↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Diffusion models generate high-quality images but suffer from slow inference times, hindering their use in real-time applications. Existing acceleration techniques, like knowledge distillation, demand significant computational resources and retraining. This research directly addresses this issue by focusing on the UNet architecture commonly used in diffusion models.

The core of this paper lies in its empirical analysis of UNet’s encoder and decoder features. The authors discovered that encoder features remain largely consistent across time steps, while decoder features vary significantly. This observation enabled the development of a novel method called “Encoder Propagation”. This technique reuses encoder features from previous time steps, reducing redundant computations, and enabling parallel processing of decoder computations, significantly improving the overall inference speed.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with diffusion models because it offers a novel, computationally efficient method for accelerating inference without retraining. It addresses the major bottleneck of slow inference, opening avenues for real-time applications and broadening the accessibility of diffusion models to resource-constrained settings. The findings challenge existing assumptions about encoder roles and suggest new directions for optimizing diffusion model architectures.

Visual Insights#

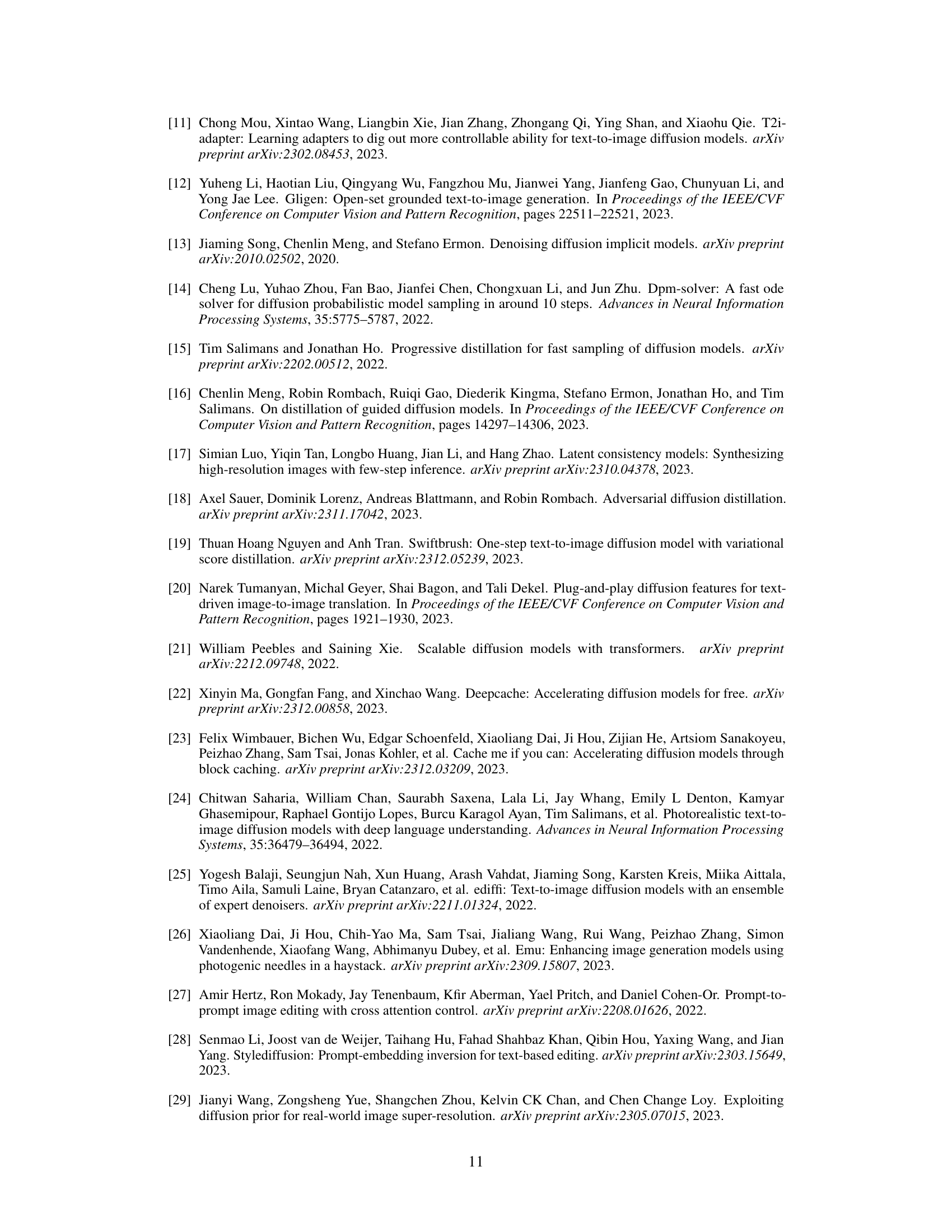

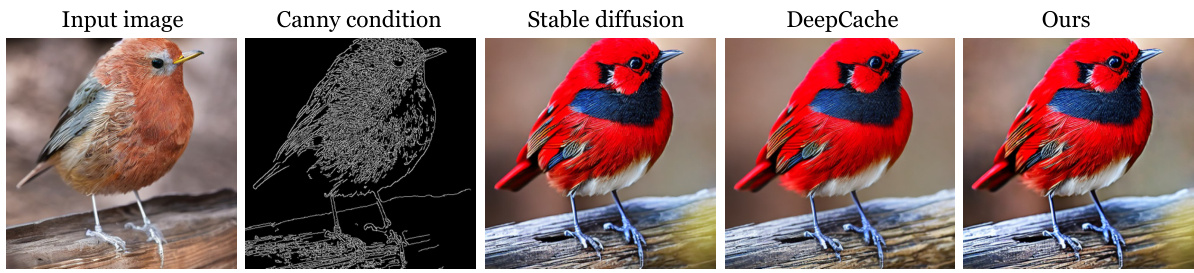

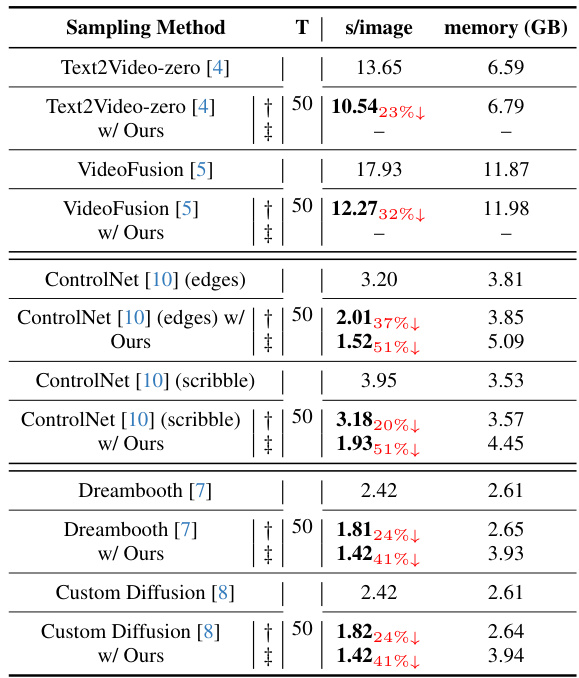

🔼 This figure displays the results of applying the Faster Diffusion method to various image generation tasks, including Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, and ControlNet. For each task, it compares the original inference time with the time achieved after applying the Faster Diffusion method, showing a significant reduction in inference time across all tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

