↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many neuroscience studies use optogenetics to study neural circuits’ effects on behavior. However, current analytical methods often overlook crucial information and may produce biased results, especially in ‘closed-loop’ designs where treatment is dynamically assigned based on observed responses. This limits scientific questions that can be addressed and leads to incomplete understanding of causal relationships.

This research paper introduces a new statistical approach, history-restricted marginal structural models (HR-MSMs), to address these issues. HR-MSMs enable rigorous estimation of various causal effects, including complex sequential effects, directly handling dynamic treatment regimes and positivity violations. The study demonstrates the method’s effectiveness on real-world optogenetics data, unveiling previously hidden effects and significantly improving the accuracy and depth of causal inference in this field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for neuroscience researchers using optogenetics because it introduces a novel causal inference framework. It addresses limitations of existing methods, enabling more precise analysis of complex experimental designs and the discovery of subtle effects previously obscured by standard methods. This directly impacts the quality and interpretability of neuroscience research. The proposed approach is statistically rigorous and has efficient computational implementation, making it readily applicable to existing datasets. It opens doors for more nuanced investigation into the micro-level causal effects of neurostimulation.

Visual Insights#

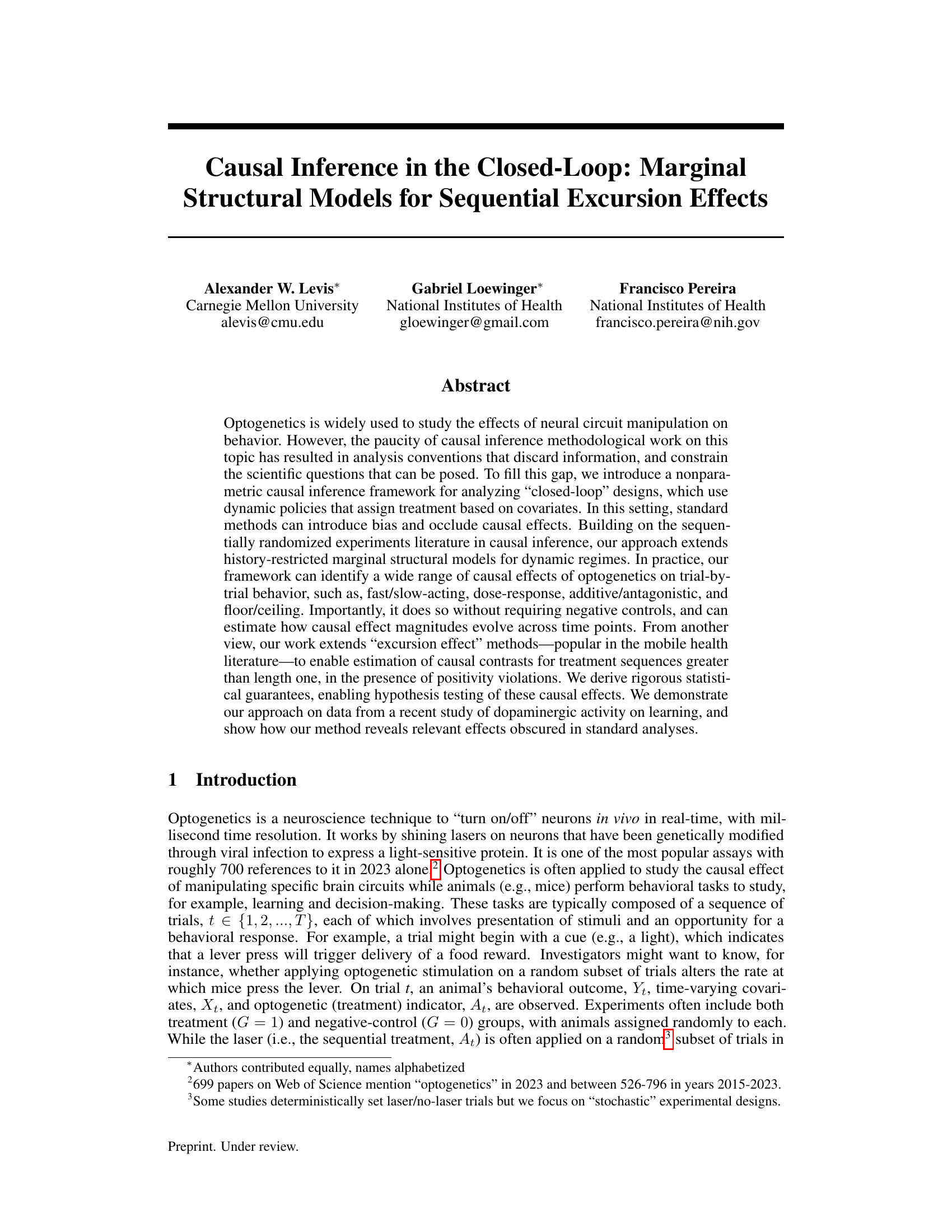

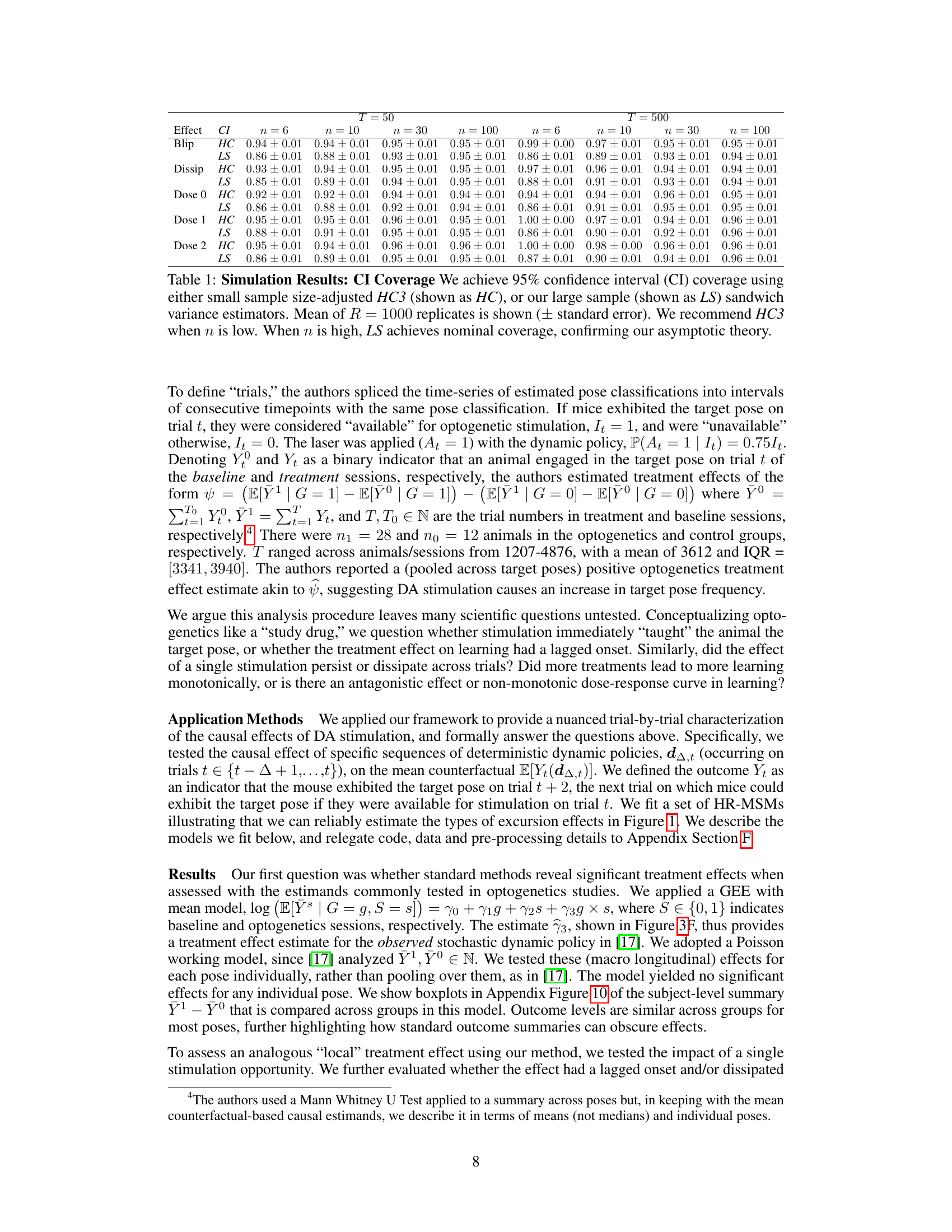

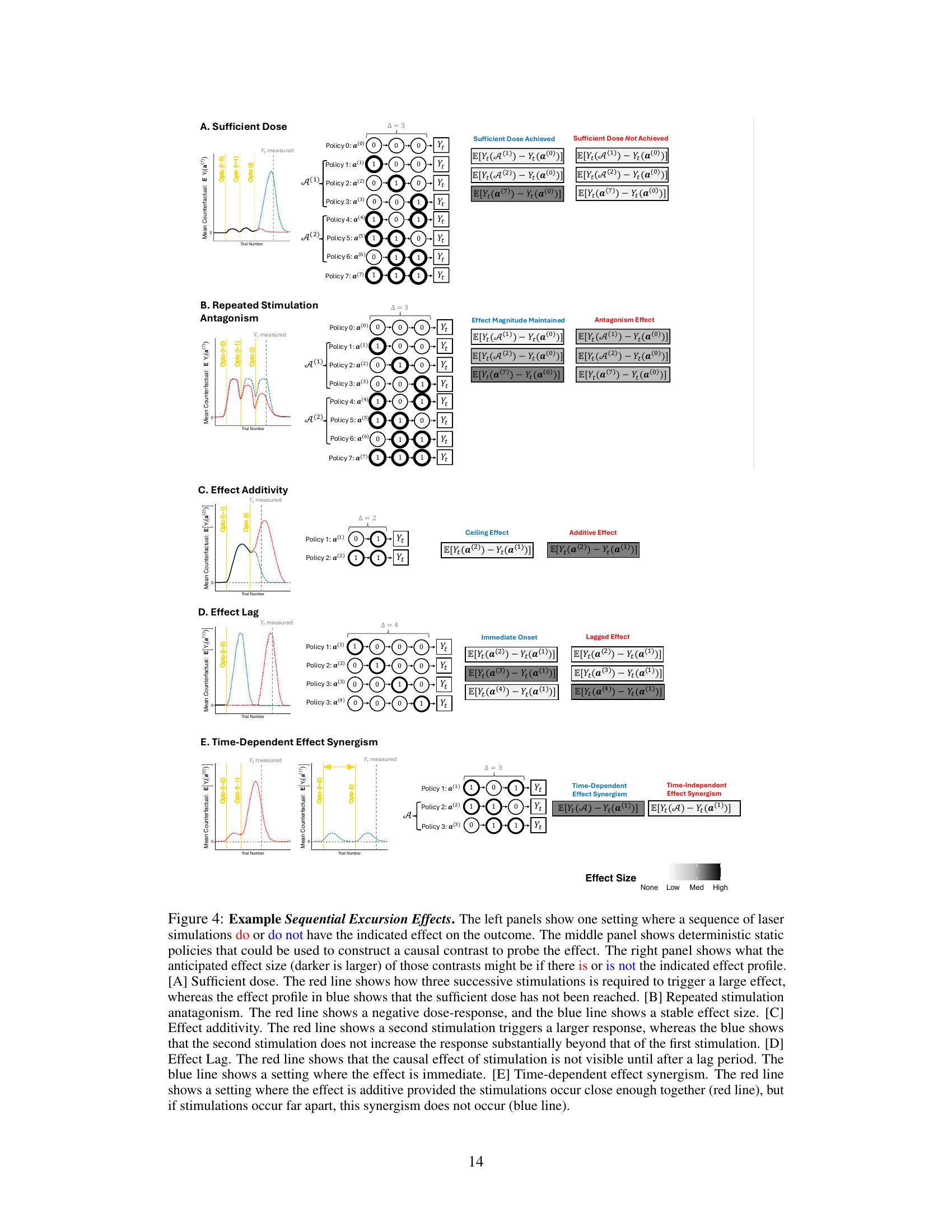

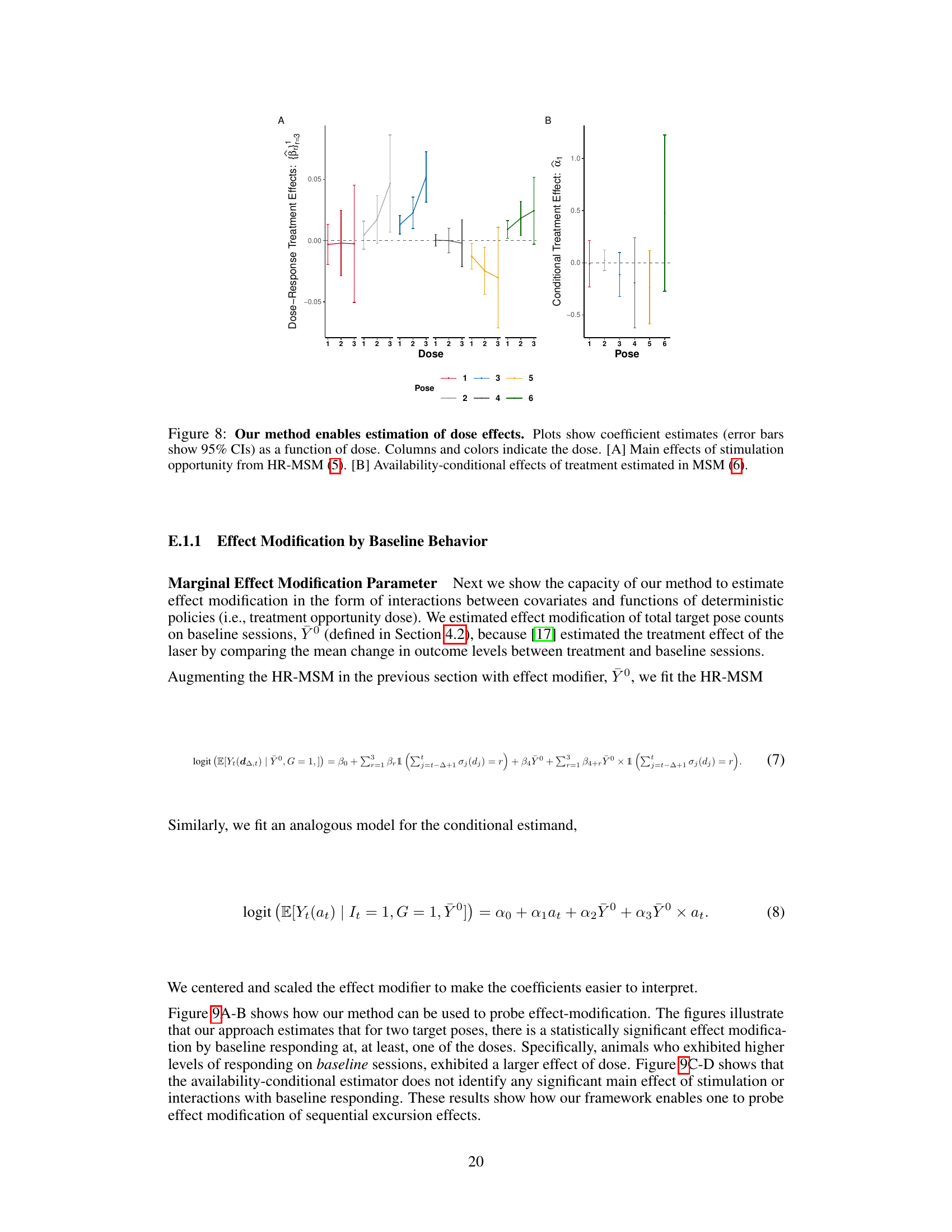

This figure illustrates different types of sequential excursion effects that can be identified using the proposed method. Panels A-C show examples of blip effects (single stimulation), effect dissipation (effect duration), and dose-response effects (increasing stimulation). Panel D presents a directed acyclic graph (DAG) representing a closed-loop experimental design where treatment depends on past outcomes. Panel E demonstrates a history-restricted marginal structural model (HR-MSM), a statistical model for estimating causal effects in sequential settings.

