↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing opponent modeling approaches struggle with generalization to unknown opponent policies and unstable performance. These limitations stem from pretraining-focused approaches lacking theoretical guarantees and testing-focused methods exhibiting performance instability during online finetuning.

The proposed Opponent Modeling with In-context Search (OMIS) addresses these issues. OMIS uses in-context learning-based pretraining to train a Transformer model, including an actor, opponent imitator, and critic. During testing, OMIS performs decision-time search (DTS) using these pretrained components. This ’think before you act’ strategy allows for improved decision-making in the presence of unknown or non-stationary opponents. Theoretically, OMIS guarantees convergence in opponent policy recognition and performance stability; empirically, it consistently outperforms other methods across multiple environments.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel approach to opponent modeling (OM) that significantly improves upon existing methods. The theoretical analysis provides strong guarantees, and empirical results demonstrate superior performance and stability. This opens new avenues for research in multi-agent systems, particularly in competitive and non-stationary environments. Its use of in-context learning and decision-time search provides a framework adaptable to other related areas in AI.

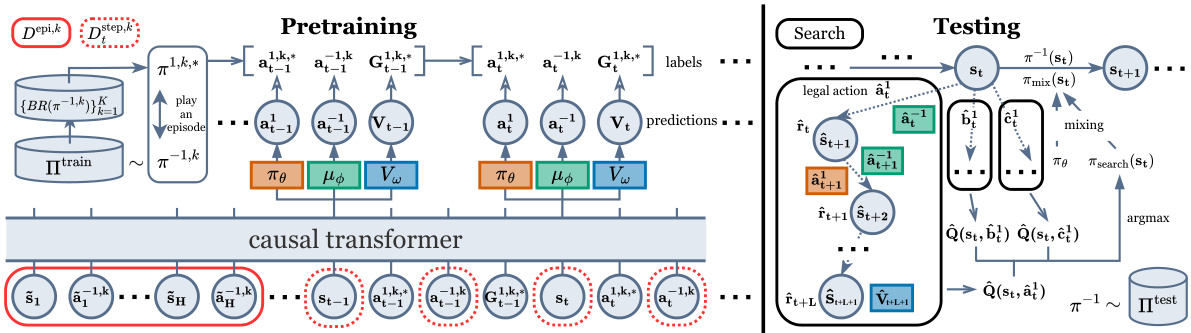

Visual Insights#

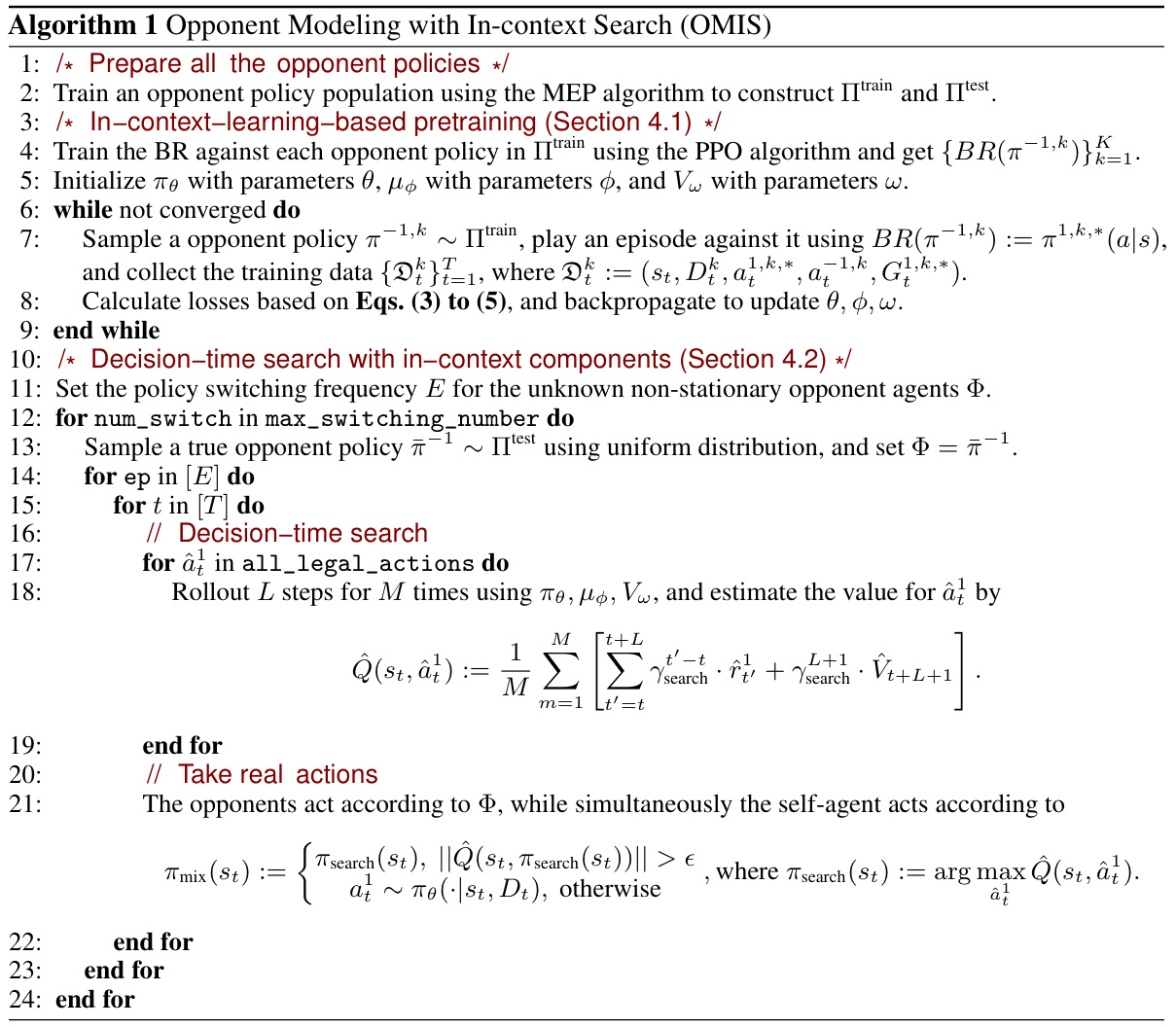

This figure illustrates the overall architecture and training/testing procedures of the Opponent Modeling with In-context Search (OMIS) model. The left side details the pretraining phase, which involves training best responses (BRs) against various opponent policies from the training set (Πtrain), collecting training data via self-play using these BRs, and finally training a Transformer model (consisting of an actor, opponent imitator, and critic) using in-context learning (ICL). The right side illustrates the testing phase where, upon encountering an unknown opponent, OMIS employs decision-time search (DTS) to refine its actor policy. The DTS involves multiple rollouts for each legal action to predict returns, selecting the best action, and using a mixing technique to combine the DTS-refined policy with the original policy.

