TL;DR#

Training large Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models is computationally expensive due to significant communication overhead. Existing MoE training systems often involve extensive all-to-all communication between GPUs, accounting for a substantial portion of the total training time (45% on average in this study). This significantly hinders the efficiency and scalability of training MoE models.

The paper introduces LSH-MoE, a communication-efficient MoE training framework that leverages locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) to group similar tokens. This method transmits only the clustering centroids, significantly reducing communication costs. A residual-based error compensation scheme further enhances accuracy. Experiments demonstrate that LSH-MoE maintains model quality while substantially outperforming its counterparts across various pre-training and fine-tuning tasks with speedups ranging from 1.28x to 2.2x. This provides a solution to enhance the efficiency of MoE training, paving the way for even larger and more powerful model development.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large-scale Mixture-of-Experts models. It directly addresses the significant communication bottleneck that hinders efficient MoE training by proposing LSH-MoE, a novel framework which achieves 1.28x-2.2x speedup. This opens avenues for training even larger, more powerful MoE models, thus advancing the state-of-the-art in various deep learning tasks and providing a foundation for future research into communication-efficient model training techniques.

Visual Insights#

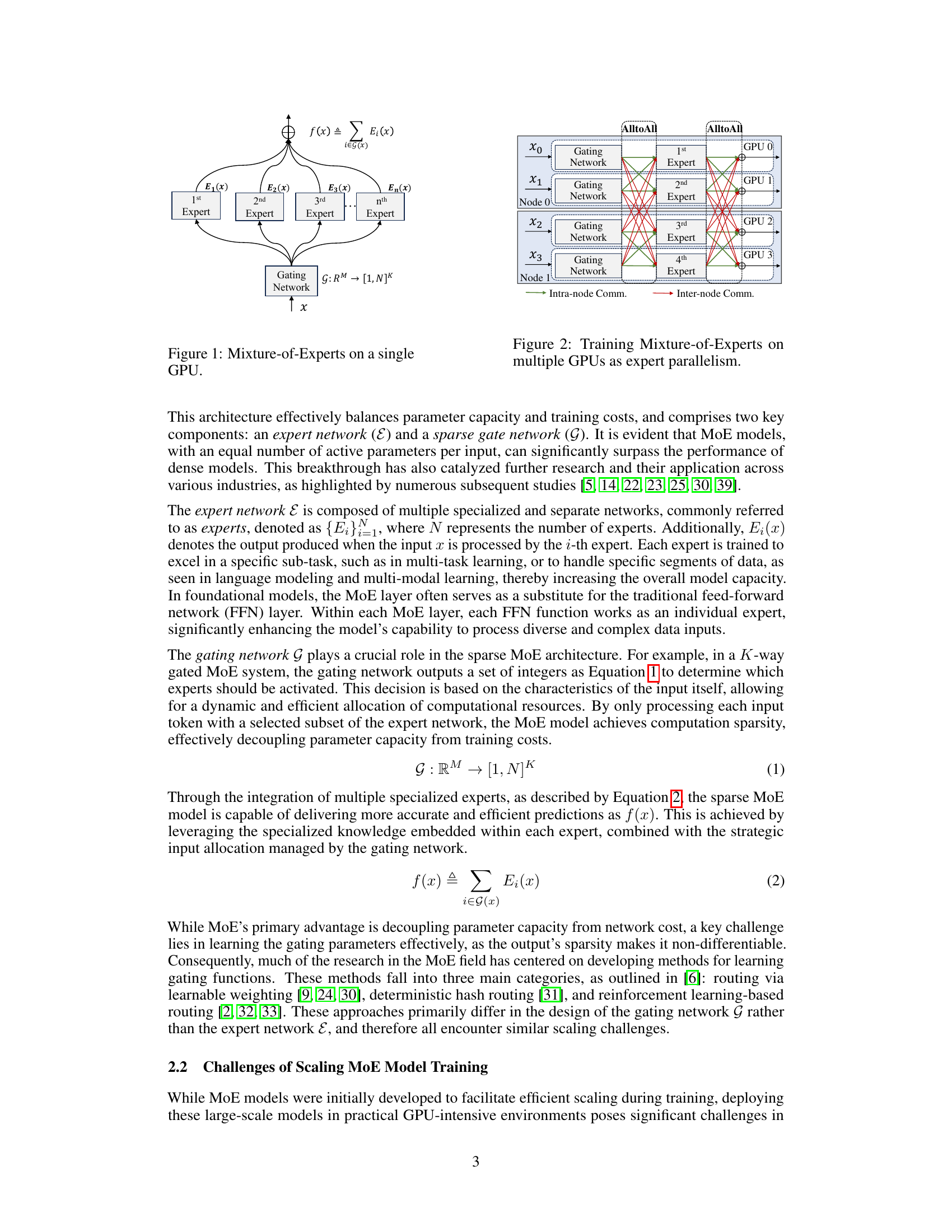

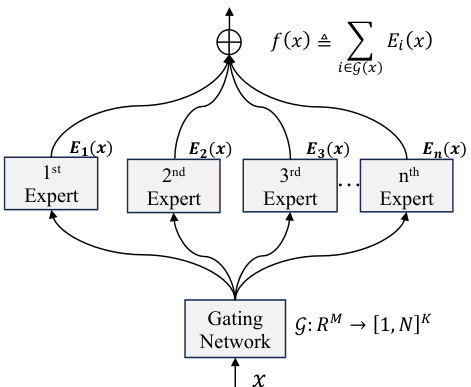

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) model on a single GPU. The input (x) is fed into a gating network, which determines which expert networks should be activated for processing that input. The gating network’s output G: RM → [1,N]K indicates the subset of experts selected, and the selected experts (E1(x), E2(x), …, En(x)) process the input and then their results are combined to produce the final output, f(x). The figure shows a single-GPU setup, illustrating the basic structure of a MoE layer.

read the caption

Figure 1: Mixture-of-Experts on a single GPU.