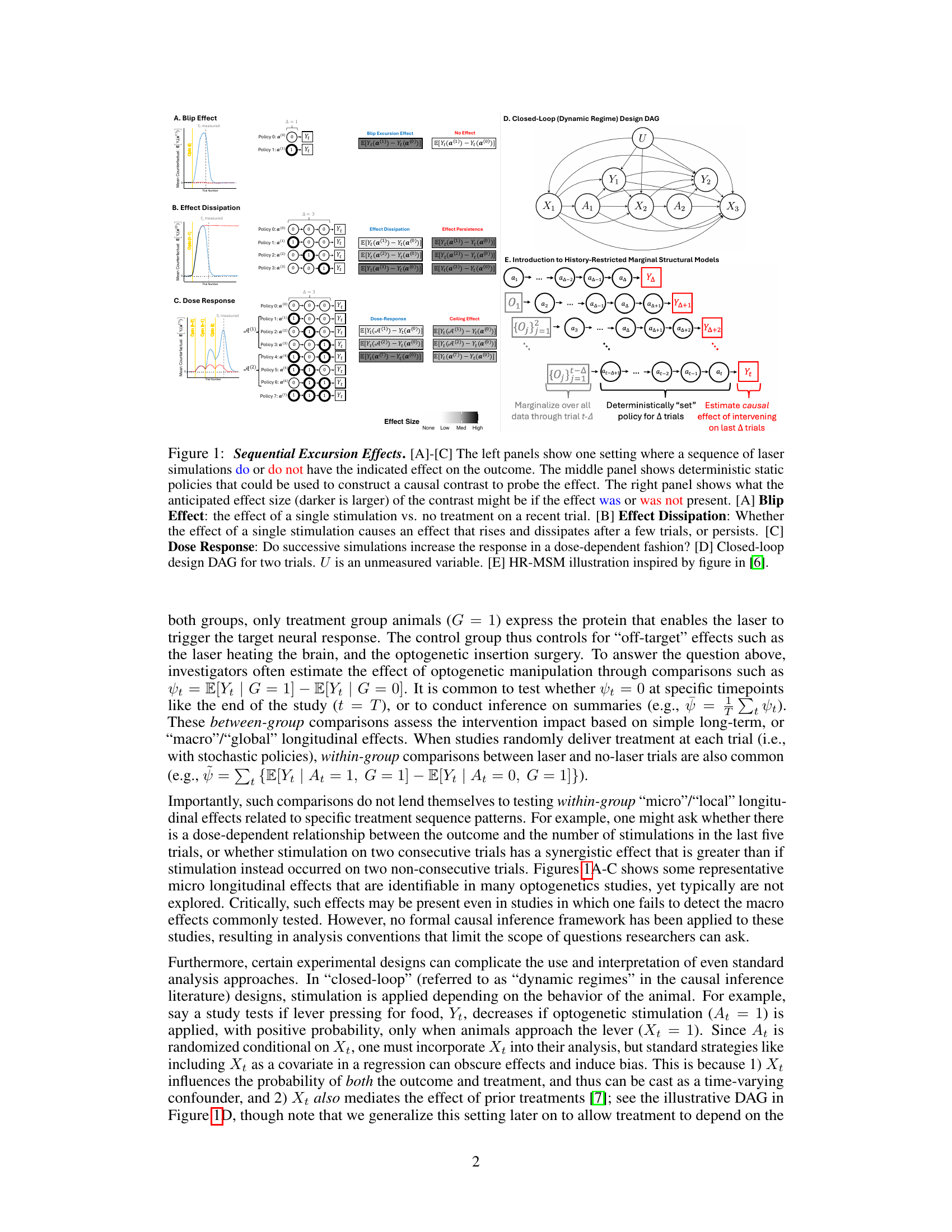

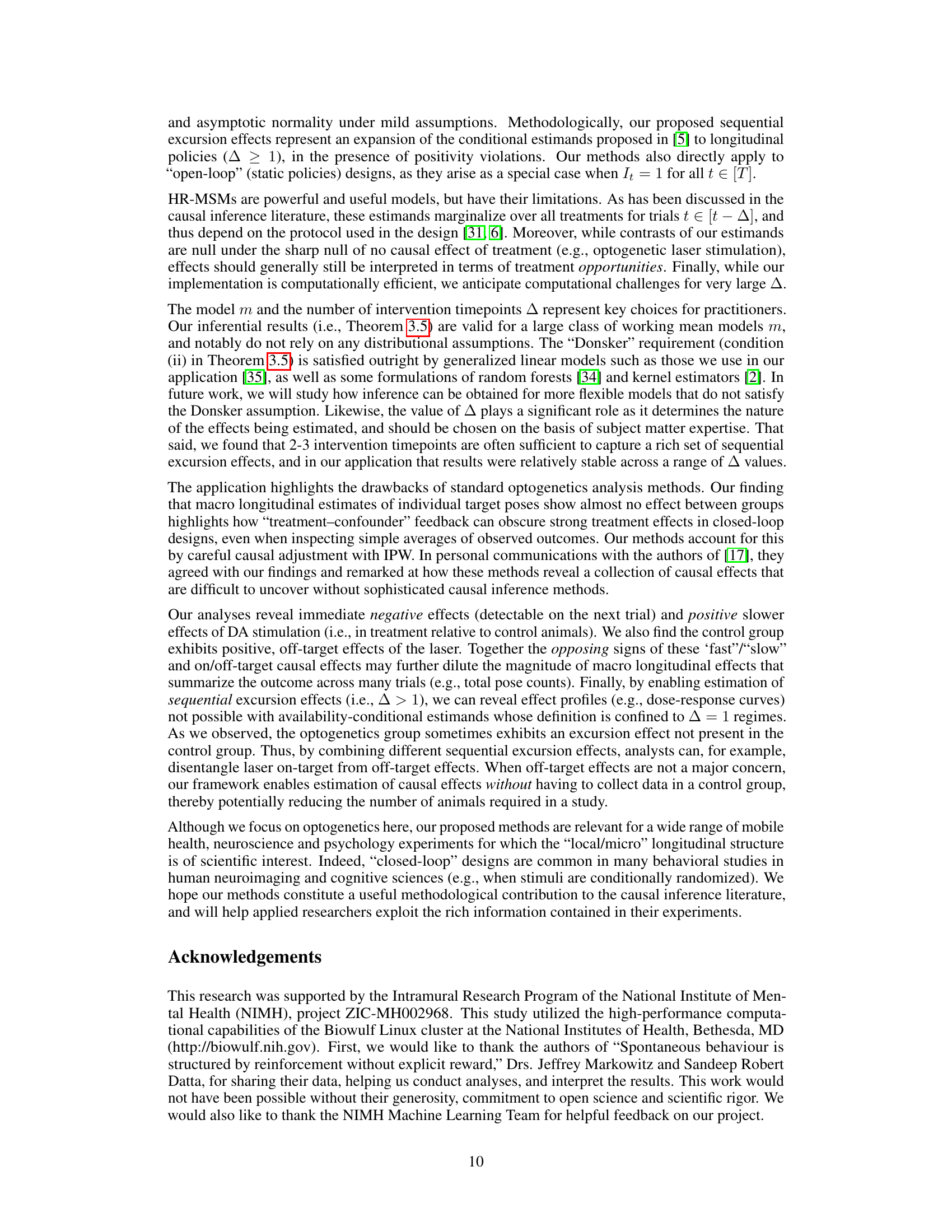

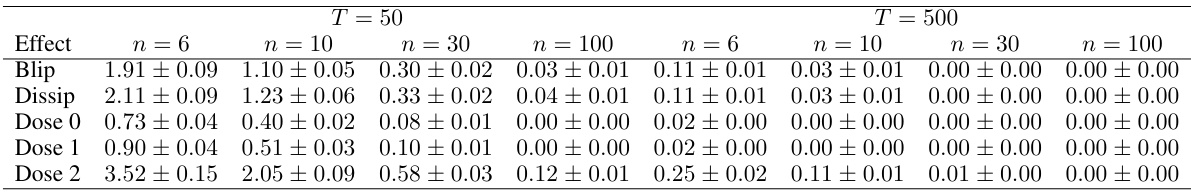

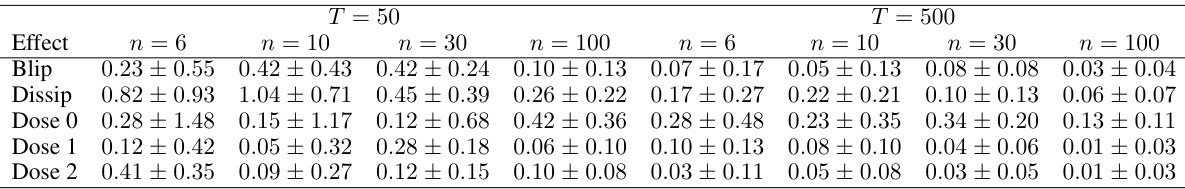

This table presents the results of simulation studies evaluating the performance of the proposed estimator and the associated confidence intervals for various sample sizes (n) and numbers of trials (T). It shows the 95% confidence interval coverage for three different robust variance estimators (HC, HC2, HC3) and a large sample variance estimator (LS) across different sequential excursion effects (Blip, Dissipation, Dose 0, Dose 1, Dose 2). The results demonstrate the consistency of the estimator and the validity of the confidence intervals, particularly for larger sample sizes.