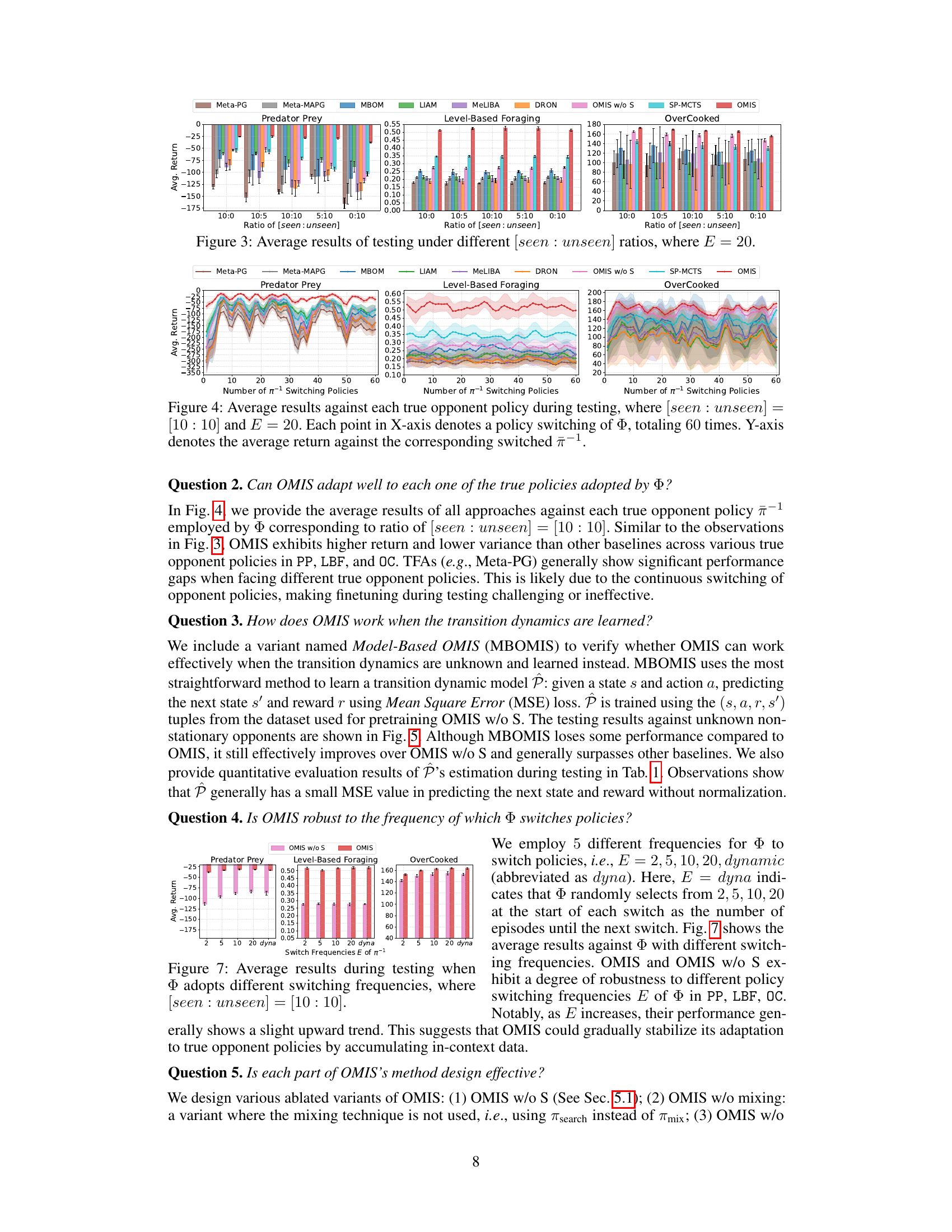

This table presents a quantitative evaluation of the learned dynamic transition model P’s performance during the testing phase. It shows the mean squared error (MSE) for next state and reward prediction across different ratios of seen to unseen opponent policies in the testing set. The results are averaged over multiple experimental runs (E=20). Lower MSE values indicate better estimation accuracy.

In-depth insights#

In-context learning#

In-context learning (ICL), a core concept in the paper, is presented as a powerful mechanism for training a Transformer model adaptable to diverse opponents. ICL’s agnostic approach, learning the learning algorithm itself, is highlighted as crucial for endowing the model with the necessary adaptability. The paper emphasizes ICL’s theoretical advantages, proving convergence in opponent policy recognition and good generalization. Empirical validation further demonstrates that OMIS, employing ICL pretraining, outperforms other methods, showcasing its effectiveness in diverse competitive scenarios. While ICL is not explicitly defined in the text, its properties of adaptability and generalizability are key features of the proposed OMIS model, providing a strong foundation for its performance and making it a particularly interesting and potentially impactful contribution to opponent modeling.

Decision-time search#

Decision-time search (DTS) is a crucial component of the proposed OMIS framework, addressing limitations of existing opponent modeling approaches. Instead of directly acting based on a pretrained policy, DTS incorporates a ’think before you act’ strategy. It involves simulating future game states using pretrained in-context components (actor, opponent imitator, critic) to estimate the value of each possible action. This allows OMIS to refine its action selection, considering potential opponent responses and maximizing long-term rewards. The use of DTS helps to alleviate instability issues seen in previous approaches. It also provides theoretical improvement guarantees, ensuring more stable and effective opponent adaptation, particularly when facing unknown or non-stationary opponents.

