↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reconstructing 3D scenes from videos, especially those with dynamic content like casual videos, is computationally expensive and challenging. Existing methods often rely on simplifying assumptions or require lengthy optimization, limiting their real-world applicability. This paper tackles these challenges by proposing a novel approach that directly processes 2D point tracks extracted from videos. The main difficulty lies in the ill-posed nature of inferring 3D information from 2D data. This is an inherently ambiguous problem.

The proposed approach, called TRACKSTO4D, leverages a deep neural network to learn the mapping from 2D point tracks to 3D structure and camera poses. This learning-based approach avoids the need for time-consuming optimization. The method cleverly integrates a low-rank movement assumption to address the ill-posed nature of the problem and incorporates the symmetries present in 2D point tracks data. TRACKSTO4D demonstrates substantial improvements in inference speed and accuracy, outperforming other state-of-the-art methods while generalizing exceptionally well to unseen data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents TRACKSTO4D, a novel and efficient method for 3D reconstruction from casual videos. It addresses the long-standing challenge of handling dynamic scenes in casual videos, offering significant improvements in speed and accuracy compared to existing methods. This opens new avenues for research in areas like robot navigation and autonomous driving, where real-time 3D understanding from everyday video is crucial.

Visual Insights#

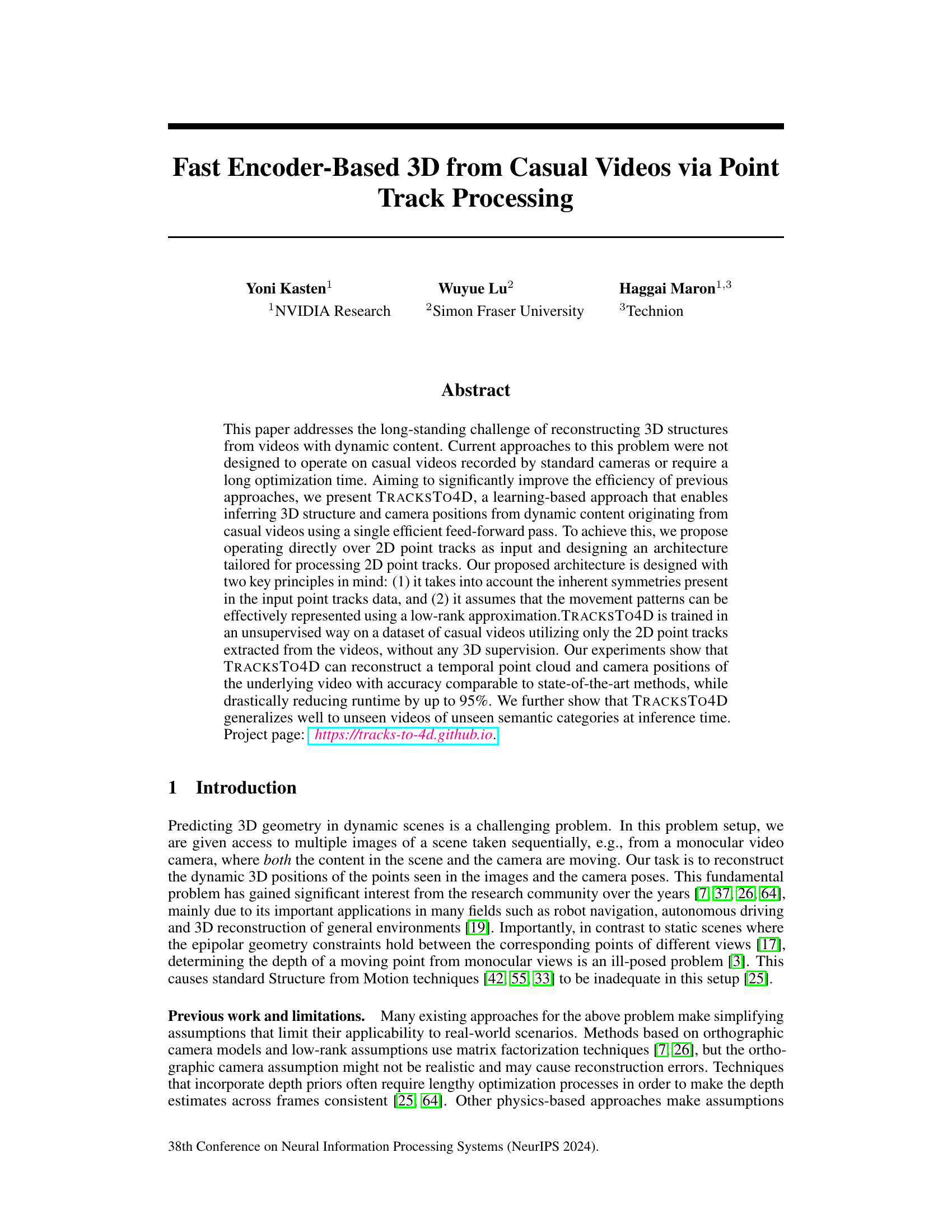

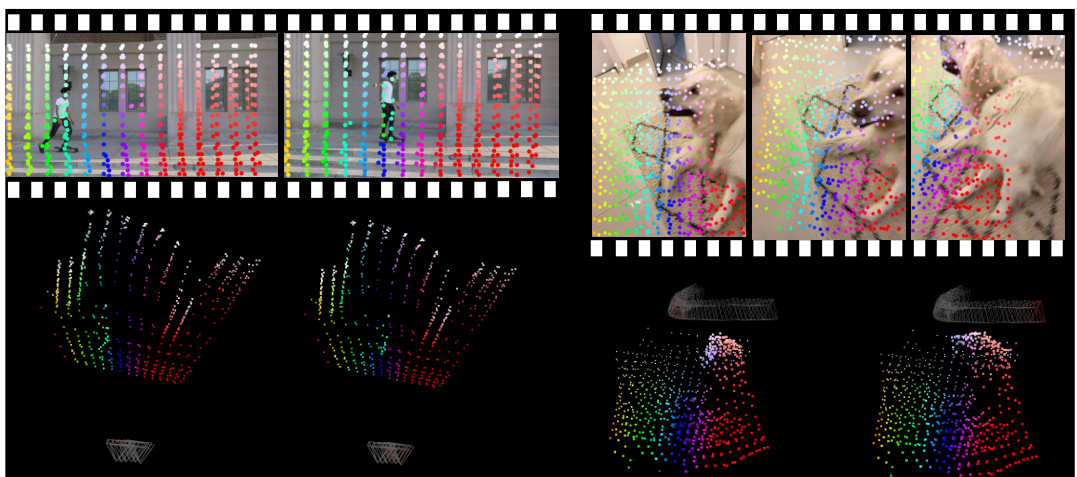

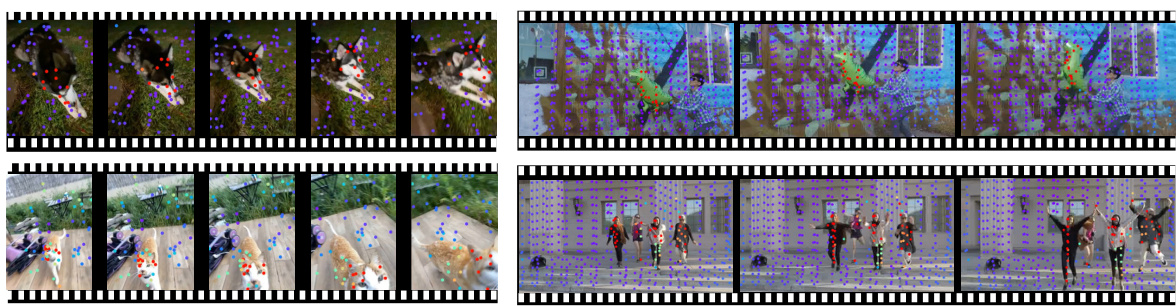

This figure illustrates the TRACKSTO4D architecture, which takes 2D point tracks from casual dynamic videos as input and predicts 3D locations, camera motion, and per-point movement levels in a single feed-forward pass. The architecture uses multi-head attention layers to process the 2D point tracks, alternating between time and track dimensions. The output includes camera poses, per-frame 3D point clouds, and per-point movement values, which are used to calculate reprojection error losses. The color-coding of the 3D points visually represents their predicted motion levels.