In-depth insights#

Causal Excursion#

The concept of “Causal Excursion” in a research paper likely refers to the investigation of how a cause’s effect propagates and evolves over time, considering the dynamic interplay of various factors. It goes beyond a simple cause-and-effect relationship by exploring the sequential nature of influence. A key aspect would be discerning whether the initial causal effect persists, dissipates, or even reverses its direction over time. The analysis likely involves examining temporal patterns and dependencies to reveal the intricate causal pathways involved, potentially using statistical techniques like time series analysis or dynamic causal modeling. The study’s strength lies in its ability to uncover subtle, nuanced effects that might be missed by analyses focusing solely on the immediate, short-term outcomes. For example, in a medical setting, it would shed light on how a treatment’s impact unfolds not only in the short term, but also how that impact may fluctuate and change over a longer period of treatment. The findings would likely be richer in detail and valuable in understanding complex systems’ responses to external stimuli.

Optogenetic Design#

Optogenetic designs, employing light-sensitive proteins to manipulate neural circuits, present unique challenges for causal inference. The closed-loop nature of many optogenetic experiments, where stimulation is dynamically adjusted based on behavioral responses, introduces complexities not found in traditional randomized controlled trials. Standard statistical methods are often insufficient to disentangle direct effects of stimulation from confounding variables, which leads to potential bias and inaccurate conclusions about the causal relationships involved. The choice of stimulation parameters, including the timing, duration, and intensity of light pulses, critically determines the specific aspects of neural function being investigated and must be carefully considered in relation to the research question. Researchers must carefully define their experimental treatment protocols, considering the temporal dynamics of neural activity and potential carry-over or interaction effects between treatments. Furthermore, positivity violations, where certain treatment sequences are impossible due to experimental constraints or ethical considerations, can further complicate causal inference in these designs. Therefore, a rigorous and adaptable analytical framework, such as those based on marginal structural models or other advanced causal methods, is necessary for robust causal inference in optogenetic experiments. Future work should focus on expanding these methods to effectively address issues arising from dynamic stimulation policies and positivity violations to generate a more comprehensive understanding of neural circuit function.

HR-MSM Analysis#

The heading ‘HR-MSM Analysis’ suggests a section detailing the application of History-Restricted Marginal Structural Models. This statistical technique is likely employed to analyze longitudinal data, specifically focusing on the causal effects of time-varying treatments. Given the context of a research paper, this analysis likely involves estimating the effects of treatment sequences, handling time-varying confounders, and addressing potential positivity violations which are common in dynamic treatment regimes. Key aspects of the analysis likely include model specification (choosing appropriate functional forms for the outcome and treatment effects), estimation of model parameters using methods like inverse probability weighting (IPW), and assessment of the robustness and validity of the causal estimates. The analysis would likely present estimates of causal effects for specific treatment sequences, potentially examining dose-response relationships, interactions with covariates, and assessing whether effects persist or dissipate over time. The results would likely be presented with confidence intervals to quantify uncertainty and statistical significance testing to evaluate the credibility of the findings. Interpreting these results requires careful consideration of the study design, potential limitations of the model, and the specific context of the research question. It is crucial to note that the limitations of the HR-MSM method, such as sensitivity to the posititvity assumption, should be thoroughly addressed.

Limitations & Gaps#

The paper’s limitations center on the scope of causal effects estimable given the study design and the focus on specific types of optogenetics experiments. The reliance on history-restricted marginal structural models (HR-MSMs) introduces assumptions that may not always hold true in real-world applications. The methodological framework’s ability to handle positivity violations is limited to certain situations, and the need for large datasets for robust inference is also highlighted. There is an inherent trade-off between bias and variance, especially in small sample sizes. The authors acknowledge a need for further investigation into the generalizability of the framework beyond the specific types of optogenetics experiments considered. Computational challenges are expected for very long treatment sequences. Finally, the research is limited to animal data and doesn’t explicitly address issues of privacy or fairness that could arise in human applications.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the HR-MSM framework to handle more complex treatment scenarios, such as those involving multiple interacting neural circuits or non-deterministic policies, would significantly broaden its applicability. Investigating the effects of different stimulation protocols, including frequency, duration, and timing, is crucial for gaining a deeper understanding of the causal mechanisms underlying optogenetic manipulations. Developing more robust methods for handling positivity violations in closed-loop designs would further enhance the reliability of causal inference. Combining the HR-MSM framework with machine learning techniques to extract higher-level patterns and insights from complex behavioral data is another valuable direction. Finally, applying these refined methods to different animal models and behavioral tasks could unlock novel insights into the neural underpinnings of behavior and learning. The development of user-friendly software tools integrating these advanced methods would greatly facilitate wider adoption within the neuroscience community.

