↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Visual Imitation Learning (VIL) empowers robots to learn new skills by observing human demonstrations. However, existing VIL methods struggle to learn fine-grained actions and generalize to unseen environments, often relying on pre-defined motion primitives. This limitation stems from the difficulty in accurately recognizing and understanding low-level actions from human videos, and from the inherent redundancy in motion signals that hinders effective learning.

VLMimic tackles these challenges using Vision-Language Models (VLMs) to directly learn even fine-grained actions from a limited number of human videos. It introduces a human-object interaction grounding module to parse human actions into segments, hierarchical constraint representations to effectively represent motion signals, and an iterative comparison strategy to adapt skills to novel scenes. Experiments demonstrate significant improvement over baselines on several challenging manipulation tasks, showcasing VLMimic’s efficiency and robustness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in robotics and AI, especially those working on visual imitation learning. It presents VLMimic, a novel framework that significantly improves the ability of robots to learn complex, fine-grained actions from limited human demonstrations. This addresses a major bottleneck in current VIL methods and opens new avenues for research in efficient skill acquisition and generalization. The real-world results demonstrate its potential for practical applications.

Visual Insights#

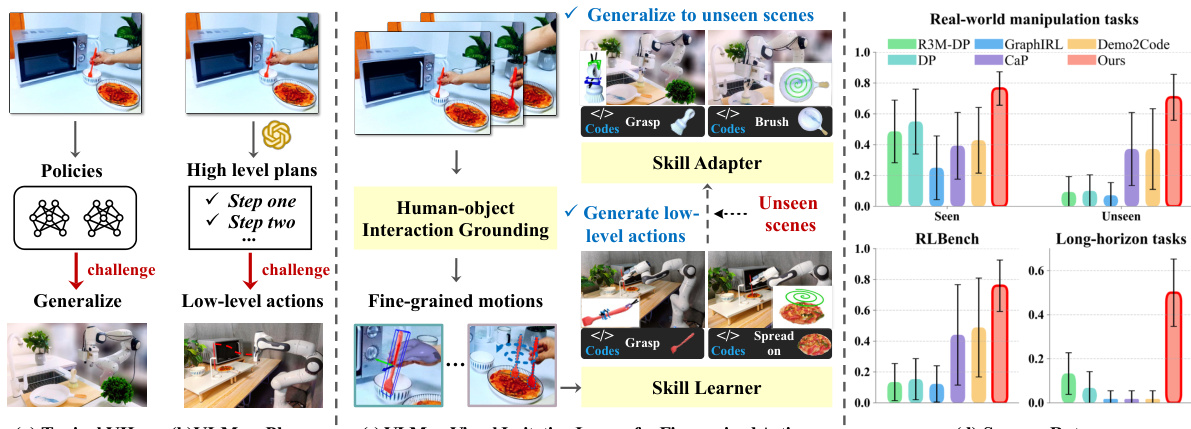

This figure illustrates the core idea of the VLMimic framework by contrasting it with traditional VIL methods and VLM-based planning approaches. Panel (a) shows that typical VIL methods struggle to generalize to unseen environments, highlighting the limitations of learning from limited data. Panel (b) demonstrates how current methods, which use VLMs as high-level planners, encounter challenges in generating the low-level actions necessary for robot control. Panel (c) presents the VLMimic method, which directly learns fine-grained actions from human videos using a skill learner and skill adapter. The skill learner extracts object-centric movements and learns skills with fine-grained actions from human videos, while the skill adapter helps generalize to unseen environments. Finally, panel (d) shows the superior performance of VLMimic compared to other methods using limited human video data.

