TL;DR#

Fairness in clustering is often treated as a constraint, neglecting the crucial trade-off with clustering quality. Existing methods usually focus on finding a single optimal point, overlooking the broader landscape of possible solutions. This paper presents an innovative approach to this problem.

The proposed algorithms trace the entire Pareto front – illustrating all optimal trade-offs between quality and fairness. These algorithms handle diverse fairness and quality metrics. While exponential time is unavoidable for general cases, a polynomial-time algorithm is provided for a specific fairness measure. Extensive experimental results on real-world data demonstrate the practical applicability of the approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the critical trade-off between fairness and quality in clustering, a prevalent issue in various applications. By providing algorithms to trace the complete Pareto front, it empowers researchers and practitioners to make informed decisions balancing both objectives. This opens avenues for further research into more sophisticated fairness criteria and algorithms.

Visual Insights#

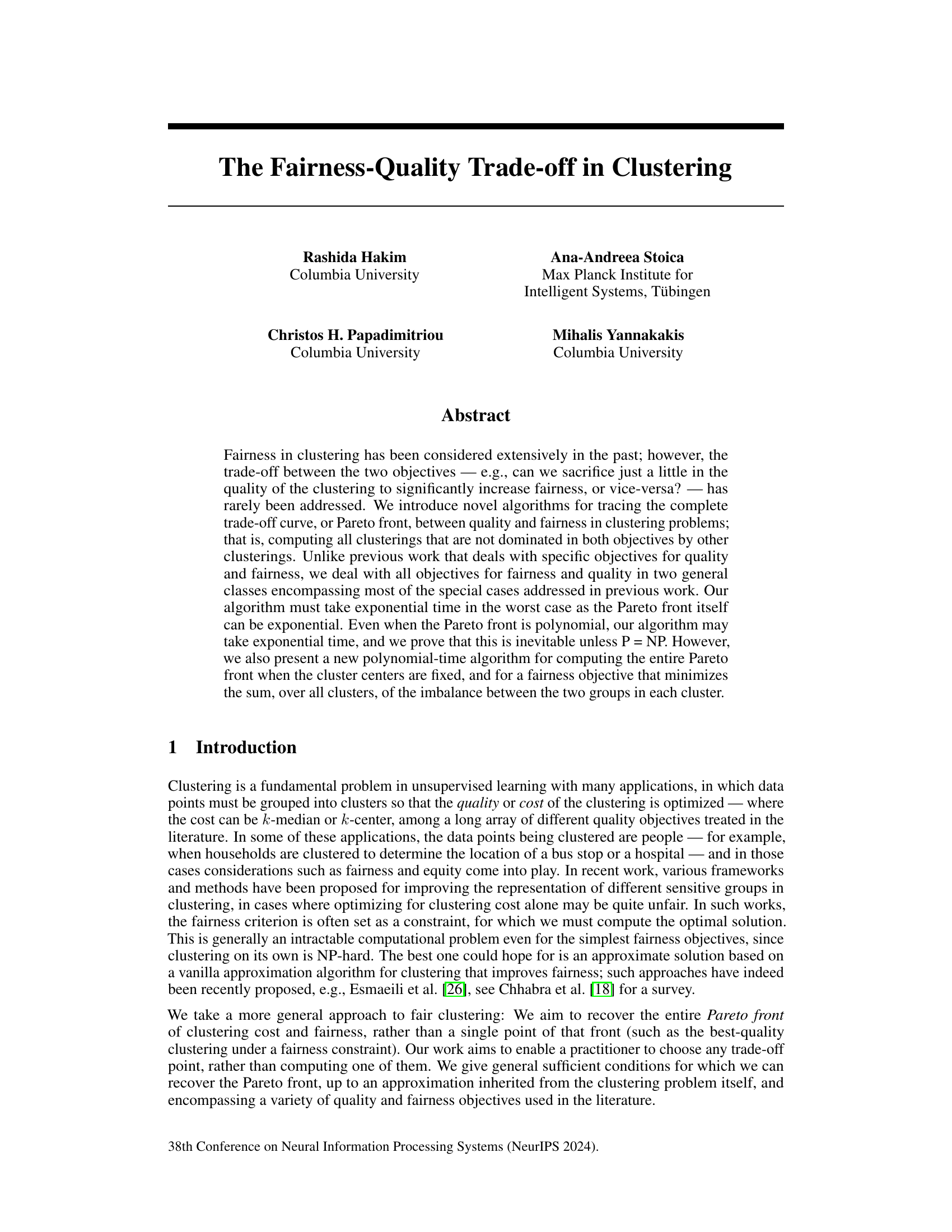

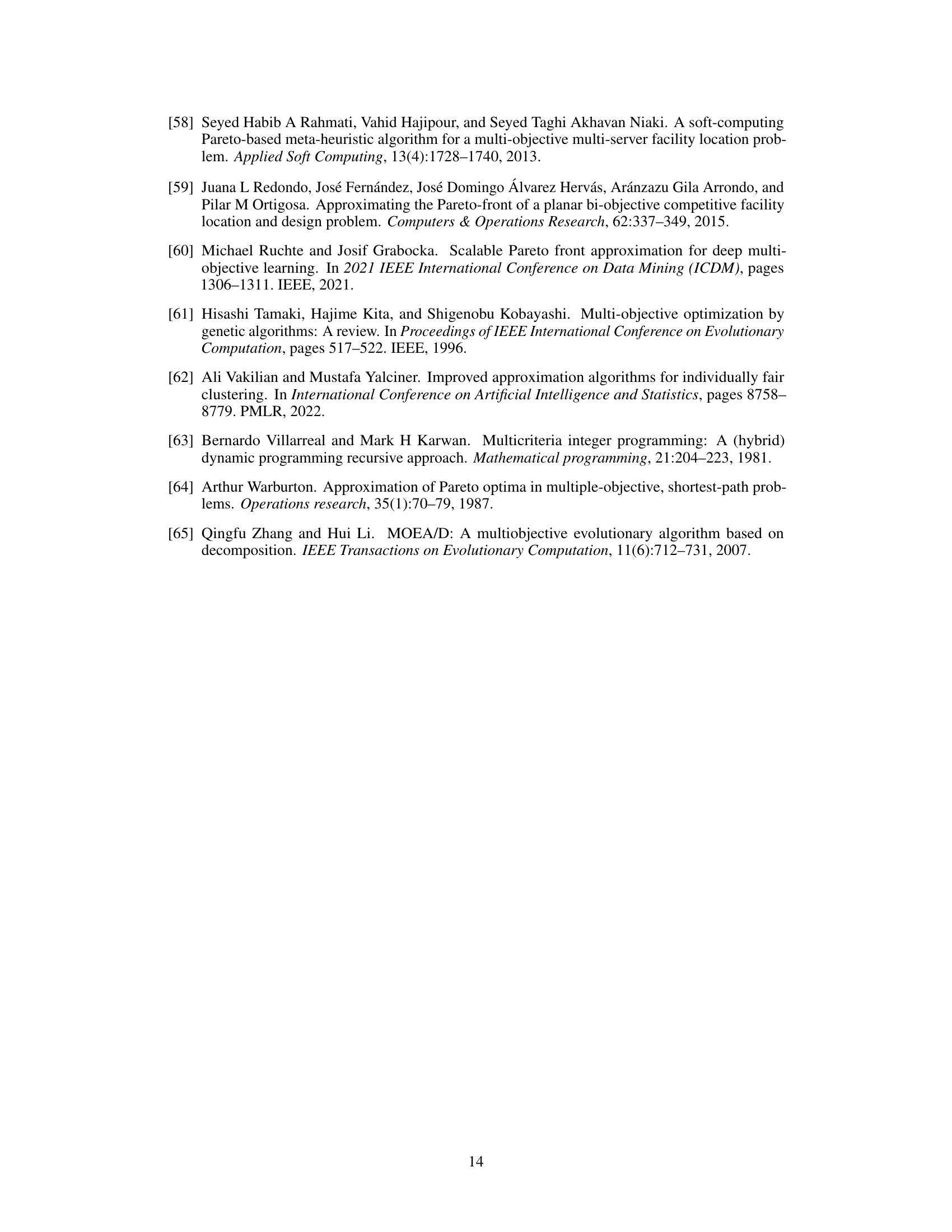

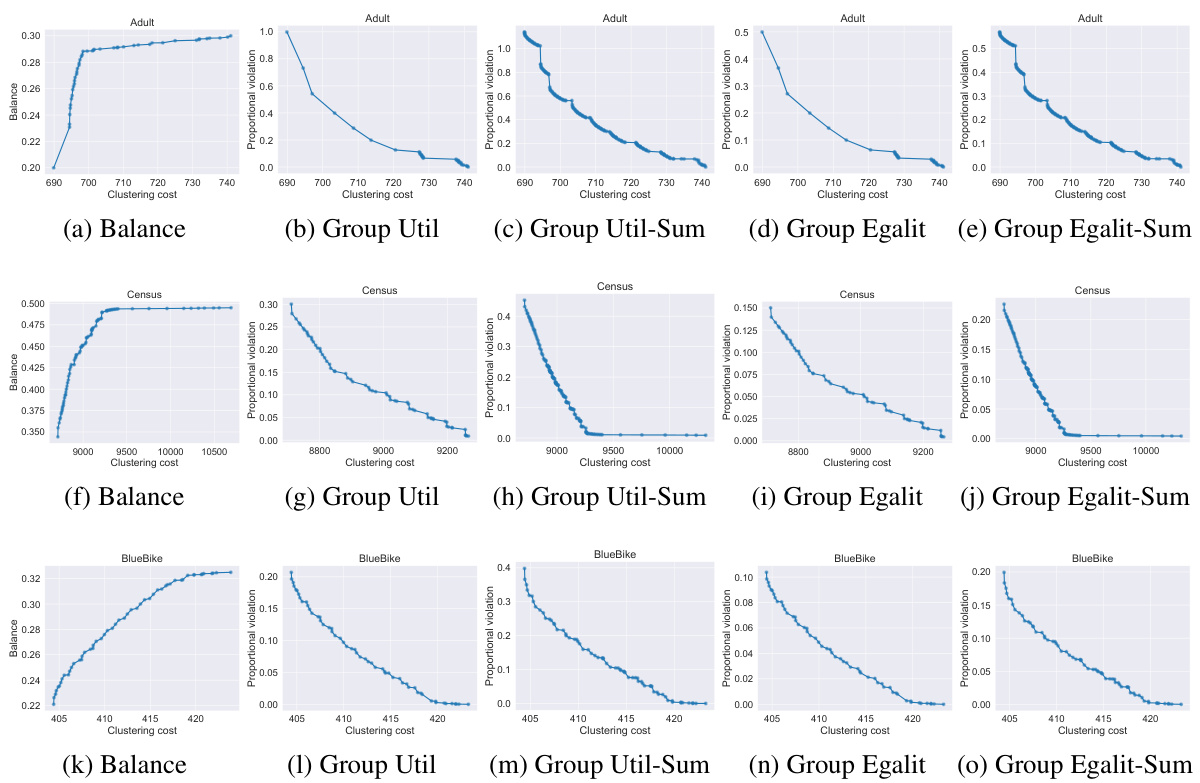

🔼 This figure presents the Pareto front for clustering on three real-world datasets (Adult, Census, BlueBike) using Algorithm 1. Each row represents a dataset, and each column represents a different fairness objective (Balance, Group Util, Group Util-Sum, Group Egalit, Group Egalit-Sum). The Pareto front illustrates the trade-off between clustering quality (cost) and fairness. For each dataset and fairness objective, the curve shows all the non-dominated clustering solutions; solutions on the curve represent a balance between cost and fairness, where any improvement in one metric necessitates a compromise in the other. The different shapes of the curves reflect the varying relationships between cost and fairness across the different datasets and fairness measures.

read the caption

Figure 1: Pareto front recovered by Algorithm 1 for the Adult, Census, and BlueBike datasets (by row), for various fairness objectives (by column), for k = 2 clusters.

