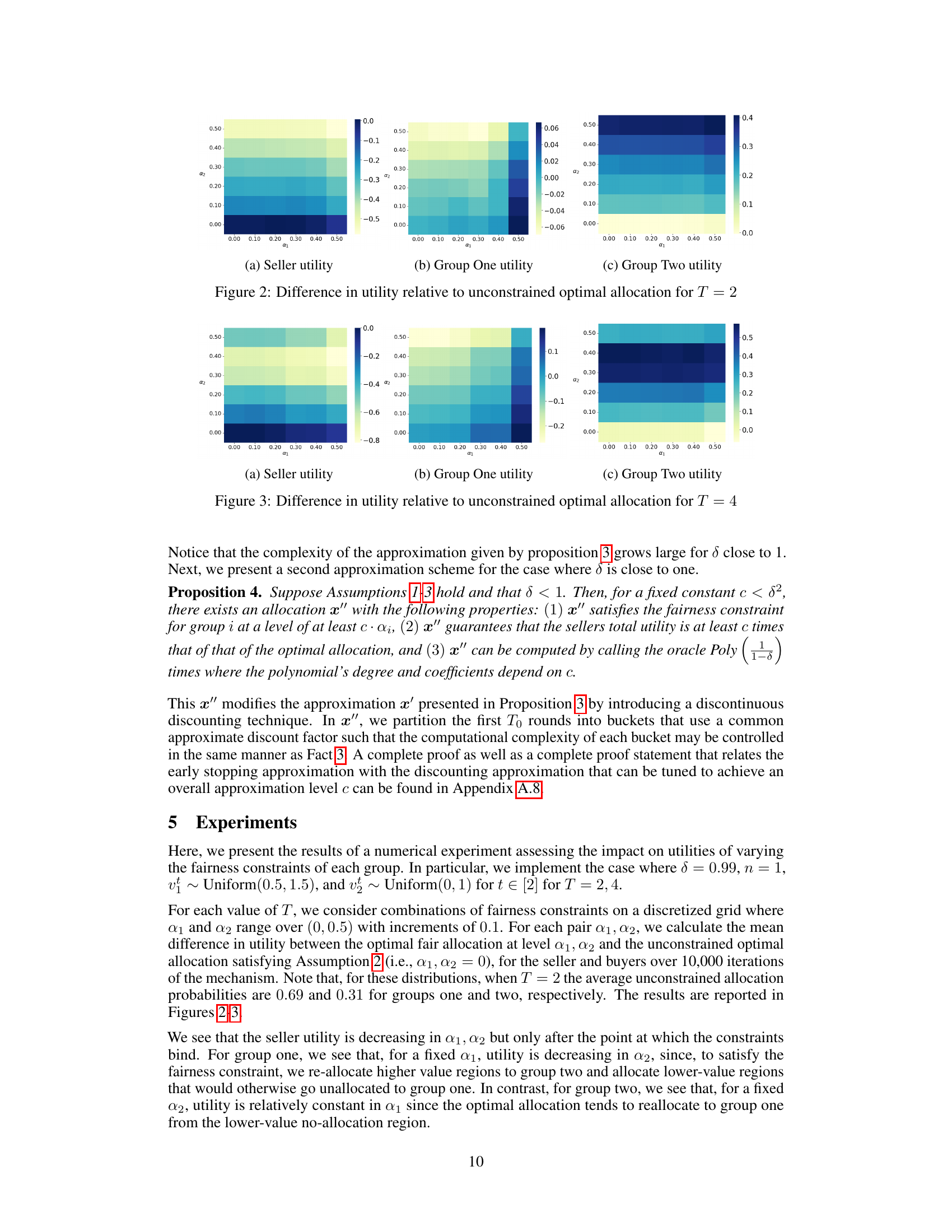

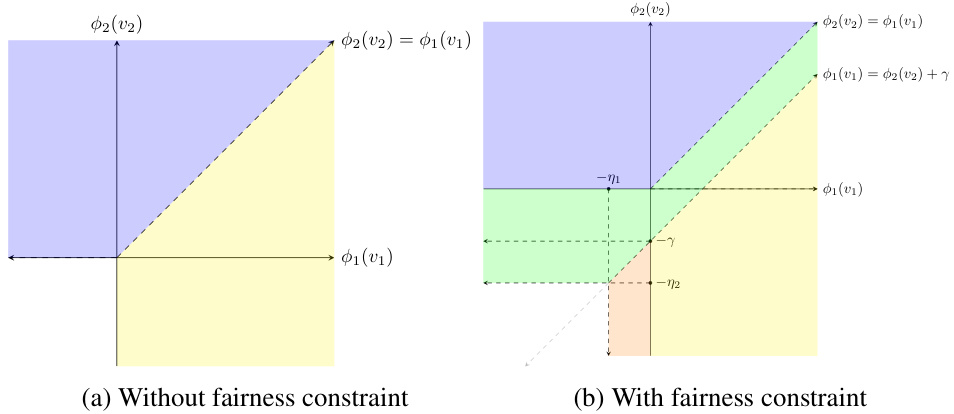

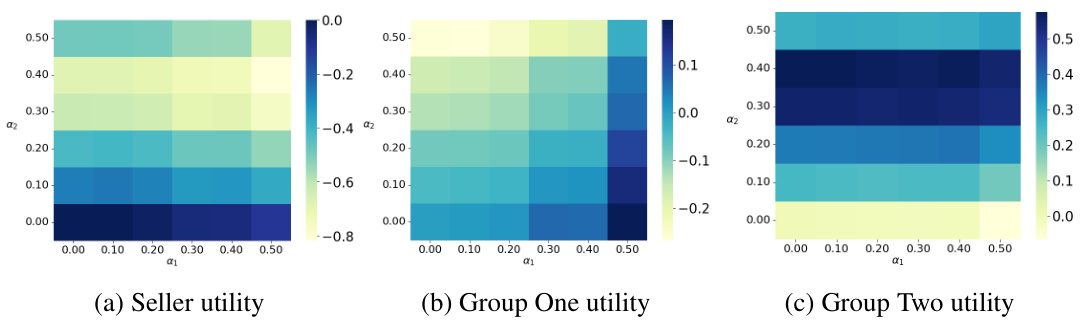

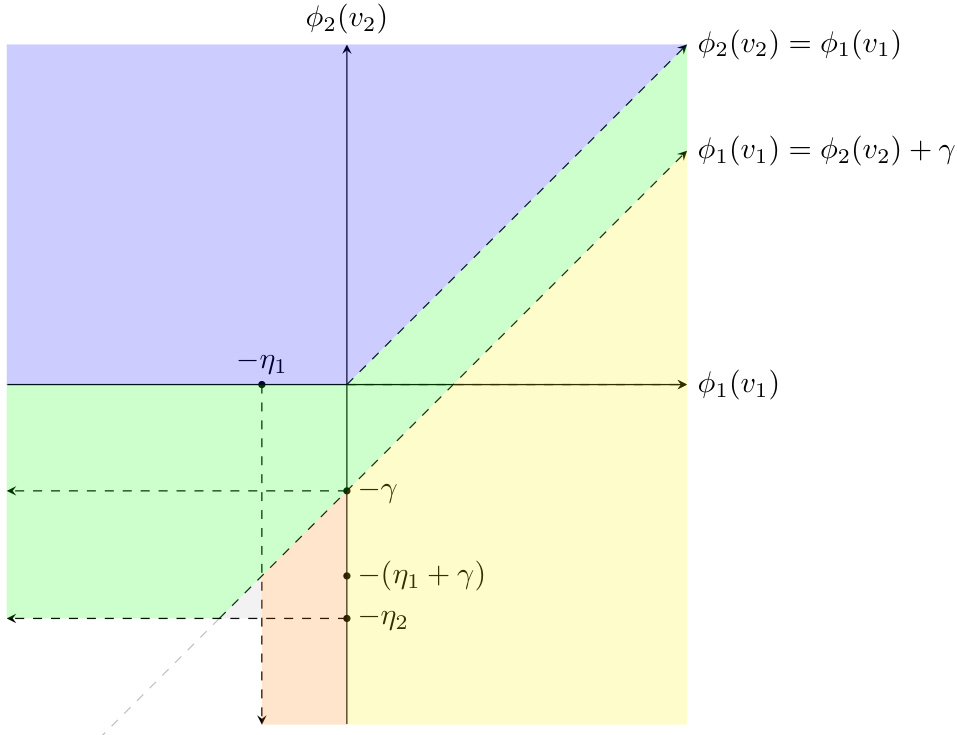

This figure shows a comparison of optimal allocation with and without fairness constraints in the static setting. Panel (a) depicts the optimal allocation without any fairness constraints, showing that the item is allocated to the group with the highest virtual valuation above zero. Panel (b) illustrates how the optimal allocation changes with the addition of fairness constraints. The region where each group receives the item is altered, showcasing the effect of subsidization to favor one group to meet fairness requirements. The extent of this subsidization is governed by γ, which is greater than zero when one group is subsidized, and the parameters η1 and η2, which represent the minimum virtual valuations for each group necessary to ensure fairness.

