↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Multi-armed bandits (MABs) are widely used in online decision-making, but real-world applications often involve data privacy and robustness concerns. This paper investigates the interplay of local differential privacy (LDP) and robustness against Huber corruption and heavy-tailed rewards within MABs. The researchers examined two practical settings: LDP-then-Corruption (LTC), where privacy is applied before corruption, and Corruption-then-LDP (CTL), where corruption precedes privacy. Both settings present unique challenges.

The study presents the first tight characterization of mean estimation error under both LTC and CTL settings and leverages this to characterize the minimax regret in online MABs and sub-optimality in offline MABs. They introduce a unified algorithm achieving optimal or near-optimal performance in both settings. A key finding is that LTC is a much more challenging setting leading to worse performance guarantees compared to CTL, highlighting the critical interaction between privacy mechanisms and data corruption.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in privacy-preserving machine learning and robust statistics. It bridges the gap between these two important fields by studying the interplay between local differential privacy and robustness in the context of multi-armed bandits. The findings are particularly relevant for real-world applications where data privacy and robustness are critical concerns. The paper’s theoretical analysis and empirical results provide a solid foundation for future research in this area.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates three different scenarios combining local differential privacy (LDP) and Huber corruption with potentially heavy-tailed data. (1) LDP-then-Corruption (LTC): LDP is applied first, followed by corruption. (2) Corruption-then-LDP (CTL): Corruption occurs first, then LDP is applied. (3) C-LDP-C: Corruption happens before and after the LDP mechanism. The figure highlights the order in which privacy and robustness mechanisms are applied, which impacts the overall result.

In-depth insights#

LDP vs. Robustness Tradeoffs#

The interplay between local differential privacy (LDP) and robustness against adversarial corruption or heavy-tailed data presents a complex trade-off. Strengthening LDP, by reducing the privacy budget (ε), generally weakens robustness. This is because stronger privacy mechanisms often add more noise, making the data less reliable and more susceptible to corruption. Conversely, prioritizing robustness can compromise privacy, as less noise might lead to more accurate but less private results. The order of applying LDP and corruption also matters. LDP-then-corruption (LTC) is significantly harder than corruption-then-LDP (CTL), exhibiting larger errors and regret. This difference arises because the privacy mechanism’s noise-adding process reduces the effectiveness of subsequent corruption mitigation. The optimal balance between privacy and robustness needs careful consideration of the specific application, threat model, and data characteristics, with no single solution universally suitable. Tight theoretical bounds are crucial in navigating this trade-off to design mechanisms that provide appropriate levels of both privacy and robustness.