🔼 This table presents the number of features and sensitive attributes used for each dataset (Adult, Census1990, BlueBike) along with the delta (δ) value used in the proportional violation objectives. Delta represents a deviation from the true group proportions.

read the caption

Table 1: Data and experimental details.

In-depth insights#

Fairness-Quality Tradeoffs#

The concept of Fairness-Quality Tradeoffs in clustering algorithms explores the inherent tension between achieving high-quality clusterings (e.g., minimizing within-cluster variance) and ensuring fairness across different groups within the data. Fairness often involves mitigating biases that might lead to disproportionate representation of certain groups in specific clusters. A common approach is to define a fairness metric that quantifies the level of imbalance across groups in each cluster, which can be balanced against a quality metric. The Pareto front represents all non-dominated solutions, revealing the possible tradeoffs. Algorithms that trace the entire Pareto front are crucial for allowing practitioners to select a solution that balances their desired level of fairness and clustering quality. Computational complexity is a significant hurdle, as finding the entire Pareto front is often computationally expensive. However, research has advanced efficient algorithms (such as dynamic programming approaches) for specific cases or well-defined fairness measures. Approximation algorithms are also investigated where an exact solution is too complex. Ultimately, understanding the Fairness-Quality Tradeoff is essential for responsible use of clustering techniques, particularly in sensitive applications like resource allocation or decision-making processes where bias could lead to adverse consequences.

Pareto Front Tracing#

Pareto front tracing in the context of fair clustering presents a powerful approach to navigate the trade-off between clustering quality and fairness. Instead of seeking a single optimal solution that might be suboptimal in one aspect, this method aims to identify the entire set of non-dominated solutions (the Pareto front). Each point on this front represents a different balance between quality and fairness, allowing decision-makers to choose the solution that best aligns with their priorities. The algorithms employed for Pareto front tracing are computationally complex because the Pareto front itself can grow exponentially with the number of data points and attributes. Therefore, research often focuses on finding approximations of the Pareto front or developing polynomial-time algorithms for specific fairness objectives. The complexity is inherent in the nature of multi-objective optimization problems and is frequently encountered in other fields as well. Despite this inherent complexity, the benefit of Pareto front tracing in fair clustering is undeniable; it empowers practitioners with crucial information for informed decision-making in settings where fairness and quality are both important considerations.

Algorithmic Approaches#

The research paper explores algorithmic approaches to navigate the fairness-quality trade-off in clustering. A dynamic programming algorithm is presented for the assignment problem, where cluster centers are pre-defined, providing an exact solution. This approach is extended to approximate the Pareto front for the more challenging clustering problem, where centers are also optimized. The algorithm’s time complexity is analyzed, highlighting exponential time complexity in the worst case, proven to be unavoidable unless P=NP. Despite this, a novel polynomial-time algorithm is introduced for a specific fairness objective minimizing cluster imbalances, showcasing a case where efficient computation is achievable. The paper also investigates faster approximation methods, acknowledging the trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency. Empirical evaluations demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithms, analyzing Pareto fronts on real-world datasets and different fairness objectives, comparing them to existing approaches in terms of accuracy and running time. This provides a valuable contribution to the field of fair clustering, enabling a deeper understanding of how to balance fairness and clustering quality.