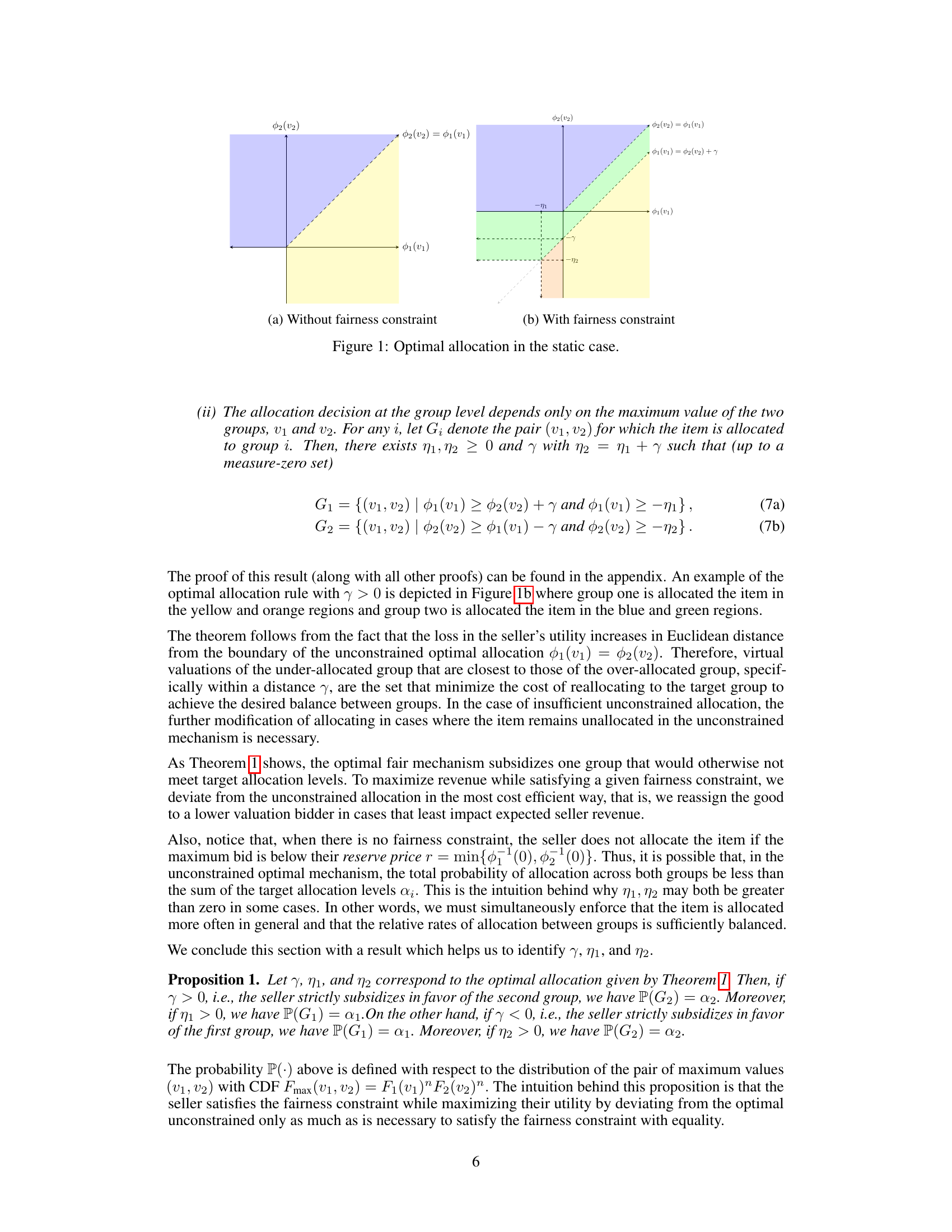

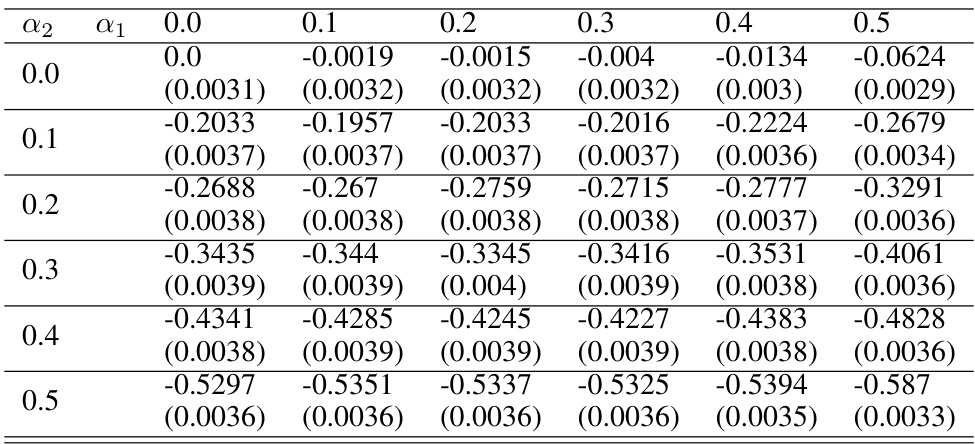

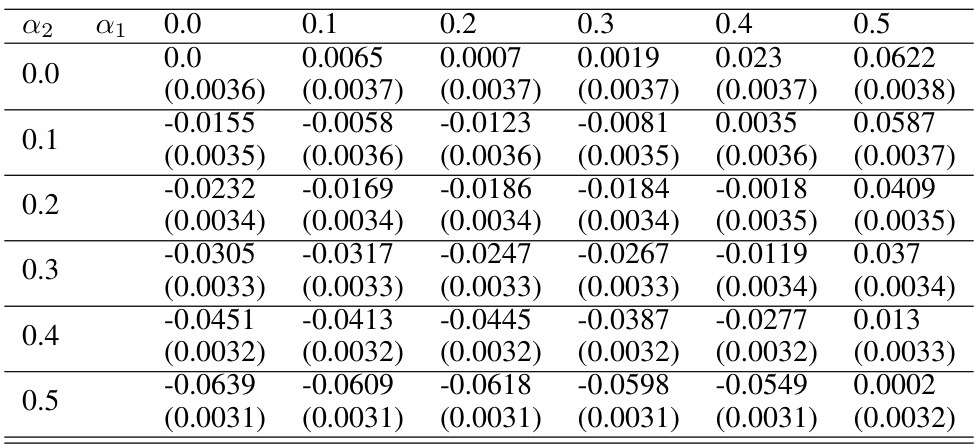

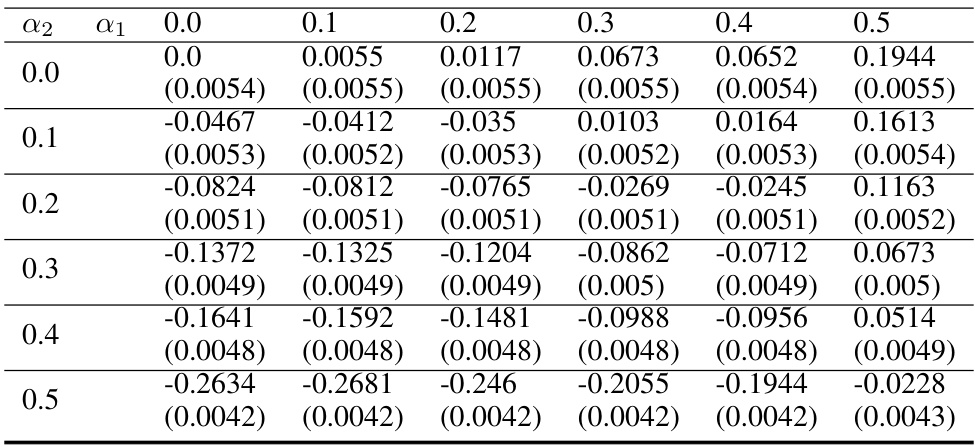

This table presents the difference in seller utility between the optimal fair allocation and the unconstrained optimal allocation for different fairness constraints (α1, α2) when the number of rounds is 2. The values are the mean differences, and standard errors are shown in parentheses.

