↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many existing computational models of decision confidence are limited to specific scenarios, such as comparing choices with identical values. This restricts their applicability to various real-world tasks. Moreover, most experiments in value-based decision-making focus solely on value and neglect the role of perceptual uncertainty. This paper introduces a new normative framework for modeling decision confidence that addresses these issues.

The proposed framework models decision confidence as the probability of making the best decision and is generalizable to various tasks and experimental setups. It maps to the planning-as-inference framework, where the objective function is maximizing gained reward and information entropy. This model’s efficacy was validated on two different psychophysics experiments and shows superiority to existing methods in explaining subjects’ confidence reports.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on decision-making and confidence modeling due to its novel normative framework that unifies existing models. It addresses the limitations of previous approaches by incorporating reward, prior knowledge, and uncertainty, opening new avenues for research in this critical area. The superior performance of the model compared to existing methods across multiple experiments makes it a highly valuable contribution.

Visual Insights#

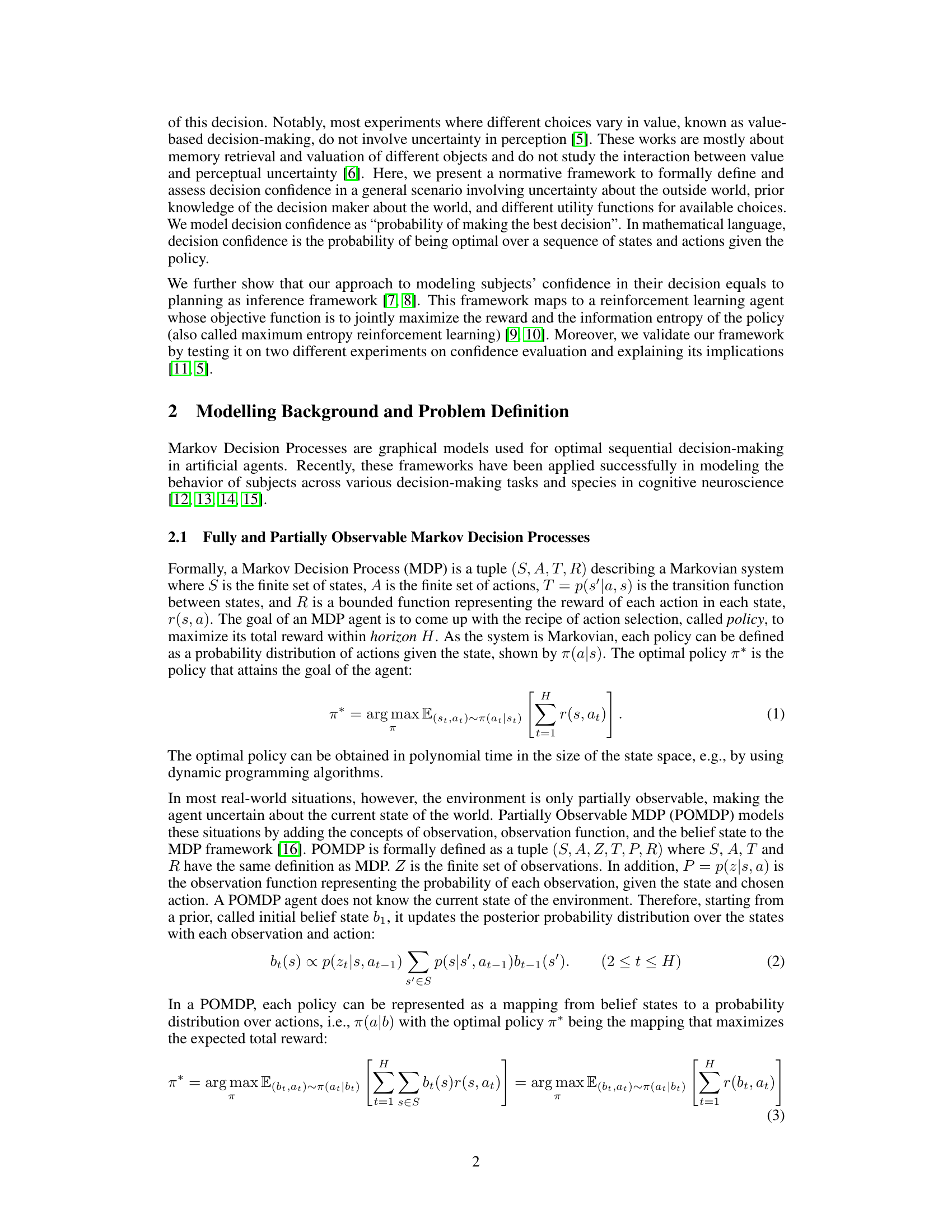

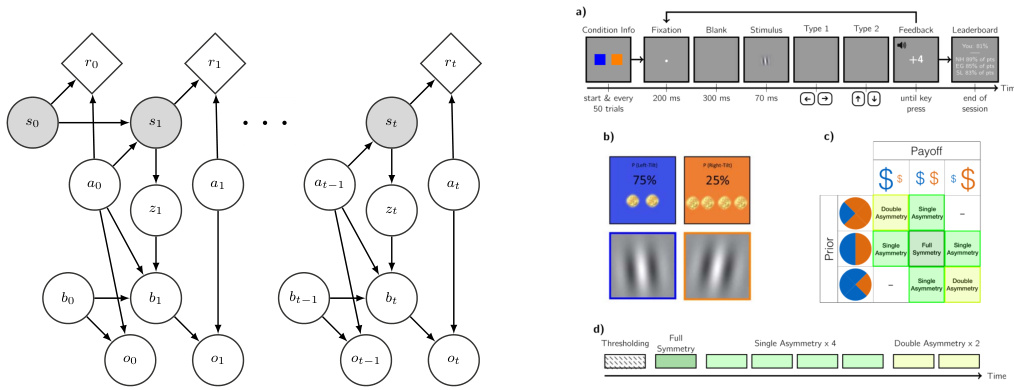

The figure is composed of two parts. The left part shows a graphical model illustrating the framework used to measure the probability of making an optimal decision, which is considered as the decision confidence. The model involves nodes representing states, actions, observations, and the optimality of the decision at each time step. The right part displays the experimental setup of a perceptual decision-making task, which is the empirical validation of the model. The setup includes stimulus presentation, feedback, and a leaderboard. The stimuli have varying prior probabilities and reward distributions to test the model’s generalization ability.

