↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing masked autoencoders (MAE) for video understanding are limited by computational constraints to relatively short videos (16-32 frames). This significantly restricts the model’s ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies crucial for understanding complex actions and events in longer videos. This necessitates the development of methods to efficiently handle longer video sequences and effectively learn temporal dynamics.

This work introduces Long-video masked autoencoders (LVMAE). LVMAE addresses these limitations by employing an adaptive decoder masking strategy. This strategy leverages a jointly trained tokenizer to prioritize important tokens for reconstruction, allowing training on significantly longer video sequences (128 frames). The results demonstrate that LVMAE significantly outperforms state-of-the-art methods on multiple benchmarks, highlighting the importance of long-range temporal context in video understanding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it pushes the boundaries of video understanding by enabling effective training of masked autoencoders on longer video sequences. This addresses a critical limitation of existing methods and opens new avenues for research in long-range video understanding and related applications.

Visual Insights#

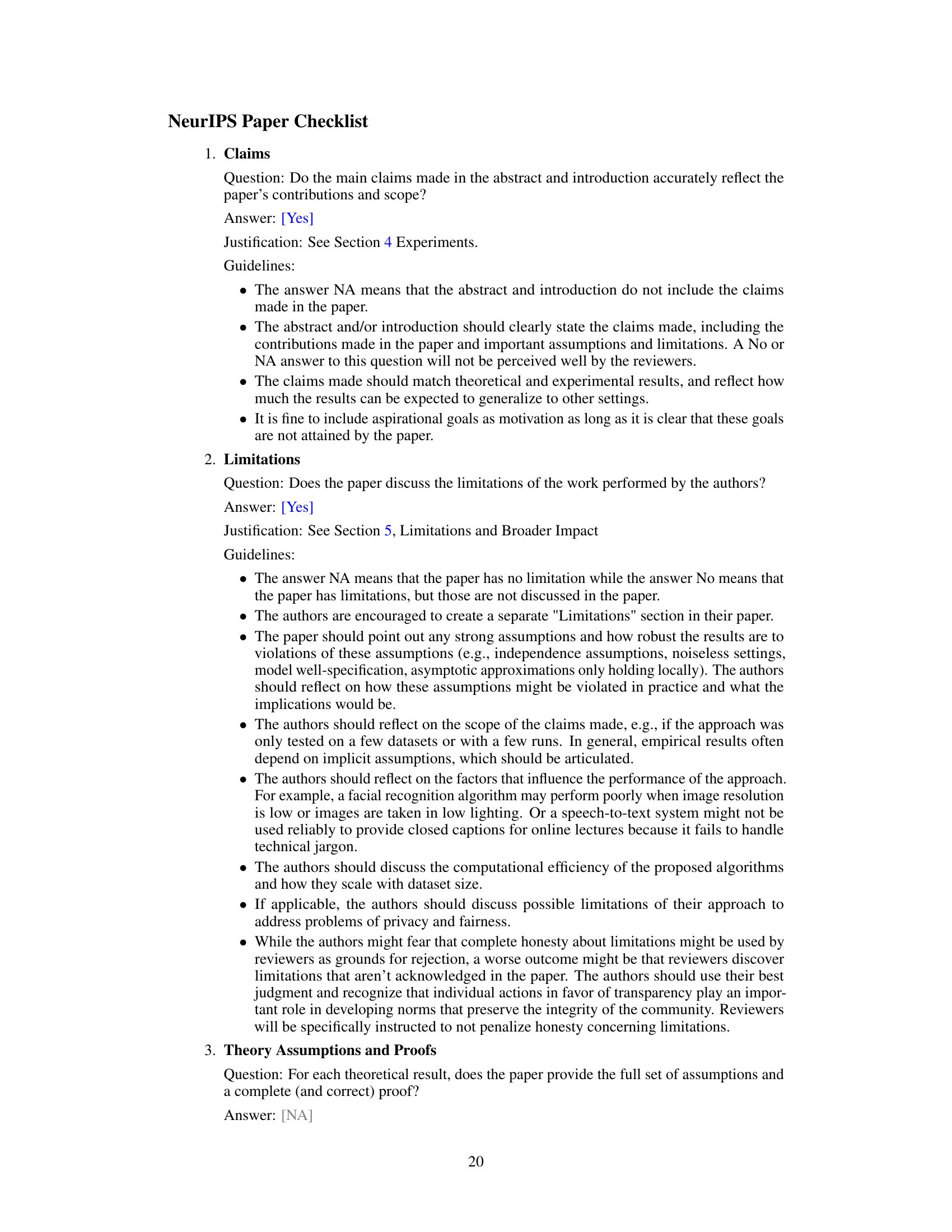

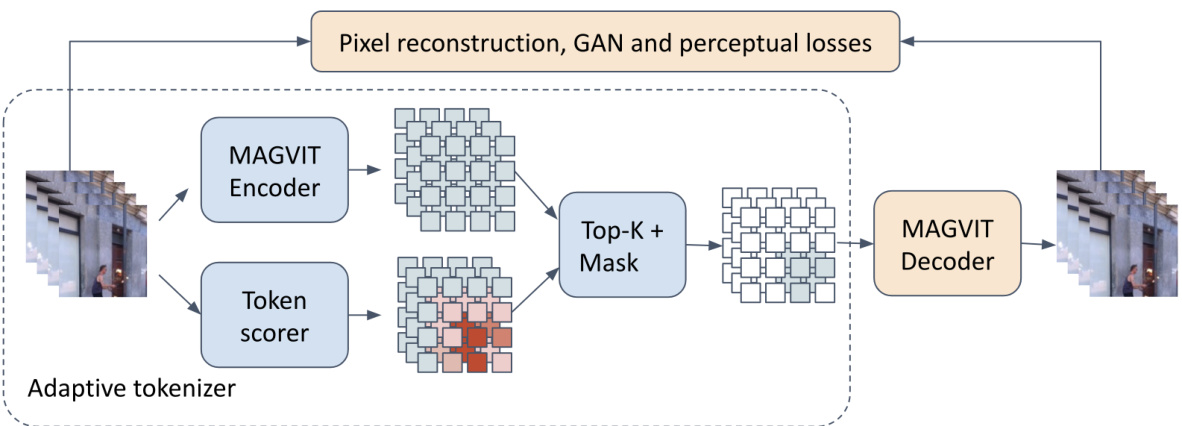

This figure illustrates the proposed long video masked autoencoder (LVMAE) decoder masking strategy. The left panel shows the architecture, highlighting the adaptive tokenizer and importance module used to select the most important tokens for reconstruction. This selective masking enables training on longer video sequences (128 frames). The right panel shows the memory and computational cost (GFLOPs) trade-offs associated with different decoder masking ratios, demonstrating the efficiency of the proposed adaptive strategy for long video training.