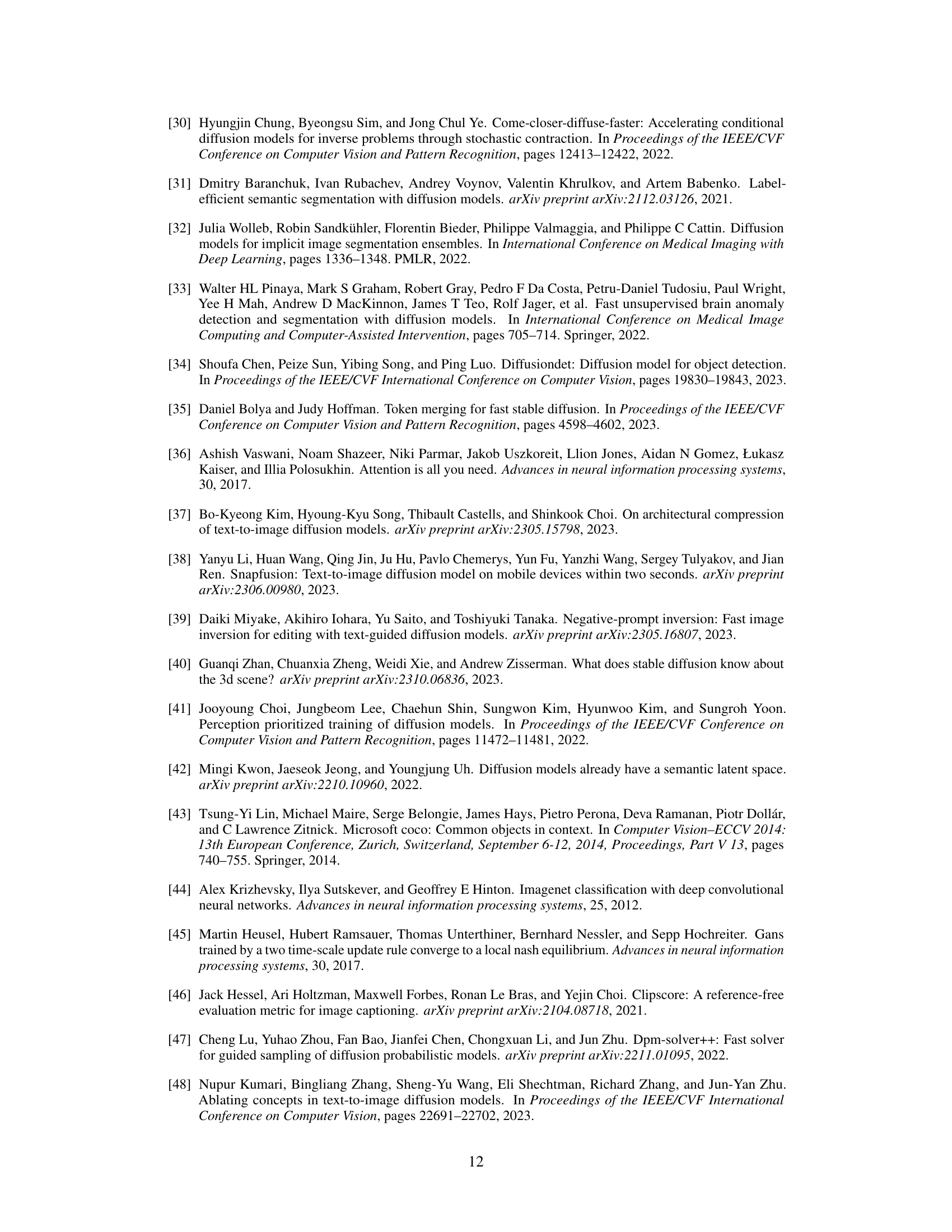

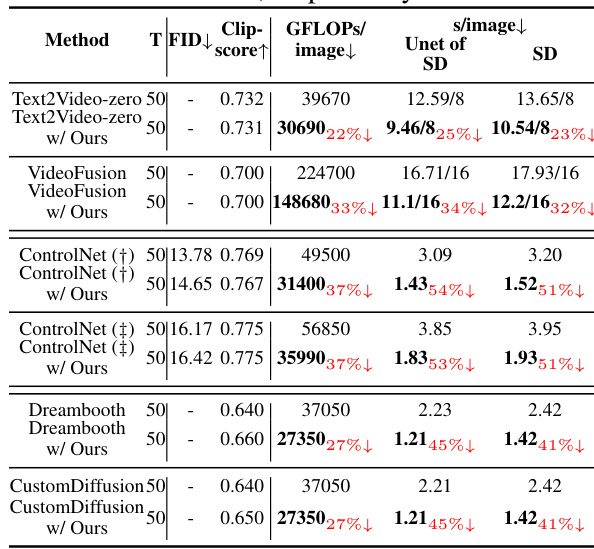

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different sampling methods applied to Stable Diffusion and DeepFloyd-IF models. It shows the sampling time, FID (Fréchet Inception Distance) score, CLIP score, and GFLOPs (giga-floating-point operations) per image for each method. The methods compared include standard DDIM, DDIM with the proposed encoder propagation, DPM-Solver, DPM-Solver with the proposed method, DPM-Solver++, DPM-Solver++ with the proposed method, DDIM + ToMe, DDIM + ToMe with the proposed method, DDPM, and DDPM with the proposed method. Lower sampling time and GFLOPs, as well as higher FID and CLIP scores, indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation for both SD and DeepFloyd-IF diffusion models.

In-depth insights#

Encoder Feature Study#

An encoder feature study within the context of diffusion models would involve a detailed investigation into the characteristics and behavior of the encoder’s output features at different stages of the diffusion process. This would likely include analyzing the evolution of features across time steps, examining their sensitivity to input variations, and determining their importance for downstream decoder operations. A key aspect would be comparing encoder feature behavior with that of the decoder. Significant differences might suggest opportunities for optimization, such as feature reuse or selective encoder computations to accelerate inference, as the encoder’s features often exhibit minimal change, while decoder features vary substantially. By quantifying these differences and exploring their implications for model performance and computational efficiency, such a study could reveal valuable insights for enhancing diffusion models.

Parallel Denoising#

Parallel denoising in diffusion models aims to accelerate the slow inference process inherent in these models. Standard diffusion models rely on a sequential, iterative denoising process, limiting parallelization. The key to parallel denoising lies in identifying aspects of the model’s architecture (like the UNet) that can be computed independently or concurrently. This often involves analyzing the behavior of encoder and decoder features across different timesteps, uncovering redundancies or minimal changes in certain parts of the model that allow for reuse or skipping of calculations. Strategies might focus on the minimal changes in encoder features, leveraging these features for multiple timesteps instead of recomputing, enabling parallel processing in the decoder. Another approach could involve identifying easily parallelizable stages of the iterative process within the decoder itself. Efficient parallel strategies often involve carefully choosing which steps to process in parallel and which to handle sequentially. The balance between maximizing parallelism and preserving generation quality is crucial, requiring careful design and potentially additional techniques like prior noise injection to address potential artifacts introduced by parallelization. Success depends on the ability to significantly decrease the overall inference time without sacrificing the quality of the generated images.

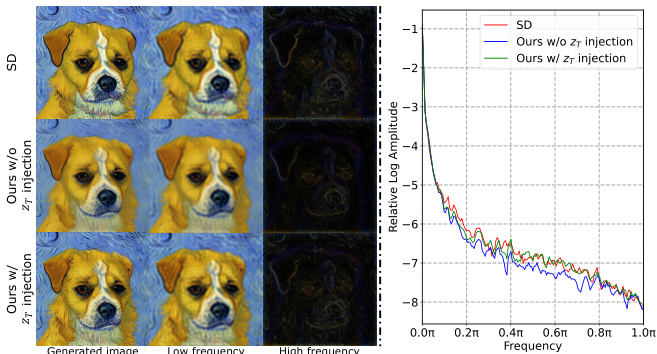

Prior Noise Inject#

The heading ‘Prior Noise Injection’ suggests a technique to enhance the quality of generated images in diffusion models. The core idea is to inject prior noise, likely the initial latent code or a representation of the original input, back into the generation process at specific timesteps. This counteracts a potential drawback of efficient sampling methods, which sometimes compromise image quality by neglecting fine details, especially high-frequency textures. By carefully adding this prior noise, the method aims to preserve crucial texture information that might otherwise be lost during accelerated inference. The injection likely isn’t applied uniformly across all steps; rather, a strategic injection at selective timesteps is anticipated to yield optimal improvements without significantly increasing computational cost. This method would thus serve as a valuable enhancement to other acceleration techniques, potentially resolving the tension between speed and image fidelity common in diffusion model applications. The key success factor of this method lies in finding the optimal balance between the amount of noise injected, the timing of injection, and the preservation of desired image features. This thoughtful approach represents a creative solution for dealing with some of the speed/quality trade-offs that are encountered while accelerating diffusion model sampling.

Ablation Experiments#

Ablation experiments systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a diffusion model, this could involve progressively disabling parts of the UNet architecture (encoder, decoder, skip connections, specific blocks, etc.), or altering the proposed encoder propagation strategy (uniform vs. non-uniform, variations in key time-step selection). Analyzing the impact on metrics like FID and CLIP score reveals the relative importance of each component and the effectiveness of the proposed method. For instance, removing the encoder entirely might show negligible impact on FID, supporting the claim that encoder features are highly reusable, while removing skip connections could lead to significantly degraded image quality. Careful analysis of ablation results is crucial in justifying the claims and demonstrating the strength of the novel acceleration method by showing the impact of each feature on speed and quality. The goal is to demonstrate that the proposed technique is not simply a superficial optimization, but rather significantly leverages the architecture’s inherent properties to achieve robust performance gains.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency of encoder propagation is crucial; current methods might still be computationally expensive for extremely high-resolution images or complex tasks. Further investigation into optimizing the selection of key time steps is needed; a more sophisticated algorithm could significantly boost performance. Research should also focus on extending the applicability of this method to other diffusion model architectures. While the current work focuses on UNet and transformer-based models, exploring its effectiveness on other designs could broaden its impact. Finally, a thorough comparative analysis against various knowledge distillation techniques would provide valuable insights into the relative advantages and limitations of different acceleration strategies. This could help establish the optimal method in various scenarios, potentially combining the strengths of both approaches for superior performance. The overall goal should be to make diffusion models significantly faster and more efficient, thus widening accessibility and spurring innovation across different applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

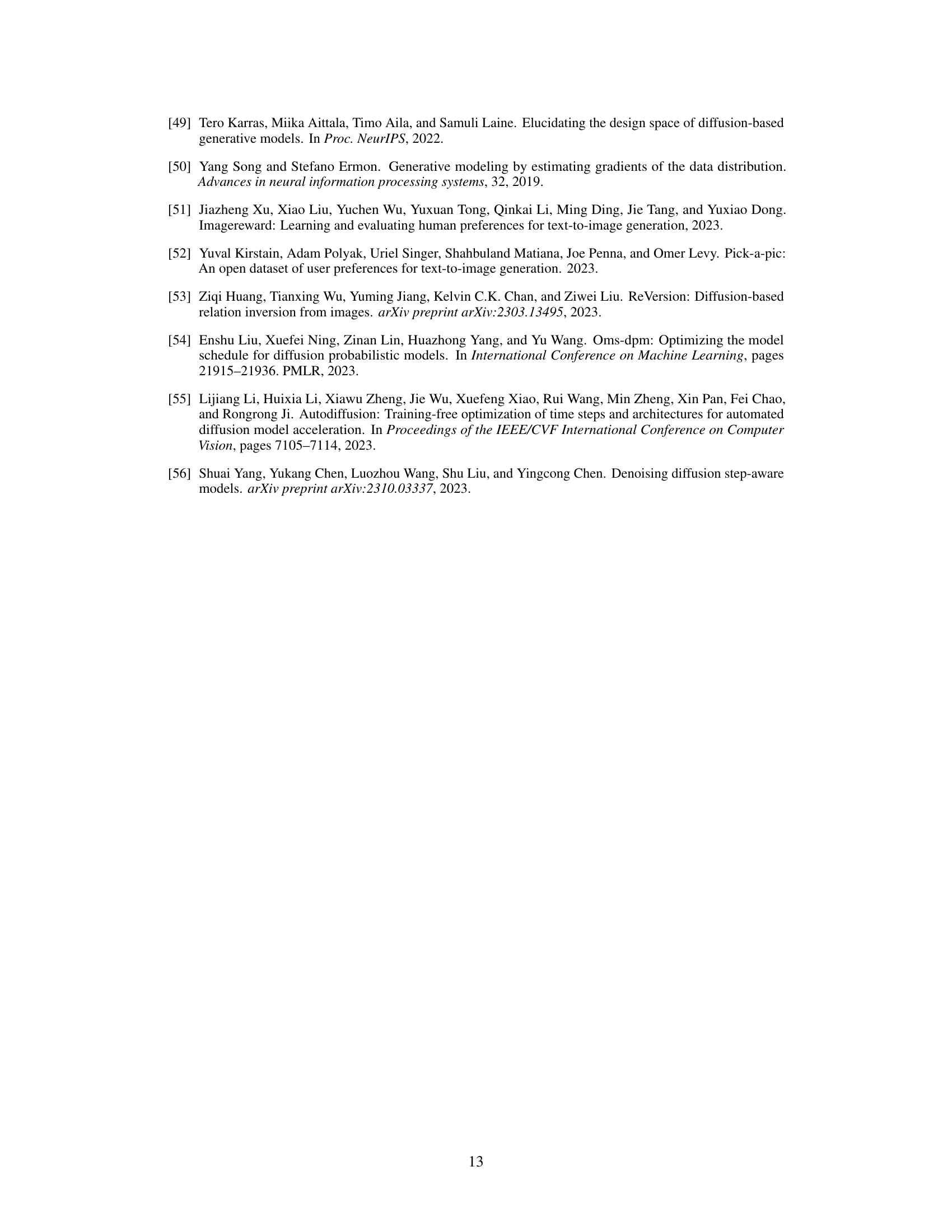

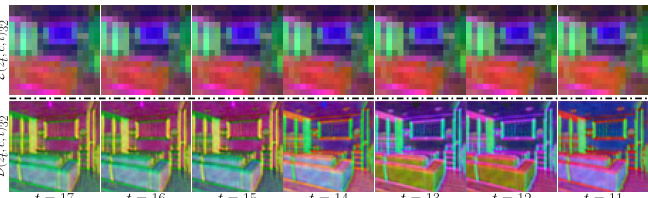

🔼 This figure analyzes the UNet architecture used in diffusion models. It shows that the encoder features change minimally across time steps, while the decoder features exhibit substantial variations. This difference is quantified using Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Frobenius norm. The figure provides evidence that encoder computations can be omitted or reused at certain time steps for acceleration purposes, while preserving model accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 3: Analyzing the UNet in Diffusion Model. (a) Feature evolving across adjacent time-steps is measured by MSE. (b) We extract the hierarchical features output of different layers of the UNet at each time-step, average them along the channel dimension to obtain two-dimensional hierarchical features, and then calculate their Frobenius norm. (c) The hierarchical features of the UNet encoder show a lower standard deviation, while those of the decoder exhibit a higher standard deviation.

