↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional sequence models, like SSMs, often struggle with complex data exhibiting inherent modularity (e.g., multiple interacting objects in a video). This limits their ability to effectively capture long-range temporal dependencies and understand the interactions between different components within the data. Furthermore, methods such as RNNs, often used for modularity, suffer from limitations in parallel training and long-range dependency modeling.

This research introduces SlotSSMs, a new framework that tackles these challenges. SlotSSMs achieve this by maintaining a set of independent “slots” instead of a single monolithic state vector. Each slot processes information independently, and sparse interactions between slots are introduced via self-attention. The experiments demonstrate significant performance improvements of SlotSSMs over existing models across various tasks involving object-centric learning, 3D visual reasoning, and video understanding, showcasing the effectiveness of its modular design.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on sequence modeling, particularly those dealing with complex, modular data. SlotSSMs offer a significant advancement in handling long-range dependencies and modularity, providing a more efficient and interpretable alternative to existing methods. This opens doors for further research in object-centric learning, video understanding and more complex sequence modeling tasks.

Visual Insights#

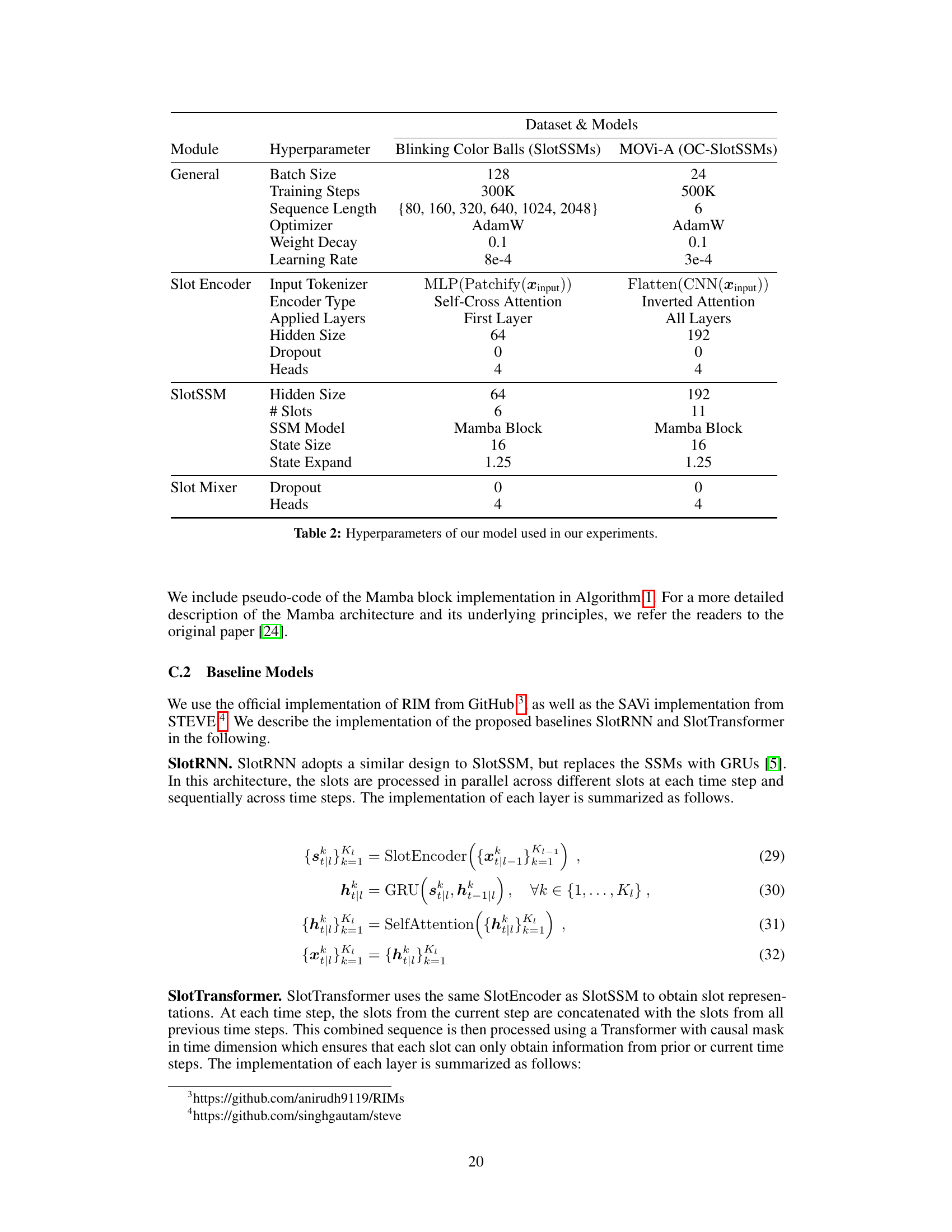

This figure compares SlotSSMs with other state-of-the-art sequence models. (a) shows the SlotSSM architecture, highlighting its modularity through independent slot state transitions and sparse inter-slot interactions using self-attention. (b) depicts traditional SSMs with a monolithic state vector. (c) illustrates Transformer-based models, showing their high computational complexity despite offering modularity. (d) showcases RNN-based models with modular states but limited parallelization capabilities. The figure emphasizes SlotSSMs’ advantages in combining parallelizable training, memory efficiency, and modularity for improved temporal modeling.