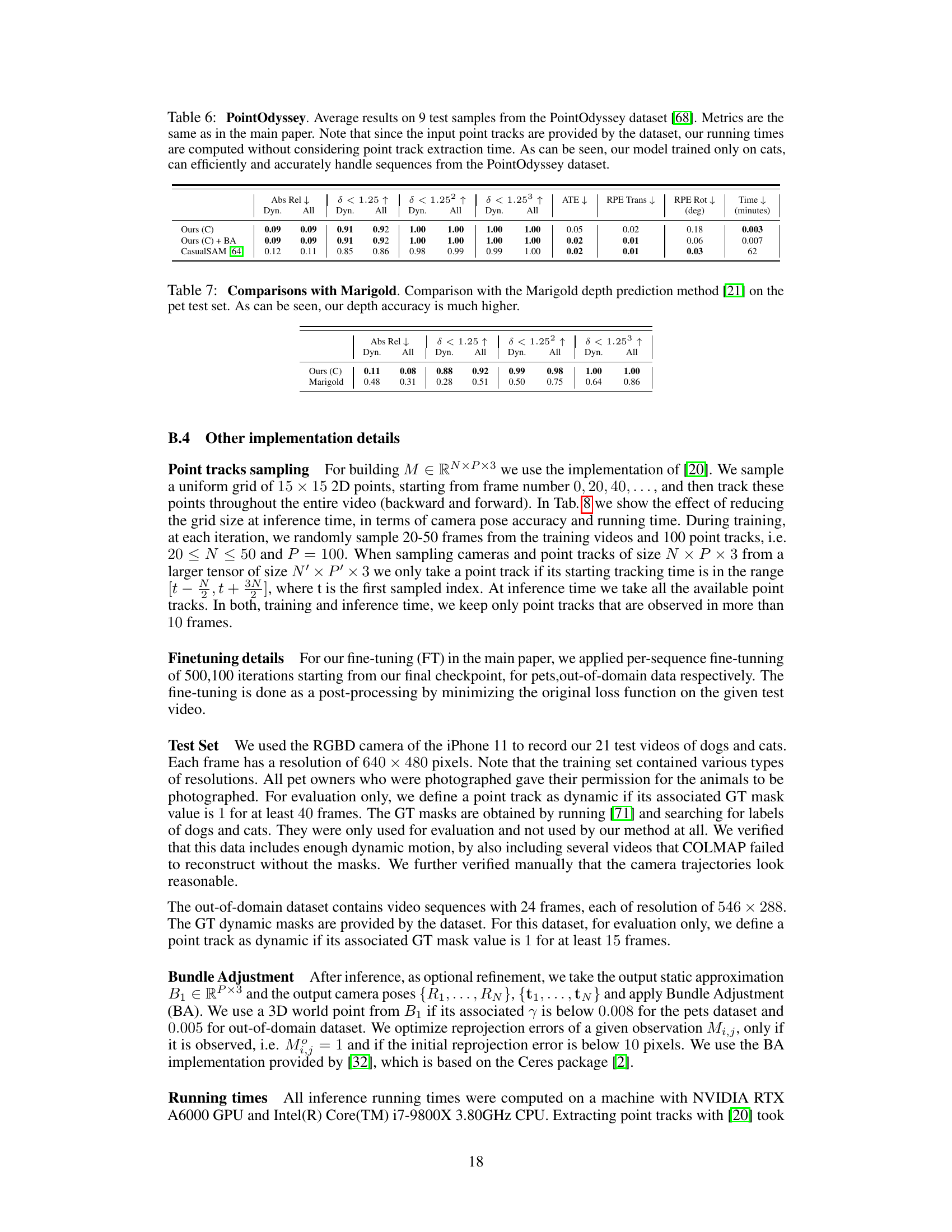

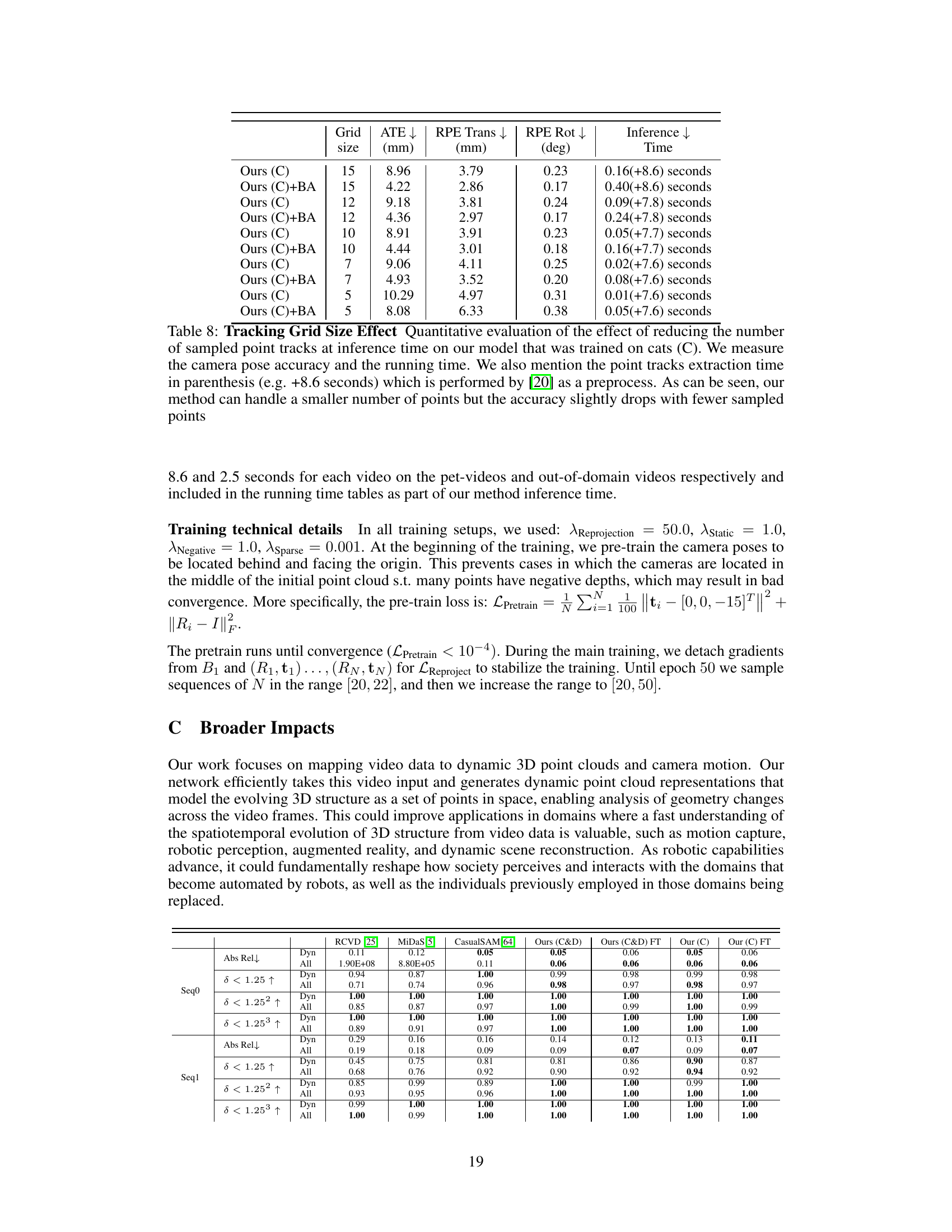

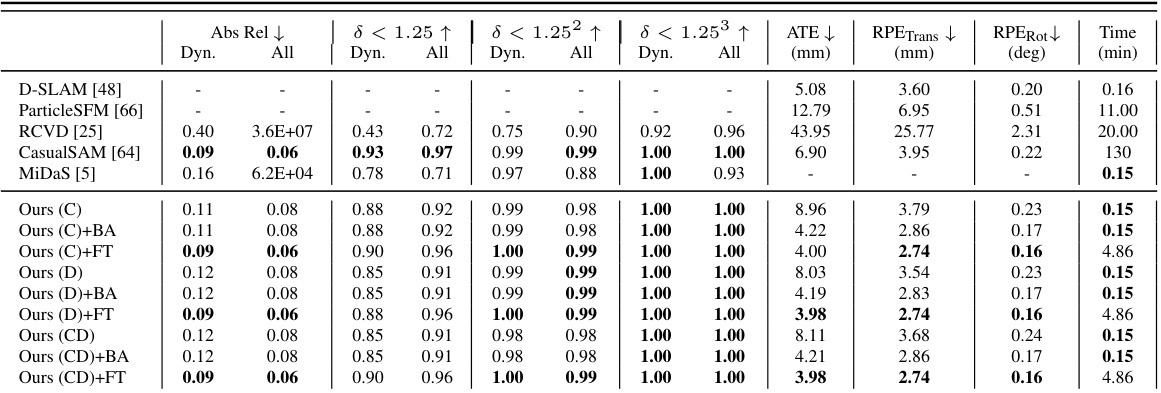

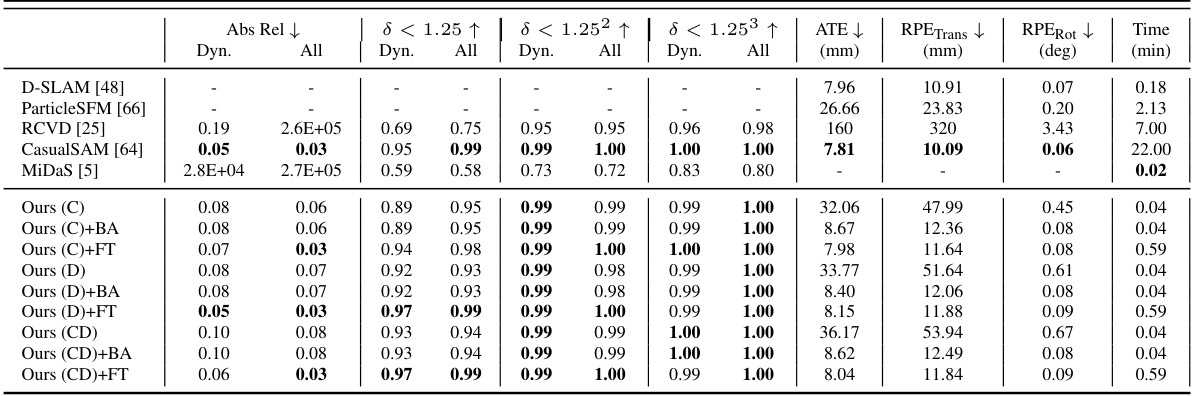

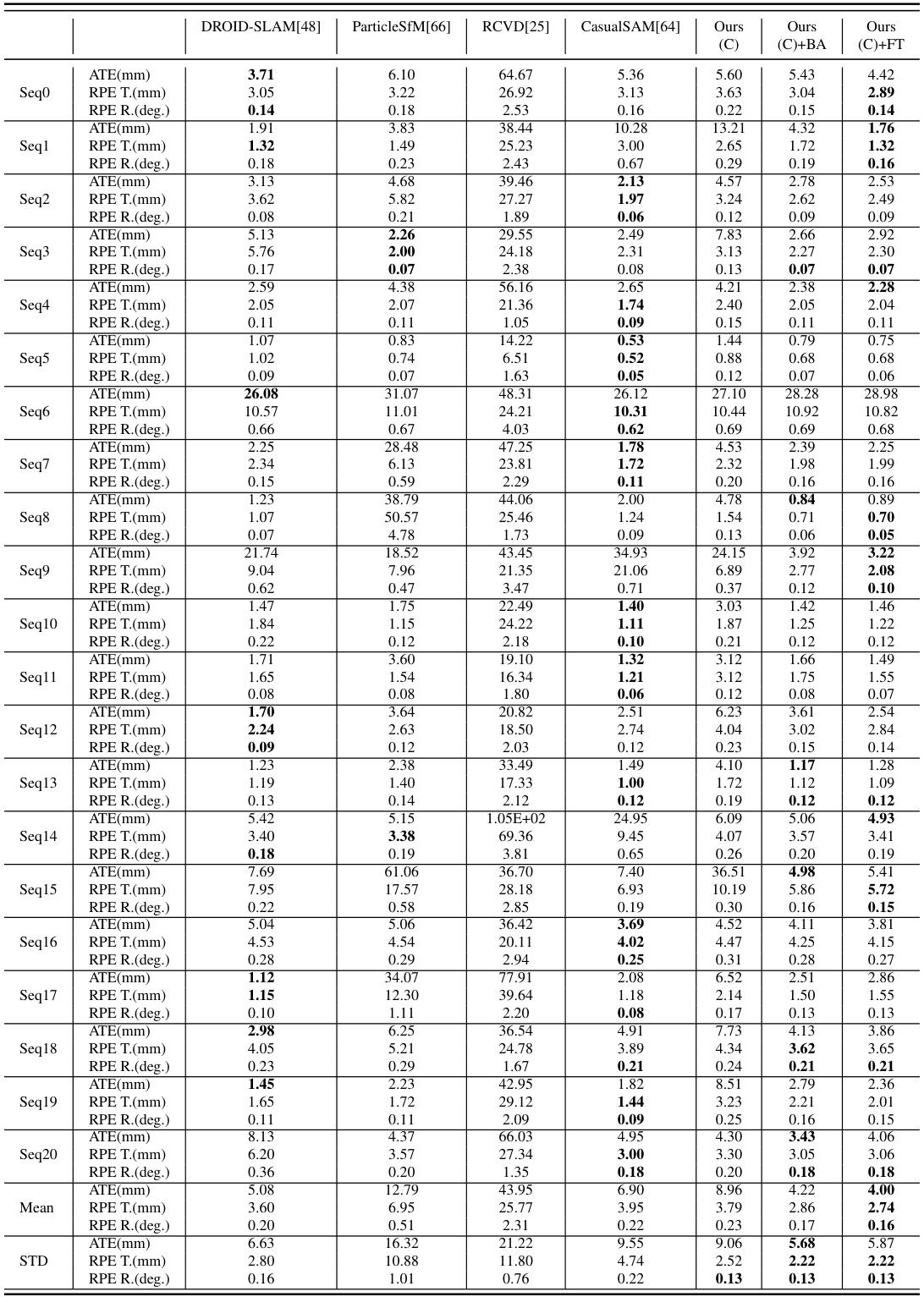

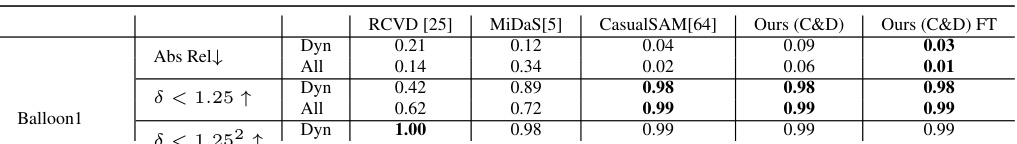

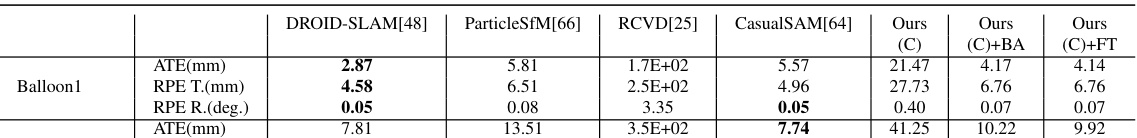

The table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed TRACKSTO4D method against several baseline methods for 3D reconstruction from video. The top section shows results from existing methods. The bottom section presents results for TRACKSTO4D under various training configurations (trained on only cats, only dogs, or both) and with or without post-processing steps such as Bundle Adjustment (BA) and fine-tuning (FT). Metrics include Absolute Relative error (Abs Rel), percentage of points with δ < 1.25, 2, and 3, Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE), Relative Pose Error Translation (RPETrans), Relative Pose Error Rotation (RPERot), and inference time. Lower values for Abs Rel, ATE, RPETrans, and RPERot, and higher values for δ metrics are better.