Opponent modeling#

Opponent modeling in multi-agent systems focuses on enabling agents to predict and adapt to the behaviors of other agents. It’s crucial for effective decision-making in competitive, cooperative, or mixed environments. Traditional approaches often struggle with generalization to unseen opponents and performance instability. Recent advancements leverage techniques like representation learning, Bayesian methods, and meta-learning to improve these aspects. However, challenges remain in handling non-stationary opponents whose strategies change over time and in providing theoretical guarantees for generalization. Decision-time search offers a promising avenue for refining agent policies by simulating future interactions and evaluating outcomes before acting. This is especially useful for non-stationary opponents. Future work should investigate incorporating these advances into methods with stronger theoretical foundations and analyzing their efficacy in more complex scenarios such as imperfect information games.

Theoretical analysis#

The theoretical analysis section of this research paper appears crucial in validating the proposed OMIS approach. It addresses the limitations of existing PFA and TFA methods, demonstrating how OMIS overcomes these shortcomings. The convergence proof for OMIS without search (OMIS w/o S) under reasonable assumptions is a significant contribution, establishing the algorithm’s soundness in recognizing opponent policies and generalizing effectively. The subsequent policy improvement theorem for OMIS with search provides guarantees of performance enhancement. This is particularly important as it directly addresses the instability issues associated with traditional TFA methods. The analysis not only provides theoretical underpinnings but also offers valuable insights into the workings of the OMIS framework, strengthening the credibility and reliability of the empirical results presented in the paper.

