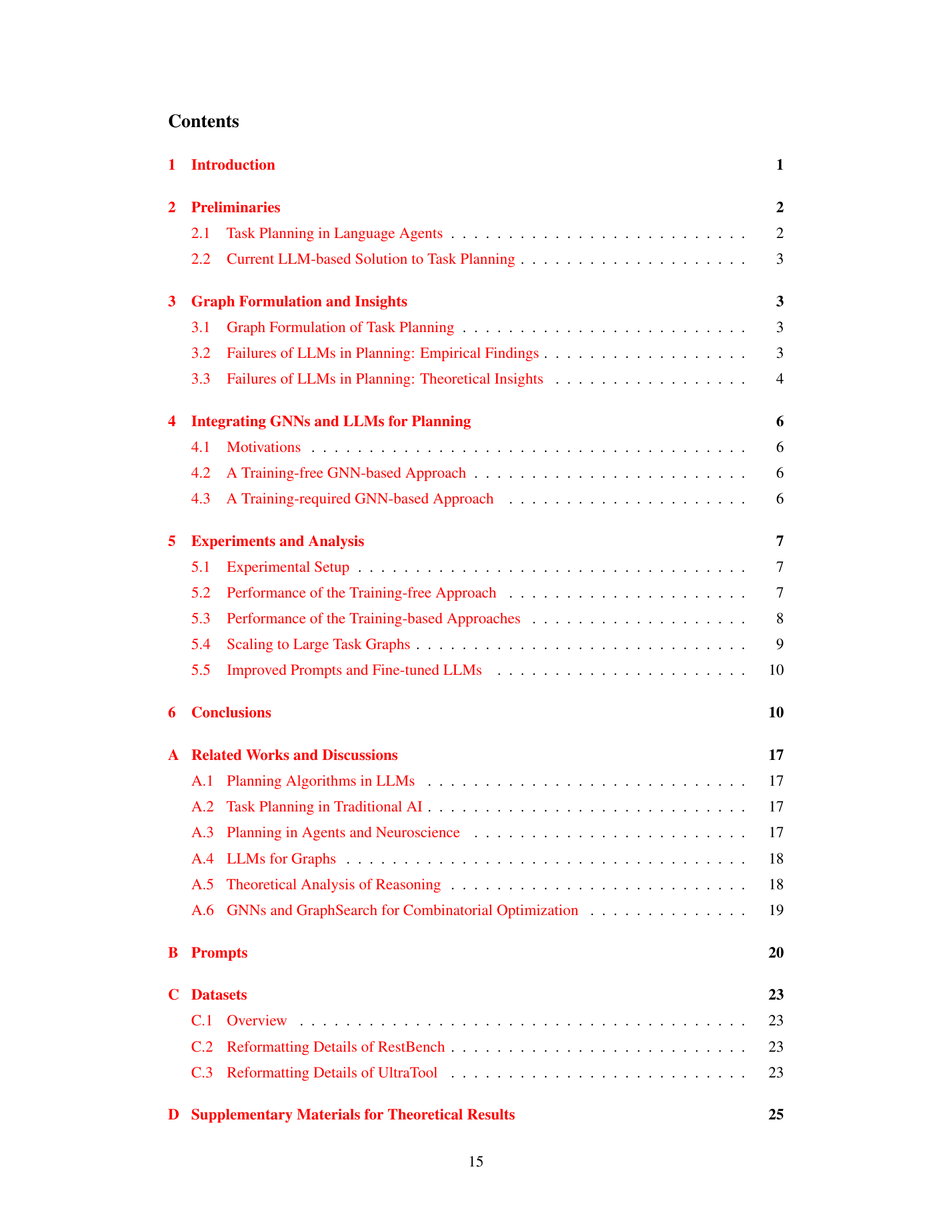

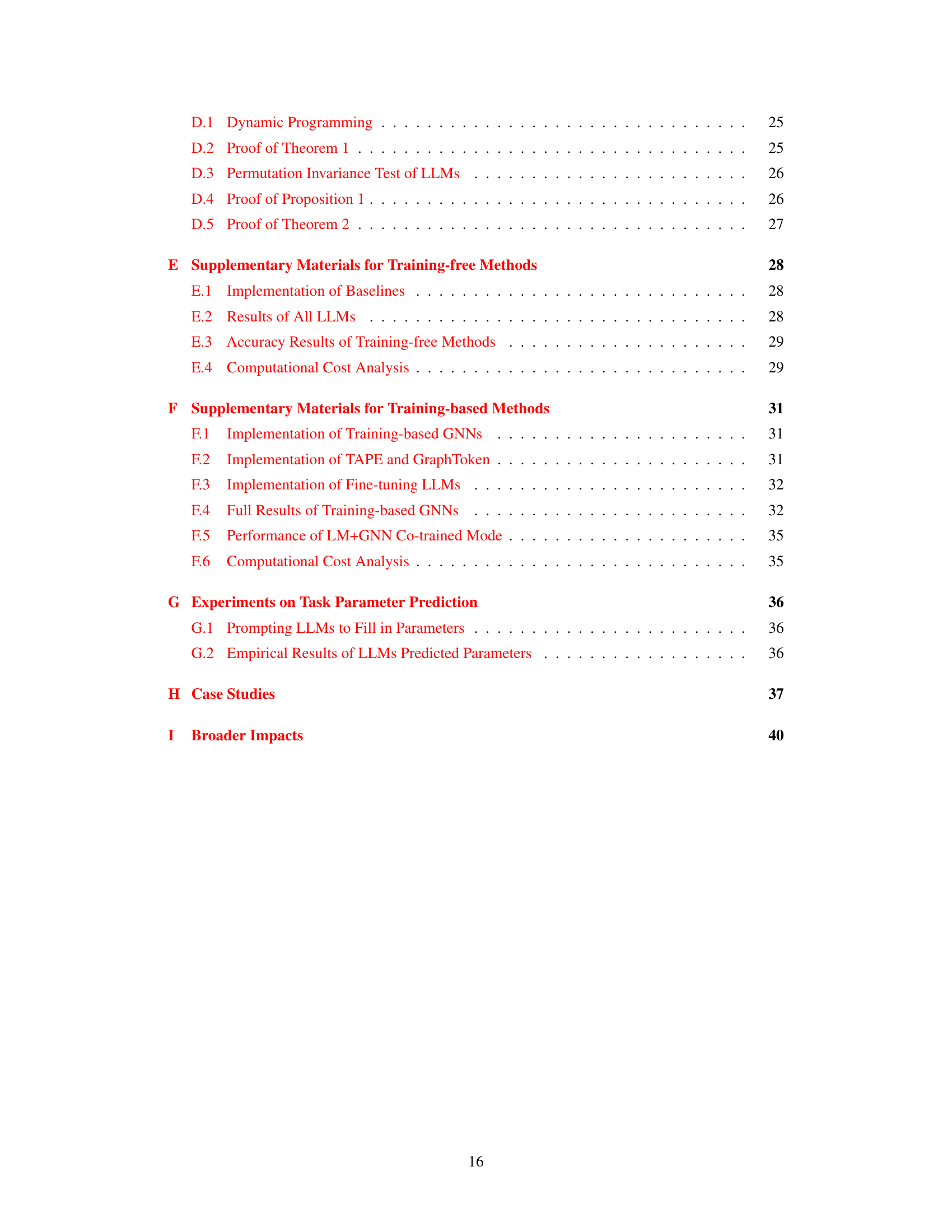

↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

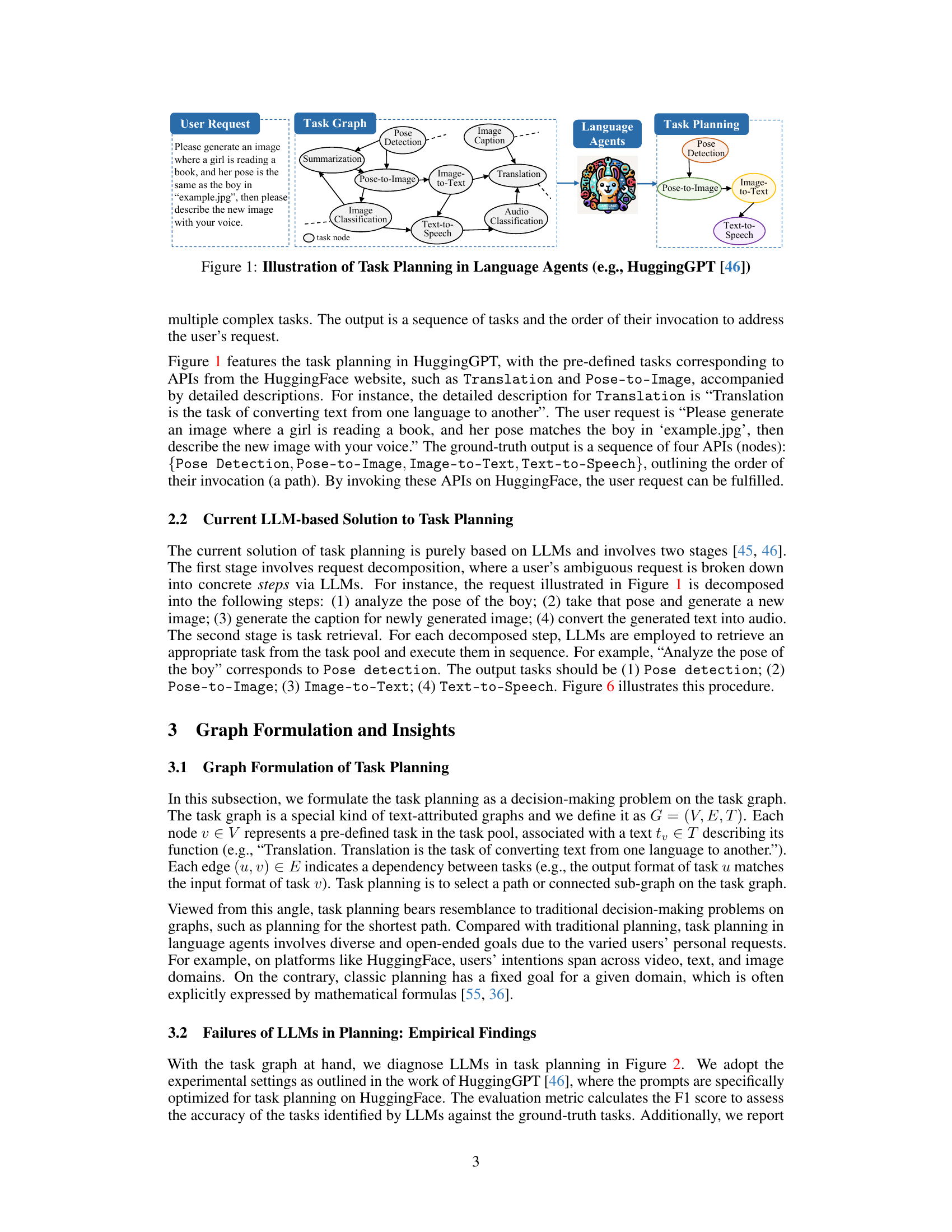

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly used in task planning for AI agents, breaking down complex requests into smaller sub-tasks. However, LLMs often struggle to accurately represent these sub-tasks and their dependencies as graphs, leading to planning failures. This paper investigates this issue and reveals that attention bias and auto-regressive loss hinder LLMs’ graph reasoning capabilities.

To address this problem, the researchers propose a novel approach that integrates graph neural networks (GNNs) with LLMs. GNNs are well-suited for processing graph structures, enabling more accurate task planning. Experiments demonstrate that GNN-based methods significantly outperform existing LLM-only approaches, especially when dealing with larger task graphs. The performance gains show the effectiveness of integrating GNNs and LLMs, opening up new avenues for improving task planning in AI agents.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on LLM-based agents and task planning. It addresses a critical limitation of LLMs in handling complex tasks by proposing a novel approach that uses graph neural networks (GNNs) to improve planning efficiency and accuracy. The findings challenge existing assumptions about LLM capabilities and offer new avenues for research in integrating LLMs with other AI techniques.

