↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional trajectory optimization methods struggle with complex dynamics and constraints. Model-free diffusion methods, while showing promise, lack generalizability due to their data-dependency. This limits their use in scenarios with new robots or imperfect data.

MBD addresses these limitations by incorporating model information directly into the diffusion process. This allows it to generate feasible trajectories without data, while also seamlessly integrating diverse data to improve optimization. The method demonstrates superior performance on challenging contact-rich tasks, showing its effectiveness and versatility in real-world applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents Model-Based Diffusion (MBD), a novel approach to trajectory optimization that outperforms existing methods. MBD leverages readily available model information, improving generalization and reducing reliance on large datasets. Its ability to integrate with imperfect data opens new avenues for research in challenging robotics tasks and beyond.

Visual Insights#

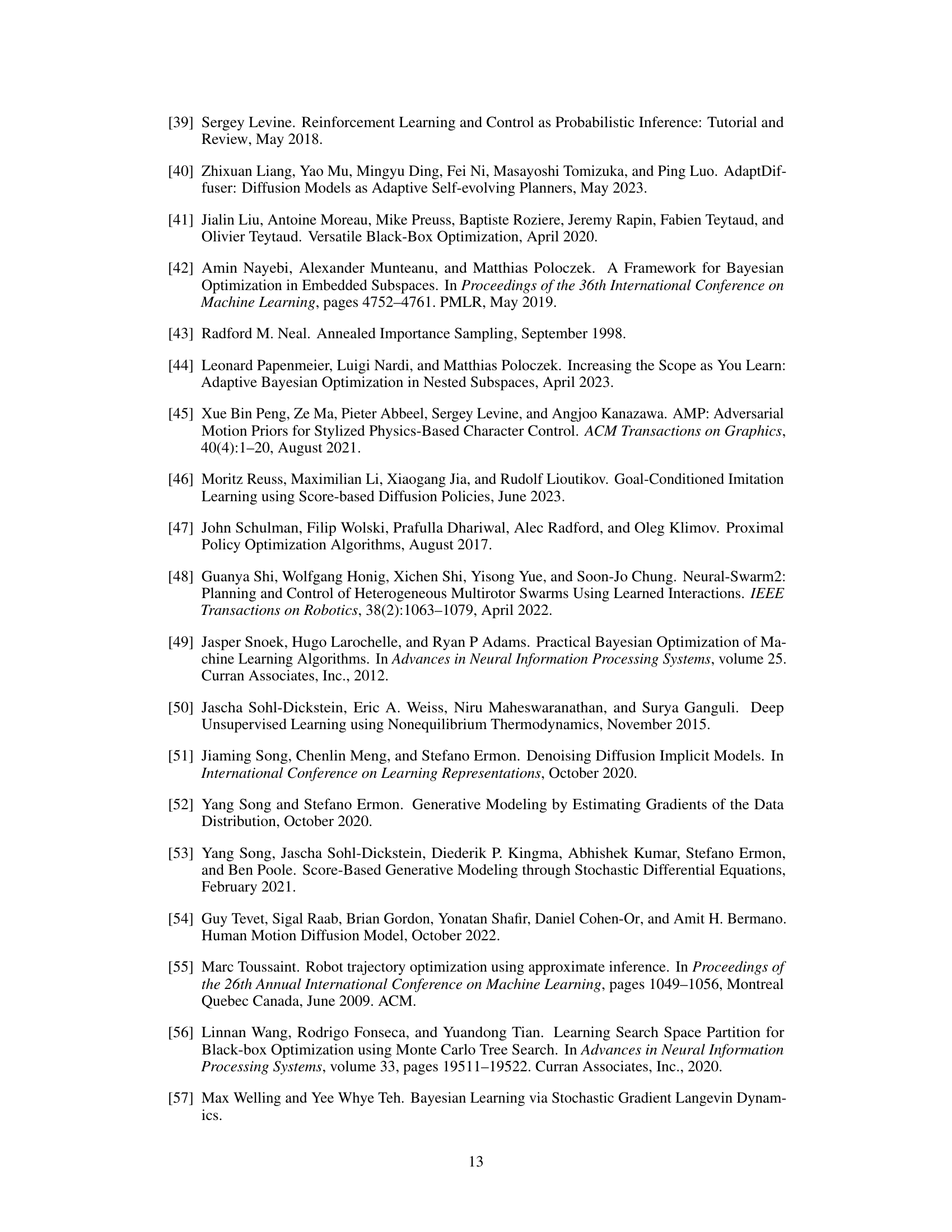

This figure illustrates the Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) framework. The left side shows the model information (dynamics) being used to compute a score function. The right side displays the diffusion process. The diffusion process starts with noisy samples (Y(0)) and iteratively refines them using the computed score function to converge towards optimal and dynamically feasible trajectories (Y(N)). Crucially, the method directly uses the model information rather than relying on demonstration data, making it more generalizable to new scenarios.