In-depth insights#

Dynamic Scene 3D#

Reconstructing 3D scenes from videos featuring dynamic content presents a formidable challenge. Approaches tackling this problem often struggle with casual videos due to inherent complexities like camera and object motion. A key issue is the ill-posed nature of depth estimation in dynamic scenes, exacerbated by the lack of consistent epipolar geometry constraints found in static scenes. Successful methods often rely on strong assumptions, such as orthographic camera models or low-rank movement, which limit applicability to real-world scenarios. Efficient learning-based techniques are highly desirable but require careful consideration of input data and architectural design. The effectiveness hinges upon handling inherent symmetries in point tracks while simultaneously incorporating low-rank approximations to constrain the inherently under-determined problem of 3D reconstruction from 2D video data. Unsupervised learning, using only 2D point track information, offers a pathway to robust and efficient solutions, avoiding the need for expensive 3D supervision, leading to faster inference times. Addressing these challenges is crucial for advancing applications in fields such as autonomous driving, robotics and AR/VR.

Point Track Input#

The concept of ‘Point Track Input’ in the context of 3D reconstruction from video presents a powerful paradigm shift. Instead of processing raw image pixels, which are high-dimensional and contain considerable irrelevant information, the method focuses on sparse 2D point tracks. These tracks, representing the movement of salient points over time, capture the essential dynamics of the scene and are significantly lower dimensional, reducing computational complexity and improving efficiency. The use of point tracks leverages the strengths of modern point tracking algorithms, and allows for the inherent symmetries in the data (permutation invariance of points and approximate time translation invariance) to be explicitly accounted for within the network architecture. This leads to improved generalization across diverse scenes and video types. Furthermore, using point tracks sidesteps the challenges posed by ill-posedness in reconstructing 3D geometry from monocular video by reducing ambiguity. By directly working with already extracted, meaningful features rather than raw pixel data, this approach offers a more robust and efficient route to accurate 3D scene and camera pose estimation.

Equivariant Network#

Equivariant neural networks are designed to respect inherent symmetries within the data. In the context of processing 2D point tracks from videos, this is crucial because the order of points within a frame doesn’t change the underlying 3D structure. An equivariant network elegantly handles this by producing outputs that transform consistently with the input transformations. This property is particularly advantageous when dealing with dynamic scenes where points move unpredictably; equivariance ensures that the network’s predictions are robust to permutations in the input order and effectively captures the underlying relationships between points across frames. This leads to improved accuracy and generalization compared to standard methods that ignore these symmetries, especially in casual videos where point tracking is inherently noisy and the underlying symmetries are often not immediately obvious. The low-rank movement assumption further enhances the network’s performance, by exploiting the inherent symmetries, resulting in a more efficient and stable representation. This combination of equivariance and low-rank modeling addresses the inherent ill-posed nature of the problem, making it suitable for real-world applications.

Low-rank Movement#

The concept of ‘Low-rank Movement’ in the context of reconstructing 3D structures from videos likely refers to a method that constrains the complexity of the 3D motion present in the scene. This is crucial because directly inferring 3D motion from just 2D video data is ill-posed. A low-rank representation assumes that the movement can be well-approximated by a smaller number of underlying basis functions or components, reducing the dimensionality of the problem and making it more tractable. This approach leverages the observation that in many dynamic scenes, the movement patterns are not arbitrary but exhibit structure and regularity that can be efficiently captured by a low-dimensional subspace. By enforcing a low-rank constraint, the method regularizes the solution, preventing overfitting and improving the robustness to noise and ambiguity in the input data. This is particularly useful when dealing with casual videos, which often contain noisy or incomplete data, making low-rank methods a powerful tool for practical 3D reconstruction. The effectiveness relies on the assumption that the low-rank approximation is valid for the given scene, which may not always hold true for complex or highly dynamic scenarios.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of this research paper would ideally explore several key areas. Firstly, improving the robustness of point tracking is crucial, addressing limitations in handling fast movements and occlusions, potentially through incorporating more sophisticated tracking algorithms or exploring alternative input modalities beyond visual data. Secondly, generalizing to more complex scenes is a major challenge. The current method excels in relatively controlled environments; exploring its performance on videos with heavy clutter, more varied camera motion and diverse lighting conditions would validate its broader applicability. Thirdly, investigating methods to reduce computational cost would significantly improve practicality. Although this method is fast, reducing its runtime even further, perhaps through architectural improvements or model compression, would make it more accessible and applicable to real-time scenarios. Finally, exploring diverse applications of this 3D reconstruction capability beyond pet videos, such as autonomous driving, robotics, or extended reality, would highlight its versatile potential and showcase its impact across various fields.