Visual Insights#

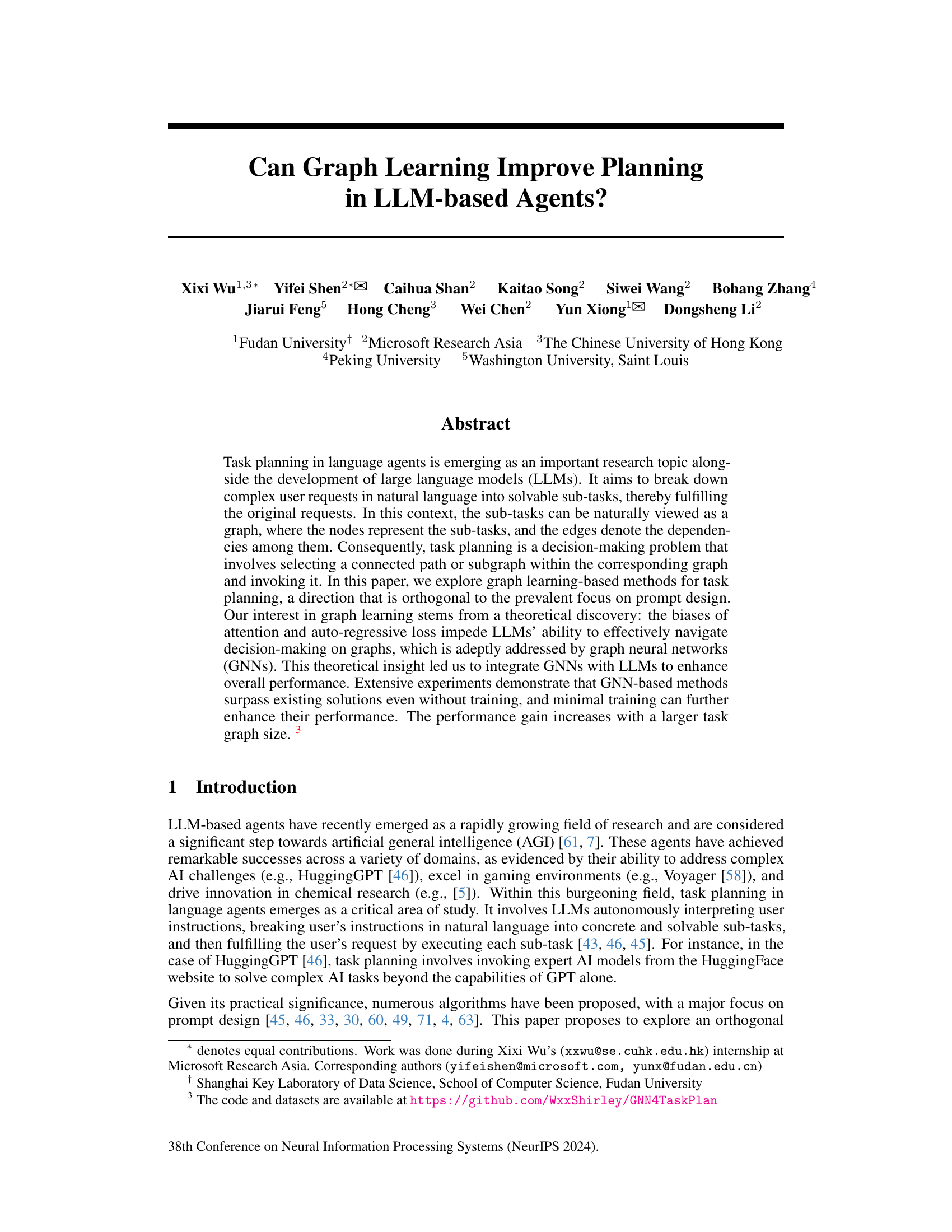

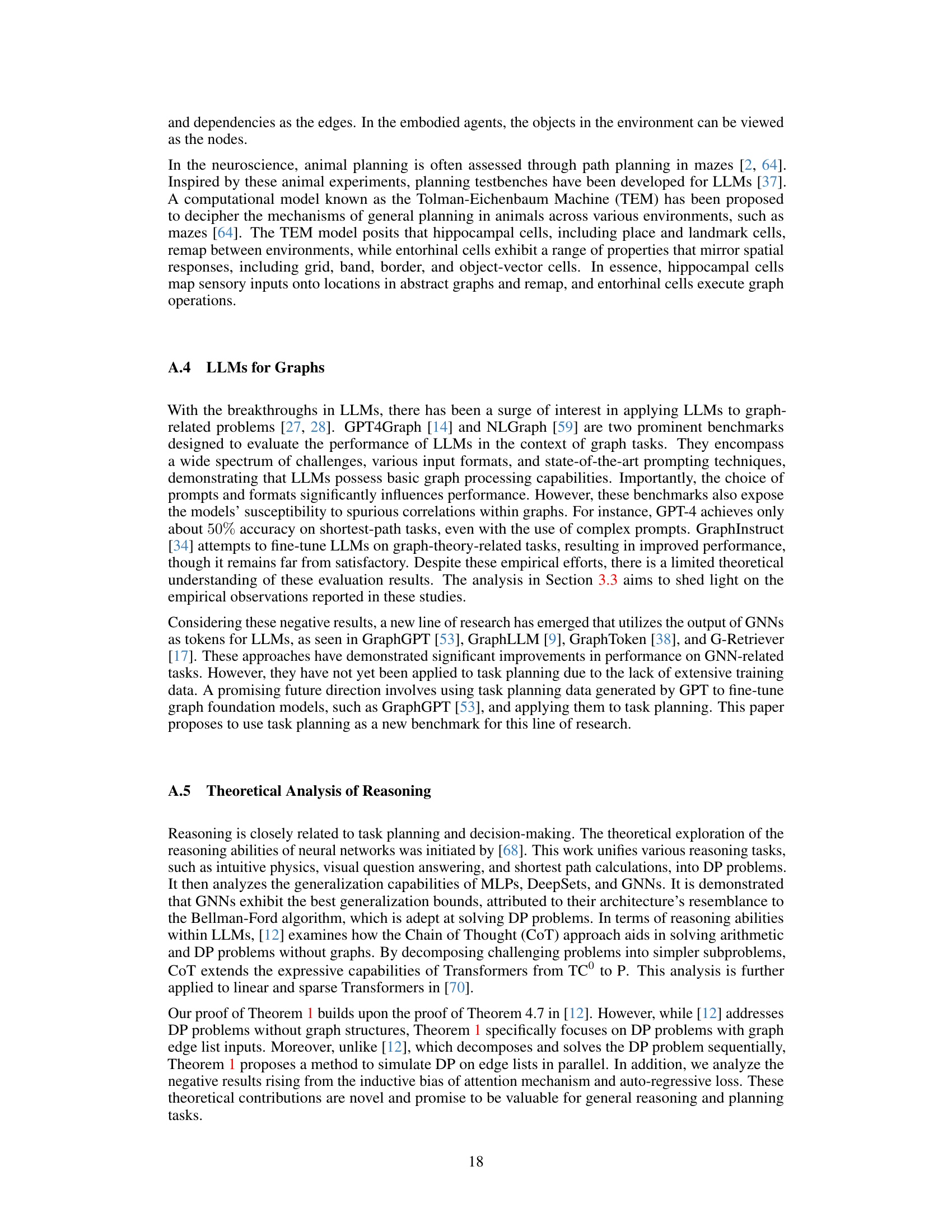

This figure illustrates the task planning process in language agents, using HuggingGPT as an example. A user request (e.g., ‘Please generate an image where a girl is reading a book, and her pose is the same as the boy in ’example.jpg’, then please describe the new image with your voice.’) is decomposed into a sequence of sub-tasks represented as a task graph. Each node in the graph represents a sub-task (e.g., Pose Detection, Pose-to-Image, Image-to-Text, Text-to-Speech), and the edges denote the dependencies between them. The task planning process involves selecting a path through the graph (a sequence of sub-tasks) that fulfills the user’s request. The selected path is then executed by invoking the corresponding APIs (from HuggingFace, in this case) to achieve the final result. This showcases the graph-based nature of task planning, a key concept explored in the paper.