Empirical Evaluation#

An empirical evaluation section of a research paper would ideally present a robust and comprehensive assessment of the proposed method. It should begin by clearly defining the metrics used to evaluate performance, justifying their selection based on relevance to the research questions. A diverse range of datasets should be utilized to demonstrate the generalizability of the method, including a description of the characteristics of each dataset and the rationale for their inclusion. The results should be presented transparently, including visualizations (charts, tables, etc.) to aid interpretation. Statistical significance testing is crucial to validate the observed performance differences; and error bars or confidence intervals should accompany the results to reflect uncertainty. The evaluation should not only compare the new method to existing state-of-the-art techniques but also analyze the method’s behavior under various conditions (e.g., different parameter settings or data distributions) and potential limitations. A discussion interpreting the results, linking them back to the research hypotheses, and highlighting both strengths and limitations, is also a key component of a strong empirical evaluation section. The overall goal is to present compelling evidence supporting the method’s effectiveness and its limitations within the broader field of research.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending these fairness-aware clustering algorithms to handle a wider array of fairness metrics beyond those considered here, including individual fairness notions. Investigating the impact of different data characteristics, such as imbalanced class distributions or high-dimensionality, on the performance and efficiency of these algorithms is crucial. Developing more sophisticated methods for approximating the Pareto front efficiently for large datasets would significantly improve scalability. Incorporating uncertainty or noise in the data into the model, thus evaluating robustness, is another important area. Finally, applying these algorithms to new application domains, such as resource allocation problems or social network analysis, presents exciting avenues for future research and practical impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the Pareto fronts obtained for three real-world datasets (Adult, Census, and BlueBike) using Algorithm 1. Each row represents a dataset, and each column represents a different fairness objective (Balance, Group Utilitarian, Group Utilitarian-Sum, Group Egalitarian, Group Egalitarian-Sum). The Pareto front illustrates the trade-off between clustering cost and fairness for each dataset and fairness objective. The x-axis shows the clustering cost and the y-axis shows the fairness metric for each corresponding objective. The algorithm finds the exact Pareto front for the assignment problem (centers are fixed), which provides an approximation for the Pareto front of the clustering problem (centers are not fixed).

read the caption

Figure 1: Pareto front recovered by Algorithm 1 for the Adult, Census, and BlueBike datasets (by row), for various fairness objectives (by column), for k = 2 clusters.