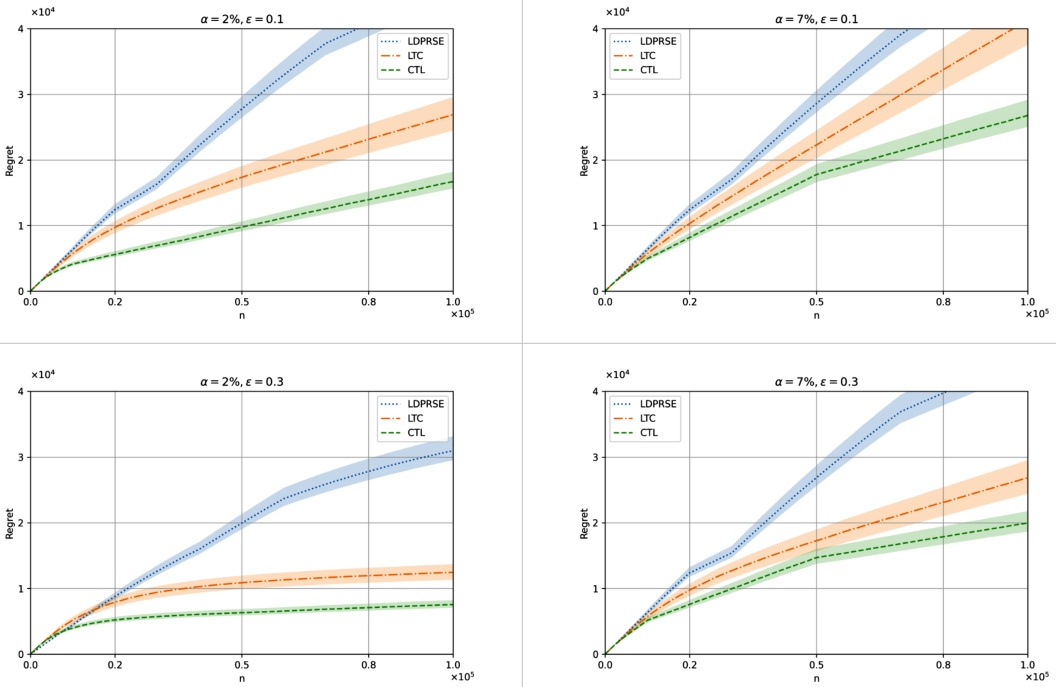

LTC vs. CTL Regrets#

The comparison of regrets under LDP-then-Corruption (LTC) and Corruption-then-LDP (CTL) reveals a crucial interplay between the order of privacy mechanisms and corruption. LTC consistently demonstrates higher regrets than CTL, suggesting that introducing local differential privacy before corruption leads to a more vulnerable system. This is because in LTC, any corruption after the application of LDP can magnify the error, significantly impacting the estimation quality. The extent of this impact is heavily influenced by the privacy budget (ε) and corruption level (α), with smaller ε and larger α exacerbating the difference in regrets. This highlights the importance of considering the sequence of privacy and robustness mechanisms when designing algorithms in real-world scenarios where data might be vulnerable to both privacy attacks and malicious corruptions.

Huber Corruption Models#

Huber corruption models are crucial for evaluating the robustness of algorithms in scenarios where data may be contaminated by outliers or adversarial attacks. These models assume that a fraction of the data points are arbitrarily corrupted, while the remaining data follows a specific distribution. The parameter α in the Huber model controls the level of corruption, representing the fraction of corrupted data points. A key advantage of the Huber model is that it doesn’t require explicit knowledge of the nature or source of the corruption. This is highly practical as real-world datasets often contain anomalies of unknown origins. The Huber model offers a balance between robustness to outliers and efficiency in handling normally distributed data. It’s particularly relevant for analyzing the performance of algorithms in machine learning, statistics, and privacy-preserving mechanisms where robustness to outliers is crucial for reliable and fair results. However, a key challenge is determining the optimal value of the corruption parameter α, which can significantly affect the performance assessment. Extensive simulations are needed for proper calibration and an appropriate sensitivity analysis must be conducted to assess the algorithms performance over a range of α values.

Algorithm Optimality#

Analyzing algorithm optimality in a research paper requires a nuanced understanding of its context. A claim of optimality often hinges on specific assumptions and limitations, such as the data distribution, the presence of noise or adversarial attacks, and the privacy constraints. A truly optimal algorithm would achieve the best possible performance under all circumstances, which is often practically impossible. The paper likely establishes optimality relative to a defined class of algorithms or under specific conditions; it’s crucial to identify these constraints. The proof of optimality is a cornerstone, demanding rigorous mathematical analysis and often involving lower and upper bounds to demonstrate that no other algorithm within the given constraints can perform better. The paper’s experimental results should validate theoretical findings, showing near-optimal performance under various scenarios but also highlighting potential limitations or deviations. Careful scrutiny of the assumptions, the definition of optimality, and the robustness of the results is needed to gauge the practical implications and the broader significance of the algorithm’s optimality claim.

