↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep neural networks (DNNs) have been widely used to investigate biological visual representations. However, most existing DNNs are designed for static images and lack the physiological neuronal mechanisms of the visual cortex. This limits their ability to model visual processing under natural movie stimuli, which are rich in dynamic information. This paper addresses these issues by proposing a novel model to investigate how the visual cortex processes such dynamic visual information.

The proposed model is the long-range feedback spiking network (LoRaFB-SNet). It is designed to mimic top-down connections between cortical regions and incorporates spike information processing mechanisms, which is more biologically plausible. The authors introduce a new representational similarity analysis method, called TSRSA, tailored to assess the similarity of neural representations under movie stimuli. The results show that LoRaFB-SNet achieves the highest level of representational similarity compared to other leading models, especially for longer movie stimuli, indicating that it effectively captures both dynamic and static representations of the visual cortex.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel spiking neural network that effectively models the visual cortex’s dynamic and static representations under movie stimuli. This bridges the gap between traditional feedforward models and biological neural mechanisms, leading to a more accurate and biologically plausible understanding of visual processing. It also proposes a new representational similarity analysis method better suited to analyzing dynamic neural representations. This work is relevant to researchers in neuroscience, computer vision, and machine learning.

Visual Insights#

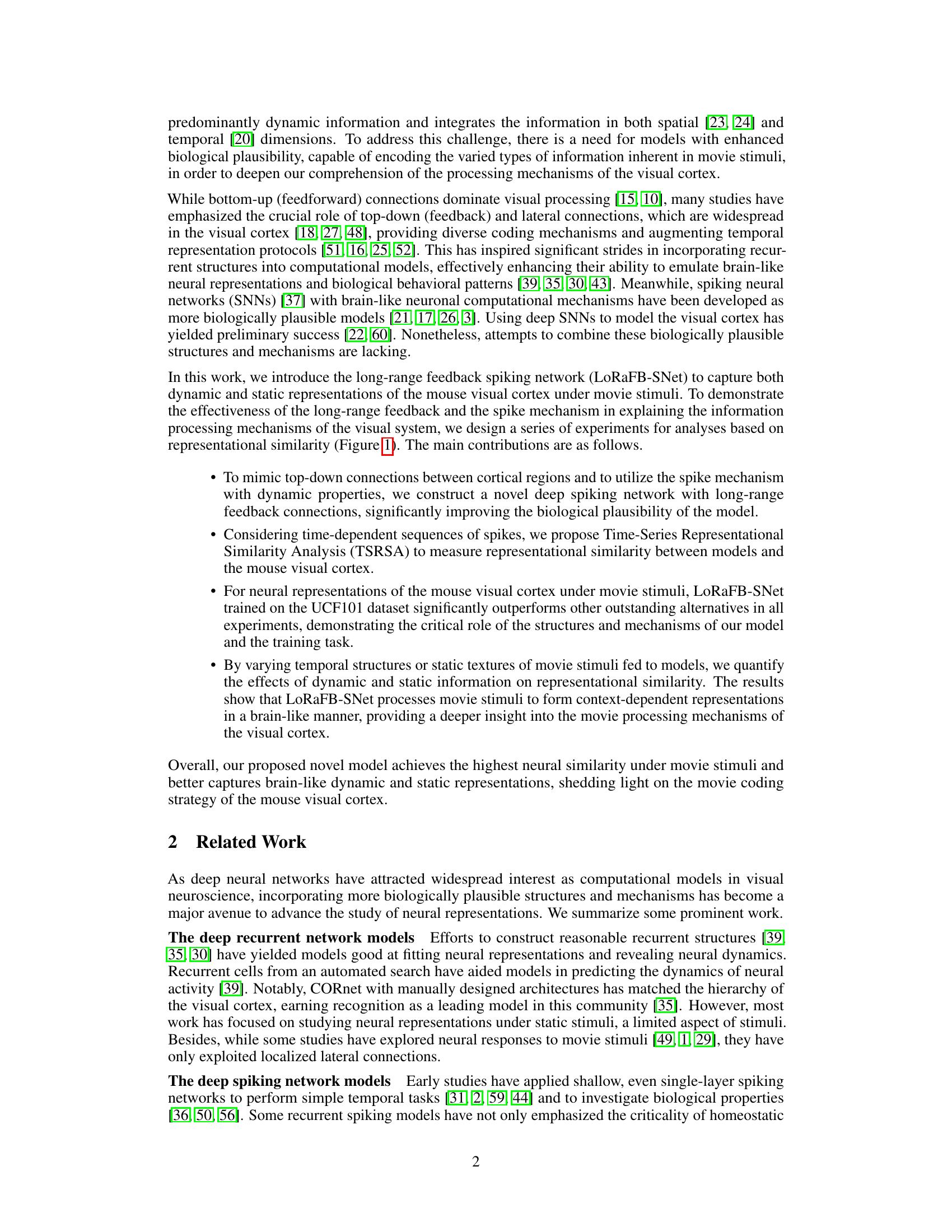

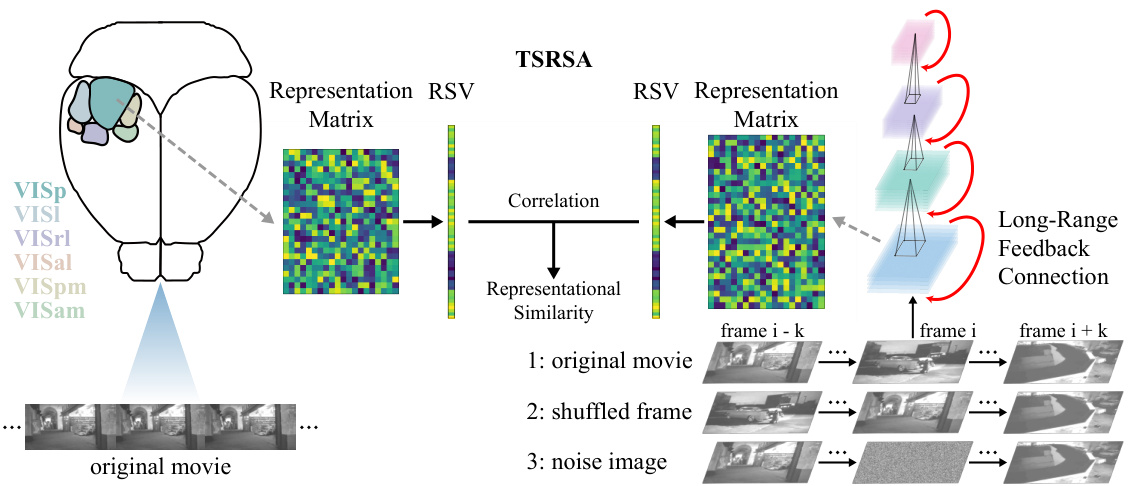

This figure illustrates the experimental setup to compare the model’s representation of movie stimuli with that of the mouse visual cortex. Six visual cortical regions are shown receiving the same movie. The long-range feedback spiking network also receives the same movie, producing its own representation. Representational Similarity Analysis (RSA) compares the model and biological representations. To isolate the effect of dynamic and static information, the network also receives modified movie versions (shuffled frames and noise images), while the biological input remains unchanged.

