↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current video representation methods struggle with complex motions and occlusions due to limitations in 2D/2.5D approaches. Implicit 3D representations are also insufficient for manipulation tasks. This necessitates a more robust video representation capable of disentangling appearance and motion.

This paper introduces Video Gaussian Representation (VGR), an explicit 3D representation that leverages 3D Gaussians to model video appearance and motion in a canonical space. By incorporating 2D priors such as optical flow and depth from foundation models, VGR effectively regularizes learning and achieves high consistency. The effectiveness of VGR is demonstrated across numerous video processing tasks, showcasing its versatility and potential to significantly improve various video applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel and versatile video representation method. It offers a more intuitive and explicit 3D representation compared to existing 2D/2.5D approaches, enabling effective handling of complex video processing tasks. The use of 3D Gaussians and the incorporation of 2D priors for regularization is a significant contribution. This work opens up new avenues for research in video editing, tracking, depth estimation, and more, potentially impacting various applications in fields like filmmaking, social media, and advertising.

Visual Insights#

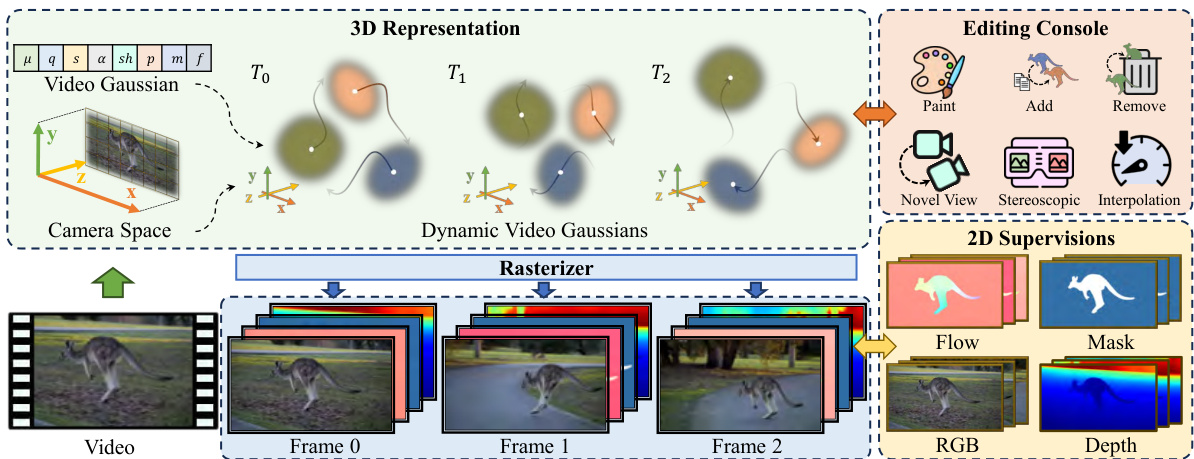

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the proposed approach. A video is converted into a Video Gaussian Representation (VGR), which is then used for various downstream video processing tasks, including tracking, depth prediction, stereoscopic view synthesis, and video editing. The VGR serves as a convenient and versatile intermediate representation that facilitates these tasks.

This table compares the proposed method with several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the DAVIS dataset using the Tap-Vid benchmark. The metrics used for comparison include PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS, Average Jaccard Index (AJ), Average Overlap (OA), and Temporal Consistency (TC). Additionally, the table provides information on training time, GPU memory usage, and frames per second (FPS) to give a comprehensive comparison of computational efficiency. The results indicate that the proposed method outperforms other methods in several metrics, demonstrating its superior performance and efficiency.

In-depth insights#

3D Gaussian Encoding#

The concept of “3D Gaussian Encoding” for video representation presents a compelling approach to overcome limitations of existing 2D methods. By representing video frames as a collection of 3D Gaussians in a canonical space, this technique offers explicit 3D modeling of appearance and motion. Each Gaussian’s position, orientation, scale, and appearance (e.g., color) would be encoded, with temporal dynamics explicitly defined by associating each Gaussian with time-dependent 3D motion attributes. This approach is particularly powerful because it naturally handles complex motion and occlusions, which challenge 2D methods. However, there are challenges inherent in learning such a representation, particularly in mapping from the observed 2D projections to the underlying 3D structure. The use of monocular cues like optical flow and depth as regularization signals could prove crucial to the success of this technique. Successful implementation would likely lead to significant advancements in video processing tasks requiring 3D understanding, including view synthesis, depth estimation, and consistent video editing.

Motion Regularization#

Motion regularization, in the context of video processing and 3D Gaussian representation, is crucial for learning robust and realistic video dynamics. It addresses the inherent ambiguity in mapping a 2D video sequence to a 3D representation, where multiple plausible 3D interpretations could exist for a single observed 2D projection. The goal is to constrain the learning process, guiding the model towards solutions that are consistent with real-world physics and motion patterns. This is particularly challenging because of factors such as occlusions, scene complexities, and noisy data. Therefore, regularization techniques, such as incorporating 2D priors (like optical flow and depth maps) and imposing 3D motion constraints (e.g., local rigidity), help prevent overfitting and ensure that the learned motion is plausible and faithful to the original video. Flow distillation aligns the projected 3D motion of Gaussians with estimated optical flow, while depth distillation regularizes the scene geometry using estimated depth maps. This combined approach ensures that the model learns both appearance and motion effectively, resulting in a versatile 3D representation suitable for numerous downstream tasks.