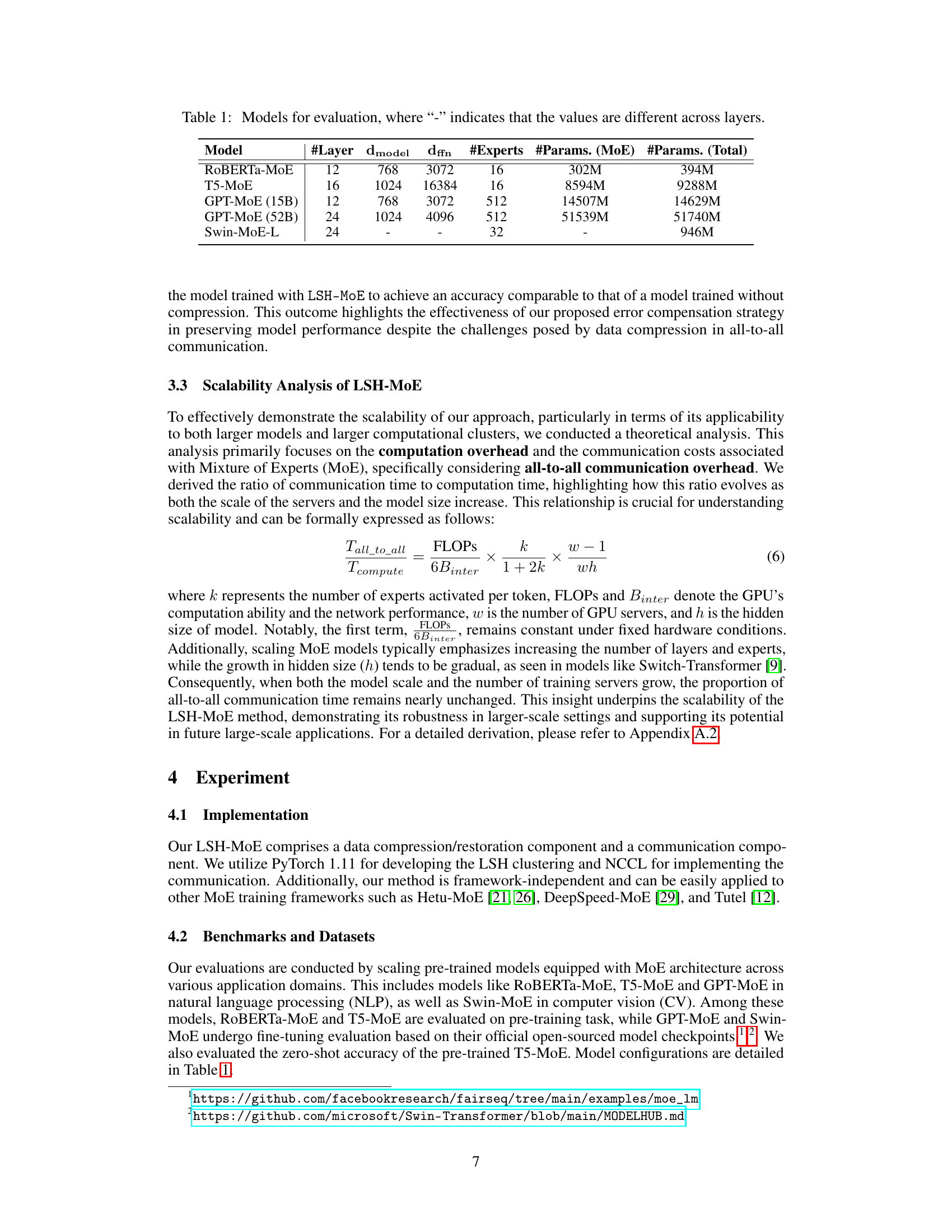

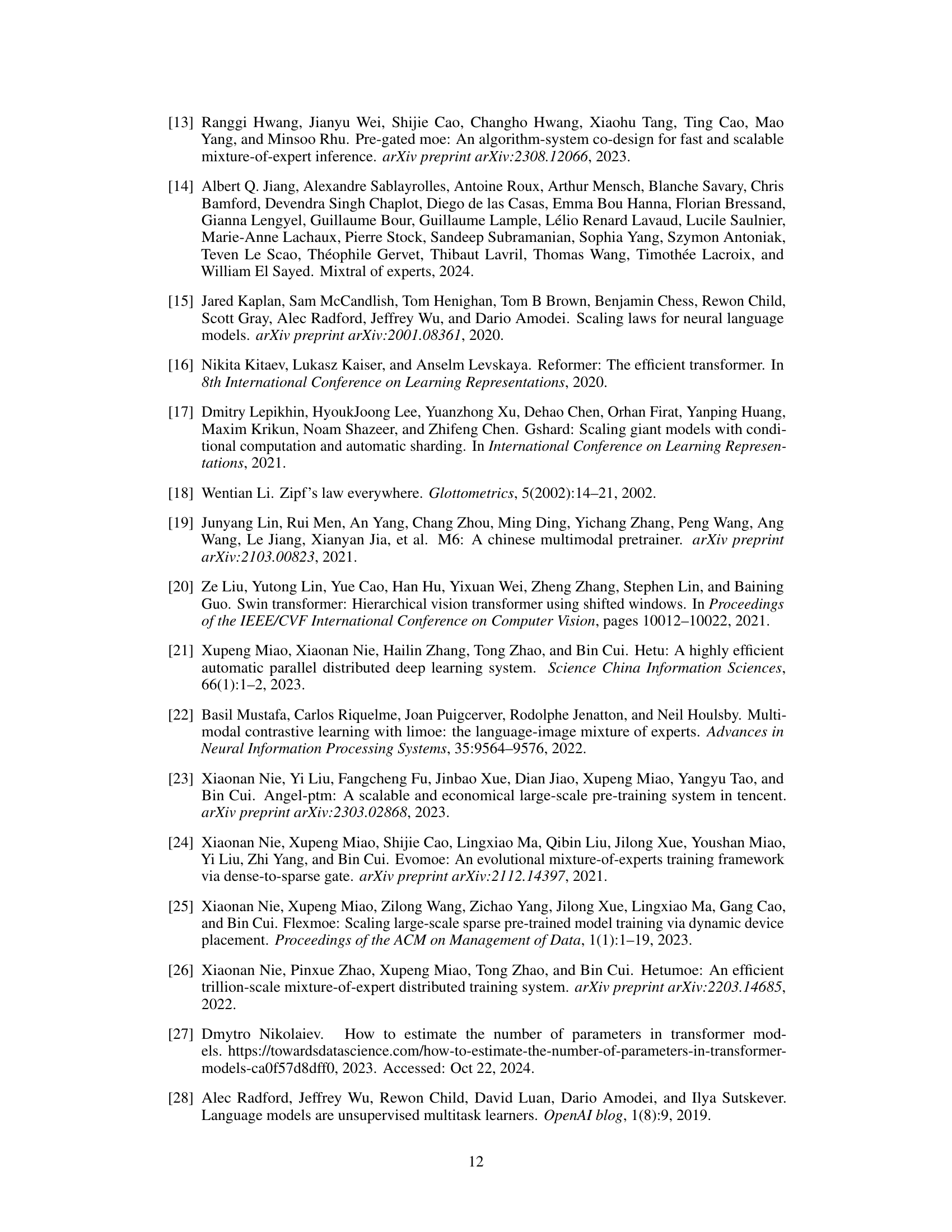

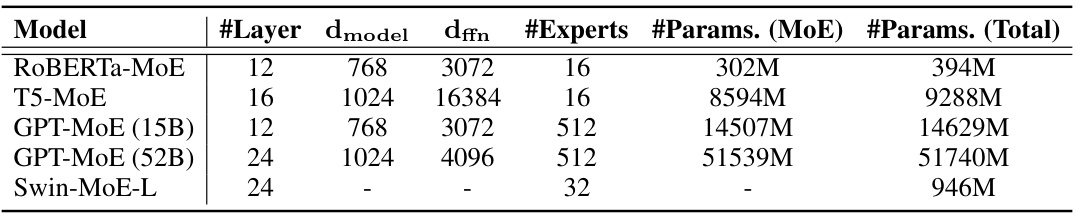

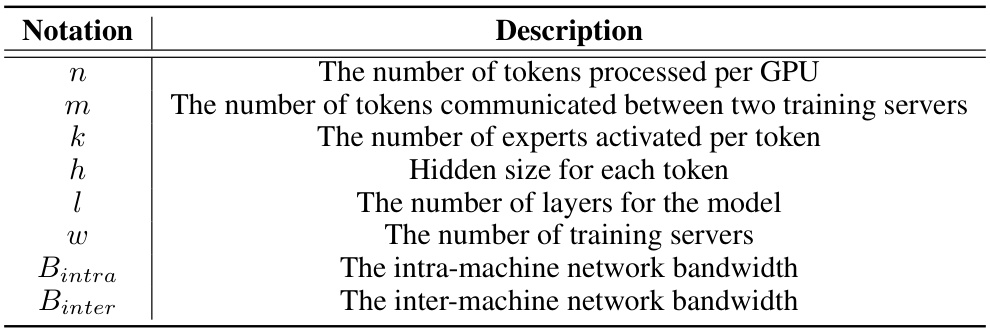

🔼 This table presents the configurations of the five different MoE models used in the paper’s experiments. For each model, it lists the number of layers, the dimension of the model (dmodel), the feed-forward network dimension (dffn), the number of experts, the number of parameters in the MoE layer, and the total number of parameters in the model. The table helps readers understand the scale and complexity of the models used in the evaluations.

read the caption

Table 1: Models for evaluation, where '-' indicates that the values are different across layers.