In-depth insights#

Dynamic Fairness#

Dynamic fairness tackles the challenge of ensuring fairness in settings where allocations or decisions evolve over time. Unlike static fairness, which focuses on a single point in time, dynamic fairness considers the temporal aspect and the cumulative effect of decisions. This is crucial in many real-world scenarios such as resource allocation, where fairness should not be judged on a single instance but rather on an ongoing basis. A key consideration in dynamic fairness is how past decisions influence future ones, which can lead to complex interactions and potentially unfair outcomes. The design of fair mechanisms in dynamic settings requires careful consideration of the temporal dependencies and the long-term impact of decisions. Another aspect is the balance between achieving immediate fairness and ensuring long-term fairness, often requiring a trade-off between the two. Different fairness criteria (e.g., equity, proportionality) might also have varying implications in dynamic settings, making the choice of appropriate criteria context-dependent. Developing effective algorithms and theoretical frameworks for dynamic fairness is a growing area of research with significant practical implications.

Optimal Subsidies#

Optimal subsidy mechanisms in auction design aim to maximize revenue while ensuring fair allocation among competing groups. A key insight is that optimal subsidies are not uniform; they strategically favor groups that would otherwise receive fewer resources, thus achieving a balance between economic efficiency and fairness. This approach involves analyzing the trade-off between revenue maximization and the cost of subsidization, leading to an optimal level of subsidy that depends on several factors, including the buyers’ valuations, the level of fairness required, and the number of rounds in a dynamic setting. The optimal mechanism frequently involves a combination of subsidization to increase overall participation and targeted subsidies favoring specific groups to meet fairness constraints. Dynamic models reveal that optimal subsidies adjust over time based on expected future utilities, creating a complex interplay between present revenue and long-term fairness considerations. Approximation schemes are often necessary to efficiently solve the optimization problem in dynamic settings, striking a balance between computational cost and allocation optimality.

Recursive Allocation#

A recursive allocation strategy, in the context of dynamic mechanism design, would involve solving the allocation problem for each round by working backward from the final round. This approach leverages the principle of optimality, implying that the optimal decision at each round depends only on the current state and the optimal decisions for future rounds. The allocation for each round would become a subproblem within a larger recursive process. The key challenge would lie in efficiently computing the optimal allocation in each subproblem, potentially involving approximations to manage computational complexity. The iterative nature allows for incorporating the impact of past allocations on future rounds, particularly useful for maintaining fairness constraints over time, such as minimum average allocation for different buyer groups. A recursive model could account for evolving buyer valuations and changing market conditions. However, designing and implementing an efficient recursive allocation scheme will require sophisticated mathematical tools and potentially clever approximation algorithms to avoid the curse of dimensionality inherent in dynamic problems.

Approximation Scheme#

The heading ‘Approximation Scheme’ in this research paper likely addresses the computational challenge of solving the recursive equations derived for optimal dynamic allocations. The exact solution’s complexity grows exponentially with the number of auction rounds, making it impractical for real-world applications. Therefore, approximation algorithms are crucial. The paper probably introduces one or more approximation schemes that provide a trade-off between computational efficiency and solution quality. One scheme might guarantee a near-optimal solution within a specified error bound, but with increased computational cost depending on the desired accuracy. Another scheme may offer a constant-factor approximation, significantly reducing computation time but potentially sacrificing some optimality. The analysis of these schemes likely involves proving bounds on their performance, comparing them to the exact solution, and demonstrating their effectiveness via numerical experiments or simulations. The discussion should highlight the advantages and disadvantages of each scheme, considering factors like accuracy, speed, and implementation difficulty, ultimately justifying the chosen scheme’s selection for practical use.