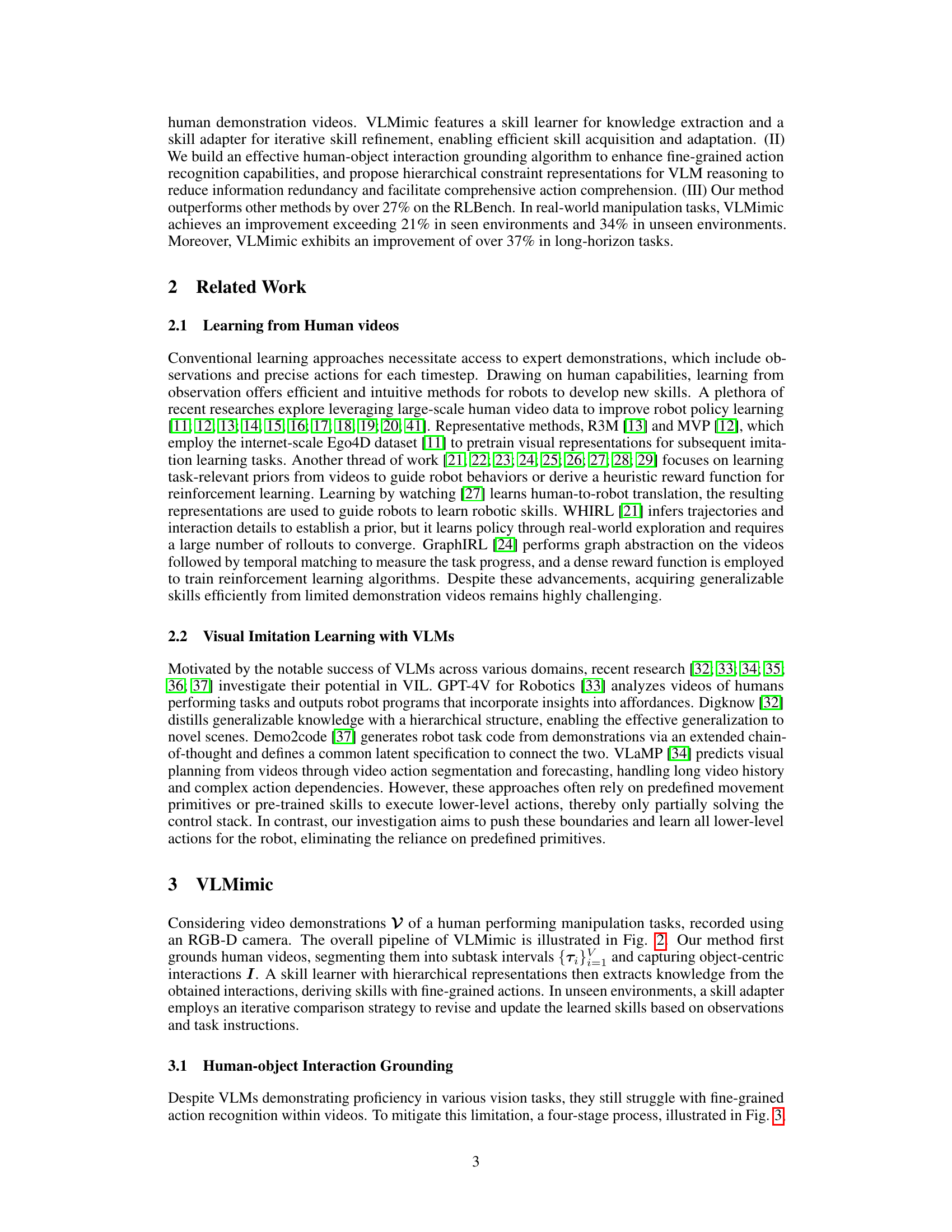

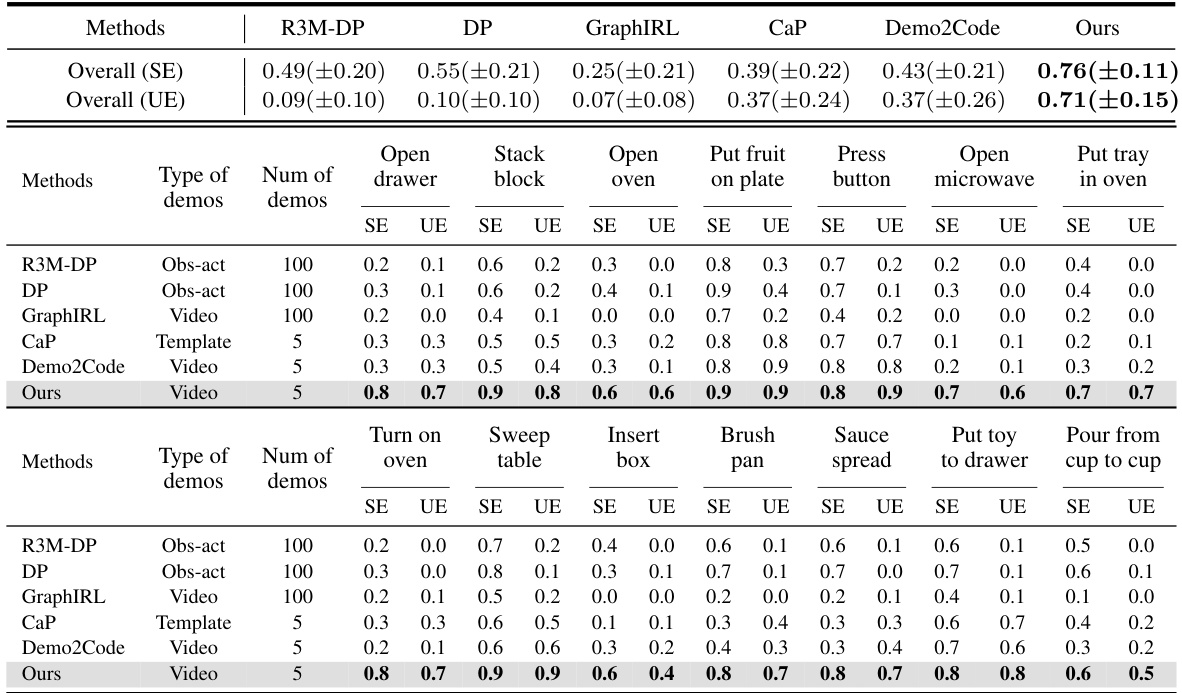

This table presents the success rates of different methods on RLBench, a benchmark for robotic manipulation tasks. The success rate is shown for 12 different tasks across three categories: reaching, picking up, and opening. The methods are compared based on the type of demonstrations used (paired observation-action sequences, code templates, or videos) and the number of demonstrations. The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed method (Ours) which achieves significantly higher success rates using only 5 videos compared to other methods that utilize much larger datasets.

In-depth insights#

VLMimic Framework#

The VLMimic framework presents a novel approach to visual imitation learning (VIL) by leveraging the power of Vision Language Models (VLMs). Instead of relying on pre-defined motion primitives, a common limitation in current VIL methods, VLMimic directly learns fine-grained actions from limited human video demonstrations. This is achieved through a multi-stage process involving human-object interaction grounding, which parses videos into meaningful segments and identifies object-centric movements. A skill learner then utilizes hierarchical constraint representations to extract knowledge from these movements, creating skills with fine-grained actions. Finally, a skill adapter refines and generalizes these skills through iterative comparison, adapting to unseen environments. This hierarchical approach, combining high-level semantic understanding with low-level geometric details, allows VLMimic to achieve remarkable performance, surpassing existing methods by significant margins on various benchmark tasks, even with limited training data. The framework demonstrates the potential of VLMs to significantly advance the field of VIL by directly tackling the challenging problem of fine-grained action learning and generalization.

Hierarchical Constraints#

The concept of “Hierarchical Constraints” in the context of robotics and visual imitation learning suggests a structured approach to representing and reasoning about actions. It likely involves breaking down complex actions into smaller, manageable sub-actions or constraints, organized in a hierarchy. Higher-level constraints could define overall goals or task objectives, while lower-level constraints might specify details of the sub-actions, such as geometric relationships between objects and end-effectors or semantic properties of movements (e.g., “grasp gently,” “rotate quickly”). This hierarchical structure allows for more robust and efficient learning, as the model can reason about actions at different levels of abstraction. It also promotes generalization to unseen scenarios by learning relationships between constraints rather than memorizing specific sequences of actions. By decoupling high-level goals from low-level execution details, the model can adapt to variations in the environment or object properties while maintaining the overall task objective. A key benefit would be efficient skill acquisition from limited data, enabling robots to learn complex skills from a smaller number of demonstrations by learning the underlying relationships between constraints instead of the full action sequence.

Iterative Skill Adapt.#

The heading ‘Iterative Skill Adapt.’ suggests a method for refining learned robotic skills over time. This likely involves a feedback loop where the robot’s performance is evaluated, and adjustments are made to the underlying skill representation. The iterative nature emphasizes a process of continuous improvement, rather than a one-time learning phase. This approach likely addresses the challenge of generalization to new environments or tasks by allowing the robot to adapt its skills based on real-world experience. Successful implementation would require mechanisms for detecting performance shortcomings and a method for updating the skill model. A key challenge would be to balance adaptability with stability, preventing catastrophic changes to skills. Effective approaches might involve incremental adjustments, prioritizing robustness over rapid improvement. The process might leverage various learning algorithms to facilitate adaptation, possibly integrating knowledge representation schemes for efficient skill updates. The ultimate goal is likely to create robust and generalizable robotic skills that perform reliably across various conditions.

Real-World Results#

A thorough analysis of a research paper’s “Real-World Results” section should delve into the experimental setup, providing specifics on the robots, environments, and tasks involved. It’s crucial to understand how the real-world settings compare to simulations, acknowledging any discrepancies or limitations. Success metrics, beyond simple success/failure rates, should be examined, noting the quantitative and qualitative aspects of performance. A detailed examination of the results should compare the proposed method against established baselines, emphasizing the magnitude and statistical significance of any improvements. Generalization capabilities should be thoroughly assessed, evaluating performance on unseen tasks or environments. The discussion should also cover the robustness of the system to variations like different viewpoints or environmental noise. Finally, a critical evaluation would analyze any observed failures and explore potential explanations, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the approach’s strengths and limitations in real-world applications.

Future of VLMimic#

The future of VLMimic hinges on addressing its current limitations and capitalizing on its strengths. Improving the efficiency of the VLMimic framework is crucial, particularly reducing inference latency and computational resource demands. This might involve exploring more efficient VLMs or optimizing the existing architecture. Expanding the dataset of human demonstrations will significantly enhance the model’s generalization capabilities and robustness to unseen environments and tasks. Addressing failure reasoning is also key; incorporating more comprehensive environmental modeling and robust error recovery strategies will improve reliability. Integration with advanced robotic control techniques beyond simple primitives will enable complex, multi-step tasks. Further research could investigate incorporating self-supervised learning, allowing VLMimic to learn from larger, unlabeled datasets and potentially adapting to diverse robotic platforms with minimal human intervention. Finally, exploring applications beyond robotic manipulation, such as visual control in other domains, could unlock significant value in diverse fields.