More visual insights#

More on figures

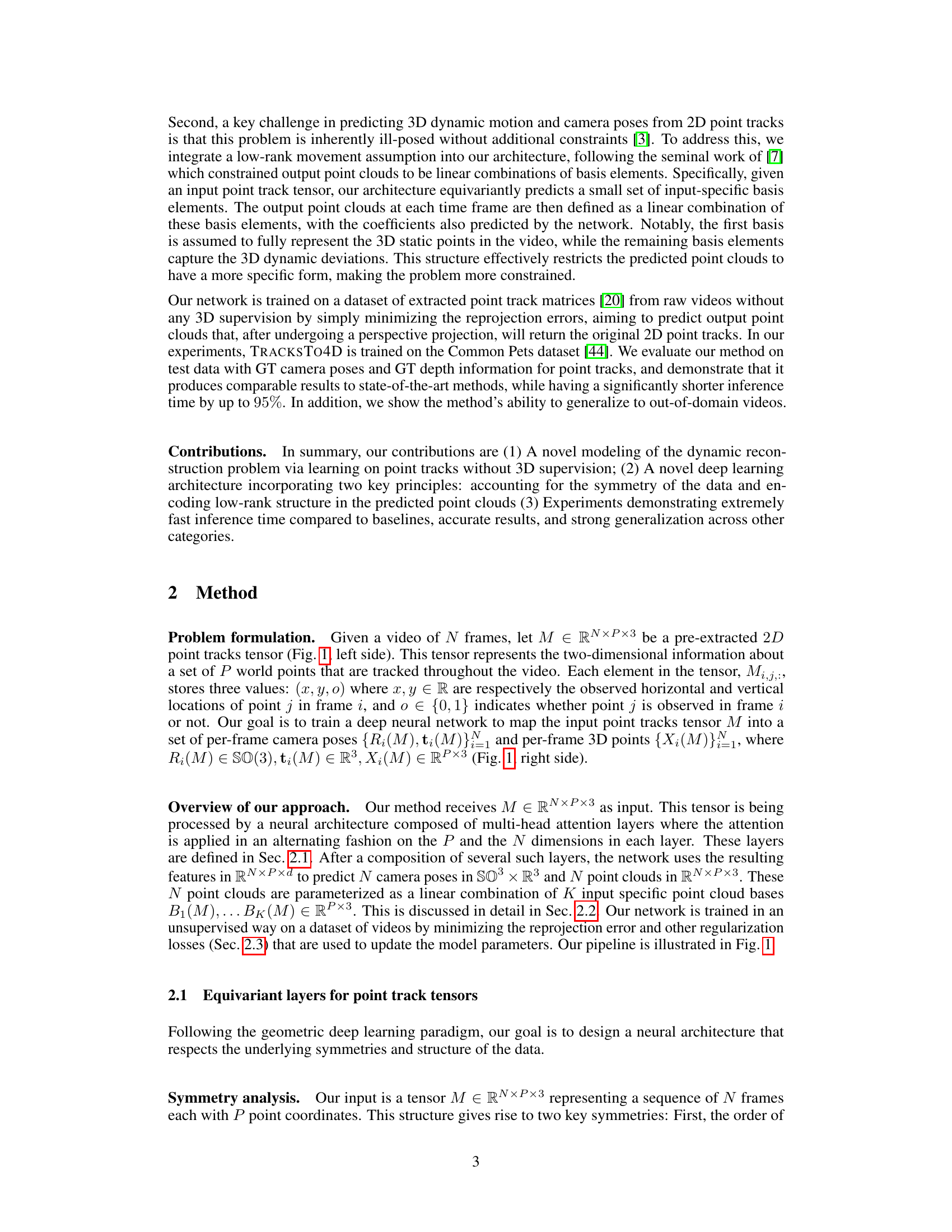

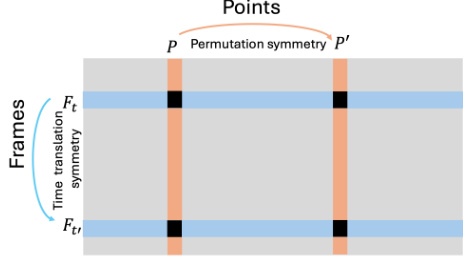

This figure illustrates the symmetries present in the input data (point track tensors) for the TRACKSTO4D model. The vertical axis represents frames in a video sequence, exhibiting temporal or time translation symmetry. The horizontal axis represents points being tracked across the frames, exhibiting permutation symmetry, meaning the order of points does not affect the underlying relationships. These symmetries are central to the design of the TRACKSTO4D architecture, which is designed to process these inputs in an equivariant way, preserving these symmetries in the processing and improving generalization capabilities.

This figure illustrates the TRACKSTO4D architecture and workflow. The input is a set of 2D point tracks from a video. The network uses multi-head attention to process these tracks and predict 3D point cloud locations and camera poses in a single feedforward pass. The output is visualized with the 3D points color-coded according to their predicted movement levels (red for high motion, purple for low motion). The reprojection error is calculated by comparing the projected 3D points back onto the 2D frames with the original 2D tracks.

This figure illustrates the TRACKSTO4D architecture and its workflow. The input is a set of 2D point tracks extracted from a video. The architecture uses multi-head attention to process the tracks, alternating between time and track dimensions. The output is the reconstructed 3D point cloud, camera poses, and per-point movement levels. The colors of the 3D points represent their motion levels (red for high motion, purple for low). The reprojection error is calculated to evaluate the accuracy of the reconstruction.