Versatile Video Apps#

A hypothetical research paper section titled “Versatile Video Apps” would explore the diverse applications enabled by a novel video representation method. The core idea would be to demonstrate the representation’s versatility by showcasing its effectiveness across various video processing tasks. Specific applications might include video editing (e.g., object removal, appearance changes), tracking, depth prediction, view synthesis, and interpolation. The discussion would highlight how the proposed representation simplifies and improves performance in each of these areas, potentially compared to existing state-of-the-art methods. A key aspect would be demonstrating the handling of complex scenarios like occlusions and self-occlusions, which often pose significant challenges for traditional techniques. The section would conclude by emphasizing the representation’s potential to unlock new and innovative video applications, paving the way for future research directions. The results and examples presented would be critical in validating the claimed versatility and demonstrating the practical benefits of the new approach.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components or features of a model to assess their individual contributions and importance. In this context, it would likely involve removing different parts of the proposed video Gaussian representation (VGR) framework, one at a time, and observing the effects on various downstream tasks, such as tracking and video editing. Key elements to investigate might include the 3D Gaussian representation itself, the 2D monocular priors (optical flow and depth), the 3D motion regularization, and the combination of these factors. The results would quantitatively demonstrate the impact of each component on the overall performance, highlighting essential elements for the VGR’s effectiveness and possibly revealing potential redundancies or less crucial aspects. This systematic evaluation reveals important insights into the model’s architecture and the role of each component in achieving high performance and robustness.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this video Gaussian representation (VGR) method could explore several promising avenues. Extending VGR to handle significantly larger-scale scene changes and highly non-rigid motions is crucial. This could involve incorporating more sophisticated motion models or combining VGR with other advanced techniques like neural fields to better capture complex dynamics. Improving the efficiency of the rendering process is also important, as current methods can be computationally intensive. Research into more efficient rendering algorithms, potentially leveraging hardware acceleration, would make the VGR more practical for real-time applications. Finally, developing a more user-friendly interface for the VGR would be beneficial. This could enable broader adoption of this method in various video processing applications. Furthermore, future work could focus on applying this method to other modalities, including audio-visual data, thereby creating a more versatile multimodal representation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the proposed method. The input is a video sequence. The video is converted to a 3D representation using video Gaussians in a camera coordinate space. Each Gaussian is associated with motion parameters to capture video dynamics. The representation is supervised using RGB frames and additional 2D priors such as optical flow, depth, and masks. This allows convenient video editing and processing operations, including painting, adding, removing objects and novel view and stereoscopic video interpolations.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of video reconstruction results obtained using the proposed method and three state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods: CoDeF, Omnimotion, and Ground Truth (GT). The figure presents two example video sequences side-by-side. In each example, the results from each method are shown in separate frames, allowing for a visual comparison of the reconstruction quality. This comparison highlights the ability of the proposed method to generate more realistic and detailed video reconstructions compared to existing methods.

This figure shows a comparison of dense tracking results between the proposed method and two state-of-the-art methods (CoDeF and 4DGS) across three different video clips. Each clip presents unique challenges for tracking, including large-scale changes in viewpoint and fast object motion. The visualization highlights the superior performance of the proposed method, especially in handling these complex motion patterns.

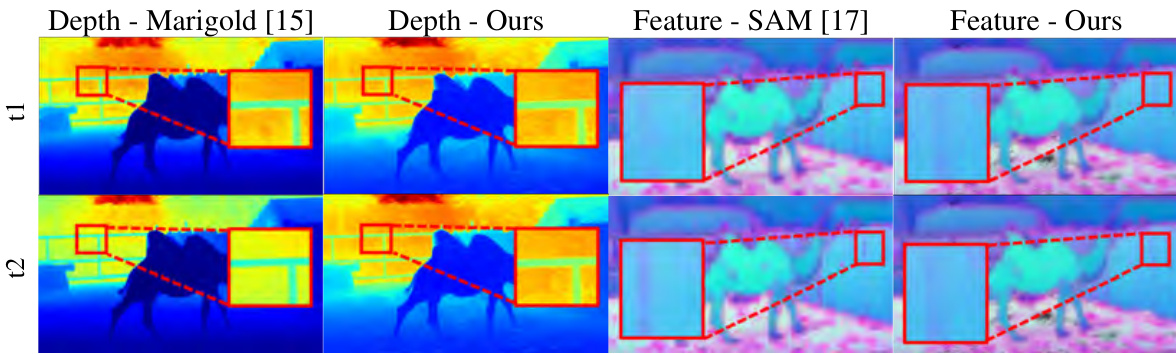

This figure compares the video depth and features generated by the proposed method with those from state-of-the-art (SOTA) single-frame estimation methods. It visually demonstrates that the proposed method produces more consistent depth and feature estimations across frames compared to the SOTA methods. The improved consistency is highlighted by the visual differences in the depth and feature maps generated by each approach. Red boxes highlight regions where the difference is most apparent.