More visual insights#

More on figures

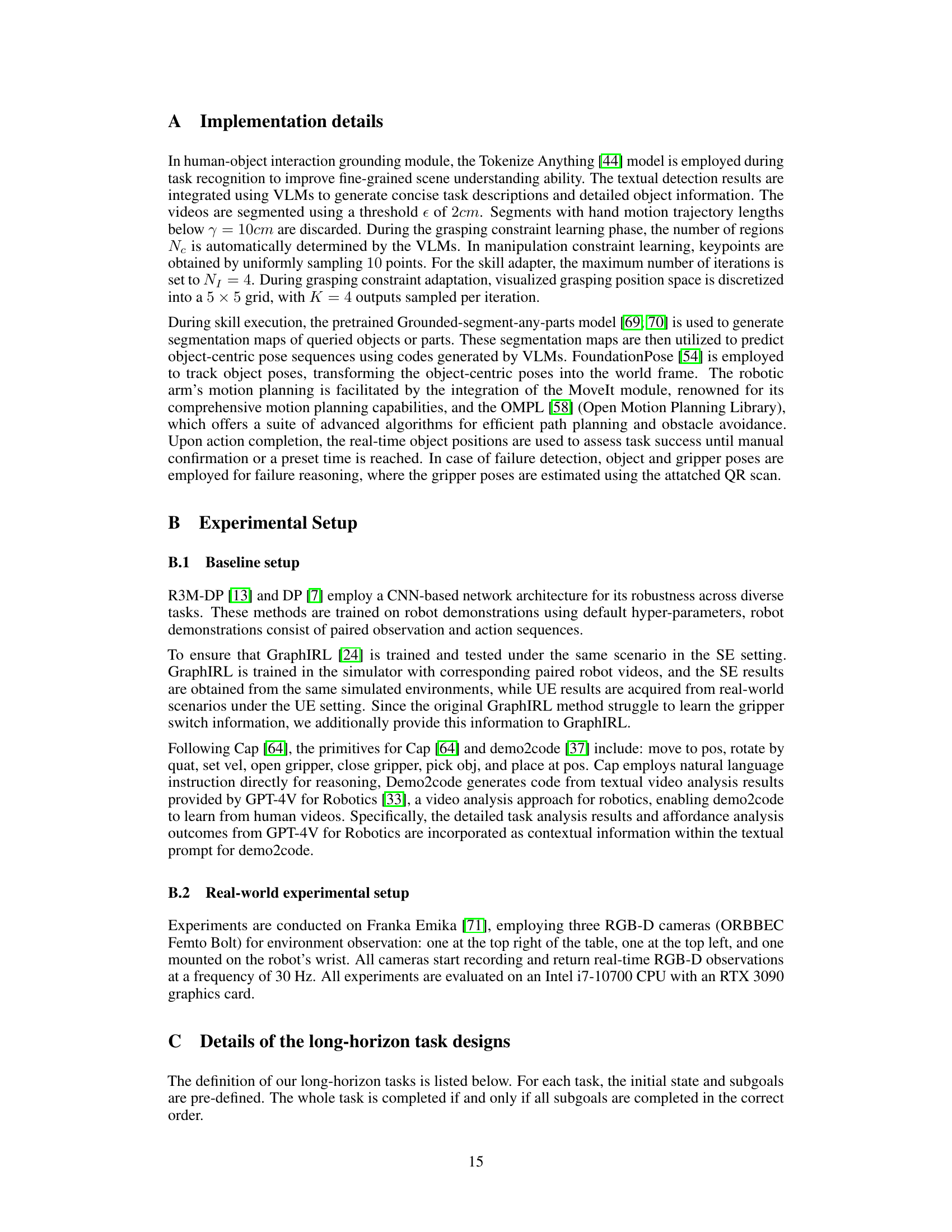

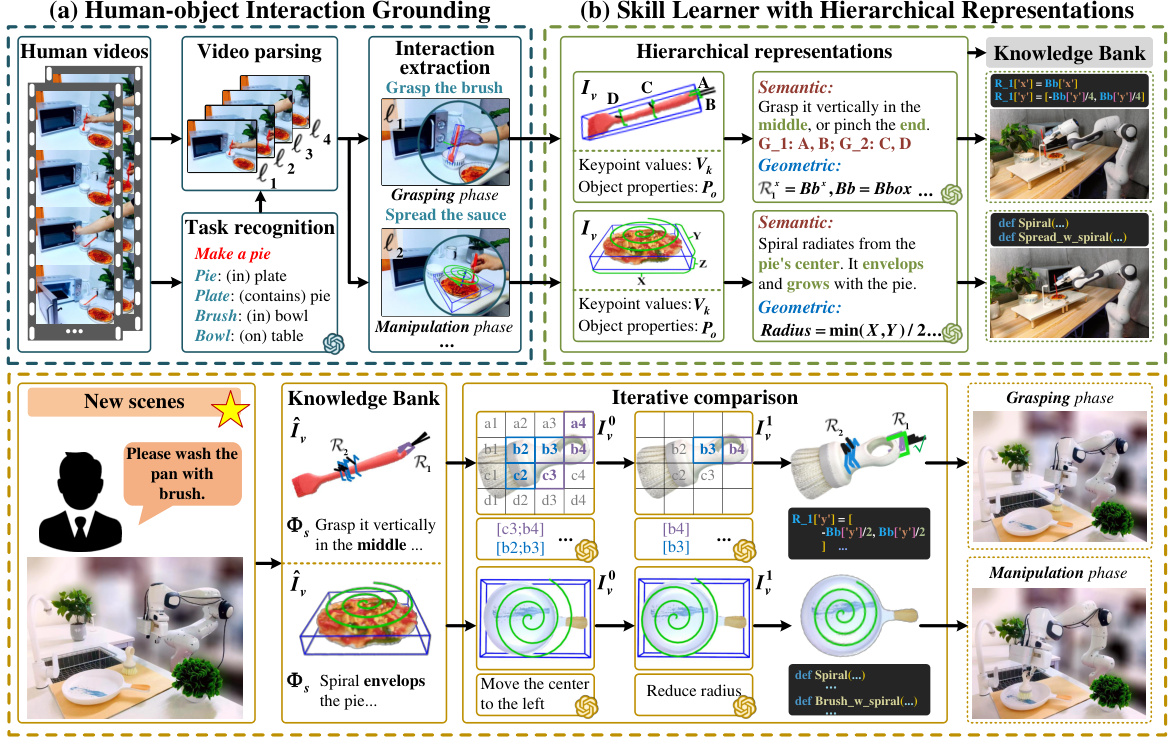

This figure illustrates the three main modules of the VLMimic framework: Human-object interaction grounding, skill learner with hierarchical representation, and skill adapter with iterative comparison. The grounding module processes human demonstration videos to identify object-centric interactions. The skill learner leverages these interactions and hierarchical representations to extract knowledge and generate skills. Finally, the skill adapter updates these skills iteratively in new, unseen environments. This entire process enables VLMimic to generalize robot skills from limited human demonstrations.

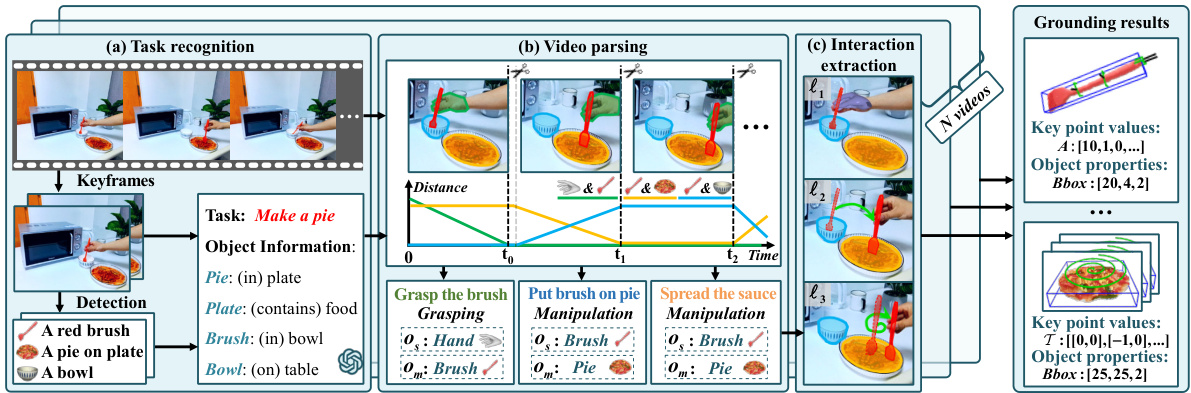

This figure illustrates the three main steps of the Human-object Interaction Grounding module. First, (a) Task Recognition uses keyframes from the video to identify the task and involved objects. Second, (b) Video Parsing segments the video into subtasks using motion trajectories. Finally, (c) Interaction Extraction extracts object-centric interactions for each subtask (e.g., grasping, manipulation). The output provides a structured representation of the human-object interactions in the video, suitable for subsequent skill learning.

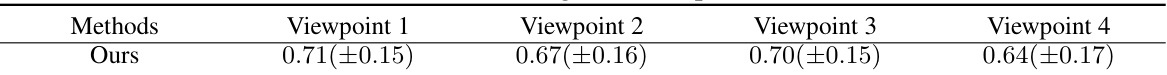

This figure shows four different viewpoints used to test the robustness of the VLMimic approach against changes in perspective. Each image shows the robot arm performing a manipulation task from a different angle. The images illustrate that the method is effective even with shifts in camera position, demonstrating the model’s robustness.

