↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reinforcement learning (RL) agents often struggle with exploration, especially in complex environments with sparse rewards. Traditional methods, primarily relying on entropy maximization, often overlook the inherent structure within state and action spaces, leading to inefficient exploration. This often results in imbalanced exploration towards low-value states.

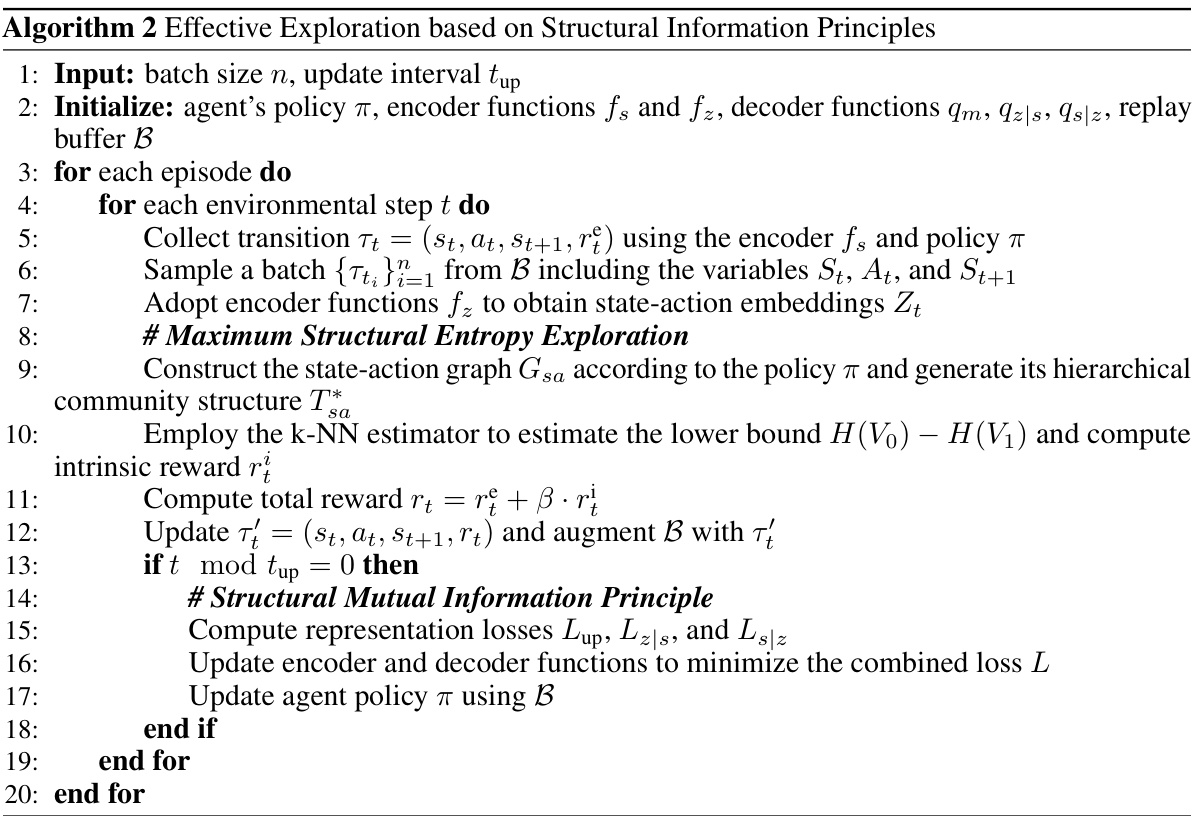

This paper introduces SI2E, a novel framework that effectively addresses these issues. SI2E embeds state-action pairs into a low-dimensional space, maximizing structural mutual information with future states while minimizing it with current states. It then leverages a hierarchical state-action structure (encoding tree) to design an intrinsic reward mechanism that prioritizes valuable state-action transitions, avoiding redundancy and maximizing coverage. Extensive experiments demonstrate that SI2E significantly outperforms existing methods in final performance and sample efficiency across various benchmark tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in reinforcement learning because it presents SI2E, a novel framework that significantly improves exploration efficiency and final performance. It addresses the limitations of existing entropy-based methods by incorporating structural information principles, leading to more effective exploration, especially in high-dimensional and sparse-reward environments. This opens avenues for future work in developing advanced exploration techniques.