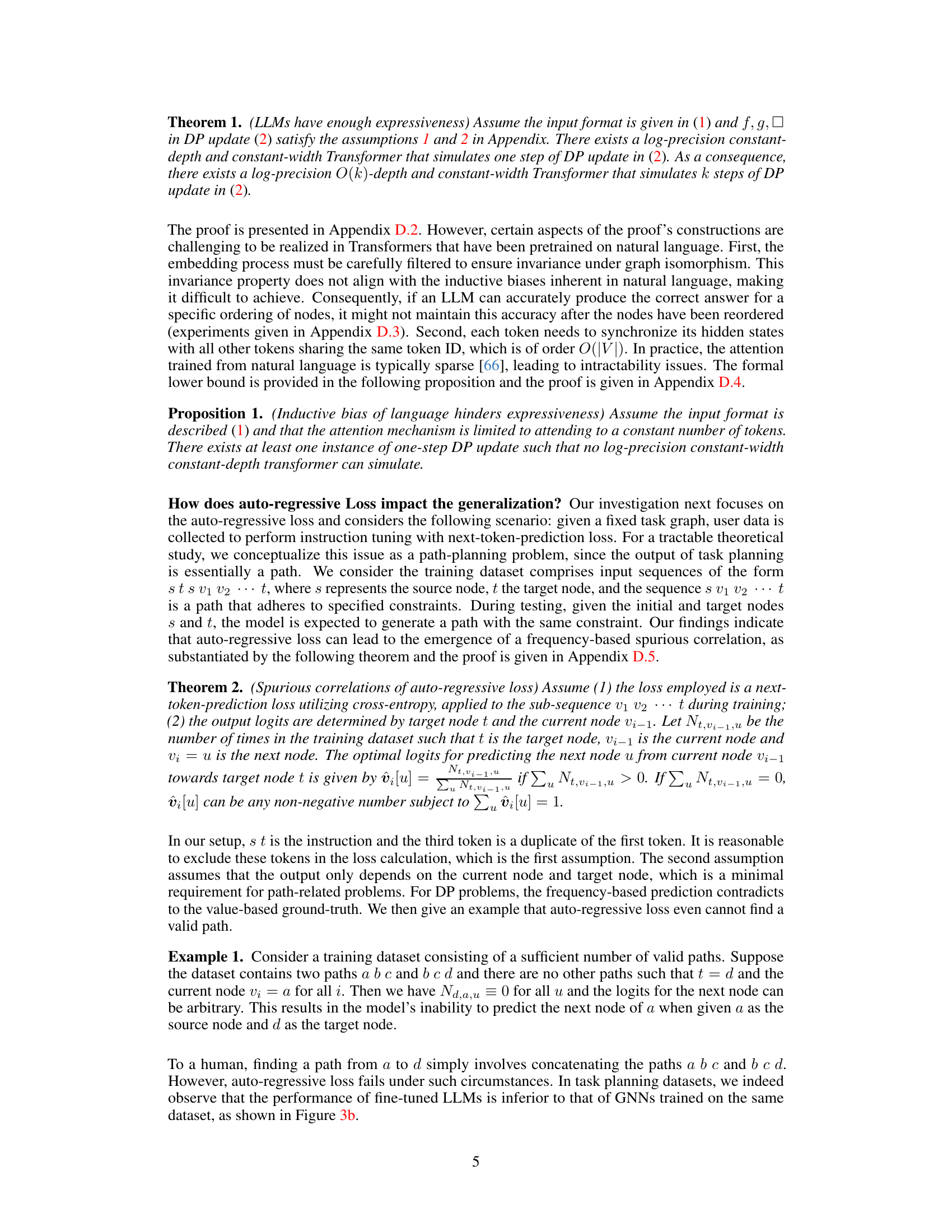

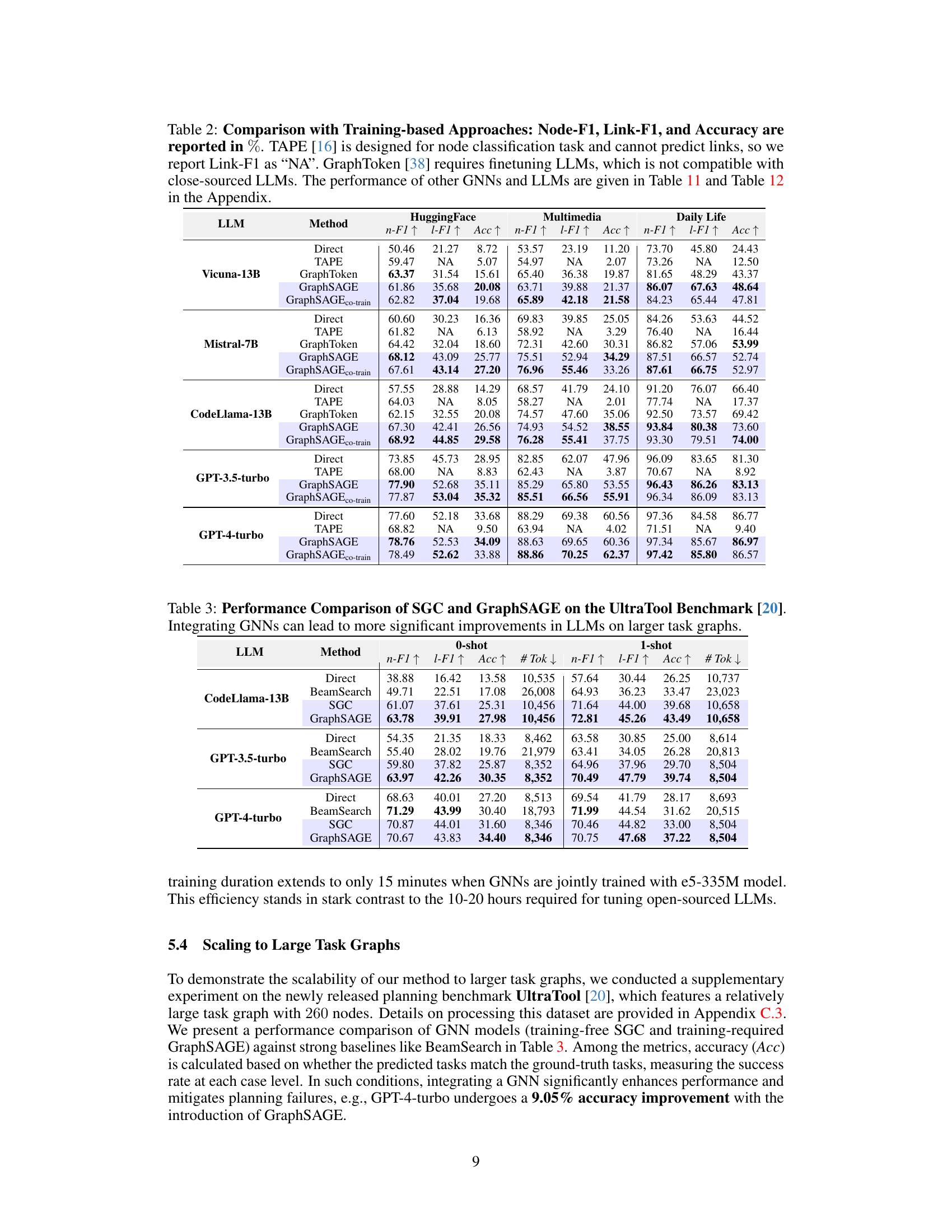

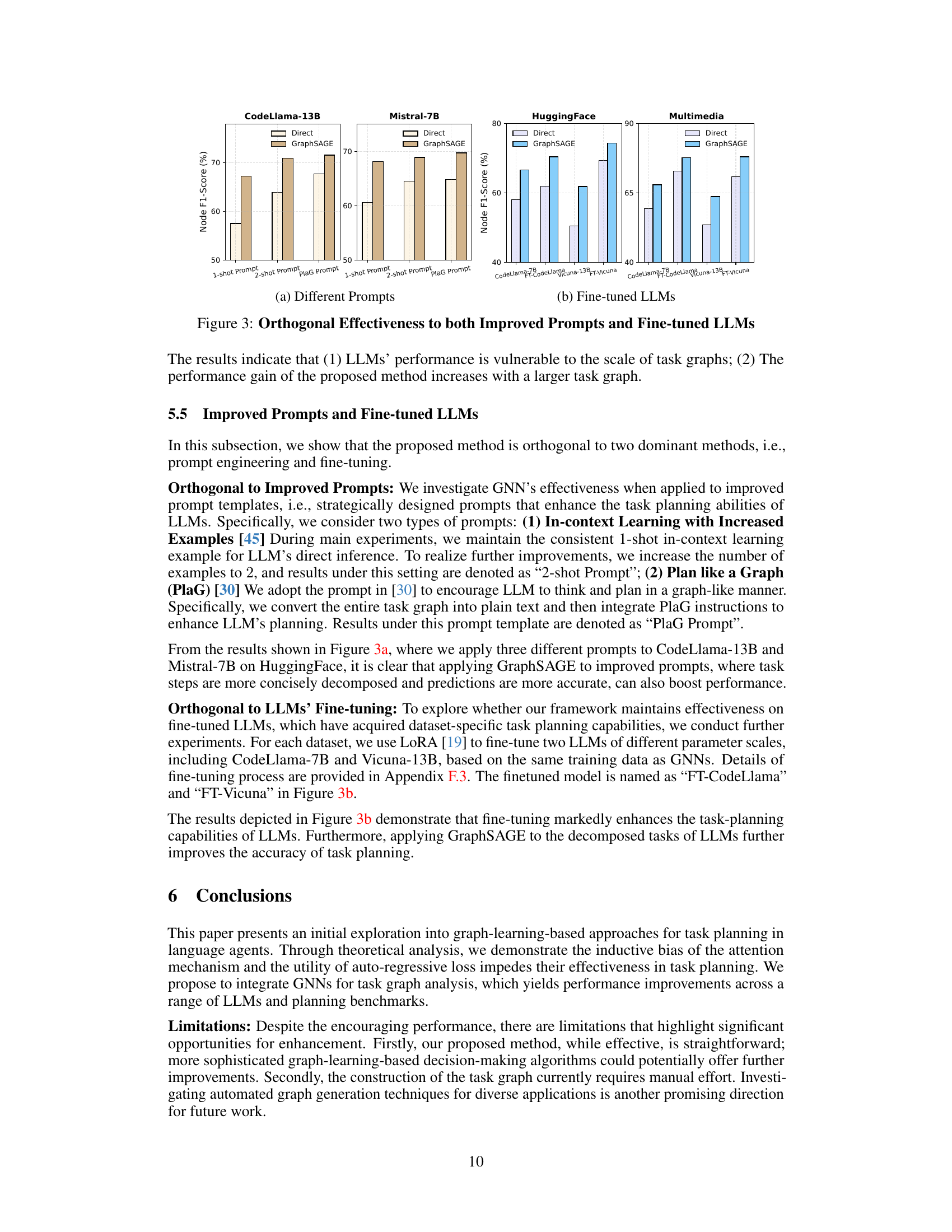

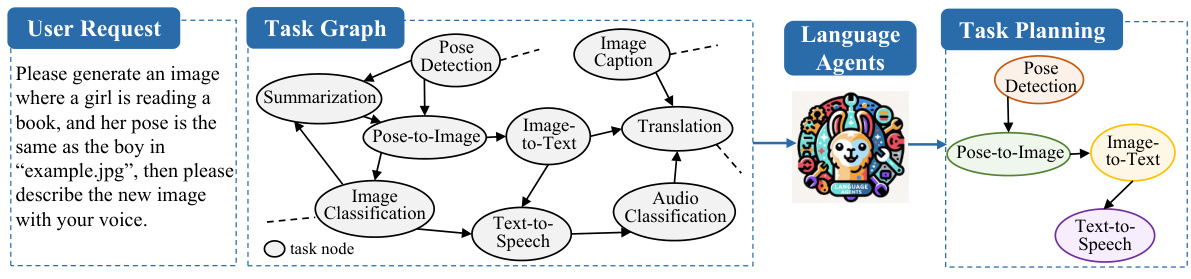

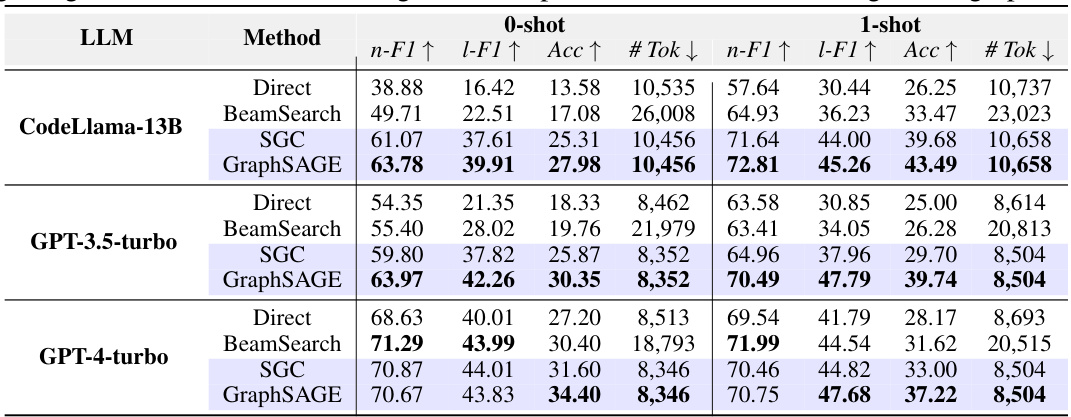

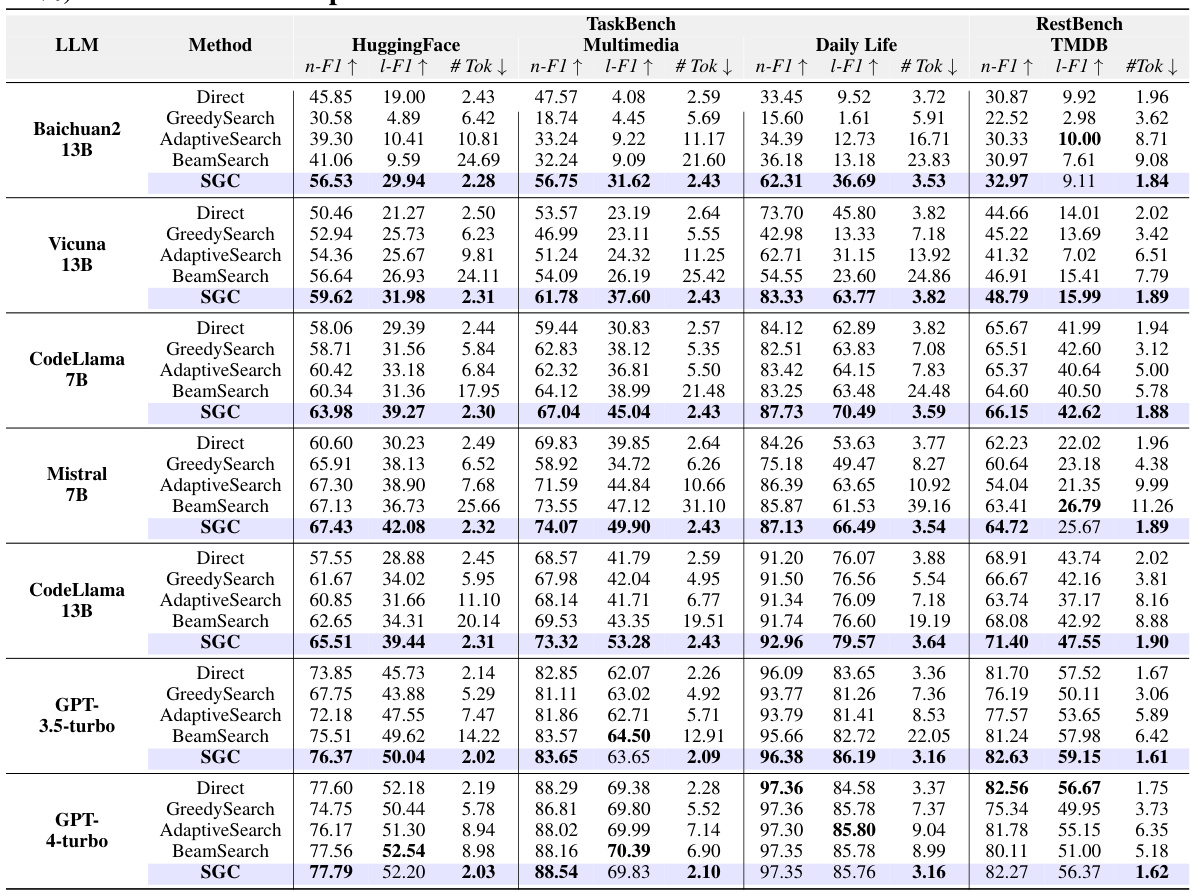

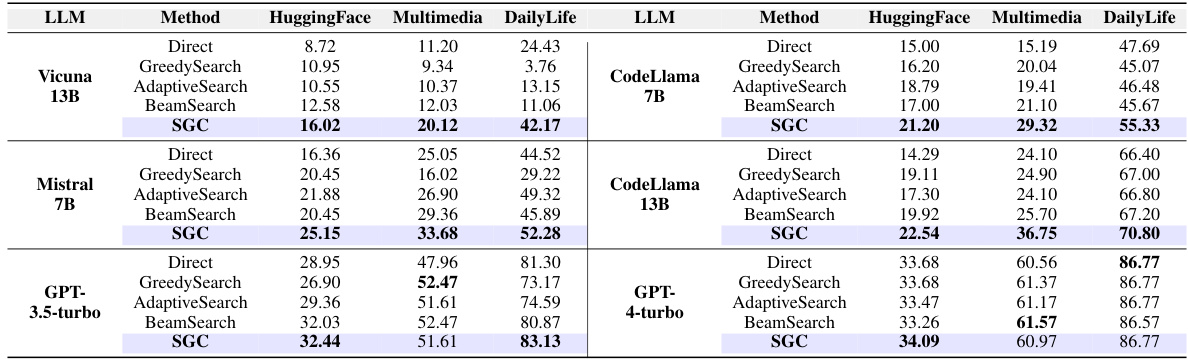

This table compares the performance of four different training-free methods for task planning across five different datasets using various LLMs. The methods compared are LLM’s Direct Inference, Greedy Search, Adaptive Search, Beam Search, and the proposed SGC method. The performance metrics used are Node F1-score and Link F1-score, which measure the accuracy of the tasks and their dependencies, respectively. Token consumption is also presented as a measure of efficiency. The table shows how the proposed SGC method generally outperforms the other baselines in terms of accuracy while using significantly fewer tokens.

In-depth insights#

LLM Planning Limits#

LLM-based task planning, while showing promise, faces significant limitations. LLMs struggle to accurately represent the inherent graph structure of tasks and their dependencies, often hallucinating or misinterpreting relationships. This stems from the mismatch between the sequential processing of LLMs and the inherent parallelism of graph-based problem-solving. The autoregressive nature of LLM training further exacerbates these issues, creating spurious correlations between task elements. Consequently, LLMs lack invariance to graph isomorphism, meaning their performance may be heavily impacted by simple changes in task presentation. These limitations suggest the need for integrating alternative methods, such as graph neural networks (GNNs), to enhance LLM-based planning systems and compensate for these weaknesses.

GNN-LLM Synergy#

The concept of ‘GNN-LLM Synergy’ in a research paper would explore the combined strengths of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Large Language Models (LLMs) for enhanced performance in complex tasks. GNNs excel at processing relational data, offering a structural understanding crucial for tasks with inherent dependencies, like task planning. LLMs, on the other hand, are adept at handling natural language, enabling seamless interaction with human users and flexible task definition. By combining these strengths, a synergistic approach can be developed where GNNs provide the structural backbone for problem representation, while LLMs facilitate nuanced understanding of user requests and generate natural language outputs. This integration is particularly beneficial for tasks requiring both relational reasoning (GNN strength) and complex language understanding (LLM strength). A successful ‘GNN-LLM Synergy’ system would demonstrate superior performance over LLMs or GNNs alone, showcasing the potential of this combined architecture for a wide range of applications, specifically in areas like complex reasoning, multi-step planning, and knowledge graph management. The paper would likely discuss challenges like efficient integration and data compatibility, as well as potential biases introduced by either GNN or LLM components.

Graph Learning#

Graph learning, in the context of LLMs for task planning, offers a powerful paradigm shift from traditional sequential processing. The inherent limitations of LLMs in effectively navigating complex task dependencies, visualized as graphs, are addressed by leveraging the strengths of GNNs. This involves representing sub-tasks as nodes and dependencies as edges, enabling GNNs to reason over the graph structure. A key advantage is the potential for zero-shot performance, bypassing the need for extensive training in dynamic environments. While LLMs excel at natural language understanding and task decomposition, GNNs provide a more effective mechanism for navigating the decision-making process inherent in task planning. The combination of LLMs and GNNs offers a synergistic approach, with LLMs handling high-level reasoning and GNNs optimizing sub-task selection and execution, ultimately improving overall efficiency and accuracy.

Training-Free Methods#

The concept of ‘Training-Free Methods’ in the context of a research paper likely centers on techniques or algorithms that achieve a specific task without requiring a traditional training phase using labeled datasets. This is particularly valuable when labeled data is scarce, expensive, or when the task’s parameters might be dynamic. Such methods often leverage pre-trained models or parameter-free architectures that rely on inherent inductive biases or clever mathematical formulations to achieve good performance. A key strength of training-free approaches is their immediate applicability and adaptability to new or changing environments without the need for retraining. However, it is crucial to note that the performance of training-free methods may not match the performance achievable with trained models in data-rich settings and could be less adaptable to complex scenarios. The analysis of training-free methods will likely investigate their limitations and compare their performance against those that require training, revealing valuable insights into the trade-offs involved.