In-depth insights#

MoE Training Bottlenecks#

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models, while offering significant scaling potential for large language models, face substantial training bottlenecks. Communication overhead, particularly all-to-all communication between GPUs, becomes a dominant factor, consuming a significant portion of the training time—often exceeding 45% according to the paper. This is primarily due to the routing mechanism where input tokens need to be sent to specific expert networks located across different GPUs. Data sparsity, while intended to reduce computation, adds to this communication burden, as tokens need to be transferred efficiently across the distributed system. Furthermore, existing solutions often involve modifying the gating network or model architecture which hinders flexibility and universal applicability. The need for efficient data compression and strategies to minimize the impact of compression errors on model accuracy emerges as a critical challenge that needs to be addressed to fully realize the potential of MoE models.

LSH-MoE Framework#

The LSH-MoE framework presents a communication-efficient approach to Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) model training. It leverages locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) to group similar tokens, thereby significantly reducing the communication overhead inherent in large-scale MoE training. By compressing the data transmitted between GPUs, LSH-MoE mitigates the bottleneck associated with all-to-all communication, which is often a dominant factor limiting the scalability of MoE models. The framework further incorporates a residual-based error compensation scheme to counteract the potential loss of accuracy introduced by the data compression. This innovative approach enables faster training across various models, improving efficiency without sacrificing model performance. The effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments on various language and vision models, achieving substantial speedups. The use of LSH offers a promising direction in addressing the scalability challenges of MoE training, paving the way for even larger and more complex models.

Compression Efficiency#

The research paper explores compression techniques to enhance the efficiency of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) model training. A core challenge in MoE training is the significant communication overhead, primarily due to all-to-all communication patterns. The paper proposes Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) to cluster similar tokens, thereby reducing communication costs by transmitting only cluster centroids instead of all individual tokens. This LSH-based compression is further augmented by a residual-based error compensation mechanism to mitigate the loss of information incurred during compression, thus maintaining model accuracy. The results demonstrate significant speedups, suggesting that this approach successfully balances compression efficiency with the preservation of model performance. However, the paper does acknowledge potential limitations, mainly around the inherent probabilistic nature of LSH and the sensitivity to hyperparameter tuning. Future work could explore other compression strategies, refine the error compensation methods, and conduct more extensive evaluations on various model architectures and datasets to fully assess the generalizability of the proposed approach.