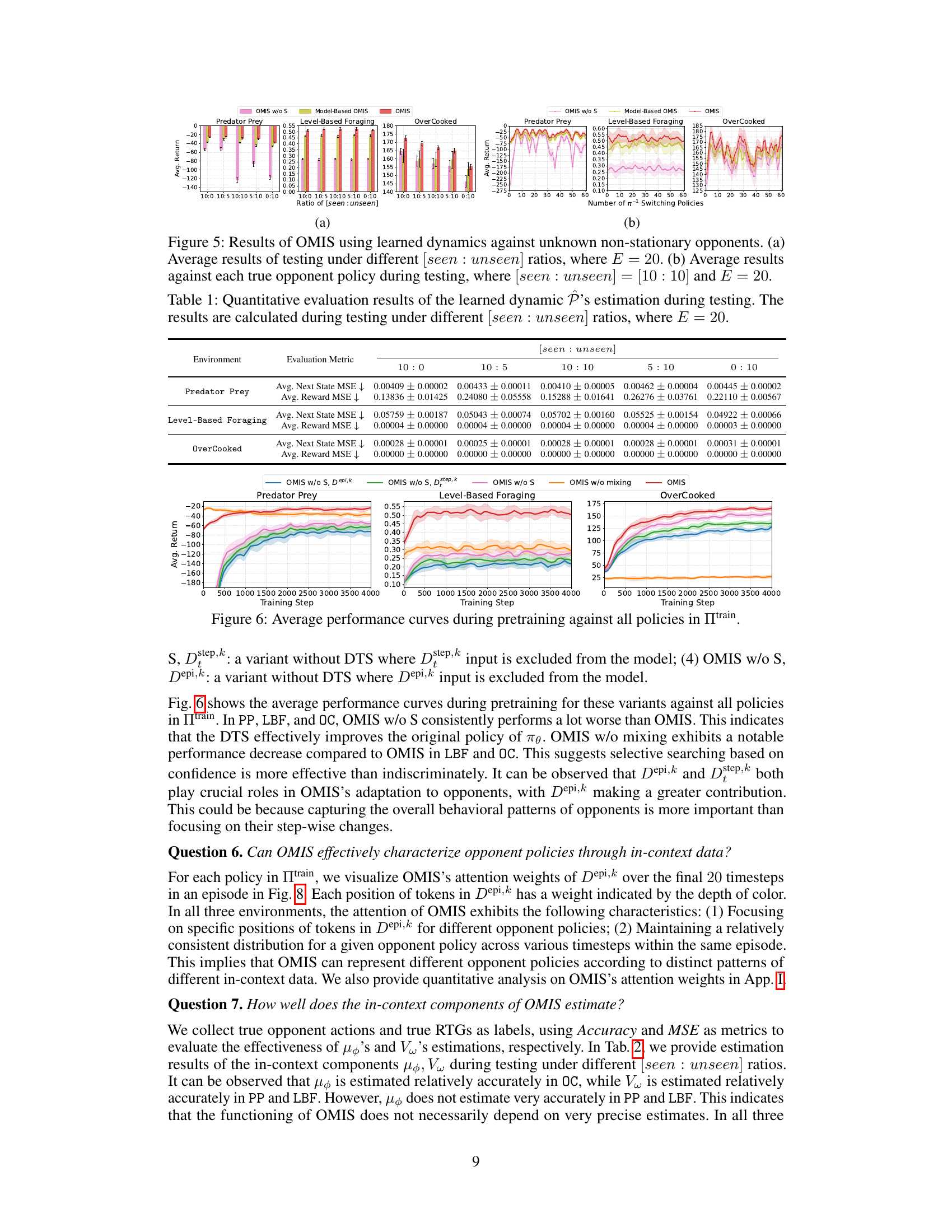

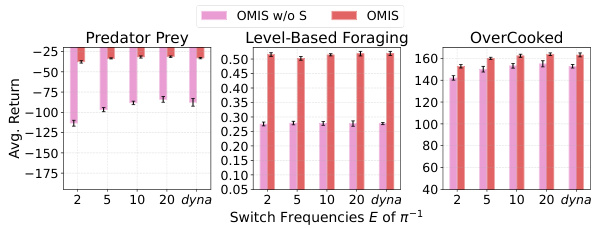

Experimental results#

The experimental results section of a research paper is crucial for demonstrating the validity and effectiveness of the proposed methods. A strong results section will present clear visualizations, such as graphs and tables, showing how the new approach performs compared to existing baselines across multiple evaluation metrics. Statistical significance testing, such as p-values or confidence intervals, is essential to support the claims of improvement. A well-written results section also goes beyond simply reporting numbers; it provides a thoughtful analysis of the findings, discussing both expected and unexpected outcomes. Ablation studies, which systematically remove components of the model to assess their individual contributions, are highly valuable. Similarly, the analysis should explore the impact of hyperparameter choices on performance. Finally, a discussion of limitations and potential sources of error strengthens the overall credibility of the findings. A thorough evaluation, combined with careful interpretation, allows for drawing meaningful conclusions about the advantages and limitations of the presented work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the overall architecture and training/testing procedures of the OMIS model. The left panel shows the pretraining phase where best responses are trained against various opponent policies and a transformer model is trained with three components (actor, opponent imitator, critic) using in-context learning. The right panel depicts the testing phase where the pretrained model uses decision-time search (DTS) to refine its policy by simulating multiple L-step rollouts for each possible action, estimating their values, and selecting the best action using a mixing strategy to balance search and direct policy output.