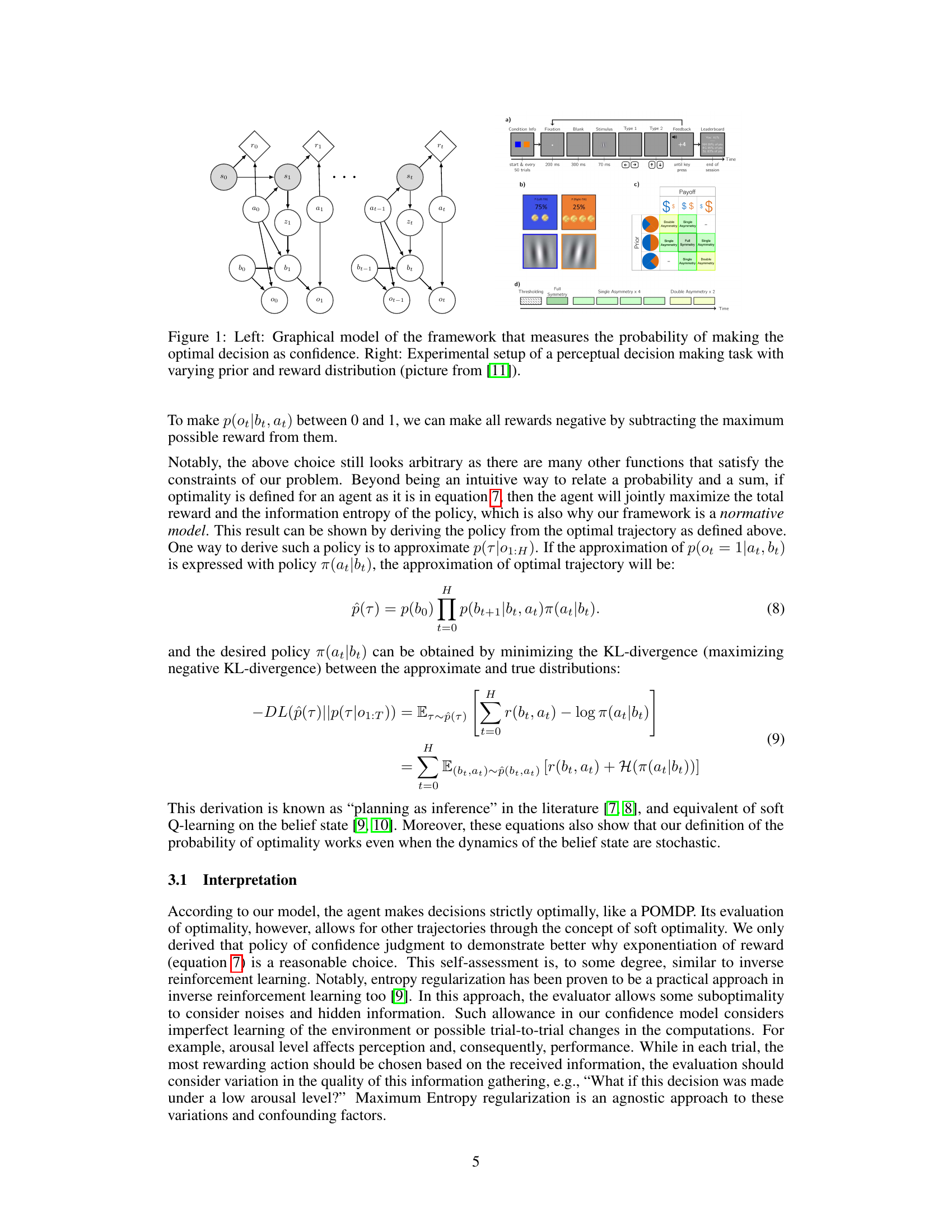

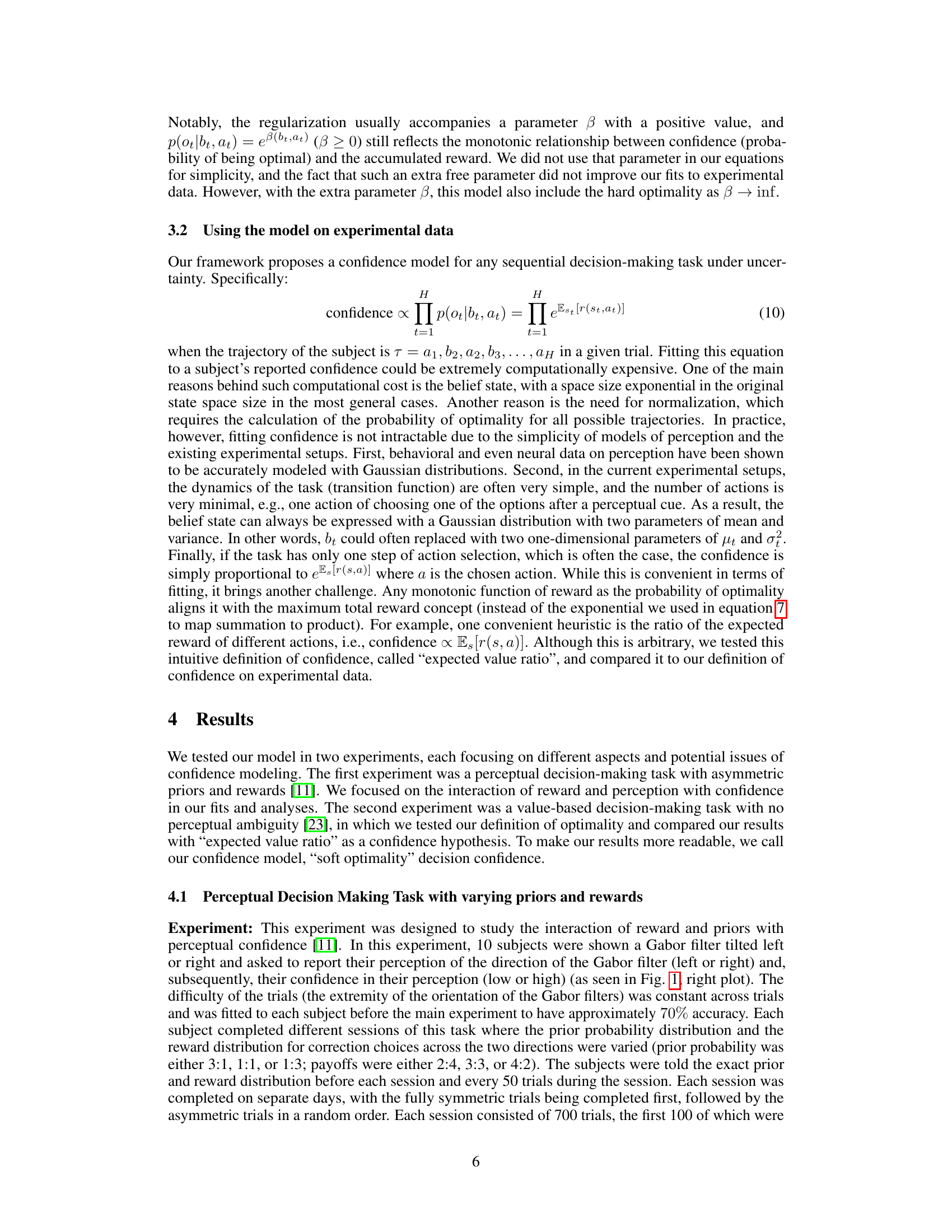

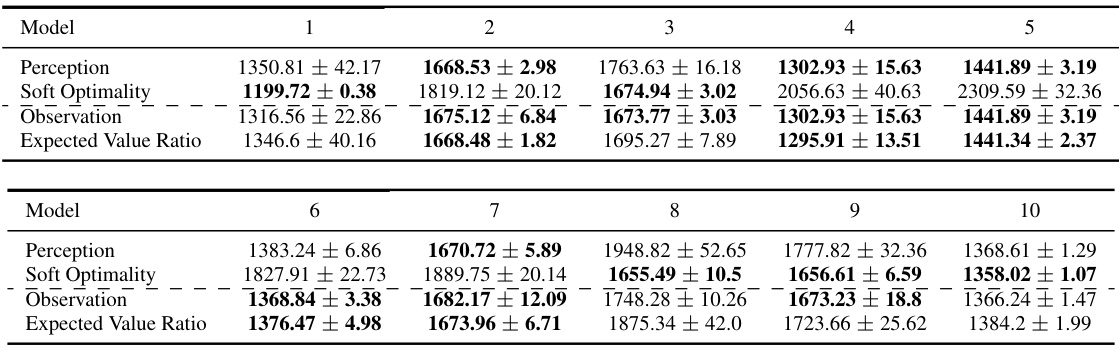

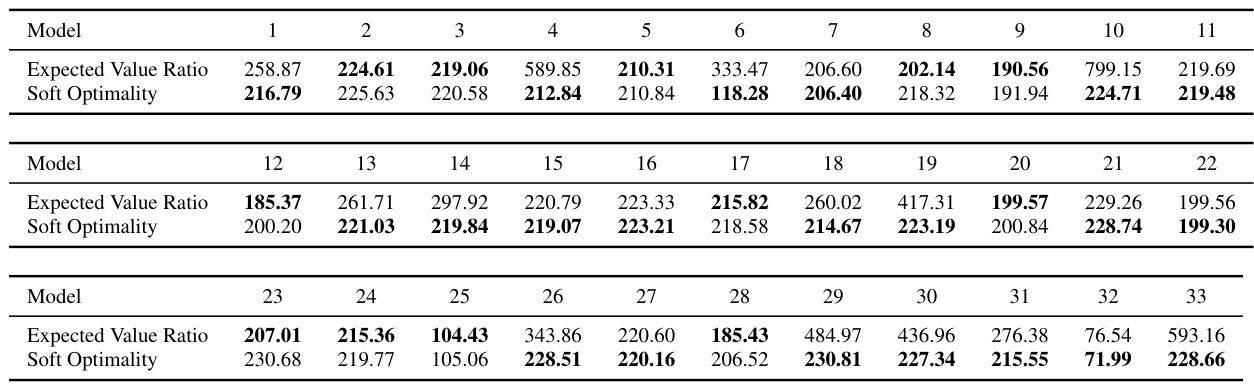

This table presents the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values for different confidence models fitted to data from a perceptual decision-making task. Lower AIC values indicate a better fit to the data. The models compared include ‘Perception’, ‘Soft Optimality’, ‘Observation’, and ‘Expected Value Ratio’. The table is organized by model and shows the AIC values for ten different subjects (columns 1-10). The table helps to quantitatively assess which confidence model best explains the participants’ confidence judgments in the context of a perceptual decision-making task.