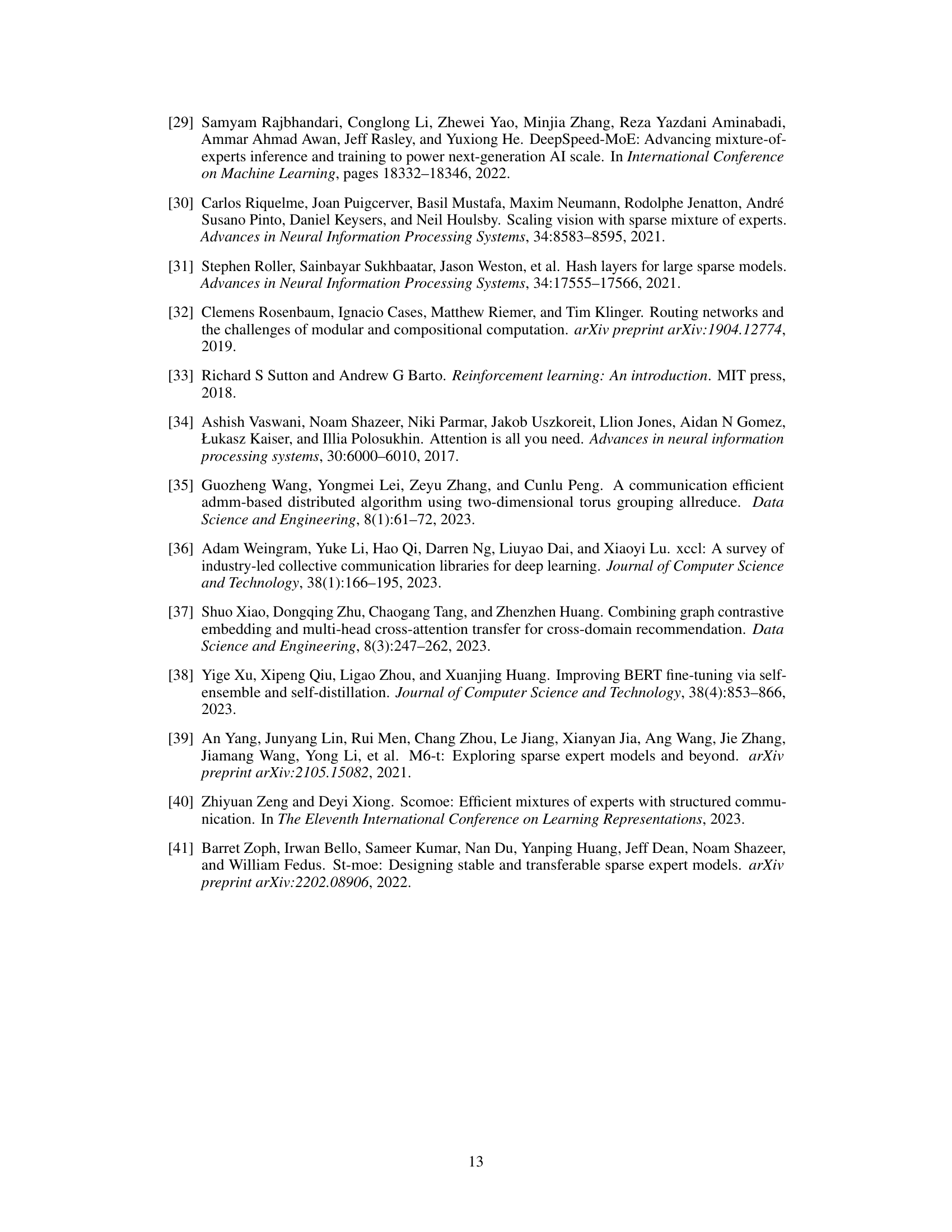

Scalability Analysis#

A robust scalability analysis is crucial for evaluating the practical applicability of any large-scale model training framework. In the context of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models, scalability is particularly challenging due to the communication overhead associated with routing data to the appropriate experts. A comprehensive scalability analysis should consider the impact of increasing both model size (number of experts, parameters) and computational resources (number of GPUs). The analysis should go beyond simply reporting scaling metrics; it needs to delve into the underlying reasons behind observed scaling behavior. For instance, it’s important to assess the relative contributions of computation and communication to overall training time. Determining the scaling properties of communication (e.g., all-to-all communication) is essential. Ideally, the analysis would provide insights into whether the proposed method’s efficiency gains are sustained as the scale of the problem increases, and identify potential bottlenecks that could limit scalability beyond a certain point. A strong analysis should also include theoretical models that predict scaling behavior, supported by experimental validation. This provides a deeper understanding of the approach’s limitations and its potential for future advancements in even larger-scale MoE training.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this LSH-MoE method could involve exploring alternative hashing techniques beyond cross-polytopes to potentially enhance compression efficiency or handle diverse data distributions more effectively. Investigating the interplay between LSH parameters (like the number of hash functions) and model performance across various MoE architectures would provide further insights into optimal configurations. Moreover, applying LSH-MoE to other model types beyond Transformers, such as CNNs or graph neural networks, could broaden its applicability and reveal potential improvements in other domains. A focus on optimizing the residual-based error compensation mechanism is warranted, potentially exploring more sophisticated error correction strategies to minimize the loss in accuracy incurred by compression. Finally, scaling the method to significantly larger models and clusters, and evaluating its performance under real-world constraints, would further validate its effectiveness and scalability for large-scale MoE model training in resource-intensive environments.

More visual insights#

More on figures

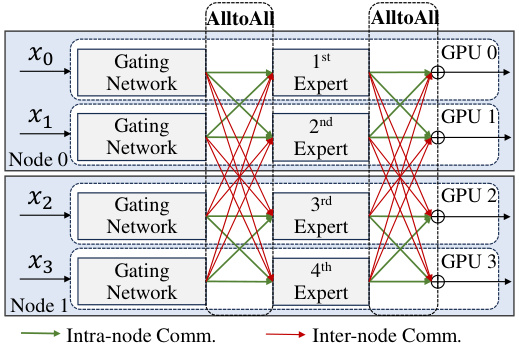

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of training a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) model using expert parallelism across multiple GPUs. The input data (tokens x0, x1, x2, x3) is first processed by a gating network on each GPU to determine which expert(s) each token should be routed to. The green arrows represent communication within a single node (GPU), while the red arrows show inter-node communication (between GPUs). All-to-all communication is required to send data to the appropriate expert GPUs and to collect results after the computations have finished. This process highlights the communication overhead associated with this training approach, which is the major focus of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training Mixture-of-Experts on multiple GPUs as expert parallelism.

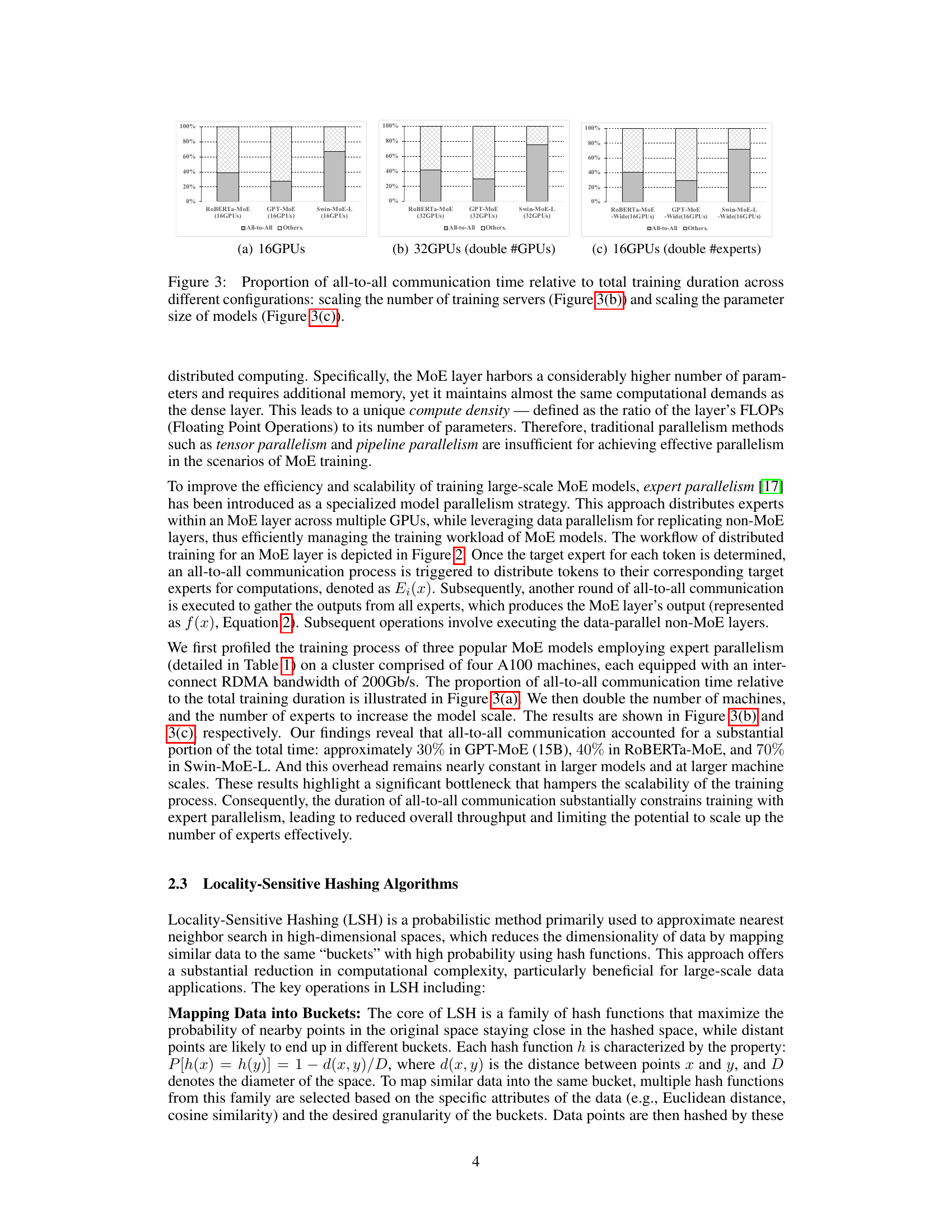

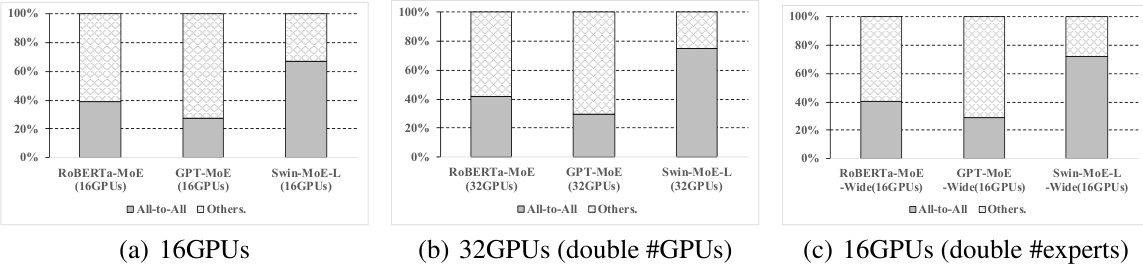

🔼 This figure shows the proportion of time spent on all-to-all communication during the training of three different MoE models (ROBERTa-MoE, GPT-MoE, and Swin-MoE-L) across various configurations. Subfigure (a) shows the baseline with 16 GPUs. Subfigure (b) doubles the number of GPUs to 32, demonstrating the impact on communication overhead as the cluster size scales. Subfigure (c) doubles the number of experts within the model on a 16 GPU cluster to show the effect of increasing model complexity. The results indicate that all-to-all communication constitutes a significant portion of the total training time, hindering scalability.

read the caption

Figure 3: Proportion of all-to-all communication time relative to total training duration across different configurations: scaling the number of training servers (Figure 3(b)) and scaling the parameter size of models (Figure 3(c)).