More on tables

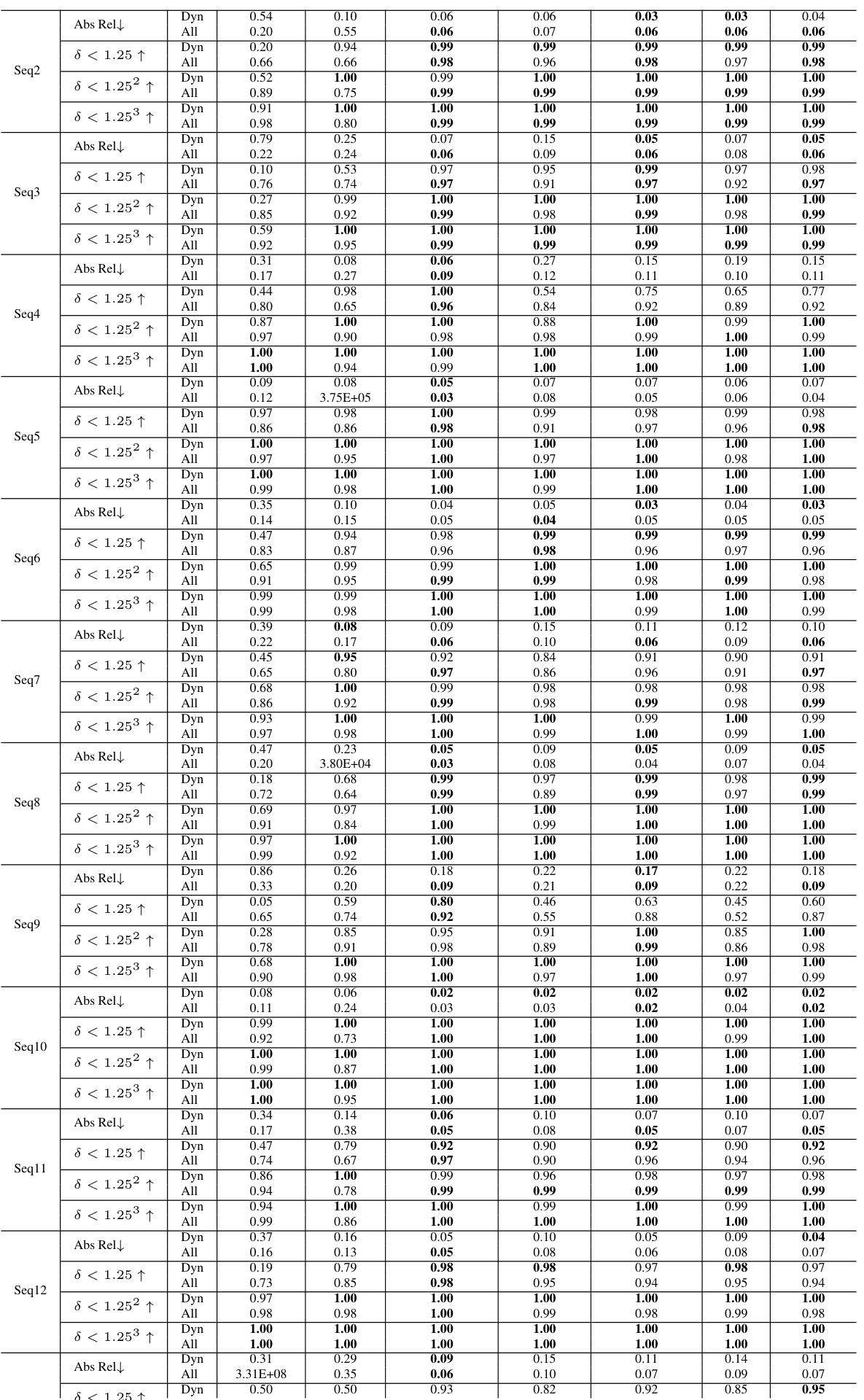

This table presents the quantitative results of TRACKSTO4D on videos from the Nvidia Dynamic Scenes Dataset [62], which are different from the training data (Common Pets Dataset [44]). It compares the performance of TRACKSTO4D against several baselines using metrics such as Absolute Relative error, percentage of points with depth error less than 1.25, 1.25^2, and 1.25^3 times the ground truth depth, Absolute Translation Error (ATE), Relative Pose Error (Translation and Rotation), and inference time. Different training configurations of TRACKSTO4D (trained on cats, dogs, or both) are evaluated, along with optional Bundle Adjustment and Fine-tuning.

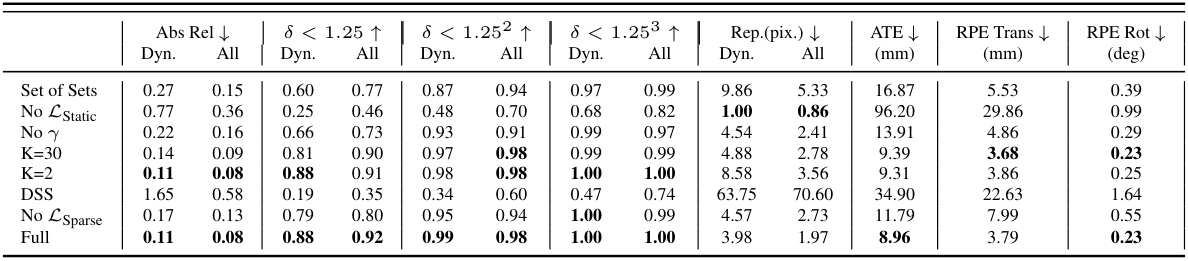

This ablation study analyzes the impact of different components of the proposed TRACKSTO4D model on its performance. It systematically removes or modifies parts of the architecture (e.g., using different attention mechanisms, removing specific loss terms, altering the number of basis elements) and evaluates the resulting effect on key metrics such as Absolute Relative Error (Abs Rel), percentage of points with depth error less than 1.25, 1.25^2, 1.25^3, reprojection error, absolute trajectory error (ATE), relative pose translation and rotation error (RPE Trans, RPE Rot). This allows researchers to understand the contribution of each component and to identify the most crucial parts of the model’s design.

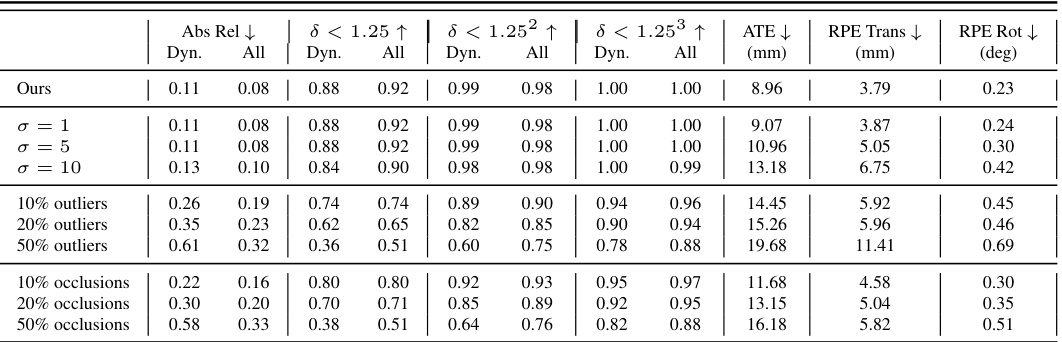

This table presents an ablation study on the robustness of the proposed method to noisy and incomplete point track data. It shows the effect of adding Gaussian noise, replacing tracks with outliers, and simulating occlusions on the accuracy of the method. The results demonstrate that the model is robust to a significant level of noise and missing data.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method using point tracks from two different tracking methods: CoTracker and TAPIR. It shows that the method is robust to the choice of tracking method, and that performance improves further with fine-tuning.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for 3D reconstruction and camera pose estimation using casual videos of cats and dogs. The top section shows results from baseline methods, while the bottom section details the performance of the proposed TRACKSTO4D method under various configurations. Different training configurations are compared, including training only on cats (C), only on dogs (D), or on both (CD). Post-processing techniques such as Bundle Adjustment (BA) and fine-tuning (FT) are also evaluated.