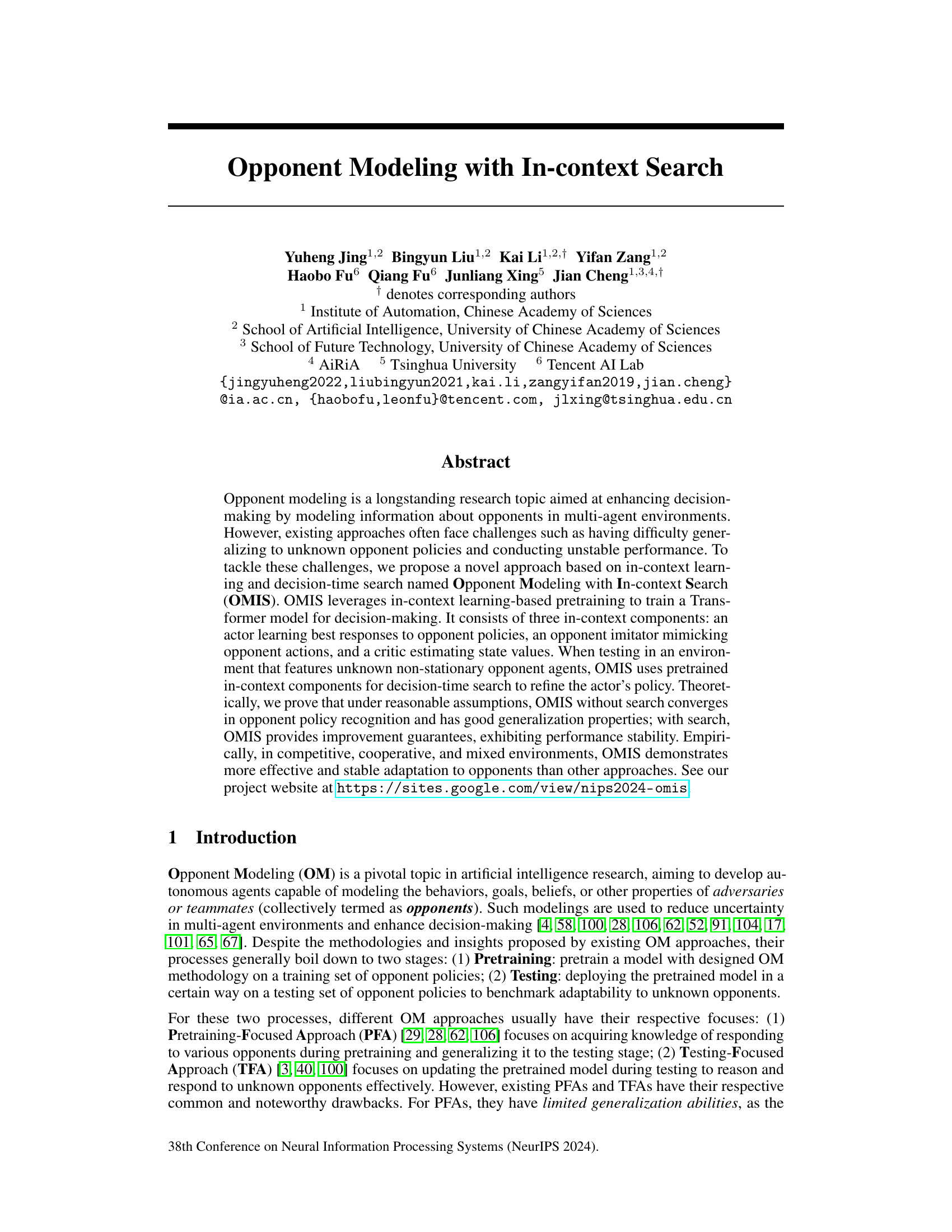

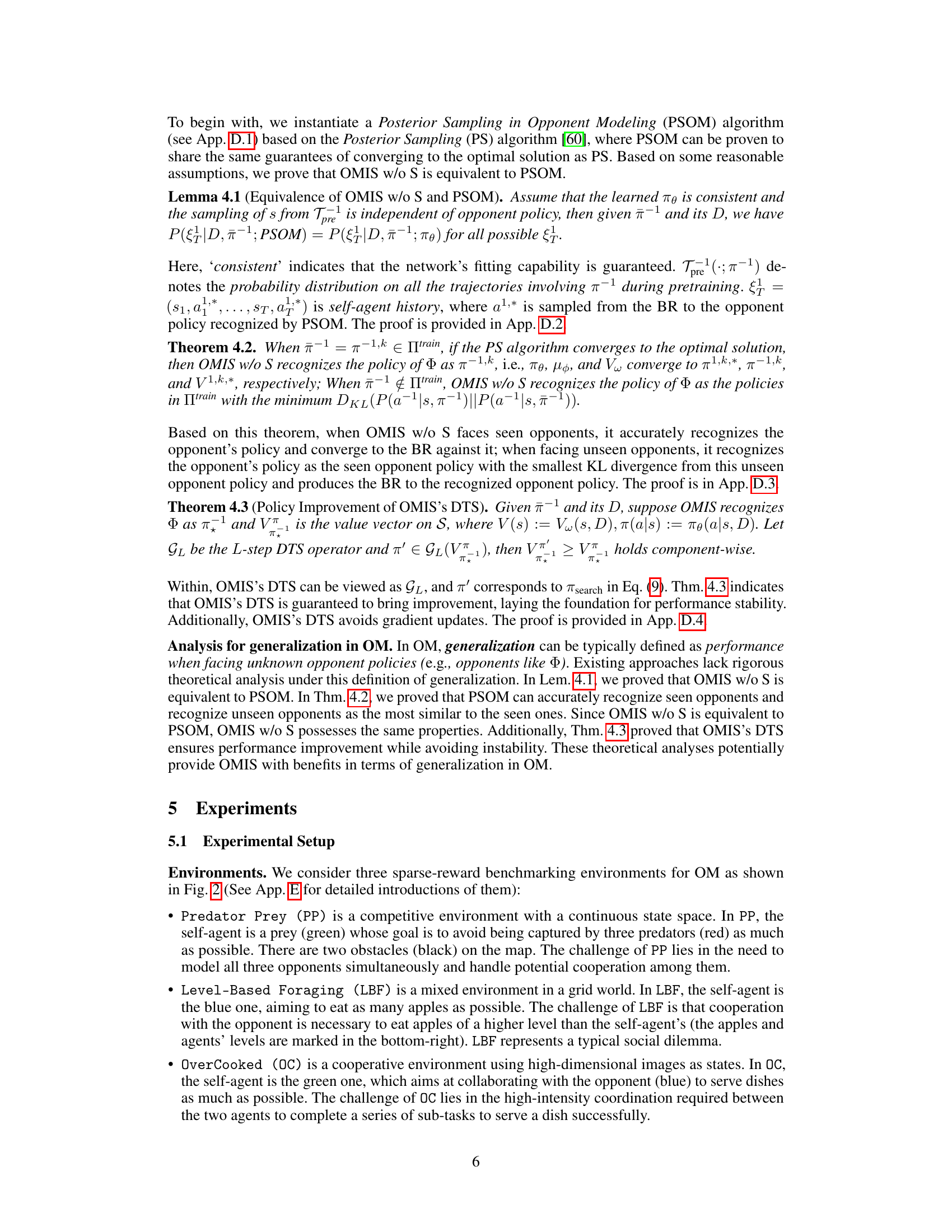

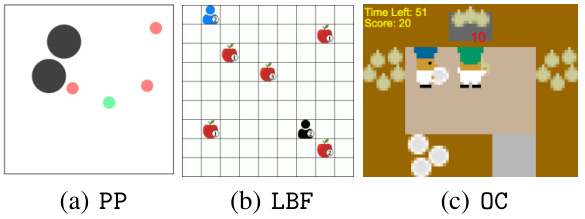

This figure shows the average return of different opponent modeling methods across three environments (Predator Prey, Level-Based Foraging, and Overcooked) under various ratios of seen to unseen opponents. The x-axis represents the ratio of seen to unseen opponents in the test set, and the y-axis represents the average return achieved by each method. Error bars show the standard deviation. The figure demonstrates the performance and stability of OMIS (Opponent Modeling with In-context Search) in adapting to unseen opponents compared to several baselines (PFAs, TFAs, and DTS-based methods).