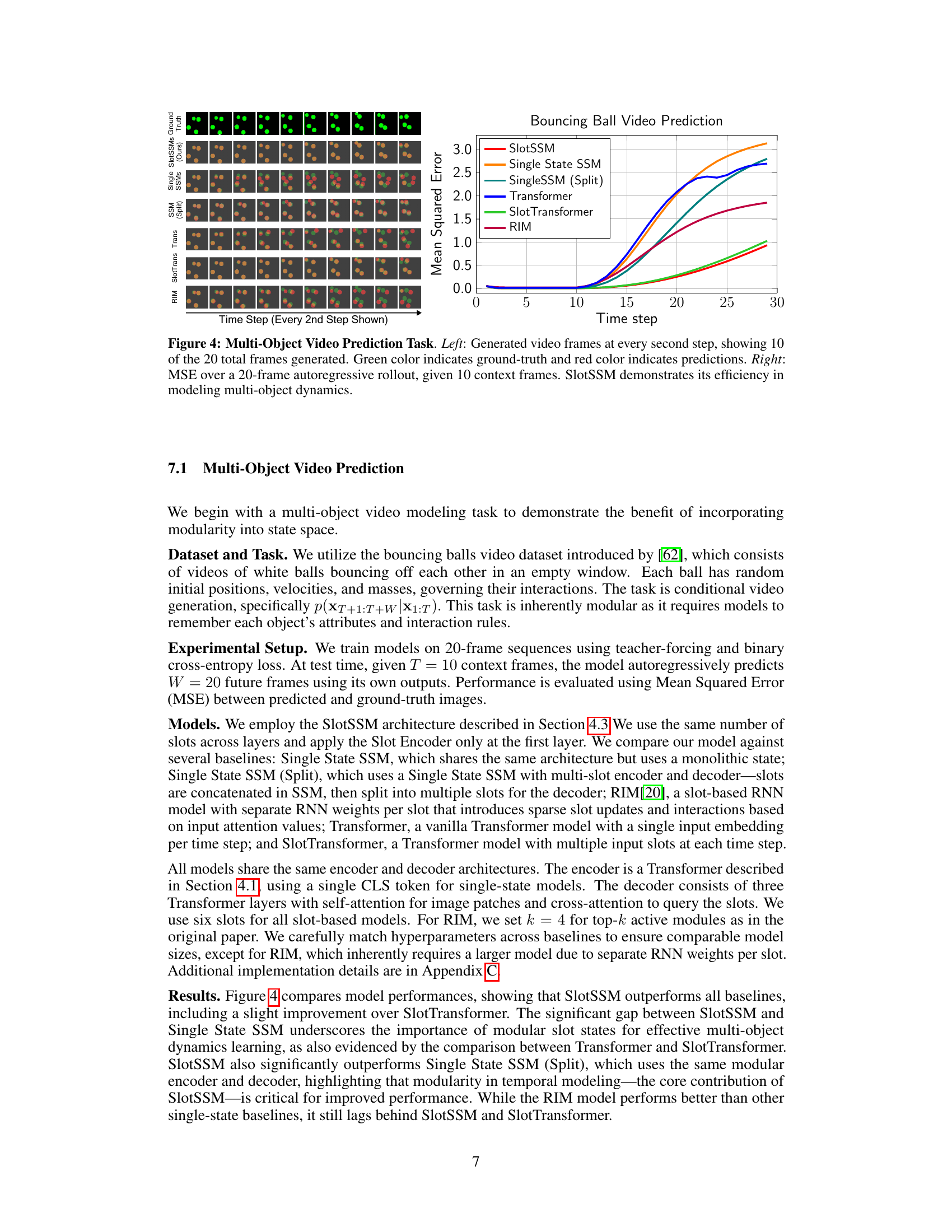

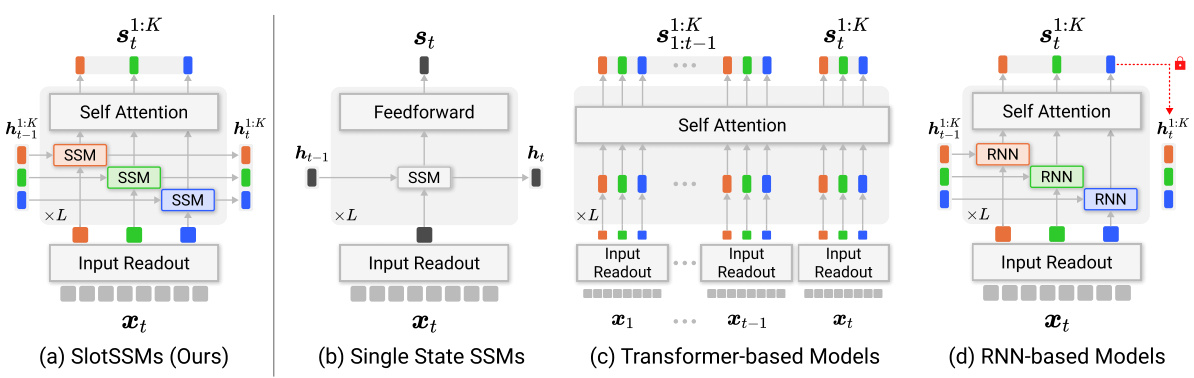

This table presents the results of the CATER Snitch Localization task, which evaluates the ability of models to predict the location of a hidden object in a 3D environment. The table shows the top-1 and top-5 accuracy for four different models: Single State SSM, SlotTransformer, SlotSSM, and OC-SlotSSM. The results are broken down into two categories: ‘No Pre-train’, where models are trained directly on the task, and ‘Pre-train’, where models are first pre-trained on a reconstruction objective and then fine-tuned on the task.

In-depth insights#

Modular SSMs#

Modular State Space Models (SSMs) represent a significant advancement in sequence modeling, addressing limitations of traditional monolithic SSMs. By decomposing the state vector into independent modules or “slots,” modular SSMs enable the parallel processing of information, leading to increased efficiency. This modularity is particularly advantageous when modeling systems with inherent modularity, such as those involving multiple interacting objects or components. The independent updates within each slot allow for more efficient handling of long-range dependencies, while sparse interactions between slots, often implemented using self-attention, facilitate the modeling of complex relationships. This approach leads to performance gains in various applications, including object-centric learning, 3D visual reasoning, and video understanding. However, challenges remain in effectively learning the optimal number and interactions of slots, and further research is needed to explore the theoretical properties and generalization capabilities of this promising architecture.

SlotSSM Design#

The SlotSSM design cleverly addresses the limitations of traditional SSMs by incorporating modularity and parallel processing. Instead of a monolithic state vector, it uses multiple independent state vectors called ‘slots’, each processing information independently. This modularity allows the model to handle sequences with inherently modular structures, such as those involving multiple objects or interacting entities, significantly improving efficiency and generalization, especially for long sequences. Sparse interactions between slots are introduced using self-attention, which acts as a bottleneck to prevent excessive entanglement of information. Parallel training becomes feasible due to the independent slot updates. The design also offers flexibility, with the number of slots potentially varying across layers to achieve different levels of abstraction. SlotSSMs effectively combine the strengths of SSMs (efficiency, long-range memory) with inductive biases promoting the discovery and preservation of modular structures within the data, leading to substantial performance gains over conventional methods, particularly in complex, real-world sequence modeling tasks.

Object-centric Tests#

In the realm of object-centric learning, a dedicated evaluation section focusing on ‘Object-centric Tests’ would be crucial. It should go beyond simple metrics like accuracy or Intersection over Union (IoU) for segmentation, and instead delve into the model’s true understanding of object identities and interactions. Comprehensive tests should assess the model’s robustness to occlusion, variations in object appearance, and changes in the number of objects in a scene. These should involve controlled experiments with varying degrees of complexity to determine if the model can accurately track and classify objects even under challenging conditions. Furthermore, evaluating the model’s ability to disentangle object properties (e.g., shape, color, position, motion) and relationships is critical. This evaluation should examine if the model’s latent representations capture distinct and independent object dynamics or if it intermingles properties, hindering generalization and understanding. Specific tests could involve generating videos with interactions and requiring predictions of future states, providing a comprehensive benchmark for models claiming to have object-centric capabilities. The inclusion of qualitative analyses, like visualizing the model’s attention maps or examining the learned object representations, would further enhance the insightfulness of such an ‘Object-centric Tests’ section.