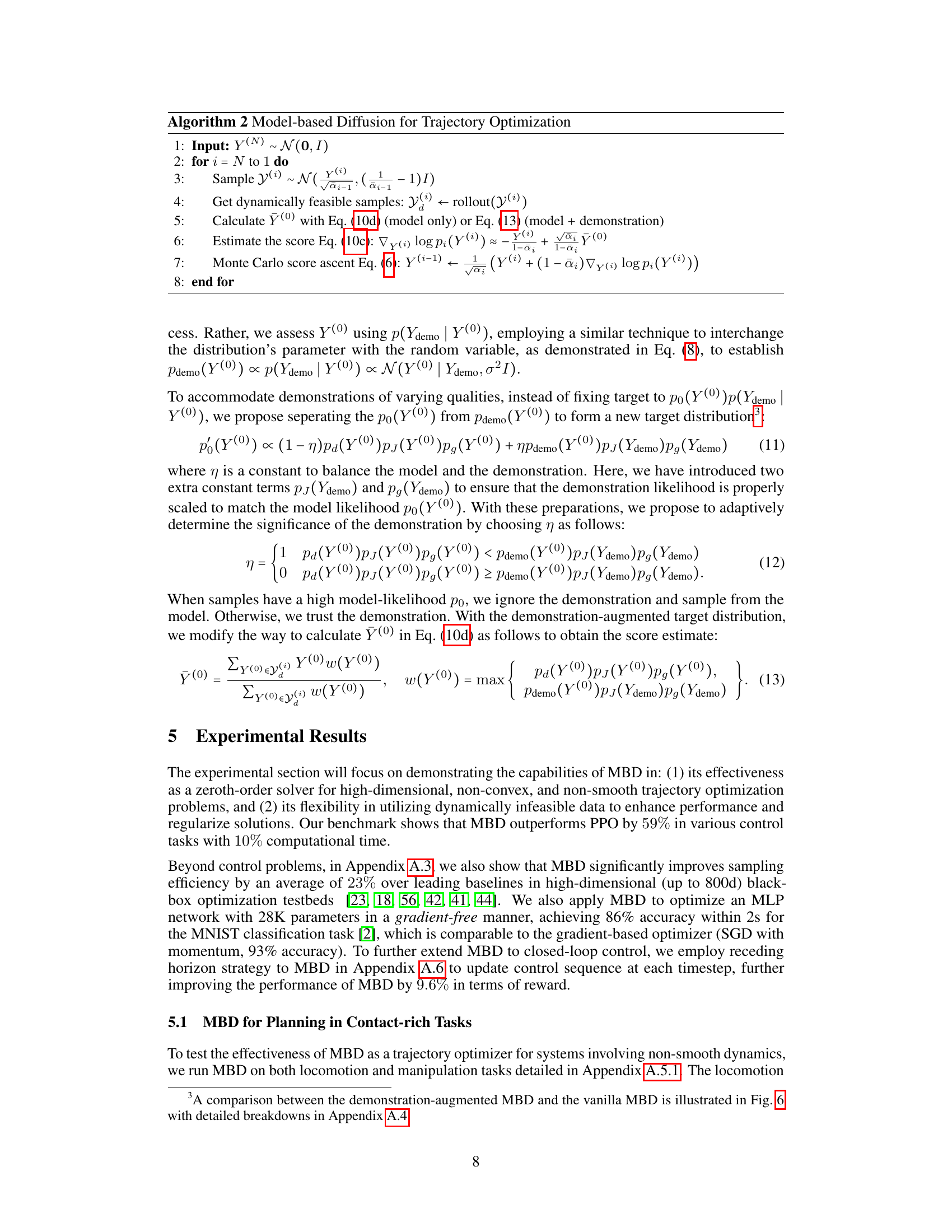

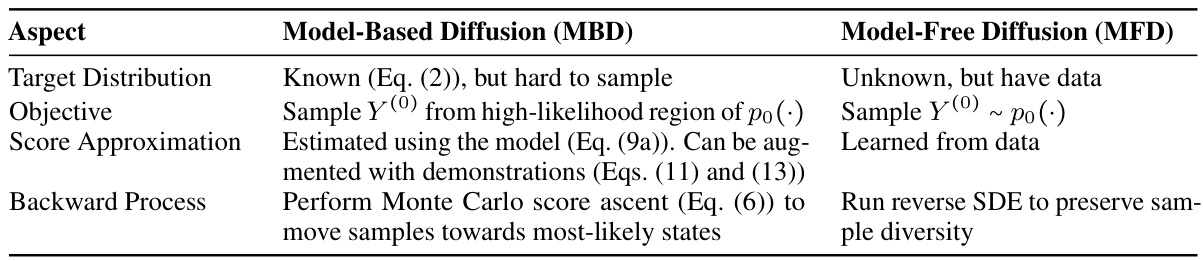

This table summarizes the key differences between Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) and Model-Free Diffusion (MFD). MBD leverages model information to estimate the score function and uses Monte Carlo score ascent to refine samples, while MFD learns the score function from data and uses reverse stochastic differential equations (SDEs). The table highlights differences in the target distribution, objective, score approximation method, and backward process.

In-depth insights#

MBD: A Novel Approach#

The heading ‘MBD: A Novel Approach’ suggests the presentation of a new method, MBD, within a research paper. A thoughtful analysis would delve into the specifics of this approach, exploring its underlying mechanisms and how it differs from existing techniques. Crucially, it necessitates an evaluation of MBD’s advantages and disadvantages, examining its performance, efficiency, and limitations. The discussion should highlight the problem MBD aims to solve, considering the context of the broader research field and the significance of the proposed solution. A comprehensive analysis also needs to explore the practical implications of this new method, considering potential applications, scalability, and ease of implementation. Finally, the summary should consider future research directions, such as potential extensions, improvements, and areas where further investigation is warranted. The overall goal is to provide a clear and concise understanding of MBD and its potential impact.