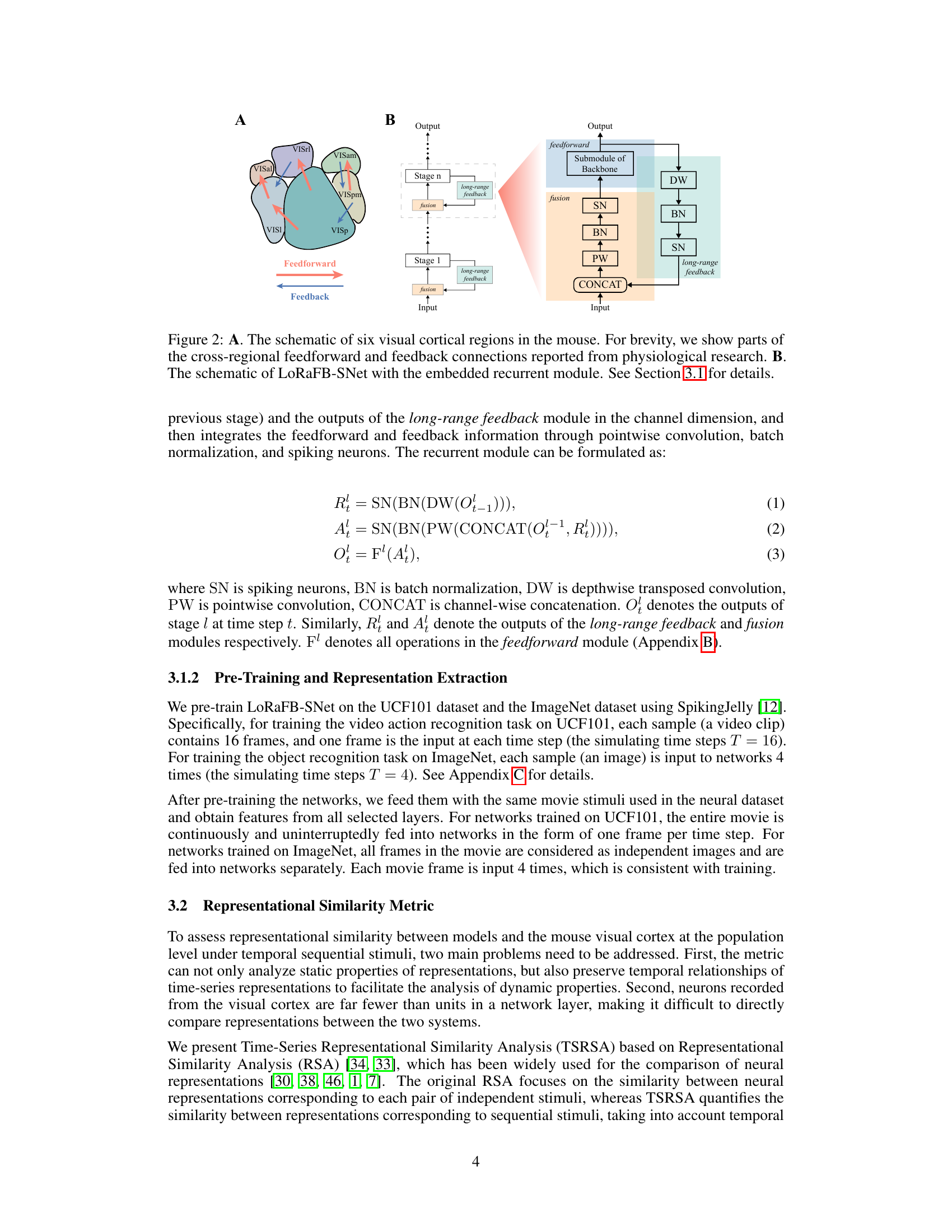

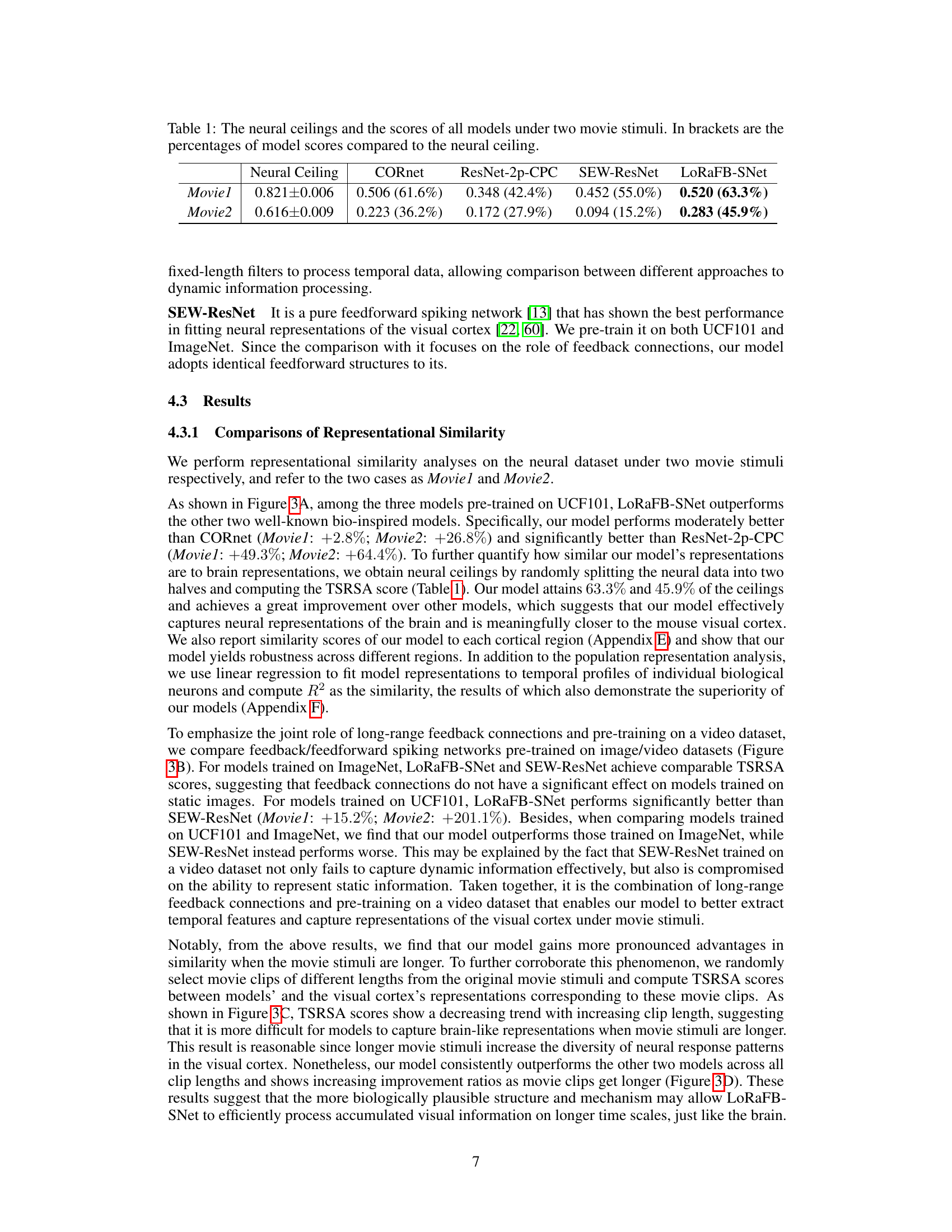

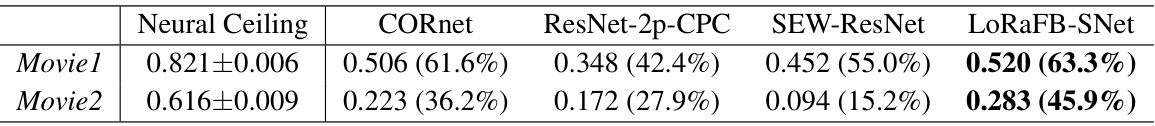

This table presents the representational similarity analysis (RSA) scores achieved by four different models (CORnet, ResNet-2p-CPC, SEW-ResNet, and LoRaFB-SNet) on two movie stimuli (Movie1 and Movie2). The ‘Neural Ceiling’ represents the upper limit of performance, based on the neural data. For each model and movie, the table shows the RSA score and, in parentheses, the percentage of the neural ceiling that the model achieved. This allows for a direct comparison of model performance relative to the biological data.