Long-range tasks#

Long-range dependency modeling is crucial for many sequence prediction tasks. The challenge lies in capturing and utilizing information from distant past time steps without incurring excessive computational costs or performance degradation. This is particularly relevant in domains such as video and language modeling, where context spans many time steps. The paper explores techniques that tackle this challenge. Successful approaches often rely on carefully designed model architectures and inductive biases that encourage efficient long-range information integration, and ways to avoid vanishing gradients. The proposed SlotSSMs and variants address this by incorporating inherent modularity through independent state transitions and sparse interactions allowing for efficient parallel training and memory use. The effectiveness of these methods is demonstrated on long-range tasks including those involving multiple interacting objects which require tracking dependencies across multiple entities. Evaluation is crucial, requiring benchmarks specifically designed to assess long-range dependencies, going beyond simple sequence length comparisons. These benchmarks help highlight the strengths of the new techniques over previous approaches, revealing capabilities in capturing complex and modular dynamic systems.

Future of SlotSSMs#

The future of SlotSSMs appears bright, given their demonstrated success in handling modular sequence data. Further research could focus on enhancing the slot encoder, perhaps by incorporating more sophisticated mechanisms for discovering and representing latent object-centric structures from unstructured inputs. Exploring different slot interaction strategies beyond sparse self-attention could lead to improved performance on tasks requiring complex interdependencies. Scaling SlotSSMs to handle even larger sequences and higher-dimensional data while maintaining computational efficiency is another important area. This might involve novel architectural innovations or efficient approximations of the self-attention mechanism. Investigating the application of SlotSSMs to other modalities beyond the ones explored in the paper (image, video) will broaden their impact. Finally, a deeper theoretical understanding of SlotSSMs’ capabilities and limitations is crucial for further advancements, particularly regarding their generalization ability and the robustness of their modularity under varying conditions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