Future Work#

Future research could explore several promising directions. Extending the framework to handle more complex tasks with intricate dependencies is crucial for real-world applications. Investigating more advanced graph neural network architectures may improve efficiency and accuracy. Developing techniques for automated graph generation would significantly reduce manual effort. A detailed theoretical analysis of the interplay between LLMs and GNNs is needed to guide future model design. Finally, evaluating the proposed methods on diverse datasets and benchmarking against a wider range of baselines would further solidify the findings and enhance the impact of the research. Further research could also focus on developing more robust methods for handling ambiguous user requests and improving the explainability of the model’s decisions. The integration of other AI techniques such as reinforcement learning could further enhance the capabilities of the system. The development of user-friendly interfaces for deploying and interacting with LLM-based agents is important for practical usability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

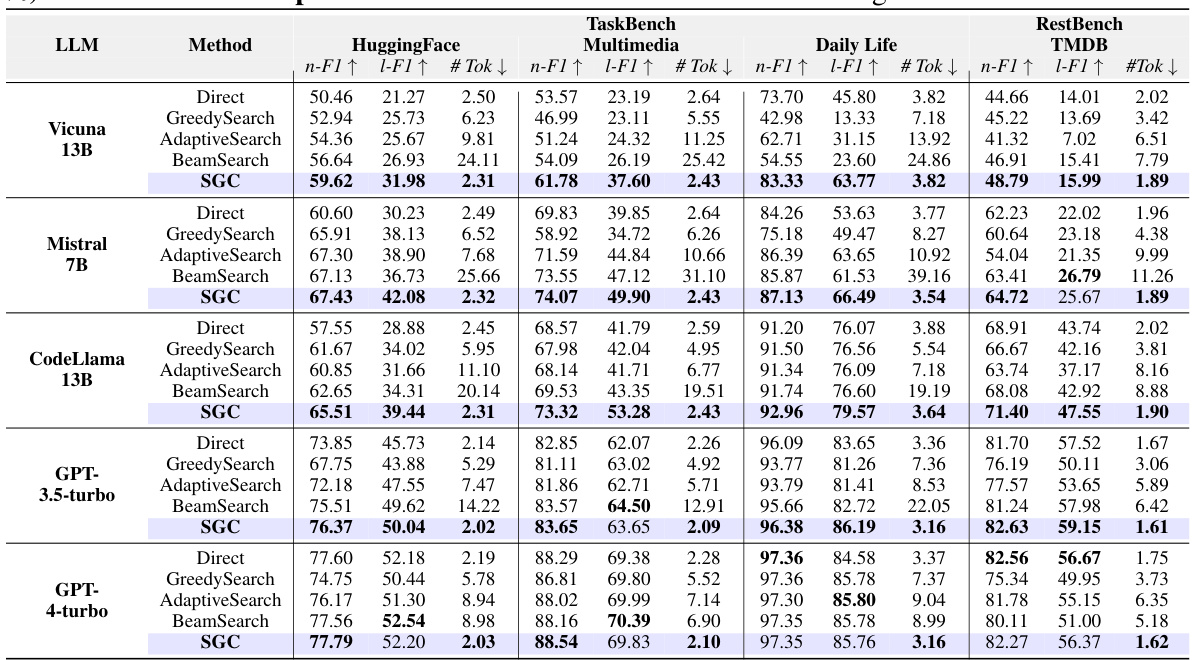

This figure shows the performance and hallucination rate of different LLMs on task planning. Panel (a) compares the performance (Task F1 score) and hallucination (node and edge hallucination ratios) across several LLMs on the HuggingFace task planning benchmark. Panel (b) shows the relationship between the hallucination rates and the size of the task graph (number of subtasks) across multiple datasets, highlighting a correlation between larger graphs and increased hallucinations.

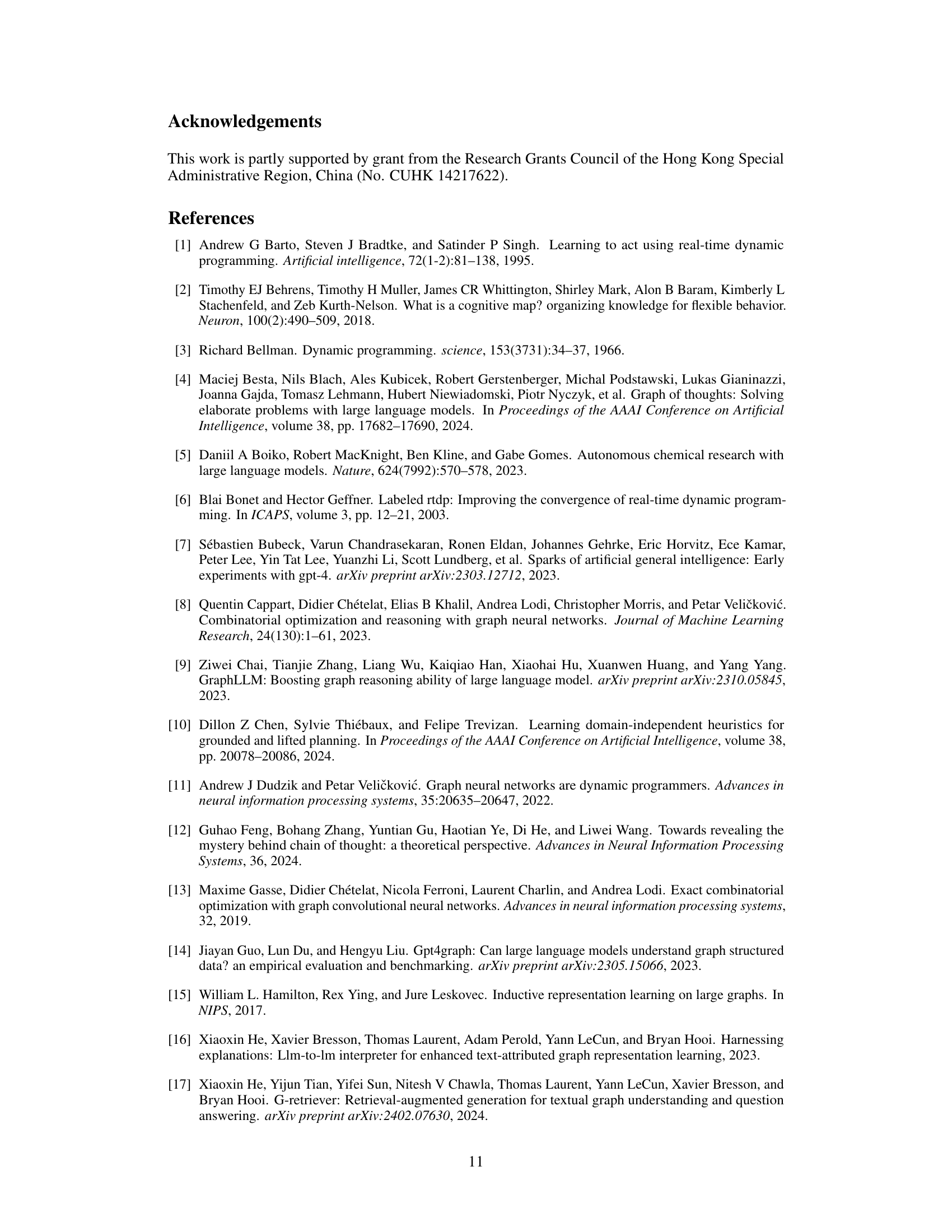

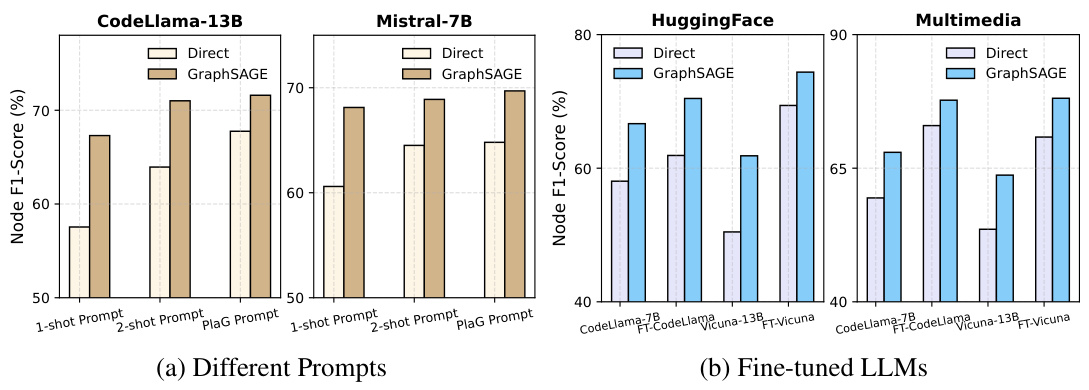

This figure demonstrates the orthogonal improvements achieved by integrating GNNs with LLMs for task planning. Panel (a) shows the impact of different prompt engineering techniques on the performance of LLMs (CodeLlama-13B and Mistral-7B) across three different datasets (HuggingFace, Multimedia, and Daily Life). The results indicate consistent gains from using GraphSAGE regardless of the prompt style. Panel (b) compares the performance of LLMs (CodeLlama-7B and Vicuna-13B) before and after fine-tuning, illustrating again the consistent benefits of using GraphSAGE. In summary, the results show that improvements from GraphSAGE are consistently observed, even under different prompt styles or after fine-tuning LLMs.