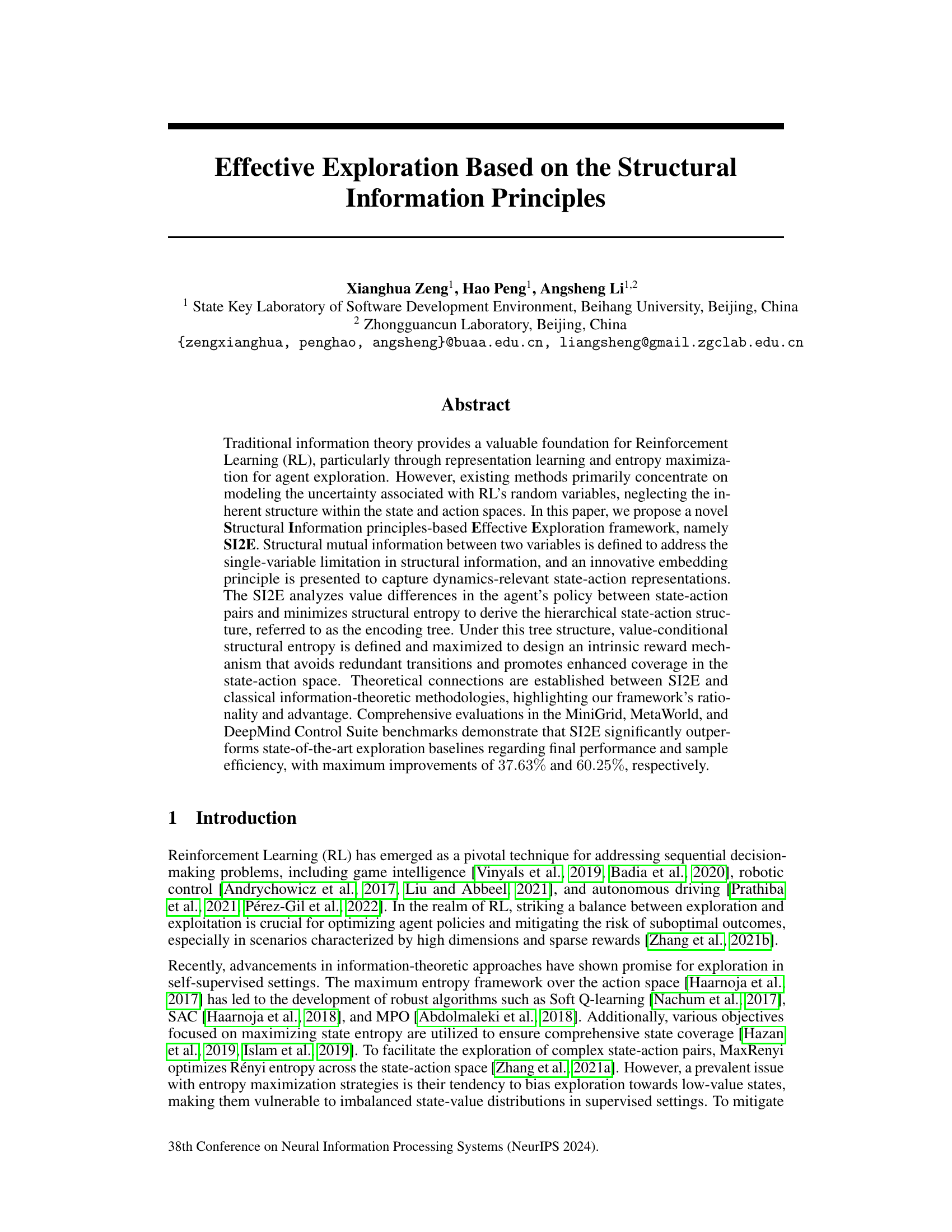

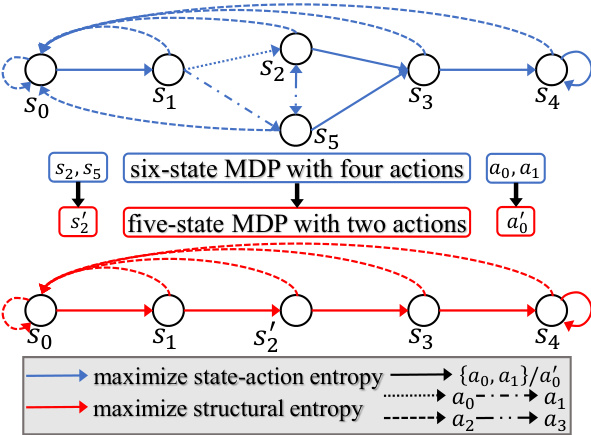

Visual Insights#

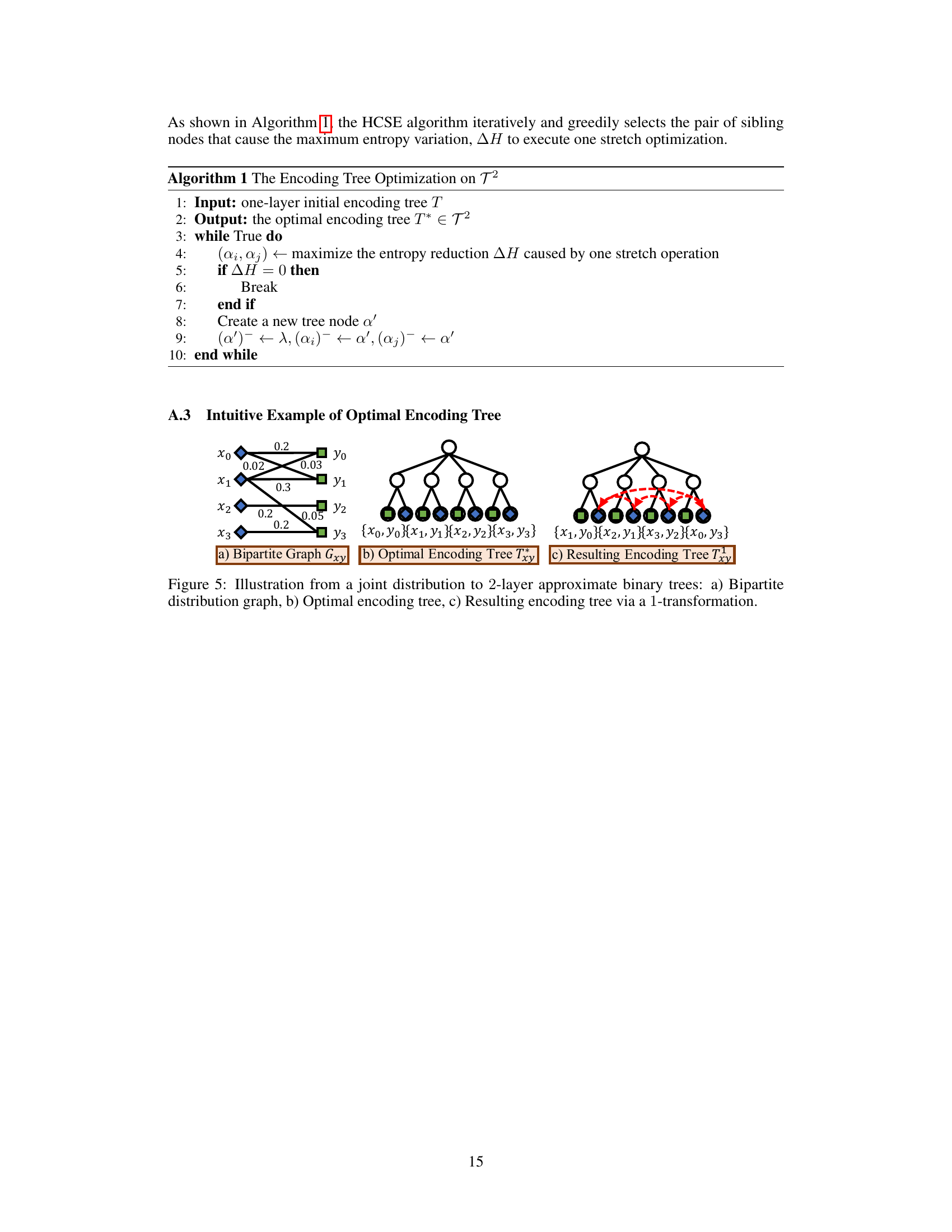

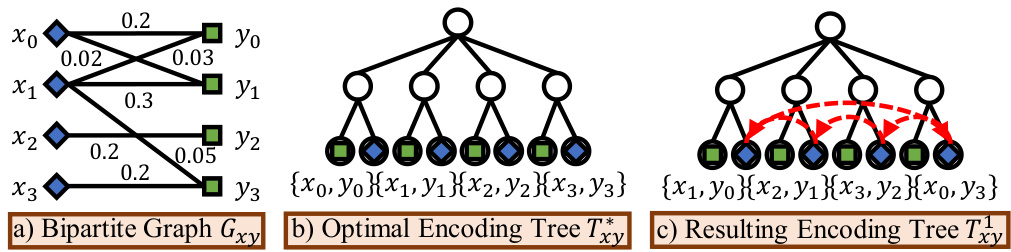

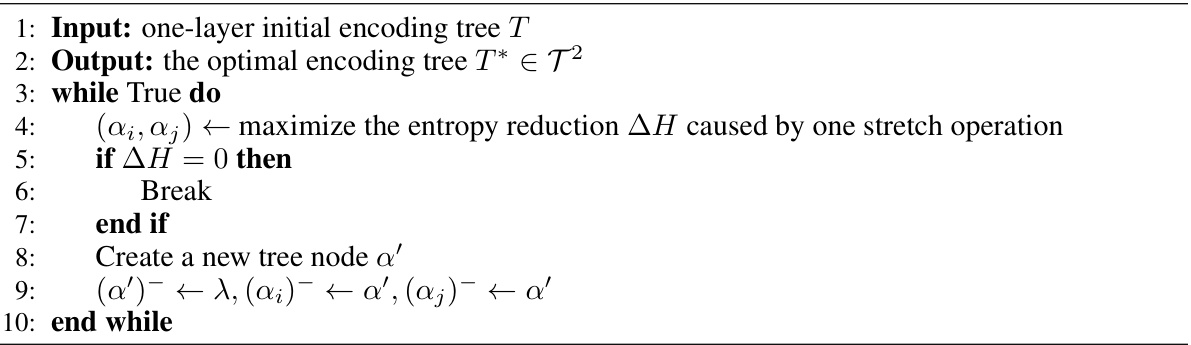

This figure illustrates how incorporating inherent state-action structure simplifies a Markov Decision Process (MDP). A six-state MDP with four actions is reduced to a five-state MDP with only two actions by grouping states and actions into communities. The comparison highlights the difference between policies that maximize state-action entropy (exploring all transitions) versus policies that maximize structural entropy (selectively focusing on crucial transitions and avoiding redundancy).