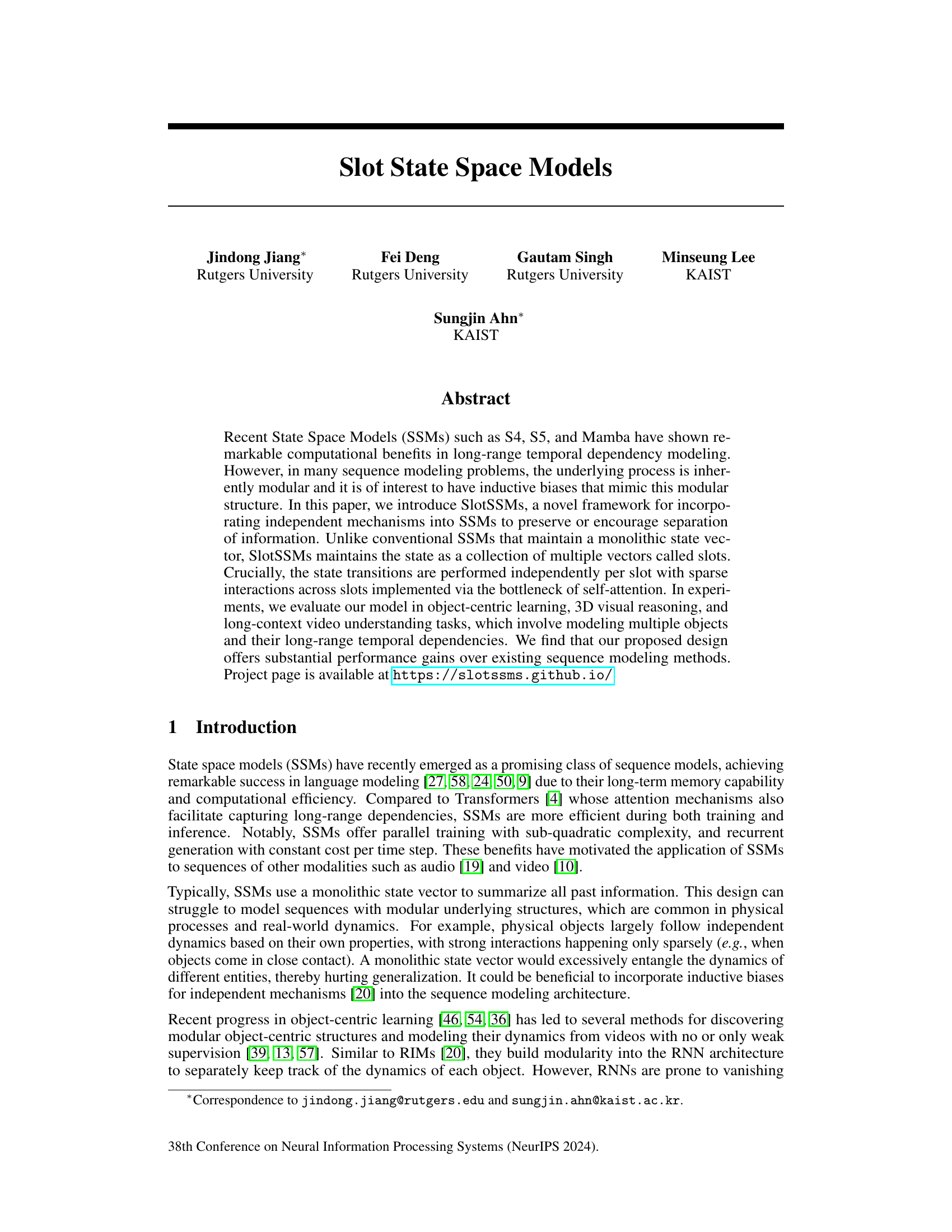

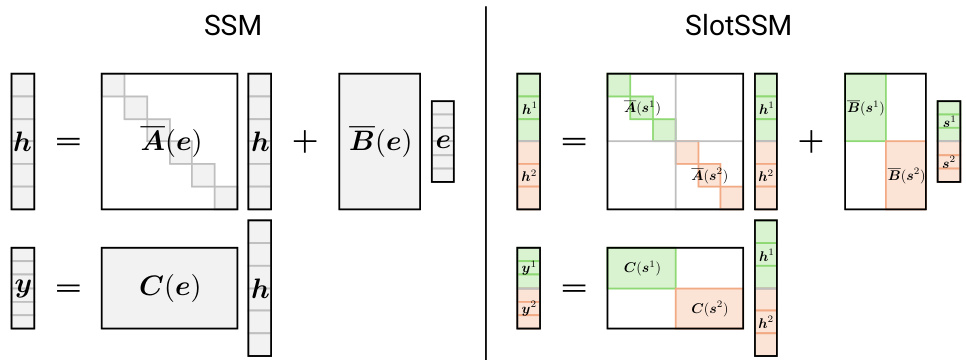

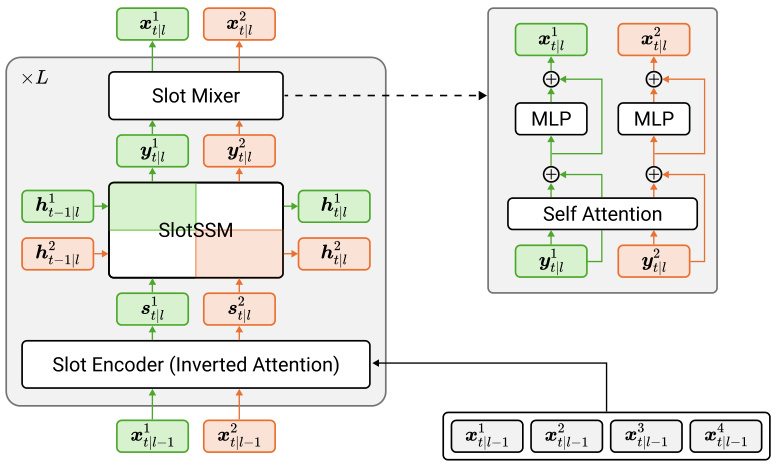

This figure compares the traditional SSMs and the proposed SlotSSMs. In SSMs, the input, hidden states, and output are monolithic vectors where all dimensions are mixed. SlotSSMs, on the other hand, decompose the input, hidden states, and output into multiple vectors called slots. These slots are processed independently with minimal interactions between slots via self-attention. This modularity allows SlotSSMs to model complex sequences with underlying modular structures more efficiently.