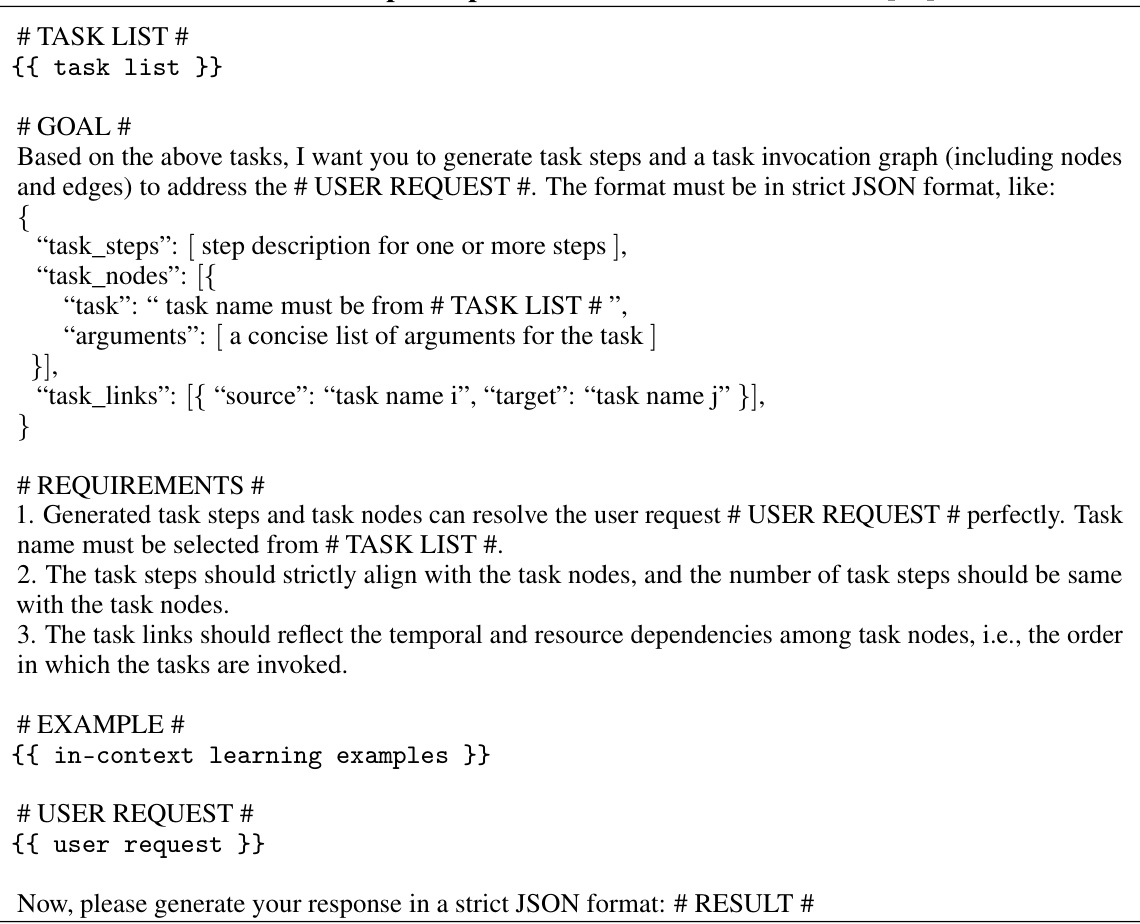

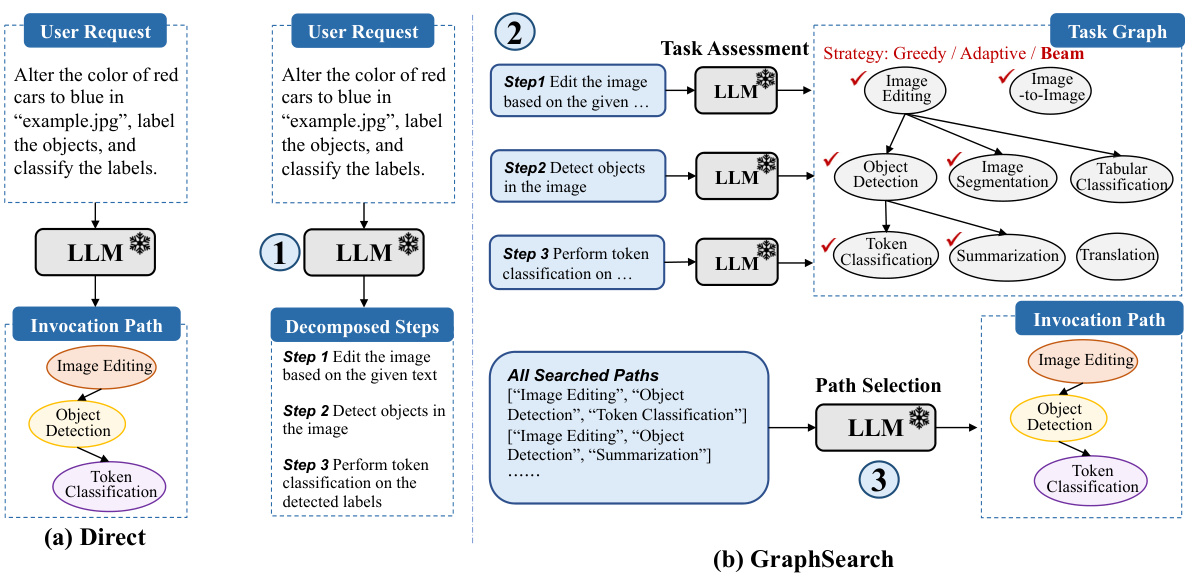

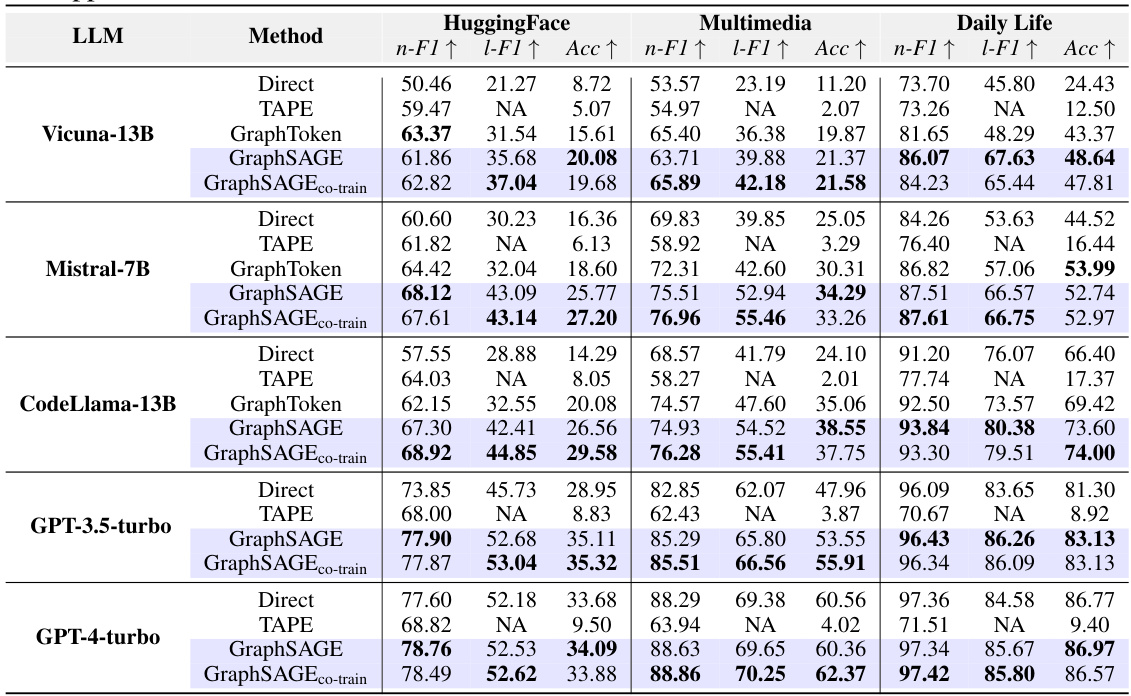

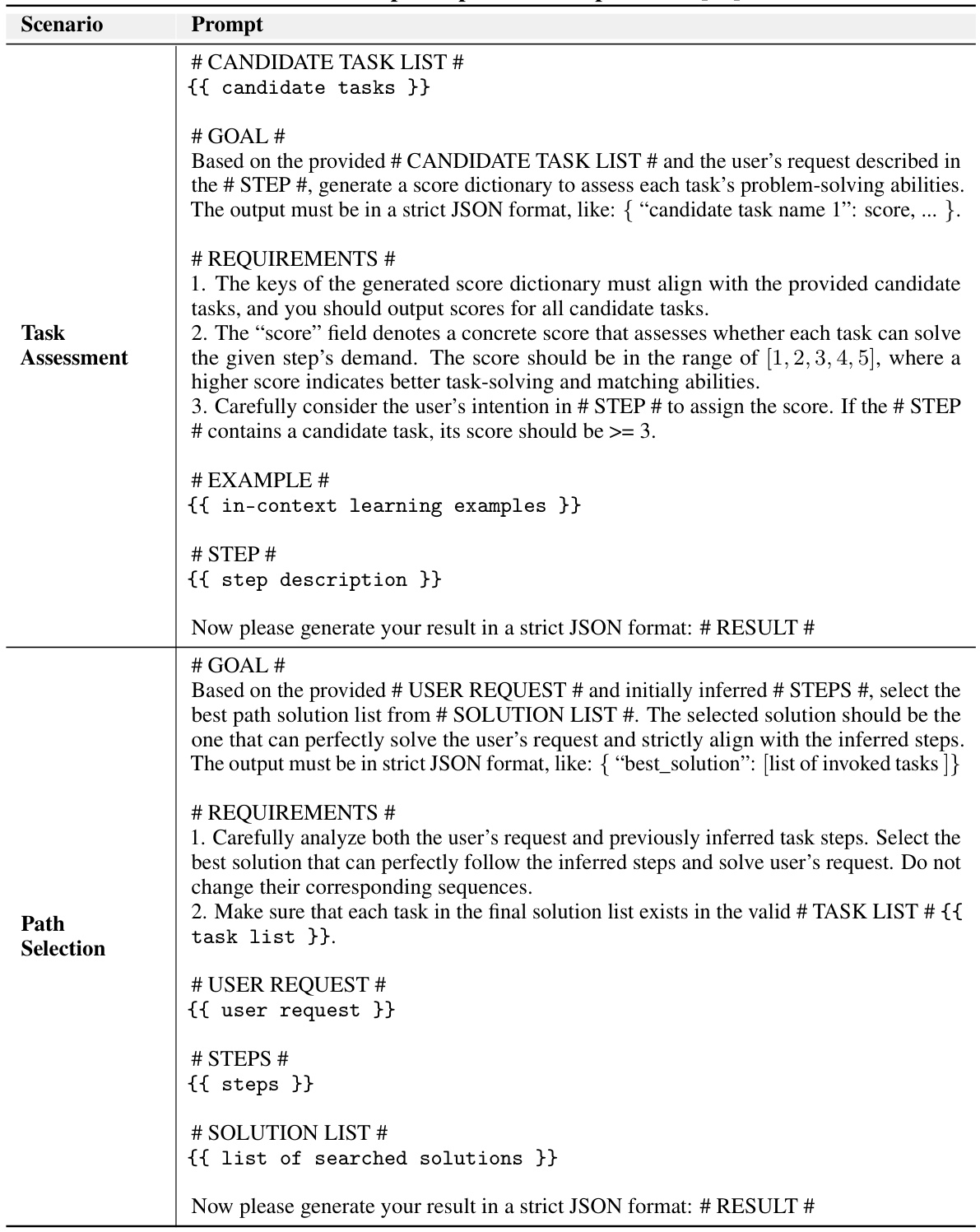

This figure illustrates the two baselines used in the paper for comparison: LLM’s Direct Inference and GraphSearch. LLM’s Direct Inference uses an LLM to directly generate the task invocation path. GraphSearch employs a greedy search algorithm on the task graph and leverages LLMs to score each candidate task’s suitability for the current step. The figure visually represents the process flow, highlighting the differences in their approaches.

This figure illustrates the two training-free baselines used in the paper for comparison against the proposed method. (a) shows the ‘Direct Inference’ method, where an LLM directly infers the task invocation path from the user request. (b) shows the ‘GraphSearch’ method, which leverages a graph search algorithm guided by an LLM to explore and select the optimal task invocation path from the task graph. The figure highlights the steps involved in each method, including task decomposition, task assessment (for GraphSearch), and path selection.

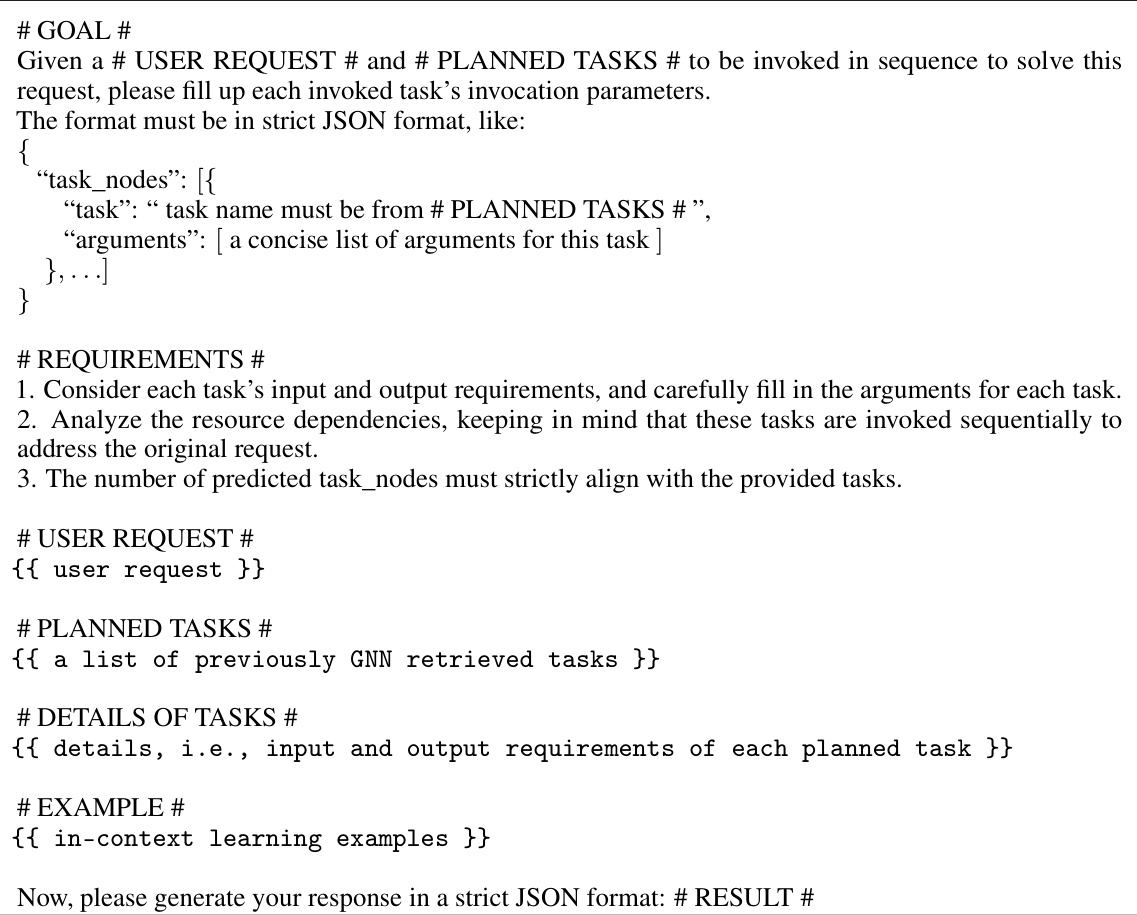

This figure shows example user requests, corresponding decomposed steps, and task invocation paths from four different datasets used in the paper: HuggingFace, Multimedia, Daily Life, and TMDB. Each example illustrates how a complex user request is broken down into smaller, manageable sub-tasks, highlighting the dependencies between them. The figure provides concrete examples of the types of tasks and their relationships that are used to evaluate the task planning performance of different LLMs and GNN-based methods.

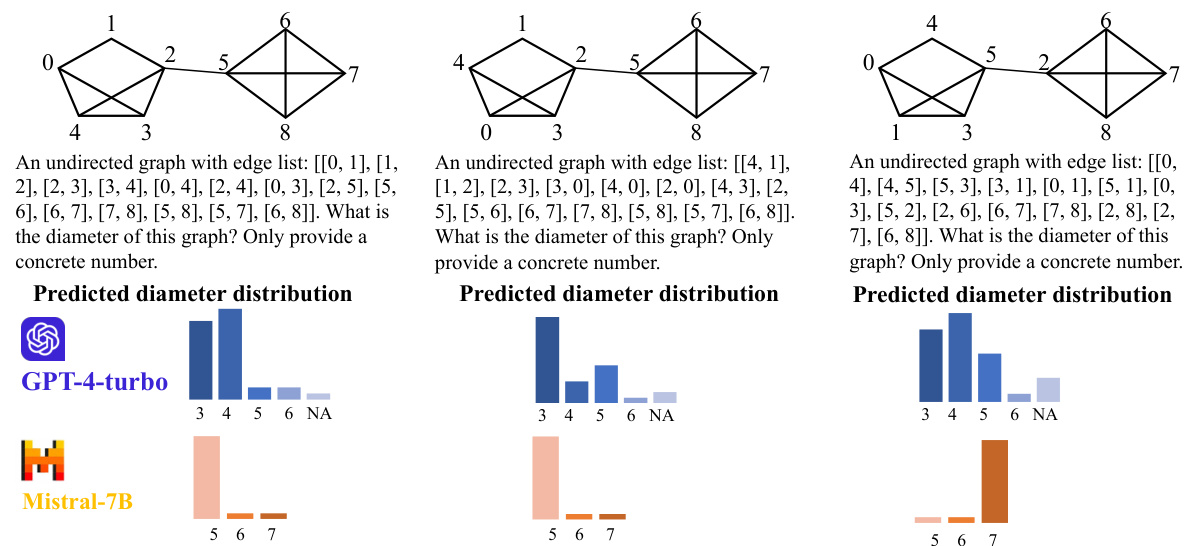

This figure shows three examples where different node orderings of the same graph lead to different diameter predictions by LLMs. This demonstrates the lack of permutation invariance in LLMs, a significant limitation when dealing with graph-structured data. The experiments were repeated 30 times to highlight the consistency of this issue.