Model-Based Score#

A model-based score function is a crucial element in bridging the gap between the known dynamics of a system and the probabilistic nature of diffusion models used in trajectory optimization. Instead of relying solely on data-driven methods, a model-based approach leverages explicit knowledge of the system’s dynamics (such as its equations of motion and constraints) to directly estimate the score function. This allows the algorithm to more accurately guide the diffusion process towards desirable solutions, resulting in more efficient and effective trajectory generation, especially in scenarios where data is scarce or of poor quality. The direct integration of model information eliminates the data dependency often found in model-free diffusion methods, thus improving generalization capabilities and reducing the need for large-scale datasets. Furthermore, the accuracy of the score function directly impacts the speed and precision of the diffusion process: a more accurate estimation leads to faster convergence towards the target distribution and ultimately, more efficient trajectory optimization.

Data Augmentation#

Data augmentation, in the context of trajectory optimization using diffusion models, is a powerful technique to enhance model performance and robustness. By integrating diverse data sources, even imperfect or partial demonstrations, the model’s ability to generalize across various scenarios is significantly amplified. Imperfect data, such as dynamically infeasible trajectories from simplified models or partial-state demonstrations from humanoids, can be naturally incorporated to steer the diffusion process. This strategy not only enhances model versatility but also addresses common challenges associated with limited or noisy data. The effectiveness of data augmentation is demonstrated empirically, showcasing enhanced performance in contact-rich tasks and long-horizon sparse-reward navigation problems. The approach seamlessly combines model-based reasoning with data-driven learning, creating a hybrid technique that leverages the strengths of both paradigms. This fusion unlocks significant potential for solving complex, real-world trajectory optimization problems, particularly in high-dimensional and contact-rich scenarios where data scarcity is prevalent.

Contact-rich Tasks#

The section on “Contact-rich Tasks” would delve into the paper’s exploration of trajectory optimization in scenarios involving significant contact interactions. This is a particularly challenging area because contact introduces discontinuities and nonlinearities into the system dynamics, making standard optimization methods less effective. The paper likely showcases how Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) handles these complexities, potentially highlighting its ability to generate dynamically feasible trajectories despite these challenges. A key aspect would be the comparison of MBD’s performance against other state-of-the-art methods specifically designed for contact-rich tasks. The results likely demonstrate MBD’s superior capabilities in achieving high-quality solutions, showcasing its versatility and robustness. Furthermore, it is probable the analysis includes detailed descriptions of the specific contact-rich tasks used for evaluation, providing insights into the diversity and difficulty of the problems addressed. The discussion might extend to considerations of how MBD handles imperfect or partial data, such as noisy observations or limited sensory information, emphasizing the practical applicability of the method even in scenarios with limited or noisy information.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of this research paper would ideally delve into several key areas. First, a rigorous theoretical analysis of the model’s convergence properties is crucial, moving beyond empirical observations to establish a solid mathematical foundation. Second, exploring alternative sampling methods and advanced scheduling techniques beyond the standard Gaussian forward process could significantly improve efficiency and robustness. Integrating model uncertainty into the score function estimation would enhance the system’s reliability, especially when dealing with imperfect or incomplete models. The section should also discuss the applicability of this approach to online, real-time control tasks, requiring the design of efficient receding-horizon implementations. Finally, investigating the potential of combining model-based diffusion with other optimization techniques such as reinforcement learning or evolutionary algorithms to leverage their respective strengths, would open up exciting new avenues for trajectory optimization in complex, high-dimensional scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