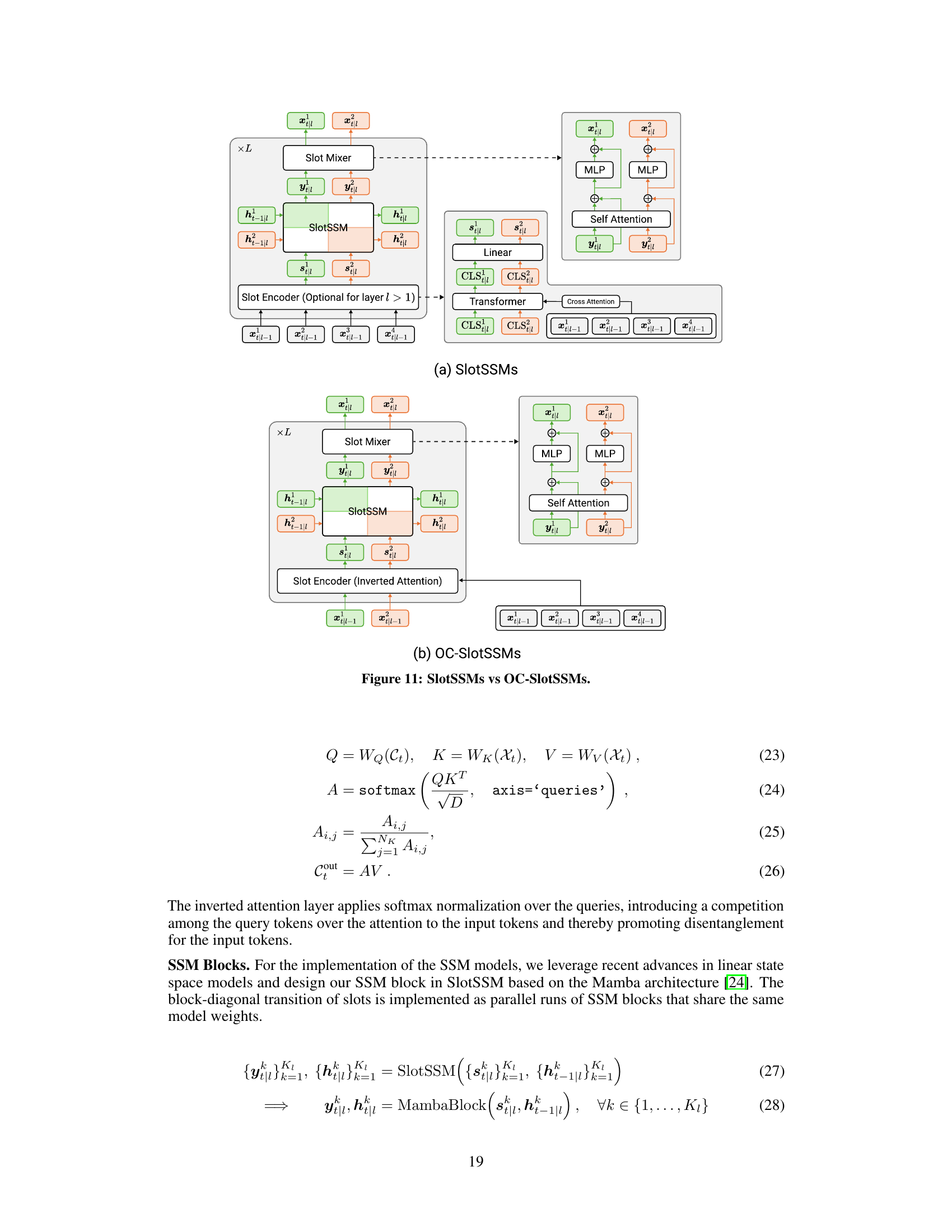

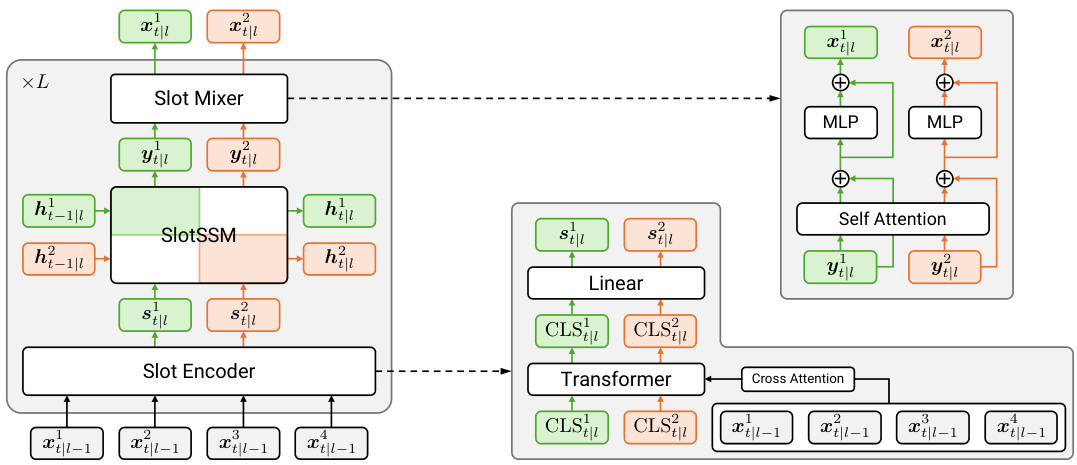

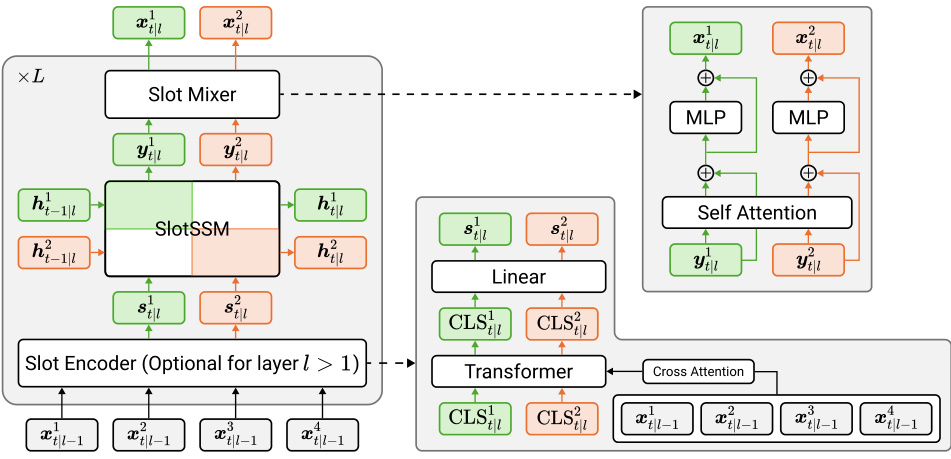

This figure illustrates the architecture of the SlotSSM model for sequence modeling. It shows how each layer of the model consists of three main components: a Slot Encoder, a SlotSSM, and a Slot Mixer. The Slot Encoder uses a Transformer network to extract slot representations from the input sequence. Each slot is then processed independently by the SlotSSM component, which updates its state based on its own previous state and input. Finally, the Slot Mixer uses a self-attention mechanism to introduce sparse interactions between the different slots, allowing them to influence one another. This modular architecture is designed to capture the underlying modular structure of the data.