🔼 This figure analyzes the UNet architecture used in diffusion models. It shows that the encoder features change minimally across adjacent time steps, while the decoder features change significantly. This analysis is based on the mean squared error (MSE) between adjacent time steps’ features, the Frobenius norm of hierarchical features, and the standard deviation of those norms. The minimal change in encoder features suggests that computational savings can be made by reusing these features across multiple time steps, while the significant variations in decoder features emphasizes the importance of computing these for each step.

read the caption

Figure 3: Analyzing the UNet in Diffusion Model. (a) Feature evolving across adjacent time-steps is measured by MSE. (b) We extract the hierarchical features output of different layers of the UNet at each time-step, average them along the channel dimension to obtain two-dimensional hierarchical features, and then calculate their Frobenius norm. (c) The hierarchical features of the UNet encoder show a lower standard deviation, while those of the decoder exhibit a higher standard deviation.

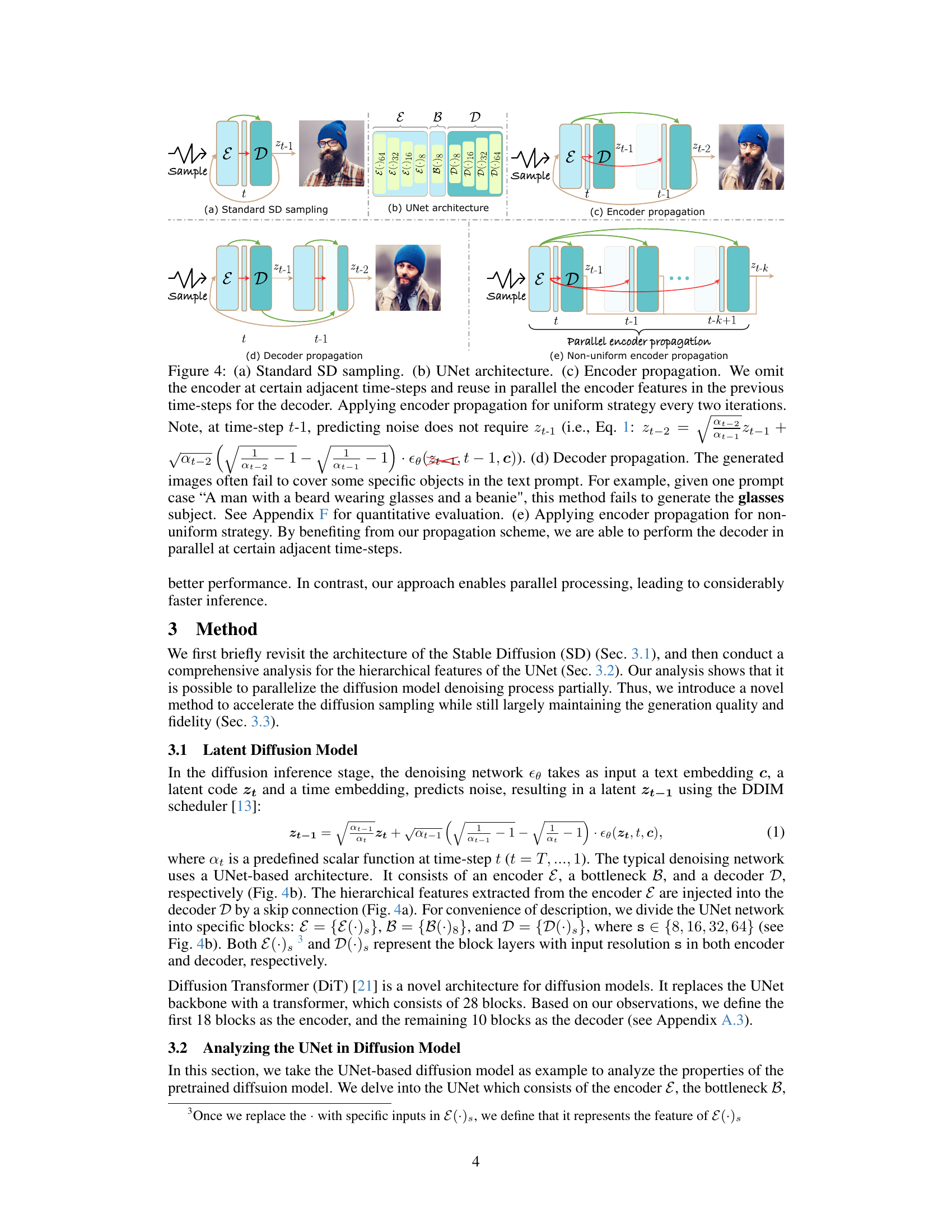

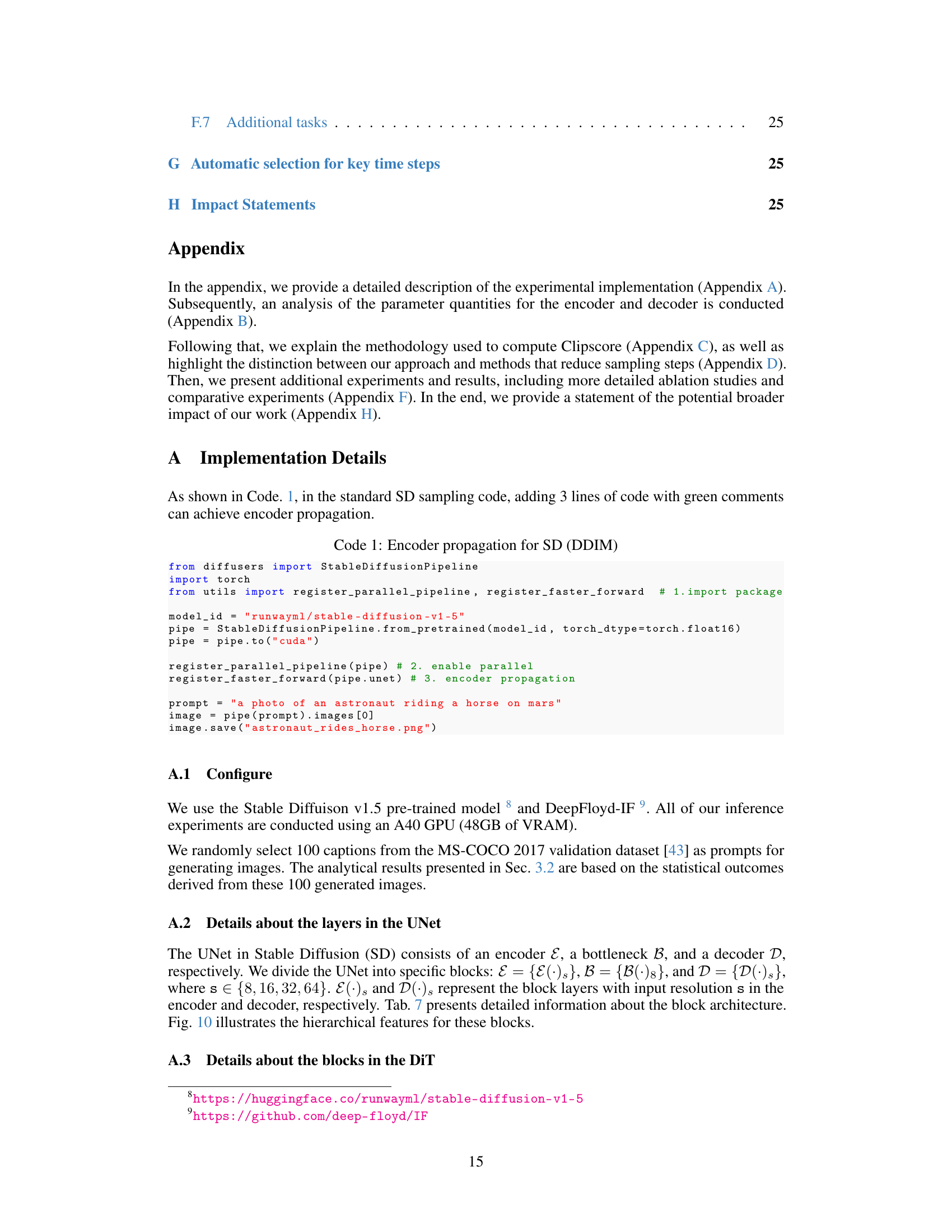

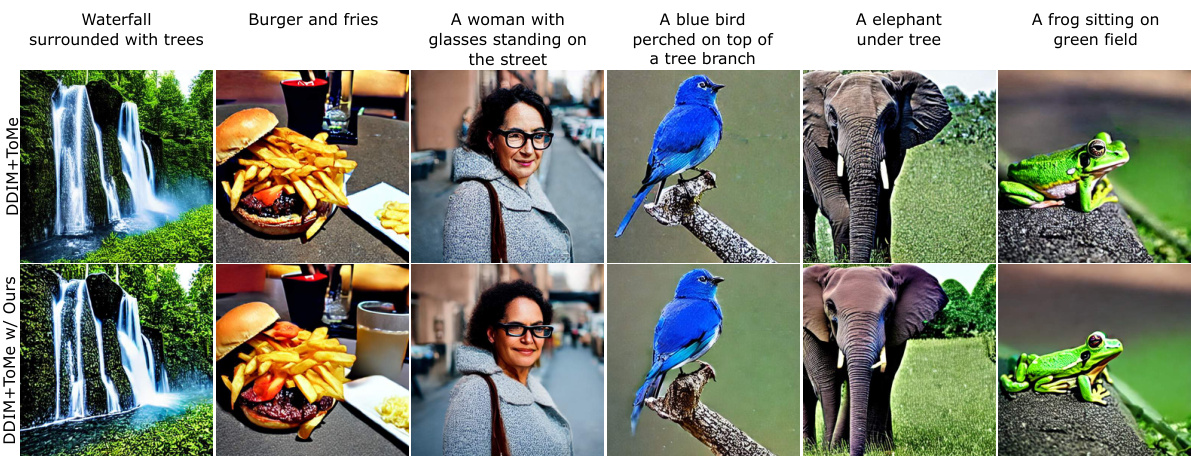

🔼 This figure illustrates different sampling strategies in Stable Diffusion. (a) shows standard sampling, (b) the UNet architecture, (c) encoder propagation (reusing encoder features from previous steps), (d) decoder-only propagation (which fails to generate complete images), and (e) non-uniform encoder propagation (parallel processing for efficiency).