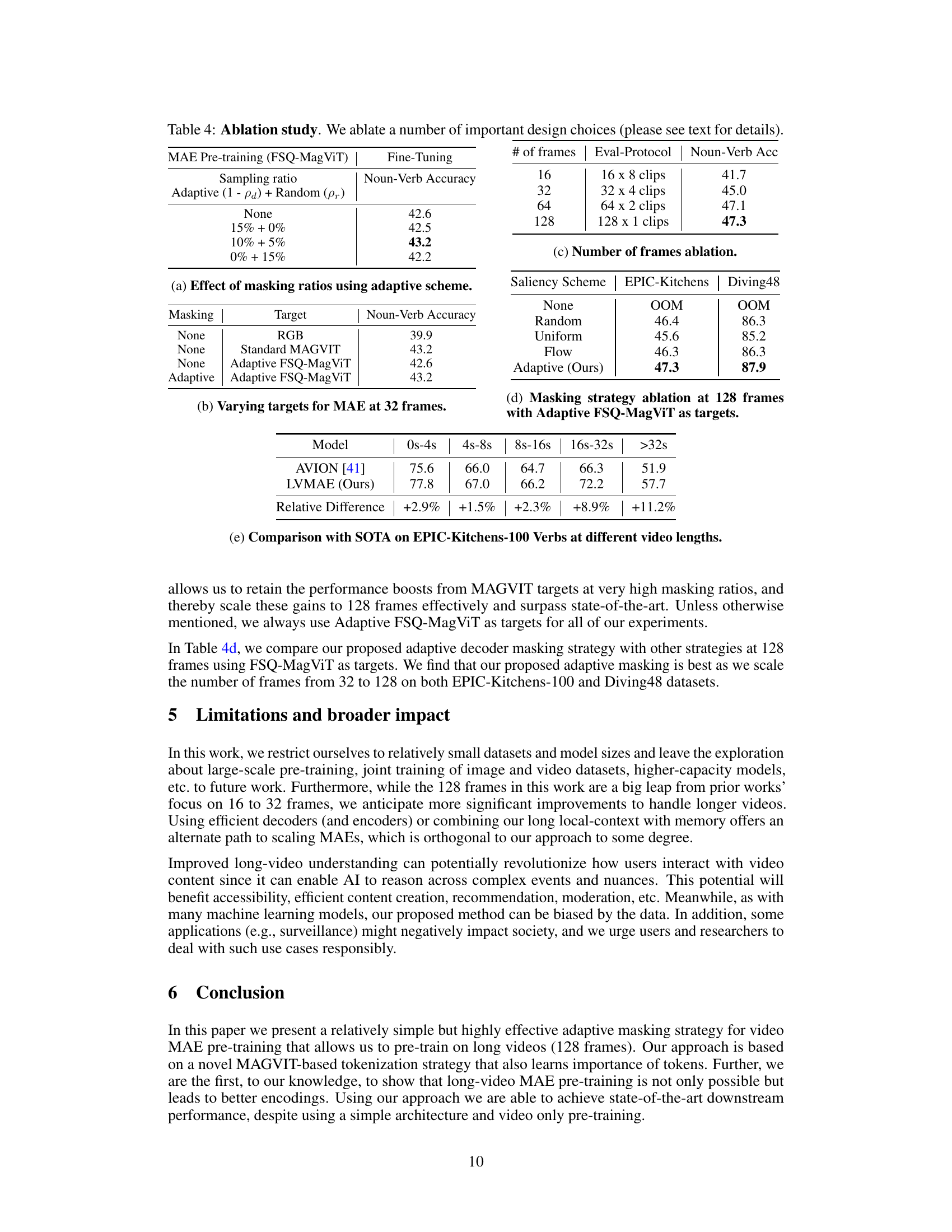

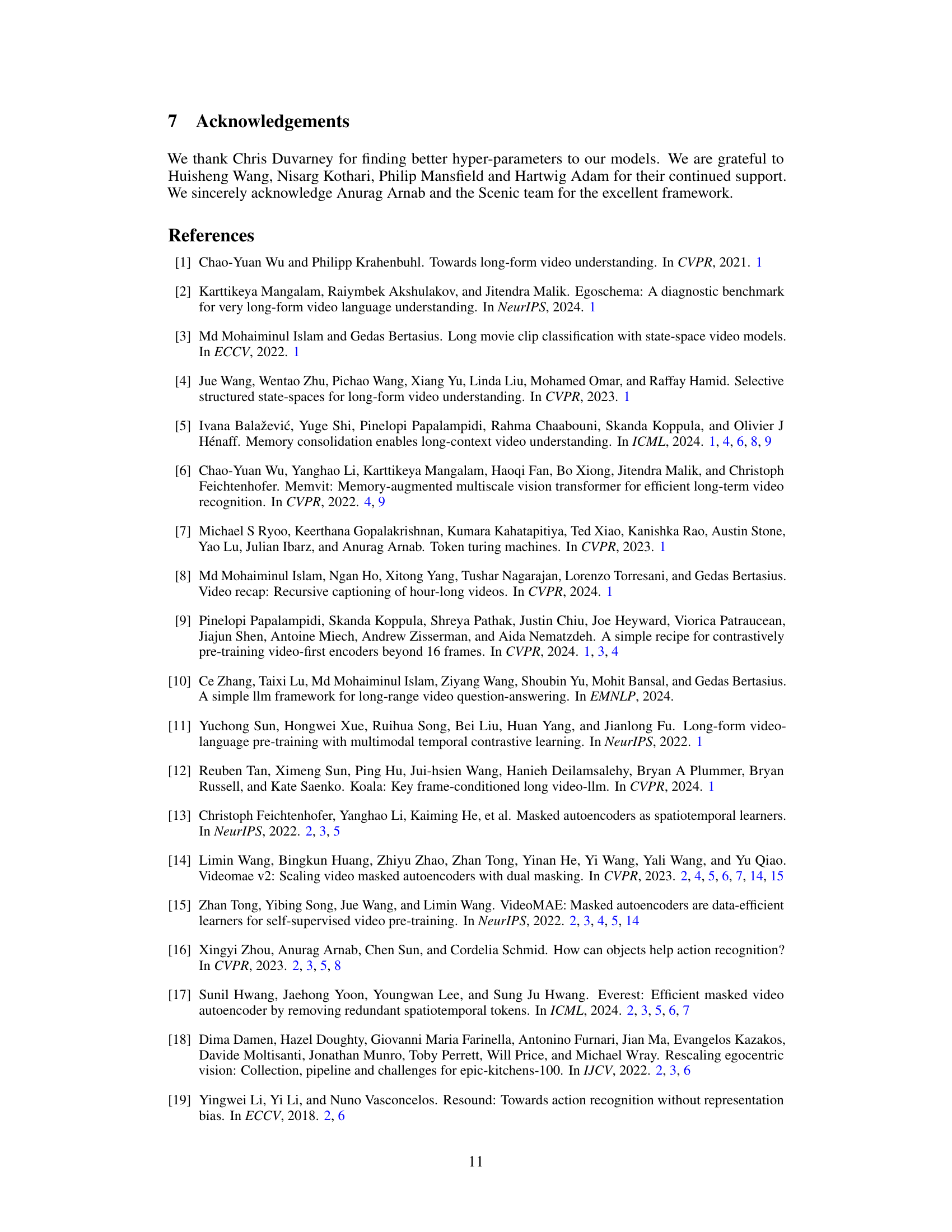

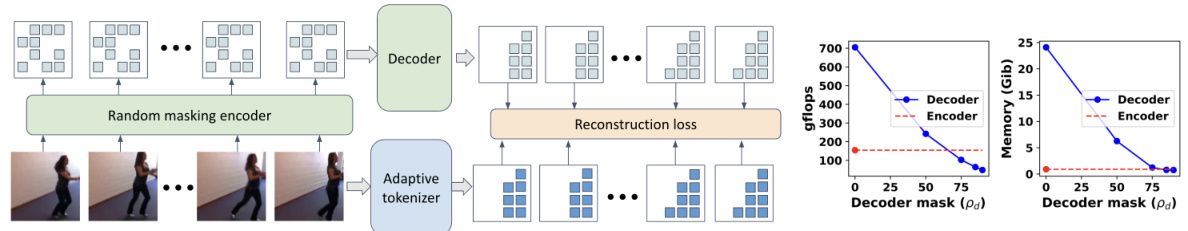

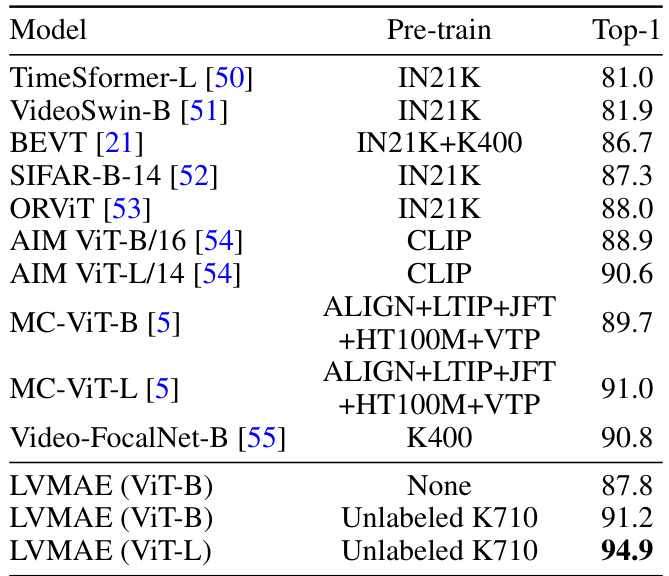

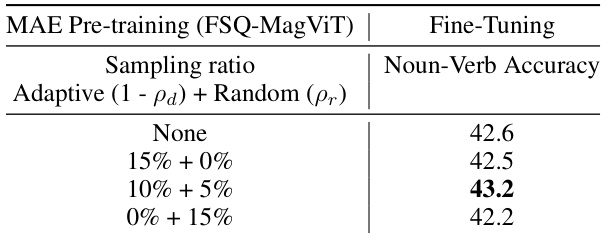

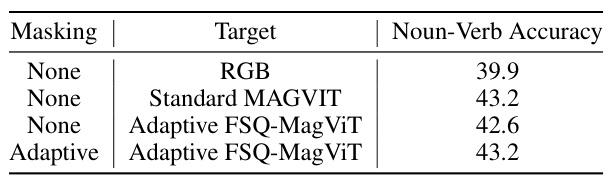

This table compares different decoder masking strategies for short videos (32 frames) on the EK100 dataset. It evaluates the top-1 action classification performance after fine-tuning MAE pre-trained models using either pixel (RGB) or token (FSQ-MagViT) reconstruction targets. A consistent token budget of 15% is used for decoder masking. The results show that the proposed adaptive masking strategy outperforms other methods, including those that leverage uniform, random, or optical flow-based masking.

In-depth insights#

Long-Video MAE#

The concept of “Long-Video MAE” signifies a significant advancement in video masked autoencoders (MAE). Traditional MAE models often struggle with longer video sequences due to computational limitations stemming from the complexity of self-attention mechanisms. Long-Video MAE directly addresses this limitation by developing strategies to efficiently handle the increased temporal length. This might involve techniques like token subsampling, prioritizing informative tokens for reconstruction, or employing more efficient attention mechanisms. The core innovation lies in the ability to learn meaningful representations from significantly longer video clips (e.g., 128 frames) compared to prior approaches. This improved context window likely leads to a more comprehensive understanding of temporal dynamics, benefiting downstream tasks such as action recognition and video understanding. The success of Long-Video MAE hinges on effective masking strategies that balance computational cost and informative content. By selectively reconstructing important tokens, this approach optimizes performance while mitigating memory constraints. Overall, Long-Video MAE represents a powerful step towards building more robust and comprehensive video understanding models that truly capture the richness of temporal information present in long video sequences.