Fairness Tradeoffs#

In exploring fairness tradeoffs within the context of dynamic mechanism design, especially in auction settings, it becomes crucial to acknowledge the inherent tension between maximizing revenue for the auctioneer and ensuring equitable allocation among different groups of buyers. A key consideration is the choice of fairness metric. Proportional fairness, ensuring a minimum average allocation for each group, presents a compelling approach, yet may lead to suboptimal revenue compared to scenarios without fairness constraints. The optimal mechanism under proportional fairness might involve subsidizing one group to meet its minimum allocation, which directly impacts revenue. The extent of this subsidization presents a tradeoff: higher subsidies increase fairness but reduce revenue, and vice-versa. Therefore, finding an equilibrium point that balances fairness and revenue becomes paramount. This balance is further complicated in dynamic settings where strategic behavior and intertemporal considerations significantly affect buyer’s bidding strategies and the auctioneer’s allocation choices. Approximation algorithms are necessary to efficiently navigate the complex computational space of the dynamic model, highlighting the practical challenges in achieving truly optimal and fair results.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares the optimal allocation rule with and without a fairness constraint in the static case (T=1). Panel (a) shows the optimal allocation without fairness constraints, where the item is allocated to the buyer with the highest virtual value above a certain reserve price. Panel (b) shows how this allocation is modified under a fairness constraint that guarantees a minimum average allocation for each group. The fairness constraint leads to subsidization of one group to meet the target allocation level, which modifies the allocation boundary and the region where the item is allocated to each group. The colors represent which group receives the item.

This figure shows two plots that illustrate the optimal allocation rule in the static case (T=1) with and without a fairness constraint. The left plot (a) depicts the unconstrained case, where the item is allocated to the buyer with the highest virtual value. The right plot (b) depicts the optimal allocation when a fairness constraint is imposed which requires a minimum average allocation for each of two groups. The boundary of the optimal allocation region depends on the difference in virtual valuations and a constant gamma, which represent a cost of reallocating to satisfy the fairness constraint. The fairness constraint results in the subsidization of one group to ensure the minimum allocation for both groups, as depicted in the right plot.

This figure shows two diagrams illustrating optimal allocation in a static auction setting (T=1). Diagram (a) depicts the unconstrained optimal allocation, where the item is allocated to the buyer with the highest virtual value (provided it is non-negative). Diagram (b) shows the optimal allocation when a fairness constraint is imposed, mandating a minimum average allocation for each of two buyer groups. The fairness constraint introduces two forms of subsidization: one that increases the overall probability of allocation and another that favors the group that would otherwise have a lower allocation probability. The diagrams show how the optimal allocation regions change under the fairness constraint.

This figure shows two different optimal allocations in the static case. Figure 1a depicts the optimal allocation without a fairness constraint. The item is allocated to the buyer with the highest virtual value, above a certain threshold. Figure 1b depicts the optimal allocation with a fairness constraint. This allocation involves subsidizing one group, allowing allocation to that group even when its maximum virtual value is below the other group’s. The extent of subsidization depends on the difference in future utilities for the seller and buyers when allocating the item to one group versus the other. The two figures highlight how the fairness constraint changes the allocation strategy.