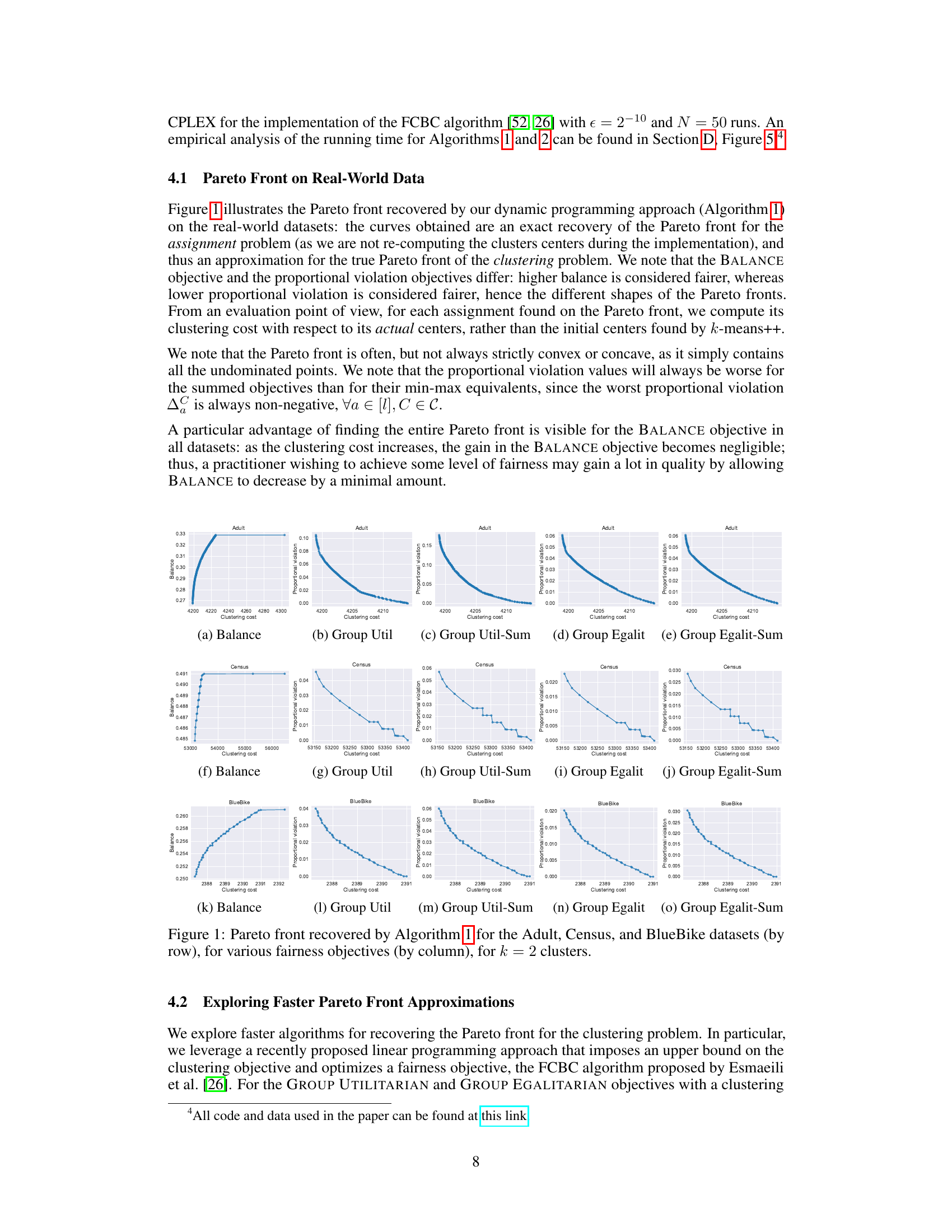

🔼 Figure 3 demonstrates examples of clustering scenarios that violate the pattern-based and mergeable properties for fairness objectives. Subfigure (a) illustrates a clustering where the fairness depends on the relative location of points and the cluster centers, not just the number of points of each attribute. Subfigure (b) shows how a non-mergeable objective leads to non-optimality when clusters are merged. These examples highlight the limitations of algorithms designed for pattern-based and mergeable objectives when applied to scenarios that do not satisfy these properties.

read the caption

Figure 3: (a) An illustration of clustering under for non-pattern based fairness objectives. (b) An illustration of the (Pi)i∈[8] sets for non-mergeable fairness objectives.