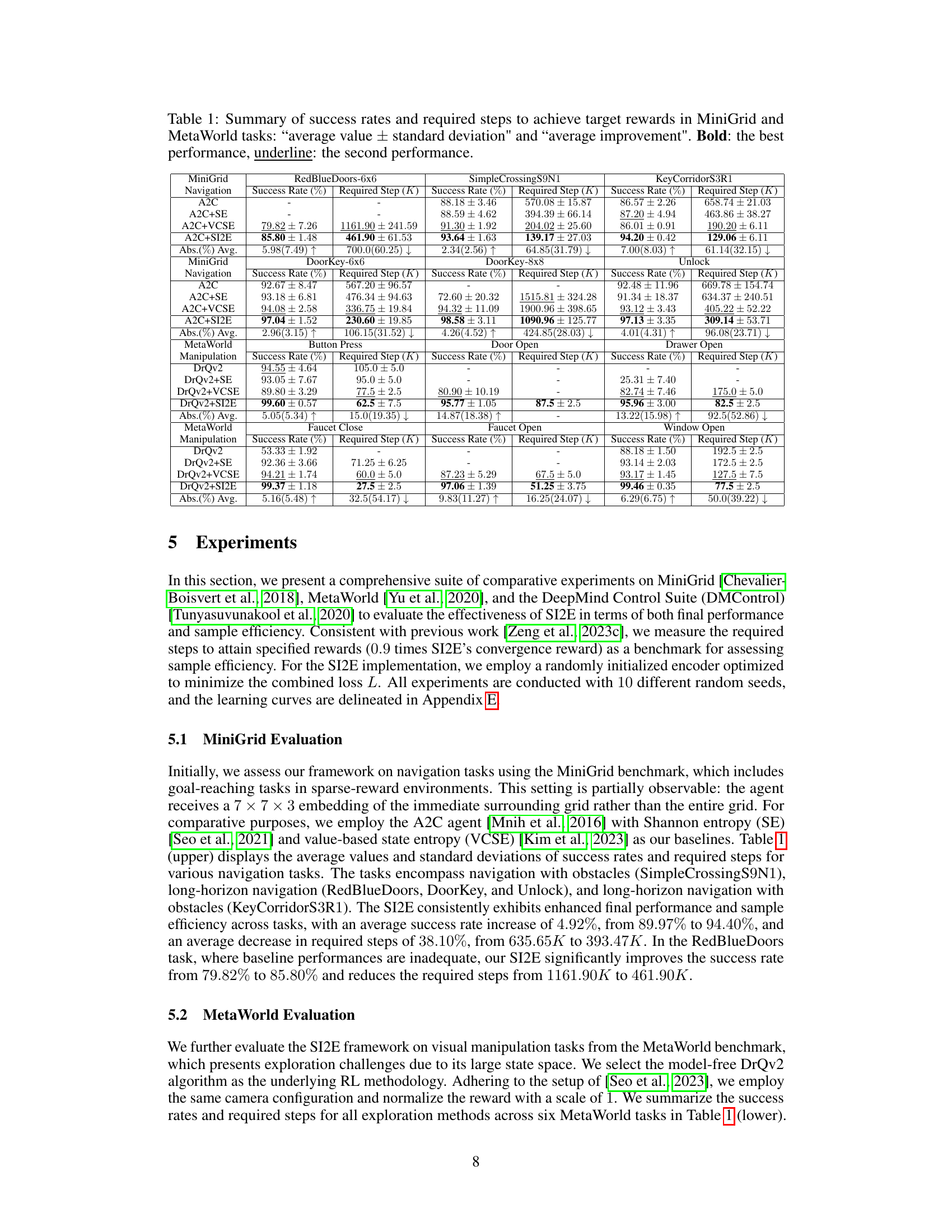

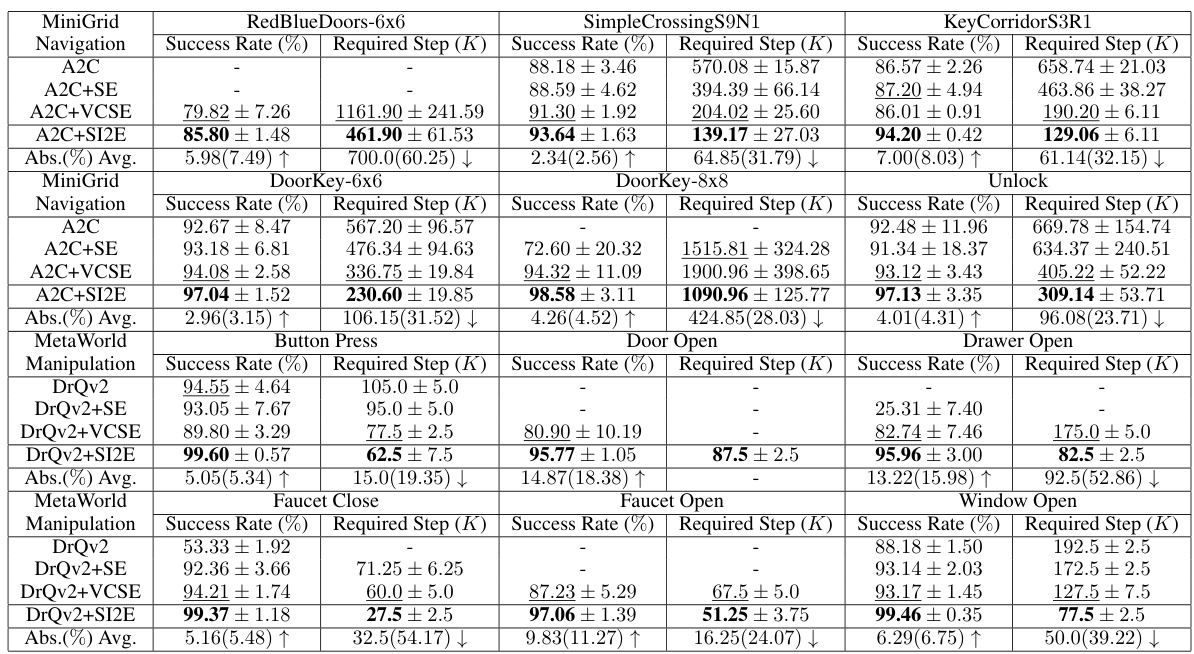

This table summarizes the performance of different reinforcement learning algorithms on MiniGrid and MetaWorld tasks. For each task and algorithm, it shows the average success rate (percentage of successful trials) and the average number of steps required to reach the target reward. The results are presented as average values ± standard deviations, providing a measure of variability. The table also shows the average percentage improvement of the proposed algorithm (SI2E) compared to the baseline algorithms.

In-depth insights#

Structural Info Principle#

The concept of ‘Structural Information Principles’ offers a novel approach to understanding and leveraging information within complex systems. Unlike traditional information theory that primarily focuses on individual variables, this principle emphasizes the inherent structure and relationships between variables. By analyzing this structure, one can uncover hidden patterns and dependencies, gaining a deeper understanding than simply examining individual variables in isolation. A key aspect is the representation of this structure, often through graphs or trees, which then allows for the quantification of uncertainty using metrics such as structural entropy. The ability to model and quantify structural information opens doors for advanced applications across various fields; from network analysis to reinforcement learning, where it can be utilized to guide exploration and decision-making more effectively than traditional information-theoretic methods, by incorporating the inherent relationships and hierarchical structure. Encoding trees, for example, provide a hierarchical representation to effectively capture the structural dynamics. The value of this approach is found in its ability to deal with complex, high-dimensional data by first simplifying its structure before performing any analysis. The use of structural information allows for a shift from treating data simply as a set of variables to considering its organizational essence, leading to powerful insights and more effective utilization of the information contained within.

SI2E Framework#

The SI2E framework presents a novel approach to effective exploration in reinforcement learning, particularly in high-dimensional and sparse-reward environments. It uniquely combines structural information principles with traditional information-theoretic methods, addressing limitations of existing techniques that neglect the inherent structure within state and action spaces. A key innovation is the introduction of structural mutual information, which overcomes the single-variable constraint of existing structural information measures. This allows SI2E to capture dynamics-relevant state-action representations more effectively and, via an encoding tree, efficiently identify and minimize redundant transitions. The intrinsic reward mechanism, maximizing value-conditional structural entropy, further encourages exploration of under-visited, high-value areas of the state-action space, mitigating the risk of biased exploration towards low-value states. The framework demonstrates significant performance improvements and sample efficiency gains compared to state-of-the-art exploration methods across multiple benchmark tasks, showcasing its robustness and potential for broad applications within reinforcement learning.