In-depth insights#

Spiking Network Design#

The design of spiking neural networks (SNNs) is crucial for their performance and biological plausibility. A key aspect is the choice of neuron model; Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) is popular due to its balance between biological accuracy and computational tractability. Network architecture significantly impacts functionality. The paper likely employs a layered architecture, potentially with convolutional layers for feature extraction and recurrent connections for temporal processing. The integration of long-range feedback connections is a notable design choice, mimicking top-down influences observed in biological visual systems and enhancing context-dependent processing. The use of depthwise transposed convolutions within the feedback pathway deserves attention; this technique reduces parameter count while increasing feature map resolution, enhancing the network’s ability to integrate information across different spatial scales. Finally, the training methodology is important; pre-training on large datasets (like ImageNet and UCF101) is likely used to initialize the network with useful feature representations before fine-tuning on the specific task of modeling visual cortical responses to movie stimuli. The success of this approach hinges on the careful selection and interaction of these design elements.

TSRSA Methodology#

The proposed Time-Series Representational Similarity Analysis (TSRSA) methodology offers a novel approach to evaluating the representational similarity between model and neural data, particularly for dynamic stimuli like movies. TSRSA directly addresses the temporal dependencies inherent in sequential data, unlike traditional RSA which only considers static comparisons between individual stimuli. By calculating Pearson correlation coefficients between time-series representations of sequential movie frames, TSRSA captures both static and dynamic aspects. The use of Spearman rank correlation to compare model and neural data further enhances robustness. This approach allows for a direct comparison between model representations and neurophysiological data from the mouse visual cortex under movie stimuli, offering a comprehensive assessment of model performance in mimicking the biological visual system’s dynamic processing capabilities. TSRSA’s strength lies in its ability to quantify the impact of dynamic information, and its application in the paper provides a more nuanced analysis of neural representations than traditional methods.

Dynamic Info Impact#

The section ‘Dynamic Info Impact’ would explore how the temporal or sequential nature of visual information affects the model’s performance and its ability to capture neural representations. It would likely involve experiments where the temporal structure of movie stimuli is manipulated (e.g., shuffling frames, introducing gaps) to assess the model’s sensitivity to dynamic information. Key findings would likely show a significant drop in representational similarity when temporal structure is disrupted, indicating the importance of temporal processing in the model. The analysis would likely compare results to those obtained using only static images, highlighting the added value of incorporating temporal dynamics. The degree of performance drop could further be quantified and correlated with the level of temporal disruption, revealing nuanced insights into the model’s sensitivity to dynamic elements. This section would solidify the model’s advantage by directly demonstrating the importance of modeling dynamic aspects of visual information processing within the brain.

Model Limitations#

A critical analysis of the model’s limitations reveals several key weaknesses. First, the reliance on specific datasets (UCF101 and ImageNet) may limit the model’s generalizability to other types of movie stimuli or visual data. Second, despite incorporating biologically plausible mechanisms, the model is still a simplification of the complex visual processing in the brain. Further investigation is needed to better capture the dynamics of neural activity in the visual cortex. Third, while the model shows high representational similarity, the current evaluation metrics might not fully encompass the subtleties of visual perception. More comprehensive benchmarks are required to address the limitations in evaluating dynamic representations. Finally, future work should focus on addressing potential biases inherent in the training data and explore potential societal impacts stemming from model misuse.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Firstly, enhancing LoRaFB-SNet’s biological realism by incorporating more sophisticated neuronal models and a wider range of brain-inspired mechanisms (e.g., diverse synaptic plasticity, detailed neurotransmitter dynamics) would improve its predictive power. Secondly, investigating how LoRaFB-SNet generalizes to other visual modalities (e.g., auditory, tactile) and animal species would expand its scope. Thirdly, applications of the network to new tasks (e.g., visual attention modeling, object recognition in complex scenes) should be explored, focusing on the interplay between dynamic and static processing. Finally, developing more nuanced methods for measuring representational similarity, considering finer-grained temporal and contextual aspects of visual information processing, is crucial for a complete understanding of the brain’s visual mechanisms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the experimental setup. Six visual cortical regions of a mouse brain and the LoRaFB-SNet model are both shown receiving the same movie stimuli. The model’s generated representations are then compared to the brain’s representations using Time-Series Representational Similarity Analysis (TSRSA) to quantify the similarity. To understand the effects of temporal and textural information, two altered versions of the movie (one with temporally shuffled frames and one with altered textures) are given to the model while the original movie remains the input to the visual cortex. Comparing similarities in all three conditions (original, shuffled, and texture-altered) provides insights into how dynamic and static information affect neural representations.

This figure illustrates the experimental setup used to compare the model’s representations with those of the mouse visual cortex. Six visual cortical areas receive the same movie, and their responses are compared to a model’s responses using Time-Series Representational Similarity Analysis (TSRSA). To further analyze the impact of dynamic and static information, modified movie stimuli (shuffled frames and noise image replacements) are fed into the network, while the visual cortex continues to receive the original movie. The results help to understand the relative contributions of temporal and static factors in visual processing.