More visual insights#

More on figures

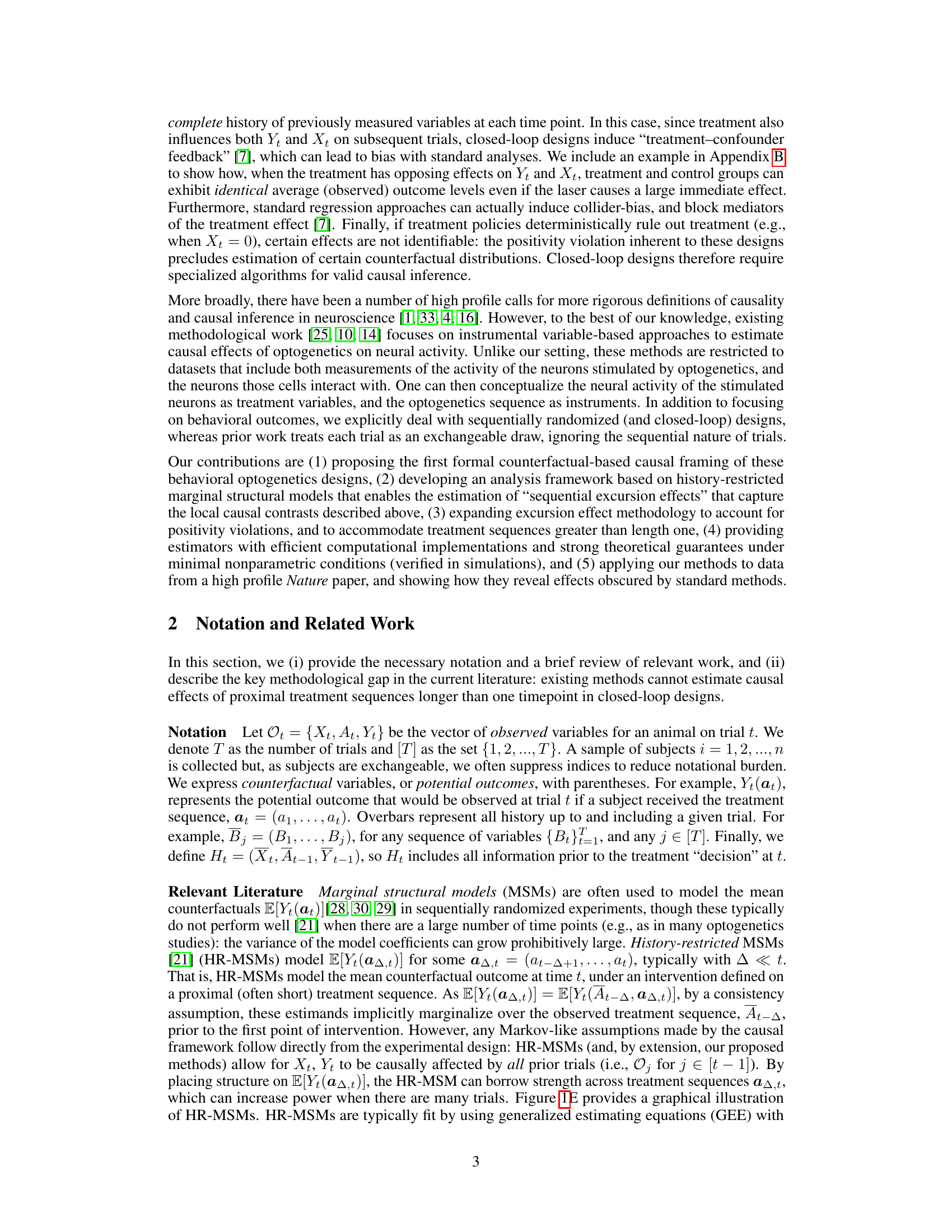

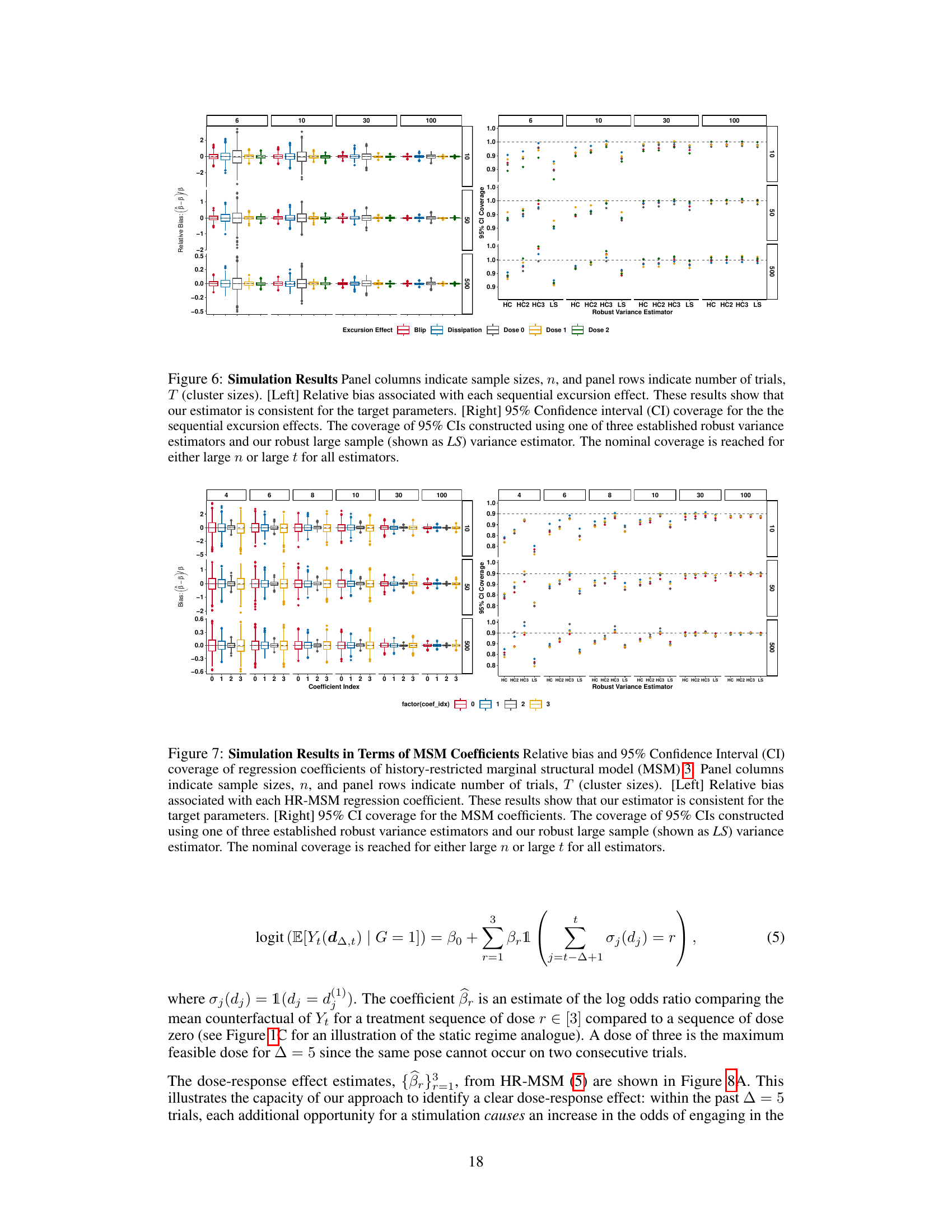

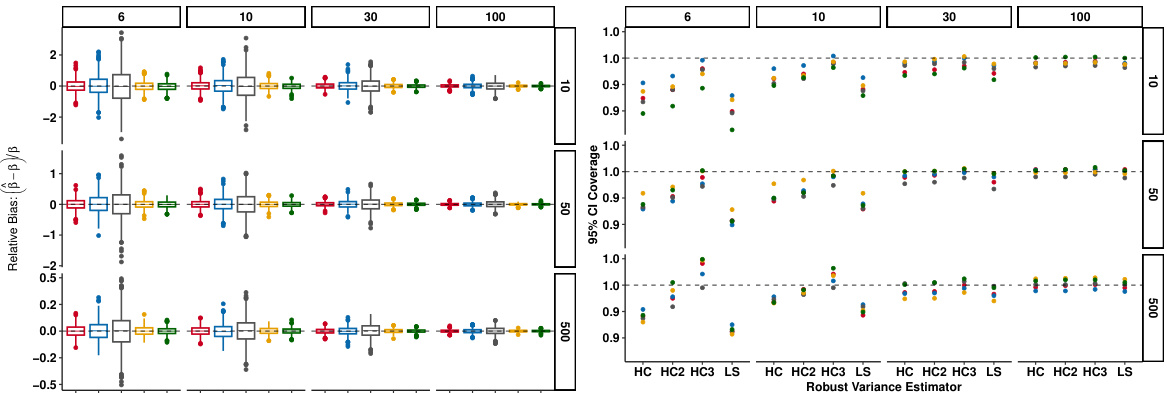

This figure displays the results of simulation studies conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed estimator and its associated confidence intervals. The left panel shows the relative bias for each sequential excursion effect across different sample sizes (n) and trial numbers (T). The right panel shows the 95% confidence interval coverage for these effects using different variance estimators. The results demonstrate the estimator’s consistency and the achievement of nominal coverage, particularly with larger sample sizes or numbers of trials.