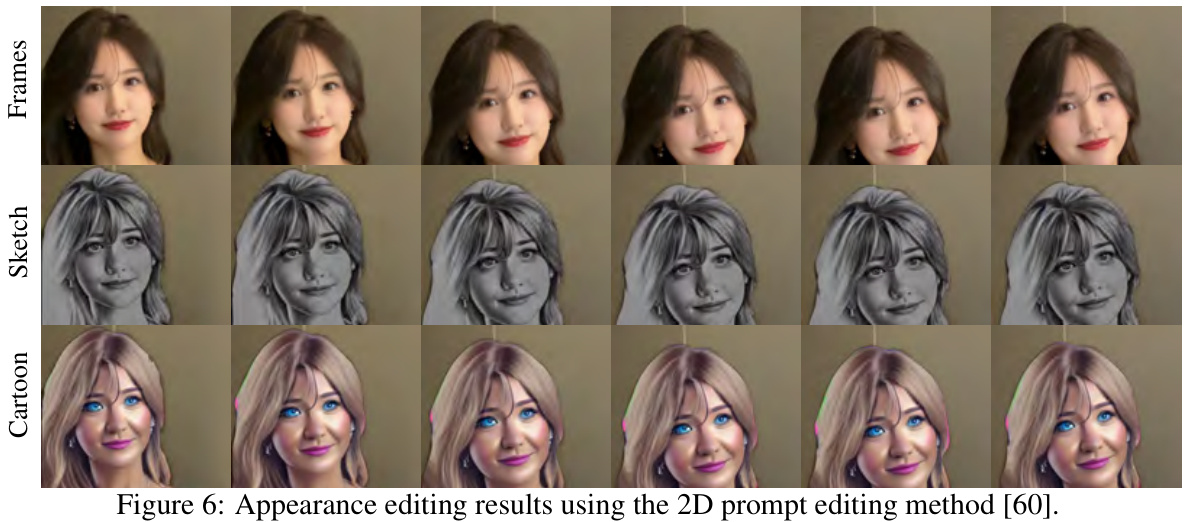

This figure shows the results of appearance editing on a video using a 2D prompt editing method. The top row displays the original video frames. The middle row shows the results of applying a sketch-like style transfer, and the bottom row shows the results of applying a cartoon-like style transfer. The results demonstrate that the proposed method is able to effectively transfer appearance styles to videos.

This figure demonstrates the proposed method of converting a video into a Video Gaussian Representation (VGR). It shows the input video and several downstream applications that benefit from this representation, such as tracking, consistent depth prediction, stereoscopic video synthesis, and video editing. The VGR acts as an intermediary step to enable convenient and versatile video processing.

This figure shows the results of stereoscopic video creation using the proposed Video Gaussian Representation (VGR). The first column displays a single frame from the original video. The remaining columns present synthesized stereoscopic views generated by slightly translating the video Gaussians horizontally, simulating the interocular distance. This demonstrates the 3D capabilities of the VGR, enabling the creation of novel viewpoints and stereoscopic videos.

This figure shows two scenarios where the proposed method, which does not estimate camera poses, may underperform. In the first scenario (left), the model must learn large camera rotations as scene motions, which results in blurry backgrounds. In the second scenario (right), it fails to track fast-moving objects because the photometric loss is insufficient for accurate motion fitting. The figure visually compares the ground truth video frames with the results generated by the proposed method, highlighting the limitations in handling complex motion scenarios.