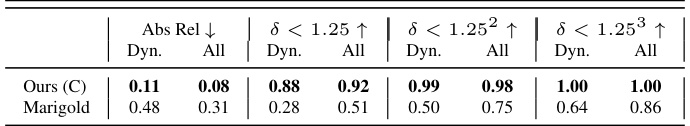

This table compares the depth accuracy of the proposed method (TRACKSTO4D) with the Marigold method on the pet test set. It shows metrics such as Absolute Relative error, percentage of points with depth error less than 1.25, 1.25^2, and 1.25^3. The results demonstrate that TRACKSTO4D achieves significantly higher depth accuracy compared to Marigold.

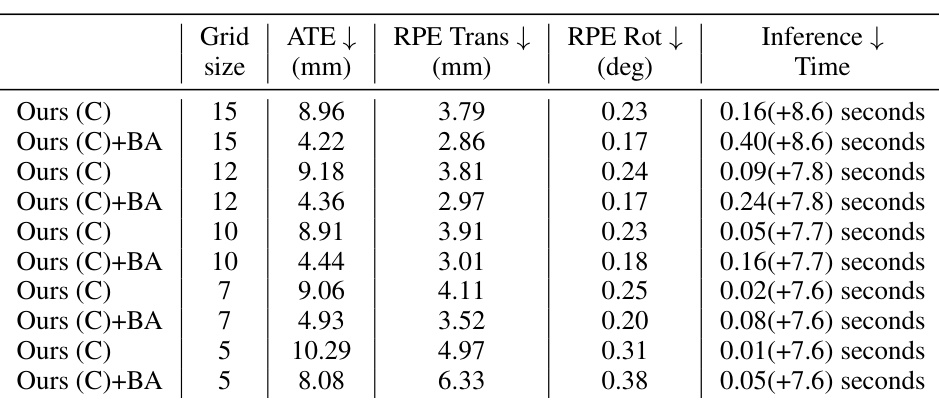

This table shows the effect of reducing the number of point tracks used as input to the model at inference time. The experiment was run using the model trained on the ‘cat’ category. It shows the camera pose accuracy (ATE, RPE Trans, RPE Rot) and inference time for different grid sizes (number of points). Inference time excludes the point track extraction time, which is noted separately in parentheses.

This table presents a comparison of different methods for 3D reconstruction and camera pose estimation from casual videos of pets. The top section shows baseline methods’ results, while the bottom section presents the results obtained by the proposed TRACKSTO4D method using various configurations (training only on cats, only on dogs, or on both; with or without Bundle Adjustment and fine-tuning). The metrics used are Absolute Relative Error (Abs Rel), percentage of points with depth error less than a given threshold (δ < 1.25, δ < 1.25², δ < 1.25³), and camera pose errors (ATE, RPETrans, RPERot). The table also includes the inference time.

This table presents a comparison of the TRACKSTO4D model’s performance against several baseline methods on a pet video dataset. The top section shows results from existing methods for structure and/or camera estimation. The bottom section details the TRACKSTO4D results under different configurations (training only on cats, dogs, or both; with or without bundle adjustment post-processing; and with or without fine-tuning). Metrics include absolute relative error, delta thresholds, average translational error, and reprojection error.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed TRACKSTO4D method against several baseline methods for 3D structure and camera pose estimation on a dataset of casual pet videos. The top section shows results from baseline methods, while the bottom section details the performance of TRACKSTO4D under various configurations (training only on cats, dogs, or both; with and without bundle adjustment and fine-tuning). The metrics used for comparison include Absolute Relative error, percentage of points with depth error less than a certain threshold (δ < 1.25, δ < 1.25^2, δ < 1.25^3), and others.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed TRACKSTO4D method against several baseline methods for 3D structure and camera pose estimation. The top section shows results from existing methods. The bottom section shows results for TRACKSTO4D under various configurations, indicating whether training data included cats, dogs, or both; whether Bundle Adjustment (BA) or fine-tuning (FT) post-processing was applied. Metrics include Absolute Relative error (Abs Rel), percentage of points with less than a certain depth error (δ), Average Translation Error (ATE), and Relative Pose Errors (RPE). Lower values for Abs Rel and ATE are better, while higher values for δ are better.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for 3D structure and camera pose estimation using casual pet videos. The top section shows baseline methods’ performance metrics, while the bottom section displays the proposed TRACKSTO4D method’s performance under various configurations (training on cats only, dogs only, or both; with or without bundle adjustment; and with or without fine-tuning). Metrics include Absolute Relative error (Abs Rel), percentage of points with depth error less than 1.25, 2.5, and 3 times the ground truth depth (δ<1.25, δ<2.5, δ<3), Average Translation Error (ATE), Relative Pose Error Translation (RPETrans), and Relative Pose Error Rotation (RPERot). Inference Time is also reported.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed TRACKSTO4D model against several baseline methods for 3D structure and camera pose estimation using casual videos of cats and dogs. The top section shows baseline results, while the bottom section presents results for TRACKSTO4D under various configurations, including training on cats only, dogs only, or both, and with or without post-processing steps such as bundle adjustment (BA) and fine-tuning (FT). Metrics include Absolute Relative error, percentage of points with depth error less than 1.25, ATE, and RPE.

This table presents the quantitative results of the TRACKSTO4D model on videos from the Nvidia Dynamic Scenes Dataset [62], which are outside the training data distribution (out-of-domain). The metrics used are identical to those in Table 1 (Abs Rel, δ<1.25, ATE, RPETrans, RPERot, Time). The table shows how well the model generalizes to unseen video categories.

This table presents the quantitative results of TRACKSTO4D on videos from the Nvidia Dynamic Scenes Dataset [62], which contains dynamic scenes with various motion profiles and object types. The results demonstrate the generalization capability of TRACKSTO4D to unseen data, comparing metrics (Absolute Relative error, etc.) against baseline methods. The structure of this table is identical to Table 1.

Full paper#