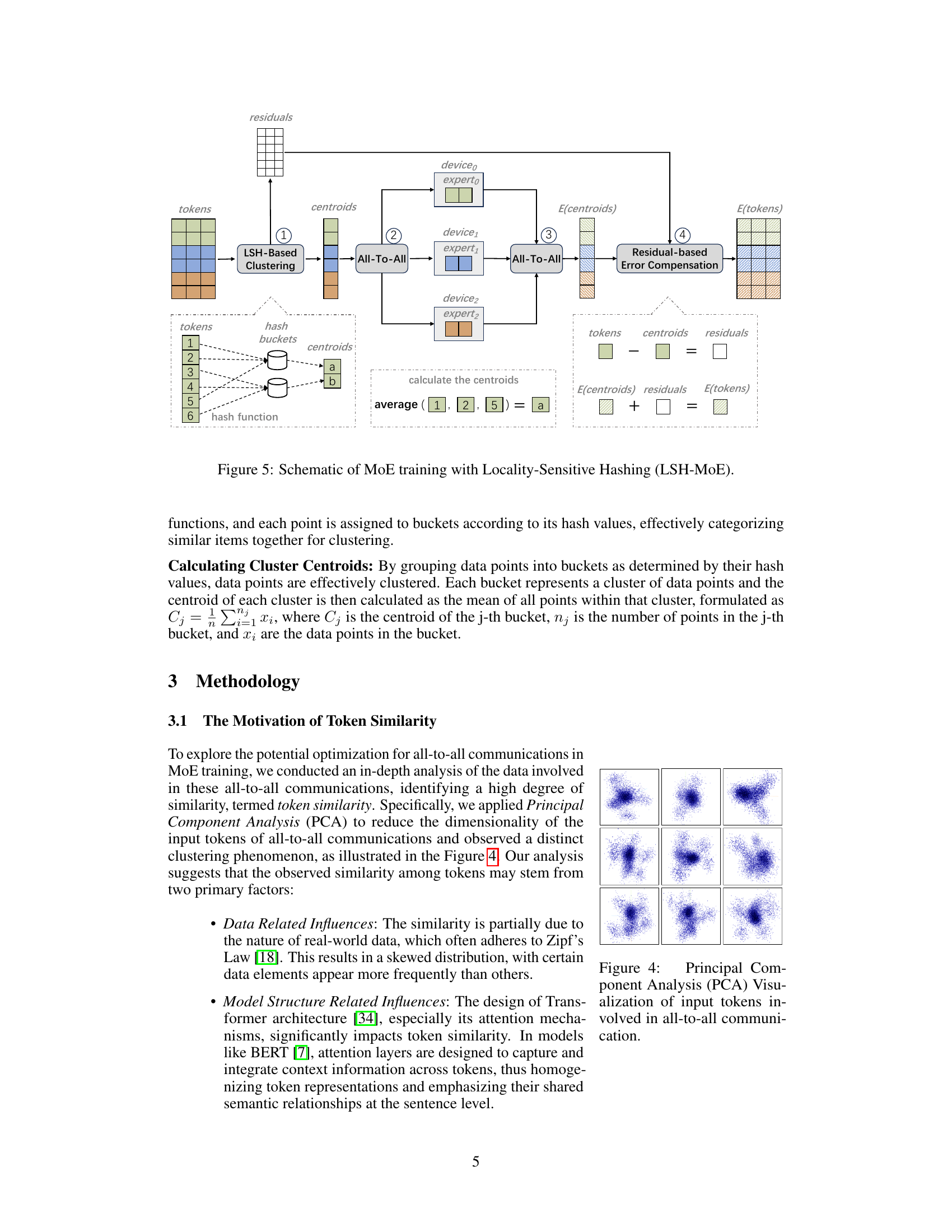

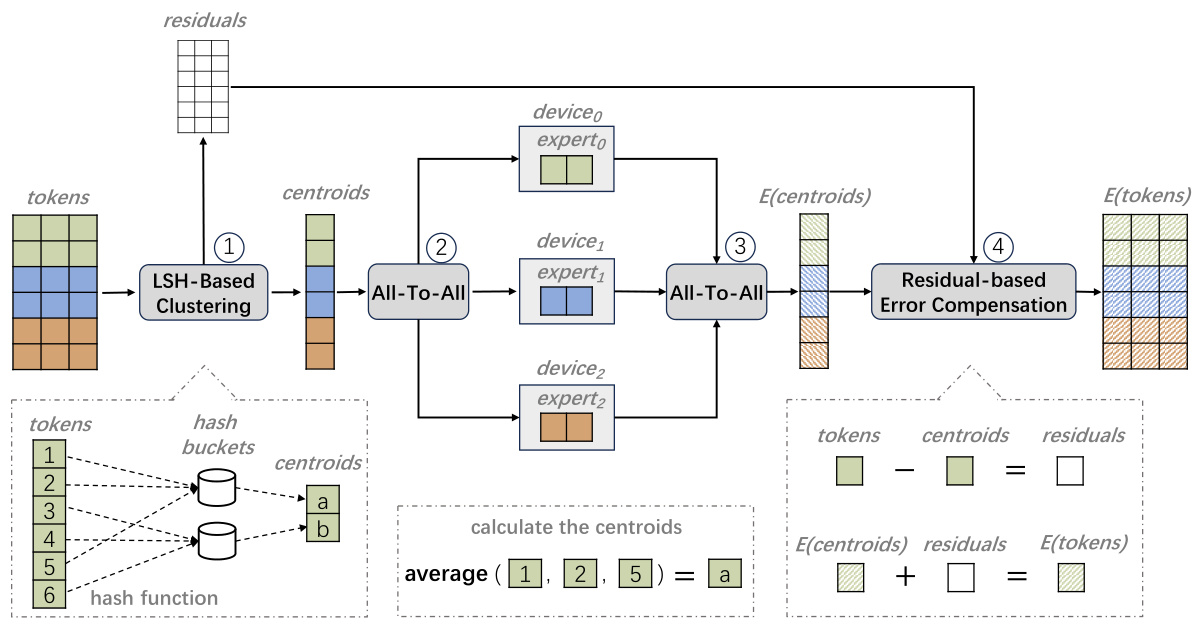

🔼 This figure illustrates the LSH-MoE framework. The process begins with Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH)-based clustering of tokens, grouping similar tokens into buckets and representing each bucket by its centroid. These centroids are then sent through the all-to-all communication phase to experts for processing, producing E(centroids). Another all-to-all communication phase returns the results. Finally, a residual-based error compensation step combines E(centroids) with the residuals (differences between original tokens and their centroids) to generate the final output E(tokens), approximating the results if all tokens were processed individually.

read the caption

Figure 5: Schematic of MoE training with Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH-MoE).