This figure shows the average return of different OM methods under various ratios of seen and unseen opponent policies. The x-axis represents the ratio of seen to unseen policies, and the y-axis represents the average return. The results show that OMIS consistently outperforms other baselines across three environments, demonstrating better adaptability to unseen opponents.

This figure presents the average testing results of various opponent modeling approaches across three different environments (Predator Prey, Level-Based Foraging, and Overcooked) under different ratios of seen and unseen opponent policies during testing. The x-axis represents the ratio of seen to unseen opponent policies, while the y-axis represents the average return achieved by each approach. The figure demonstrates the performance and stability of OMIS across various ratios of seen and unseen opponent policies, highlighting its effectiveness in adapting to unknown opponents. Error bars likely represent standard deviation.

This figure illustrates the architecture and training/testing procedures of the Opponent Modeling with In-context Search (OMIS) model. The left side details the pretraining process, which involves training best responses (BRs) against various opponent policies, collecting training data through gameplay, and using ICL to train a Transformer model with three components: an actor, opponent imitator, and critic. The right side depicts the testing procedure, where the pretrained model uses a decision-time search (DTS) process to refine its policy. This DTS involves multiple L-step rollouts, value estimation, and a mixing technique to select the best action.

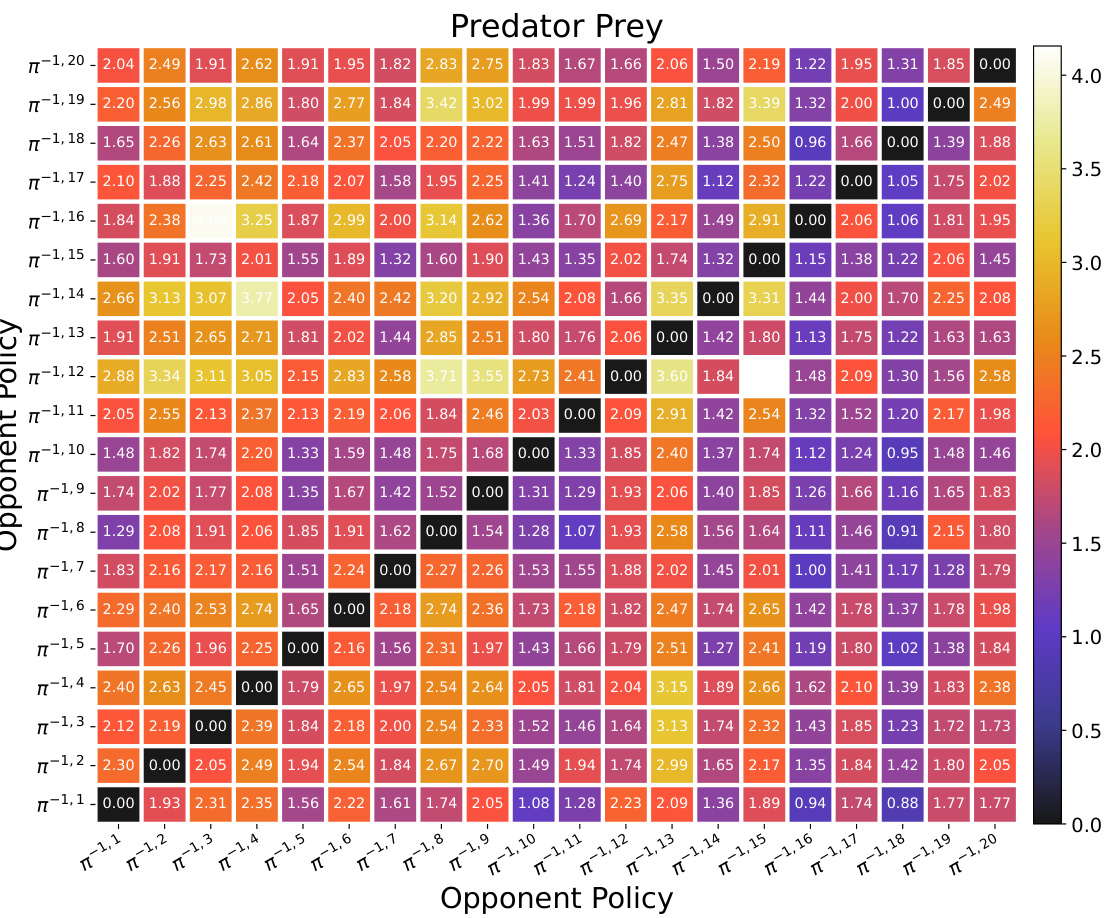

This figure visualizes the attention weights learned by the OMIS model when playing against different opponent policies from the training set (Πtrain). Each heatmap represents a different environment (Predator Prey, Level-Based Foraging, Overcooked). The x-axis represents the opponent policy index in Πtrain, and the y-axis represents the token position within the episode-wise in-context data (Depi,k). The color intensity indicates the attention weight, with warmer colors representing higher attention weights. This visualization helps to understand how OMIS focuses on different aspects of opponent behavior depending on the specific opponent and the environment.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture and training/testing procedures of the OMIS model. The left side shows the pretraining process, which involves training three components (actor, opponent imitator, critic) using in-context learning. The right side details the testing process, where the pretrained model uses decision-time search (DTS) to refine the actor’s policy by simulating multiple rollouts and selecting the best action.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture and training/testing procedures of the OMIS model. The left side details the pretraining phase, which involves training three components (actor, opponent imitator, and critic) using best response policies and in-context learning. The right side depicts the testing phase, focusing on the decision-time search (DTS) process. DTS uses the pretrained components to simulate future game states and refine the actor’s policy by selecting actions based on predicted returns and a mixing strategy.