Intrinsic Reward Design#

Intrinsic reward design is crucial for effective exploration in reinforcement learning, particularly in sparse-reward environments. The core idea is to incentivize the agent to explore novel or informative states, rather than relying solely on external rewards which are infrequent. A well-designed intrinsic reward should balance exploration and exploitation, encouraging the agent to visit under-explored regions of the state-action space while still prioritizing actions that lead to higher expected returns. Common approaches leverage concepts from information theory (e.g., maximizing entropy, minimizing surprise), often using value-conditional state entropy to guide exploration. However, a significant challenge is to prevent biased exploration towards low-value states which can hinder overall performance. The effectiveness of an intrinsic reward depends on carefully calibrating the reward signal, addressing the issue of imbalanced state-value distributions and balancing the trade-off between novelty and maximizing cumulative reward. Novel approaches that incorporate structural information and hierarchical representations may offer more robust and effective exploration strategies.

Empirical Evaluations#

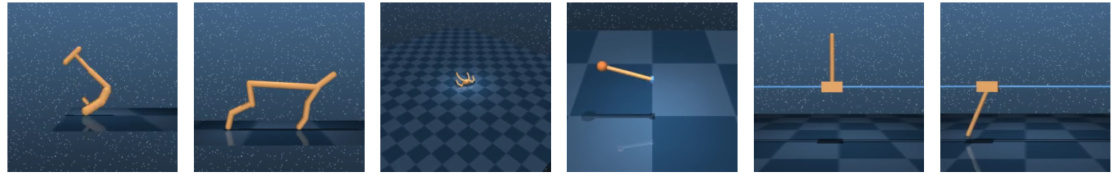

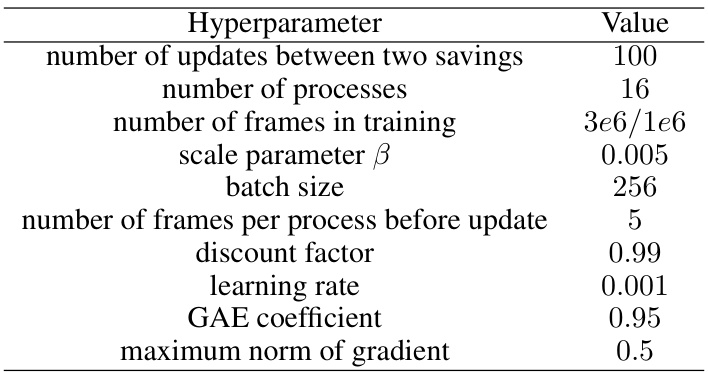

A robust empirical evaluation section is crucial for validating the claims of a research paper. It should go beyond simply presenting results; it needs a deep dive into methodology, comparing against relevant baselines, and thoroughly analyzing the results across various metrics. For example, a good empirical evaluation would clearly specify the experimental setup, including the environments, hyperparameters, and evaluation metrics used. It should also discuss any potential limitations or biases in the experimental design. Furthermore, a strong evaluation would not only present the average performance but also error bars and statistical significance tests to illustrate the reliability and robustness of the results. Ideally, results would be visualized clearly, aiding in the reader’s understanding of the findings. A discussion of unexpected or insightful results found during the evaluation is highly valuable, as it could inspire future research directions. Finally, the section should provide a concise yet insightful summary of the key findings, highlighting the overall contributions and limitations of the work.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section is a missed opportunity. A thoughtful discussion could have expanded on several promising avenues. Extending the encoding tree’s height is crucial, as it directly impacts the framework’s ability to model complex, hierarchical relationships within state-action spaces. This would improve performance in highly intricate environments. Exploring diverse RL algorithms beyond A2C and DrQv2 would demonstrate SI2E’s broader applicability and robustness. Analyzing the sensitivity to hyperparameters (such as β and n) with more rigorous experimentation is also necessary. The paper mentions limitations, but a future work section would allow for a focused exploration of how to address them. Lastly, applying SI2E to real-world, complex problems outside of the benchmark environments would solidify its practical value and uncover potential unforeseen challenges or opportunities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