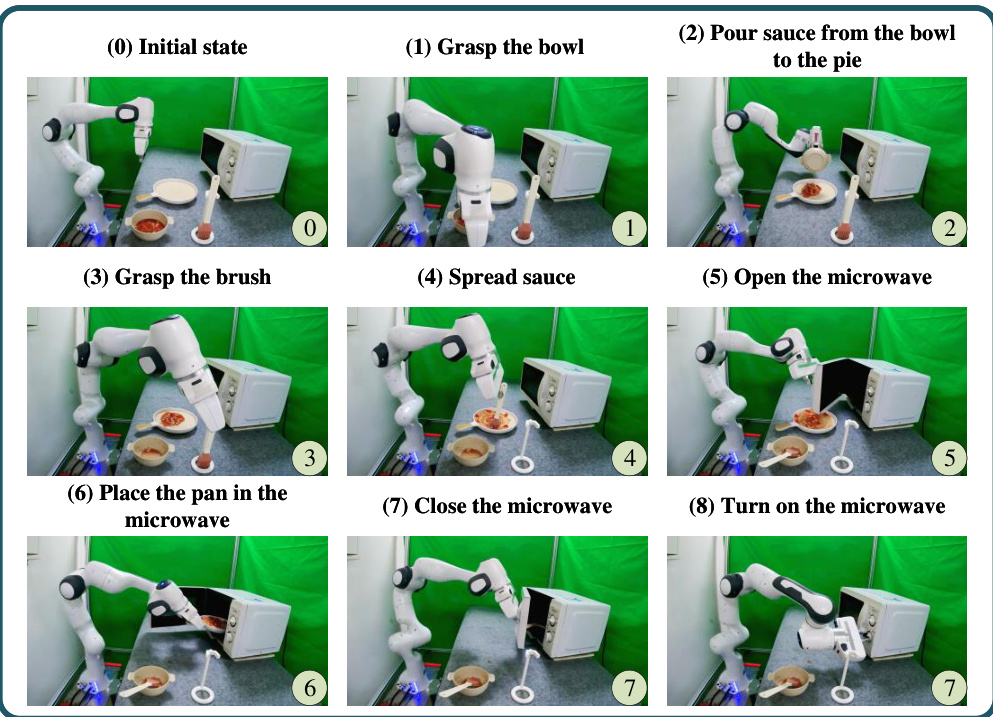

This figure visualizes the steps involved in the ‘make a pie’ task, a subtask within the long-horizon tasks section of the paper. The images show a robotic arm performing each step of the task: (0) initial state, (1) grasping the bowl, (2) pouring sauce onto the pie, (3) grasping the brush, (4) spreading sauce, (5) opening the microwave, (6) placing the pan in the microwave, (7) closing the microwave, and (8) turning on the microwave. This sequence of images demonstrates the fine-grained actions that VLMimic is capable of learning and executing.

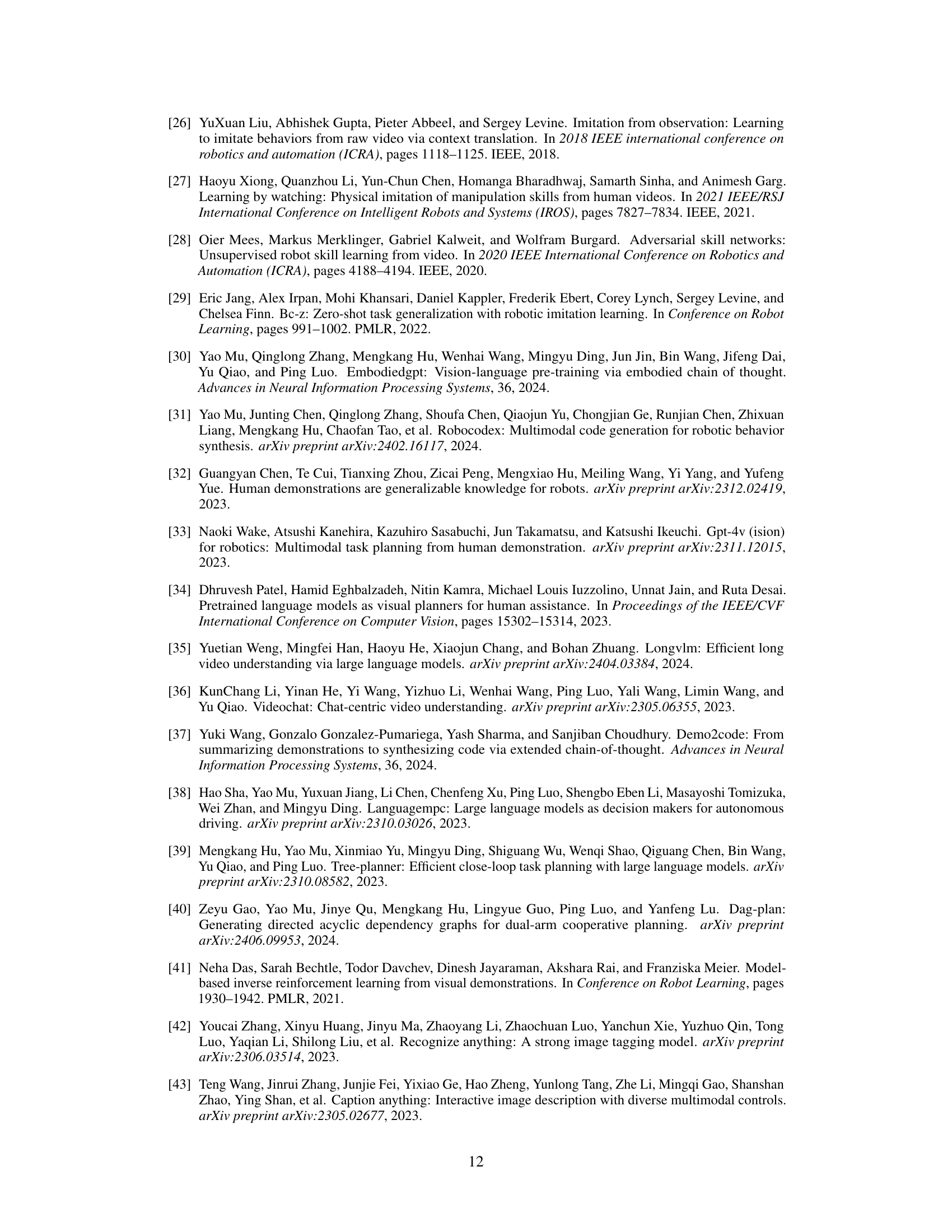

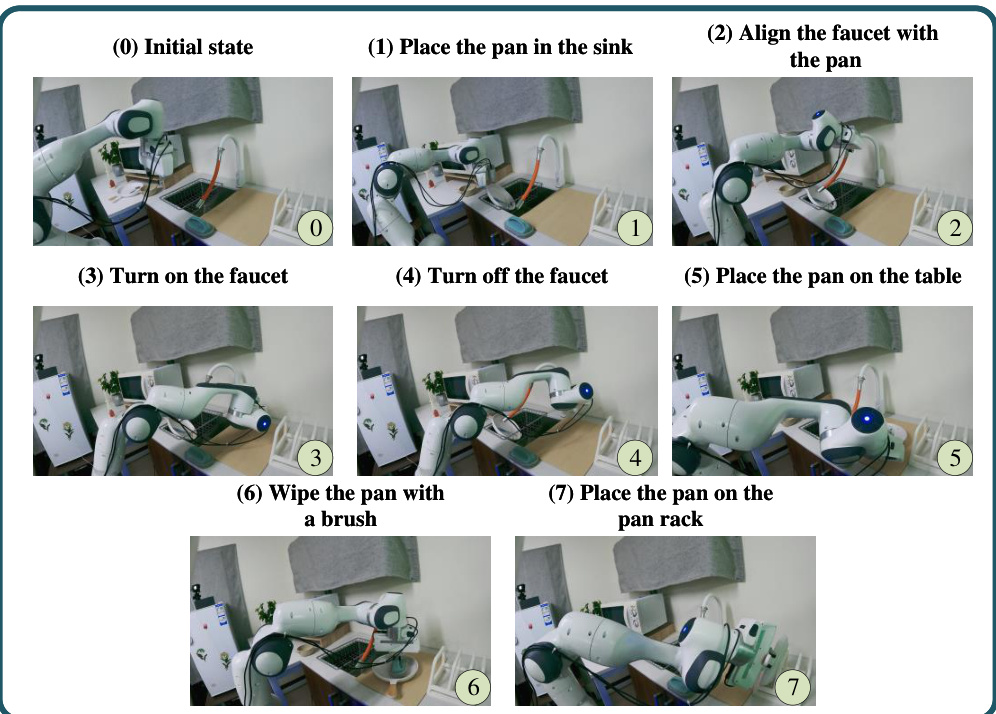

This figure shows a step-by-step visualization of a robot performing the task of washing a pan. It highlights the sequence of actions involved, from initially placing the pan in the sink to the final placement of the washed pan on the rack. Each step is depicted with an image of the robot in the respective pose.