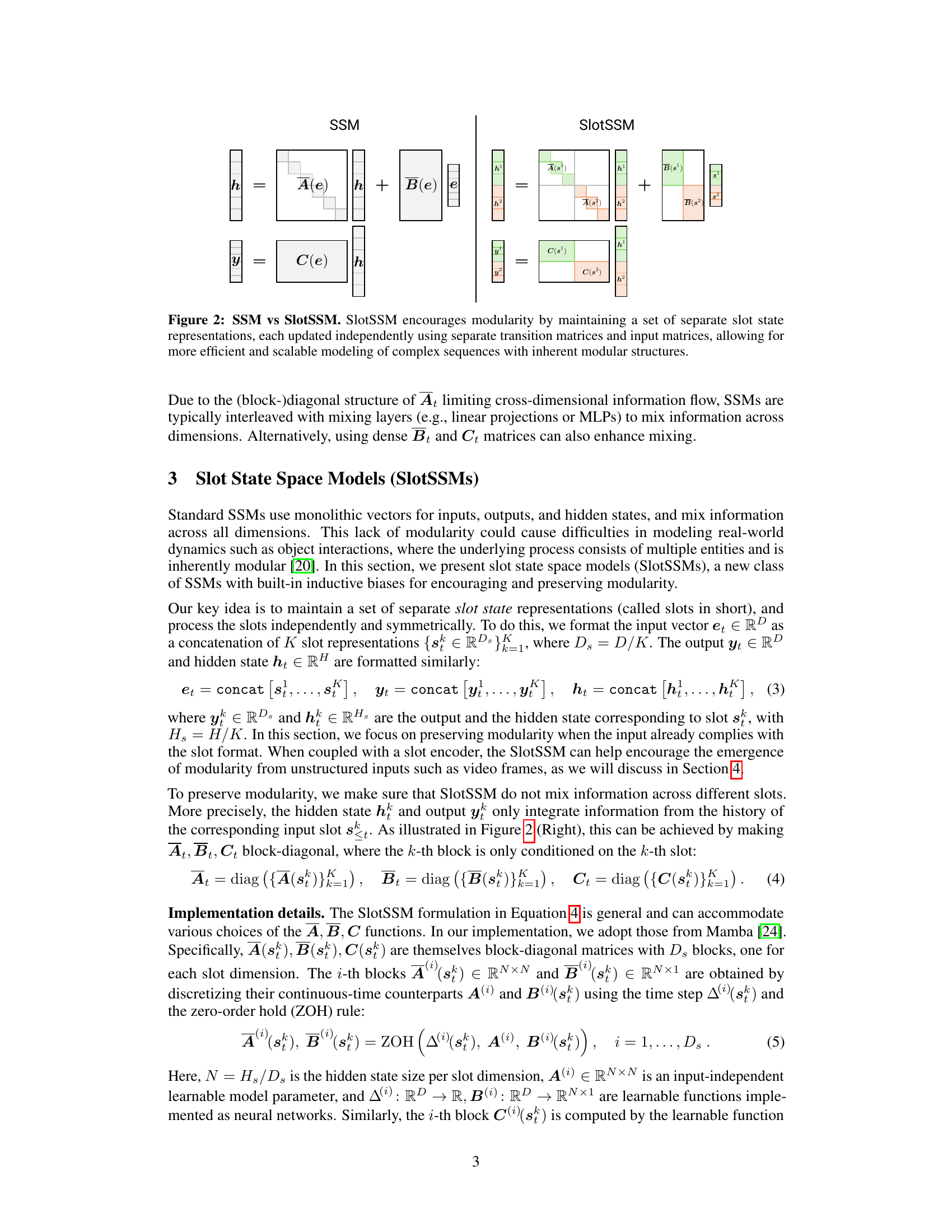

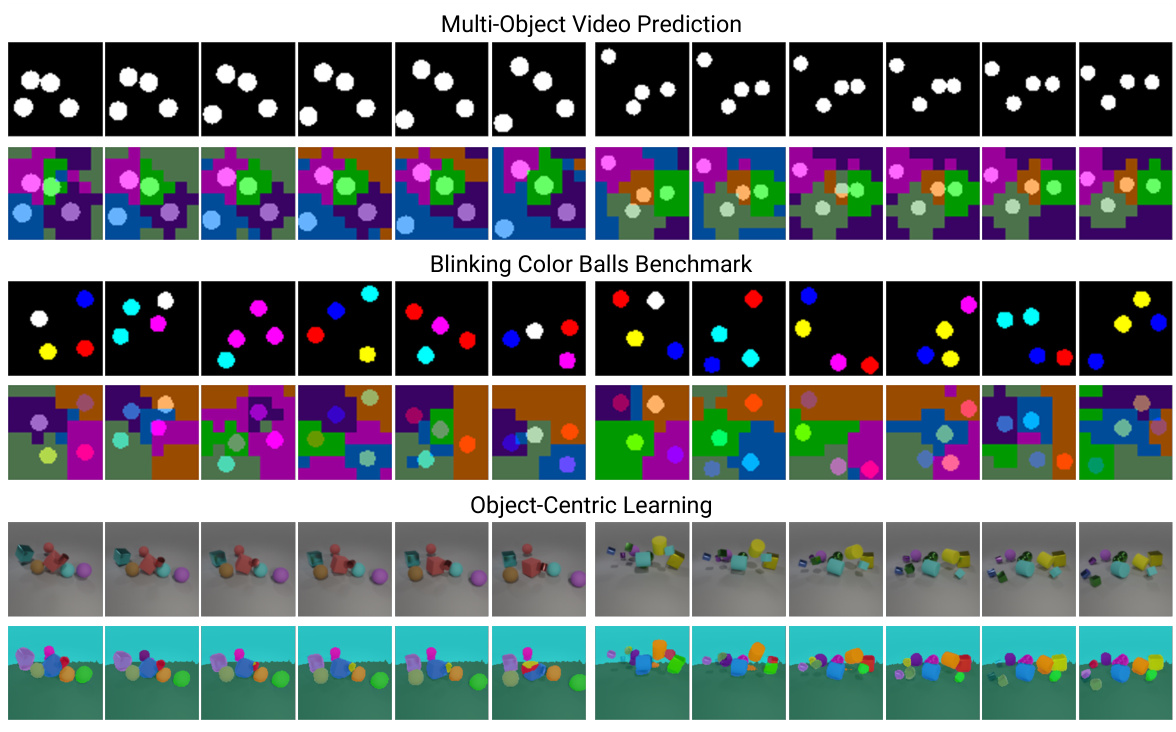

This figure presents a comparison of different models’ performance on a multi-object video prediction task. The left side shows example video frames generated by each model compared to the ground truth. The right side shows a graph plotting the mean squared error (MSE) over a 20-frame prediction, demonstrating that SlotSSM is more efficient in modeling the dynamics of multiple objects.

This figure demonstrates two key aspects of the SlotSSM model in the context of a long-sequence processing task. The left panel shows how the model processes long input sequences by dividing the input images into patches which are then fed to the model sequentially. The right panel shows the inference latency for the model on sequences of varying length, demonstrating its computational efficiency compared to other models.

The figure shows the results of a multi-object video prediction task using the proposed SlotSSM model and several baselines. The left panel displays generated video frames at every other step (10 out of 20 total frames), comparing ground truth (green) with model predictions (red). The right panel presents the mean squared error (MSE) for a 20-frame autoregressive rollout, given the first 10 frames as context. The results demonstrate that SlotSSM effectively models multi-object dynamics.

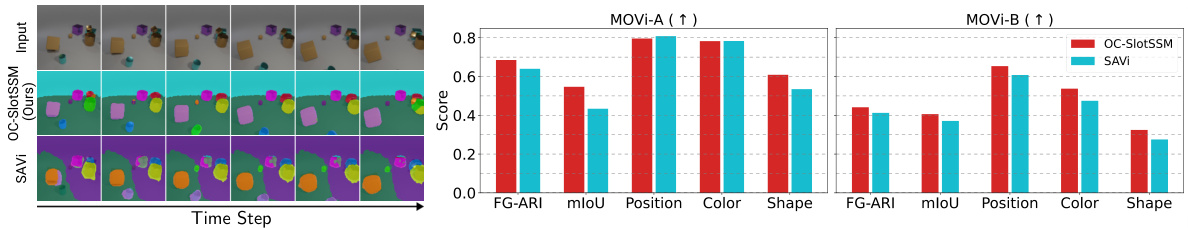

This figure presents a qualitative and quantitative comparison of the results for unsupervised object-centric learning on the MOVI-A and MOVI-B datasets using OC-SlotSSM and SAVi. The left side shows a qualitative comparison of the segmentation masks generated by both methods, highlighting the improved boundary adherence and reduced object splitting achieved by OC-SlotSSM. The right side displays a bar chart summarizing the quantitative performance of both models in terms of FG-ARI, mIoU, position, color, and shape prediction metrics. This comparison demonstrates that OC-SlotSSM surpasses SAVi across all metrics, demonstrating its superiority in object-centric representation learning.

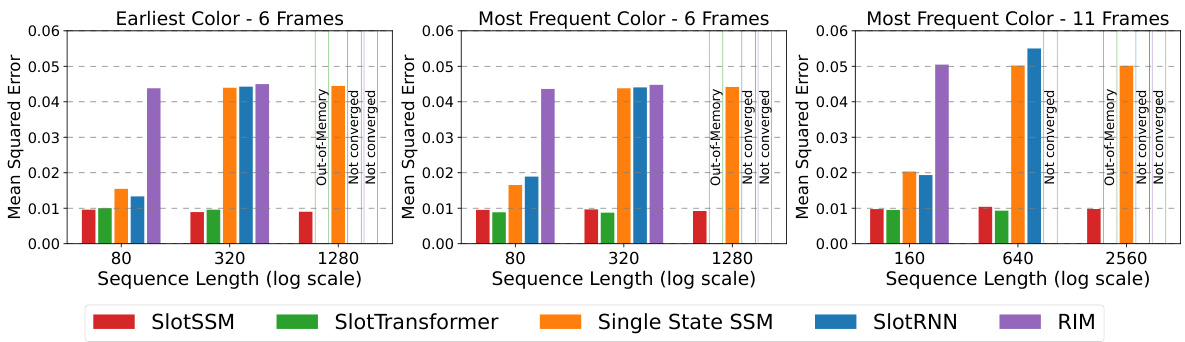

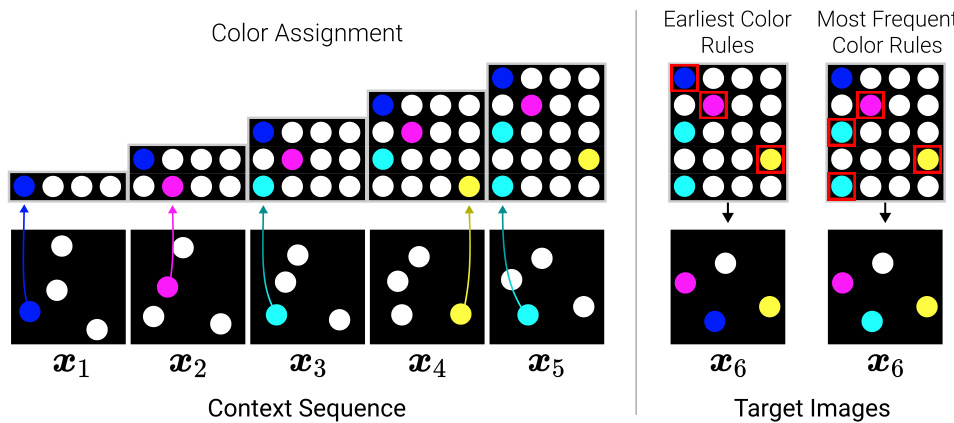

This figure illustrates the design of the Blinking Color Balls Benchmark dataset. The left side shows the context frames, where each frame depicts multiple balls, and one ball is randomly selected and assigned a color in each frame. The color assignment process is independent for each frame and is not sequential. The top part of the left side shows how colors were assigned in sequence for each ball. The right side shows how the target images are created based on two different rules: ‘Earliest Color’ which picks the earliest color assigned to a ball during the context sequence, or ‘Most Frequent Color’ which takes the most frequent color during the context. The top part of the right side shows rules for both cases. The figure demonstrates how a sequence of images creates a long-range reasoning problem.