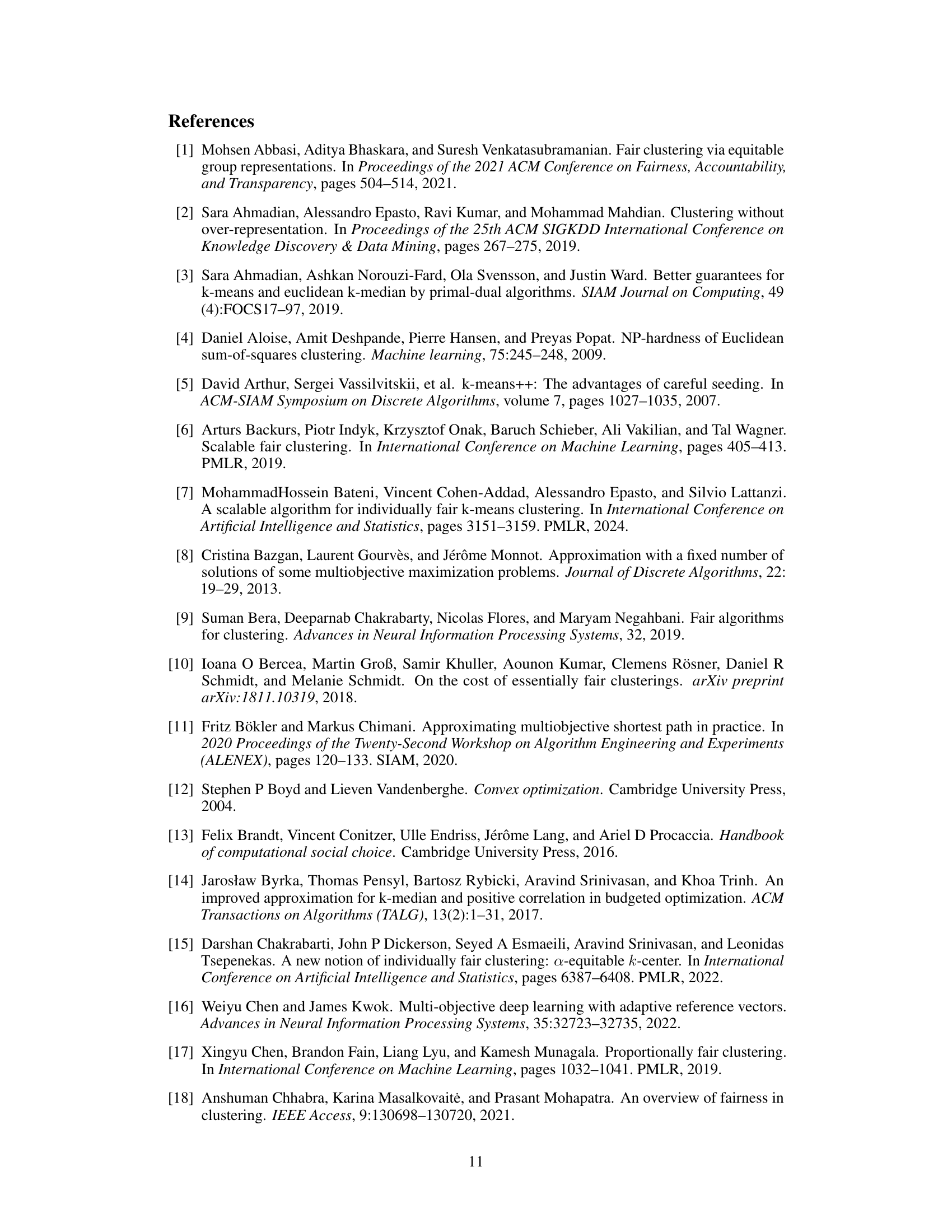

🔼 This figure illustrates the repeated FCBC algorithm for approximating the Pareto front. The algorithm sweeps across different upper bounds (U) on the clustering cost, generating a set of approximate Pareto points. Each point represents the result of the FCBC algorithm for a given clustering cost bound. The dashed line represents a sweep across different upper bound values, and the points show the resulting fairness and clustering objective values for each bound. The algorithm effectively traces out an approximation of the Pareto frontier.

read the caption

Figure 4: An illustration of implementing the repeated FCBC algorithm as the clustering cost upper bound U varies.

🔼 This figure compares the running times of two algorithms for computing the Pareto front for fair clustering problems. The dynamic programming approach (Dyn Progr) is shown to be more efficient for larger datasets. The repeated FCBC approach, while faster for small datasets, becomes increasingly slower as dataset size increases.

read the caption

Figure 5: Running time comparison with our dynamic programming approach from Algorithm 1, labeled as ‘Dyn Progr’, and the repeated FCBC approach from Algorithm 2, labeled as ‘FCBC’, for each dataset (by column) and for the GROUP UTILITARIAN and GROUP EGALITARIAN objective (by row).

🔼 This figure displays the Pareto fronts obtained by applying Algorithm 1 (dynamic programming approach) to three real-world datasets (Adult, Census, and BlueBike). Each row represents a dataset, and each column represents a different fairness objective (Balance, Group Util, Group Util-Sum, Group Egalit, Group Egalit-Sum). The x-axis shows the clustering cost, and the y-axis shows the fairness value for each objective. Each curve represents the Pareto front, which shows the trade-off between clustering quality and fairness for that specific dataset and fairness objective.

read the caption

Figure 1: Pareto front recovered by Algorithm 1 for the Adult, Census, and BlueBike datasets (by row), for various fairness objectives (by column), for k = 2 clusters.

🔼 This figure displays the Pareto fronts obtained by applying Algorithm 1 (dynamic programming) to three real-world datasets: Adult, Census, and BlueBike. Each row represents a different dataset, and each column represents a different fairness objective (Balance, Group Utilitarian, Group Utilitarian-Sum, Group Egalitarian, and Group Egalitarian-Sum). The Pareto front illustrates the trade-off between clustering cost and fairness for each dataset and objective. Each point on the curve represents a clustering solution that is not dominated by any other solution in terms of both cost and fairness; that is, no other solution has both lower cost and higher fairness. The shapes of the Pareto fronts vary across datasets and objectives, reflecting the different balances between cost and fairness achievable in different situations. For example, in the BALANCE objective, the improvement in fairness as clustering cost increases diminishes quickly, suggesting that a practitioner may find an optimal trade-off by allowing a small amount of decline in fairness for a significant improvement in quality.

read the caption

Figure 1: Pareto front recovered by Algorithm 1 for the Adult, Census, and BlueBike datasets (by row), for various fairness objectives (by column), for k = 2 clusters.