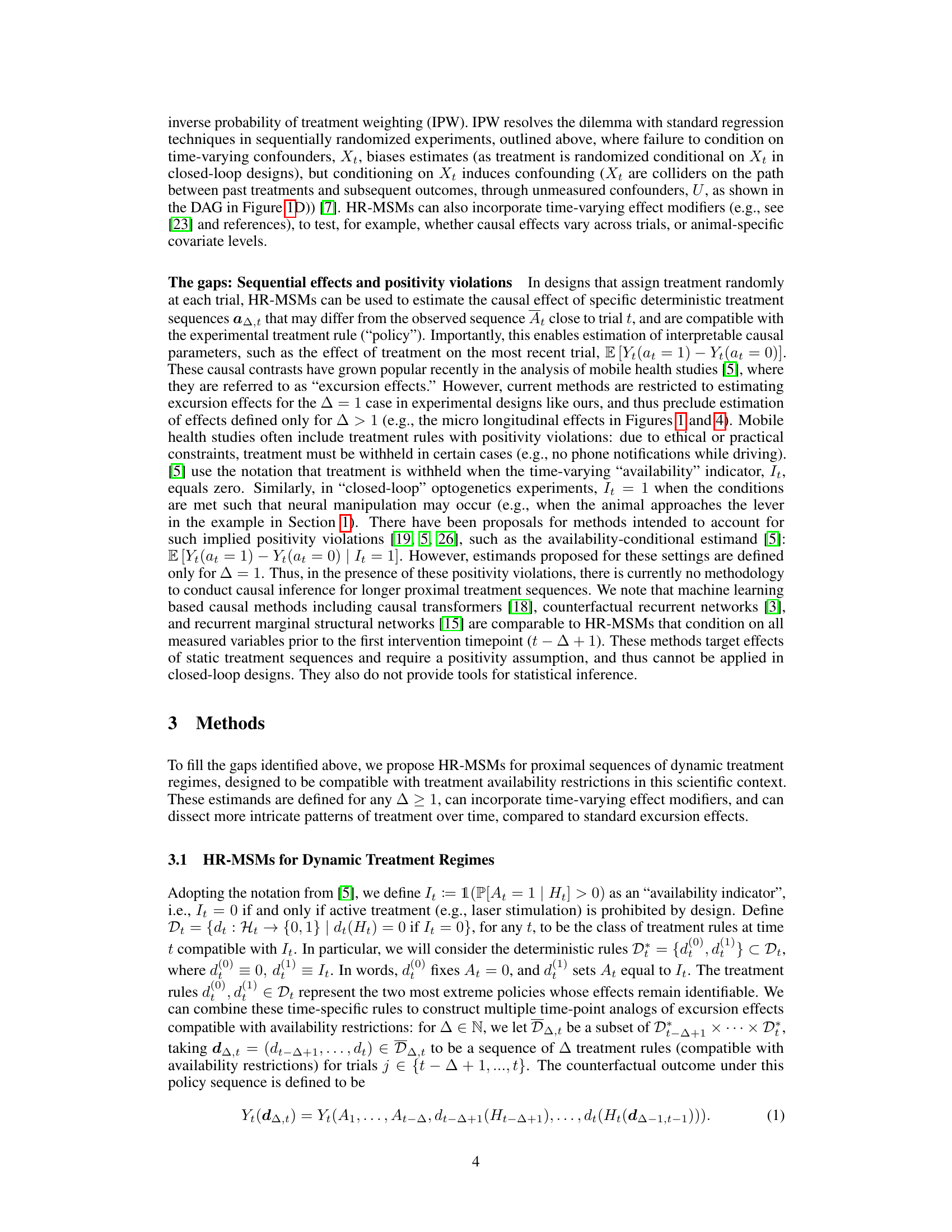

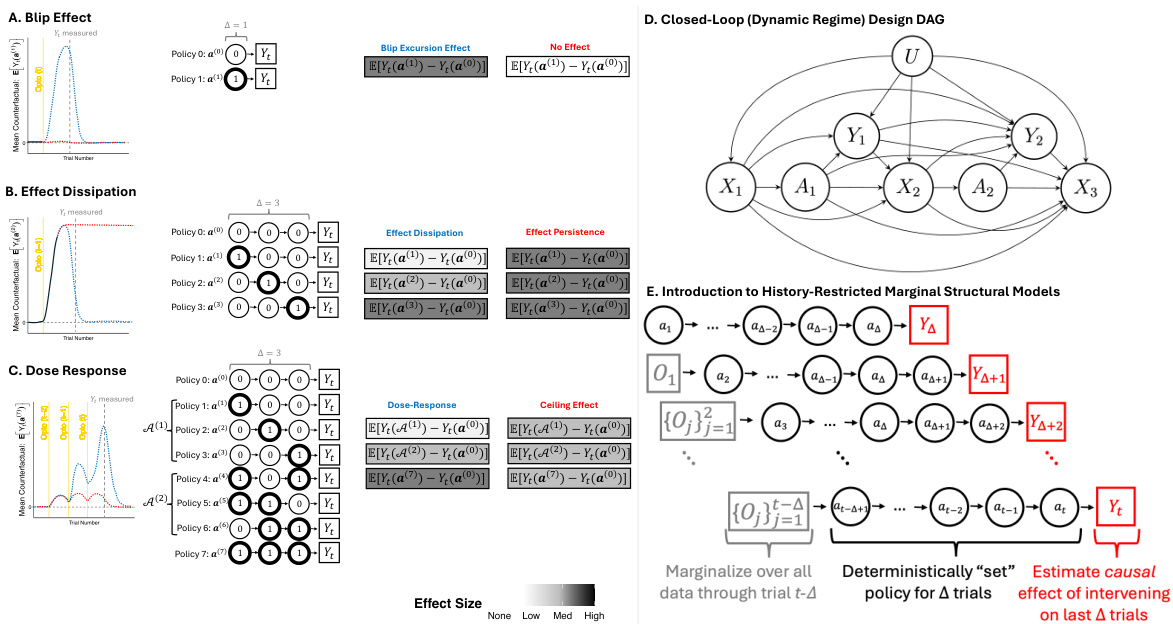

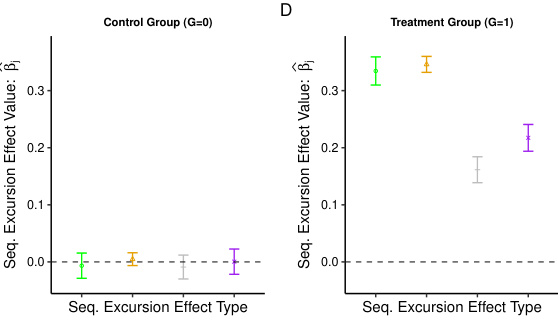

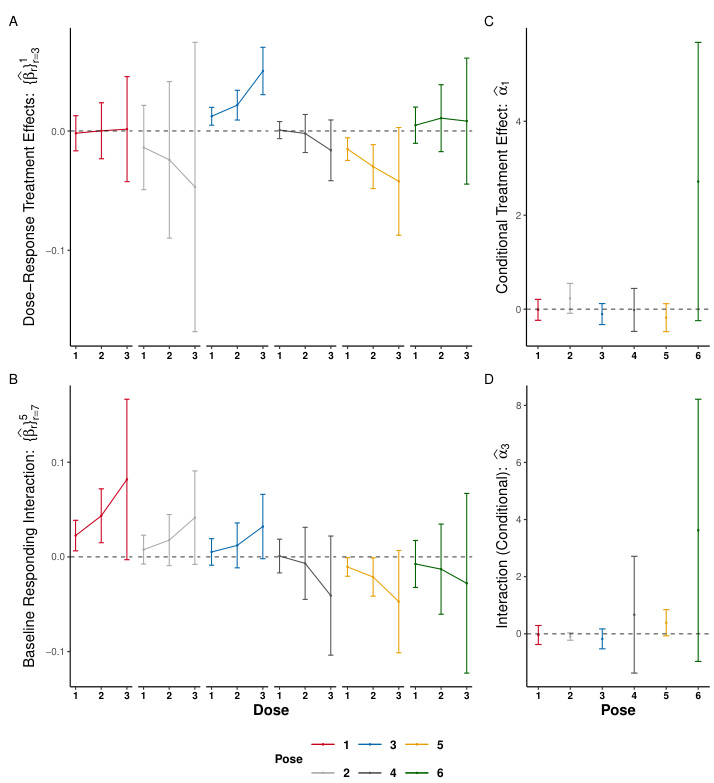

Figure 3 presents the results of the optogenetics study. Panel A displays interaction terms between group (G) and the sequential excursion effects of laser stimulation on trials prior to the outcome. Panel B shows the availability-conditional interaction between laser (A) and group (G). Panel C shows the main effects of group G when there were no recent treatment opportunities and Panel D shows the macro longitudinal analysis, similar to the one in the original paper.

This figure illustrates different types of causal effects that can be identified in optogenetics studies using the proposed method. Panel A shows a ‘Blip Effect,’ where a single stimulation has an immediate effect. Panel B shows ‘Effect Dissipation,’ where an effect diminishes over time. Panel C shows a ‘Dose Response,’ where the effect increases with the number of stimulations. Panel D shows a directed acyclic graph (DAG) representing a closed-loop design for two trials. Panel E shows a simplified illustration of a history-restricted marginal structural model (HR-MSM).