More on tables

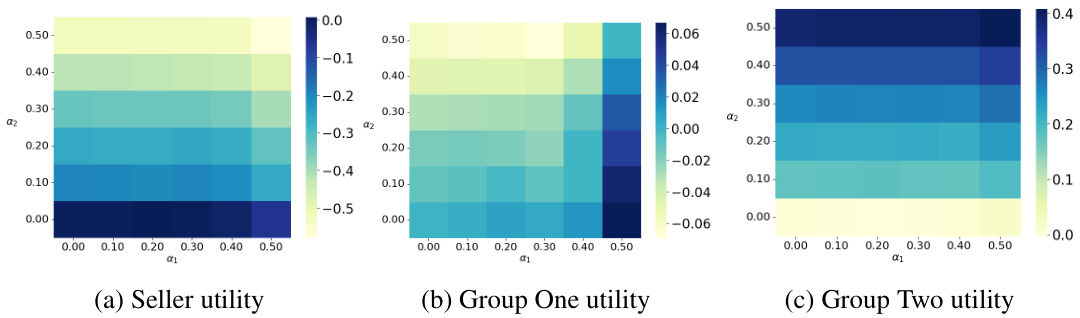

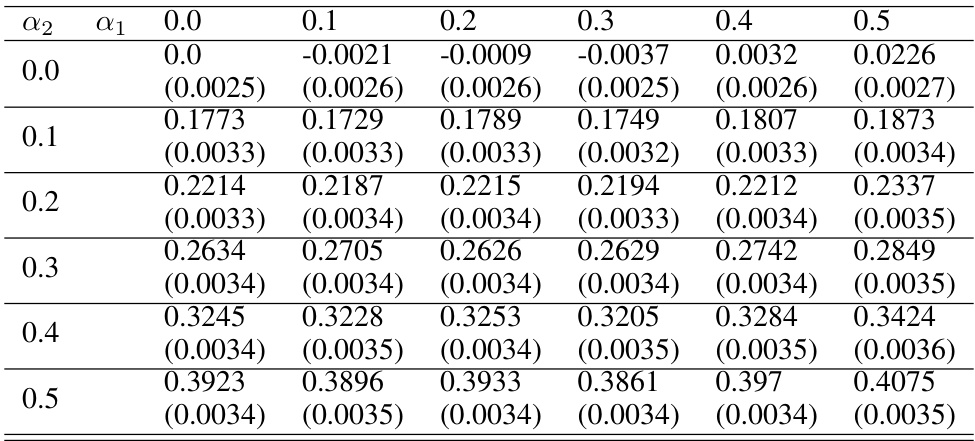

This table shows the difference in group 1’s utility between the optimal fair allocation and the unconstrained optimal allocation for different combinations of fairness constraints (α1, α2) for two groups of buyers over two rounds (T=2). The values represent the mean difference in utility and the numbers in parentheses are the standard errors. A positive value indicates that the fair allocation provides higher utility to group 1 than the unconstrained allocation, while a negative value indicates lower utility.

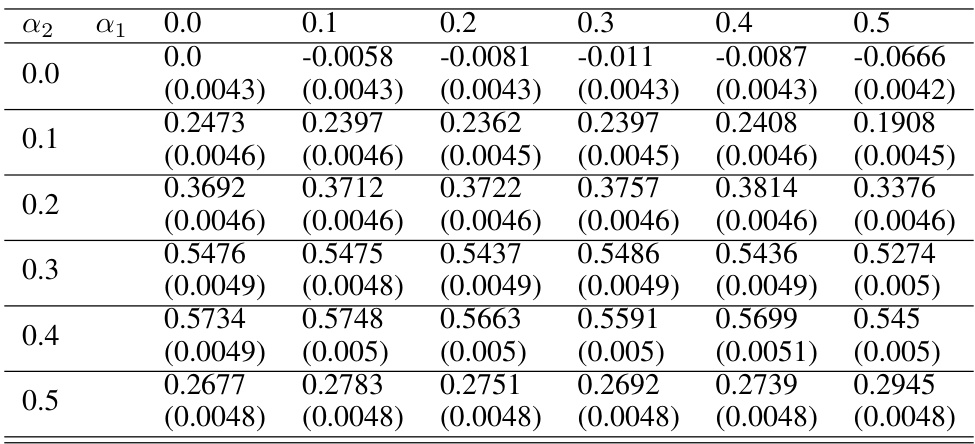

This table displays the difference in group 2’s utility between the optimal fair allocation and the unconstrained optimal allocation for different fairness constraints (α1, α2). The values are calculated for T=2 rounds, with standard errors included to indicate statistical significance.