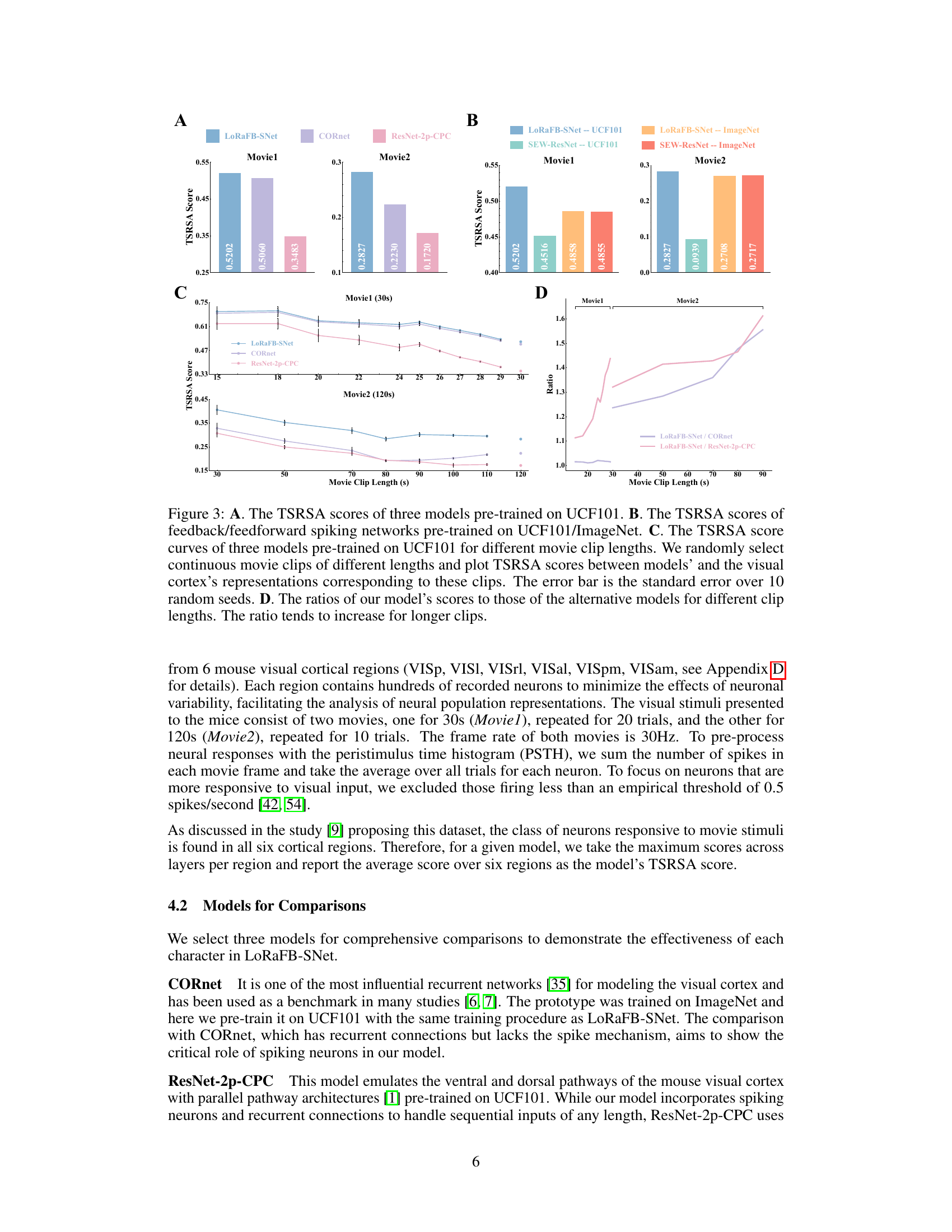

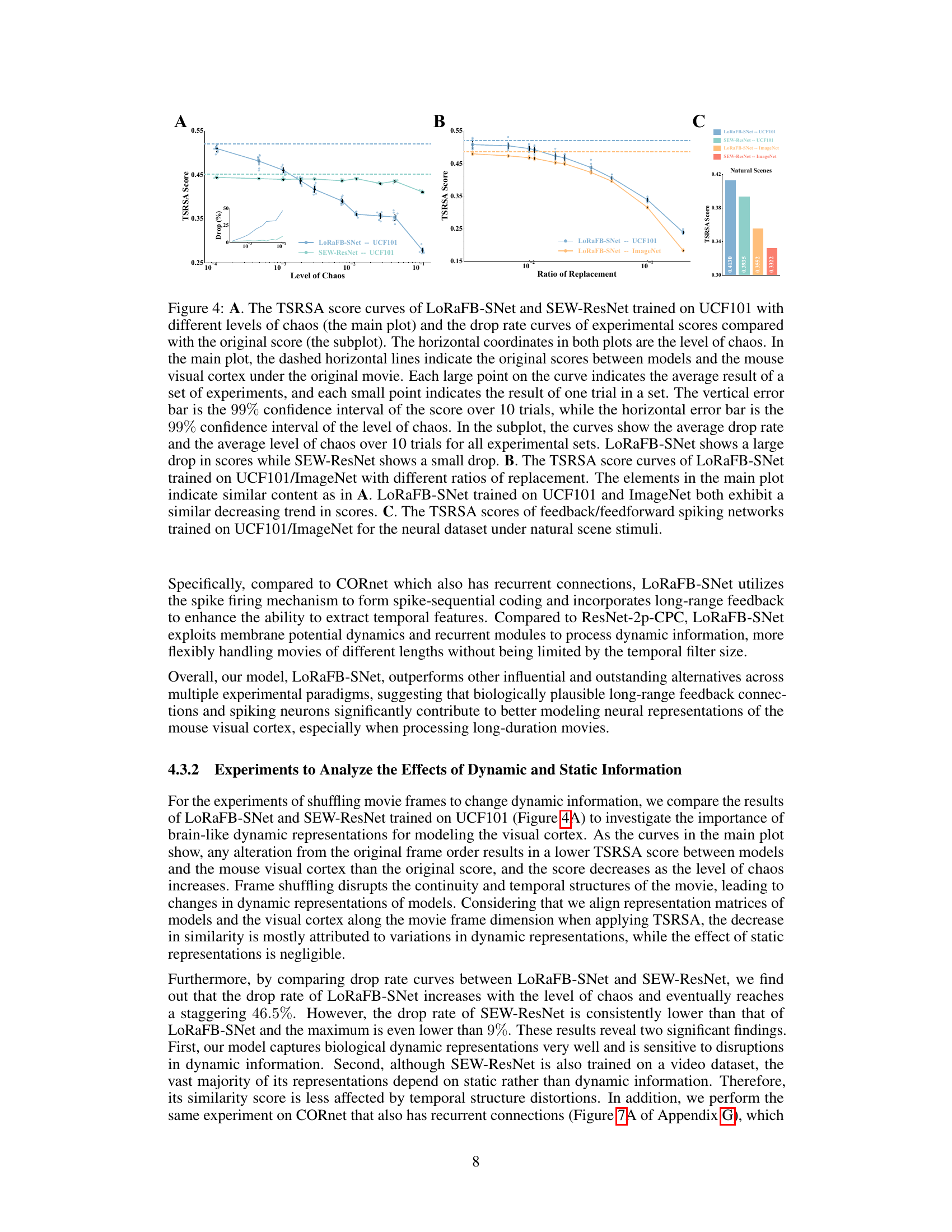

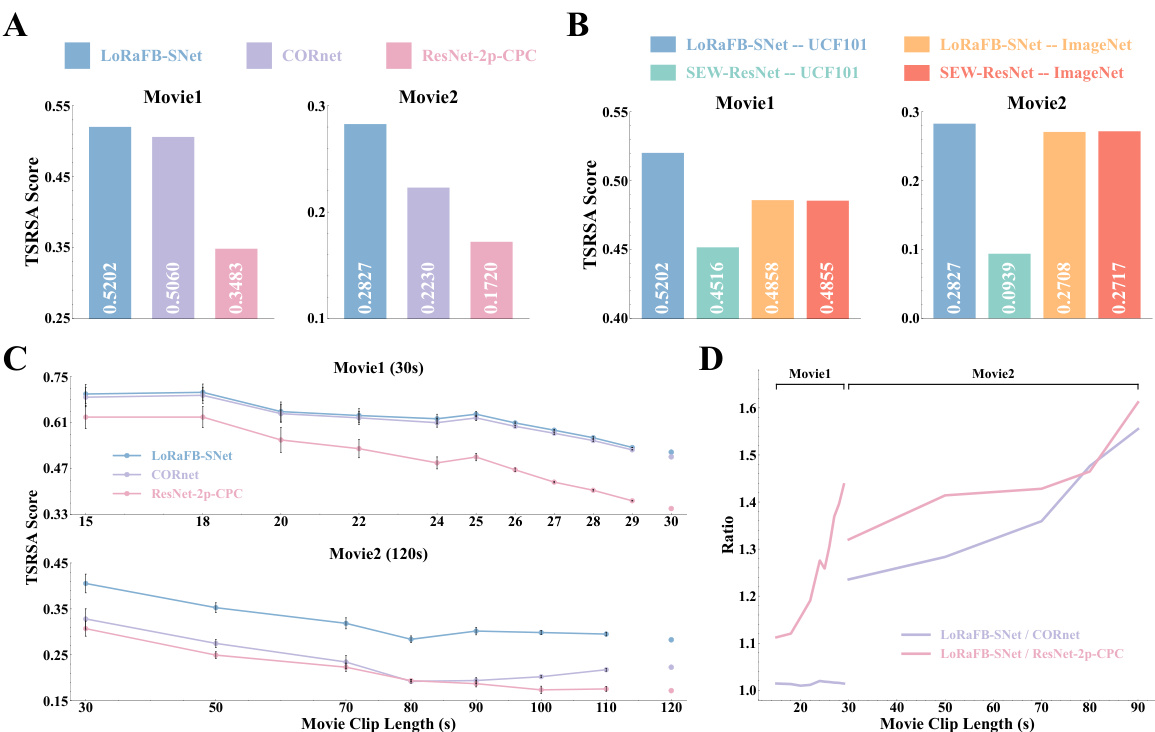

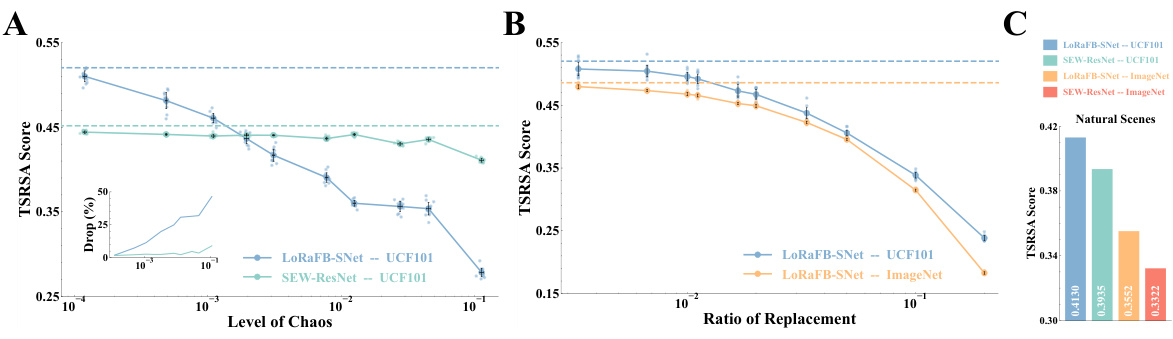

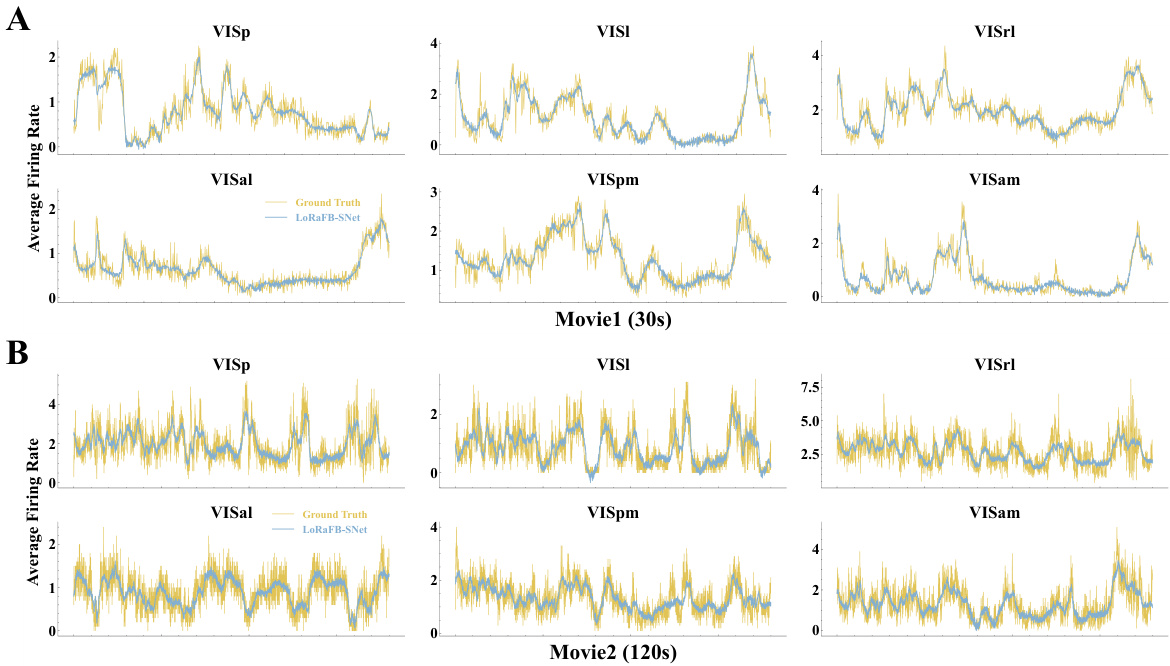

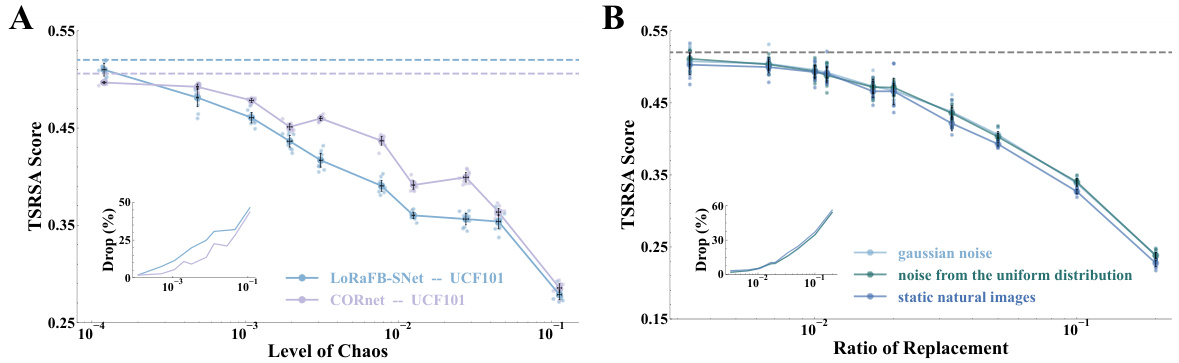

This figure demonstrates the effect of disrupting temporal structure (A) and static texture (B) of movie stimuli on the representational similarity between model and mouse visual cortex. Panel A shows that LoRaFB-SNet is much more sensitive to changes in temporal structure than SEW-ResNet. Panel B shows that both models are negatively affected by changes in static texture, but LoRaFB-SNet maintains higher similarity than SEW-ResNet. Panel C compares the performance on natural scene images.