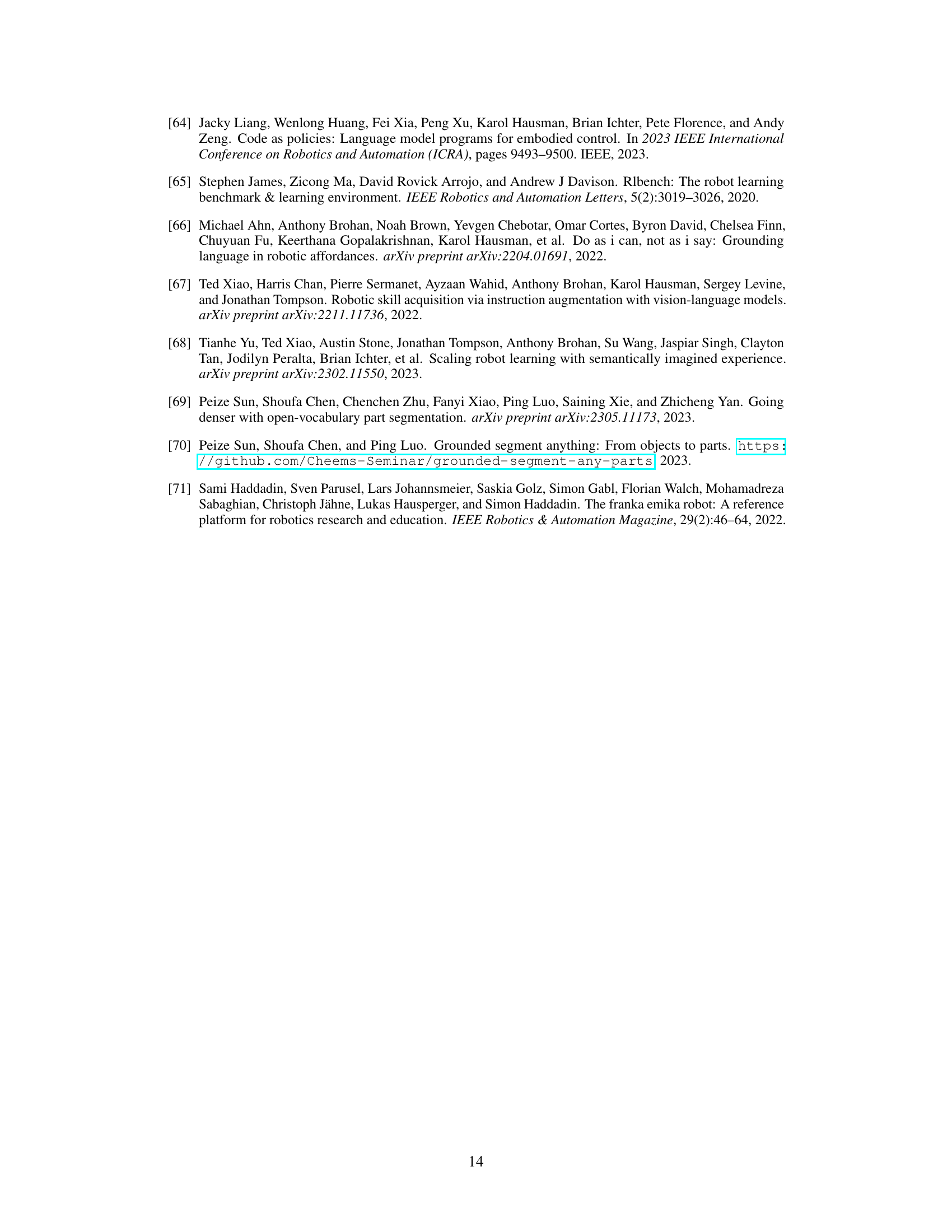

The figure shows a sequence of images illustrating the steps involved in making cucumber slices using a robotic arm. The initial state shows the robot arm, a cucumber in a refrigerator, a cutting board, and a knife. The steps involved are: placing the cutting board on the table, opening the refrigerator, placing the cucumber on the cutting board, closing the refrigerator, removing the knife from the knife rack, cutting the cucumber, and finally placing the knife back in the rack.

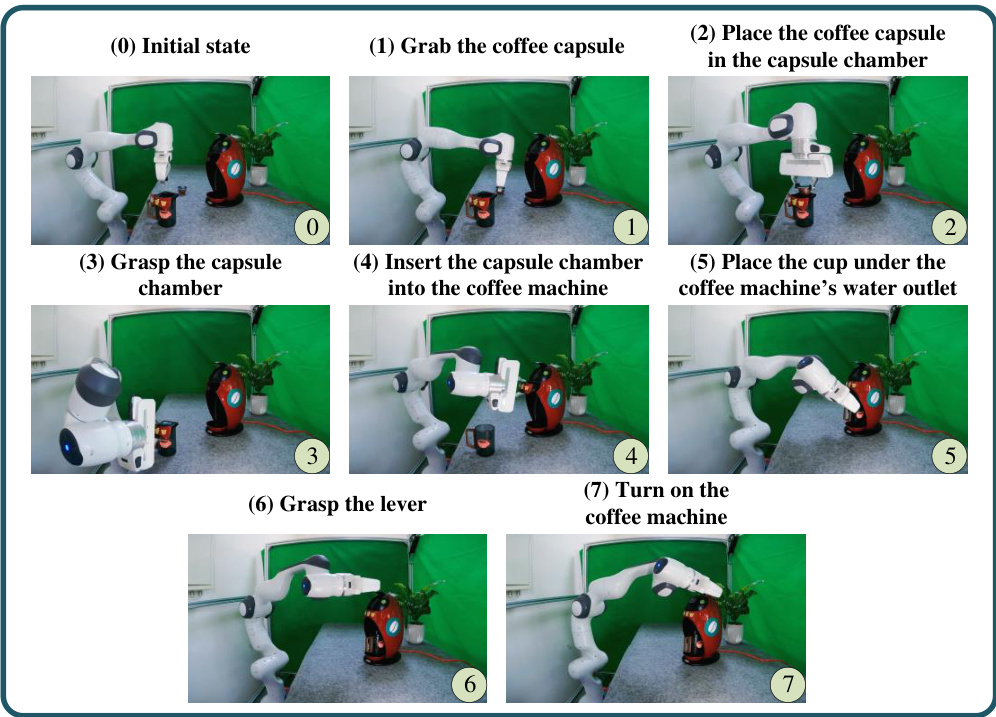

This figure shows a step-by-step visualization of the robot performing the ‘Make Coffee’ task. It highlights the sequence of actions involved, from grasping the coffee capsule to turning on the coffee machine. Each step is illustrated with a separate image, providing a clear visual representation of the task’s sub-goals.

The figure shows a sequence of images illustrating the steps involved in the ‘Clean table’ task. The task involves cleaning up a table with several items scattered on it, such as fruits, cups, and brushes. The robot arm performs a series of actions to put these items back into designated places (e.g., a plate, drawer) and then sweeps the table with a dust brush. The images depict the robot arm manipulating the items and completing the steps sequentially.

This figure visualizes the steps involved in a chemistry experiment task. The initial setup shows a test tube, two beakers, two conical flasks, and a funnel on a retort stand. The steps shown depict the robot manipulating these items: pouring liquids between containers, shaking a flask, and using a funnel. Each sub-figure corresponds to a subtask in a longer sequence of actions required to complete the experiment.