This figure illustrates the two baselines used in the paper for comparison: LLM’s Direct Inference and GraphSearch. LLM’s Direct Inference uses the LLM directly to predict the task sequence from the user request. GraphSearch uses an iterative search algorithm on the task graph, where at each iteration, the LLM scores the suitability of neighboring tasks to proceed in the search. Both methods highlight the challenge of accurately discerning task dependencies and relations when solely relying on LLMs.

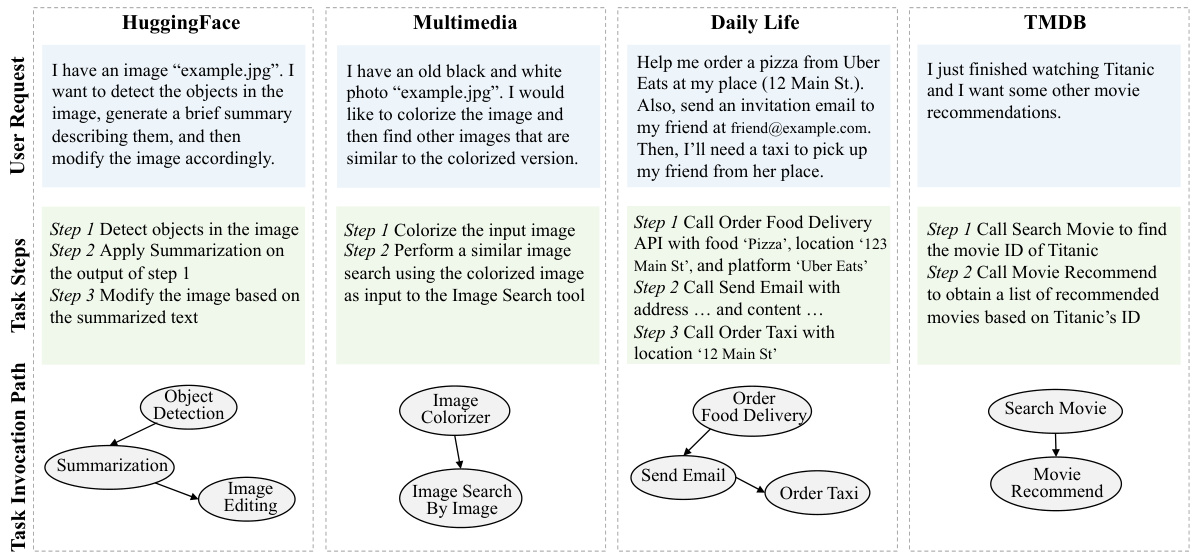

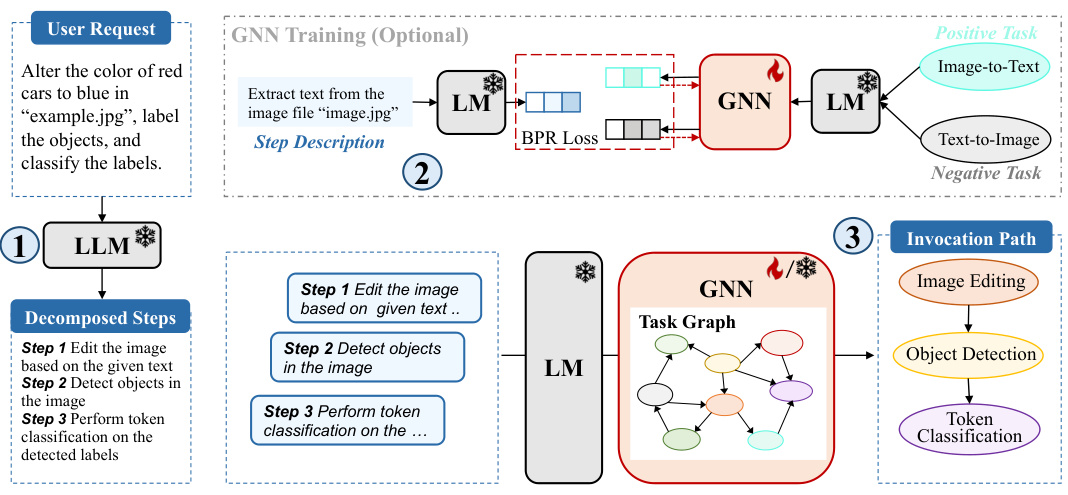

This figure illustrates the proposed GNN-enhanced task planning framework. It shows a two-stage process: 1) LLMs decompose the user request into a sequence of manageable steps and 2) GNNs select the appropriate tasks from a task graph to fulfill each step, thereby generating the final task invocation path. The optional GNN training uses a Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) loss to learn from implicit sub-task rankings. This framework combines the strengths of LLMs for natural language understanding and GNNs for graph-based decision-making.

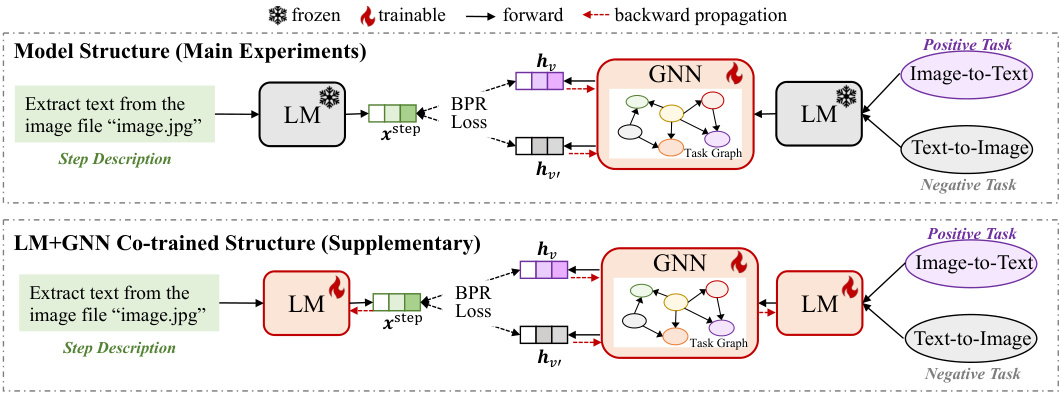

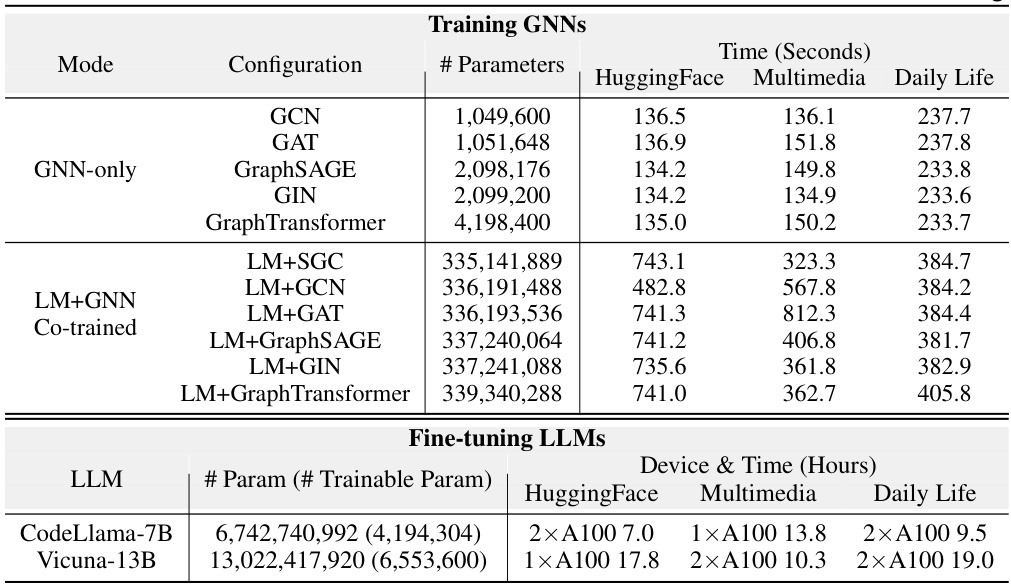

This figure illustrates the two different model configurations used in the training-based approach. The top configuration shows the model architecture where only the Graph Neural Network (GNN) is trained, while the Language Model (LM) is frozen (weights are not updated during training). The bottom configuration shows a co-training setup, where both the GNN and LM are trained simultaneously using the Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) loss function. Both models use a similar pipeline for inference: the LM extracts text from an image, which serves as input to the GNN. The GNN then interacts with the task graph to select a task, and the LM is used again to process the output of the GNN. The difference is that in the second approach, the LM is also fine-tuned alongside the GNN.

This figure illustrates the difference between LLM’s Direct Inference and GraphSearch methods for task planning. LLM’s Direct Inference uses LLMs to directly generate task invocation paths from user requests. In contrast, GraphSearch employs an iterative search strategy that evaluates the suitability of potential task sequences using LLMs before selecting an optimal path. The figure shows a detailed breakdown of each step involved in both methods, including prompt engineering, task assessment, path selection and final path generation.

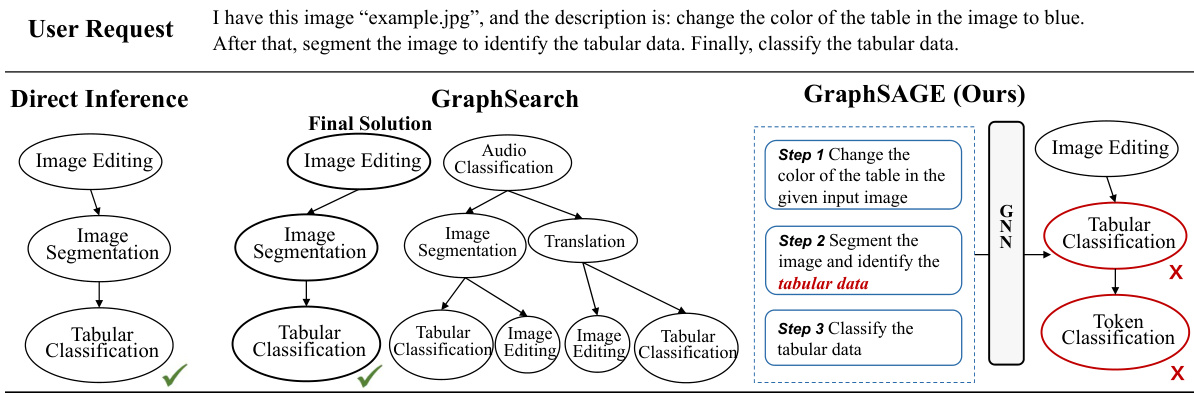

The figure shows a case where the GNN framework fails due to ambiguous step descriptions in the task decomposition phase. An ambiguous step leads the GNN to choose an incorrect task, which then propagates to subsequent steps in the sequential task selection process. This illustrates a limitation of the approach where the accuracy of the GNN depends on the clarity of the input descriptions.

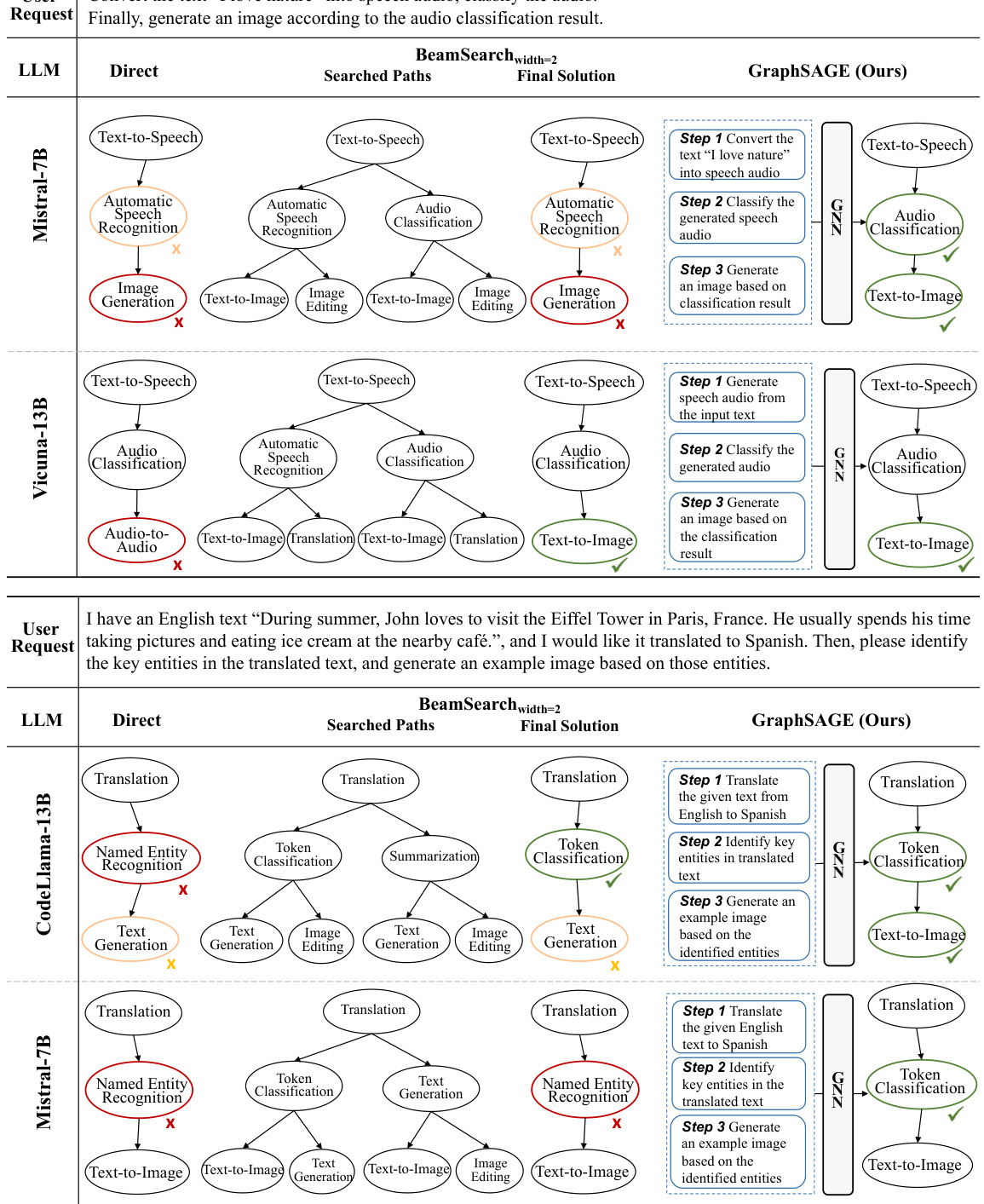

This figure demonstrates two examples to compare the performance of LLMs’ direct inference, BeamSearch, and GraphSAGE. The results show that although LLMs can explore ground-truth paths, they often fail to select the optimal paths due to limited instruction-following and reasoning abilities. In contrast, GraphSAGE consistently selects the correct tasks and achieves the ground-truth results, highlighting its effectiveness in task planning.