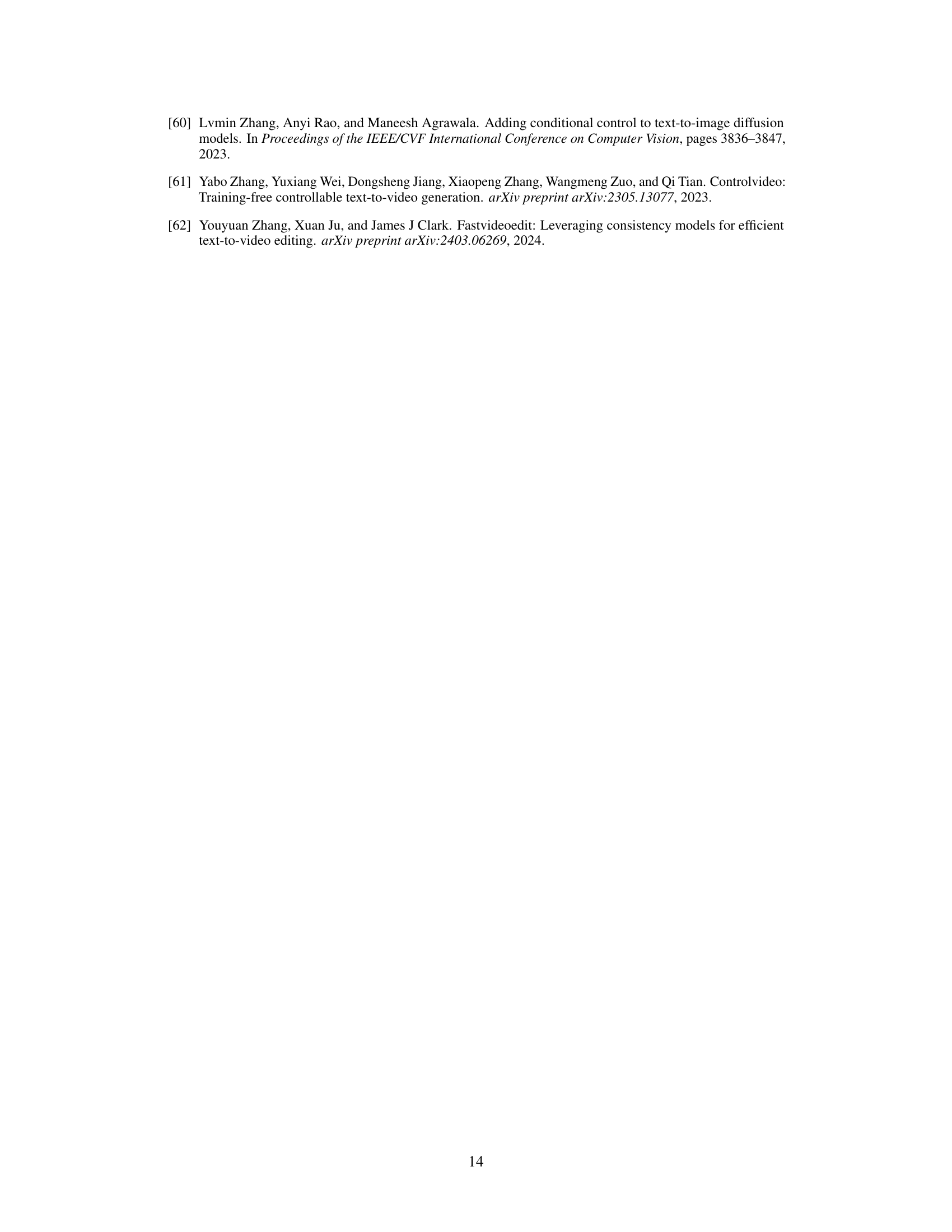

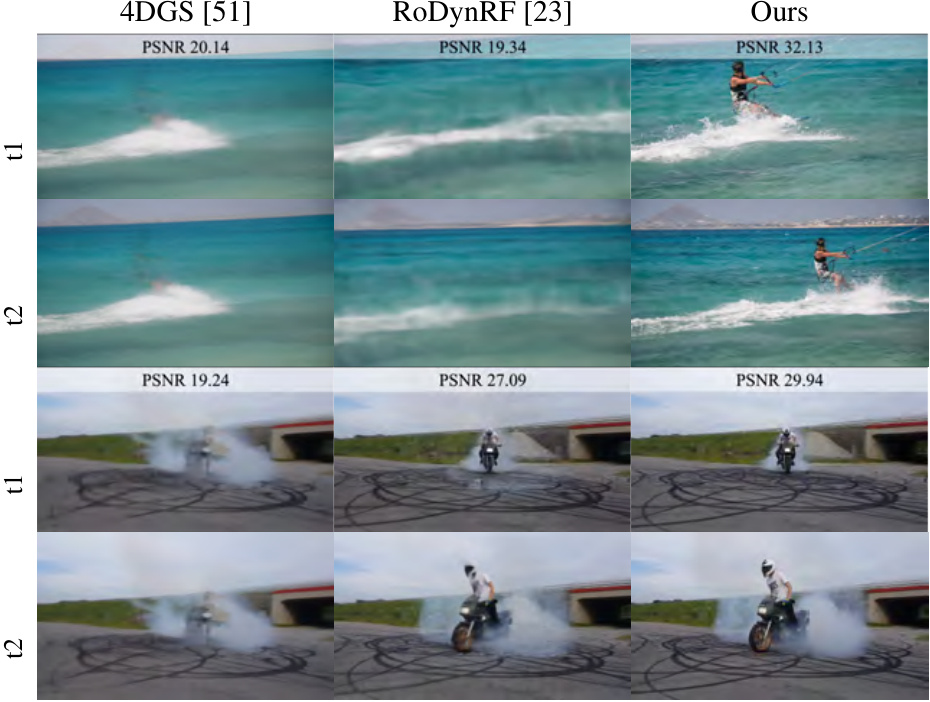

This figure compares the video reconstruction quality of the proposed method with two state-of-the-art methods, RoDynRF and 4DGS. Two video examples are shown: a person wakeboarding and a motorcycle doing a wheelie. For each example, the figure displays two frames (t1 and t2) reconstructed by each method. The Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) values are provided for each reconstruction to quantify the visual quality. The results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves significantly higher PSNR values, indicating superior visual quality compared to the other two methods.