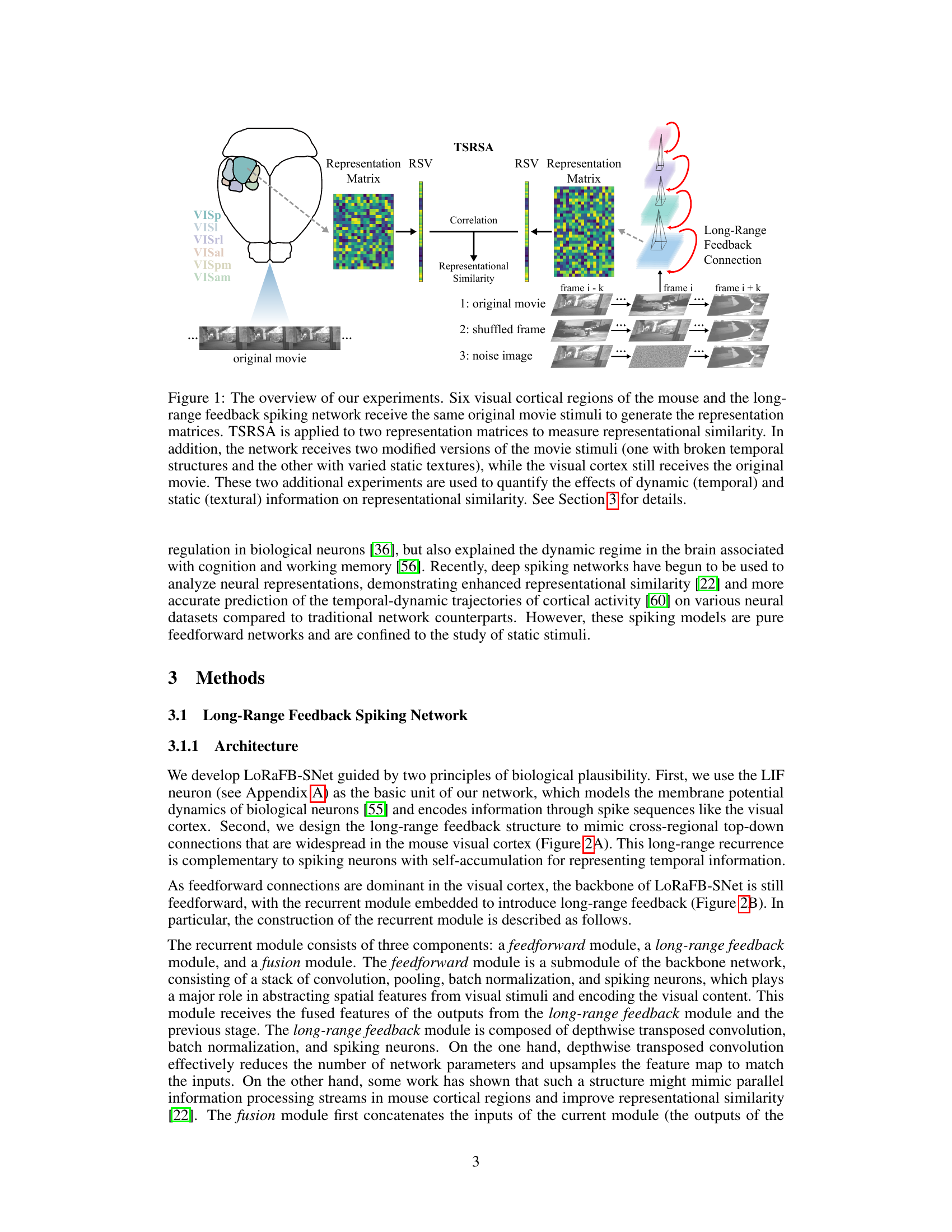

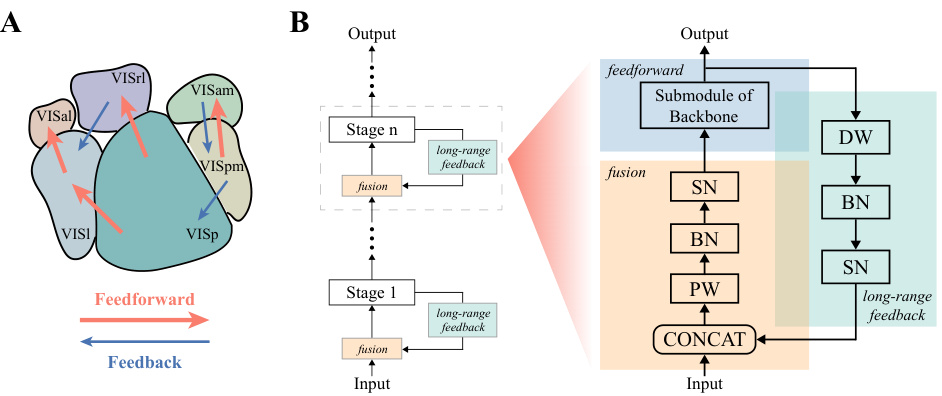

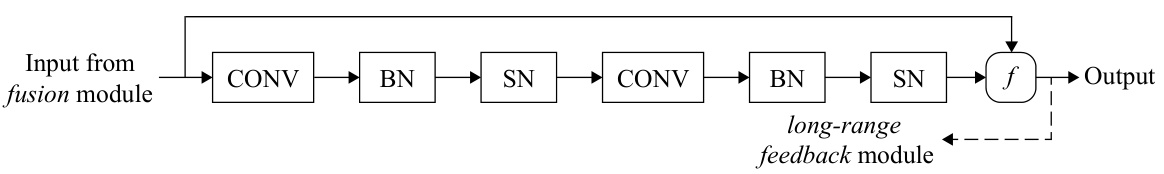

Figure 2A shows a schematic representation of the six visual cortical areas in a mouse brain, highlighting the feedforward and feedback connections between them. Figure 2B illustrates the architecture of the LoRaFB-SNet model, focusing on the recurrent module which incorporates feedforward, long-range feedback, and fusion components. This recurrent module mimics the top-down connections between cortical areas in the brain. More details on this architecture are provided in Section 3.1 of the paper.

This figure illustrates the experimental design used to evaluate the proposed LoRaFB-SNet model. Six visual cortical regions of a mouse brain and the model receive the same movie as input. Representational Similarity Analysis (RSA) is used to compare the representations generated by both the model and the brain. Two additional control experiments are performed where the model receives altered movie stimuli (shuffled frames and noise-replaced frames) to isolate the effects of temporal and static information on representation similarity.

This figure shows the results of experiments designed to quantify the effects of dynamic and static information on representational similarity. Panel A compares the impact of disrupting the temporal order (introducing chaos) of movie stimuli on the representational similarity of LoRaFB-SNet and SEW-ResNet models. Panel B examines the effect of replacing frames in the movie with noise images (varying static information) on the representational similarity. Panel C shows the models’ performance on a natural scene stimuli.