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) Standard SD sampling. (b) UNet architecture. (c) Encoder propagation. We omit the encoder at certain adjacent time-steps and reuse in parallel the encoder features in the previous time-steps for the decoder. Applying encoder propagation for uniform strategy every two iterations. Note, at time-step t-1, predicting noise does not require Zt-1 (i.e., Eq. 1: 2t-2 = 1/√at-1 (1 - at-1/at-2)zt-1 + √at-1 ε(zt-1,t-1,c)). (d) Decoder propagation. The generated images often fail to cover some specific objects in the text prompt. For example, given one prompt case 'A man with a beard wearing glasses and a beanie', this method fails to generate the glasses subject. See Appendix F for quantitative evaluation. (e) Applying encoder propagation for non-uniform strategy. By benefiting from our propagation scheme, we are able to perform the decoder in parallel at certain adjacent time-steps.

🔼 This figure shows the improvement in image generation speed achieved by the proposed method on various image generation tasks. The table compares the original inference time of different diffusion models (Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, Custom Diffusion, VideoFusion, DiT, ControlNet) with their inference time after applying the proposed method. The percentage reduction in inference time is also indicated. The figure highlights the method’s effectiveness across a variety of tasks and its significant speed improvement.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure showcases the speed improvements achieved by the proposed method across various image generation tasks. It displays a table comparing the time taken for image generation using different diffusion models (Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, Custom Diffusion, VideoFusion, DiT, ControlNet) both with and without the proposed method. The significant reduction in generation time demonstrates the effectiveness of the approach in accelerating the inference process of diffusion models.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of image generation times for various diffusion models, both with and without the proposed Faster Diffusion method. It demonstrates significant speed improvements across different tasks such as Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, and custom diffusion models, as well as applications like VideoFusion and ControlNet. The speedup percentages are also indicated for each model.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows the results of image generation using different encoder propagation strategies. The uniform strategies (I, II, and III) produce images with varying degrees of smoothness and detail loss. The non-uniform strategy (I, II, III, and IV (Ours)) shows an improved result compared to the uniform strategies, with the best result being from strategy IV (Ours).

read the caption

Figure 9: Generating image with uniform and non-uniform encoder propagation. The result of uniform strategy II yields smooth and loses textual compared with SD. Both uniform strategy III and non-uniform strategy I, II and III generate images with unnatural saturation levels.

🔼 This figure analyzes the UNet architecture used in diffusion models. It shows that the encoder features change minimally across adjacent time steps, while decoder features show substantial variation. This observation supports the paper’s method of omitting encoder computations at certain steps and reusing previous encoder features.

read the caption

Figure 3: Analyzing the UNet in Diffusion Model. (a) Feature evolving across adjacent time-steps is measured by MSE. (b) We extract the hierarchical features output of different layers of the UNet at each time-step, average them along the channel dimension to obtain two-dimensional hierarchical features, and then calculate their Frobenius norm. (c) The hierarchical features of the UNet encoder show a lower standard deviation, while those of the decoder exhibit a higher standard deviation.

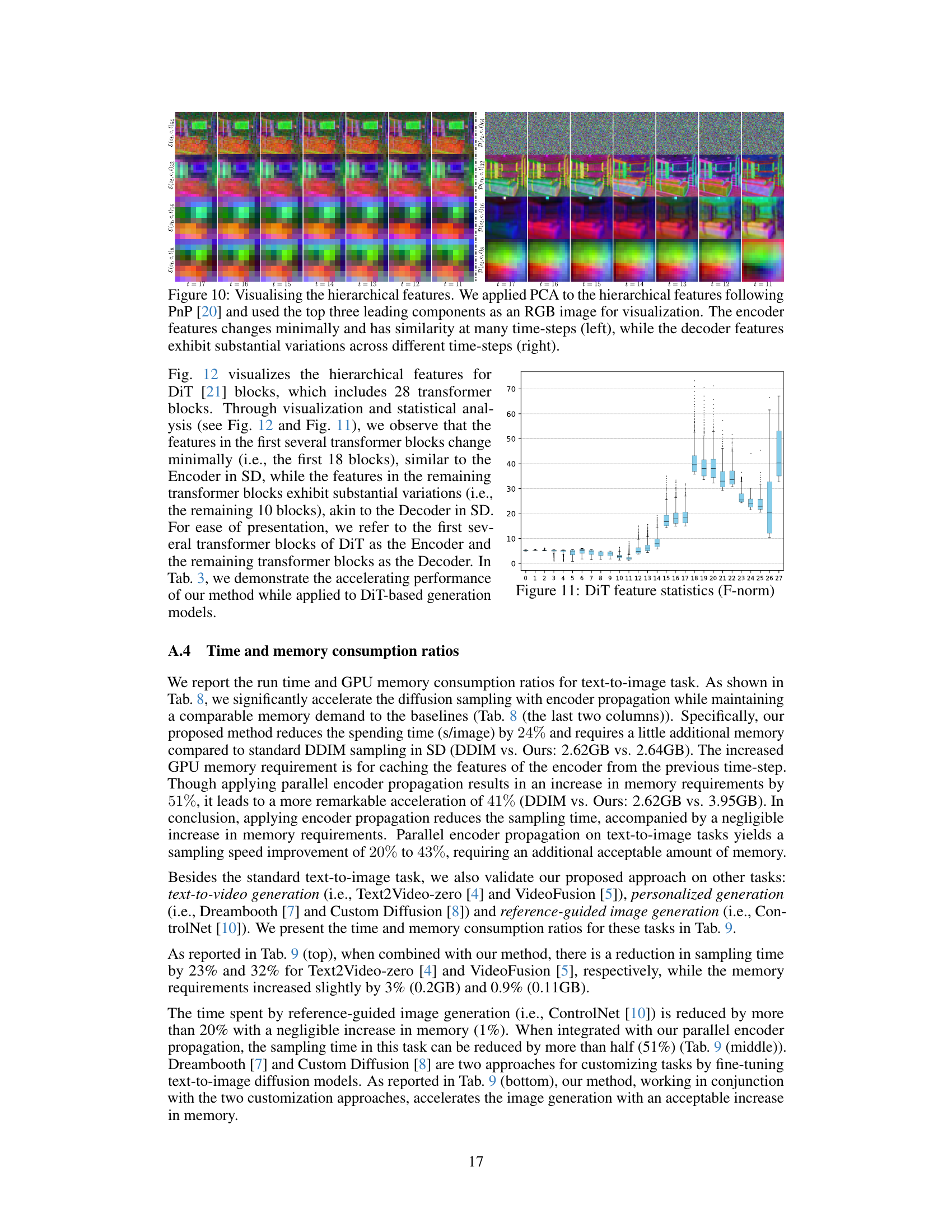

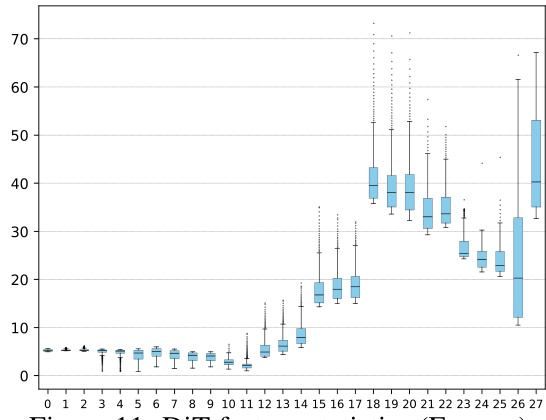

🔼 The figure visualizes the Frobenius norm (F-norm) of hierarchical features in the Diffusion Transformer (DiT) model across different time steps. It shows that the encoder features change minimally, whereas the decoder features exhibit substantial variations across different time steps. This observation supports the paper’s claim that encoder features can be reused across multiple time steps to accelerate inference.

read the caption

Figure 11: DiT feature statistics (F-norm)