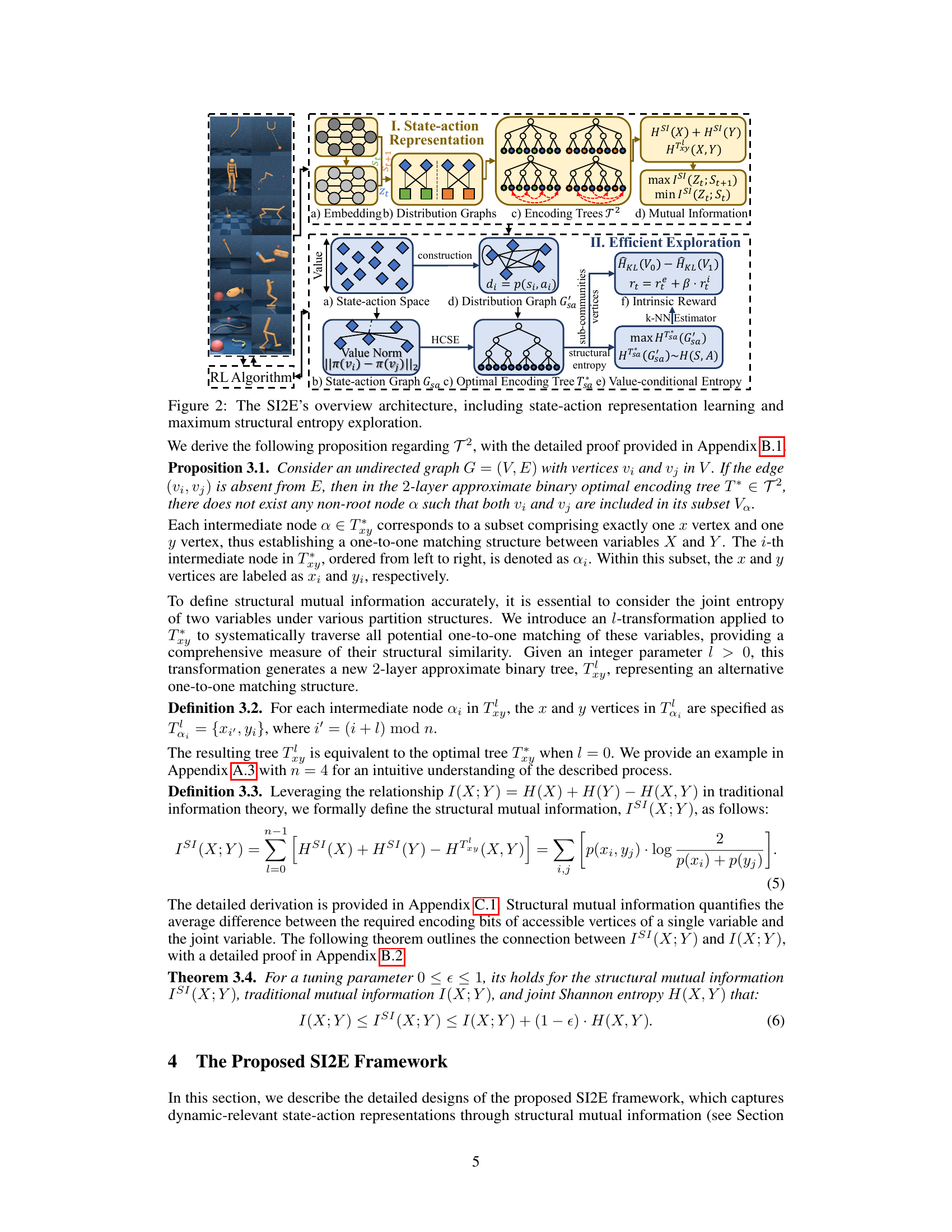

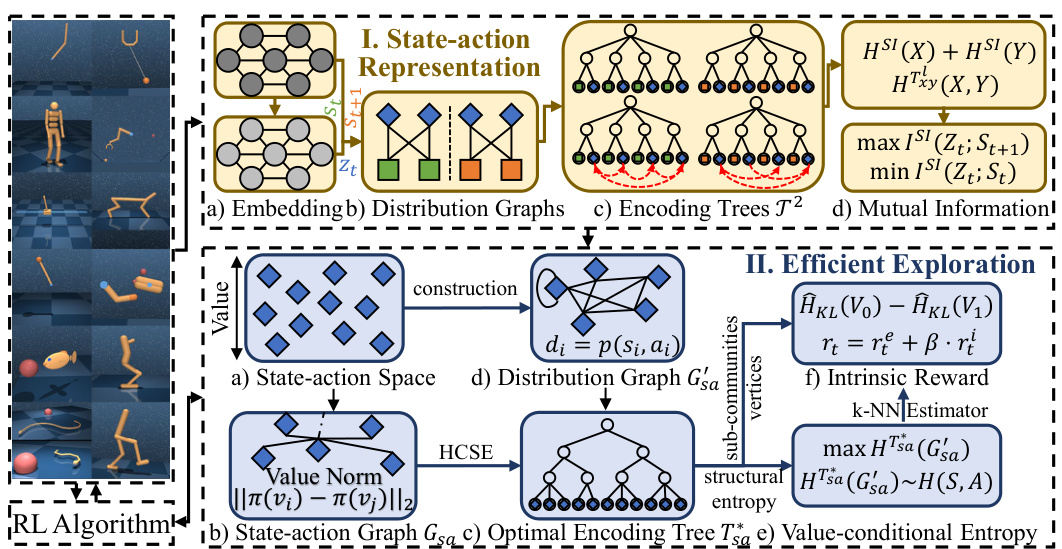

This figure provides a visual representation of the SI2E framework, showing the two main stages: State-action Representation Learning and Maximum Structural Entropy Exploration. The first stage involves embedding state-action pairs, constructing distribution graphs, generating encoding trees, and maximizing mutual information. The second stage involves constructing a state-action graph based on policy values, minimizing structural entropy, calculating an intrinsic reward using a k-NN estimator, and using this reward in an RL algorithm to guide exploration. The figure details the steps involved and the data flow between each component, offering a comprehensive visual overview of the SI2E’s architecture.

This figure presents a comprehensive overview of the SI2E framework. It illustrates the two main components: state-action representation learning and maximum structural entropy exploration. The state-action representation learning component focuses on embedding state-action pairs into a low-dimensional space, maximizing mutual information with subsequent states and minimizing it with current states to capture dynamics-relevant information. The maximum structural entropy exploration component involves constructing a graph from state-action pairs based on value differences, minimizing structural entropy to find a hierarchical structure, and defining a value-conditional structural entropy as an intrinsic reward to guide exploration, avoiding redundant transitions and promoting coverage of the state-action space.