In-depth insights#

Confidence Models#

The concept of ‘Confidence Models’ in the context of decision-making is multifaceted. Bayesian models, a common approach, assume the subject acts rationally, with confidence reflecting the probability of a correct choice. However, these models often fail to account for the influence of reward and prior knowledge on confidence judgments. The paper introduces a normative framework that addresses these limitations, integrating aspects of planning as inference and maximum entropy reinforcement learning. This framework views decision confidence as the probability of making the optimal choice within a partially observable environment, providing a more comprehensive and realistic model than previous methods. The model’s superiority is demonstrated empirically, outperforming alternative models in explaining subjects’ confidence reports across experiments with varying reward structures and perceptual uncertainty. The study highlights the shortcomings of simpler models that neglect the interplay between value, perception, and confidence and advocates for the utility of this enhanced, generalized framework.

POMDP Framework#

The paper leverages the Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) framework to model decision-making under uncertainty, a significant departure from existing confidence models limited to scenarios with equal choice values. POMDP’s strength lies in its ability to incorporate both perceptual uncertainty and reward variability into the decision-making process. This allows for a more realistic representation of real-world scenarios where choices have different potential outcomes and an agent’s beliefs about the world are constantly evolving. The framework elegantly connects decision confidence to the probability of an optimal trajectory, thus providing a normative foundation for understanding subjects’ confidence reports. This contrasts with descriptive models that lack explanatory power. The model’s key innovation is formally incorporating reward value into the confidence calculation, leading to a more nuanced perspective. The inclusion of planning as inference further strengthens the model’s theoretical grounding, providing a coherent mechanism for linking planning, information gathering, and confidence. This results in superior performance compared to existing approaches in explaining experimental data across diverse decision-making tasks.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper would rigorously test the proposed model or framework. It would involve multiple experiments using diverse datasets, comparing the model’s performance against existing approaches with clear statistical measures to support the claims. The methodology section would be meticulously detailed, allowing for replication. Importantly, the authors would address potential limitations and biases, demonstrating robustness and generalizability. The results would be presented transparently, including any deviations from expectations, showcasing the model’s strengths and weaknesses. Ultimately, a strong empirical validation provides convincing evidence supporting the paper’s core findings.

Model Limitations#

A crucial aspect often overlooked in research is a thorough analysis of model limitations. Addressing limitations directly enhances the credibility and value of the research. In this case, it would be important to explore the model’s assumptions, such as the optimality assumption of decision-making. Real-world decisions are rarely perfectly optimal, and the model’s reliance on this assumption might limit its generalizability. Another limitation could be the complexity of the model in real-world applications, especially with high-dimensional belief states and many actions. Furthermore, there should be discussion regarding the impact of the choice of reward function, or the model’s dependence on accurate perception. Sensitivity analysis and robustness checks should be used to determine how variations in assumptions impact the outcome. Finally, the model’s performance on diverse datasets and tasks needs to be assessed to evaluate its generalizability beyond the specific scenarios it was tested on. A frank acknowledgement of limitations strengthens the study, paving the way for future improvements and more realistic applications.

Future Directions#

The research paper’s ‘Future Directions’ section could explore extending the model to handle more complex scenarios. Sequential decision-making, involving multiple actions and decisions over time, presents a significant challenge. The current model’s reliance on simplified scenarios limits its applicability to real-world situations. Another crucial area is handling multiple choices. Current experiments focus on binary choices, limiting generalizability. Addressing these limitations would enhance the model’s practical value. Furthermore, the model could be refined by incorporating individual differences, acknowledging the variability in human decision-making and confidence judgments. The current assumption of a homogenous population limits the model’s predictive power. Finally, exploring the societal implications of confidence modeling is essential. Investigating how improved understanding can address societal inequalities and biases would contribute significantly to broader impact.