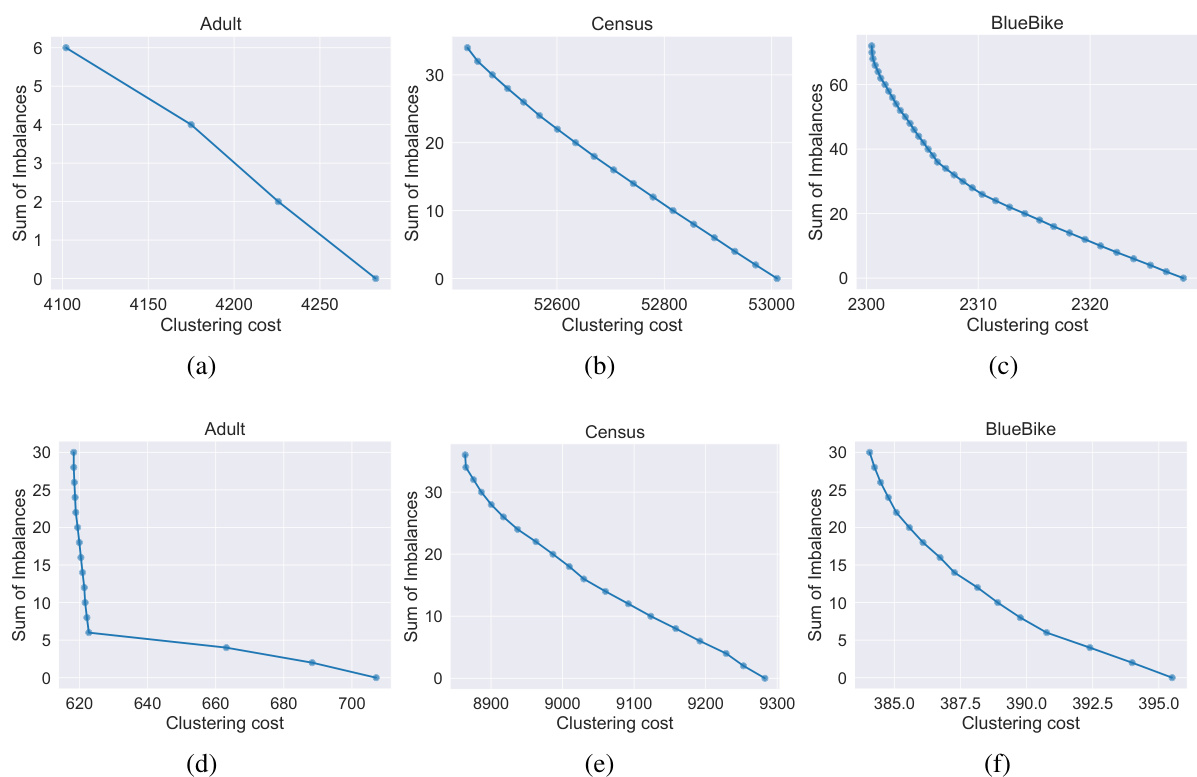

🔼 This figure shows the Pareto fronts obtained for the SUM OF IMBALANCES fairness objective for three real-world datasets: Adult, Census, and BlueBike. The Pareto fronts are shown for both k=2 and k=3 clusters. Each plot displays the trade-off between clustering cost and the sum of imbalances across clusters. The x-axis represents the clustering cost, and the y-axis represents the sum of imbalances. The plots demonstrate how the optimal trade-off between clustering cost and fairness varies depending on the dataset and the number of clusters.

read the caption

Figure 8: Pareto front recovered for the SUM OF IMBALANCES objective for the Adult, Census, and BlueBike datasets (by column), for k = 2 (top row) and k = 3 (bottom row) clusters.

Full paper#