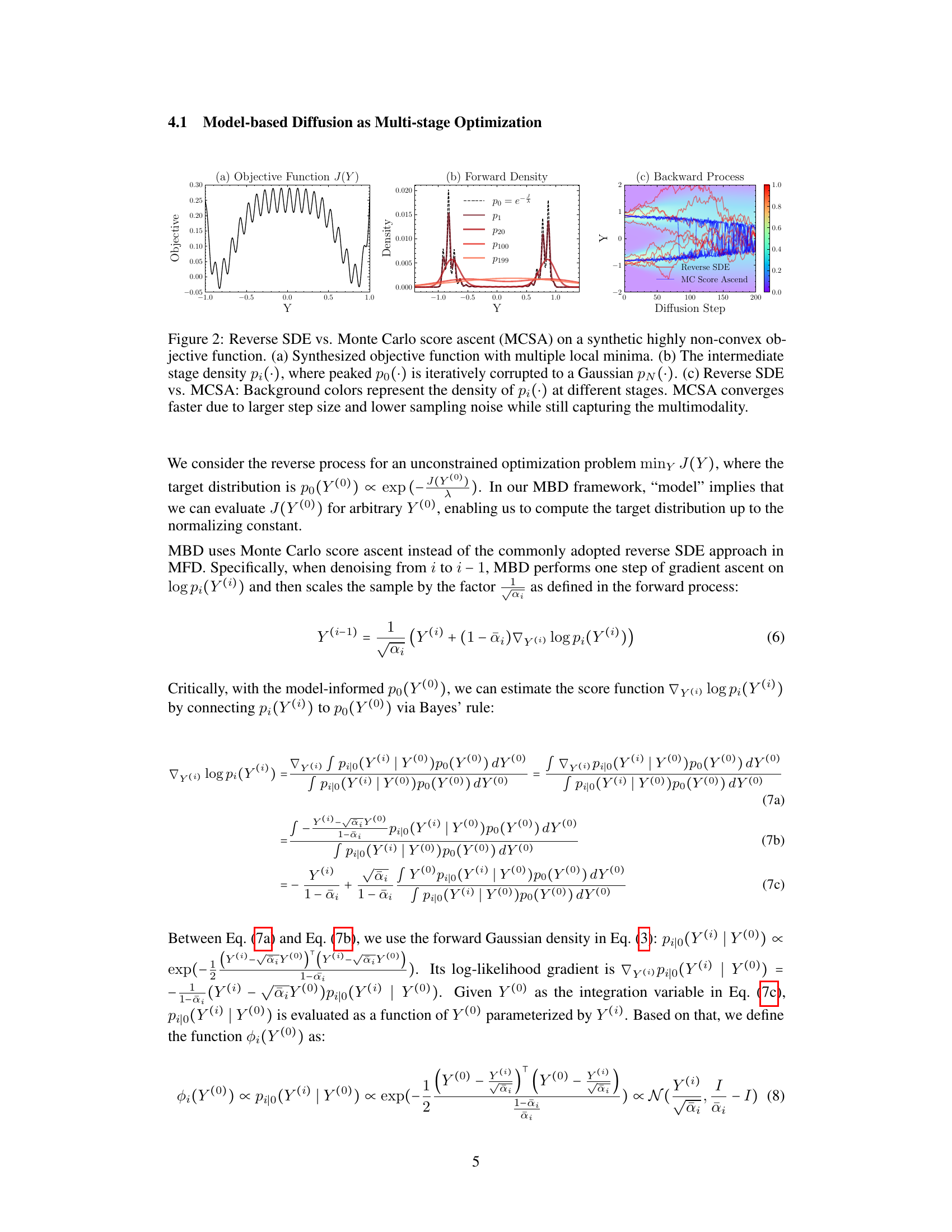

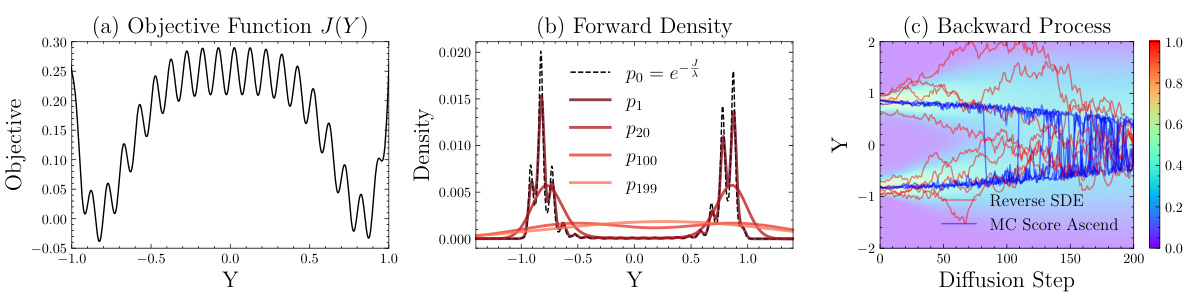

This figure compares Reverse Stochastic Differential Equations (SDE) and Monte Carlo Score Ascent methods for optimization on a synthetic, highly non-convex objective function with multiple local minima. Subfigure (a) shows the objective function. Subfigure (b) illustrates how the forward diffusion process iteratively corrupts the target distribution into a Gaussian distribution. Subfigure (c) visually compares the reverse SDE and MC Score Ascent processes in terms of convergence speed and the density of intermediate distributions, highlighting MC Score Ascent’s faster convergence and ability to capture multimodality.

This figure shows the results of applying Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) to two different tasks: humanoid jogging and car navigation in a U-maze. The left panel (a) illustrates the humanoid jogging task. It shows that using data augmentation (MBD with data) leads to a more