Adaptive Masking#

Adaptive masking, in the context of masked autoencoders for video processing, represents a significant advancement. Instead of randomly or uniformly masking input tokens, adaptive masking strategically selects tokens based on their importance or saliency. This importance is often learned through a joint training process with the model, allowing for more efficient use of computational resources and potentially better model performance. By prioritizing the most informative tokens for reconstruction, adaptive masking addresses the limitations of traditional masking methods, enabling training on significantly longer video sequences while reducing memory and compute requirements. This is crucial for capturing long-range temporal dependencies that are essential for understanding complex video events. The use of quantized tokens further enhances efficiency and performance. The adaptive nature of this technique makes it robust and flexible, capable of adapting to varying video content and complexity. Joint training with a powerful tokenizer ensures the masking strategy is optimized for the specific characteristics of the video data. Overall, adaptive masking is a key innovation, improving the effectiveness and scalability of masked video autoencoders.

Token Prioritization#

Token prioritization in masked video autoencoders (MAE) addresses the computational burden of processing long video sequences. Standard MAE methods struggle with long videos due to the quadratic complexity of self-attention mechanisms in decoding all masked tokens. Prioritizing tokens allows focusing on the most informative parts of the video, reducing the computational load and enabling the training of models on longer sequences. This involves learning a token importance score (saliency) that determines which tokens are crucial for reconstruction. Efficient token selection strategies, like adaptive masking, then use this score to select a subset of tokens for the decoder, considerably decreasing memory usage and computational requirements while maintaining performance. Joint learning of token prioritization and quantization further enhances efficiency and accuracy. The selection of a suitable token importance measure, whether learned or based on motion cues, is key. Ultimately, token prioritization is critical for scaling MAE to longer videos and improving their performance on downstream tasks. It facilitates capturing longer-range temporal dependencies vital for understanding complex video events.

Empirical Results#

An ‘Empirical Results’ section would ideally present a detailed analysis of experimental findings, going beyond simply reporting metrics. It should begin by clearly stating the experimental setup, including datasets used, evaluation metrics, and any pre-processing steps. The presentation of results should be structured and methodical, perhaps using tables and figures to visualize key performance indicators. Crucially, the discussion should focus on interpreting the results in relation to the research questions and hypotheses. This involves comparing different model variants or approaches, analyzing their strengths and weaknesses, and highlighting statistically significant differences. A key strength is the inclusion of ablation studies, which systematically isolate the effects of individual components to demonstrate their contribution to overall performance. Furthermore, a robust analysis would discuss any unexpected or counterintuitive results, exploring potential causes and limitations. Finally, a thorough section would place the findings in the broader context of existing research, comparing performance to state-of-the-art methods and highlighting the novelty and impact of the presented work. The overall goal is to provide clear, convincing evidence supporting the claims made in the paper.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several key areas. Scaling to even longer video sequences (beyond 128 frames) is crucial for more comprehensive action understanding. This will require further investigation into more efficient attention mechanisms or alternative architectural designs. Incorporating additional modalities, such as audio or text, could significantly enhance the model’s ability to capture richer contextual information. A promising avenue is exploring methods to jointly learn representations from these multiple sources. The development of more robust and generalizable adaptive masking strategies is also critical, potentially leveraging advancements in saliency detection or self-attention techniques. Finally, understanding the limitations of video-only pretraining and exploring the benefits of multimodal training, especially video-text pairs, could yield significant performance gains. This should encompass both theoretical analysis and careful empirical evaluation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

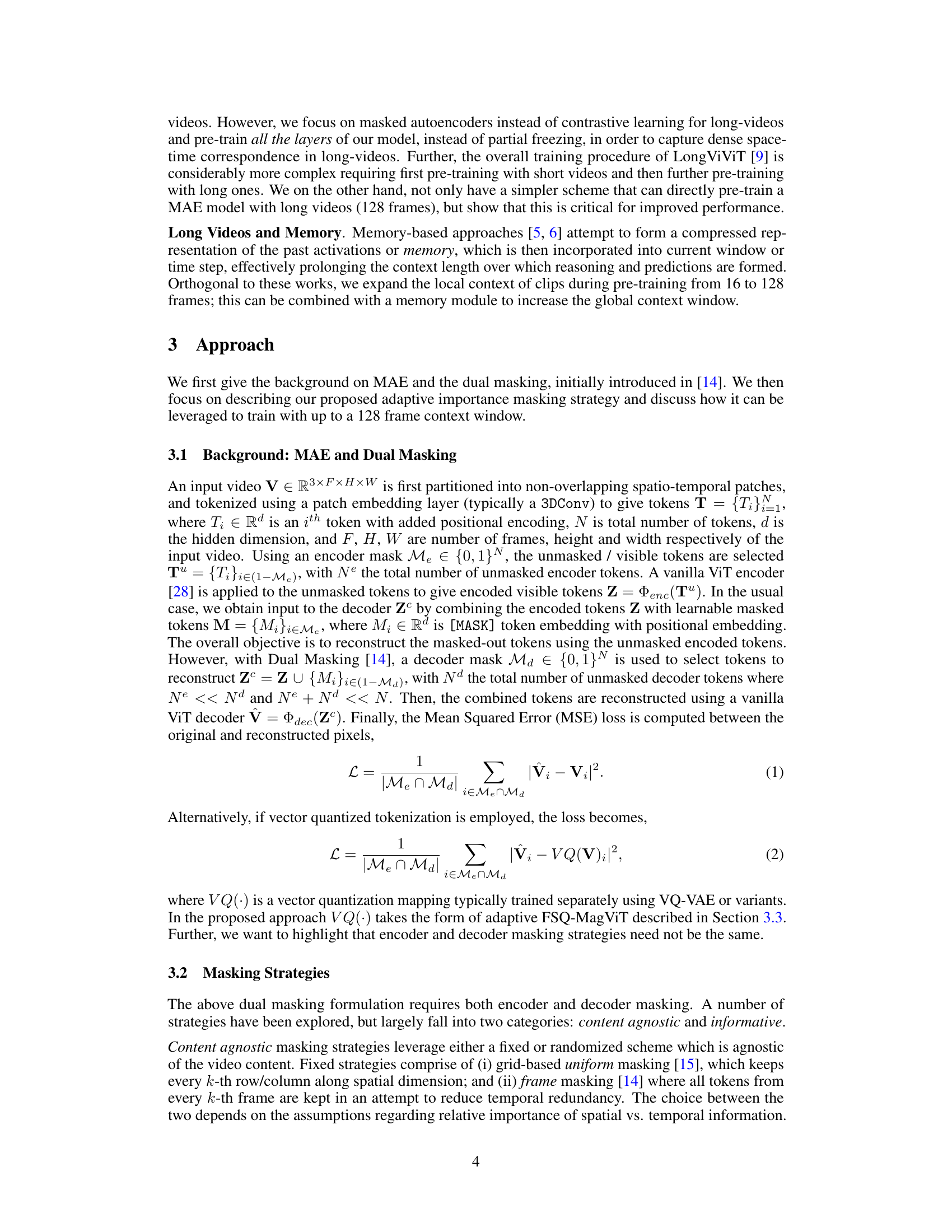

This figure illustrates the training process of the Adaptive FSQ-MagViT tokenizer. The tokenizer, a combination of a MAGVIT encoder and a CNN-based token scorer, assigns importance scores to video tokens. A differentiable top-k selection layer then chooses the most important tokens. During training, the less important tokens are masked (set to zero), and the MAGVIT decoder reconstructs the video from the remaining tokens and the learned importance scores. After training, this tokenizer is frozen and used to generate target tokens for the video MAE pre-training phase.