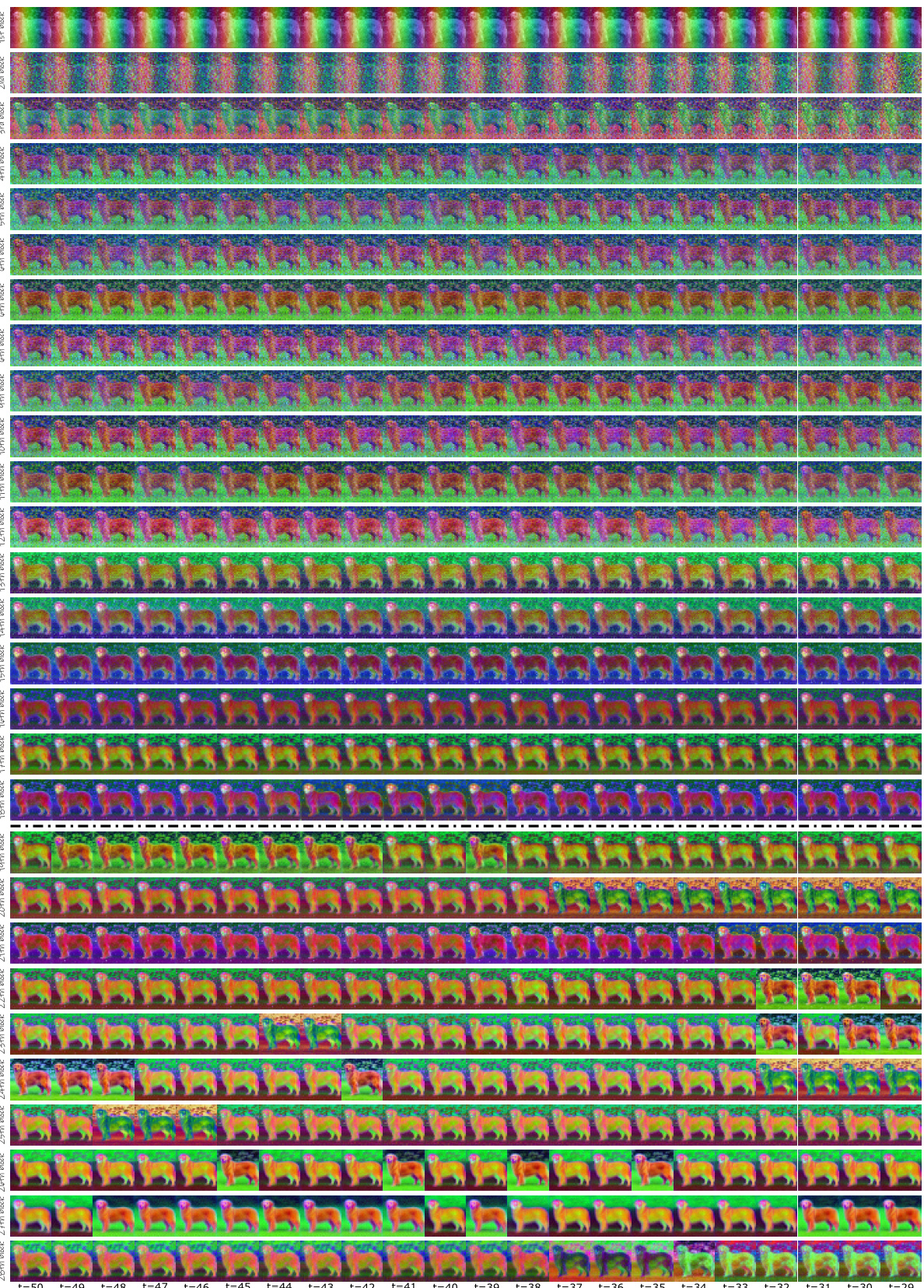

🔼 This figure shows the generated images at different time steps during the diffusion process. It visually demonstrates how the image gradually becomes clearer and more refined as the number of steps increases, highlighting the iterative nature of diffusion models. The figure likely accompanies results showing that the proposed method effectively preserves image quality even when reducing sampling steps, illustrating the method’s ability to maintain high-fidelity image generation.

read the caption

Figure 7: Generated images at different time-steps.

🔼 This figure showcases the speed improvements achieved by the proposed method across various image generation tasks. It presents a comparison of the time taken for image generation (in seconds per image) between the original diffusion models (e.g., Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DDPM) and the same models enhanced with the proposed Faster Diffusion technique. The results demonstrate significant speed improvements (e.g., 41% for Stable Diffusion, 24% for DeepFloyd-IF) across different methods and tasks, highlighting the effectiveness of Faster Diffusion in accelerating image generation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the proposed Faster Diffusion method to various image generation tasks, including Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, and a custom diffusion model. It demonstrates the significant speed improvements achieved by the method. For each task, the figure presents the original inference time and the inference time after applying the proposed method. The percentage reduction in inference time is also displayed. The tasks cover a range of complexity and model architectures, showing the broad applicability of Faster Diffusion.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of image generation speeds for various diffusion models, both with and without the proposed method. The models tested include Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, and a custom diffusion model. For each model, the image generation time is shown in seconds per image. The improvement achieved by applying the proposed method (indicated by ‘w/ Ours’) is also shown as a percentage reduction. The results demonstrate significant speed improvements across a variety of tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure illustrates different sampling strategies in diffusion models. (a) shows standard sampling, (b) shows UNet architecture, (c) shows encoder propagation where encoder computations are omitted at certain steps and reused from previous steps, (d) shows decoder propagation where decoder is computed independently, and (e) shows a non-uniform encoder propagation strategy.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) Standard SD sampling. (b) UNet architecture. (c) Encoder propagation. We omit the encoder at certain adjacent time-steps and reuse in parallel the encoder features in the previous time-steps for the decoder. Applying encoder propagation for uniform strategy every two iterations. Note, at time-step t-1, predicting noise does not require Zt-1 (i.e., Eq. 1: \(\frac{\sqrt{a_{t-2}}}{\sqrt{a_{t-1}}} = \frac{\sqrt{a_{t-2}}}{\sqrt{a_{t-1}}} z_{t-1} + \sqrt{a_{t-1} - a_{t-2}} \epsilon_{t-1} \)). (d) Decoder propagation. The generated images often fail to cover some specific objects in the text prompt. For example, given one prompt case \'A man with a beard wearing glasses and a beanie\'. this method fails to generate the glasses subject. See Appendix F for quantitative evaluation. (e) Applying encoder propagation for non-uniform strategy.

🔼 This figure showcases the speed improvements achieved by the proposed method across various image generation tasks. It presents a comparison of inference times (in seconds per image) for several different diffusion models (Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, a custom diffusion model, and VideoFusion) both before and after applying the proposed acceleration technique. The percentage reduction in inference time is also shown for each model. The tasks include text-to-image, text-to-video, and reference-guided generation, demonstrating the method’s versatility and effectiveness across different applications.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of image generation times for various diffusion models, both with and without the proposed Faster Diffusion method. The models tested include Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, and a custom diffusion model. For each model, the image generation time in seconds per image is shown, along with the percentage reduction achieved by Faster Diffusion. The results demonstrate substantial speed improvements across various generation tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the proposed faster diffusion method to various image generation tasks. It demonstrates significant speed improvements across different diffusion models and generation types (Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DiT, VideoFusion, ControlNet) compared to their standard implementations. The speedup is expressed as a percentage reduction in seconds per image.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure displays the results of applying the Faster Diffusion method to various image generation tasks, showcasing significant speed improvements across different models and tasks. The speed improvements are quantified in seconds per image, highlighting the method’s effectiveness in accelerating image generation. The tasks shown include Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, and custom diffusion, demonstrating the broad applicability of Faster Diffusion.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows the speed improvement achieved by the proposed method across various image generation tasks. The results are presented as a table comparing the original inference time (in seconds per image) with the inference time after applying the proposed method. Significant speed improvements (in percentages) are shown for several popular diffusion models like Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, and DiT, as well as for tasks such as text-to-video generation using VideoFusion, and reference-guided image generation with ControlNet. The diverse range of models and tasks highlights the broad applicability of the proposed acceleration technique.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows the speedup achieved by the proposed method on various image generation tasks compared to existing methods. It demonstrates the significant improvement in inference time across diverse models and applications, including Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, Custom Diffusion, and VideoFusion. The percentage improvements are also indicated.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of the image generation speed achieved by various diffusion models (Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, Custom Diffusion, VideoFusion, DiT, ControlNet) with and without the proposed Faster Diffusion method. For each model, the inference time in seconds per image is displayed, along with the percentage decrease in time achieved using Faster Diffusion. The results demonstrate that the method significantly speeds up the image generation process across a variety of generation tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the proposed Faster Diffusion method to several different image generation tasks. The left side shows various baselines (e.g., Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, etc.) and their inference times. The right side displays the inference time after applying the Faster Diffusion technique to these same models, with a percentage reduction in inference time. The tasks used in the experiments are diverse and include text-to-image, video generation, and others. The results demonstrate the significant speedup achieved by the Faster Diffusion method across a wide range of diffusion models and generation tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of image generation speed using various diffusion models, both with and without the proposed Faster Diffusion method. The models include Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd-IF, DDIM, DPM-Solver++, and a custom diffusion model, showcasing the significant speed improvements achieved by Faster Diffusion across different generation tasks, from simple image generation to more complex tasks like VideoFusion and ControlNet. Each model’s speed is measured in seconds per image, and percentage improvements over the original models are indicated.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of our method for a diverse set of generation tasks. We significantly increase the image generation speed (second/image).