This figure shows example image sequences from the Blinking Color Balls benchmark dataset. Each example sequence has a context (a series of frames where a randomly selected ball changes to a non-white color in each frame) followed by a target frame. The target frame’s colors are determined by two rules: (a) Earliest Color, where each ball’s color is its first non-white color from the context, and (b) Most Frequent Color, where each ball’s color is the most frequent non-white color from the context. This dataset is designed to test the long-range reasoning capabilities of models, as they need to remember the color assignments throughout the sequence to predict the target frame.

This figure compares the qualitative results of different models on the Blinking Color Balls benchmark’s ‘Most Frequent Color’ variant, using a sequence length of 80 frames. It shows the context frames (input), the ground truth target image, and the predictions from SlotSSM, SlotTransformer, SlotRNN, Single State SSM, and RIM. The comparison highlights how well each model captures both the object movement and the color assignment rules. Specifically, it shows that SlotSSM and SlotTransformer successfully achieve both accurate position prediction and color assignment, while RIM fails to learn the color assignment rules, and the others achieve varying degrees of success.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the SlotSSM model for sequence modeling. Each layer consists of three components: a Slot Encoder, a SlotSSM, and a Slot Mixer. The Slot Encoder takes input sequences and extracts multiple independent slot representations using a Transformer network. The SlotSSM then independently updates the state of each slot based on its own previous state and input. Finally, the Slot Mixer allows for sparse interactions between the slots via self-attention, facilitating information exchange between the different object representations. This modular design enables efficient and scalable modeling of complex sequences with underlying modular structures.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the SlotSSM model for sequence modeling. It consists of three main components stacked in each layer: a Slot Encoder, a SlotSSM, and a Slot Mixer. The Slot Encoder uses a transformer to extract slot representations from the input. The SlotSSM then independently updates each slot using its own state transition functions. Finally, the Slot Mixer allows for sparse interactions between the slots using a self-attention mechanism, enabling communication and information exchange between them. This modular design of the SlotSSM helps to capture underlying modular structures within sequences.

This figure shows visualizations of the attention mechanisms in the decoders of SlotSSMs for three different tasks: multi-object video prediction, the Blinking Color Balls benchmark, and object-centric learning. The visualizations reveal that each slot tends to specialize in representing a specific object or a coherent part of the scene, demonstrating the emergence of object-centric representations in SlotSSMs. This emergent modularity highlights the model’s ability to efficiently capture object dynamics and interactions, leading to improved performance in complex tasks. Even without explicit spatial disentanglement constraints, SlotSSMs discover and exploit the underlying structure of the data.

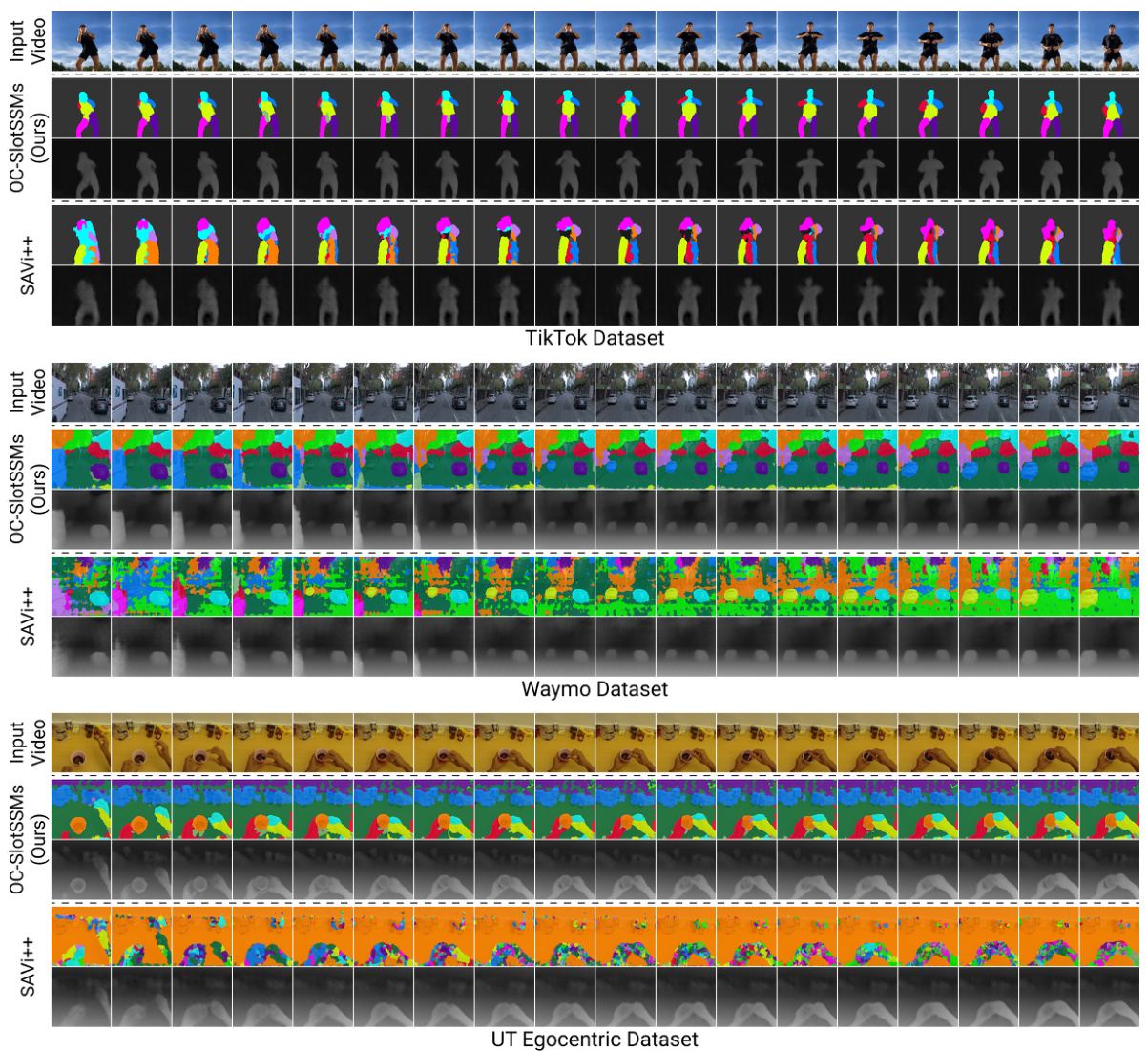

This figure shows the emergent scene decomposition from depth estimation tasks using OC-SlotSSMs and SAVi++. The color of each segment represents the ID of the slot used for predicting that position. This demonstrates the capability of SlotSSM to capture the modularity inherent in real-world videos, leading to more efficient inference without explicit segmentation supervision.