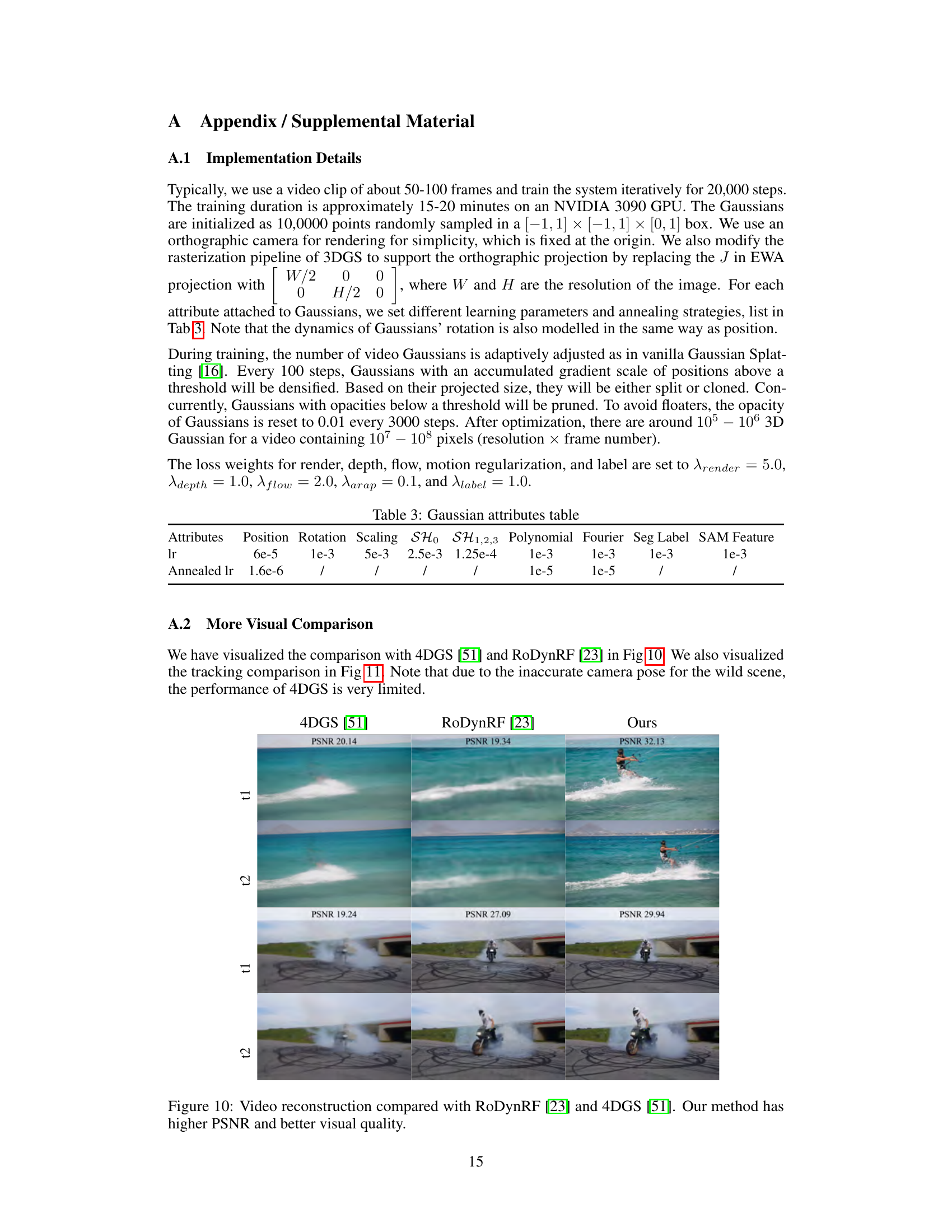

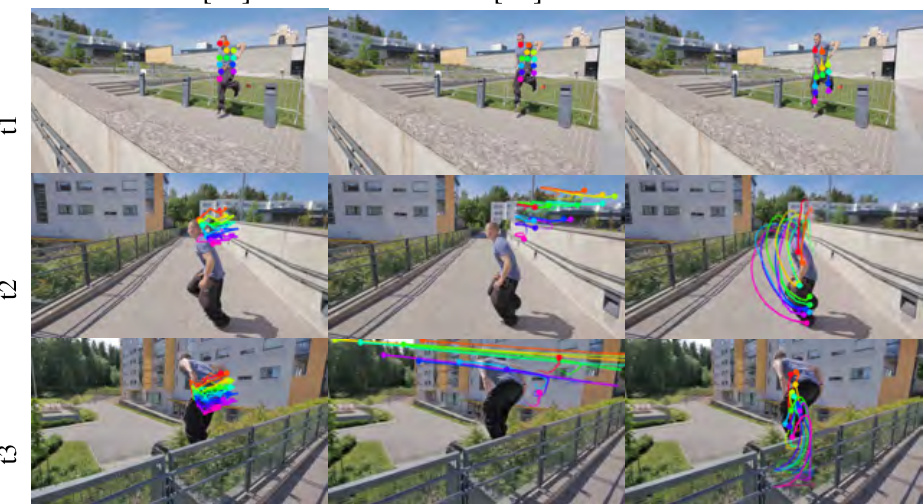

This figure compares the dense tracking results of three different methods: CoDeF, 4DGS, and the proposed method. The results are shown across several frames of a video depicting a person performing parkour-like movements. The visualization highlights the ability of each method to accurately track the person’s movement through significant changes in viewpoint and the challenges of dealing with complex motion. The proposed method showcases better performance in maintaining consistent and accurate tracking across the frames compared to the other two methods.