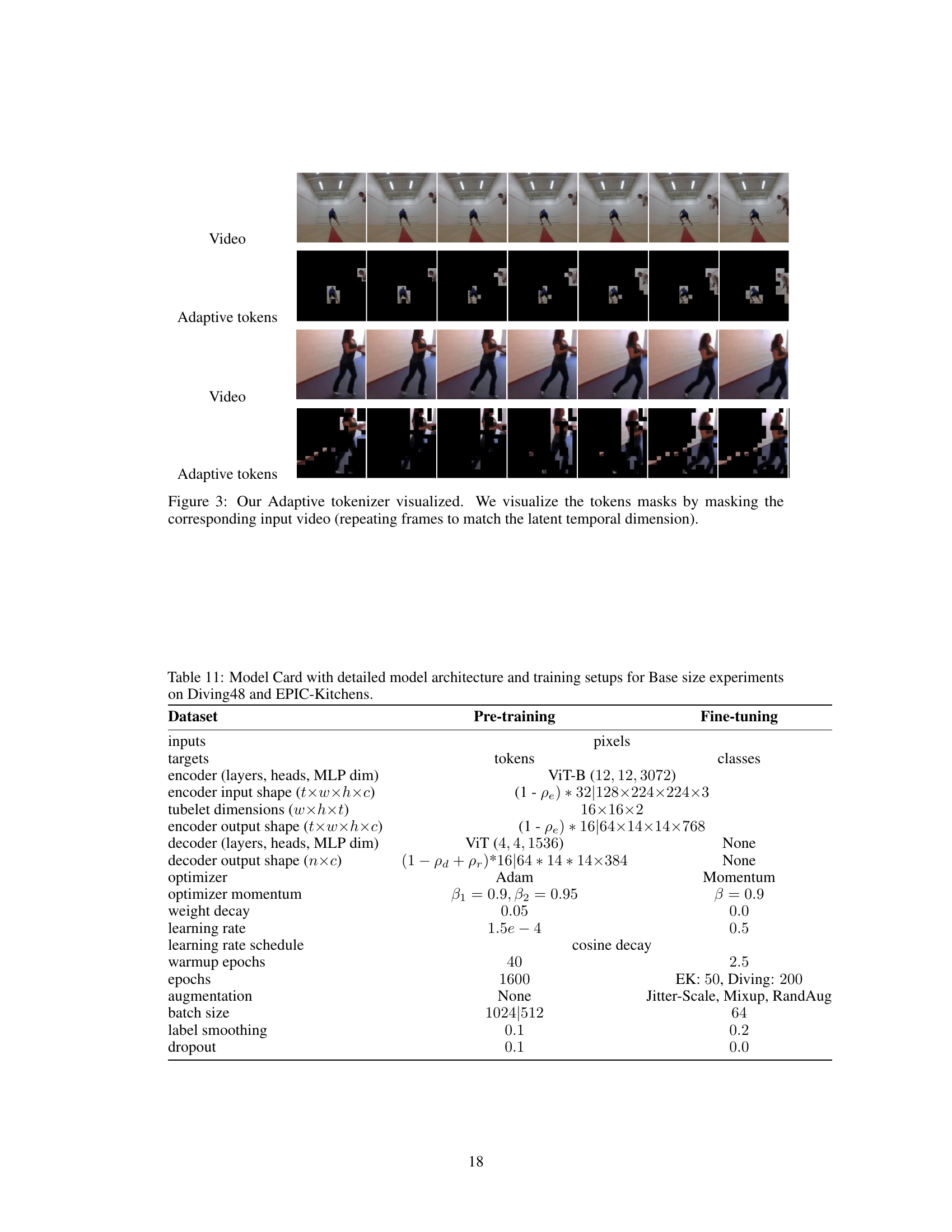

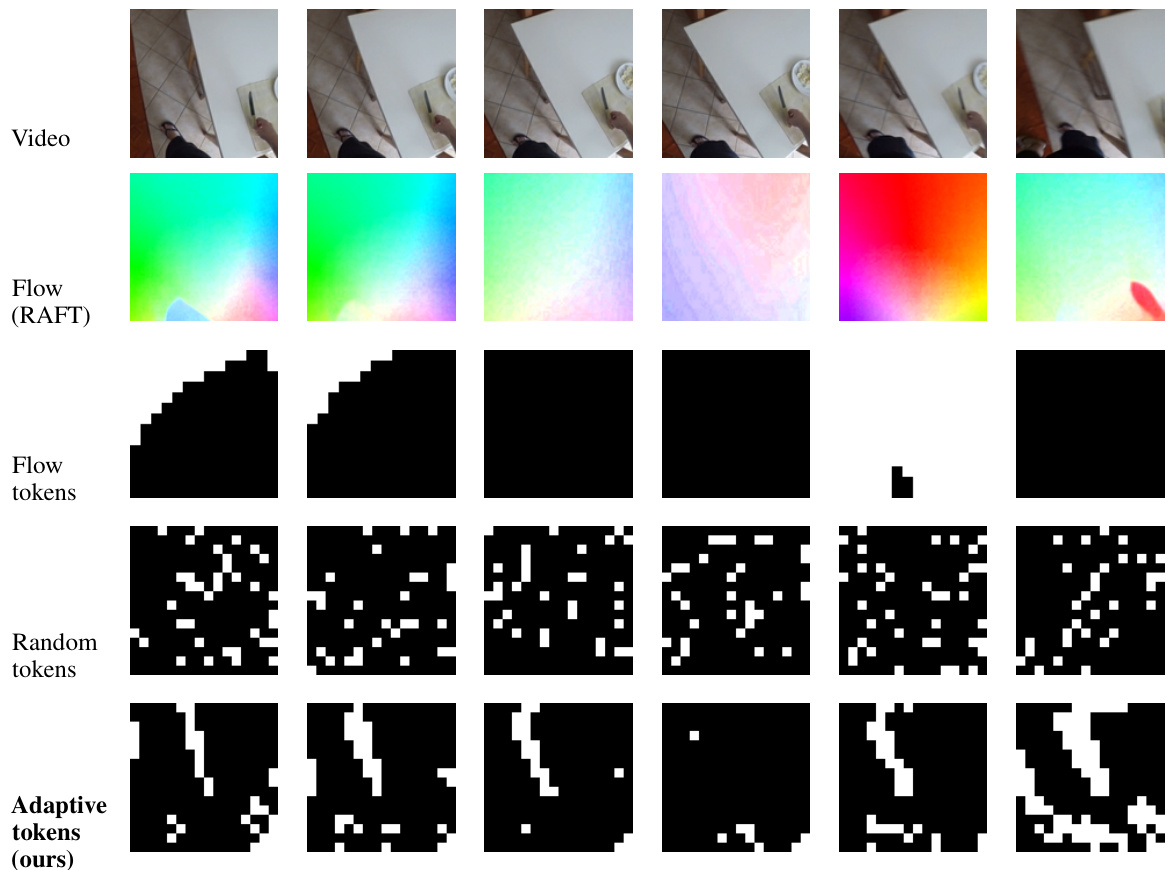

This figure shows how the adaptive tokenizer selects tokens for a video masked autoencoder. The top row displays the original video frames. The bottom row displays the selected tokens after the adaptive tokenizer has processed the video. The masked areas of the video are represented as black. The figure demonstrates that the tokenizer focuses on the most important parts of the video for reconstruction, rather than randomly selecting tokens.

This figure compares different token selection strategies for video masked autoencoders. It shows how flow-based methods struggle with background motion, while random masking fails to focus on important parts of the video. The authors’ adaptive method (ours) highlights the relevant changes in the video sequence. This visualizes the benefits of their proposed content-dependent masking.