regularized and refined trajectory compared to using MBD without data. The right panel (b) demonstrates the car navigation task. Again, the addition of data augmentation results in a trajectory that is better refined and achieves the objective more effectively. In both examples, MBD benefits from incorporating external data to improve trajectory optimization.

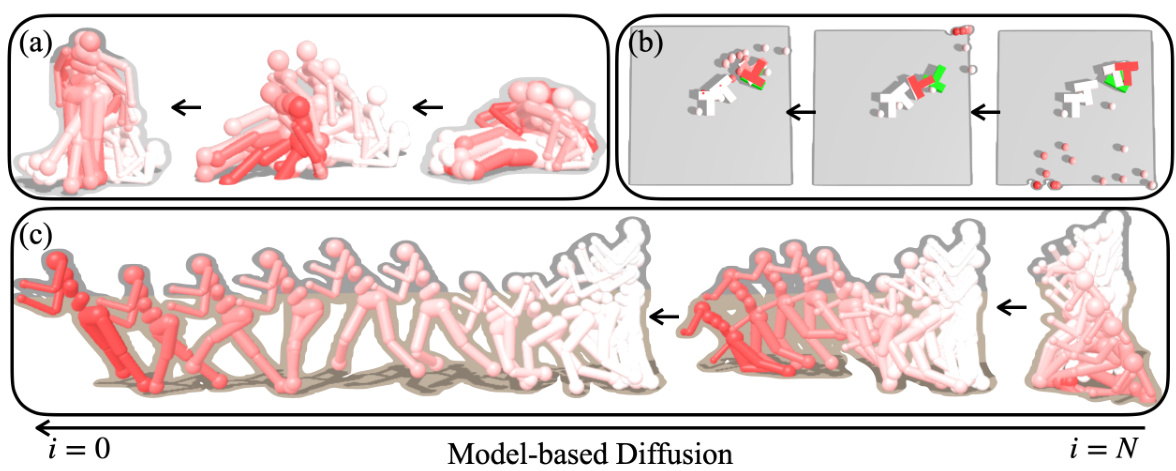

This figure shows the iterative refinement process of the Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) algorithm across three different tasks: Humanoid Standup, Push T, and Humanoid Running. Each subfigure illustrates the evolution of the trajectory from an initial, noisy state (i=0) to a refined, optimized trajectory (i=N). The color gradient represents the refinement process, moving from light to dark shades as the optimization progresses. The figure demonstrates MBD’s ability to leverage model information to effectively navigate high-dimensional state spaces and achieve the desired objective.