More on tables

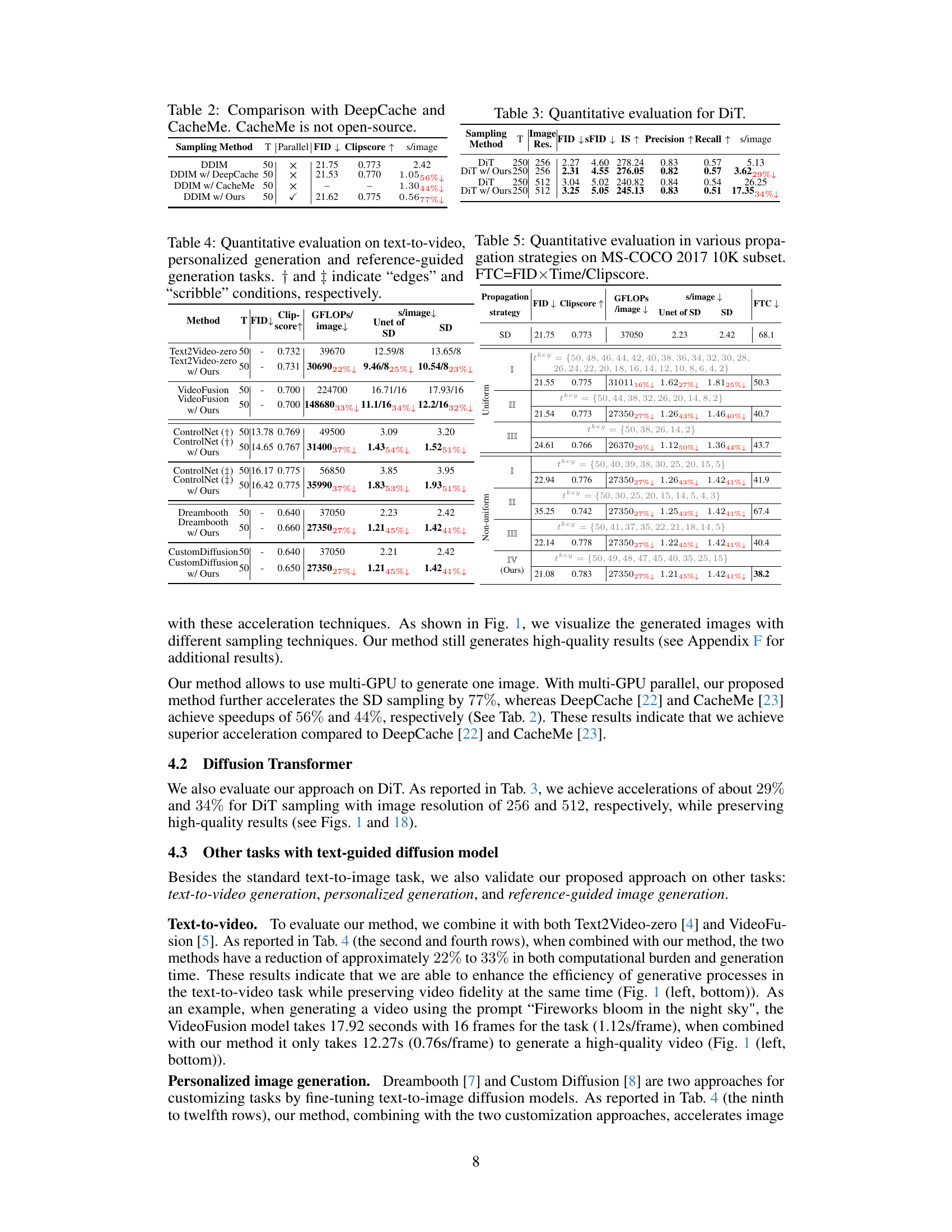

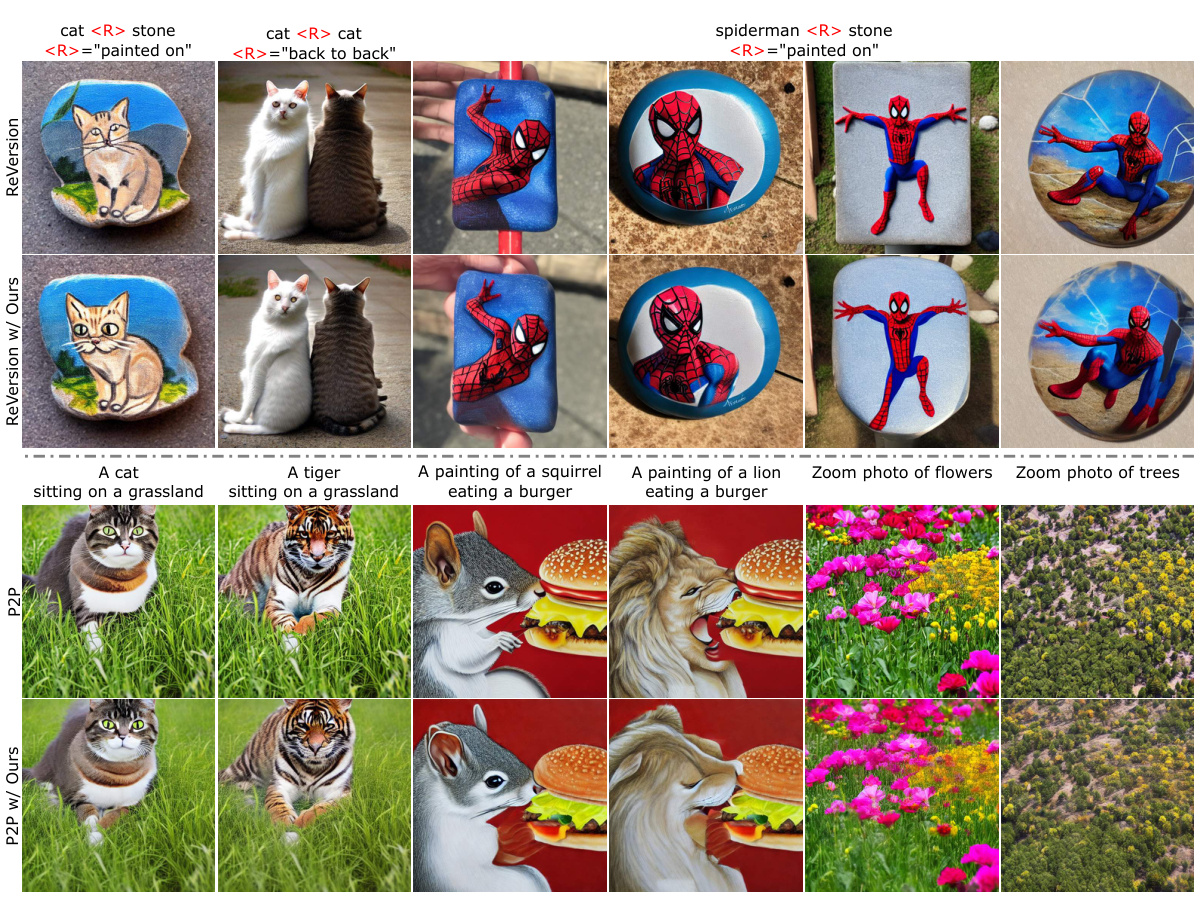

🔼 This table compares the performance of DDIM sampling with three different acceleration methods: DeepCache, CacheMe, and the proposed method. The metrics used for comparison are FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), Clipscore, and sampling time (s/image). The table shows that the proposed method achieves the best FID and Clipscore scores, with a significant reduction in sampling time compared to both DeepCache and CacheMe. Note that CacheMe’s results are not included as it’s not open-source.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison with DeepCache and CacheMe. CacheMe is not open-source.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative evaluation of the DiT model (Diffusion Transformer) with and without the proposed encoder propagation method. The results are compared across different image resolutions (256x256 and 512x512 pixels) and various metrics such as FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), IS (Inception Score), Precision, Recall, and inference time (s/image). Lower FID scores indicate better image quality, while higher IS, Precision, and Recall values signify improved image generation performance. The percentage change in inference time is also shown, highlighting the speed improvements achieved using the proposed method.

read the caption

Table 3: Quantitative evaluation for DiT.