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the OMIS model. The left side shows the pretraining process, which involves training best responses (BRs) against various opponent policies, collecting training data, and training a Transformer model using in-context learning (ICL) to learn three components: an actor (πθ), an opponent imitator (μφ), and a critic (Vω). The right side depicts the testing process, which employs decision-time search (DTS) to refine the actor’s policy (πθ) by conducting multiple L-step rollouts for each legal action, simulating actions using the pretrained actor and opponent imitator, estimating values using the pretrained critic, and selecting the best action using a mixing technique that combines the search policy (πsearch) and the original actor policy.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture and training/testing procedures of the Opponent Modeling with In-context Search (OMIS) model. The left panel details the pretraining phase, which involves training three components (actor, opponent imitator, and critic) using best response policies and in-context learning. The right panel depicts the testing phase, where decision-time search (DTS) refines the actor’s policy by simulating multiple rollouts to estimate the value of each action and ultimately select the best option. A mixing technique balances the search policy and the original actor policy for action selection.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture and the training and testing procedures of the OMIS model. The left side shows the pretraining phase, where best responses (BRs) are trained against various opponent policies. Training data is collected by playing against opponents using BRs. A Transformer model is then trained using in-context learning with three components: an actor, an opponent imitator, and a critic. The right side shows the testing phase. During testing, the model uses the pretrained components for decision-time search (DTS) to refine the actor’s policy. DTS involves multiple rollouts of each legal action, estimating the value and selecting the best action. A mixing technique combines the search policy and the original actor policy to make the final action decision.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture and training/testing procedures of the OMIS model. The left side details the pretraining phase, showing the training of best responses (BRs) against various opponent policies from the training set (Itrain). These BRs, along with the sampled opponent policies, generate training data for a Transformer model with three components: an actor (πθ), opponent imitator (μφ), and critic (Vw). These components are trained using in-context learning (ICL). The right side shows the testing phase, where the pretrained components are utilized for decision-time search (DTS) to refine the actor’s policy. The DTS involves multiple L-step rollouts for each legal action and a mixing technique to balance the search policy and the original actor policy.

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative evaluation of the learned dynamic transition model P’s performance in estimating the next state and reward during testing. The results are broken down by environment (Predator Prey, Level-Based Foraging, Overcooked) and different ratios of seen to unseen opponent policies in the test set (10:0, 10:5, 10:10, 5:10, 0:10). The evaluation metrics used are the average mean squared error (MSE) for the next state prediction and the average MSE for the reward prediction. The E = 20 parameter refers to the frequency of opponent policy switches during testing.

This table presents a quantitative analysis of the learned transition dynamics model P’s performance during the testing phase. It shows the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) for next state and reward prediction across different ratios of seen and unseen opponent policies in the testing set. The results highlight how well the model generalizes to unseen opponents.

Full paper#