This figure presents a high-level overview of the SI2E framework, which is composed of two main stages: state-action representation learning and maximum structural entropy exploration. The representation learning stage focuses on embedding state-action pairs into a low-dimensional space using a novel principle that maximizes structural mutual information with subsequent states and minimizes it with current states. This stage involves constructing distribution graphs, encoding trees, and calculating mutual information. The maximum structural entropy exploration stage then leverages the hierarchical community structure identified in the representation learning stage to design an intrinsic reward mechanism that guides exploration and avoids redundant transitions. The figure highlights the key components and processes within each stage, illustrating how SI2E integrates structural information principles for effective exploration in reinforcement learning.

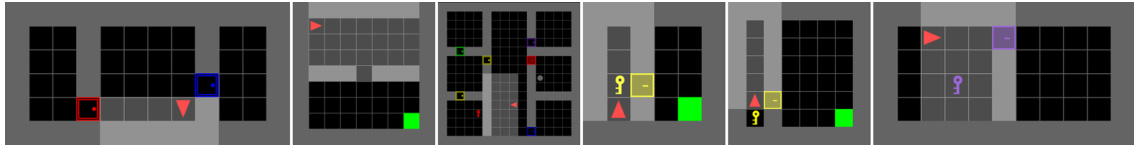

This figure shows six example navigation tasks from the MiniGrid environment used in the paper’s experiments. Each sub-figure (a-f) displays a different task, illustrating the variety of challenges involved in the MiniGrid navigation tasks. The tasks range in complexity from simple to more complex scenarios involving multiple obstacles and longer paths.

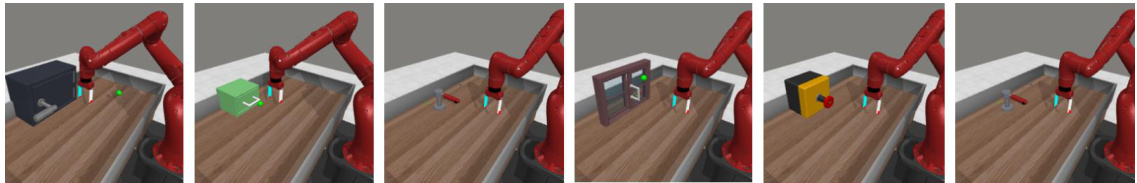

This figure shows six different manipulation tasks from the MetaWorld benchmark dataset used in the paper’s experiments. Each subfigure shows a robotic arm interacting with a different object or environment. These tasks represent a variety of manipulation challenges, including opening and closing containers and activating objects.

This figure presents a detailed overview of the proposed SI2E framework, which is composed of two main components: state-action representation learning and maximum structural entropy exploration. The state-action representation learning component focuses on embedding state-action pairs into a low-dimensional space while maximizing relevant information and minimizing irrelevant information using structural mutual information. The maximum structural entropy exploration component uses a hierarchical state-action structure to design an intrinsic reward mechanism that avoids redundant transitions and promotes enhanced coverage of the state-action space. The figure visually represents the flow of information and the key processes involved in each component, providing a comprehensive understanding of SI2E’s architecture.

This figure presents a visual overview of the SI2E framework, highlighting its two main components: state-action representation learning and maximum structural entropy exploration. The state-action representation learning module uses a novel embedding principle based on structural mutual information to capture dynamics-relevant information. This module involves creating distribution graphs, encoding trees, and calculating structural mutual information to minimize information about the current state and maximize information about the next state. The efficient exploration module then leverages this learned representation by maximizing value-conditional structural entropy via an intrinsic reward mechanism. The reward function promotes state-action space coverage while avoiding redundant exploration. The figure visually depicts these steps and their interactions within the SI2E framework.

This figure presents a comprehensive overview of the SI2E framework. It is broken down into two main stages: state-action representation learning and efficient exploration. The representation learning stage focuses on embedding state-action pairs into a low-dimensional space using a novel principle that maximizes the structural mutual information with future states while minimizing it with current states. This involves creating distribution graphs and encoding trees to capture the relevant dynamic information. The efficient exploration stage leverages the hierarchical structure identified in the previous stage to design an intrinsic reward mechanism that maximizes value-conditional structural entropy. This avoids redundant transitions and promotes enhanced coverage of the state-action space. The figure visually depicts these stages and their interconnections, highlighting the key components and processes involved.

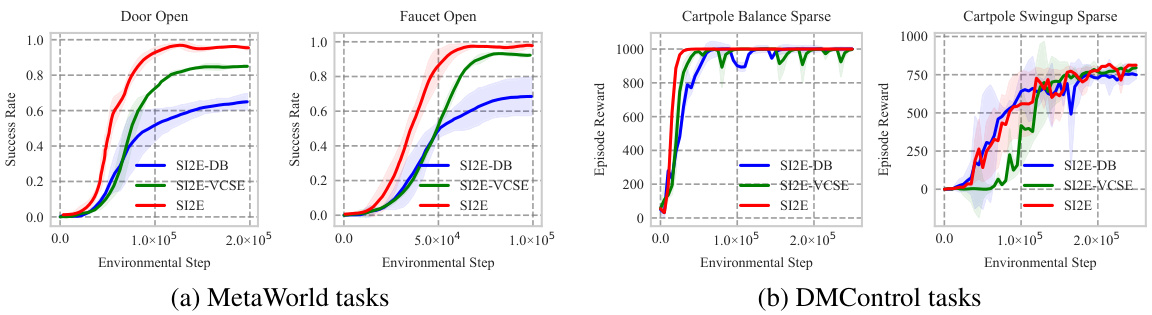

This figure compares the sample efficiency of SI2E against the best performing baseline across six DMControl tasks. The y-axis represents the percentage of the total 250,000 environmental steps required to reach the reward target. The x-axis shows the six different DMControl tasks. The bars show that SI2E requires significantly fewer steps (a lower percentage) than the baseline to achieve the target reward in most tasks, demonstrating its improved sample efficiency.

This figure presents a comprehensive overview of the SI2E framework, which is composed of two main modules: state-action representation learning and maximum structural entropy exploration. The state-action representation learning module focuses on embedding state-action pairs into a low-dimensional space and capturing dynamics-relevant information, while the maximum structural entropy exploration module utilizes the learned representation to guide exploration by maximizing value-conditional structural entropy. The figure details the steps involved in both modules, including state-action representation, embedding distribution graph generation, encoding tree construction, mutual information maximization and minimization, intrinsic reward calculation, and the overall RL algorithm.

This figure provides a visual overview of the SI2E framework’s architecture. It shows two main components: state-action representation learning and maximum structural entropy exploration. The state-action representation learning component uses an innovative embedding principle to capture dynamics-relevant information, maximizing structural mutual information with subsequent states while minimizing it with current states. The maximum structural entropy exploration component uses a hierarchical state-action structure to design an intrinsic reward mechanism, promoting enhanced coverage in the state-action space and avoiding redundant transitions. The figure details the different steps involved in each component, including embedding, graph construction, tree creation, mutual information calculation, and intrinsic reward generation.