This figure compares the Reverse Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) approach with the Monte Carlo Score Ascent (MCSA) method for solving a synthetic highly non-convex optimization problem. Subfigure (a) shows the objective function with multiple local minima. Subfigure (b) illustrates the forward diffusion process, where the target distribution is iteratively corrupted into a Gaussian distribution. Subfigure (c) visually contrasts the reverse SDE and MCSA methods, highlighting MCSA’s faster convergence due to its larger step size and reduced sampling noise. Despite the faster convergence, MCSA successfully captures the multimodality of the distribution.

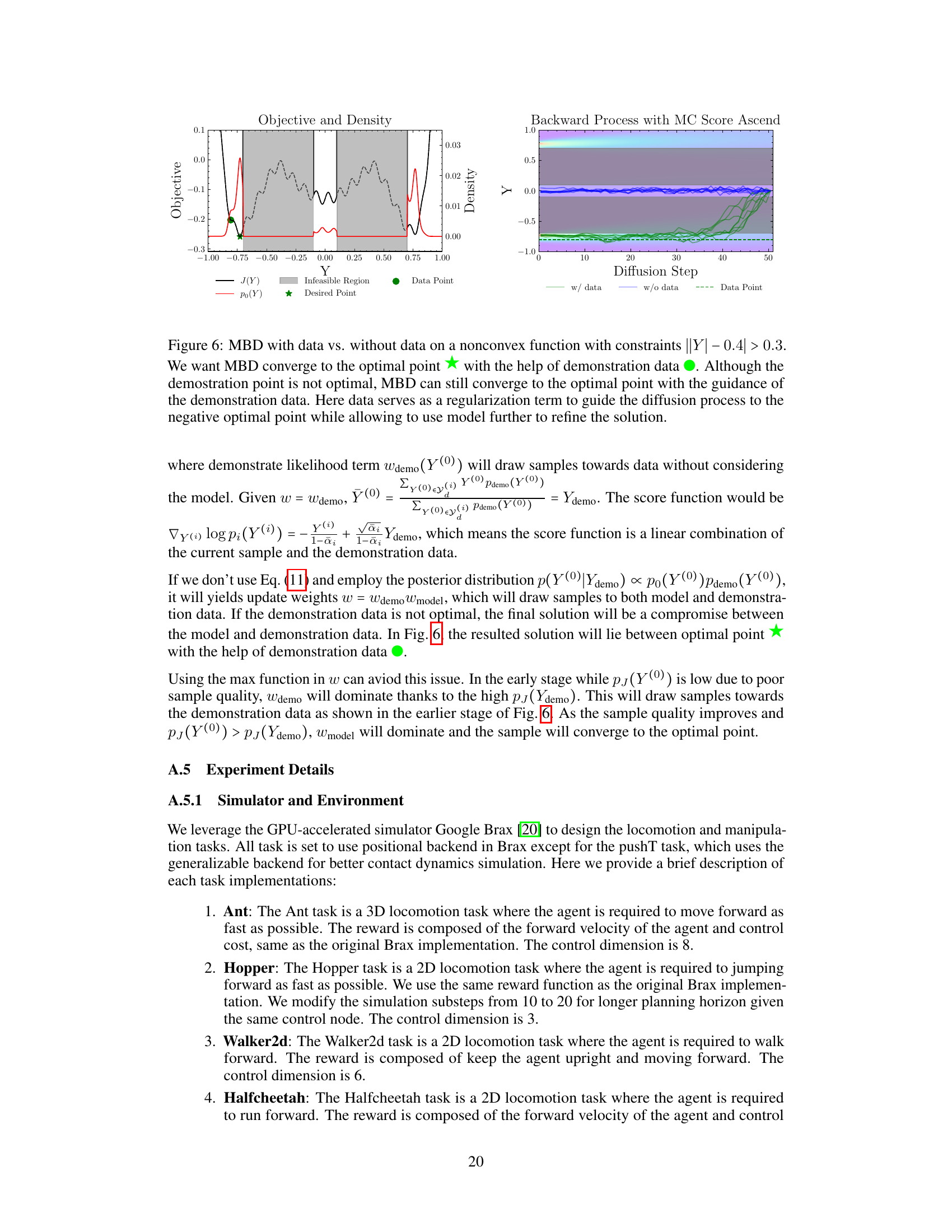

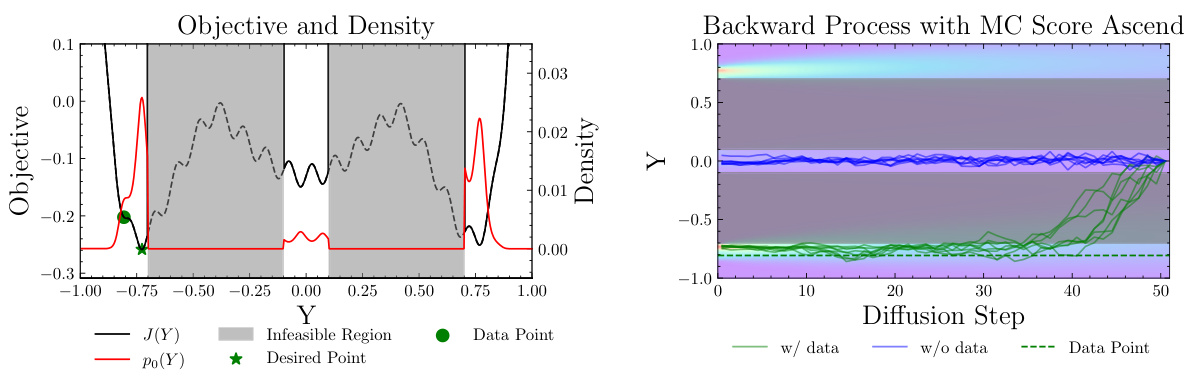

This figure shows a comparison of Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) with and without demonstration data on a non-convex function with constraints. The left panel displays the objective function and probability density of the target distribution, showing a non-convex landscape with an optimal solution, infeasible regions, and a demonstration data point that is not optimal. The right panel illustrates the backward diffusion process using Monte Carlo score ascent, demonstrating how the addition of demonstration data guides the diffusion process towards the optimal solution. In the absence of demonstration data, the sampling process struggles to converge on the optimum. The data acts as a form of regularization, drawing the process toward a good region, after which the model is able to refine the solution.