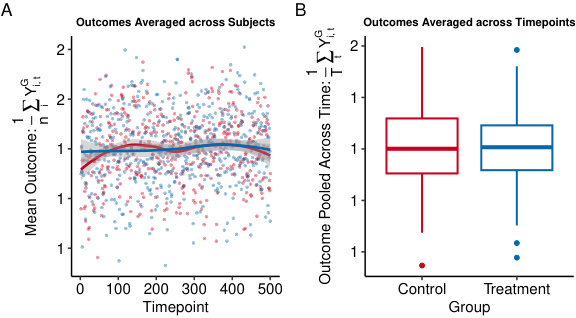

This figure demonstrates a scenario where treatment-confounder feedback leads to cancellation of treatment effects in ‘macro’ summaries (averaged across subjects or timepoints). However, using the proposed sequential excursion effects reveals causal effects within the treatment group that are obscured in the macro-level summaries.

This figure demonstrates how treatment-confounder feedback can obscure causal effects in standard analyses that summarize data across trials or subjects. In a simulated experiment, the authors show that while standard “macro” summaries show no difference between treatment and control groups, their method, which examines causal effects within specific sequences of trials (sequential excursion effects), reveals significant effects within the treatment group.

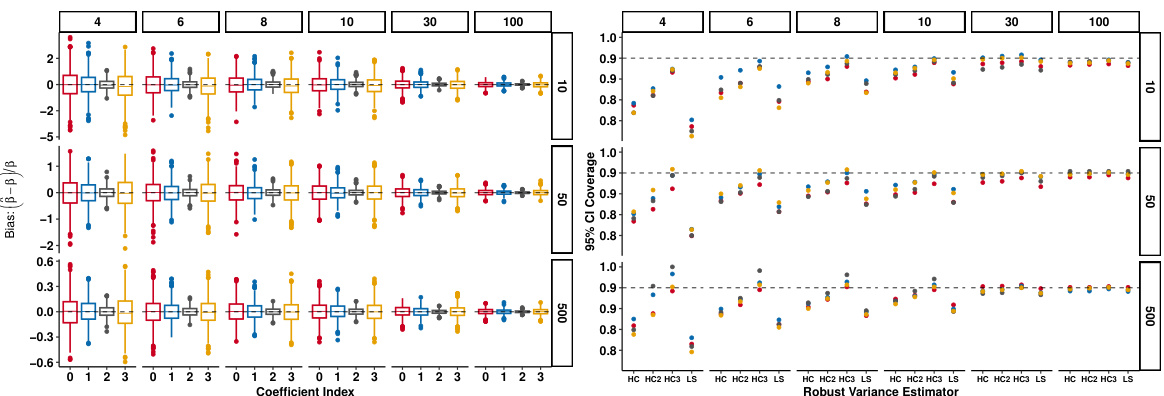

This figure displays simulation results evaluating the performance of the proposed estimator for sequential excursion effects. The left panel shows the relative bias of the estimator for different sample sizes (n) and numbers of trials (T), indicating consistency with the target parameters. The right panel illustrates the 95% confidence interval coverage for various variance estimators. The results demonstrate that the proposed estimator achieves nominal coverage for sufficiently large sample sizes or numbers of trials.

This figure displays the results of simulation studies evaluating the performance of the proposed estimator for sequential excursion effects. The left panel shows the relative bias for different sample sizes (n) and trial numbers (T), demonstrating the estimator’s consistency. The right panel illustrates the 95% confidence interval coverage for three established robust variance estimators and a large sample variance estimator, confirming that the nominal coverage is achieved for sufficiently large n or T.

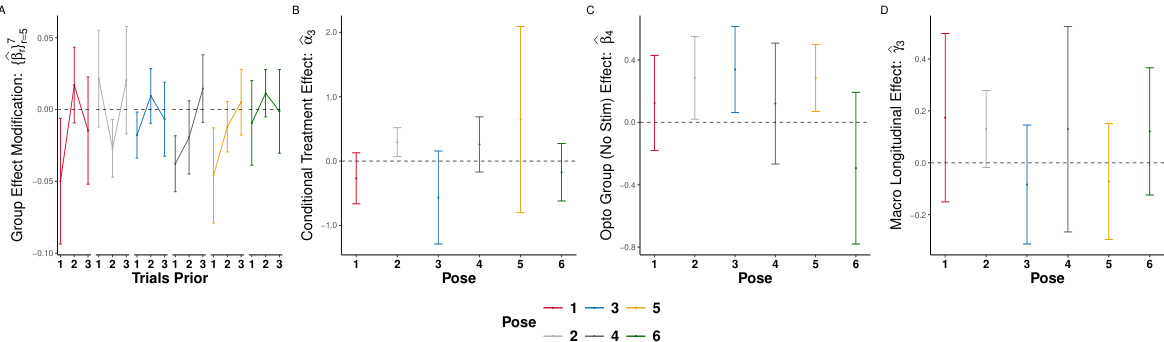

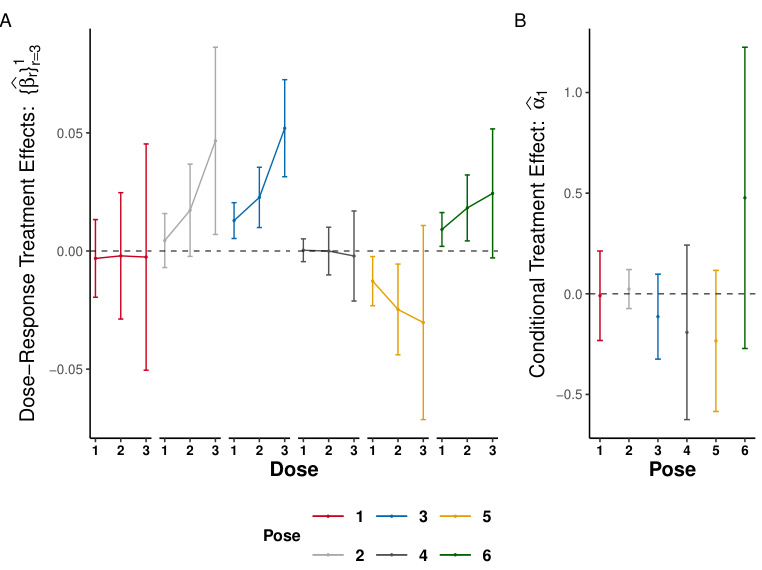

This figure shows the dose-response effects of optogenetic stimulation on the probability of the animal exhibiting a target pose. Panel A shows the main effects of stimulation opportunities, estimated using a history-restricted marginal structural model (HR-MSM). Panel B shows the availability-conditional effects of treatment, estimated using a marginal structural model (MSM). The results show that our method can estimate dose-response effects and that the effects of stimulation depend on the availability of the treatment.