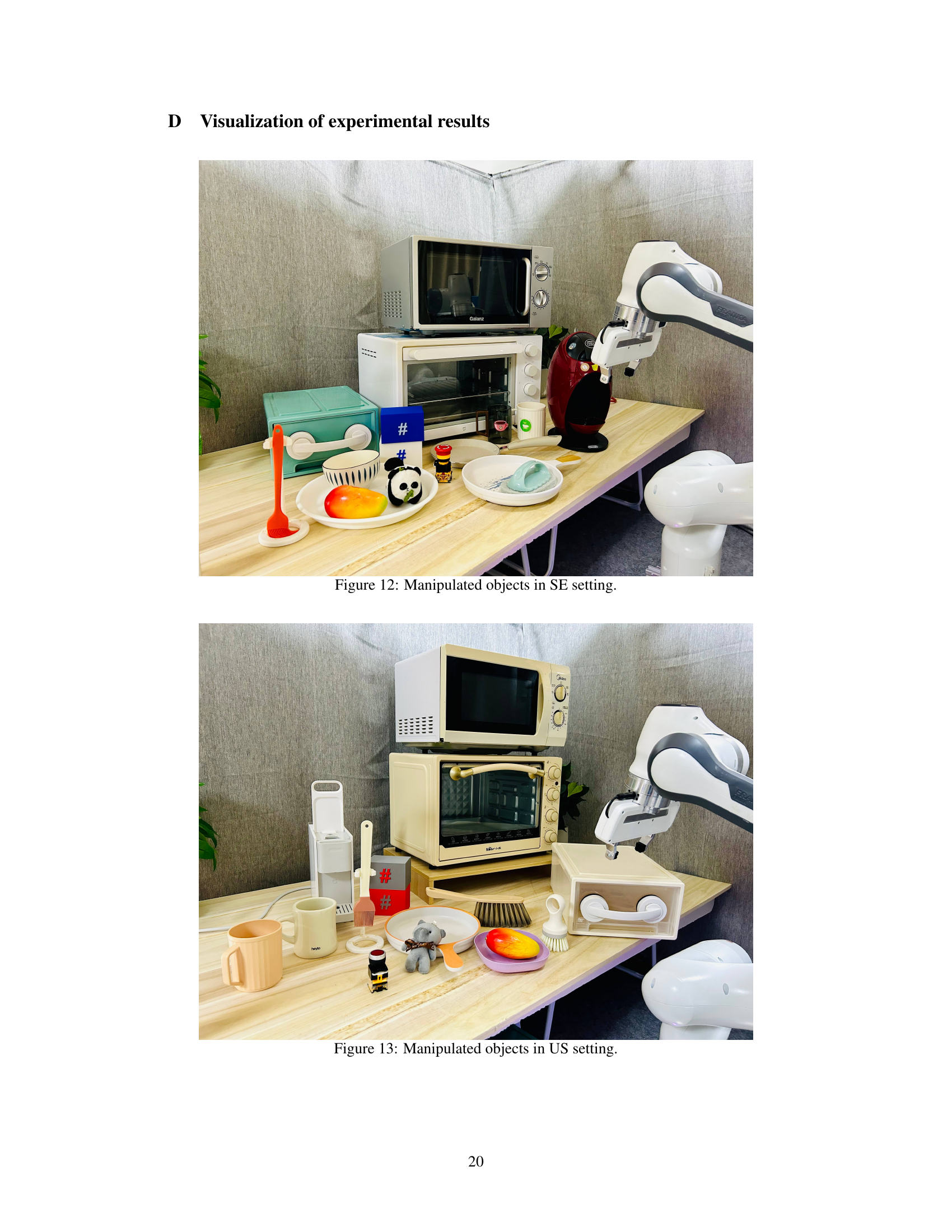

This figure shows the objects used in the seen environment (SE) experiments for the VLMimic robotic manipulation tasks. The image depicts various kitchen and household items arranged on a table, including a microwave oven, a toaster oven, a coffee machine, bowls, cups, plates, utensils, and fruits. The Franka Emika robot arm is also visible, positioned to interact with the objects. The scene demonstrates a setup for testing the robot’s manipulation abilities in a familiar environment.

This figure shows the various objects used in the unseen environment (US) experiments for real-world manipulation tasks. It provides a visual representation of the setup, illustrating the complexity and diversity of objects the robot had to interact with during testing. The image shows a variety of everyday household items arranged on a table, including a microwave, oven, containers, and various tools, demonstrating the challenges of generalizing to unseen environments.