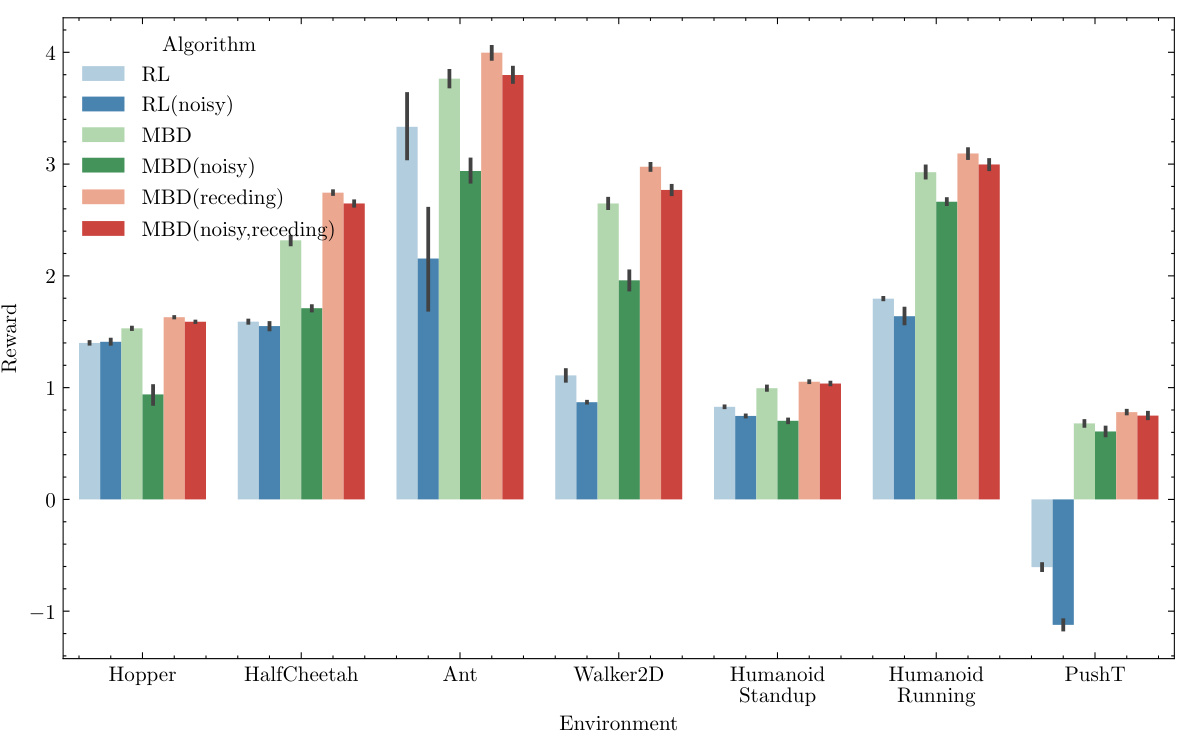

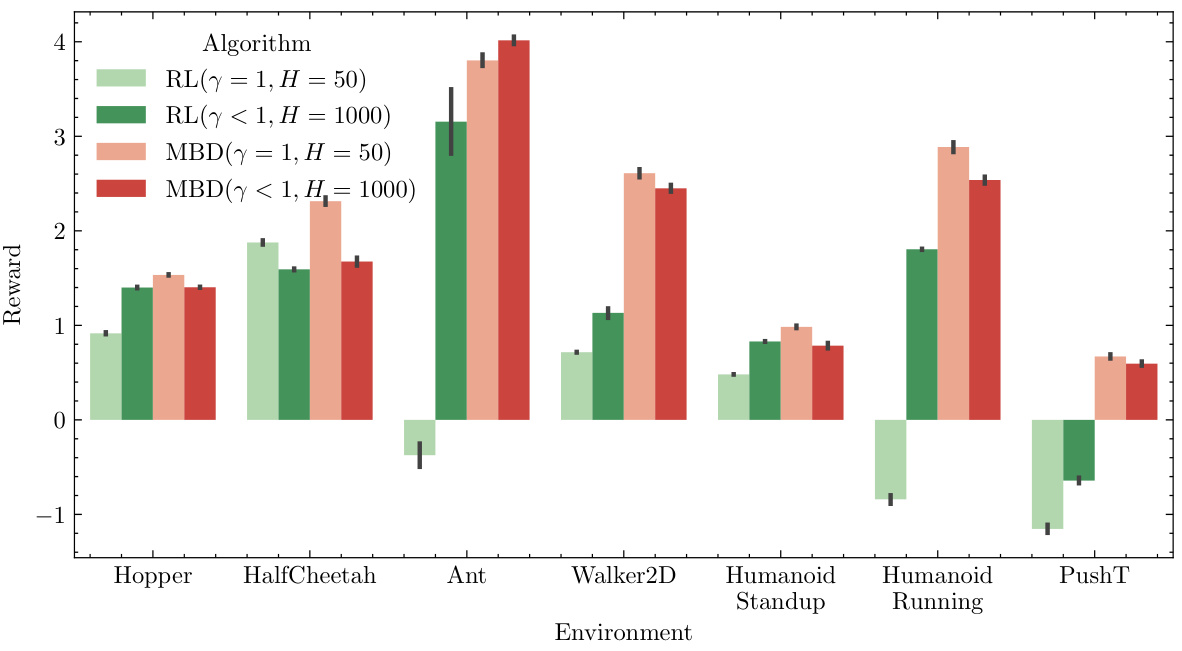

This figure compares the performance of Reinforcement Learning (RL), Model-Based Diffusion (MBD), and a receding horizon version of MBD under both ideal and noisy conditions. With a perfect model, the receding horizon MBD improves upon standard MBD, significantly outperforming RL. Even when 5% control noise is introduced, the receding horizon MBD maintains a substantial performance advantage over RL.

This figure compares the performance of Reverse Stochastic Differential Equations (SDE) and Monte Carlo Score Ascent (MCSA) methods on a synthetic highly non-convex objective function with multiple local minima. Panel (a) shows the objective function. Panel (b) illustrates the iterative corruption of the target distribution (peaked po(·)) into a Gaussian distribution (pv(·)) during the forward diffusion process. Panel (c) visually compares the reverse SDE and MCSA processes, highlighting the faster convergence of MCSA due to its larger step size and reduced sampling noise while maintaining the multimodality of the distribution.

This figure compares the performance of Reinforcement Learning (RL), Model-Based Diffusion (MBD), and a receding horizon version of MBD across various control tasks. Both perfect and noisy (5% control noise) model scenarios are evaluated. The results demonstrate the improved performance of MBD, especially when a receding horizon approach is used.

More on tables

This table compares Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) and Model-Free Diffusion (MFD) methods across several key aspects. It highlights the differences in how they approach the target distribution, the objective of the sampling process, the score approximation technique used, and the nature of the backward diffusion process. MBD leverages model information for score approximation and aims to sample from high-likelihood regions of the target distribution, while MFD learns the score function from data and relies on reverse stochastic differential equations to move samples towards the data distribution. The table effectively summarizes the key distinctions between the model-based and model-free approaches to diffusion-based trajectory optimization.