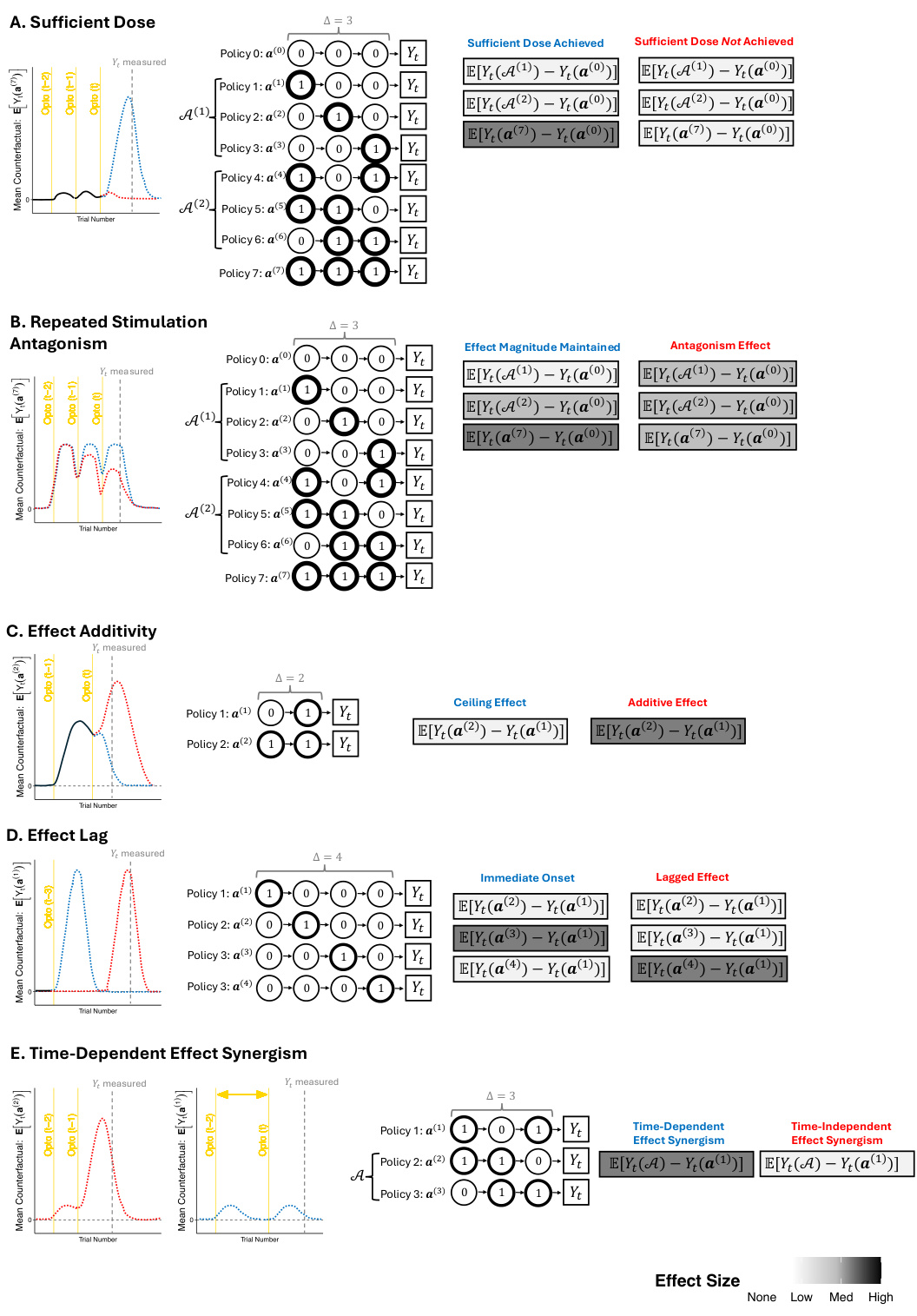

This figure shows five examples of sequential excursion effects that can be analyzed using the proposed method. Each panel illustrates a different type of effect: sufficient dose, repeated stimulation antagonism, effect additivity, effect lag, and time-dependent effect synergism. For each effect, the figure shows a sequence of laser stimulations (or lack thereof), the resulting outcome, and a graphical representation of the effect size.

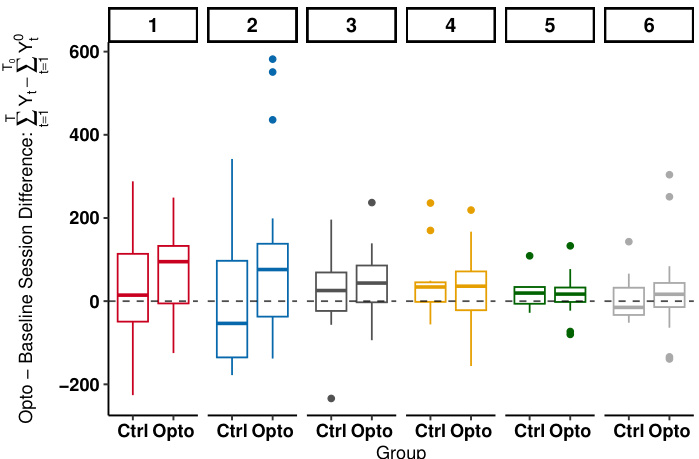

This figure shows boxplots of the difference in the total number of target poses between the treatment and baseline sessions for each of the six poses. Each point in the boxplot represents a single animal. The x-axis shows the group (control or treatment) and pose. The y-axis shows the difference in the total number of target poses between the treatment and baseline sessions. The figure shows that there is a significant difference in the total number of target poses between the treatment and baseline sessions for some poses. This suggests that optogenetic stimulation had an effect on the frequency of target poses.

More on tables

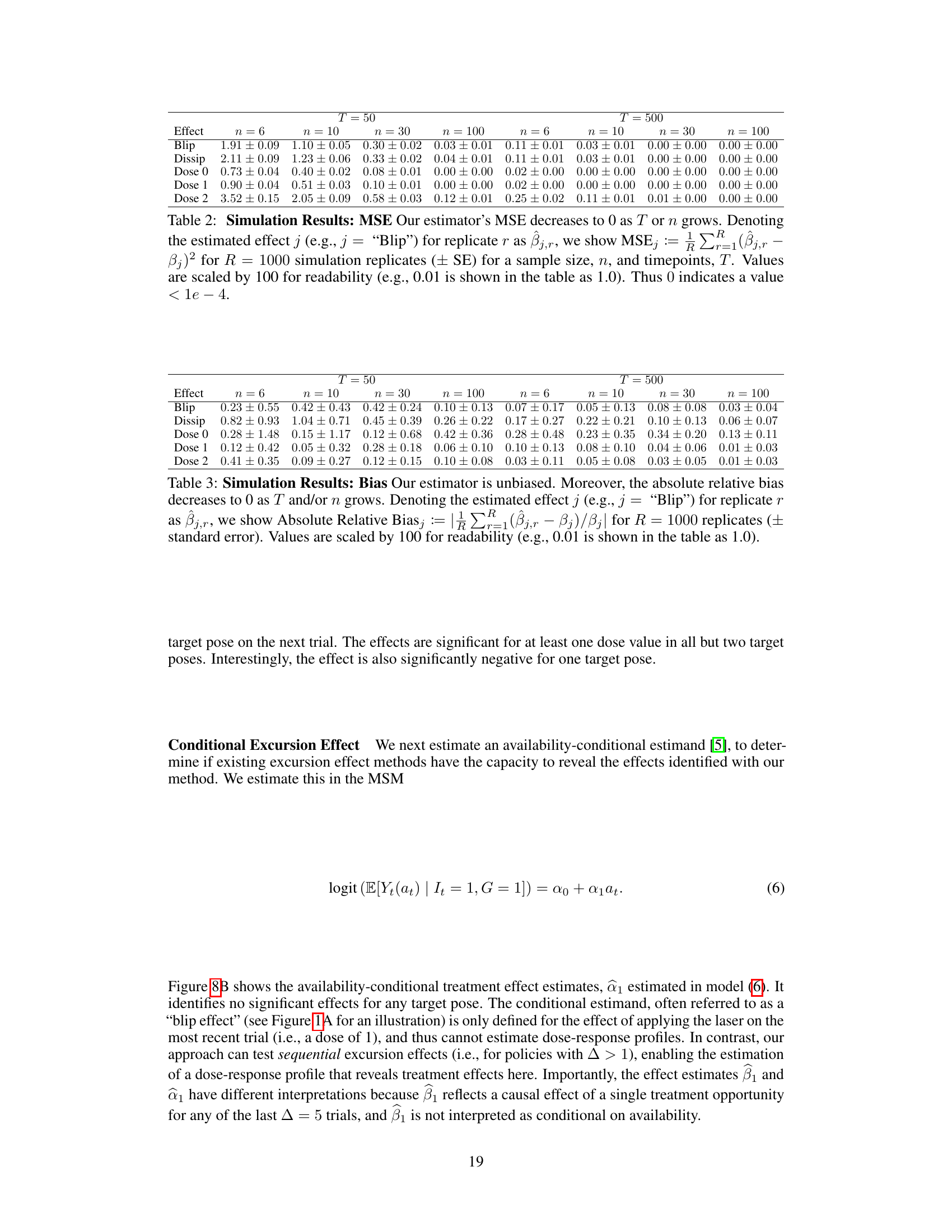

This table presents the results of simulation studies conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed estimator and its associated confidence intervals. The table shows the 95% confidence interval coverage for three different sequential excursion effects (Blip, Dissipation, and Dose) across various sample sizes (n = 6, 10, 30, 100) and numbers of trials (T = 50, 500). Two different variance estimators, HC3 (small sample size-adjusted) and LS (large sample), were used, and their performance is compared.

This table presents the mean squared error (MSE) of the proposed estimator for different sample sizes (n) and numbers of trials (T). The MSE is calculated for three types of sequential excursion effects (Blip, Dissipation, Dose 0, Dose 1, and Dose 2) across 1000 simulation replicates. The values are scaled for readability, with 0 indicating a value less than 1e-4. The results show that the MSE decreases as either the sample size or the number of trials increases, indicating the consistency of the estimator.

Full paper#