Future Research#

The “Future Research” section of a PDF research paper on locally private and robust multi-armed bandits could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass more complex bandit settings such as contextual bandits or linear bandits is a natural next step. This would involve developing new algorithms and analyzing their performance under various privacy and robustness constraints. Investigating the impact of different privacy mechanisms beyond local differential privacy (LDP), such as central DP or shuffled DP, would offer a broader understanding of the trade-offs between privacy, robustness, and utility. The current work focuses on Huber contamination; exploring alternative corruption models that capture more realistic scenarios (e.g., adversarial attacks) is warranted. Furthermore, developing more efficient algorithms with lower computational costs is crucial for practical applications. Finally, and importantly, empirical studies on real-world datasets would be beneficial to validate the theoretical findings and assess the practical effectiveness of the proposed algorithms under various real-world conditions. The research could also explore the interplay between fairness and robustness in the context of private bandit algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

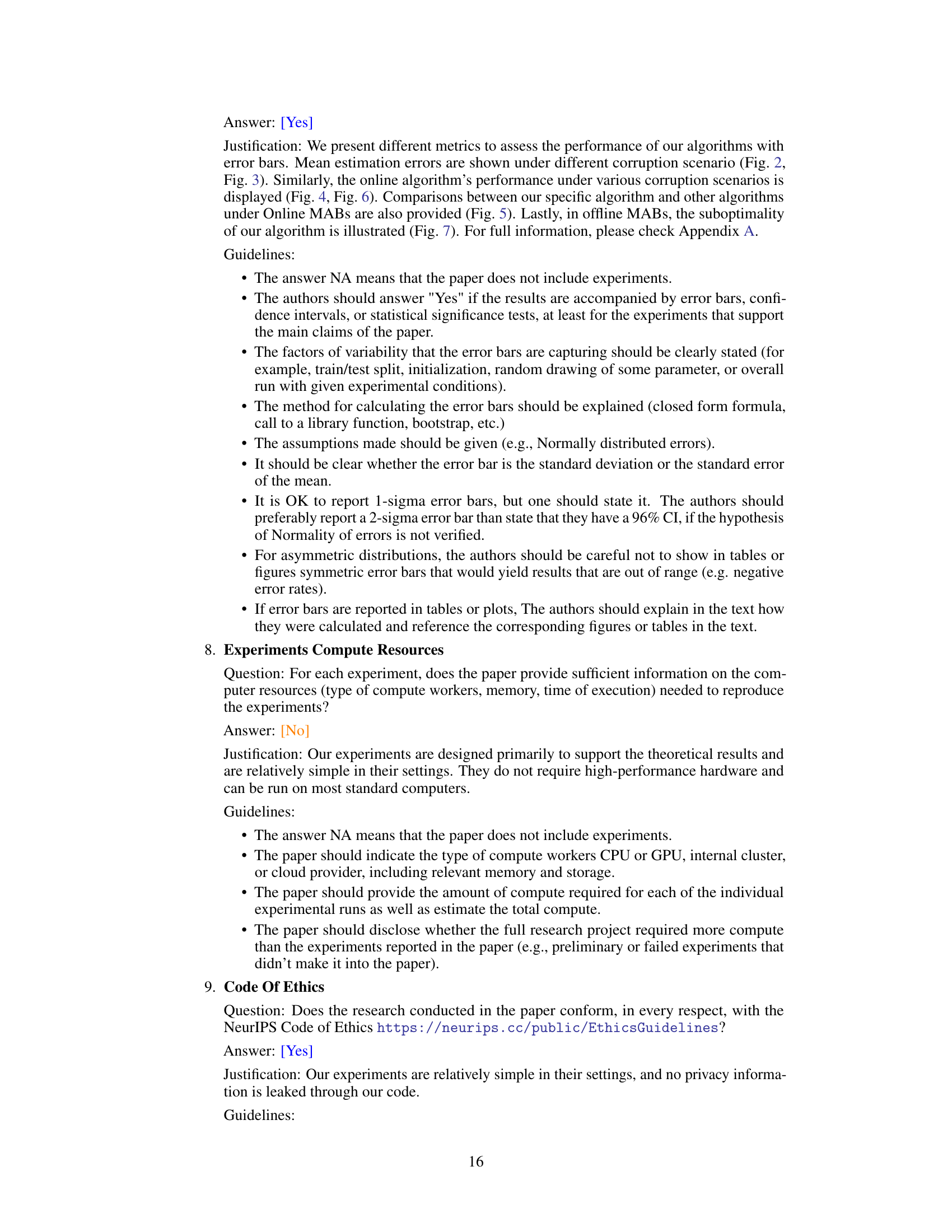

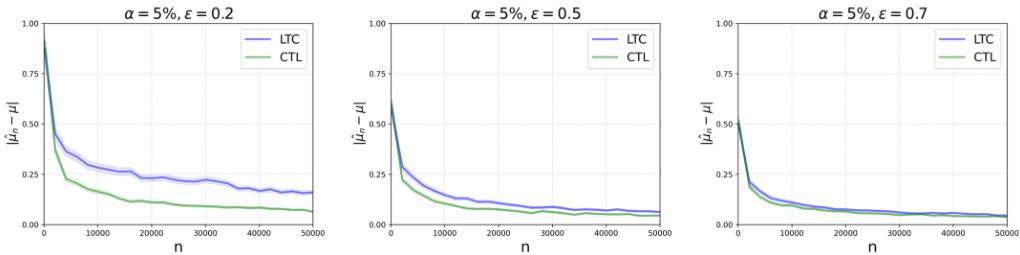

This figure shows the mean estimation error under different corruption levels and privacy budgets. The x-axis represents the sample size (n), and the y-axis represents the mean estimation error. Each plot shows the results for both LTC (LDP-then-corruption) and CTL (corruption-then-LDP) settings. The plots are grouped by corruption level (α) and privacy budget (ε). The results demonstrate that the mean estimation error is higher under LTC than under CTL, and the difference increases as the privacy budget decreases or the corruption level increases. The results are consistent with the theoretical findings in Theorem 1, which provides a tight characterization of the mean estimation error under both LTC and CTL settings.