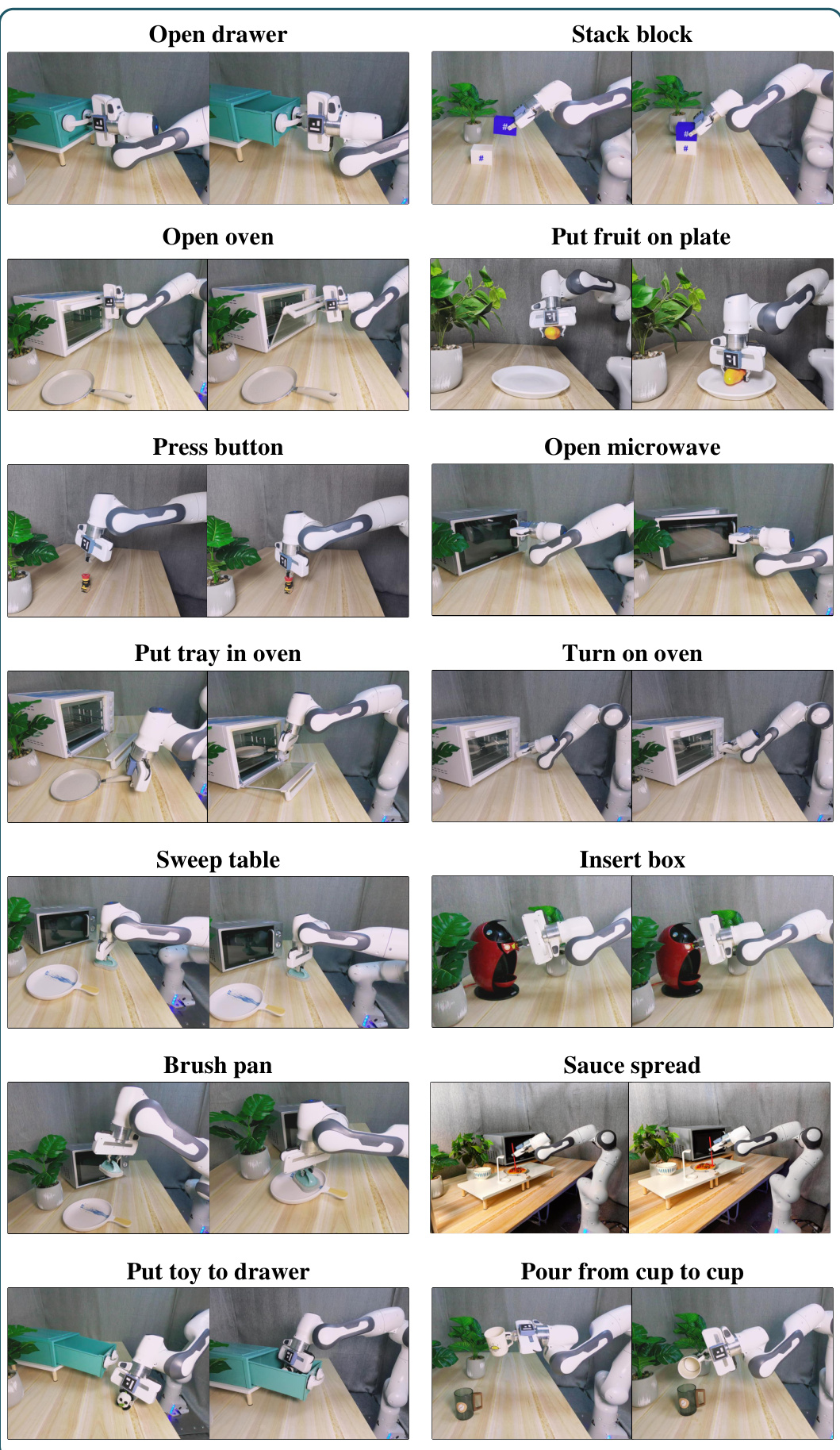

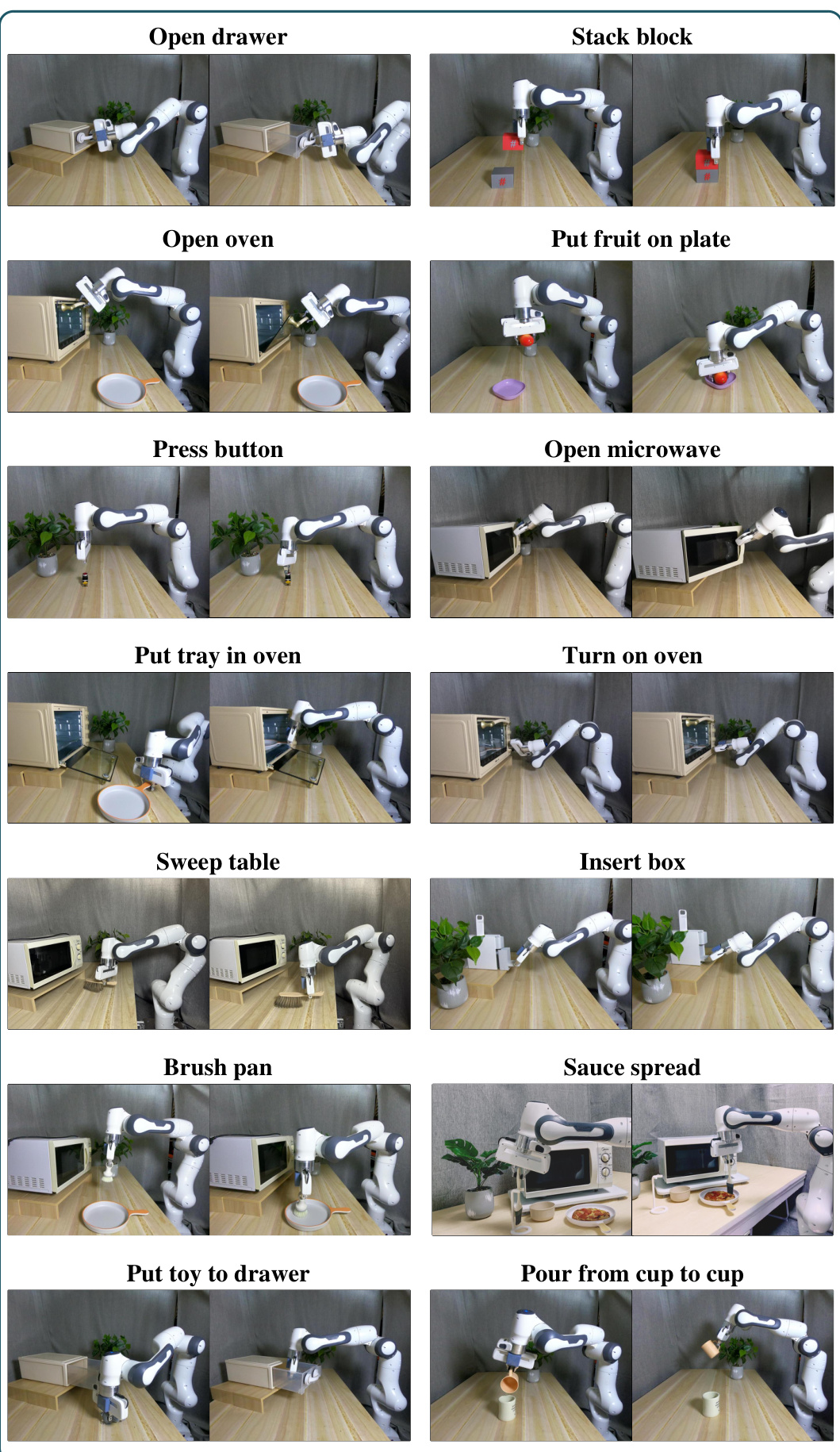

This figure shows the results of 14 manipulation tasks performed by the robot in unseen environments. Each task is shown in a pair of images, with the left image showing the initial state and the right image showing the final state after the robot has completed the task. The tasks involve a range of actions, such as opening drawers and ovens, putting objects on plates, brushing pans, and pouring liquids. The figure demonstrates the ability of the VLMimic model to generalize to unseen environments, successfully completing the tasks despite the differences in the environments and objects.

This figure shows the results of various manipulation tasks performed by a robot in unseen environments. The tasks are visually depicted, showing the robot interacting with different objects and completing tasks like opening drawers, stacking blocks, and pouring liquids. The images provide a visual representation of the robot’s successful execution of these manipulation tasks in settings it has not previously encountered, showcasing the generalization capabilities of the proposed VLMimic approach.

More on tables

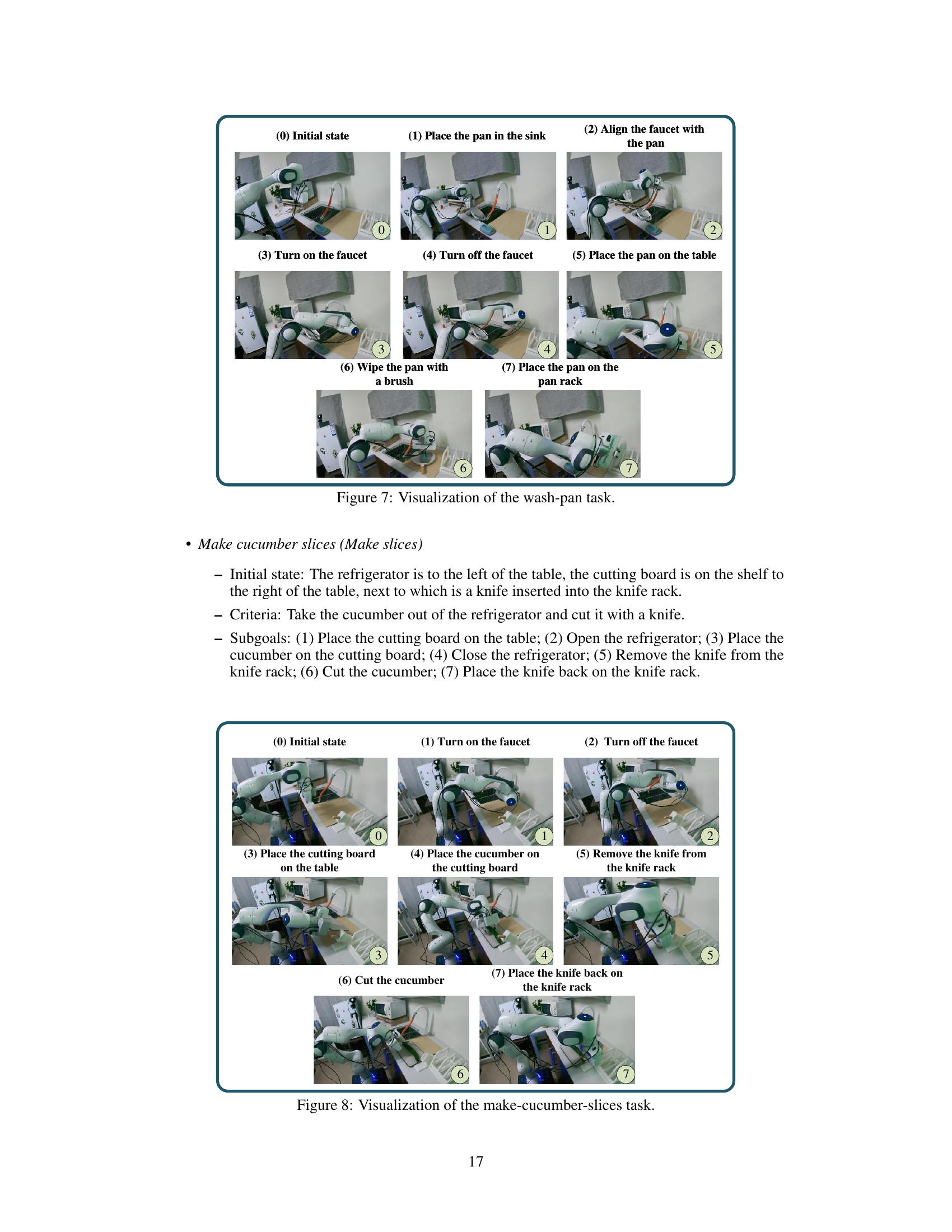

This table presents the success rates of different methods on real-world manipulation tasks. It compares the performance of several algorithms (R3M-DP, DP, GraphIRL, CaP, Demo2Code, and the proposed method, Ours) across 14 tasks in both seen (SE) and unseen (UE) environments. The ‘Type of demos’ column indicates whether the method uses observation-action pairs, code templates, or videos for demonstration. The ‘Num of demos’ column specifies the number of demonstrations used by each method. The remaining columns show the success rates (with standard deviations) for each task in each environment.