More on tables

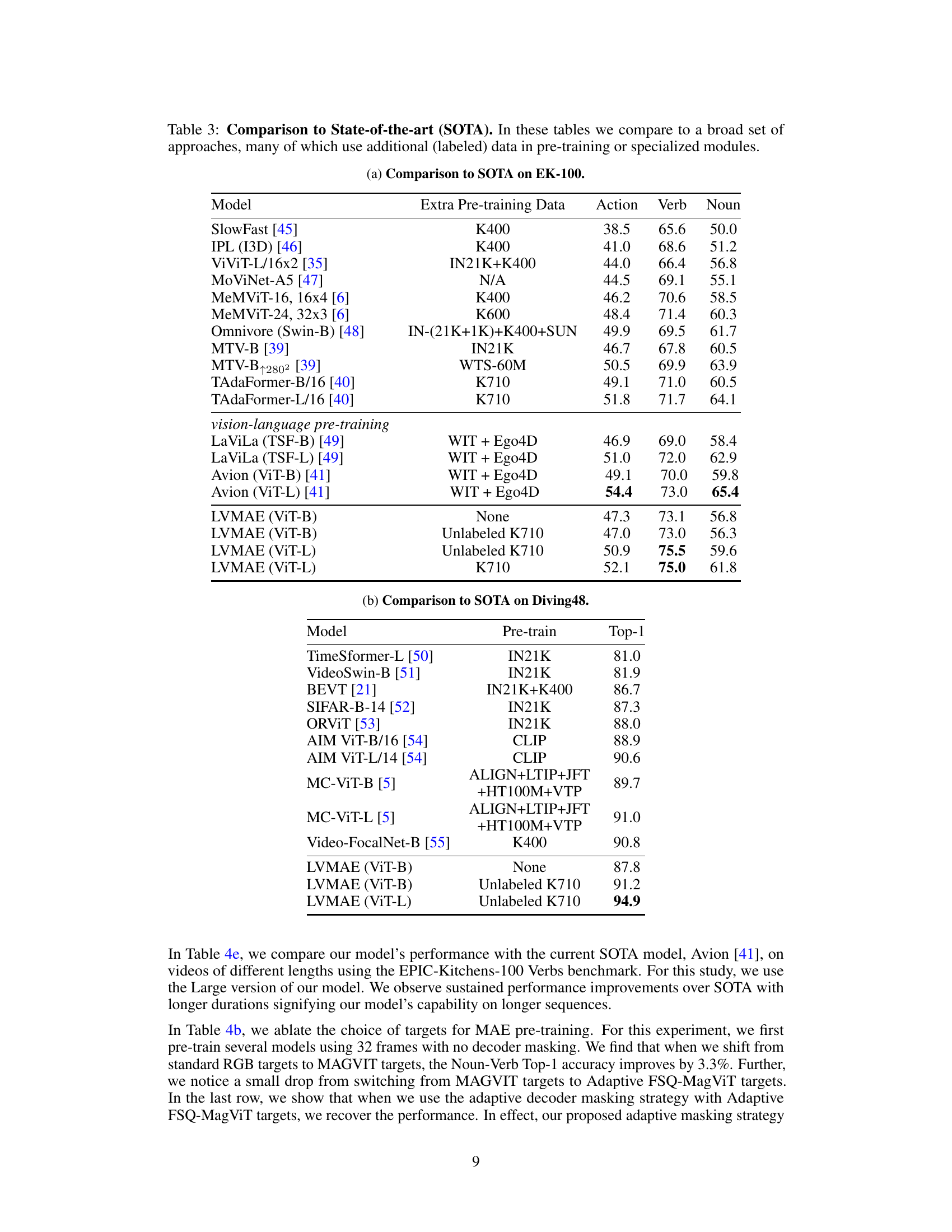

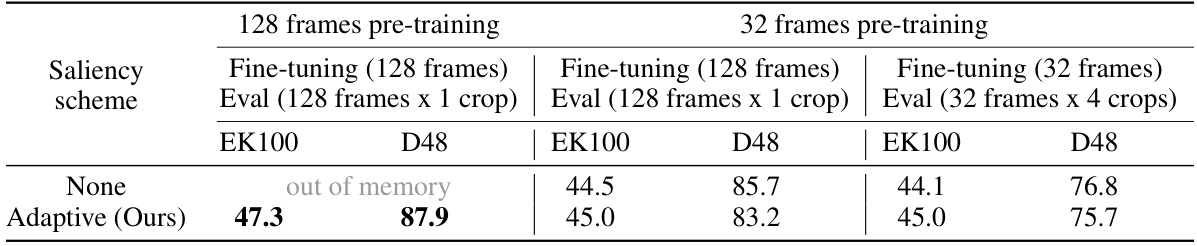

This table compares the performance of the proposed long-video masked autoencoder (LVMAE) model with different pre-training strategies on two datasets (EK100 and D48). It shows the top-1 action classification accuracy after fine-tuning models pretrained using either 128 frames or 32 frames. The table highlights that using 128-frame pre-training with the adaptive decoder masking strategy leads to significantly better results compared to the short video counterparts, demonstrating the effectiveness of the LVMAE approach on long-range video understanding. Note that the fine-tuning stage also uses different frame numbers according to the pre-training setting.

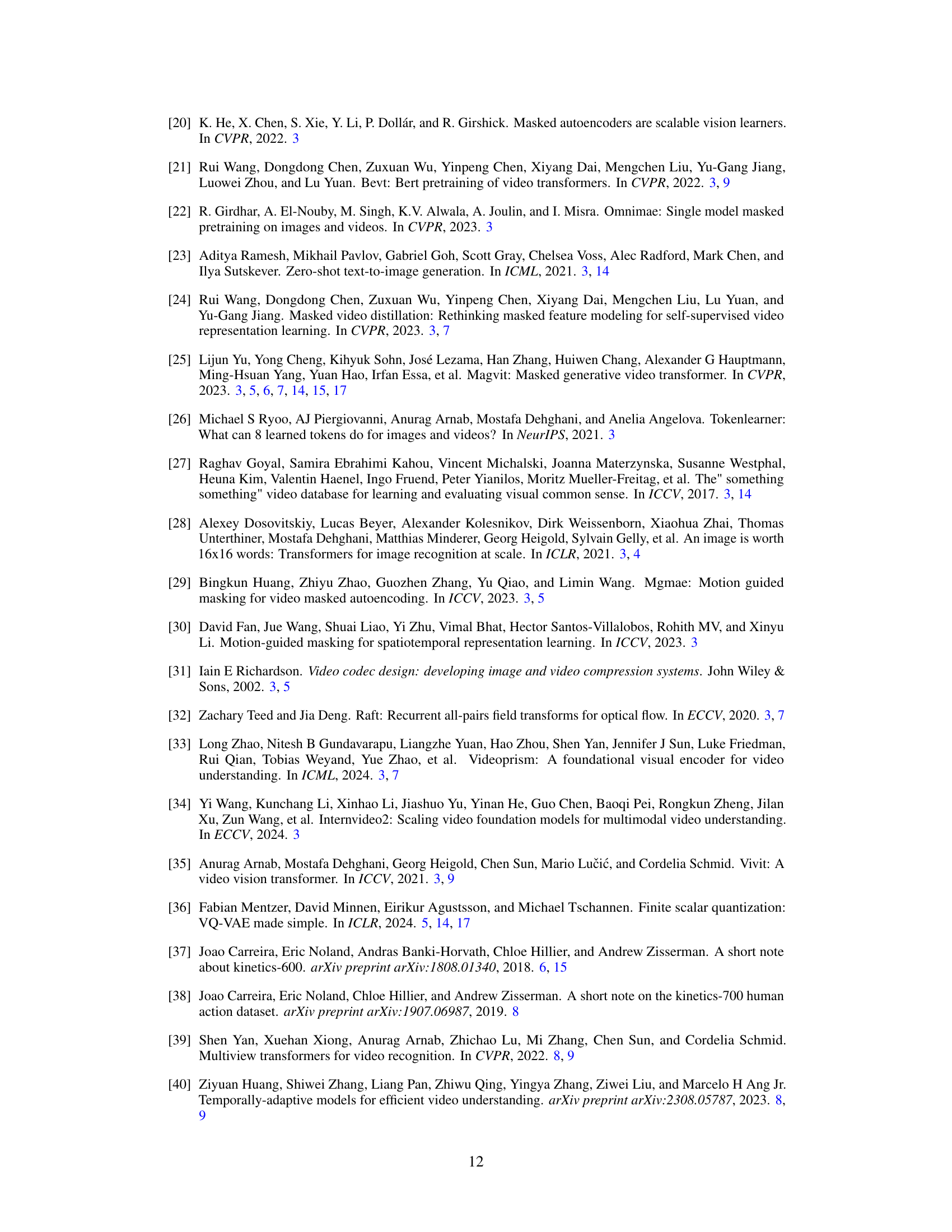

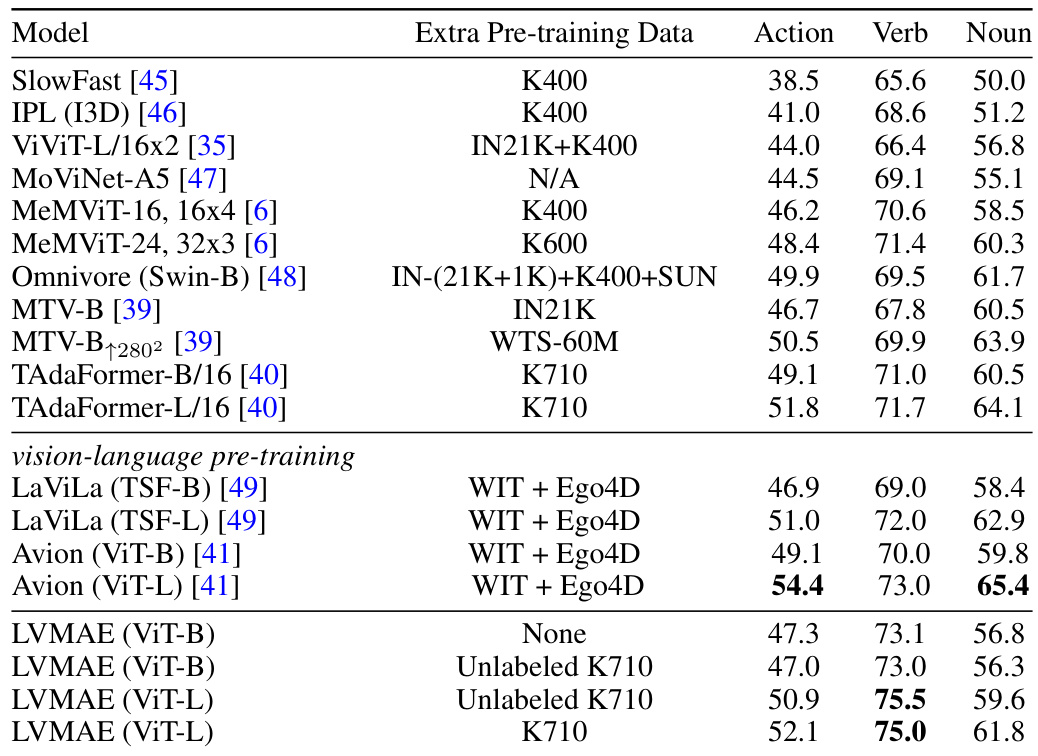

This table compares the proposed LVMAE model’s performance with other state-of-the-art models on EPIC-Kitchens-100 and Diving48 datasets. It highlights that many SOTA models utilize additional labeled data or specialized architectures during pre-training, whereas LVMAE achieves competitive results using only unlabeled video data and a standard ViT architecture. The table showcases the action, verb, and noun classification accuracy of each model, demonstrating LVMAE’s strong performance, particularly on verb classification.

This table compares the proposed LVMAE model’s performance with other state-of-the-art models on EPIC-Kitchens-100 and Diving48 datasets. It highlights that many SOTA models leverage additional labeled data or specialized architectures, while LVMAE achieves competitive results using a simpler architecture and video-only pre-training.

This table compares different decoder masking strategies on short videos (32 frames) for the EK100 dataset. It shows the top-1 action classification accuracy after fine-tuning MAE models pretrained with either pixel (RGB) or token (FSQ-MagViT) reconstruction targets. A consistent 15% token budget was used for decoder masking. The results demonstrate that the proposed adaptive decoder masking scheme outperforms other methods, including content-agnostic (uniform, random) and content-informed (optical flow, EVEREST) approaches, even with a significantly reduced token budget.