More on tables

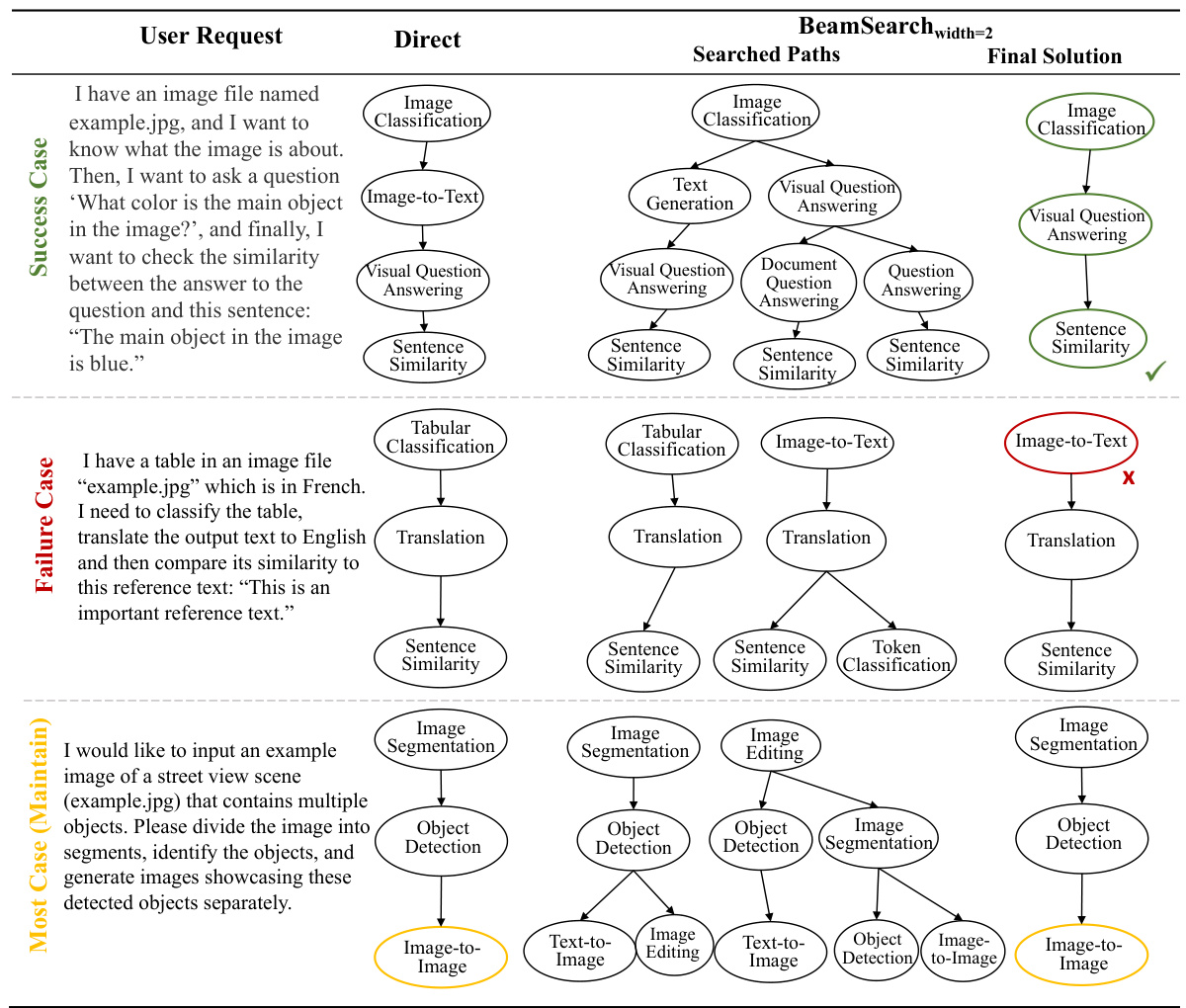

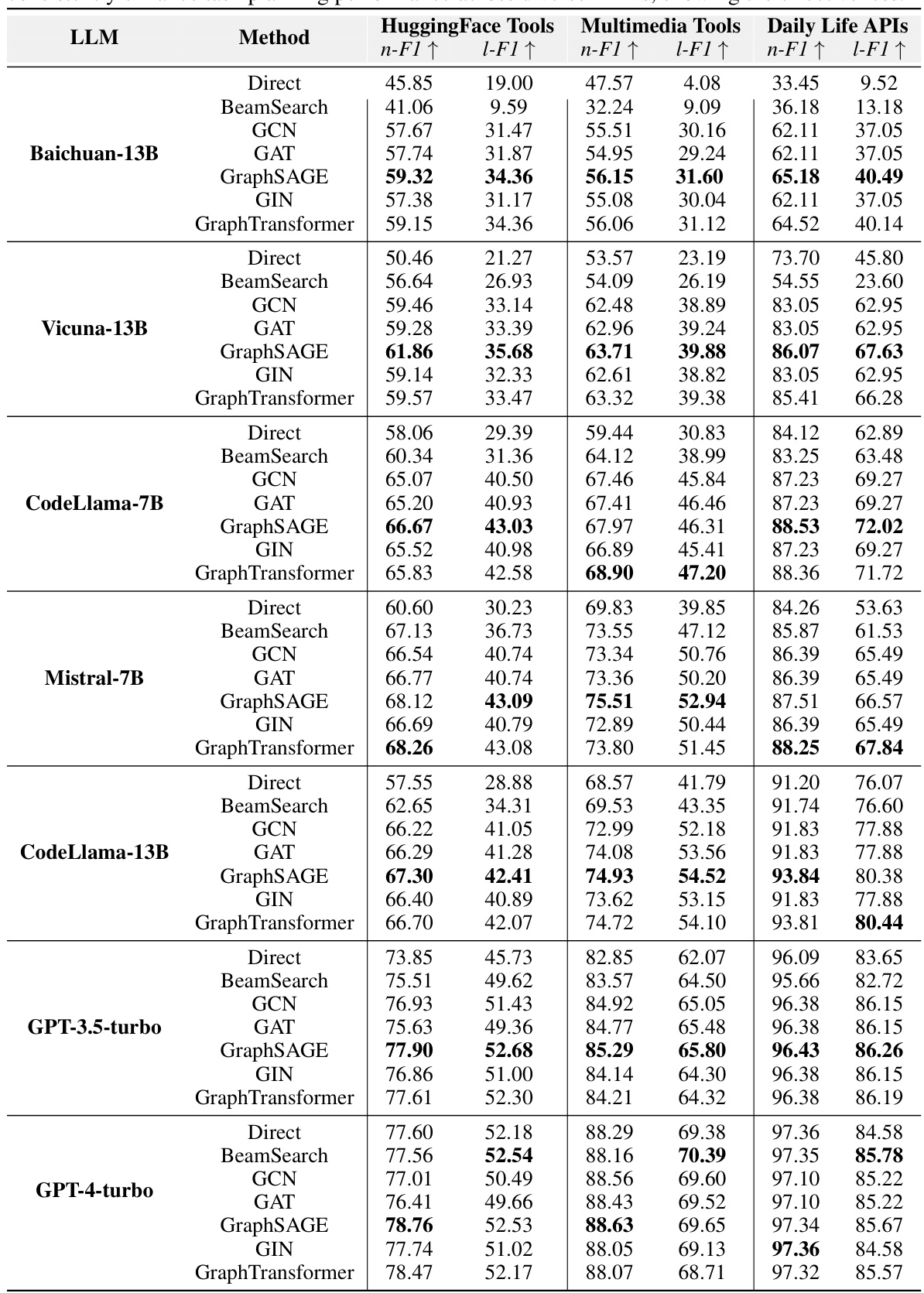

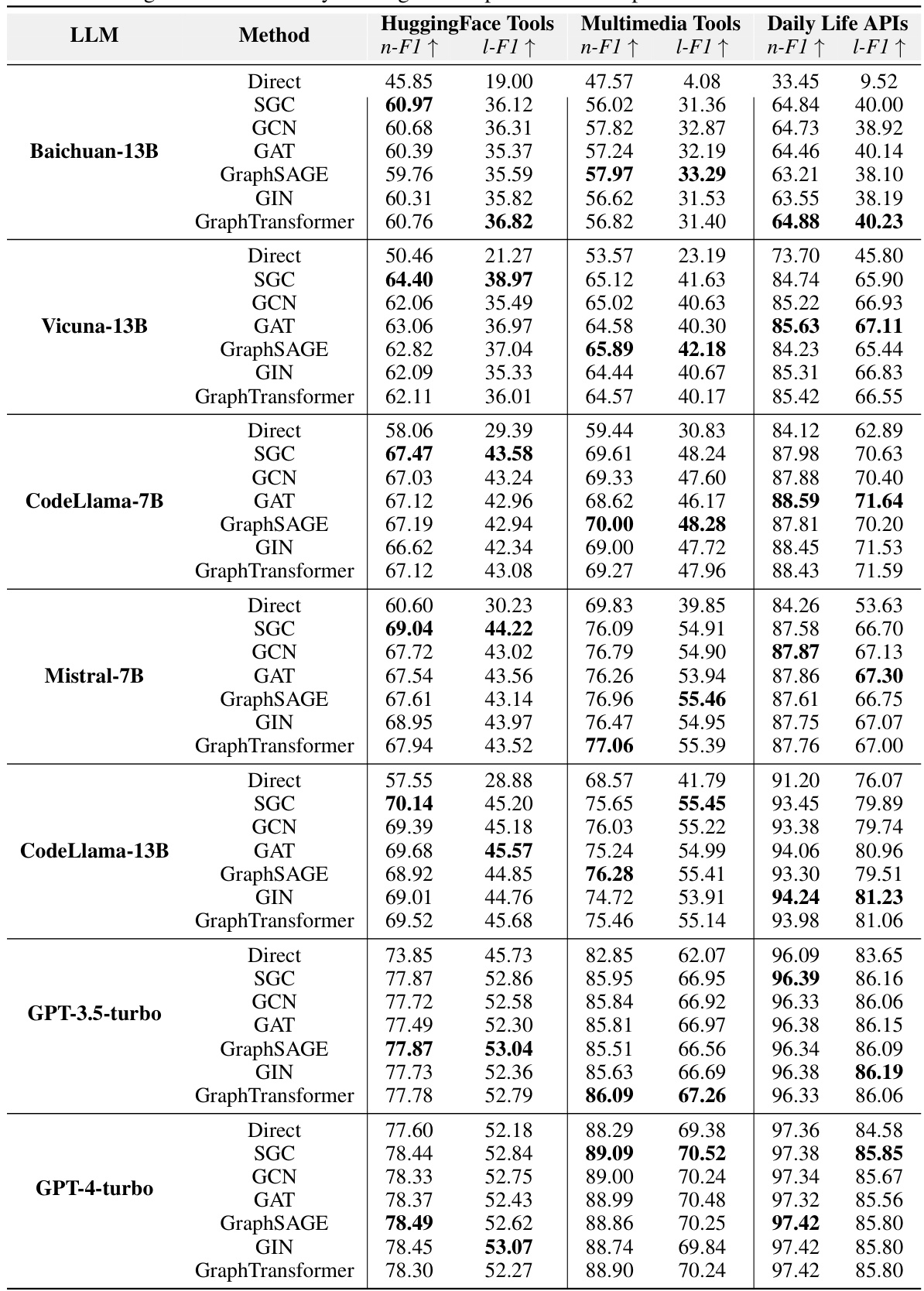

This table shows the performance of different graph neural networks (GNNs) for task planning, comparing them against the BeamSearch method which is a strong baseline from the GraphSearch approach. The results are presented for several large language models (LLMs) across three datasets (HuggingFace, Multimedia, and Daily Life). The table demonstrates the consistent improvement in task planning performance achieved by integrating GNNs with LLMs.