More on tables

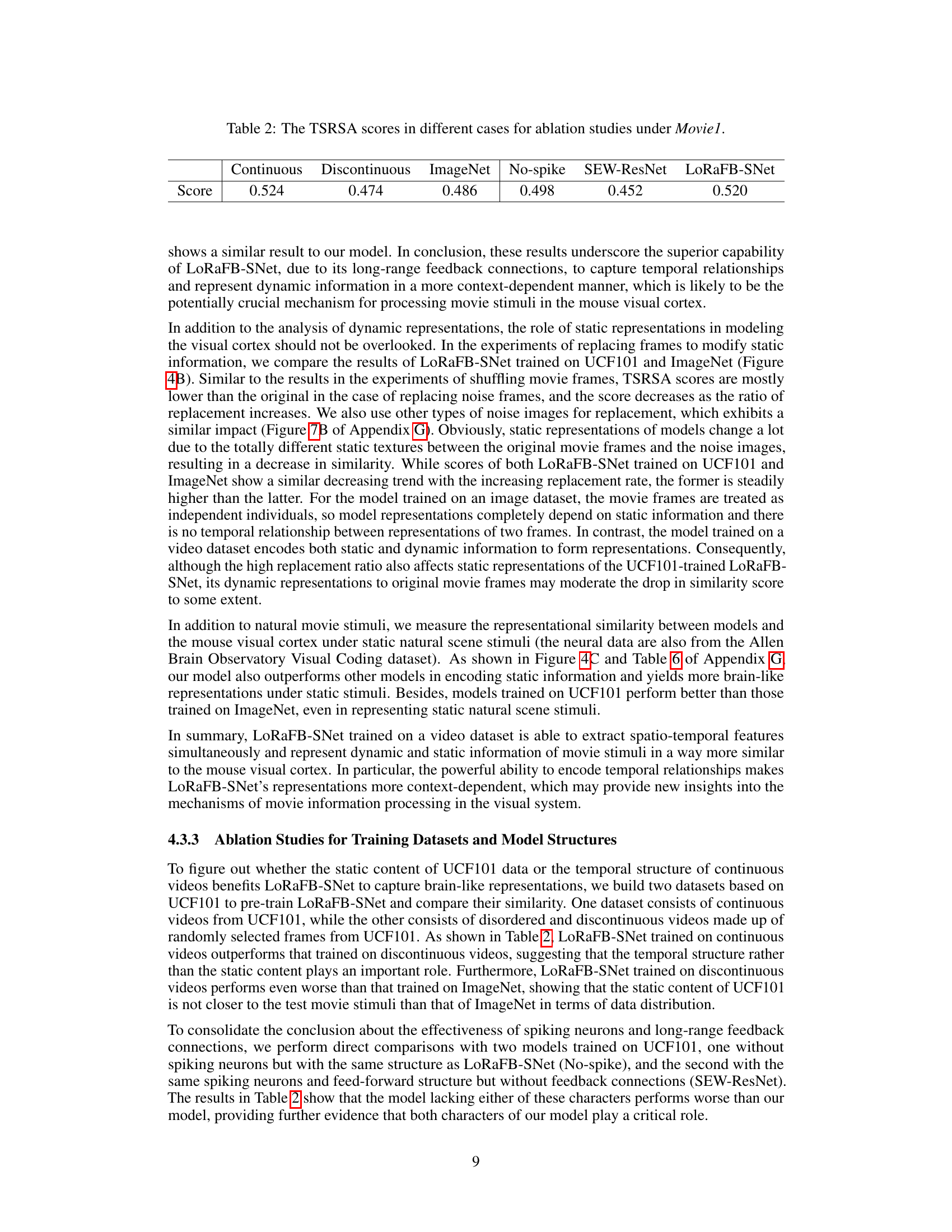

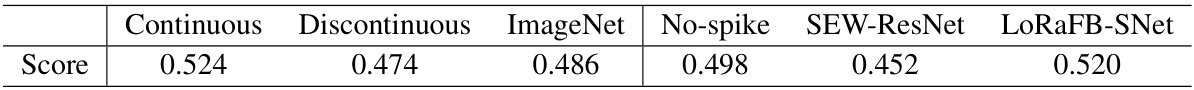

This table presents the TSRSA scores obtained from ablation studies conducted using the Moviel dataset. It compares the performance of LoRaFB-SNet under different conditions: using continuous movie clips, discontinuous movie clips, pre-training on ImageNet instead of UCF101, removing the spiking mechanism, and using SEW-ResNet instead of LoRaFB-SNet. The results highlight the impact of different training data, model structures, and mechanisms on the representational similarity to mouse visual cortex.