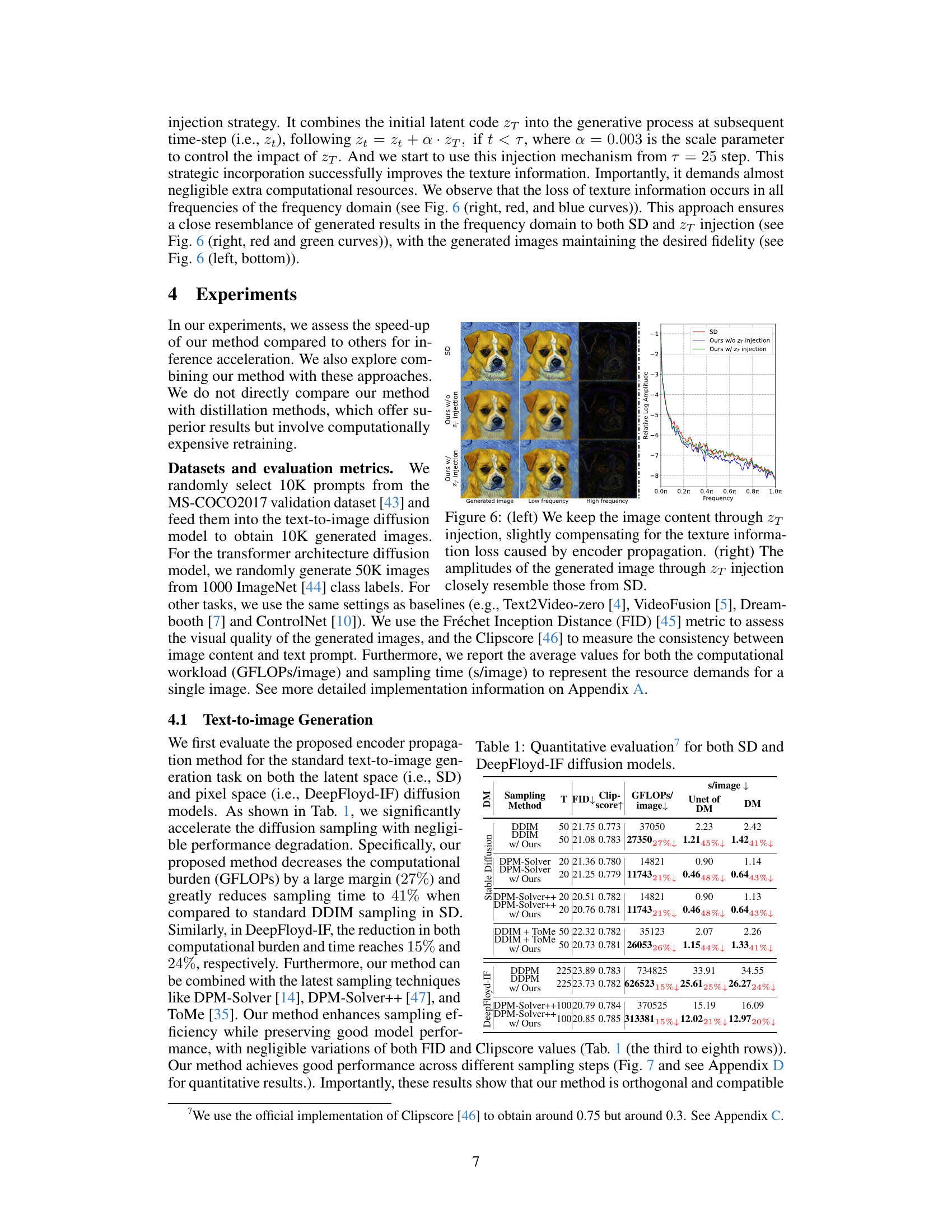

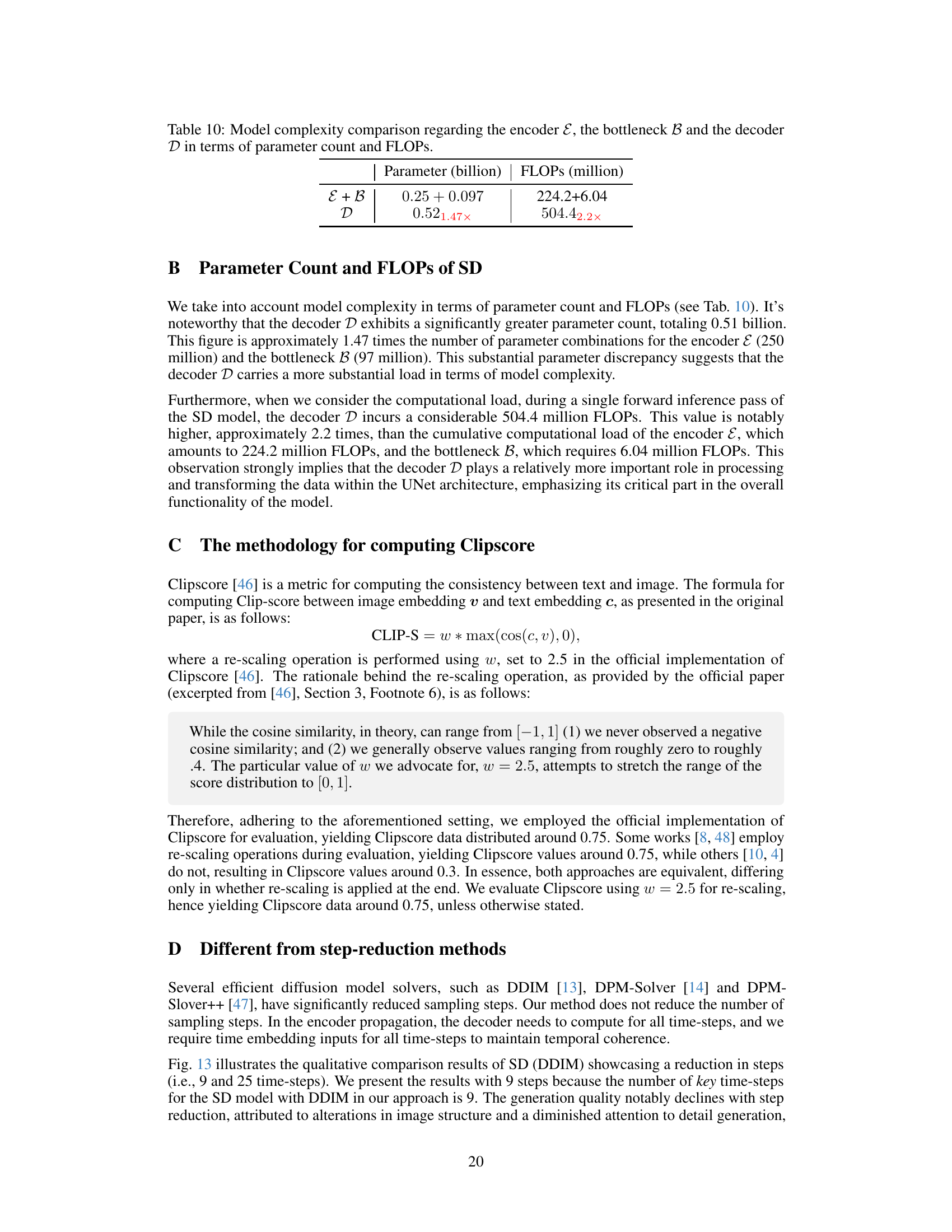

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different diffusion models (Stable Diffusion and DeepFloyd-IF) using various sampling methods, including the proposed FasterDiffusion method. For each model and method, the table shows the number of sampling steps (T), Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) score (a lower score indicates better image quality), CLIP score (a higher score indicates better alignment between image and text prompt), computational workload (GFLOPS/image), and sampling time (s/image). The percentage decrease in GFLOPs and sampling time relative to the baseline DDIM method are also provided, demonstrating the efficiency gains achieved by FasterDiffusion. The table also shows that the proposed method maintains good performance even when used with other sampling optimization techniques (DPM-Solver, DPM-Solver++, and ToMe).

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation for both SD and DeepFloyd-IF diffusion models.

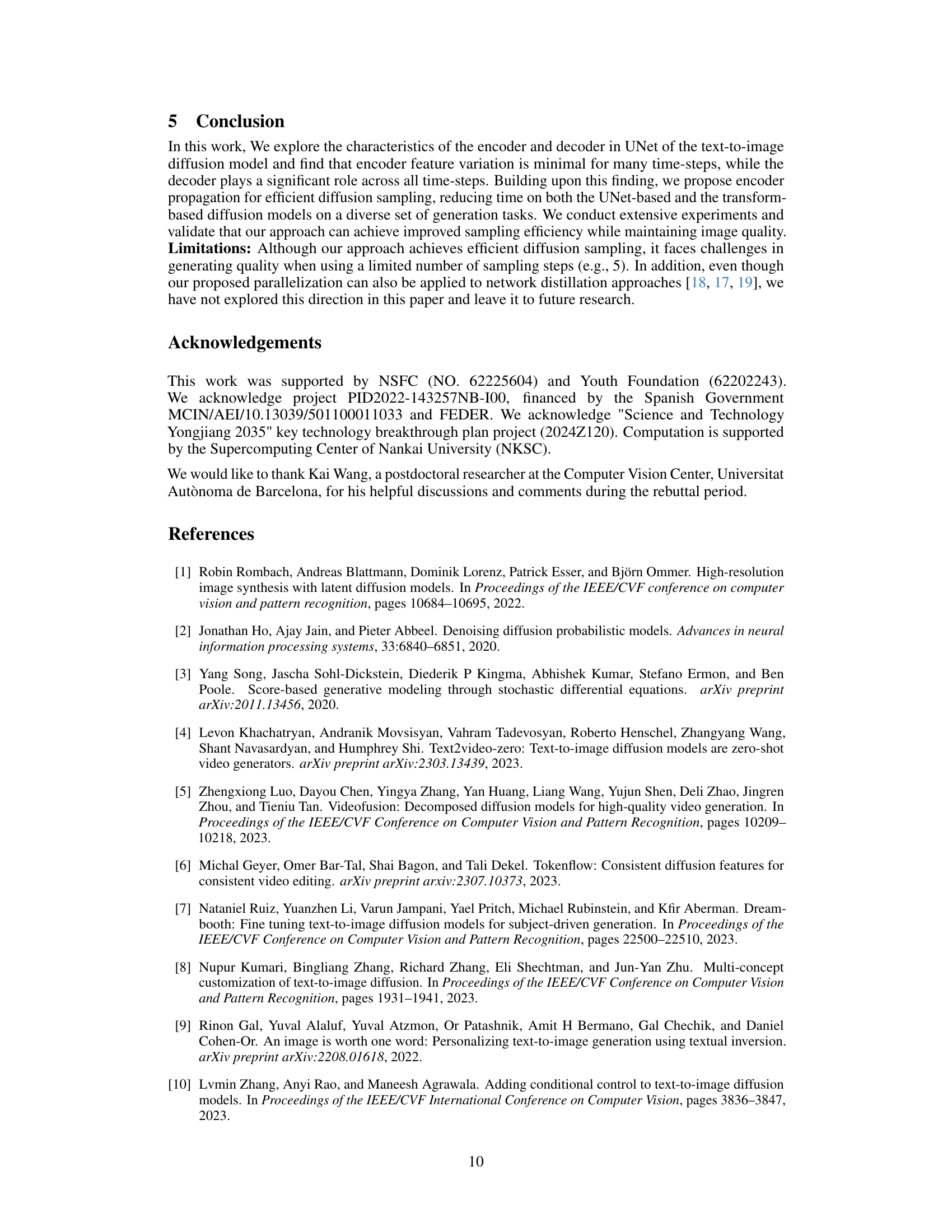

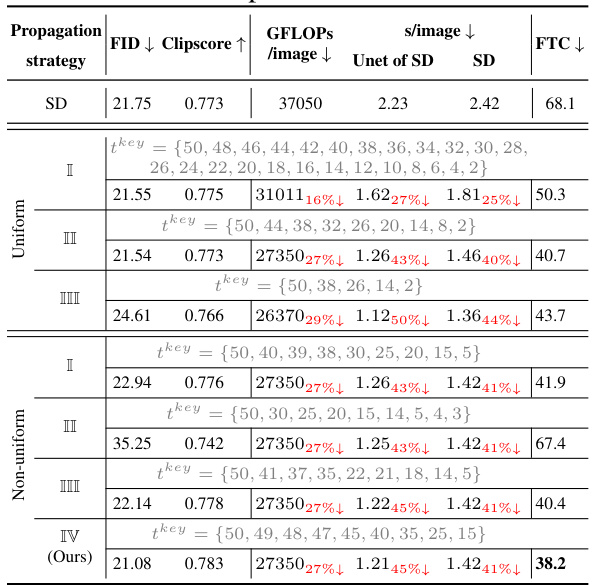

🔼 This table presents the quantitative evaluation results for different propagation strategies on the MS-COCO 2017 10K subset. It compares the FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), Clipscore, GFLOPS/image (giga floating-point operations per image), seconds/image, and FTC (a combined metric of FID, time, and Clipscore) for various propagation strategies, including uniform and non-uniform approaches with different sets of key time steps. The results show the impact of different key time step selections on the overall performance, providing insights into the effectiveness of the proposed non-uniform encoder propagation strategy.

read the caption

Table 5: Quantitative evaluation in various propagation strategies on MS-COCO 2017 10K subset. FTC=FID×Time/Clipscore.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different sampling methods for Stable Diffusion (SD) and DeepFloyd-IF models. Metrics include FID (Fréchet Inception Distance) for image quality, Clipscore for text-image consistency, GFLOPs/image (giga floating point operations per image) for computational cost, and s/image (seconds per image) for inference time. Different sampling methods like DDIM, DPM-Solver, DPM-Solver++, and DDPM are compared with and without the proposed encoder propagation method. The table helps to illustrate the efficiency gains from the proposed method while maintaining comparable image quality.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation for both SD and DeepFloyd-IF diffusion models.

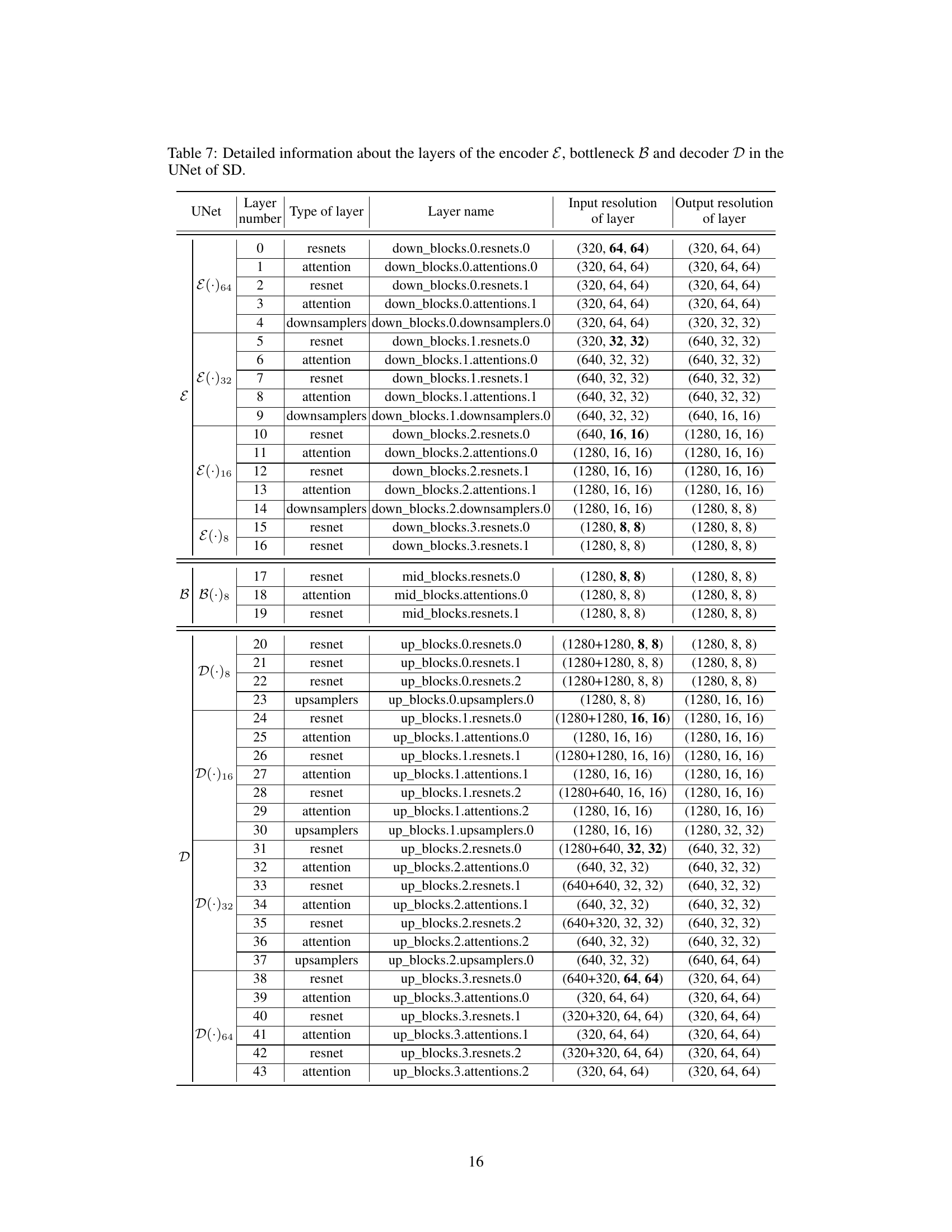

🔼 This table provides a detailed breakdown of the architecture of the UNet in the Stable Diffusion model. It lists each layer, its type (resnet, attention, downsampler, upsampler), name, input resolution, and output resolution. This information is crucial for understanding the flow of information and processing within the UNet during image generation.