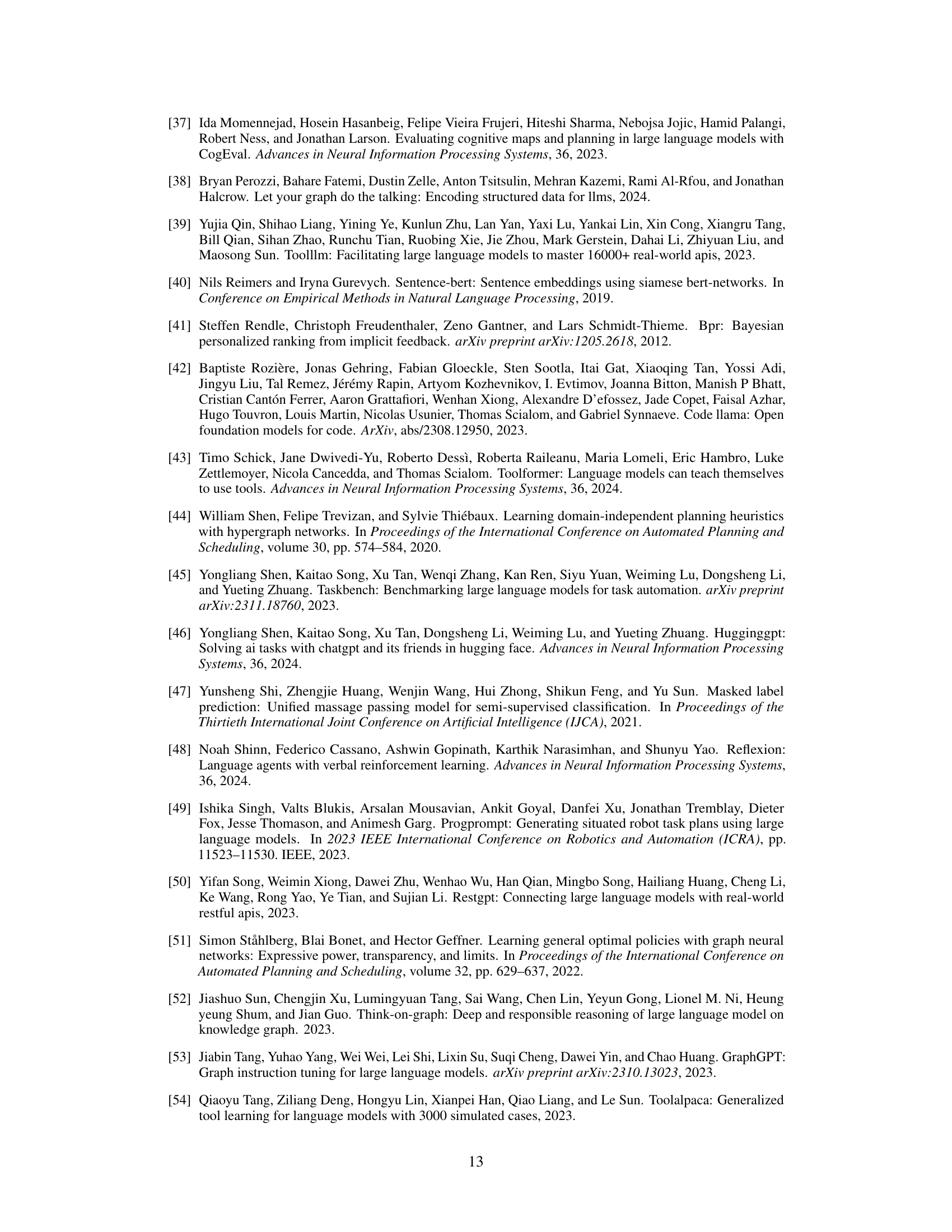

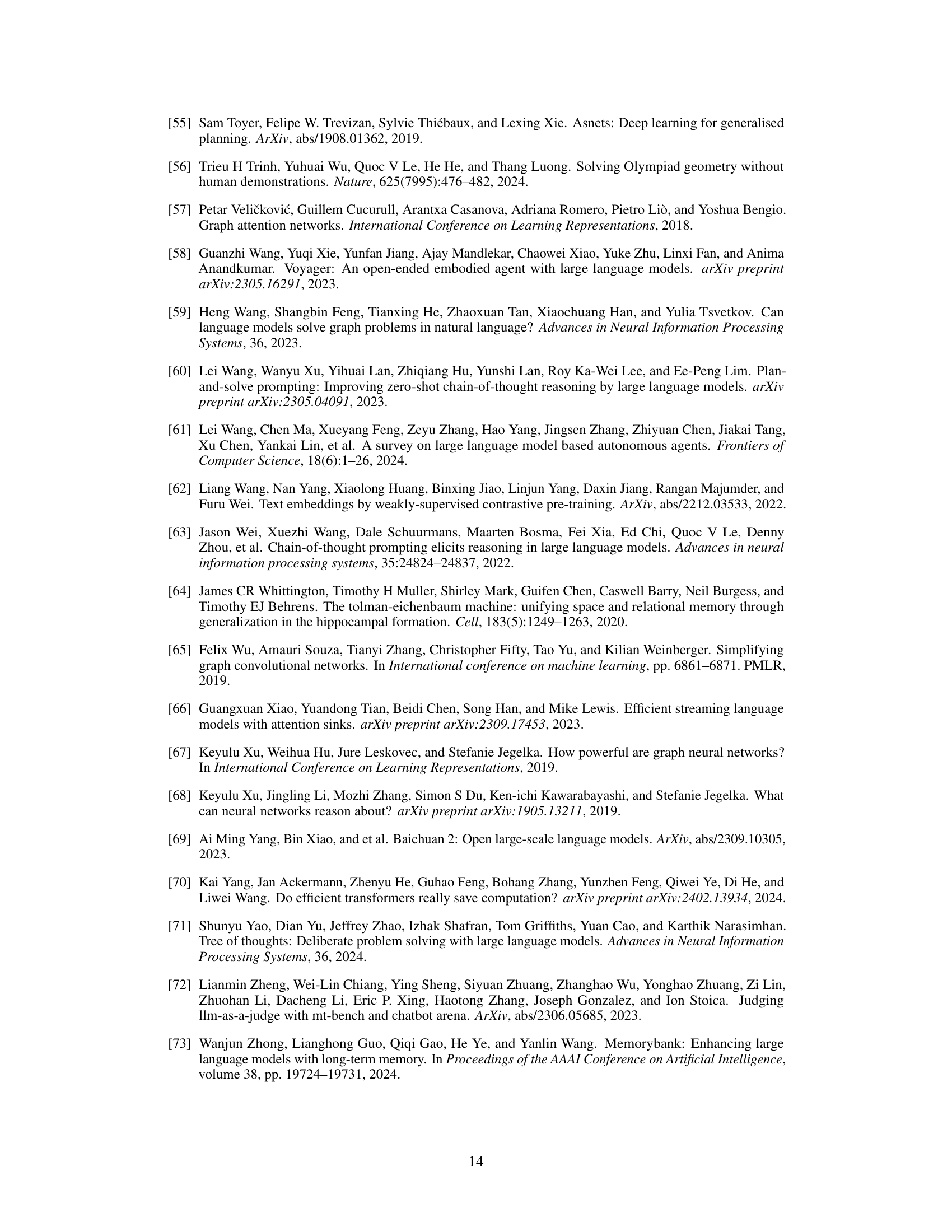

This table compares the performance of four different training-free methods for task planning across various LLMs and datasets. The methods include LLM’s direct inference, Greedy Search, Adaptive Search, BeamSearch, and the proposed SGC method. The table shows the Node F1-score, Link F1-score, and the number of tokens consumed for each method and LLM combination on HuggingFace, TaskBench Multimedia, Daily Life and RestBench datasets. It highlights the performance gains achieved by the SGC method compared to the other baselines.

This table compares the performance of three training-free methods for task planning: LLM’s Direct Inference, GraphSearch (with three variants: GreedySearch, AdaptiveSearch, and BeamSearch), and the proposed SGC method. The comparison is done across four datasets (HuggingFace, Multimedia, Daily Life, and RestBench) and several LLMs. The table shows Node F1-score, Link F1-score, and token consumption for each method and dataset, providing a quantitative assessment of their relative effectiveness and efficiency.

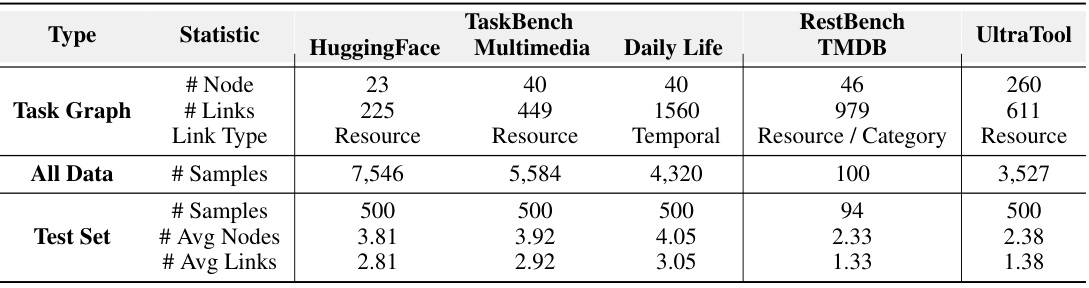

This table presents the statistics of four datasets used in the experiments, categorized by their source benchmark (TaskBench, RestBench, and UltraTool). For each dataset, it provides the number of nodes and links in the task graph, the type of links (Resource, Temporal, or Resource/Category), the total number of samples, and the average number of nodes and links in the test set. These statistics provide context for understanding the scale and characteristics of the experimental data used to evaluate the performance of the proposed task planning methods.

This table compares the performance of four different training-free methods for task planning across five different datasets and several LLMs. The methods compared are Direct Inference (LLM only), Greedy Search, Adaptive Search, Beam Search, and a proposed method using Sparse Graph Convolutions (SGC). The table shows Node F1-score, Link F1-score, and token consumption for each method, providing a quantitative comparison of their effectiveness and efficiency.

This table compares the performance of four different training-free methods for task planning across five different LLMs and four datasets. The methods compared are: LLM’s Direct Inference, Greedy Search, Adaptive Search, Beam Search, and SGC. The performance metrics used are Node F1-score (n-F1) and Link F1-score (l-F1), which measure the accuracy of predicted tasks and their dependencies respectively. The table also shows the token consumption for each method, providing a measure of efficiency. The performance of additional LLMs is detailed in Table 8.

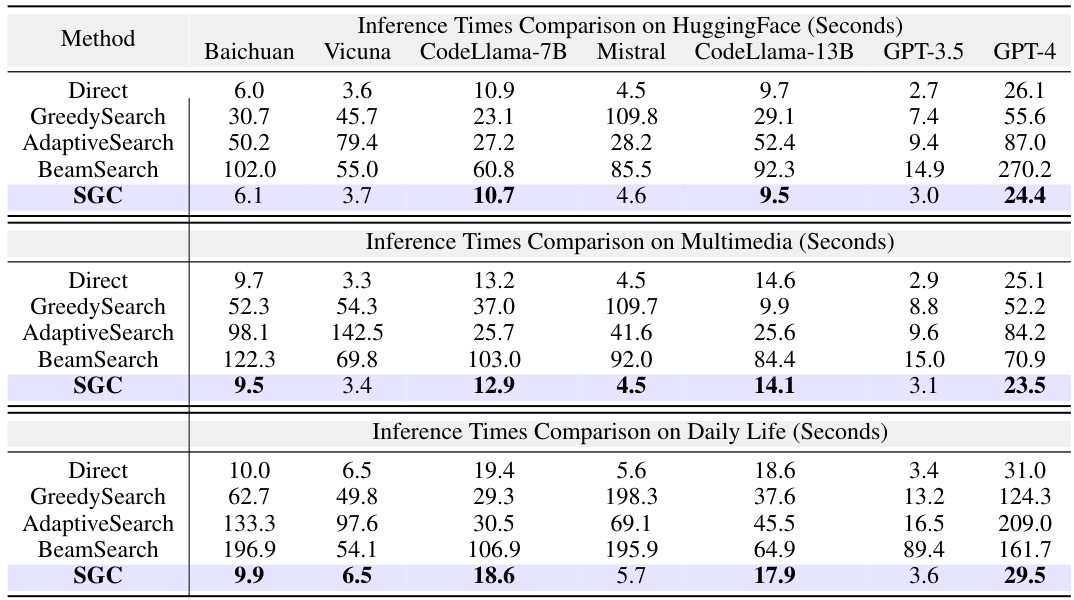

This table presents the inference time for different training-free methods across three datasets (HuggingFace, Multimedia, Daily Life). The inference times are broken down by LLM and method (Direct, GreedySearch, AdaptiveSearch, BeamSearch, SGC). The table highlights the significant speed advantage of the SGC method compared to others, especially the search-based methods (GreedySearch, AdaptiveSearch, BeamSearch).

This table compares the performance of several training-free methods for task planning across different LLMs and datasets. The methods compared include LLM’s direct inference, GraphSearch (with three variants: GreedySearch, AdaptiveSearch, and BeamSearch), and the proposed SGC method. The table reports Node F1-score, Link F1-score, and token consumption for each method and LLM on the HuggingFace, TaskBench (Multimedia, Daily Life), RestBench, and TMDB datasets. It indicates that the proposed SGC method outperforms other training-free methods in terms of accuracy and efficiency.

This table presents the performance of different Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for task planning when integrated with various Large Language Models (LLMs). It compares the performance of GNNs against a strong baseline method called BeamSearch. The table shows that all GNNs consistently improve the performance of LLMs on task planning across different datasets and LLMs.

This table compares the performance of three training-free methods for task planning: LLM’s Direct Inference, GraphSearch (with three variants: GreedySearch, AdaptiveSearch, and BeamSearch), and the proposed SGC method. The comparison is done across multiple datasets (HuggingFace, TaskBench Multimedia, TaskBench Daily Life, RestBench, and TMDB) and uses several LLMs. The table shows the Node F1-score, Link F1-score, and the number of tokens consumed by each method for each LLM and dataset. This allows for a direct comparison of performance and efficiency.

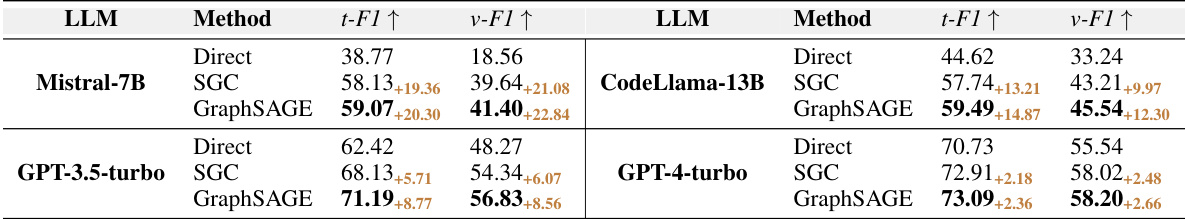

This table presents the performance of different methods in predicting task parameters on the HuggingFace dataset. It compares the accuracy of directly using LLMs for parameter prediction (Direct) against using LLMs after task selection with training-free SGC and training-required GraphSAGE. The metrics used are Parameter-Type F1-Score (Param t-F1) and Parameter-Value F1-Score (Param v-F1), which assess the accuracy of predicted parameter types and values respectively.

Full paper#