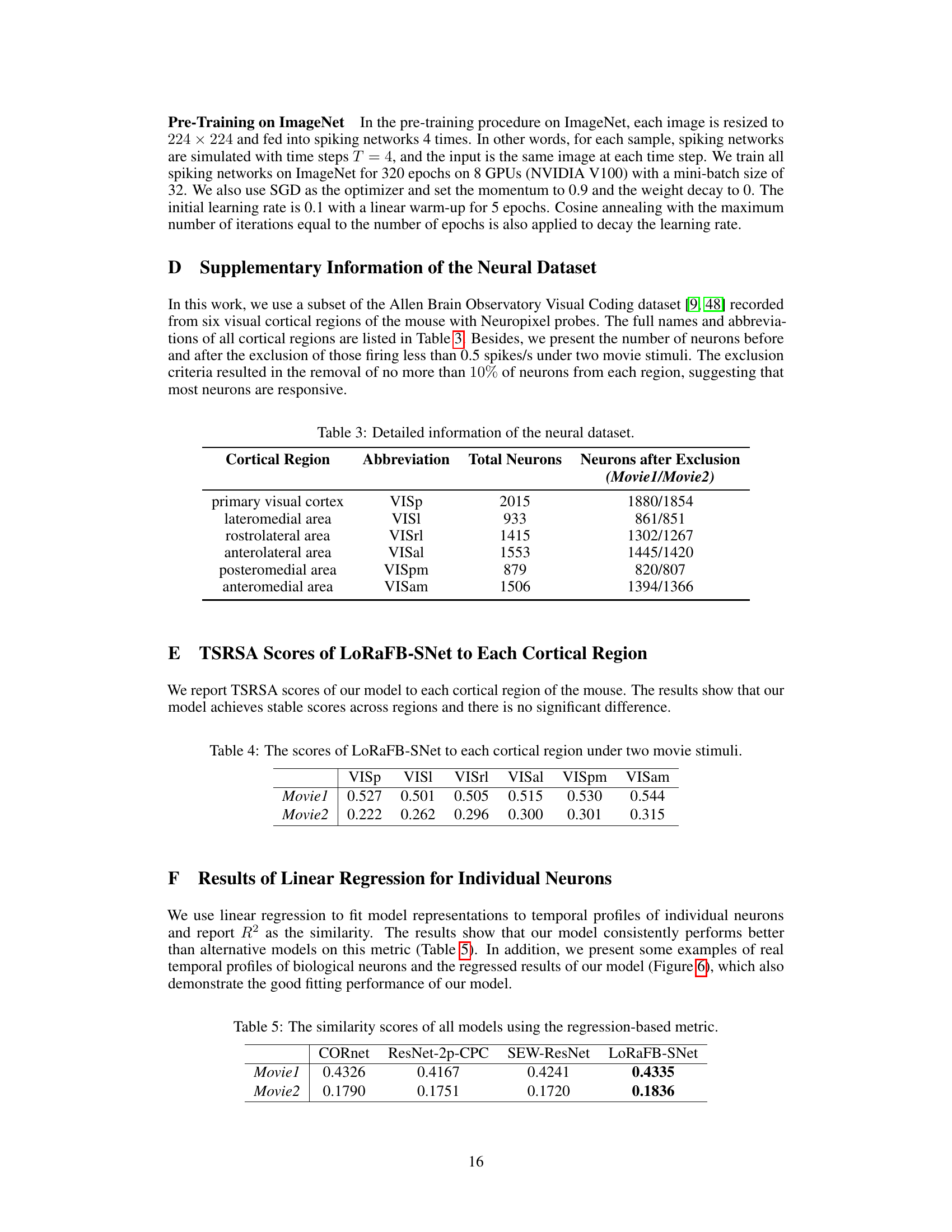

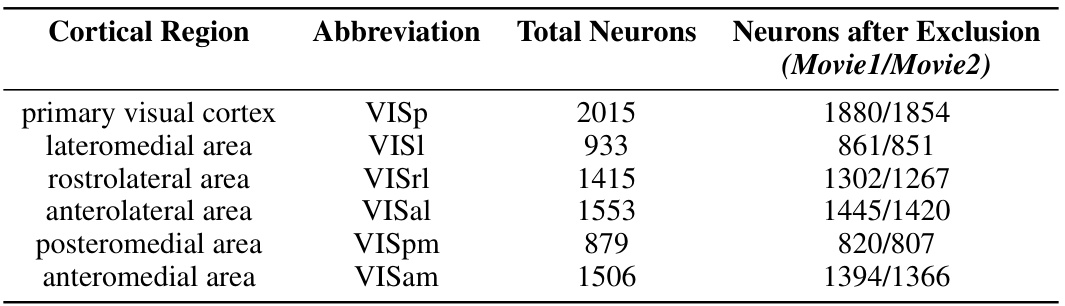

This table presents the number of neurons recorded from six visual cortical regions of the mouse brain. It shows the total number of neurons for each region and, after applying an exclusion criterion (removing neurons with less than 0.5 spikes/second activity during the movie stimuli), the remaining neuron counts for two different movie stimuli (Movie1 and Movie2). This data reduction is to focus on neurons that are more responsive to visual stimuli.

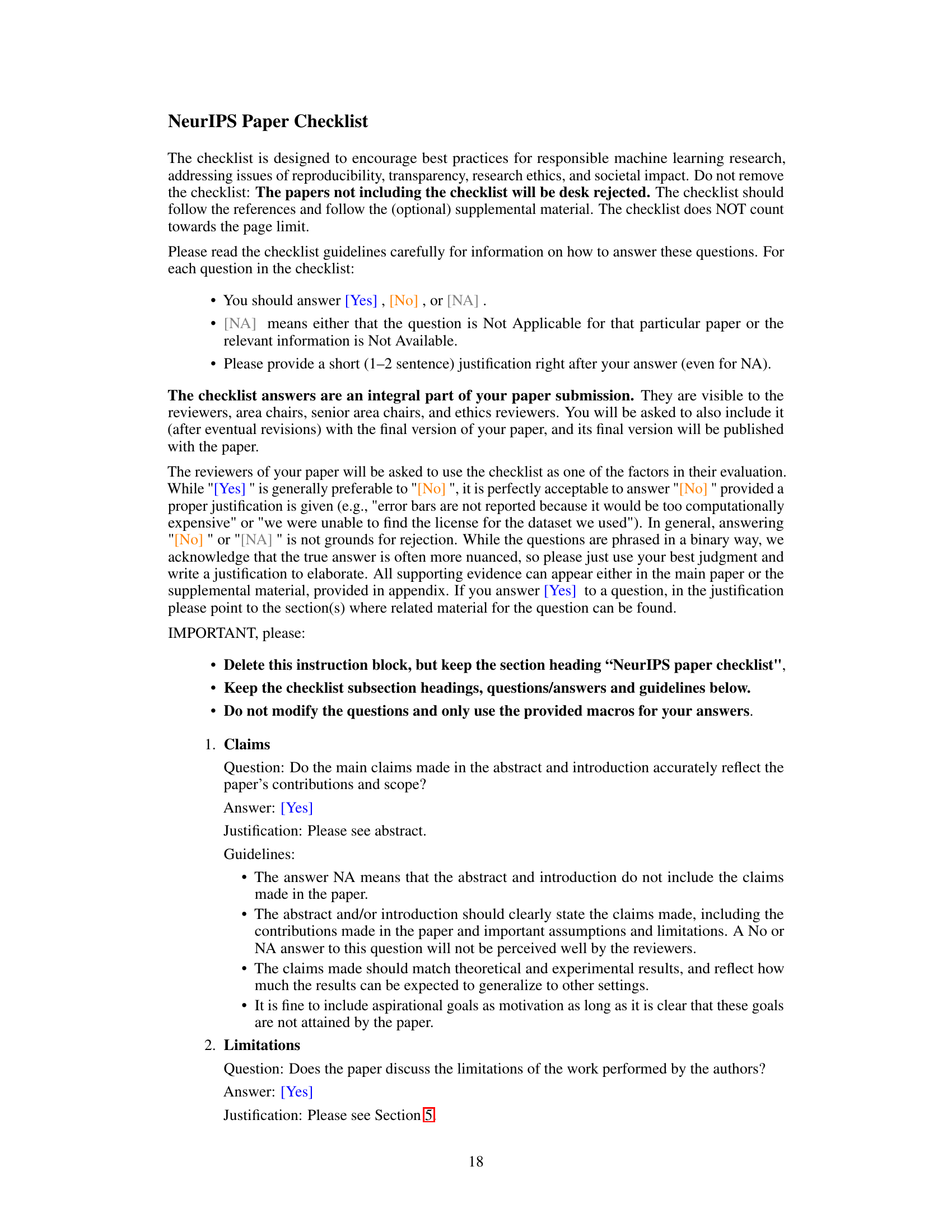

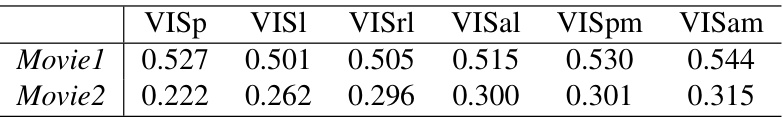

This table presents the Representational Similarity Analysis (TSRSA) scores achieved by the LoRaFB-SNet model when compared to six different visual cortical regions (VISp, VISl, VISrl, VISal, VISpm, VISam) in the mouse brain. The scores are given for two different movie stimuli, Movie1 and Movie2, showing the model’s representational similarity to each region under different movie conditions.

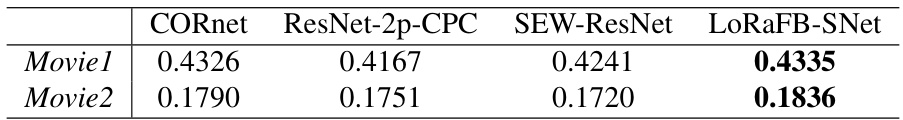

This table presents the R-squared (R²) values obtained from linear regression analyses, comparing model representations against the temporal activity profiles of individual neurons in each cortical region. Higher R² values indicate better agreement between model predictions and biological neural data. The table shows the performance of LoRaFB-SNet, CORnet, ResNet-2p-CPC, and SEW-ResNet across two movie stimuli (Movie1 and Movie2).

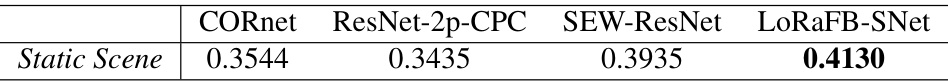

This table presents the representational similarity analysis (RSA) scores achieved by four different models (CORnet, ResNet-2p-CPC, SEW-ResNet, and LoRaFB-SNet) when tested on static natural scene stimuli from the Allen Brain Observatory Visual Coding dataset. The scores represent the similarity between each model’s representation and the neural representations of the mouse visual cortex under static natural scene stimuli. The table aims to show how well each model captures static scene features.

Full paper#