This table compares different decoder masking strategies for short videos (32 frames) on the EK100 dataset. The experiment uses two reconstruction targets: RGB pixels and FSQ-MagViT tokens. The token budget is consistently set to 15%. The table shows that the proposed ‘Adaptive’ masking strategy outperforms other methods, including uniform, random, and optical flow-based masking, even when the latter methods leverage content information. The results highlight the efficacy of the adaptive masking approach in improving fine-tuning performance on a single temporal crop.

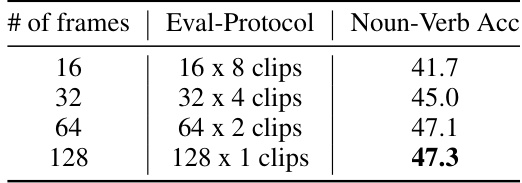

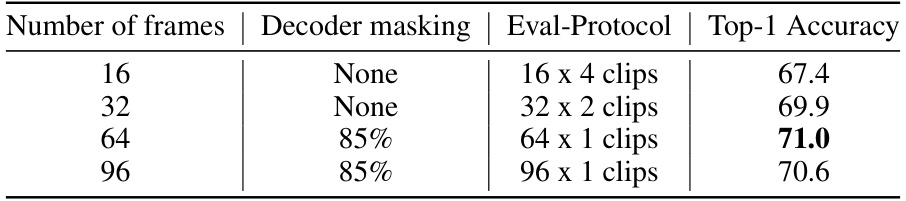

This table shows the ablation study on the number of frames used for training the model. The experiment uses the adaptive masking strategy and FSQ-MagViT tokens as reconstruction targets. The results show that increasing the number of frames from 16 to 32 to 64 improves the performance significantly, but the improvement diminishes when moving from 64 to 128 frames, suggesting diminishing returns for longer video contexts.

This table compares the performance of different decoder masking strategies when training a Masked Autoencoder (MAE) model on long videos (128 frames). It shows the top-1 accuracy achieved on downstream action classification tasks (EK100 and D48) after fine-tuning the model pretrained with different masking schemes (None, Adaptive, etc.). The table highlights that the adaptive masking strategy, which selects important tokens for reconstruction, enables efficient training on long videos and outperforms other methods.

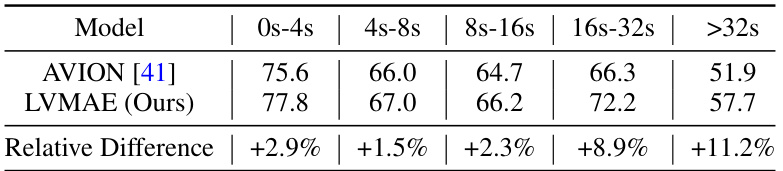

This table compares the performance of the proposed LVMAE model against the state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the EPIC-Kitchens-100 Verbs benchmark. It focuses specifically on the performance across different video lengths (0-4s, 4-8s, 8-16s, 16-32s, >32s) to highlight the model’s capability of handling long-range temporal dependencies. The relative difference column indicates the percentage improvement of LVMAE over the Avion model for each length category. This demonstrates the effectiveness of LVMAE in handling longer videos.

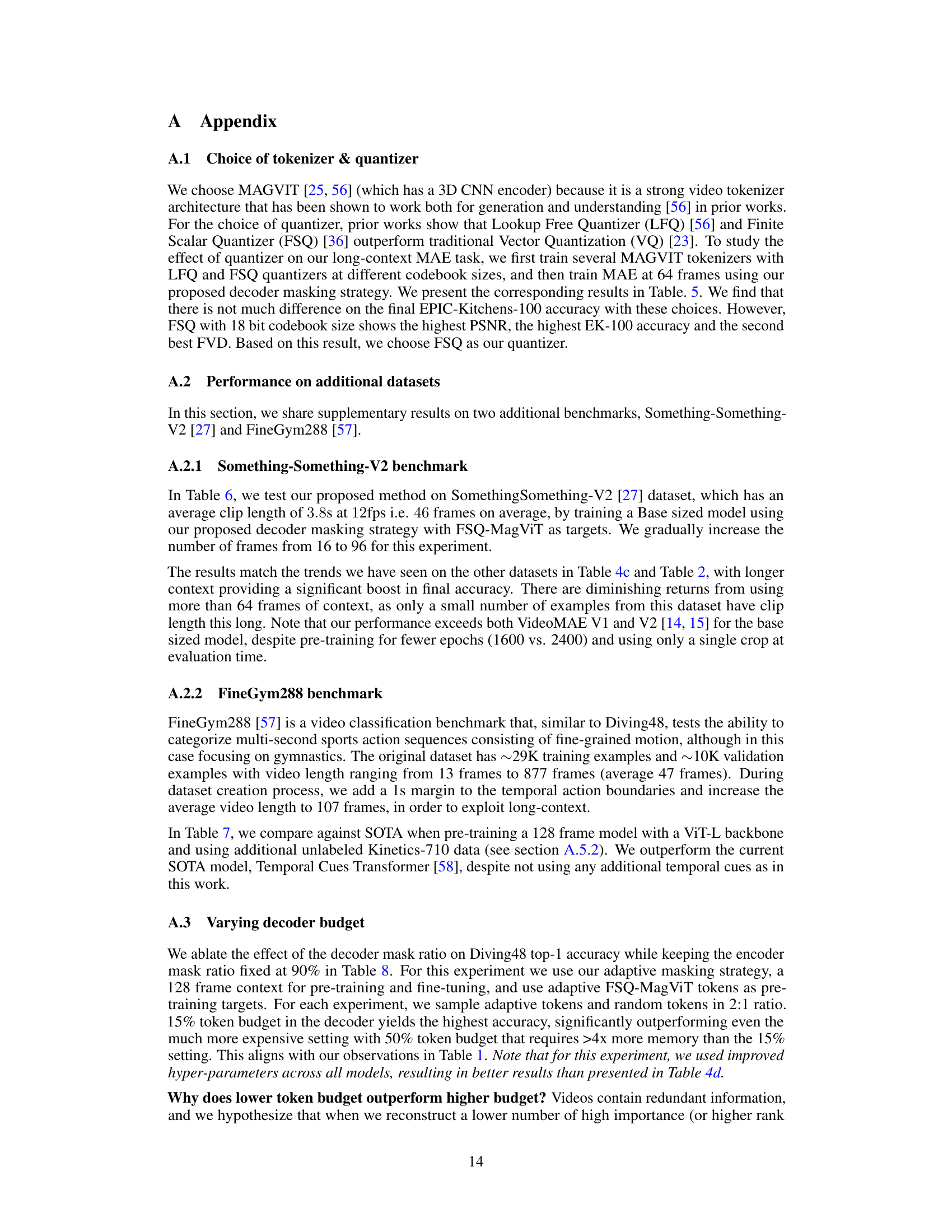

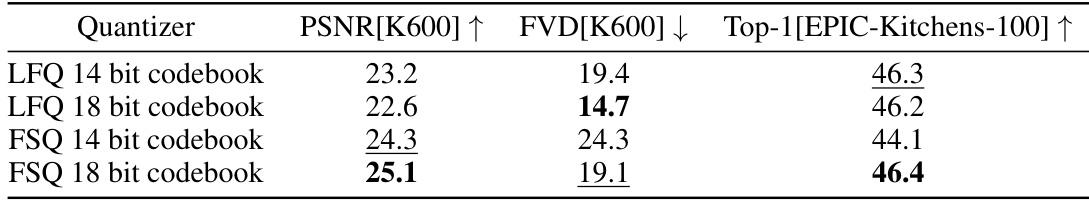

This table compares the performance of two different quantization methods (LFQ and FSQ) with varying codebook sizes on the Kinetics600 benchmark. It shows PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), FVD (Fréchet Video Distance), and top-1 accuracy on the EPIC-Kitchens-100 dataset for MAE models trained using each quantizer. This helps determine which quantizer and codebook size performs best for video masked autoencoder (MAE) model training.