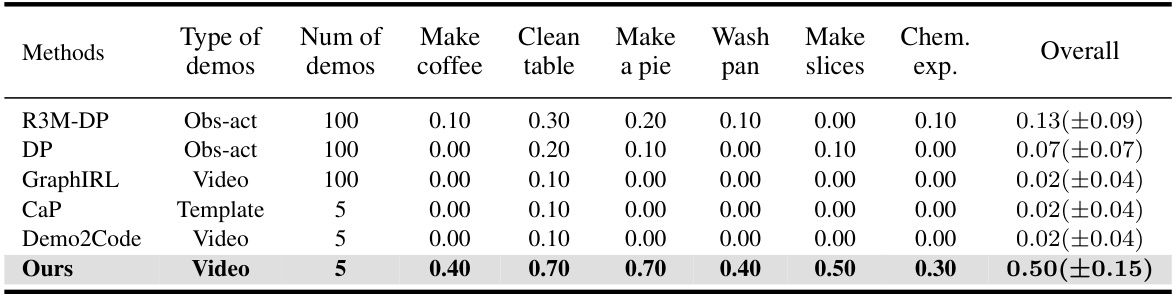

This table presents the success rates of different methods on six long-horizon tasks. The methods are compared using three types of demonstrations: paired observation-action sequences (Obs-act), code templates (Template), and videos (Video). The table shows that the proposed method (‘Ours’) significantly outperforms the baseline methods in all tasks, demonstrating its effectiveness on long-horizon tasks.

This table presents the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the robustness of the VLMimic model against variations in viewpoint. The model’s performance (success rate) is measured across four different viewpoints (Viewpoint 1, Viewpoint 2, Viewpoint 3, Viewpoint 4) for a specific task. The standard deviation is included to indicate the variability in performance across multiple trials under each viewpoint.

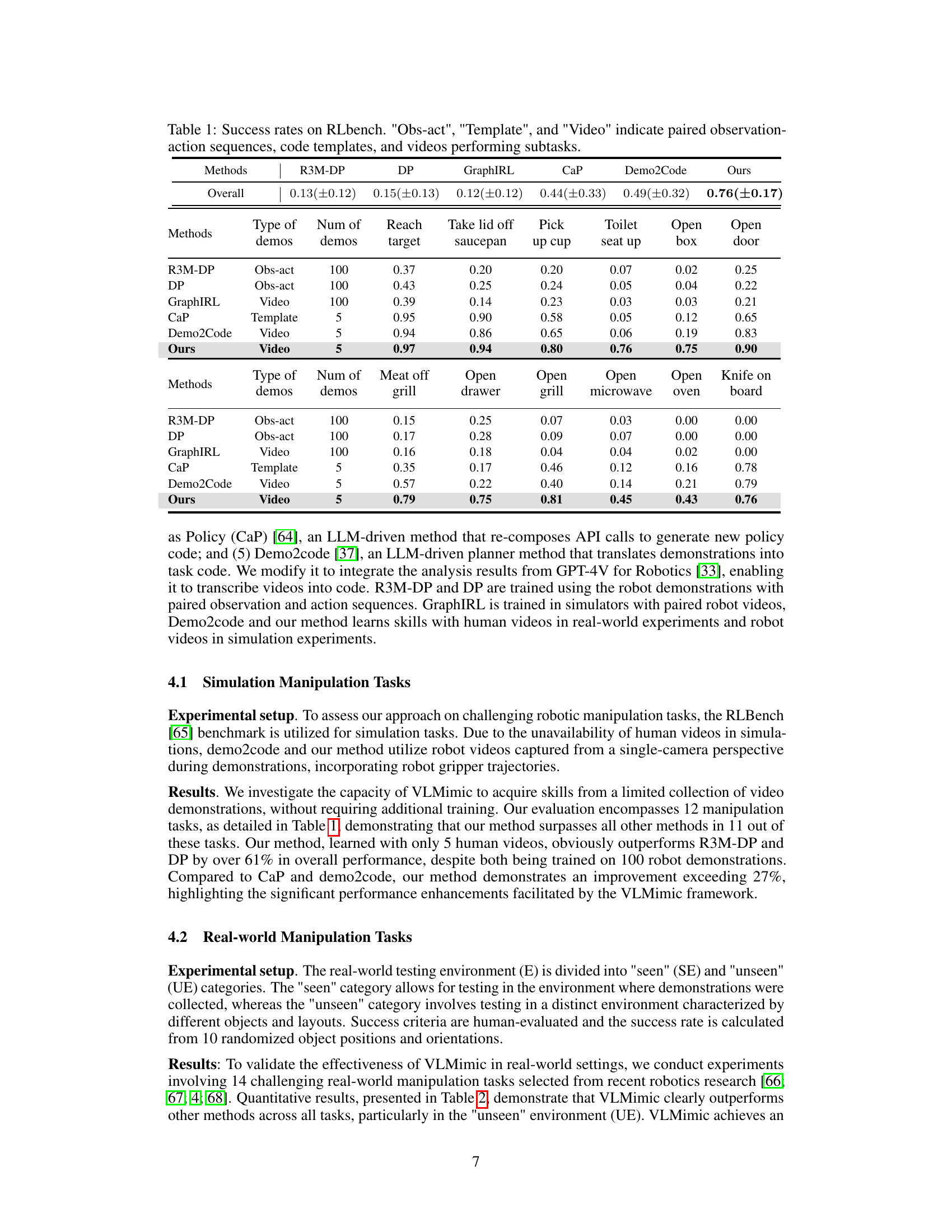

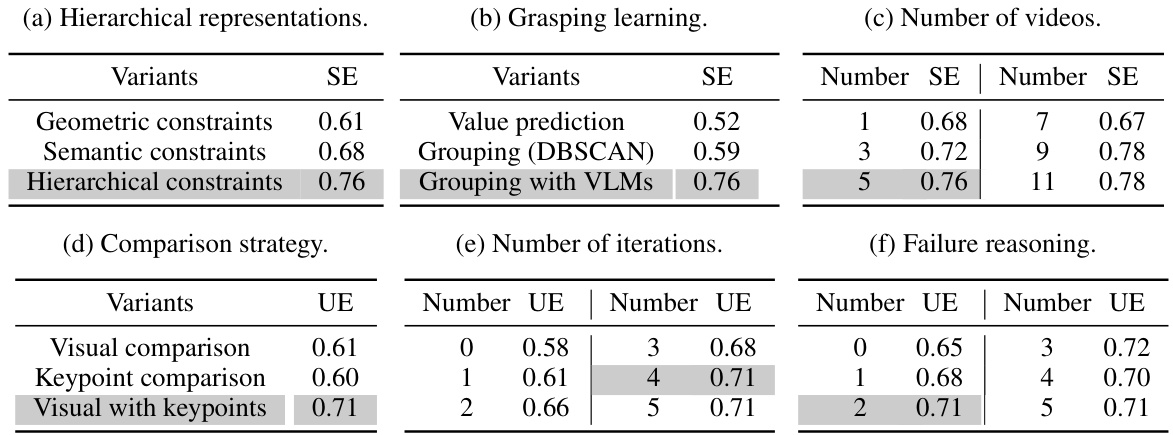

This table presents the ablation study results for the VLMimic model. It shows the impact of different design choices on the model’s performance in both seen and unseen environments. Specifically, it analyzes the effects of using different constraint representations (hierarchical vs. geometric/semantic), grasping learning strategies (value prediction, grouping with DBSCAN, grouping with VLMs), the number of human videos used for training, different comparison strategies in the skill adapter, the number of iterations in the skill adapter, and the use of failure reasoning. The results are expressed as success rates in seen (SE) and unseen (UE) environments.

Full paper#