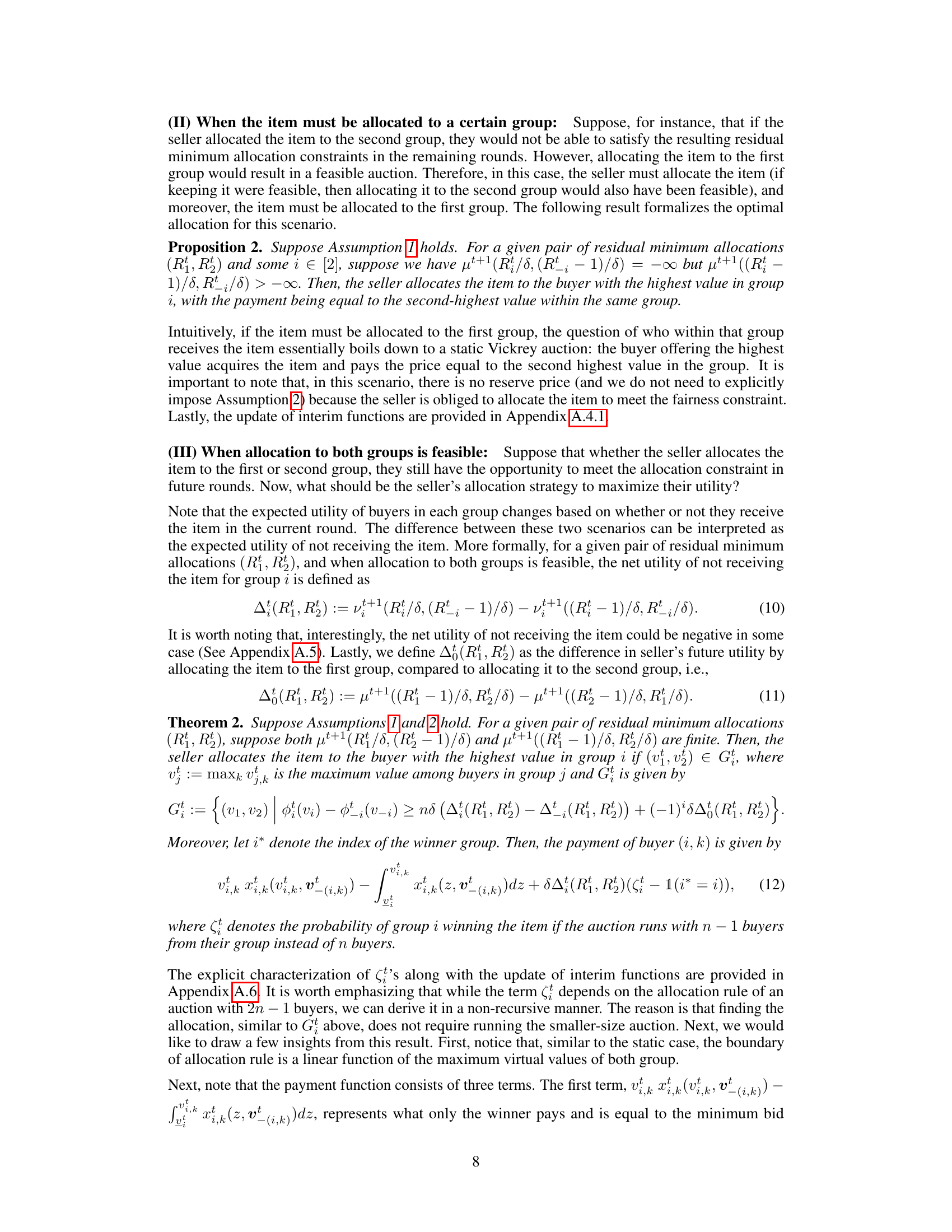

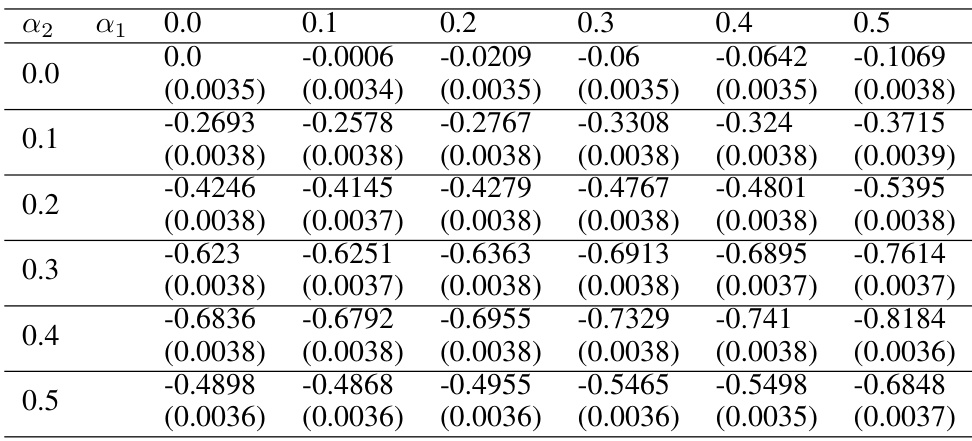

This table shows the difference in seller utility between the optimal fair allocation and the unconstrained optimal allocation for different fairness constraints (α1, α2) when the number of rounds is T=4. The values represent the mean difference, and standard errors are provided in parentheses.

This table presents the difference in group 1’s utility between the optimal fair allocation and the unconstrained optimal allocation for different fairness constraint levels (α1, α2). The results are obtained over 10,000 iterations with a discount factor (δ) of 0.99 and T = 4 rounds. The standard errors are included to show the statistical significance of the results. The table shows how the utility changes with different fairness requirements for each group.

This table presents the difference in utility for group 2 between the optimal fair allocation and the unconstrained optimal allocation for different values of fairness constraints (α1 and α2) when T=4. The standard errors are also provided, indicating the variability in the estimates. The table shows the impact of fairness constraints on the utility of one group, while considering the utility of the other group and the seller.

Full paper#