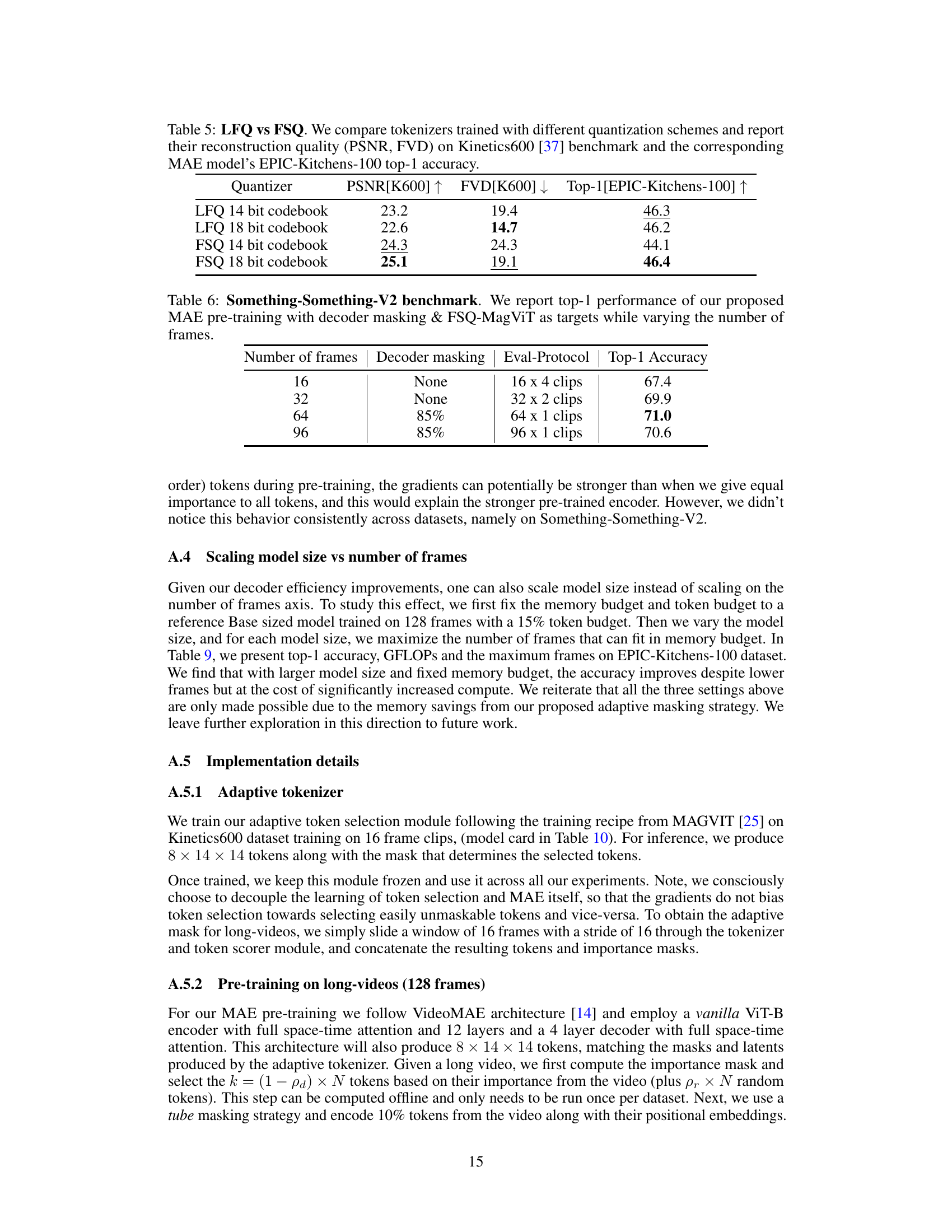

This table presents the results of experiments on the Something-Something-V2 dataset, which tests the model’s ability to understand actions using different lengths of video clips. The performance is measured using the top-1 accuracy metric, and the table shows how the performance changes as the number of frames used in the pre-training increases from 16 to 96. The decoder masking strategy and the FSQ-MagViT targets remain constant across different frame lengths.

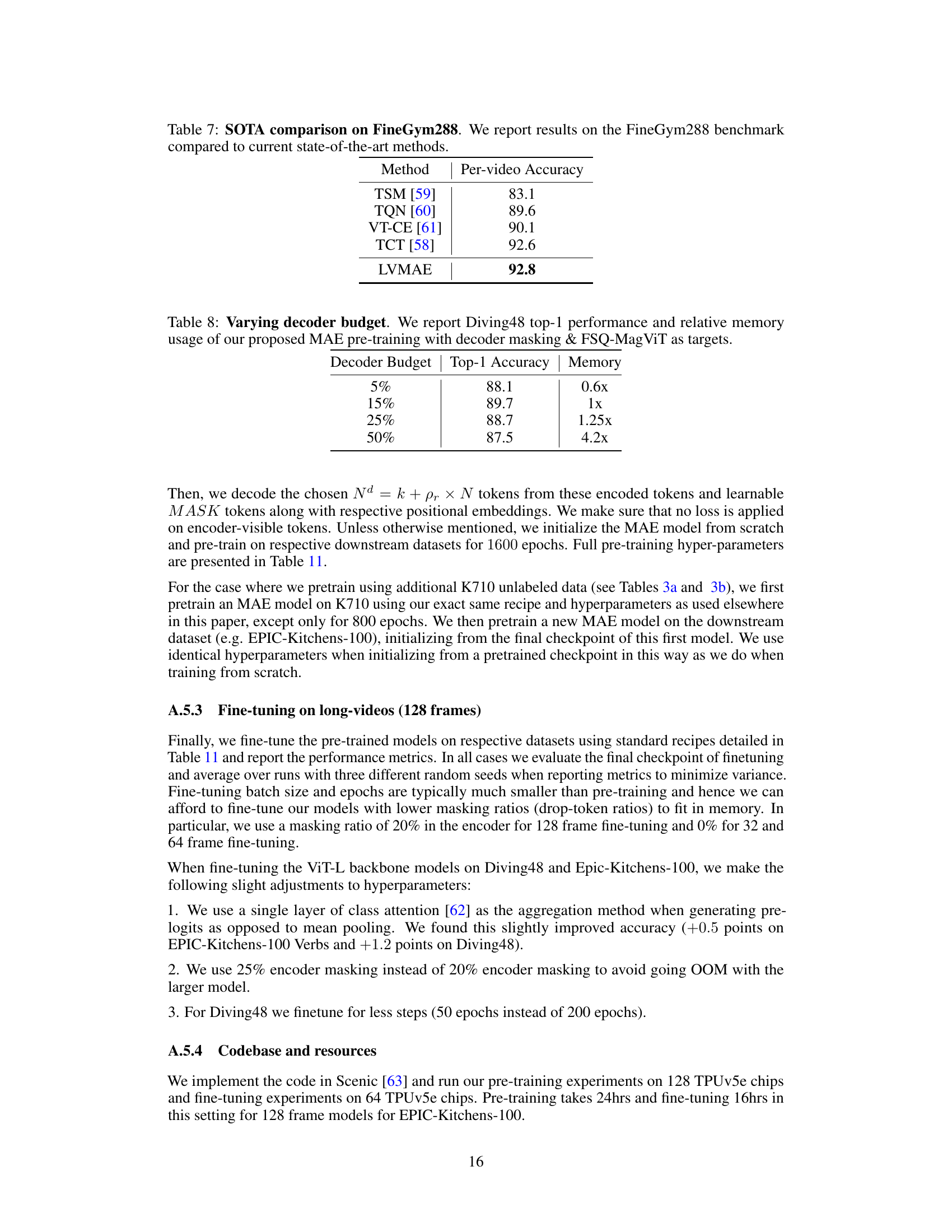

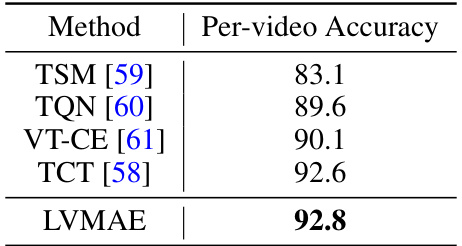

This table compares the performance of the proposed LVMAE model against other state-of-the-art models on the FineGym288 benchmark. FineGym288 is a video classification benchmark focusing on gymnastics, and it tests the ability to categorize multi-second sports action sequences consisting of fine-grained motion. The table shows that LVMAE achieves the highest per-video accuracy, outperforming existing methods.

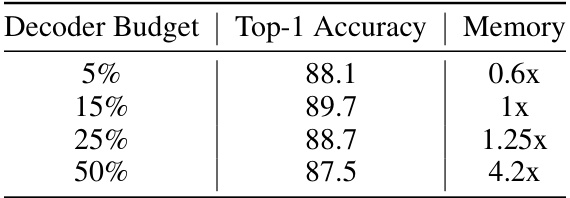

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the decoder masking strategy. It shows how varying the decoder token budget affects the top-1 accuracy on the Diving48 dataset and the relative memory usage compared to the baseline (15% token budget). The results indicate that a 15% token budget yields the best performance, achieving a top-1 accuracy of 89.7 while maintaining reasonable memory consumption.