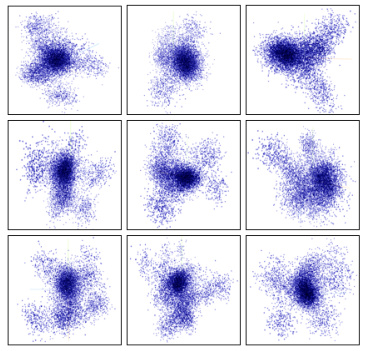

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of input tokens involved in all-to-all communication during MoE training. The visualization reveals distinct clusters of similar tokens, suggesting a high degree of token similarity. This similarity is attributed to both inherent characteristics of real-world data and the model architecture’s attention mechanism, which enhances semantic relationships between tokens. The presence of these clusters motivates the use of Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) for efficient data compression in the proposed LSH-MoE model.

read the caption

Figure 4: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Visualization of input tokens involved in all-to-all communication.

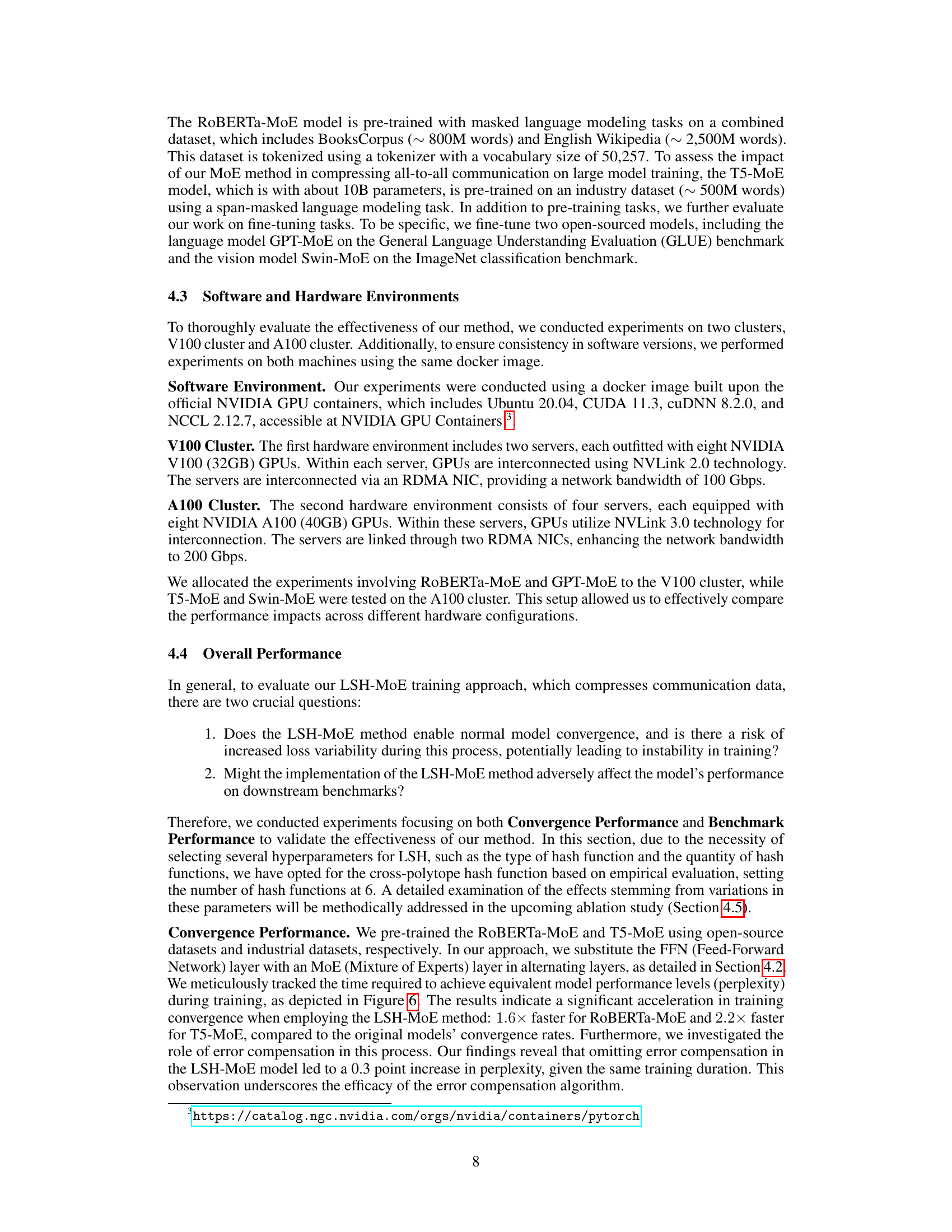

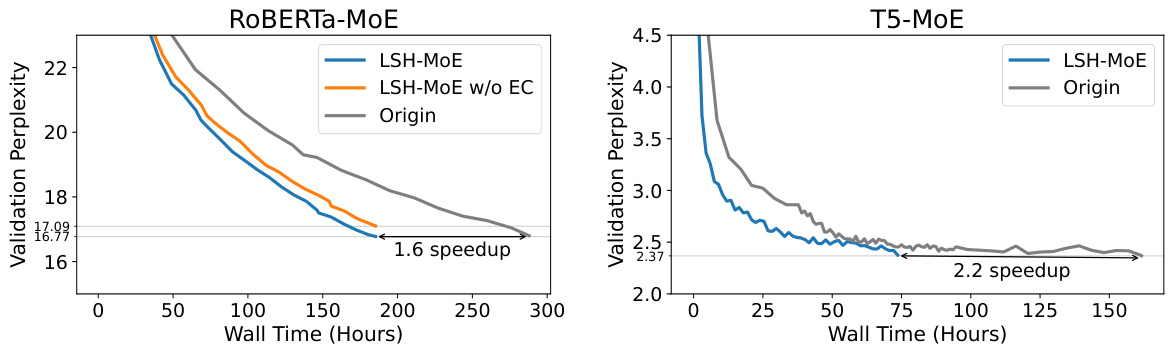

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of the training convergence speed between the original models and the proposed LSH-MoE model for two different language models (RoBERTa-MoE and T5-MoE). The x-axis represents the training time (wall time in hours), while the y-axis represents the validation perplexity. The figure demonstrates that LSH-MoE converges faster than the original model for both language models, achieving speedups of 1.6x and 2.2x, respectively. It also shows that using error compensation significantly improves performance, as the model trained without it performs less efficiently.

read the caption

Figure 6: Comparative analysis of convergence performance. This includes a comparison between the original models, LSH-MoE without Error Compensation, and LSH-MoE implementations. The perplexity curves are applied 1D Gaussian smoothing with σ = 0.5.