More on tables

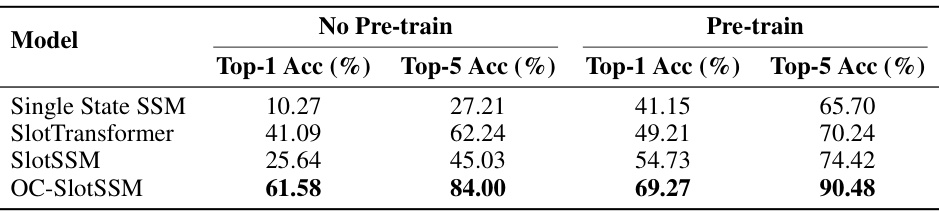

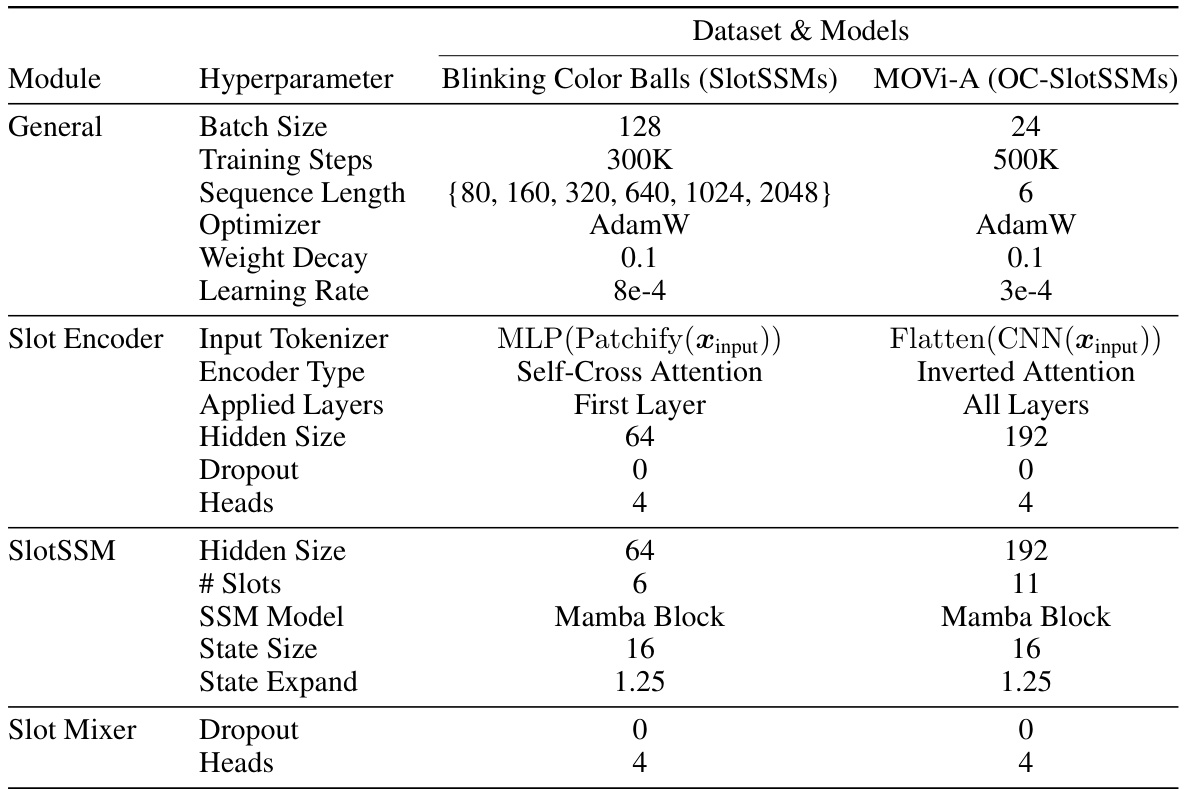

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the experiments for both the Blinking Color Balls dataset (using SlotSSMs) and the MOVi-A dataset (using OC-SlotSSMs). It details settings for general training parameters (batch size, training steps, sequence length, optimizer, weight decay, learning rate), Slot Encoder parameters (input tokenizer, encoder type, applied layers, hidden size, dropout, heads), SlotSSM parameters (hidden size, number of slots, SSM model, state size, state expansion factor), and Slot Mixer parameters (dropout and heads).

This table presents the architecture of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) encoder used in the object-centric learning experiments. It details the specifications for each convolutional layer, including kernel size, stride, padding, number of channels, and activation function. This encoder processes image inputs to extract features before they are fed into the rest of the object-centric model.

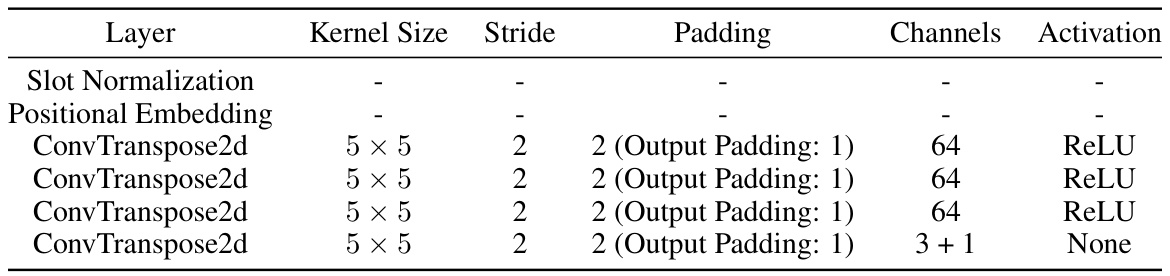

This table details the architecture of the spatial broadcast decoder used in the object-centric learning experiments. It shows the layers, kernel size, stride, padding, number of channels, and activation function used in each layer of the decoder. The decoder takes slot representations as input and generates object images and alpha masks, which are combined to create the final reconstructed image.

This table shows the mean squared error (MSE) for depth estimation on three different datasets: UT Egocentric, Waymo, and TikTok. The lower the MSE, the better the performance. Two models are compared: SAVi++ and OC-SlotSSM (Ours). The results indicate that OC-SlotSSM achieves lower MSE than SAVi++ on all datasets, demonstrating its effectiveness in depth estimation.

Full paper#