More visual insights#

More on tables

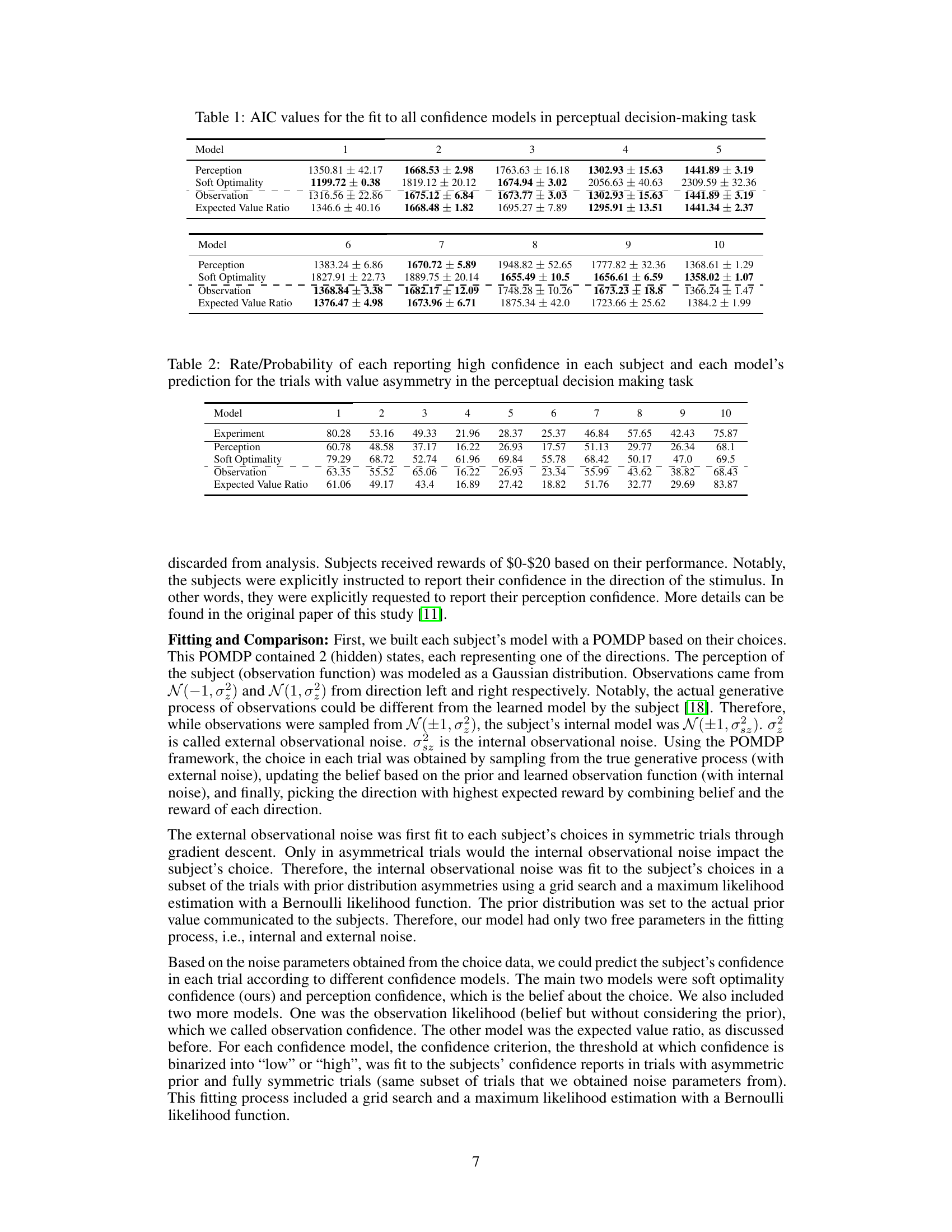

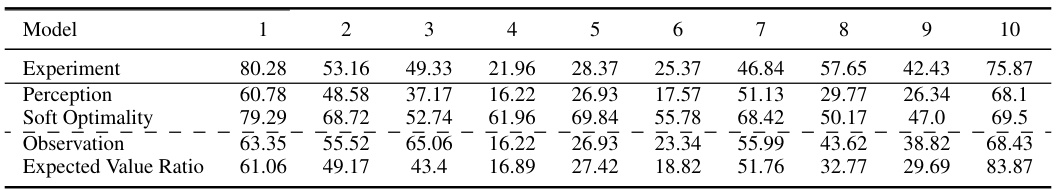

This table presents the rate or probability of each subject reporting high confidence for trials with value asymmetry in a perceptual decision-making task. It compares the experimental results to predictions from four different confidence models: Perception, Soft Optimality, Observation, and Expected Value Ratio. Each model’s accuracy in predicting high-confidence reports is shown for each subject.