read the caption

Table 7: Detailed information about the layers of the encoder E, bottleneck B and decoder D in the UNet of SD.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different sampling methods (DDIM, DPM-Solver, DPM-Solver++, DDIM+ToMe) applied to Stable Diffusion and DeepFloyd-IF models. It shows the sampling time (s/image), computational cost (GFLOPs/image), Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) score, and CLIP score for each method, both with and without the proposed encoder propagation technique. Lower FID and higher CLIP scores indicate better image quality. The percentage reduction in GFLOPs and time achieved by the proposed method is also shown.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation for both SD and DeepFloyd-IF diffusion models.

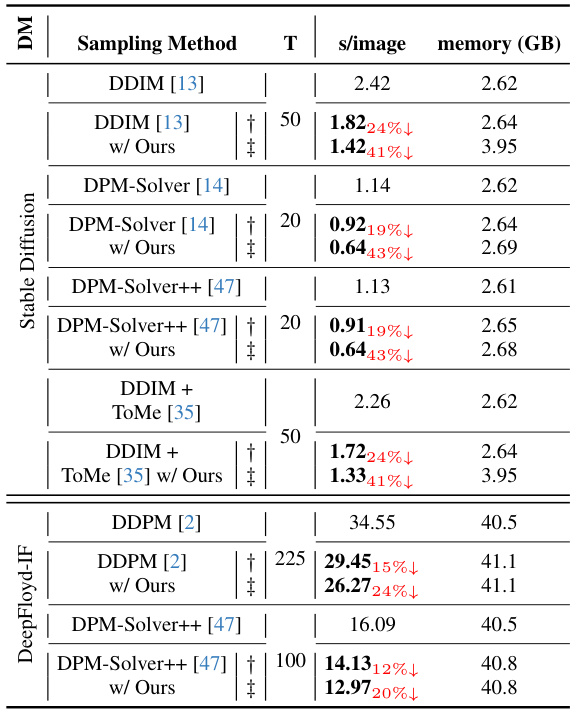

🔼 This table presents the inference time and GPU memory consumption for various tasks including text-to-video generation, personalized image generation, and reference-guided image generation. It compares the baseline methods against the proposed method with and without parallel encoder propagation. The results demonstrate significant speed improvements with minimal increase in memory usage for the proposed method.

read the caption

Table 9: Time and GPU memory consumption ratios in text-to-video, personalized generation and reference-guided generated tasks. †: Encoder propagation, ‡: Parallel encoder propagation.

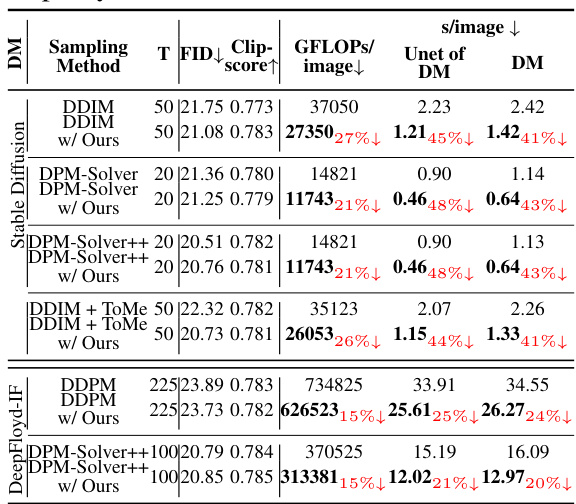

🔼 This table shows the parameter count and FLOPs for the encoder, bottleneck, and decoder components of the UNet architecture in the Stable Diffusion model. The decoder has significantly more parameters (0.52 billion) and FLOPs (504.4 million) compared to the encoder and bottleneck combined (0.347 billion parameters and 230.24 million FLOPs). This highlights the computational cost associated with the decoder, which suggests a larger role in processing and transforming data during diffusion sampling.

read the caption

Table 10: Model complexity comparison regarding the encoder \(\mathcal{E}\), the bottleneck \(\mathcal{B}\) and the decoder \(\mathcal{D}\) in terms of parameter count and FLOPs.

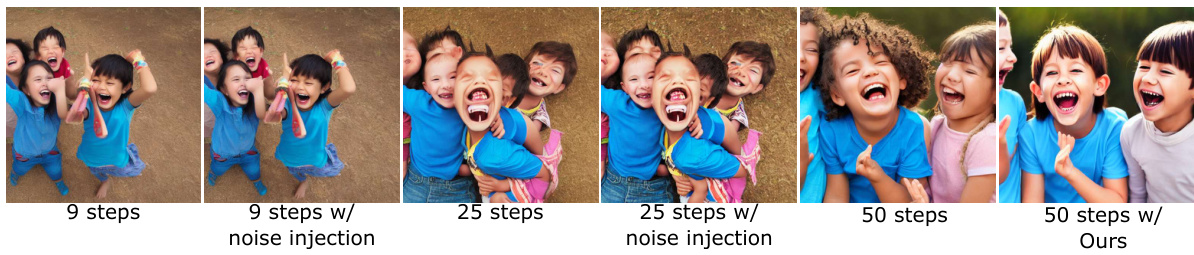

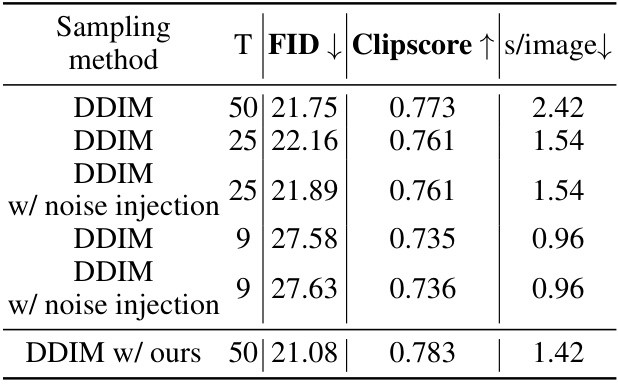

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the DDIM sampling method with varying numbers of sampling steps. It shows the FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), Clipscore, and sampling time (s/image) for different scenarios: DDIM with 50, 25, and 9 steps; DDIM with noise injection at 25 and 9 steps; and DDIM with the authors’ proposed method at 50 steps. The results illustrate the impact of reducing the number of steps on the image quality and generation time.

read the caption

Table 11: Quantitative comparison for DDIM with fewer steps.

🔼 This table compares the performance of DPM-Solver and DPM-Solver++ with different numbers of sampling steps (T). The metrics used for comparison are FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), Clipscore, and the sampling time (s/image). Rows show results for the baselines and the same methods combined with the proposed ’encoder propagation’ approach. The table demonstrates the impact of reduced sampling steps on image quality and generation time, and the effectiveness of the proposed method in mitigating performance degradation.

read the caption

Table 12: Quantitative comparison for DPM-Solver/DPM-solver++ with fewer steps.

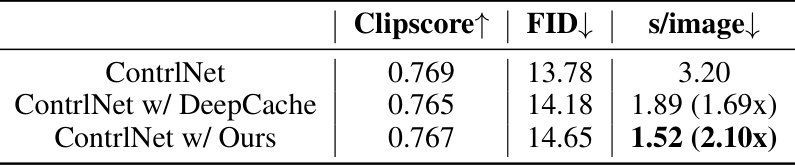

🔼 This table compares the inference time of ControlNet with different acceleration methods: without any acceleration, with DeepCache, and with the proposed method. It shows that the proposed method significantly reduces the inference time compared to both the baseline and DeepCache.

read the caption

Table 13: When combined with ControlNet (Edge) 50-step DDIM, our inference time shows a significant advantage compared to DeepCache.

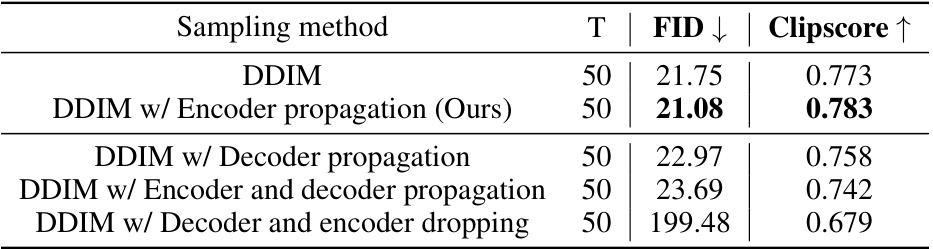

🔼 This table presents a quantitative evaluation of different propagation strategies on the MS-COCO 2017 dataset. It compares the standard DDIM sampling method with variations including only encoder propagation, only decoder propagation, both encoder and decoder propagation, and decoder and encoder dropping. The FID and Clipscore metrics are used to evaluate the image quality and text-image consistency respectively. The results show that while encoder propagation improves both metrics, other strategies lead to a significant decline in performance, highlighting the importance of the proposed method’s selective encoder usage.

read the caption

Table 14: Quantitative evaluation for additional strategy on MS-COCO 2017 10K subset. Other propagation strategies can lead to the loss of some semantics under prompts and degradation of image quality (the third to fifth rows).

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different diffusion models (Stable Diffusion and DeepFloyd-IF) using various sampling methods, including DDIM, DPM-Solver, DPM-Solver++, and DDPM. It shows the sampling time (s/image), the computational workload (GFLOPs/image), FID (Fréchet Inception Distance) scores, and ClipScore values for each model and sampling method. The table also compares the performance of these models when using the proposed method (encoder propagation). Lower sampling time and GFLOPS, along with similar or better FID and ClipScore, indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation7 for both SD and DeepFloyd-IF diffusion models.

Full paper#