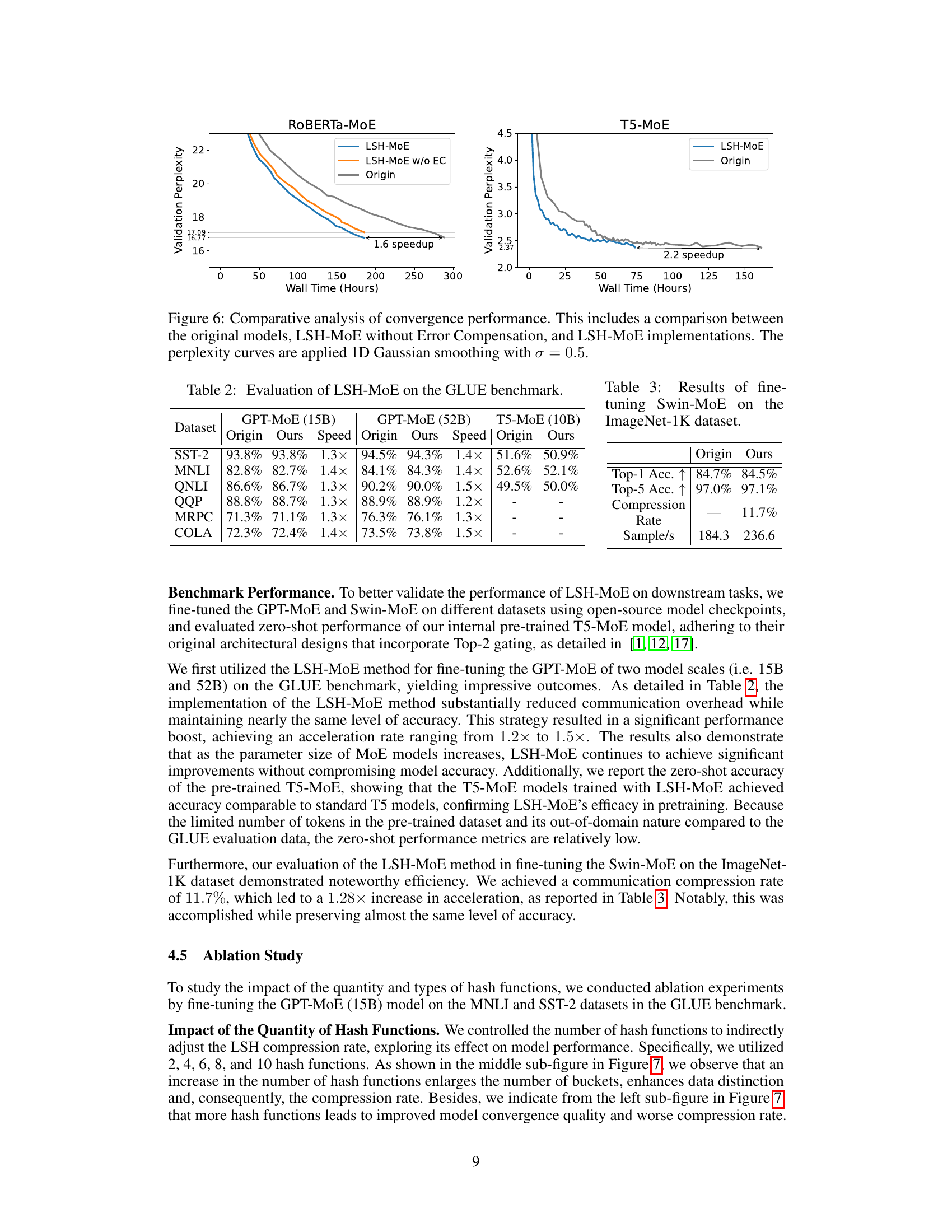

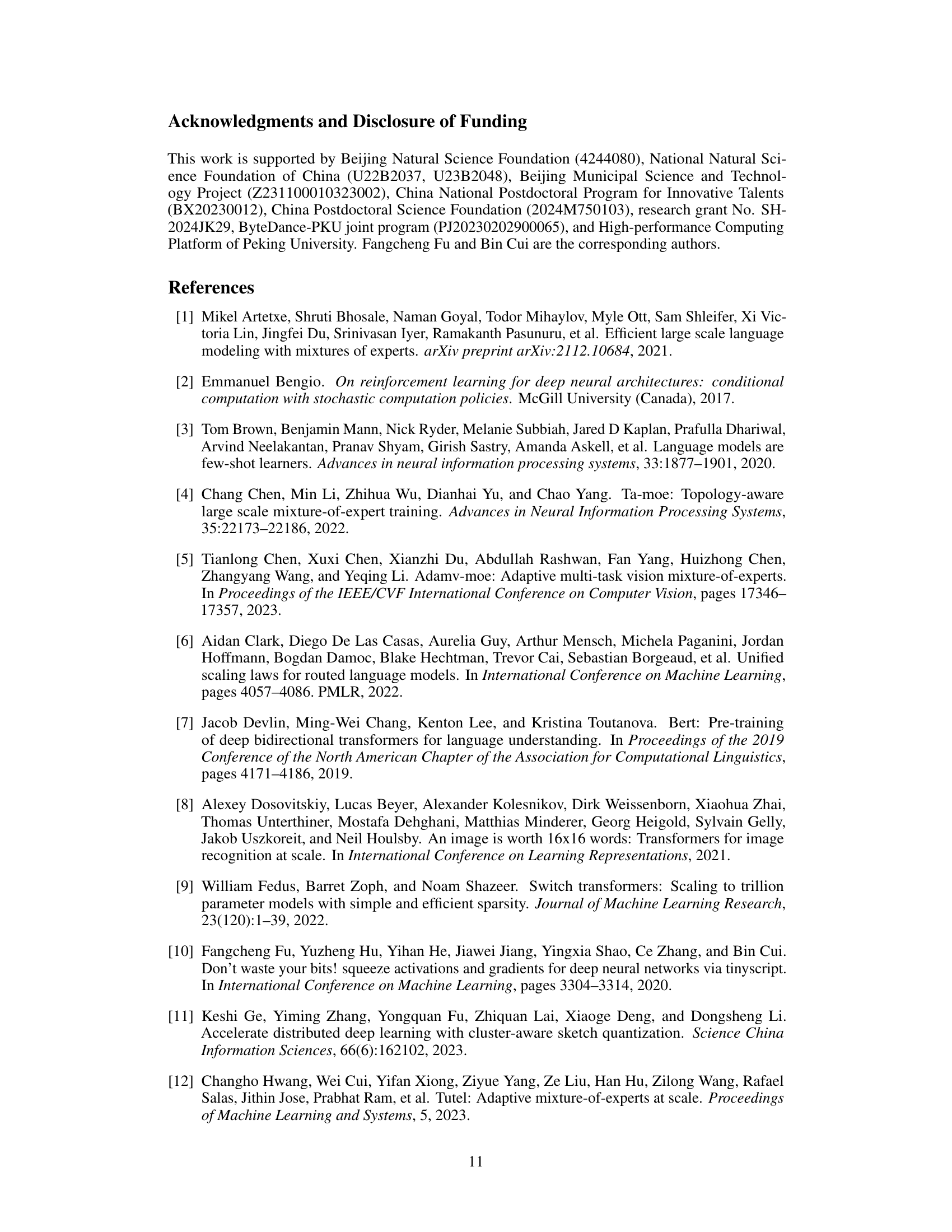

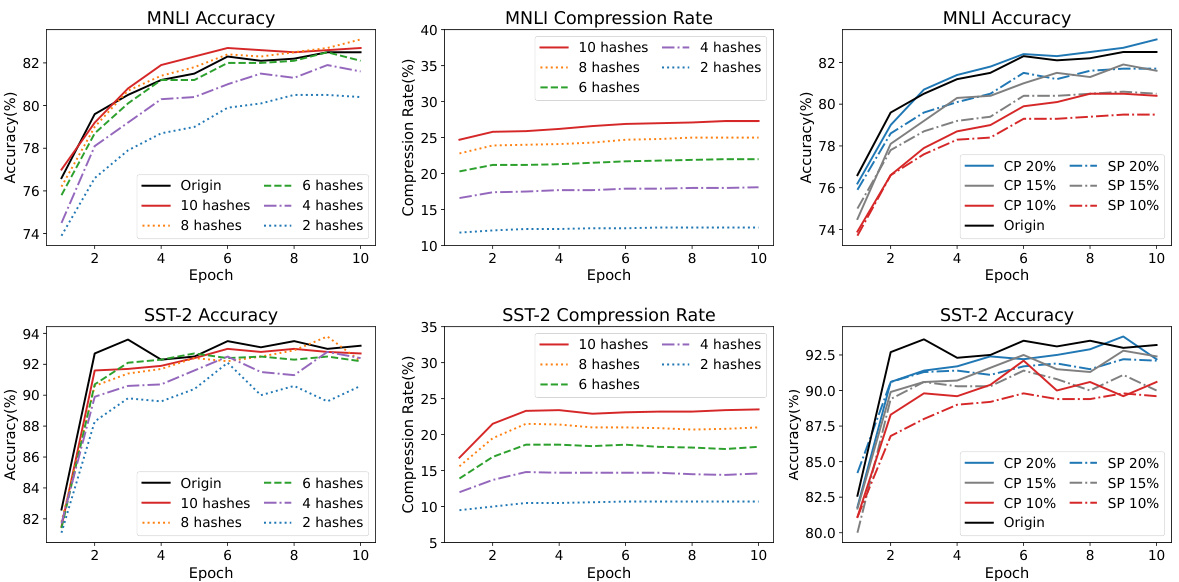

🔼 This figure shows the ablation study results on the impact of the quantity and types of hash functions used in the LSH-MoE method. The left column displays the accuracy achieved on MNLI and SST-2 datasets for different numbers of hash functions (2, 4, 6, 8, 10). The middle column shows the corresponding compression rates. The right column presents the results comparing two types of hash functions, cross-polytope (CP) and spherical (SP), at three different compression rates (10%, 15%, 20%). The results demonstrate the optimal number of hash functions for balancing accuracy and compression.

read the caption

Figure 7: An in-depth analysis of the compression rate and the model performance by adjusting the quantity and types of hash functions. The left and middle sub-figures are results for diverse quantities of hash functions. The right sub-figure is the result for diverse types of hash functions (CP for cross-polytope and SP for spherical) with different compression rates (20%, 15%, 10%).

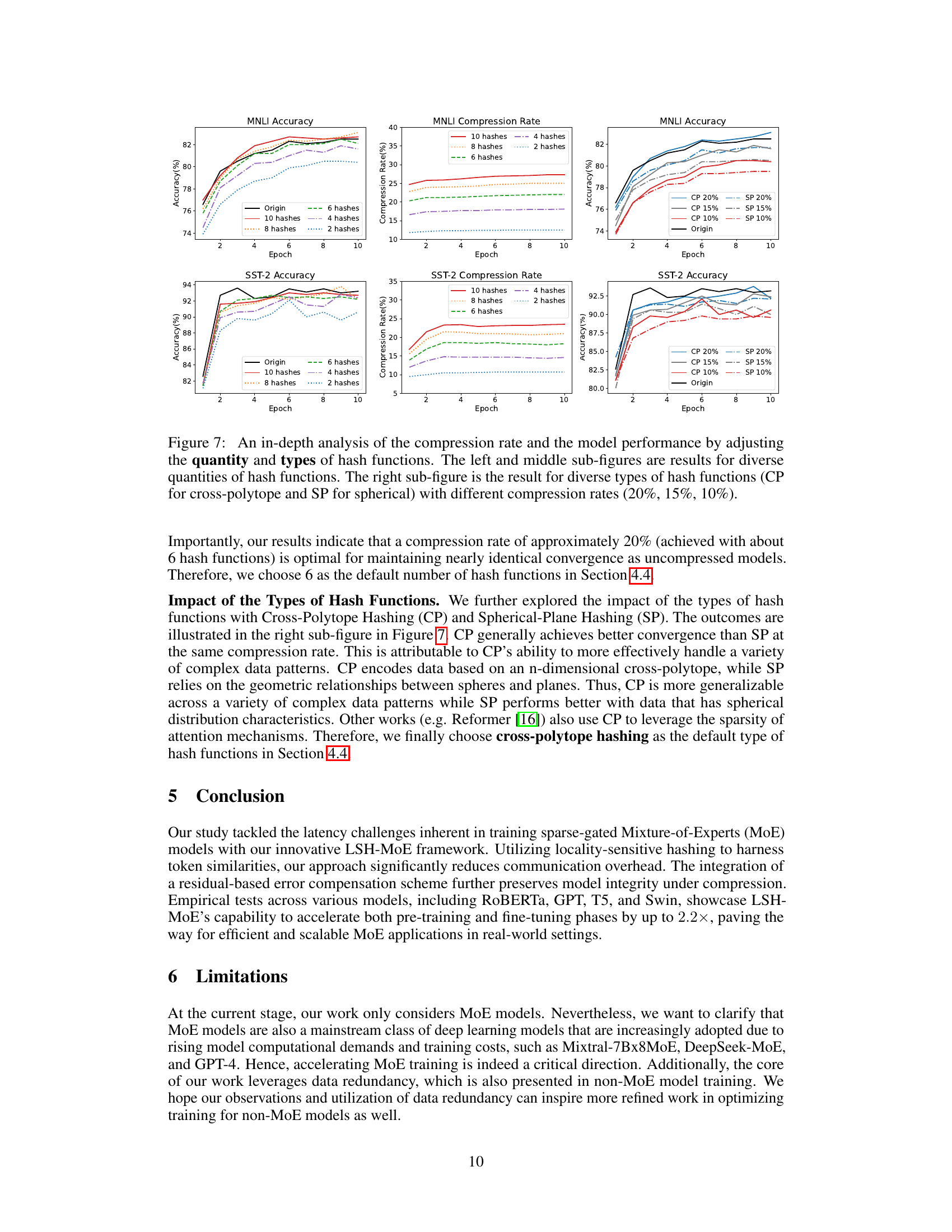

More on tables

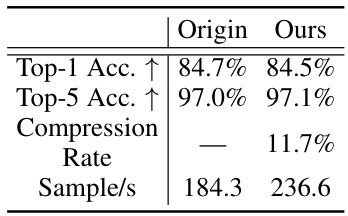

🔼 This table presents the results of fine-tuning the Swin-MoE model on the ImageNet-1K dataset. It compares the performance of the original Swin-MoE model against the proposed LSH-MoE method. The metrics include Top-1 accuracy, Top-5 accuracy, compression rate, and samples per second. The compression rate shows the efficiency of LSH-MoE in reducing communication overhead during training. The samples/second metric indicates a speedup achieved by LSH-MoE.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of fine-tuning Swin-MoE on the ImageNet-1K dataset.

🔼 This table presents the specifications of the four different MoE models used in the paper’s experiments. For each model, it lists the number of layers, the dimensionality of the model (dmodel), the dimensionality of the feed-forward network (dffn), the number of experts used, and the total number of parameters in the model. The model sizes vary significantly, ranging from hundreds of millions to tens of billions of parameters, showcasing the scale of models used in the experiments.

read the caption

Table 1: Models for evaluation, where '-' indicates that the values are different across layers.

Full paper#