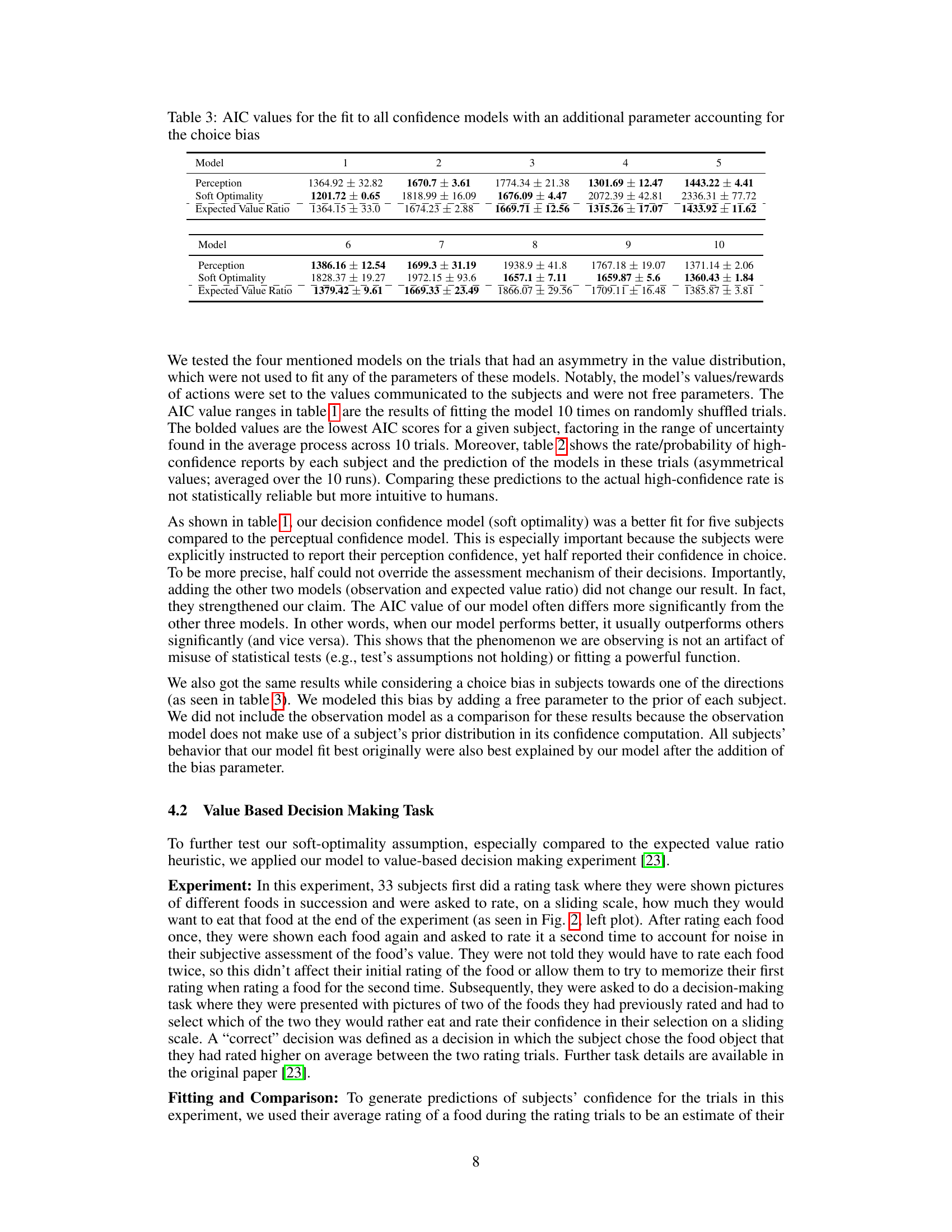

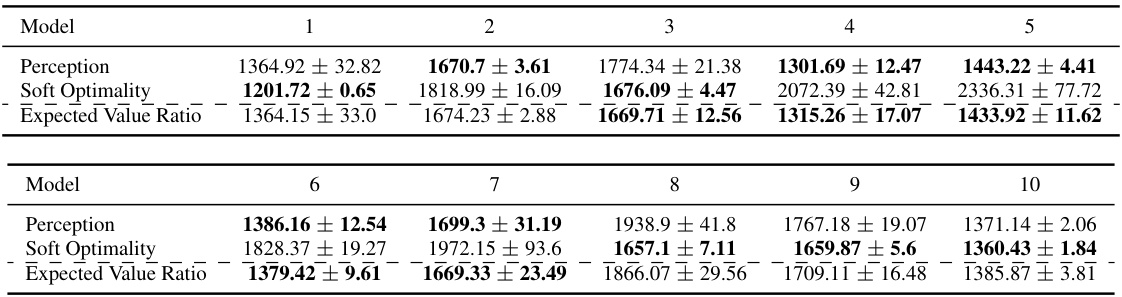

This table shows the AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) values for different confidence models, including the soft optimality model proposed in the paper, after adding a parameter to account for bias in subject choices. Lower AIC values indicate a better fit to the data. The table compares the performance of several models in predicting subjects’ confidence judgments. The models include a perception-based model, soft optimality model, and expected value ratio model. The addition of the bias parameter aims to improve the models’ ability to capture the observed data by accommodating individual differences in decision-making tendencies.