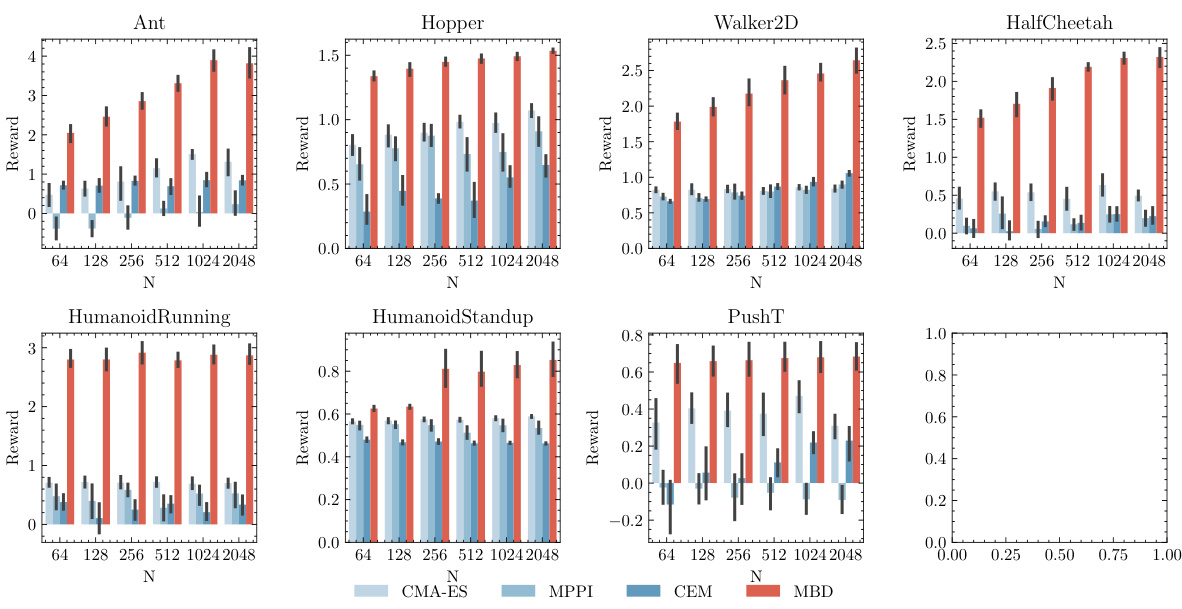

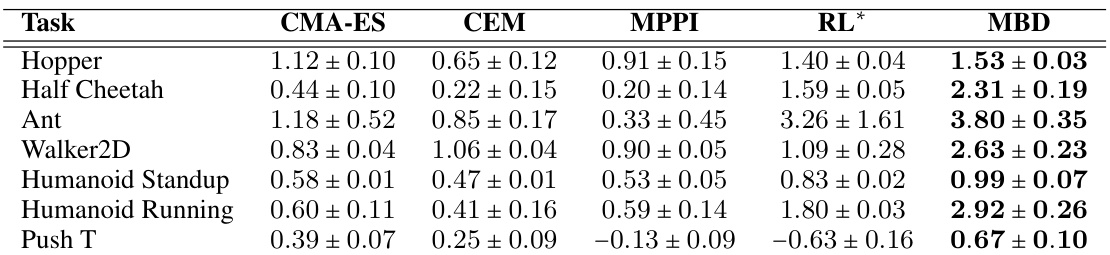

This table compares the performance of different trajectory optimization methods on several non-continuous control tasks. The methods compared include CMA-ES, CEM, MPPI, a reinforcement learning (RL) approach, and the proposed Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) method. The table shows the average reward achieved by each method on each task. The RL method is marked with an asterisk (*) to indicate that it uses offline training and a closed-loop policy, making it not directly comparable to the other methods, which are model-free.

This table presents the computational time required by different trajectory optimization methods (CMA-ES, CEM, MPPI, RL, and MBD) to solve several non-continuous control tasks. The results highlight the efficiency of model-based diffusion (MBD) compared to other approaches, particularly reinforcement learning (RL).

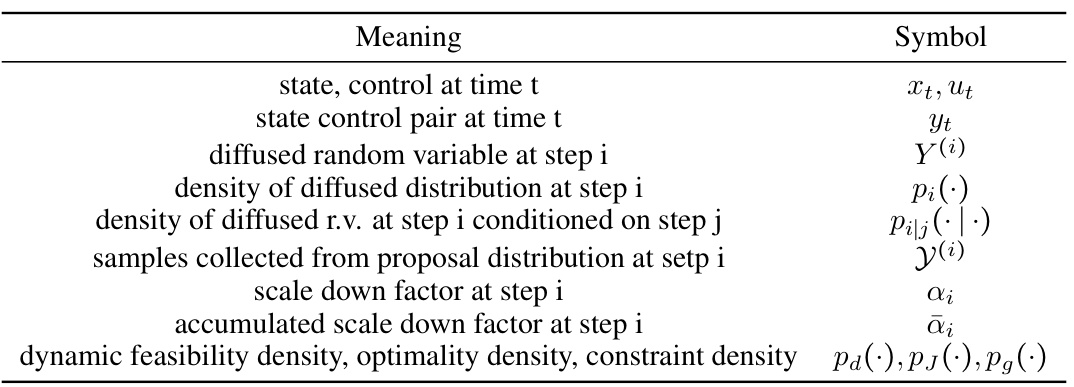

This table highlights the key differences between Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) and Model-Free Diffusion (MFD). MBD leverages model information to estimate the score function, while MFD learns it from data. MBD uses Monte Carlo score ascent to quickly move samples to high-density regions, whereas MFD uses reverse stochastic differential equations to maintain sample diversity. MBD assumes a known target distribution, which is different from MFD.

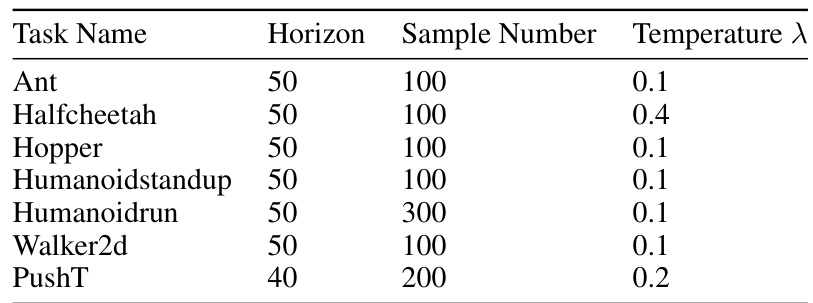

This table shows the hyperparameters used for the Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) algorithm across different tasks. It specifies the horizon length (number of time steps considered in each optimization iteration), the number of samples used to estimate the score function at each step, and the temperature parameter (λ), which controls the exploration-exploitation tradeoff in the diffusion process.

This table shows the hyperparameters used for training reinforcement learning (RL) agents in different robotic control tasks. The table lists the environment, the RL algorithm used (PPO or SAC), the number of timesteps for training, the reward scaling factor applied, and the length of each episode.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training reinforcement learning (RL) agents in various simulated robotic environments. The hyperparameters include the minibatch size, the number of updates per batch, the discount factor, and the learning rate. These settings are crucial for achieving optimal performance in each environment and are specific to the RL algorithms used in the paper.

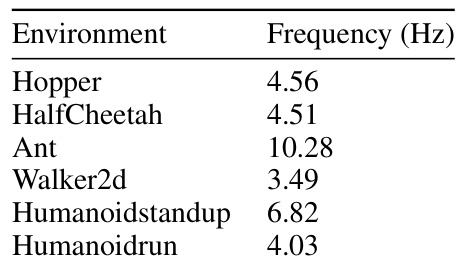

This table shows the online running frequency of the receding horizon version of Model-Based Diffusion (MBD) for various locomotion tasks. The frequency is measured in Hertz (Hz) and represents how many times per second the MBD algorithm can replan a trajectory using a receding horizon approach. The values indicate the computational efficiency of MBD for online control.

Full paper#