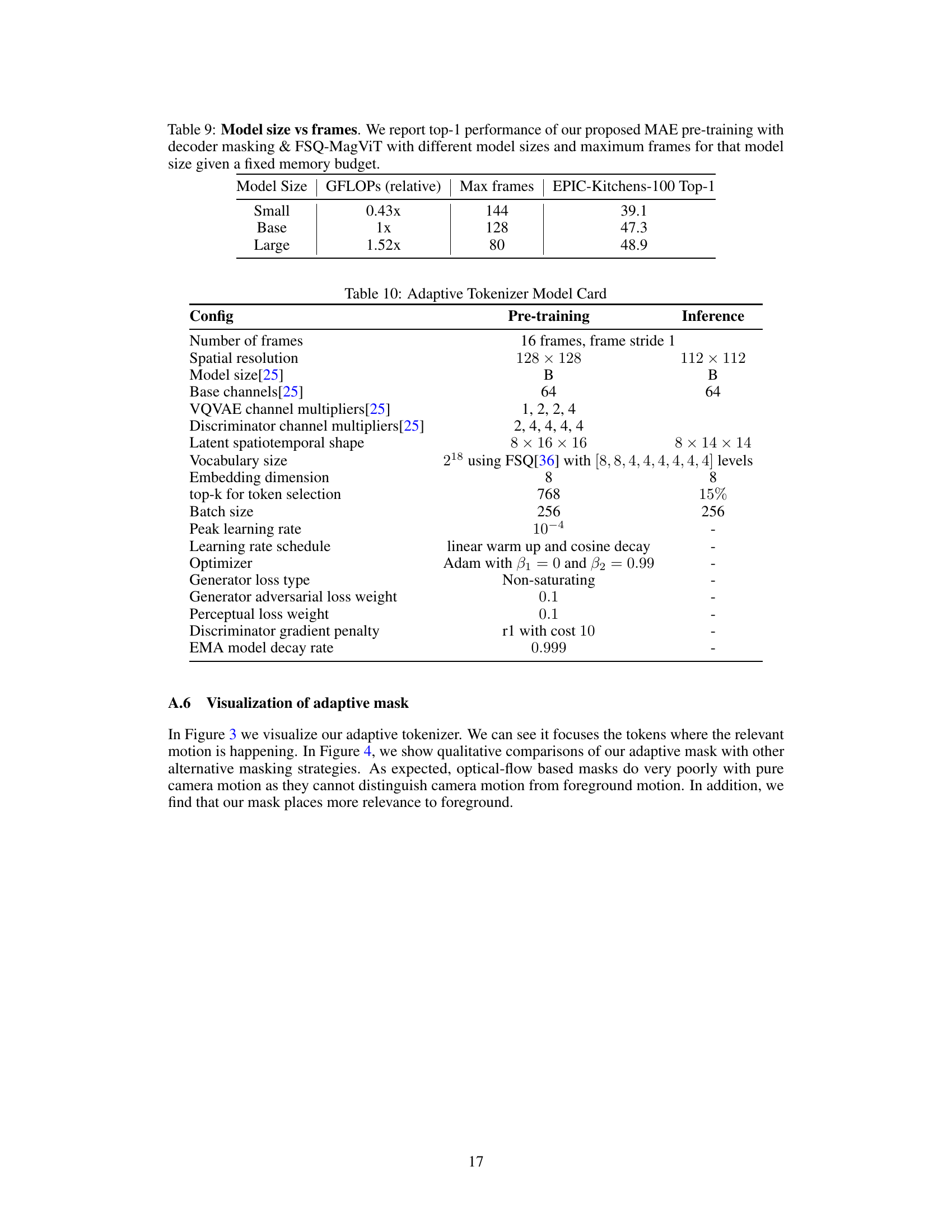

This table shows the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the impact of model size on the maximum number of frames that can be processed while maintaining a fixed memory budget. Three different model sizes (Small, Base, Large) were used, each with varying computational complexity (GFLOPs). The table demonstrates that larger models achieve higher accuracy but are limited to processing fewer frames due to memory constraints. The experiment was performed on the EPIC-Kitchens-100 dataset.

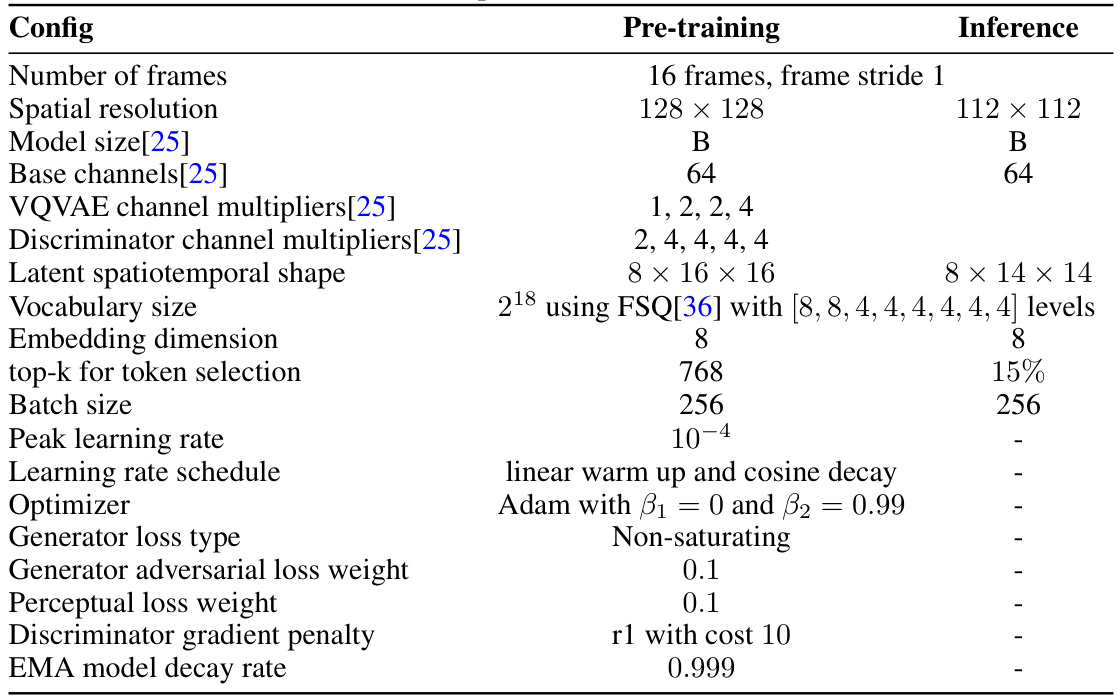

This table details the hyperparameters and architecture used for training the adaptive tokenizer model. It includes information about the number of frames, spatial resolution, model size, channel multipliers, latent shape, vocabulary size, embedding dimension, top-k selection, batch size, learning rate schedule, optimizer, loss functions, and other relevant training details. This tokenizer plays a crucial role in the adaptive masking strategy of the proposed method.

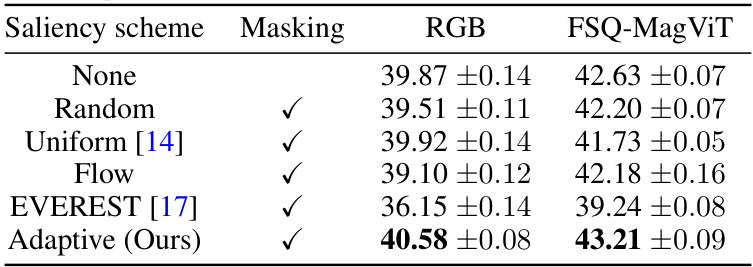

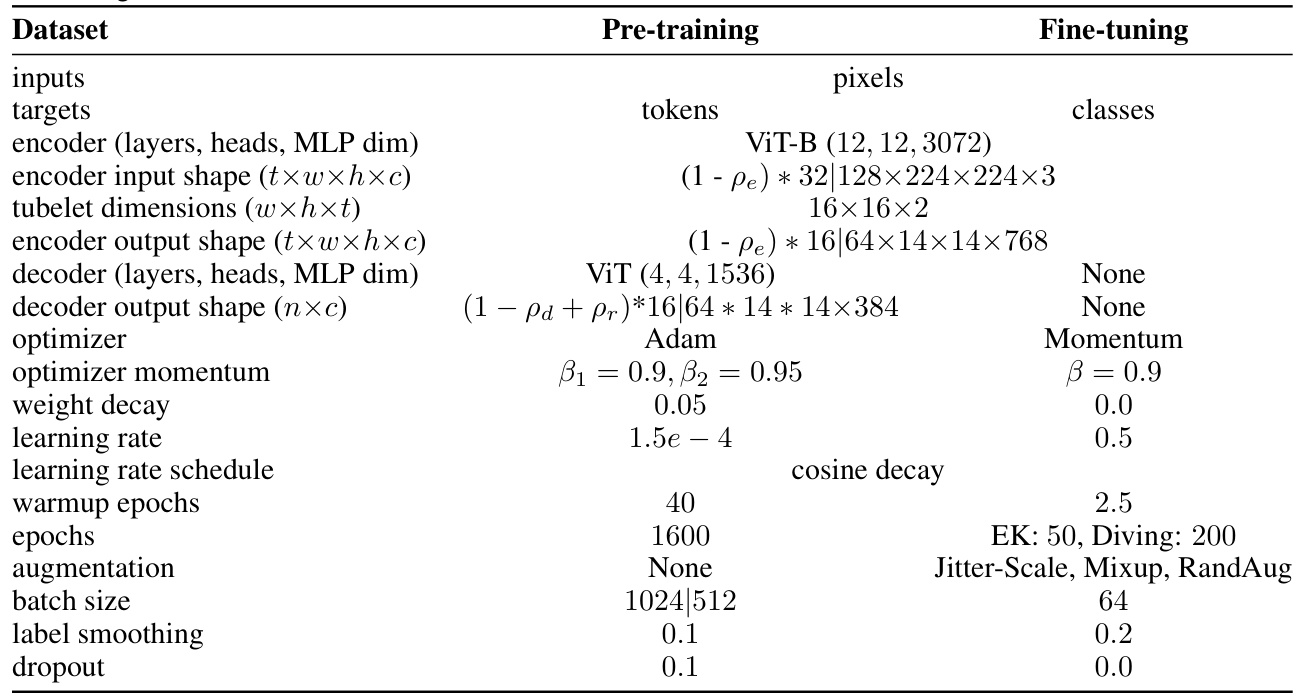

This table details the model architecture and training hyperparameters used in the experiments. It shows the configuration for both pre-training and fine-tuning stages, specifying the model type (ViT-B), number of layers, heads, MLP dimension, input and output shapes, optimizer, learning rate schedule, augmentation techniques, batch size, label smoothing, and dropout rate for both the encoder and decoder. The table also indicates the type of target used for the pre-training stage (pixels or tokens). The differences in hyperparameters between the pre-training and fine-tuning phases highlight the adaptation strategy employed during the downstream task.

Full paper#