This figure shows the mean estimation error under weak Huber corruption for different sample sizes (n). It compares the Locally Differentially Private then Corruption (LTC) setting against the Corruption then Locally Differentially Private (CTL) setting, illustrating the impact of varying privacy budgets (ε). The results demonstrate that under weak Huber corruption, the estimation error decreases as the sample size increases in both LTC and CTL settings.

This figure shows the mean estimation error under different privacy budget (epsilon) and corruption level (alpha) for both LTC (LDP then corruption) and CTL (corruption then LDP) settings. It demonstrates the impact of privacy and corruption on the estimation error, particularly highlighting the separation result of (alpha/epsilon)^(1-1/k) for LTC and alpha^(1-1/k) for CTL.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed algorithms against LDPRSE (an existing algorithm for online MABs under LDP and heavy-tailed rewards) under weak corruption. The results show that the proposed algorithms outperform LDPRSE, especially as corruption increases. This highlights the advantages of the proposed algorithms in scenarios where additional corruptions exist.

This figure displays the results of mean estimation experiments under different settings (LTC and CTL) with strong Huber corruption. The results demonstrate the effects of varying the corruption level (α) and privacy budget (ε) on the estimation error. The plots show that for a fixed privacy budget, increasing the corruption level leads to a greater estimation error, and for a fixed corruption level, stronger privacy (smaller ε) also leads to a higher estimation error. The plots also visually demonstrate that the LTC setting generally leads to larger estimation errors than the CTL setting.

This figure displays the mean estimation error under different privacy budgets (epsilon) and corruption levels (alpha) for both LDP-then-Corruption (LTC) and Corruption-then-LDP (CTL) settings. The strong Huber corruption model replaces each data point with a large value (M+1) with probability alpha in LTC, and with M with probability alpha in CTL. The results illustrate the impact of privacy and corruption on the mean estimation error, showing a separation between LTC and CTL settings that becomes more pronounced as epsilon decreases (stronger privacy) and alpha increases (stronger corruption).

Full paper#