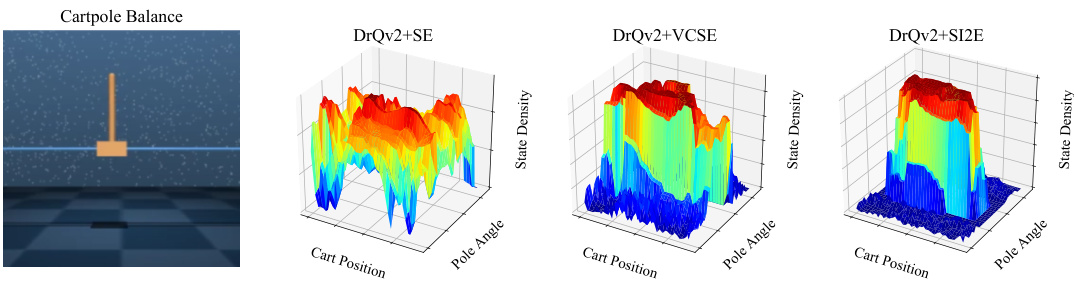

This figure visualizes the exploration behavior of three different exploration methods (DrQv2+SE, DrQv2+VCSE, DrQv2+SI2E) in the CartPole Balance task. Each heatmap shows the density of states visited by each algorithm across two dimensions: cart position and pole angle. The goal is to show how effectively each method explores the state space. The visualization helps to understand which areas of the state space are more frequently visited by each method and therefore how effectively exploration is conducted.

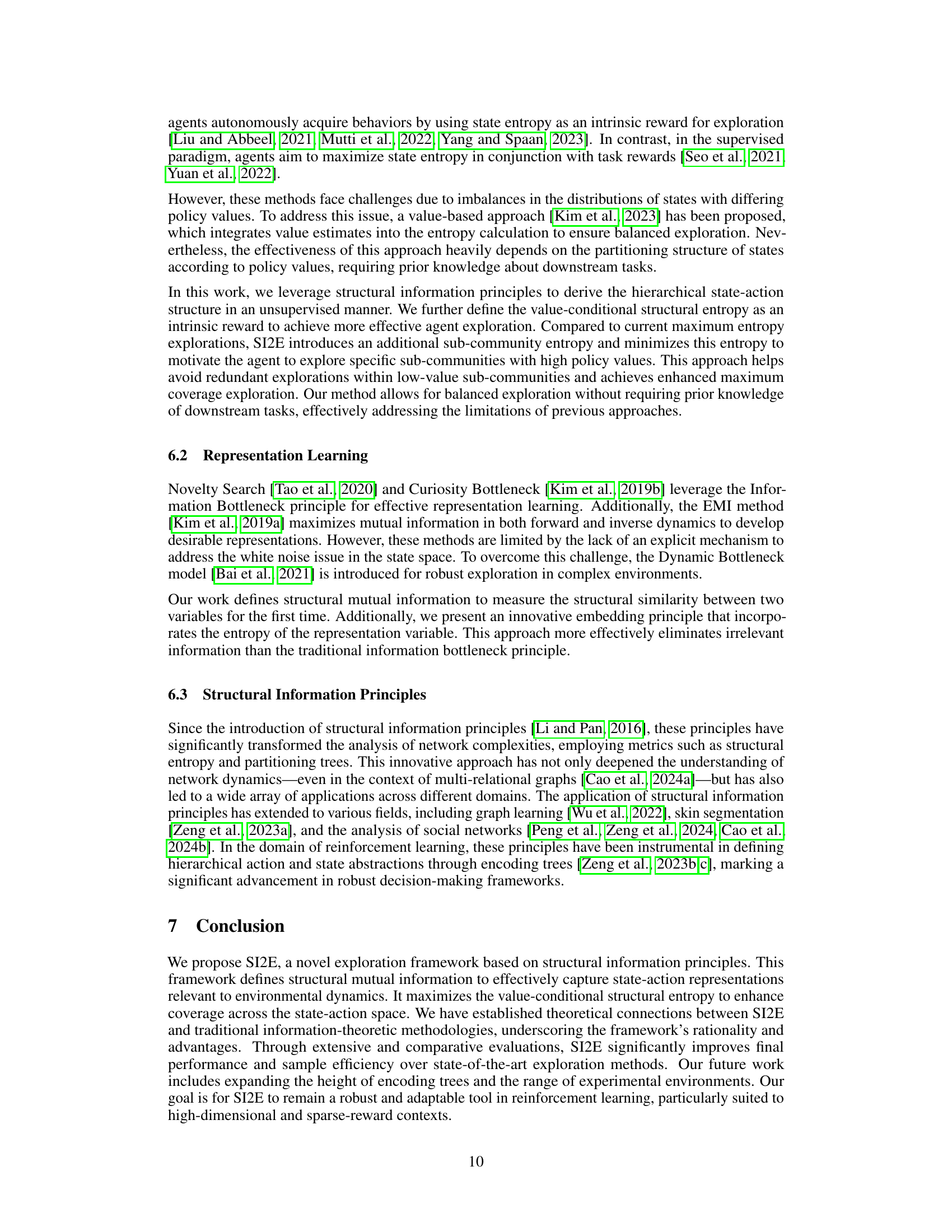

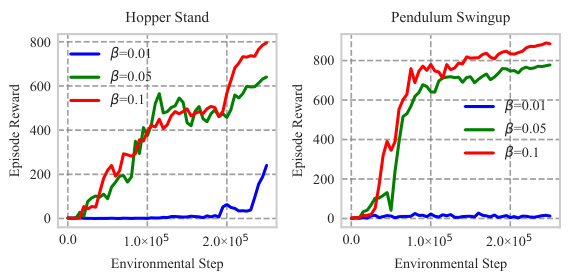

This figure shows the ablation study on the impact of parameters β and n on the SI2E framework’s performance. The left subplot shows that increasing β improves performance for both Hopper Stand and Pendulum Swingup tasks. The right subplot shows that varying n has little impact on performance. The solid line represents the average of 10 runs.

This figure displays the learning curves obtained from the SI2E algorithm when the scale parameter (β) and batch size (n) are varied for the Hopper Stand and Pendulum Swingup tasks. The graphs illustrate the impact of adjusting β and n on the algorithm’s performance, as measured by the episode reward. Each line represents the performance of the SI2E algorithm with a different value for β and n, and the shaded area denotes the standard deviation across 10 runs.