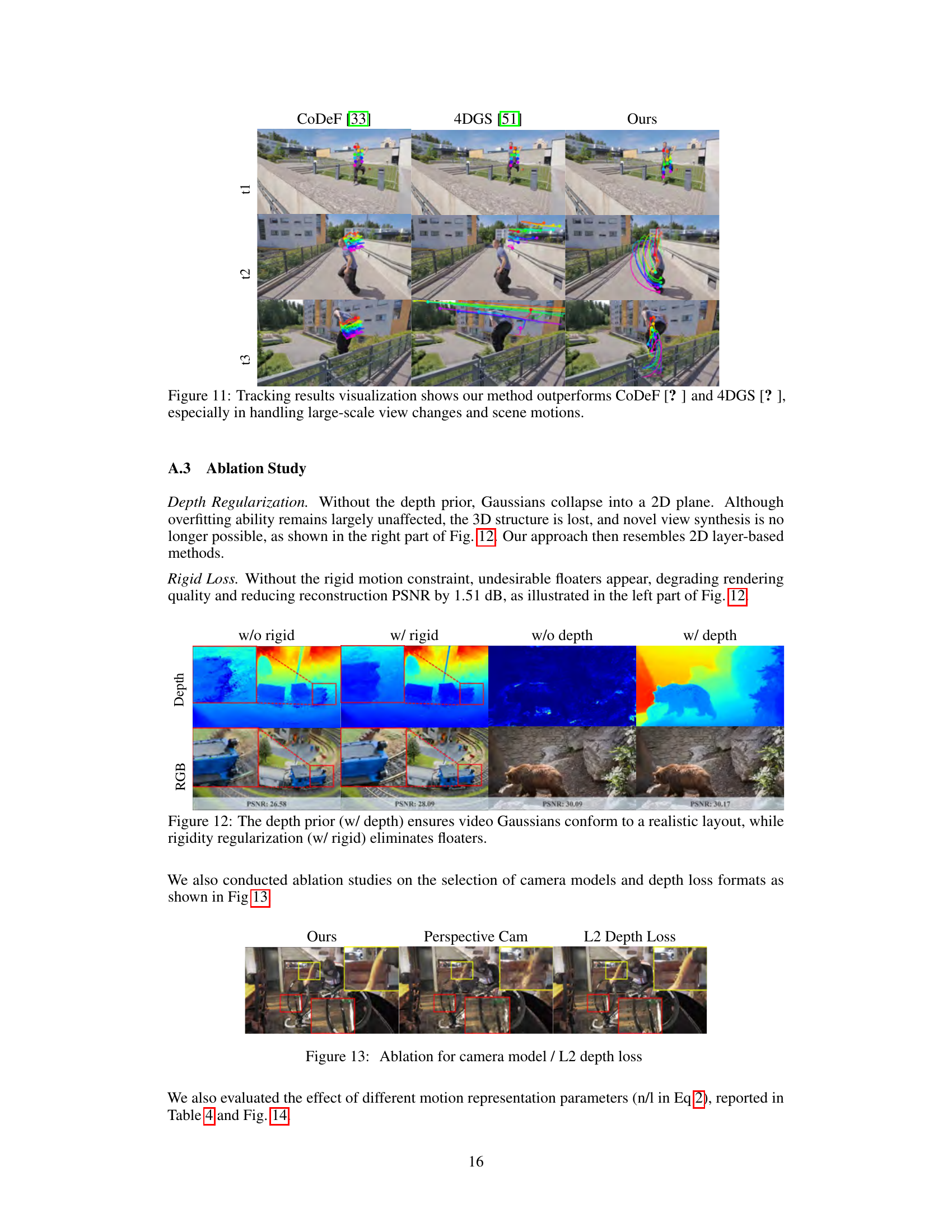

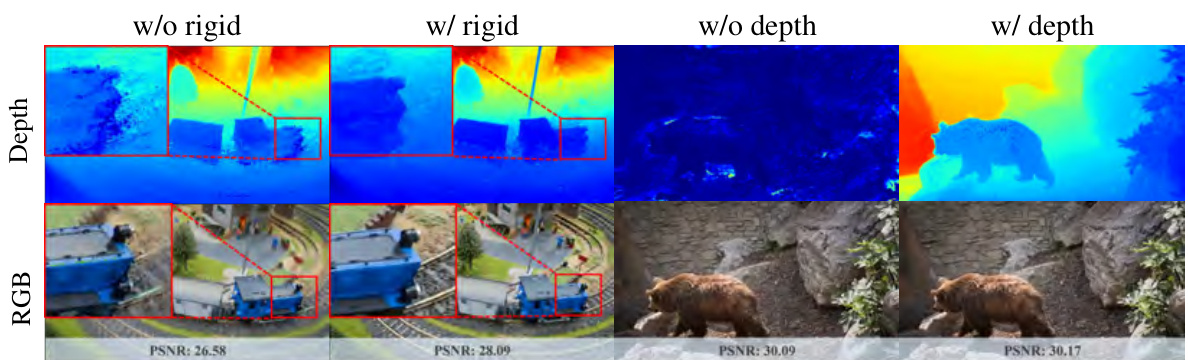

This figure in the paper demonstrates the effects of depth and rigidity regularization on the generated video. The top row shows depth maps, and the bottom row shows the corresponding RGB frames. The leftmost column (w/o rigid) shows the result without rigidity regularization – notice the unrealistic floating structures. The second column (w/ rigid) shows the improved result with rigidity regularization, which eliminates the floating structures. The third and fourth columns show the effect of the depth prior (w/ depth vs w/o depth). The improved consistency and realistic representation of depth in the image on the rightmost column highlight the benefit of using the depth prior.

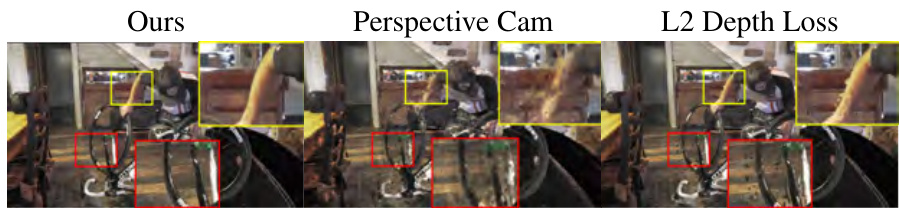

This figure shows the ablation study results for different camera models (orthographic vs. perspective) and depth loss functions (scale-and-shift-trimmed loss vs. L2 loss). It visually demonstrates the impact of these choices on the quality of the video reconstruction, highlighting the importance of the chosen camera model and depth loss in maintaining the 3D structure and visual fidelity of the representation.