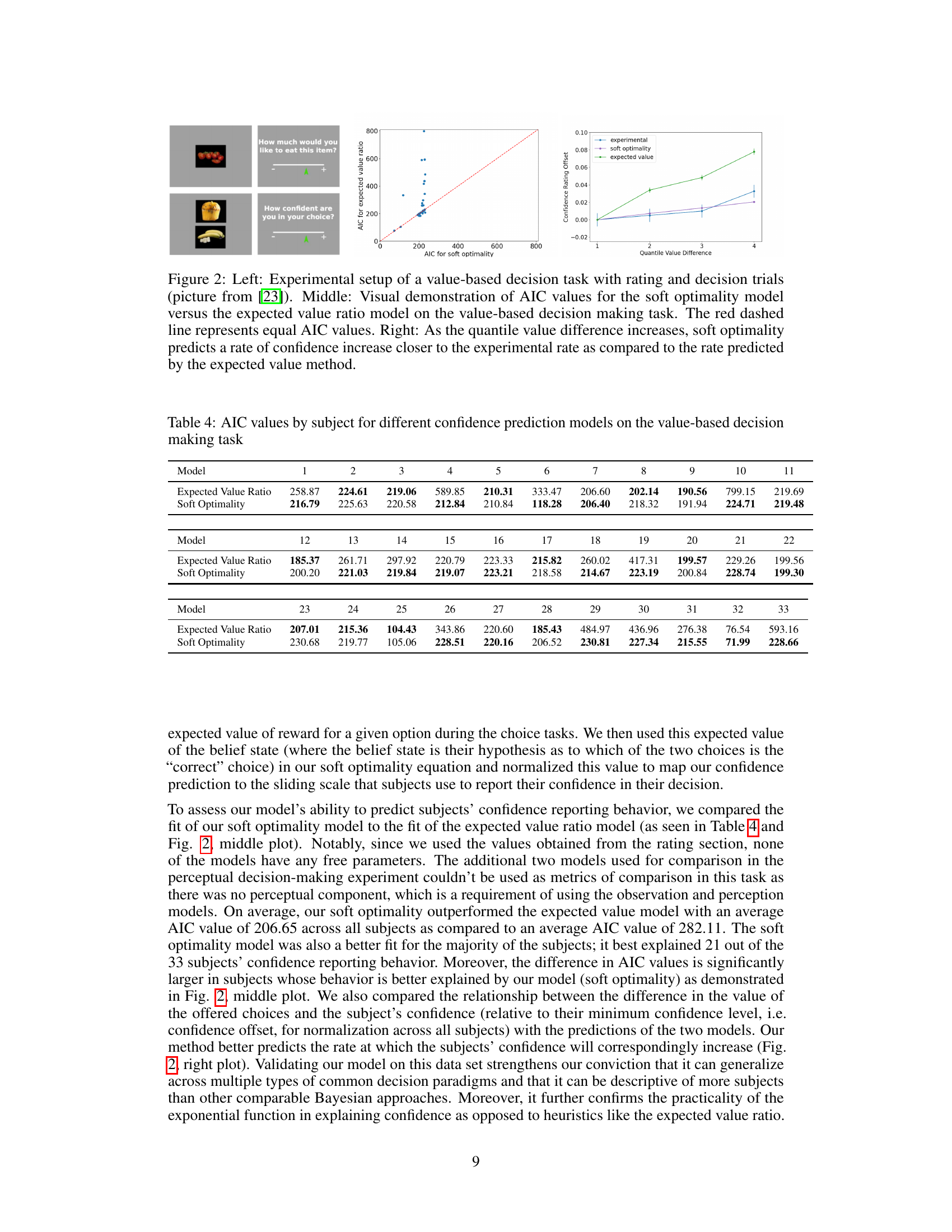

This table presents the AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) values for each subject in the value-based decision-making task. AIC values are shown for two different confidence prediction models: the expected value ratio model and the soft optimality model. Lower AIC values indicate a better fit to the data. The table allows for a comparison of the model fits across individual subjects, providing insights into which model better explains the subjects’ confidence judgments in this specific task.

Full paper#