More on tables

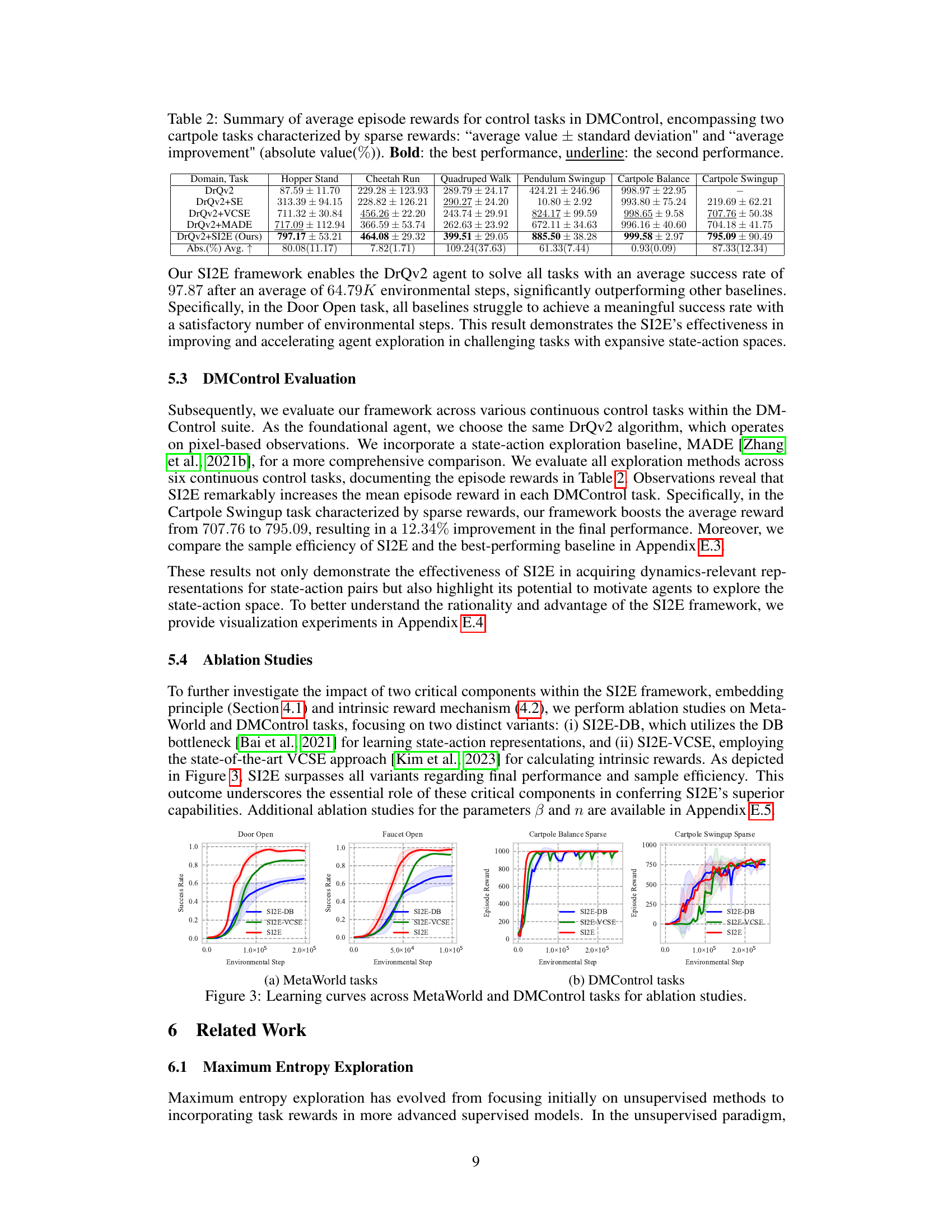

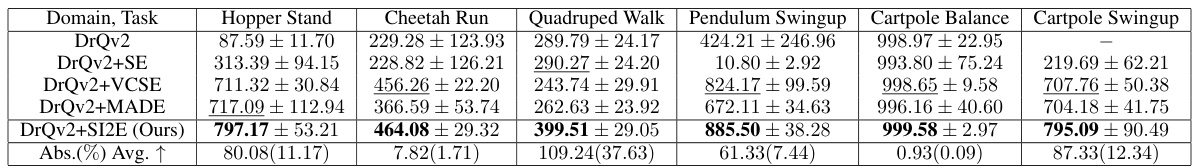

This table presents the average episode rewards achieved by different reinforcement learning algorithms (DrQv2 and its variants with different exploration methods) on six continuous control tasks from the DeepMind Control Suite. Two cartpole tasks are highlighted as having sparse rewards. The table shows average performance and standard deviation across multiple runs. The improvement of SI2E compared to the baseline DrQv2 is also indicated.

This table presents a summary of the performance of different reinforcement learning algorithms across various tasks in the MiniGrid and MetaWorld environments. It shows the success rates (percentage of times the algorithm successfully completed the task) and the number of steps required to achieve the target reward for each algorithm. The results are presented as average values with standard deviations, providing a measure of the algorithms’ performance variability. The table also calculates the average percentage improvement of each algorithm compared to a baseline.

This table presents a summary of the experimental results obtained for the MiniGrid and MetaWorld tasks. For each task, it shows the success rate (percentage of successful trials) and the average number of steps required to achieve the target reward, along with standard deviations. It highlights the best and second-best performing methods for each task, providing a quantitative comparison of the proposed SI2E method against baseline approaches. The values are presented as average ± standard deviation, and the average improvement of SI2E over the baselines is also indicated.

This table presents a summary of the experimental results obtained using the SI2E framework on MiniGrid and MetaWorld environments. For each task, it shows the average success rate and number of steps required to achieve the target reward, calculated across multiple trials. The table also includes the average improvement achieved by SI2E compared to other baselines. The best and second-best performances are highlighted in bold and underlined respectively. This provides a comprehensive comparison of the performance of SI2E against other state-of-the-art methods in terms of both final performance and sample efficiency.

This table summarizes the performance of different reinforcement learning algorithms on MiniGrid and MetaWorld tasks. For each task and algorithm, it shows the success rate (percentage of successful trials) and the average number of steps required to reach the target reward. The values are given as average ± standard deviation. The table helps compare the effectiveness of different exploration strategies in reinforcement learning.

This table presents a summary of the experimental results obtained on MiniGrid and MetaWorld tasks using different exploration methods. For each task and method, it shows the success rate (percentage) and the number of steps required to achieve the target reward. The results are expressed as average values ± standard deviations, allowing for comparison across different exploration methods. The table highlights the performance gains achieved by the SI2E method compared to several baselines.

This table presents a summary of the performance of different reinforcement learning algorithms on MiniGrid and MetaWorld tasks. For each task and algorithm, the table shows the average success rate and the average number of steps required to achieve the target reward. The results are presented as average value ± standard deviation. The best performance is highlighted in bold.

This table summarizes the performance of different reinforcement learning algorithms across various MiniGrid and MetaWorld tasks. It shows the success rate (percentage of successful trials) and the number of required steps to reach the target reward for each algorithm. The results are presented as average values plus or minus standard deviations, indicating variability across multiple trials. The table allows for a comparison of the performance of algorithms incorporating various exploration strategies (such as SI2E, SE, and VCSE) and also illustrates the sample efficiency of each approach.

Full paper#