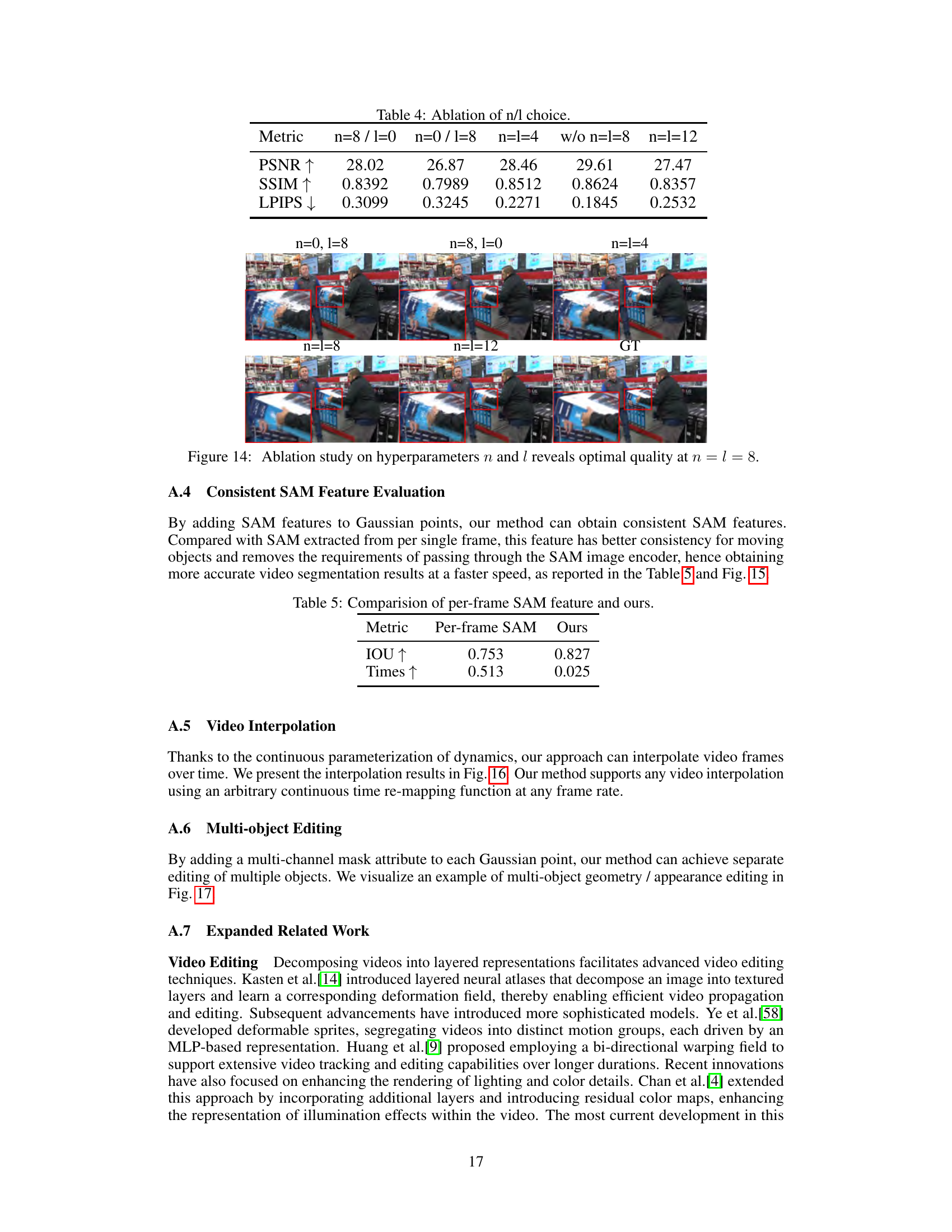

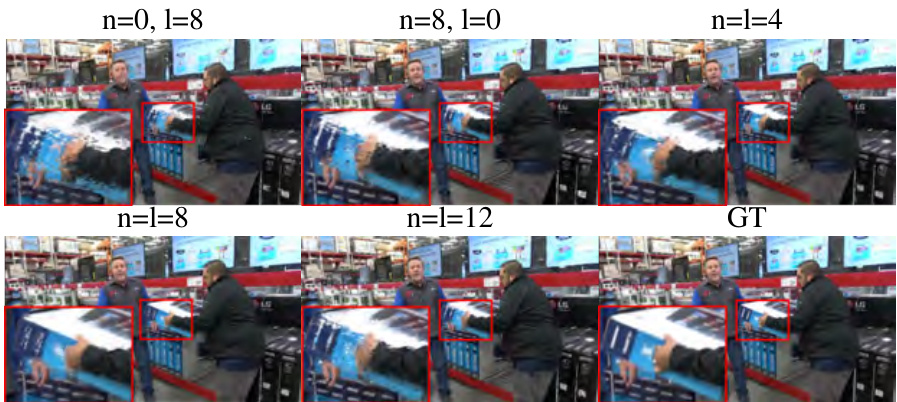

This figure shows an ablation study on the hyperparameters n and l used in the paper’s method for representing the 3D motion of Gaussian points. The study is conducted by testing different combinations of n and l values and comparing the results to the ground truth (GT). Each row of the image shows a sequence of frames reconstructed with different n and l combinations, with a red bounding box highlighting the area of interest. The results show that the optimal quality is achieved when n = 8 and l = 8, indicating that the model benefits from both polynomial and Fourier bases in representing the smooth trajectories of objects. However, using only polynomial bases (n=0, l=8) or only Fourier bases (n=8, l=0) significantly degrades the result quality.

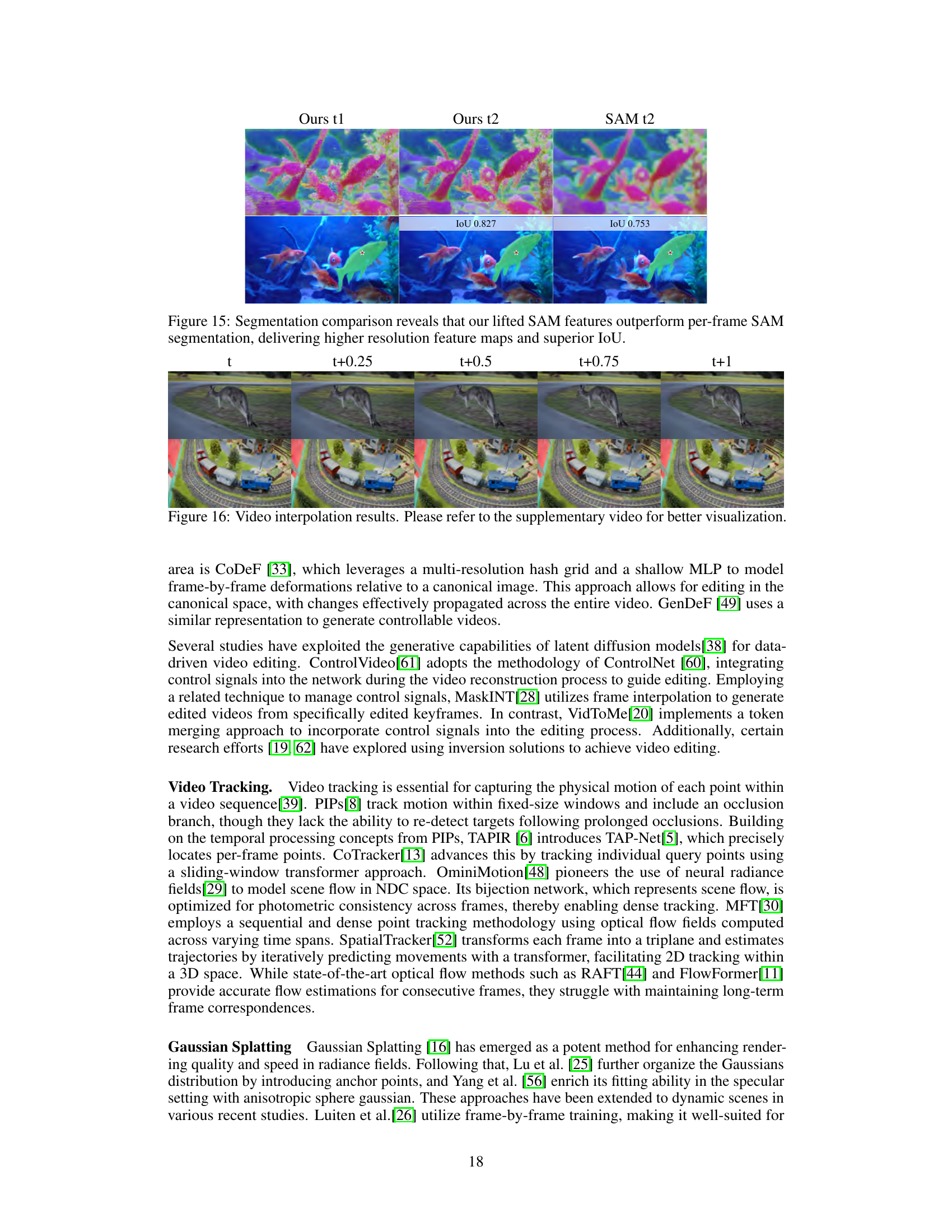

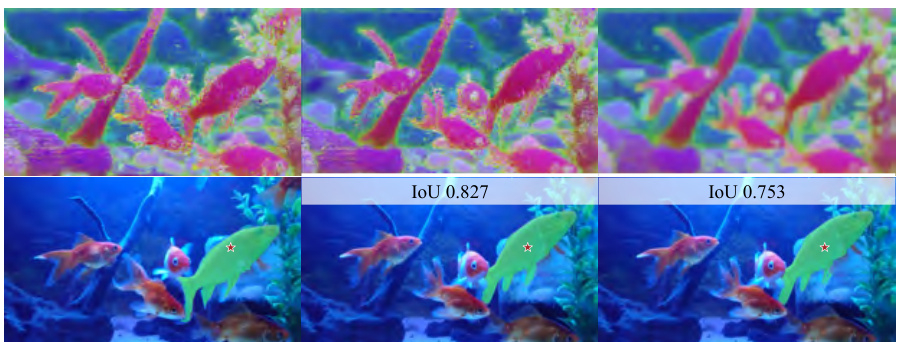

This figure compares the segmentation results obtained using the proposed method’s lifted SAM features against those obtained using per-frame SAM features. The results demonstrate that the proposed method’s lifted SAM features yield higher-resolution feature maps and achieve a significantly superior Intersection over Union (IoU) score, indicating improved segmentation accuracy and detail.

This figure shows the video interpolation results for two example video clips. The top row shows a kangaroo jumping over a road, and the bottom row shows a train moving around a circular track. In both cases, intermediate frames are generated at t+0.25, t+0.5, t+0.75 between the original frames (t) and the final frame (t+1), demonstrating the smooth interpolation achieved by the proposed method.

This figure demonstrates the capabilities of the proposed Video Gaussian Representation (VGR) for multi-object editing in videos. The top row shows geometry editing: two individuals are selected and their positions and poses are modified. The bottom row showcases appearance editing: text is added to the video. This illustrates the model’s ability to handle complex editing tasks that require understanding and manipulating both appearance and motion of multiple objects.

More on tables

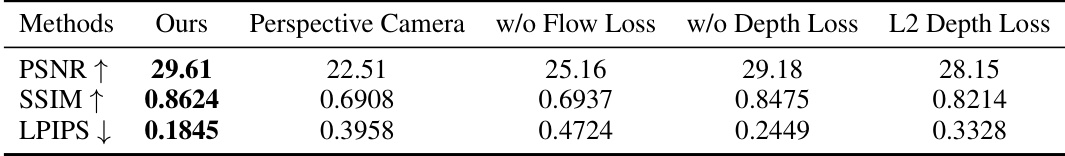

This table presents the ablation study results, comparing the performance of the proposed method (Ours) against variations where different modules are removed. Specifically, it shows the impact of using a perspective camera instead of the proposed orthographic camera, removing the flow loss, removing the depth loss, and using a different depth loss function (L2 loss instead of the scale and shift trimmed loss). The results are evaluated using PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS metrics to assess the quality of the video reconstruction.

This table shows the learning rates (lr) and annealed learning rates (Annealed lr) used for different attributes of the 3D Gaussians in the model. The attributes include Position, Rotation, Scaling, SH (spherical harmonics), Polynomial, and Fourier coefficients, Segmentation Label, and SAM Feature. Each attribute is optimized using a different learning rate schedule.

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the hyperparameters n and l, which control the flexibility of Gaussian motion trajectories. Different combinations of n and l (polynomial and Fourier coefficients, respectively) were tested to determine their impact on video reconstruction quality. The metrics used to assess performance are PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS. A row labeled ‘w/o’ shows the results when these parameters were omitted, which provides a baseline for comparison.

This table compares the performance of using per-frame SAM features versus the method proposed in the paper. The metrics compared are Intersection over Union (IOU), which measures the accuracy of segmentation, and Times, which represents the processing time. The results show that the proposed method achieves significantly higher IOU with much faster processing speed.

Full paper#